Harnessing Knowledge: The Robust Role of Knowledge Management Practices and Business Intelligence Systems in Developing Entrepreneurial Leadership and Organizational Sustainability in SMEs

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1. How do knowledge management practices (KAG, KDM, and KRN) affect BISMs and OS in Saudi Arabia’s SMEs?

- RQ2. How do BISMs affect OS and ELP in Saudi Arabia’s SMEs?

- RQ3. How does ELP mediate the link between BISMs and OS in Saudi Arabia’s SMEs?

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Underpinning

2.1. Knowledge Management Practices

2.2. Business Intelligence System (BISM)

2.3. Entrepreneurial Leadership (ELP)

2.4. Organizational Sustainability (OS)

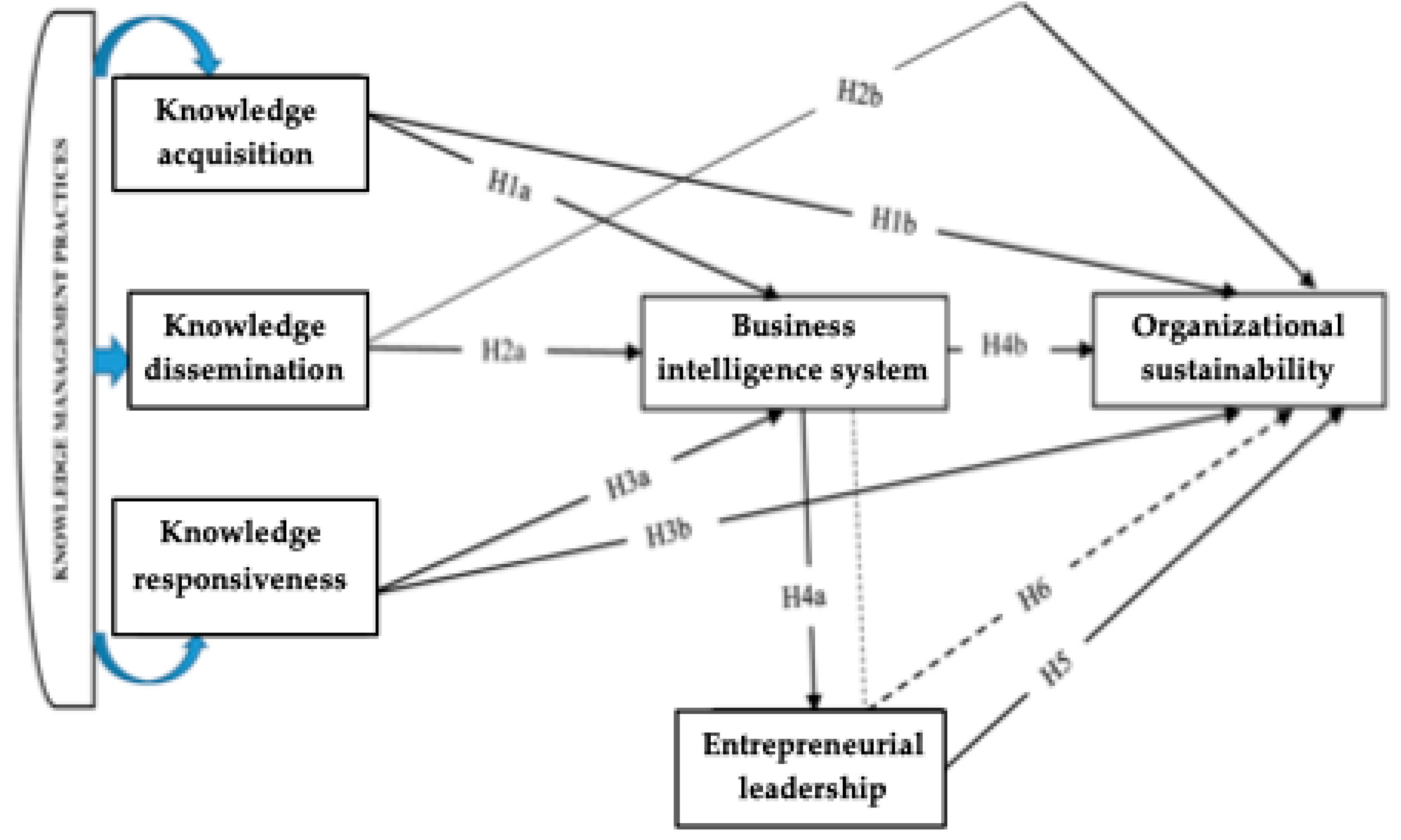

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Knowledge Acquisition (KAG), Business Intelligence Systems (BISMs), and Organizational Sustainability (OS)

