1. Introduction

In the contemporary business landscape, marked by intense competition, rapid digital transformation, and increasing pressure for sustainable development, companies face mounting challenges in sustaining competitive advantages using only internal resources [

1,

2]. The accelerating pace of change demands businesses to adopt new, more collaborative strategies to achieve long-term success in knowledge-intensive and sustainability-oriented markets [

3]. As a result, firms are transitioning from fully integrated models toward more socially cohesive, open, and digitally connected organizational structures. This shift has led to a significant rise in inter-company collaborations, fostering the emergence of hybrid organizational forms and intricate networked structures [

4]. In this evolving environment, businesses increasingly recognize the importance of engaging within entrepreneurial ecosystems, which are dynamic networks of interconnected actors (such as firms, institutions, and individuals) that foster innovation, digital knowledge exchange, and sustainable value co-creation [

5,

6]. Establishing strong, creative connections within these ecosystems enhances a company’s potential for survival and growth amid globalized market pressures [

7]. Consequently, organizations are moving beyond traditional value chain models to embrace more flexible, collaborative, and innovation-driven frameworks, often called value networks [

8]. These networks facilitate superior economic and environmental value generation by fostering dynamic exchanges among businesses, suppliers, customers, strategic allies, and other stakeholders across multiple levels: micro, meso, and macro [

9]. The complexity of contemporary economic, technological, cultural, and ecological environments demands organizational innovation as a key response [

10,

11]. Within entrepreneurial ecosystems, innovation thrives through continuous interaction and collaboration among diverse actors [

12]. Scholars argue that innovation-oriented firms should learn from collaborations and continually refine their methods of engaging with partners, leveraging digital transformation and open innovation mechanisms to foster sustained competitive advantages [

13]. This perspective has sparked ongoing debates on the need for more open, digitally enabled collaboration approaches, expanding the classical organizational cooperation tools [

14]. As companies seek novel ways to collaborate, the traditional barriers between and within organizations are becoming increasingly fluid, broadening the scope and impact of strategic partnerships [

15]. A crucial aspect of this transformation involves how businesses combine internal and external resources to create superior, sustainable value [

16]. Crowdsourcing has emerged as a fundamental mechanism for achieving this goal [

17]. Based on the premise that a diverse group of participants can generate better outcomes than a homogeneous team, crowdsourcing harnesses decentralized contributors’ collective intelligence and problem-solving capabilities [

18]. Digitalization has accelerated this shift, offering platforms that enable firms to leverage crowd efficiency and access valuable external knowledge [

17]. Emerging digital technologies now reframe leadership practice by converting data abundance into strategic foresight. Large-scale analytics supported by artificial intelligence (AI) provide leaders with near-real-time, sustainability-oriented dashboards that accelerate evidence-based decision-making and shorten innovation cycles [

19]. Nevertheless, AI does not create a defensible advantage; recent theory indicates that performance differentials arise only when firms combine algorithmic capabilities with distinct human competencies, such as sense-making and ethical judgment [

20]. Effective digital leadership, therefore, hinges on orchestrating human–AI complementarities that balance economic, social, and environmental goals, rather than pursuing efficiency in isolation. Blockchain, in turn, is redefining how strategic alliances are governed. Its decentralized ledger and self-executing smart contracts automate compliance, lower transaction costs, and create an immutable audit trail, replacing interpersonal trust with algorithmic transparency [

21]. By hard-wiring reliability and incentive alignment into data-sharing routines, blockchain mitigates opportunism. It expands the design space for co-innovation across organizational boundaries—a shift that alters boundary-setting and control structures in alliances [

22]. Embedding this dual technological lens clarifies that digital transformation is no longer confined to generic platforms, but actively reshapes the loci of trust, control, and value creation, thereby reinforcing this article’s contribution to the leadership–sustainability nexus.

By assembling rare, inimitable, complementary relational resources, crowdsourcing fosters disruptive collaborative environments within digital ecosystems and conventional business networks.

Traditional business models, grounded in resource accumulation theory, essentially analyzed companies in isolation, emphasizing the internal development of unique, non-transferable assets. However, recent research challenges this perspective, arguing that companies can effectively leverage external resources through open innovation and networked collaborations [

4]. This shift is particularly relevant to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which often face scale, scope, and technological capability constraints. Business networks allow SMEs to overcome resource limitations, acquire critical knowledge, and build social capital [

23]. Social capital, the sum of resources accessible through durable mutual recognition and trust networks, underscores the importance of developing strategic connections. These networks enable SMEs to tap into external expertise, access new markets, and share technological investments that might otherwise be prohibitively expensive [

24]. By cultivating a strong network position, companies can mitigate internal deficiencies and enhance their innovation capabilities [

25,

26,

27]. As firms integrate into broader, digitally mediated collaborative ecosystems, they unlock synergies that drive shared economic, technological, and sustainable advancements [

28]. In this context, trust and mutual commitment are critical in facilitating effective collaboration. Experiential learning, where partners gain deeper insights into each other’s capabilities and intentions over time, strengthens these relationships [

27]. Trust-based collaborations reduce the need for formal controls, allowing companies to adapt strategically to changing market conditions. Informal social coordination is often more efficient than rigid hierarchical structures in fostering strategic change [

29,

30]. Since strategic decision-making involves positioning a company within an uncertain future, long-term relationships built on trust and shared learning can significantly reduce risks [

31,

32]. Collaboration is thus a crucial component of modernization strategies driven by emerging digital technologies and sustainability goals [

33]. Collaborative networks accelerate innovation by fostering the exchange of ideas and resources, providing businesses with a competitive edge in fast-moving and environmentally conscious markets [

34,

35]. The literature in this field consistently highlights the necessity of network-building and resource-sharing as key drivers of innovation. The shift from traditional, self-contained organizational models to dynamic, collaborative, and digital ecosystems enables firms, particularly SMEs, to overcome internal limitations, boost competitiveness, and contribute to broader economic and ecological sustainability. Unlike larger firms, SMEs often face significant constraints in terms of financial resources, managerial capacity, and alliance experience. These limitations make access to external networks and simplified alliance structures particularly crucial for their innovation efforts [

4]. Tailored approaches, such as flexible governance mechanisms, trust-based collaboration, and context-specific logistical integration, can assist SMEs in engaging more effectively in strategic partnerships [

24]. Additionally, digital platforms and crowdsourcing mechanisms increasingly support successful collaborative strategies, allowing companies to co-create value on an unprecedented scale. Integrating universities and research institutions into these networks further strengthens the alignment between scientific advancement and sustainable economic growth, positioning businesses to drive technological and organizational innovation.

