The Contribution of Chikanda Orchids to Rural Livelihoods: Insights from Mwinilunga District of Northwestern Zambia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

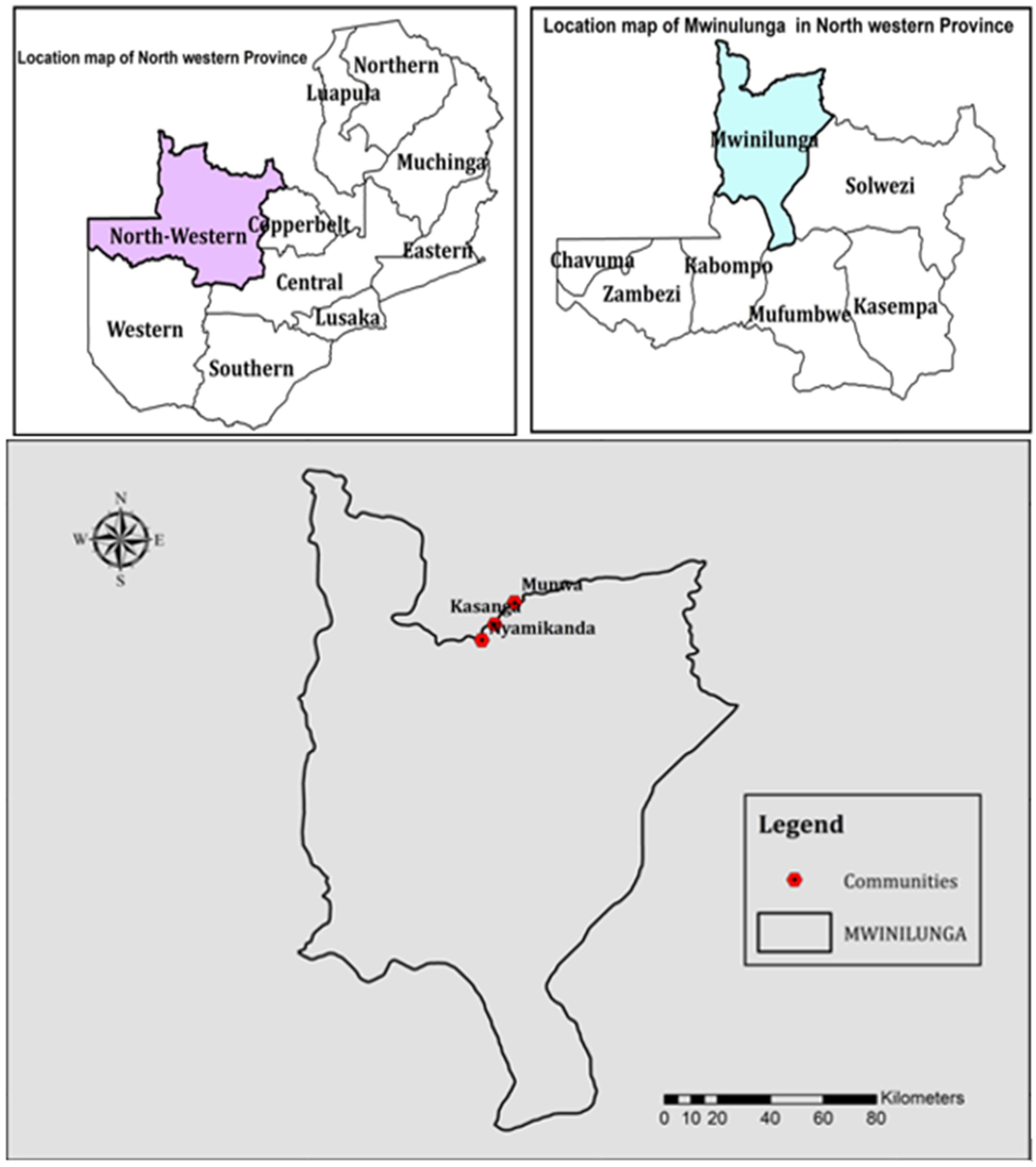

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Study Sample

3.2. Harvesting Chikanda Orchids Species and Perceptions on Wild Orchids Populations

Overall the population of chikanda orchids in the wild is of great concern to us as there is definitely a significant reduction in the quantities of these valuable resources. In the past we never used to walk long distances to harvest chikanda orchids as is the case at the moment (Nyamikanda community interviewee).

