Phosphogypsum Processing into Innovative Products of High Added Value

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Characterization

2.2. Research Methods

2.3. Synthesis

3. Results and Discussion

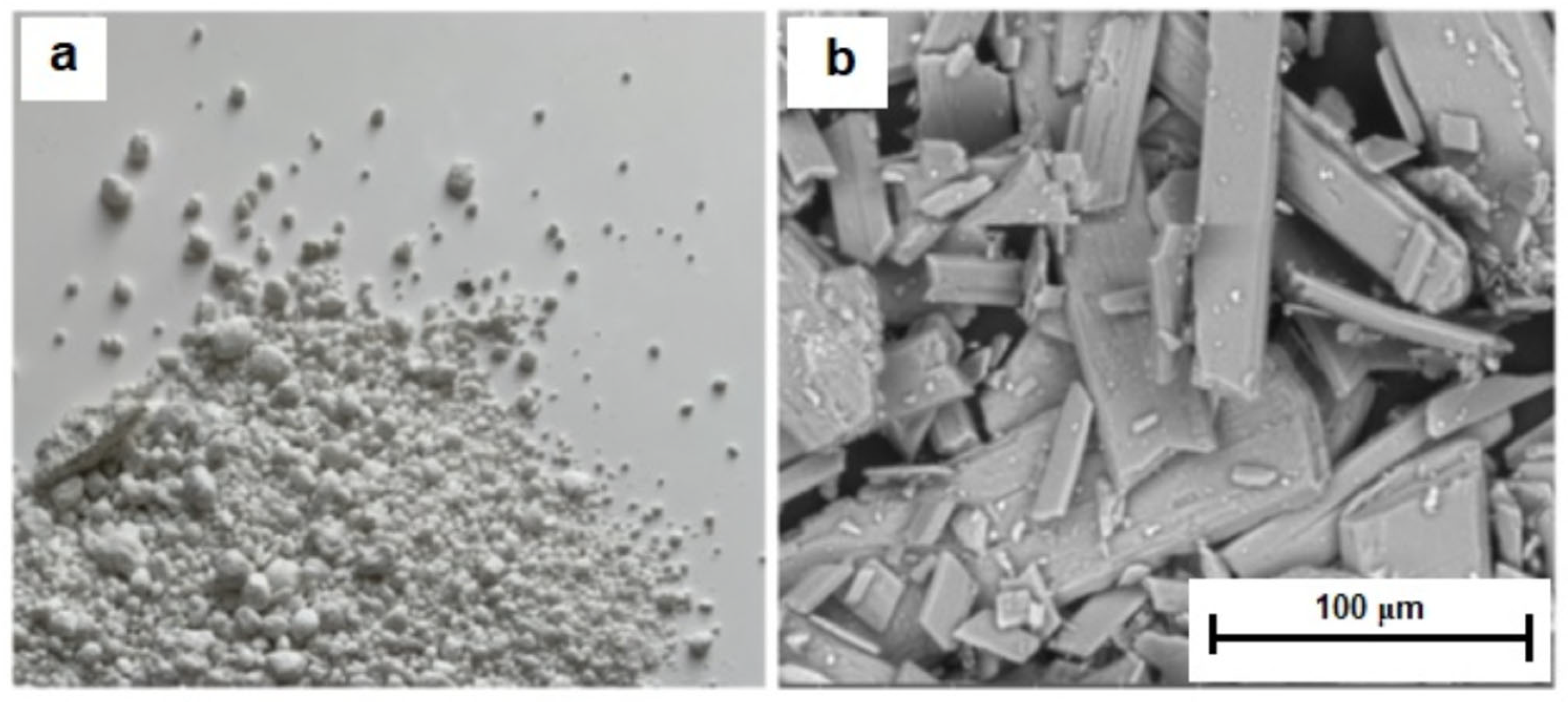

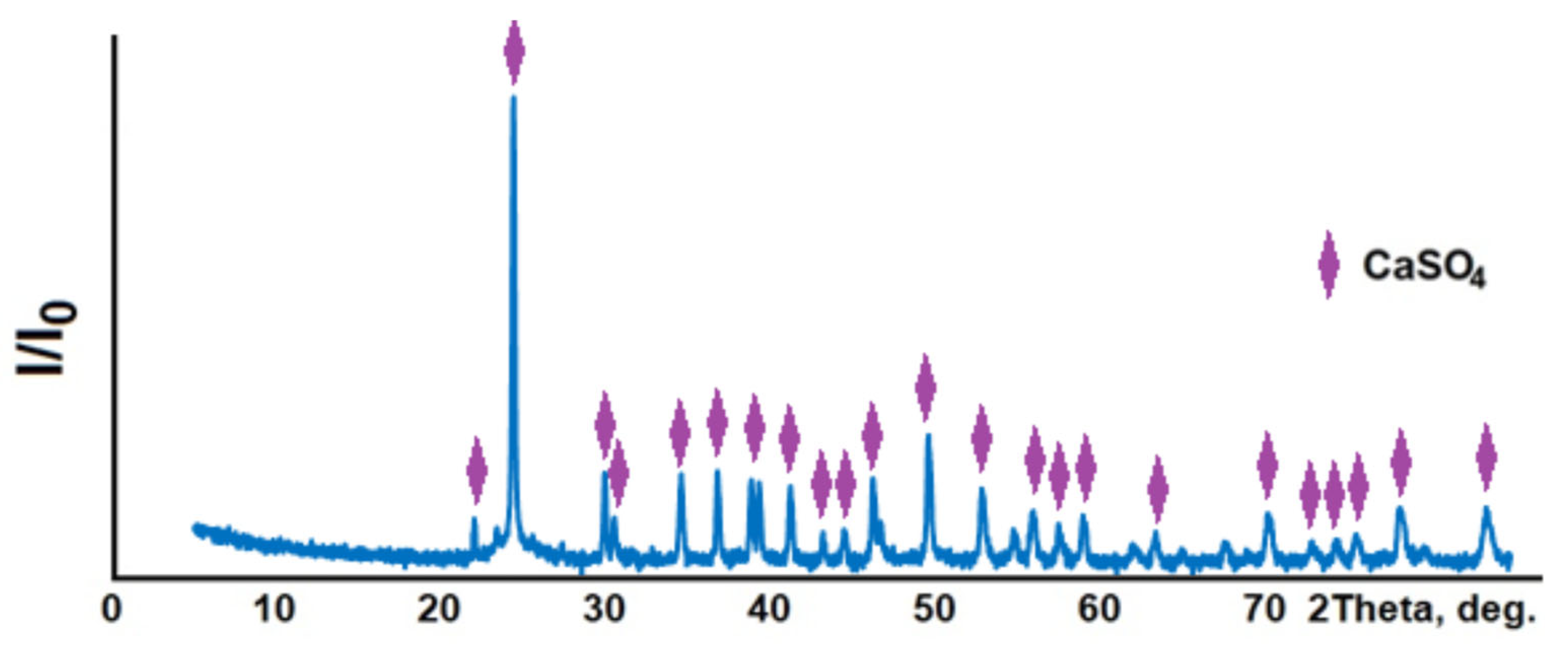

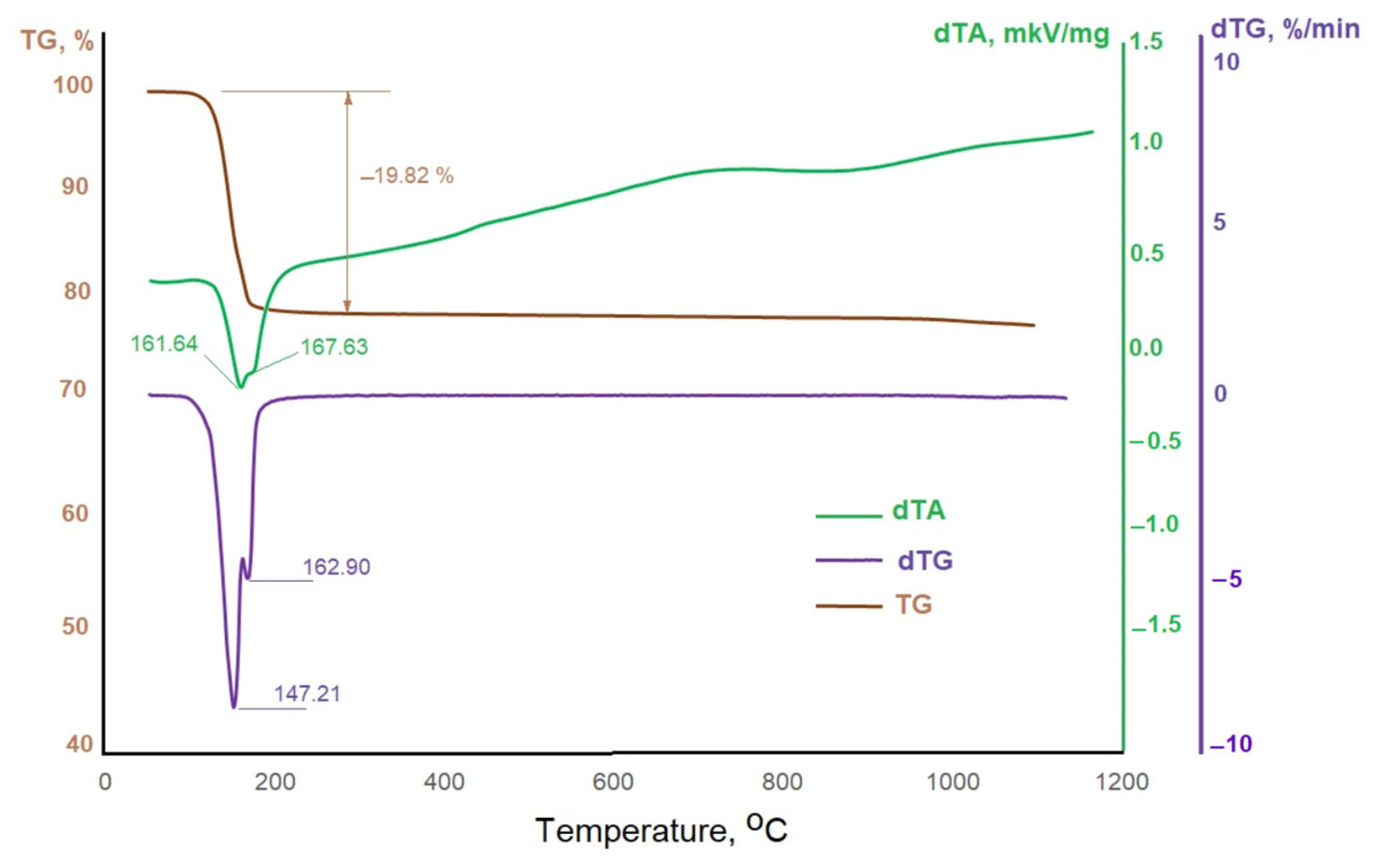

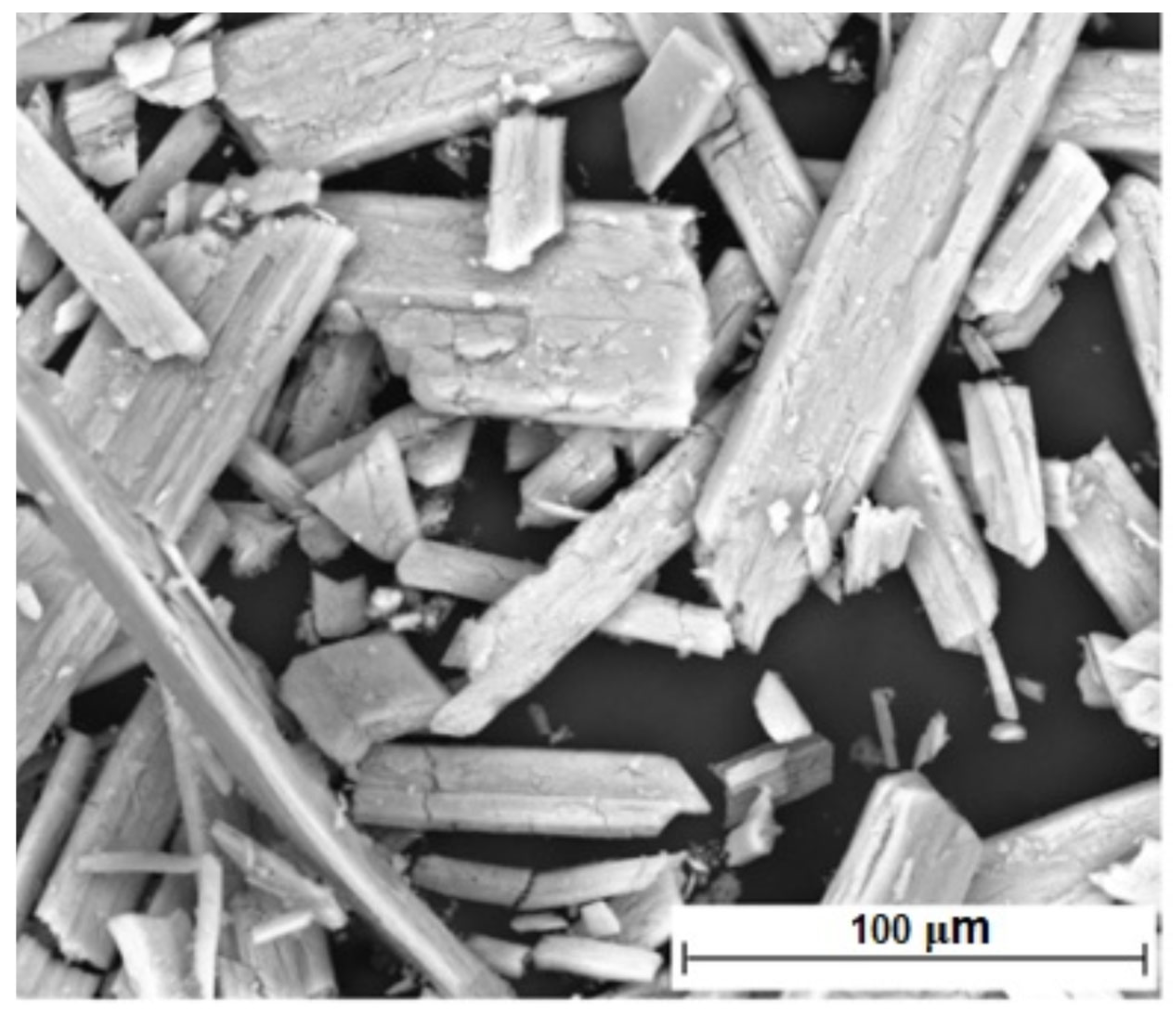

