Abstract

As sustainability becomes increasingly central to organizational strategy, social economy organizations (SEOs) are rethinking their business models. This study employs stakeholder analysis using the value mapping (VM) tool developed by Short, Rana, Bocken, and Evans for the development of the VOLTO JÁ project. The objective of the VOLTO JÁ project is to operationalize a senior exchange programme between SEOs. The VM approach extends beyond conventional customer value propositions to prioritize sustainability for all stakeholders and identify key drivers of sustainable business model (SBM) innovation. The multi-stakeholder methodology comprises the following elements: (1) sequential focus groups aimed at enhancing sustainable business thinking; (2) semi-structured interviews; and (3) workshop to facilitate qualitative analysis and co-create the VM. The findings are then categorized into four value dimensions: (1) value captured—improved participant well-being, enhanced reputational capital, mitigation of social asymmetries, and affordable service experiences; (2) value lost—underused community assets; (3) value destroyed—institutional and systemic barriers to innovation; and (4) new value opportunities—knowledge sharing, service diversification, and open innovation to foster collaborative networks. The study demonstrates that the application of VM in SEOs supports SBM development by generating strategic insights, enhancing resource efficiency, and fostering the delivery of socially impactful services.

1. Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [1] underlined the pressing need for a collaborative approach to shared global problems [2] and making significant changes across economic systems [3]. In this case, the participation of multiple stakeholders is essential. Munaro and Tavares [4] highlight that “member countries have been seeking strategies and policies to achieve sustainable management and efficient resource use”, reinforcing the need for collaboration across various sectors. Sustainability requires partnerships involving businesses, governments, social economy organizations, and academia to leverage complementary knowledge and share best practices [5]. Engaging these stakeholders effectively helps to identify and prioritize the environmental and social issues that need to be considered: (1) reinforcing the shift in conventional business models (BM); (2) focusing on generating value not just for shareholders but for a broader range of stakeholders, including society and the environment [5].

Social Economy Organizations (SEOs) operate within hybrid institutional logics, balancing the creation of social value with financial sustainability [6]. This dual mission introduces complex value flows involving multiple stakeholders (members, employees, communities, funders, and the environment), whose interests may sometimes converge and conflict at other times. This complexity introduces challenges in designing business models that equitably capture, create, and distribute value.

Traditional business model frameworks, such as the Business Model Canvas [7], focus primarily on value proposition and revenue mechanisms but often fail to fully capture the multidimensional value creation, destruction, and distribution processes at the core of SEOs’ mission-driven activities. As such, there is a need for tools that can systematically analyze these hybrid value dynamics.

This study is grounded on the premise that identifying and understanding the causes and consequences of uncaptured value in a BM is essential for SEOs to enhance the value they deliver to stakeholders. For that purpose, we use the value mapping tool (VMT) by Short et al. [8] and Bocken et al. [9] presented in the literature to provide “a systemic approach to the generation of new business model ideas for sustainability that apply a multi-stakeholder perspective and explores both positive and negative forms of value creation” [10]. This tool offers a structured approach that maps value along four dimensions: (1) value captured (value realized by the organization and its stakeholders); (2) value missed (untapped or unrealized value); (3) value destroyed (negative externalities or mission-detracting outcomes); and (4) value opportunities (areas for new or expanded value creation).

Unlike traditional frameworks, such as Social Return on Investment (SROI), which tries to capture the value of social impact by translating it into monetary terms [11], a VMT is inherently stakeholder-centred and designed to address both positive and negative value flows that are not always tangible. In fact, SROI can be quite complex, and by focusing on monetization, it may oversimplify the richness of social value [12,13]. Issues like how stakeholders are chosen, which indicators or “proxies” are used, how long impacts are expected to last, or how much would have happened anyway (the “deadweight”) all affect the result—and not always in transparent ways [14,15].

Therefore, the VMT is particularly suitable for the application within SEOs, where multi-stakeholder governance, shared ownership, and mission-driven strategies define organizational success [16,17].

Empirical applications of the VMT have so far been largely concentrated in the areas of sustainable business models (SBM) [9,10,18], circular economy networks [19], and hybrid business models addressing uncaptured value [20]. Borchardt et al. [19] have applied a VMT-derived framework to analyze circular supply chains involving both profit and non-profit actors, revealing critical gaps in social value realization.

Agafonow [17] specifically discusses value capture and value devolution in social enterprises, providing evidence that multi-stakeholder hybrid organizations face ongoing tensions between economic capture and social mission. These studies point to the adaptability of the VMT beyond conventional corporate contexts. However, despite its theoretical suitability, there is still limited research applying the VMT directly to SEOs as a distinct sector. This creates an opportunity to extend the VMT’s theoretical and practical utility by explicitly exploring its application to SEOs’ unique governance structures, stakeholder diversity, and mission-driven activities.

Research into social and SBM design processes is indeed lacking, notably as most of the players involved have a social purpose but also face scarcity of resources and are responsible for generating shared value by using economic activities to achieve a positive social, environmental, and societal impact [21].

It is therefore fundamental to explore which stakeholders are actively involved and how they interact, through the lens of Stakeholder Theory, and their effect on SBM design. The VMT approach [10] could be crucial in this endeavour, as it emphasizes the environment and society and allows a value proposition to be created to support SBM design.

The novelty of this study lies in applying the VMT to explore the roles of stakeholders in value creation and value capture within the social sector. By integrating the VMT with Stakeholder Theory, the study offers a more holistic and dynamic lens through which to analyze value flows in collaborative social economy contexts. This interdisciplinary approach provides an original contribution to the field of SBM by capturing the complexity, interdependence, and multi-stakeholder nature of value generation in mission-driven organizations.