In the past we used to harvest as much as 20 kg of chikanda orchids from morning to mid-day. This is not the case anymore as often times we only manage to harvest a maximum of about 3 kg per day. This has now forced most of us to go as far as our neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to harvest chikanda orchids (Munwa community interviewee).

3.3. Association Between Chikanda Orchids Harvesting and Socio-Economic Factors

3.4. Relationship Between Household Food Shortages and Socio-Economic Factors

3.5. Association Between Household Food Shortages and Socio-Economic Factors

“If it was not for the income my household derives from the sale of chikanda, hunger would have eliminated us by now. The income we derived from chikanda sales is very critical in my household so all members of my household participate in chikanda orchids harvesting” (Munwa community interviewee).

3.6. Income from Chikanda Orchids Sales in Comparison to Other Sources

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Angelsen, A.; Jagger, P.; Babigumira, R.; Belcher, B.; Nicholas, J.H.; Bauch, S.; Borner, J.; Smith-Hall, C.; Wunder, S. Environmental income and rural livelihoods: A global comparative analysis. World. Dev. 2014, 64, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavendish, W. Empirical regularities in the poverty-environment relationship of rural households: Evidence from Zimbabwe. World Dev. 2000, 28, 1979–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timko, J.A.; Waeber, P.O.; Kozak., R.A. The socio-economic contribution of non-wood forest products to rural livelihoods in Sub-Sahara Africa: Knowledge gaps and new directions. Internat. Forest. Rev. 2010, 12, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwajombe, A.R.; Liwenga, E.T.; Mwiturubani, D. Contribution of wild edible plants to household livelihood in a semiarid Kondoa District, Tanzania. World Food Pol. 2022, 8, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelsen, A.; Wunder., S. Exploring the Forest-Poverty Ink: Key Concepts, Issues and Research Implications; CIFOR Occassional paper No. 40; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) Indonesia: Bogor, Indonesia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, C.; Shackleton, S. The importance of non-timber forest products in rural livelihood security and as safety nets: A review of evidence from South Africa. S. Afri. J. Sci. 2004, 100, 658–664. [Google Scholar]

- Heubach, K.; Wittig, R.; Nuppenau, E.A.; Hahn, K. The economic importance of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) for livelihood maintenance of rural west African communities: A case study from northern Benin. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 191–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkergaard, R.K.; Hogarth, N.J.; Bong, I.W.; Bosselmann, A.S.; Wunder., S. Measuring forest and wild product contributions to household welfare: Testing a scalable household survey instrument in Indonesia. For. Policy Eco. 2017, 84, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, A.D.; Mekonnen, A.; Hirons, M.; Robinson, E.J.Z.; Gonfa, T.; Gole, T.W.; Demissie, S. Contribution of non-timber forest products to the livelihood of farmers in coffee growing areas: Evidence from Yayu coffee forest biosphere reserve. J. Environ. Plan Manag. 2020, 63, 1633–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, C.M.; Shackleton, S.E.; Buiten, E.; Bird, N. The importance of dry woodlands and forests in rural livelihoods and poverty alleviation in South Africa. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavengahama, S.; McLachlan, M.; de Clercq, W. The role of wild vegetable species in household food security in maize based subsistence cropping systems. Food Sec. 2013, 5, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumkham, S.D.; Chakpram, L.; Salam, S.; Bhattacharya, M.K.; Singh, P.K. Edible ferns and fern- allies of North East India: A study on potential wild vegetables. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2016, 64, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharucha, Z.; Pretty, J. The roles and values of wild foods in agricultural systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2912–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, K.E.; Prasad, S.S. Valuing Indigenous Knowledge for Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Fiji and Vanuatu; Traditional Knowledge Bulletin; United Nations University: Tokyo, Japan, 2013; Traditional Knowledge Bulletin. [Google Scholar]

