1. Introduction

Climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental degradation are escalating global crises driven by human activities [

1,

2,

3,

4]. To address these challenges, individuals must develop environmental responsibility and engage in solution-oriented actions [

5]. The United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs) promote sustainability across the environmental, social, and economic areas, urging active participation in these efforts [

6]. In this context, younger generations are crucial in shaping a sustainable future, not only as future leaders but also as key influencers of current environmental and social dynamics. Strengthening individuals’ capacity to act as environmental citizens is increasingly recognized as a vital condition for achieving sustainability goals, which remain at the forefront of both European and global environmental priorities. The 2020 World Economic Forum’s Davos Summit highlighted that youth-led initiatives emphasize the importance of intergenerational collaboration in climate action, illustrating the profound role of environmental citizenship education [

7].

Schools play a critical role in shaping students’ environmental responsibility, not only through cognitive instruction but also by functioning as early socialization environments. During primary education, children develop emotional, ethical, and civic orientations that serve as the foundation for later engagement in sustainability issues and environmental citizenship [

8,

9]. Research shows that early experiences with nature in educational settings, especially those that involve emotional connection and peer interaction, are strongly associated with long-term commitment to pro-environmental behaviors and civic participation [

10]. Thus, environmental citizenship education should be understood as a process involving not only knowledge but also the emotional and social development of children within formal school environments.

Raising awareness of sustainability is not enough; individuals must be empowered to engage in environmental decision-making [

11]. Environmental citizenship provides a comprehensive framework, viewing individuals as active and responsible citizens, not just conscious consumers, within the sustainability process. It is a form of democratic citizenship that promotes sustainability and civic engagement by assigning local and global responsibilities [

12]. This requires individuals to not only adjust their personal environmental attitudes but also play an active role in shaping sustainability policies [

13]. Environmental citizenship education (ECE) encourages individuals to fulfill their environmental rights and responsibilities and actively engage in sustainability policies [

14]. It goes beyond fostering environmental sensitivity, incorporating both social and political engagement to tackle environmental issues [

15,

16]. UNESCO [

17] stresses that early environmental citizenship education promotes sensitivity and helps individuals to take both individual and collective responsibility.

In this context, scientific literacy plays a pivotal role in shaping environmental citizenship, particularly during the early years of education. Developing scientific literacy helps students to make sense of ecological systems, evaluate sustainability issues, and take informed action based on evidence, all of which support the growth of environmental responsibility [

18]. Recent research also shows that when school-based environmental programs combine scientific inquiry with socio-emotional learning, students are better able to connect their local actions to broader environmental outcomes [

19]. These integrative approaches not only strengthen children’s sense of agency but also support the development of environmental literacy as an active form of citizenship.

Environmental citizenship education at the primary school level is key in raising children’s environmental awareness and promoting sustainable lifestyles [

20,

21,

22]. Early interaction with nature increases the likelihood of environmentally responsible behaviors in adulthood [

10,

23], and direct exposure to nature is one of the most effective methods to enhance environmental awareness [

24,

25]. Through nature-based learning, children internalize environmental values not only theoretically but also experientially.

This study explores how environmental citizenship education (ECE), implemented within the Nature and Science School (NSS) framework in Türkiye, is experienced and interpreted by primary school pupils through direct engagement with nature. While environmental education at early ages is widely acknowledged as essential, there is a lack of in-depth research on how structured, nature-based programs contribute to children’s understanding of sustainability and environmental responsibility within formal educational settings. Grounded in a holistic single-case study design, this research examines pupils’ reflections and narratives to uncover how they construct meaning around environmental citizenship and sustainability through experiential learning. The study aims to offer context-specific insights into the pedagogical value of nature-based education and to inform both academic discourse and educational policy focused on fostering active, sustainability-minded citizens from an early age.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Environmental Citizenship and Education

Citizenship refers to full membership in a community, involving equal rights and responsibilities [

26]. It extends beyond legal relationships, encompassing active participation in social, economic, and political processes [

27]. Citizenship education fosters democratic engagement and develops essential skills, such as media literacy, social awareness, and civic responsibility [

28]. Environmental citizenship builds on this concept, offering an expanded view of traditional citizenship. Environmental citizenship is described as an interdisciplinary concept with varying definitions depending on the context [

29]. The concept’s multidimensional nature moves beyond fostering environmental attitudes to require individuals to uphold their environmental rights, engage in sustainability policies, and play an active role in environmental decision-making [

14,

15].

The framework for environmental education was established by the Tbilisi Declaration in 1977, promoting environmental awareness, knowledge acquisition, ethical values, and active engagement in solving environmental issues [

30]. Grounded in an interdisciplinary approach, it aims to integrate ecological, social, economic, and cultural dimensions, fostering responsibility for environmental protection. However, many programs focus primarily on individual awareness, often neglecting collective action [

31]. Environmental citizenship education (ECE), based on the Tbilisi principles, extends this approach by encouraging not only understanding but also ethical actions supporting sustainability. ECE aims to instill environmental justice, encouraging sustainable relationships with nature and active engagement in environmental challenges [

32]. Unlike traditional education, ECE emphasizes responsibility at both personal and societal levels and participation in environmental decision-making [

31].

Discussions now focus on structuring environmental citizenship within education. ECE is seen as promoting both environmentally friendly attitudes and societal transformation towards sustainability [

14]. According to the European Network for Environmental Citizenship, “Environmental citizenship education empowers individuals to solve environmental problems through individual and collective actions, ensuring sustainability and supporting a lifestyle in harmony with nature” [

32]. ECE not only promotes environmental rights and responsibilities but also equips individuals to analyze structural causes of environmental degradation and take democratic action to address these issues [

15]. ECE encourages environmentally responsible behaviors in both private and public spheres, playing a key role in preserving ecosystems and combating climate change [

33]. It should be seen not only as raising awareness but also as promoting participation in environmental governance. Recent empirical evidence confirms that nature-based ECE programs significantly enhance children’s environmental understanding, critical thinking, and agency when embedded in outdoor, inquiry-based learning environments [

34]. These programs promote long-term behavioral commitment to sustainability and foster environmental identity formation during children’s early years [

8].

Studies on environmental citizenship highlight individuals’ roles in developing sustainable solutions and contributing to society through environmental actions [

35,

36]. In this context, the ECE model presents a multidimensional pedagogical framework that includes research, sustainable solution generation, social participation, and applying knowledge through environmental action [

37]. Similarly, a recent study found that Dutch pupils recognize the importance of sustainability issues and acknowledge the risks posed by our current unsustainable lifestyle [

38]. These pupils expressed concerns about these issues and highlighted how ECE can address them. It has been noted that ECE and education for sustainability share similarities, both aiming to mobilize individuals towards sustainability, although with differing educational priorities [

39]. ECE differs from traditional environmental education by not only providing environmental knowledge but also developing environmentally literate and sustainability-conscious individuals who make informed decisions, engage in environmental issues, and contribute to solutions [

40]. Thus, ECE is a dynamic process that fosters skills in evidence-based decision-making, creative problem-solving, and civic engagement [

41].

ECE takes a holistic approach by encouraging individuals to translate environmental awareness into sustainable actions through direct engagement with nature. To be effective, both formal and non-formal learning environments must complement each other. Nature-based education, field studies, museums, zoos, visitor centers, and ecological parks offer opportunities for hands-on engagement with environmental issues, enhancing awareness and sensitivity [

42]. Recent international comparative findings indicate that education systems integrating nature-based experiences and green skill development from early stages are better positioned to convert environmental awareness into collective civic action and systemic change [

43]. Studies have also shown that nature-based environmental education not only enhances pupils’ knowledge about the environment but also supports their emotional connection with nature [

44].