A mixed-method approach was adopted to collect data suitable for the VMT and Stakeholder Analysis: (1) sequential focus group sessions (SEO managers, seniors’ assistants, social workers, academics, seniors, caregivers, social tourism partners, local authorities, international consultants) with a view to enhancing sustainable business thinking; (2) semi-structured interviews and surveys, with institutionalized elderly people in SEO to understand their motivations, expectations and limitations; (3) a workshop to provide input for a qualitative analysis to create the VM. The data collection activities described above, aimed at informing the development of the SBM, were conducted within the framework of the VOLTO JÁ project and involved close collaboration with multiple SEOs.

The article follows with a description of the applied methods followed by the results, discussion, and a conclusion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Economy Organizations and Sustainable Value Creation

Social Economy Organizations are increasingly gaining importance in addressing complex sustainability challenges by integrating social, economic, and often environmental goals [1,2]. They pursue dual or multiple value objectives, balancing economic viability with social mission fulfilment [3,4].

Social business models differ from traditional business models in two key respects: the primacy of social value creation and the heightened level of stakeholder involvement [16]. Kullak et al. [21] studied the case of the Social Purpose Organizations (SPOs) and their duality of purpose: social and economic. They demonstrated that “despite modest funding and minimal staffing, an organization can bring together a broad network to engage in resource integration and shared value creation for social good” by enhancing actor collaboration and resource integration processes (knowledge, skills, and financial resources). In these cases, an engagement platform works as a facilitator, providing structural support for the exchange and integration of resources and value co-creation by generic interdependent actors in a highly complex environment. In the SPO context, cross-sector social partnerships [22] could also be useful for shared value creation.

In their empirical study centred on social innovation BM, Komatsu et al. [23] identified four typologies of social innovation BM: beneficiary as actor, beneficiary as customer, beneficiary as user, and community-asset-based models. Their starting point is the separation of social and commercial value propositions and considering the optimal equilibrium between cost reduction and financial supporters and emphasized the role of “in-kind” supporters, as the “key promoters and source of resources” (p. 334), allowing cost-cutting in the social BM as well as a leverage of inputs to maximize social value. The authors assume that social value is generated and sustained in both the value proposition and their value constellation [16,23]; services are provided through both the internal value chain and external partners’ support.

Social BMs reflect the reinvention of the social objective as these organizations work where the market fails [24]. SEOs exist in a competitive environment, notably in the case of those competing with other providers of social services [25]. Collaboration with other actors, such as universities and research centres, can promote the transfer of technology and knowledge, strengthening the role of SEOs in solving social and environmental problems [26], as well as a competitive advantage [27,28].

Studies based on social BMs have concluded that the changing environment can bring a sustainable competitive advantage, impacting various economic sectors. One study on the components of these models identified that the mission, internal structure, financial management, and market are essential elements for value generation [29]. The authors also identified that social BMs often interact with a wide range of stakeholders, aiming for both economic sustainability and social impact. In addition, studies of BMs in the sharing economy [30] found that they enhanced value distribution, reduced ecological impacts, used resources more efficiently and, at the same time, improved social networks [31]. Nevertheless, it is still not clear whether and how this value is created within networks of actors in the long-term [32]. Interaction and alignment, especially cross-sector collaboration between stakeholders [33], are far from being a systemic practice [21] or a joint purpose for all stakeholders [32].

2.2. Sustainable Business Models and Stakeholder Theory in the Social Economy Organizations

Current trends show that organizations need to place sustainability at the centre of their corporate strategies, going beyond mere regulatory compliance to lead corporate responsibility actions [34], engaging multiple stakeholders, and requiring collaboration among industries, governments, and civil society to address the complex challenges.

The 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) play a central role in defining and promoting sustainability practices within organizations. The adoption of these goals is prompting organizations to rethink their BM and incorporate conscious practices aimed at social and environmental well-being [2]. According to a 2021 report by Accenture, the pressure is increasing, driven by ESG practices [35]. This approach has gained global momentum as companies increasingly realize that sustainability is essential for long-term success and to maintain a competitive position [36].

The SBM is defined as a model that incorporates “proactive and multi-stakeholder management, the creation of monetary and non-monetary value for a broad range of stakeholders and holds a long-term perspective” [37]; stakeholders assume the position of both co-creators and beneficiaries [38], combining alternative analytical lenses and solutions and offering new pathways to a more sustainable and collaborative model [33].

Recent research highlights that collaboration and stakeholder engagement play a fundamental role in SBM, depending on the focus and intended outcome [39]. Various forms of engagement, such as inclusion, integration, and balance among diverse interests (economic, environmental, and social), have been proposed to promote sustainable value [40]. In the business modelling process, the consistency of the interaction of those different actors can involve the “deploying of individual or collective self-commitments as well as commitment services in their stakeholder relations” [41] and the development of structured cooperation between stakeholders for a better coordination of expectations [42,43].

For sustainable BMs to be effective, organizations need to consider the inclusion of social concerns in their business decisions [44]. In this way, generating social value is tied to the well-being and safety of employees, customers, and communities, fostering stronger social relationships and enhancing collective well-being [4,44]. From this perspective, challenges in BM design are more comprehensive, given that conventional BM are focused on the value proposition and on the customer’s needs, emphasizing economic performance [7,27] in accordance with the traditional firm theory [42]. Historically, during and after the 1990s, a BM was used as a link between the binomial of technology development and economic value creation [45]. Teece [46] and Osterwalder and Pigneur [7] describe the BM as a mechanism that allows an organization to create, deliver, and capture value through its operations or as a “system of interdependent activities that transcends the focal firm and spans its boundaries” [47], exploring the interaction between business modelling and networking.

Sustainability-oriented business model frameworks have been studied by various authors: the network-level BM by Lindgren et al. [48]; the collaborative business approach by Rohrbeck et al. [49]; a value mapping tool by Short et al. [8] and Bocken et al. [9]; an enterprise framework compatible with natural and social science by Upward and Jones [50]; the triple-layered BM canvas by Joyce and Paquin [51]; a framework and facilitation method for values-based network and BM innovation by Breuer and Lüdeke-Freund [52]; a framework for using value uncaptured for SBM innovation by Yang et al. [20] that gives explicit attention to social-economic trade-offs; and a stakeholder value creation framework structure by Freudenreich et al. [32].

