1. Introduction

A health emergency was officially declared by the World Health Organization [

1] in early 2020:

“WHO has been assessing this outbreak around the clock and we are deeply concerned both by the alarming levels of spread and severity, and by the alarming levels of inaction…”

Since then, the health emergency caused severe health issues in populations across many countries worldwide, including widespread morbidity and substantial mortality. Health policy measures and countermeasures imposed social pressure and restrictions on populations in numerous countries. In addition, the consequences of the implemented health policies caused economic (financial) and social damage across various sectors, including employment, education, and business. Some of the effects are still felt today even if restrictions have ended. Nevertheless, several countries succeeded in keeping infection rates very low before the vaccines were approved and vaccination efforts began in early 2021. These countries managed to limit both morbidity and mortality among their populations [

2,

3]. They include Australia, China, Finland, Hong Kong (special administrative region), New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, and Taiwan. These countries also succeeded relatively well in reducing social pressure and restrictions, as well as mitigating economic damage across employment, education, and business sectors. Although they did better than many others, the situation was still a difficult for these countries. Compared to many other countries that experienced high rates of infection, morbidity, and mortality—such as several European, South American, and North American nations—these countries demonstrated more effective control [

2,

3]. Overall, countries in Asia, Oceania, and, to some extent, Africa appear to have handled the health emergency satisfactorily.

The WHO’s International Health Regulations (IHRs, 2005) [

4] provide a legally binding foundation for health emergency preparedness. The IHRs require countries to detect, assess, report, and respond to public health threats, designate National IHR Focal Points, and maintain core capacities for surveillance and emergency response. The WHO [

4] supports countries through training, tools, and coordination during health emergencies, including the declaration and management of Public Health Emergencies of International Concern (PHEICs). Some countries still do not fully meet all the IHR requirements, despite the framework being in place for years. Our toolkit complements this framework by translating these obligations into operational success factors, such as institutional coordination, data interoperability, and adaptive capacity.

To deepen the conceptual basis of our framework, we draw upon network and complexity theories [

5], which frame governance as an adaptive system characterized by emergence, non-linearity, and self-organization. These perspectives offer a foundation for understanding transformational leadership, feedback loops, and institutional flexibility as critical elements in preparing for and responding to health emergencies. These concepts can sometimes feel abstract, but they help to make sense of what happens in crises. Incorporating evidence from recent interdisciplinary research further enhances the relevance of our approach. Liao et al. [

6] illustrated how environmental reforms—such as clean heating policies—can generate significant public health co-benefits, reinforcing the need for intersectoral planning. This bolsters our argument for integrated governance that aligns health objectives with broader sustainability and environmental goals.

In parallel, Taghvaee et al. [

7] underscored the challenges posed by fragmented institutional structures and the critical role of strong governance in achieving Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG 3). Their findings reinforce our emphasis on coordinated, well-resourced systems as foundational for effective health emergency preparedness. Some institutions still struggle to coordinate even when the need is urgent and obvious.

Taken together, these contributions position our proposed toolkit within a broader ecosystem of scholarship on pandemic preparedness, sustainability, and public policy. By integrating theoretical and empirical insights, we seek to offer a robust, context-sensitive framework that can inform institutional design and guide policy responses in future health crises.

Oue study draws on a wide array of international sources that reflect a broad spectrum of control measures implemented across countries. For instance, Haug et al. [

8] ranked over 4000 interventions globally; Islam et al. [

9] compared distancing measures in 149 countries; and Li et al. [

10] modeled R-value changes across 131 nations. These examples show that the countries referenced in our study were not prioritized but selected based on the availability of rich and contrasting policy documentation. Some countries had much data available while others had very little.

Table 1 summarizes key studies on health emergency measures and countermeasures across different countries. It lists the authors, scope, intervention focus, and main findings.

Our study does not specifically focus on health, social, and economic conditions, but rather on the success factors related to measures and countermeasures for planning, implementing, and managing sustainable health policies. These factors can be applied in relation to a health emergency toolkit across health, social, and economic criteria within the society in question. In our view, previous work and theoretical models have suffered from a degree of myopia. Sometimes they focus too narrowly and miss the wider picture that policy decisions affect. The focus of our study is therefore an attempt to frame and contextualize potential success factors for sustainable health policies within a broader societal context. It is also an effort to outline a health emergency toolkit that can support the development of sustainable policies and assist decision-makers in governments and health authorities. Our interpretation is that the health emergency has revealed that governments and health authorities worldwide were not adequately prepared to determine what, when, and how to implement sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures. The actions that were taken do not always appear to have been grounded in scientific knowledge or practical insights.

No previous research appears to have examined health emergency toolkits or assessments in order to plan, implement, and manage sustainable health policies. It also appears that no model or framework has been reported that identifies success factors for measures and countermeasures in the practical work of planning, implementation, and management of such policies. In addition, we have found no toolkit capable of assessing the impact of health emergency strategies on the health, social, and economic criteria of societies. Despite our best efforts, we were unable to find anything suitable. Our research objective is therefore to frame and contextualize the impact of sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures as part of a health emergency toolkit of assessment. Specifically, the objective is to examine key success factors of sustainable health policies across countries, with the aim of protecting their populations.

