1. Introduction

Lakes are sites of water accumulation and runoff where a variety of animal species and plant varieties inhabit, whose survival directly depends on the conservation of this element. Likewise, historically, lakes and bodies of water have represented an important source not only for access to water resources but also significant spaces where rituals and religious practices take place [

1], from which the transmission of traditional knowledge is generated and social activities within territories are strengthened, maintaining relationships between communities that establish themselves around these bodies of water.

A lake is “a tangible and usable good for society, but also a resource, insofar as it is usable [sic]” [

2] (p. 32), or it can be considered that lakes have a utilitarian value. However, they are also patrimonial assets, especially cultural ones, as lakes host a series of activities strongly linked to human and social components. These are manifested through economic, political, sociocultural, and religious practices and processes, which are subject to both tangible and intangible expressions (such as rituals, hymns, songs, legends, artistic designs, and images) that reflect the dynamics of the lakes but also those on land [

3].

It is precisely this inseparable nature of lacustrine bodies with human interaction that also makes these lakes manifestations of landscapes, which are “sociocultural constructions [whose] objects form a concrete reality as a geographical territory; these have no particular meaning without the insertion of human actors who appropriate and interpret them” [

4] (p. 105). Likewise, according to [

5], the lacustrine space “is a reality: cultural, historical, natural, landscape-related, with activities and laws over a singular territory” [

5] (p. 210). Considering these two premises, we can establish that lacustrine landscapes are spaces where the mentioned realities of riparian communities are articulated and inseparably connected with lacustrine bodies.

Considering the above, it is worth mentioning that the transformation processes affecting lacustrine landscapes impact not only the loss of the water resource itself but also generate changes in the economic and social appropriation of these lacustrine spaces [

6], sometimes with potentially devastating effects. The loss of the water resource, and consequently of the lacustrine landscape, can be caused by a series of factors which are usually of human origin, such as the indiscriminate and unsustainable use of the resource or a lack of coordinated management to address the needs of agriculture, livestock, residential areas, or even tourism. An example of the impacts of tourism on lake landscapes closely tied to cultural heritage can be found in Finland, where Lake Inari is located. There, a rocky islet called Ukonkiv (one of the sacred sites of the Sámi culture) has been recently compromised due to tourism that can be considered irresponsible, stemming from visitors’ lack of knowledge about traditional Sámi wisdom and customs. In response, Finnish authorities decided to take action and restrict access to the islet [

7], as the continuation of harmful practices could jeopardize the sustainability of both the heritage and the lake landscape.

Another case that also reflects the environmental impacts on lake landscapes due to anthropogenic intervention is that of the Gosainkunda River in India, analyzed by the authors of [

8], who stated that intense pollution affects the lake’s ecosystem. This has been happening despite the fact that the lake is associated with Buddhist and Hindu religious practices, whose festivities draw large numbers of pilgrims. These gatherings at devotional sites, where visitors come to pay their respects, can be seen as a way of recognizing culture and cultural heritage with a view toward its preservation. However, they also generate adverse effects, as during their journey, visitors produce waste that ends up polluting the river.

In some urbanized territories near lacustrine landscapes, the advance of urban expansion due to (dis)organized territorial planning and the establishment of enterprises that demand riparian resources can lead to contamination and loss of these resources. This issue can be observed in regions such as the Xiang River in China, which faces pollution problems due to overpopulation, urbanization, and industrial growth [

9]. Additionally, possible adverse effects derived from climate change [

10] (p. 2) may contribute to the desiccation of lakes.

The loss of a water resource also results in a decline in local diversity and biodiversity, as lacustrine landscapes facing such problems frequently experience “the death of fish, which are part of the lagoon’s trophic chain” [

11] (p. 131).

This situation may lead to the potential loss of cultural heritage closely linked to lacustrine landscapes, as is the case with Laguna de Cajititlán, located in the municipality of Tlajomulco de Zúñiga in the state of Jalisco in México. This lacustrine landscape and territorial legacy have undergone significant social, environmental, cultural, and economic transformations, placing it in a current state of fragility due to the incessant processes of urbanization and metropolitan expansion in its territory. The desiccation of the endorheic basin intensified notably in the years 1947 and 2001 [

12] (p. 103), as did pollution from wastewater discharges into its course and the proliferation of leachates, which have led to fish and migratory bird mortality, generating impacts on the health, employment, and economy of the riparian inhabitants, as “a great diversity of biological indicators of pollution was found” [

11] (p. 137) which harmed the state of Laguna de Cajititlán.

This is relevant since the lacustrine landscape of Laguna de Cajititlán represents not only a body of water for the community but also cultural heritage, as one of the most important traditional and religious practices in the region has been woven around this lagoon: the Procesión Los Santos Reyes (Procession of the Wise Men). This consists of a procession of a series of wooden figures which allude to the patron saints of Cajititlán through the town’s streets, accompanied by the entire community. The pilgrimage of these figures concludes at Laguna de Cajititlán, where they board boats that navigate its waters. The primary purpose of this practice is to petition for a good rainy season for the region, as well as the conservation and sustainability of the lagoon itself, in such a way that the articulation between religious tradition, as the cultural heritage of the community, and the lacustrine landscape is inseparable.

In response to the aforementioned situation, the rescue, conservation, and reproduction of the Procesión Los Santos Reyes religious practice has emerged, which in light of the issues affecting the lacustrine landscape raises the following question: How does the Procesión Los Santos Reyes tradition in the town of Cajititlán influence the conservation of the lacustrine landscape embodied in Laguna de Cajititlán in Tlajomulco, Jalisco, México? The response to this question leads to the hypothetical assumption that the historical heritage elements of the Indigenous people of Cajititlán contribute to the empowerment of their community, which prioritizes the defense of water and safeguarding of the lacustrine landscape through cultural expressions to prevent environmental deterioration. Therefore, the objective of this article is to analyze how this tradition influences the conservation of the historical lacustrine landscape of Laguna de Cajititlán. This is approached through a qualitative methodological design that includes bibliographic research, participant observation, and the application of interviews. These interviews recover the voices and life stories of the inhabitants of the Laguna de Cajititlán landscape and analyze the relationship between cultural heritage and conservation of the lacustrine landscape from the analytical dimensions of the (1) urban-rural issues of the lagoon; (2) history and pre-Columbian lacustrine landscape; and (3) cultural heritage, including (a) legends and historical beliefs as well as (b) tradition and collective identity.

In this context, the Procesión Los Santos Reyes can be considered a path toward safeguarding not only the cultural heritage of the community but also the conservation of the lacustrine landscape. This is achieved through the construction of tradition and a collective identity, the perception of Laguna de Cajititlán as a living entity, the promotion of touristic activities, and the multifunctionality of the landscape, as well as the proposal of public conservation policies that could be developed for the protection of water resources.

