1. Introduction

As emphasized in the United Nations’ latest global climate report, CO

2 emissions (hereafter CO

2) threaten sustainable development and high-welfare societies [

1]. Reducing these emissions without undermining economic stability has thus become a key global priority. While interest in environmental challenges and the roots of CO

2 is not new, it has grown significantly in recent years [

2]. Early studies from the 1990s focused mainly on economic drivers such as GDP and energy use [

3,

4]. Since then, a broader set of economic, social, and political factors have been examined to explain environmental pressures better. These include oil prices [

5], renewable energy [

6], financial development [

7], FDI [

8], green technology [

9], urbanization [

10], population [

11], well-being [

12], income inequality [

13], digital economy [

14], geopolitical risk [

15], institutional quality [

16], and democracy [

17].

Expanding the extensive literature examining the drivers of CO

2, focusing on new and current variables/factors, provides insights into the significance of the issue [

18,

19]. Despite the broad coverage and substantial interest, it cannot be claimed that the relevant literature could be more flawless. A firm belief in the economic causation of environmental degradation has led economic factors to dominate a significant portion of the literature [

20]. However, political scientists and political economists heavily criticize the literature for its obsessive focus on economic factors. It is particularly noted that an obsessive focus on economic factors will neglect the politically driven drivers of environmental degradation [

4]. The most crucial reason behind this objection is the recognition that well-designed and efficient environmental policies shaped by democratic institutions will serve as a significant catalyst in reducing CO

2 [

21,

22,

23]. With the increasing attention to the potential effects of political factors on the environment, political/institutional factors such as corruption control, ideologies, law, transparency, democracy, civil rights, and political rights have gradually become more integrated into the literature [

17,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. A significant portion of these studies has indicated that the institutional framework and democratic principles have the potential to boost environmental awareness and reduce CO

2 by implementing effective environmental policies.

The growing inclusion of democracy and institutional quality in environmental economics has enhanced our understanding of the political roots of CO

2. However, micro-level political dimensions remain underexplored, particularly regarding specific variables such as freedom of association and organization (hereafter AOF). Although various political indicators have been linked to CO

2, the role of AOF—a fundamental component of democratic societies—has been largely overlooked. As defined by Freedom House [

30], AOF includes the right to peaceful protest, participation in civil society, the use of online platforms for advocacy, and the formation of unions and professional organizations. These freedoms are essential for democratic governance and can influence environmental outcomes by enabling public protest against ecological harm, supporting environmental advocacy, and facilitating the creation of environmental groups. AOF can raise awareness through these channels and help prevent environmentally damaging activities.

The lack of examination of the impact of AOF on CO

2, despite its potential effects on environmental quality, creates a gap in the comprehensive literature focusing on the determinants of environmental degradation. This gap, in a sense, presents an exciting research question and opens up a new research avenue for environmental economists: Could the development of AOF be a strategic key to reducing CO

2, which has historically reached its highest levels by fostering quality environmental awareness and demand? This work seeks to address this question by claiming that AOF could be a crucial key. The main objective of this study is to unveil the impact of AOF on CO

2 for the top 20 emitter countries (TECs) (Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Iran, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Poland, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States, Vietnam) during the period 2006–2022. While this study is specific to a political element, it does not overlook the critical drivers of CO

2. Economic growth, energy use, and trade openness are considered among the most critical economic reasons for environmental degradation in many studies [

31,

32,

33].

This research aims to enhance the existing literature on the key factors influencing CO2 through multiple contributions. This study makes three significant contributions to the literature on environmental political economy. The first contribution is related to the primary independent variable. As mentioned, the impact of many factors of socioeconomic and political origin on CO2 has been investigated for a long time. While there has been a growing focus on the role of political and institutional factors in determining CO2 in recent years, the number of studies is relatively low. This situation needs to include a clear identification of the impression of political factors on the environment. While there are studies examining the impact of democracy and institutional quality on CO2, as far as it is known, no study explicitly investigates the effect of AOF on CO2. Therefore, this work is groundbreaking in highlighting the distinct contribution of AOF to explaining CO2. Second, the findings carry important policy implications, particularly for countries striving to balance environmental sustainability with economic growth. The focus on TECs is crucial in this context, as these nations represent the largest share of global emissions and thus hold significant influence over environmental outcomes. By focusing on this group, this study targets key players whose policy changes can have a meaningful impact on global efforts to reduce emissions. Suppose AOF is found to reduce CO2. In that case, it offers policymakers a dual advantage—advancing democratic norms while achieving environmental objectives—thus presenting a potential “win-win” strategy in pursuing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Third, this study enhances methodological rigor by employing second-generation panel techniques that account for cross-sectional dependence (CSD), a limitation often neglected in the existing literature. Using the Augmented Mean Group (AMG) and Common Correlated Effects Mean Group (CCEMG) estimators, the analysis ensures more robust and reliable inferences, strengthening the empirical foundations of this study’s conclusions.

The subsequent sections present the literature, model, empirical approach, results, discussion, conclusions, and policy implications.

2. Potential Mechanisms Between AOF and the Environment

Democracy is widely recognized as a key political determinant of environmental quality [

25]. While its overall influence has been extensively debated, the specific role of AOF—a critical dimension of democratic governance—remains underexplored. According to [

30,

34], AOF represents a fundamental component of civil liberties, encompassing three main domains: freedom of assembly, freedom of nongovernmental organizations, and freedom of trade unions and professional associations. These components collectively reflect the broader institutional environment in which civil society actors, including environmental organizations, can operate, mobilize, and influence policy [

