1. Introduction

In the face of growing uncertainty, cascading disruptions, and the intensification of chronic risks, cities are increasingly called upon to enhance their resilience. This need for enhanced resilience emerges in parallel with a profound shift in spatial planning paradigms. The recognition of the complexity of urban systems and the impossibility of exact prediction has prompted a move away from methods based on standards and performance measures aimed at predetermined outcomes [

1]. Instead, recent decades have seen a growing emphasis on process-oriented planning and the development of flexible tools designed to navigate dynamic, uncertain conditions [

2]. This evolution reflects a broader awareness of the limitations of linear planning models and the necessity for adaptive approaches that can accommodate the evolving and multifaceted challenges facing contemporary cities.

Yet, the meaning and operationalization of urban resilience remain elusive. This paper argues that many existing approaches fail to adequately address the complex, dynamic, and often contradictory nature of urban systems. Resilience is frequently interpreted as a static capacity or a one-size-fits-all goal, achieved through predefined phases and standardized procedures. This tendency is particularly evident in administrative contexts, where resilience is often reduced to a compliance exercise, relying on performance indicators that are met formally but do not trigger any real transformation of urban systems.

Such an interpretation not only overlooks the diversity and fluidity of urban contexts but also risks promoting shallow adaptation instead of enabling genuine change. Despite the growing literature on resilience in urban systems, a key issue persists: how can resilience be framed as a process of transformation, rather than a return to normality? This paper proposes a shift from reductionist views toward an evolutionary understanding of resilience as an ongoing, systemic, and anticipatory capability. Rather than seeking to restore an idealized past state, this approach emphasizes the importance of creativity, learning, and collaboration in navigating disequilibrium and co-producing more just and sustainable urban futures.

This understanding implies not only a change in methodology but a profound epistemological shift. From a scientific standpoint, resilience cannot be treated as a fixed property of a system but must instead be understood as a generative, process-based capability that emerges through uncertainty, conflict, and adaptation. It requires abandoning the idea of returning to an original state of balance and instead embracing instability, contradiction, and ambiguity as preconditions for systemic learning and innovation. In this view, resilience aligns more closely with processual epistemologies, where knowledge and transformation co-emerge from lived experiences, experimentation, and the continuous renegotiation of meaning across social, ecological, and technical domains.

While these challenges are increasingly evident in the conceptual discourse, they also manifest in the tangible dynamics of contemporary urbanization. In today’s interconnected world, cities operate as pivotal nodes in global networks, concentrating flows of people, capital, knowledge, goods, and data. They host advanced services, infrastructures, and populations that contribute decisively to the functioning of the global economy. This systemic centrality makes them attractive, but also deeply vulnerable. Urbanization, driven by asymmetries in resource distribution and investment, continues to expand, often in fragmented and uncoordinated ways. The resulting urban forms are frequently characterized by density, inequality, and infrastructural inadequacy, which exacerbate exposure to diverse risks.

As urban systems expand and densify, they become increasingly susceptible to a range of shocks and stresses: climate change-induced disasters, earthquakes, industrial hazards, terrorism, and social unrest. Poor planning practices, such as unchecked soil sealing, intensify these vulnerabilities by contributing to urban heat island effects and flash floods [

3]. These phenomena can abruptly interrupt critical urban functions, reversing developmental gains and deepening existing socio-economic divides.

Municipal authorities must therefore find ways to reduce systemic exposure while managing the inertia of the built environment, which evolves far more slowly than social expectations. Enhancing resilience requires not only technical preparedness but also an ability to integrate cultural, historical, and symbolic resources into adaptive strategies. As Esposito et al. argue, urban identity and memory are not obstacles to adaptation but rather essential assets for building locally rooted, community-centered resilience pathways [

4].

Still, the prevailing orientation in much of the scientific and policy literature remains centered on engineering logic and predefined targets. Many initiatives aim to quantify resilience through normative indicators and compliance metrics, seeking formal conformity rather than substantive change. Vale points out that even within engineering-oriented interpretations, post-disaster performance measures may not capture the political or social impacts of crises, nor indicate whether a city has truly become more resilient [

5]. Likewise, UN Sustainable Development Goal 11 emphasizes resilience as a measurable target, often linked to exposure reduction or structural robustness, potentially overlooking cultural, historical, and relational factors.

In response to these limitations, recent work has called for more dynamic and inclusive framings. Linkov distinguish between engineering, ecological, and adaptive resilience, suggesting that urban systems require the latter form to navigate complex and evolving challenges [

6]. Geels emphasizes the co-evolutionary nature of socio-technical change, arguing for frameworks that can accommodate nonlinear transformations [

7]. Concepts like the adjacent possible further reinforce the idea that innovation and resilience emerge through incremental exploration, experimentation, and shifts in collective meaning [

8]. Building on these perspectives, this paper proposes a process-based framework, the Ladder of Urban Resilience, that articulates resilience as a cumulative and process-based progression across three interconnected scenarios: baseline, critical, and chronic crisis. It conceptualizes resilience as a continuum of capacities co-produced through diverse forms of participation, learning, and structural adaptation, integrating insights from complex systems theory, socio-ecological resilience, and urban governance to offer a multidimensional model of transformative capacity-building.

Methodologically speaking, the conceptual framework developed in this paper was constructed through an abductive and iterative reasoning process, grounded in a critical synthesis of resilience literature, transdisciplinary insights, and evidence derived from the Taranto case study. Rather than starting from predefined hypotheses, the framework emerged by moving back and forth between empirical observations and theoretical constructs, aligning with abductive logics of inquiry [

9,

10]. The literature review included both foundational works on socio-ecological resilience [

11,

12], and more recent contributions focused on systemic change, chronic crises, and governance under uncertainty [

13,

14]. In line with emerging critical systems approaches to sustainability science [

15] the proposed framework is intended not only as an analytical tool but also as a reflexive instrument for enabling transformative agency in complex urban systems.

This theoretical grounding was complemented by insights generated through participatory activities, policy experimentation, and scenario analysis conducted in the city of Taranto, used as a heuristic device to explore and refine the analytical categories. The resulting framework does not aim to provide universal prescriptions, but rather a flexible, problem-oriented matrix for diagnosing urban resilience conditions and enabling context-sensitive governance strategies. This conceptual construct is situated within the tradition of theory-building for complex systems, in which frameworks are derived from the interplay between real-world complexity and theoretical abstraction [

16,

17].

Operationally, this contribution is developed within the context of the ReCITY research project, which aims to support community-oriented resilience through the development of a complex Social-Ecological-Technological Systems (SETS) [

18,

19]. In this context, resilience is not solely viewed as a preparedness or recovery capability, such as the capacity to absorb impacts or to efficiently return to a previous state, but as a dynamic, transformative process. The emphasis is placed on the ability to learn from disruptions, to foster creativity, and to support structural innovation. One of the central objectives of the project is to strengthen the intangible backbone of communities by leveraging ICT platforms that facilitate horizontal cooperation among citizens and vertical integration between governance and society. These digital infrastructures enable local actors to operate as interconnected systems, capable of adapting, anticipating, and co-evolving in the face of critical and acute crises.

The proposed framework is illustrated through the case of Taranto, a medium-sized port city in Southern Italy characterized by decades of environmental degradation, social fragmentation, and political instability. Rather than representing a classic disaster scenario, Taranto exemplifies a condition of persistent, unresolved structural crisis—a chronic emergency with transversal and multi-scalar implications. In this context, resilience must be understood not as recovery from a singular shock but as the capacity to navigate prolonged disorder, support bottom-up innovation, and activate latent community potential.

Drawing on the Taranto case, this paper critically assesses existing approaches to urban resilience and introduces an evolutionary framework that reorganizes the multiple dimensions typically invoked in resilience thinking. It does so by articulating a process-based model, the Ladder of Urban Resilience, structured across three governance scenarios and four levels of systemic capability. This framework enables the mapping of diverse problems, actors, and interventions within a unified matrix, offering guidance for decision-making under uncertainty and supporting pathways of transformative governance. The article is organized as follows:

- -

Section 2 explores the conceptual foundations of resilience in relation to urban systems, tracing its evolution from engineering-based interpretations to socio-ecological and process-oriented perspectives. It critically reviews academic and institutional framings, highlighting unresolved tensions and epistemological shifts.

