1. Introduction

According to the United Nations (UN), nearly 90% of individuals worldwide harbor biases against women [

1]. This finding sheds light on “masculine default biases,” a form of gender bias where behaviors and traits traditionally associated with men are favored or seen as the norm, natural, or essential [

2]. Consequently, despite women constituting half the global population, our approach to addressing real-world issues and crafting solutions is predominantly based on men’s preferences, physical attributes, and typical life choices [

3]. This disparity leads to significant inequalities between women and men across various aspects of life, including rights [

4], the economy [

5] (approximately 2.4 billion working-age women lack equal economic opportunities and 178 countries maintain legal barriers hindering their full economic participation, as per the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law 2022 report [

6]), research [

7] (women accounted for 41% of researchers in 2022 [

8]), politics [

9] (for instance, as of 1 January 2025, only 27.2% of parliamentarians in single or lower houses are women with just 25 countries having 28 women serving as Heads of State and/or Government [

10]), innovation [

11] (in 2024, only 28.2% of employees in innovative companies were women [

12]), and product and service design [

13] (in 2024, only 19% of practicing industrial designers, also known as product designers, were women; women held just 11% of design leadership roles [

14] ).

While women are clearly underrepresented in these domains, it is crucial to acknowledge that certain indicators, such as life expectancy, reveal disadvantages faced by men in other contexts. For instance, in 2021, women had a projected life expectancy approximately 5.8 years longer than men [

15]. These disparities often stem from gendered social expectations, such as norms of risk-taking, reluctance to seek healthcare, or exposure to hazardous occupations, which negatively impact men’s well-being. However, it is important to note that longer life expectancy does not necessarily equate to better health outcomes for women. Women, particularly in older age, often live with chronic conditions and bear disproportionate caregiving responsibilities, both of which highlight the need for more nuanced and gender-specific approaches research and innovation [

16,

17]. To address disadvantages experienced by both genders, it is essential to examine how Research and Innovation (R&I) outcomes affect men and women differently. A “do no harm” approach is fundamental, not only to identify gender-based differences but to intentionally work toward reducing systemic inequalities through inclusive, equity-driven R&I processes [

18]. This necessitates adopting a Gender-Responsive (GR) approach in R&I. Gender-Responsive Research and Innovation (GRRI) refers to an approach that deliberately considers and addresses gender-specific needs and inequalities in R&I practices. It entails the following: (1) involving women and men in the R&I process, and (2) tailoring R&I content to meet the diverse needs and interests of women and men. This approach has the potential to save lives, resources, and time [

19]. Rather than constituting a formal theory, GRRI functions as a strategic and methodological framework embedded within broader agendas, such as Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI), where gender equality is one of the six central pillars [

20,

21]. The GRRI framework emphasizes that overlooking gender dimensions in research—such as biological differences, social roles, and access disparities—can result in biased outcomes and underinclusive technologies. It has been particularly critical in domains such as health, artificial intelligence, and climate innovation, where gender-blind models can inadvertently reinforce structural inequities or produce suboptimal results [

22,

23]. By integrating sex and gender analysis into scientific inquiry and ensuring inclusive participation, GRRI contributes to more ethical, responsible, and impactful innovation.

A robust and growing body of interdisciplinary scholarship substantiates that GRRI is not merely a theoretical construct but a practical and empirically grounded strategy that delivers measurable benefits across real-world domains. By embedding gender perspectives throughout the research and innovation lifecycle, from problem definition to design, implementation, and evaluation, GRRI ensures that outputs are more inclusive, ethical, and effective. This principle applies across multiple sectors, as demonstrated by a diverse array of illustrative studies. In the domain of

health and public policy, GRRI enhances the accuracy, inclusivity, and fairness of medical systems. Integrating sex- and gender-sensitive frameworks into clinical and diagnostic practice has proven foundational for improving health outcomes and reducing bias [

24]. Additionally, GRRI-informed interventions such as male-targeted health promotion [

25], transgender- and women-inclusive health budgeting frameworks [

26], and pandemic policies built on intersectional gender analysis [

27], exemplify how equity-driven design improves both service delivery and public trust. Moreover, innovations in digital health—such as inclusive revisions of Gender, Sex, and Sexual Orientation (GSSO) standards in electronic health records, showcase how GRRI improves data usability, clinical safety, and accessibility for marginalized groups [

28]. In

technology and innovation, GRRI acts as a guiding framework for creating equitable, accountable, and socially responsive systems. It facilitates inclusive knowledge ecosystems, challenges structural bias, and promotes co-creation. For example, digital collaboration hubs that adopt gender-responsive methodologies foster more equitable research and innovation cultures [

29]. Participatory research in machine translation involving non-binary and queer communities has yielded gender-fair systems that reduce misgendering and support linguistic justice [

30]. At a broader policy level, UN Women’s “Partnering for Gender-Responsive AI” policy emphasizes how integrating gender equity at the planning, development, and evaluation stages of AI systems leads to more just, transparent, and accountable technological frameworks, highlighting that gender responsiveness is not a side concern but a critical pillar in ethical innovation [

31]. In

agriculture and environmental governance, GRRI fosters gender justice while improving sustainability, productivity, and resilience. It enables participatory frameworks that empower women and address structural exclusion. Gender-transformative programs in East Africa have enhanced female farmers’ decision-making power and crop yields [

32]. The Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) has guided national agricultural policy across 25 countries, helping reduce inequality and improve food security [

33]. Similarly, gender-responsive forest landscape initiatives show that enhancing women’s participation, securing tenured rights, and equitable benefit-sharing leads to better ecological outcomes, stronger community learning, and governance equity [

34]. In

criminal and justice, GRRI has reshaped correctional approaches by centering gender-specific experiences, especially for women and girls. Evidence shows that gender-responsive correctional models lead to lower recidivism rates, enhanced mental health outcomes, and more humane conditions for incarcerated women [

35]. In juvenile justice, studies such [

36] highlight how practitioners integrate GRRI by adapting programs to girls’ social and emotional contexts, such as family instability and trauma histories. While impact data remains limited, these efforts underscore the potential of GRRI to make justice systems more equitable, responsive, and humane. In

research governance and innovation policy, GRRI has been operationalized through formal mechanisms that improve representation and fairness. Frameworks such as Athena SWAN, EDGE certification, and Horizon Europe’s Gender Equality Plans have promoted institutional transformation by advancing gender equity in team composition, funding distribution, and leadership [

37,

38]. In the aviation sector, the application of GRRI in recruitment, career development, and metric design has resulted in performance improvements and organizational sustainability [

39]. GRRI has also been shown to transform

education and pedagogy. Studies from global contexts demonstrate that gender-responsive teaching and curriculum design enhance student engagement, particularly among girls, and reduce learning inequalities in STEM and other male-dominated fields. In parallel, UNESCO’s reviews of teacher education policy further show how national systems can institutionalize GRRI principles to reform instructional culture and ensure scalable, gender-equitable education systems [

21,

40,

41,

42]. At the intersection of

digital inclusion and community empowerment, GRRI has proven instrumental in closing gender gaps in access to information and communication technologies. The GEM-ICT4D methodology [

43], for instance, has enabled the gender-sensitive design of digital tools that enhance women’s agencies, participation, and digital literacy [

43]. Meanwhile,

gender-responsive budgeting and finance frameworks show that integrating gender equity and responsiveness into fiscal and investment strategies improves health, education, and employment outcomes across societies [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. In particular, Gender-Lens Investing (GLI) has emerged as a high-performing financial strategy. According to recent reports, a majority of GLI funds meet or exceed financial benchmarks while simultaneously supporting inclusive entrepreneurship and workplace equity [

50,

51]. These dual outcomes make a compelling case for integrating gender not only in social policy but also in economic decision-making.

These empirical examples converge to demonstrate that when research and innovation processes consciously integrate gender perspectives, they consistently yield more inclusive, effective, and context-sensitive outcomes. The cumulative evidence—spanning disciplines, sectors, and geographies—not only justifies the relevance of GRRI, but also strongly compels us to further investigate, refine, and institutionalize GRRI as a critical pathway toward equitable, sustainable, and socially responsible innovation.

However, while sector-specific evidence confirms the benefits of gender-responsive approaches in various domains, there is a growing need to consolidate and expand our understanding of GRRI. Specifically, a deeper exploration is required into its historical and scientific background, conceptual foundations, implementation barriers, mitigation strategies, and cross-sectoral initiatives. Developing GRRI in a systematic manner is essential not only to build on its proven potential but also to support its broader institutionalization across research and innovation systems. To this end, the present study is structured around five Research Questions (RQs) that collectively aim to offer a comprehensive and integrated understanding of GRRI. These RQs are as follows:

[RQ1] What is the historical background and scientific findings of GRRI?

[RQ2] What are the key concepts and relationships that should be included in GRRI?

[RQ3] What are the critical issues and barriers concerning GRRI?

[RQ4] What measures and strategies could be recommended to address GRRI issues and barriers?

[RQ5] What are influential GRRI initiatives in different contexts?

The questions were developed through a review of the literature and expert consultations. RQ1 explores the historical development of GRRI, which helps uncover the systemic roots of gender inequalities and contextualize present-day challenges. Answering enables a deeper appreciation of the evolution of gender frameworks in science and policy. RQ2 identifies the key concepts and relationships that define GRRI, providing a conceptual foundation that supports consistent implementation and communication across disciplines. RQ3 examines the critical barriers that hinder GRRI adoption, offering insight into institutional and operational obstacles. Understanding these barriers is essential for designing meaningful interventions. RQ4 focuses on concrete strategies to overcome these barriers, producing actionable knowledge for stakeholders and decision-makers. Finally, RQ5 highlights influential initiatives across sectors, enabling learning from existing practices and informing the development of context-sensitive, scalable models. Together, addressing these questions supports both the theoretical advancement and practical transformation of R&I systems toward greater inclusiveness and gender equity.