Several literature reviews have examined the intersection of leadership and strategic alliances, exploring the role of leadership in forming, managing, and sustaining collaborative partnerships [

36]. For instance, studies analyzing strategic alliances through transaction cost economics, resource-based views, and knowledge-based perspectives suggest that no single theoretical framework fully explains alliance formation [

37]. Other research categorizes alliances into life-cycle stages, emphasizing leadership’s role in fostering trust, communication, and alignment [

38]. Moreover, leadership plays a crucial role in leveraging dynamic capabilities within strategic alliances, influencing firms’ ability to achieve competitive advantages [

39,

40]. Systematic reviews on international strategic alliances highlight leadership’s impact on cross-border collaboration success [

41,

42]. Despite these insights, the existing literature often overlooks the specific leadership styles and behaviors that drive alliance effectiveness and long-term success [

43,

44]. Future research should integrate leadership theories more comprehensively to enhance our understanding of strategic alliance dynamics.

By deepening our knowledge of collaboration, networking, and leadership in strategic alliances, businesses can refine their approaches to co-creation and innovation. As organizations embrace digital platforms, open innovation, and knowledge-sharing frameworks, trust, commitment, and experiential learning will remain central to successful partnerships [

15,

45,

46]. Ultimately, the ability to navigate and leverage these evolving entrepreneurial ecosystems will determine a company’s long-term success in an increasingly interconnected, digital, and sustainability-driven world.

Considering the above, this paper aims to enhance our understanding of two key areas and their relationship, specifically exploring how different leadership approaches and actions influence strategic alliances’ dynamics and sustain success. Accordingly, this paper will address the following research questions: What does the literature reveal about the impact of leadership approaches and actions on the success of strategic alliances? Furthermore, what are the most prominent themes that connect and are most strongly associated with the two leadership and strategic alliances clusters?

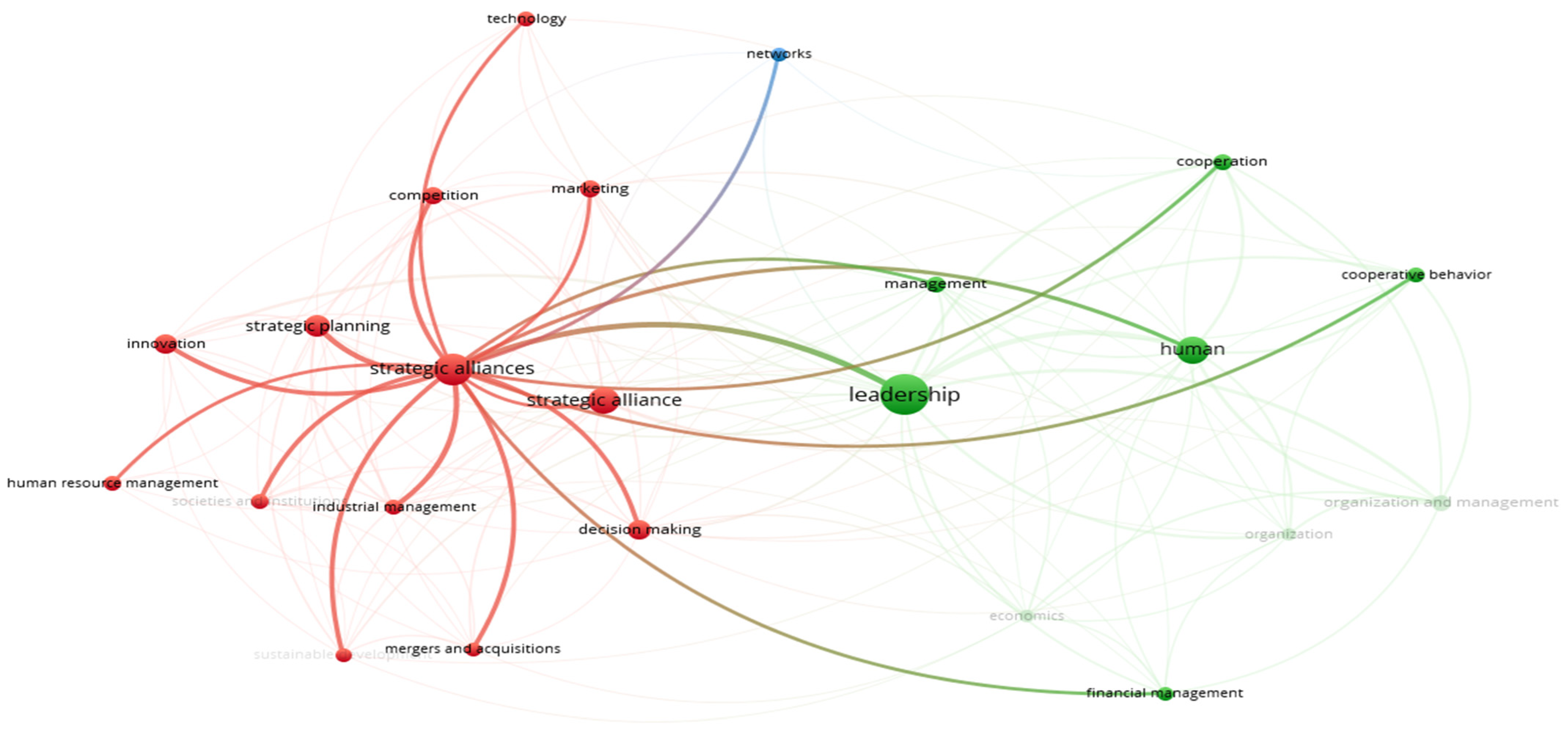

To achieve the objectives of this study and effectively address previously identified gaps in the literature regarding the relationship between leadership behaviors and strategic alliances, we conducted a rigorous literature review of 86 peer-reviewed articles published between 1992 and 2024. Our goal was to thoroughly map and analyze existing knowledge on how leadership dynamics influence strategic alliances’ formation, management, and sustainability within entrepreneurial ecosystems. We employed a bibliometric analysis approach to complement the thematic review, specifically utilizing co-occurrence mapping techniques to visually illustrate connections and relationships among the most relevant research topics. This analysis allowed us to identify two distinct yet interconnected thematic clusters: one primarily focused on various dimensions and styles of leadership (Cluster 1), and another concentrated on factors associated with the creation, governance, and management of strategic alliances (Cluster 2). These clusters provided a structured framework to further examine how leadership and strategic alliances collectively contribute to innovation, digital transformation, and sustainable competitive advantage.

The structure of this article is organized as follows: In

Section 2, we present and justify the methodological approach adopted. In

Section 3, we synthesize the key findings derived from the reviewed publications.

Section 4 is dedicated to exploring the two clusters of studies that represent the central research themes in the field. Finally,

Section 5 concludes by highlighting the main insights and proposing directions for future research.

2. Method

Following recent developments in bibliographic research—e.g., [

47,

48,

49]—a rigorous literature review supported by bibliometric analysis based on the visualization of similarities technique [

50,

51,

52] was performed to provide an accurate analysis of leadership and strategic alliances.