- -

Section 3 introduces the Urban Resilience Matrix, a multidimensional tool designed to interpret resilience as a dynamic, context-sensitive process. The section articulates three levels of systemic complexity—adaptive, critical, and chronic—and maps them across different resilience scenarios.

- -

Section 4 presents the Ladder of Urban Resilience, a process-based framework that integrates participatory governance, learning capabilities, and co-generative innovation. It also outlines operational pathways and enabling conditions to move across resilience levels, emphasizing the role of digital infrastructures and community empowerment.

- -

Section 5 reflects critically on the framework’s application, discussing its limitations, potential barriers, and the conditions required for its effective implementation. Particular attention is given to the measurability of transformative change and the risks of simplification.

- -

Section 6 concludes by summarizing the main contributions and proposing future research directions. It stresses the importance of systemic creativity, early adopters, and reflexivity as foundational capacities for building transformative urban resilience.

By following this structure, the paper aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of urban resilience, considering valuable insights from the case study and offering a blueprint for how resilience can be effectively fostered by communities in different situations, from the steady state to the case where chronic crises are in place.

2. Background

2.1. Rethinking Resilience: A Process-Based Approach to Urban Systems

The concept of resilience has evolved considerably across disciplines, often leading to overlapping yet inconsistent definitions. Rather than narrowing it to a single fixed meaning, this paper adopts a process-based and evolutionary view of resilience, aligned with the complex and dynamic nature of complex SETS.

Resilience is not understood here as a measurable condition or as the ability to return to a pre-disturbance state, but rather as a generative quality, an enabling condition that facilitates the emergence of new configurations in the face of disruption, uncertainty, or instability. In this view, resilience is not a goal or a property to be attained once and for all, but an evolving capability, a way of operating and becoming, based on reflection, imagination, and transformation. It acts as a systemic “enzyme” that accelerates, amplifies, and enables positive reorganization and innovation across time and space.

This definition builds upon socio-ecological literature [

11,

20], but extends it by emphasizing three foundational qualities that underpin transformative change: relationality, reflexivity, and learning ability. These are not static attributes but enabling capacities that must be exercised and cultivated. Resilience, in this sense, is not something systems “have” but something they “do” through navigating contradictions, managing bifurcations, and engaging in continuous reconfiguration.

Crucially, this perspective rejects the binary framing of resilience as the opposite of vulnerability or as a purely reactive response to discrete shocks. Instead, it aligns with the idea that emergencies, even chronic or slow-burning crises, are inherent features of system evolution, and that resilience should enable systems not merely to withstand such events but to evolve through them.

Following this rationale, the urban system is not viewed as a closed and self-correcting entity, but as an open, adaptive, and co-evolving ecosystem. Urban resilience, therefore, requires engaging with instability, leveraging failure as an opportunity for learning, and supporting the emergence of shared visions that can guide collective reorganization. The proposed framework contributes to this vision by offering a stepwise and cumulative ladder of scenarios, each characterized by increasing levels of agency, coherence, and systemic innovation.

2.2. Scientific Interpretations of Resilience and Conceptual Debates

Urban science has drawn extensively on the evolving concept of resilience, importing definitions and principles from diverse disciplines, including engineering, ecology, psychology, and social sciences. At the same time, it contributes to advancing this notion by exploring how resilience unfolds in complex SETS. As an interdisciplinary field, urban studies can bridge conceptual silos and provide a practical vocabulary for supporting resilience at the scale of communities, infrastructures, and institutions.

The literature proposes a long list of capacities that need to be developed to achieve resilience. These range from resistance to recovery, absorption to response, repair to adaptation, and learning to transformation [

5,

11,

12,

19,

20,

21]. These capacities, in turn, rely on a variety of system properties—such as anticipation, robustness, redundancy, resourcefulness, rapidity, stability, persistence, flexibility, identity, learning, fluidity, reflexivity, contingency, connectivity, multiplicity, inclusivity, polyvocality, and diversity—whose articulation, however, often remains fragmented and discipline-specific [

22]. In addition, concerns related to social justice, equity, legitimacy, and participatory democracy have emerged in the effort to determine whose resilience is being prioritized [

23]. This highlights the argument that a more equitable society requires broader citizen participation and diverse voices in public discourse on resilience [

24]. While economists may emphasize robustness and efficiency, ecologists focus on feedback loops and thresholds, and urban scholars foreground inclusion and legitimacy. As a result, the term “resilience” is often employed ambiguously and with different intentions [

25].

Hence, a broad spectrum of definitions has been proposed across scientific and institutional literature, a selection of which is presented in

Appendix A. Despite their diversity, these definitions frequently converge on recurring terms such as “capacity”, “ability”, “system”, “shock”, “adaptation”, and “recovery.” This shared vocabulary reflects a dominant interpretation of resilience as a set of operational capacities or functional attributes that systems must acquire to cope with disruptions. Often, this framing stems from an engineering logic, one that emphasizes stability, control, and recovery, and portrays resilience as a fixed quality to be embedded or transferred across contexts.

The analysis of definitions reveals that resilience is typically reduced to a quantifiable outcome, with emphasis placed on identifying pragmatic solutions, linear or circular response models, and measurable indicators. This has led much of the scientific community to shift its attention from the conditions required to achieve resilience to how much resilience is desirable or acceptable. Unfortunately, this paradigm has facilitated the emergence of administrative practices that pursue resilience goals primarily for compliance, rather than substantive transformation. Particularly at the local scale, cities often adopt formal indicators to fulfill top-down requirements, without advancing the real systemic upgrade of urban capacities.

Vale critically observes that even from an engineering perspective, physical indicators offer little insight into how cities respond politically, socially, or psychologically to crises [

5]. Post-disaster assessments that focus solely on buildings or infrastructure fail to demonstrate how effectively a city has “bounced back” or reveal the depth of its adaptive capacity. Nonetheless, considerable efforts have been dedicated to resilience metrics. This is evident in the normative targets of Sustainable Development Goal 11: “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable”, especially target 11.5 [

26]. These targets aim to quantify resilience improvements, notably through reduced exposure and vulnerability to climate-related and other hazards. Yet, such goals remain ambitious and difficult to measure with precision in real urban environments.

More recent interpretations emphasize that urban resilience should not be equated with the vulnerability of physical infrastructure alone. It has gradually emerged as a broader and partly autonomous concept—one that includes cultural, social, and institutional dimensions. Graveline et al. [

27] note that while vulnerability and resilience are interrelated, they are not simply inverse conditions. Real-world emergencies illustrate how resilience is highly contingent upon local cultural values, informal knowledge, and intangible resources. In open socio-ecological systems, resilience emerges through reflexivity and learning processes often triggered by exposure to crises. Rather than being a predefined asset, resilience is cultivated through experience and collective sense-making.

This perspective finds resonance in the work of Brown [

28], who highlights that resilience, particularly in human systems, stems from embracing vulnerability rather than denying it. The capacity to recover, adapt, and grow stronger arises not from rigid resistance but from the willingness to reflect, share, and learn through adversity. Similarly, Duke [

29], drawing from behavioral decision theory, debunks the myth that resilience is synonymous with perseverance at all costs. Clinging to failing strategies, she argues, can hinder the recognition of better alternatives. True resilience lies in knowing when to let go, turning failure into a resource for strategic repositioning and innovation.

The definitional mapping conducted in this paper was not intended to be exhaustive but to extract recurrent patterns and identify conceptual blind spots. Both peer-reviewed literature and institutional frameworks were considered—including UNDRR, IPCC, SMR, and the Sendai Framework—with attention to how definitions evolved from engineering resilience to more adaptive, socio-technical framings [

30,

31,

32,

33].

Ultimately, rather than adopting these dimensions as stable categories, the paper uses them as a springboard to question the sufficiency of current models. It argues that resilience must be understood as an emergent, situated, and contested process—one that cannot be reduced to a checklist of components or capabilities. This critique sets the stage for proposing an alternative operational framework, which aims to reorganize the multiple dimensions of resilience into a coherent process-based and generative model for guiding urban governance in turbulent times.