The health emergency toolkit of assessment developed in our study contributes by outlining a set of success factors for sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures across countries, with the goal of protecting their populations. In addition, this toolkit enables flexible adaptation and application across different national contexts. Consequently, it is not context-specific (e.g., limited to one country) but instead draws upon factors implemented across multiple countries, rendering them, to some extent, universally applicable for protecting populations in the future. We believe that this toolkit can help countries in the future, even if the next emergency takes a different to the last one.

Previous studies that reported on health emergency assessment primarily focused on health policy measures and countermeasures at an operative level [

11,

15,

16], whereas our study adopts an aggregated perspective to develop a health emergency toolkit of success factors for sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures aimed at managing the impact of a health emergency. This toolkit can be considered and applied in the planning, implementation, and management of health policies. It may also be adapted to the specific conditions of different societies. We hope that users will adjust the toolkit rather than apply it blindly.

2. Methods

Our study employs a qualitative and exploratory design to identify key success factors for effective health emergency preparedness and response. Rather than conducting a systematic review in a strict sense, it follows a document-based comparative policy analysis, applying an inductive thematic approach [

36] to extract insights from diverse national responses to the health emergencies that emerged in 2020 and beyond. We did not aim for exhaustive coverage but rather for analytical depth across contrasting cases.

The analysis draws on a purposive sample of both academic and gray literature, including reports from governments, international organizations, and institutional sources that document public health responses across a range of countries. We aimed to include a variety of countries; however, it should be noted that many countries around the world lack valid or reliable data. Some countries simply do not publish or share the kind of information we required. The studies selected were included based on two criteria: (i) inclusion—studies must include representation from one or more countries; (ii) exclusion—studies were excluded if they lacked reliable data on a country’s response, particularly in relation to case examples or detailed policy descriptions, such as in cases of limited transparency or poor data accessibility.

An effort was made to ensure geographical diversity by incorporating both high- and middle-income countries, as well as a range of governance models and phases of health emergency response. Nevertheless, data availability and reliability presented limitations that affected the inclusion of certain regions. We would have liked to include more countries from underrepresented areas, but the data were simply not available.

The analytical process was guided by the principles of constructivist grounded theory [

37], which emphasizes emergence, reflexivity, and iterative interpretation. Although no formal coding software or systematic matrices were used, the analysis followed a rigorous, iterative, and comparative process to identify recurrent enabling conditions and strategic components. Key success factors were selected not solely based on frequency, but on their recurrence, relevance, and consistency across different contexts. This approach aligns with interpretive traditions common to qualitative research in public health and policy. We did not use software but carefully reviewed everything more than once. Techniques such as Delphi panels or surveys may further strengthen the empirical foundation, relevance, and generalizability of the proposed success factors.

The research process is structured into three phases to frame and contextualize the impact of sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures as follows: (i) observations and content analysis; (ii) empirical support through illustrative examples; and (iii) development of a health emergency toolkit to assess success factors of sustainable health policies across health, social, and economic criteria relevant to societies. We found this phased approach to be helpful for keeping the analysis focused and manageable.

- (i)

Our study is grounded in observations of sustainable health policies across several countries. It is also based on content analyses of diverse sources, including press conferences, interviews, reports, and online documents from governments, ministries, and economic, social, and health authorities. Our observations of the measures and countermeasures undertaken by these institutions guided the selection of relevant and timely sources. Consequently, a judgment-based selection process was applied to develop the health emergency toolkit of assessment, as well as to identify success factors for planning, implementing, and managing sustainable health policy strategies. We knew this approach had limitations, but it allowed us to focus on real-world actions. Altogether, these sources enabled us to frame and contextualize the measures and countermeasures taken, which in turn revealed key success factors of sustainable health policies to protect the population.

- (ii)

Our observations and content analyses used to frame and contextualize the impact of sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures were subsequently supported by a judgment-based process for reporting a selection of illustrative examples. These examples are drawn from official statements and published artifacts from governments, ministries, and economic, social, and health authorities, as well as from research and scholarly sources. The illustrative examples serve to provide empirical support, demonstrating the value of hands-on practices related to the measures and countermeasures undertaken in sustainable health policies. We chose examples that clearly showed how theory was turned into real policy actions.

- (iii)

Altogether, the combination of observations, content analyses, and empirical support contributes to the development of a health emergency toolkit of assessment that ultimately consists of ten factors. All of these factors are intended to be applicable for evaluating sustainable health policies across countries, with the goal of protecting the populations in question. The factors listed in the toolkit also aim to support countries in planning, implementing, and managing sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures. We tried to ensure that each factor reflects lessons that can be used by decision-makers. Illustrative empirical examples for each factor are therefore drawn from different countries and continents. Our aim is to encapsulate each potential success factor of sustainable health policies in a way that addresses impacts at a societal level and remains applicable to cross-country planning, implementation, and management efforts.