This also relates to the Faro Convention, which “outlines a framework to define the role of civil society in decision-making and managing processes related to cultural heritage. Citizens’ participation has become an ethical necessity as well as a political opportunity: it revitalizes communities, strengthens democracy, and fosters coexistence for a better quality of life” [

13] (p. 5) In this sense, the previous European idea highlights relevant cultural aspects without which society would not make progress in safeguarding or rescuing tangible or intangible assets in other areas. This is linked to the phenomenon under study, since the Procession of the Wise Men, which influences the inhabitants of Cajititlán, coexists with a disconnection and apathy among new generations toward this tradition. Therefore, despite it being a heritage site, there is a lack of interest, given the event’s fragility.

This study is relevant as it presents an opportunity to strengthen the historical and cultural knowledge and understanding of Laguna de Cajititlán, which is ancestrally historical, as well as the phenomena and events that impact it. “The lack of hard data and testing of hypotheses of certain features and events in the recent history of the lakes are among other causes for the acceptance and perpetuation of erroneous beliefs about the natural and cultural history of the lakes” [

6] (p. 16). Thus, this study adopts a cultural heritage perspective with a view toward the conservation and sustainability of the lacustrine landscape, which is both innovative and useful to discuss not only for Laguna de Cajititlán but also for the conservation and sustainability of lacustrine landscapes anywhere that cultural heritage plays a relevant role, as can be the case of the Mandeba Medahinealem Monastery, which was built in the early 14th century on a small island in the center of Lake Tana in Ethiopia and is recognized as a center of spirituality and architectural heritage closely linked to the surrounding lake landscape (as it is believed that the monastery’s founder miraculously arrived on the island floating on a stone slab along the river). Today, faithful believers reach the monastery by crossing the lake in barges or even by swimming to attend the annual religious celebrations [

14].

This highlights the connection between forms of cultural heritage representation, articulated through religious practices, and the lake landscape, along with the symbolism it carries, as seen in the beliefs surrounding the Procesión Los Santos Reyes in Laguna de Cajititlán.

3. Methodology

This research employed a qualitative methodology, which refers to “research that produces descriptive data: the very words of people, whether spoken or written” [

30] (p. 7). This approach makes it possible to identify “the importance of cultural landscapes [and] allows us to understand how the relationship between humans, the land, nature, and the territory has evolved. [To] comprehend the successive overlapping of cultures and forms of interaction with the environment over time” [

31] (p. 33). Additionally, the following methodological instruments were used: bibliographic research (use of secondary sources), participant observation, and in situ landscape observation. This participant observation, as well as the interviews, were conducted in the last quarter of 2023 and in the month of April 2024, involving close engagement with the local inhabitants of Cajititlán.

The objective was to study, from their perspective and memory, the historical and cultural development of the lagoon as a fundamental element in their perception, contrasted with a cabinet-based bibliography. Also, information was gathered from primary sources through the life history method and the application of semi-structured interviews with the inhabitants of the landscape site. More detailed information about the interviews is provided in the following section.

It is relevant to mention that the main difference between participant observation and in situ observation is that in the former, the researcher engages and participates with the social group being studied, highlighting the daily lives of the inhabitants and how they experience the landscape and their traditions as heritage. On the other hand, in situ observation corresponds to studying the landscape from the empirical perspective of the researcher through observing the daily lives of the inhabitants coexisting with their heritage.

Methodological Design and Research Stages

This research was conducted in four stages. The first stage focused on identifying the territory of the landscape to be studied. In the second stage, the elements of the landscape were characterized by gathering cabinet-based information and conducting a literature review. The third stage consisted of fieldwork, while the fourth stage involved synthesizing and analyzing the collected data, as well as drafting conclusions. These stages are detailed below.

The first stage, which was carried out in January 2023, focused on delineating the study area by creating a polygon on Laguna de Cajititlán as the designated location within the Municipality of Tlajomulco de Zúñiga. The polygon was delineated by using satellite images from Google (2024) and the open-source software QGIS version maidenhead 3.36.

Cajititlán is an Indigenous town (

Figure 1) located in the municipality of Tlajomulco de Zúñiga in the state of Jalisco, México, where the lagoon bearing its name is situated. Its classification as an Indigenous town is based on the fact that “these [communities] are characterized by being historical collectives [or communities] with a territorial base and distinct cultural identities” [

32] (p. 58). Additionally, “the legacy of Indigenous Peoples, along with the enriching presence of their descendants, contemporary Indigenous groups, [is] recognized [together with] their rights in all contexts of national life” [

33] (p. 364). Therefore, an Indigenous town stands out based on its originality, its culture, and its inhabitants, who across generations strengthen its historical heritage.

The Laguna de Cajititlán borders five indigenous riverside towns: Cajititlán, Cuexcomatitlán, San Miguel Cuyutlán, San Lucas Evangelista, and San Juan Evangelista (

Figure 2).

The Laguna de Cajititlán was selected as the object of study mainly for its lacustrine landscape with rural ecosystem characteristics, for the traditions that have been carried out for more than 500 years in the town, and for the lagoon economic activities that take place in the region. Likewise, it was selected because although the lacustrine area is surrounded by five towns that share the same landscape, the duality of the rural and urban landscape of Cajititlán makes it a site that deserves safeguarding of its landscape so that it is not forgotten and therefore studied.

The second stage, which lasted three months from February to April 2023, consisted of characterization of the elements of the landscape through the review of texts related to heritage, landscape, and lacustrine culture. The literary correlation provided an understanding of the worldview of the inhabitants and their use of the lacustrine landscape as a source of income for primary activities in the rural sector.

The third stage, carried out in the last quarter of 2023 and first quarter of 2024, as mentioned before, consisted of fieldwork (in situ participant observation, life history method, and interviews with inhabitants of the landscape site and key actors responsible for safeguarding the traditions of Laguna de Cajititlán). For this phase, the methodology proposed in [

36] was used, with the authors suggesting that “field notes, descriptions, explanations, etc., should be reduced through appropriate coding until reaching meaningful and manageable units. It also involves structuring and representing this data to conclude with more comprehensive findings” (p. 73).

Additionally, it is worth mentioning that the landscape observation method proposed in [

37] provided criteria for characterizing landscapes based on the participation of those involved in this process, as it is the local actors who determine the actions for their conservation. In engaging with the local inhabitants of Cajititlán and seeking to recover their life histories, 20 semi-structured interviews were conducted with residents of Cajititlán (15 semi-structured and 5 closed interviews) using a non-statistically representative sample. The interviews followed a written script and aimed to explore residents’ perceptions of the Laguna Cajititlán landscape, with the goal of envisioning the safeguarding of Tlajomulco’s historical and cultural heritage (Jalisco, Mexico) from the respondents’ historical and life perspectives. Although the interview format was semi-structured, the script was designed to allow the inclusion of a narrative of their personal histories.