However, environmental education must align with children’s cognitive and emotional development. Exposure to abstract and complex environmental issues can lead to anxiety and diminished motivation [

45]. This underscores the importance of ECE moving beyond theoretical knowledge, incorporating experiential learning that enables children to interact with nature. Nature centers, museums, and ecological parks allow pupils to explore environmental challenges and develop problem-solving skills [

46]. Therefore, creating learning environments that foster direct interaction with nature and promote active participation is crucial for effective ECE.

2.2. Nature-Based Learning Environments: The Nature and Science School Model in Türkiye

Nature education is a learning approach that enables individuals to develop environmental awareness and acquire sustainable life skills through direct interaction with nature [

47]. In Türkiye, nature education programs supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council (TÜBİTAK) aim to promote ecological awareness across various age groups through structured activities [

48,

49,

50]. In addition, Nature and Science Schools (NSSs), established under the Ministry of National Education (MoNE), represent a significant step in integrating nature-based education into the formal education system. These schools provide pupils with direct engagement in natural environments while supporting environmental learning through hands-on experiences.

In the Turkish primary education system, environmental education is not taught as a standalone subject but is instead dispersed across disciplines such as life sciences, science and technology, and social studies. As a result, pupils’ prior knowledge tends to be fragmented and varies depending on textbook content and teachers’ instructional emphasis [

51,

52]. While recent curriculum reforms have introduced basic environmental themes, such as resource conservation, recycling, and sustainable living, these are predominantly delivered at the level of factual knowledge and conceptual awareness. In the early grades, for instance, environmental learning typically involves identifying sources of water and energy, recognizing the importance of saving resources, or distinguishing between natural and artificial elements. However, these themes are seldom integrated with hands-on experiences, inquiry-based exploration, or opportunities for civic engagement. Their depth, scope, and classroom implementation often rely heavily on individual teacher discretion and available resources. Consequently, pupils’ baseline understanding prior to the ECE program was limited to surface-level ecological awareness, with minimal exposure to the civic dimensions of environmental rights, responsibilities, or collective action. This contextual gap may help to explain the significant conceptual and emotional shifts observed after the intervention, as the NSS model not only expanded pupils’ contact with nature but also promoted environmental responsibility through immersive, participatory, and socially contextualized learning experiences.

Internationally, the NSS model aligns with nature-based approaches like forest schools and outdoor learning environments. It is designed to enhance children’s environmental awareness by immersing them in authentic outdoor settings [

53]. The model was first implemented in 2019 in Erdemli, Mersin, as the “Sea and Forest School.” Encouraged by the Ministry of National Education, the model was later revised and officially disseminated across the country under the title “Nature and Science School” [

54,

55,

56]. Since then, the model has expanded to cities such as Kahramanmaraş, Istanbul-Çatalca, and Samsun-Canik, supporting education in natural environments.

In practice, pupils and teachers apply to their respective district directorates of national education to schedule full-day (6–7 h) participation in NSS activities under the guidance of trained educators. Although NSSs are part of the formal education structure, they offer an alternative pedagogical model centered on nature-based and experiential learning. Unlike traditional classroom-based instruction, pupils at NSSs engage in exploratory and interdisciplinary learning in open-air settings.

It is also important to consider the positioning of NSSs within the broader context of out-of-school learning. Despite being institutionally embedded within the national education system, NSSs incorporate non-formal educational approaches that promote active, nature-based engagement. Pupils experience structured yet flexible learning that goes beyond the boundaries of classroom walls, offering opportunities to explore themes such as environmental citizenship education (ECE), sustainable development, and ecological responsibility. This aligns closely with the framework for education for sustainable development, which advocates for extending environmental education beyond classrooms to include direct experiences in nature [

17].

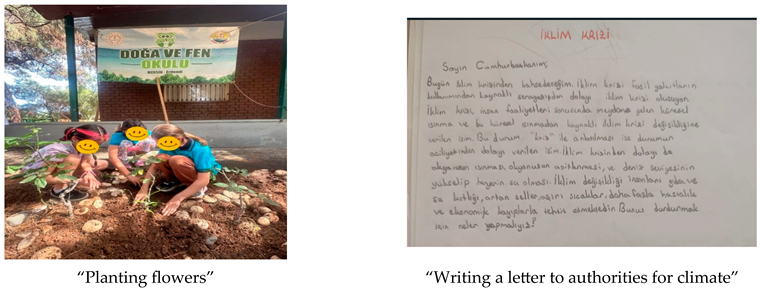

At NSSs, pupils participate in interdisciplinary outdoor learning activities on topics such as zero waste, environmental literacy, the global climate crisis, endemic plant species, and the integration of nature into subjects like science, mathematics, and the arts. Although the existing NSS curriculum primarily focuses on environmental education, this study introduced a specially designed environmental citizenship education (ECE) program into the NSS model and implemented it in conjunction with pupils’ regular schooling. The program was delivered both during pupils’ time at the NSS and throughout the school year, ensuring a continuous and embedded educational experience.

In Türkiye, Nature and Science Schools (NSSs) offer pupils valuable opportunities for direct interaction with nature, contributing meaningfully to ECE by immersing learners in sustainable living practices. While these programs are expanding, further research is required to evaluate their impact on pupils’ environmental awareness and sense of responsibility. The UNESCO framework emphasizes the importance of introducing environmental citizenship education at an early age and highlights that such efforts should not be limited to formal schooling, but should also include non-formal and experiential learning environments [

17].

2.3. Research Context and Objectives

This study aims to explore how environmental citizenship education (ECE) at Nature and Science Schools (NSSs) influences pupils’ perceptions of environmental citizenship, their views on environmental issues and sustainability, and how they understand and experience these concepts during the educational process. The research focuses on pupils’ definitions of environmental citizenship, their self-perception as environmental citizens and advocates, their awareness of environmental problems, and the transformation of their understanding of the global climate crisis and sustainability. Additionally, the study examines pupils’ views on the nature-based ECE program within the NSS setting.

In Türkiye, science education is predominantly delivered through traditional classroom-based methods, with limited integration of alternative, nature-based learning models. This lack of exposure to interdisciplinary and nature-based approaches, such as ECE, presents challenges to their widespread adoption. Nature and Science Schools offer an innovative solution by providing experiential learning opportunities that foster awareness, responsibility, and action on environmental issues through nature-based activities. This research aims to understand the experiences of primary school pupils participating in the ECE program within the NSS and how these experiences evolved throughout the process. Accordingly, the research question guiding this study is as follows: “What are the experiences of primary school pupils regarding the environmental citizenship education implemented in the Nature and Science School?”

Sub-questions:

How did the pupils’ perceptions of the concept of environmental citizenship evolve through the educational process?

How did pupils’ awareness of environmental issues and the global climate crisis develop throughout the program?

How did pupils’ understanding of sustainability concepts change during the educational process?

How did pupils experience the environmental citizenship education in the Nature and Science School, and what are their views on this program?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study uses a case study approach, specifically a holistic single-case study model. Case studies allow for the detailed analysis of one or more cases [

57], while holistic single-case studies focus on thoroughly examining a single unit, such as an institution or program [

58]. In this study, the environmental citizenship education (ECE) process at a Nature and Science School (NSS) was treated as a single case, aiming to assess its impact on primary school pupils. The objective was to understand how ECE in a natural setting affected pupils’ environmental awareness and experiences. Although five state schools participated, the study did not focus on inter-school comparisons. All pupils experienced the same ECE program. The NSS’s physical features were considered to ensure an optimal learning environment. Data were collected at three stages—before, during, and after the program—enabling a progressive analysis of pupils’ experiences and a comprehensive evaluation of how the program influenced their environmental attitudes and behaviors over time. The research process is outlined in

Figure 1.

