1. Introduction

Over the past four decades, China’s rapid economic growth has demonstrated that openness to global markets is a fundamental driver of sustained economic development. As part of its broader economic liberalization strategy, China has gradually expanded its financial market access to international investors. A key milestone in this process was the introduction of the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect in 2014 and the Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect in 2016. These initiatives have facilitated cross-border capital flows, allowing mainland Chinese and Hong Kong investors to trade eligible stocks in each other’s markets through their local brokerage firms. By reducing market segmentation, enhancing financial integration, and improving capital allocation efficiency, these policies mark a significant step toward financial market liberalization and play a crucial role in supporting China’s transition to high-quality economic growth.

With the growing global focus on sustainable development, green growth has become a key aspect of high-quality economic progress. Unlike conventional growth models that rely heavily on resource consumption, green development prioritizes environmental sustainability, technological innovation, and energy efficiency. From an economic perspective, green production represents a structural transformation in which firms shift from traditional, resource-intensive production models toward low-carbon, environmentally friendly practices. This shift reduces environmental impact while strengthening long-term corporate competitiveness. Given the strategic importance of green development, identifying the economic and financial mechanisms that support corporate green transformation has become a pressing research agenda.

While financial market liberalization is widely recognized for its role in improving capital allocation and corporate governance, its implications for corporate green development remain underexplored. The impact of capital market openness on corporate green total factor productivity has been largely overlooked in existing research. This study aims to fill this gap by exploring key research questions. First, does capital market openness promote corporate GTFP? Second, what are the underlying mechanisms through which financial market liberalization affects corporate green productivity? Third, do these effects exhibit heterogeneity across firms with different characteristics? Finally, how can financial market reforms be optimized to facilitate corporate green transformation? By addressing these questions, this study offers fresh empirical insights into the link between financial liberalization and corporate sustainability, offering insights into how capital market openness can serve as a policy instrument for promoting green economic development.

This paper makes three primary contributions. First, this study expands research on how non-environmental policies affect corporate green development. While most studies focus on direct environmental measures like green credit, regulations, and low-carbon initiatives, financial policies receive less attention. By analyzing capital market openness, this study highlights additional policy tools that drive corporate green growth. Second, it enhances research on the comprehensive evaluation of corporate economic–environmental performance. The previous literature has largely concentrated on single-dimensional indicators such as green innovation patents, ESG ratings, or pollution emissions, lacking an integrated assessment of both economic benefits and environmental impacts. By investigating firms’ GTFP, this study provides a more holistic perspective for evaluating corporate green development. Finally, this paper holds important policy implications for global carbon reduction efforts. In the context of international climate commitments, nations worldwide are striving to accelerate green technology adoption and promote sustainable development. Multilateral agreements, such as the Paris Agreement, emphasize the need for financial market reforms to support low-carbon transitions. Additionally, global economic integration calls for greater synergy between domestic and international markets to enhance resource allocation for green innovation. This study highlights how capital market openness contributes to corporate carbon efficiency through both financial incentives and technological advancements. By shedding light on these mechanisms, it offers valuable insights for policymakers seeking to align financial liberalization with global carbon reduction goals.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Literature Review

Corporate green total factor productivity (GTFP), which provides a comprehensive measure of not only traditional factor inputs and economic outputs but also incorporates key dimensions such as energy consumption and environmental impact, is selected as the primary object of study in this paper. Existing research on GTFP has predominantly focused on the regional level, with relatively limited exploration at the corporate level. The main areas of focus include trends in GTFP [

1,

2], green finance [

3,

4,

5], and the impacts of environmental policies, such as environmental taxes and regulations [

6,

7]. However, the literature that directly examines how capital market liberalization promotes corporate green development is scarce. Related studies have mainly centered on its effects on corporate green technology innovation [

8,

9,

10] and ESG performance [

11]. This paper aims to fill this gap by conducting an in-depth analysis of the multifaceted internal mechanisms through which capital market liberalization influences corporate green development. It further discusses aspects less explored in the previous literature, such as corporate green information disclosure, green responsibility commitment, executive green experience, and the entry of green investors, thereby offering new theoretical insights and empirical evidence on how China’s market-oriented reforms can empower high-quality economic and green development.

2.2. Theoretical Framework: Hard and Soft Strength in Corporate Development

Enhancing green “hard strength” to increase desirable outputs and strengthening green “soft strength” to reduce undesirable outputs are two indispensable and complementary facets of improving green total factor productivity. Hard strength is primarily manifested through the technological progress effect, which pushes the production possibility frontier outward by enhancing green financial capabilities and fostering technological innovation. Soft strength is reflected in the improvement of green resource allocation efficiency, which moves a firm’s actual production status closer to the optimal production frontier by enhancing its commitment to green obligations and its green management capabilities [

12,

13]. Based on this analytical framework, this paper delves into how capital market liberalization influences corporate GTFP by acting on both green “hard strength” and “soft strength”.

2.3. Enhancing Green Hard Strength: Alleviating Financing Constraints and Promoting Green Technological Innovation

Capital market liberalization can enhance a firm’s green “hard strength” and subsequently boost its GTFP by alleviating financing constraints for green projects and promoting green technological innovation. Capital market liberalization introduces foreign institutional investors, providing firms with broader financing channels and capital sources, thereby mitigating their financing constraints [

14,

15,

16]. Green innovation is characterized by high complexity, long R&D cycles, and significant strategic risks. Although it can achieve a “win-win” in both economic and environmental performance in the long run, firms under financing constraints often tend to avoid green innovation projects. Capital market liberalization introduces low-cost green capital and more mature green capital market mechanisms. Notably, green investors among foreign stakeholders often demand lower-risk premiums for green projects. This enhanced access to financing encourages firms to undertake substantive green innovation rather than adopting conservative avoidance strategies [

17,

18]. Furthermore, the platform effect of international capital markets facilitates firms’ R&D in green technologies. Foreign institutional investors often possess extensive experience in green investment and the capacity for technology transfer, helping firms acquire green technology solutions and opportunities for international technological collaboration through shareholder proposals, strategic partnerships, or cross-border mergers and acquisitions [

19].

