The Wheel of Work and the Sustainable Livelihoods Index (SL-I)

Abstract

1. Background: A Great Disruption

Ambition and Objective of the Current Paper

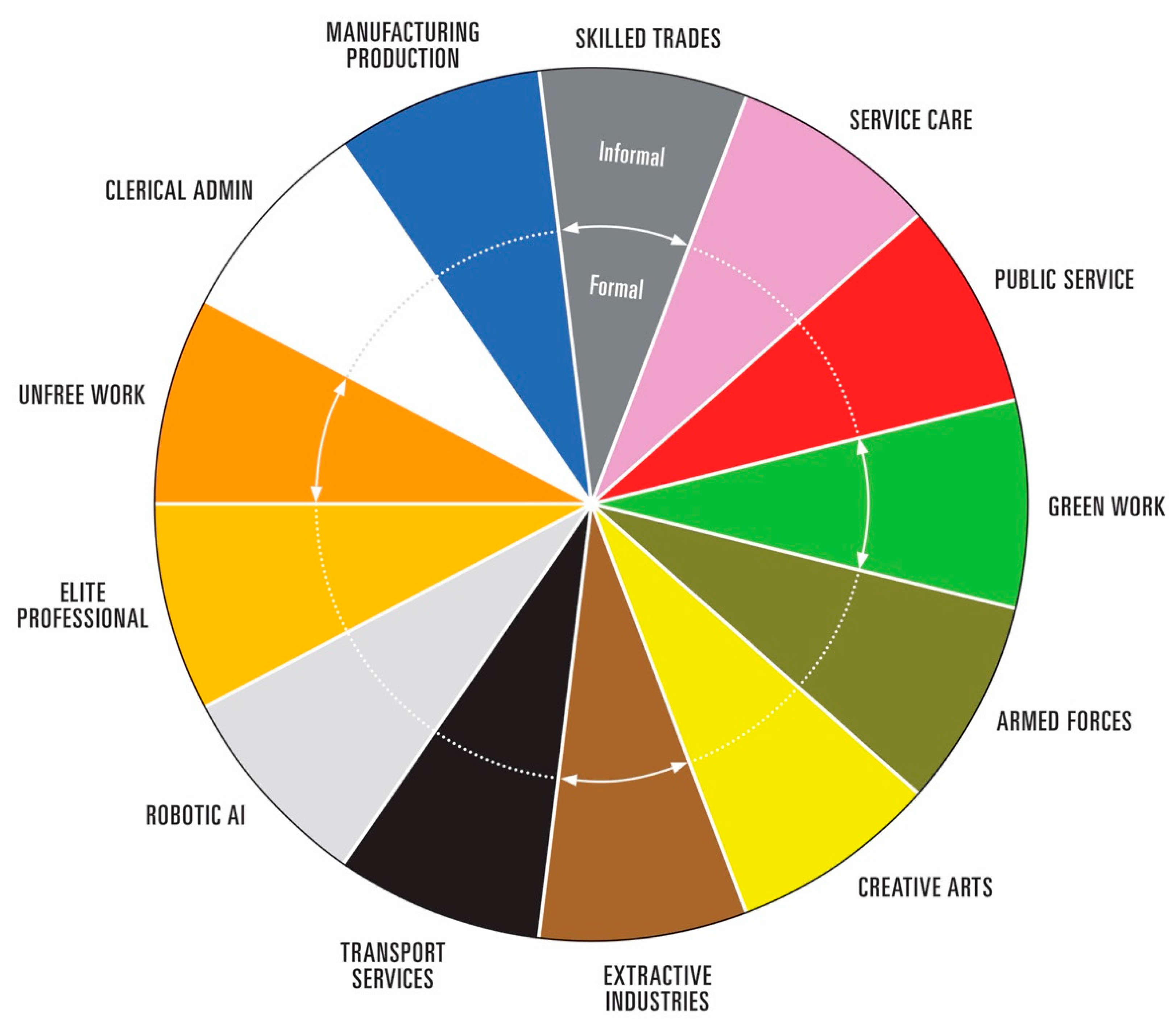

2. A Functional Classification

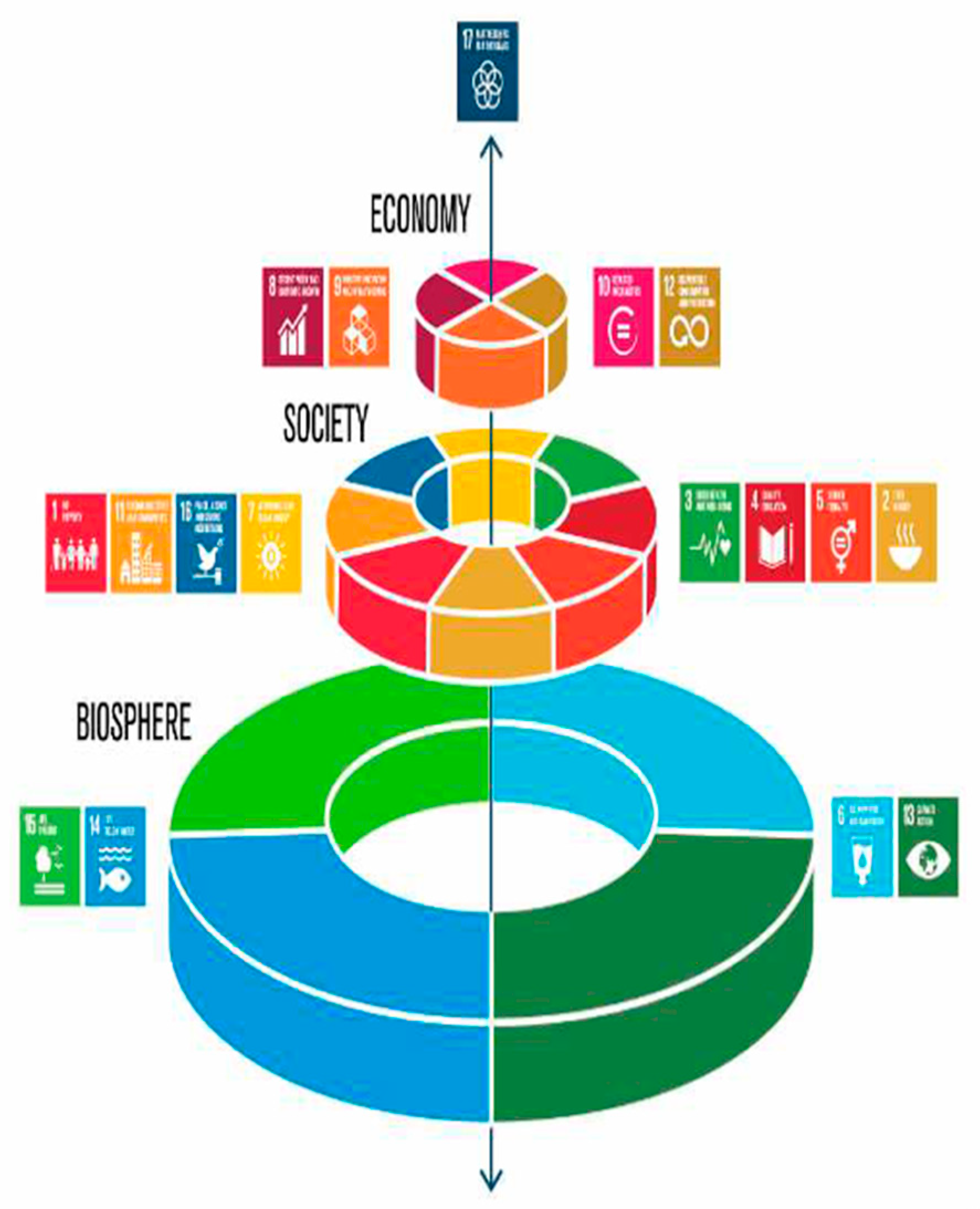

3. Sustainable Livelihoods

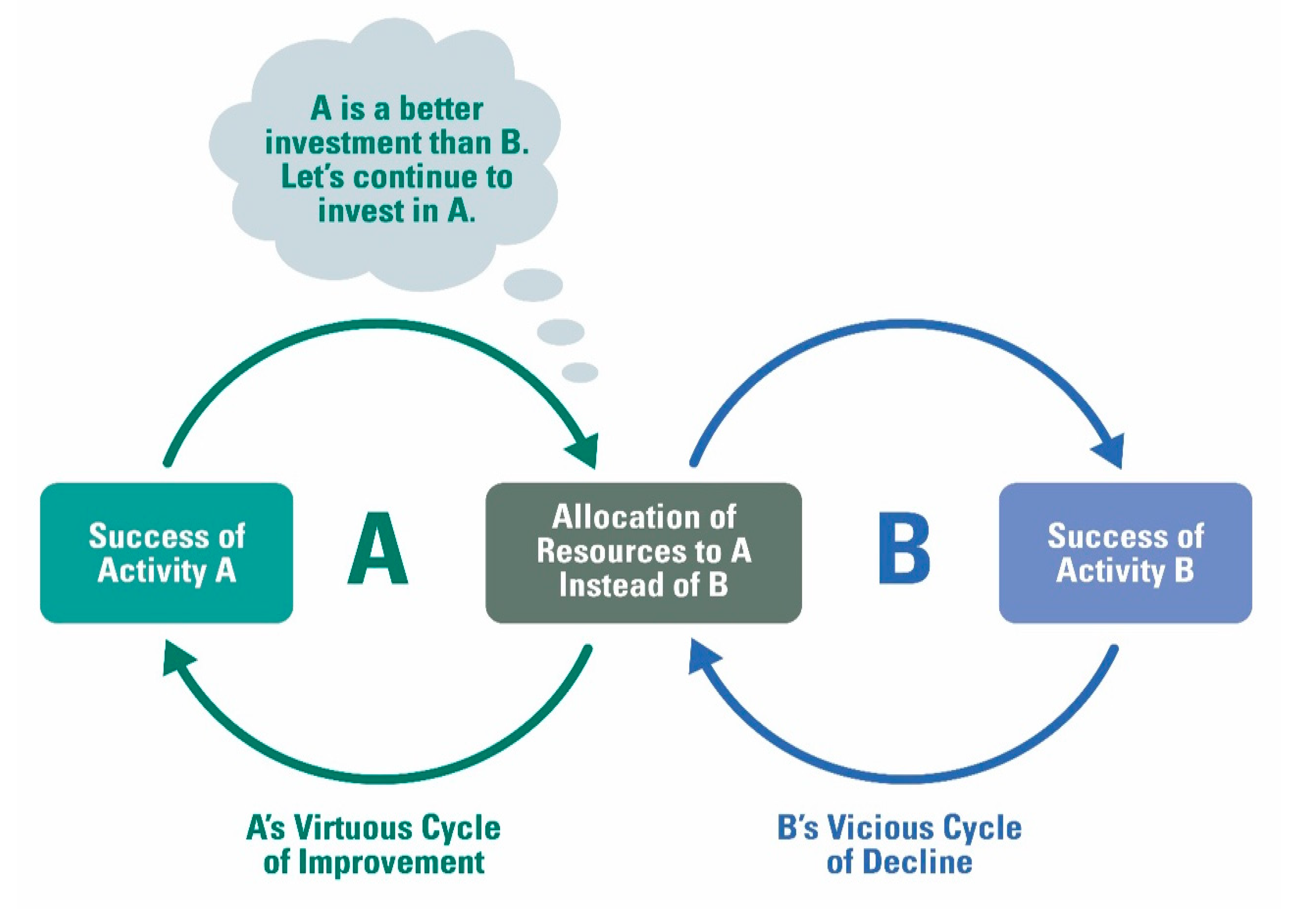

What Will Be Done: Methods

4. Performance Criteria

5. What Will Be Tested: Pilot

6. What May Be Developed: New Theory

7. Levels

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Méda, D. What Does Sustainable Work Really Mean? New Perspectives from the International Labour Review; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/what-does-sustainable-work-really-mean-new-perspectives-international (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- ILO (International Labour Organization). The Decent Work Agenda; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999–2024. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, S.C. Wage and Wellbeing: Toward Sustainable Livelihoods; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hopner, V. From indecent work to sustainable livelihoods in the age of the Anthropocene. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2023, 32, 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, S.C.; Hopner, V.; Hodgetts, D.J.; Young, M. (Eds.) Tackling Precarious Work: Toward Sustainable Livelihoods; Routledge/SIOP New Frontiers: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup. State of the Global Workplace: The Voice of the World’s Employees; Gallup Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup. State of the Global Workplace: Understanding Employees, Informing Leaders; Gallup Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- ILO (International Labour Organization). World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2024; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. State of Social Protection Report 2025: The 2-Billion-Person Challenge; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/42842 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- ILO (International Labour Organization). Global Call to Action for a Human-Centered Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis That Is Inclusive, Sustainable and Resilient; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ILO (International Labour Organization). World Employment and Social Outlook: The Value of Essential Work; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, L.; Zimmerman, B. Sustainable Work: A Conceptual Map for a Social-Ecological Approach. Int. Labour Rev. 2025, 164, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). OECD Employment at Record High While the Climate Transition Expected to Lead to Significant Shifts in Labor Markets; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Beier, M.E.; Saxena, M.; Kraiger, K.; Costanza, D.P.; Rudolph, C.W.; Cadiz, D.M.; Petery, G.A.; Fisher, G.G. Workplace learning and the future of work. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2025, 18, 84–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO (International Labour Organization). The Role of Digital Labour Platforms in Transforming the World of Work; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, K.M. Making a go of it in the Gig Economy: Understanding risk in platform-based work. In Tackling Precarious Work: Toward Sustainable Livelihoods; Carr, S.C., Hopner, V., Hodgetts, D.J., Young, M., Eds.; Routledge/SIOP New Frontiers: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 20–301. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Moving Beyond GDP at HLPF (High Level Political Forum) 2024; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Saner, R.; Yiu, L. The new diplomacies and humanitarian work psychology. In Humanitarian Work Psychology; Carr, S.C., MacLachlan, M., Furnham, A., Eds.; Palgrave-Macmillan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 129–165. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. Practising what we preach? The failure to apply sustainable livelihoods thinking where it is most needed—In the North. Sustain. Livelihoods Viewp. 2009, 2, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lo, K. Just Transition: A conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102291. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, A.; Gale, F.; Murphy-Gregory, H. Just Transitions’ Meanings: A systematic review. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2023, 36, 1277–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A.; Rosen, M.A. An exploratory study of a new psychological instrument for evaluating sustainability: The Sustainable Development Goals Psychological Inventory. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazer, S.; Robie, C.; Kwantes, C.T.; Saxena, M.; Jain, S.; Munoz, G. An international perspective on changes in work due to COVID-19. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 59, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, M.; Tchagnéno, C. Informal work as sustainable work: Pathways to sustainable livelihoods. In SIOP Organizational Frontier Series Tackling Precarious Work Towards Sustainable Livelihoods; Carr, S.C., Hopner, V., Hodgetts, D., Young, M., Eds.; Routledge/SIOP New Frontiers Series: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO (International Labour Organization). International Standard Classification of Occupations—ISCO-08: Structure of the International Standard Classification of Occupation (ISCO-08); ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hopner, V.; Carr, S.C.; Matuschek, I. Green Collar work: Implications for Career Development. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2025, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J. Pride of Place: Science without taxonomy is blind. Sciences 1994, 34, 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rounds, J.; Tracey, T.J. Cross-cultural structural equivalence of RIASEC models and measures. J. Couns. Psychol. 1996, 43, 310–329. [Google Scholar]