The first step involved a comprehensive search of the Scopus database. The choice of selecting the Scopus database was to cover the more impactful articles in the area that could contribute to answering research questions. Scopus has more than 20,000 peer-reviewed journals, including, but not limited to, the following reputed publishers: Elsevier, Emerald, Taylor and Francis, and Springer. WoS only covers 12,000 journals indexed in ISI (International Scientific Indexing) journals [

53]. This choice also aligns with prior literature reviews in strategic management and organizational studies [

54].

A panel of experts was consulted to define the search criteria, ensuring the selection of relevant terms. The search was conducted using the terms “leadership” and “strategic alliances” within titles, abstracts, and keywords. This initial query, executed in January 2025, resulted in 214 references.

The initial step of this systematic literature review involved identifying relevant documents to ensure the reliability and overall quality of the dataset. To this end, the search was restricted exclusively to specific types of scholarly publications, namely peer-reviewed journal articles, books, book chapters, and conference papers, which initially yielded 178 potentially relevant documents. Subsequently, further filtering was performed to enhance data relevance, reduce dispersion, and mitigate potential bias. In this phase, documents belonging to subject areas outside this study’s defined scope, particularly those related to Health and other related fields, were deliberately excluded. As a result, the dataset was narrowed down to 132 scientific articles explicitly focusing on the areas of Business, Management and Accounting, Social Sciences, Economics, Econometrics and Finance, and Decision Sciences. Finally, after a thorough screening, 46 additional documents were excluded either because their full texts were unavailable due to access restrictions like publisher embargoes or subscription-based availabilityor because their thematic focus did not adequately align with the research objectives.

This careful selection resulted in a final dataset comprising 86 documents (61 articles, 3 books, 7 book chapters, and 15 conference papers), forming the basis for the subsequent bibliometric analysis and qualitative synthesis presented in this paper (

Figure 1).

The second step involved identifying research clusters through bibliometric analysis using the VOSviewer 1.6.8 tool. VOSviewer facilitates the visualization of co-occurrence relationships between research topics, authors, and references. The software constructs a two-dimensional map where the relative distance between nodes reflects the degree of similarity in cited references. The visualization of similarities allows for clustering based on shared bibliographic data [

51]. The tool also generates a cluster density view, where each cluster is assigned a unique color based on a weighted average of item density [

51]. In this analysis, two primary clusters emerged, representing distinct thematic areas within the leadership and strategic alliances literature.

The final step involved qualitatively examining the two clusters to ensure thematic coherence. In line with the systematic literature review methodology [

55,

56], the articles within each cluster were read and analyzed to confirm their relevance to the identified research streams.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 adjusted flowchart of the selection process for included studies [

57].

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 adjusted flowchart of the selection process for included studies [

57].