3.2. Participants

The participants of this study were selected using criterion sampling, one of the purposeful sampling strategies frequently employed in qualitative research. Establishing clear criteria is essential in case studies to ensure the most appropriate selection of the case under investigation [

59]. In this study, schools were selected based on their ability and willingness to participate in the NSS program. Only schools whose pupils had the means to attend the NSS and whose class sizes did not exceed 25 pupils were included, taking into account the physical conditions and capacity of the NSS facility. Pupils from schools meeting these criteria were included in the study. The study group consisted of 88 fourth-grade primary school pupils (aged 10) from five public schools located in the Erdemli district of Mersin, Türkiye. Of the participants, 42 were boys and 46 were girls. Participation was voluntary, and information about the study was shared with classroom teachers via the Mersin Provincial Directorate of National Education. Based on voluntary consent, five classroom teachers from the selected schools agreed to participate and supported the process. The participating schools were observed to have similar socio-cultural characteristics, and the participating teachers were described as pupil-centered and idealistic, each with an average of 20 years of teaching experience. Although no direct data were collected from the teachers, general information about their professional background and classroom approaches was included to illustrate the similarities in the pupils’ formal learning environments outside of the NSS. The demographic characteristics of the participating pupils and teachers are presented in

Table 1.

3.3. Educational and Cultural Context

In Türkiye, compulsory education is based on the K-12 system and is predominantly carried out in public schools. For fourth-grade primary school pupils, the science course is delivered as a compulsory subject for three hours per week, and the instructional process is guided by textbooks and curricula prepared by the Ministry of National Education (MoNE). These curricula are periodically revised in accordance with scientific and pedagogical developments, with the most recent science curriculum updated in 2024. Primary science education in Türkiye is mainly conducted through classroom-based instruction and laboratory work. However, environmental education is not confined to the science curriculum alone; it is also addressed through an interdisciplinary approach in other subjects such as life sciences, social studies, and Turkish language, incorporating themes related to the environment and sustainability. Nevertheless, non-formal learning environments are rarely utilized, and field trips are organized only on a limited basis. At this point, nature-based learning environments such as Nature and Science Schools (NSSs) offer an innovative and alternative approach to environmental citizenship education (ECE). NSSs transcend the boundaries of traditional science instruction by allowing pupils to learn through direct experience and providing an integrated learning process within natural settings. In Türkiye, there is a growing need for in-depth research into the potential contributions of such structured out-of-school learning environments to education.

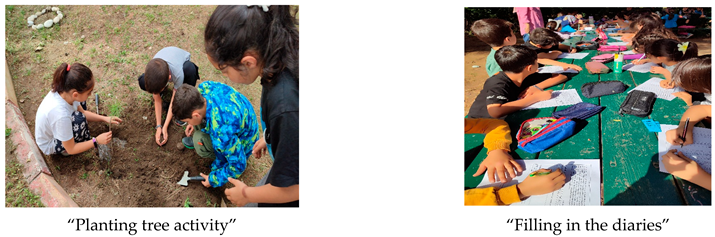

3.4. Researcher Roles

The study was conducted by two academic staff members, one from the Department of Primary Education and the other from the Department of Science Education. Both teach undergraduate and graduate courses on environmental education, as well as qualitative research and research methodology. Ethical approval and institutional permission were obtained, and five classroom teachers volunteered to participate, providing informed consent. Initial interviews were conducted with the teachers in their classrooms to establish rapport. During the implementation of the environmental citizenship education (ECE) program at the Nature and Science School (NSS), the researchers played dual roles as facilitators and observers, guiding the process and monitoring its progress. They also interacted informally with participants during non-instructional times, such as meals, fire-making, and nature walks, to better understand the learning dynamics. At the end of the four-month program, the researchers visited the pupils’ regular schools to observe classroom interactions and gather additional data, offering a deeper understanding of how their NSS experiences influenced their traditional learning environments.

3.5. Research Procedure

The Nature and Science School (NSS) where this study was conducted is a dedicated outdoor education site located in a coastal pine forest ecosystem, which features a rich diversity of endemic plant species. It serves as a natural learning environment where pupils are able to observe, explore, and critically engage with nature through multiple sensory and cognitive pathways. The ecological richness of the site provides opportunities for inquiry-based learning and promotes a direct and immersive relationship with the natural world. As part of the program, pupils visited the NSS once a month to participate in nature-based environmental activities. Each monthly visit was structured around a specific thematic focus, such as environmental citizenship, sustainability, biodiversity, or global climate change. These sessions began with the delivery of theoretical content to establish conceptual foundations and assess pupils’ readiness for the subsequent experiential activities. The same environmental citizenship education (ECE) program was implemented for all participants, regardless of their school of origin. The NSS activities were offered free of charge, with all operational and educational costs covered by the researchers themselves. The content and structure of the ECE program delivered at the NSS are detailed in

Appendix A. The study can be understood as comprising two integrated stages: (1) activities carried out at the NSS and (2) complementary classroom-based activities conducted in pupils’ regular schools. During their visits to the NSS, pupils engaged in full-day sessions, each lasting approximately 6 to 7 h.

3.6. Data Collection Tools

In this study, two qualitative data collection tools were employed: semi-structured interviews and pupil diaries.

3.6.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

To align with the objectives of the study, six semi-structured interview questions were developed for the preliminary phase and were administered to pupils through face-to-face interviews prior to the implementation of the environmental citizenship education (ECE) program. These pre-interviews, conducted in January, aimed to assess participants’ initial levels of awareness and lasted approximately 15 min each. Following the completion of the four-month educational program, post-interviews were conducted in June to capture pupils’ experiences and identify any shifts in their conceptual understanding. The post-interview protocol consisted of ten semi-structured questions and had an average duration of 25 min. Although some items were shared across both pre- and post-interview protocols, four additional questions (items 7, 8, 9, and 10) were incorporated into the final interviews to allow for a more detailed assessment of pupils’ learning outcomes throughout the program. The interview questions were developed by the researchers following a comprehensive review of the relevant literature and were subsequently reviewed and refined by two academic experts specializing in qualitative research. In developing the question set, particular attention was paid to a conceptual framework of environmental citizenship that encompasses key values such as responsibility, justice, sustainability, and participation [

60]. During the design phase, adjustments were made to the sequence of questions, and certain items were revised or removed for clarity and relevance. A pilot implementation was then conducted with two fourth-grade pupils who were not part of the main study sample. Based on the pilot results, it was determined that additional probes were needed for some items (e.g., questions 2 and 3) to enhance depth and clarity. Upon testing the comprehensibility and functionality of the questions through these pilot interviews, the final version of the interview protocol was established.

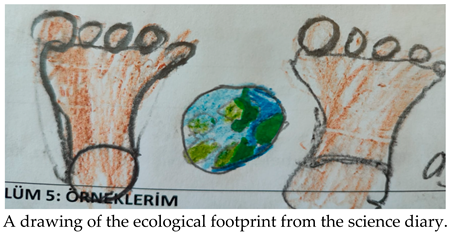

3.6.2. Pupil Diaries

In addition to the data collected at the beginning and end of the study, the inclusion of data gathered throughout the implementation process was considered essential for developing a holistic understanding of the pupils’ experiences. For this reason, pupils were asked to keep diaries during each of their four visits to the Nature and Science School (NSS), expressing their experiences either through written narratives or drawings. These diaries were analyzed as part of the document analysis process. It was emphasized to the pupils that participation was entirely voluntary and that their responses would not be graded. The diaries were prepared by the researchers to cover the full duration of the study and were reviewed by two academic experts specializing in qualitative research. In the second phase, a Turkish language teacher was consulted to evaluate the linguistic clarity and appropriateness of the diary prompts. Based on the expert feedback, the diary was finalized as a four-part template, consisting of the following sections: “What I learned today”, “What I experienced today”, “Questions that came to my mind”, and “My drawings”. A supportive environment was provided at the NSS to ensure that pupils could complete their diaries comfortably and authentically, directly in nature at the end of each visit. No time limits were imposed, and conditions were arranged to allow pupils to express themselves freely and spontaneously.