- Tracey, T.J.G.; Rounds, J. The spherical representation of vocational interests. J. Vocat. Behav. 1996, 48, 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- ILO (International Labour Organization). Assessing the Current State of the Global Labour Market: Implications for Achieving the Global Goals. 2023. Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/blog/assessing-the-current-state-of-the-global-labour-market-implications-for-achieving-the-global-goals/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Hill, C.E.; Knox, S. Essentials of Consensual Qualitative Research; APA (American Psychological Association): Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.E.; Knox, S.; Thompson, B.J.; Williams, E.N.; Hess, S.A.; Ladany, N. Consensual Qualitative Research: An Update. College of Education Faculty Research and Publications. 2005. 18. Available online: https://epublications.marquette.edu/edu_fac/18 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Martin, L. The Origins of White Collar vs. Blue Collar. Re-Think Quarterly, 20 January 2023, p. 7. Available online: https://rethinkq.adp.com/history-white-collar-vs-blue-collar/#:~:text=Etymologist%20Barry%20Popik%20found%20that,1950%2C%20attributed%20to%20American%20origins (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Kelly, J. Gray-Collar Jobs Offer the Best of Both White and Blue-Collar Opportunities. Forbes, 1 February 2024. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2024/02/01/gray-collar-jobs-offer-the-best-of-both-white-and-blue-collar-opportunities/?sh=53efd011e4ab (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Lips-Wiersma, M.; Wright, S.; Dik, B. Meaningful work: Differences among blue-, pink-, and white-collar occupations. Career Dev. Int. 2016, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, N. Life Satisfaction among Green-Collar & Red-Collar Workers: A Comparative Study. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2013, 1, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- McClure, L.A.; LeBlanc, W.G.; Fernandez, C.A.; Fleming, L.E.; Lee, D.J.; Moore, K.J.; Caban-Martinez, A.J. Green Collar Workers: An Emerging Workforce in the Environmental Sector. J Occup Environ Med. 2017, 59, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bryant, C.D. Khaki-Collar Crime—Deviant Behaviour in the Military Context; US Department of Justice/National Criminal Justice Reference Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1979. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/khaki-collar-crime-deviant-behavior-military-context (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Saxena, M. Workers in poverty: An insight into informal workers around the world. Ind. Organ. Psychol. Perspect. Sci. Pract. 2017, 10, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, M.A. Cultivating the gold-collar worker. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2001, 79, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, M. Informal work. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACLU & GHRC. Captive Labor: Exploitation of Incarcerated Workers. 2022. Available online: https://www.aclu.org/news/human-rights/captive-labor-exploitation-of-incarcerated-workers (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- ILO (International Labour Organization). Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chipolina, S. $100mn in Crypto Payments Traced to Myanmar-Based ‘Scammers’. Financial Times, 25 February 2024, p. 11. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/fbe27292-4df9-4610-99e0-a93121e06dd3 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- McAlvay, A.C.; Paola, A.; D’Andrea, A.C.; Ruelle, M.L.; Mosulishvili, M.; Halstead, P.; Power, A.G. Cereal species mixtures: An ancient practice with potential for climate resilience. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 44, 1–17. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13593-022-00832-1 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Carr, S.C.; Meyer, I.; Saxena, M.; Seubert, C.; Hopfgartner, L.; Arora, B.; Jyoti, D.; Rugimbana, R.O.; Kempton, H. “Our fair-trade coffee tastes better.” It might but under what conditions? J. Consum. Aff. 2022, 2, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.C.; Conway, G.R. Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. In IDS (Institute of Development Studies), Discussion Paper 296; University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2022 Special Report on Human Security; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Amnesty International. Future of Humanity; Amnesty International: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Global Attitudes Survey; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, D.; Kahn, R.L. The Social Psychology of Organizations, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Moldan, B.; Janouskova, S.; Hak, T. How to understand and measure environmental sustainability: Indicators and Targets. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 17, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A.; Svicher, A. The challenge of eco-generativity. Embracing a positive mindset beyond eco-anxiety: A research agenda. Front. Psychol. 2021, 15, 1173303. [Google Scholar]