2.4. Enhancing Green Soft Strength: Strengthening Green Responsibility Reporting and Information Disclosure

First, at the level of strengthening corporate green responsibility. Capital market liberalization introduces foreign investors from more mature markets, where regulatory and information disclosure systems are more sophisticated. These investors place a high value on the quality and transparency of information disclosure, considering it a key basis for investment decisions [

20]. Their entry, therefore, pressures firms to improve their information environment. More importantly, many foreign investors adhere to strong green and ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) investment philosophies, paying particular attention to non-financial information regarding a firm’s environmental responsibility and ESG performance. This preference directly incentivizes firms to more actively fulfill their green responsibilities, issue high-quality social responsibility reports, and increase their green information disclosure [

21,

22]. Furthermore, foreign investors typically possess superior information-gathering and analytical capabilities, with strong motivation and advantages in experience, technology, and human resources to collect market information, analyze corporate green responsibility reports, and assess a firm’s sustainability [

23]. According to signaling theory, firms are also motivated to undertake greater green responsibilities and disclose more green information to attract these foreign investors [

24].

Second, at the level of enhancing corporate green management. The influence of foreign investors is realized through two primary channels. The first is through active governance via “voice” (or “voting with hands”). Foreign institutional investors can directly participate in corporate governance by leveraging their board representation, voting rights, and right to submit shareholder proposals. For instance, they can convey advanced green development concepts to management, advocate for the hiring of executives with green professional backgrounds, and enhance the green awareness and experience of the decision-making body. They can also use their voting and proposal rights to compel the firm to improve its internal environmental governance structure, which directly enhances its green “soft strength” [

25]. The second channel is by creating market discipline through the “threat of exit” (or “voting with feet”). Foreign investors from mature markets often follow the principles of responsible investment, and their decisions to invest or divest carry strong market signals. To avoid the negative chain reactions triggered by the withdrawal of key investors, firms are compelled, either passively or proactively, to strengthen their corporate green governance, thus achieving self-discipline and improvement at the governance level [

26].

2.5. Research Hypothesis

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. Capital market openness enhances corporate green total factor productivity (GTFP).

This hypothesis will be empirically tested using panel data from Chinese listed firms and a multi-period difference-in-differences (DID) model. The next section details the sample selection criteria and econometric model specifications.

3. Sample Construction and Empirical Model

3.1. Data Sources and Sample Construction

Major economic events, such as the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, caused severe short-term ‘abnormal’ fluctuations in industrial firms’ operations, energy consumption, and emissions data by triggering supply chain disruptions, demand volatility, and atypical production adjustments. This ‘noise’, primarily driven by external shocks, if included in the analysis, would severely interfere with the accurate assessment of the ‘Stock Connect’ policy’s impact on corporate green total factor productivity (GTFP), making it difficult to isolate the true policy effect. To ensure robust conclusions and a pure policy evaluation, this study selected a period of relative stability with minimal exposure to such large-scale systemic shocks. Specifically, we excluded the most impactful phases of the aforementioned major crises. Considering the ‘Stock Connect’ policy’s average implementation around 2015, and in conjunction with the availability and consistency of relevant industrial firm data (especially early green indicators and emissions data), we ultimately selected annual data from 2012 to 2019 as our research sample. This window period provides a pre- and post-policy implementation comparison and also maximally avoids the extreme influence of major external shocks on firm behavior and data quality. Primary corporate information is sourced from the CSMAR and Wind databases. Pollutant emission data for listed companies are obtained from various statistical sources, including the China Energy Statistical Yearbook, the China Industrial Economy Statistical Yearbook, and the China Environmental Statistical Yearbook. Additionally, information regarding firms’ green behavior is compiled from publicly available corporate reports.

The process of selecting the sample is structured as follows: First, companies operating belonging to the financial and insurance domains, along with those classified as ST and *ST, are excluded. Firms where essential variables contain incomplete data are also removed. To uphold the reliability of the policy impact assessment, any firms that initially participated in the “Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect” or “Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect” but later exited are omitted. Additionally, continuous variables undergo a winsorization, trimming extreme values at the 1st and 99th percentiles, to control for outliers. After completing the aforementioned steps, the final panel dataset consists of 7551 observations.

3.2. Measurement of Corporate Green Total Factor Productivity

The primary dependent variable in this study is corporate green total factor productivity (GTFP). The following subsections will elaborate on the selection of the calculation method, model specification, and the computation process.

For the calculation method, we opt for the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)-based DDF-SBM-GML model. This model is chosen for its ability to meticulously depict the complex, non-proportional resource adjustment behaviors of firms under multiple economic and environmental objectives, making it more suitable for assessing corporate-level green total factor productivity. DEA-based methods are commonly used for calculating production efficiency. Traditional DEA directional distance functions (DDFs) suffer from issues such as radiality, angularity, overestimation of efficiency, and the inability to simultaneously make non-proportional adjustments to both production and input efficiencies. Consequently, previous research has often employed improved Slack-Based Measure (SBM) models and the Global Malmquist–Luenberger (GML) index (SBM-GML) to calculate green total factor productivity [

5]. Although the SBM model improves upon traditional DEA through its non-radial and non-angular characteristics, its guidance towards the optimal improvement direction in complex green production remains somewhat insufficient, and it may not completely eliminate potential biases in efficiency assessments. Therefore, drawing on recent advancements, this study integrates the concept of the directional distance function (DDF) within the SBM framework and combines it with the GML index to construct the DDF-SBM-GML method [

22]. The core idea is to utilize the explicit directional vector provided by the DDF to enhance the SBM’s path guidance and efficiency identification accuracy in multi-objective optimization (such as increasing desirable outputs and reducing undesirable outputs), subsequently using the GML index for the dynamic measurement of GTFP.

In terms of model specification, the setup of the SBM model primarily references the methodologies of Lee and Lee [

4]. The input variables for the model are defined as capital, labor, and intermediate inputs. The desirable output is total assets, and the undesirable output variable selected is total energy consumption. The directional vector for the DDF is specified following the research of Fukuyama and Weber [

27], defining the directional vector as the difference between the maximum and minimum values of each variable. This approach mitigates computational overload caused by inconsistencies in the units of measurement of the data itself, while also ensuring that the green total factor productivity values remain between 0 and 1.