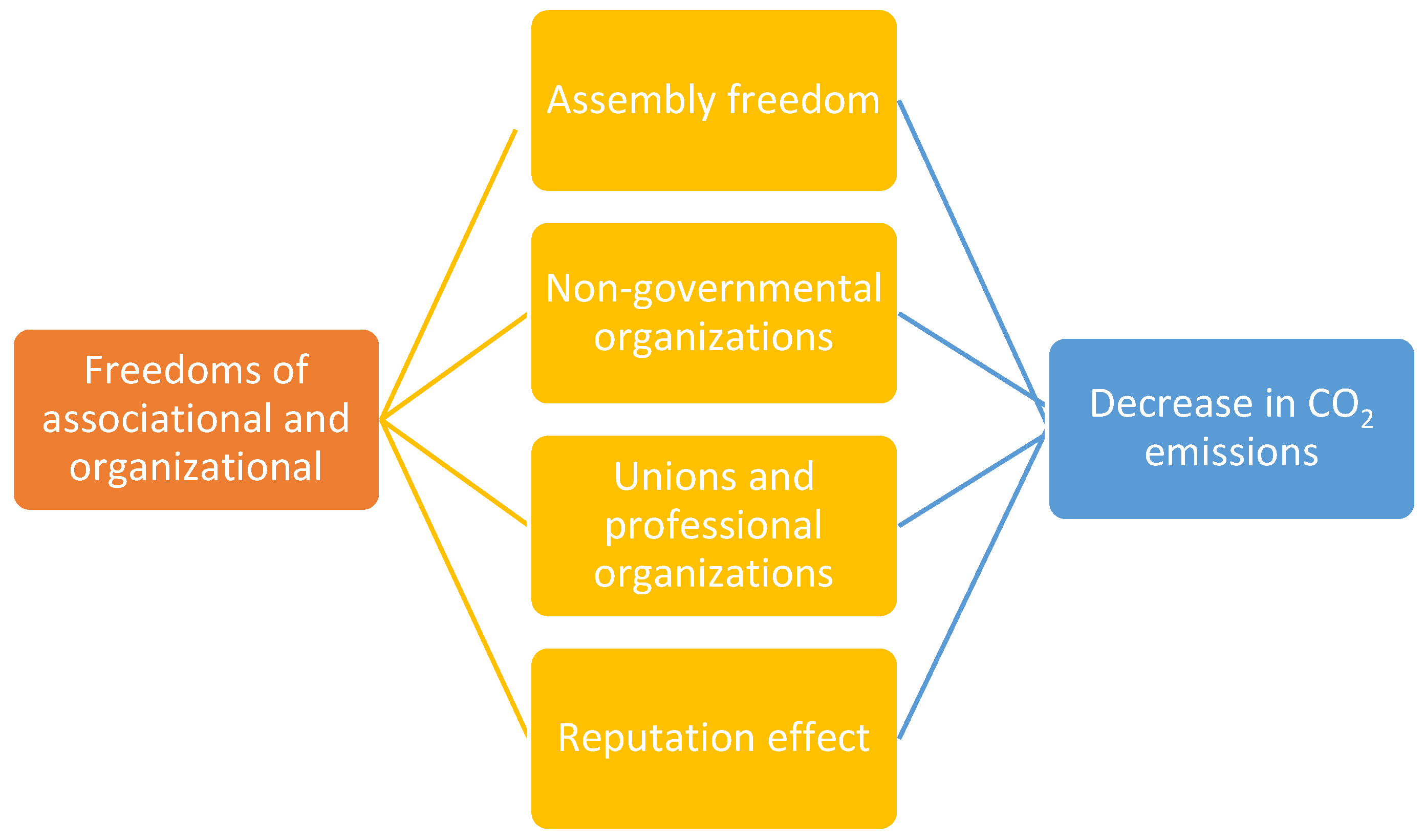

4]. Beyond the institutional mechanisms defined by Freedom House, this study also considers the reputation effect as an additional potential pathway. Countries that uphold stronger associational freedoms may benefit from greater international legitimacy and credibility, which can enhance their engagement with global environmental norms and agreements. As illustrated in

Figure 1, these elements together constitute the theoretical foundation for understanding how AOF might plausibly influence CO

2.

Assembly freedom focuses on the extent to which organizing peaceful protests and demonstrations, including political ones, is free. For instance, the difficulty of organizing such gatherings and whether participants feel threatened with actions like arrest are crucial considerations. Additionally, components of assembly freedom include citizens’ ability to gather signatures to support a particular policy or initiative and freely announce these activities in online media. Similarly, it is essential for democracy that civil society organizations are not restricted, and citizens can join them as they wish [

30]. Furthermore, the ability of civil society organizations to raise funds and donors to contribute without feeling any pressure is crucial. Lastly, the freedom of unions and professional organizations to operate without government intervention and for individuals to join these organizations freely is indispensable for organizational freedom. The ability of professional organizations to operate freely without succumbing to government and business pressures falls within this scope [

35,

36].

When reviewing the literature demonstrating the potential positive effects of democracy and institutional quality on the environment, it can be said that AOF has specific merits that could improve environmental quality. Firstly, assembly freedom allows environmental organizations to organize peaceful demonstrations and protests. The opportunity for members and citizens to participate in these events without feeling pressured can send a message to businesses and governments about reducing environmental degradation [

37]. Emphasizing the demand for a quality environment through peaceful demonstrations can pressure businesses and governments, compelling them to implement environmentally friendly measures. For example, highlighting the demand for a quality environment through peaceful demonstrations can prevent activities/projects with ecologically adverse effects through public pressure. Additionally, such demonstrations and protests can influence wider audiences, increasing environmental awareness and sensitivity in society [

38].

Secondly, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can be crucial in halting environmental degradation [

39]. The unrestricted activities of environmental NGOs and the non-coercion of their members can generate significant environmental outcomes. Environmental organizations disseminate global environmental standards and awareness to the broader public [

40]. In addition to environmental awareness, NGOs can prevent an increase in environmental degradation by ceasing activities in sectors causing environmental damage, such as mining [

41]. In other words, environmental NGOs can influence decisions with positive environmental impacts by exerting pressure on producers, policymakers, and the legal system. According to [

42], these organizations can set the agenda on environmental hazards and mediate their resolution through negotiated policies. As evident, NGOs operating within the framework of AOF can have significant potential effects on determining environmental norms and hazards, fostering environmental awareness, and shaping functional environmental legislation and policies. All of these factors can strongly impact environmental quality.

The unrestricted operation of unions and professional organizations can influence environmental issues. In this category, particularly crucial is the independence of professional organizations from businesses and governments in their activities and decision-making processes [

30,

34]. Professional organizations can contribute to policy-making processes related to environmental issues and impact environmental regulations. For instance, ref. [

43] notes the significant contributions of civil engineers in the United States to shaping environmental policies. In this context, they can influence environmental policies in various areas, such as developing environmental technologies and modernizing waste management. On the other hand, if professional organizations like engineers are under the influence of the government and business, it may hinder the creation of merit-based decisions and policies. As highlighted by [

22,

44], through lobbying activities, traditional energy companies can secure approval from professional organizations for projects with adverse environmental effects and impede the development of green technologies. Therefore, researchers and professional organizations must be free to express ideas, share knowledge, and conduct research in their respective fields of expertise [

45]. Ensuring that unions and similar professional organizations remain unaffected by external pressures enhances transparency and accountability, ultimately promoting meritocracy. This, in turn, facilitates the design of efficient environmental policies and improving environmental quality.

The fourth channel could be the mentioned reputation effect [

46]. This channel suggests that the positive global image of democratic countries can have environmental consequences. As mentioned, AOF is a significant element of democracy. Restrictions on AOF may indicate an erosion of democracy and convey a negative message to the global public. Tendencies toward authoritarianism can hinder international investments [

47,

48]. At this point, a link is established between AOF and the environment. According to [

37], shifting from democracy to authoritarianism can reduce investments in clean energy and green innovation by intimidating international investors. This pessimistic scenario can increase CO

2 and ecological pressure. Moreover, distancing from democracy could inevitably mean a detachment from the world. Such countries may refrain from signing multilateral environmental agreements. Additionally, a detachment from the world and global issues may prevent the use of financial support from international organizations for environmental and clean energy technologies. All these developments, forsaking the AOF, can pressure the environment in several aspects, as will be seen.

While a specific theory may not outline how AOF could impact environmental quality, its subcomponents could reasonably and plausibly affect the environment.

Figure 1 provides a general overview of the potential interaction mechanisms of AOF on CO

2. In this framework, the connection between AOF and CO

2 can be built through the freedom of assembly, civil society organizations, unions/professional organizations, and reputation effects—and their subcomponents.

In addition, it is acknowledged that the activities supported by AOF are not limited to environmental causes; they also extend to areas such as education, public health, and human rights. However, this study does not aim to isolate pro-environmental activism specifically due to the lack of globally comparable data on the number, scope, and perception of such activities. Instead, the analysis focuses on the broader institutional environment in which civil society, including environmental actors, can operate and exert influence. When reviewing the literature demonstrating the potential positive effects of democracy and institutional quality on the environment, it can be said that AOF has specific merits that could improve environmental quality.