It is important to emphasize that while this study underscores the significance of gender-responsive approaches in R&I, we acknowledge that gender inequality is multifaceted. Categories like “women” and “men” encompass diverse experiences influenced by intersecting factors such as class, race, ethnicity, geography, caste, education, and employment status. We recognize that gender norms and expectations can benefit certain groups of men while disadvantaging others, particularly in contexts where masculinity is associated with physically hazardous work or socioeconomic risks. Similarly, many privileged women positions enjoy labor protections and rights that are not accessible to numerous men in marginalized groups or the global South. These intersectional dimensions are crucial for understanding the complex landscape of gender inequality and must be considered in any truly inclusive GRRI initiative.

This study adopts a Conceptual Expansion Research approach, which involves synthesizing diverse theoretical, disciplinary, and empirical insights to extend and refine an emerging conceptual framework—in this case, GRRI. This is complemented by a Mixed-Methods strategy that integrates narrative and systematic literature reviews with Focused Group Brainstorming involving experts from diverse regions and fields.

The remainder of this paper is organized around the five research questions introduced above.

Section 2 outlines the research methodology, including the mixed-methods approach and expert consultation process that underpin this study.

Section 3 addresses RQ1 by exploring the historical background and scientific findings related to GRRI. This is not presented as general contextual background, but rather as a structured part of the study’s analytical process, developed through a combination of literature synthesis and conceptual mapping.

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6 then respond to RQ2 through RQ5, examining the core concepts, key challenges, strategies, and exemplary initiatives in GRRI. Finally,

Section 7 provides the overall conclusions, discusses contributions, and outlines future directions for both research and practice.

2. Research Methodology

This Conceptual Expansion Research, in order to achieve its goals and address the research questions applied a mixed-methods approach which included the following:

Literature Reviews: Given the transdisciplinary nature of this research, literature reviews were employed as essential methodological tools to establish both the conceptual foundation and the empirical framing of the study. In this research, two complementary review methods were applied:

Narrative Literature Review (NRL): In this study, NRL was employed as a core element of the mixed-methods approach, offering both primary and supportive contributions depending on the research question. Given the interdisciplinary and evolving nature of GRRI, NRL was particularly suitable for capturing conceptual developments, empirical patterns, and policy frameworks across diverse sources. The review played a primary role in addressing RQ1 (historical background) by tracing the evolution of gender-related concepts and their relationship to research and innovation agendas. It served a complementary role in the scientific findings subsection of RQ1, enriching the interpretation of results obtained from the Systematic Literature Review (SLR). For RQ2, NRL supported the identification of key GRRI concepts and relationships that helped define an initial ontological structure. In the case of RQ3 and RQ4, the NRL provided essential introductory knowledge on common issues, barriers, and strategies documented in the literature, which was used to inform and structure the Focused Group Brainstorming sessions. Lastly, for RQ5, the NRL served as the primary method for identifying notable GRRI initiatives across research, industry, and regulatory domains, forming the empirical basis that was subsequently discussed and categorized by the expert group.

The NRL process followed a structured yet interpretive path. First, the review objectives were defined in alignment with the study’s five research questions. A multi-source search strategy was applied, drawing from academic databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, as well as institutional repositories and grey literature platforms including the European Commission, UNESCO, UN Women, and OECD. Search terms included combinations of keywords such as “gender responsive,” “gender-sensitive,” “gender mainstreaming,” “research,” “innovation,” “barriers,” “strategies,” and “initiatives.” Inclusion criteria prioritized sources that addressed GRRI-related concepts and issues, though select historical sources were incorporated to support RQ1. Exclusion criteria involved the removal of duplicates, inaccessible full texts, or works lacking conceptual or empirical relevance. The selected materials were analyzed and organized thematically according to their relevance to each research question, covering historical evolution, conceptual foundations, institutional and structural challenges, proposed strategies, and documented initiatives. Rather than aggregating the findings, the synthesis followed an interpretive approach that enabled the comparison of frameworks, the mapping of themes, and the identification of recurring patterns. The NRL findings directly informed the design of the Focused Group Brainstorming sessions and enriched the overall analytical narrative of the study by ensuring a coherent linkage among theoretical insights, contextual realities, and multi-stakeholder perspectives.

Systematic Literature Review SLR): Unlike the Narrative Literature Review, which offered broader conceptual and historical context, the SLR focused on identifying and analyzing peer-reviewed publications that empirically investigated GRRI. The SLR was conducted to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility, following a structured protocol that included the formulation of a targeted search query, systematic screening of retrieved articles, and classification across multiple analytical dimensions. The purpose of the SLR was to map the current scientific landscape of GRRI, assess how gender responsiveness is operationalized in practice, and extract patterns and trends across sectors such as healthcare, education, and social sciences. A full description of the SLR process, including the search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and synthesis procedure, is provided in

Section 3.2.

Focused Group Brainstorming: To identify the core components of GRRI—such as key issues, systemic barriers, mitigation strategies, and context-specific variations, a Focused Group Brainstorming approach was utilized. This structured method combines the flexibility of brainstorming with the intentionality of guided discussion, facilitating the generation of ideas, solutions, and creative actionable insights within a collaborative setting.

The process commenced with the formulation of focused research questions, selection of diverse participants from academic and non-academic sectors, and establishment of clear guidelines for participation. These steps are not merely procedural; they ensure the validity, inclusivity, and ethical integrity of the research. Without them, the brainstorming process could become disorganized or biased or fail to yield actionable outcomes. They are crucial to maintaining the credibility and utility of the findings, particularly when addressing sensitive topics like gender-responsiveness.

The focused expert group consisted of 16 academic and non-academic experts from 11 countries (Sweden, Portugal, Italy, Romania, Slovenia, Morocco, Brazil, Ecuador, Iran, Moldavia, and Angola), selected through a purposive sampling strategy to ensure the wide coverage of both disciplinary expertise and regional representation. The participant pool included academic researchers, industry professionals, community leaders, and institutional representatives from public and private sectors. These experts represented nine core disciplinary fields: Social Sciences and Humanities, Gender Studies, Economics and Business, Community and Network Studies, Computer Science and Software Engineering, AI and Data Science, Security, Privacy and Trustworthiness, Business Intelligence, and Law and Regulatory Affairs (See

Table 1).

The selection of these specific disciplines reflected the interdisciplinary nature of GRRI, which spans both technical innovation domains and sociopolitical contexts. For example, engineering and computing fields were prioritized due to their traditionally low gender inclusion and high innovation intensity, while gender studies, law, and business ensured the critical coverage of equity frameworks, regulatory considerations, and systemic barriers. The inclusion of multiple stakeholder sectors, academia, civil society, policymaking, and industry was essential to reflect the multi-actor ecosystem required for effective GRRI implementation.

Geographical diversity across Europe, America, Africa, and Asia was equally intentional. It enabled the study to incorporate region-specific experiences with gender inequality, institutional readiness, and cultural norms. This diversity ensured that the resulting framework would not only be conceptually sound but also context-sensitive and globally adaptable, aligned with both theoretical development and the applied implementation of gender-responsive research and innovation (see

Table 1).

Participants engaged in 12 moderated online sessions, focusing on a specific thematic area related to GRRI. The sessions were structured around five predefined thematic clusters, derived from a preliminary literature review and scoping discussions. These included the following: (i) conceptual foundations of GRRI; (ii) gender integration in R&I; (iii) representation and inclusion in the R&I ecosystem; (iv) institutional and structural challenges; (v) strategies and measures for advancing GRRI.

Each session was explicitly designed to contribute to one or more research questions, primarily RQs 2–5. In addressing RQ2, discussions centered on conceptual clarity, relationships among key GRRI elements, and ontological distinctions, which helped elaborate the core concepts and relational structures of the proposed GRRI ontology. For RQ3, the sessions enabled the identification of critical barriers hindering the effective implementation of GRRI. For RQ4, they facilitated the formulation of mitigation strategies, drawing on multidisciplinary perspectives and real-world experiences. For RQ5, expert participants reviewed and refined the set of GRRI initiatives initially identified through the NRL. These initiatives were discussed, categorized, and evaluated in terms of contextual relevance, implementation challenges, and scalability.

Moderators followed semi-structured agendas to facilitate both inductive idea generation and focused thematic exploration within the four predefined clusters. All sessions were conducted via secured online platforms (Zoom) and were audio-recorded with prior informed consent from all participants. Recordings were stored temporarily on encrypted drives in compliance with GDPR and institutional data-protection policies and were permanently deleted following transcription and anonymization. Participants were assured of confidentiality, and all procedures adhered to the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity and relevant ethical guidelines for social research.

Transcription was carried out using a two-stage process: first through automated speech recognition software (Pro-Otter.ai), followed by manual correction and verification to ensure accuracy and clarity. All identifying information was anonymized during transcription to preserve participant confidentiality.