2.3. Operational Formalizations and Their Limitations

The increasing institutionalization of urban resilience has encouraged the development of frameworks, maturity models, and strategic guidelines aimed at integrating resilience into planning practices. In operational terms, urban resilience is often framed as the resilience of human-made territories, predominantly urbanized and infrastructured environments. This spatial contextualization, while necessary, raises epistemological concerns regarding the demarcation of boundaries within open, complex systems like cities. Initially, many institutional approaches employed a normative simplification by using administrative boundaries as proxies. Yet, the reality that threats and crises rarely respect municipal borders undermines this assumption and reveals its analytical insufficiency.

Temporally, urban resilience models have typically followed linear schematics borrowed from disaster risk reduction (DRR), such as the well-known sequence: prevent—prepare—respond—recover. Rooted in engineering logic, these cycles suggest that resilience can be organized chronologically, with specific interventions mapped to discrete phases. In particular, they distinguish between “preventive resilience,” aimed at mitigating known risks before they occur, and “reactive resilience,” focused on absorbing and recovering from impacts once a disruption has occurred.

Such formalizations continue to dominate resilience planning—evident in the Disaster Risk Management Cycle (DRMC) and its adaptations in ISO 37101, the Smart Mature Resilience (SMR) Project, and the Sendai Framework [

32,

33,

34,

35]. These models provide useful guidance for mainstreaming resilience, emphasizing the importance of feedback loops, institutional coordination, and performance-based indicators. In particular, the Sendai Framework marks a conceptual shift from “bouncing back” to “building back better,” recognizing that pre-disaster conditions often represent a key source of systemic vulnerability. Likewise, recent standards such as CEN CWA 17727 incorporate process-based reviews to improve preparedness and adapt interventions over time [

36].

However, these institutionalized approaches face two critical limitations. First, they risk reifying resilience as a normative goal to be achieved through technical procedures, assuming that the necessary capacities already exist, are transferable, or can be engineered into place. Second, they rely on simplified models of linear causality and sequential action, which do not adequately reflect the entangled, recursive, and contested nature of urban change. This is particularly problematic in chronic crisis conditions, where pre-existing norms, infrastructures, and institutions may themselves be part of the problem, and where resilience requires deeper transformation rather than stabilization.

In this context, the resilience-as-function paradigm has gained traction: cities are increasingly treated as systems whose performance must be optimized across multiple dimensions. This has generated a proliferation of indices and metrics, often inspired by the Deming cycle (Plan-Do-Check-Act), aimed at monitoring the ability of cities to recover from shocks and sustain essential services [

37]. Yet, as Adolphe notes, this approach underplays the socio-ecological complexity of urban environments and reduces resilience to a management task, often excluding social learning, power dynamics, and political conflict from the equation [

38].

Moreover, the functionalist perspective tends to ignore the heterogeneity of urban actors and the plurality of urban functions. For instance, Davoudi notes how even in progressive plans like London’s Climate Change Adaptation Strategy, the interpretation of resilience remains narrowly technical, excluding cultural, psychological, and relational dimensions [

39]. Similar critiques are raised by Wilkinson, who identifies a gap between academic debates on socio-ecological resilience and its superficial uptake in urban policy, where participatory governance is often reduced to tokenism or consultation [

40].

Despite the growing interest in long-term resilience, most frameworks are still built around bounded spatial and temporal assumptions, assuming that disruptions can be neatly localized and that systemic feedbacks can be anticipated. However, as cascading risks, interdependencies, and transboundary crises become more common, these assumptions become increasingly untenable.

Finally, while the Stockholm Resilience Centre [

41] has offered more nuanced principles for building resilience, including modularity, connectivity, feedback sensitivity, and polycentric governance, their translation into practice remains fragmented. Similarly, the notion of the adjacent possible shows how innovation and transformation emerge from exploring the latent potential of existing configurations [

8]. Yet these insights are seldom incorporated into urban resilience strategies that prioritize stability over experimentation.

Overall, urban resilience remains too often viewed through the lens of optimization, rather than evolution. Its operationalization still depends heavily on predefined goals and technocratic delivery mechanisms, which are ill-suited to complex, adaptive challenges. There is thus a pressing need to rethink resilience not as a condition to be attained, but as a process to be continually co-produced—one that emphasizes reflexivity, negotiation, and situated agency. This need forms the conceptual basis for the integrative framework proposed in the following section.

2.4. Toward a Process-Based and Transformative Understanding of Urban Resilience

This paper challenges the dominant interpretation of resilience as a predefined set of capacities or a normative outcome to be achieved. By reviewing the most widely cited definitions across disciplinary and institutional sources (see

Appendix A), it becomes evident that resilience is frequently conceptualized as a transferable and teachable capacity, something that can be prescribed by experts and absorbed by local communities. While this view facilitates the development of technical tools and indicators, it risks reducing resilience to a process of external implementation, overlooking the internal, situated, and culturally embedded nature of transformation.

In contrast, the framework proposed in this work emphasizes the generative and systemic dimension of resilience as a relational quality that evolves through context-specific experiences. Rather than treating resilience as an external intervention, the ladder model conceives of it as a developmental pathway that unfolds through successive stages of awareness, experimentation, and collaboration. Each stage of the ladder reflects not only a shift in capabilities but also a deeper capacity for sense-making, collective agency, and situated innovation. In this view, resilience emerges through the city’s ability to reconfigure its internal logics of action and governance, not to restore stability, but to navigate complexity and reorient toward more sustainable futures.

This confirms the need for a more integrative and dynamic approach—one that redefines urban resilience not merely as a set of desirable features, but as an ongoing co-evolutionary process rooted in governance, experimentation, and learning, as elaborated in the following sections. In particular, the analysis of current frameworks reveals persistent limitations in addressing three critical aspects of operational resilience:

Selecting appropriate capabilities based on the typology and structure of the problems being faced, avoiding one-size-fits-all strategies;

Determining the processes to develop across the multiple domains of the complex SETS that constitute an urban ecosystem;

Clarifying how diverse agents participate in decision-making and implementation, recognizing the multiplicity of roles, relationships, and forms of legitimacy.

These interrelated challenges are central to the investigation carried out in this article. The following chapter introduces an integrated framework, the Ladder of Urban Resilience, that responds to these questions by articulating a process-based and anticipatory understanding of resilience. The framework is intended to function as a decision support system for urban governance, capable of guiding cities in navigating uncertainty, managing transitions, and fostering long-term transformation.

3. Method

The observed vagueness of the urban resilience meaning, and consequent limitations and unsatisfactory applications, reflect a lack of holistic understanding due to a reading of the city that focuses solely on spatial, administrative, economic, and morphological aspects, while neglecting other crucial elements such as culture, environment, society, and information. This reductionist view contributes to the narrow systemic thinking, which limits the ability to envision adjacent possibilities and weakens systemic adaptability [

42].

Viewing the city purely as a composition of artifacts made from self-referential artificial products and related silos of knowledge only allows for deploying fixed operational routines, at best able to link a certain type of resilience to a certain type of disaster, mirrored and arranged on a linear spectrum [

43]. This matches the typical managerial logic of ‘efficiency-oriented’ planning that is inadequate for long-term resilience building. Moreover, reading the city in parts leads to an increase in the accumulation of challenging problems arising where subsystems interface and intersect. Even if we were to hypothetically perfect the structure and functioning of the urban machine, resulting in a highly optimized city, it would remain stagnant, repeating the same patterns, and devoid of innovation [

12,

44].

Therefore, while an urban organism is physically instantiated in a specific place and defined by its built components, addressing resilience requires consideration of interconnections between many other spheres and their dynamic dimensions, which compose the urban system environment. This aligns with the socio-technical systems perspective proposed by Geels, where transformation stems not from individual subsystems but from dynamic interactions across regimes [

7].

Conversely, since a city is more than just the sum of its buildings, the challenges related to urban system resilience extend beyond technical responses and touch upon broader societal issues. Through studies on the social ecology of cities and their relationship with sustainability, there is a growing recognition of cities as living ecosystems that constantly strive to balance social, economic, and environmental concerns in a landscape where multiple states of equilibrium exist [

45]. This implies the acknowledgment that to live and evolve, the urban system operates in non-equilibrium dynamics and thus must be open to risk, ambiguity, and serendipity.

