1. Introduction

Initiatives for local and sustainable development in tourism often lack feasibility analysis from a social perspective [

1]. However, the appearance of new approaches and participation of previously ignored local actors, such as indigenous communities and other minority groups, have gained importance in the idea of development [

2]. For [

3], the conventional model of tourism has generated inequalities and negative environmental and cultural effects, mainly in less developed countries [

4]. In this sense, the overload and progressive degradation of this model has generated the appearance of alternative tourism (AT) [

1,

5] focused on sustainability, and cultural and environmental responsibility.

Some authors [

5] argue that changing consumer preferences have driven AT, but the abuse of its gradual growth can have similar or even worse negative consequences than mass tourism. Therefore, its management must fall on the area where it is implemented [

6] to move towards responsible, sustainable and accessible tourism for all [

7]. The failure of Western development models in the Global South has prompted local communities to develop alternatives aimed at profound social transformations. These alternatives rely on the creation of new knowledge, practices, technologies, and institutions, conceived as forms of innovation promoted by social movements, collectives, Indigenous peoples, and local communities to build more just and sustainable societies [

8].

Tourism governance models promoted by international organizations such as the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) have emphasized the need to establish strong institutional structures, foster multisectoral participation, and ensure coordination across different levels of government to achieve the SDGs at the local level. In the case of the UNWTO [

9], a collaborative destination governance approach has been promoted, in which public and private sectors, along with civil society, align efforts to plan, monitor, and implement sustainable tourism strategies. In turn, the UNDP [

10] has developed governance models focused on strengthening local capacities, promoting the inclusion of historically marginalized groups, and effectively decentralizing decision-making processes—recognizing tourism as a tool for human development and territorial resilience.

In clear contrast to these predominantly institutional and normative approaches, the METACORTAL model—proposed in this study—offers a bottom-up governance approach rooted in the sociocultural and ecological contexts of the communities receiving alternative tourism. By integrating development structures such as communality, well-living, labor-based economy, new rurality, and human development, the METACORTAL prioritizes local knowledge, community cohesion and territorial sustainability. While METACORTAL does not expressly exclude the possibility of alignment with public policy or the influence of external agents, its main strength lies in offering a methodological framework to adapt the SDGs to local scales marked by high cultural and ecological complexity. In this sense, this proposal differs from both UNWTO and UNDP models by shifting the governance axis toward emerging organizational forms rooted within the communities themselves, while also complementing these models by providing an operational pathway to align diverse global goals with local practices.

In this sense, this research proposes the design of a theoretical–methodological model relevant to tourism stakeholders seeking to promote the SDGs of the 2030 Agenda, integrate development alternatives, and develop their own understanding through alternative tourism. The model allows for a range of dimensions that must be considered when making decisions about the future and development of AT host communities. It also contributes to theoretical and methodological aspects by aligning five alternative frameworks for development and implementation in communities offering alternative tourism activities.

This paper is structured in five sections. The first one is focused on the theory of sustainable development (SD) and AT in communities and the 2030 Agenda as an important basis for the communities receiving AT. The second one describes the applied methodology. The third section shows the results and discussion and, finally, the conclusions are presented.

1.1. Alternative Structures and Alternative Tourism in Rural Communities

Alternative structures refer to forms of organization and development that distance themselves from the dominant economic model by prioritizing communal and sustainable principles. For some authors [

11], these are based on human development, communalism, the labor economy, new rurality, and good living, which transcend the logic focused exclusively on the production of material goods, which reproduces social, economic, and environmental inequalities that affect tourism-hosting communities. Within this framework, alternative structures are consolidated as integrative proposals that promote equity, sustainability, and a more harmonious relationship between people, their environment, and their culture (

Table 1).

Human development is a process of expanding people’s options, conditioned by the relationships they maintain with their environment [

12,

13]. It requires a systemic vision of the human being, understood as a dynamic suprasystem that integrates physical, social, cultural, spiritual and ethical dimensions [

14,

15]. This approach proposes that the central purpose of development is to expand opportunities for people to live fully, understanding economic growth as a means and not an end in itself [

12]. Therefore, development cannot be reduced to the simple accumulation of goods, economic indicators, or the satisfaction of basic needs; rather, it requires structures capable of harmonizing the individual with their natural and sociocultural environment.

Communality is a form of coexistence in constant construction, where differences are articulated through shared practices to generate cohesion and balance between the individual and the collective [

16]. It is also an organizing principle of social life, common goods, community and politics [

17] of indigenous peoples that is sustained in a relationship of interdependence with the territory, collective work, the exercise of community power and the symbolic reproduction of life through festivals [

18,

19]. That is, the individual is an active and co-responsible part of an intergenerational collective that produces, decides, and celebrates together.

The Economy of Labor acquires a qualitative value linked to the social and symbolic reproduction of life [

20,

21] by focusing on people and not on capital. From this perspective, work cannot be reduced to its productive or quantifiable dimension [

22]. Some authors [

21] explain it through the holistic approach of domestic units to improve the conditions for the reproduction of life, economic production, and community participation.