3.7. Data Analysis and Trustworthiness Procedures

In this study, the data obtained from pupil interviews were analyzed using content analysis, a qualitative method that allows for a systematic and in-depth examination of the data. Content analysis facilitates the identification and organization of codes, themes, and patterns within a coherent framework [

61]. The interview data were first transcribed verbatim by one of the researchers. Subsequently, both researchers independently carried out the coding process. Their respective coding outputs were compared to identify overlaps and discrepancies. Any inconsistencies were discussed in detail in an effort to reach consensus. Intercoder agreement was calculated using the following formula: Reliability = Number of Agreements/(Number of Agreements + Number of Disagreements) [

62]. In the analysis of the pre-interview data, 21 shared codes and 3 disagreements were identified, yielding an agreement rate of 87.5%. A similar procedure was followed for the post-interview data, which resulted in 26 shared codes and 3 unresolved codes, producing an overall intercoder agreement of 89%. To organize the emerging codes and themes into a more systematic and meaningful structure, analysis matrices were developed for both the pre- and post-interview data. In order to better visualize the overall structure of the data set and to illustrate the relationships between the themes, network maps were created using the bubbl.us tool, and these are presented in the findings section.

The second data source, pupil diaries, was also analyzed using content analysis. However, due to the volume of data and publication space limitations, the findings from the diaries are not presented in full in this paper. Instead, selected excerpts and examples were integrated into the text to support and triangulate the interview findings. To enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of the study, several strategies were employed. Multiple researchers were involved in both the development of the data collection tools and the analysis process, and expert opinion was sought at critical stages. Extended engagement with participants was ensured throughout the research period. The research process was documented in detail, and data triangulation was prioritized. Accordingly, interview data were supported by diary entries, and direct quotations were included to reinforce the authenticity of the findings. To protect participant confidentiality, pseudonyms such as S1, S2, etc., were used. Through these procedures, the principles of credibility, transferability, and dependability were upheld throughout the research.

4. Findings

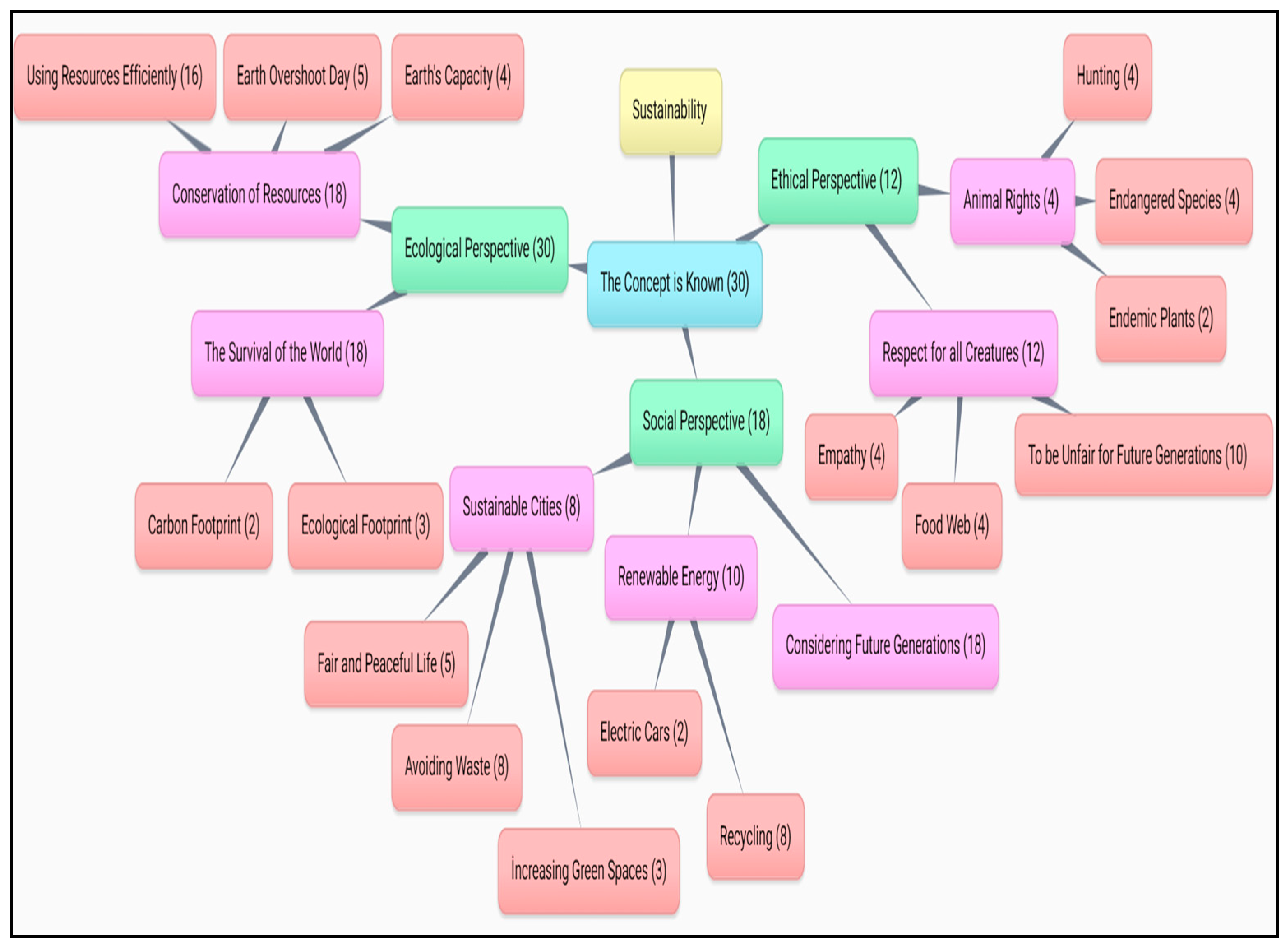

This section presents the findings of the study in alignment with the research question and sub-questions guiding the investigation. Each subsection corresponds to a specific research sub-question and is structured to reflect the thematic outcomes derived from pre- and post-intervention interviews. The comparative content analysis focuses on how primary school pupils’ knowledge, perceptions, and experiences evolved throughout the environmental citizenship education program implemented in the Nature and Science School. To ensure transparency and clarity, the findings are presented thematically and supported by visuals and selected pupil quotes where appropriate. In all visual figures presented in this section (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), the colors are used to represent thematic groupings while the numbers in parentheses indicate the number of pupils who expressed each related concept.

4.1. Development of Pupils’ Perceptions of Environmental Citizenship

Pupils’ perceptions of the concept of environmental citizenship and their self-assessments regarding their roles as environmental citizens were examined comparatively based on the pre- and post-intervention interviews. The findings are presented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Pupils’ perceptions and self-assessments regarding the concept of environmental citizenship before the implementation of the education program.

Figure 2.

Pupils’ perceptions and self-assessments regarding the concept of environmental citizenship before the implementation of the education program.