The selection of participants was carried out through purposive sampling, employing the snowball technique and considering a saturation criterion. Each interviewee led us to another resident who shared essential knowledge for this research. Residents ranged in age from 25 to 60 years, and 6 women and 14 men participated in the study.

The conducted interviews facilitated the coding of responses and analyzing the results provided by the interviewee as suggested in [

36], particularly when using the life history method, a technique that can be defined as “a case study of a specific individual that […] relies on all available information or documentation to reconstruct the biography as objectively, rigorously, and comprehensively as possible” [

38] (p. 110). Furthermore, the use of the life history methodology is particularly relevant to this study, as it “is the way in which a person deeply narrates life experiences based on the interpretation they have given to their life and the meaning they attribute to a social interaction” [

39] (p. 53).

It is important to note that the objective of the interviews in this research was to understand the perception of the inhabitants regarding the landscape of Laguna de Cajititlán, as well as their visualization and conceptualization of the cultural heritage of Tlajomulco, Jalisco, México. The interviews also aimed to collect general information about the interviewees (age, gender, occupation, and place of origin) and identify the main issues facing Laguna de Cajititlán. Additionally, reflections from local actors were gathered on topics such as (1) urban-rural issues affecting the lagoon; (2) pre-Columbian history and the lacustrine landscape; and (3) cultural heritage, namely (a) historical legends and beliefs and (b) tradition and collective identity. These topics functioned as coded categories for the analysis as well.

The fourth and final stage, which lasted until September 2024, focused on the collected information, which would be synthesized and analyzed to recognize the elements that conformed to the territory (social, cultural, economic, and environmental). During the fieldwork phases, field notes were compiled based on the results of the interviews conducted. From these interviews and the corresponding notes, it was possible to extract testimonials as well as relevant information about the knowledge and daily life, traditions, work and occupations, and worldviews of the local actors, helping to understand the lacustrine landscape. Photographs of the landscape were also taken during the visits and subsequently visually reviewed. The analytical dimensions from which the information was extracted and from which the field notes were analyzed can be seen in this Methodology section.

The results reflect the cultural perspective and its implications for the conservation and sustainability of the Cajititlán lacustrine landscape, particularly in the recent history of its landscape legacy through the tradition of the Procesión Los Santos Reyes.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Urban-Rural Issues of the Lagoon

The town of Cajititlán and the Indigenous towns settled along the lakeshore share a history of transformations within the lacustrine landscape. The inertia of metropolitan expansion in their territory manifested in a rapid population increase across the five towns surrounding Laguna de Cajititlán, leading to a decline in the quality of basic services, urban area maintenance, and infrastructure and thus endangering the lacustrine landscape. This growth is evident as between 2010 and 2020, the combined population of these towns increased from 19,758 to 33,422 inhabitants, while the town of Cajititlán experienced the most significant population growth, rising from 5323 to 17,818 inhabitants according to the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [

40,

41].

Likewise, in Cajititlán, during the same period, the number of inhabited private dwellings increased from 1075 to 5107. In contrast, although the Indigenous population remained small, it is noteworthy that the number of Indigenous inhabitants rose from 0.15% to 0.87% of the total population. Meanwhile, the percentage of people who speak an Indigenous language increased from 0.06% to 0.40% [

40,

41], reflecting the rapid urban-rural conurbation growth of the landscape (

Figure 3).

Some of the survey respondents were from the Arvento Housing Unit, located north of the Indigenous town of Cajititlán. This unit was developed by the construction company Casas Geo, which is now bankrupt: “On 23 November 2018, the date on which the General Ordinary and Extraordinary Shareholders’ Meeting of Corporación Geo ordered the dissolution and liquidation of the company” [

42]. This collapse led to the disorganization of housing deliveries, a lack of infrastructure, and the creation of underutilized spaces. According to the interviewees, these issues have resulted in daily struggles, such as inadequate maintenance of basic services, infrastructure failures, and sanitation problems:

“I come to work from Arvento. Back when my husband bought the house, we had a loan, but soon we started noticing security and cleanliness issues. I suppose it’s because of the overpopulation that there are so many of us, and for years they kept building and selling more houses. There wasn’t enough work for us, so many people from Arvento come down to Cajititlán to work. I found an opportunity here, and I also bring my daughter to school [sic]”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 1 September 2023).

As mentioned earlier, the population of Cajititlán and other local towns has increased in recent decades, bringing in new residents. Real estate developers seized this market opportunity. However, these changes have altered the landscape of Cajititlán as a rural town due to the expansion of Guadalajara’s urban sprawl, where new residents have either transformed or overlooked the area’s cultural and historical heritage.

Productive Activities in Laguna de Cajititlán: Between Development and Deterioration

The Laguna de Cajititlán is classified as an endorheic body of water of natural origin [

43] (p. 143). Its lacustrine territorial characteristics strengthen the social fabric of its inhabitants, as it has been a key element in their history, economic development, environmental dynamics, and cultural identity. In Cajititlán, fishing activities are an integral part of the lagoon’s landscape, along with agriculture, livestock farming, and tourism, which shape daily life. Additionally, as a wetland, Laguna de Cajititlán provides a habitat for diverse animal and plant life, making it a valuable landscape resource. Despite the region’s strong fishing tradition, recent years have seen a surge in agricultural activities, particularly the expansion of agave production. Although this industry has significantly boosted producers’ income, it may also have adverse effects on the lacustrine landscape:

“We have this problem now; we didn’t have it a year ago. The growth of agave production in this area is tremendous, and then there are a lot of agrochemicals used in the crops to prevent infections and keep them healthy”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 1 September 2023).

As previously analyzed, the benefits of the lagoon lie in its interaction with primary activities, which are essential and necessary for the proper development of the surrounding inhabitants. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that modern water storage techniques have allowed fishing, agriculture, and livestock farming activities in the Indigenous town of Cajititlán to continue. At the same time, ancestral customs and techniques coexist with these new practices to improve the lacustrine landscape through traditional agricultural methods, as illustrated in the following example:

“Using hillside planting [a traditional agricultural technique] allows us to grow native crops from the Laguna de Cajititlán region, this way, the fields remain cultivated, and the hills are occupied, helping prevent their disappearance”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 1 September 2023).

Likewise, the population integrates modern techniques, demonstrating an articulation between tradition and innovation:

“Keyline is a [modern] technique that enables proper water storage so that we can have it available whenever we need it for crops and to maintain soil fertility”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 2 September 2023).