3. Literature Review

Grossman and Krueger [

3,

49] associated economic growth/income levels with environmental degradation in their studies on the environmental Kuznets curve. Subsequently, a growing body of literature has indicated that economic factors can significantly affect the environment [

32]. Gorus and Aslan [

20] noted that the undeniable effects of economic phenomena on the environment have often led the literature to be predominantly built upon economic aspects. However, the persistent challenge of preventing environmental degradation has created a belief that focusing solely on economic factors may lead to incomplete deductions. Researchers examining the interaction between economics and politics have emphasized the problematic nature of overlooking the political origins of environmental degradation [

4]. Notably, the centrality of democracy and institutional quality in resolving many economic, political, and social issues [

50,

51] has facilitated the integration of such political factors into environmental economics [

52,

53]. These discussions are mainly grounded in theories of institutions and democracy [

48,

54,

55], which suggest that stronger institutions and democratic accountability mechanisms enable the design and enforcement of more effective environmental policies [

56].

In the realm of political factors, institutional quality stands out prominently. Many studies have explored how institutional quality influences CO

2, emphasizing factors like legal frameworks, corruption, transparency, accountability, and overall governance. Much of the literature has proved that institutions can improve environmental quality through environmental regulations and policies. For instance, ref. [

57] found that institutional reforms improved environmental quality and mitigated the adverse effects of trade openness in 40 African countries. Ref. [

58] indicated that the rule of law successfully reduced CO

2 due to economic growth in Indonesia, Thailand, and South Korea. Ref. [

59] demonstrated that institutional factors such as law, transparency, governance, and economic freedom softened energy consumption and reduced CO

2 in 39 developing countries. Ref. [

60] explored the impact of economic and political factors on the environment, revealing that both income and corruption control succeeded in reducing CO

2 in Africa. In a study measuring institutional quality with corruption, ref. [

21] researched the components of CO

2 in 145 countries, finding that lower corruption led to lower CO

2. Ref. [

61] investigated the link between governance and CO

2 in developing nations, concluding that governance successfully reduced CO

2 in the whole panel and subpanels. In an analysis of BRICS countries, ref. [

62] found that a decrease in corruption and institutional indicators, such as a solid legal system and bureaucratic quality, decreased CO

2. Ref. [

63] tested political factors of CO

2 in 136 nations, identifying law as the most crucial factor among various institutional quality indicators in reducing CO

2.

Besides studies demonstrating that institutional quality reduces CO

2, initiatives also present contrary evidence. As examples from the recent literature, ref. [

64] examined the environmental impacts of institutions in Pakistan using time-series methods. They found that enhanced institutional quality increased CO

2 through economic growth. Ref. [

65] indicated that institutional quality represented by government effectiveness increased CO

2 in Pakistan. Ref. [

66] discovered that institutions represented by ‘law and order’ increased CO

2 in 25 African countries. Ref. [

26] concluded that institutional quality increased CO

2 in 42 developing countries. Ref. [

67] tested the impact of economic and political factors on CO

2 in selected South Asian countries and pointed out that institutional quality increased CO

2. Ref. [

16] investigated how institutional quality and technological innovation influence CO

2 in 10 Asian nations, finding that enhanced institutional quality led to increased emissions.

The literature examining the political origins of environmental degradation identifies democracy as another crucial factor. Recently, there has been increased interest in the specific impact of democracy, particularly on CO

2. One of the pioneering studies, ref. [

68], researched the connection between various environmental metrics, including CO

2, and democracy. The outputs of the work revealed the function of democracy in reducing emissions. Ref. [

69] examined the influence of urbanization and political factors on CO

2 in Africa, testing 38 countries. The study concluded that democracy and bureaucratic quality negatively influenced CO

2. Ref. [

70] explored the impression of democracy and corruption on CO

2 across 144 nations. The results indicated that improving democracy at low corruption levels reduced CO

2. Ref. [

25] used civil liberties and political rights as indicators of democracy in an influential study. In the context of developing countries, democracy indicators were successful in reducing CO

2. Ref. [

71] investigated the political origins of CO

2 in 69 countries, showing that democracy reduced CO

2, thus improving environmental situation in panel countries. Ref. [

72] examined the connection between democracy and CO

2 in 45 African countries, demonstrating that democracy reduced CO

2 in low- and high-emission countries. Ref. [

17] tested the impact of democratic elements on CO

2 for a panel of countries. Within this framework, it was found that civil society participation, which is a key element of AOF, significantly contributes to the reduction of emissions. These results align with theories of participatory governance, which suggest that democratic mechanisms enhance accountability and pressure governments to adopt environmentally sound policies.

Some studies find a positive link between democracy and CO

2. Ref. [

53] researched the political factors of CO

2 in Soviet nations, revealing that political democracy and economic freedom increased CO

2. Ref. [

73] conducted a study using data from 120 countries, concluding that emissions tended to be higher during increased democratic scores. Ref. [

52] demonstrated that in low-income countries, democratic development was associated with higher emissions. Ref. [

74] tested the relationship between democratic indicators and CO

2 in Sub-Saharan Africa, with results indicating that improvements in democratic practices increased CO

2. Ref. [

75] researched the drivers of CO

2 in MINT nations, designating democracy as having a particular function and finding that democracy accelerates CO

2 by stimulating economic operations. In a distinctive approach, ref. [

29] asymmetrically researched the connection between democracy and CO

2, with findings from Bangladesh indicating that positive changes in democracy positively affected CO

2.

As observed, studies exploring the political determinants of CO

2 have placed particular emphasis on democracy and institutional quality. Nevertheless, there is no agreement regarding the environmental impacts of these two factors. In addition to these factors, government ideology has been studied as another leading political factor. For instance, ref. [

24] investigated the impact of government ideology on CO

2 in 19 OECD countries, finding that governments with a left-wing ideology were more successful in reducing CO

2 than right-wing ones. Ref. [

76] examined the influence of political ideology and party structures on CO

2 in 85 countries, with empirical analysis showing that left-wing governments and parties prioritized environmental quality more. Ref. [

77] studied the relationship between ideology and the environment in 65 countries. Despite heterogeneous findings, the study demonstrated that left-wing ideology was associated with lower emissions. Ref. [

27] explored the relationship between political ideology and greenhouse gas emissions in 98 countries. Similar to other studies, the results indicated the significance of ideological differences in emissions, with left-wing governments exhibiting lower CO

2. The literature focusing on ideology generally suggests that left-wing governments prioritize environmental quality and are more successful in reducing CO

2.

On the other hand, the impact of political and economic freedoms on environmental quality has been extensively studied. Ref. [

78] focused on the impact of economic freedoms on the environment and health for a panel of countries. The researchers demonstrated that economic freedoms were successful in reducing CO

2. Ref. [

79] tested the relationship between renewable energy and economic freedoms in the European Union. The findings indicated a U-shaped relationship between economic freedoms and CO

2. Ref. [

80] examined the influence of economic freedoms on CO

2, focusing on Europe similarly to [

79]. The results showed that economic freedoms were highly heterogeneous across countries. In addition to economic and political freedoms, several recent studies have explored the impact of press freedom on CO

2. For example, refs. [

37,

81] tested the impression of press freedom on CO

2 and other environmental indicators in both developed and developing countries, and they found that press freedom plays a significant role in enhancing environmental quality.