New rurality (NR) is a movement that revalues rural areas as sustainable settlement territories, focused on harmony with nature and the balanced development of authentic traditional ways of life [

23]. It recognizes pluriactivity, productive diversification, the feminization of labor and the circulation of knowledge and resources between countryside and cities as essential features of contemporary rural lifestyles [

24,

25]. Three approaches are positioned within NR: the reformist approach, oriented toward the design of more effective public policies; the community approach, which values autonomous community strategies; and the territorial approach, which proposes a spatial and relational interpretation of rural development [

26,

27].

Good living is a state of well-being and an opportunity to build a different society based on civic coexistence in diversity and harmony with nature, and on the recognition of diverse cultural values [

28]. It questions the foundations of modern Western development by recognizing Andean–Amazonian indigenous knowledge, promoting a way of life based on harmony between human beings and nature, on community rather than individualism, and on self-sufficiency rather than unlimited growth [

29,

30,

31]. From this perspective, overcoming the developmentalist paradigm implies a process of “decolonization of knowledge” [

32,

33], where people cease to be objects of politics and become subjects of their own transformation.

Together, the five alternative structures pose a comprehensive critique of the hegemonic development model and pave the way for a richer, more situated, and sustainable understanding of alternative tourism to promote more just, sustainable, and culturally relevant development models based on a solid foundation that strengthens organizational capacities, fosters collective decision-making, promotes gender equity, and encourages the conservation of the biocultural heritage of rural communities with tourism potential. Through them, a network of participatory and resilient governance is woven together that can become a pillar of a just transition toward more equitable and regenerative tourism models.

1.2. Theoretical Framework: Sustainable Development and Alternative Tourism in Communities

As a conceptual framework, AT is understood as recreational trips that encourage direct contact with nature and culture, and promote knowledge, respect, appreciation and commitment to the preservation of natural and cultural resources [

34]. According to the interest of the visitor, it is made up of three modalities: ecotourism, focused on leisure activities in direct contact with nature, adventure tourism, oriented towards recreational activities in relation to the challenges posed by the environment, and rural tourism referred to activities that seek to interact and coexist with rural communities through their cultural and social manifestations and way of working life.

Theoretically, the concept of AT emerged in the 1950s, became popular in the 1980s as the antithesis of mass tourism, and spread globally in the 1990s [

35]. It is also called fair tourism, responsible tourism, solidarity tourism or nature tourism [

1].

According to ref. [

3], events such as the Brundtland Report in 1987, Agenda 21, adopted at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, the Sustainable Tourism Charter of Lanzarote, Canary Islands, in 1995, the resolution of the UNWTO General Assembly in Istanbul in 1997, the European Charter for Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas of France in 1999, the proclamation of the UN International Year of Ecotourism in 2002, the Declaration of Quebec, Canada in 2002 and the proclamation of the United Nations in 2017 as the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development, have marked the background of alternative tourism and, based on its characteristics, have committed it as a means to favor SD.

In this regard, research on AT has been increasing in recent years [

36], focusing on perspectives that challenge the pro-growth ideology of mass tourism and promote local emancipatory alliances to foster alternatives beyond global capitalism [

37], as well as on the impetus for sustainable development in rural areas, particularly those with lower economic levels, through the utilization and enhancement of existing tourism resources [

38], and the analysis and measurement of sustainable change, along with social and cultural aspects and responsible governance models [

39]. Regarding SD in communities from the perspective of AT, analysis and theoretical models have been addressed, as well as empirical studies in different countries. For example, among the former, ref. [

6] analyzed the conceptualization of tourism sustainability from the duality of AT and mass tourism, where AT has generated tourists aware of the preservation of natural and cultural resources and that consequences depend on local aspects such as politics, social, cultural and natural conditions. Ref. [

35] argues that research on AT is essential for achieving true sustainability, as AT has the potential to effectively diversify the local rural economy, contributing to economic stability, income generation, and employee skills development in small settlements [

40].

Ref. [

3] proposed a responsible approach to minimize the negative impact of tourism on the local culture and environment, through observation and prior study, collaboration in planning and the creation of a sustainable tourism product. Ref. [

41] concluded that it is essential to rethink tourism in all its dimensions to focus on achieving human development and good living, in order to make it sustainable and inclusive. Ref. [

42] identified two conceptions of AT: the reaction to mass consumerism, which entails environmental and social problems when it becomes massive, and the response to Third World exploitation, which has a restricted scale and is not a viable alternative to conventional tourism.

Regarding empirical studies, some point out that not all projects have been successful in the implementation of AT. Ref. [

4] argued that this tourism can be beneficial for Mayan communities due to its historical and cultural richness, but it is necessary to ensure its implementation in a sustainable manner to avoid negative impacts, as in the case of ref. [

1] who carried out an evaluation of the social feasibility of AT in a community with natural and cultural attractions. Among the works with positive results are those of ref. [

43] on ecotourism and ref. [

5] on protected areas for AT through activities and the preservation of natural and cultural heritage.

In the literature, it can be observed that AT implemented in rural communities has made it possible to achieve the objectives of the 2030 Agenda due to good practices of cooperation and collaboration with internal and external actors interested in improving socioeconomic conditions and as a sustainable local development option, due to the potential benefits, such as the strengthening of social welfare, promotion of comprehensive rural development and preservation of both natural and cultural resources [

44].