Indeed, as De Coning suggests, resilience must be reframed not as restoring order but as enabling transformative self-organization [

13]. The only constant in nature is change, and the balance to be sought can only be dynamic and evolutionary. This awareness presents a paradox to the mainstream conception of resilience as an equilibrium to be constantly regained. Rather than attempting to resolve this paradox, for communities it is more fruitful to embrace and learn to navigate disequilibrium—or in some cases, work to deliberately generate it [

46]. This perspective calls for a conscious interpretative extension so that the city, from the main source of problems, is also the principal proactive arena of solutions. This reconstitutes the eco-systemic circularity of its functional process as a fundamental entity of the generative evolutionary path of humankind on Earth.

3.1. Urban Systems Domains Structure

Resilience thinking recognizes the urban system as a complex SETS consisting of interdependent ecological, social, and technical components and informs resilience-building processes at the city scale [

20]. To operationalize this broad understanding, the Resilience Alliance originally proposed a simplified breakdown of the urban system into four major subsystems: (i) governance networks, (ii) metabolic flows, (iii) built environment, and (iv) social dynamics [

47]. Meerow et al. further elaborated these into: (i) governance networks, (ii) networked material and energy flows, (iii) urban infrastructure and form, and (iv) socio-economic dynamics [

48].

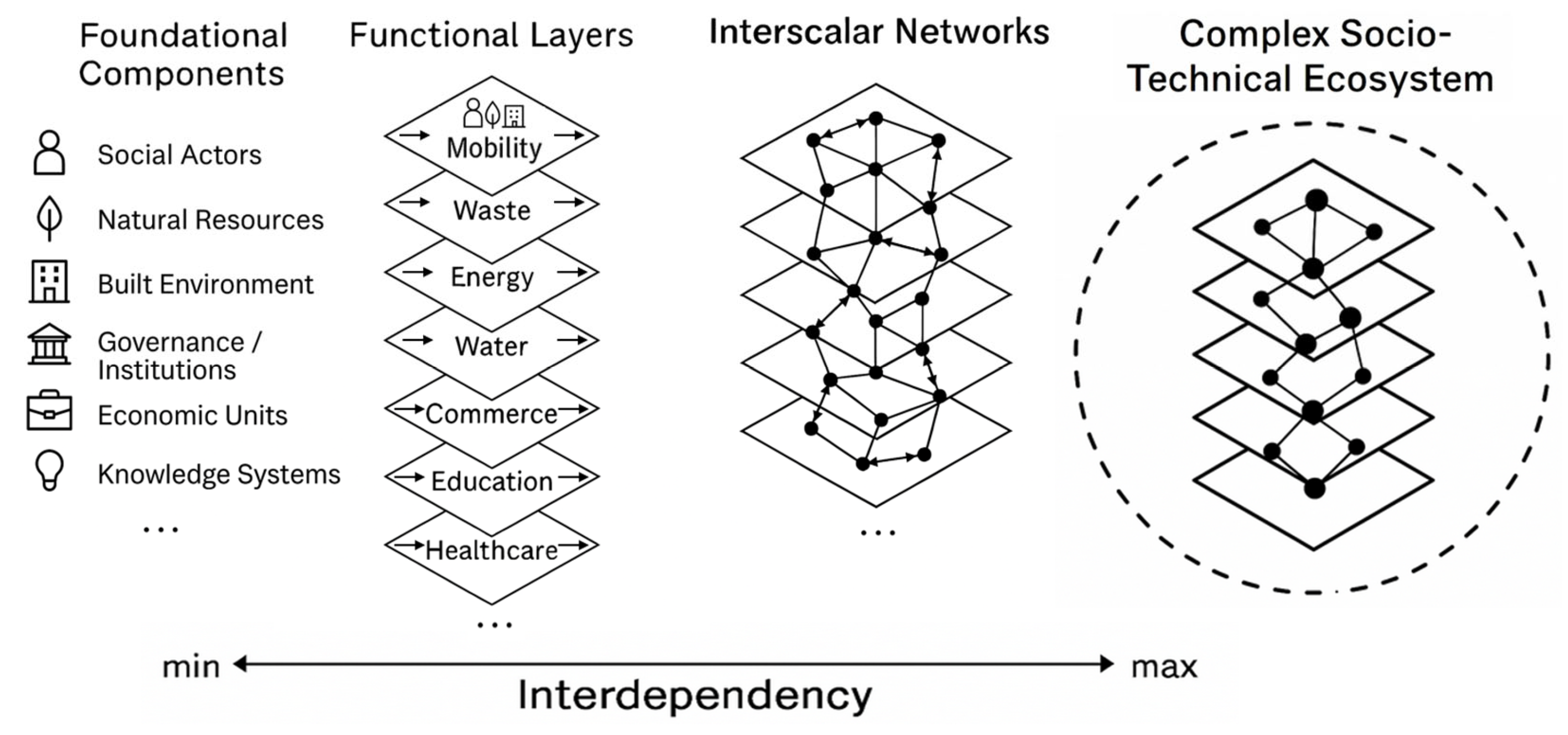

This scheme allows us to conceptually break down urban resilience as a process that involves different system domains at different times and through peculiar characteristics and interrelations. The description of the domains of the city system, following a hierarchical aggregation as each level requires the previous ones [

49], is presented as follows:

Infrastructures: This domain encompasses the physical structures, material resources, cognitive agents, and all other constituent elements of the urban system. These elements are described based on their specific properties and characteristics. The infrastructure serves as the set of preconditions that must be fulfilled for the system to exist. The domain involves the process of identification, categorization, and grouping into sets.

Flows: The domain consists of parallel and overlapping horizontal functional levels, each traversed by linear input-output flows. The domain is represented through the additive overlay of layers and represents the flow of resources within the urban system, such as energy, economy, water, and waste. These flows enable the mechanical-like functioning of the system. The flows serve as possibilities, allowing multiple mechanisms within the system to operate.

Networks: The domain is generated through the dynamic formation of connections across different scales and levels of interdependence. It comprises the data networks that provide information for decision-making processes, including governance dynamics and formalized knowledge creation. It includes three-dimensional networks that traverse the system and establish external connections through predefined ad hoc paths. These networks play a crucial role in activating and focusing the system’s energies and in its reconfiguration.

Community: This domain encompasses the tangible and intangible qualities that bind the community together, such as the cognitive abilities of individuals and groups, distributed intelligence, social connections, cohesion, and learning. It also includes creativity that supports survival and innovation, and bottom-up phenomena like serendipity and exaptation [

50,

51]. This reinforces the idea that communities are not passive recipients of resilience strategies but dynamic drivers of urban transformation.

Figure 1 offers a schematic representation of the progressive integration of urban system domains. It unfolds across four conceptual steps: (i) identification and categorization of the basic elements operating within the system; (ii) the construction of horizontal functional layers (e.g., mobility, commerce, education, etc.) operating independently through internal flows as overlaying layers; (iii) the recognition of inter-scalar and cross-functions networks connecting layers and enabling coordination; and (iv) the emergence of a coherent, unified, dynamic, and adaptive system, a unique complex SETS. This final configuration enables the emergence of higher-order social qualities such as collective intelligence, creativity, innovation, and solidarity.

Thus, such a complex SETS takes two forms at the same time: either as a set of individual independent particles aggregated differently depending on the level of the analysis, or a single system dynamically moving as a coherent wave along an evolutionary path. This dual and circular behavior serves as the potentiality for the system, offering prospects for overcoming crises and fulfilling desires for change. As Max Planck famously wrote: “If from the outside the world appears to be bound by a causal relationship, from an internal, subjective point of view, the will appears free” [

52].

3.2. Urban Systemic Resilience Evolution

On a temporal scale, the very nature of the urban system as a complex living system operating in a state of non-equilibrium along a single oriented temporal direction proves that a return to the pre-disturbance state is practically impossible. Indeed, resilience is understood as a combination of persistence, transition, and transformation [

53]. It encompasses the complementary capacities of bouncing back, building back better, and bouncing forward [

27]. Indeed, the view of resilience expecting a system to bounce back to the previous state is problematic because normality is neither adequate nor desirable since that state is prone to further breakdown and represents what initially gives rise to the causes of disruptions and their consequences [

54].