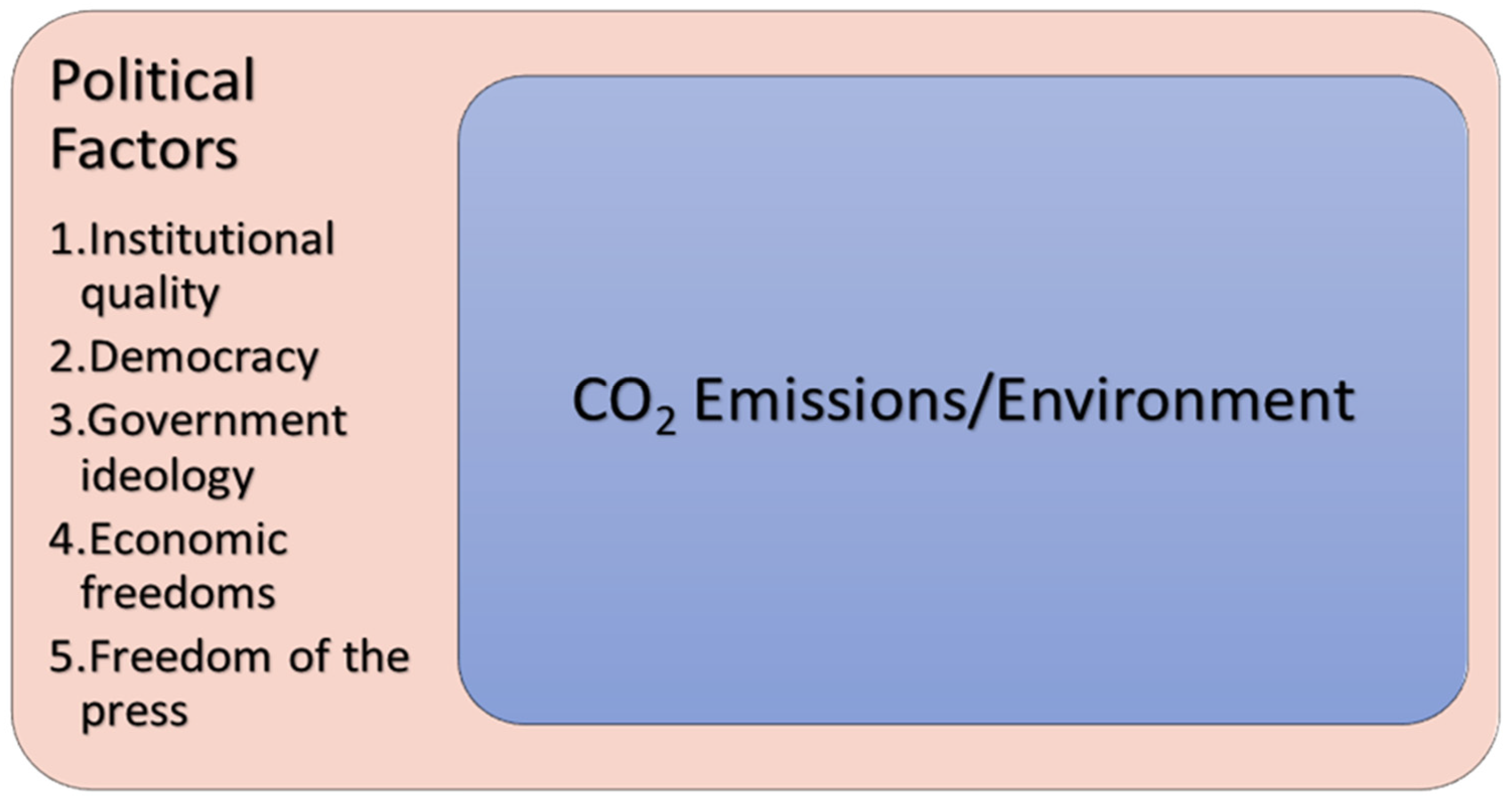

Figure 2 broadly reflects the political/institutional variables frequently examined in the literature, facilitating the identification of gaps in the literature. Institutional quality, democracy, ideology, economic–political freedoms, and press freedom have been investigated as fundamental independent variables in explaining CO

2. Such political elements are considered highly insightful in explaining CO

2. However, some crucial indicators of political development, such as AOF, still need to be directly associated with the environment. Although there are studies examining the impact of civil liberties encompassing AOF on CO

2 (see [

23]), specifically investigating the effect of AOF on CO

2 has not been conducted. Therefore, based on the theoretical foundations of participatory governance and environmental institutionalism, this study aims to fill this gap by investigating AOF’s impact on CO

2.

In line with the reviewed literature and theoretical expectations, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: AOF, serving as a measure of democracy and institutional quality, reduces CO2.

This hypothesis builds on the notion that greater freedom of association strengthens civil society, enhances public participation in environmental decision-making, and increases governmental accountability, fostering more effective and environmentally sustainable policies.

4. Data and Methodology

The research question of this work is to determine whether there is an impact of AOF on CO

2 in the TECs. In this context, AOF is given specific importance in explaining CO

2. Additionally, to comprehensively explain CO

2 and ensure critical variables are not overlooked, GDP, primary energy consumption, and trade openness, which are frequently associated with CO

2 in the literature, are included in the model. Since AOF data is available for 2006–2022, the analysis is limited to this period. Logarithmic transformations have been applied to all variables; the data is annual. Equation (1) specifies the relationship between CO

2, AOF, and the set of control variables and is derived by adapting the empirical frameworks commonly employed in studies exploring the democracy–environment nexus, such as [

4,

17,

25,

57], among others.

CO

2 represents carbon dioxide emissions in millions of tons. GDP is included in the model to represent economic growth and is presented as GDP per capita. PEC reflects primary energy consumption in exajoules. Finally, TRD represents trade openness as a percentage of GDP.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of definitions, values, and source information related to the variables.

AOF is the leading independent variable in the research. The data is obtained from [

30], which constructs the associational and organizational rights index based on three equally weighted subcomponents: (i) freedom of assembly, (ii) freedom for nongovernmental organizations (particularly those working on human rights and governance issues), and (iii) freedom for trade unions and similar professional or labor organizations. Each subcomponent is rated on a scale from 0 to 4, resulting in a total AOF score ranging from 0 to 12, with 12 indicating the highest level of freedom. These subcomponents capture key aspects, including the right to organize peaceful protests, legal constraints on NGO registration and funding, and the ability of trade unions to operate and bargain collectively [

30,

34]. While AOF does not specifically isolate environmentally focused organizations, it reflects the broader enabling environment in which civil society, including environmental actors, can operate, mobilize, and influence policy.

Table 2 provides comprehensive descriptive statistics for the TEC panel. In summary, CO

2 range from a minimum of 73.33 mt (Vietnam) to a maximum of 10,563.47 mt (China). For AOF, the minimum and maximum values are 12.0 and 1.0, respectively, with higher scores generally belonging to developed countries within the TEC panel. The lowest scores in the panel are attributed to Vietnam and Iran. Regarding GDP, the maximum value is 62,866.7 (United States), and the minimum is 1008.6 (India). Not surprisingly, China has the highest PEC value in the panel at 159.3, while Vietnam has the lowest at 1.22. Despite having minimum values in most categories, Vietnam has the highest trade openness at 186%. The lowest trade openness value is 22%, belonging to Brazil.

Additionally,

Table 2 reports the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values to assess multicollinearity among explanatory variables. The VIF values for all variables are well below the commonly accepted threshold of 5, with the mean VIF at 1.52. This suggests that multicollinearity is not a concern in the regression model and that the estimates are unlikely to be biased due to strong correlations among the predictors.