3. Findings

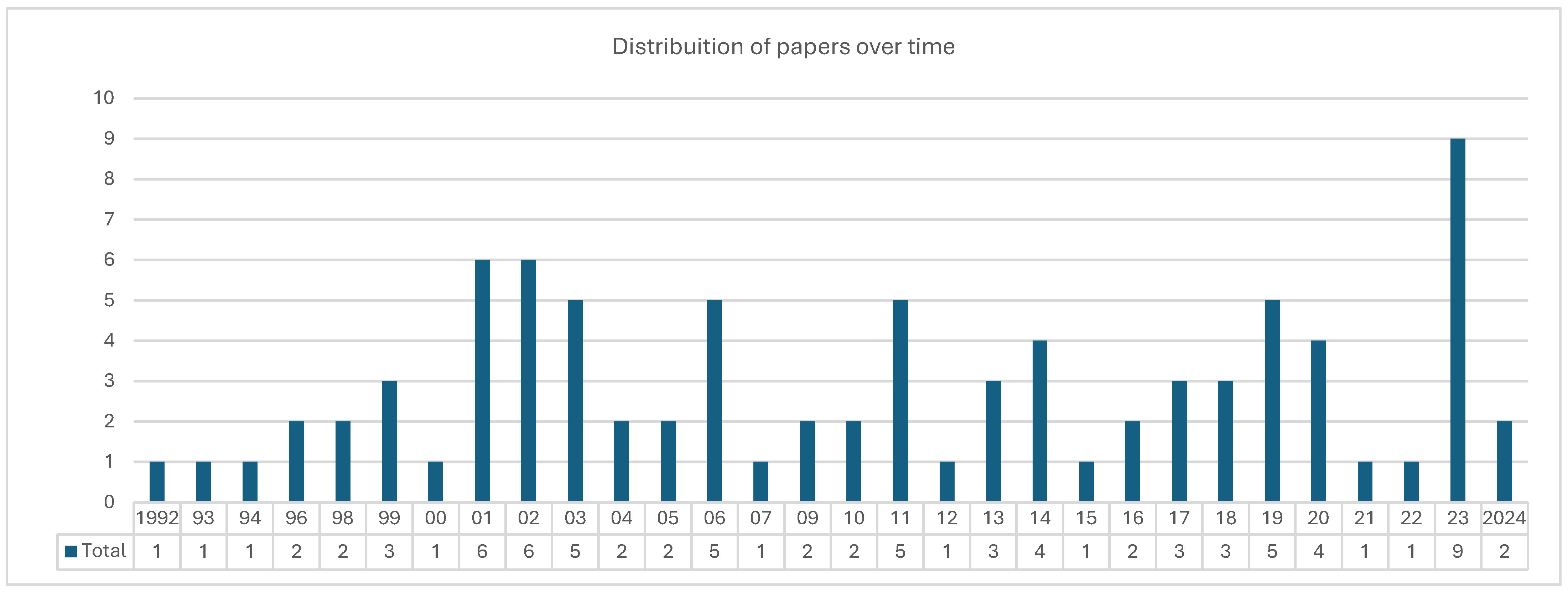

The analysis of the distribution of papers over time, as shown in

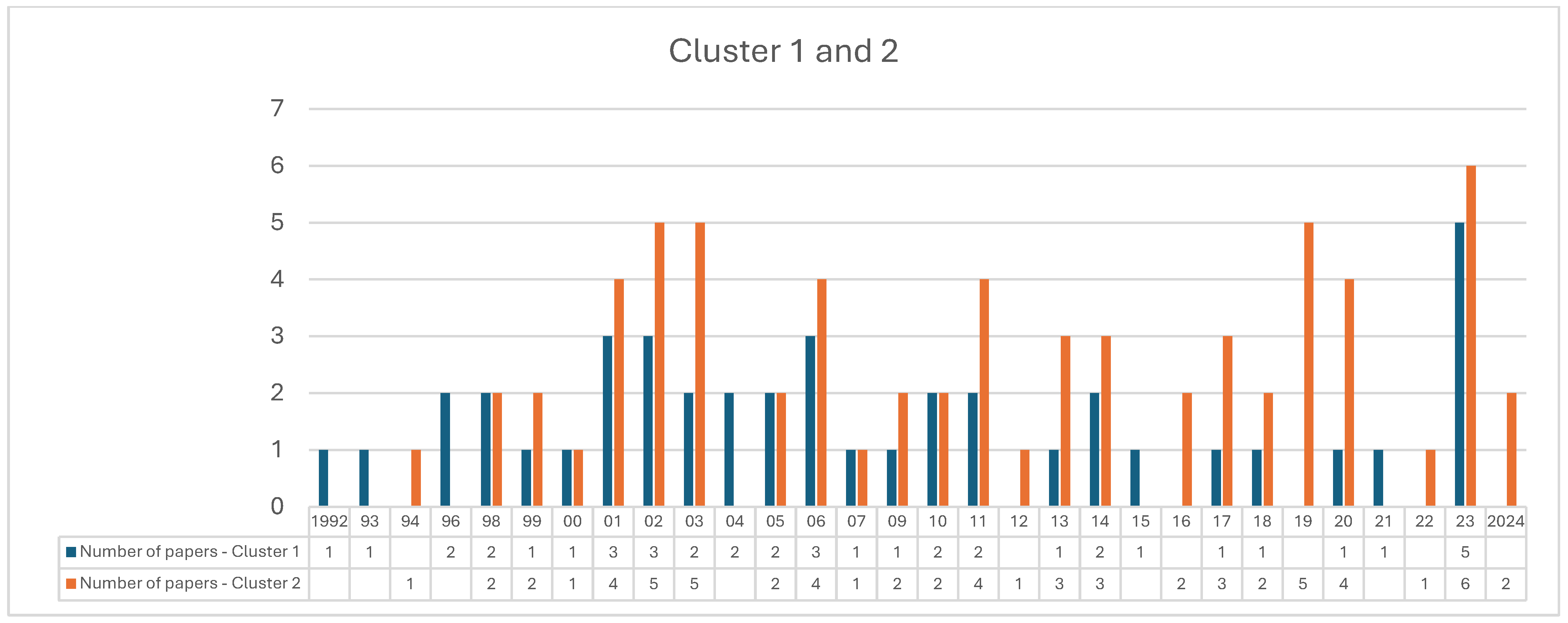

Figure 2, highlights a fluctuating yet increasing trend in research on leadership and strategic alliances. The data span from 1992 to 2024, demonstrating periods of heightened academic interest interspersed with phases of lower activity. The analysis of publication trends, as illustrated in

Figure 2, reveals a fluctuating yet steadily increasing academic interest in the topic over time. The landscape research comprises two distinct clusters, each representing different thematic approaches to the subject. Scholarly contributions to this field emerged in 2001, with two papers in Cluster 1 and one paper in Cluster 2. In the following years, the number of publications remained relatively low but exhibited periodic spikes. Notable surges in research activity occurred in 2001, 2002, 2003, 2011, 2019, and 2023, indicating moments of heightened scholarly engagement with the topic. A broader view of the distribution of papers over time confirms a general upward trajectory, reinforcing the increasing relevance of leadership and strategic alliances. The dataset shows fluctuations in research output, with some years witnessing substantial contributions while others experienced a decline. Despite these variations, a clear trend toward greater academic attention is evident, particularly in recent years. The most significant growth in research production occurred in 2023, marking the highest scholarly output recorded in the dataset. This sharp increase suggests a growing recognition of the importance of leadership in strategic alliance success, likely driven by external influences such as policy shifts, corporate sustainability initiatives, and global economic trends. These temporal fluctuations can also be interpreted in light of significant global events that have influenced research priorities in this area. Following the events of 9/11, there was increased attention to interorganizational resilience and crisis leadership, as evidenced by the rise in publications during 2001–2002. In 2011, the aftermath of the global financial crisis sparked renewed interest in alliance governance during economic uncertainty. Most significantly, the post-pandemic context of 2023—characterized by digital transformation, supply chain disruptions, and geopolitical instability—has led to a surge in research focusing on strategic partnerships and agile leadership. The recent literature further highlights the importance of alliance capabilities in improving organizational performance amid such turbulence [

14,

39,

40].

Two research clusters showcase the diversity of academic perspectives, emphasizing the multifaceted and evolving nature of the relationship between leadership and strategic alliances. The continued increase in publications, notably the peak in 2023, reflects a sustained and growing interest in the topic. This trend indicates a promising potential for future research to further refine theoretical frameworks and enhance empirical analyses, particularly in response to the complex and dynamic external environments that organizations increasingly encounter. Two research clusters highlight the diversity of academic perspectives, underscoring the multifaceted and evolving nature of the relationship between leadership and strategic alliances. The continued rise in the number of publications, particularly the peak in 2023, indicates a sustained interest in the subject, with promising potential for future studies to refine theoretical frameworks and empirical analyses further.

The citation impact of the analyzed publications reveals an average of 12 citations per article, with a median of 6, indicating that, although some publications have received a considerable number of citations, most tend to be cited more modestly. When considering the journals, the average citation count per journal was 20, with a median of 6. This suggests that, while some journals have contributed highly cited articles, many have a more balanced or lower number of citations. These results reflect the variability in citation impact, which is common in fields of research that are constantly evolving.

From the citation analysis of academic journals, the

Harvard Business Review stands out as the most influential, with 2503 citations for a single publication. Following this, the

Journal of Business Venturing has received 308 citations, while

Research Policy has accumulated 91 citations. Other journals, such as the

Academy of Management Executive and the

International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, appear among the most cited, with citations of 84 and 80, respectively (

Table 1).

Despite the lower overall citation count, journals such as Management Research Review and R&D Management have published relevant contributions. The presence of diverse academic outlets underscores the interdisciplinary nature of research on leadership and strategic alliances, further reinforcing its growing academic and managerial relevance.

Looking at the corresponding author’s country in

Table 2, the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom emerged as the leading contributors to research on strategic alliances and leadership. The United States has 25 publications, significantly ahead of Japan and the United Kingdom, each contributing 8.

Following these, Australia and India, with six publications, also demonstrate a strong research presence in these topics. Their engagement suggests that the study of leadership and strategic alliances is concentrated in North America and Europe and expands in the Asia–Pacific region.

Surprisingly, Spain and Italy have strong academic contributions in management and business research, but do not rank among the top five. Instead, they appear lower in the ranking, with Spain contributing 3 publications and Italy 2. Similarly, Indonesia (4), New Zealand (2), and Sweden (2) have made contributions to this research area, reflecting its growing global importance.

The United States’ dominance in publication volume aligns with its strong business research infrastructure. However, the notable contributions from Japan, the United Kingdom, and Australia highlight the increasing global recognition of these topics. The presence of European and Asian countries further emphasizes the broad applicability of strategic alliances and leadership research, shaping contemporary business practices and organizational strategies worldwide. This geographic diversity also suggests the influence of various cultural and institutional contexts on how alliances are formed and led. For instance, leadership in Anglo–American settings often emphasizes formal contracts and individual accountability, while East Asian contexts tend to prioritize relational trust, consensus-building, and long-term orientation [

43]. Such differences may shape both the theoretical framing and practical execution of strategic alliances across regions.