3.2. Knowledge Dissemination (KDM), Business Intelligence Systems (BISMs), and Organizational Sustainability (OS)

3.3. Knowledge Responsiveness (KRN), Business Intelligence Systems (BISMs), and Organizational Sustainability (OS)

3.4. Business Intelligence Systems (BISMs), Entrepreneurial Leadership (ELP), and Organizational Sustainability (OS)

3.5. Entrepreneurial Leadership (ELP) and Organizational Sustainability (OS)

3.6. Entrepreneurial Leadership (ELP) as a Mediator

4. Research Methods

4.1. Design and Sample

4.2. Method Bias Test

4.3. Data Collection Procedure

4.4. Measurement Scales

5. Analysis

5.1. Respondents’ Profile

5.2. Measurement Model

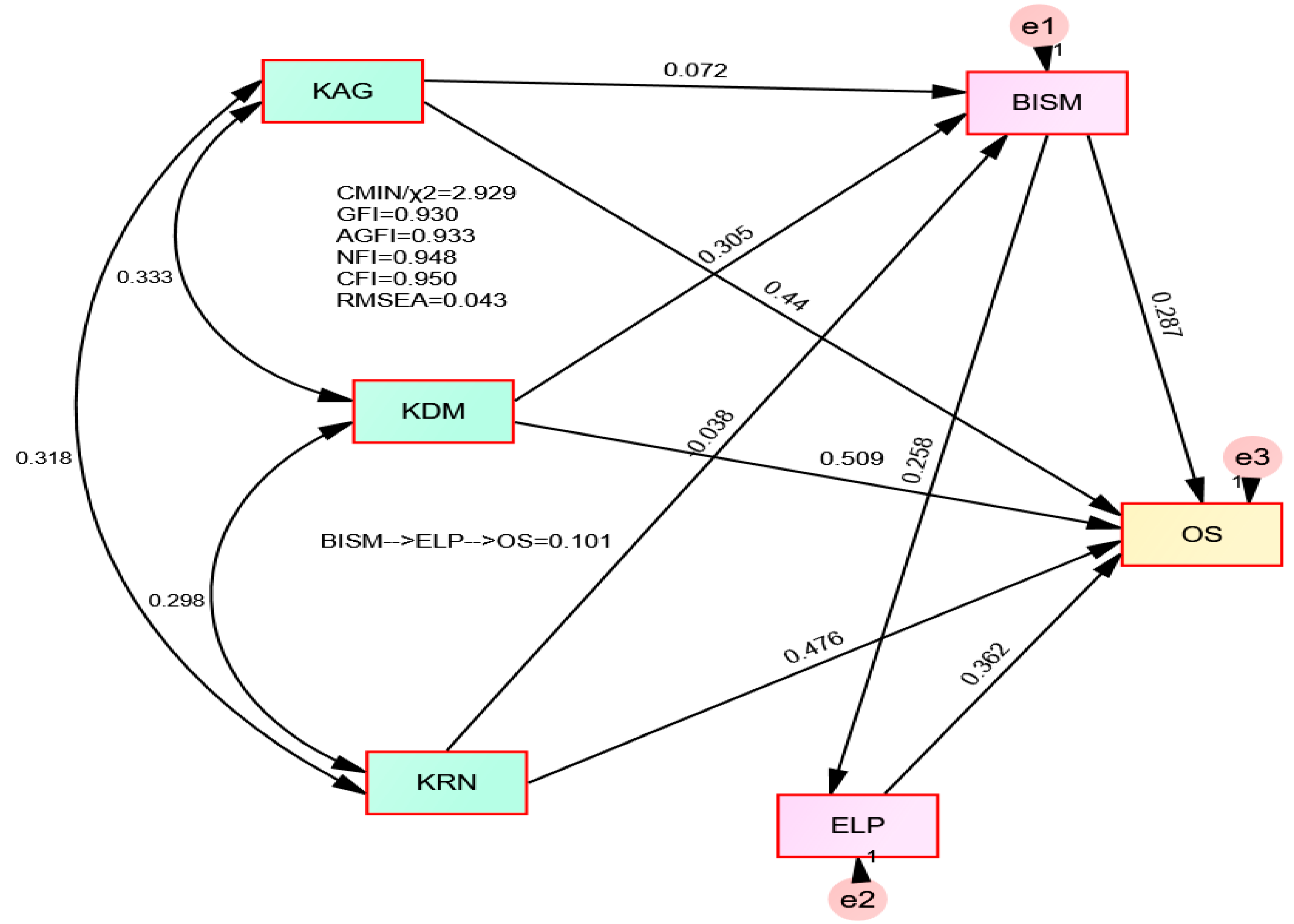

5.3. Structural Model

6. Discussion and Conclusions

7. Implications of the Research

7.1. Practical Implications

7.2. Theoretical Implications

8. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alsqour, M.D.; Owoc, M.L. Benefits of knowledge acquisition systems for management. An empirical study. In Proceedings of the 2015 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems (FedCSIS), Lodz, Poland, 13–16 September 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1691–1698. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Vogel, D.; Yang, T.; Deng, J. The effect of social media-enabled mentoring on online tacit knowledge acquisition within sustainable organizations: A moderated mediation model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.J.; Tuma, F.; Veiga, P.M.; Vrontis, D. The interplay of corporate entrepreneurship, knowledge acquisition, knowledge-based resources and SME performance. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2025, 55, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Koliby, I.S.; Mohd Suki, N.; Abdullah, H.H. Linking knowledge acquisition, knowledge dissemination, and manufacturing SMEs’ sustainable performance: The mediating role of knowledge application. Bottom Line 2022, 35, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.; Farooq, R.; Naqshbandi, M.M. The impact of business model innovation and knowledge management on firm performance: An emerging markets perspective. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2024, 30, 2401–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero, A. Optimizing green knowledge acquisition through entrepreneurial orientation and resource orchestration for sustainable business performance. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2025, 43, 241–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuemeke, H.E.; Igbinedion, V.I. Relationship between knowledge dissemination, learning self-efficacy and task performance of business educators. NAU J. Technol. Vocat. Educ. 2021, 6, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Darroch, J. Developing a measure of knowledge management behaviors and practices. J. Knowl. Manag. 2003, 7, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renko, M.; El Tarabishy, A.; Carsrud, A.L.; Brännback, M. Understanding and measuring entrepreneurial leadership style. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, A. The Digitalization Impact on the Entrepreneurial Leadership in the 21st Century. Int. J. Soc. Relev. Concern 2021, 9, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, G.; Luu, T.T.; Babalola, M.T. Entrepreneurial leadership: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2025, 46, 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoun-Chouk, S.; Berger, H.; Sie, B.H. Towards integrated model of big data (BD), business intelligence (BI) and knowledge management (KM). In Knowledge Management in Organizations, Proceedings of the 12th International Conference, KMO 2017, Beijing, China, 21–24 August 2017; Proceedings 12; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 482–493. [Google Scholar]

- Olszak, C.M. Business intelligence systems for innovative development of organizations. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 207, 1754–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ding, S. BI in simulation analysis with gaming for decision making and development of knowledge management. Entertain. Comput. 2025, 52, 100811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.; Liu, J.; Ali, E. Incorporating sustainability in organizational strategy: A framework for enhancing sustainable knowledge management and green innovation. Kybernetes 2025, 54, 2363–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, N.M. The influence of entrepreneurial leadership and sustainability leadership on high-performing school leaders: Mediated by empowerment. Leadersh. Educ. Personal. Interdiscip. J. 2021, 3, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S. Effects of key leadership determinants on business sustainability in entrepreneurial enterprises. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2023, 15, 885–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hawamdeh, N.; Al-Edenat, M. Entrepreneurial leadership and organisational sustainability: The role of knowledge management. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2025, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Entrepreneurship and sustainable leadership practices: Examine how entrepreneurial leaders incorporate sustainability into their business models and the leadership traits facilitating this integration. J. Entrep. Bus. Ventur. 2025, 5, 242–260. [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun, A.; Fazal, S.A.; Muniady, R. Entrepreneurial leadership, performance, and sustainability of micro-enterprises in Malaysia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Elrehail, H.; Alatailat, M.A.; Elçi, A. Knowledge management, decision-making style and organizational performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P. Knowledge acquisition and development in sustainability-oriented small and medium-sized enterprises: Exploring the practices, capabilities and cooperation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3769–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebus, S.; Leiviskä, K. Knowledge acquisition for decision support systems on an electronic assembly line. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziembek, D.; Ziora, L. Business intelligence systems in the SaaS model as a tool supporting knowledge acquisition in the virtual organization. Online J. Appl. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 2, 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Li, F.; Yoo, J.W.; Kim, C.Y. The relationships among environments, external knowledge acquisition, and innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, B.M.; Brownson, R.C.; Glasgow, R.E.; Morrato, E.H.; Luke, D.A. Designing for dissemination and sustainability to promote equitable impacts on health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardjono, W.; Pujadi, T.; Sukardi, S.; Rahmasari, A.; Selviyanti, E. Dissemination of sustainable development goals through knowledge management systems utilization. ICIC Express Lett. 2021, 15, 877–886. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Clarke, A.; Heldsinger, N.; Tian, W. The communication role of social media in social marketing: A study of the community sustainability knowledge dissemination on LinkedIn and Twitter. J. Mark. Anal. 2019, 7, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan, P.; Ebrahim Sanjaghi, M.; Rezaeenour, J.; Ojaghi, H. Examining the relationships between organizational culture, knowledge management and environmental responsiveness capability. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2014, 44, 228–248. [Google Scholar]