3.1. General Characteristics of Phosphogypsum

3.2. Obtaining Luminescent Pigments

3.3. A Study of the Organic Reducing Agent Type’s Effect on the Formation of Calcium Oxide from Phosphogypsum

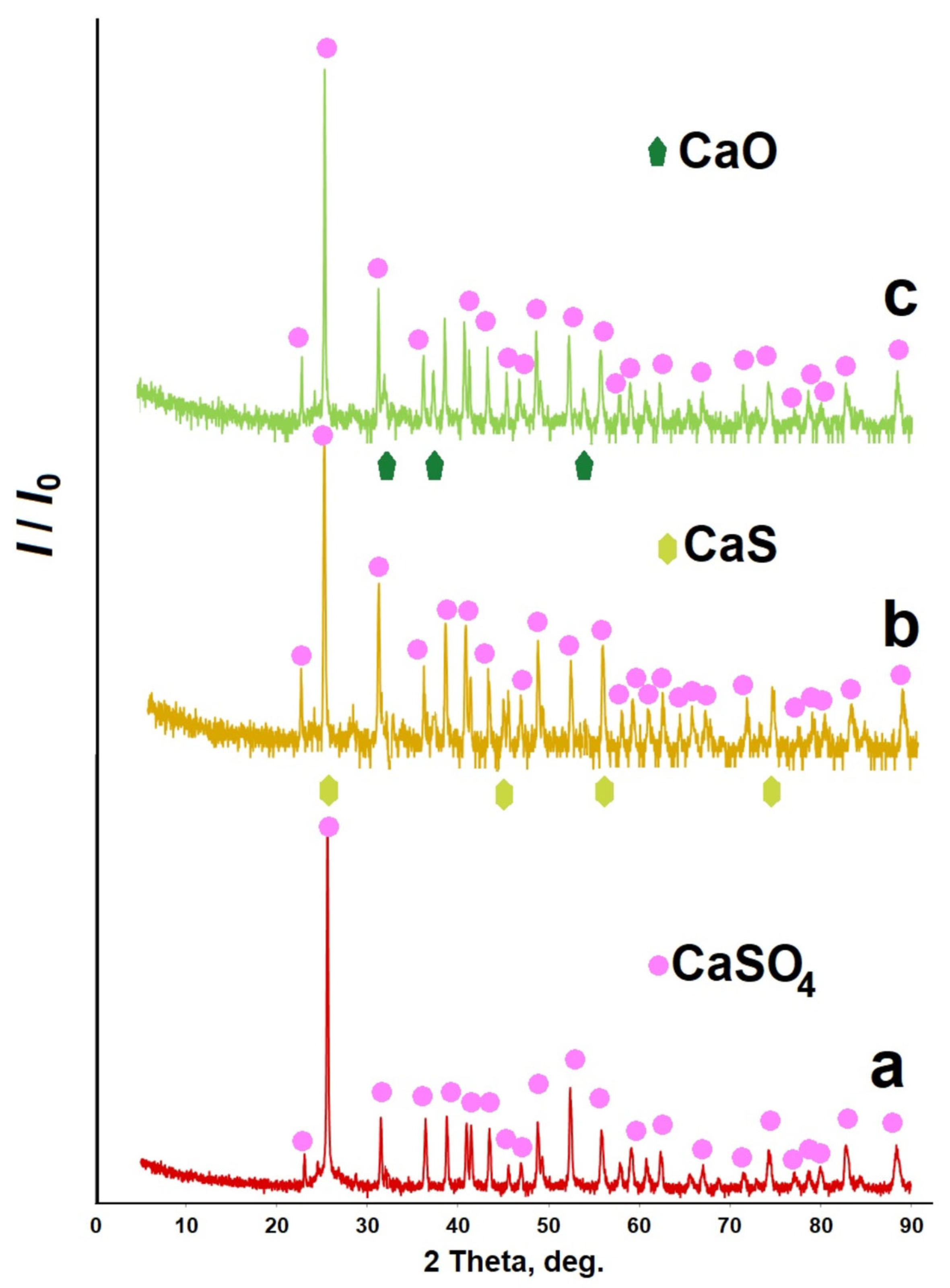

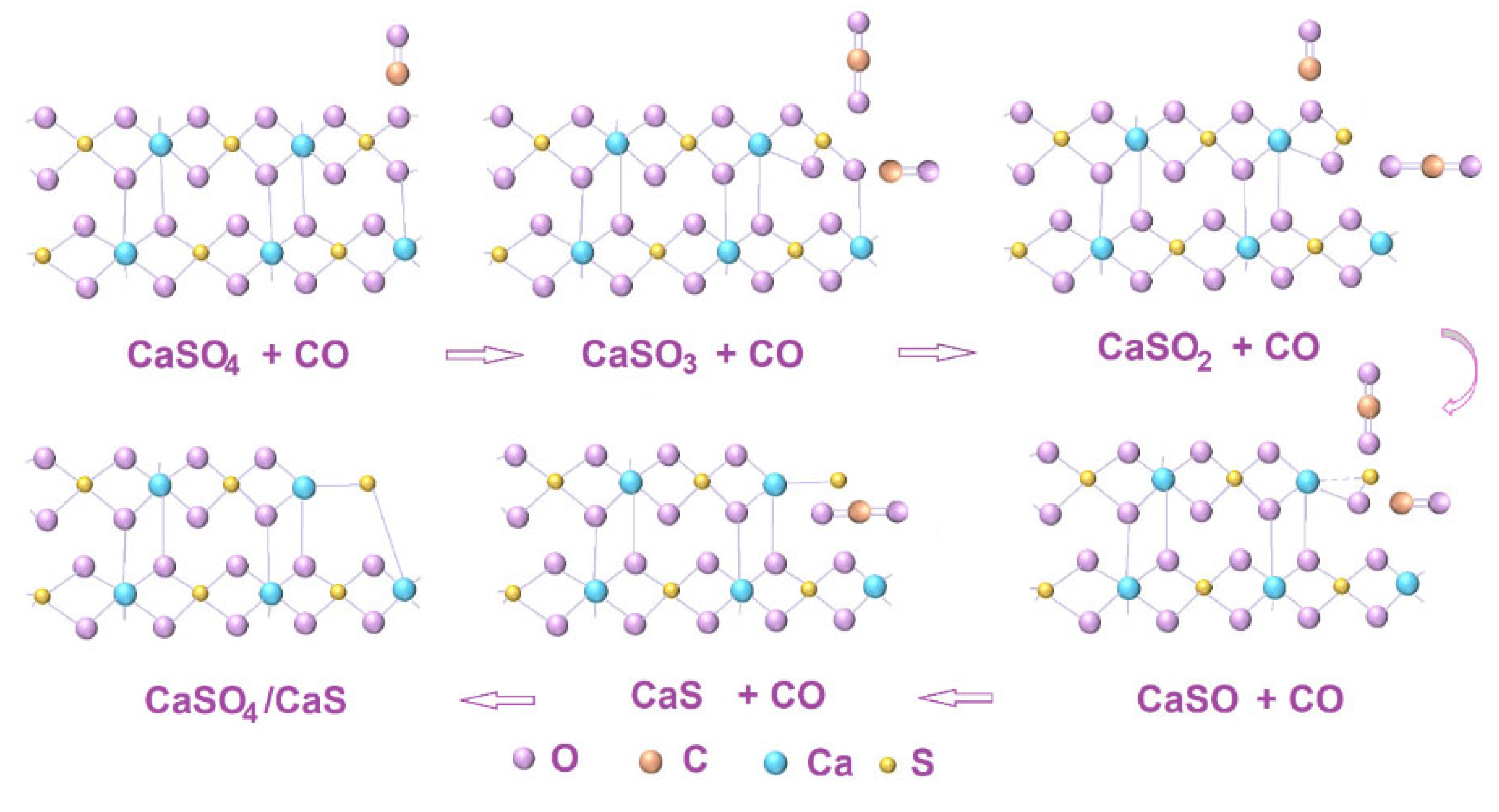

3.3.1. A Study of the Effect of Charcoal as the Reducing Agent

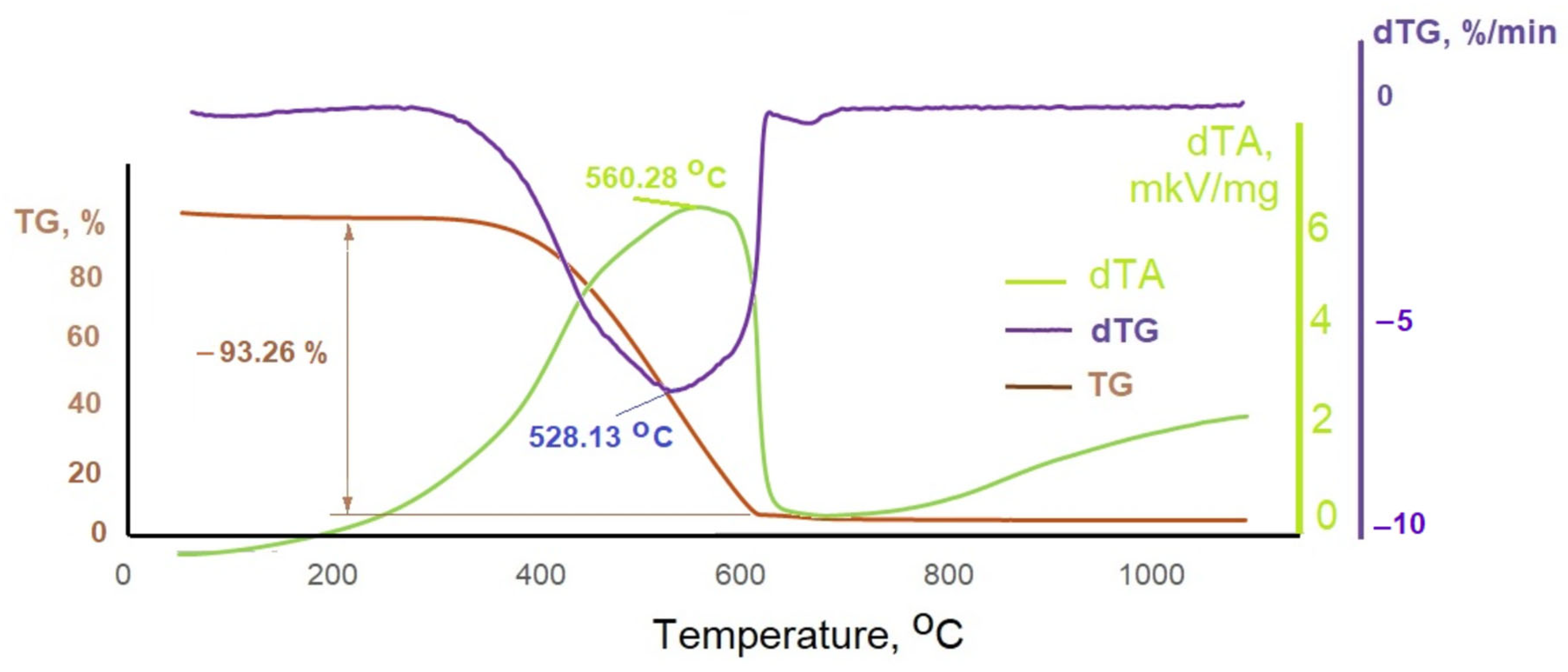