- Stockholm Resilience Centre. The SDGs Wedding Cake; Stockholm Resilience Centre: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024; Available online: https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-news/2016-06-14-the-sdgs-wedding-cake.html (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Senge, P. The Fifth Discipline; Random House: Sydney, Australia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss, J.L. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol. Bull. 1971, 76, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Final List of Proposed Sustainable Development Goal Indicators; UN Statistical Commission: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Govindan, K.; Shaw, M.; Majumdar, A. Social sustainability tensions in multi-tier supply chain: A systematic literature review towards conceptual framework development. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123075. [Google Scholar]

- Killpack, M. Five Environmental Metrics Worth Tracking. 2023. Available online: https://esg.conservice.com/five-environmental-sustainability-metrics-worth-tracking/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Charfeddine, L.; Umlai, M. ICT sector, digitalisation and environmental sustainability: A systematic review of the literature from 2000 to 2022. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 184, 113482. [Google Scholar]

- Dalkey, N. The Delphi Method: An Experimental Study of Group Opinions; The Rand Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, S.C. Social Psychology: Context, Communication, and Culture; Wiley: Sydney, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, J.; Moser, R. Biases in future-oriented Delphi studies: A cognitive perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 105, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, S.; Ishizaka, A.; Tasiou, M.; Torrisi, G. On the methodological framework of composite indices: A review of the issues of weighting, aggregation, and robustness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Conference Board. US Leading Indicators: The Leading Economic Index (LEI); Economy, Strategy, & Finance Center: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). Sustainable Livelihoods and Human Security. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Future Education, UN Trust for Human Security/World Academy of Arts & Sciences/Education for Human Security division of UNCTAD, Online, 7–8 March 2023; Spoken by UNCTAD Chief, Carpentier, C.L.. United Nations (UN): New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wilckens, M.R.; Wohrman, A.M.; Deller, J.; Wang, M. Organisational practices for the ageing workforce: Development and validation of the Later Life Workplace Index. Work Aging Retire. 2021, 7, 352–386. [Google Scholar]

- Hopner, V.; Carr, S.C. Identify, Index, Incentivise: Sustainable Livelihoods: A Clean Slate Decision? Massey University: Auckland, New Zealand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- MacLachlan, M.; Carr, S.C.; McAuliffe, E. The Aid Triangle: Recognising the Human Dynamics of Dominance, Justice and Identity; Zed Books: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Saner, R.; Yiu, L. NGO diplomacy to monitor and influence business and government to tackle work precariousness. In Tackling Precarious Work: Toward Sustainable Livelihoods; Carr, S.C., Hopner, V., Hodgetts, D.J., Young, M., Eds.; Routledge/SIOP New Frontiers: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 101–136. [Google Scholar]