- Lakeh, E.S.; Khorakian, A.; Bajestani, M.F. Knowledge absorptive capacity and organizational responsiveness: The moderating role of strategic orientation. J. Manag. Res. 2023, 23, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sherringham, K.; Unhelkar, B.; Sherringham, K.; Unhelkar, B. Adaptiveness and responsiveness within knowledge worker services. In Crafting and Shaping Knowledge Worker Services in the Information Economy; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2020; pp. 87–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, H.; Lehrer, M.; Mühlbacher, J.; Müller, B. Integration-responsiveness and knowledge-management perspectives on the MNC: A typology and field study of cross-site knowledge-sharing practices. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2009, 15, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbashir, M.Z.; Collier, P.A.; Davern, M.J. Measuring the effects of business intelligence systems: The relationship between business process and organizational performance. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2008, 9, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, M.S.; Hoque, M.R.; Bao, Y. The impact of business intelligence on organization’s effectiveness: An empirical study. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2015, 17, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, A.S.H.; Al-Mado, A.A.G. Knowledge Management in Integration with Business Intelligence Systems: A Descriptive Analytical Research1. Int. J. Res. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2023, 13, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, R.; Wareham, J. Analysing the impact of a business intelligence system and new conceptualizations of system use. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2019, 24, 245–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunowski, R. Sustainability of commercial banks supported by business intelligence system. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, M.; Isaai, M.T.; Arasti, M.R.; Mehralian, G. A framework for developing business intelligence systems: A knowledge perspective. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 41, 1358–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapp, C.E.; Mazzuchi, T.; Sarkani, S. Rationalising business intelligence systems and explicit knowledge objects: Improving evidence-based management in government programs. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 13, 1450018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masa’Deh, R.E.; Obeidat, Z.; Maqableh, M.; Shah, M. The impact of business intelligence systems on an organization’s effectiveness: The role of metadata quality from a developing country’s view. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2021, 22, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G.P. Developing dynamic organizational theories using system dynamics methods. Qual. Quant. 2020, 54, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pejic Bach, M.; Zoroja, J.; Krstic, K. System dynamics modeling for sustainable urban development: A review. Kybernetes 2019, 48, 945–967. [Google Scholar]

- Oladimeji, E.A.; Cross, J.; Keathley-Herring, H. A review of system dynamics applications in performance measurement and management. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2020, 70, 2143–2171. [Google Scholar]