Therefore, to capture economic value, while generating environmental and social value, it is necessary to adopt a holistic and integrated approach when designing the BM. This involves incorporating sustainability principles and multiple perspectives into the value proposition, focusing on an approach that considers the economic, social, and environmental interests of stakeholders [44,53].

Aligned with this new formulation of the BM, Pedersen et al. [33] described “new and potentially sustainability-driving BM given that value creation, delivery and capture of organizations are intimately related to the collaborative ties with their stakeholders”; examples include triple bottom line BM [51], green BM [54], social BM [16], shared value BM [55], and flourishing BM [24]. Also, Geissdoerfer et al. [56] described a BM as “simplified representations of the elements—and interactions between these elements—that an organizational unit chooses in order to create, deliver, capture, and exchange value”.

In this context, Stakeholder Theory (ST) offers a valuable lens to interpret and manage the complexity of SEO value creation. Originating from Freeman’s seminal work [57], ST argues that organizational success depends on the ability to satisfy the interests of multiple stakeholder groups—not only shareholders. Mitchell et al. [58] further develop this framework by introducing the dimensions of power, legitimacy, and urgency to assess stakeholder salience. In SEOs, where stakeholders include funders, public institutions, service users, volunteers, employees, and community members, stakeholder relationships are inherently complex and dynamic [59].

Recognizing and balancing these diverse interests is essential for the successful implementation of sustainable business models in SEOs. Moreover, the legitimacy and effectiveness of SEOs often depend on their capacity to co-create value with stakeholders, respond to shifting expectations, and avoid mission drift. This makes stakeholder-oriented approaches not only theoretically appropriate but practically necessary for sustainability in the social economy.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. VOLTO JÁ Project

The VOLTO JÁ project provides the empirical foundation for this study [60], serving as a pilot project to explore how the VMT can be applied to support the design of an SBM within SEOs, offering a real-world context in which value is co-created across stakeholders.

Developed as a pilot project in the Alentejo region of Portugal, VOLTO JÁ focuses on an innovative senior exchange programme. The project promotes cultural, social, and recreational experiences for the institutionalized elderly, emphasizing objectives such as social inclusion, emotional well-being, and active ageing, without monetary costs for the elderly.

By incorporating digital tools like the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) platform and forming collaborative networks across multiple SEOs, the project represents a concrete example of how sustainability-oriented services can be designed and scalable in the third sector.

A multidisciplinary team of academic researchers, SEO professionals, local government representatives, and elderly individuals themselves contributed to the project design and execution. This inclusive approach allowed for rich stakeholder input, provided the support to promote senior exchange and the necessary depth for the VMT to be applied effectively.

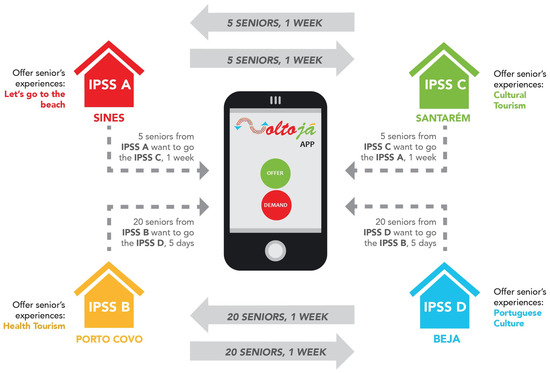

Santa Casa da Misericordia de Santarém, an SEO that is part of a national network of homes for the elderly, was one of the main stakeholders in the project. This collaborative endeavour supported by an ICT platform facilitated the leveraging of the network in the Alentejo region to enhance the mobility of elderly individuals (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The VOLTO JÁ project idea. Note: Illustrative designations.

3.2. Research Design Overview

The VOLTO JÁ project development followed a multi-stakeholder approach. A stepwise methodology was followed to develop, test, and design the value ideation process.

A qualitative approach based on a new perspective of stakeholder analysis was used, which allowed the identification of catalysts for SBM innovation, using the VMT developed by Bocken et al. [9], complemented by the methods of Ollár et al. [61] and Geissdoerfer et al. [56].

The VMT is an interactive design process in which SBMs are developed, selected, adjusted, and/or improved through sustainable value exchange, with each stakeholder identified (e.g., customers, network actors, society, and the environment) [9,62]. Design thinking is a suitable process to support the VMT as it allows value to be captured in a complex environment, which, in this case, consists of the discussion of triple bottom line sustainability in multidisciplinary teams. However, more research is needed to test it mainly in SEOs [63].

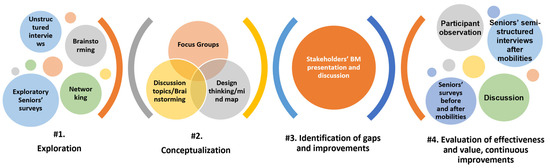

To support the use of the VMT and stakeholder analysis, a data collection process was performed in four phases, in line with Geissdoerfer et al. [56]: exploration, conceptualization, identification of gaps and improvements, and evaluation (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overview of research methods.

In the first phase, grounded on the existing literature, the main potential stakeholders were identified; second, a draft of the SBM for the VOLTO JÁ project was developed, based on the Osterwalder and Pigneur [7] framework, taken as a starting point; third, gaps and potential improvements were identified through the focus group and workshop conducted with relevant stakeholders. The concept design was field-tested during the project exchanges. Finally, evaluation and feedback from the field test using the VMT improved SBM’s applicability to the VOLTO JÁ project.

The VMT was applied, and the steps, methods, actions, and outputs for each phase of the process are summarized in what follows.

