Opportunities for Latvian Companies in West Africa: Cameroon Case

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

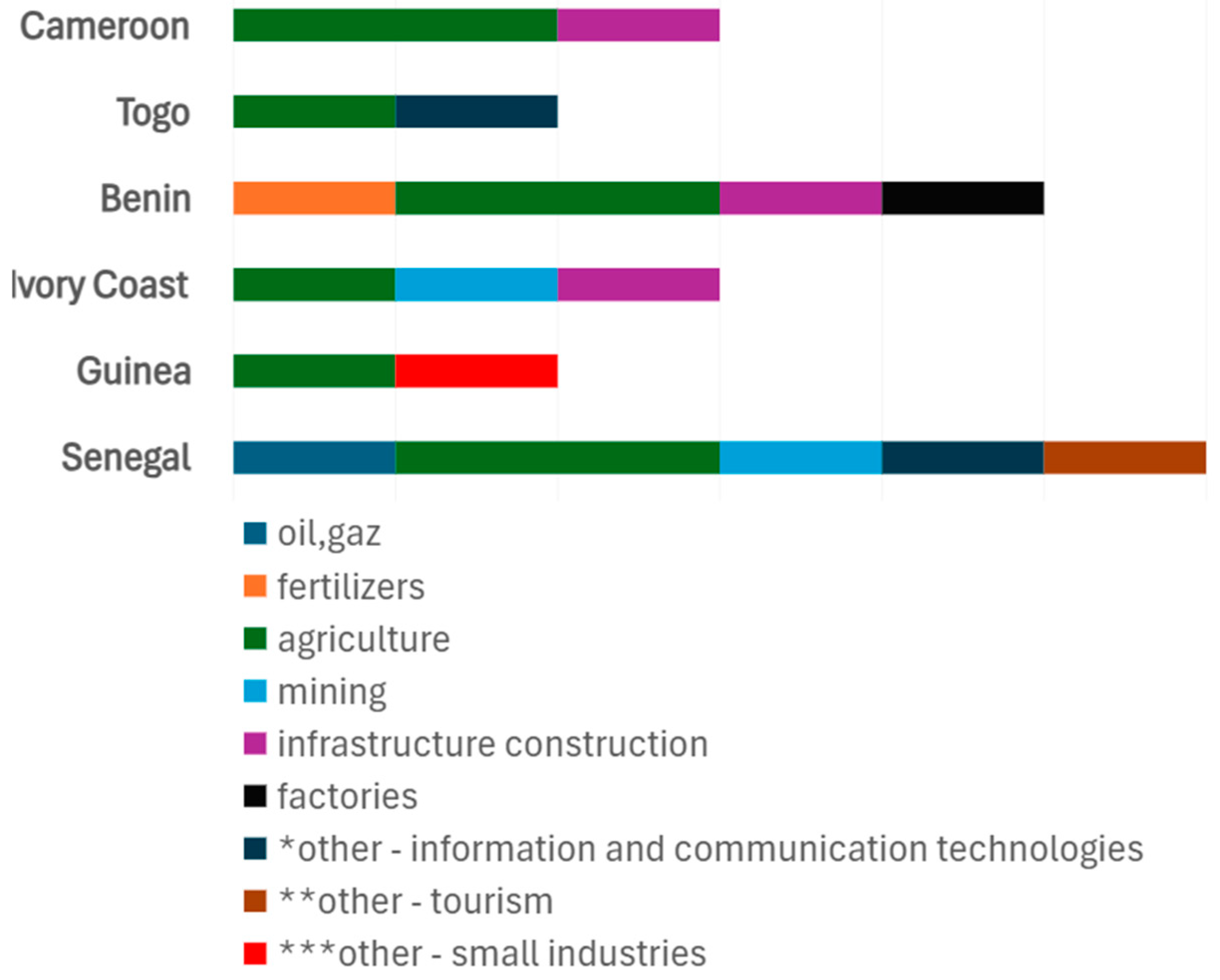

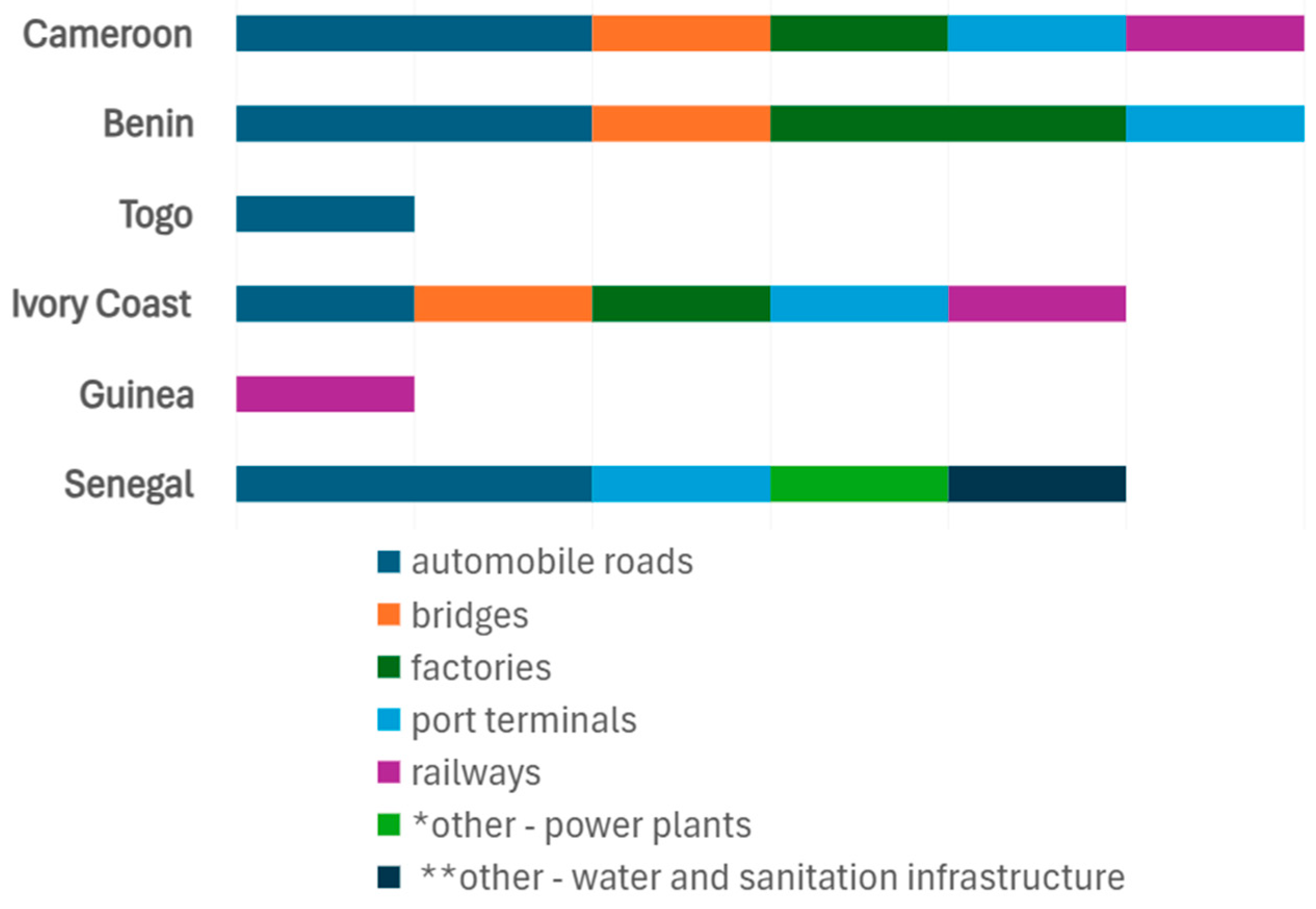

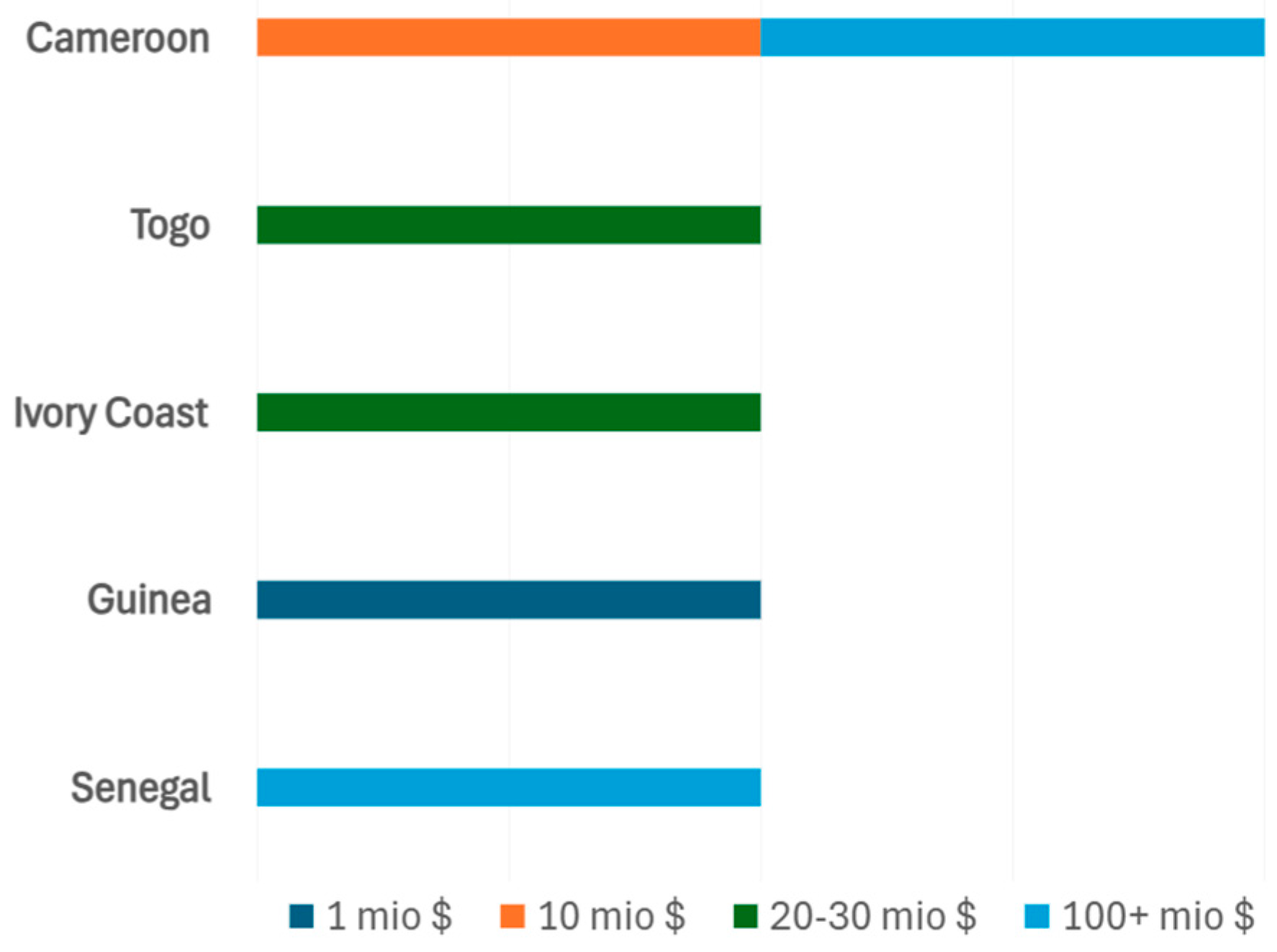