Transcription was completed through a two-step process: initial automated speech recognition (Otter.ai), followed by manual correction for accuracy and anonymization. The resulting transcripts underwent a systematic qualitative analysis using thematic clustering techniques. Open coding was conducted by multiple coders to identify recurring concepts, followed by axial coding to synthesize broader themes. These themes were aligned with RQ3 (barriers) and RQ4 (strategies). Thematic saturation was confirmed when no new categories emerged. Coding consistency was ensured through inter-coder agreement and consensus resolution. NVivo 12 software facilitated coding, thematic queries, and visualization. The outcomes of the brainstorming sessions contributed directly to the analytical structure of the paper:

Findings related to GRRI key concepts and relationships informed

Section 4 (RQ2);

Issues and barriers discussed during the sessions were synthesized in

Section 5, addressing RQ3;

Mitigation strategies generated in subsequent sessions contributed to

Section 5, addressing RQ4;

Initiative classification and contextual insights enriched

Section 6, addressing RQ5, based on the expert discussion and refinement of the initiatives identified via the NRL.

Following the initial synthesis of findings, results were presented anonymously to a

Refinement Group for a second round of critical review and collaborative enhancement. This group included 15 academic and non-academic experts from 10 countries (France, Portugal, Italy, Romania, Iran, England, Ecuador, Pakistan, Belgium, and Spain) and 9 fields (See

Table 1). Their role was to provide constructive feedback, challenge assumptions, and contribute alternative interpretations that would enhance the clarity, depth, and applicability of the preliminary findings. At least two follow-up meetings, either online or in-person, were conducted with each participant during the refinement phase to ensure the transparent integration of feedback.

It is important to emphasize that while the study involved participants from a diverse range of countries, disciplines, and sectors, it does not purport to be globally representative. Instead, it provides a cross-contextual perspective shaped by regional experiences and expert insights, serving as a basis for further context-specific research on GRRI implementation.

3. Historical Background and Scientific Findings

This section explores the historical background and scientific findings of GRRI to address the first research question [RQ1]. It highlights the evolution of the gender concept, from ancient GIE to modern advocacy for GE and equity. The scientific background reveals a growing emphasis on gender-related research, particularly in healthcare and education domains, with varying levels of responsiveness.

Understanding the history of GRRI and the differences between the terms “gender” and “sex,” frequently used interchangeably but having different connotations, is the first step in putting them into practice.

In the ancient world, gender had a different meaning than that used in Social Science and Humanities (SSH) during the past few decades [

52]. In 1955, John Money first used the term “gender” [

53] and considered it something more than a person’s status determined by genitalia: it is self-identification, social categorization, legal categorization, and somatic and behavioral factors [

54,

55]. During the 1970s, feminist scholars used the term gender to distinguish “socially constructed” dimensions of male–female differences (gender) from the “biologically determined” dimensions (sex) [

56]. The usage of the term “gender” in academia has significantly risen since 1950, outpacing the use of “sex” in the SSH [

57].

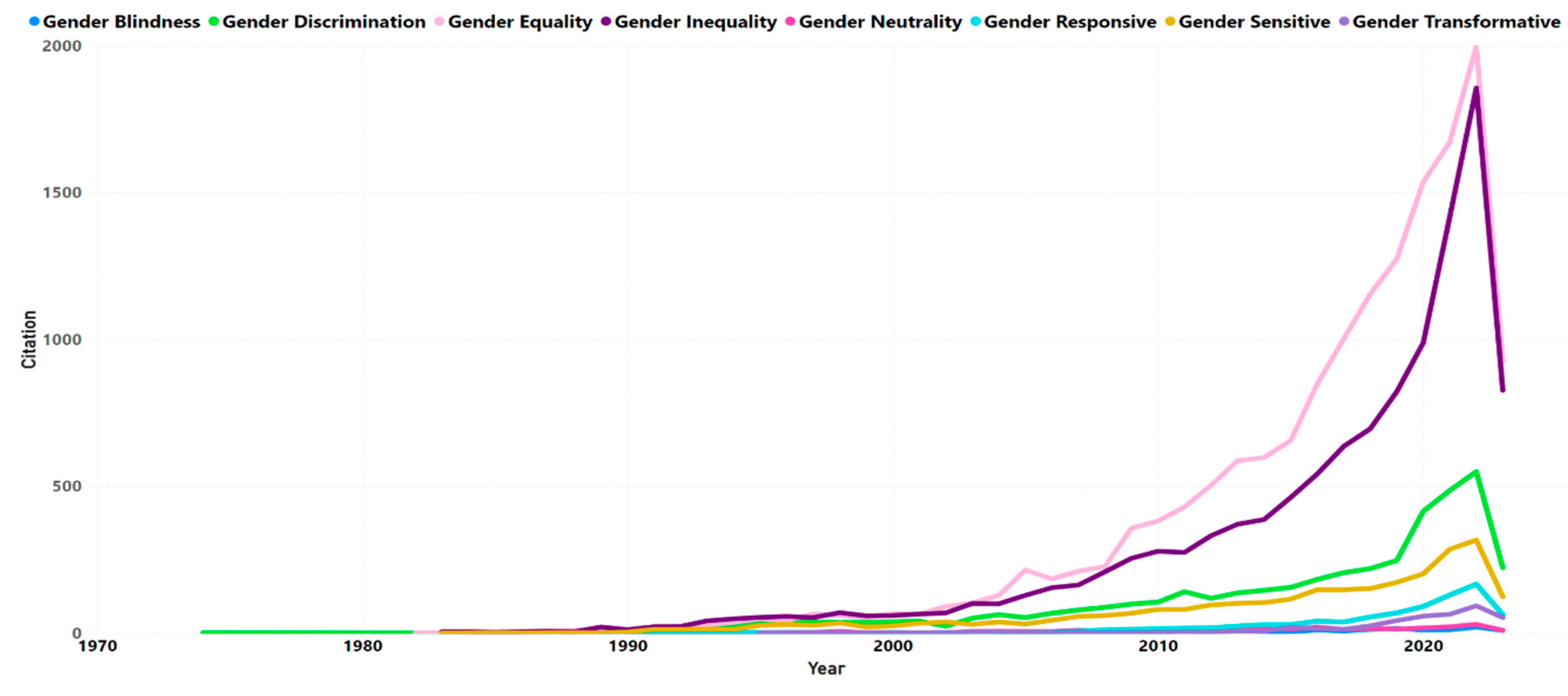

Figure 1 details the analysis of the different gender-related concepts, such as “Gender-Blindness” (GB), “Gender-Neutrality” (GN), “Gender-Discrimination” (GD), “Gender-Equality” (GE), “Gender-Inequality” (GIE), “Gender-Sensitive” (GS), “Gender-Responsive” (GR), and “Gender-Transformation” (GT).

Today, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), when society talks about “gender norms,” it is referring to roles and behaviors associated with women, girls, men, and boys [

58]. In this article, we primarily adopt a binary understanding of gender as this remains the dominant framework in most institutional data collection, policy discussions, and GRRI-related initiatives. This choice also reflects the current stage of the field’s development: as one of the first conceptual explorations of GRRI, our study focuses on domains where terminology, evidence, and institutional mechanisms are most mature. However, we fully acknowledge that this binary model does not capture the full diversity of gender identities. Gender exists on a spectrum, and many individuals identify as non-binary, transgender, or gender-diverse. Future GRRI frameworks must explicitly address this diversity to ensure inclusive and equitable research and innovation practices.

This is not only an ethical imperative but also a practical necessity. In the context of health innovation, for example, applying a GRRI approach that includes gender-diverse populations can reveal significant disparities in access, diagnosis, and treatment. Transgender individuals often encounter systemic barriers, such as non-inclusive healthcare protocols and a lack of gender-sensitive medical training. Integrating their experiences through participatory research, inclusive data categories, and intersectional analysis can lead to more responsive and effective health solutions. GRRI frameworks can thus evolve to reflect the full spectrum of gender identities, enabling research and innovation systems to better serve all members of society.

3.1. Historical Background

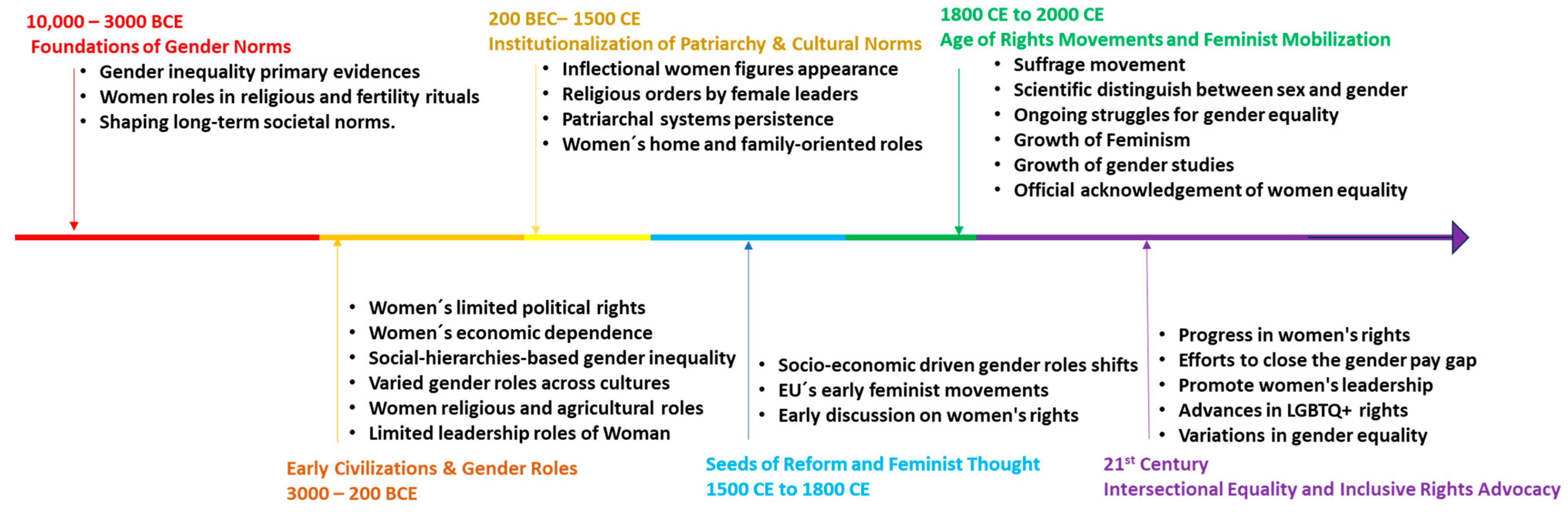

The term “gender inequality” has an ancient foundation and has affected various aspects of life, including politics, education, and social norms. In most modern male-dominated societies, men held the majority of power, while women were often seen as subservient with limited rights and privileges. To trace the evolution of gender,

Figure 2 outlines the concept’s progression from the early Neolithic period (when the Foundations of Gender Norms was created) to the present day.