- Naumann, R.B.; Hampton, K.H.; Butts, J.; Jenkins, P.; Talbert, M.; Andridge, R. System dynamics applications to injury and violence prevention: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, e93–e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyneis, J.M.; Ford, D.N. System dynamics applied to project management: A survey, assessment, and directions for future research. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2007, 23, 157–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, I.; Hartani, N.H.; Sroka, M. Operational performance of SME: The impact of entrepreneurial leadership, good governance and business process management. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 21, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwi Widyani, A.A.; Landra, N.; Sudja, N.; Ximenes, M.; Sarmawa, I.W.G. The role of ethical behavior and entrepreneurial leadership to improve organizational performance. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1747827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Tee, D.D.; Ahmed, P.K. Entrepreneurial leadership and context in Chinese firms: A tale of two Chinese private enterprises. In Leadership in the Asia Pacific; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Janabi, A.S.H.; Hussein, S.A.; Mhaibes, H.A.; Flayyih, H.H. The role of entrepreneurial leadership strategy in promoting organizational sustainability: A descriptive and analytical study. Corp. Bus. Strategy Rev. 2024, 5, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal Badri, S.K.; Ngo, M.S.M. Is job crafting beneficial for millennial employees? A moderated mediation model of affective organizational commitment, turnover intention and entrepreneurial leadership. J. Manag. Dev. 2024, 43, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, H.; Safaeimanesh, F.; Soosan, A. Investigating sustainable practices in hotel industry-from employees’ perspective: Evidence from a Mediterranean Island. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavalić, M.; Nikolić, M.; Radosav, D.; Stanisavljev, S.; Pečujlija, M. Influencing factors on knowledge management for organizational sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, F.; Mohammad, J.; Awang, S.R.; Ahmad, T. The effect of knowledge sharing and systems thinking on organizational sustainability: The mediating role of creativity. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 1251–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Khattak, A.; Rabbani, S.; Dhir, A. Buyer-driven knowledge transfer activities to enhance organizational sustainability of suppliers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frozza, T.; de Lima, E.P.; da Costa, S.E.G. Knowledge management and blockchain technology for organizational sustainability: Conceptual Model. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2023, 20, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, L.C.; Goyal, S.B.; Bedi, P.; Nimbalkar, V. The role of business intelligence in organizational sustainability in the era of IR 4.0. In Business Intelligence and Human Resource Management; Productivity Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmawa, I.W.G.; Widyani, A.A.D.; Sugianingrat, I.A.P.W.; Martini, I.A.O. Ethical entrepreneurial leadership and organizational trust for organizational sustainability. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1818368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaoula, W.; Belgoum, F.; Shaikh, A.; Taleb-Berrouane, M.; Bazan, C. The impact of business intelligence through knowledge management. Bus. Inf. Rev. 2019, 36, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosen, M.S.; Islam, R.; Naeem, Z.; Folorunso, E.O.; Chu, T.S.; Al Mamun, M.A.; Orunbon, N.O. Data-driven decision making: Advanced database systems for business intelligence. Nanotechnol. Percept. 2024, 20, 687–704. [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz, J.; Aramburu, N.; Alcalde-Heras, H.; Buenechea-Elberdin, M. Technical knowledge acquisition modes and environmental sustainability in Spanish organic farms. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 109, 103338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xu, X.Y. Unlocking the secrets of business intelligence and analytics in driving brand innovation: Insights from an empirical study using SEM and fsQCA. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2494066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; MacMillan, I.C.; Surie, G. Entrepreneurial leadership: Developing and measuring a cross-cultural construct. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- McGovern, J.; Samson, D.; Wirth, A. Knowledge acquisition for intelligent decision systems. Decis. Support Syst. 1991, 7, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beveren, J. A model of knowledge acquisition that refocuses knowledge management. J. Knowl. Manag. 2002, 6, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbim, K.C.; Zever, T.A.; Oriarewo, G.O. Assessing the effect of knowledge acquisition on competitive advantage: A knowledge-based and resource-based study. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 4, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Wadood, S.A.; Chatha, K.A.; Jajja, M.S.S.; Pagell, M. Social network governance and social sustainability-related knowledge acquisition: The contingent role of network structure. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2022, 42, 745–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, A. How do green knowledge management and green technology innovation impact corporate environmental performance? Understanding the role of green knowledge acquisition. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polas, M.R.H.; Tabash, M.I.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Dávila, G.A. Knowledge management practices and green innovation in SMES: The role of environmental awareness towards environmental sustainability. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2023, 31, 1601–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surbakti, H. Integrating knowledge management and business intelligence processes for empowering government business organizations. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 114, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidizadeh, R.; Salehzadeh, R.; Chitsaz Esfahani, A. Analysing the role of business intelligence, knowledge sharing and organisational innovation on gaining competitive advantage. J. Workplace Learn. 2017, 29, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsarayreh, R.; Buraik, O. The Impact of Business Intelligence on Strategic Ambidexterity: The Mediating Role of Knowledge Sharing. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2025, 23, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A.; Quadri, S.K. Dovetailing of business intelligence and knowledge management: An integrative framework. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2012, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, A.C.; WAllen, M. Sustainability information sources: Employee knowledge, perceptions, and learning. J. Commun. Manag. 