1.3. 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in Communities Receiving Alternative Tourism

Tanguay et al. (2010, in [

45]) pointed out that the broad definition of SD indicators can generate multiple interpretations, which makes their application and use difficult. In addition, the absence of standardized and universal categorization techniques and perspectives to design indicators at the municipal (local or community) level, together with access restrictions to specific data, can also make it difficult to quantify and qualify them. For this reason, Ref. [

46] proposed that the indicators be identified within the main systems within the SD framework: the establishment of a method to identify them and the evaluation of sustainability and viability of human development at various levels of the social structure.

According to ref. [

45], several organizations have instituted sustainability indicators aimed at the tourism sector since the 1990s, such as the European Union, the Global Council for Sustainable Tourism, the International Network for Regional Economic Mobility and Tourism, and the World Organization of Tourism (WTO), which has adopted more than 500 indicators, quality seals and ISO standards focused on urban spaces and destinations that promote sustainability.

Another transcendental example is the 2030 Agenda, which seeks to unify efforts between countries for a sustainable world, for which they approved 17 objectives and 169 goals of universal application that came into force at the beginning of 2016 [

47], which focus on a reduction in poverty, environmental protection and increased equality among the governments that make up the General Assembly of the UN. In a timely manner, the UN and the [

7] recognize that, through tourism activity, contribution can be made for the achievement of objectives 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 17; and, in particular, with goal 8.9 [

48].

Based on this background, recent research on tourism and SDGs has been addressed by [

49], who proposed a model in Italy to interpret the 2030 Agenda at the municipal level as an integrated system that responds to the global pressures of sustainability and SDGs, as well as its integration in the decisions and governance of the city, which allows an alignment with higher levels of government. They add that it is necessary to implement and compare the model in other contexts and municipalities. Ref. [

50] addressed the multidimensional relationships of standard of living, access to education and health services. Ref. [

51] proposed a meta-governance mechanism as a tool to monitor and improve the way in which sustainable policies are implemented. Ref. [

52] argued the need to approach tourism from critical thinking to study various issues such as the inclusion of indigenous and alternative paradigms to expand the possibilities of consideration, the importance of degrowth and the transition towards a circular economy as viable alternatives to the economic growth of the neoliberal model.

2. Materials and Methods

The general objective of this research was to design a theoretical–methodological model for communities engaged in alternative tourism, grounded in the Sustainable Development Framework of the 2030 Agenda and in five alternative development structures.

To achieve this general objective, three interrelated specific objectives were established to guide the methodological design:

To identify, through a systematic literature review, the conceptual relationships between alternative tourism (AT), the 2030 Agenda, and alternative development structures.

To model and explain these relationships through a meta-theoretical approach, resulting in the formulation of the theoretical–methodological model called METACORTAL.

To propose an applicable methodological process for implementing the METACORTAL model in rural communities engaged in AT.

This study follows a theoretical design with an exploratory–descriptive scope and a mixed-methods approach. Its methodological process was developed in three sequential phases, as illustrated in

Figure 1:

Phase 1. Theoretical review and content analysis.

To address the first objective, a qualitative content analysis was conducted following the technique proposed by [

54], applied to primary, secondary, and tertiary sources on alternative tourism (AT) and sustainability. This analysis enabled the identification, classification, and quantification of key AT categories (e.g., activities, principles, community-based practices), which were then aligned with the goals, targets, and indicators of the 2030 Agenda (UN, 2015 in [

47]).

A semantic correlation exercise was carried out between key SDG terms and central concepts from the theoretical framework of AT. Some of these terms included: sustainable local development, community participation, cultural and environmental conservation, responsible governance, circular economy, and good living. This mapping allowed for the identification of significant interconnections between alternative tourism, global sustainability, and local development strategies.

Phase 2. Alignment and structuring of the model.

Afterwards, an alignment matrix was developed linking AT components with the SDGs. These results were then compared with the theoretical–propositional framework of the five alternative development structures (ADS): human development, communality, labor-based economy, new rurality, and good living, following the METACORT model approach [

54]. The theoretical modeling was based on a relational analysis of variables, which led to the design of the METACORTAL model. This process incorporated theoretical design principles such as conceptual triangulation, internal coherence, and systematic logic among constructs.

Phase 3. Validity assessment and model reliability.

To strengthen the academic robustness of the proposed model and address the second and third objectives, explicit criteria for evaluating validity and reliability were incorporated, both in the construction and application of the model:

Conceptual and content validity: ensured through theoretical alignment of the METACORT model with internationally recognized frameworks (e.g., the 2030 Agenda), as well as the systematic integration of key terms and the five ADS.

Reliability and replicability: assessed using the five methodological criteria proposed by [

55]—data accessibility, georeferencing, time series, applicability, and interpretative clarity—and complemented with additional quality criteria from [

46,

56,

57,

58]: relevance, comparability, communicability, representativeness, and contextual pertinence.

Practical applicability: the resulting indicators were categorized into two types: (a) theoretical (derived from secondary sources and statistical data), and (b) applied (obtainable through fieldwork and semi-structured interviews). This classification enhances the model’s feasibility and adaptability to specific community contexts.