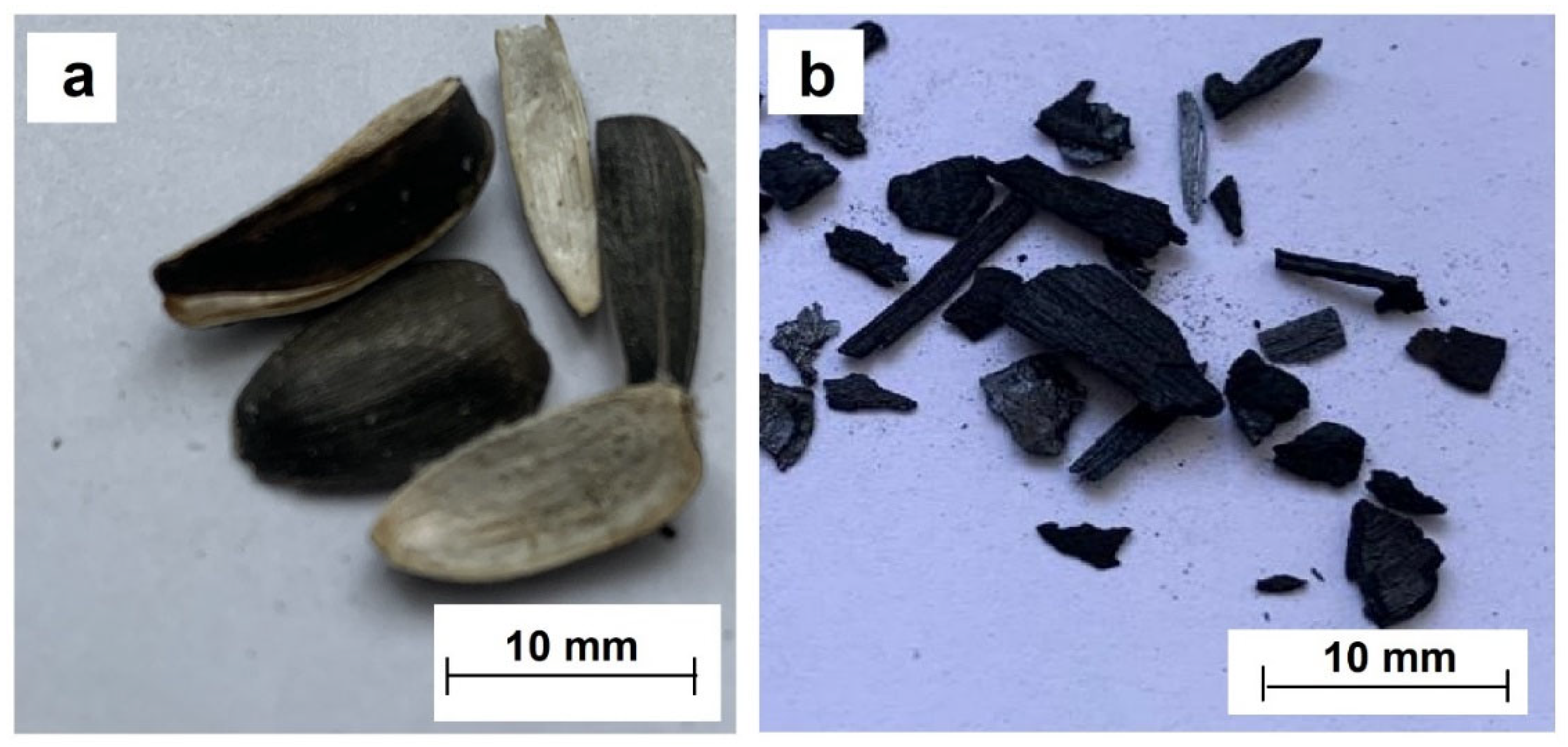

3.3.2. A Study of the Effect of Sunflower Husk as the Reducing Agent

- -

- Phosphogypsum can be processed into a sulfide- or oxide-containing material during heat treatment in the presence of sunflower husks as a reducing agent with a degree of destruction of the phosphogypsum’s main substance of calcium sulfate—up to 40% (mass);

- -

- The degree of calcium sulfate conversion depends on the temperature, the duration of heat treatment, and the amount of the introduced reducing agent. In the case of an insufficient amount of reducing agent with a high duration of heat treatment, the process of the reoxidation of the reaction product back into calcium sulfate occurs;

- -

- Calcium sulfate decomposition occurs predominantly into sulfide at low heat treatment temperatures of 800–900 °C and into calcium oxide at heat treatment temperatures of 1000–1200 °C;

- -

- When the process of phosphogypsum heat treatment is carried out in the presence of a reducing agent, a product containing calcium oxide is obtained, which opens up wide possibilities for processing large-tonnage chemical industry waste into popular products.