- Saner, R.; Yiu, L. Business Diplomacy Competence: A Requirement for Implementing the OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Hague J. Dipl. 2014, 9, 311–333. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou, I. What the ESg Backlash Reveals—And What Comes Next. Forbes, 25 March 2025, pp. 1–6. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/lbsbusinessstrategyreview/2025/03/25/what-the-esg-backlash-reveals-and-what-comes-next/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Hopner, V.; Carr, S.C. Unfree work. In Proceedings of the Conference Proceedings: Society for Industrial and Organisational Psychology Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 17–20 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Amrutha, V.N.; Geetha, S.N. A systematic review on green human resource management: Implications for social sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Khazanchi, D.; Saxena, M. Navigating digital human rights in the age of AI: Challenges, theoretical perspectives, and research implications. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 2025, volume, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Collar Colour | Collar Name | Informal Example | Formal Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grey | SKILLED TRADES | Bitcoin Miner | Computer Programmer |

| Pink | SERVICE CARE | Migrant Maid | Retail Assistant |

| Red | PUBLIC SERVICE | Auxiliary aid worker | Firefighter |

| Green | GREEN WORK | Climate Activist | Sustainability Analyst |

| Khaki | ARMED FORCES | Paramilitaries | National Militaries |

| Yellow | CREATIVE ARTS | Social Influencer | Graphic Designer |

| Brown | EXTRACTIVE INDUSTRIES | Bush Fallower | Orchardist |

| Black | TRANSPORT SERVICES | Taxi Driver | Truck Driver |

| Silver | ROBOTIC AI | Bot | Robotic Engineer |

| Gold | ELITE PROFESSIONAL | Drug Cartel Boss | Professional athlete |

| Orange | UNFREE WORK | Child Miner | Prison Labour |

| White | CLERICAL ADMIN | Social Entrepreneur | Customer Service Representative |

| Blue | MANUFACTURING PRODUCTION | Labourer | Factory Hand |

| Environmental | Social | Economic |

|---|---|---|

| (D) Low Carbon footprint Greenhouse gas emissions in tons (S) Relevant global and/or context-specific measurement of low carbon emission (e.g., ISO Standard, https://www.iso.org/home.html, accessed on 1 May 2025 (I) A Livelihood estimate of carbon footprint—(e.g., the carbon footprint of diesel truck driving- The Carbon Footprint of Trucking (visualcapitalist.com) | (D) Tackles Poverty in Society Reduces material hardship and insecurity (S) Global benchmarks for reducing poverty and inequality (e.g., The World Development Indicators https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators, accessed on 1 May 2025 (I) Livelihoods that work to increase food security and access to healthcare, increase education, decent housing, energy access, promote greater employment prospects, strengthen communities, reduce crime, and other prosocial work-related activities to benefit others (see Prosocial Work Psychology (https://search.app/CfL39WHVdmgQ7GtY9, accessed on 1 May 2025) | (D) Delivers a Living wage (rate) Based on evidence and according to context (S) Project GLOW estimate, plus relevant national or regional living wage campaign figure (https://projectglow.net/; Living Wage Foundation Estimate livingwage.org.uk, accessed on 1 May 2025 (I) The median wage for the livelihood |

| (D) High Resource efficiency Sustainably uses both limited and non-renewable resources. (S) Levels of reducing, reusing, and recycling (ISO and other standards) (I) Livelihood estimate of efficiency (e.g., ORE ft in manufacturing (https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/IJPPM-11-2017-0282/full/html, accessed on 1 May 2025) | Promotes Equality and Equal Opportunity Access to opportunities and just rewards for all (S) Fosters social mobility (i.e., through pillars of health, education, technology, work, and institutions (Global Social Mobility Report 2020 https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-social-mobility-index-2020-why-economies-benefit-from-fixing-inequality/, accessed on 1 May 2025; see SDG 10 (empower and promote the social, economic, and political inclusion for all). (I) Livelihoods that enable social mobility and/ or fight for equality and equal opportunities, e.g., for livelihoods such as Teachers, Probation Officers, and Social Workers. | (D)Provides Living hours Based on evidence and according to the context, the evidence (S) Living Wage Foundation (https://search.app/5QDtQA2bS1wvnBuU6, accessed on 1 May 2025 (I) the median hours for the livelihood |