Our aim of this study is intentionally broad, reflecting the lack of conceptualizations in previous research. In fact, a health emergency toolkit and the identification of success factors for sustainable health policies appear to represent a “white spot” marked by a significant knowledge gap. Previous studies typically focused on specific areas or actions (e.g., [

17,

18]), while this study seeks to offer a helicopter view of the measures and countermeasures applied in health emergency strategies. We chose this broader view because, as of yet, no one else had attempted to map the entire landscape.

It should be noted that the ten success factors are not drawn from any existing policy texts; rather, we labeled them ourselves, based on our observations of various sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures undertaken by governments and health authorities. We gave them names because no one had formally identified or grouped them in our way before.

The development of the proposed health emergency toolkit of assessment provides a foundation for deepening our understanding of success factors in future research and hands-on practices—areas that remain beyond the scope of our study. We believe our study represents a first step toward developing a health emergency toolkit with guidelines and practical recommendations for governments and health authorities. It may sound a somewhat ambitious, but we felt the gap was too large to ignore. Based on global experiences, it became clear that many governments and health authorities were fumbling in the dark. Sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures implemented across countries lacked coherence and were not aligned with a consistent health emergency toolkit. This health emergency has revealed that the knowledge and insights available to governments and health authorities were insufficient.

3. Results

The sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures identified across several countries in the inductive research process were grouped into factors that we labeled to reflect their essence.

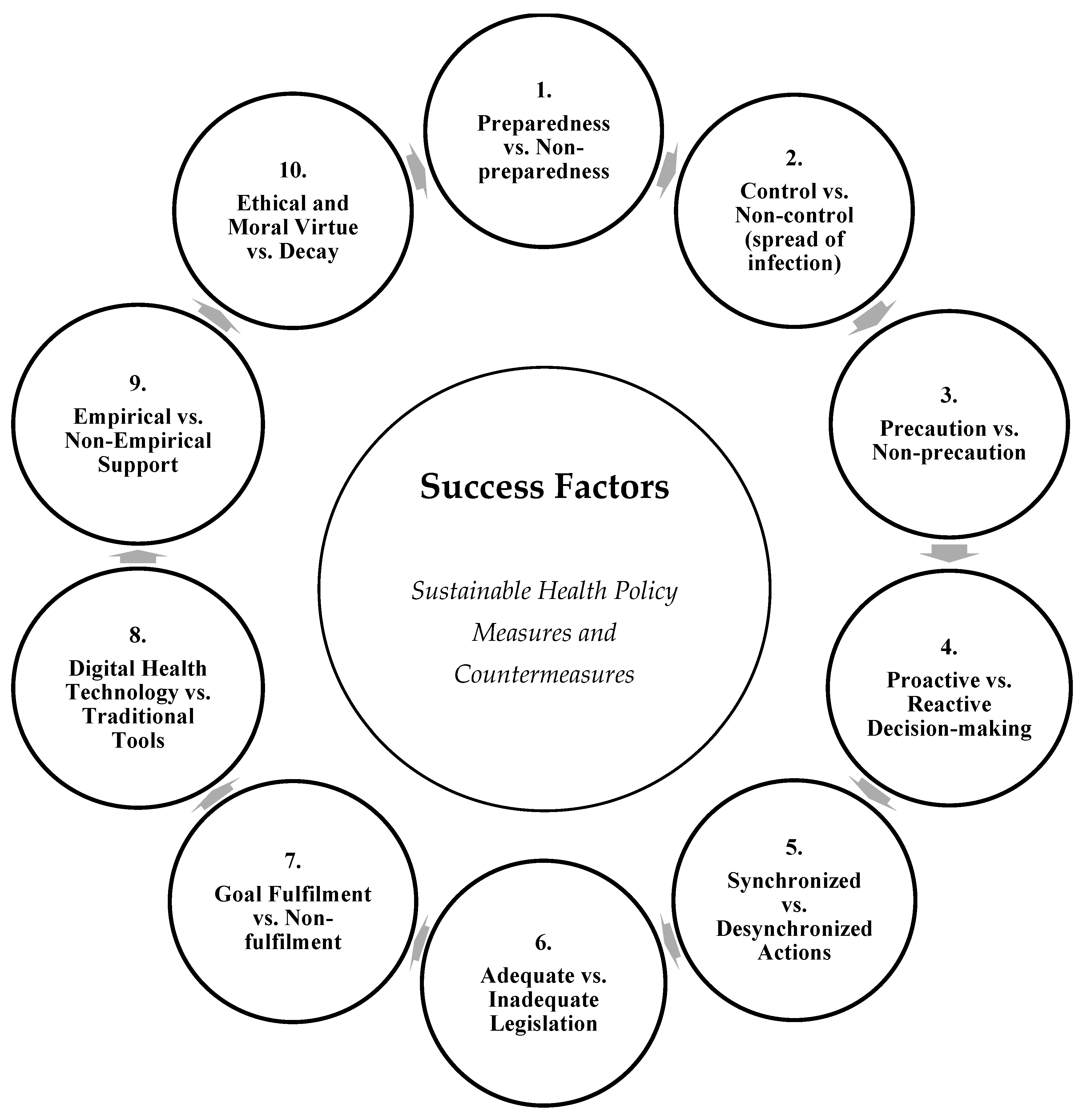

Figure 1 illustrates ten potential success factors for sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures. We contend that the factors presented in our study may be relevant both individually and collectively in developing a practical health emergency toolkit of assessment for future crises. We think some factors will matter more in some places than others, but all are worth considering. We also contend that these factors may serve as a foundation for establishing criteria for sustainable health policy plans, supported by guidelines for implementation, management, and control in the future.