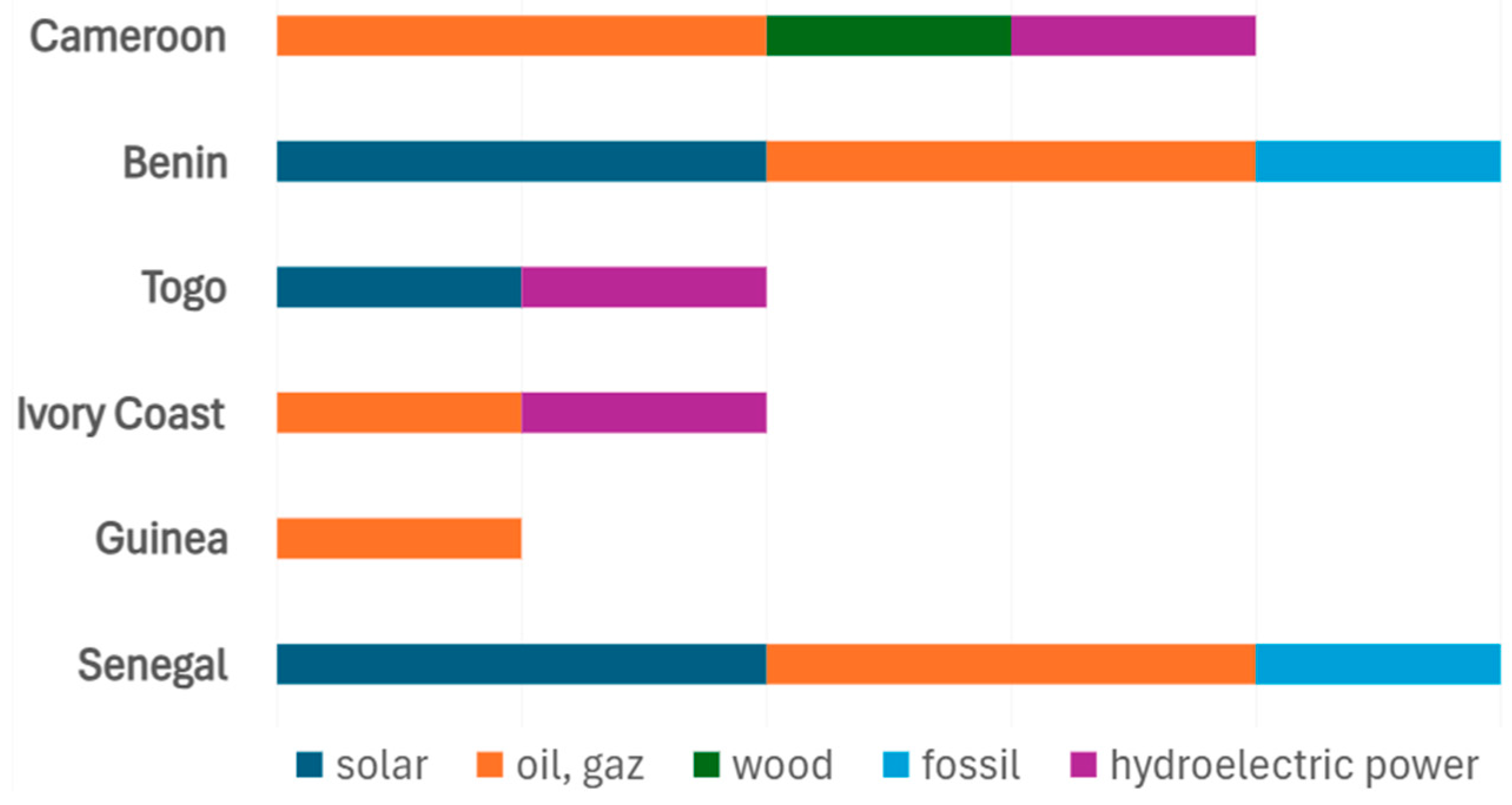

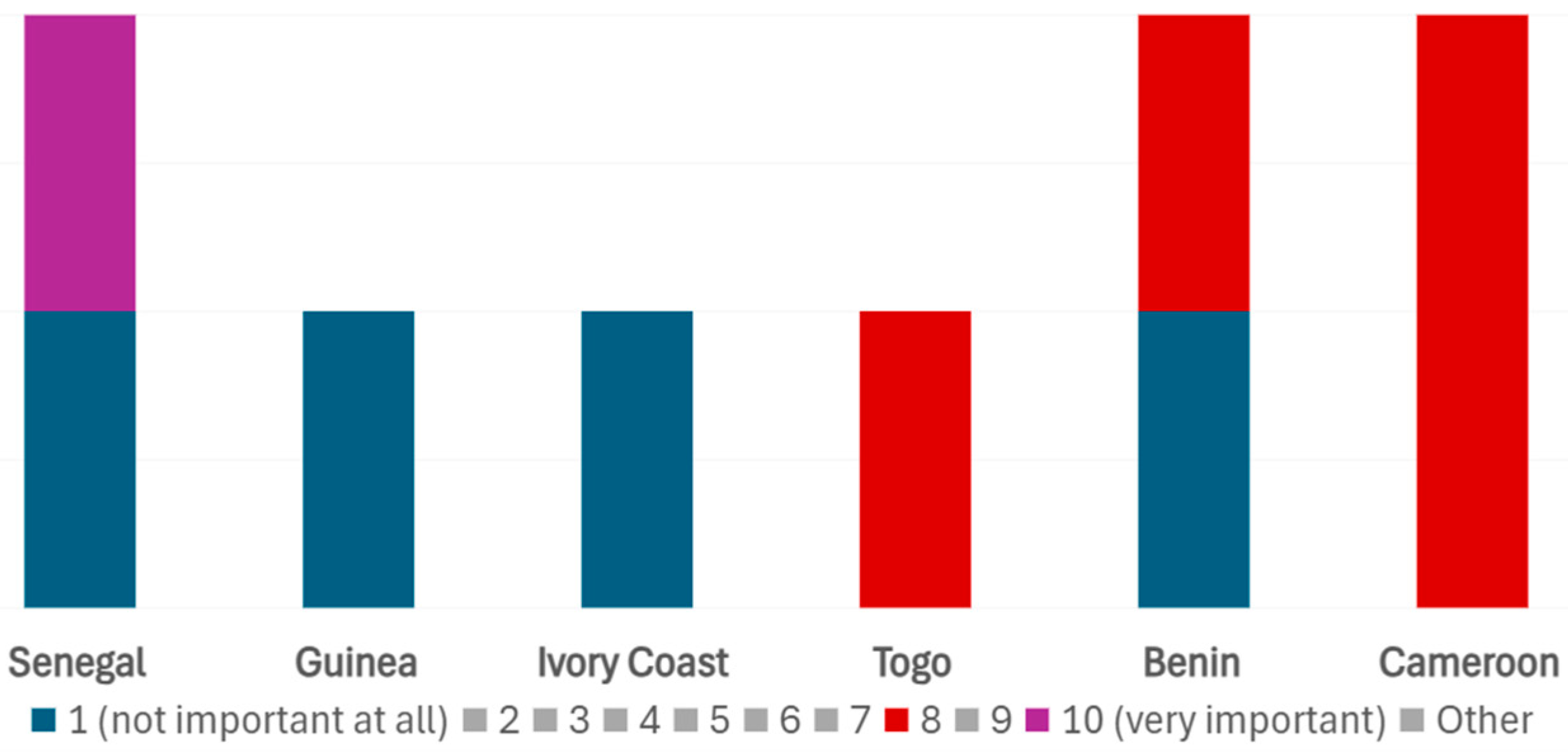

3. Results

4. Case Study—Cameroon: Exploring the Areas and Modalities of Economic and Trade Cooperation with Latvia

4.1. Brief Overview of Cameroon: Strengths, Risks, and Perspectives

4.2. Cameroon: Economic Dashboard

4.3. Cameroon’s Key Economic Indicators

5. Investment and Cooperation Opportunities Between Cameroon and Latvia

- Cereals (largest proportion of the whole volume);

- Articles of iron or steel;

- Machinery and mechanical appliances, e.g., boilers and parts thereof;

- Pharmaceutical products;

- Electrical machinery and equipment and parts thereof [44].