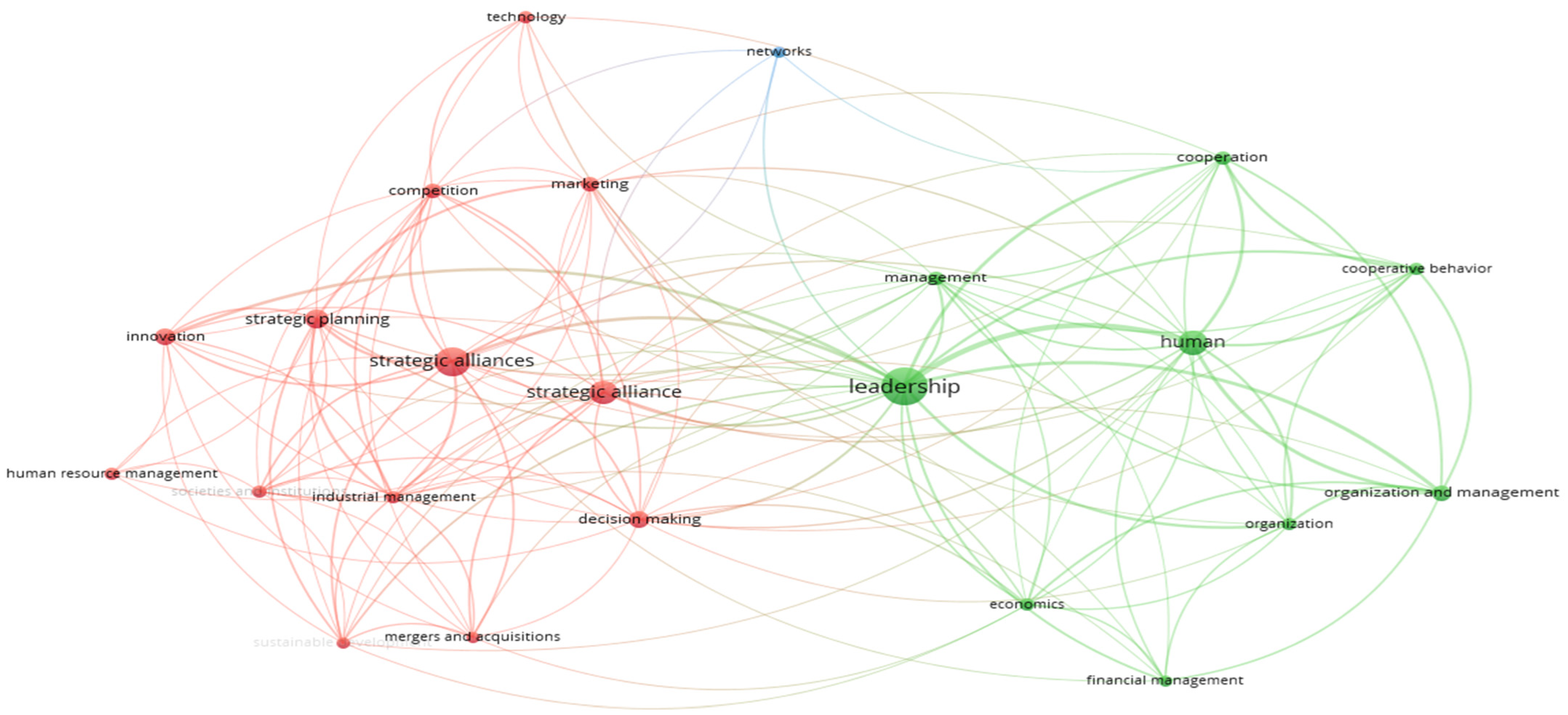

The Strategic Alliances cluster is oriented around critical themes such as strategic planning, intricate decision-making processes, and competitive dynamics. It also addresses aspects of industrial collaboration and partnership governance. These elements collectively highlight the cluster’s connections to overarching business strategies, collaborative resource-sharing mechanisms, and competitive market positioning [

58]. Furthermore, this cluster indicates the importance of formal and informal governance structures and trust-building processes, which are crucial for managing uncertainties and ensuring sustained alliance performance, particularly in rapidly evolving, innovation-driven, and digitally connected environments.

In contrast, the Leadership cluster covers many themes, including management practices, inter-organizational cooperation, organizational behavior, financial oversight, and ethical considerations in leadership approaches [

59]. This cluster underscores leadership’s pivotal role in fostering organizational influence, effective internal and external coordination, and overall business efficiency and adaptability. It also emphasizes transformational leadership approaches that encourage innovation, shared vision, and resilience—key elements for navigating complex, sustainability-oriented ecosystems shaped by digital transformation and open innovation.

The extensive and multifaceted interconnections between these two clusters demonstrate the reciprocal relationship, where leadership significantly shapes the success and effectiveness of strategic alliances. For example, transformational leaders often encourage open communication and trust, which enhances collaboration within alliances. Conversely, strategic alliances serve as platforms for developing leadership competencies, offering leaders valuable experiential insights into diverse organizational cultures, management styles, and strategic decision-making contexts, such as exposure to cross-cultural management practices or innovative problem-solving techniques from partner organizations. Key bridging components, including collaborative decision-making processes, knowledge-sharing practices, communication transparency, and trust-building, are essential in strengthening the linkage between strategic planning activities and leadership effectiveness [

60].

Overall, this network visualization clearly emphasizes the inherent interdependence of leadership and strategic alliances, which is significant as it enables organizations to effectively adapt to market changes, foster innovation, and achieve sustainable competitive advantages [

61]. It highlights how specific leadership behaviors, decision-making strategies, and managerial practices are essential in forming and managing alliances and ensuring sustained success within dynamic, digitally enabled, and innovation-oriented business environments [

62]. The analysis underscores the need to integrate strong leadership frameworks and robust strategic partnership management strategies to thrive in increasingly interconnected, open entrepreneurial ecosystems.

4. Clusters Insights

The bibliometric analysis of Leadership and Strategic Alliances underscores their critical impact on organizational success within dynamic and sustainability-oriented entrepreneurial ecosystems (

Figure 3). The cluster focused on Leadership primarily addressed managerial influence, decision-making processes, organizational behaviors, communication strategies, and the cultivation of corporate culture. Leaders are pivotal in shaping organizational practices and facilitating effective internal and external interactions. Their actions significantly influence employee performance, innovation capacity, commitment, and overall organizational health.

Conversely, the Strategic Alliances cluster concentrates on inter-organizational collaborations, governance structures, partnership dynamics, resource-sharing strategies, and mechanisms for collective problem-solving. Alliances enable organizations to pool resources, share knowledge, co-develop solutions, and effectively manage risks and opportunities that arise in increasingly competitive, digitalized, and sustainability-driven environments.