Inevitably and undoubtedly, health emergencies will arise in the future, and the lessons learned from the previous one must be taken seriously to establish sustainable health policies that determine what, where, when, and how measures and countermeasures should be undertaken to protect populations. The factors described in relation to

Figure 1 highlight several areas that we argue provide compelling examples for improving the future planning, implementation, and management of sustainable health policies, along with the appropriate measures and countermeasures. It would be a mistake to ignore what previously worked and did not work.

It should be noted that

Figure 1 also displays ten converse factors that potentially render the planning, implementation, and management of sustainable health policies and related measures and countermeasures insufficient and, at worst, result in failure, to protect populations from health, social, and economic issues.

3.1. Preparedness Versus Non-Preparedness

This factor underscores the importance of having pre-established plans, stockpiles, and sufficient health system capacity. Countries with stronger preparedness mechanisms were able to mount more rapid and coordinated responses. It was obvious that being ready in advance made a significant difference.

It should be noted that the toolkit is not intended to be exhaustive or a complete list of success factors, but rather a foundation that can be expanded in future research and applied in hands-on practices for the planning, implementation, and management of sustainable health policies. Altogether, the factors form a toolkit of sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures aimed at protecting populations, as described in the subsequent section. The figure illustrates a series of dualities that emerged from the comparative analysis, showing how strategic choices in governance and policy orientation shaped health emergency outcomes. Some of these contrasts were quite striking when we compared different countries. Together, these categories offer a comprehensive lens through which to interpret the effectiveness of health emergency governance. The dualities also underscore that success was not the result of isolated actions, but of coherent, ethically grounded, and systemically aligned approaches across all domains. Preparedness is about planning, implementation and control based on a health emergency strategy that outlines what, where, when, and how measures and countermeasures should be undertaken across health, social and economic factors.

An illustrative example of preparedness as a relevant success factor is evident from the Norwegian government [

19], which outlined a comprehensive series of plans, including the following:

“…National health preparedness plan; National strategy for emergency preparedness for incidents involving hazardous substances and infectious diseases; National emergency preparedness plan for outbreaks of severe infectious diseases; Norwegian National Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Plan; Action plan for better infection control…”

Norway seemed to have prepared for many possible scenarios well before the health emergency even started.

Another illustrative example of this factor comes from the healthcare sector in Finland, as noted by Tiirinki [

20], p. 650:

“…five university hospital districts are legally obliged to plan and coordinate care in their catchment areas, while all hospital districts and municipalities are responsible for epidemic preparedness and management in their respective geographical areas…”

This setup shows how Finland spread responsibilities clearly across different levels of the health system.

3.2. Controlled Versus Non-Controlled Spread of Infection

This factor reflects the capacity of governments to contain the spread of infection through timely interventions such as lockdowns, testing, and contact tracing. Where control was inadequate, outbreaks were prolonged, and mortality rates increased. Some nations waited too long to act and paid the price later.

Testing, tracking, and isolating individuals are essential for mapping the progression of infection within populations. Controlling the infection rate (i.e., incidence of cases) has proven crucial in reducing morbidity and mortality. A lack of control poses a serious threat and may escalate into a situation that becomes unmanageable, leading to widespread morbidity and mortality. When infections spiral, it is already too late to stop them easily. In fact, control is critical, as it may be a key factor negatively influencing outcomes across health, social, and economic criteria.

An example of this factor was seen in Taiwan, as noted by Kuo et al. [

21], p. 1928:

“Taiwan has strictly followed infection control measures to prevent spread of the coronavirus disease. Meanwhile, nationwide surveillance data has revealed drastic decreases in influenza diagnoses in outpatient departments, positive rates of clinical specimens, and confirmed severe cases…”

This suggests that strong health emergency controls had a wider benefit for other infectious diseases too.

3.3. Precaution Versus Non-Precaution

Precautionary measures—such as early closures, mask mandates, and travel restrictions—proved effective in mitigating the spread of infection. In contrast, delayed or absent precautions led to preventable escalation. Some countries waited and ended up having to take even tougher measures later.

A success factor for protecting populations appears to rest on the guiding principle of “better safe than sorry”, where precaution underpins the measures and countermeasures undertaken to minimize the spread of infection, morbidity, and mortality. Essentially, the principle of precaution refers to sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures that strive to avoid unnecessary negative consequences for the population. For example, carelessness (i.e., lack of precaution) may lead to higher infection rates and greater costs in terms of human suffering and death tolls: once things get out of hand, it is much harder and more expensive to bring them back under control. Social pressure and restrictions, along with severe economic consequences, may also worsen significantly.