3.3. Econometric Model Specification

The “Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect” and “Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect” policies provide a quasi-natural experimental setting. This study establishes treatment and control groups based on differences in the timing of policy implementation. Given that the “Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect” was introduced before the “Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect”, and both policies followed a phased approach to stock inclusion, a multi-period difference-in-differences (DID) model is employed to evaluate the impact of capital market openness on firms’ green total factor productivity (GTFP):

where the subscripts i, j, and t represent firms, industries, and years, respectively. The dependent variable GTFP

i,t denotes the green total factor productivity of firm i in year t. The primary explanatory variable HSGT

i,t is a binary indicator reflecting the implementation of the SHSC and SZSC policies. Specifically, if firm i is included in the SHSC or SZSC stock list in year

t or later, the variable is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it remains 0. The vector X

i,t represents a collection of control variables, while θ

i captures firm-specific fixed effects, which remain constant over time. To account for potential sectoral policy influences on the SHSC and SZSC policy effects, the model incorporates high-dimensional industry-year fixed effects η

j,t to control for industry-wide trends and external shocks. Finally, ε

i,j,t denotes the random error term.

Table 1 presents the definitions and measurement methods of key variables used in this study. The dependent variable, green total factor productivity (GTFP), is calculated using the SBM-DDF model and GML index. The key explanatory variable, HSGT, is a dummy variable indicating whether a firm is included in the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect (SHSC) or Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect (SZSC) trading list. Control variables include Size (natural logarithm of total assets), Lev (total liabilities divided by total assets), ROA (net profit divided by total assets), FirmAge (natural logarithm of firm age), SOE (state ownership dummy), Growth (revenue growth rate), Board (natural logarithm of board size), Top5 (ownership concentration of top five shareholders), BM (book-to-market ratio), Dual (CEO duality dummy), Mshare (managerial shareholding ratio), Cashflow (operating cash flow ratio), and TobinQ (growth opportunities measure).

In conclusion, the empirical model framework enhances the robustness and credibility of this study. By incorporating firm-specific and industry-year fixed effects, it effectively accounts for unobserved heterogeneity, while control variables help mitigate potential confounding factors. The multi-period DID approach enables the precise identification of causal relationships, establishing a strong basis for analyzing how capital market openness influences corporate green total factor productivity.

3.4. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the key variables. The average GTFP is 0.93, suggesting that firms experience a certain degree of green inefficiency. The mean value of HSGT is 0.19, indicating that 19% of the observations fall within the treatment group. Most continuous variables exhibit similar mean and median values, with relatively low standard deviations, implying strong data stability.

Table 3 presents the correlation matrix, revealing that the majority of correlation coefficients are below 0.3. This suggests that collinearity among variables is weak, minimizing potential multicollinearity concerns.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

Table 4 reports the baseline regression results. Columns (1) and (2) assess the overall policy impact of “Stock Connect” (HSGT), revealing an estimated effect of 0.003 on corporate GTFP, with the coefficient being statistically significant at the 1% level. This result suggests that the “Stock Connect” policy plays a positive role in enhancing corporate GTFP. To further dissect these effects, Columns (3) and (4) isolate the impact of the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect (SHSC). For this purpose, the sample is restricted to firms before the launch of the Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect (SZSC) in 2016 to eliminate potential interference, and HGT (coded 1 if a firm is in the SHSC trading list from its inclusion year, 0 otherwise) serves as the key explanatory variable. The estimated policy effect of SHSC is 0.002, which is statistically significant at the 5% level in Column (3) without controls and strengthens to 1% significance in Column (4) with controls. Subsequently, Columns (5) and (6) specifically examine the effect of SZSC by including only firms listed in Shenzhen, with SGT (coded 1 if a firm is in the SZSC trading list from its inclusion year, 0 otherwise) as the key explanatory variable. The findings reveal a more pronounced policy effect for SZSC, with an estimated coefficient of 0.005 for SGT. This effect is highly significant at the 1% level in both Column (5) without controls and Column (6) with controls. These results collectively indicate that both SHSC and SZSC individually contribute positively and significantly to enhancing corporate GTFP, with the SZSC demonstrating a comparatively larger impact.

Next, this study separately examines the effects of SHSC and SZSC. To isolate the impact of SHSC and eliminate potential interference from the SZSC policy, Columns (3) and (4) focus only on firms before SZSC was introduced in 2016. The key explanatory variable, HGT, is assigned a value of 1 if a firm is included in the SHSC trading list in the year of inclusion or later, and 0 otherwise. As shown in Columns (3) and (4), the estimated policy effect of SHSC stands at 0.002, demonstrating a statistically significant impact at the 5% threshold. This finding confirms that SHSC fosters a positive impact on corporate GTFP.

In Columns (5) and (6), the analysis shifts to assessing the impact of SZSC, including only firms listed in Shenzhen. The key explanatory variable, SGT, is set to 1 if a firm appears in the SZSC trading list in the year of inclusion or later; otherwise, it is assigned 0. The findings reveal that the policy effect of SZSC is 0.005, surpassing that of SHSC, with the coefficient being significantly positive at the 1% threshold, implying that SZSC’s impact surpasses that of SHSC. One possible explanation is that Shenzhen’s geographical proximity to Hong Kong facilitates greater trust and stronger connections between Shenzhen-listed firms and Hong Kong investors.

In summary, after evaluating both the overall policy effect and the effects of SHSC and SZSC separately at different time points, the results of the baseline regression indicate that both SHSC and SZSC policies have effectively promoted corporate green total factor productivity improvement, thus supporting Hypothesis 1.