3.2.1. Exploration

The first step was to conduct an extensive literature review on the SBM to serve as guidance to identify key stakeholders. This was achieved using several sources, such as Web of Science and EBSCO, peer feedback, and cross-reference. In parallel, several informal meetings were organized with seven senior researchers from the Politécnico de Santarém (Portugal), four senior researchers from the Politécnico de Beja (Portugal), and practitioners from the SEO. Senior researchers had a wide range of expertise: management, tourism, computer science, statistics, nursing, communication, and design. At the end of the process, the team identified the fundamental stakeholders.

The participants in the mobilities were identified through a convenience sampling strategy, relying on institutional affiliations with the project partners, as mentioned above. Initial contacts were established through SEO networks in Alentejo and through academic links. Institutionalized seniors were approached via SEO directors, and their willingness to participate was confirmed through exploratory surveys.

Exploratory surveys were applied to institutionalized seniors. The surveys administered not only allowed us to establish the seniors’ profile and willingness to participate but also enlarged the community network.

3.2.2. Conceptualization

This phase focused on collecting information through expert and research meetings. Two focus group meetings were organized to design the first draft of the SBM for subsequent presentation in the workshop. The first focus group meeting took place in Beja (Portugal) and included the following participants: three senior researchers from the Politécnico de Beja, two senior researchers from the Politécnico de Santarém, and two technical directors from SEOs.

The second focus group meeting took place in Santarém (Portugal) and included the following participants: five senior researchers from the Politécnico de Santarém, and four technical directors from SEOs. The procedures followed in each session were similar. The selection of participants for each focus group was based on their expertise, as explained in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants and role in each focus group.

The facilitator used a semi-structured script to conduct the session. The script was the result of a list of items reviewed by the authors (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Main topics of focus groups 1 and 2.

Tape recording and note-taking were used by experienced observers to ensure that all information was correctly collected [64].

3.2.3. Identification of Gaps and Improvements—Workshop

The identification of gaps and improvements was made through a workshop with the participation of key stakeholders. It was attended by five senior researchers from the Politécnico de Santarém (Portugal), and eleven professionals (technical directors and social educators) from seven SEOs.

The goal of the workshop was threefold: (1) the public presentation of the VOLTO JÁ SBM, collecting feedback from all the participants; (2) reinforcing fundamental relationships in the ideation stage for technology and innovation purposes; (3) enlarging the network ties through the sharing of experiences between academia and SEOs.

A member of the research team took notes on the participants’ comments and group discussion. All the insights were used to improve the SBM design for subsequent testing in a realistic scenario and targeting the audience. The workshop lasted for 150 min.

3.2.4. Evaluation of Effectiveness, Value, and Continuous Improvements

In the fourth phase, the effectiveness of the SBM design was assessed in a real context. The selected testing sample, comprising twenty-three participants in the VOLTO JÁ project, actively collaborated for 6 months. Six exchange mobilities were held, involving six SEOs. All participants were older adults and clients of one of the six SEOs that are partners of the VOLTO JÁ project, as explained in Section 3.2.1.

The evaluation process was performed through participant observation, semi-structured interviews of seniors after the exchanges events and surveys administered to seniors, before and after the exchange events.

A semi-structured interview after the exchanges was conducted using a script based on the literature review, the Satisfaction Assessment Questionnaires provided by the Portuguese Social Security Institute [65,66,67], and the objectives of the study. The speech of each interviewee was summarized and subsequently analyzed using content analysis procedures. The interviews were recorded on audio support, with prior authorization from the organization and each individual’s consent, and later transcribed in full.

Senior researchers independently coded interview data and stakeholder workshop outputs using the VMT’s four value dimensions. Discrepancies in coding were discussed and reconciled through peer debriefing, ensuring interpretive consistency and reducing potential bias.

Two structured surveys were administered to each senior: the first, one week before the exchange event, and the second, one week after the exchange event. A quasi-experimental design without a control group was implemented to measure the impact of participation in the project on senior lives. This impact was assessed by obtaining measures of the quality of life [68], satisfaction with life [69], happiness [70], and emotional well-being [71]. Table 3 provides an overview of the phases described above.

Table 3.

Four phases of the VM tool.

3.2.5. Ethical Considerations

All data collected through the questionnaire were fully anonymous, ensuring that no personal data were gathered that could allow the identification of participants. For the interviews, all data were pseudonymized, with no references or links to participant names or identifiable details at any stage of the analysis or reporting. Furthermore, a formal protocol was established between the researchers’ affiliated academic institutions and the participating social economy organizations to govern the conduct of the focus groups, interviews, and questionnaires. Participation of seniors and other stakeholders from the social economy entities was always preceded by the reading and signing of an informed consent form by all subjects involved. In accordance with the applicable legal framework—namely, the EU General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679) and its implementation under Portuguese Law no. 58/2019—research activities involving anonymous or pseudonymized data that do not involve sensitive personal data do not require prior approval from an ethics committee.

4. Results

This section presents the results for each of the phases described in Section 3.2, with emphasis going to the focus group, workshop, and seniors’ exchange events, which were the main sources for identifying the gaps and opportunities for improvement and evaluation.

The literature review and the expert meetings led to (1) the identification of key stakeholders; (2) clarification of the expected role for stakeholders in the VOLTO JÁ project; (3) first contact with SEO; and (4) dissemination of the VOLTO JÁ project’s goals.

Table 4 summarizes key insights from the two focus groups conducted with SEO managers and academic researchers. Findings are organized into thematic categories, identifying core considerations for designing and implementing the VOLTO JÁ senior exchange initiative.

Table 4.

Focus group results.

The extracted information led to the main blocks that will support the draft of the SBM. All the participants recognize that this kind of activity is important for the elderly as a vehicle to increase well-being and combat social exclusion. The concern about security and comfort of the elderly was permanent. The SEO that was most willing to participate was also the most focused on innovation processes and recognized the importance of the link with academia.

The main barriers were related to transportation, human resources, and costs. It was generally agreed that the target should be as inclusive as possible whilst taking some physical and cognitive restrictions into consideration. It came as no surprise that networking was the solution found for monetary support. This kind of organization is used to dealing with resource scarcity to searching for creative solutions.