Both traditional and modern techniques contribute to the sustainable use of the lacustrine territory for the benefit of its inhabitants. At the same time, they allow for the optimal use of the diverse aquatic species found in this landscape, such as fish (

Figure 4). Fishing is a traditional economic activity that the active fishermen of Laguna de Cajititlán carry out continuously using basic and traditional tools, which help protect other living species within the lagoon. The use of these agricultural and fishing techniques in the territory allows ancestral knowledge to be preserved as a legacy within modernity, aiming to optimize the primary activities of Cajititlán as a local town.

According to local fishermen, the waters of Laguna de Cajititlán contain certain pollutants, such as plastic waste (as seen in

Figure 4, which shows a plastic bottle of an ultra-processed beverage). These pollutants affect fish health and water quality. However, according to fishermen’s testimonies, they cannot stop fishing because it is a tradition and a vital part of their economic activities. This is particularly relevant, as their families’ economic stability depends on this activity:

“We have a fishing cooperative; we help each other. We wake up very early and let each other know where we’ve seen more fish bloom. But we also fish directly at the docks, throwing the net and catching small tilapias”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 1 September 2023).

It is important to note that consuming this fish is not recommended due to high pollution levels in the water [

8]. However, the sale of this product remains frequent, as fishermen take advantage of tourist arrivals to sell their daily catches. Additionally, they offer their fish to restaurants set up on residential patios throughout the area. Notably, consuming fresh fish directly from the lagoon has become an attractive experience for tourism. On the other hand, recreational activities contribute to tourism, which can generate higher income for the local population and possibly incentivize the conservation of their livelihoods. However, this could further deteriorate the water quality of the lagoon, simultaneously weakening the productive environment.

Fishing is a lacustrine landscape tradition and a heritage activity for its fishermen. Therefore, it must be preserved. As a legacy, fishing supports family livelihoods and allows the transmission of knowledge across generations, safeguarding both the cultural and historical activities of Cajititlán and ultimately providing an identity for this Indigenous town.

4.2. Pre-Columbian History and Lacustrine Landscape

It is believed that the first settlers around Laguna de Cajititlán belonged to an Indigenous community known as the Coca people, whose “domain extended along the entire shoreline of Lake Chapala and reached the limits of what is now known as the municipalities of Tonalá and Tlajomulco de Zúñiga” [

44] (p. 72–73). Records of this Indigenous community date back to the 15th century, indicating that the Coca people were descendants of the Aztec culture.

The arrival of the Coca people in the lacustrine territory marked the beginning of a significant relationship between the landscape and the sociocultural activities that took place in this site since pre-Hispanic times. According to the findings in [

45], it was determined that “[there are] some indications of archaeology along the northern shore of Cajititlán, as well as evidence from regional ethnohistory” (p. 4). Over time, this landscape underwent major social, environmental, cultural, and economic changes between the 16th and 17th centuries with the arrival of the Spaniards [

46]. This disruptive cultural clash led to the development of an important Catholic religious tradition within the Cajititlán community, which today is recognized as cultural heritage through the Procesión Los Santos Reyes. This tradition represents an ongoing process of transformation, sometimes forgetfulness, and also recovery of Indigenous Coca traditions, the mountainous landscape, and the cultural and religious practices introduced through Franciscan evangelization. According to testimonies from local residents who were interviewed, remnants of objects and tools that may have been used during pre-Hispanic times are still found in the region, as highlighted in the following statement:

“Over there, where the mesquite tree is, near the embankment, I found some clay pots. It looked like there used to be kilns because you can see a lot of burnt stones, charcoal, and ashes. So, I imagine that’s where they fired the clay to make figurines. Down below, there’s a material that looks like ‘topure,’ but it’s not; ‘Topure’ is what people from the mountains use; they make a small container out of sticks or palm grass and then coat it with a mixture of sand and lime. They use it to build vaults from the grass, and the water doesn’t break them apart. It seems like they extracted clay from there. Those kilns were like ovens for making pottery, and I’ve found many beads, small figurines, and broken pieces. I kept some, but I left others there. And up on Cerro Viejo, I’ve found stone axes. I used to wonder, ‘What would they need an axe for? It’s not even good for chopping wood.’ Then someone told me it was a type of weapon [sic]”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 31 August 2023).

This testimony suggests that there is evidence of pre-Hispanic or indigenous settlements around Laguna de Cajititlán. From this perspective, 15th-century Cajititlán was characterized as a lacustrine Indigenous town belonging to the Coca people, who are descendants of pre-Columbian cultures. Along with Cuexcomatitlán and Cuyutlán, these were settlements established along the shore of Laguna de Cajititlán.

This validates the statement by the authors of [

47], who argued that “the visual quality of the landscape is a recognized factor in the location of economic activities. Not only in the case of unique or exceptional settings with high aesthetic value but also for more common landscapes with less distinctive significance or an everyday character” (p. 110). This is particularly relevant since sociocultural activities are a defining characteristic of civilizations that establish their heritage through cultural and historical activities.

On the other hand, it is important to highlight that the Coca people who settled in Cajititlán were once part of the tlatoanazgo (chieftaincy) of “Coinan”, where “its inhabitants belonged to the Coca tribes, who, at the beginning of the 16th century, at the arrival of the Spaniards, were ruled by a chief named Ponze, Ponzehui, or Ponzetlán” [

48] (p. 5). Notably, in the 21st century, the Coca people remained in the collective imagination of the inhabitants of Cajititlán, who intangibly associate them with the lacustrine landscape. This is because the Coca people primarily inhabited the southeastern region of the state of Jalisco along the northern shore of Lake Chapala, which is located southeast of Laguna de Cajititlán about 30 km away, particularly in the community of Isla de Mezcala [

46].

Currently, the social and cultural struggle of the Coca people is primarily one of resistance in their ancestral territory, as well as the defense of Mother Earth, natural resources, and their autonomy as an ancient indigenous people. Their town was founded by a group of Aztecs during their journey to the Valley of México, where some remained, as noted in [

49]. Despite this historical background, the presence of the Coca people around Laguna de Cajititlán remains uncertain, leading to the following question: Where are the Coca people currently settled? To this, a local resident responded as follows:

“Well, they are in Mezcala! That’s exactly where you’ll find them. They have remained there for centuries, fighting for their lands!”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 2 September 2023).

From this perspective, it is understood that the Coca people relocated to another territory, a fate that may have also affected other indigenous communities that were subjected to persecution and domination by the Spaniards during their conquest [

50]. Recognizing this historical event is crucial to reinforcing the importance of preservation, the safeguarding of heritage, and the conservation of the lacustrine landscape, such as that of Cajititlán.