One illustrative example of precaution as a relevant success factor comes from China, as described by Tang et al. [

22], p. 637:

“The dynamic impact of the increasingly strong measures of the Chinese government has not been fully captured. Unprecedented interventions, including strict contact tracing, quarantine of entire towns/cities, and travel restrictions, have added and will add further uncertainty to the analysis of the epidemic.”

This shows that China took bold and early steps, even if the outcomes and implications were still hard to fully assess at the time.

Yet another example of precaution as a key factor comes from Vietnam, as noted by Nguyen and Vu [

23], p. 480:

“As a precaution against the spread of the disease, Vietnam swiftly took actions with a variety of preventive and control measures, including shutdown of schools, language centers, and other nonessential services and businesses.”

Vietnam moved fast to shut things down before the situation escalated, showing how early action can matter significantly.

3.4. Proactive Versus Reactive Decision-Making

Proactive governance involves the early recognition of risk and the implementation of anticipatory measures. In contrast, reactive approaches often result in delayed responses and overwhelmed health systems. Waiting too long usually meant scrambling to catch up once the damage had already occurred.

Decisions to implement sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures should be proactive rather than reactive. It is also essential that the actions undertaken are not too limited in scope or number. There is a need for the measures and countermeasures imposed to be both sufficient in scale and strict enough to manage the impact effectively. Doing too little too late was a mistake some governments made, and it cost them dearly.

A further example of proactive governance as a success factor comes from Vietnam. Dinh et al. [

24], p. 3 reported:

“Unlike affluent Asian countries with GDP per capita of twentyfold higher, Vietnam could not afford a community-wide testing program. Instead, Vietnam has focused on cost-effective measures. At the center of its active case-finding is extensive contact tracing and health declaration for all. In combination with case isolation, mass quarantine, and mass masking, these measures control infections at source, even asymptomatic cases. It is early recognition of the outbreak, swiftly adaptive actions, production line of medical essentials and PPEs, and the public’s cooperation that makes these strategies feasible.”

Vietnam did not have the same resources as wealthier countries but acted quickly and strategically with what it had.

3.5. Synchronized Versus Desynchronized Actions

This factor refers to the degree of alignment—or lack thereof—between different levels of government, as well as coordination with international actors. Synchronization enhanced both efficiency and public compliance. When all the different relevant actors worked towards the same goal, things functioned better.

Sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures that are planned and implemented should be synchronized rather than desynchronized. The outcome of such measures, aimed at protecting populations, depends on timely implementation—not delayed action. The effectiveness of control measures provides a foundation for assessing sustainable health policies in relation to their timing and the extent to which the actions can be considered successful in protecting the population. Too often, actions came too late to make the difference they could have.

An example of synchronized actions as a relevant success factor is provided by Ebrahim et al. [

25], p. 208, who state:

“…we call on all countries and communities to act synergistically and emphasize the need for synchronized pan-global mitigation efforts to minimize everyone’s risk, to maximize collaboration, and to commit to shared progress.”

This highlights how working together across borders is not only ideal—it is essential in a global health crisis.

Another example of synchronization as a key factor comes from China. Liu, Bai, Shen, Pang, Liang, and Liu [

26] conclude:

“Our study quantified the relationships between mobility patterns and epidemic trajectory in China and highlighted the importance of synchronized travel restrictions across cities.”

It is clear that if only some cities acted, the virus simply moved around and continued to spread.

3.6. Adequate Versus Inadequate Legislation

Clear, adaptable, and rights-based legal frameworks facilitated swift public health action. By contrast, legislative gaps or rigid systems hindered the enforcement of necessary measures. When laws were not ready or flexible, governments had to quickly improvise under pressure.

A country should outline and establish appropriate and sufficient legislation (e.g., laws and regulations) to support the implementation of sustainable health policies. This legislation should empower the government in office during a health emergency to impose strict and compulsory measures and countermeasures to protect the population. It is also necessary to have legal frameworks in place that hold the government accountable—both for the measures and countermeasures planned and implemented and for those not taken—when it comes to safeguarding public health. If governments can act without rules or avoid responsibility, the public will lose trust.

An illustrative example of legislation as a critical factor comes from Spain, where existing legal provisions allow the government to declare a ‘state of alarm’ through the Royal Decree [

38], in response to a severe healthcare situation. Italy also centralized its healthcare resources during the crisis.

As Espinosa-González et al. [

27] observe:

“… decentralization has also been a core subject in the public health policy agenda……with national governments regaining control to coordinate and execute the response in some devolved nations such as Spain and Italy…”

These examples show how legal authority can shift quickly in a crisis to enable stronger coordination.

A second example of this legal dimension as a success factor comes from Parmet and Sinha [

28], p. e28(3), who comment:

“Despite the breadth and allure of travel bans and mandatory quarantine, an effective response……requires newer, more creative legal tools… …the time has come to imagine and implement public health laws that emphasize support rather than restriction…”

This quote suggests that legal frameworks should not only be about control—they should also enable and support people through a crisis.

3.7. Goal Fulfillment Versus Non-Fulfillment

Effective responses were driven by clearly defined and achievable goals related to health, equity, and the continuity of services. In contrast, failures in goal setting or monitoring resulted in fragmented and inconsistent responses. Without clear goals, efforts ended up scattered and less impactful.

Sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures to protect populations should be assessed against the established goals of a health emergency strategy to evaluate planning, implementation, and control. The degree to which strategic goals are fulfilled—or not—provides a benchmark for assessing the effectiveness of the measures and countermeasures undertaken. Established goals should serve as more than window-dressing or lip service; they must clearly define the reasonable and adequate direction for the required sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures. Goals that are vague or symbolic do not really help when real decisions need to be made quickly.

An example of goal fulfillment as a relevant factor comes from Loayza [

29], p. 1, who explains:

“The Brief concludes that the goal of saving lives and livelihoods is possible with economic and public health policies tailored to the reality of developing countries.”

This shows that even in resource-constrained settings, clear and realistic goals can guide effective responses.

Another example of goal fulfillment as a guiding concept comes from Ritchie, Cervone, and Sharpe [

30], citing Little [

31], p. 80, who note:

“…goals are not just mental contents stored in the head. Personal strivings are fundamentally intertwined with the social contexts in which one lives. People often can sustain their pursuit of a personal goal in ‘the felicitous case’ in which they work toward ‘projects that are meaningful, manageable, and supported by the eco-setting.’”

This reminds us that goals do not exist in a vacuum—they need to be rooted in the real world and supported by structures and people.

3.8. Digital Health Technology Versus Traditional Tools

Countries that utilized digital platforms—for surveillance, risk communication, and resource tracking—were able to improve response speed and transparency. In contrast, traditional or paper-based systems limited a country’s capacity for real-time decision-making. It is hard to move fast in a crisis when one has only slow or outdated tools.

Technology appears to be a key success factor in the implementation of sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures. Specifically, digital health technologies have been utilized and have played a vital role in the health policies of several countries. In some cases, apps and platforms allowed things to happen faster and more smoothly.

An example of digital health technology as a relevant success factor comes from South Korea. Whitelaw, Mamas, Topol, and Van Spall [

32] contend that:

“Digital health technology can facilitate… …strategy and response in ways that are difficult to achieve manually. Countries such as South Korea have integrated digital technology into government-coordinated containment and mitigation processes—including surveillance, testing, contact tracing, and strict quarantine—which could be associated with the early flattening of their incidence curves.”

South Korea’s use of tech shows what is possible when digital tools are embedded in a coordinated national strategy.

Another illustrative example of digital health technology as a success factor comes from China. Han et al. [

33], p. 3 report that:

“…Weibo is one of the most popular social media platforms in China… …Weibo messages… …were collected with ‘pneumonia’ and ‘coronavirus’ as the keyword… …findings indicate that timely release of information from the government was helpful in stabilizing public opinion in the early stage…”

This example shows that digital communication platforms can play a significant role in shaping public perception and trust during a crisis.

3.9. Empirical Versus Non-Empirical Support

Evidence-based policymaking, grounded in scientific data and expert advice, contributed to more effective interventions. In contrast, politically motivated or unverified decisions undermined public trust and weakened outcomes. When science was ignored, the consequences often came quickly.

Sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures undertaken to protect populations should be grounded in knowledge and an understanding of the health emergency context. A scientific foundation can offer valuable direction. However, the absence of empirical support should not automatically disqualify a given measure or countermeasure. Non-empirical support does not necessarily indicate that an intervention is irrelevant or ineffective; it may simply reflect a lack of sufficient data. In such cases, it may be appropriate to implement measures based on precautionary reasoning while working to generate empirical evidence. Sometimes, it comes down to common sense and not waiting until all the data are available to act on an obvious threat.

An example of evidence-based policymaking as a relevant factor comes from Bhattacharyya, Das, Ghosh, Singh, Mukherjee, Majumder, Basu, and Biswas [

34], who highlight:

“One cardinal feature……is our ability to monitor the spread and evolution……almost in real time……being deposited every day in large numbers from all global regions to public databases.”

This example shows how access to shared, up-to-date data helped scientists and policymakers to remain in control of the crisis.

3.10. Ethical and Moral Virtue Versus Decay

This final factor reflects the ethical dimension of leadership and institutional behavior. Solidarity, transparency, and moral responsibility strengthened societal resilience, while corruption, discrimination, or disinformation undermined legitimacy and social cohesion. When leaders acted unfairly or dishonestly, people quickly lost trust—and that trust was hard to win back.

Sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures that are not undertaken to protect populations may result from prioritizing economic considerations over a balanced approach that includes health, social, and economic dimensions. Ethical and moral imperatives to safeguard public health and social well-being may be marginalized in favor of economic values. Evidently, a tension often exists between doing the right thing—ethically and morally justified on health and social grounds—and doing things right for business, guided by economic criteria. The key is that each major sustainable health policy measure and countermeasure should be clearly explained to the population. If decisions are made based mainly on money, people should be told the truth, not given vague excuses. When the economic costs of fully protecting the population from health and social impacts are deemed too high, this should be stated explicitly. Yet in many cases, such transparency is avoided, and other less convincing justifications are communicated—often rooted in purely economic reasoning.