2013, 17, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordab, M.; Raudeliūnienė, J.; Meidutė-Kavaliauskienė, I. Mediating role of knowledge management in the relationship between organizational learning and sustainable organizational performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus-Rosińska, A.; Walecka-Jankowska, K.; Zgrzywa-Ziemak, A. The significance of knowledge management processes for business sustianability: The role of sustainability-oriented projects. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 31, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaldeh, K.; Alzghoul, A. Nexus of business intelligence capabilities, firm performance, firm agility, and knowledge-oriented leadership in the Jordanian high-tech sector. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2024, 22, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Liao, Y. Information sharing, operations capabilities, market intelligence responsiveness and firm performance: A moderated mediation model. Balt. J. Manag. 2019, 14, 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Hameed, W.U.; Bhatti, M.I. Integrating business and market intelligence to expedite service responsiveness: Evidence from Malaysia. Qual. Quant. 2024, 58, 1303–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leka, B.; Leka, D.; Baraku, B. Driving Operational Excellence: Business Intelligence in the Car Parts Industry. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2025, 22, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lo, C.W.H.; Li, P.H.Y. Organizational visibility, stakeholder environmental pressure and corporate environmental responsiveness in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Lee, E.S.; Lee, T. Dynamic knowledge management and supply chain integration: Driving innovation and resilience in Korean shipping SMEs. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2025, 31, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiula, M.; Waiganjo, E.; Kihoro, J. The role of leadership in building the foundations for data analytics, visualization and business intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2019 IST-Africa Week Conference (IST-Africa), Nairobi, Kenya, 8–10 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wee, M.; Scheepers, H.; Tian, X. The role of leadership skills in the adoption of business intelligence and analytics by SMEs. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 36, 1439–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhi, R.; Enayati, T.; Taghvaee Yazdi, M. Explaining the differentiation strategy by entrepreneurial leadership and competitive intelligence for the home appliance industry. J. Strateg. Manag. Stud. 2023, 14, 291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Chornous, G.O.; Gura, V.L. Integration of information systems for predictive workforce analytics: Models, synergy, security of entrepreneurship. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, M.; Pozzebon, M. Managing sustainability with the support of business intelligence: Integrating socio-environmental indicators and organisational context. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2009, 18, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmeta, R.; Ferrer Estevez, M. Developing a business intelligence tool for sustainability management. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2023, 29, 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, M. Business intelligence issues for sustainability projects. Sustainability 2018, 10, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, B.; Calitz, A.; Haupt, R. A business intelligence framework for sustainability information management in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 266–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, N.A.; Khan, P.A.; Shad, M.K. Digitalization, Sustainability and Development in Business. Business Intelligence-The Innovative Solutions for Business Sustainability, Equality, and Green Initiatives of Long-Term Organisational Performance. KnE Soc. Sci. 2023, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calitz, A.; Bosire, S.; Cullen, M. The role of business intelligence in sustainability reporting for South African higher education institutions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 1185–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim Guermazi, H.; Nazzal, M.E. The impact of business intelligence on environmental sustainable development goals (ESDGs): An applied study in the Iraqi cement company. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2025, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, G.; Silviu, N. Managing Sustainability with Eco-Business Intelligence Instruments. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 6, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, R.; Scholtz, B.; Calitz, A. Using business intelligence to support strategic sustainability information management. In Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Research Conference on South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 28–30 September 2015; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jan, B.K.; Maulida, M. The role of leaders’ motivation, entrepreneurial leadership, and organisational agility in social enterprise sustainability. South East Asian J. Manag. 2022, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, N.M.; Zakaria, M.N. The significance of entrepreneurial leadership and sustainability leadership (leadership 4.0) towards Malaysian school performance. Int. J. Entrep. 2019, 2, 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, R.; Aldaas, R.E. Entrepreneurial leadership: A missing link between perceived organizational support and organizational performance. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 16, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, M.; Slavković, M.; Aleksić, V.S. Human capital and SME performance: Mediating effect of entrepreneurial leadership. Manag. J. Sustain. Bus. Manag. Solut. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 25, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Daryani, M.A.; Rahmani, S. The influence of entrepreneurial orientation on firm growth among Iranian agricultural SMEs: The mediation role of entrepreneurial leadership and market orientation. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2021, 11, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Herman, H.M.; Schwarz, G.; Nielsen, I. The effects of employees’ creative self-efficacy on innovative behavior: The role of entrepreneurial leadership. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, C.B.A.; Ahmed, R. Organizational culture and entrepreneurial orientation: Mediating role of entrepreneurial leadership. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2019, 11, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alshehri, M.; Bamasak, O. Business intelligence adoption in Saudi SMEs: Drivers and challenges. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2022, 35, 987–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Alshahrani, S.; Al-Karaghouli, W.; Al-Balushi, Y. Knowledge management capabilities and innovation performance in Saudi SMEs: The mediating role of digital transformation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 333–352. [Google Scholar]