4.2. Robustness Tests

4.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

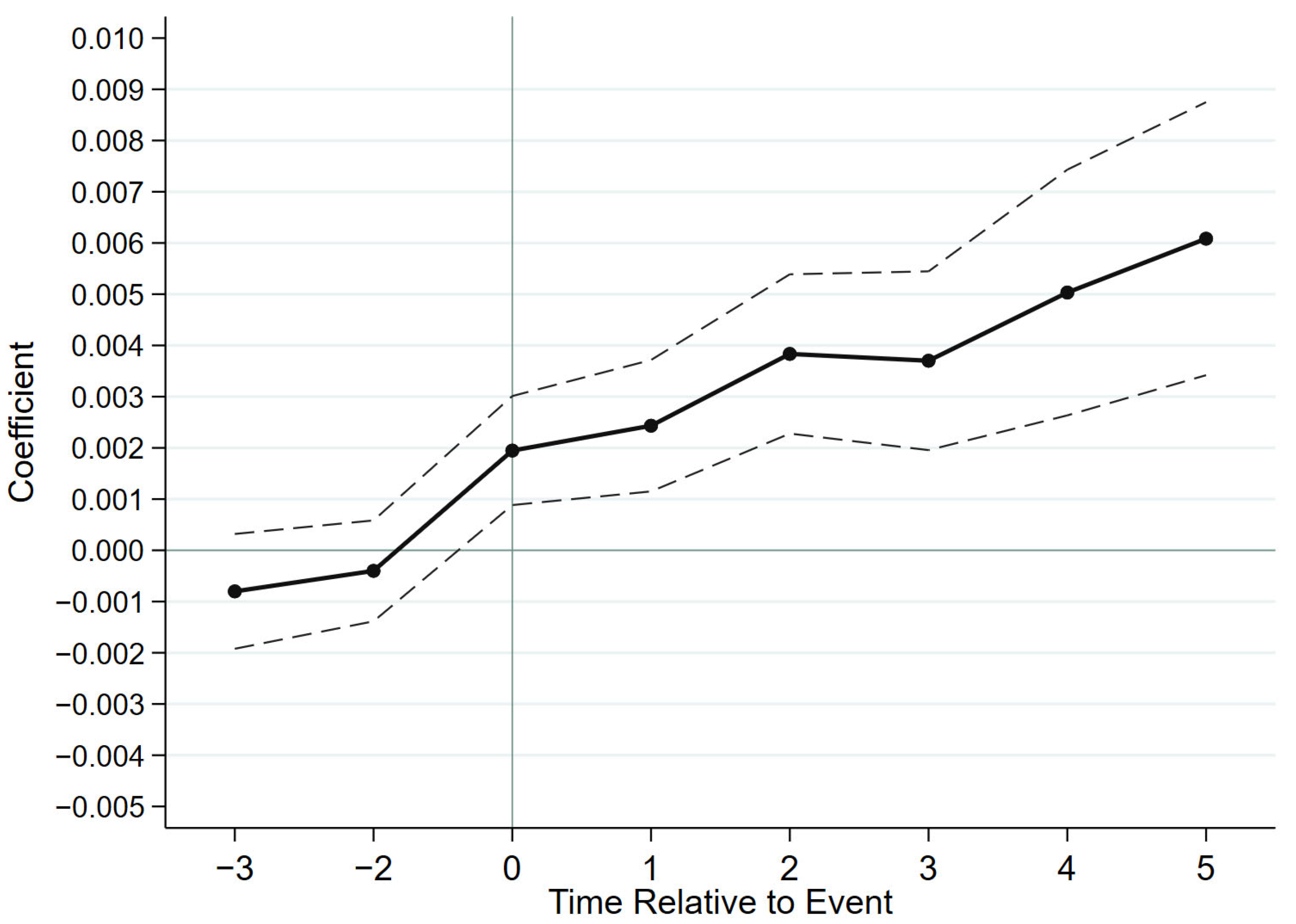

Given that the implications of the SHSC/SZSC trading mechanism for corporate operations is assessed using a multi-period difference-in-differences (DID) model, it is essential to confirm the validity of the parallel trend assumption. This assumption stipulates that, prior to policy implementation, the trends of the dependent variable in both the treatment and control groups are expected to follow analogous patterns.

To examine this, interaction terms are constructed based on the policy implementation year, as well as the years before and after the policy, for each treatment group. If the regression analysis reveals that pre-policy interaction terms do not exhibit statistical significance, it implies that both groups exhibit analogous pre-treatment trends. Conversely, if the interaction terms after policy implementation are statistically significant, highlighting that the policy meaningfully affects the dependent variable, namely green total factor productivity (GTFP).

Figure 1 presents the outcomes derived from the parallel trend examination. In the figure, the solid line represents the point estimates of the dynamic coefficients for each period, while the dashed lines on either side represent the 95% confidence intervals. Prior to policy implementation, the estimated coefficient confidence intervals for the treatment and control groups include zero, suggesting no statistically significant difference between them. However, following the introduction of the capital market openness policy, firms in the treatment group experience a notable increase in GTFP compared to the control group. Moreover, this positive effect persists and demonstrates an upward trajectory over time, reinforcing the notion that capital market openness consistently and effectively enhances corporate GTFP.