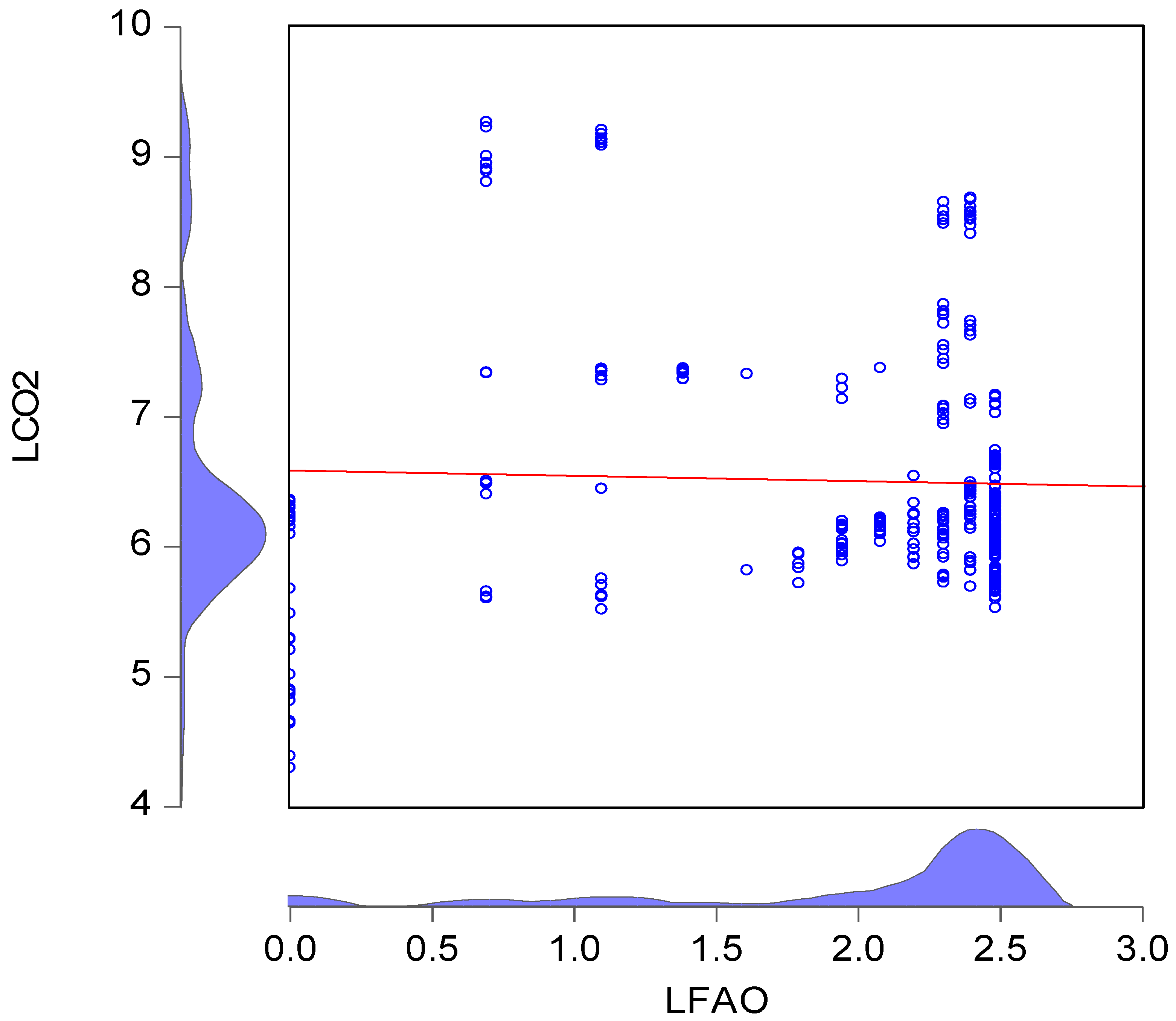

Firstly, to illustrate the intuitive relationship between CO

2 and AOF, the scatter plot of AOF against CO

2, along with the relevant fitted line, can be observed in

Figure 3. As evident, the fitted line has a negative slope, indicating a negative correlation between AOF and CO

2. The kernel density also suggests that at higher levels of AOF, CO

2 tends to be lower. However, more advanced and reliable econometric methods are necessary to explore this negative correlation explicitly.

Ensuring trustworthy estimations requires the utilization of solid econometric techniques. The first step in applying reliable methods involves the assessment of CSD. Determining if the series shows CSD is crucial. Skipping CSD analysis initially can bias econometric results. For example, the results will lack precision if CSD is present and the unit root test performed without considering CSD needs to be more precise. This work employs three widely recognized tests: the Breusch and Pagan LM test [

83], the Pesaran CDLM test [

84], and the Pesaran et al. [

85] LMadj test. Additionally, evaluating slope homogeneity is crucial when CSD is present. Panel data units can interact, leading to varying slope characteristics. Therefore, verifying slope homogeneity is essential for accurate estimation results. Swamy’s [

86] initial research into homogeneity has been expanded with contributions from [

87]. This homogeneity test is utilized in this study.

Following the analysis of CSD and homogeneity, the next phase is to perform a unit root test. The outcomes of the CSD tests play a crucial role in determining the appropriate unit root test. If CSD is identified in the series, the chosen unit root test must account for this factor. Neglecting CSD during analysis can lead to the incorrect determination of variable stationary levels, potentially causing biased results in subsequent stages of the econometric process. Therefore, this study utilizes Pesaran’s [

88] CADF test, which incorporates CSD considerations, to assess the presence of unit roots in the variables.

Before proceeding to the estimation of long-run coefficients, this study conducts a panel cointegration analysis to mitigate the risk of spurious regression, particularly given the integrated nature of the variables. To this end, the Durbin–Hausman (DH) test, as refined by [

89], is employed. The DH test is especially suitable for panels characterized by cross-sectional dependence, as it explicitly accounts for standard shocks and interdependencies across units—features commonly observed in macro-panel data. Additionally, unlike conventional methods, this approach does not require all series to be of the same integration order, allowing for a more flexible and robust testing environment. The test also distinguishes between heterogeneous and homogeneous autoregressive dynamics, providing richer insight into the structure of long-term relationships. By verifying the presence of cointegration prior to implementing long-run estimators, the analysis ensures that the subsequent findings reflect genuine equilibrium relationships rather than statistical artefacts.

In this study’s concluding phase of the econometric process, the long-run effects of AOF, GDP, PEC, and TRD on CO

2 are examined. In this context, the Augmented Mean Group (AMG) estimator proposed by [

90,

91] as well as the Common Correlated Effects Mean Group (CCEMG) estimator developed by [

92], are employed to identify the long-term relationship. The selection of AMG and CCEMG for establishing a reliable long-term relationship is based on specific justifications. Both estimators offer significant advantages for researchers within the framework of their characteristics [

93]. CSD induces inefficiency in first-generation econometric tools like fixed and random effects, potentially leading to biased outcomes [

94]. By providing second-generation forecasts, AMG and CCEMG acknowledge the existence of CSD and offer robust and reliable predictions even when CSD is present. Additionally, both estimators demonstrate high predictive efficiency in cases of heterogeneity. In contrast to certain conventional techniques, these estimators do not place restrictions on the unit root properties of the variables. Furthermore, they yield effective results even in situations without integration [

4]. The credibility of AMG and CCEMG stems from their capacity to improve the accuracy of results, particularly when dealing with issues like endogeneity, non-stationarity, CSD, and heterogeneity [

95].

5. Results

The first phase of this analysis includes investigating CSD and slope homogeneity.

Table 3 reports the output from the relevant tests. Firstly, the null hypothesis suggesting the absence of CSD is rejected in the three widely used tests in the literature. In other words, the findings indicate the presence of CSD in the TECs. The existence of CSD implies that any economic shock occurring in a country within the TECs may have implications for other TECs. In fact, in the increasingly globalized world economy, it is entirely plausible for such a relationship to exist among countries with high production capacity and significant economic cooperation.