Figure 3.

Pupils’ perceptions and self-assessments regarding the concept of environmental citizenship after the implementation of the education program.

Figure 3.

Pupils’ perceptions and self-assessments regarding the concept of environmental citizenship after the implementation of the education program.

Based on the pre-intervention interview data, the majority of pupils demonstrated a limited understanding of the concept of environmental citizenship. A total of 13 pupils stated that they had never encountered the term before, while 3 pupils indicated that they possessed only partial knowledge. Fourteen pupils were able to articulate the concept in their own words, predominantly associating environmental citizenship with protecting nature, respecting the environment, being a conscious consumer, and showing sensitivity to environmental issues. In contrast, post-intervention interviews revealed that all pupils were able to define environmental citizenship from multiple perspectives. The theme of sensitivity to environmental problems was associated with the rights and responsibilities dimension of environmental citizenship, while environmental activism was linked to participation in environmental decision-making and contributing to social transformation. Notably, environmental literacy, recognized in the literature as a key component of environmental citizenship, also emerged as a central theme in the post-intervention data. These findings suggest a notable development in pupils’ conceptualizations, indicating a broader and more multidimensional understanding of environmental citizenship over the course of the program. When asked to self-assess based on their own definitions, 18 pupils identified themselves as environmental citizens prior to the intervention, while 12 pupils expressed a partial sense of identification with this role. Following the intervention, 24 pupils reported that they considered themselves environmental citizens, and 6 pupils expressed partial alignment with the identity. The red lines shown in the schematic diagrams indicate expressions that were commonly used by pupils both when defining environmental citizenship and when engaging in self-assessment. A comparison of pre- and post-intervention data reveals a clear evolution in pupils’ perspectives: whereas initially they tended to frame environmental citizenship in terms of individual, eco-friendly behaviors, post-intervention they began to contextualize it within broader frameworks of environmental awareness, volunteerism, environmental literacy, ecological rights, and collective responsibility. In the final round of interviews, pupil responses increasingly included concepts such as environmental advocacy, recycling, waste management, and water conservation. This shift suggests that the nature-based environmental citizenship education program may have supported pupils in broadening their understanding and partially internalizing the identity of an environmental citizen, as reflected in their post-intervention responses. By the end of the program, pupils were no longer defining environmental citizenship merely as a love for nature or a commitment to keeping the environment clean; instead, they described it as active environmental advocacy, raising awareness, and contributing to sustainable social change. These findings suggest a potentially transformative contribution of environmental citizenship education on the development of environmental awareness and responsibility. Furthermore, they highlight the necessity of moving beyond traditional approaches and adopting educational models that encourage pupils’ active engagement and critical participation in environmental issues. This shift is illustrated in participant S28’s reflections:

“I have never heard of the term environmental citizenship, but I can make an educated guess. It’s about protecting the environment and not littering... I see myself as partially an environmental citizen. I try to be careful not to throw rubbish on the ground.” (S28, Pre-interview)

“Environmental citizenship means our responsibilities toward the environment. It means volunteering for environmental causes. It means being environmentally literate. Environmental citizenship is about showing sensitivity to zero waste and using resources efficiently. It means being a conscious consumer... Of course, I am an environmental citizen. First of all, I am a conscious consumer. I pay attention to water conservation. I am a volunteer for TEMA (The Turkish Foundation for Combating Soil Erosion). For example, I felt deeply saddened when I saw a tree being cut down to build a road, and I spoke out against it.” (S28, Post-interview)

Participant S19’s diary provides further insight into this shift:

“To be an ecological citizen, one must be a volunteer and possess environmental literacy. You should be an environmental advocate. The biosphere II is fascinating, finite, and it’s impossible to create another Earth. I also learned that sand lilies are endemic plants. I learned all of this today.” (Excerpt from the diary of S19)

4.2. Development of Pupils’ Awareness of Environmental Problems and the Global Climate Crisis

Pupils’ awareness of environmental problems and the global climate crisis was examined through a comparative analysis of the pre- and post-intervention interview data. The findings are illustrated in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Pupils’ awareness of environmental problems and the global climate crisis before the environmental citizenship education program.

Figure 4.

Pupils’ awareness of environmental problems and the global climate crisis before the environmental citizenship education program.

Figure 5.

Pupils’ awareness of environmental problems and the global climate crisis after the environmental citizenship education program.

Figure 5.

Pupils’ awareness of environmental problems and the global climate crisis after the environmental citizenship education program.

The findings from the pre-intervention interviews revealed that pupils’ awareness of environmental issues was largely superficial and based primarily on observational experiences. Pupils tended to focus on local, everyday concerns such as environmental pollution, littering, water waste, and protecting nature. However, their knowledge regarding global environmental problems and their long-term consequences was found to be limited. In contrast, the post-intervention data demonstrated a marked increase in pupils’ awareness of environmental issues. Pupils were able to identify and articulate environmental problems such as air, soil, and water pollution, drought, desertification, deforestation, and marine pollution with greater clarity and consciousness. Furthermore, they addressed these problems not only at the individual level but also from societal and global perspectives. Concepts such as Earth Overshoot Day, ecological footprint, sustainability, ignorance, and marine mucilage (or “sea snot”) were mentioned, indicating a more sophisticated understanding. In particular, the increased awareness regarding the global climate crisis was noteworthy. While many pupils struggled to define or explain climate change during the pre-interviews, with some even admitting to having no knowledge of the subject, post-interviews revealed that they could explain key phenomena such as seasonal shifts, extreme temperature increases, melting glaciers, loss of biodiversity, and rising sea levels with greater accuracy. Statements such as “I don’t know much about climate change” or “I’ve heard of it a little”, which were common in the pre-interviews, were replaced in the post-interviews with more elaborate and scientifically grounded explanations. Moreover, rather than describing environmental issues only at the observational level, pupils began to critically examine individual and societal topics, such as obesity, war, and animal testing, through an environmental lens. The following quote from participant S13 provides a compelling example of this transformation.

“Cutting down trees and forest fires can be considered environmental problems. I also think that not paying attention to recycling is an issue. I don’t know what the term global climate crisis means, but the word crisis makes me think it’s something bad.” (S13, Pre-interview)

“In general, environmental pollution, water pollution, marine pollution, the depletion of the ozone layer, the global climate crisis, extreme heat and resulting drought, space pollution, light pollution, deforestation and tree cutting, and the killing of animals; which they call hunting, are all environmental problems. Even the use of animals in laboratory experiments is, in my opinion, an environmental issue, and it really hurts me. Because every living being has the right to life. Also, wastefulness and a lack of attention to sustainability are serious problems as well.” (S13, Post-interview)

Another example supporting the interview findings is drawn from the diary completed by participant S7.

“Today, I learned about the global climate crisis and related concepts (ozone layer, greenhouse gases). Only 2% of the water on Earth is freshwater, and there is a water shortage. The sea level is also rising.” (Excerpt from the diary of S7)

4.3. Development of Pupils’ Perceptions of the Concept of Sustainability

Pupils’ perceptions of the concept of sustainability were examined through a comparative analysis of the pre- and post-intervention interview data. The findings are presented in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Pupils’ perceptions of the concept of sustainability before the environmental citizenship education program.

Figure 6.

Pupils’ perceptions of the concept of sustainability before the environmental citizenship education program.

Figure 7.

Pupils’ perceptions of the concept of sustainability after the environmental citizenship education program.

Figure 7.

Pupils’ perceptions of the concept of sustainability after the environmental citizenship education program.