- Alarifi, G.; Robson, P.; Kromidha, E. The role of entrepreneurs’ social capital in the performance of Saudi SMEs. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2020, 27, 349–367. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. Annu. Rev. 2011, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Williams, L.J.; Huang, C.; Yang, J. Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2024, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, G.A.; Brooks, G.P. Initial scale development: Sample size for pilot studies. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2010, 70, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijtsma, K. On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika 2009, 74, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeish, D. Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychol. Methods 2018, 23, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.G.; Taylor, A.B.; Wu, W. Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. Handb. Struct. Equ. Model. 2012, 1, 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Tousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Breaugh, J.A. Employee recruitment: Current knowledge and important areas for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2008, 18, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. Does my structural model represent the real phenomenon?: A review of the appropriate use of structural equation modelling (SEM) model fit indices. Mark. Rev. 2009, 9, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abusweilem, M.; Abualoush, S. The impact of knowledge management process and business intelligence on organizational performance. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 2143–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | No. of Items | CR | AVE | CFI | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Organizational sustainability [OS] | 20 | 0.718 | 0.529 | 0.912 | 0.899 | 0.903 | 0.0309 |

| 2.Business intelligence system [BISM] | 10 | 0.760 | 0.590 | ||||

| 3.Entrepreneurial leadership [ELP] | 8 | 0.899 | 0.612 | ||||

| 4.Knowledge acquisition [KAG] | 6 | 0.787 | 0.658 | ||||

| 5.Knowledge dissemination [KDM] | 5 | 0.803 | 0.692 | ||||

| 6.Knowledge responsiveness [KRN] | 5 | 0.772 | 0.571 |

| Construct | Definition | Items Details | Scale [Five-Point Likert Scale] | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge acquisition [KAG] | --- gathering and integrating valuable information from employees, market changes, financial systems, technology expertise, international partnerships, and market surveys. | kag1: Organizational values, employees’ attitudes, and opinion. | strongly disagree = 1; strongly agree = 5 | [8] |

| kag2: The organization has well-developed financial reporting systems. | = | |||

| kag3: The organization is sensitive to information about changes in the market place. | = | |||

| kag4: Science and technology human capital profile. | = | |||

| kag5: The organization works in partnership with international customers. | = | |||

| kag6: The organization obtains information from market surveys. | = | |||

| Knowledge dissemination [KDM] | --- effective information sharing within an organization through different sources, i.e., technology and written communication. | kdm1: Market information is freely disseminated. | strongly disagree = 1; strongly agree = 5 | [8] |

| kdm2: Knowledge is disseminated on-the-job. | = | |||

| kdm3: Use of specific techniques to disseminate knowledge. | = | |||

| kdm4: The organization uses technology to disseminate knowledge. | = | |||

| kdm5: The organization prefers written communication. | = | |||

| Knowledge responsiveness [KRN] | --- the organization’s ability to adapt and act on customer needs, market trends, technological changes, competitor actions, and emerging opportunities. | krn1: We respond to customers. | strongly disagree = 1; strongly agree = 5 | [8] |

| krn2: We have well-developed marketing functions. | = | |||

| krn3: We respond to technology. | = | |||

| krn4: We respond to competitors. | = | |||

| krn5: Our organization is flexible and opportunistic. | = | |||

| Business intelligence system [BISM] | --- enhances coordination, reduces costs, improves responsiveness, streamlines processes, boosts productivity, and supports efficient decision making, ultimately optimizing operations and market performance. | bism1: BISM improved the coordination with business partners/suppliers. | strongly disagree = 1; strongly agree = 5 | [33] |