If CSD exists, it becomes critical to ascertain the homogeneity of slopes. This is essential due to the potential interactions among panel data units that may lead to slope variations. Ensuring the homogeneity of slopes is integral for obtaining reliable and robust estimation results. The test outcomes are presented in

Table 3, where the null hypothesis suggests homogeneous slope coefficients. The test statistics reject the null hypothesis, indicating the heterogeneity of slope coefficients among the units in the model.

An essential part of the empirical procedure is the unit root examination. Immediately, previous analyses had revealed the presence of CSD in the TEC panel. Therefore, choosing a unit root test that considers this issue is critical. Otherwise, unit root tests that do not control for CSD may give erroneous results. Hence, it is functional to implement a procedure consistent with this information. The CADF test developed by [

88] is a second-generation analysis that controls CSD. The results presented in

Table 4 indicate that all variables have unit roots. Nonetheless, all variables reach stationarity after applying their first differences. In these scenarios, it is essential to utilize second-generation methods that consider CSD to ensure the reliability and robustness of the findings.

Given the presence of cross-sectional dependence and the integration properties of the variables, the application of the DH cointegration test is justified. As reported in

Table 5, the test statistics exceed the corresponding critical values, leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis of no cointegration. These findings confirm the existence of a long-run equilibrium relationship among the variables. This outcome provides a robust foundation for proceeding with the estimation of long-run coefficients using appropriate econometric techniques.

The concluding phase of econometric analysis entails the determination of the long-term relationship.

Table 6 illustrates the influence of AOF, GDP, PEC, and TRD on CO

2 for the entire panel, based on insights derived from the AMG and CCEMG estimators. The fundamental independent variable of this study, AOF, as expected, has a negative and statistically significant impact on CO

2. According to the findings obtained from both estimators, a 1% increase in AOF reduces CO

2 by 0.072–0.097%. This output suggests that with the assurance/expansion of AOF, environmental awareness, responsibility, demand for a quality environment, and merit-based environmental policies are realized in TECs. While there is no study directly examining the impact of AOF in the previous literature, these findings appear to be entirely consistent with studies such as [

23,

25,

71,

72], which concluded that civil liberties, political rights, and democracy indices reduce CO

2.

When examining the impact of economic factors on the TEC panel, both estimators consistently indicate that GDP is positive and significant. In this context, a 1% increase in GDP results in a CO

2 increase ranging from 0.281 to 0.384%. This finding is consistent with studies that identify a positive relationship, such as [

5,

63,

66]. The positive link between GDP and CO

2 implies that economic growth in TECs comes with environmental costs, indicating that the growth process is not entirely environmentally and nature-friendly. Considering that these countries are among the top 20 emitters globally, growth leads to significant emissions, causing harm to the environment.

The findings demonstrate that the most significant influence on CO

2 in TECs is attributed to PEC. According to the AMG and CCEMG estimators, a 1% increase in PEC increases CO

2 by 0.968% and 1.006%, respectively. As observed, the most significant coefficient in the panel belongs to PEC. This finding is in line with the majority of studies in the literature, such as [

6,

8,

75,

96]. Even though almost all TECs possess significant economic and technological capabilities for deploying renewable energy, it is evident that they have yet to be entirely successful. While the share of clean energy is increasing, the still-high levels of traditional energy consumption prevent environmental costs from being reduced to satisfactory levels.

TRD is the only variable within the model that lacks statistical significance. The coefficient for TRD is consistently positive and insignificant in both estimators. Although, according to AMG, a 1% increase in TRD would result in a 0.014% increase in CO

2, the coefficient is not statistically significant. Similarly, the long-term coefficient obtained for TRD from CCEMG is positive and insignificant, resembling the results from AMG. While this finding lacks statistical significance, it partially aligns with studies in the literature that have found a positive connection between TRD and CO

2, such as [

37,

57,

62]. Additionally, it is consistent with the positive and insignificant relationship between TRD and CO

2 identified by [

97] for oil-exporting countries. This result indicates that, in the examined 20 countries, TRD, which is expected to have a significant impact on CO

2 in terms of scale, composition, and technology, does not exert a sufficiently solid and significant influence on CO

2.

To assess the robustness of the main findings, the Cross-Sectionally Augmented Autoregressive Distributed Lag (CS-ARDL) model proposed by [

98] was employed. This approach accounts for unobserved common factors and cross-sectional dependence, making it particularly suitable for macro-panel data that may exhibit potential heterogeneity and endogeneity concerns. The results, presented in

Table 7, confirm the baseline findings obtained through AMG and CCEMG estimators, thereby reinforcing the reliability of this study’s conclusions.

Given the heterogeneity in political and economic structures across TECs, separating them by development level enhances the robustness of the analysis.

Table 8 presents long-run AMG and CCEMG estimates for developed (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Poland, South Korea, United Kingdom, and United States) and developing countries (Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Iran, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, Turkey, and Vietnam). Results show that AOF has a consistently negative impact on CO

2 in both groups, while GDP and PEC exhibit strong positive effects, reinforcing the findings of the whole-panel analysis.