The pre-intervention interview results revealed that the majority of pupils had not heard of the concept of sustainability and were unable to define it. Among those who could define it, most associated sustainability with individual saving habits, indicating a limited understanding of the environmental, economic, and social dimensions of the concept. Some pupils framed sustainability in terms of conserving natural resources, water, and energy. In contrast, post-intervention results demonstrated that pupils began to approach the concept of sustainability in a broader and more multidimensional framework. Pupils who had previously explained sustainability solely in terms of individual saving and environmental conservation were, after the educational process, able to consider sustainability from environmental, ethical, and social perspectives. In the interviews, pupils explored the concept of sustainability in a comprehensive manner, discussing topics ranging from animal rights and ecosystem balance to the use of renewable energy and eco-friendly urbanization. Notably, the Native American proverb “We do not inherit the Earth from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children” was frequently mentioned during the interviews. However, this meaningful saying could not be included in the visuals as a code. Nonetheless, expressions such as “viewing the Earth as a trust”, “thinking about future generations”, and “consciously consuming resources” were often articulated, suggesting that pupils may have developed a deeper understanding of sustainability. The following is an excerpt from S9 regarding this topic:

“I don’t know what sustainability means, but I would guess it’s about the continuity of life. It might also be about the future of the Earth.” (S9, Pre-interview)

“Sustainability, in the simplest terms, means leaving the Earth in a beautiful condition for our grandchildren. The Native American proverb comes to mind: We must protect the Earth and leave it in good condition for future generations. Our grandparents left a beautiful world for their children, but our fathers did not leave us the same beautiful world, and our elders owe us a beautiful world. Sustainability is a very broad term that encompasses generations, the environment, and the Earth. Sustainability includes many things, from marine pollution to resource conservation. Even composting is related to sustainability.” (S9, Post-interview)

Further support for the interview findings is drawn from the science diary completed by participant S9.

Additionally, pupils have developed more informed and systematic solutions, such as promoting renewable energy use, protecting green spaces, encouraging recycling, and implementing ecological farming practices, all aligned with sustainable development goals. These suggestions indicate that pupils began to perceive sustainability not only as an individual behavioral issue but also as a societal and political concern. This highlights how environmental citizenship education fosters pupils’ ability to think multidimensionally. The following is an excerpt from S19 regarding this issue:

“I would join organizations like TEMA (The Turkish Foundation for Combating Soil Erosion), and work for the environment. We would carry out projects together with scientists. The presidents of countries should also make agreements, and the parliament should pass laws to protect the environment.” (S19, Post-interview).

Another example supporting the interview findings is drawn from the science diary completed by participant S69.

“I learned about ecological footprint, carbon footprint, and Earth Overshoot Day. I learned that waste I produce in Türkiye can affect the entire world. Excessive electricity consumption here can impact the polar bears in the glaciers.” (Excerpt from the science diary of S69)

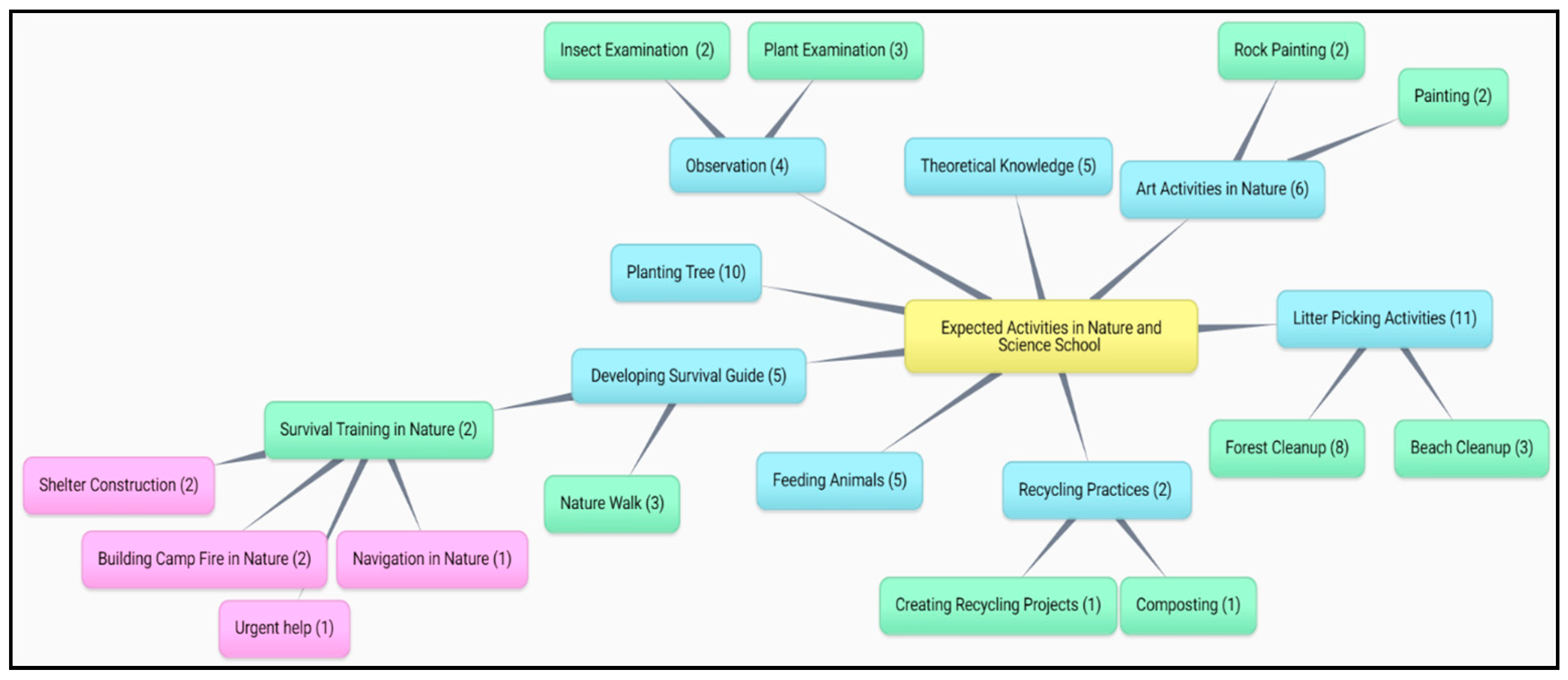

4.4. Pupils’ Expectations, Views, and Experiences Regarding the Environmental Citizenship Education Program Implemented at the Nature and Science School

Pupils’ expectations regarding the environmental citizenship education program implemented at the NSS were evaluated during the pre-intervention interviews, while their experiences were assessed in the post-intervention interviews. The pupils’ expectations are presented in

Figure 8, while their experiences are shown in

Figure 9.

The pre-intervention interview results indicated that pupils’ expectations for the ECE program were primarily shaped around activities involving interaction with nature, observational studies, and environmental protection practices. Pupils expressed a strong interest in engaging in nature observation, participating in environmental clean-up activities, and becoming involved in recycling processes. Additionally, they requested more theoretical knowledge on environmental issues.

Figure 8.

Pupils’ expectations before the environmental citizenship education program.

Figure 8.

Pupils’ expectations before the environmental citizenship education program.

Figure 9.

Pupils’ views and experiences after the environmental citizenship education program.

Figure 9.

Pupils’ views and experiences after the environmental citizenship education program.