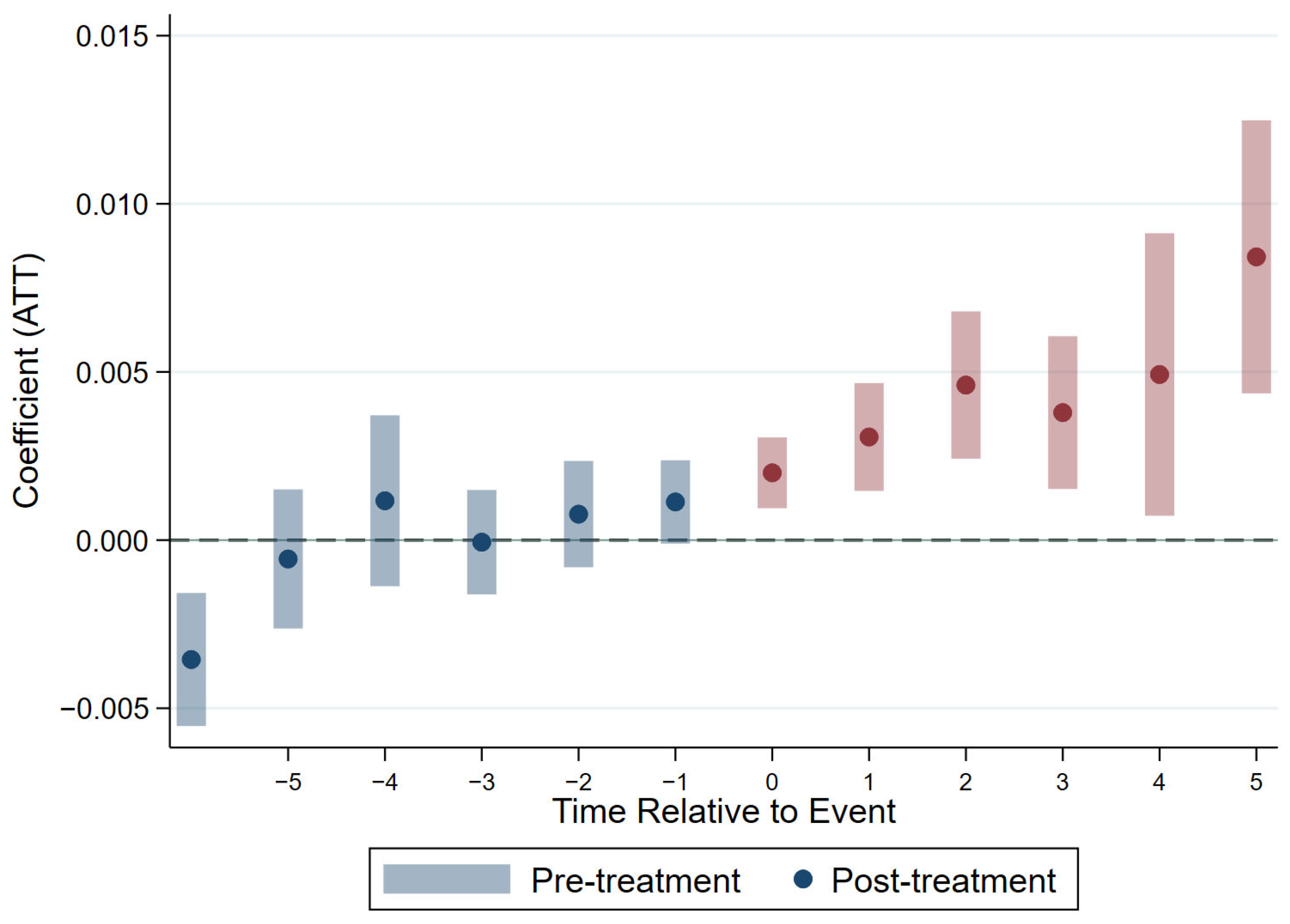

4.2.2. CS-DID

The estimation of difference-in-differences (DID) models with staggered adoption using Two-Way Fixed Effects (TWFE) may suffer from bias. To further test the robustness of our core conclusions, we employed the staggered DID estimator (CSDID) proposed by Callaway and Sant’Anna [

28] to examine treatment effects.

Figure 2 presents the event study plot based on CSDID estimates. As shown in

Figure 2, in the pre-policy periods, the point estimates of the average treatment effects fluctuate around zero and are not statistically significant, indicating that the treatment and control groups satisfied the parallel trends assumption prior to policy implementation. Post-policy, the effects become significantly positive and exhibit an increasing trend over time, consistent with our baseline regression results. Therefore, employing this more robust estimation method confirms that our core conclusions remain valid, enhancing the reliability of our findings.