It was not until the 1970s and 1980s that women’s roles were globally promoted as a means of driving economic development [

71]. However, it was only in the 1990s that the gender perspective began to be explicitly integrated into international development agendas such as the Millennium Development Goals, with GE and GB concepts recognized as serious issues in many developing countries [

72]. Simultaneously, the concept of “Gender Neutrality” emerged in [

73] and gained traction through scholarly movements, creating an environment where individuals are not defined solely by their gender identity. Despite some initial positive outcomes, the term revealed significant consequences, such as overlooking the experiences and needs of individuals with different gender identities, neglecting the impact of gender, erasing the experience of marginalized groups, hindering the efforts toward GE, and undermining the significance of gender identity [

74,

75].

In 1995, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) shifted its focus from a “Women in Development” (WID) [

76] approach to a “Gender and Development” (GAD) approach [

82] aiming to address GIE and promote gender-sensitive policies as emphasized in the “Human Development Report.” The UNDP recognized that gender issues impact both men and women, emphasizing the importance of inclusive policies and programs [

77,

78].

Since then, these approaches have become essential tools for global GE, with the GAD approach serving as the primary international strategy guiding governments in advancing GE across all development sectors, fostering a society where both genders contribute equally [

79].

The GAD strategy and goals have compelled societies, such as the European Union, to acknowledge the significance of GRRI as a crucial factor in various fields [

80]. Therefore, to achieve a more egalitarian society, R&I agendas must prioritize the collection, production, and presentation of data, which encompass men’s and women’s narratives and go beyond gender (in)equality [

81]. These policy advancements align with theoretical progressions and the introduction of the concept of intersectionality. Intersectionality, coined in the late 1980s, describes how different aspects of an individual’s identity, such as gender, race, class, sexuality, and disability, intersect to create systems of inequalities, discrimination, or privilege. It recognizes that individuals may face multiple interconnected forms of inequality or privilege based on their diverse social identities. Intersectionality has since been utilized as a framework for analyzing and comprehending complex social issues and inequalities [

83].

3.2. Scientific Findings

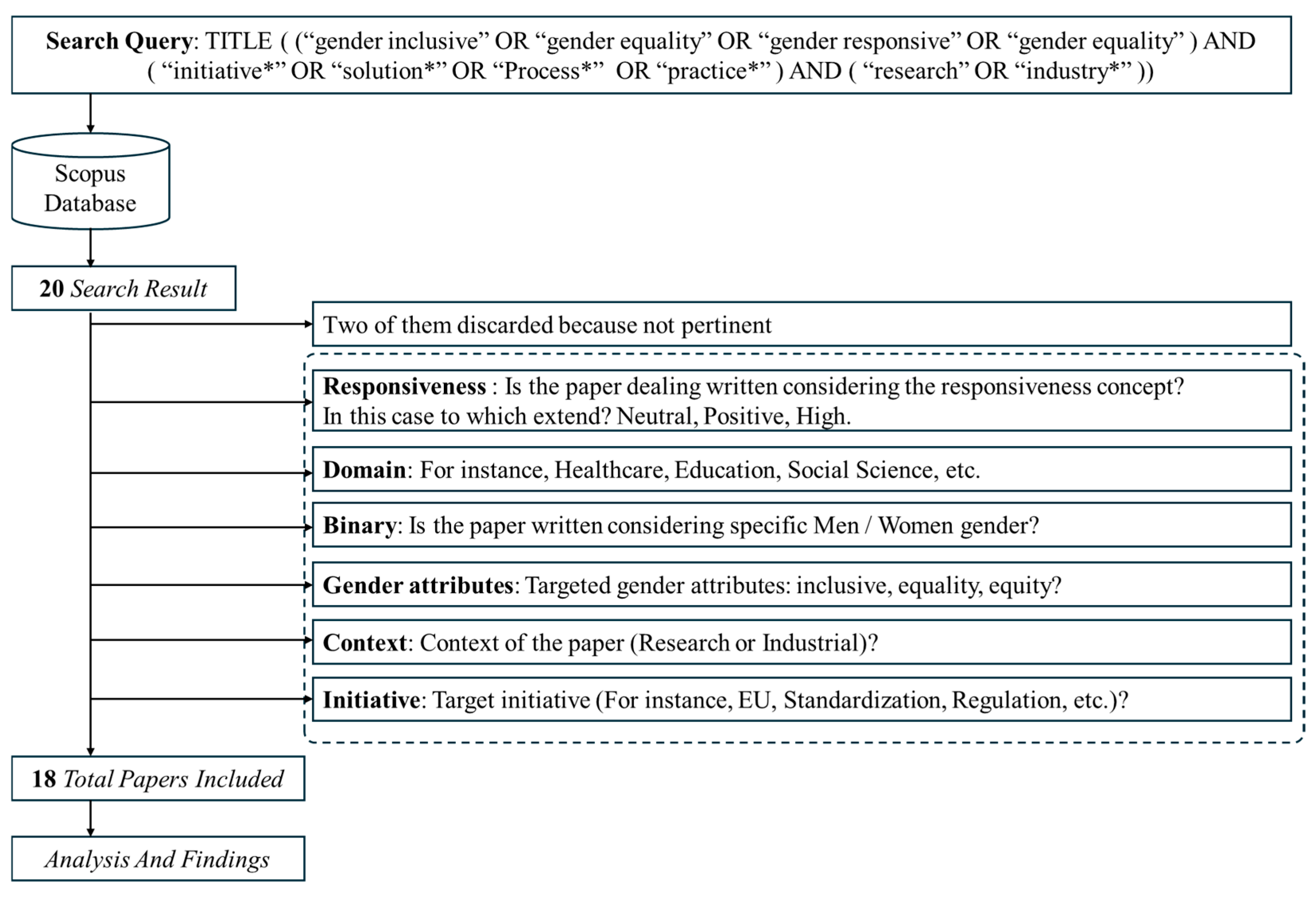

To better analyze the research, literature, and initiatives related to the GRRI, a Systematic Literature Review (see

Figure 3) was conducted using the Scopus database. This platform was chosen for its comprehensive, multidisciplinary indexing, particularly in areas relevant to STEM, social sciences, and policy research. The search was conducted using the following query, limited to the title field to ensure topical focus:

TITLE ((“gender inclusive” OR “gender equality” OR “gender responsive” OR “gender equality”) AND (“initiative*” OR “solution*” OR “Process*” OR “practice*”) AND (“research” OR “industry*”))

This query was designed to identify studies that explicitly focus on gender responsiveness, actionable practices or solutions, and their application within research or industry, the core components of the GRRI framework.

The search was not restricted by language, document type, or geographical filters to maintain openness and inclusivity. The only constraint was the title field, which ensured that selected articles had a focused relevance to GRRI.

The query returned 20 papers, of which 2 were excluded during the screening phase due to a lack of relevance. The 18 selected papers were thoroughly evaluated by examining their titles, abstracts, keywords, and full texts, ensuring that both the conceptual depth and applied relevance were captured. This process enabled us to identify key patterns in how GRRI principles are defined, operationalized, and embedded across different domains.

The papers were then classified across six analytical dimensions to map the scientific discourse around GRRI and its evolution across fields and sectors. These six dimensions include the following:

- 2.

Domain—The application domain (e.g., healthcare, education, social sciences).

- 3.

Binary—Whether the paper used a binary gender lens (woman/man).

- 4.

Gender Attributes—Framing used in terms of inclusiveness, equality, or equity.

- 5.

Context—Whether the paper addressed a research or industry setting.

- 6.

Initiative Type—The type of gender-related initiative (e.g., EU policy, standardization, regulations, etc.).