3.3.3. A Study of the Possibility of Using Heat-Treated Phosphogypsum in the Presence of Organic Reducing Agents to Obtain an Alkalizing Reagent

4. Conclusions

- When the process of phosphogypsum reductive heat treatment is carried out in the presence of a reducing agent (charcoal, sunflower husk), it produces new products with a high added value. For the first time, the possibility of obtaining various products by varying process conditions was established.

- When the process of phosphogypsum reductive heat treatment is carried out in the presence of charcoal at temperatures of 800–900 °C and an isothermal holding time of 60 min, it produces samples capable of glowing when irradiated with ultraviolet light. This effect is due to the formation of a composite material based on calcium sulfide and sulfate CaSO4/CaS in the system.

- The synthesized ultraviolet pigment can be included in the composition of water-based and non-water-based paints and varnishes and used to decorate various objects.

- When the process of phosphogypsum reductive heat treatment is carried out at temperatures of 1000–1200 °C, it leads to a decrease and even a loss of the luminesce ability of phosphogypsum.

- When the process of phosphogypsum reductive heat treatment is carried out at temperatures of 1000–1200 °C, it produces a composite material consisting of calcium oxide and sulfate CaSO4/CaO, which can be used for the fractionation of liquid waste from livestock farming and to obtain organomineral fertilizer.

- To obtain a high-quality alkalizing reagent, it is necessary to carry out the process of phosphogypsum heat treatment at the temperature of 1100–1200 °C for 60–90 min. This allows the significant reduction of the temperature of the thermal decomposition of calcium sulfate (by 300–500 °C).

- The technological methods developed allow the usage of chemical industrial and agricultural waste in secondary processing to produce highly innovative products that will contribute to the achievement of the sustainable development goals, in particular, “Ensuring rational consumption and production patterns”.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, T.; Zhang, J.; An, K.; Shi, N.; Li, P.; Li, B. Recent advances in recycle of industrial solid waste for the removal of SO2 and NOx based on solid waste sorts, removal technologies and mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 364, 132338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Júnior, M.J.; Medeiros, D.L.; Batista Azevedo, J.; dos Santos Almeida, E. Wind Turbine Blade Decommissioning in Brazil: The Economic Performance of Energy Recovery in a Cement Kiln Compared to Industrial Landfill Site. Sustainability 2025, 17, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; He, M.; Wu, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, M.; Yin, M.; Zhang, A.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; et al. A comprehensive review on the utilization of industrial solid waste in thermal energy storage field. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 285, 113562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranda, A.; Wachowski, L.; Kukfisz, B.; Markowska, D.; Paszula, J. Valorization of Energetic Materials from Obsolete Military Ammunition Through Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): A Circular Economy Approach to Environmental Impact Reduction. Sustainability 2025, 17, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Q.; Cheng, F.; Guo, W. Solid waste binder cemented dihydrate phosphogypsum aggregate to prepare backfill material. Miner. Eng. 2025, 226, 109249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Z.; Yang, W.; He, B. The general introduction of phosphogypsum comprehensive utilization technology in China. Yunnan Chem. Technol. 2021, 48, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Cheng, F. Study on flexural performance of double-layer bamboo phosphogypsum floor slabs. Structures 2025, 76, 09013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Fang, K.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, Q. Reverse flotation purification of phosphogypsum and preparation of high whiteness CaSO4. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 716, 136763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Dong, Y.; Zang, M.; Zou, N.; Lu, H. Mechanical properties and chemical microscopic characteristics of all-solid-waste composite cementitious materials prepared from phosphogypsum and granulated blast furnace slag. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova, M.A.; Monastyrsky, D.I.; Medennikov, O.A.; Shabelskaya, N.P.; Khliyan, Z.D.; Ulanova, V.A.; Sulima, S.I.; Sulima, E.V. Study of the Process of Calcium Sulfide-Based Luminophore Formation from Phosphogypsum. Molecules 2024, 29, 5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medennikov, O.A.; Egorova, M.A.; Shabelskaya, N.P.; Rajabov, A.M.; Sulima, S.I.; Sulima, E.V.; Khliyan, Z.D.; Monastyrskiy, D.I. Studying the Process of Phosphogypsum Recycling into a Calcium Sulphide-Based Luminophor. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asaithambi, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.-W.; Lee, B.D.; Cho, M.-Y.; Park, W.B.; Sohn, K.-S. Decay behavior of Eu2+-Activated sulfide phosphors: The Pivotal role of unique activator sites. J. Lumin. 2023, 263, 120109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Chen, W.T.; Liu, R.S. Phosphors for White LEDs. In Handbook of Advanced Lighting Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Brik, M.G.; Jary, V.; Havlak, L.; Barta, J.; Nikl, M. Ternary sulfides ALnS2:Eu2+ (A = Alkaline Metal, Ln = rare-earth element) for lighting: Correlation between the host structure and Eu2+ emission maxima. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 418, 129380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jary, V.; Havlak, L.; Barta, J.; Buryi, M.; Rejman, M.; Pokorny, M.; Dujardin, C.; Ledoux, G.; Nikl, M. Variability of Eu2+ emission features in multicomponent alkali-metal-rare-earth sulfides. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 016007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Singh, S.P.; Shim, S.; Park, W.B.; Sohn, K.-S. Discovery of a quaternary sulfide, Ba2−xLiAlS4:Eu2+, and its potential as a fast-decaying LED phosphor. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 6697–6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, J.W.; Singh, S.P.; Kim, M.; Lee, B.D.; Park, W.B.; Sohn, K.-S. A novel sulfide phosphor, BaNaAlS3:Eu2+, discovered via particle swarm optimization. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 922, 166187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Li, M.; Shen, Y.; Yu, B.; Chen, T.; Liu, X. Environmental impact and adaptation study of pig farming relocation in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 89, 106593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Study on the removal of high nitrate-nitrogen concentration from pig farm wastewater by heterotrophic and sulphur autotrophic synergistic denitrification filter process. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 318, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbede, T.M.; Oyewumi, A. Benefits of biochar, poultry manure and biochar–poultry manure for improvement of soil properties and sweet potato productivity in degraded tropical agricultural soils. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 7, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Yang, C.; Zeng, G.; Wang, L.; Dai, C.; Long, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhong, Y. Characterization and application of bioflocculant prepared by Rhodococcus erythropolis using sludge and livestock wastewater as cheap culture media. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 6847–6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Alegre, R.; Zapata-Jimenez, J.; Megias, L.P.; Saiz, C.A.; Sanchis, S.; Perez-Moya, M.; Garcia-Montano, J.; You, X. Pilot scale on-site demonstration and seasonality assessment of nitrogen recovery and water reclamation from pig’s slurry liquid fraction. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.R.; Gong, Z.Q.; Allinson, G.; Xiao, M.; Li, X.J.; Jia, C.Y.; Ni, Z.J. Environmental risks caused by livestock and poultry farms to the soils: Comparison of swine, chicken, and cattle farms. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 317, 115320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abril, J.M.; García-Tenorio, R.; Periáñez, R.; Enamorado, S.M.; Andreu, L.; Delgado, A. Occupational dosimetric assessment (inhalation pathway) from the application of phosphogypsum in agriculture in South West Spain. J. Environ. Radioact. 2009, 100, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, K.; Yu, M.; Dong, X.; Sarwar, M.T.; Yang, H. Facet-engineering strategy of phosphogypsum for production of mineral slow-release fertilizers with efficient nutrient fixation and delivery. Waste Manag. 2024, 182, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Lu, C.; Yu, Z. Historical nitrogen fertilizer use in agricultural ecosystems of the contiguous United States during 1850–2015: Application rate, timing, and fertilizer types. Earth Syst. Sci. Data ESSD 2018, 10, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, N.; Du, X.; Han, X.; Zhang, X. Transition metal atoms M (M = Mn, Fe, Cu, Zn) doped nickel-cobalt sulfides on the Ni foam for efficient oxygen evolution reaction and urea oxidation reaction. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 893, 162269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B. The pH-sensitive oxygenation of FeS: Mineral transformation and immobilization of Cr(VI). Water Res. 2023, 233, 119722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Chen, B.; Qu, G.; Liu, S.; Zhao, C.; Ren, Y.; Liu, X. Harmless treatment technology of phosphogypsum: Directional stabilization of toxic and harmful substances. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 311, 114827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Company, E.; Farrés, M.; Colprim, J.; Magrí, A. Exploring the recovery of potassium-rich struvite after a nitrification-denitrification process in pig slurry treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 847, 157574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessì, E.; Company, E.; Pous, N.; Milia, S.; Colprim, J.; Magrí, A. Reagent-free phosphorus precipitation from a denitrified swine effluent in a batch electrochemical system. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikova, T.A.; Kulikova, M.A. Modeling of coagulation processes in the reagent separation of agricultural waste. Int. Res. J. 2024, 1, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Liu, W.; Li, H.; Chen, Y. Thermal decomposition mechanism and characterization of phosphogypsum in suspension under multifactor coupling effect. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Quantity, % (Mass) | Element | Quantity, % (Mass) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 72.03 | Magnesia (MgO) | 0.09 |