An example of ethical and moral virtue as a relevant factor comes from Gostin et al. [

35], p. 3229, who write:

“National and international responses… …have profound implications for 3 important ethical values: privacy, liberty, and the duty to protect the public’s health…”

This highlights that public health decisions are not only technical—they carry deep ethical consequences that affect people’s rights and trust.

4. Discussion

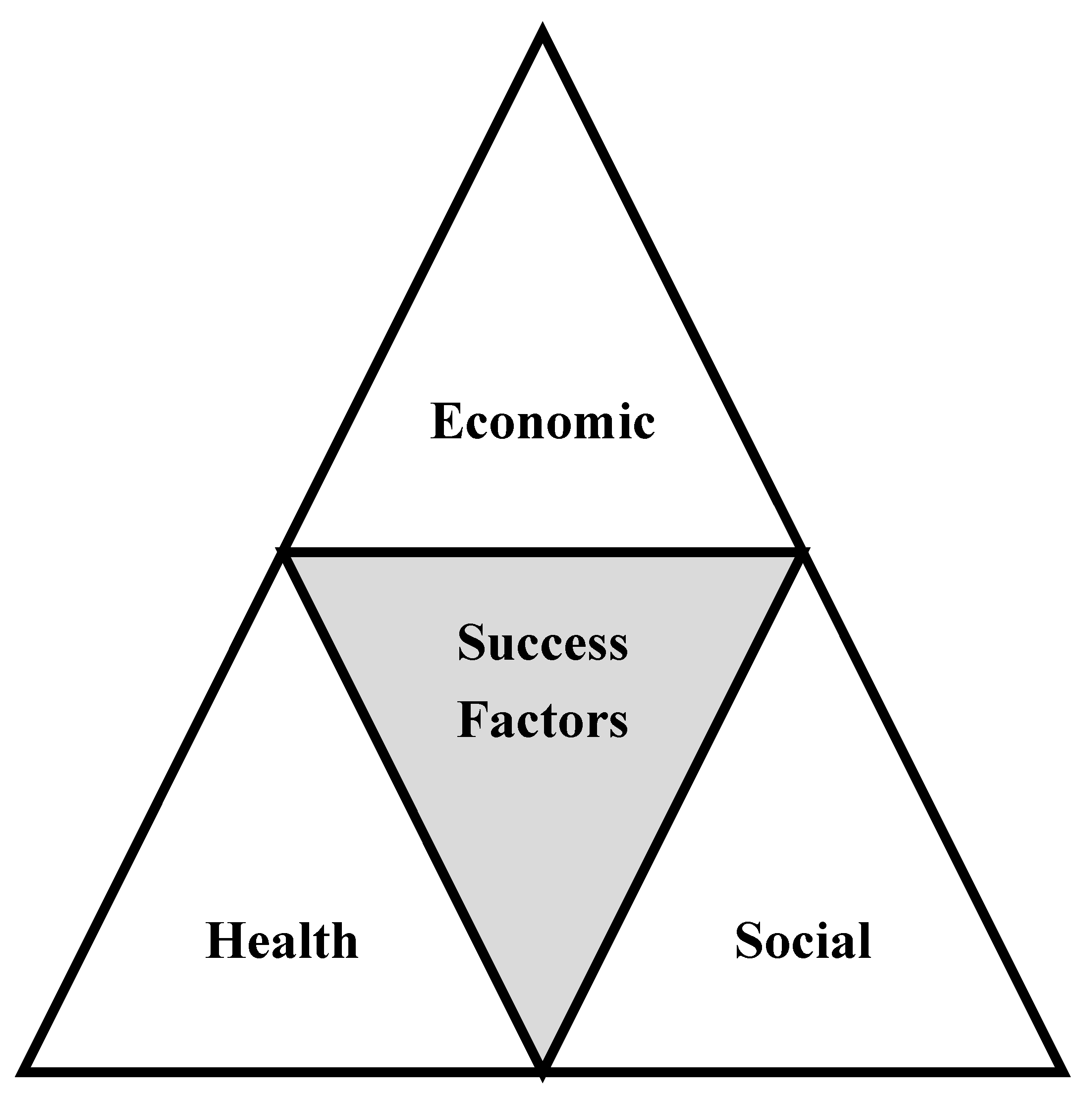

Consequently, the health emergency revealed a series of key factors that may characterize successful sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures across countries. The factors displayed in

Figure 2 represent a health emergency toolkit of assessment, outlining sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures undertaken either pre hoc or ad hoc in the implementation and management of strategies to protect populations. These factors do not guarantee success, but they offer a strong starting point for countries attempting to be better prepared in the future.

Table 2 displays three assessment outcomes per factor: health, social, and economic criteria. Each criterion can be evaluated by indicating ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘NA’ (not applicable), reflecting the extent to which the planning, implementation, and management of sustainable health policies (e.g., within a country and its population) has addressed the health, social, and economic dimensions of a given factor. This simple Yes/No/NA approach makes it easier to identify gaps and strengths in how policies were handled.