5.1. Digital Transformation

5.2. CO2 Emission Reduction

5.3. Agro-Industry, Food Processing, and Extractive Industries

5.4. Industrial and Economic Zones

5.5. FDI Conditions, Procedures, and Support

- Investment Promotion Agency of Cameroon (API): Facilitates foreign and domestic investment through advisory and administrative support services.

- Public Procurement Regulatory Agency (ARMP): Ensures transparency and fair competition in public contracts.

- Tenders Info and DgMarket: Online platforms providing access to national and international business opportunities.

- Financial institutions:

- ○

- Afriland First Bank: Offers specialized banking services, including project financing and investment credit.

- ○

- International Finance Corporation (IFC): A World Bank Group entity providing financial support to private-sector projects in Cameroon.

6. Recommendations

6.1. Adaptation to Cultural Contexts

- In-depth studies of local business cultural economy

- Strengthening cultural exchanges

- Intercultural communication and training

6.2. Financing and Support

- Mobilizing European and multilateral funds: Exploring opportunities offered by institutions such as Horizon Europe, the European Development Fund (EDF), and other multilateral partners for high-impact projects.

- Creating a Latvia–Cameroon bilateral fund: Establishing a joint financing mechanism targeting strategic sectors such as sustainable agriculture, renewable energy, and cultural and creative industries.

- Facilitating public–private partnerships (PPPs): Encouraging private investors from both countries to collaborate in structuring projects through tax incentives and institutional support.

6.3. Communication and Visibility

- Create a permanent platform to promote economic exchanges, support businesses, and facilitate institutional communication between both countries.

- Develop academic mobility programs, including scholarships and university exchanges for students and faculty.

- Support joint cultural festivals to showcase each country’s heritage and boost tourism.

- Encourage partnerships between educational and technical institutions to foster skill transfer.

6.4. Negotiating a Cooperation Framework Agreement and Establishing Diplomatic Relations

- Negotiate a comprehensive agreement to define the foundations of diplomatic, economic, trade, and cultural relations. The agreement should identify priority areas and include mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation.

- Establish a Latvian embassy or consulate in Cameroon, and vice versa, to provide an official diplomatic presence and consular services.

- Appoint economic and cultural attachés in both countries to promote bilateral relations.

- Strengthen dialog through high-level meetings among sectoral, political, diplomatic, and economic leaders to assess progress and explore new opportunities.