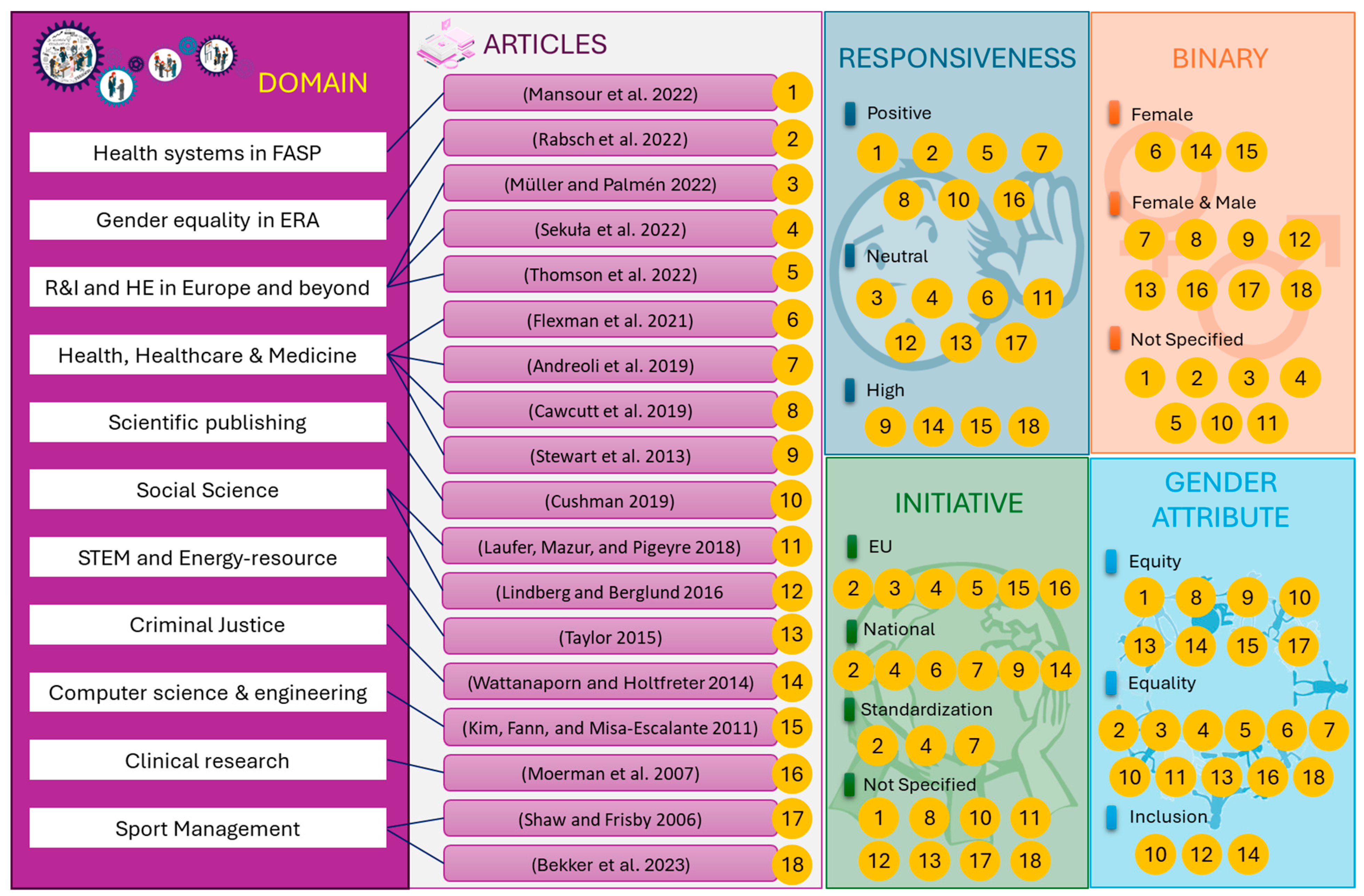

The evaluation result summary is presented in

Figure 4.

The analysis revealed that the research predominantly emphasizes promoting GE and creating an inclusive environment, particularly in healthcare, higher education, R&I, and social sciences. Gender equity solutions are often found in various initiatives, such as regulations/directives, EU policies, national programs, standardization efforts, and communities of practice. The papers employ specific research methods that focusing on both genders, with some specifically addressing the underrepresentation of women in certain fields. While the level of responsiveness varies across the papers, ranging from highly responsive to neutral, they collectively demonstrate a commitment to promoting equity, equality, and justice across different sectors and industries. These results directly support RQ1 by mapping the current scientific landscape of GRRI, identifying which domains and sectors prioritize gender responsiveness and how they operationalize it.

4. Conceptualizations of Gender-Responsive Research and Innovation

This section explores identifying the key concepts and relationships that should be included in GRRI to answer the second research question [RQ2]. These conceptual components emerged from the NRL and Focused Group Brainstorming sessions described in

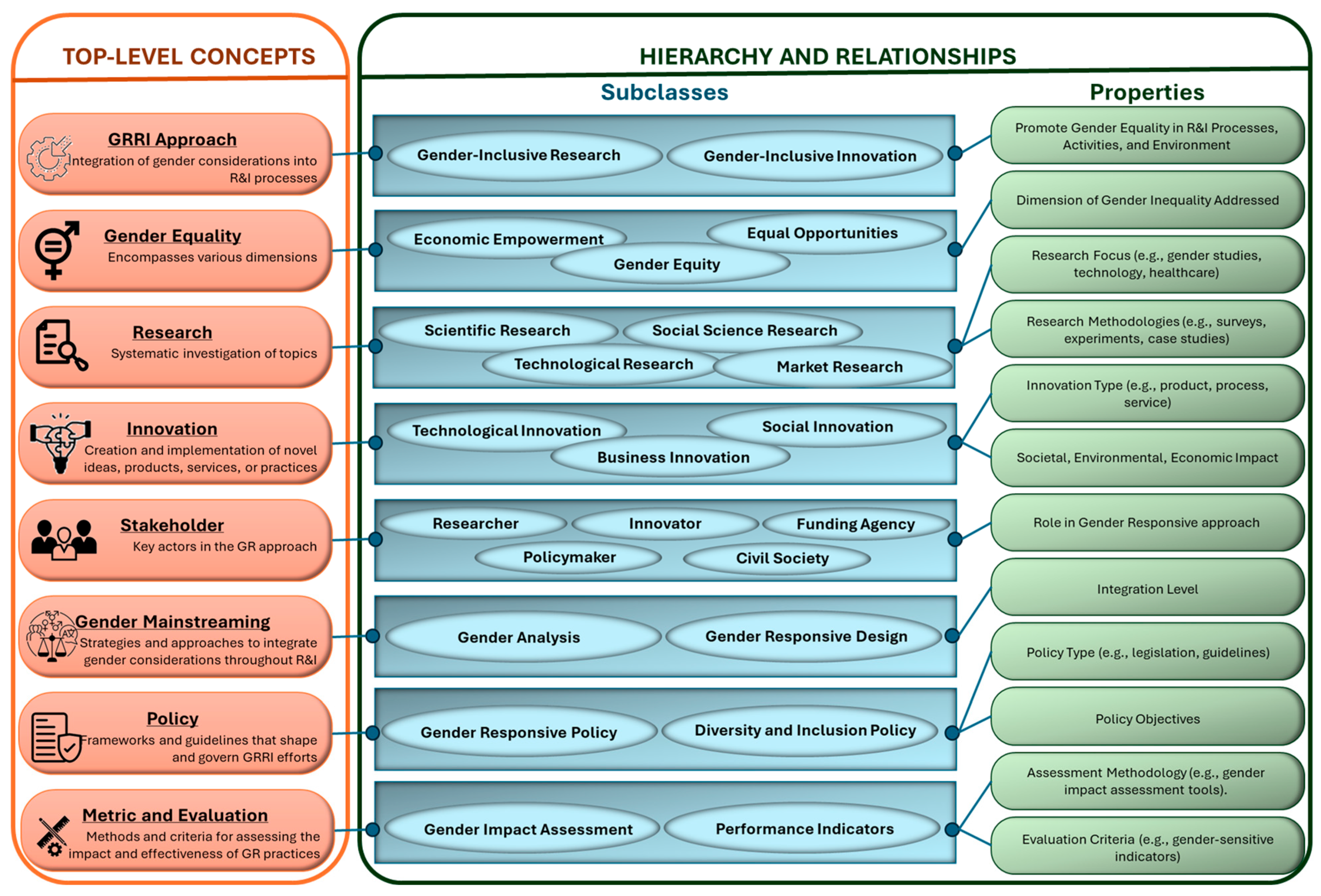

Section 2. It highlights that GRRI encompasses strategies and practices aimed at reducing historical gender biases and inequalities in research, innovation, and development practices, with a focus on addressing gender-based barriers, promoting equality, and leveraging diversity for innovation and socioeconomic progress. It also introduces at least 8 top-level concepts, 23 sub classes, and 12 properties to establish a baseline for GRRI ontology.

GRRI aims to eliminate the historical gender biases and inequalities that persist in research, innovation, development, and their societal impact [

102]. It tackles gender-based barriers, acknowledges gender differences, ensures gender sensitivity in structure and systems, promotes gender parity as a broader strategy for advancing GE, and works toward closing gaps and eliminating gender-based discrimination [

103] in the R&I domain. GRRI employs a multidimensional approach that includes gender analysis, inclusion, and sensitivity, fostering innovation and effective problem-solving by embracing diverse perspectives as a strength. Furthermore, GRRI aligns with international initiatives for GE and contributes to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and serves as a catalyst for promoting socioeconomic development through equitable and inclusive scientific achievements. It is poised to transform the landscape of science and innovation, paving the way for a more equitable and sustainable future for all, as researchers, policymakers, and institutions increasingly recognize the importance of GRRI.

Figure 5 outlines a baseline for a GRRI ontology, detailing top-level concepts, their hierarchy, relationships, subclasses, and properties. These were initially proposed by the research-focused group in brainstorming sessions and refined and enhanced by a refinement group.