| Organic matter | 24.74 | Silicic acid (SiO2) | 1.07 |

| Nitrogen (N) general | 0.44 | Chlorine | 0.17 |

| Ammonia nitrogen | 0.19 | Sulfuric acid (SO3) | 0.08 |

| Phosphorus (P2O5) | 0.18 | Oxides of A1 and Fe | 0.07 |

| Potassium (K2O) | 0.58 | Magnesia (MgO) | 0.18 |

| Lime (CaO) | 0.18 | Total | 100.00 |

| Equation Number | Reaction | ΔH, kJ | ΔS J/K | ΔG, kJ | t, °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | CaSO4·2H2O = CaSO4·0.5H2O + 1.5H2O | +83.5 | +219.4 | +18.1 | 108 |

| (2) | CaSO4·0.5H2O = CaSO4 + 0.5H2O | +20.6 | +70.5 | −0.4 | 19 |

| (3) | CaSO4 = CaO + SO3 | +404.7 | +188.1 | +349.3 | >1350 |

| (4) | CaSO4 + 2C = CaS + 2CO2 | −172.6 | +14.5 | −177 | - |

| (5) | CaSO4 + 4C = CaS + 4CO | +517.2 | +734.4 | +298.4 | 431 |

| (6) | CaSO4 + 4CO = CaS + 4CO2 | −178.4 | +14.6 | −182.8 | - |

| (7) | C + CO2 = 2CO | +172.5 | +175.6 | +120.2 | 709 |

| (8) | 2C + O2 = 2CO | −221 | +178.6 | −274.2 | - |

| (9) | CaSO4 + C = CaO + SO2 + CO | +393.4 | +409.3 | +273.5 | 688 |

| (10) | CaSO4 + CO = CaO + SO2 + CO2 | +220.9 | +233.7 | +151.3 | 672 |

| (11) | 3CaSO4 + CaS = 4SO2 + 4CaO | −1056.3 | +920.0 | −1330.5 | - |

| (12) | CaS + 2O2 = CaSO4 | −953.6 | 359.8 | −846.4 | - |

| Mass of Reducing Agent, g | Share of Reducing Agent from Stoichiometric Value, % | Relative Luminous Flux at Heat Treatment Temperature, °C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 800 | 900 | 1000 | ||

| 0.15 | 6.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 0.3 | 12.5 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.1 |

| 0.45 | 18.8 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| 0.6 | 25.0 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.25 |

| 0.9 | 37.5 | 0.18 | 0.56 | 0.42 |

| 1.2 | 50.0 | 0.2 | 0.88 | 0.61 |

| 1.5 | 62.5 | 0.15 | 0.77 | 0.57 |

| 1.8 | 75.0 | 0.11 | 0.73 | 0.55 |

| 2.4 | 100.0 | 0.1 | 0.68 | 0.48 |

| 3 | 125.0 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 0.3 |

| 3.6 | 150.0 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.16 |

| 4.8 | 200.0 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Phosphogypsum–Reducing Agent Ratio | Degree of Calcium Sulfate Destruction Δm, %, at Heat Treatment Temperature, °C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 700 | 800 | 900 | 1000 | 1200 | |