While pupils acknowledged that the ECE program at the Nature and Science School (NSS) was effective in raising environmental awareness, they also expressed the need for more hands-on activities and greater opportunities to spend time immersed in nature. Requests for increased integration of environmental clean-up activities, recycling practices, nature observation experiences, animal care activities, and theoretical knowledge into the educational process suggest that pupils were expecting a more comprehensive learning and experiential process in the environmental citizenship program. S6 expressed their expectations with the following statement:

“At NSS, I hope we can plant trees, do environmental clean-up at the beach or in the forest. I would also like there to be a focus on recycling and waste reduction.” (S6, Pre-interview)

The post-intervention interview results revealed that pupils viewed the ECE program at the NSS not merely as an observational experience but as a process that required active participation. The findings, categorized under pupils’ views, experiences, and suggestions, showed overwhelmingly positive outcomes. Pupils did not express notable negative feedback during the interviews, and the process was described as informative and engaging. Pupils reported that their environmental awareness had increased, and they realized that environmental citizenship requires not only individual responsibility but also social awareness and action. Focusing on the experiences dimension, it was found that pupils had positive experiences, and the activities conducted were generally well-liked, with a variety of preferences noted. The fact that some activities did not stand out more than others was interpreted as a positive finding, meaning that all activities within the educational content were regarded as a “favorite” by the pupils. In this regard, it was concluded that the environmental citizenship education provided an effective curriculum that resonated with pupils. Regarding suggestions, the vast majority of pupils indicated that the environmental citizenship education program did not require any changes and that the activities conducted were sufficient. However, a few pupils suggested incorporating activities such as beach clean-ups and stone painting into the program. The following is an excerpt from S6 regarding their views and experiences with environmental citizenship education:

“I learned new concepts at NSS. For example, I didn’t know about Earth Overshoot Day, ecological footprint, the global climate crisis, or endemic plants. You taught them really well. These concepts made us more conscious and helped us become environmental advocates. We did a lot of activities. For example, the Six Thinking Hats technique, where I learned my friends’ ideas, and the ecosystem game were some of my favorite activities. The Biosphere II video in the theoretical section was very impressive. I don’t think there was anything missing in the training; there was more than enough. I would like this to happen again next year.” (S6, Post-interview)

Another example supporting the interview findings is drawn from the science diary completed by participant S43.

“I learned from the Biosphere that there is no other Earth.” (Excerpt from the science diary of S43)

4.5. Summary of Findings

This study examined the impact of the ECE program implemented at the NSS on pupils, revealing the transformations in their perceptions of environmental citizenship, awareness of environmental problems, understanding of sustainability, and tendency to assume environmental responsibility. The pre-intervention interview results showed that pupils primarily defined environmental citizenship through individual actions (such as cleaning, recycling, and protecting nature). In contrast, the post-intervention results indicate that the concept began to be associated with societal participation, environmental advocacy, and sustainable development goals. Pupils significantly increased their awareness of global environmental issues, becoming more conscious particularly of the climate crisis, biodiversity loss, and the disruption of ecological balance. Furthermore, they exhibited a stronger inclination towards social responsibilities, including supporting recycling projects, participating in non-governmental organizations (NGOs), spreading environmental awareness through media, and actively engaging in environmental campaigns. The ECE program at NSS helped pupils to transition from being mere observers of environmental problems to becoming active environmental citizens who generate solutions and embrace sustainable living practices. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution, as the absence of a control group and long-term follow-up limits the ability to attribute the observed changes solely to the intervention.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we examined the experiences of pupils during the ECE program implemented at the NSS. We analyzed how pupils made sense of this educational process, how they expressed their views on the concept of environmental citizenship, and how environmental awareness developed throughout the program. Based on the research questions, we discussed the findings obtained from the analysis of pre- and post-intervention interview data in the context of the concept of environmental citizenship, awareness of environmental problems and the global climate crisis, perceptions of sustainability, and pupils’ views on the ECE program at the NSS.

5.1. Shaping of Pupils’ Knowledge and Perceptions of the Concept of Environmental Citizenship

This study reveals a significant shift in pupils’ understanding of environmental citizenship. In the pre-intervention interviews, pupils primarily viewed the concept as limited to individual actions, such as recycling, cleaning, and conserving nature. However, after the educational process, pupils expanded their perspectives to include social and political dimensions. There was a notable increase in focus on collective responsibility, sustainable lifestyles, and environmental justice. These findings suggest that environmental citizenship evolves from individual awareness to social responsibility. The existing literature supports that environmental citizenship extends beyond individual eco-friendly behaviors, encompassing political participation and the adoption of sustainable lifestyles [

41]. It also emphasizes the need for a broader awareness that supports sustainable living [

14]. This study confirms that while pupils initially defined environmental citizenship in individual terms, they later integrated broader social and global perspectives, highlighting the vital role of environmental citizenship education in deepening pupils’ conceptual understanding.

The change observed in pupils’ perceptions of environmental citizenship aligns with studies highlighting the critical role of environmental education in developing individuals’ ecological awareness. It has been stressed that environmental citizenship is not limited to individual behaviors, but is also shaped by social awareness and collective consciousness [

63]. Similarly, it has been demonstrated that teachers’ attitudes towards environmental citizenship education guide pupils’ processes of developing environmental consciousness [

31]. In this context, the findings of this study also show that the nature-based educational process, guided by teachers, contributed to pupils developing a more holistic perspective on the concept of environmental citizenship. Furthermore, gaining awareness of the social justice and equality dimensions of environmental citizenship is another notable area of development. It has been argued that environmental citizenship should not be limited to ecological sustainability but should also encompass perspectives on social justice and societal equality [

64,

65]. The findings of our study show that pupils began to approach the concept of environmental citizenship not only as an individual practice but also within the framework of social cooperation and global responsibility. This study contributes significantly to the literature by showing that the environmental citizenship education program at NSS transformed pupils’ perceptions of environmental citizenship from individual awareness to collective consciousness and social responsibility.

5.2. Shaping of Pupils’ Awareness of Environmental Problems and the Global Climate Crisis

This study illustrates how pupils’ awareness of environmental problems and the global climate crisis was shaped through the environmental citizenship education (ECE) process at the Nature and Science School (NSS). The pre-intervention interviews revealed that pupils primarily perceived environmental issues as local and individual concerns, focusing on everyday problems like littering, water wastage, and air pollution. However, the post-intervention results showed a shift, with pupils beginning to approach environmental challenges from a global perspective. These findings align with the existing literature that highlights the positive influence of nature-based and experiential learning on environmental awareness [

66]. Early exposure to nature increases the likelihood of developing environmental citizenship awareness in adulthood [

24]. Therefore, it is believed that the NSS activities were instrumental in enhancing pupils’ environmental awareness through direct interaction with nature.

The role of experiential learning in improving environmental problem-solving skills is also emphasized in various studies. When environmental education incorporates experiential methods, pupils tend to adopt sustainable thinking patterns and develop problem-solving skills [

67]. In this study, while pupils initially focused on protecting the environment at an individual level, they later began to propose solutions for collective environmental actions. Garden-based learning practices also foster critical thinking about ecological issues like agriculture and food consumption, strengthening sustainable citizenship skills [

68]. Similarly, this study observed that pupils not only participated in individual eco-friendly actions but also developed broader proposals, including recycling projects, reducing carbon footprints, using sustainable energy, and engaging in environmental policies.

The increase in pupils’ awareness of global environmental problems is significant in this context. Environmental service learning experiences help pupils to approach environmental issues not only from an individual perspective but also from a societal and global context, thereby fostering the development of critical thinking skills [

69]. In this study, pupils were observed to make more informed comments on topics such as the global climate crisis, biodiversity loss, and overconsumption. Overall, these findings demonstrate that experiential environmental citizenship education is an effective method for enhancing pupils’ environmental awareness and guiding them to critically assess global environmental issues.