4.3. Cultural Heritage of Cajititlán: Between Legends, Traditions, and Recognition

The cultural heritage of Cajititlán is rooted in the traditions shaped over the years by the indigenous origins of its first inhabitants. Therefore, it is important to highlight that this rural town possesses elements of cultural wealth, representing a legacy that its residents have passed down through generations. Considering that through culture, humanity manifests expressions and symbols that define them as a society [

51], the transmission of history, knowledge, events, and languages among individuals of the same community also sustains the continuity of its cultural heritage.

Legends and Historical Beliefs of the Lacustrine Region

From the collective imagination surrounding Laguna de Cajititlán, several narratives have emerged that represent not only a territorial worldview but also the culture of this region. Notable among these are the legend of La Bruja Mochis [the Witch of Mochis], the Cacica Coyutla, and the traditional Procesión Los Santos Reyes. First, there is the legend of La Bruja Mochis, who is said to dwell in Laguna de Cajititlán. According to local residents, this entity is described as demanding and is believed to be “a witch who lives in the depths of Laguna de Cajititlán, disrupting the work of fishermen” [

52] (p. 203). Residents claim that this witch demands offerings in exchange for not drying up the lagoon, not reducing the number of fish, and not interfering with fishermen’s daily work, which serves as their primary source of income. Notably, elderly residents who were interviewed mentioned this entity:

“One time, they said the witch was angry because the fishermen didn’t give her an offering. Usually, when that happens, she breaks their nets so they can’t fish or hides the fish. Then, it happened that a girl went missing during a heavy storm. Years later, when the lagoon had nearly dried up, some fishermen found a small skull right in the center of the lagoon. We assume it was the girl who had gone missing, and because no offerings were made to the witch, she drowned her. That’s why fishermen must leave their offerings.”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 1 September 2023).

A second legend is linked to the arrival of the Spaniards in Cajititlán, centering on the figure of “Cacica Coyutla”, also known as “Mamá Coyotla” or “Cacica de Tonalá”. She was a female ruler who lived in the lacustrine region of Cajititlán. According to historical beliefs among indigenous residents, she is also known as the Cacica de Tonalá because she was the one who received Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán, one of the Spaniard conquerors who established colonial rule over the lacustrine region of Tlajomulco de Zúñiga around the year 1530 [

53]. As a high-ranking leader, and to instill Catholicism among the pre-Hispanic population, she “was the first to be baptized by the friars who accompanied Don Nuño de Guzmán” [

52] (p. 203). This event marked the beginning of the Spaniard conquest over the Cajititlán lacustrine territory, leading to the emergence of new traditions. Additionally, some local residents claim that Cacica Coyotla played a key role in resolving disputes that arose between the local people surrounding Laguna de Cajititlán:

“She was the mediator between the towns. If there was any conflict, she was the one who ensured a fair resolution. Thanks to her, there were no conflicts or fights among the inhabitants back then, in pre-Hispanic times, long before the Spaniards arrived [sic].”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 1 September 2023).

This statement highlights the significance of the Cacica Coyutla in the ideology of the inhabitants, as her legacy is even depicted in a mural in the Indigenous town of San Miguel Cuyutlán (

Figure 5).

This drawing represents the woman who was baptized at Cerro del Sacramento as a prelude to the evangelization of the indigenous community originally from Laguna de Cajititlán. In this image, the stoicism of the Cacica is evident, despite her subjugation to evangelization. The inhabitants of San Miguel Cuyutlán have incorporated the legend of the Cacica into expressions of their heritage, thus preserving their roots with respect and keeping their beliefs alive, albeit adapted over time to modern artistic expression techniques. It is evident that the cultural restructuring of the first inhabitants of Cajititlán with the Procession of the Wise Men highlights the power of the colonizers. However, over the years, this tradition has reclaimed the lacustrine environment as the entity that exalts devotion as an intangible aspect and the lagoon as a material aspect that combines the culture of the Indigenous community that utilized this lacustrine landscape. This relationship is shared in pairs, empowering the current community regarding local historical aspects.

4.4. Tradition and Collective Identity: The Procesión Los Santos Reyes

In general, it can be established that traditions continuously practiced over the years shape a shared identity among residents, when these traditions connect with other local towns, they strengthen the social fabric. One of the most notable characteristics of maintaining these traditions is the generation of solidarity among inhabitants in fulfilling the historical continuity of their culture. An example of this is the Procesión Los Santos Reyes. While this tradition has ancient origins, it has managed to reinforce bonds of trust among local residents. This procession originated from the discovery of artisanal figures made of mesquite wood representing the patron saints of the town. These figures were hidden after the sacristy of the Parroquia de Los Santos Reyes (Parish of the Wise Men) caught fire in 1905 and were later rediscovered in 1932. These symbolic figures were restored and placed once again on the altar of the parish’s sacristy, signifying not only the revival of the figures of Los Santos Reyes but also the strengthening of the Catholic religious heritage of the Indigenous town of Cajititlán.

According to testimonies from the residents, in 1905, the main altarpiece of the parish caught fire, destroying the figures of Los Santos Reyes made of mesquite wood. It is said that the presiding priest at the time, Tiburcio Lozano, ordered the burned figures to be buried in a secret location and commissioned the creation of three new figures outside of Cajititlán. As a consequence, there was a decline in the number of devotees and worshippers, as many preferred the original figures and considered them a historical material heritage of the parish and the Indigenous town of Cajititlán.

The original burned figures remained buried from 1905 to 1932, when an order was given to excavate and remove an anthill lodged in the sacristy of the Parroquia de Los Santos Reyes. During this excavation, the original figures were finally found. The newly appointed priest at the time commissioned an artisan from Cajititlán to restore the three figures ruined by the fire, ordering that they be placed once again on the parish’s altarpiece, where they remain to this day (

Figure 6).