| 3.4:1 | −3.79 | 15.28 | 23.81 | 32.34 | 36.47 |

| 2.3:1 | −6.15 | −0.54 | 9.94 | 20.41 | 21.62 |

| 1.7:1 | −7.84 | −1.28 | 3.70 | 8.67 | 10.55 |

| Phosphogypsum–Reducing Agent Ratio | Degree of Calcium Sulfate Destruction Δm, %, During Isothermal Holding Time, min | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 60 | 90 | |

| 3.4:1 | 33.70 | 32.34 | 34.96 |

| 2.3:1 | 21.69 | 20.41 | 23.24 |

| 1.7:1 | 9.34 | 8.67 | 13.18 |

| Phosphogypsum–Reducing Agent Ratio | Degree of Calcium Sulfate Destruction Δm, %, at Heat Treatment Temperature, °C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 700 | 800 | 1000 | 1100 | 1200 | |

| 3.4:1 | −0.23 | 14.50 | 20.36 | 23.28 | 37.36 |

| 2.3:1 | −0.73 | 20.56 | 26.16 | 28.97 | 40.03 |

| 1.7:1 | −1.07 | 25.89 | 30.81 | 33.26 | 39.32 |

| Phosphogypsum–Reducing Agent Ratio | Degree of Calcium Sulfate Destruction Δm, %, During Isothermal Holding Time, min | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 60 | 90 | |

| 3.4:1 | 15.05 | 20.36 | 17.34 |

| 2.3:1 | 22.91 | 26.16 | 30.72 |

| 1.7:1 | 31.7 | 30.81 | 32.26 |

| Reducing Agent | Sunflower Husk | Charcoal |

|---|---|---|

| Ratio (C:O) | 1.24 | 8.47 |

| Reaction Conditions | Composition | pH | Turbidness | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 700 °C, 1 h | 3.4:1 | 7 | Very turbid | Carbon residues |

| 2.3:1 | 8 | Very turbid | Carbon residues | |

| 1.7:1 | 8 | Very turbid | Carbon residues | |

| 800 °C, 1 h | 3.4:1 | 9 | Turbid | Carbon residues |

| 2.3:1 | 9 | Turbid | Carbon residues | |

| 1.7:1 | 10 | Turbid | Carbon residues | |

| 900 °C, 0.5 h | 3.4:1 | 11 | Transparent grey | |

| 2.3:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues | |

| 1.7:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues | |

| 900 °C, 1 h | 3.4:1 | 11 | Transparent grey | |

| 2.3:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues | |

| 1.7:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues | |

| 900 °C, 1.5 h | 3.4:1 | 11 | Transparent grey | |

| 2.3:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues | |

| 1.7:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues | |

| 1000 °C, 0.5 h | 3.4:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | |

| 2.3:1 | 9 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues | |

| 1.7:1 | 9 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues | |

| 1000 °C, 1 h | 3.4:1 | 11 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues |

| 2.3:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues | |

| 1.7:1 | 9 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues | |

| 1000 °C, 1.5 h | 3.4:1 | 9 | Transparent | |

| 2.3:1 | 9 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues | |

| 1.7:1 | 9 | Transparent grey | Carbon residues | |

| 1200 °C, 1 h | 3.4:1 | 10 | Transparent | |

| 2.3:1 | 10 | Transparent | ||

| 1.7:1 | 10 | Transparent | Carbon residues |

| Reaction Conditions | Composition | pH | Turbidness | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 700 °C, 1 h | 3.4:1 | 11 | Transparent grey | Husk residues |

| 2.3:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | Husk residues | |

| 1.7:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | Husk residues | |

| 800 °C, 1 h | 3.4:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | Husk residues |

| 2.3:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | Husk residues | |

| 1.7:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | Husk residues | |

| 900 °C, 0.5 h | 3.4:1 | 9 | Transparent grey | |

| 2.3:1 | 9 | Transparent grey | ||

| 1.7:1 | 9 | Transparent grey | ||

| 900 °C, 1 h | 3.4:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | |

| 2.3:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | ||

| 1.7:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | ||

| 900 °C, 1.5 h | 3.4:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | |

| 2.3:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | ||

| 1.7:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | ||

| 1000 °C, 0.5 h | 3.4:1 | 12 | Transparent grey | |

| 2.3:1 | 11 | Transparent grey | ||

| 1.7:1 | 11 | Transparent grey | ||

| 1000 °C, 1 h | 3.4:1 | 11 | Transparent grey | |

| 2.3:1 | 11 | Transparent grey | ||

| 1.7:1 | 11 | Transparent grey | ||

| 1000 °C, 1.5 h | 3.4:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | |

| 2.3:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | ||

| 1.7:1 | 10 | Transparent grey | ||

| 1100 °C, 1 h | 3.4:1 | 11 | Transparent | |

| 2.3:1 | 12 | Transparent | ||

| 1.7:1 | 12 | Transparent | ||

| 1200 °C, 1 h | 3.4:1 | 12 | Transparent | |

| 2.3:1 | 12 | Transparent | ||

| 1.7:1 | 12 | Transparent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monastyrsky, D.I.; Kulikova, M.A.; Egorova, M.A.; Shabelskaya, N.P.; Medennikov, O.A.; Radzhabov, A.M.; Gaidukova, Y.A.; Baranova, V.A. Phosphogypsum Processing into Innovative Products of High Added Value. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6228. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136228

Monastyrsky DI, Kulikova MA, Egorova MA, Shabelskaya NP, Medennikov OA, Radzhabov AM, Gaidukova YA, Baranova VA. Phosphogypsum Processing into Innovative Products of High Added Value. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):6228. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136228

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonastyrsky, Daniil I., Marina A. Kulikova, Marina A. Egorova, Nina P. Shabelskaya, Oleg A. Medennikov, Asatullo M. Radzhabov, Yuliya A. Gaidukova, and Vera A. Baranova. 2025. "Phosphogypsum Processing into Innovative Products of High Added Value" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 6228. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136228

APA StyleMonastyrsky, D. I., Kulikova, M. A., Egorova, M. A., Shabelskaya, N. P., Medennikov, O. A., Radzhabov, A. M., Gaidukova, Y. A., & Baranova, V. A. (2025). Phosphogypsum Processing into Innovative Products of High Added Value. Sustainability, 17(13), 6228. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136228