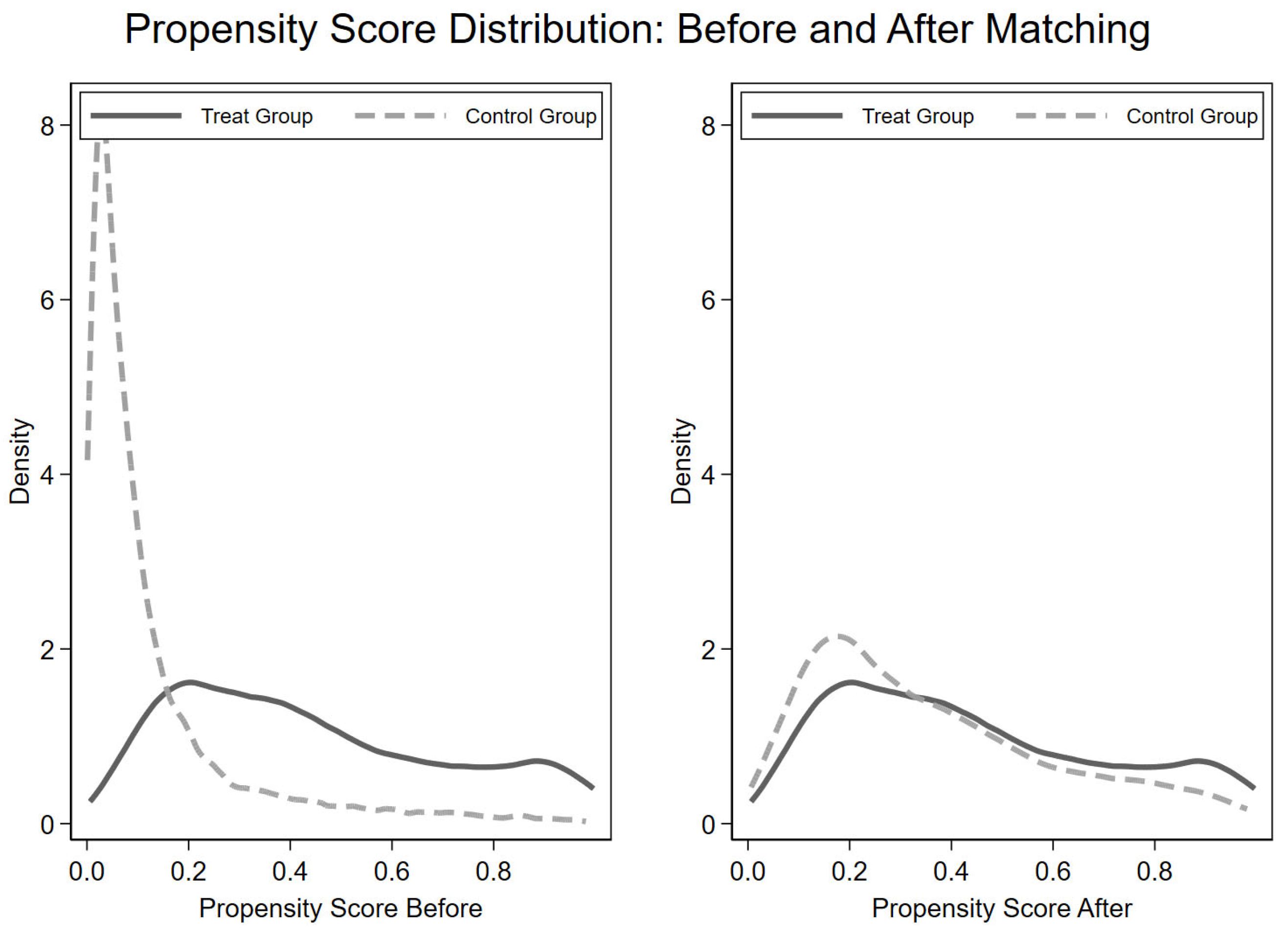

4.2.3. Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

To mitigate pre-existing disparities in firm characteristics between the treatment and control groups prior to SHSC/SZSC implementation, this study utilizes propensity score matching (PSM) to mitigate sample selection bias and reduce concerns related to endogeneity. A Logit model-based PSM approach is employed to identify comparable firms for those included in the SHSC/SZSC treatment group. The newly matched sample is then used to re-estimate the regression model.

Acknowledging pre-existing characteristic differences between treatment and control group firms prior to the ‘Shanghai-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect’ implementation, and to mitigate endogeneity from sample selection bias, this study, employs a Logit model-based Propensity Score Matching (PSM) to find matched samples for ‘Stock Connect’ eligible firms in the treatment group, subsequently re-estimating parameters based on this matched data. The PSM approach demonstrably succeeded in balancing covariates:

Figure 3 visually demonstrates the effect of propensity score matching. The left panel shows that before matching, the propensity score distributions for the treatment (solid line) and control (dashed line) groups were substantially different, indicating significant baseline imbalances. In contrast, the right panel shows that after matching, the two distributions are highly aligned. This intuitively illustrates PSM’s effectiveness in minimizing systematic differences in observable covariates, ensuring the matched treatment and control groups achieved a high degree of balance on these key characteristics.

After implementing PSM, the model is re-estimated using the matched sample.

Table 5 presents the primary regression results after matching. In Columns (1), (2), (5), and (6), the coefficients of the key explanatory variables (HSGT and SGT) exhibit a slight decrease compared to the baseline regression but remain statistically significant at the 5% level. This confirms that the core findings of this study are robust. The minor reduction in coefficient values may be attributed to the decrease in total sample size after matching. In Column (3), where HGT is estimated without control variables, no significant effect is observed. In Column (4), the significance level of HGT decreases compared to the baseline regression. This decline in significance may be due to two factors: For one, the limited time frame of the sample for HGT estimation—the sample in Columns (3) and (4) is restricted to the period from 2014 to before the launch of SZSC in 2016. Thus, the analysis does not capture the full effect of SHSC, but rather its initial phase. Since SHSC was the first capital market openness policy of its kind in China, there was limited market experience and unclear investor expectations at the time. The findings indicate that SHSC had a relatively weak impact during its initial two years (2014–2016). One possible explanation is the short observation window and sample reduction after matching. The earlier parallel trend test suggests that the policy effect strengthens over time. However, Columns (3) and (4) use a shorter time frame, and the matching process further reduces the sample size, limiting the ability to capture the long-term effects of SHSC. Consequently, the estimated HGT coefficient in these columns primarily reflects the early phase of SHSC, leading to a decline in statistical significance.

Overall, the propensity score matching analysis strengthens the reliability of the baseline regression findings and provides additional insights. The results indicate that capital market openness policies exert a more pronounced influence over time, while SHSC demonstrates weaker effects in its initial stages due to market uncertainty.

4.2.4. Variable and Sample Substitution Tests

To further mitigate potential biases arising from variable and sample selection, a series of robustness tests were conducted, with all results presented in

Table 6. First, we altered the measurement of the core dependent variable, corporate green total factor productivity (GTFP): Column (1) employed a super-efficiency SBM model without a specified radial vector for its calculation, while Column (2) replaced the undesirable output in the SBM model with total emissions of industrial wastewater, waste gas (including SO

2 et al.), and solid waste. Second, to examine the influence of specific subsamples and consider policy applicability, Column (3) restricted the analysis to firms in heavily polluting industries. Third, accounting for potential time lags in the policy’s effects, Column (4) re-estimated the model using GTFP in period t + 1 as the dependent variable. Furthermore, more robust estimation methods were also applied: Column (5) utilized two-way (firm and year level) clustered robust standard errors to address potential heteroskedasticity and serial correlation, and Column (6) employed the Inverse Probability Weighting Difference-in-Differences (IPW-DID) method to more effectively handle selection bias. In summary, after this comprehensive series of tests involving alternative measures for the core variable, adjustments to the sample scope, and the application of various more robust estimation strategies, the coefficient for the key explanatory variable HSGT consistently maintained the same direction as in the baseline regression and remained statistically significant across all specifications. These findings further validate the robustness of this study’s core conclusion that capital market openness promotes corporate green total factor productivity.

To evaluate whether the baseline regression outcomes are affected by subsample selection and policy relevance, Column (3) restricts the sample to heavily polluting industries. The findings indicate that the coefficient of the key explanatory variable remains consistent while maintaining statistical significance at the 1% level, confirming the robustness of the baseline regression results across different sample groups. Additionally, considering the potential time-lagged effect of the SHSC/SZSC policy, Column (4) replaces the dependent variable with GTFP in period t + 1 and re-estimates the regression model. After substituting the core dependent variable, the HSGT coefficient remains positively significant, strengthening the credibility of the core results.