When an urban system undergoes a disturbance or upheaval, it transforms into something different, which should not be seen as a failure in terms of resilience but as an inherent possibility caught to transforms the system [

55]. This view resonates with the shift from engineering-based models to more socio-ecological approaches in which disturbances are not anomalies but integral to the system’s evolution [

12,

56].

Thus, resilience is not an achievable target, but a quality of change that fosters the evolution of the system, and that can never be definitively achieved, but should be constantly searched for. The implications of this understanding extend to planning and governance, so that resilience must be considered a dynamic capability, embedded in governance systems and evolving in time alongside the risks themselves [

14]. The concept of adaptive capacity becomes crucial here, not just the ability to adjust, but to shift governance, institutional logics, and priorities over time [

13,

20].

This understanding clarifies why it is not possible to identify an optimization point for the various dimensions through which resilience operates. It is not feasible to determine specific measures and percentages for properties such as redundancy, flexibility, connectivity, and resistance, or any combination thereof, to define once and for all a resilient urban system. The development of such a resilience perspective is qualitatively different from the search for optimal efficiency and heavily depends on the ability to change, which is shaped by contextual conditions. This echoes the argument by Linkov et al., who propose a shift from optimizing performance under known risks to building resilience for uncertainty, showing how resilience focuses on system reorganization more than resistance [

57].

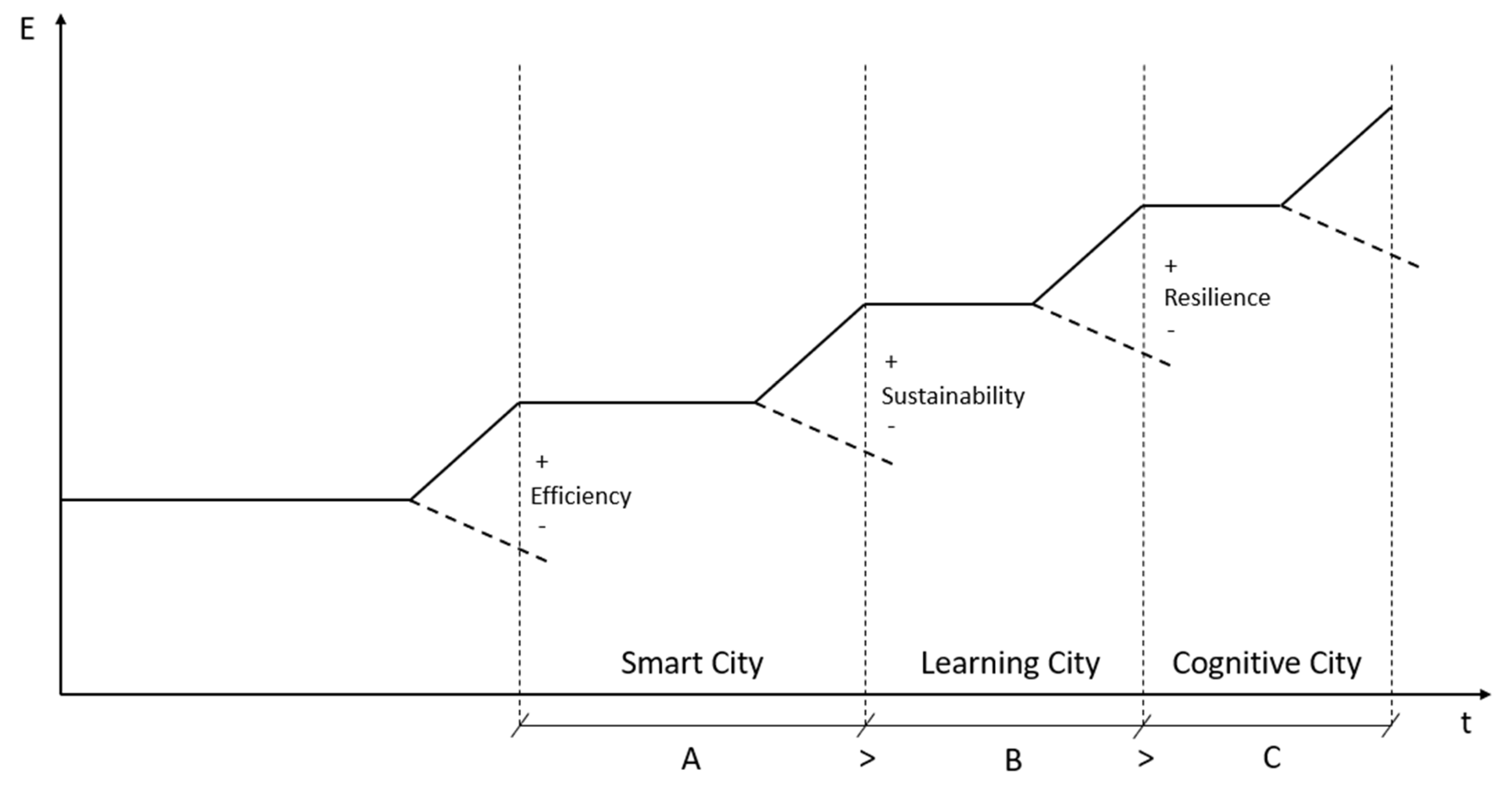

Finally, this implies that although crises and disasters, as transitional moments, catalyze systemic transformations, the so-called state of normality, even in the absence of disruptive events, is already a condition that demands improvement through the pursuit of resilience. As shown in

Figure 2, this paradigm shift involves replacing the pursuit of linear efficiency with a more flexible, resilience-oriented logic of system adaptation and reorganization. Indeed, while efficiency seeks to improve predictable performance under stable conditions or business as usual, resilience prioritizes adaptability, learning, and reorganization in the face of uncertainty, seeking alternatives and opening new paths. Adapted from Linkov et al. [

57], this visual highlights this crucial distinction needed when dealing with complex, dynamic systems such as cities.

Nevertheless, to define a clear progression toward resilience, it would be ideal to have a unit of measurement. One approach could be to identify several dimensions corresponding to the multiple qualities associated with resilience to draw a single multidimensional representation. However, this representation would not result in a continuous or complete plot form because progress towards resilience does not follow a constant growth, along a consistent and measurable line (one dimension) or surface (pluridimensional). Instead, the pursuit of resilience crosses thresholds of discontinuity of changing shapes, which act as transitional phases between different states of dynamic equilibrium in the system.

At each step, a new quality emerges in the system that is not simply equal to a greater quantity of the previous one. Rather, it is a new emergent quality that builds upon the previous one in a process that is not predetermined and therefore remains unpredictable. Only in retrospect does this progression appear internally coherent. For the sake of simplicity, we represent it as climbing the steps of a ladder.

This ladder model transcends the schema of resilience as a transformative journey discussed by the SMR project, which proposed maturity stages to guide urban transitions through performance indicators, stakeholder engagement, and iterative governance [

32].

Urban systemic evolution is not linear, but rather punctuated by bifurcations, critical thresholds that enable discontinuous transitions, where new organizational logics may emerge. The conceptual “ladder” in

Figure 3 schematizes this evolutionary trajectory, with time on the

x-axis and systemic evolution on the

y-axis, illustrating a gradual ascent toward urban resilience and potentially beyond. This representation echoes the dynamic observed in the evolution of living systems and innovation processes in business ecosystems [

58,

59,

60], as well as the scientific paradigmatic shifts described by Kuhn [

61]. It is important to emphasize that the evolutionary path can only be traced retrospectively from the system’s current position. Nevertheless, potentially at any given moment, conditions may arise that open the possibility for a bifurcation, enabling a divergent transition through critical decision-making and strategic reorganization.

This logic also suggests that bifurcations should not only be interpreted retrospectively as signs of systemic transition, but also proactively as strategic opportunities for transformation. Drawing on the evolutionary logic of complex adaptive systems, moments of instability and fluctuation can act as gateways through which locked-in systems escape path dependencies [

62]. In fact, as long as no bifurcation emerges, systems tend to remain constrained within a trajectory that reproduces existing structures and relations, even when these generate vulnerability, inequity, or dysfunction. Therefore, systemic disequilibrium is not merely a symptom of crisis but a precondition for creative divergence.