When it was necessary to adapt an indicator for local application, it was marked with an asterisk (*) following [

59], ensuring that its essence and contextual relevance were preserved.

Systematization of the Process

The analysis results were systematized through explanatory tables showing the relationships between AT and the SDGs, grouped into economic, social, and environmental dimensions. These tables reveal the underlying logic of the METACORTAL model, which is proposed as a tool to guide participatory processes of sustainable planning in rural communities engaged in alternative tourism.

3. Results

Relationships of AT carried out in communities with the objectives, goals and indicators of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

47] for economic, social and environmental issues are presented in

Table 2.

The three economic objectives focus on promoting productive activities, creating decent employment, ensuring equality, and sustainably using marine resources for long-term conservation. These goals are supported by six specific targets and eight indicators related to AT. Additionally, ten social objectives address community challenges such as education deficiencies, poverty, climate change, inequality, and gender equity, pursued through 14 goals monitored by 19 indicators.

The seven environmental SDGs relevant to tourism in these communities emphasize the responsible use of natural resources, outlining 17 targets with deadlines for 2030 and involving various stakeholders in environmental management, monitored by 22 indicators. However, the lack of community adaptation limits these objectives’ effectiveness as analytical tools. Therefore, tourism stakeholders must adapt the SDGs to ensure their relevance and effective application in promoting AT development.

The analysis of 15 out of 17 SDG objectives remains inconclusive, excluding objectives 2 and 17 due to insufficient links to alternative tourism and sustainable development. Nevertheless, reconsidering these objectives could be valuable; for instance, objective 2’s focus on sustainable food production relates to alternative tourism through agritourism and culinary activities. Similarly, objective 17’s emphasis on partnerships could highlight internal collaborations among local stakeholders in tourism development, connecting to community-focused strategies in state and municipal development plans.