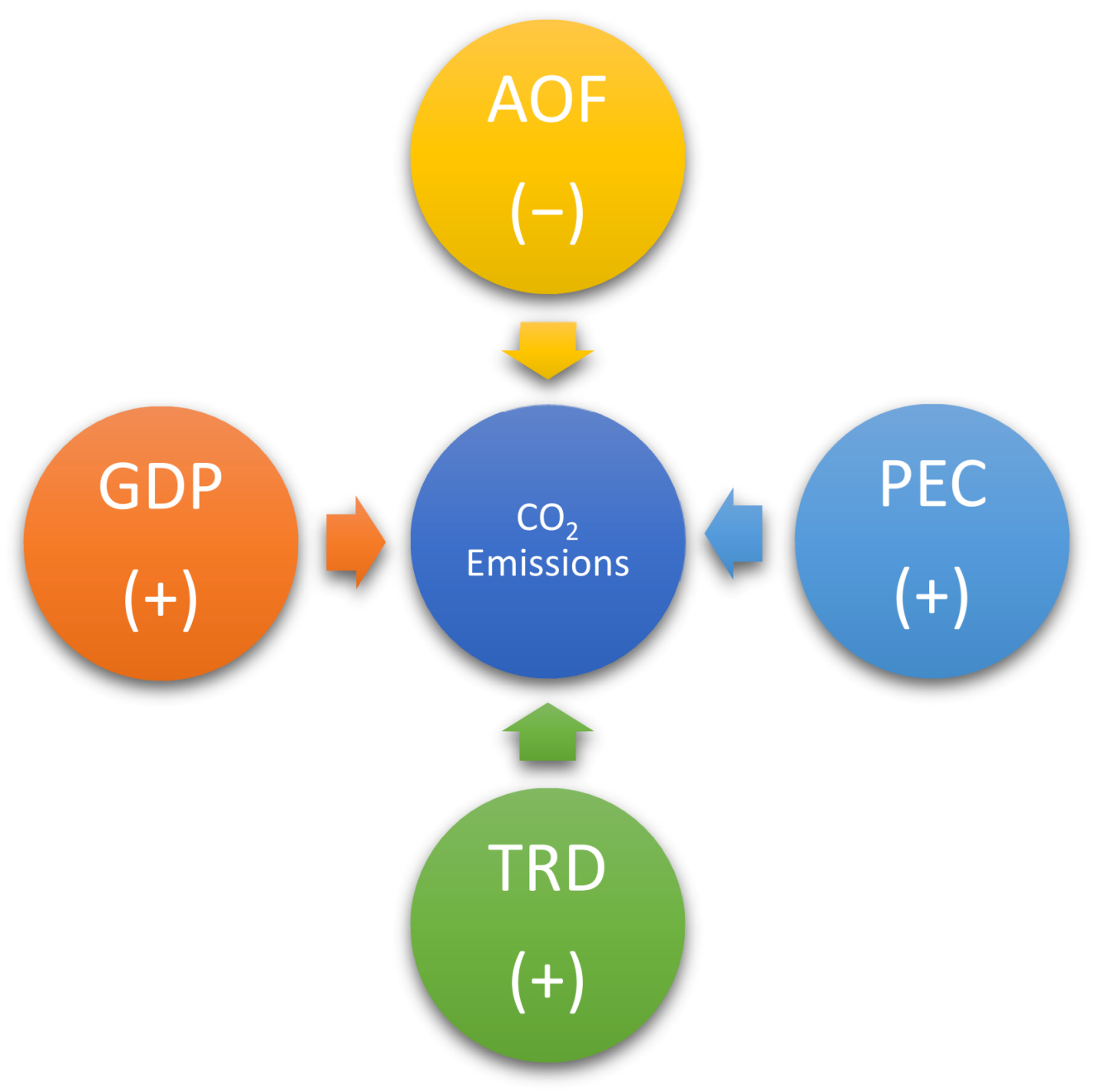

Figure 4 summarizes the long-term impact of AOF, GDP, PEC, and TRD on CO

2. Findings derived from AMG and CCEMG are highly consistent and reliable regarding coefficient signs, magnitudes, and significance. In line with logical expectations, AOF demonstrates the ability to reduce CO

2, presenting significant opportunities for enhancing democracy and improving environmental quality in TECs. Implementing democratic channels could effectively mitigate environmental degradation. On the other hand, it can be asserted that economic factors exert the most significant pressure on CO

2 in panel countries. Both GDP and PEC strongly contribute to CO

2 increases. These results provide policymakers with signals to reconsider growth and energy policies.

6. Discussion

This section provides a deeper analysis of the results. A key finding of this study is the significant adverse effect of AOF on CO

2. For instance, ref. [

72,

99] have stated that democracy reduces CO

2 in African nations. Similarly, ref. [

17,

100] have emphasized the significant capacity of civil society and democracy in reducing CO

2. These findings align well with the results found for TECs. AOF could play a functional role in reducing CO

2 in TECs. Intuitively, one would expect AOF to reduce CO

2, which has been confirmed with more advanced econometric tools. The mean value of AOF in the examined countries is 8.82, which can be considered a noteworthy score. In other words, AOF is generally not constrained across the entire panel. This situation does not restrict organizational, assembly, and protest freedoms related to environmental degradation, allowing people to demand urgent government action against environmental degradation.

As [

101] has pointed out, public demonstrations, marches, school strikes, boycotts, and climate lawsuits, among various forms of climate activism and actions, are present in many parts of the world. It is widely accepted that such public protests by environmental organizations and activists are among the most effective methods to increase environmental awareness and consciousness [

102,

103]. However, ref. [

30,

94] note significant repression against civil liberties in many parts of the world in recent years. Legitimate demands for assembly and protest freedoms are criminalized through practices such as harsh police actions, stigmatization, physical violence, and preventive detention, even in progressive regions like Europe [

104]. Despite this hostile landscape, the average score of AOF in TECs above 8 points may indicate that such rights to assembly and protest are more tolerated and less restricted. Environmental demonstrations and protests likely contribute to increasing environmental awareness and demonstrate a strong resistance against government inaction. Mass demands for a quality environment can exert pressure on governments and lead to the cessation of climate inaction. In this context, it is reasonable to assert that the freedom of assembly significantly reduces CO

2 in TECs.

The influence of civil society organizations can also explain AOF’s negative impact on CO

2. Environmental organizations are crucial catalysts in disseminating and adopting global environmental norms and standards within society. As emphasized by [

39,

105], such environmental civil society organizations can make significant contributions to setting the agenda on environmental hazards and creating environmental awareness. Moreover, these organizations are essential in negotiating with governments and companies with adverse environmental impacts to ensure compliance with environmental standards [

38]. For example, ref. [

40] presented evidence that by spreading environmental norms to large audiences, civil society organizations can reduce human-induced greenhouse gas emissions. Similarly, ref. [

41] indicated that increased civil society organizations correlate with decreased environmental conflicts and a more comfortable establishment of environmental justice. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that more organizations and members correspond to lower CO

2. Ref. [

106] further suggested that civil society can play a political role by developing environmental knowledge, mobilizing public support and media coverage, and initiating innovative sustainable practices. Presumably, in TECs, the environmental activities of civil society contribute to the preservation of environmental standards by increasing environmental awareness and preventing the relaxation of environmental policies.

In TECs, the lack of restrictions on trade unions and professional organizations could play a role in facilitating the negative relationship between AOF and CO

2. Trade unions and professional organizations aim to increase societal/social benefits rather than individual interests, fostering a collective consciousness within society. Collective action can provide democratic solutions to various issues, including environmental matters. Evaluated in terms of environmental quality, professional organizations can be influential in making environmental decisions and designing policies. Their expertise can be valuable in a broad range of areas, from developing environmental technologies to waste management, contributing to enhancing environmental quality. Indeed, the efficient functioning of trade unions and professional organizations and their ability to increase societal benefits depend on not being under undue pressure from the government and business sectors. Institutions function well in many of the 20 countries we examined, and democratic channels are operational. As highlighted by [

22], in societies where democratic institutions are developed, professional organizations and trade unions can become part of the decision-making processes, leveraging their expertise. Additionally, as [

43] emphasized, merit-based professional organizations actively involved in environmental decision-making can contribute to functional and environmentally positive decisions, thereby enhancing environmental quality.

Lastly, the reputation effect can function as a channel through which AOF contributes to reducing CO

2. For instance, ref. [

81] suggested that press freedom can create a significant reputation, motivating international investments in clean energy and green innovation. In essence, the restriction of AOF may signal a departure from democracy. This may also signify a detachment from the modern world and global issues. Sustaining AOF at a certain standard in the TEC panel can tell the world that democracy is in place. Consequently, these countries may attract environmentally friendly investments. Additionally, these countries can commit to reducing CO

2 by becoming parties to international agreements. Specifically, AOF, in general, could be one of the potential factors suppressing CO

2 in TECs due to the reputation created by the overall development of democracy and international cooperation/coordination.

The democratic principles that constitute AOF, such as freedom of assembly, organization, expression, and thought, enable the free discussion of every issue, including environmental problems. Moreover, this open and multifaceted discussion environment, reaching every layer of society, can facilitate the resolution of problems. From this perspective, the results related to AOF are promising in many aspects. The negative link between AOF and CO2 indicates no trade-off between these factors. In other words, there is no need to sacrifice the environment to expand freedoms. This situation provides policymakers in TECs with a tremendous win–win ticket. Thus, countries can achieve political, social, and environmental gains through reforms that enhance democracy.

Additionally, this finding can be fascinating globally. The relationship explicitly identified in TECs would also work in other countries. With global cooperation and coordination, countries can establish democratic processes and environmental quality. These findings are aligned with the idea of sustainable communities that emphasize collective responsibility—a ‘we’ approach—as a pathway to long-term environmental and social outcomes. Furthermore, this study contributes to a human-centered understanding of sustainability, in line with the concept of ‘pragmatic sustainability,’ where realistic, inclusive, and adaptive strategies are prioritized.