In this sense, bifurcations should be seen not as external disruptions but as windows of opportunity to reconfigure institutional logics, governance arrangements, or socio-technical configurations. This perspective resonates with the notion of chaos generativity explored in this paper—the idea that turbulence and ambiguity, when approached with strategic openness, can foster higher-order learning and innovation. It also reinforces the claim made by Reyers et al. that transformative resilience requires the intentional destabilization of dominant structures as a necessary step toward new equilibria [

63].

Consequently, resilience thinking must embrace uncertainty as an operational resource, not simply a threat to be managed, but a condition that enables anticipatory governance and strategic redirection. Thus, working with bifurcations implies reorienting planning from the pursuit of control to the cultivation of thresholds, where new organizational logics and collective visions can emerge.

Figure 4 deepens this understanding by illustrating the complex SETS as a coherent, multilevel, and nested system evolving along the previously outlined trajectory. It portrays increasingly short periods of dynamic equilibrium (steady state), interrupted by increasingly frequent fluctuation phases and successive bifurcations, which create opportunities for systemic reorganization. These fluctuation phases consist of two sub-phases: an accumulation period and a decision window. The latter is characterized by learning, exploration, and experimentation within the adjacent possible, ultimately guiding the system toward a breakthrough rather than a breakdown path. This dynamic aligns with the model of systemic stress accumulation and critical thresholds, where small failures cascade through interdependencies until a tipping point is reached [

64].

Notably, systems do not choose a bifurcation path instantaneously; instead, they enter periods of indecision, which can be prolonged, reflecting uncertainty, inertia, and the difficulty of constructing alternatives. This occurs not only because building viable alternative is challenging, often through trial-and-error mechanism, but also because there is no certainty that the new level of organization it is hypothesizing, the future it is envisioning, an innovation in its infancy, will work, be effective and stabilizing, or instead lead to unexpected and undesired consequences, or even to a worsening situation. Often, a critical or limiting situation is needed to break this inertia to change—a tipping point must be reached, either by hitting an extreme or by fully acknowledging a crisis already in motion. At that moment, the system must abandon the illusion of predictability and respond to the presence of unmanageable risk.

As such, resilience does not guarantee success but rather provides the courage and framework to make decisions despite not knowing whether the outcome will ultimately lead to stabilization, failure, or improved transformation of the system.

The reason why the system follows a step-by-step path, represented as a ladder of steps, rather than diverging into multiple alternative branching trajectories, lies in the progressive evolution of knowledge and capacity. As formalized through the principle of the adjacent possible [

8], organizational evolution emerges gradually, expanding outward from existing structures and diversities. This staged learning process is conceptually illustrated in

Figure 5, which shows how systems progress from incremental improvements in efficiency to deeper transformations enabling resilience.

Figure 5 illustrates two stages of this: the first step represents a repetition-based improvement, achieved through replication with analogical duplication across parallel and mirrored series, which leads to a linear reinforcement of the existing structure. The second step requires a deeper transformation, involving a second-degree modification through rotation, which additionally demands a simultaneous shift in perspective and action, which brings about a structural reconfiguration and enhanced adaptive capacity. Thus, resilience is not merely about performing familiar things more efficiently, but about learning to reframe problems, adopt new vantage points, and activate new relational configurations that enable the emergence of novel systemic coherences.

A key consideration is that resilience emphasizes qualitative transformation rather than quantitative accumulation. As illustrated in

Figure 5, a small number of new connections can significantly increase a system’s capacity to reorganize and adapt, while improvements in efficiency often require greater input with diminishing systemic returns. This highlights how scale-sensitive effectiveness, the ability to generate impact by leveraging minimal but strategic changes, may be more critical than traditional notions of optimization. Indeed, ecosystems evolve, becoming increasingly complex, through the diversification and intensification of interactions among their components, enabling the emergence of new properties and relational capacities [

2,

66].

This wonder prompts to the fractal formation, which nature is full, enabling complex systems to develop new qualities out of quantity growth of repetition, which in nature occasionally give rise to changes, which introduce diversity into the system, which in turn must face selection devoted to maintaining only those that are advantageous and thereby giving rise to divergent (bifurcations) paths of evolution. The concept of resilience as learning reinforces the idea that adaptive pathways are constructed retroactively, but through decision-making and trial looking ahead, as emphasized by Folke [

12] and Björneborn [

42], pointing toward a future that is not planned but co-evolved.

3.3. Processes, Actors, and Domains for Systemic Resilience Development

This framework views the anthropic environment as a complex SETS. Within this, our interest lies in understanding how capabilities can be selected and processed according to the situation that requires the system to employ them in the process of evolutionary resilience. Since specific characteristics of problems cannot be known in advance, we present a typological analysis of the situation based on the degree of simplicity, inversely related to its complexity. This conceptual framework reflects the four-part structure of the Cynefin framework for decision-making proposed by Snowden [

67], and draws on the early distinction introduced by Weaver [

68] between problems of simplicity, disorganized complexity and organized complexity, today reframed in the lens of uncertainty management and adaptive governance.

The integrated Urban Resilience Matrix presented in

Table 1 illustrates through numbers the order in which different domains of the system are activated depending on the type of situation, requiring the pursuit of resilience. This matrix aims to explicitly outline how capabilities are developed and activated, which actions follow decisions, and who and how to involve based on the type of problem being faced. This perspective reflects the need, highlighted by Walker et al. [

56], to align decision-making to the adaptive cycle of resilience, allowing cities to shift between phases of conservation, release, reorganization, and exploitation depending on system pressures and community capabilities.

By following this matrix, urban resilience processes can be better understood and facilitated. Through a correspondence empirically made between different established frameworks looking at the problem from different perspectives, it also refers to:

The nature of the system in accordance with Weaver [

68];

The type of planning practice experts are called upon to implement, following de Roo’s [

69] planning in uncertainty model, which moves from rational-comprehensive to communicative and reflective strategies;

The level of community participation, following Arnstein’s ladder [

70], ranging from manipulation and tokenism to full citizen control.

According to the four-part typological structure, it is described below how problems calling for resilience are addressed using a sequential activation process of the system domains, following the order of steps proposed in the matrix. It also discussed the implications for the agents involved.

Simple: In this scenario, the community follows a predetermined hierarchical structure, and individuals are relegated to the role of passive recipients within a top-down system. Decision-making is centralized, as is the configuration of the governing network. The necessary resources have been allocated in advance and are readily available. The activation process involves following a codified procedure in a repetitive manner or replicating a proven best practice. These conditions correspond to the engineering resilience phase, where robustness and efficiency prevail over flexibility or learning.

Complicated: The decision-making process involves initiating an analysis phase where the actively involved community only consists of experts who study the best approach to solve a specific case. The network structure remains hierarchical but decentralized, with multiple parallel verticals in various fields of interest stemming from a central decision-making body. The necessary resources are mobilized to identify and implement good practices that can be continuously improved through the analysis of results and approximation through iteration cycles toward a knowable optimal. Here, resilience is seen in terms of system optimization, and the prevailing model remains technocratic, though enriched by feedback loops. Experts play a dominant role in this phase, aligning with problem-solving rationality.

Complex: In situations characterized by uncertainty and ambiguity—often referred to as “wicked” problems, one or more parallel experimental processes, based on trial-and-error and safe-to-fail approaches, are put in place to explore possibilities [

71]. The necessary resources are estimated and gathered to initiate these processes. Decisions are made regarding which processes to nurture and which to dampen, and learning from mistakes is emphasized. The process involves analyzing and internalizing the practices that emerge, incorporating useful insights, and embracing serendipitous discoveries. Communities are formed from the bottom-up around the shared purpose of addressing the situation, through the creation of distributed networks that, in learning-by-doing practice, are guided by the coherence of the situation, which emerges acting as an attractor for more beneficial coherence. This condition reflects what Folke [

12] and Reyers [

14] call “evolutionary resilience” or “transformative capacity,” where co-learning, social networks, and institutional flexibility enable transitions.