| bism2: BISM reduced the cost of transactions with business partners/suppliers. | = | |||

| bism3: BISM improved the responsiveness to/from suppliers. | = | |||

| bism4: BISM intelligence improved the efficiency of internal processes. | = | |||

| bism5: BISM increased staff productivity. | = | |||

| bism6: BISM reduced the cost of effective decision making. | = | |||

| bism7: BISM reduced operational costs. | = | |||

| bism8: BISM reduced customer return handling costs. | = | |||

| bism9: BISM reduced marketing costs. | = | |||

| bism10: BISM reduced time-to-market products/services. | = | |||

| Entrepreneurial leadership [ELP] | --- a leadership style characterized by visionary thinking, innovation, risk taking, and a strong passion for driving change, where leaders inspire and challenge others to pursue creative solutions, develop new products, and rethink traditional business practices. | The leader of this company… elp1: often comes up with radically improved ideas for the products that we are selling | strongly disagree = 1; strongly agree = 5 | [9] |

| elp2: often comes up with ideas of completely new products that we could sell. | = | |||

| elp3: takes risks. | = | |||

| elp4: has creative solutions to problems. | = | |||

| elp5: demonstrates passion for his/her work. | = | |||

| elp6: has a vision for the future of our business | = | |||

| elp7: challenges and pushes us to act in a more innovative way. | = | |||

| elp8: wants us to challenge the current ways that we do business | = | |||

| Organizational sustainability [OS] | --- the ability of an organization to operate in a manner that ensures long-term viability by balancing and integrating economic efficiency, environmental responsibility, and social equity in its strategies, operations, and stakeholder relationships. | osso1: The sustainability management system (SMS) is clearly documented and understood. | strongly disagree = 1; strongly agree = 5 | [51] |

| osso2: Staff are informed and trained about the natural and cultural heritage of the local area. | = | |||

| osso3: The organization participates in partnerships between local communities, NGOs, and other local bodies where these exist. | = | |||

| osso4: The organization has identified groups at risk of discrimination, including women and local minorities. | = | |||

| osso5: The organization seeks to bring innovative green products and services to the market. | = | |||

| osso6: The organization often uses eco-labels on packaging and shows them on their corporate websites. | = | |||

| en1: Records of these programmes are listed and managed. | = | |||

| en2: There is an environmental awareness-raising plan. | = | |||

| en3: Native and endemic plants obtained from sustainable sources have been used in landscaping and decoration, avoiding exotic and invasive species. | = | |||

| en4: The organization uses green procurement criteria. | = | |||

| en5: The organization holds environmental protection awareness programmes for the community. | = | |||

| en6: The total direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions are monitored and managed. | = | |||

| en7: Chemicals, especially those in bulk amounts, are stored and handled in accordance with appropriate standards. | = | |||

| en8: The organization is aware of, and complies with, relevant laws and regulations concerning animal welfare. | = | |||

| ec1: SMS includes a process for monitoring continuous improvement in sustainability performance | = | |||

| ec2: Energy used per tourist/night for each type of energy is monitored and managed. | = | |||

| ec3: Water saving equipment is regularly maintained and is efficient. | = | |||

| ec4: Equipment and facilities for air quality are monitored and maintained. | = | |||

| ec5: A solid waste management plan is in place. | = | |||

| ec6: The organization uses and promotes the usage of recyclable water or grey water in other operations (e.g., watering trees). | = |

| Indicator | Category | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 287(80.62) |

| Female | 69(19.38) | |

| Age (years) | 25–34 years | 114 (32.0) |

| 35–44 years | 143 (40.2) | |

| 45–54 years | 75 (21.1) | |

| 55+ years | 24 (6.7) | |

| Educational level | Diploma | 25 (7.0) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 200 (56.2) | |

| Master’s degree | 107 (30.1) | |

| Doctorate | 24 (6.7) | |

| Firm size | Micro (1–9 employees) | 64 (18.0) |

| Small (10–49 employees) | 164 (46.1) | |

| Medium (50–249 employees) | 128 (36.0) | |

| Firm age | Less than 5 years | 89 (25.0) |

| 5–10 years | 150 (42.1) | |

| More than 10 years | 117 (32.9) | |

| Industry type | Manufacturing | 78 (21.9) |

| Services | 99 (27.8) | |

| Information technology | 68 (19.1) | |

| Retail and trade | 75 (21.1) | |

| Others (e.g., logistics, construction) | 36 (10.1) | |

| Level of digitalization/BI use | No adoption | 39 (11.0) |

| Basic (limited use) | 157 (44.1) | |

| Moderate (partial integration) | 111 (31.2) | |

| Advanced (fully integrated) | 49 (13.8) |

| Construct | Item Code | Factor Loadings [>0.7] | CR [>0.7] | AVE [0.5] | Alpha Reliability (α) [>0.7] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge acquisition [KAG] | kag1 | 0.872 | 0.960 | 0.716 | 0.801 |