5. Issues and Barriers

This section explores the identification of GRRI issues and barriers [RQ3] and suggests measures and strategies to combat and mitigate them [RQ4] to answer the second and third research questions. These challenges and the corresponding mitigation strategies were identified through a combination of NRL and Focused Group Brainstorming sessions, as described in

Section 2. Insights from experts were thematically clustered and coded to support the synthesis presented here, directly addressing RQ3 and RQ4. GRRI faces several significant challenges, including the lack of a gender perspective in R&I, male-dominated fields, gender bias, limited participation of women, insufficient funding, lack of coordination, limited research capacity, lack of gender-disaggregated data, limited understanding of gender dynamics, and institutional barriers. These obstacles hinder the development of GR techniques and solutions, perpetuate gender inequalities, and restrict the impact of GRRI. It is also important to recognize that these barriers may manifest differently depending on cultural, institutional, and regional contexts. Variations between traditional and Western societies, for instance, influence how gender roles, expectations, and institutional support structures shape both challenges and opportunities for implementing GRRI. To tackle these issues and barriers, active promotion of gender awareness, fostering inclusivity, encouraging diversity in R&I teams, investing in capacity-building, and advocating for GR policies and funding systems are crucial. Collaboration, coordination, and data collection improvements are vital for effective GRRI. Addressing these issues and implementing measures can make GRRI more inclusive, equitable, and effective in advancing GE and social progress.

GRRI faces several issues and barriers that can hinder progress and impact. In this study, through mixed-methods, Focused Group Brainstorming and considering the literature, important issues and barriers of executing a GRRI have been identified.

5.1. Lack of Gender Perspective

Researchers and innovators may not always consider the gender dimension in their work, leading to Gender-Blind (GB) or Gender-Neutral (GN) approaches. A GB or GN approach in R&I refers to an approach that does not explicitly take gender into account as a significant factor in the design, implementation, and outcomes of studies and innovations [

104]. While the goal is to treat all individuals equally, regardless of gender, it assumes that gender does not play a significant role in shaping experiences, needs, or outcomes [

105].

While a GB or GN approach may be well-intentioned, it has limitations as it overlooks gender as a crucial social condition that influences lives. Failing to acknowledge gender differences can perpetuate inequalities and overlook the unique challenges faced by women, men, and non-binary individuals [

106]. Instead, R&I should consider how gender intersects with race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and sexuality through a GR approach. This approach aims to address biases, prejudices, and inequities, recognizing gender as a key component of identity. By acknowledging diverse gender needs, a responsive strategy seeks to advance inclusivity, equality, and equity.

5.2. Male-Dominated Fields

The underrepresentation of women and marginalized gender groups in R&I constrains diverse perspectives, resulting in a focus on men’s goals and viewpoints while overlooking the needs and challenges faced by women and other genders [

107]. Due to the male-dominated culture and power dynamics in R&I, questioning traditional norms and practices hinders the development of GR techniques and solutions that cater to the unique needs and ambitions of all genders [

108]. Additionally, the lack of women in leadership and decision-making roles exacerbates these challenges, leading to policies and practices that do not adequately address the gendered aspects of R&I [

109,

110].

To address these issues, proactive efforts are necessary to promote gender diversity and inclusivity within R&I. Initiatives should prioritize improving representation, challenging prejudice and stereotypes, providing mentorship and support for women researchers, and creating an inclusive and equitable work environment. By eliminating these barriers, R&I can become more inclusive and GR ultimately leading to more meaningful and equitable outcomes.

5.3. Gender Bias

Gender bias refers to the systematic and unfair treatment of individuals based on their gender or how they are portrayed. It can manifest through stereotypes, prejudices, and discrimination, leading to inequalities and hindering the process in GR approaches in R&I [

111]. Gender bias can affect various stages of the R&I process. For example, gender biases may influence the research design by overlooking gender-specific variables or neglecting the unique requirements and experiences of different genders [

112]. Biased data collection and analysis can result in skewed findings that ignore gender differences or reinforce existing biases. Biases in research interpretation and dissemination can contribute to GIE and impede the adoption of GR practices.

Efforts to address gender bias require combating prejudiced attitudes and behaviors. These include creating inclusive and equitable research environments, promoting gender awareness and education, and implementing mechanisms to ensure diversity and representation across all levels of R&I. Advocating for laws, regulations, and funding systems that support GE is essential to combat bias and promote more inclusive and impactful R&I outcomes [

113,

114]. By addressing gender bias and promoting GE, R&I can become more inclusive, equitable, and responsive to the diverse needs and experiences of all genders.

5.4. Limited Participation of Women

The limited participation of women is a critical issue for GRRI. The historically low representation of women in R&I has hindered the development of GR techniques. Limited women’s participation and representation obstruct the formulation of inclusive research agendas, restrict the use of diverse viewpoints, and compromise the reliability and efficacy of solutions [

115].

Several variables contribute to the low representation of women in R&I, including institutionalized biases, gender preconceptions, limited mentorship and networking opportunities, gender-based discrimination, and challenges balancing work and family obligations. These issues not only impede women’s access to resources, money, and leadership roles but also contribute to an adversarial climate [

116]. Encouraging and supporting the significant involvement of women in R&I is essential to address this problem. This involves implementing programs that facilitate women’s entry and progress across sectors, such as mentorship initiatives, scholarships, and targeted funding opportunities. Additionally, efforts should be made to dispel gender stereotypes, provide equitable opportunities for education and professional advancement, and foster inclusive work cultures that value and respect diverse viewpoints [

117,

118].

Promoting GR approaches to address the unique needs, challenges, and aspirations of all genders can be achieved by enhancing the engagement and representation of women in R&I. This fosters a more diverse and equitable research environment, encouraging innovative solutions to bridge gender gaps and promote social change.

5.5. Insufficient Funding

For conducting significant research that addresses gender-specific issues and advances GE, sufficient financial resources are essential. However, compared to other fields of study, GRRI frequently receives insufficient financing, which limits their potential scope, scale, and impact [

119,

120]. Insufficient funding hampers in-depth research, the collection of gender-disaggregated data, and innovative solutions. Resources for educating researchers in GR methods are limited, and a lack of funds may discourage pursuing gender-focused studies due to challenges in securing funding for such initiatives [

121,

122].

Recognizing the importance of GRRI in advancing GE and socioeconomic progress is vital to tackling inadequate funding. Efforts are needed to allocate sufficient funds specifically for gender-focused studies and projects, including prioritized research, innovation, and gender-aware capacity-building initiatives. Increased funding enables scholars to conduct thorough studies, gather robust data, and formulate effective plans for addressing gender gaps and promoting equality. Promoting GR funding policies and fostering partnerships among researchers, funding organizations, and policymakers can ensure continuous and ample support for GRRI. Investing in GR techniques contributes to developing insightful knowledge and creative solutions for creating a more inclusive and equitable society [

123].

5.6. Lack of Coordination

In GRRI, insufficient coordination and collaboration among involved parties pose a significant challenge. Effective strategies, knowledge exchange, and the adoption of GR techniques require collaboration among researchers, policymakers, institutions, civil society organizations, and other stakeholders [

29].

Without adequate coordination, utilizing diverse knowledge and resources becomes challenging. Working in silos can result in redundant efforts and missed synergies, hindering the impact and progress of GRRI due to fragmented approaches [

124].

Effective coordination and teamwork promote the sharing of creative ideas, lessons, and best practices. It ensures multidisciplinary cooperation, incorporating diverse viewpoints into R&I processes. Collaboration enhances the efficiency and efficacy of GR activities by aligning priorities, sharing resources, and avoiding duplication. Building platforms and coordination mechanisms is crucial, to encourage collaborations among academics, decision-makers, institutions, and civil society groups involved in GRRI. Such collaborations facilitate information sharing, joint project organization, and the collective achievement of objectives. Developing networks and platforms for information sharing, along with promoting interdisciplinary methods, helps bridge gaps and enhance coordination [

125,

126].

Enhancing coordination and collaboration can increase the overall impact of GRRI, promote information sharing, and lead to more comprehensive and efficient solutions for addressing gender gaps and advancing GE.

5.7. Lack of Research Capacity

Conducting GRRI necessitates a deep understanding of gender dynamics, intersectionality, and inclusive frameworks. The limited research capacity in this area may hinder researchers from effectively incorporating gender factors, leading to the omission of crucial elements, biases in data collection and analysis, and the inability to establish culturally appropriate and effective solutions to gender inequities [

127].

Funding capacity-building projects is crucial for providing researchers with the necessary information and competencies for GRRI. This includes programs, workshops, and materials covering gender concepts, approaches, and best practices. Equipping researchers with these tools ensures the relevance and success of their R&I activities through improved comprehension and the incorporation of gender analysis. Collaboration among research institutions, decision-makers, and gender specialists facilitates mentorship and knowledge-sharing. Establishing networks and communities dedicated to GRRI provides a forum for knowledge exchange, support, and encouragement. Enhancing research capability in GR methodologies promotes an inclusive R&I culture, resulting in more substantial and significant outcomes addressing gender inequities, advancing equality, and society [

128,

129].

5.8. Lack of Gender-Disaggregated Data

Gender-disaggregated data (GDD) refers to data that are gathered and examined separately for men, women, and other gender groupings. It is crucial for understanding and addressing challenges that are specific to each gender, detecting gender inequities, and developing interventions and policies that are evidence-based [

130,

131]. Without gender-disaggregated data, it is difficult to fully grasp the unique experiences, needs, and issues faced by different genders. This can hinder efforts to identify and address gender inequalities and may result in generic solutions that overlook gender dynamics nuances. Various factors, such as inadequate data systems, limited data collection efforts, and the underrepresentation of women and marginalized genders, contribute to the lack of gender-disaggregated data. Cultural barriers, privacy concerns, and the misconception that gender is universally applicable in all situations can also play a role [

132].

Efforts should be directed towards enhancing data collection processes by incorporating gender-disaggregated variables. This may involve integrating gender considerations into study protocols, survey questions, and data collection tools. Collaboration among researchers, decision-makers, and data organizations is essential for bridging the data gap. They can work together to establish data systems that capture gender-specific information and promote the inclusion of gender-disaggregated data in research initiatives. Collaborative endeavors ensure that gender-responsive research, interventions, and policies are grounded in comprehensive and accurate data.