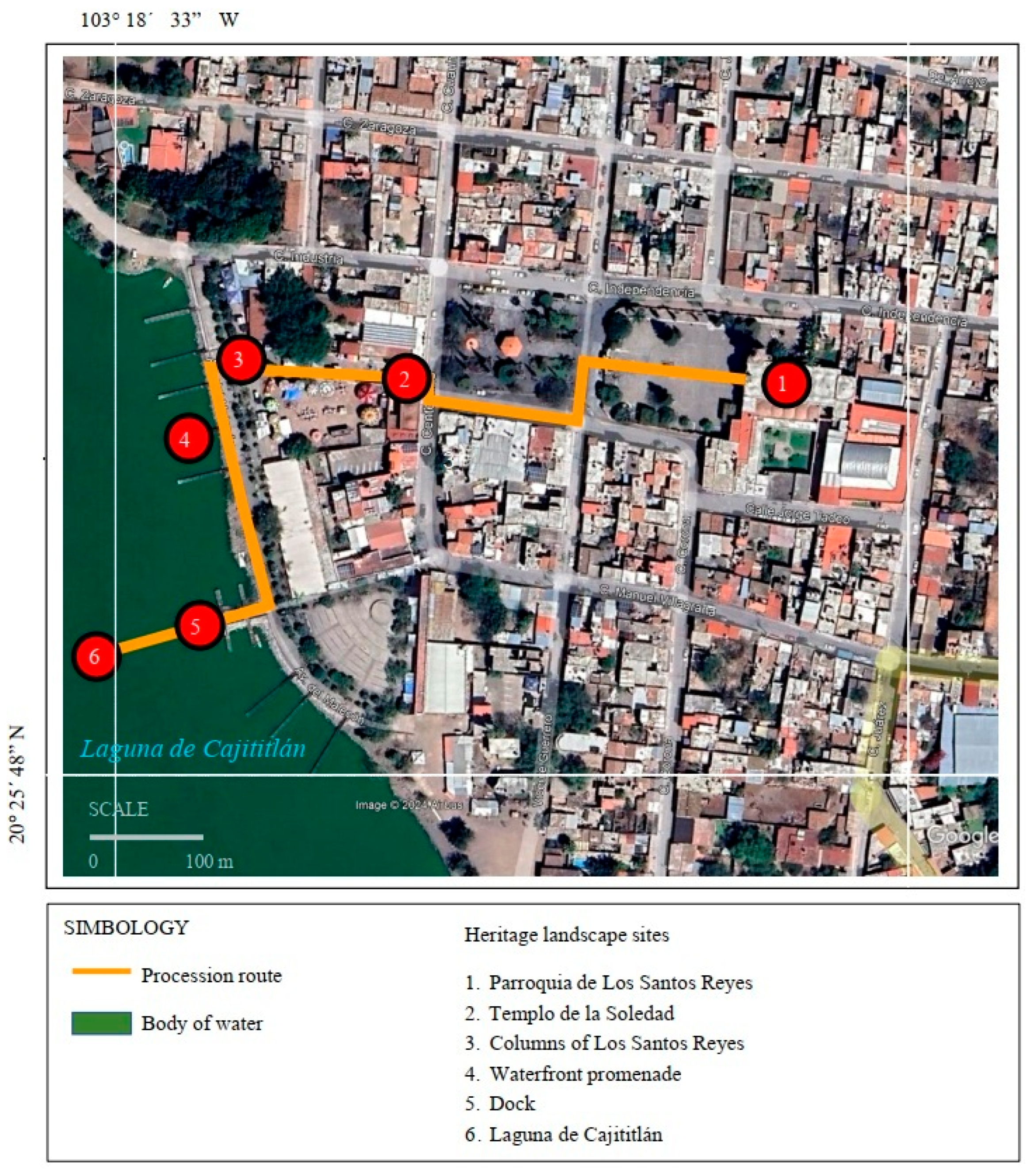

Finally, the historical material heritage of Cajititlán was recovered and restored, allowing for the renewal of faith among its inhabitants. This event led to the establishment of the tradition of the Procesión Los Santos Reyes, a celebration that takes place three times a year for different purposes. However, all processions follow the same planning and the same route through the streets of the Indigenous town of Cajititlán (

Figure 7).

The first procession is held to celebrate the patronal feast day, which takes place on 7 January each year and gathers “close to one and a half million visitors”, as described in [

54] (para. 2). In this regard, it is worth mentioning that, according to [

3], in ancient Tenochtitlán, “there were large [boats] used during religious festivals to transport priests with their offerings, while others carried the emperor and his court” [

3] (p. 21). Vestiges of such boats can still be seen in today’s Procesión Los Santos Reyes.

On the other hand, the second procession, held in May, symbolizes the community of Cajititlán’s request for a good rainy season. According to the worldview of the local inhabitants, this ritual promotes the replenishment of water through rainfall, which is particularly relevant because, as mentioned earlier, Laguna de Cajititlán is an “endorheic [closed] lacustrine body [that], unlike Lake Chapala, […] is not fed by a large river” [

43] (p. 143). Instead, it fills exclusively with rainwater from mountain runoff mainly from Cerro Viejo (

Figure 8), which is “the third highest mountain range in Jalisco” [

55] (para. 1) and is located in the Municipality of Tlajomulco.

The rainy seasons help replenish water supplies, which are used for livestock, agricultural fields in the region, and refilling Laguna de Cajititlán. Regarding this, a resident shared the following testimony:

“The lagoon dried up completely in 2001, but it didn’t last long. That year, about 80% of the lagoon’s water was recovered. Father Gerardo officiated a holy mass, right on the boardwalk, to pray for a good rainy season in 2001 and 2002. Many people now believe that the reason we had water was because of that holy mass. In May, we took Los Santos Reyes out again, made a short procession, and brought them down to the lagoon. That year, we placed them on their boats again. That’s when he asked me, ‘Do you want us to continue this celebration?’ I said, ‘Yes, Father, I would love for us to continue this tradition.’ And from that moment on, it was carried forward, by the next year, in 2003, it was no longer Father Gerardo, but another priest, I explained everything to him about how it had all happened. That’s why, here in Cajititlán, we honor the late Father Gerardo Sahagún, who ensured the continuity of the Procesión Los Santos Reyes in different months of the year and this tradition helps us have water.”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 3 September 2023).

Consequently, this new date in the lacustrine tradition holds intangible significance based on the devotion and worldview of the people of Cajititlán, yet it seems to materialize in favorable climatic conditions. This is reflected in the following statement:

“Father Gerardo told me: ‘Who wouldn’t benefit from a good rainy season?’ a good rainy season benefits fishermen, boatmen, merchants, and farmers who cultivate the land, as it ensures a successful harvest, so honestly, a good rainy season helps us a lot.”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 3 September 2023).

Finally, the third procession takes place in September, bringing together other residents and visitors, including tourists. This celebration commemorates the discovery of the destroyed figures of Los Santos Reyes found in the church’s sacristy. Although the original figures are not used in the procession due to their historical significance, the subsequent created images (

Figure 9) are used in this historical and cultural heritage tradition of the Indigenous town of Cajititlán.

Subsequently, the residents transport these figures and “take a three-hour boat ride across the lagoon […]. This tradition and pilgrimage have been carried out for more than 400 years” [

56] (p. 44). This cultural heritage, through this procession, demonstrates that “this tradition has endured over time, from the founding of the town in 1532 to the present day” [

57] (p. 43), showcasing the resilience of the local residents of Cajititlán against historical oblivion.

It is essential to emphasize that this procession traces its origins to the evangelization of Cajititlán in 1585 carried out by Spaniard Franciscan friars led by Friar Alonso Ponce, who commissioned the creation of the three original figures of Los Santos Reyes, which were “carved from mesquite wood, dating back to 1587” [

57] (p. 102). These figures represent the patron saints of the Indigenous town of Cajititlán—Melchior, Caspar, and Balthazar—and were placed in the altarpiece of the Parroquia de Los Santos Reyes after their rediscovery in 1932, where they remain to this day.