3.1. General Count of the Relationships of the 2030 Agenda SDGs with AT

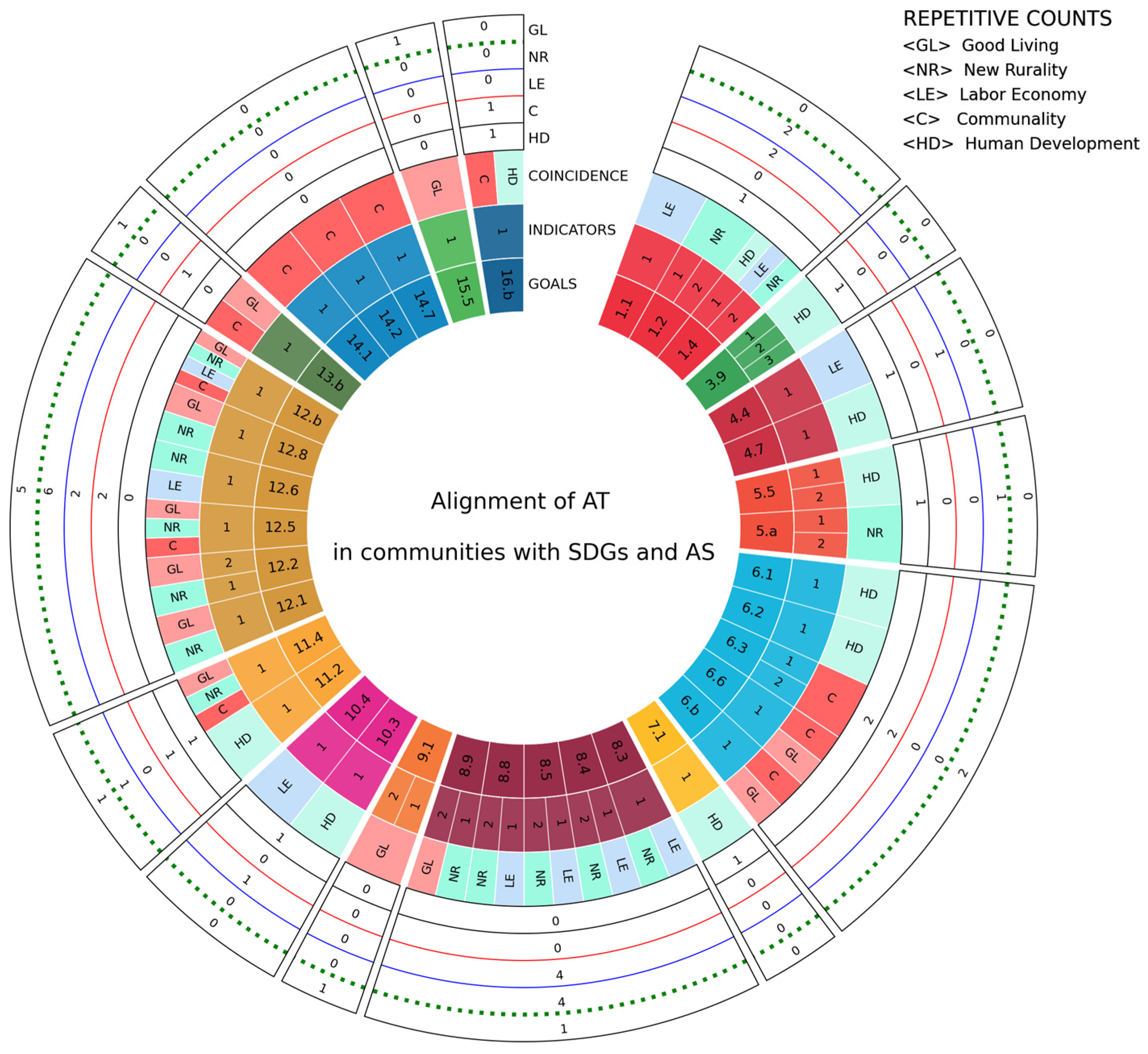

Based on

Table 1, a general assessment was conducted on the objectives, goals, and indicators from the 2030 Agenda that are linked to AT, along with the results from a theoretical analysis of how these indicators could be adapted and monitored within communities (

Figure 2). In total, 15 objectives, 36 goals, and 49 indicators were identified as relevant. Of those 49 indicators, 33 are suitable for application in the field using mixed research methods, while 43 could be monitored theoretically through secondary and tertiary research. Three indicators were deemed inapplicable due to their sensitive nature, as they require theoretical treatment and are not directly related to the main objective of this research. Among the combined field and theoretical results, 60 indicators require adaptation (*) to suit local contexts, while 16 can be applied as outlined by [

59].

Specifically,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 present the relational count of the SDGs with AT in economic, social and environmental issues, as well as the way in which they are proposed to be implemented (applied and theoretical) in receiving communities.

In the economic theme (

Table 3), three objectives were obtained through six goals and eight indicators. According to its application in communities, six applied indicators that could be monitored in the field and seven theoretically were identified. Finally, 10 of the indicators need to be adapted (*) for their application.

In the social theme (

Table 4), ten objectives were obtained through 14 goals and 19 indicators. According to their application in communities, 19 indicators were identified that could be monitored and applied in the field, of which all must be adapted (*) and 17 theoretically, in which 11 require adaptation (*).

Regarding the environmental dimension (

Table 5), seven objectives were obtained through 17 goals and 22 indicators. In order to be applied in communities, eight indicators were identified that could be monitored in the field, all of which require adaptation (*), 19 theoretically, of which 12 must be adapted (*) and three as not applicable.

3.2. Relationship of Alternative Tourism, 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Alternative Development Structures

Figure 3 shows the relationships that were identified between AT, based on the SDGs of the 2030 Agenda, and AS. As can be seen, AT is related to at least one indicator and one AS, and only in the cases of indicators 6.3.1, 6.3.2, 14.1.1, 14.2.1 and 14.7.1 do not present coincidence with AS but a direct relationship with AT.

In addition,

Figure 3 shows the relationship between AT and AS for each SDG in communities, in which 31 relationships were noted in total. In this sense, the AS of HD integrated a greater relationship with nine repetitive counts. Conversely, communality, LE and NR were perceived to be less related with five repetitive counts for each one, and in coincidence with SDG number 12, and the others with a different distribution. For the case of good living (GL), an average relationship was perceived with seven repetitive counts in total.

Likewise,

Table 6 shows the relationship of AT with AS for each goal/indicator, in which a total of 43 relationships were observed. For this case, AS of NR integrated a higher relationship with 14 repetitive counts and in the opposite direction. Communality was perceived with a lower relationship, with seven repetitive counts. In the case of GL, a relationship of 12 repetitive counts was perceived and for the cases of LE and HD, 10 repetitive counts, each coinciding with the goals/indicators 1.4.1, 1.4.2 and the others in a different distribution.

In the context of the discussion, the greatest alignment between AS, SDGs, and AT is in the area of HD, as it addresses global priority issues targeted by the 2030 Agenda. The least alignment was found in LE aspects and NR, although they still demonstrated some connection to AT. It is important to note that the relationships analyzed at the objective level were more general and broader, while the analysis of goals and indicators revealed more nuanced results. In this regard, NR showed a higher degree of alignment, particularly in gathering quantitative data to assess community conditions and monitor economic and environmental changes. Conversely, communality exhibited less alignment, likely due to the lower emphasis on qualitative aspects related to communal features such as cultural and natural value, as well as worldview. In conclusion, following [

41], it is important to reconsider tourism in all its dimensions with a focus on HD (at a more specific level) and GL (at a broader level). While these concepts have yet to fully manifest in the sustainable tourism cycle related to AT, progress in incorporating each AS is on a promising path.