Chaotic: In chaotic situations, the community must take immediate action to address an emergent situation, such as the need for innovation (e.g., develop a vaccine) or to overcome crises. Effective planned coordination between agents is usually lacking, and if it arises is an unpredictable or random result. Available resources are rationed for survival or repurposed to drive change, working like exaptation in biology, by which a causal consequence of a part of an organism that might turn out to be useful for some other purpose in some environment is selected. The decision-making process is new, and decisions are primarily focused on avoiding catastrophic consequences, or, if it comes too late, it may simply acknowledge a new state of equilibrium that the system has already achieved autonomously. The collective effort binds the community into a recognizable and holistic systemic entity, yet each agent at the same time feels individually free to search for its own benefit. From an external observer’s perspective, the system can be seen at the same time both as a cohesive wave and as a collection of different particles.

3.4. From Integrated Matrix to Transformative Governance

This chaotic condition highlights the need for civic resilience, an improvisational, emergent capacity born out of relational ties and spontaneous innovation, not structured planning [

51]. In this phase, radical community-based governance strategies become essential, enabling new urban meanings and practices to emerge through bottom-up processes. Resilience capabilities can be operationalized only through a phased transition of governance from prescriptive control to enabling co-creation, underlining the relevance of learning-by-doing in dealing with complex and chaotic urban dynamics.

In this frame, resilience is not an attribute of the system but the very process through which actors interact and improvise under urgency. A resilience-based approach to urban governance must recognize and integrate dynamic interplays among domains, processes, and actors, embedding flexibility, adaptability, and trust as structural values of the system.

Nowadays, following the accelerated evolution of human civilization, both in tangible development and epistemological understanding, the significance of system domains and processes has shifted along both horizontal and vertical axes of the integrated Urban Resilience Matrix (

Table 1):

Horizontally, the domains’ relevance progresses from foundational preconditions toward potentiality-building.

Vertically, the system moves from processes driven by predetermined goals (simple and complicated problems), through those addressing underlying causes (complex issues), to means-driven processes (chaotic problems), where means themselves become ends in response to urgent needs.

While speed differentiates complicated from chaotic challenges, chronic, long-term problems (e.g., Taranto) can likewise create a highly confusing, if not chaotic, context.

As communities navigate urban complexity, they seek a delicate equilibrium between complexity and chaos, a point of creative tension [

72]. Multiple rapid innovations must become integral, not peripheral; yet traditional institutions, structured to manage simple or complicated problems, struggle to operate within this dynamic landscape.

This gap between institutional rigidity and emergent realities intensifies difficulties. While new forms of governance may arise, existing institutions maintain formal power; they must internalize changes, including grassroots innovations. Without proper recognition and support, such grassroots initiatives risk fading, even if they hold high potential for systemic evolution.

These observations reinforce a core idea: urban resilience is not a fixed outcome, but a dynamic capacity to be cultivated. It arises from the interaction between spatial, institutional, technological, and cognitive urban system dimensions [

73]. This requires abandoning the illusion of engineered, deterministic resilience and embracing it as a qualitative property of change. Resilience becomes an emergent result of system learning, innovation, and adaptation—not a state that can be directly planned or imposed, but one enabled by anticipatory, inclusive, and reflexive governance [

27].

Digital infrastructures and ICTs must function beyond support tools: they should enable local learning, coordination, and bottom-up innovation, empowering communities as active agents of change.

The process-based framework presented in this paper, with its evolutionary ladder and scenario structure, serves as a roadmap for transformative governance. It demonstrates how different domains are activated across contexts and how governance can shift progressively from centralized control to distributed facilitation, situating community capacities and social networks at the heart of resilience processes.

From this perspective, resilience is the capacity to open new spaces of possibility, previously limited by existing constraints, through iterative recombination of available resources, practices, and institutions. This form of creativity is both technical and profoundly social, demanding new planning epistemologies that embrace experimentation, plurality, and collective learning.

Understanding resilience this way reveals a critical gap between institutional structures and the actual functioning of cities. This underscores the need for new governance and decision-making processes capable of structurally responding to unexpected and chaotic urban dynamics.

To foster a flexible, agile urban management system, one that moves beyond traditional managerialism toward community-centric governance, it is crucial to derive necessary insights and translate them into actionable requirements. By aligning governance modalities with the right means and scopes, the Ladder framework nurtures resilience from the community level upward. This shift equips governance to effectively address unsustainable dynamics and support communities faced with conflicting choices and chronic crises.

4. Discussion: From Top-Down Implementation to Communities Co-Creation

Whether in biological systems, species evolve in response to changes in the external environment. For example, the ongoing natural selection of bacteria enables them to develop resistance to antibiotics. In social systems, individuals have developed the capacity to communicate, imagine, invent, and strategically act in anticipation of future situations. System components and agents possess the ability to learn and intentionally generate new knowledge, thereby influencing the behavior of the system through their teleonomic interventions.

This parallels what in complex adaptive systems is referred to as the capacity for self-organization and reflexive adaptation, two features that distinguish socio-ecological systems from mechanistic models of control and optimization. These capacities are essential in non-equilibrium environments where prediction is no longer a viable planning tool and learning-by-doing becomes the main vector of governance.

Complex and chaotic situations give rise to emergent solutions, prompting significant efforts to understand and harness the process of innovation in place. There has always been a quest to define that elusive “magic formula” composed of numerous qualities, which also comprise those labeled as resilience. It is through their process-based use that individuals, groups, and humanity have historically managed to succeed, even in the most challenging and desperate circumstances.

On the other hand, the state of confusion, the questioning of the status quo, established ideas, and perspectives, as well as the need to solve overwhelming problems, served as driving forces to materialize creative inspiration. The ultimate aspiration is to transition from foresight to anticipation, systematically guiding the system in the desired direction that resonates at a profound level as if it were already present, but rationally unknown.

In this sense, the concept of the adjacent possible becomes particularly relevant: resilience does not imply a return to the previous state, but rather the opening of new, often unexpected, plausible paths that emerge from existing system potentials. These paths are not linear and require a readiness to embrace uncertainty, ambiguity, and cognitive dissonance as conditions for generative change.

This perspective offers a constructive reinterpretation of the human tendency toward control, fostering greater awareness of the limits of prediction and of the actual effectiveness of emergency management. It echoes the argument made by Linkov (2018), who distinguishes resilience from efficiency, noting that while efficiency seeks performance optimization in a known domain, resilience seeks viability and adaptation under uncertainty and surprise [

57].

Therefore, by recalibrating the concept of management from government to governance, there is a growing understanding of the necessity to collaborate closely with communities to establish the preconditions for such a spontaneous emergence of opportunities and capacities for ascending the Ladder of Urban Resilience.

This requires transitioning from reactive and procedural management to proactive and reflexive governance models that allow citizens not only to be recipients of measures but co-creators of transformative trajectories. However, despite agreeing on the effectiveness of building urban resilience involving a mutual and accountable network of civic institutions, agencies, and individual citizens working in partnership towards common goals within a common strategy [

74], no further details have been provided.

Based on the framework presented in the previous chapter, intended to better describe the actual urban approach to problem-solving, the following paragraphs propose guidelines for accompanying communities coherently with their contextual conditions in developing resilience from within, to finally harnessing complex or chaotic problematic situations. To facilitate this progression, a breakdown is identified, comprising three interdependent levels, each building upon the other, for as many scenarios acting as smaller steps that can be more easily climbed by communities (

Figure 6).

This multilevel view of governance and learning supports cities in moving from command-and-control modalities toward adaptive, collaborative, and anticipatory resilience governance. The ladder is not only a metaphor, but a concrete sequence of scaffolding mechanisms to enable communities to mature their resilience capabilities.

Nevertheless, it is essential to state clearly that this community-centered perspective should not be misconstrued as an excuse to absolve governments of their responsibilities. Instead, it calls for a renewed role of institutions that can actively support communities throughout this progression, providing less constraining top-down assistance. By doing so, authorities can ensure that communities are not burdened with the sole responsibility of building inherent and self-sustaining resilience, along with the associated risks and consequences [

75,

76,

77].