In this regard, it is important to mention that today, Hispanic culture has found architectural expression in the parish dating back to 1777. This is evident in the construction of the Parroquia de Los Santos Reyes, where the everyday life of the rural landscape coexists with devotional architecture. Despite urban expansion, the natural environment remains largely unspoiled, as seen in

Figure 10.

However, there are conditions that threaten and alter the lacustrine landscape, modifying the cultural heritage of a rural town that depends on devotion and prayers for a good rainy season to ensure a productive harvest. An example of this is the rise of monoculture farming, particularly agave production. The relentless expansion of agave cultivation in the region poses a serious risk to the sustainability of the lagoon. This situation highlights the importance of preserving traditional crops, such as maize, which are essential for maintaining the biodiversity and ecological balance of the area. Despite these challenging conditions, the territory has made progress in implementing agroecological systems:

“The thing is, yes, there’s a lot of monoculture here because there’s a lot of genetically modified maize, but there’s also a very interesting group of agroecological farmers, we’ve identified about 100 families practicing these methods.”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 1 September 2023).

The above reflects a spirit of adaptation and resilience in terms of protecting and preserving the genetic diversity of the territory.

4.5. Recognition and Conservation of Cultural Heritage

Finally, another form of legacy is expressed through heritage centered around devotion, which “brings together and activates other values that transcend [sic] beyond the strictly religious, including artistic, cultural, social, historical, economic, and even contemporary aspects. The key to this heritage is not exclusivity but representativeness” [

58] (p. 35). At its core, the cultural activities of the Indigenous town of Cajititlán, which are rooted in devotion, play a crucial role in preserving landscape heritage. The gathering of believers, tourists, and residents depends on the continuation of these traditions. In this sense, the Procesión Los Santos Reyes, viewed as cultural heritage, can influence the landscape, as the authors of [

16] explained, because landscape transformation occurs over time in a dynamic and changing way. It also occurs reciprocally between a society and the territory where it is inserted. This transformation is an essential element to be considered when analyzing the landscape. Following this logic, these processions help conserve the Cajititlán lacustrine landscape, particularly because the existence of the lagoon itself is essential to giving meaning and structure to this cultural heritage. As previously mentioned, this landscape reflects religious veneration. Additionally, as pointed out in [

59] (though in reference to the Magdalena Basin, which is also in Jalisco), heritage is deeply embedded in “the memory of a life connected to water [which] still prevails among some residents, particularly the elderly who lived alongside the lake during their childhood and part of their youth” [

59] (pp. 25–26). This could also apply to the recollections and collective memories of the elderly residents of Cajititlán.

Likewise, the Procesión Los Santos Reyes in Cajititlán is a type of heritage passed down to new generations of local inhabitants as a custom and tradition that must be preserved. However, currently, the younger residents of Cajititlán show little interest in preserving cultural traditions or even religious practices. This is sometimes due to the disconnect between these activities and their current reality and, in other cases, due to a lack of knowledge about them. This abandonment may occur because “there is no sense of appreciation” [

60] (p. 104) among this age group. In this sense, older generations play an important role in preserving heritage and ensuring its sustainability, as they seek to pass down and transmit the knowledge and traditions of their community. This effort fosters the conservation of history and the remembrance of the culture of the Indigenous town of Cajititlán.

This, in turn, could result in an increase in devotees, which would translate into the continuity of traditions and activities carried out within the lacustrine landscape. The following local resident described part of his childhood responsibilities and expressed pride in sharing them:

“My grandparents were from here; they were dedicated to farming, to growing maize, I worked as a little boy in the fields, planting crops, as I grew older, I learned to handle the ox team. I worked with a yoke of oxen. The lagoon was very clean back then, I would go in, and the water would reach my knees, I would look down and see the sand, we used to gather little shells, like clams, similar to the ones found in the sea, we would fish for them and eat them [sic].”

(Local Resident, personal communication, 31 August 2023).

This testimony provides insight into the activities and lacustrine practices that were an integral part of the childhood experiences of elderly residents. These activities not only reflect their way of life but also highlight the subsistence strategies they employed by utilizing the resources provided by Laguna de Cajititlán.

Similarly, the residents of Cajititlán demonstrated great interest in preserving their historical and cultural lacustrine heritage. While there may be examples—though not in the Laguna de Cajititlán region—where cultural heritage has been destroyed and forgotten (like the demolition of a religious temple from the 18th century in the town of San Pablo del Monte in Tlaxcala Mexico by the inhabitants themselves, even though it was considered “a historical vestige, unique [and] relevant, had lost its social meaning” [

60] (p. 104)), in the face of the fragility and vulnerability of historical and cultural heritage, communities develop practices, tangible manifestations, and intangible resources aimed first at its identification and recognition and later at its protection. One such example is the reenactment of the Procesión Los Santos Reyes (

Figure 11).

The image of the columns represents tangible cultural heritage that contributes to the construction of historical, cultural, and even touristic spaces, enhancing not only the lacustrine landscape but also reaffirming the commitment of the residents of Cajititlán to preserving and promoting their traditions.

4.6. Cultural Heritage for the Conservation of the Lacustrine Landscape: Brief Recommendations

As an Indigenous town, Cajititlán has roots deeply embedded in tradition and collective identity, which are expressed through the veneration of Los Santos Reyes. This practice encourages residents to prioritize conservation of the lagoon, as this process can serve as a catalyst for initiating sustainability efforts aimed at preserving the body of water.

Furthermore, the existing unity among the five Indigenous towns surrounding the lagoon provides an opportunity to amplify the voices, opinions, and knowledge of the local residents, allowing for a clearer identification of the challenges faced. and the articulation of these communities, which may lead to potential solutions for safeguarding the lacustrine landscape, especially given that public authorities and institutions have taken little action. However, this presents a window of opportunity to promote conservation strategies, including collaborations with academic institutions or other civil organizations.

Additionally, the unity among the town’s residents materializes in various communal efforts, such as decorating the streets, allocating time and human capital to these activities, and maintaining the cleanliness of public spaces. (The community also engages in waste collection, sweeping the streets and plazas to prevent debris from reaching the waterfront.) This collective social capital represents a valuable asset that can lay the foundation for active collaboration and long-term landscape conservation.