Based on the results of the focus groups and the first phase, the authors were able to present the draft of the SBM to assess gaps and opportunities for improvement. The workshop highlighted the role of stakeholders as social innovators. We begin with a novel idea, pursuing social change as path-builders not just for the direct beneficiaries but potentially for all the stakeholders and actors involved. The purpose of an SEO is to help solve the trade-off between value creation and capture. The value preposition was scrutinized under the VMT and is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Value mapping—value created, value missed, value destroyed, and new opportunities.

After the workshop, the value preposition and some components of the SBM were adapted based on the results of the VMT. The results from the evaluation phase were fundamental. The exchange mobilities were the ideal test of the SBM design.

Due to the large volume of information collected, a summary is useful to depict the main results of the semi-structured interviews and the questionnaire survey administered before and after the exchange events.

To some of the seniors participating, the VOLTO JÁ Project exchange was the only tourist experience ever (before and after their institutionalization). The findings show that this is either due to economic or social circumstances (isolation/loneliness), as in Morgan et al. [73], or health problems.

The quasi-experimental design implemented with the seniors that participated in the exchange revealed that their participation in touristic and cultural activities increased their emotional well-being. The related-samples Wilcoxon signed-rank test (a non-parametric test) indicated that emotional well-being after the VOLTO JÁ project was statistically significantly higher than the emotional well-being before the VOLTO JÁ project (Z = 172.5; p = 0.046). However, no statistically significant differences were found in the measures of quality of life, satisfaction with life, and happiness.

The analysis of the item’s measures reveals that the significant results were in measures that considered the way seniors feel in the week before the activities [e.g., example of the emotional well-being item: “How much of the time during the past week were you happy?”; European Social Survey, cited by Michaelson et al. [71]]. The nonsignificant measures include more stable constructs (satisfaction with life; happiness in general) that are not affected by short-term activities. Participation in the exchange proved to have a positive impact on the life of seniors, at least when considering the short-time effects.

The interview proved to be particularly revealing as it allowed interviewees to express themselves freely and highlighted the specific importance of the VOLTO JÁ project experience in their lives. The interviewees who acknowledged the impact of these experiences on their quality of life emphasized the positive effects of escaping from the daily routine, especially on an emotional level; the vast majority of respondents said it brought relief, relaxation, enthusiasm, and expectation/stimulus. This long-term physical or emotional impact is illustrated by one of the interviewees’ comments: “I am alone and when I think about these things, and it fills me”.

The feelings, emotions, opinions, and attitudes that seniors developed during the tourist activities were the added value that this programme brought to them and their lives. These intangible outputs shed light on how the tourist activities influence the seniors’ satisfaction with the organization. The increased satisfaction with the organization due to participation in social tourism activities was measured by the attractiveness of the activities programme, expressed willingness to repeat the experience, and feelings such as well-being and happiness, the competence attributed to the organization, and the relationships generated between participants and employees during the mobilities. All these results will be reflected in the final version of the SBM.

To operationalize the stakeholder perspective informed by Stakeholder Theory, a structured stakeholder matrix was developed (see Table 6). This matrix identifies the stakeholders involved in the initiative and classifies their positions, interests, potential conflicts, and areas of synergy, and it emerged from fieldwork and participatory methods.

Table 6.

Stakeholder analysis and value interactions.

5. Discussion

Supporting the insights from Short et al. [8] and Bocken et al. [9], based on the results, it is possible to infer that the VMT fits the approach for BM innovation. The VM approach proved to be suited to the case of an SEO environment. As Santos [74] substantiates, the SBM design in such contexts suggests analyzing and exploring the role of stakeholders in value creation and in value capture, taking into consideration that these are simultaneous processes. A wide range of stakeholders were involved in the VOLTO JÁ SBM design process—SEO (top managers, technical directors, and other staff), academic researchers, municipalities, seniors, external advisors (national and international level), and community members. This diversity of stakeholders was important for the success of the model, as discussed by Bocken et al. [18], who emphasize the importance of integrating different perspectives in the formulation of value propositions.

The VOLTO JÁ SBM was developed through the use of cross-sector social partnerships [22] as an interactive process that allowed the positive alignment for value co-creation, as sustained by Freudenreich et al. [32], Kullak et al. [21], and Pedersen et al. [33], considering stakeholders as both co-creators and beneficiaries, as highlighted by Franzidis [38]. Moreover, the literature suggests that identifying and mapping the relationships between stakeholders is essential for maximizing the social and environmental impact of the model, in line with the practices of SBM discussed by Geissdoerfer et al. [37].

Considering the unique nature of the social sector in addressing market failures, fostering new social ties, tackling emerging challenges, and developing alternative solutions, it is crucial to establish networks of actors with a long-term perspective. The construction of such networks facilitates the exchange of resources and knowledge and promotes social innovation through intersectoral collaboration, as argued by Weber et al. [75]. In this context, the key to the SEO to maximize social value consists of an exercise of equilibrium between social value creation and stakeholder investment and, also, between cost cutting and leverage of inputs, supporting the findings of Michelini [76] and Komatsu et al. [23].

The expansion of value creation in the SBM, as suggested by Freudenreich et al. [32], can reinforce mutual stakeholder relationships as both recipients and (co-)creators: first, via different types of value creation with/for diverse stakeholders, and second, by the resulting value portfolio (different kinds of value exchanged between stakeholders). The VOLTO JÁ Project was designed to be an SBM following these two paths: first, by exploring the VMT and the four types of value, as defined by Bocken et al. [10], with the inclusion of different perspectives of value for each type of stakeholder—value created, missed, destroyed, and new value opportunities)—and second, by exploring different types of value/resources exchanged between stakeholders (Table 4—Focus group results), facilitating stakeholder relationships and corresponding value exchanges. These results also provide insight that the success of the collaborative network between SEO depends, to a large extent, on factors already identified in the literature [30,77,78]: shared values, absence of opportunistic behaviour, sharing of knowledge, trust, and commitment.