4.1. The Baseline Scenario

As previously discussed, urban resilience should not be understood as the mere inverse of vulnerability, where an increase in one automatically implies a decrease in the other. It requires careful attention to contextual analysis and the elicitation of local knowledge regarding both the intricacies of the problems and the resources available within the local context to address them. Thus, in the baseline scenario, the priority is to involve and empower community members in the planning and decision-making processes. This scenario corresponds to what we define as a condition of adaptive participation, where resilience emerges primarily through the recognition of local knowledge, the strengthening of social ties, and the activation of collaborative practices that enable communities to prepare, adapt, and respond effectively to change. This includes engaging residents, local businesses, and other stakeholders in the development of strategies and policies, ensuring that their needs and priorities are considered. Additionally, several complementary aspects are encompassed within this scenario, ranging from intangible to tangible measures. Some examples include:

Developing social networks and enhancing community cohesion, as stronger social connections and a sense of community can foster mutual support during emergencies.

Improving access to information and resources, ensuring that people have access to accurate and timely information, as well as essential resources like food and emergency shelter, enabling effective responses to unforeseen disasters.

Promoting and encouraging sustainable practices, such as recycling, reducing energy consumption, and preserving green spaces, to ensure resource availability for future generations.

Cultivating a culture of preparedness through education and awareness campaigns, equipping residents with the knowledge and skills to better prepare for emergencies and mitigate their impact.

Building diverse and redundant urban systems, including multiple transportation options, diverse energy and water sources, and a variety of housing types.

By implementing these inclusive and reformist measures, communities can foster resilience by empowering their members, promoting cooperation, and developing sustainable practices. It is crucial for governments and institutions to actively support and collaborate with communities in these efforts, recognizing the shared responsibility and the benefits of a collective approach to resilience building.

Moreover, this scenario reflects what several scholars have defined as the preparedness culture [

50], where social capital, community competence, and shared narratives form the foundation of resilience. While often seen as a preliminary phase, this baseline configuration already reflects a maturity level within the urban system that can unlock endogenous potentialities through slow, accumulative dynamics [

32,

56].

However, the capacity to empower communities should not be assumed as intrinsic: it must be intentionally cultivated through processes that make use of enabling tools, facilitation strategies, and equity-oriented planning [

51]. At this level, planners and facilitators play a crucial role in supporting relational infrastructures and ensuring that inclusive participation is not only symbolic but translates into collective agency capable of triggering micro-innovations and mutual aid [

78].

4.2. The Critical Scenario and the Role of ICT

The situation becomes more critical in circumstances that generate dilemmas, where the roots of malfunctions and disasters lie within the structure and operating mechanisms of the system itself. It becomes difficult to identify and address such dysfunctions without risking the system’s overall survival, as doing so may trigger unintended consequences that are more damaging than the original problem, for example, social unrest. Moreover, building alternative strategies that are acceptable to all system agents, without undermining consolidated organizational structures (often fortified by long-standing individual or institutional interests), proves equally challenging. Urban resilience under these variable conditions is already a dynamic and continuous process. Cities must constantly adapt and evolve in response to shifting priorities and emerging challenges, making the mere application of best practices or static guidelines insufficient or even obsolete. For this reason, internal monitoring systems should be established to track progress and assess the long-term effectiveness of regulations and policies. This enables the identification of decisions that contribute to resilience and those that require revision or realignment.

These conditions make it clear that a comprehensive and adaptable approach to resilience is essential, one that exceeds the reactive logic of the baseline scenario. This upgraded approach is specifically tailored to systems grappling with conflicting priorities and competing values within a continuously evolving landscape.

In such a critical scenario, cities should adopt a participatory approach to foster dialog and collaboration among stakeholders. This allows for the evaluation of alternative strategies and supports the negotiation of competing goals and interests. The goal here is to activate inclusive decision-making processes capable of mediating between divergent visions and perspectives. The proactive involvement of diverse stakeholders, including citizens, public administrators, and private actors, becomes crucial in enabling systemic learning and adaptive policymaking [

79]. This also implies building institutional capacities for conflict resolution, iterative governance, and participatory diagnosis, all essential to managing structural tensions and dilemmas.

In this context, several key strategies can be implemented:

Identifying the root causes of systemic problems through structured problem analysis, enabling a better understanding of underlying conflicts and more effective solution-building.

Establishing targeted engagement with diverse stakeholder groups (e.g., citizens, officials, business leaders) to build shared ownership and legitimacy.

Creating coalitions of community members, civil society organizations, and institutional leaders to generate political will and enable systemic change.

Promoting the development of multiple, flexible, and complementary solutions that can adapt over time, instead of relying on single, rigid interventions.

Exploring alternative, bottom-up pathways such as self-governance, community-based arrangements, or legal challenges to regulations that sustain deadlocks.

It is important to recognize that inclusive decision-making, while instrumental in identifying new opportunities and mobilizing change, does not guarantee the achievement of resilience in such complex settings. Rather, it constitutes a precondition for it. Under these circumstances, resilience becomes a practice of negotiation and compromise, not aimed at maximizing consensus, but at maintaining systemic adaptability and preventing collapse. Planners play a key role in facilitating this beneficial pathway while accounting for a range of stressors, such as economic or environmental pressures, that constrain communities entrenched in rigid path dependencies.

This scenario aligns with what Reyers et al. [

63] define as deliberative resilience, where adaptation processes are no longer linear but must reconcile conflicting priorities across spatial scales and time horizons, while simultaneously responding to the urgency of crisis conditions. It is precisely in these contexts that systemic dilemmas, feedback loops, and power asymmetries become visible, requiring a form of “soft” governance infrastructure capable of interpreting complexity rather than reducing it [

13,

64].

ICT-Enabled Awareness and Co-Governance for Resilience

At this stage of the incremental journey toward resilience in complex Social-Ecological-Technological Systems (SETS), Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) can play a pivotal role, offering the advantage of continuous functionality. As such, ICT tools—typically conceived as means—may become ends in themselves, provided that they are not merely adopted, but actively adapted to context. In this way, technology evolves from a tool of “smartness” to an instrument of “wisdom”.

ICTs should therefore be understood not just as tools for automation or efficiency, but as enablers of awareness, distributed sensing, and relational intelligence. Digital platforms that visualize interdependencies and cascading risks can foster both anticipatory governance and collaborative learning. At a basic level, these tools, when combined with data analytics, can identify patterns and trends, support evidence-based decision-making, and suggest timely interventions [

80].

Indeed, all the strategies mentioned in the

Section 4.2 can benefit from technological innovations if these are adapted to extend and enhance the capacities of individuals and communities [

81]. When it comes to enabling social, urban, and environmental resilience, technologies must address three key dimensions:

Raising awareness of the interdependence between individuals and communities, fostering collaboration and information-sharing.

Assisting communities in identifying and achieving long-term social and environmental balance.

Supporting behavioral change in response to risk factors, disruptions, and disasters.

Aligned with these goals, the ReCITY project has been involved in the co-design and impact evaluation of ICT platforms according to the following principles:

WHY—Designed to empower citizens through access to training, information, and activation pathways.

WHO—Targeted at all governance stakeholders to support transparent and resilient decision-making.

WHAT—Focused on detecting and amplifying everyday practices of resilience, transforming them into shared and scalable innovations.

HOW—Developed as ICT platforms that are:

- ○

Sentient: Able to collect, process, and respond to data contextually.

- ○

Customizable, updatable, and reusable: Ensuring long-term adaptability.

- ○

Citizen-centric: With accessible and intuitive interfaces for non-expert users.

- ○

Equipped with pervasive sensor networks: Creating an intelligent communication and infrastructure layer—a “nervous system” for the city.

By adopting this model, ICTs can support the resilience-building process by enabling multi-actor coordination, enhancing local knowledge, and fostering anticipatory planning and responsiveness to crises [

82].

Crucially, technologies must not only detect change—they must support the governance of ambiguity. Platforms can be designed to stimulate imagination, foster collective creativity, and facilitate the emergence of alternative futures, especially by helping communities break free from institutional path dependencies. When properly conceived, ICTs function as boundary objects that bridge knowledge systems, institutional silos, and temporalities. This vision was operationalized within the ReCITY project through the co-design of digital platforms supporting both community-based and institutional resilience. These platforms pursue a dual purpose: they foster horizontal collaboration and solidarity among citizens while enabling two-way communication with governance institutions. Together, these infrastructures constitute an integrated “nervous system” for the city, enhancing its ability to adapt, respond, and co-evolve across levels. Such dual connectivity allows diverse and fragmented practices to be reassembled into a shared resilience strategy, supporting both emergency response and long-term sustainable development.