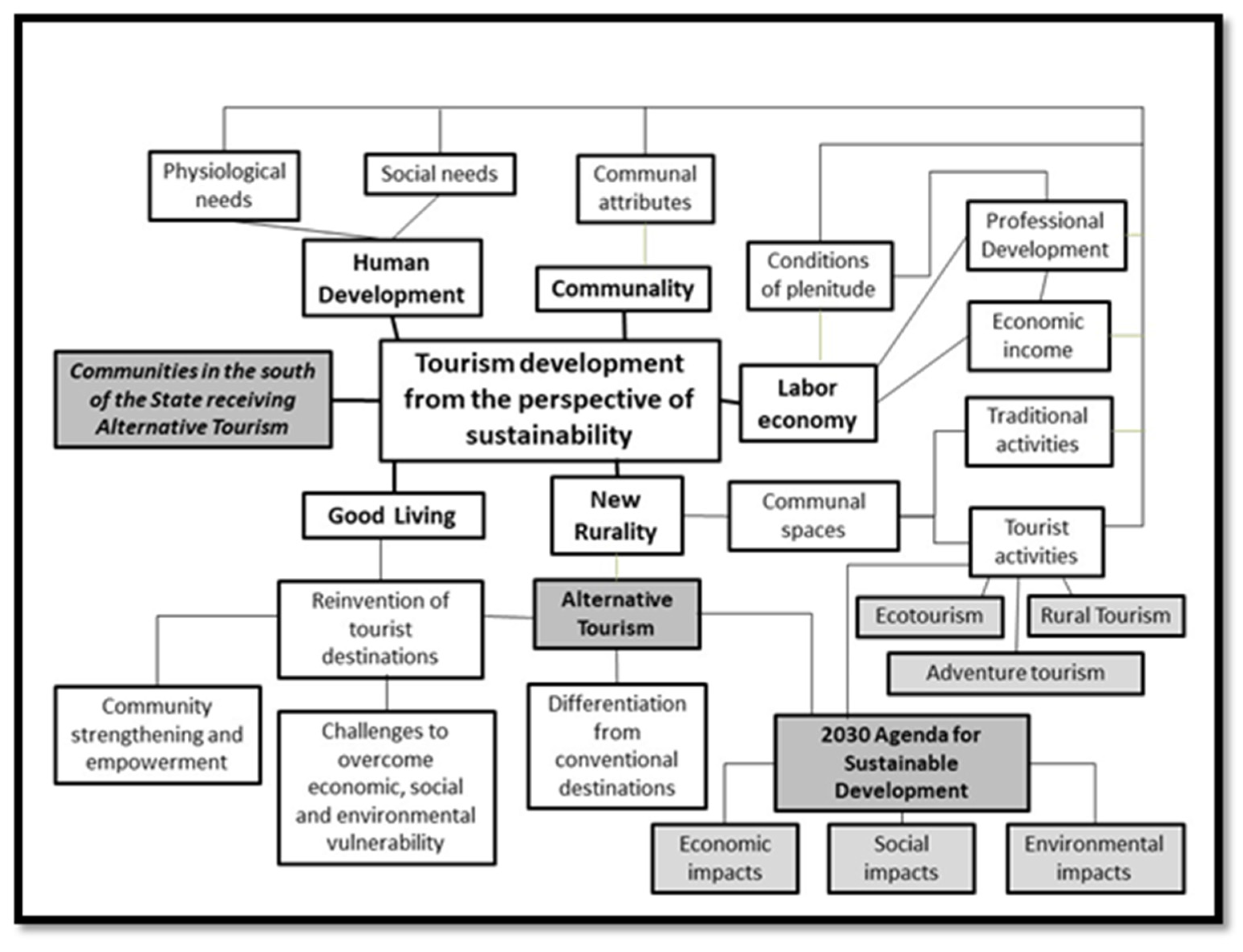

3.3. Modeling and Explanation of Metatheory Relationships: METACORTAL Theoretical–Methodological Model

The model presented in

Figure 4 shows the adaptation of [

54] METACORT to the METACORTAL, with a specific focus on the AT section, which distinguishes the two models (highlighted in grey). This adaptation customizes the model for a type of tourism tailored to the needs and potential of communities, aligned with SD. The proposal prioritizes communities receiving AT, promoting sustainable tourism development that addresses the economic, social, and environmental aspects of the SDGs from the 2030 Agenda, which all stakeholders must consider.

HD plays a central role by emphasizing the inherent value of individuals, prioritizing both physiological and social needs to foster holistic development within a harmonious socio-environmental interaction. Communality reinforces the principles and values that foster strong connections with both people and the natural environment, protecting and preserving shared resources and cultural heritage. Between HD and communality lies the necessity of income generation, which should align with both structures to support their goals. LE factors balance professional development, economic gains, and overall well-being, allowing individuals to assess whether their income genuinely enhances their quality of life beyond capitalist standards.

In tourism, NR plays a necessary role in connecting traditional community activities with new development opportunities. Communities with tourism potential often face increased vulnerability, especially concerning their natural resources. Therefore, communal spaces used for traditional and tourist activities should focus on low-impact tourism that promotes sustainability and ensures long-term community development. AT offers a differentiated approach from conventional tourism, as ecotourism, rural tourism, and adventure tourism contribute to the SDGs by addressing economic, social, and environmental impacts. Finally, in terms of GL, the community can enhance its well-being through AT, using tourism as a tool for empowerment and the reinvention of tourist destinations for future generations.