| (D) Regenerative/cyclical on waste Recycling and other circular practices (S) Livelihood sector’s ISO (e.g., ISO 5020 for fishing vessels) (I) Weight, volume, and type of waste for that livelihood’s work | (D) Enables civic contributions. Contributes to public good(s) (S) level of participation in community service, supporting healthy political systems, and solving societal issues. Civic Standards (https://search.app/CP8MfBQPczX3eB7t8, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) Livelihoods that are oriented around civil engagement, such as youth engagement, social entrepreneurship, and park managers (https://search.app/ZzCWZutr7mmDuZC47, accessed on 1 March 2025 | (D) Provides Work Safety According to the UN ILO Conventions (S) ILO Standards on Occupational Safety and Health (conventions and recommendations) (https://www.ilo.org/publications/ilo-guide-international-labour-standards-occupational-safety-and-health, accessed on 1 March 2025 (I) Livelihood ranking on Health and Safety measures specific to the region (e.g., https://search.app/5uvS6feLinR6VQht7, accessed on 1 March 2025 |

| (D) Is Energy efficient. Optimises energy consumption. (S) ISO 50001 (I) Energy produced/energy consumed ×100 (in tons) | (D) Considers the local community. Mindful of preexisting local interests and practices (S) OECD recommendation on the policy coherence of sustainable development (https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-5021, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) Livelihoods that are created through work cultures and practices which are aligned to and appropriate to customs and needs in the surrounding community, that rest on local cultural values and structures | (D) Provides Legal protection. Official protections of rights and freedom, including the right to organise and collectively bargain (S) Relevant legislation, regulations, and union protection (I) livelihoods that are protected by law and the level of access to that protection |

| (D) Protects biodiversity. Flora and fauna (S) ISO/TC (Technical Committee) 331 (https://www.iso.org/committee/8030847.html, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) relevant livelihood sector score (e.g., volume of forest inventory, ratio of growth-to-removals [GRR]), from the Forest Stewardship Council [FSC]) | (D) Promotes DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) Freedom from prejudice and discrimination (S) The Global Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Benchmarks (GDEIB) (https://dileaders.com/gdeib/ The Global Compact https://unglobalcompact.org, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) Livelihoods that promote the fair treatment, dignity, and full participation of all people at work. DEI Officers, HRM roles (DEI Career Centre-Search DEI Jobs and Explore DEI Career Resources) | (D) Delivers Work Justice Distributive, Procedural, Interactive, Informational, Deontic (S) Work Justice Taxonomies (e.g., J. Lefkowitz, 2023, Values and Ethics of Industrial-Organisational Psychology; and https://search.app/UNsGtkqbkpYGo85C9, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) The levels of all forms of work justice found in the livelihood in context |

| (D) Safeguards water (salt and fresh) Access to, efficient use, and protection of clean water (S) Standards of Fresh Water Security (e.g., WASH https://search.app/AbeFWDQ9cyVGfSoS8, accessed on 1 May 2025) Standards for Salt Water (e.g., temperature, acidity, dissolved solids/conductance, turbidity, dissolved oxygen, hardness/ suspended sediments https://search.app/DfKKKmX2iQsX3JiX8, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) relevant livelihood sector score for maritime protections (acidification levels, pollution levels, and reduction in fish stocks, SDG 14) | Protects (future) Generations. No disadvantage for people not yet born (S) Global standards in Social Responsibility IS 26000 (https://www.iso.org/standard/42546.html, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) Livelihoods that are centred/specialising in social responsibility and/or sustainability, e.g., ethical procurement, CRO (Corporate Responsibility Officer) | (D) Allows Work Flexibility Autonomy about workplace workload, when and how to execute work (S) Work–Life Balance (e.g., OECD Better Life Index (https://search.app/7oRKG3Na5Q3bPwLe7, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) Score of work–life balance for livelihood |

| (D) Safeguards land (incl. seabed) Creates and conserves healthy terrestrial environments (S) SDG 15-forest protection, biodiversity, and land conservation (e.g., post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/post-2020-global-biodiversity-framework, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) relevant livelihood sector for protection of natural ecosystems (e.g., mountains, green spaces, seascapes) from degradation. The protection of Mother Earth | (D) Respects Cultures Encourages/Allows for the expression of Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures (S) Cultural Competency Standards (e.g., WHO Global Competency Standards (https://www.who.int/news/item/16-12-2021-new-who-global-competency-standards-aim-to-strengthen-the-health-workforce-and-support-provision-of-quality-health-services-to-refugees-and-migrants, accessed on 1 March 2025) and/or the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (https://www.ohchr.org/en/indigenous-peoples/un-declaration-rights-indigenous-peoples, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) Specific cultural competence standards for livelihood in context | (D) Is Salutogenic (promotes Wellbeing) Physical and mental, according to WHO (S) Healthy Workplaces (e.g., https://search.app/v7jGpbNBbbqn1w3T7, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) livelihoods in which health tends to be promoted and protected (e.g., through policy, access to services, material work conditions, etc.) |