Although these clusters have distinct thematic focuses, they are closely interconnected. Effective Leadership significantly influences alliance performance by building trust, ensuring clear communication, and aligning strategic objectives among partners. Conversely, strategic alliances provide leaders with valuable experiences that enhance their strategic thinking and managerial abilities through exposure to various organizational cultures, innovation practices, and digital collaboration tools [

63,

64]. The reciprocity between leadership and strategic alliances creates a virtuous cycle whereby strong leadership enhances the quality and outcomes of alliances, and effective alliances further refine leadership competencies in innovation and change management. Over time, research within these clusters has evolved substantially, marked by key milestones such as the shift from hierarchical to transformational leadership models in the early 2000s and increased emphasis on digital governance and trust-based frameworks in strategic alliances during the last decade [

65]. Leadership studies have transitioned from traditional hierarchical frameworks toward more dynamic, participatory, and transformational leadership approaches, reflecting broader organizational, technological, and environmental shifts. These contemporary approaches emphasize adaptability, proactive change management, sustainability awareness, the importance of digital knowledge-sharing, and the empowerment of employees within innovation-driven organizations [

39]. Concurrently, research on strategic alliances has increasingly highlighted the necessity of effective governance mechanisms, including the balance between formal contractual agreements and informal relational trust. Scholars have also emphasized trust-building among partners, cultural alignment, and the crucial role of inter-organizational networks in facilitating open innovation, co-creation of sustainable value, and enhanced resilience to external shocks.

The interaction between leadership and strategic alliances indicates that organizations striving for long-term success must integrate robust leadership models with strategic alliance management practices to build sustainable competitive advantages [

66]. This integration helps organizations to enhance their resilience against disruptions, adaptability to market shifts, and capacity for digital innovation, social impact, and long-term sustainable growth. Moreover, emerging research underscores the critical role of digital platforms and crowdsourcing mechanisms in strengthening alliances by facilitating efficient communication, transparency, and collaborative knowledge exchange. For instance, digital platforms enable partners to share real-time data, improving decision-making speed and accuracy. At the same time, crowdsourcing helps organizations to tap into diverse external expertise, enhancing innovative problem-solving capabilities and reducing the risk of internal biases [

4]. Thus, organizations that effectively combine transformative leadership approaches with strategic alliances and digital open innovation tools are better positioned to thrive in contemporary entrepreneurial ecosystems, where sustainability, adaptability, and interconnectivity define the path to competitive and collaborative success [

67,

68,

69].

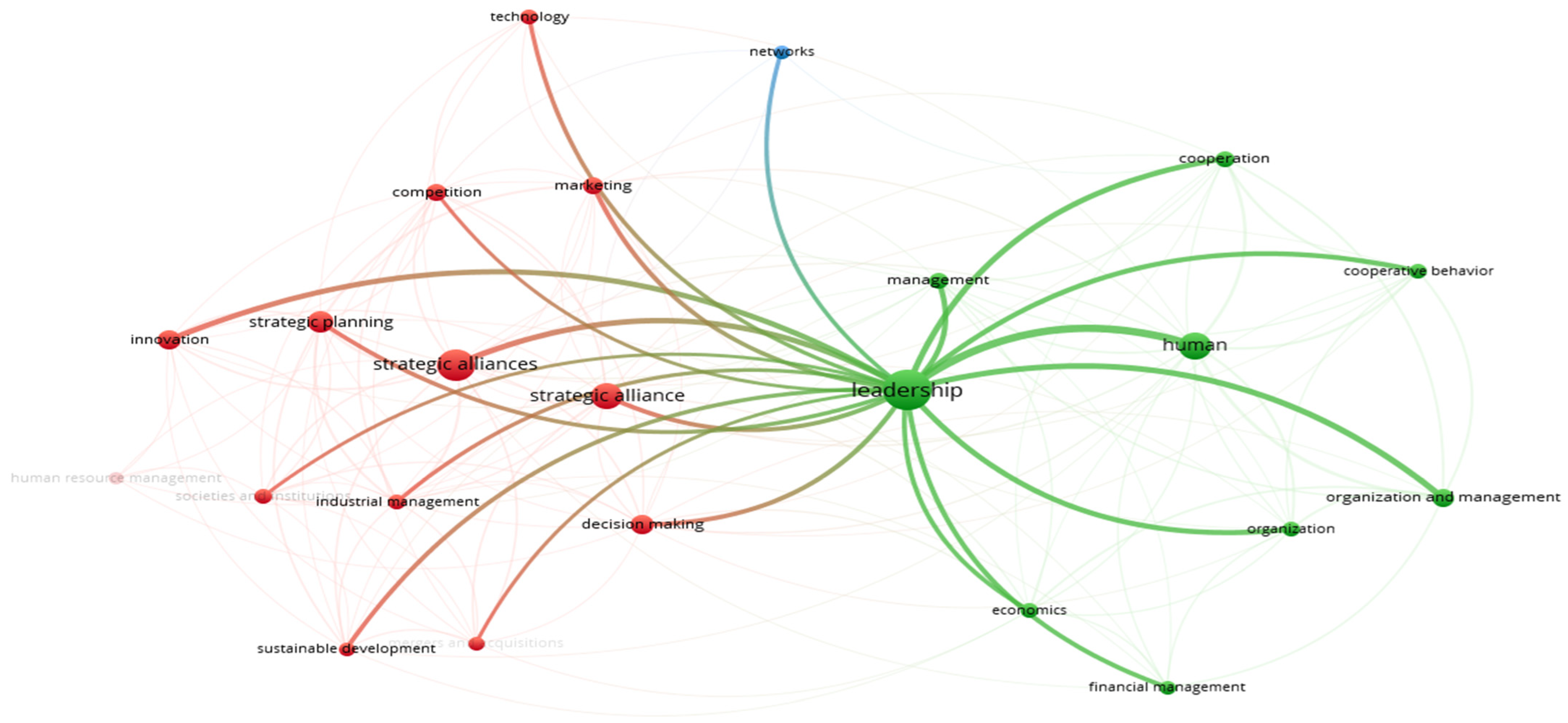

4.1. Cluster 1 (Green)—Leadership

The Leadership cluster explores various leadership models and their impact on organizational success, explicitly focusing on their role in shaping and sustaining strategic alliances within entrepreneurial and innovation-driven ecosystems (

Figure 4). Research suggests that leadership styles significantly influence alliance outcomes, affecting collaboration, digital knowledge-sharing, and overall strategic performance.