- Azam, F.M.S.; Biswas, A.; Mannan, A.; Afsana, N.A.; Jahan, R.; Rahmatullah, M. Are famine food plants also ethnomedicinal plants? An ethnomedicinal appraisal of famine food plants of two districts of Bangladesh. Evid.-Bas. Complement Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 741712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erskine, W.; Ximenes, A.; Glazebrook, D.; da Costa, M.; Lopes, M.; Spycherelle, L. The role of wild foods in food security: The example of Timor-Leste. Food Sec. 2015, 7, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, D.F.; Tadesse, W.; Gure, A. Economic contribution to local livelihoods and households’ dependency on dry land forest products in Hammer District, South-eastern Ethiopia. Int. J. For. Res. 2016, 2016, 5474680. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, T.R.B.; Ndangalasi, H.J. An escalating trade in orchid’s tubers in Tanzania’s Southern Highlands: Assessment, dynamics and conservation implications. Oryx 2003, 37, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasulo, V.; Mwabumba, L.; Munthali, C. A review of edible orchids in Malawi. J. Hort. Fores. 2009, 1, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Challe, J.F.X.; Price, L.L. Endangered edible orchids and vulnerable gatherers in the context of HIV/AIDS in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, M.G. Chikanda, an unstainable industry. Pollinia 2009, 7, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Veldman, S.; Gravendeel, B.; Otieno, J.N.; Lammers, Y.; Duijm, E.; Byterbier, B.; Ngugi, G.; Martos, F.; van Andel, T.; de Boer, H. High-throughput sequencing of African Chikanda cake highlights conservation challenges in orchids. Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 26, 2029–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, M.G.; Smith, P.P. Southern African Plant Red Data Lists; SABONET: Pretoria, South Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Veldman, S.; Kim, S.J.; van Andel, T.R.; Font, M.B.; Bone, R.E.; Bytebier, B.; Chuba, D.; Gravendeel, B.; Martos, F.; Mpatwa, G.; et al. Trade in Zambian edible orchids-DNA barcoding reveals the use of unexpected orchid taxa for Chikanda. Genes 2018, 9, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumwenda, F.D.; Sumani, J.; Jere, W.; Nyirenda, K.K.; Mwatseteza, J. Nutritional, phytochemical and functional properties of four edible orchid species from Malawi. Foods 2024, 13, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalika, M.C.S.; Mende, D.H.; Urio, P.; Gimbi, D.M.; Mwanyika, S.J.; Donati, G. Domestication potential and nutrient composition of wild orchids from two southern regions of Tanzania. Time J. Biol Sci. Technol. 2013, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tembo, C.; Phiri, E.E.; Syampungani, S.; Malgas, R.R.; Maciejewski, K.; Dube, T. A point-initime inventory of chikanda orchids within a wild harvesting wetland in Mwinilunga, Zambia: Implications for conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 33, 705–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, M.G.; Kokwe, G.M. Where have all the flowers gone? SABO New. 2001, 6, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Ndaki, P.M.; Erick, F.; Moshy, V. Challenges posed by climate change and non—climate factors on conservation of edible orchids in southern highlands of Tanzania: The case of Makete District. J. Glob Ecol. Environ. 2021, 13, 144–167. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, P.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Bhattacharjee, S. Global research contributions on orchids: A scientometric review of 20 years. J. Appl Biol. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsley, A.; De Boer, H.; Fay, M.F.; Gale, S.; Gardiner, L.M.; Gunasekara, R.S.; Masters, P.S.; Metusala, D.; Roberts, D.; Veldman, S.; et al. A review of the trade in orchids and its implications for conservation. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2018, 186, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaba, F.K.; Quinn, C.H.; Dougill, A.J. Contribution of forest provisioning ecosystem services to rural livelihoods in the Miombo Woodlands of Zambia. Popul. Environ. 2013, 35, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weather Atlas. Climate and Monthly Weather Forecast Mwinilunga, Zambia [WWW Document]. Weather Atlas. 2022. Available online: https://www.weather-atlas.com/en/zambia/mwinilunga-climate (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Zambia Statistics Agency. Census of Population and Housing; Zambia Statistics Agency: Lusaka, Zambia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Uakarn, C.; Chaokromthong, K.; Sintao, N. Sample size estimation using Yamane and Cochran and Krejcie and Morgan and Green formulas and Cohen statistical power analysis by G* power and comparisons. Apheit Internal. J. 2021, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zambia Statistics Agency. Census of Population and Housing. Republic of Zambia; Zambia Statistics Agency: Lusaka, Zambia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tschakert, P.; Coomes, O.T.; Potvin, C. Indigenous livelihoods, slash and burn agriculture and carbon stocks in Eastern Panama. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 60, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumbe, C.B.L.; Bwalya, S.M.; Husselman, M. Contribution Of dry Forests to Rural Livelihoods and the National Economy in Zambia. In Proceedings of the XIII World Forestry Congress, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 18–23 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zulu, D.; Ellis, R.H.; Culham, A. Collection, consumption and sale of lusala (Dioscorea hirtifora)—A wild yam by rural households in Southern Province, Zambia. Econ. Bot. 2016, 73, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M.L. The Chi-squared test of independence. Biochem. Medica. 2013, 23, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, J. Using the Gini coefficient for assessing heterogeneity within classes and schools. SN Soc. Sci. 2023, 3, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Garcia, G.; Lagunez-Rivera, L.; Chavez-Angeles, M.G.; Solano-Gomez, A. The wild orchid trade in a Mexican local market: Diversity and economics. Econ. Bot. 2015, 69, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kideghesho, J.R.; Msuya, T.S. Gender and socio-economic factors influencing domestication of indigenous medicinal plants in the West Usambara Mountains, northern Tanzania. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2010, 6, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiptot, E.; Franzel, S. Gender and agroforestry in Africa: A review of women’s participation. Agrofor. Syst. 2012, 84, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushi, H.; Yanda, P.Z.; Kleyer, M. Socio-economic factors determining extraction of non-timber forest products on the slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Hum. Ecol. 2020, 48, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shively, G.; Pagiola, S. Agricultural intensification, local labor markets and deforestation in the Philippines. Environ. Dev. Econ. 1999, 9, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.; Miller, D.C.; Byenkya, M.A.A.; Agrawal, A. Who are forest dependent people? A taxonomy to aid livelihood and land use decision making in forested regions. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedge, R.; Enters, T. Forest products and household economy: A case study from Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary Southern India. Environ. Conserv. 2000, 27, 250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Belcher, B.; Ruiz-Perez, M.; Achiawan, R. Global patterns and trends in the use and management of commercial NTFPs: Implications for livelihoods and conservation. World Dev. 2005, 33, 1435–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderlin, W.D.; Angelsen, A.; Belcher, B.; Burgers, P.; Nasi, R.; Santoso, L. Livelihood, forests and conservation in developing countries: An overview. World Dev. 2005, 33, 1383–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, M.S.; Wasonga, V.O.; Mbau, J.S.; Suileman, A.; Elhadi, Y.A. Non-timber forest products and their contribution to household income around Falgore game reserve in Kano, Nigeria. Ecol. Process. 2017, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babulo, B.; Muys, B.; Nega, F.; Tollens, E.; Nyssen, J.; Deckers, J. Household livelihoods strategies and forest dependence in the highlands of Tigray Northern Ethiopia. Agric. Syst. 2008, 98, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malleson, R.; Asaha, S.; Egot, S.M.; Kshatriya, M.; Marshall, M.E.; Obeng-Okrah, K.; Sunderland, T. Non-timber forest products income from forest landscapes of Cameroon, Ghana and Nigeria- an incidental or integral contribution to sustaining rural livelihoods. Int. For. Rev. 2014, 16, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamanga, P.; Veldad, P.; Sjaastad, E. Forest incomes and rural livelihoods in Chiradzulu District, Malawi. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamo, G.; Sjaastad, E.; Veldad, P. Economic dependence on forest resources: A case from Dendi District. Ethiop. For. Pol. Econ. 2007, 9, 916–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annestrand, K.; Lenz, S.; Bird, A.; James, A. The Impact of Income Levels on Food Security in Rural Communities. Undergrad. J. Serv. Learn. Community-Based Res. 2016, 5. Available online: https://ujslcbr.org/index.php/ujslcbr/article/view/241 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Dhanda, S.; Bullough, L.A.; Whitehead, D.; Grey, J.; White, K. A Review of the Edible Orchid Trade; Roy Bot Gar: Surrey, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Wealth Categories | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wealthy | Intermediate | Poor | |