| kag2 | 0.858 | ||||

| kag3 | 0.846 | ||||

| kag4 | 0.833 | ||||

| kag6 | 0.821 | ||||

| Knowledge dissemination [KDM] | kdm1 | 0.845 | 0.909 | 0.667 | 0.809 |

| kdm2 | 0.831 | ||||

| kdm3 | 0.829 | ||||

| kdm4 | 0.798 | ||||

| kdm5 | 0.780 | ||||

| Knowledge responsiveness [KRN] | krn1 | 0.872 | 0.919 | 0.695 | 0.837 |

| krn2 | 0.858 | ||||

| krn3 | 0.837 | ||||

| krn4 | 0.818 | ||||

| krn5 | 0.780 | ||||

| Business intelligence system [BISM] | bism1 | 0.867 | 0.934 | 0.668 | 0.799 |

| bism2 | 0.848 | ||||

| bism3 | 0.839 | ||||

| bism4 | 0.810 | ||||

| bism6 | 0.792 | ||||

| bism7 | 0.783 | ||||

| bism9 | 0.776 | ||||

| bism10 | 0.751 | ||||

| Entrepreneurial leadership [ELP] | elp1 | 0.862 | 0.935 | 0.674 | 0.829 |

| elp2 | 0.843 | ||||

| elp4 | 0.833 | ||||

| elp5 | 0.820 | ||||

| elp6 | 0.805 | ||||

| elp7 | 0.798 | ||||

| elp8 | 0.781 | ||||

| Organizational sustainability [OS] | osso1 | 0.893 | 0.914 | 0.662 | 0.887 |

| osso2 | 0.882 | ||||

| osso3 | 0.873 | ||||

| osso4 | 0.861 | ||||

| osso6 | 0.855 | ||||

| osen1 | 0.850 | ||||

| osen2 | 0.836 | ||||

| osen3 | 0.821 | ||||

| osen5 | 0.819 | ||||

| osen7 | 0.803 | ||||

| osen8 | 0.793 | ||||

| osec1 | 0.789 | ||||

| osec2 | 0.773 | ||||

| osec3 | 0.760 | ||||

| osec4 | 0.756 | ||||

| osec6 | 0.731 |

| S. No | Factors | 1 BISM | 2 ELP | 3 OS | 4 KAG | 5 KDM | 6 KRN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BISM | 0.803 | |||||

| 2 | ELP | 0.382 | 0.775 | ||||

| 3 | OS | 0.401 | 0.431 | 0.790 | |||

| 4 | KAG | 0.387 | 0.426 | 0.333 | 0.818 | ||

| 5 | KDM | 0.318 | 0.379 | 0.404 | 0.416 | 0.789 | |

| 6 | KRN | −0.219 | 0.232 | 0.300 | 0.383 | 0.318 | 0.761 |

| Model Fitness → | CMIN/df | GFI | AGFI | NFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model fit indices → | 2.929 | 0.930 | 0.933 | 0.948 | 0.950 | 0.043 |

| Required values → | <3 or p > 0.005 | >0.90 | <0.05 | |||

| H.No. | Relationships | Estimate β (Path Co-Efficient) | SE | CR (t-Value) | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | KAG→ BISM | 0.072 | 0.023 | 3.165 | 0.002 | [√] |

| H1b | KAG→ OS | 0.440 | 0.047 | 9.407 | 0.000 | [√] |

| H2a | KDM→ BISM | 0.305 | 0.042 | 7.235 | 0.000 | [√] |

| H2b | KDM→ OS | 0.509 | 0.075 | 6.900 | 0.000 | [√] |

| H3a | KRN→ BISM | −0.038 | 0.067 | 0.570 | 0.569 | [×] |

| H3b | KRN→ OS | 0.476 | 0.125 | 3.872 | 0.000 | [√] |

| H4a | BISM→ELP | 0.258 | 0.063 | 4.042 | 0.000 | [√] |

| H4b | BISM→ OS | 0.287 | 0.032 | 9.013 | 0.000 | [√] |

| H5 | ELP→OS | 0.362 | 0.097 | 3.705 | 0.000 | [√] |

| H.No. | Relationships | Estimate β (Path Co-Efficient) | SE | CR (t-Value) | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H6 | BISM→ELP→OS | 0.101 | 0.031 | 3.225 | 0.001 | [√] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alharthi, S. Harnessing Knowledge: The Robust Role of Knowledge Management Practices and Business Intelligence Systems in Developing Entrepreneurial Leadership and Organizational Sustainability in SMEs. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6264. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146264

Alharthi S. Harnessing Knowledge: The Robust Role of Knowledge Management Practices and Business Intelligence Systems in Developing Entrepreneurial Leadership and Organizational Sustainability in SMEs. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6264. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146264

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlharthi, Sager. 2025. "Harnessing Knowledge: The Robust Role of Knowledge Management Practices and Business Intelligence Systems in Developing Entrepreneurial Leadership and Organizational Sustainability in SMEs" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6264. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146264

APA StyleAlharthi, S. (2025). Harnessing Knowledge: The Robust Role of Knowledge Management Practices and Business Intelligence Systems in Developing Entrepreneurial Leadership and Organizational Sustainability in SMEs. Sustainability, 17(14), 6264. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146264