5.3. Shaping of Pupils’ Perceptions of the Concept of Sustainability

Pupils’ perceptions of sustainability shifted from a focus on individual savings and the protection of natural resources to a broader perspective that incorporated global environmental policies, social justice, and economic sustainability by the end of the educational process. This shift aligns with findings that emphasize the integration of sustainable development goals in education, enhancing individuals’ ability to consider environmental, social, and economic aspects collectively [

70]. Additionally, the role of ethical awareness and self-reflection in developing sustainable consumption consciousness is also underscored [

71]. Pupils’ transition from viewing sustainability solely as an individual responsibility to recognizing its societal and ecological dimensions demonstrates a deeper understanding of sustainable development and environmental citizenship. This transformation supports the findings that sustainability education should go beyond individual awareness and foster societal change [

72]. Our study indicates that pupils did not restrict sustainability to environmental actions but developed a conscious attitude aligned with the sustainable development goals.

The influence of experiential learning on pupils’ sustainability awareness is widely discussed in the literature. The value of integrating sustainability topics into lessons, enabling pupils to engage with the concept more meaningfully, is emphasized in recent research [

73]. Our findings show that the environmental citizenship education at the NSS contributed to pupils’ ability to assess sustainability not only through individual practices but also at the collective and political levels. By the end of the educational process, pupils exhibited a more conscious and active attitude toward sustainability, which is consistent with findings indicating that environmental education programs lead to changes in individuals’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors [

74]. Initially, pupils viewed sustainability through individual consumption and savings, but by the end of the program, they began considering it in broader contexts, including environmental policies, social justice, and ecosystem balance.

Moreover, the development of more conscious ideas among pupils regarding the application of sustainability in daily life during the environmental citizenship education process corresponds with findings that highlight the effectiveness of introducing sustainability awareness through play and interactive learning at early ages [

75]. Our study shows that direct interaction with nature, observation, and active participation in sustainable practices significantly contributed to the development of pupils’ perceptions of sustainability. This research highlights that environmental citizenship education is effective in raising sustainability awareness and helps pupils to approach sustainability not only from an individual perspective but also at the global and societal levels. Aligning environmental citizenship education with sustainable development goals and providing more experiential learning opportunities are essential for ensuring lasting sustainability awareness.

5.4. Pupils’ Experiences and Views on the Environmental Citizenship Education Program Implemented at the Nature and Science School

Our findings indicate that pupils experienced the environmental citizenship education (ECE) program at the Nature and Science School (NSS) as a transformative process that increased their environmental awareness and encouraged active participation. Pre-intervention interviews revealed that pupils initially viewed environmental citizenship as limited to individual responsibilities. However, post-intervention interviews showed that this perception expanded to include collective environmental actions and sustainable societal participation. These findings align with the literature, which emphasizes the role of nature-based education in enhancing environmental awareness. Environmental citizenship extends beyond knowledge, encouraging active participation in addressing environmental issues [

76]. Similarly, it has been emphasized that environmental citizenship education (ECE) fosters ecological responsibility and supports societal sustainability [

37]. Structured environmental citizenship education at the primary school level has also been shown to significantly transform pupils’ environmental actions [

77].

Our study shows that NSS pupils developed problem-solving skills related to environmental issues. This aligns with findings showing that experiential environmental education encourages pupils to make environmentally conscious decisions [

78]. Our study observed that pupils’ environmental awareness shifted from individual concerns to actively seeking solutions for societal environmental problems. Pupils’ experiences in the program were closely linked to the quality and effectiveness of the education. Experiential learning and problem-solving activities have been shown to enhance pupils’ capacity to take initiative as environmental citizens [

39]. It has also been stated that environmental citizenship education (ECE) should support the transition from individual awareness to collective environmental action [

79]. Similarly, our study shows that while pupils initially focused on individual environmental awareness, by the end of the program, they became more focused on developing sustainable environmental solutions.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the environmental citizenship education (ECE) program implemented at the Nature and Science School (NSS) effectively supported pupils’ environmental awareness and encouraged their active engagement in sustainable actions. By the end of the program, pupils had not only developed individual awareness but also expressed an increasing orientation toward collective environmental responsibility. Therefore, it is essential that environmental citizenship education includes more experiential learning opportunities to foster individuals who are motivated and empowered to develop innovative, long-term solutions for addressing complex environmental challenges in both local and global contexts.

This study was conducted in a small-scale and supportive implementation context, where the positive engagement of participants and institutions contributed to the program’s effectiveness. As sample sizes increase in future implementations, new challenges may emerge due to the diversity of participant profiles and contextual variables. However, broader participation from teachers and pupils could facilitate the wider dissemination of environmental citizenship education and enhance the generalizability of its outcomes. Furthermore, when similar programs are implemented in different educational settings, the unique contextual constraints of each school, such as transportation, permission procedures, and time limitations, should be carefully considered. For this reason, it is crucial that educators and researchers adapt the design of nature-based education programs to their institutional conditions to ensure both sustainability and effectiveness.

Nevertheless, the findings must be interpreted with caution due to certain methodological limitations. The absence of a control group restricts the ability to directly attribute the observed changes solely to the intervention. While systematic coding procedures and data triangulation strategies were employed to strengthen the trustworthiness of the analysis, the novelty of the educational setting may have also contributed to pupils’ observed transformations. Furthermore, no contradictory responses were identified during the analysis. The data showed a consistent positive development across participants. While this coherence supports the internal validity of the study, it may also reflect the highly immersive and supportive nature of the educational environment. Therefore, future studies implemented in more diverse and less structured contexts could help to test the replicability of these findings and reveal potential variations in pupils’ experiences. Future research should consider incorporating longitudinal designs and the inclusion of control or comparison groups to enhance the validity and reliability of the findings.

6. Suggestions

This study highlights the effectiveness of environmental citizenship education in enhancing pupils’ awareness of environmental issues and the global climate crisis, while enabling them to conceptualize environmental citizenship within a broader, multidimensional framework. In this regard, environmental citizenship education should be designed to go beyond individual awareness, encouraging pupils to participate in societal initiatives and the development of sustainable environmental solutions. To help pupils assess environmental issues from both local and global perspectives, educational programs should integrate more interdisciplinary approaches and promote critical thinking. Additionally, environmental citizenship education should not only focus on eco-friendly individual behaviors but also link the concept to environmental policies, ecological rights, and sustainable development goals. To foster pupils’ involvement in collective environmental movements, education should become more inclusive by extending beyond individual awareness. Topics like recycling projects, reducing carbon footprints, sustainable consumption habits, and participation in environmental policies should be supported through field studies and workshops that allow pupils to actively engage. To raise awareness about issues like climate change, environmental justice, and sustainable natural resource use, it is crucial to incorporate current environmental policies and global sustainability discussions into the curriculum. Furthermore, collaborations with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), local authorities, and environmental projects should be established to encourage pupils’ active participation in environmental decision-making processes.

In future research, an action research approach could be adopted to iteratively improve environmental citizenship education programs by incorporating continuous feedback from teachers, students, and community stakeholders. Such a model would allow for more responsive and context-specific program development over time.

Moreover, future research should not only rely on qualitative methods but also incorporate mixed-method designs supported by quantitative data collection tools, which would contribute to more objectively tracking pupils’ development regarding environmental citizenship, sustainability, and environmental issues. In addition, future studies could include control groups to provide a more rigorous evaluation of the program’s impact, offering comparative insights between participants and non-participants.

This would allow the transformation processes of participants to be revealed both in depth and in a more generalizable manner. Such studies, which evaluate the impact of educational practices from both quantitative and qualitative perspectives, will provide stronger and more representative evidence in the field.