Even after modifying both the sample selection criteria and the core dependent variable, the results persist in showing statistical significance and a positive trend. This further validates this study’s conclusions, confirming that capital market openness policies effectively enhance corporate GTFP.

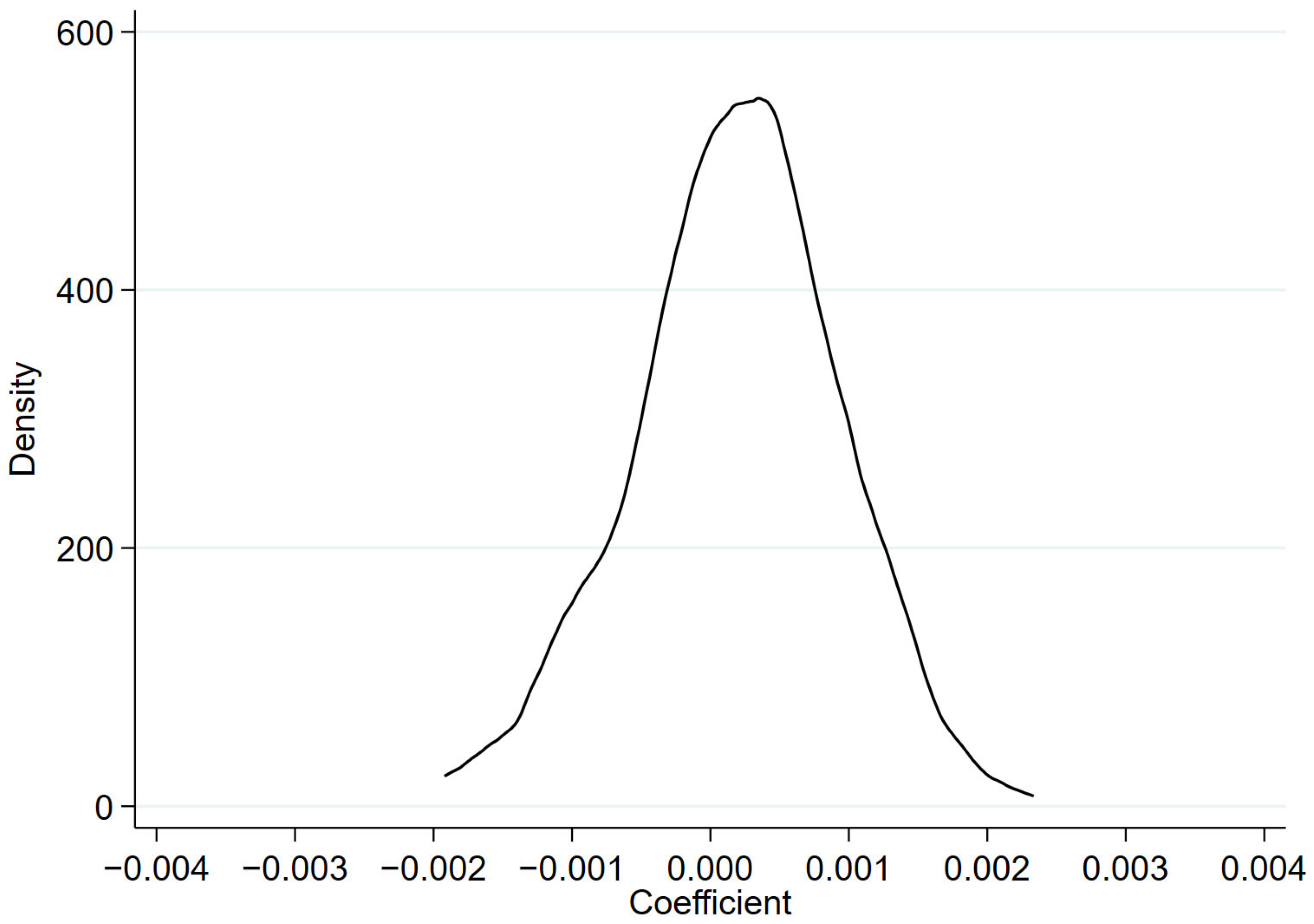

4.2.5. Placebo Test

To examine the impact of unobservable characteristics on the estimation results, this study conducts a placebo test using a randomized policy assignment approach. A random sample of firms is drawn from the full dataset, ensuring that the number of selected firms matches the actual SHSC/SZSC-listed firms. These randomly chosen firms are then designated as pseudo SHSC/SZSC firms, with their inclusion years assigned based on the original SHSC and SZSC listing proportions. This randomization process is repeated 500 times, with regressions conducted for each iteration.

Figure 4 presents the kernel density plot of the estimated coefficients. As expected in a placebo test, with estimated coefficients distributed normally and centered at zero. Moreover, the majority of randomly generated coefficients fall below those reported in the baseline regression, indicating that unobservable factors exert minimal influence on the estimation outcomes. Thus, even after accounting for unobservable characteristics, the study’s main findings remain robust.

To further test the robustness of our findings and rule out confounding effects from other contemporaneous unobservable factors, we conducted a falsification test by artificially advancing the actual policy implementation time to 2012. For all true treatment group firms, we assumed they were affected by the policy from 2012 and reconstructed a bogus policy treatment variable (bogus_did) for regression. The results showed that the estimated coefficient for this bogus_did variable was 0.001508 and statistically insignificant. This “null” result indicates that at an incorrect policy timing, the promoting effect of capital market openness on corporate green total factor productivity does not exist, thereby enhancing the reliability of our baseline regression results.

5. Plausible Mechanisms

Building upon the theoretical framework, the impact of capital market openness on GTFP primarily functions through two key channels.

5.1. Green “Hard Strength”

To measure a firm’s ability to obtain green financial support, this study employs green institutional investor entry (GI) and green fund investment (GFI) as proxy variables. According to financing alleviation theory and green governance theory, green investors exhibit lower-risk premium requirements for green projects, are more inclined to curb managerial misconduct, and prefer to invest in long-term, high-marginal-return green projects. If capital market openness introduces foreign institutional investors with a preference for green investments, firms can receive stable green financial support, thereby enhancing their green “hard strength” [

29,

30].