Transformational leadership, which is characterized by vision, inspiration, and adaptability, has been consistently linked to stronger alliance performance. Leaders who embrace this style create an environment that encourages trust, shared objectives, innovation, and long-term commitment among alliance partners [

70,

71]. This approach enables organizations to navigate the complexities of strategic partnerships by fostering open communication, digital collaboration, and innovative problem-solving. Transformational leaders also play a crucial role in aligning diverse organizational cultures and mitigating conflicts, including challenges related to diversity in senior management, which can affect strategic change and firm performance [

72,

73,

74]. In contrast, transactional leadership, which focuses on structured processes, formalized agreements, and reward-based performance, may be effective in alliances requiring high control and predictability levels. However, this style tends to be less effective in fast-changing environments shaped by digital disruption and sustainability demands, where flexibility and adaptability are critical [

75]. Transactional leaders emphasize efficiency and compliance, making their approach suitable for alliances with well-defined roles and contractual obligations, but less suitable for partnerships that demand open innovation and rapid adaptation [

76].

Another perspective highlighted in the literature is distributed leadership, where decision-making authority is shared across multiple levels of an organization. This model promotes a culture of flexibility and inclusivity, enabling greater stakeholder participation and fostering sustainable innovation within strategic alliances [

77]. By leveraging the collective expertise of various internal and external contributors, distributed leadership helps organizations to respond more effectively to emerging challenges and opportunities—particularly in complex, digitally enabled, and knowledge-intensive collaborations [

36,

78]. Beyond leadership styles, research underscores the broader influence of leadership on strategic alliances. Effective leaders facilitate knowledge transfer and organizational learning, fostering an environment where best practices and innovative ideas can be shared seamlessly across partner organizations [

4,

79]. Strong leadership structures contribute to developing trust-based relationships essential for long-term collaboration, digital co-creation, and sustainable value generation [

80]. Moreover, leadership is critical in shaping corporate governance and organizational culture—key determinants of alliance success in today’s interconnected, sustainability-focused business landscape. Ethical leadership, for instance, has been associated with enhanced trust and reduced opportunistic behavior among partners, fostering more resilient and responsible alliances [

81]. Leaders who prioritize ethical decision-making and corporate social responsibility (CSR) contribute to alliances that are financially viable and aligned with broader societal and environmental goals. The intersection between leadership and CSR has emerged as a key research theme, highlighting how socially responsible leaders can influence strategic alliances’ formation, evolution, and longevity [

82,

83]. Studies suggest that leaders who integrate sustainability principles into their decision-making are likelier to establish partnerships emphasizing long-term value creation over short-term financial outcomes [

84]. This perspective reflects the evolving expectations placed on businesses to act as responsible innovation agents, extending their impact beyond organizational boundaries [

23].

Overall, the role of leadership in strategic alliances extends beyond direct managerial actions to encompass broader cultural, ethical, and structural influences. As businesses increasingly participate in complex, interdependent, and digitally mediated partnerships, the ability of leaders to foster trust, drive innovation, and align strategic objectives toward sustainable outcomes will remain a key determinant of alliance success [

85]. Future research should explore how different leadership models interact with alliance structures and how the ongoing digital transformation reshapes leadership effectiveness in strategic, open, and innovation-centric collaborations.

4.2. Cluster 2 (Red)—Strategic Alliances

The Strategic Alliances cluster explores how companies establish and manage partnerships with other firms to achieve long-term competitive advantages and drive innovation within increasingly interconnected and sustainability-oriented markets (

Figure 5). Research indicates that businesses form alliances for various strategic purposes, such as expanding into new markets, accessing cutting-edge technologies, sharing resources, and mitigating risks [

86]. These collaborations enable firms to complement their internal capabilities, enhancing innovation, operational efficiency, and overall market positioning [

87]. However, the success of an alliance is not guaranteed and heavily depends on how it is structured and governed. Studies emphasize the importance of balancing formal governance mechanisms (such as contracts and legal agreements) with relational trust, essential for ensuring long-term stability and agility in digital and open innovation contexts [

88]. Over-reliance on contractual agreements can create rigid structures that limit flexibility and responsiveness. In contrast, lacking formal contracts increases the risk of opportunistic behaviors, misaligned objectives, and partnership failures [

68].

A substantial body of research highlights the role of strategic alliances in fostering knowledge exchange, digital collaboration, and innovation co-creation. Firms that actively participate in alliances often benefit from enhanced learning opportunities as they gain access to external expertise, novel technologies, and unique operational capabilities [

8]. These collaborations accelerate innovation cycles and reduce the costs and risks associated with research and development (R&D). However, achieving effective knowledge transfer requires strong trust-based relationships between partners. Without trust, companies may hoard knowledge, limit the overall benefits of collaboration, and reduce the potential for joint value creation [

30]. Furthermore, cultural differences between alliance partners play a critical role in shaping the dynamics of knowledge sharing. When organizational cultures are misaligned, communication barriers and integration challenges can arise, hindering effective collaboration and reducing the efficiency of knowledge transfer [

27,

89],

Beyond knowledge-sharing, alliances contribute to business resilience, enabling firms to navigate better economic downturns, market volatility, and industry disruptions. Companies embedded in robust alliance networks often demonstrate greater strategic flexibility, as partnerships provide resource-pooling mechanisms, risk-sharing opportunities, and the capacity to adapt swiftly to environmental, technological, or societal shifts [

90]. This resilience is crucial in financial instability, geopolitical uncertainty, or technological transformation, where businesses must pivot quickly to remain competitive.

In an increasingly globalized and digital business environment, strategic alliances have also become vital for firms seeking to expand internationally [

32,

91]. Entering foreign markets poses numerous challenges, including regulatory complexity, unfamiliar consumer behaviors, and competitive pressures. Research suggests that international partnerships help companies to overcome these obstacles by facilitating smoother market entry, offering access to local knowledge, and enabling firms to navigate cultural and institutional differences more effectively [

37,

92]. By leveraging alliances, firms can reduce entry risks, accelerate growth, and establish a more resilient global presence, ultimately reinforcing international competitiveness and sustainable expansion [

93,

94].

4.3. Interconnections Between Clusters

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the Leadership and Strategic Alliances clusters are closely interconnected, highlighting the critical role of effective leadership in the success of strategic alliances. These interconnections also emphasize how alliances contribute to developing advanced leadership competencies, particularly relevant in the context of digital transformation, entrepreneurship, and open collaboration.

While the two clusters are closely linked, they remain conceptually distinct. The Leadership cluster primarily focuses on individual and organizational leadership styles, behaviors, and competencies, whereas the Strategic Alliances cluster emphasizes structural, relational, and strategic mechanisms that govern inter-organizational collaboration.