For example, sustainable health policies may meet the expectations of the economic criterion for a given factor satisfactorily, while the health and social criteria may be met unsatisfactorily—and vice versa. It is likely that the planning, implementation, and management of sustainable health policies will not yield positive assessments across all factors and criteria. In a worst-case scenario, the outcome may be negative across all dimensions. By contrast, the best-case scenario would involve addressing all factors satisfactorily—or at least as many as possible—across health, social, and economic criteria. But expecting everything to be perfect in practice is unrealistic. Achieving full success across all factors appears to be a utopian scenario.

The health emergency toolkit of assessment distinguishes between factors and criteria, offering a foundation for capturing a broader evaluation of the planning, implementation, and management of sustainable health policies. It is designed to provide structure without being overly rigid or prescriptive.

Evidently, the health emergency toolkit of assessment displayed in

Table 2 is not an exhaustive or complete list of all possible factors related to sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures; additional factors are likely to be identified and added over time. It serves as a foundational basis for assessing the sustainable health policy measures and countermeasures undertaken across different time periods and contextual settings. It is a starting point, not a final definitive checklist.

The health emergency toolkit of assessment displayed in

Table 2 enables the framing of the degree of success—specifically, whether the impact of sustainable health policies has been effectively handled or not—in terms of implementation and management across factors within a country, with the goal of protecting its population. Consequently, the toolkit facilitates the assessment of key sustainable health policy factors across health, social, and economic criteria. It can also be applied at multiple levels, including national, regional, and city contexts. This flexibility makes the toolkit useful, as it allows evaluation on a scale from a whole country to a single municipality.

Figure 2 illustrates the success factors that may influence health, social, and economic outcomes in the implementation of sustainable health policies.

The health impact criterion in

Figure 2 refers to the contribution of effective policies to disease control, health system resilience, and improved population health outcomes, including morbidity (e.g., hospitalizations and ICU admissions) and mortality rates (i.e., direct and indirect deaths). It is concerned with whether policies keep people healthier and alive.

The social impact criterion refers to the influence of inclusive, transparent, and equitable policies in fostering public trust, social cohesion, and behavioral adherence, as well as the consequences of measures and countermeasures for the population (e.g., restrictions on daily life, movements, and behaviors). In simple terms, it is about how people were treated and how they responded in return.

The economic impact criterion refers to the role of well-calibrated public health interventions in minimizing economic disruptions and supporting long-term workforce stability. It also includes the impact of measures and countermeasures on employment, education, business activity, and other economic aspects affecting the population. A broader fourth consideration is the effect on national GDP growth resulting from the implemented measures and countermeasures. It is concerned with whether the economy stayed afloat while public health policies were enforced.

In this way, the figure serves as a conceptual bridge between the ten success factors presented previously (

Figure 1) and their broader implications for sustainable health system governance. By integrating this visual framework into the manuscript’s thematic analysis, the text enhances the reader’s understanding of the practical relevance and systemic interdependencies of each factor. It helps tie everything together, so the connections are not lost in the details.

5. Conclusions

We conclude that the outcome of a sustainable health policy depends on multiple factors, each forming the basis of a health emergency toolkit of assessment to evaluate whether a factor has been properly planned, implemented, and managed. The strategic outcome is shaped by the assessment across health, social, and economic criteria. No single factor can explain success on its own—it is the combination that really matters.

The health emergency assessment toolkit developed in our study provides a conceptual foundation for identifying key success factors in the design and implementation of sustainable health policies. By integrating health, social, and economic criteria, the toolkit enables a multidimensional analysis of policy effectiveness, helping to contextualize national responses and their broader implications. It allows us to see how different parts of a response fit together—or do not—in real-world settings.

While the toolkit outlines a set of enabling factors grounded in comparative case analysis, it also presents several opportunities for future development and empirical refinement. One important avenue for improvement involves applying the toolkit within specific national or subnational contexts—such as countries, regions, or cities—to test the validity and reliability of the identified factors. This contextual application would also make it possible to incorporate additional success factors that may emerge from local experiences, institutional structures, or cultural dynamics. There is a lot to be learned by seeing how the toolkit performs on the ground in different places.

Moreover, the toolkit can be used to classify and benchmark best and worst practices in the planning, implementation, and management of sustainable health policies. Such empirical applications could contribute to the development of comparative datasets, support cross-country learning, and offer practical guidance for policymakers aiming to strengthen health system resilience. It could help decision-makers see what worked—and what did not—based on real-world outcomes.

The authors acknowledge the absence of systematic coding and weighting mechanisms as a limitation of our exploratory study. However, this version is intended to serve as a foundational step toward developing a more comprehensive analytical framework. As outlined above, future research should adopt a mixed-methods approach, incorporating structured qualitative coding (e.g., axial or selective coding), content analysis, and expert validation techniques—such as Delphi panels or stakeholder surveys—to improve the empirical robustness, policy relevance, and generalizability of the proposed framework. While the toolkit is not yet perfect, it lays the groundwork for more structured research to come.

By expanding its empirical reach and analytical precision, the health emergency assessment toolkit holds significant potential to inform more sustainable, equitable, and evidence-based health governance at both national and global levels. It could make a significant difference if taken seriously by those in authority.