5.9. Limited Understanding of Gender Dynamics

Gender dynamics refer to how social, cultural, and power systems shape people’s experiences, roles, and interactions based on gender. Developing effective GR techniques requires a thorough understanding of gender dynamics. Without this understanding, there is a risk of the oversimplification or misinterpretation of gender issues, which can perpetuate biases and inequalities. The limited comprehension of gender dynamics may result from biases, stereotypes, and assumptions about gender roles and norms, as well as a lack of diverse perspectives and voices in R&I processes, inadequate research, and insufficient training. To address this issue, funding should be allocated to projects that enhance our understanding of gender dynamics and build capabilities. This includes promoting multidisciplinary approaches involving gender studies, social sciences, and relevant disciplines. It is essential to foster partnerships with experts in gender analysis and mainstreaming. Promoting diversity and inclusivity within R&I teams ensures a broader range of perspectives. This involves collaborating with underrepresented gender groups, considering intersectionality, and amplifying their voices throughout the R&I processes [

133,

134]. By increasing our understanding of gender dynamics, GRRI can better address the unique demands, concerns, and aspirations of all genders. This understanding can inform the development of more just and equitable policies, interventions, and solutions that promote social progress and GE.

5.10. Institutional Issues and Barriers

A fundamental institutional impediment is the lack of policies, processes, and funding in R&I institutions to promote GRRI. Without the necessary frameworks and tools in place, it is challenging to incorporate gender considerations effectively into R&I practices. Institutional barriers can manifest in various ways. Firstly, the absence of explicit expectations and standards for gender inclusion in R&I may stem from institutions lacking GR policies and procedures, resulting in inadequate prioritization and accountability. Secondly, the implementation of GRRI may encounter obstacles due to a lack of supportive policies and practices. For example, there may be no established procedures for collecting gender-specific data, conducting gender analyses, or forming diverse and inclusive research teams. Thirdly, insufficient resource allocation can impede GR measures. Progress in this area may be hampered by a lack of funding, limited access to training programs, and dedicated personnel or units for GRRI [

135,

136].

R&I organizations need to establish GR policies that integrate gender considerations into research funding standards, moral principles, and evaluation systems. Providing adequate funding for capacity-building, mentoring, and training initiatives to enhance researchers’ understanding of GR methodologies is crucial. Cultivating a supportive and inclusive institutional culture involves implementing gender mainstreaming, promoting diversity and inclusivity in research teams, and offering mentorship and networking opportunities for underrepresented gender researchers. Addressing these institutional challenges creates a conductive environment for GRRI actions, leading to more inclusive, equitable, and impactful outcomes that address gender inequities and advance GE.

6. Initiatives in Different Contexts

This section discusses the key initiatives related to GRRI in different contexts, addressing the fifth Research Question [RQ5]. The initiatives presented here were initially gathered through the NLR and then reviewed, refined, and categorized in collaboration with experts during the Focused Group Brainstorming sessions described in

Section 2. These initiatives encompass research, industry, and regulation, with a focus on enhancing representation, fostering inclusive workplaces, and promoting GE. These efforts are crucial in advancing GRRI and achieving GE in various sectors.

To improve GRRI and address identified issues and barriers, this section explores influential initiatives in diverse contexts, including research, industry, and regulatory settings. Each context presents unique reflection of distinct priorities, challenges, and cultural or institutional dynamics. The analysis underscores how initiatives are shaped by and responsive to their specific implementation environments.

6.1. Research Initiatives

In academic and research contexts, GRRI initiatives are shaped by institutional structures, disciplinary cultures, and funding mechanisms. These environments often encounter challenges related to representation, advancement, and leadership for underrepresented groups. As highlighted in [

137,

138], current initiatives aim to address these barriers and enhance gender responsiveness across educational, professional, and institutional domains. Key initiatives in the research context focus on the following areas:

- 1.

Utilizing technical and vocational education and training [

139] to enhance formal and informal education and training processes. Cultural improvement can enable greater inclusivity and equal access for women in internship and career programs. As highlighted in [

140] this involves the following:

Providing facilities to address the “motherhood penalty” by improving living arrangements, removing institutional barriers, and enhancing the general wellbeing [

141].

Enhancing grants and funding for women researchers to address the imbalance in the success rate between men and women [

140,

142].

Improving leadership opportunities by supporting women’s promotion and ensuring equal career progression in academia [

138,

143].

- 2.

Facilitating the higher education-to-work transition, i.e., the educational process that starts in the years of higher education and ends when graduates have found adequate employment [

144]. Women students need to acquire the necessary competencies for promoting themselves in the workplace and enforcing the required GR [

138]. Particularly, the process should promote the establishment of groups, the distribution of informational events, activities and promotions, collection and publication of statistics and similar experiences, and the use of suitable sensitive language. Additionally, the process should be supported by facilities for improving networking and exchanges, platforms for discussion and cooperation with women’s groups, and the creation of databases on women scientists [

145].

- 3.

Promoting women’s participation, organization, and chairing in conferences, general events and publications. Some studies stated [

146] that there could be a strong positive correlation between women authorship and the likelihood of higher gender involvement in research and industries, as well as a better social impact and responsiveness. Currently, some scientific fields (including nursing, education, and social work) showed higher rates of publication by women authors compared to others (such as engineering, high-energy physics, mathematics, computer science, philosophy, and economics) [

147].

- 4.

Improving access to professional development and networking opportunities [

148], especially in cases where women face restrictions on traveling alone [

149].

These initiatives demonstrate how the research context, with its hierarchical structures, academic traditions, and often male-dominated cultures, influences the design and implementation of GRRI strategies. They reveal the importance of adapting initiatives to the institutional realities and disciplinary practices of academia to ensure effective and lasting change.

6.2. Industrial Initiatives

In industrial settings, GRRI initiatives are shaped by organizational cultures, market-driven priorities, and varying levels of regulatory pressure. Unlike the research context, where structural and institutional barriers are prevalent, the industrial context places more on workforce diversity, inclusive practices, and leadership equity. Companies and organizations are increasingly recognizing the importance of gender-responsive practices not only for equity but also as a driver of innovation, market competitiveness, and corporate reputation. These efforts aim to create environments where all individuals, regardless of gender, feel valued and respected [

150]. While some strategies overlap with those used in academia, the industrial domain requires initiatives tailored to dynamic, profit-oriented environments. Key initiatives in this context include the following:

Diversifying the workforce through targeted recruitment and retention strategies, unconscious bias training, and mentoring programs to attract and retain a diverse workforce [

151]. This practice ensures that the recruited workforce represents the diversity of the community served by a given company or organization [

152].

Promoting an inclusive culture to create a workplace where individuals of all genders feel valued, respected, and supported [

153]. This can be achieved through initiatives such as employee resource groups [

154], cultural sensitivity training [

155], and creating a safe space for underrepresented groups to share their experiences and perspectives. Clear policies and procedures should also be established to address discrimination and harassment based on gender identity.

Providing accommodation for people with disabilities by offering accessibility training and accommodations, and ensuring that products, services, and facilities are accessible to them [

156].

Advancing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) in leadership refers to the efforts of companies and organizations to ensure that leadership roles are occupied by a diverse group of individuals, reflecting the diverse backgrounds and perspectives of the company’s workforce and customer base [

157]. This can be achieved by implementing initiatives such as setting diversity and inclusion goals, promoting diverse candidates for leadership roles, and providing leadership development programs for underrepresented groups.

These initiatives are shaped by organizational structures, internal policy cultures, and external regulatory and social expectations. Industrial GRRI efforts are often driven by stakeholder demand, brand reputation concerns, or compliance with national and international frameworks. Therefore, they need to be context-responsive and strategically aligned with business objectives to be effectively implemented and sustained.

6.3. Regulatory Initiatives

Regulatory initiatives play a crucial role in implementing GRRI at scale, by shaping practices in both research and industry through top-down policy guidance, funding conditions, and legal frameworks. These initiatives are typically designed and implemented by governmental bodies, international organizations, or transnational institutions like the European Union and the United Nations. Their influence is particularly visible in setting standards for gender equality, promoting institutional accountability, and driving systemic change across various sectors.

In recent years, several high-impact regulatory initiatives have emerged, particularly in the European context, aimed at fostering a gender-inclusive culture in academia, industry, and innovation ecosystems. Some notable examples include the following:

The EU

Gender Equality Strategy, which aims to achieve GE and empower women and girls while combating discrimination based on sex, including gender-based violence [

80].

The EU

European Pact for Gender Equality, which aims to achieve a better work–life balance and promote GE and the empowerment of women in the workplace [

158].

The

Gender Pay Gap initiative, which aims to close the pay gap between men and women in the EU [

159].

The

Women on Boards initiative, which aims to increase the representation of women on corporate boards in the EU [

160].

The

Gender Equality and Diversity program in the European Banking Authority (EBA), which aims to create an inclusive workplace that values diversity and promotes GE [

161].

UNESCO’s

SAGA initiative, which promotes GE in STEM fields by increasing the representation of women through advocacy, research, and capacity-building [

162].

The

GenderInSITE, a global initiative promoting GE in science, innovation, technology, and engineering by integrating gender analysis into R&I practices [

163].

The

Athena SWAN program, launched by the UK’s Equality Challenge Unit, promoting GE in higher education and research, by recognizing institutions and departments committed to advancing GE through their policies, practices, and initiatives [

164].