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ye, X.; Lai, M.; Xiao, H.; Zhou, D. Waves or ripples: African countries risk shocks and the survival of Chinese exports to Africa. China Econ. Rev. 2024, 88, 102287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wu, B.; Guo, Q. The efficiency of China’s export trade with Africa and its influence mechanism. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2024, 36, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habyarimana, J.B. Sino–Africa Trade Flows: Effect of Interaction Between Africa’s Population Density and Governance. Chin. Econ. 2024, 57, 472–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurç, Ç. No Strings Attached: Understanding Turkey’s Arms Exports to Africa. J. Balk. Near East. Stud. 2024, 26, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngundu, M.; Matemane, R. South-South vs North-South value chain integration and value addition in Sub-Saharan Africa. Res. Glob. 2023, 7, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-J.; Huang, J.; Wen, C.; Zhang, S. Will China-Africa trade increase Africa’s carbon emissions? PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knößlsdorfer, I.; Qaim, M. Cheap chicken in Africa: Would import restrictions be pro-poor? Food Secur. 2023, 15, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, M.; Mirnezami, S.R.; Khargh, M.T. The impact of organizational capabilities on the international performance of knowledge-based firms. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasahara, H.; Tang, H. Excessive entry and exit in export markets. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2019, 53, 101031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, C.; Pierola, M.D. Export surges. J. Dev. Econ. 2012, 97, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehe, D.M.; Becerra, M. Market entry into new export markets: When are firms more likely to imitate their competitors’ market presence? Int. Bus. Rev. 2022, 31, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, B. Institutional influences on board composition of international joint venture firms listing on emerging stock exchanges: Evidence from Africa. J. World Bus. 2015, 50, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabling, R.; Sanderson, L. Exporting and firm performance: Market entry, investment and expansion. J. Int. Econ. 2013, 89, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Pangarkar, N.; Wu, Z. The moderating effect of technology and marketing know-how in the regional-global diversification link: Evidence from emerging market multinationals. Int. Bus. Rev. 2016, 25, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-W.; Díaz, J.P. The new goods margin in new markets. J. Comp. Econ. 2018, 46, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramov, V.; Breban, D.; Mukhtarov, E. Economic effects estimation for the Eurasian Economic Union: Application of regional linear regression. Communist Post-Communist Stud. 2019, 52, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, P.D. Paths to foreign markets: Does distance to market affect firm internationalisation? Int. Bus. Rev. 2007, 16, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarlund, C.; Andersson, A. What’s in it for Africa? European Union fishing access agreements and fishery exports from developing countries. World Dev. 2019, 113, 172–185. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Latvia (latv.-Latvijas Banka). The Foreign Trade Scene—Recession or Normalization? (latv.—Ārējās tirdzniecības aina—recesija vai normalizācija?). 2013. Available online: https://www.makroekonomika.lv/arejas-tirdzniecibas-aina-recesija-vai-normalizacija (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Orgalim, Europe’s Technology Industries. Economics & Statistics Report—Spring 2025. 2025. Available online: https://orgalim.eu/wp-content/uploads/Orgalim-Economics-and-Statistics-Report-Spring-2025.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- European Commission. The Future of European Competitiveness: Report by Mario Draghi (9 and 17 September 2024). 2024. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-looking-ahead_en (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Brkić, A.; Spasojević-Brkić, V.; Veljkovic, Z. How to Overcome Exporting Barriers and Prevent SMEs Failure: Serbian and BIH Perspective. University of Belgrade, Technical Faculty in Bor, Engineering Management Department (EMD). 2019, pp. 97–130. Available online: https://machinery.mas.bg.ac.rs/handle/123456789/4060 (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Johanson, J.; Wiedersheim-Paul, F. The internationalization of the firm? Four Swedish cases. J. Manag. Stud. 1975, 2, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Vahlne, J. The internationalization process of the firm—A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1977, 8, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, A. Research into the internationalisation process: Advice to an alien. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 1999, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouthers, K.D.; Nakos, G.; Dimitratos, P. SME Entrepreneurial Orientation, International Performance, and the Moderating Role of Strategic Alliances. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 39, 1161–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.W.; Beamish, P.W. The internationalization and performance of SMEs. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skudiene, V.; Auruskeviciene, V.; Sukeviciute, L. Internationalization model revisited: E-marketing approach. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- African Development Bank. African Economic Outlook 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/en/knowledge/publications/african-economic-outlook (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Dohse, D.; Fehrenbacher, S.; von Carlowitz, P. Developing Potential and Sharing Knowledge: How German Companies Can Gain a Foothold in Africa (ger.-Potenziale entwickeln und Wissen teilen: Deutsche Unternehmen in Afrika). Wirtschaftsdienst 2022, 102, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. The World Bank in Africa. 2024. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/overview (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- The 2024 Africa Sustainable Development Report. Executive Summary. Jointly Produced by The African Union, African Development Bank, United Nations Development Programme and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. 