Developing an ICT platform as a support for the VOLTO JÁ SBM has allowed the leveraging of the development of dynamic capabilities of the network of partners [30,77,78], combining knowledge, skills, and financial resources, and playing the role of a facilitator, reinforcing the structural support for social value creation in a highly complex environment [79]. The use of this technology promotes the interchangeability of information and amplifies organizations’ ability to respond quickly to changes in the environment, allowing for a more effective alignment of their strategies, as discussed by Matzembacher et al. [80].

6. Conclusions

This study reflects a research gap in the sustainable business model literature, exploring the application of the Value Mapping Tool as a strategic framework for supporting SBM innovation within SEOs. The study adopts a qualitative approach based on sustainable business thinking employing semi-structured interviews, focus groups, brainstorming, surveys, workshops, and a concept test administered to key SEO stakeholders. The VMT was applied in a collaborative process and complemented by other important tools; this allowed the identification of different forms of value (created, destroyed, missed, and also new opportunities of value), leading to greater sustainability and validating the applicability of the value proposition.

Using the VOLTO JÁ project, the research demonstrated how the VMT can effectively uncover and analyze the full spectrum of stakeholder value—including created, missed, destroyed, and emerging opportunities—in a collaborative, mission-driven context.

Value creation for SEOs is associated with strengthening ties in a dynamic, continuous iteration, generating a spillover effect throughout the network of stakeholders. The VMT not only improves comprehension of stakeholder contributions and requirements but also highlights important trade-offs and conflicts present in social innovation processes. The method promoted inclusive discourse and identified areas for improvement that could otherwise go undetected in conventional planning processes by incorporating stakeholders, including elderly individuals, SEO managers, carers, local authorities, and institutional partners.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to apply the VMT in the design of an SBM for an SEO, providing a significant and innovative contribution (academic and practical) by examining the effectiveness of this tool within the specific context of SEOs.

6.1. Academic Implications

This study contributes to the literature by applying Stakeholder Theory within SEOs, operationalized through the VMT. By systematically mapping stakeholder roles, interests, and interdependencies, it advances understanding of value co-creation processes and potential areas of conflict in SBMs. The development of a structured stakeholder matrix offers a replicable approach for analyzing hybrid value dynamics in mission-driven contexts, addressing a gap in research on stakeholder engagement in the SBM design and implementation.

Moreover, the study broadens the theoretical scope of the VMT by applying it within the relatively under-researched field of SEOs. It shows how the tool can be adapted to organizations operating under hybrid institutional logics and resource constraints. This application provides new insights into how SEOs balance economic sustainability with social mission, a central challenge in the social economy.

This research makes a significant contribution to the academic discourse on sustainable innovation and business model development by emphasizing participatory and stakeholder-centred approaches. The findings establish a theoretical and methodological foundation for future studies on collaborative value creation, particularly in contexts where social impact and stakeholder alignment are as critical as financial performance.

6.2. Practical Implications

This study offers relevant practical implications for managers of SEOs, policymakers, and stakeholders engaged in collaborative initiatives such as the VOLTO JÁ project. The findings highlight key areas for cooperation, including ensuring the accessibility and usability of digital platforms for senior participants, developing long-term sustainability strategies through partnerships between SEOs and local authorities, and fostering social integration through initiatives that engage seniors and the wider community.

Nevertheless, several areas of tension persist. These include the challenge of balancing financial sustainability with non-profit values, supporting older adults in the adoption of digital tools, and integrating environmental sustainability considerations without hindering tourism development.

To address these challenges, it is recommended to prioritize improved access to technology and mobility programmes for seniors, enhance the financial resilience of SEOs while safeguarding their social missions, and align public policies to provide more targeted institutional support. Conflict resolution strategies should include training programmes and simplified ICT solutions to assist senior users, along with encouraging partnerships with local businesses and greater access to public funding mechanisms. Finally, the study underscores the importance of collaborative strategies that promote shared value creation—such as joint initiatives between SEOs and city councils, awareness campaigns for active ageing, and the integration of sustainable practices into social business models.