Effective leadership has been identified as one of the strongest predictors of successful strategic alliances. This relationship is particularly evident in conflict management, trust-building, and aligning strategic goals among diverse and often international partners. For instance, transformational leaders, known for their visionary approach and adaptability, usually manage conflicts more effectively by promoting a shared vision and fostering mutual trust, two elements critical for digital collaboration and sustainable innovation [

40,

95]. Leaders shape alliance dynamics by clearly defining shared objectives, simplifying and accelerating decision-making processes, and promoting transparent, consistent, and open communication among partners [

34]. Their ability to guide collaborative efforts and mediate interpersonal dynamics greatly influences these partnerships’ long-term effectiveness and strategic resilience [

96]. Executives who participate in cross-organizational collaborations benefit from exposure to diverse managerial practices (such as participative decision-making and agile project management), varied cultural perspectives, including cross-cultural communication and negotiation, and complex strategic issues like joint innovation and international expansion. This exposure significantly enhances their leadership capabilities, preparing them to lead in entrepreneurial, dynamic, and increasingly digital environments [

39]. Organizations actively involved in strategic partnerships tend to produce more adaptable, inclusive, and culturally aware leaders proficient in managing uncertainty and innovation across sectors [

70]. This adaptability is crucial in today’s fast-changing global business landscape, shaped by technological disruption, internationalization, and growing sustainability demands [

97]. The reciprocal nature of leadership and strategic alliances thus creates a mutually reinforcing dynamic, a virtuous cycle of continuous development and innovation [

97,

98]. This constant learning process involves ongoing leadership development, cross-sector knowledge exchange, and experiential insights from strategic collaborations, such as joint ventures, co-innovation initiatives, and digital transformation projects. This iterative learning cycle ensures that effective leadership strengthens alliance performance, while active participation in alliances simultaneously expands leadership expertise in managing complex, collaborative ecosystems [

10,

99]

Given the increasing complexity, interconnectivity, and environmental challenges in modern business ecosystems, integrating leadership development and strategic alliance management is essential for achieving sustainable, innovation-led growth. Future research should explore how leadership practices can be adapted to drive value in digital transformation initiatives, open innovation strategies, and cross-sector or international partnerships. Additionally, investigating the conditions under which alliances (especially those involving SMEs and emerging markets) can foster inclusive leadership and long-term sustainability would significantly contribute to building more resilient and future-ready organizations.

5. Conclusions and Future Research

This research emphasizes the vital role of leadership in promoting the success and sustainability of strategic alliances within entrepreneurial ecosystems. To understand this relationship comprehensively, this study adopted a rigorous literature review complemented by bibliometric analysis. Eighty-six articles published between 1992 and 2024 were examined, utilizing the Scopus database to ensure a high-quality and thorough dataset.

The bibliometric analysis was performed using VOSviewer, enabling the visualization of thematic clusters and the interconnections between leadership and strategic alliances. This methodological approach facilitated the identification of key research areas and prevailing trends in the field.

This study’s findings revealed two distinct but interconnected clusters: one centered on leadership and the other on strategic alliances. The Leadership cluster primarily explores various leadership styles and their influence on alliance success. Transformational leadership, characterized by vision and adaptability, has been found to foster collaboration and innovation. In contrast, transactional leadership, which focuses on structured processes, is more effective in formalized alliances but less adaptable to dynamic environments. Additionally, ethical and distributed leadership approaches were essential for trust-building and knowledge-sharing within alliances. The Strategic Alliances cluster, on the other hand, examines how collaborative business partnerships contribute to competitive advantages, market expansion, and innovation. This study found that governance mechanisms, which balance formal agreements and relational trust, are crucial for alliance stability. Furthermore, alliances were identified as key facilitators of knowledge exchange, resource-sharing, and resilience-building, particularly during economic uncertainty.

The temporal analysis of the literature highlights a clear evolution in research focus. Emerging themes include transformational and ethical leadership, the strategic use of digital platforms, open innovation, and sustainability-oriented practices in alliance management. Conversely, declining attention is observed in traditional hierarchical leadership models and resource accumulation approaches. This shift reflects a growing emphasis on adaptability, collaboration, and digital-enabled sustainability within entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Beyond its theoretical contributions, this research presents several practical implications for companies and policymakers.

Regarding companies, the findings highlight the significance of investing in leadership development programs that foster transformational and ethical leadership styles, which are crucial for building long-term, trust-based partnerships. For instance, structured mentoring, experiential learning modules, and cross-cultural leadership labs can equip managers to navigate complex alliances. Companies should also prioritize knowledge-sharing mechanisms and ensure that alliance governance structures balance formal control with relational trust. Additionally, SMEs can utilize strategic partnerships to overcome resource limitations, broaden market reach, and accelerate innovation.

For policymakers, this study emphasizes the necessity of regulatory frameworks that promote business collaboration by reducing bureaucratic barriers and encouraging cross-sector partnerships. Examples include tax deductions for firms participating in public–private alliances and simplifying licensing for innovation consortia. Policies that support digital platforms for open innovation and crowdsourcing can further enhance the effectiveness of alliances [

100,

101]. Public initiatives such as innovation hubs, national knowledge-transfer platforms, or AI-focused business incubators may also strengthen entrepreneurial networks. Additionally, governments should invest in creating entrepreneurial ecosystems, ensuring that infrastructure, funding mechanisms, and educational programs align with the needs of a collaborative, sustainable, and knowledge-driven economy.

Despite these insights, this study acknowledges specific gaps in the literature and proposes several directions for future research. Further empirical studies are needed to clarify the causal link between leadership styles and alliance performance, particularly across diverse cultural and industrial contexts. Additionally, exploring how leadership evolves throughout the alliance life cycle, from formation to maturity, remains a valuable research path. A promising avenue involves examining sustainability-oriented alliances, where leaders must navigate shared environmental and social goals. Future work could also focus on how open innovation practices and ecosystem approaches influence leadership roles and alliance governance in cross-sector collaborations. Also, integrating organizational psychology and network theory perspectives may deepen our understanding of the relational and cognitive dynamics that shape effective, resilient partnerships in complex business environments. Finally, other relevant frameworks (e.g., institutional theory or resource dependency theory) could deepen our understanding of alliance governance or sustainability outcomes.

While this study highlights the potential of leadership and alliances to promote sustainability, it is also crucial to recognize the complexity of translating these efforts into measurable social and environmental outcomes. Strategic alliances can facilitate resource-sharing for green innovation, social inclusion, or regional development; however, these outcomes often involve trade-offs. For instance, sustainability initiatives may require upfront investments that conflict with short-term financial goals, particularly for SMEs. Given their limited internal capacities and financial buffers, SMEs rely heavily on access to external knowledge and flexible, trust-based alliance models that are suited to their scale and adaptability. These customized strategies are key to making sustainability both feasible and strategically beneficial for smaller firms. Leaders must, therefore, manage tensions between economic performance and broader sustainability objectives, aligning strategic intent with long-term value creation and stakeholder legitimacy. Recognizing these dynamics deepens the understanding of sustainability as both a goal and a governance challenge within alliance-based ecosystems.

This work provides added value to ongoing discussions by synthesizing and mapping the fragmented literature on the intersection between leadership and strategic alliances within entrepreneurial ecosystems, a topic of growing relevance in innovation and sustainability studies. Through a comprehensive bibliometric analysis, this study identifies key thematic clusters, leadership styles, and governance mechanisms that drive alliance success and provides a clearer understanding of how specific leadership styles and governance mechanisms contribute to alliance success, resilience, and sustainability.