| (D) Safeguards air Creates and conserves healthy air quality (S) Air quality guidelines (e.g., WHO Air Quality Guidelines 2021 https://search.app/wQRisPGgeYH9oY117, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) relevant livelihood sector score for air quality protections (e.g., PM10 https://search.app/5CU1eu93Leu4U19eA, accessed on 1 March 2025) | (D) Respects (Universal) Human Rights (S)The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN, 1948) (I) The local instantiation of the Declaration for livelihood in context | (D) Is Durable (has longevity, context-specific) Offers stability and predictability (S) Relative permanence of work, both type and activity (i.e., tenure, amount of work, and nature of the work). Relevant contracts and/or agreements (I) Livelihoods that have some form of temporal protection and predictability |

| (D) Takes Climate Action directly Work itself combats climate change and its impacts (S) Paris Declaration 1.5 Degrees (I) Livelihood contribution to global warming | (D) Delivers Quality of Life (for Others) (S)UN WHO Quality of Life (WHOQOL). The 4 domains of QOL are physical health, psychological, social relationships, and environment (https://search.app/Vzuv15hKEaSeGzJj8, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) Livelihoods that are focused on 4 domains of life (e.g., doctor/nurse, psychologist, public relations, urban planner) | (D) Delivers Quality of Life (for Self) According to UN WHO guidelines (S) WHOQOL: Measuring Quality of Life (https://search.app/aEfgPibp9w1BkLfa8, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) livelihoods which enhance physical and mental health, social relationships, people’s environments, including digital connectedness |

| (D) Resilient to climate disasters Work is unaffected by climate change (S) Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-30 https://search.app/j1yHqgsnJkNgHpBA6, accessed on 1 March 2025 (I) Livelihood assessment against the Sendai Framework Monitor https://search.app/bkA2Kn6e5gkthnV76, accessed on 1 March 2025 | (D) Is Techno-socially Responsible Responsible and ethical use of technology and technological devices (S) Global and Regional Standards for Technology usage (e.g., World Bank ID4D Technology Standards (https://id4d.worldbank.org/guide/technology-standards, accessed on 1 March 2025 or UN Tech Responsible Playbook https://search.app/EtchEU6DcRAB9MCj8, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) The extent to which the livelihood in context meets tech responsible standards | (D) Is AI replaceable/neutral/enhanced The role of AI at work (S) Jobs of Tomorrow White Paper, World Economic Forum (https://search.app/YnvYSxw3wfUfkWo18, accessed on 1 March 2025) (I) the impacts/exposure to risk that AI has on the relevant livelihood-in-context “Fully replaces some incumbents” (workers in the role) versus “Reduces workloads by aiding incumbents” versus “Irrelevant to job in foreseeable future” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carr, S.; Hopner, V.; Meyer, I.; Di Fabio, A.; Scott, J.; Matuschek, I.; Blake, D.; Saxena, M.; Saner, R.; Saner-Yiu, L.; et al. The Wheel of Work and the Sustainable Livelihoods Index (SL-I). Sustainability 2025, 17, 6295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146295

Carr S, Hopner V, Meyer I, Di Fabio A, Scott J, Matuschek I, Blake D, Saxena M, Saner R, Saner-Yiu L, et al. The Wheel of Work and the Sustainable Livelihoods Index (SL-I). Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146295

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarr, Stuart, Veronica Hopner, Ines Meyer, Annamaria Di Fabio, John Scott, Ingo Matuschek, Denise Blake, Mahima Saxena, Raymond Saner, Lichia Saner-Yiu, and et al. 2025. "The Wheel of Work and the Sustainable Livelihoods Index (SL-I)" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146295

APA StyleCarr, S., Hopner, V., Meyer, I., Di Fabio, A., Scott, J., Matuschek, I., Blake, D., Saxena, M., Saner, R., Saner-Yiu, L., Massola, G., Atkins, S. G., Reichman, W., Saltzman, J., McWha-Hermann, I., Tchagneno, C., Searle, R., Mukerjee, J., Blustein, D., ... Haar, J. (2025). The Wheel of Work and the Sustainable Livelihoods Index (SL-I). Sustainability, 17(14), 6295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146295