6.3. Limitations

This study is based on a pilot project—VOLTO JÁ—which, while enabling an in-depth and context-sensitive exploration of value creation within a collaborative network of social economy organizations (SEOs), inherently limits the generalisability of the findings. Moreover, additional research is required to validate the potential scalability of this SBM. Future research could enhance the robustness and transferability of the proposed framework by incorporating comparative multi-case studies across diverse geographic, institutional, or policy environments. It should also make use of appropriate qualitative data analysis software (e.g., Atlas.ti) to enable more systematic coding and facilitate comparative analyses across multiple case contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.V., S.O., S.L., J.A.M.N. and L.C.B.; methodology, C.V., S.O., J.A.M.N. and S.L.; validation, C.V., S.O., S.L., J.A.M.N. and L.C.B.; writing, C.V., S.O., S.L., J.A.M.N. and L.C.B.; writing—review and editing, C.V., S.O., S.L., J.A.M.N. and L.C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT)/Alentejo2020—VOLTO JÁ: programa de intercâmbio sénior (Ref. ALT20-03-0145-FEDER-024111) and by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) —Life Quality Research Centre (LQRC) (Ref. UID/CED/04748/2023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of anonymous/pseudonymized non-sensitive data, in accordance with the EU GDPR (Regulation (EU) 2016/679) and Portuguese Law no. 58/2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals: Seventeen Goals to Transform Our World. 2015. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- World Economic Forum. The Global Competitiveness Report 2019. 2019. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2019.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M. Sharing Versus Collaborative Economy: How to Align Ict Developments the Sdgs in Tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaro, M.R.; Tavares, S.F. A Review on Barriers, Drivers, and Stakeholders Towards the Circular Economy: The Construction Sector Perspective. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2023, 8, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-W.; Fu, M.-W. Conceptualizing Sustainable Business Models Aligning with Corporate Responsibility. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Social Enterprise in Europe: At the Crossroads of Market, Public Policies and Third Sector. Policy Soc. 2010, 29, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Evans, S. Embedding Sustainability in Business Modelling through Multi-Stakeholder Value Innovation. In Advances in Production Management Systems. Competitive Manufacturing for Innovative Products and Services. Apms 2012. Ifip Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Emmanouilidis, T.M., Kiritsis, C.D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.; Short, S.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A Value Mapping Tool for Sustainable Business Modelling. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Eff. Board Perform. 2013, 135, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.; Rana, P.; Short, S.W. Value Mapping for Sustainable Business Thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2015, 32, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.; Lawlor, E.; Neitzert, E.; Goodspeed, T. A Guide to Social Return on Investment. The SROI Network. 2012. Available online: https://socialvalueselfassessmenttool.org/wp-content/uploads/intranet/758/pdf-guide.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Mook, L.; Maiorano, J.; Ryan, S.; Armstrong, A.; Quarter, J. Turning Social Return on Investment on Its Head. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2015, 26, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, P.W.; Lyne, I. Social Enterprise and the Measurement of Social Value: Methodological Issues with the Calculation and Application of the Social Return on Investment. Educ. Knowl. Econ. 2008, 2, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.G.; Lueg, R.; Liempd, D.V. Challenges and Boundaries in Implementing Social Return on Investment: An Inquiry into Its Situational Appropriateness. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2021, 31, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidson, M.; Lyon, F.; McKay, S.; Moro, D. Valuing the Social? The Nature and Controversies of Measuring Social Return on Investment (Sroi). Volunt. Sect. Rev. 2013, 4, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.; Moingeon, B.; Lehmann-Ortega, L. Building Social Business Models: Lessons from the Grameen Experience. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agafonow, A. Value Creation, Value Capture, and Value Devolution: Where Do Social Enterprises Stand? Adm. Soc. 2015, 47, 1038–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A Literature and Practice Review to Develop Sustainable Business Model Archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchardt, M.; da Silva, M.G.; de Carvalho, M.N.M.; Burdzinski, C.S.; Kirst, R.W.; Pereira, G.M.; da Sliva, M.A. Uncaptured Value in the Business Model: Analysing Its Modes in Social Enterprises in the Sustainable Fashion Industry. J. Creat. Value 2024, 10, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.S.; Vladimirova, E.D.; Rana, P. Value Uncaptured Perspective for Sustainable Business Model Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1794–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullak, F.S.; Baker, J.J.; Woratschek, H. Enhancing Value Creation in Social Purpose Organizations: Business Models That Leverage Networks. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez-Ponce, E.; Clarke, A.C.; Colbert, B.A. Collaborative Sustainable Business Models: Understanding Organizations Partnering for Community Sustainability. Bus. Soc. 2021, 60, 1174–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, T.; Deserti, A.; Rizzo, F.; Celi, M.; Alijani, S. Social Innovation Business Models: Coping with Antagonistic Objectives and Assets. In Finance and Economy for Society: Integrating Sustainability; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2016; pp. 315–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kania, R.; Lestari, Y.D.; Dhewanto, W. Social Innovation Business Model: Case Study of Start-up Enterprise. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2017, 6, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bloice, L.; Burnett, S. Barriers to Knowledge Sharing in Third Sector Social Care: A Case Study. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasi, G.; Calderini, M.; Chiodo, V.; Gerli, F. Social-Tech Entrepreneurs: Building Blocks of a New Social Economy. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models and Dynamic Capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; McDonald, R.E.; Mort, G.S. Sustainability of Nonprofit Organizations: An Empirical Investigation. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neessen, P.C.M.; Voinea, C.L.; Dobber, E. Business Models of Social Enterprises: Insight into Key Components and Value Creation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J. Debating the Sharing Economy. 2014. Available online: https://greattransition.org/publication/debating-the-sharing-economy (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Cheng, M.M. Current Sharing Economy Media Discourse in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 60, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenreich, B.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Schaltegger, S.A. Stakeholder Theory Perspective on Business Models: Value Creation for Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics. 2020, 166, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R.G.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Henriques, I.; Seitanidi, M.M. Toward Collaborative Cross-Sector Business Models for Sustainability. Bus. Soc. 2021, 60, 1039–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olynec, N. Sustainability Trends Shaping Corporate Priorities in 2024. 2023. Available online: https://www.imd.org/ibyimd/2024-trends/sustainability-trends-shaping-corporate-priorities-in-2024/ (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Accenture. Shaping the Sustainable Organization. 2021. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/content/dam/accenture/final/a-com-migration/thought-leadership-assets/accenture-shaping-the-sustainable-organization-report.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Ensign, P.C. Business Models and Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Sustainable Business Model Innovation: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzidis, A. An Examination of a Social Tourism Business in Granada, Nicaragua. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 1179–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fobbe, L.; Hilletofth, P. The Role of Stakeholder Interaction in Sustainable Business Models. A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 327, 129510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manninen, K.; Laukkanen, M.; Huiskonen, J. Framework for Sustainable Value Creation: A Synthesis of Fragmented Sustainable Business Model Literature. Manag. Res. Rev. 2024, 47, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, M.; Hielscher, S.; Pies, I. Commitment Strategies for Sustainability: How Business Firms Can Transform Trade-Offs into Win-Win Outcomes. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Zander, U.; Barney, J.B.; Afuah, A. Developing a Theory of the Firm for the 21st Century. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 45, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Chea, R.; Jain, A.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Gurtoo, A. The Business Model in Sustainability Transitions: A Conceptualization. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlito, R.; Faraci, R. Business Model Innovation for Sustainability: A New Framework. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2022, 19, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Rosenbloom, R.S. The Role of the Business Model in Capturing Value from Innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s Technology Spin-Off Companies. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2002, 11, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business Model Design: An Activity System Perspective. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, P.; Taran, Y.; Boer, H. From Single Firm to Network-Based Business Model Innovation. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2010, 12, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrbeck, R.; Konnertz, L.; Knab, S. Collaborative Business Modelling for Systemic and Sustainability Innovations. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2013, 63, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upward, A.; Jones, P. An Ontology for Strongly Sustainable Business Models: Defining an Enterprise Framework Compatible with Natural and Social Science. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.L. The Triple Layered Business Model Canvas: A Tool to Design More Sustainable Business Models. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, H.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Values-Based Network and Business Model Innovation. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 1750028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagin, M.; Håkansson, J.; Olsmats, C.; Espegren, Y.; Nordström, C. The Value Creation Failure of Grocery Retailers’ Last-Mile Value Proposition: A Sustainable Business Model Perspective. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2022, 7, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, K.; Bjerre, M.; Bisgaard, T.; Almasi, A.M.; Damgaard, E. Green Business Model Innovation: Empirical and Literature Studies; Nordic Innovation Publication: Oslo, Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F. Towards a Conceptual Framework of ‘Business Models for Sustainability’. In Proceedings of the Knowledge, Collaboration & Learning for Sustainable Innovation, 14th European Roundtable on Sustainable Consumption And Production (ERSCP) & 6th Environmental Management for Sustainable Universities (EMSU), Delft, The Netherlands, 29 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. Design Thinking to Enhance the Sustainable Business Modelling Process—A Workshop Based on a Value Mapping Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1218–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.E.; Seitanidi, M.M. Collaborative Value Creation: A Review of Partnering between Nonprofits and Businesses: Part I. Value Creation Spectrum and Collaboration Stages. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 726–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes De Oliveira, S.M.; Leal, S.; Vivas, C.; Nascimento, J.A.M.d.; Barradas, L.C.; São João, R.; Ferreira, M.R.; Passarinho, A.; Rodrigues, A.I.; Amaral, M.I.C.; et al. Volto Já—Senior Exchange Program: From Idea to Implementation. In Management, Technology and Tourism: Social Value Creation—Proceedings of the Icomtt2020 International Conference, Instituto Politécnico de Santarém, Santarém, Portugal 6–7 February 2020; Leal, S., Nascimento, J., Vivas, C., Barradas, L.C., Oliveira, S., Eds.; Instituto Politécnico de Santarém: Santarém, Portugal, 2021; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ollár, A.; Femenías, P.; Rahe, U.; Granath, K. Foresights from the Swedish Kitchen: Four Circular Value Opportunities for the Built Environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khripko, D.; Morioka, S.N.; Evans, S.; Hesselbach, J.; de Carvalho, M.M. Demand Side Management within Industry: A Case Study for Sustainable Business Models. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 8, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyen, A.; Beckmann, M.; Mueller, S.; Dees, J.G.; Khanin, D.; Krueger, N.; Murphy, P.J.; Santos, F.; Scarlata, M.; Walske, J.; et al. Social Entrepreneurship and Broader Theories: Shedding New Light on the ‘Bigger Picture’. J. Soc. Entrep. 2013, 4, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, H.; Lewis, J.; Turley, C.; Focus Groups. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students & Researchers; Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C., Ormston, R., Eds.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 211–242. [Google Scholar]