| Household size (rooms) | >4 | 1–3 | 1–3 |

| Type of roofing | Iron sheets | Iron sheets | Thatch |

| Size of pineapple field | >10 Ha | 5–10 Ha | <5 Ha |

| Number of barkhives | >100 | 50–100 | <50 |

| Type of sanitation | Pit latrine | Pit latrine | Nil |

| Source of power supply | Solar energy | Solar energy | Nil |

| Characteristic | Category | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Community | Nyaminkanda | 143 (47.2) |

| Munwa | 96 (31.7) | |

| Kasang’a | 66 (21.8) | |

| Household wealth status | Rich | 13 (4.3) |

| Intermediate | 118 (38.9) | |

| Poor | 172 (56.8) | |

| Household head gender | Male | 253 (83.4) |

| Female | 50 (16.5) | |

| Household marital status | Married | 240 (79.2) |

| Single | 32 (10.6) | |

| Divorced | 25 (8.3) | |

| Widowed | 6 (2.0) | |

| Household education | Less than primary | 112 (37.0) |

| Primary | 134 (44.2) | |

| Secondary | 56 (18.5) | |

| Tertiary | 1 (0.3) |

| Involvement in Chikanda Orchids Harvesting | ||

|---|---|---|

| Socio-Economic Factor (N = 303) | χ2 | p-Value |

| Gender | 6 | <0.05 |

| Marital status | 8 | <0.05 |

| Education level | 1 | >0.05 |

| Wealth | 1 | >0.05 |

| Food Shortages | ||

|---|---|---|

| Socio-Economic Factor (N = 303) | χ2 | p-Value |

| Gender | 1 | >0.05 |

| Marital status | 2 | >0.05 |

| Education level | 1 | >0.05 |

| Wealth | 37 | <0.001 |

| Cushioning Food Deficits Using Income from chikanda Sales | ||

|---|---|---|

| Socio-Economic Factor (N = 303) | χ2 | p-Value |

| Gender | 1 | >0.05 |

| Marital status | 3 | >0.05 |

| Education level | 2 | >0.05 |

| Wealth | 6 | <0.05 |

| Variable | Average Income (USD) | Minimum Income (USD) | Maximum Income (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female headed | 34.92 | 1.92 | 292.31 |

| Male headed | 27.23 | 1.92 | 211.54 |

| Wealth status | |||

| Poor | 26.39 | 1.92 | 292.31 |

| Intermediate | 29.46 | 3.84 | 149.23 |

| Wealthy | 42.54 | 5.77 | 211.54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwenye, J.M.; Kabwe, G.; Mulenga, P.; Dalu, M.T.B. The Contribution of Chikanda Orchids to Rural Livelihoods: Insights from Mwinilunga District of Northwestern Zambia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136131

Kwenye JM, Kabwe G, Mulenga P, Dalu MTB. The Contribution of Chikanda Orchids to Rural Livelihoods: Insights from Mwinilunga District of Northwestern Zambia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):6131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136131

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwenye, Jane Musole, Gillian Kabwe, Peter Mulenga, and Mwazvita Tapiwa Beatrice Dalu. 2025. "The Contribution of Chikanda Orchids to Rural Livelihoods: Insights from Mwinilunga District of Northwestern Zambia" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 6131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136131

APA StyleKwenye, J. M., Kabwe, G., Mulenga, P., & Dalu, M. T. B. (2025). The Contribution of Chikanda Orchids to Rural Livelihoods: Insights from Mwinilunga District of Northwestern Zambia. Sustainability, 17(13), 6131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136131