2024. Available online: https://www.undp.org/africa/publications/2024-africa-sustainable-development-report (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Williams, J.E.M.; Chaston, I. Links between the Linguistic Ability and International Experience of Export Managers and their Export Marketing Intelligence Behaviour. Int. Small Bus. J. 2004, 22, 463–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayomi, O.S.I.; Okokpujie, I.P.; Kilanko, O. Challenges of Research in Contemporary Africa World. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Engineering for Sustainable World (ICESW 2018), Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria, 9–13 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, L.A. Comment: On Respondent-driven Sampling and Snowball Sampling in Hard-to-reach Populations and Snowball Sampling Not in Hard-to-reach Populations. Sociol. Methodol. 2011, 41, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinheksel, A.J.; Rockich-Winston, N.; Tawfik, H.; Wyatt, T.R. Demystifying Content Analysis. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 84, 7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economy, Planning and Regional Development of the Republic of Cameroon (fr., -Ministère de l’Economie du Plan et de l’Aménagement du Territoire, République du Cameroun (MINEPAT)). Republic of Cameroon. National Strategy for Development 2020–2030 (fr., -République du Cameroun. Stratégie Nationale De Développement 2020–2030). 2020. Available online: www.minmidt.cm/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/SND30_Strategie-Nationale-de-Deveppement-2020-2030.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Nelle, P. Cameroon: The Cultural Code of Business (fr., -Cameroun: Le Code Culturel Des Affaires). Forbes. 2024. Available online: https://forbesafrique.com/cameroun-le-code-culturel-des-affaires/ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Bank of France (fr., -Banque de France). Annual Report on Africa-France Monetary Cooperation. Cameroon Monograph, 2024 (fr., -Rapport Annuel des Coopérations Monétaires Afrique-France. Monographie Cameroun, 2024). 2024. Available online: https://www.banque-france.fr/system/files/2024-11/CEMAC_Cameroun_2023.pdf# (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Coface: Cameroon. Country File, Economic Risk Analysis. 2024. Available online: https://www.coface.com/news-economy-and-insights/business-risk-dashboard/country-risk-files/cameroon (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- BNP Paribas Bank. Cameroon: Investments (fr., -Cameroun: Les Investissements). 2024. Available online: https://www.tradesolutions.bnpparibas.com/fr/implanter/cameroun/investissement (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Coface: Cameroon. Analysis of the Business Environment and Assessment of Country Risks in Cameroon (Fr., Cameroun. Analyse de L’environnement des Affaires et Appréciation des Risques Pays du Cameroun). 2024. Available online: https://www.coface.com/fr/actualites-economie-conseils-d-experts/tableau-de-bord-des-risques-economiques/fiches-risques-pays/cameroun (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Cameroon Country Report: Mobilizing Private Sector Financing for Climate and Green Growth (fr., -Rapport Pays Cameroun: Mobiliser les Financements du Secteur Privé en Faveur du Climat et de la Croissance Verte). 2023. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/cfr_cameroun_2023_0.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Official Statistics Portal of Latvia Data. Exports and Imports by Countries (CN at 2-Digit Level) 2005–2024. Database Data ATD020. 2025. Available online: https://stat.gov.lv/en/statistics-themes/trade-and-services/foreign-trade-goods/tables/atd020-exports-and-imports (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- European Commission. Economic Partnership Agreements (fr., -Accords de Partenariat Économique (APE). 2016. Available online: https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/fr/content/ape-afrique-centrale (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Motongane, C.A. Digital In Cameroon (fr.,-Le Numérique Au Cameroun). INTERMINES Mining Support Federation (fr., -Federation de Support Minière INTERMINES). 2024. Available online: https://inter-mines.org/fr/article/le-numerique-au-cameroun/21/03/2024/2780 (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Ministry of Smart Administration and Region Development, Republic of Latvia (latv., -Viedās Administrācijas un Reģionālās Attīstības Ministrija, Latvijas Republika). Latvia Continues to Lead in Public Service Digitization and e-Identity Usage within the EU (latv., -Latvija Turpina būt Starp ES Līderiem Publisko Pakalpojumu Digitalizācijā un Elektroniskās Identitātes Izmantošanā). 2024. Available online: https://www.varam.gov.lv/lv/jaunums/latvija-turpina-starp-es-lideriem-publisko-pakalpojumu-digitalizacija-un-elektroniskas-identitates-izmantosana (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Interoperable Europe Portal. European Commission Report. Digital Government Factsheets—Latvia. 2019. Available online: https://interoperable-europe.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/inline-files/Digital_Government_Factsheets_Latvia_2019.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Andzongo, S. In Cameroon, Cybercrime Causes the Economy to Lose 12.2 billion FCFA in 2021 (Antic) (fr., -Au Cameroun, la Cybercriminalité Fait Perdre 12,2 Milliards de FCFA à L’économie en 2021 (Antic)). Invest in Cameroon (fr., -Investir au Cameroun) 2022. Available online: https://www.investiraucameroun.com/gestion-publique/0703-17600-au-cameroun-la-cybercriminalite-fait-perdre-12-2-milliards-de-fcfa-a-l-economie-en-2021-antic (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Bonny, A. Cybercrime: More than12 Billion CFA Francs Lost in 2021, Major Risks in Cameroon. (Fr., Cybercriminalité: Plus de 12 Milliards de FCFA Perdus en 2021, Risques Majeurs au Cameroun). CIO-MAG. 2022. Available online: https://cio-mag.com/cybercriminalite-plus-de-12-milliards-de-fcfa-perdus-en-2021-risques-majeurs-au-cameroun/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Njoya, S. Cameroon Develops a National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence (fr., -Le Cameroun Elabore une Stratégie Nationale D’intelligence Artificielle). We are Tech.Africa. 