- Portuguese Social Security Institute. Centro De Dia—Questionários De Avaliação Da Satisfação [Day Centre—Satisfaction Assessment Questionnaires]. 2010. Available online: http://www.seg-social.pt/documents/10152/13701/gqrs_centro_dia_questionarios/16bb8cbd-a12b-4f34-96fe-bf2cb52e3b9a (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- Portuguese Social Security Institute. Centro De Dia—Manual De Processos-Chave [Day Centre—Key Processes Manual]. 2010. Available online: http://www.seg-social.pt/documents/10152/13694/gqrs_centro_dia_processos-chave/439e5bcd-0df3-4b03-a7fa-6d0904264719 (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- Portuguese Social Security Institute. Estrutura Residencial Para Idosos—Questionários De Avaliação Da Satisfação [Residential Structure for the Elderly—Satisfaction Assessment Questionnaires]. 2007. Available online: http://www.seg-social.pt/documents/10152/13880/gqrs_lar_estrutura_residencial_idosos_questionarios/7c26e4f4-785e-4428-ac29-7ec2443b2ba8 (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- Power, M. Development of a Common Instrument for Quality of Life. In Eurohis: Developing Common Instruments for Health Surveys; Nosikov, A., Gudex, C., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, A. Measuring Happiness with a Single-Item Scale. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2006, 34, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, J.; Abdallah, S.; Steuer, N.; Thompson, S.; Marks, N.; Aked, J.; Cordon, C.; Potts, R. National Accounts of Well-Being: Bringing Real Wealth onto the Balance Sheet; New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Woo, E.; Uysal, M. Tourism Experience and Quality of Life among Elderly Tourists. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Pritchard, A.; Sedgley, D. Social Tourism and Well-Being in Later Life. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.M. A Positive Theory of Social Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Haugh, H.; Göbel, M.; Leonardy, H. Pathways to Lasting Cross-Sector Social Collaboration: A Configurational Study. J. Bus. Ethics. 2022, 177, 613–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelini, L. Social Innovation and New Business Models: Creating Shared Value in Low-Income Markets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Geissinger, A.; Laurell, C.; Öberg, C.; Sandström, C. How Sustainable Is the Sharing Economy? On the Sustainability Connotations of Sharing Economy Platforms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Schilke, O.; Ullrich, S. Strategic Development of Business Models: Implications of the Web 2.0 for Creating Value on the Internet. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden-Fuller, C.; Haefliger, S. Business Models and Technological Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzembacher, D.E.; Raudsaar, M.; De Barcellos, M.D.; Mets, T. Business Models’ Innovations to Overcome Hybridity-Related Tensions in Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).