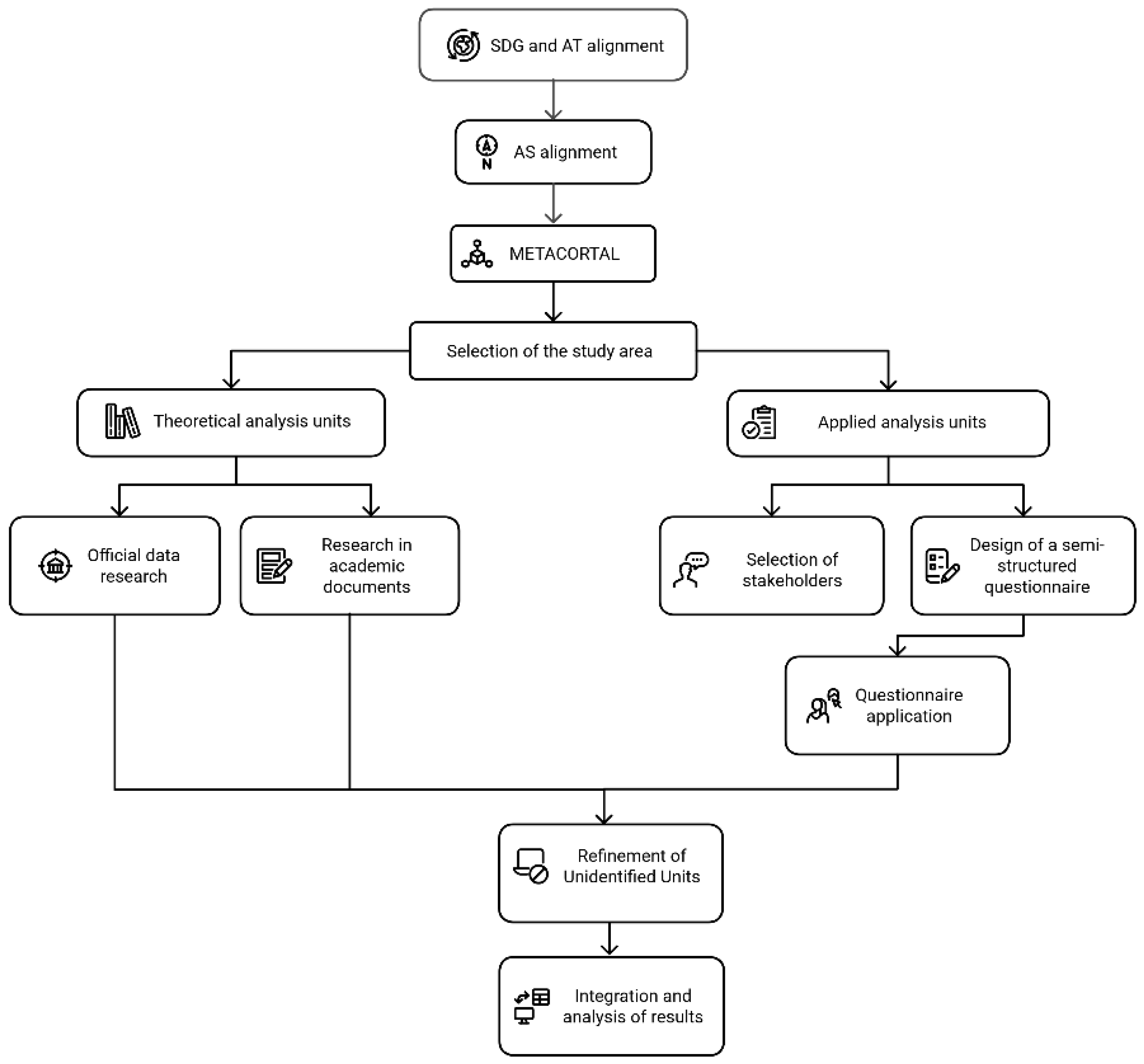

3.4. Proposal of the Methodological Process for the Implementation of the METACORTAL Model in Rural Communities

Figure 5 illustrates the application process of METACORTAL. This process begins with the alignment of the SDGs with alternative tourism, followed by their subsequent alignment with alternative structures, which enables the selection of the study area. This area may have rural or indigenous characteristics and may be geographically close to or integrated with natural and cultural tourist attractions or resources.

In the second stage, METACORTAL is applied through two approaches: theoretical and applied units of analysis. In the theoretical approach, information will be gathered from official documents issued by different levels of government, prioritizing local, municipal, and state regulations related to alternative tourism in communities. Additionally, a documentary review of academic and scientific studies will be conducted to collect relevant information for the selected study area.

In the applied approach, key informants will be identified—individuals residing in the community who are involved in tourism-related initiatives, such as local authorities, teachers, and entrepreneurs, among others. Based on METACORTAL, a semi-structured questionnaire will be designed to obtain information on the previously identified relationships between the SDGs and alternative structures in alternative tourism. Once developed, the questionnaire will be administered through interviews with the selected key informants during field visits. The snowball sampling method may be employed, provided that the new informants meet the established selection criteria.