On the other hand, a notable aspect of the worldview of the local inhabitants is their perception of the lagoon as a living entity. This perspective can be leveraged as an advantage for the implementation of local conservation strategies. The local residents of the region hold a deep respect and veneration for the landscape, including the lagoon itself and the local genetic diversity, flora, and fauna that compose it. When combined with the devotion to Los Santos Reyes (as the procession is a manifestation of gratitude for the natural resources received), this cultural practice can be seen as a virtuous cycle in the pursuit of conservation and sustainability of the lacustrine landscape. These conservation efforts led by the residents reflect their devotion and intention to connect the Procesión Los Santos Reyes with a prosperous rainy season. Through this, they keep their traditions alive, while also ensuring the continuity of productive activities such as agriculture and fishing.

The processes previously mentioned in this section also correspond to other activities and uses of the landscape. As an Indigenous town, Cajititlán is considered a tourist destination for various visitors, and it is during the three dates of the Procesión Los Santos Reyes that the largest influx of tourists can be observed. This procession moves through the streets of the town before continuing in boats navigating across the lagoon. Alongside these ceremonial practices, other tourist activities also take place, such as boat rides for scenic contemplation of the lacustrine landscape, wildlife observation of endemic species, and guided visits to the cultural and religious center. As a result, tourism generates income for the community. However, tourism always has two sides. A potential negative aspect is that some of these activities may contribute to “predatory tourism”, meaning that irresponsible use of services can lead to pollution of the lagoon. This threatens the lacustrine ecosystem, which serves as a habitat for various animal and plant species. Additionally, the lack of basic sanitation services in the region, an overwhelmed waste collection system, and insufficient drainage infrastructure, especially considering the increasing number of restaurants, convenience stores, and hotels, can lead to the generation of organic and inorganic waste. If not properly managed, these waste materials often end up in the lagoon, polluting the lacustrine landscape.

Given this situation, it would be worthwhile to redirect the economic benefits of tourism toward developing conservation and cleaning programs for the lagoon. Likewise, the implementation of ecotourism could be considered as an alternative to predatory tourism, which often results in noise pollution, littering, and the extraction of natural elements.

Along the same lines, it is important to highlight that although the reach of this festivity is limited to the three annual dates of celebration, throughout the rest of the year, Cajititlán continues to receive a regular influx of visitors, particularly to the waterfront promenade and the recreational activities on the lagoon. Therefore, even though the Procesión Los Santos Reyes represents a key aspect of Cajititlán’s identity and that of its residents, it remains confined to specific commemorative dates. The rest of the year, local residents follow their usual daily routines, and fishermen and farmers continue working to support their families. As such, the cultural value of this event should extend beyond the specific procession dates to ensure its long-term impact and preservation.

In this regard, conservation policies should aim to recognize Laguna de Cajititlán as a Ramsar site, due to the potential and ecological characteristics of its lacustrine ecosystem. It is important to mention that Ramsar sites focus on “creating and maintaining an international network of wetlands that are important for the conservation of global biological diversity and for sustaining human life by preserving the components, processes, and benefits/services of their ecosystems” [

61] (p. 9). This initiative stems from the Ramsar Convention, which functions as an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of wetlands. Such recognition would grant the lagoon regional, national, and international importance, fostering discussion about its challenges and potential solutions in public forums. Additionally, the Procesión Los Santos Reyes could be incorporated into the Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage within the Sistema de Información Cultural [Cultural Information System] (SICMEXICO). This would give the tradition cultural relevance and protection through public policy agendas and facilitate its integration into state development plans for the region.

On another note, it was evident that there is a lack of information regarding the pre-Hispanic culture and history of the Coca people. As a result, an important historical and cultural initiative would be to strengthen research, documentation, and evidence collection through testimonies, photographs, documents, and archives to preserve and highlight the indigenous heritage of Laguna de Cajititlán.

Finally, in order to better highlight the substantial contributions of the work in terms of this Results and Discussion section, the following summary (

Table 1) is included.

5. Final Reflections

Cajititlán is an Indigenous town along the shores of a vast lagoon which evokes the historical landscape of a culture and heritage that has gradually faded over time across the riverside territory, but this cultural legacy remains alive through the traditions of the local communities, which continue to recover remnants and traditions from different cultural influences, such as the pre-Columbian Coca indigenous culture of Mesoamerica, the mestizo Coca-Hispanic culture, and the present day urban rural cultural identity.

Currently, the elderly residents recall memorable times spent at the lagoon’s waterfront promenade, which once served as a gathering place and a site of contemplation during the Procesión Los Santos Reyes. This procession continues to be a defining element of the cultural heritage within the lacustrine landscape. Experienced along the streets and pathways surrounding the boardwalk and the lagoon, the procession unites the community through prayers and hymns rooted in their religious worldview. This event is socially significant to the community to such an extent that the Procesión Los Santos Reyes in Cajititlán can be considered not just cultural expression but a materialization of heritage passed down from the original inhabitants of the lagoon. These residents demonstrate a keen interest in preserving their traditions and indigenous roots as part of their deep connection to the landscape. The communities actively participate in this annual event, which has strengthened the social, cultural, and historical fabric of their heritage among the riverside towns and their inhabitants. Given the fact that cultural heritage reflects a process of societal appropriation concerning a set of tangible and intangible assets deemed worthy of preservation and transmission, the Procesión Los Santos Reyes deserves to be preserved and celebrated.

In this regard, it is concluded that cultural heritage and the lacustrine landscape share a bidirectional correlation, since the Procesión Los Santos Reyes, as part of daily life, devotion, and faith in Cajititlán, contributes to the construction of identity among riverside inhabitants and promotes the multifunctional use of territories, particularly through tourism-related activities. This, in turn, supports the implementation of conservation practices for the lacustrine landscape, specifically Laguna de Cajititlán. Simultaneously, preservation of the lacustrine landscape enables the sustainability and reproduction of cultural heritage, creating an interdependent relationship between these elements. This research is significant because there is a knowledge gap regarding academic studies that explore the potential of cultural heritage in contributing to the conservation and sustainability of lacustrine landscapes. This is not only relevant to the study of Laguna de Cajititlán but also other lacustrine landscapes worldwide where cultural heritage plays a crucial role in shaping and preserving the identities of local communities.

On this matter, it is important to highlight that the lessons learned in this present study can be recalled to identify the role that cultural heritage can play in the conservation and sustainability of other lacustrine areas, such as Lake Nakuru located in Kenya, which sees its landscape threatened by sewage pollution derived from urban growth as well as the productive development of the region “[…] and by the loss of conservation status of part of its Ramsar site area, and hence the loss of that natural habitat” [

62] (para. 2). Therefore, the safeguarding of this lacustrine landscape, as well as the natural heritage that defines it, could involve an urban development model that standardizes, in principle, the implementation of necessary infrastructure without affecting the natural habitat, which in turn allows it to continue belonging to the RAMSAR list. It would also be worthwhile to include all stakeholders involved in the lacustrine landscape conservation process to ensure its sustainability.