2025. Available online: https://www.wearetech.africa/fr/fils/actualites/tech/le-cameroun-elabore-une-strategie-nationale-d-intelligence-artificielle (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Latvian National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) 2021–2030. 2024. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/latvia-final-updated-necp-2021-2030-submitted-2024_en (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- The New European “Bauhaus” Statement (latv., -Jaunā Eiropas “Bauhaus” Paziņojums). European Commission. 2021. Available online: https://latvia.representation.ec.europa.eu/jaunumi/jauna-eiropas-bauhaus-pazinojums-2021-09-15_lv#:~:text=Jaun%C4%81%20Eiropas%20%E2%80%9CBauhaus%E2%80%9D%20iniciat%C4%ABvas%20m%C4%93r%C4%B7is%20ir%20rad%C4%ABt%20jaunu,vienlaikus%20respekt%C4%93jot%20Eirop%C4%81%20un%20%C4%81rpus%20t%C4%81s%20eso%C5%A1o%20daudzveid%C4%ABbu (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Latvian Union of Civil Engineers (latv., -Latvijas Būvinženieru Savienība), The Creation of the European Bauhaus Initiative has Begun (latv., -Sākta Eiropas “Bauhaus” Iniciatīvas Izveide). 2021. Available online: https://buvinzenierusavieniba.lv/sakta-eiropas-bauhaus-iniciativas-izveide (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Official Statistics Portal of Latvia Data. Air Emission Accounts (NACE Rev. 2) 2000–2022. Database Data GPE010. 2024. Available online: https://data.stat.gov.lv/pxweb/en/OSP_PUB/START__ENV__GP__GPE/GPE010/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Cameroon Imported 520 Billion FCFA Worth of Equipment in 2022, Demonstrating the Dynamism of Its Industries (fr., -Le Cameroun a Importé Pour 520 Milliards de FCFA D’équipements en 2022, Témoignant D’un Dynamisme des Industries). Invest in Cameroon (fr., -Investir au Cameroun). 2024. Available online: https://www.investiraucameroun.com/economie/2302-20366-le-cameroun-a-importe-pour-520-milliards-de-fcfa-d-equipements-en-2022-temoignant-d-un-dynamisme-des-industries#:~:text=Au%20cours%20de%20la%20p%C3%A9riode%2C%20r%C3%A9v%C3%A8le%20l%E2%80%99Institut%20national,de%20FCFA%20pour%20les%20produits%20du%20r%C3%A8gne%20v%C3%A9g%C3%A9tal%29 (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Japan World Bridge: Cameroon’s Natural and Economic Resources (fr., -Les Ressources Naturelles et Économiques du Cameroun). 2025. Available online: https://japanworldbridge.org/portfolio-item/ressources-naturelles-du-cameroun/ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- National Institute of Statistics of Cameroon: Cameroon’s Foreign Trade in the First Half of 2021. (Fr. Institut National de la Statistique du Cameroun: Commerce Extérieur du Cameroun au Premier Semestre 2021). 2021. Available online: https://ins-cameroun.cm/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Note-Commerce-exterieur-1er-semestre-2021-final.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Republic of Cameroon: Report on the Economic, Social, and Financial Situation and Prospects of Cameroon. Ministry of Finance—Yaoundé. (Fr., Rapport sur la Situation et les Perspectives Economiques, Sociales, et Financières du Cameroun. Ministère des Finances—Yaoundé). 2022. Available online: https://minfi.gov.cm/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/REF_2022_FR.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Invest in Cameroon; Edition of Friday, February 2. (Fr., Investir au Cameroun; Edition du Vendredi 02 Février). 2024. Available online: https://www.investiraucameroun.com/energie/0202-20271-le-cameroun-mise-sur-l-amelioration-de-l-offre-energetique-pour-porter-la-croissance-hors-petrole-a-7-6-d-ici-2026 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Presidency of the Republic of Cameroon: Decree of the President of the Republic of August 3, 2016, Setting the Rules of Origin and Methods of Administrative Cooperation Applicable to Goods from the European Union within the Framework of the Step towards the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA). (fr., -Décret du Président de la République du 03 Août 2016 Fixant les Règles D’origine et les Méthodes de Coopération Administrative Applicables Aux Marchandises de L’union Europeenne dans le Cadre de L’accord D’étape vers L’ACCORD de Partenariat Economique (APE). 2016. Available online: https://prc.cm/fr/multimedia/documents/4756-decret-n-2016-367-du-03-08-2016-ape (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Mines, and Crafts of Cameroon (CCIMA) (fr., -Chambre de Commerce, de L’industrie, des Mines et de L’artisanat du Cameroun (CCIMA). Available online: https://ccima.cm/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Tabapssi, T. Vernacular education and productive accumulation of Bamiléké migrants from Cameroon (fr., -Éducation vernaculaire et accumulation productive des migrants bamiléké du Cameroun). Présence Afr. 2005, 172, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Government Corrective Measures |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Economic Indicators | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 (f) | 2025 (f) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP growth | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 4.4 |

| Inflation, average consumer prices | 6.3 | 7.4 | 6.3 | 4.3 |

| Budget balance/GDP | −1.1 | −0.9 | −0.5 | −0.2 |

| Current account balance/GDP | −3.4 | −2.7 | −1.9 | −1.6 |

| Public debt/GDP | 45.3 | 41.8 | 41 | 35.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lozova, L.; Tabapssi, T.; Sloka, B. Opportunities for Latvian Companies in West Africa: Cameroon Case. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6060. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136060

Lozova L, Tabapssi T, Sloka B. Opportunities for Latvian Companies in West Africa: Cameroon Case. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):6060. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136060

Chicago/Turabian StyleLozova, Ludmila, Timothée Tabapssi, and Biruta Sloka. 2025. "Opportunities for Latvian Companies in West Africa: Cameroon Case" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 6060. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136060

APA StyleLozova, L., Tabapssi, T., & Sloka, B. (2025). Opportunities for Latvian Companies in West Africa: Cameroon Case. Sustainability, 17(13), 6060. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136060