After obtaining the results from both the theoretical and applied units of analysis, those that were not identified will be filtered out, with an explanation of the possible reasons for their absence. Finally, the identified units will be integrated and analyzed across economic, social, and environmental dimensions, regardless of whether their analysis was exclusively theoretical, applied, or a combination of both in each dimension.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the relevance of a theoretical and methodological model that integrates alternative development structures and the 2030 Agenda in communities hosting alternative tourism. In line with previous studies [

1,

5], it is reaffirmed that TA management should focus on local communities, as this maximizes economic, social, and environmental benefits while mitigating negative impacts. The identification of 15 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as applicable in this context confirms the potential of TA as a sustainable development tool.

From a theoretical perspective, a substantial alignment was evident between the AT, the SDGs, and the EAs. In particular, the structure of human development showed the greatest overlap, reaffirming its centrality in the TA approach. This result is consistent with approaches such as those of other authors [

35,

41], who emphasize that rethinking tourism based on human development and good living is key to achieving genuine sustainability. In turn, other frameworks, such as new rurality and the labor economy, also demonstrated significant links, especially at the level of goals and indicators, reinforcing the idea that traditional community practices can be articulated with new economic opportunities through AT.

However, communality showed less alignment between AT and ES with the SDGs, highlighting the limitations of international indicators in capturing fundamental qualitative and symbolic aspects of community dynamics, such as social integration, cultural identity, and symbolic reproduction. This gap between global metrics and local realities emphasizes the need for contextualized adaptation methodologies for the SDGs to be truly useful in managing sustainable tourism development in rural communities.

In response to these limitations, the methodology used in this study proposed a relational analysis between SDG goals, objectives and indicators with the EAs through the METACORTAL model. This integration allowed for the identification of central connections between sustainability, tourism and local and global development policies and contributes a proposal to address the problem pointed out by Tanguay et al. (2010 in [

45]) regarding the absence of standardized techniques for applying indicators in local contexts. Thus, the division between theoretical and applied analysis units, together with the use of validated evaluation criteria [

55], strengthened the methodological clarity and the relevance of the analyzed data.

It is also emphasized that METACORTAL offers both a robust conceptual framework and a clear and replicable methodological process for implementation in rural communities. This process facilitates the participation of internal and external stakeholders, which is essential to ensure shared governance and the impact of AT in terms of sustainability. In this regard, we agree with some authors [

41] that it is essential to consolidate evaluation mechanisms that guarantee that AT effectively contributes to human development and good living.

5. Conclusions

The theoretical and practical relationship between alternative tourism, the Sustainable Development Goals, and alternative structures is emerging as a potentially transformative framework for host communities. The results show a broad correspondence between SDG goals, objectives, and indicators with AT and alternative structures, but identify the need to adapt these international frameworks to local socio-territorial realities. While the indicators are standardized for global comparability, they lose effectiveness when faced with contexts with high levels of cultural, ecological, and organizational diversity. This (global–local) tension highlights a structural challenge in operationalizing sustainability at the community level.

The articulation between AT and alternative structures, such as human development and good living, reveals a potential that has not been exploited by conventional tourism development schemes. Communities require mechanisms to integrate quantifiable indicators, as well as ways to recognize and value practices and knowledge that are not always visible within the institutional logic of the SDGs. In this sense, AT is positioned as an ethical and strategic alternative to promote a deeper transformation of the tourism model, provided its implementation is accompanied by processes of participatory governance, community strengthening, and territorial justice.

The METACORTAL model constitutes an innovative methodological contribution for the analysis and monitoring of the relationships between alternative tourism, the Sustainable Development Goals, and alternative structures, while offering a viable path for implementation in community contexts. However, its effective application requires the strong commitment of the communities involved, as theoretical and technical advances would lack impact without a collective will to promote alternative tourism as a development option. To this end, local technical capacities, institutional support, and coherent regulatory frameworks are essential. In this regard, it is recommended to begin with community self-assessment processes and participatory certification mechanisms, supported by partnerships involving local, academic, and governmental stakeholders. These actions would contribute to strengthening the model’s ownership and its sustainability over time.

METACORTAL presents limitations in the design of flexible, applicative methodological instruments, as well as in the adaptation of SDGs to the specific characteristics of the community under study. Furthermore, structures such as communality and good living require more sensitive and appropriate approaches to capture their symbolic, cultural, and relational dimensions, as they often fall outside traditional measurement frameworks. Furthermore, the lack of standardization in community-level evaluation and monitoring methods would be a challenge for its implementation. Therefore, its application in different geographic and cultural contexts is suggested, allowing for the evaluation of its feasibility and effectiveness contextualized in diverse territories.

Future lines of research focus on the analysis of SDG 2 (zero hunger) and SDG 17 (partnerships for the goals), which were not fully addressed in this study due to their apparent direct disconnect from AT. However, they could be addressed through approaches such as agrotourism, collaborative economies, and the cooperation of different actors that would open up new avenues for integration between sustainability, territorial development, and community-based tourism. It is also important to contribute to strengthening planning, legitimization, and social appropriation processes in sustainable tourism projects through models of co-creation of sustainable strategies and participatory governance, involving communities, researchers, and public policymakers. Likewise, it proposes rethinking sustainability as a dynamic and contextualized process, with methodological approaches that articulate the local with the global and the quantitative with the symbolic, incorporating local knowledge, cultural practices, and forms of community organization as fundamental axes for the transition toward more equitable and regenerative tourism models.