The

HeForShe is a global effort launched by the United Nations to promote GE and engage men and boys as advocates for change. The initiative includes a focus on GE in STEM fields and encourages men and boys to take action to promote GE in their workplaces and communities [

165].

The

ETHNA System has the main goal of implementing and enforcing an internal management and procedural system of the Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) within six European Higher Education, Funding and Research Centres (HEFRC). The objectives are the development of Ethical Governance of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) where GE, Open Science, and Citizens’ Engagement and Integrity Research (ethics) dimensions are considered in a multi-stakeholder governance context [

166].

These initiatives demonstrate how regulatory frameworks differ from research- and industry-driven efforts. Unlike bottom-up or institution-specific initiatives, regulatory programs often set cross-sectoral standards, mandate compliance, and incentivize systemic transformation. Their impact is influenced by geopolitical contexts. For example, EU-level strategies reflecting European values and legislative cultures, while global initiatives like HeForShe and GenderInSITE adapt to regional realities.

As GRRI implementation progresses, regulatory efforts provide the institutional foundation for change, but their success hinges on adaptation, enforcement, and interpretation within national, institutional, and cultural contexts.

7. Conclusions and Future Works

The consequences of non-GRRI processes include gender-based violence, health disparities, workplace inequalities, limited access to finance, and education gaps. Utilizing the GRRI approach could rectify these disparities and create a more equitable inclusive society. However, to enhance GRRI, it is necessary to investigate its historical background and scientific findings [RQ1], understand critical concepts and their relationships better [RQ2], identify and determine the issue and barriers that can hinder progress and impact [RQ3], propose measures and strategies to mitigate these issues and barriers [RQ4], and identify existing or planned initiative in different contexts [RQ5].

In addressing [RQ1], our exploration traces the evolution of GRRI and its relevant concepts, shedding light on its origins and development from a theoretical concept to a concrete framework. By delving into this historical and scientific journey, we have established a solid foundation for a better understanding of the nature of GRRI and upcoming research questions, emphasizing the importance of its historical background and scientific findings.

Regarding RQ2, we outlined fundamental top-level concepts, hierarchical structures, and their intricate relationships to create a preliminary ontology. This not only meets the demand for a comprehensive and structured understanding of GRRI but also serves as a practical tool for navigating its complexities. This marks a significant step toward integrating GR principles into the R&I landscape, shaping a more inclusive and responsible future.

To address RQ3 and RQ4, we identified ten primary issues and barriers through a mixed-methods approach and proposed proactive measures and strategies to confront and mitigate their adverse effects. These include the absence of gender respect, male-dominated fields, gender bias, limited participation of women, insufficient funding, lack of coordination, inadequate research capacity, absence of gender-disaggregated data, limited understanding of gender dynamics, and institutional obstacles.

Moreover, in response to RQ5, we highlighted 18 noteworthy initiatives across research, industrial, and regulatory contexts. These initiatives contribute to addressing and resolving identified issues and barriers, paving the way for a more inclusive and equitable society.

This research offers promise for scientific and non-scientific domains. In academia, it provides a foundation for the further exploration of GRRI, creating knowledge and awareness. Policymakers can shape policies promoting GR practices, businesses can enhance product development, educational institutions can integrate findings into GR curricula, and civil society organizations can leverage insights for advocacy and societal change.

It is important to note that the issues, barriers, and initiatives discussed in this study are drawn from selected countries and disciplinary areas. Therefore, the findings are not universally prescriptive but serve as a foundation for a further, context-specific exploration of GRRI frameworks adapted to local cultural, institutional, and socio-economic dynamics.

Future research should aim to assess the long-term impact of GR initiatives, explore the intersectionality of GR with other aspects of diversity, investigate global perspectives on gender disparities, explore the evolving role of GR in emerging fields, and evaluate the effectiveness of policies based on this research. These avenues of inquiry will further enrich our understanding of GRRI and its multifaceted implications. Moreover, future research should prioritize context-specific investigations of GRRI implementation across diverse cultural, institutional, economic, and geopolitical settings. Comparative and sector-specific studies are essential for identifying localized challenges, adaptations, and best practices, thereby complementing the cross-contextual insights presented in this study. In addition, future studies should move beyond binary gender classifications (i.e., men and women) to account for the socially and structurally differentiated experiences both within and beyond traditional gender categories. An intersectional lens is crucial for building inclusive, context-sensitive innovation ecosystems that genuinely leave no one behind. This includes recognizing and addressing the specific barriers, needs, and contributions of non-binary, transgender, and gender-diverse individuals, whose perspectives remain underrepresented in current GRRI research and implementation. Advancing the field will require not only expanding data structures and analytical tools to capture this diversity but also developing participatory research practices that embed these voices throughout the R&I process. Finally, while this study has presented a set of empirical illustrations from multiple sectors that demonstrate how GRRI has been applied in practice and what impacts it can yield, future research must build upon these foundations. Deeper, institutional-level investigations are needed to examine how GRRI strategies are operationalized in everyday settings. This includes studying how cross-sectoral collaborations among academia, policymakers, and civil society are formed and sustained and how gender-equity principles are embedded into organizational routines, governance models, and evaluation systems. Such empirical inquiries are essential for identifying the enablers, constraints, and practical dynamics of implementing GRRI and for informing the development of more actionable, context-sensitive models of gender-responsive innovation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N.-H., E.M., M.G., F.F., A.I.O., A.H.L., A.F.E., J.B., S.K., N.B., S.S., S.D. and L.A.; Methodology, S.N.-H., E.M., M.G., F.F., A.I.O., A.H.L., A.F.E., and S.D.; Software, S.N.-H., and S.K.; Validation: S.N.-H., E.M., M.G., F.F., A.I.O., A.H.L., A.F.E., J.B., and S.K.; Formal analysis, S.N.-H., E.M., M.G., F.F., A.I.O., A.F.E., S.K., and S.D.; Investigation, S.N.-H., E.M., M.G., F.F., A.I.O., A.H.L., O.M., N.B., S.S., L.A., and S.D.; Resources, S.N.-H., E.M., M.G., F.F., A.I.O., O.M., J.B., S.K., and S.D.; Data curation, S.N.-H., E.M., F.F., A.I.O., S.K., and S.D.; Writing—original draft, S.N.-H., E.M., M.G., F.F., A.I.O., and S.D.; Writing—review & editing, S.N.-H., E.M., M.G., F.F., A.I.O., A.H.L., A.F.E., O.M., J.B., S.K., N.B., S.S., L.A., and S.D.; Visualization, S.N.-H., E.M., F.F. and A.I.O.; Supervision, S.N.-H.; Project administration, S.N.-H.; Funding acquisition, S.N.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly supported by the Portuguese FCT program, Centre of Technology and Systems (CTS) CTS/00066, Nova University Lisbon’s PhD program of Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, and the project SER-ICS (PE00000014) under the NRRP MUR program funded by the EU—NGEU.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of CTS-UNINOVA Ethics Committee (protocol code 2022101201 and 21 October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to data privacy and confidentiality agreements established between the research team and the participants, as well as ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Oliviu Matei and Laura Andreica were employed by the company Holisun SRL. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Conceição, P.; Hall, J.; Hsu, Y.C.; Jahic, A.; Kovacevic, M.; Mukhopadhyay, T.; Ortubia, A.; Rivera, C.; Tapia, H. 2020 Human Development Perspective: Tackling Social Norms—A Game Changer for Gender Inequalities; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/hdperspectivesgsni.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Cheryan, S.; Markus, H.R. Masculine Defaults: Identifying and Mitigating Hidden Cultural Biases. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 127, 1022–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperber, S.; Täuber, S.; Post, C.; Barzantny, C. Gender Data Gap and Its Impact on Management Science—Reflections from a European Perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2022, 41, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Women, Business and the Law 2023; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-4648-1944-5. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/b60c615b-09e7-46e4-84c1-bd5f4ab88903/content (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- UN WOMEN. Equal Pay for Work of Equal Value. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/csw61/equal-pay (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- World Bank. Women, Business and the Law 2022; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4648-1817-2. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstreams/12a9ec51-e881-56d0-b115-9b60478be2dc/download (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- UNESCO. Women in Science: Fact Sheet No. 55 June 2019 FS/2019/SCI/55; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs55-women-in-science-2019-en.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- van der Linden, N.; Browning, E.; Roberge, G. Progress toward Gender Equality in Research and Innovation-2024 Review; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Proportion of Seats Held by Women in National Parliament (%). 2016. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SG.GEN.PARL.ZS (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- UN Women. Facts and Figures: Women’s Leadership and Political Participation. 2025. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/articles/facts-and-figures/facts-and-figures-womens-leadership-and-political-participation#_edn1 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- WIPO. Gender Gap in Innovation Closing, but Progress Is Slow. Available online: https://wipo.int/women-and-ip/en/news/2021/news_0002.html (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- OMCI. Women and Innovation; 2024 Report; Women, Science, and Innovation Observatory (OMCI); Spain. 2024. Available online: https://www.ciencia.gob.es/InfoGeneralPortal/documento/4544fda9-be97-40cd-bb80-131b769b8003 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Zippia. Product Designer Demographics and Statistics in the US. 2022. Available online: https://zippia.com/product-designer-jobs/demographics/ (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Korellis Reuther, K. Shrink It and Pink It: Gender Bias in Product Design. 2024. Available online: https://www.sir.advancedleadership.harvard.edu/articles/shrink-it-and-pink-it-gender-bias-product-design (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- UFHealth Explaining the Life Expectancy Gap Between Men and Women. Available online: https://online.aging.ufl.edu/2024/03/13/explaining-the-life-expectancy-gap-between-men-and-women/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).