While the result for AOF in TECs is promising, the impact of economic factors on CO

2 could be much better. According to both estimators, the effect of GDP per capita, which represents economic growth, on CO

2 is positive and significant. Moreover, its coefficient is the second factor in terms of size. The reason why this positive relationship is disappointing is that economic growth is not based on green and renewable resources enough. From this perspective, insufficient renewable resources and traditional production methods inevitably create environmental costs in TECs. For example, when looking at WDI data, it can be seen that these 20 countries produce a large portion of the world’s GDP. In these countries, which produce more than half of the world’s GDP, it is evident that economic processes depend heavily on substantial natural resources and energy. In particular, the fact that growth relies heavily on non-renewable fossil-based resources shows that economic gains are achieved despite environmental costs. For instance, prominent political economists like Milanovic [

107] underscore that compromising on growth, especially for developing countries, can negatively affect employment, income distribution, and societal welfare. Even if policymakers and the public have environmental concerns, they may not want to lose the benefits of growth. Consequently, nations need to introduce reforms to shift toward a zero-carbon economy. Unless these reforms are fully implemented, it will not be surprising that economic activities in the TECs and the rest of the world will pressure the environment.

AMG and CCEMG findings indicate that the most significant pressure on CO

2 in the TEC panel comes from PEC. In terms of the magnitude of the coefficient, PEC is the most significant determinant of CO

2. This finding suggests that the examined countries’ energy portfolios rely heavily on fossil fuels, which have adverse environmental effects. As mentioned, with highly substantial economic activities, TECs require much energy. The fact that this requirement is primarily based on fossil fuels such as oil, coal, and natural gas contributes to increased CO

2. From this perspective, this strong positive relationship is entirely plausible. According to [

82], these 20 countries account for a significant portion of the world’s total energy demand. Although the share of renewable energy in the energy portfolio has increased in recent years, more is needed to reduce the environmental pressures caused by energy consumption. Within this framework, the considerable increase in CO

2 in TECs can largely be explained by the region’s heavy dependence on fossil-based, non-renewable energy sources.

Finally, the findings suggest that trade openness positively affects CO

2, but the relationship is insignificant. Refs. [

62,

108] indicate that the impact of TRD on the environment will be established through scale, composition, and technical effects. While the first effect positively impacts CO

2, the latter two reduce the pressure. In this context, the coefficient sign in the TEC panel indicates that the scale effect outweighs the composition and technical effects. The reason for this is that, although the TEC panel includes technologically advanced countries like the G7, the presence of Asian countries such as China, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam, which are the world’s production hubs, seems to increase the scale effect. While the sign of the coefficient supports these predictions, the absence of statistical significance complicates the ability to engage in a meaningful practical discussion and analysis. Moreover, the lack of statistical significance could suggest that the “pollution haven” hypothesis is not strongly evident in the sampled countries. These interpretations point to the complexity of the trade–environment nexus and suggest that the effect of TRD on emissions may vary across countries depending on their regulatory frameworks and industrial structures.

7. Conclusions

This work primarily investigates the causes of high CO2 in TECs from 2006 to 2022. In this context, political and economic factors are highlighted. AOF is chosen as the leading independent variable of this study to uncover an undiscovered driver of CO2 and design new dimensions of environmental policies. GDP, PEC, and TRD are added to the model as fundamental economic factors.

This study’s key and novel outcome is the noticeable negative connection between AOF and CO2. In other words, policymakers in TECs can reduce CO2 by enhancing AOF. This finding is crucial in demonstrating that SDGs cannot be achieved independently. Additionally, the results show that GDP and PEC exert the most significant pressure on CO2 in these countries. Finally, it was observed that TRD increases CO2 through the scale effect, but the relationship lacks statistical significance.

7.1. Policy Implications

The outcomes provide essential guidance for policymakers in TECs in shaping environmental policies. In light of this study’s main result, it is essential that fundamental freedoms, such as assembly, protest, organization, and expression, are protected and that governments adopt a transparent and tolerant stance toward criticism. Restrictive measures should be avoided, as public demonstrations can serve as a constructive feedback mechanism, enabling governments to review and improve their policies. Likewise, the activities and memberships of NGOs, unions, and professional associations should not be restricted; instead, cooperation between these groups and governments can yield positive outcomes. Protests over environmental issues should be seen as a last resort. Policymakers are encouraged to include environmental organizations, activists, and experts in decision-making processes, particularly on matters related to public welfare. Broadening participation and grounding policy design in democratic dialogue can help reduce environmental degradation and tackle broader societal challenges. In particular, major emerging market economies such as Turkey, China, Russia, India, and Mexico should strengthen democratic channels, pay greater attention to public environmental demands, and ensure the active involvement of civil society in environmental decision-making.

While the estimated coefficient appears small in magnitude, even marginal improvements in AOF can yield meaningful gains when considered cumulatively and over the long term. For instance, incremental reforms, such as removing legal restrictions on peaceful assembly or enhancing transparency in civic oversight, can incrementally raise AOF scores and contribute to environmental improvement. Although the impact may not rival that of carbon pricing in the short run, its complementary nature suggests that democratic freedoms and institutional openness should be viewed as essential components of a broader climate governance strategy.

Finally, these countries should revise and align their growth and energy policies with an environmental perspective to reduce their high emission levels effectively. In this regard, policymakers should prioritize planning sustainability transition policies across all sectors, with the participation of all stakeholders, focusing mainly on those with high environmental pressure. The implementation of a transition program should be ensured. Specifically, green and renewable energy sectors should be developed, utilizing methods such as credit facilities, incentives, tax exemptions, and penalties. The negative influence of PEC on emissions underscores the critical importance of adopting and promoting renewable energy. Therefore, policymakers should place specific emphasis on energy transformation.

7.2. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

While this study contributes to the literature, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations. For instance, the analysis period is constrained to 2006–2022, as AOF data is available only until 2006, and a broader timeframe has yet to be explored. Moreover, there is no alternative dataset that covers AOF as comprehensively as Freedom House. Additionally, this study emphasizes a single political variable, neglecting various other political factors. Future research could enhance the literature by extending the analysis period by generating new data and focusing on different political factors. Moreover, future studies might explore AOF’s impact on new countries or country groups. Another potential avenue for future research is addressing possible reverse causality between AOF and CO2, for instance, by employing instrumental variables or Granger causality tests. Exploring bidirectional relationships would help clarify the dynamic interplay between environmental degradation and political freedoms. All these endeavors would provide valuable insights into the political origins of environmental degradation.

One potential limitation of this study lies in its macro-level approach to assessing the impact of AOF on environmental quality. While the analysis offers valuable insights into the broader institutional context in which civil society operates, it does not capture the direct and specific environmental actions of individual organizations or actors. Based on the conceptualization of AOF, this study identifies four potential channels through which AOF may influence environmental outcomes. However, it is acknowledged that this framework remains general in scope and does not differentiate among the varied goals or societal perceptions of civil society initiatives.

Future research could build upon this foundation by employing more granular, country-level data—particularly through survey-based or qualitative methods—to assess the direct and specific environmental implications of AOF. Such approaches would enable a deeper investigation into how pro-environmental organizations operate, how frequently they mobilize, and how they are perceived by society, thereby offering a more micro-level perspective.

Finally, although the control variables used in this study were selected based on the existing literature, it is worth noting that numerous factors influence CO2. It is practically impossible to examine all potential determinants within a single model. In this context, variables such as the share of renewable energy, urbanization, institutional quality, and energy intensity can be included as control variables in future research. Such efforts would enhance the understanding of the determinants of CO2 in the literature.