Following Jiang [

30], this study constructs the variables by utilizing data from the CSMAR fund market database, specifically the “Fund Entity Information Table” and the “Stock Investment Details Table”. By matching these datasets, this study obtains quarterly fund investment details for firms listed on the A-share markets. To identify green funds, keyword searches are conducted within investment objectives and investment scopes, targeting terms such as “environmental protection”, “ecology”, “green”, and “new energy development”. If a firm receives investments from such funds, it is classified as having green fund investment (GFI). The number of green funds investing in each listed firm is used to measure green institutional investor entry (GI), while green fund investment (GFI) is calculated as the total value of green fund investments divided by the firm’s net assets.

Additionally, this study selects invention-type green technological innovation (IGTI) and utility-type green technological innovation (PGTI) as proxy variables for measuring a firm’s green “hard strength” in terms of green technological innovation capability. Green “hard strength” primarily drives technological progress, expanding the production frontier and thereby improving GTFP. Consequently, green technological innovation is the most direct indicator of green “hard strength” and the most effective measure of foreign investors’ influence on corporate green technology development [

31].

The IGTI and PGTI variables are constructed based on prior research on technological innovation, which suggests that patent applications better represent innovation activities than granted patents. Patent applications are further categorized into invention-type patents and utility-type patents. To avoid distortions caused by joint patent applications, this study only considers independently filed patents by firms. Specifically, IGTI is defined as the natural logarithm of (1 + the number of independent green invention patent applications), while PGTI is calculated as the natural logarithm of (1 + the number of independent green utility patent applications).

Table 7 presents the empirical findings on how capital market openness influences firms’ green “hard strength”. The regression results indicate that, across Columns (1) to (4), the coefficients of HSGT remain significantly positive at the 1% level, offering strong evidence that capital market openness strengthens firms’ green “hard strength” and fosters GTFP growth.

From the perspective of green financial support, Columns (1) and (2) investigate how capital market openness influences the entry of green institutional investors (GI) and green fund investment (GFI). The findings indicate that the implementation of the SHSC/SZSC policy significantly enhances both the presence of green institutional investors and the scale of green fund investments in firms. This aligns with the financing alleviation theory, which suggests that capital market openness attracts foreign institutional investors who prioritize green investments. These investors, demonstrating higher risk tolerance for green projects, provide stable financial support, effectively easing firms’ financial constraints and fostering green development.

From the perspective of green technological innovation, Columns (3) and (4) examine the impact of capital market openness on invention-type green technological innovation (IGTI) and utility-type green technological innovation (PGTI). The empirical results reveal a substantial increase in both types of green innovation, underscoring a dual driving effect of capital market openness. On one hand, financial and technological spillovers occur as the inflow of foreign capital and expanded technology transfer channels help alleviate firms’ financial constraints and lower technological barriers to green innovation. Stable financial support, coupled with enhanced access to technological collaboration opportunities, plays a pivotal role in strengthening firms’ long-term green innovation capabilities. On the other hand, active monitoring by green investors is evident, as foreign institutional investors with expertise in green investments leverage their voting rights and supervisory influence to shape corporate governance. This encourages firms to increase green R&D investment and refine their innovation strategies, ultimately enhancing their overall green technological innovation capacity [

32].

In sum, the empirical findings align with the theoretical expectations: capital market openness enhances firms’ access to green financial support and stimulates green technological innovation, thereby contributing to their green “hard strength”. Ultimately, this mechanism leads to an overall improvement in GTFP.

5.2. Green “Soft Strength”

To assess firms’ green “soft strength”, this study employs green information disclosure (GD) and green responsibility undertaking (GRU) as corporate green obligation, and employs executive green experience (GE) and green governance as corporate green management.

The green information disclosure (GD) variable is constructed based on evaluating firms across five key dimensions: environmental liability disclosure, environmental performance and governance disclosure, environmental management disclosure, environmental certification disclosure, and environmental information disclosure. Each dimension consists of 25 scoring items, with firms earning 1 point for disclosing an item and 0 otherwise. The total score is then standardized to develop the green information disclosure (GD) indicator [

33].

The green responsibility undertaking (GRU) utilizing data from the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Research Report published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) Economics Department since 2009, which focuses on environmental responsibility. Drawing from the China Research Data Service Platform (CNRDS), this study classifies firms’ environmental responsibility activities into eight subcategories, including environmentally beneficial products, pollution reduction measures, circular economy initiatives, and energy conservation efforts. Each subcategory is assigned 1 point if applicable and 0 otherwise, with the total score forming the GRU variable [

26].

The executive green experience (GE) variable is constructed using personal resume data from Sina Finance [

6]. A CEO is classified as having green experience if their resume includes keywords such as “environment”, “environmental protection”, “new energy”, “clean energy”, “ecology”, “low-carbon”, “sustainability”, “energy-saving”, or “green”. In such cases, the GE indicator is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it is 0.

The corporate green governance (GG) variable is measured using professional environmental governance ratings from international credit rating agencies. Since foreign institutional investors often reference internationally recognized rating agencies in their investment decisions, this study adopts the Bloomberg ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) rating system, which is widely accepted in financial markets. Specifically, the environmental (E) dimension of the Bloomberg ESG rating is extracted as the corporate green governance (GG) indicator, as it comprehensively assesses firms’ environmental management, pollution control, resource utilization, and climate change policies, providing a robust measure of corporate green governance capabilities [

34].

Columns (1)–(4) of

Table 8 present empirical findings on how green “soft strength” contributes to corporate GTFP under capital market openness. The results indicate that in all columns, the coefficients of HSGT remain significantly positive at least at the 5% level, supporting the theoretical expectation that capital market openness strengthens firms’ green “soft strength” and promotes green development.

Columns (1) and (2) specifically examine the impact of capital market openness on green information disclosure (GD) and green responsibility undertaking (GRU). The findings suggest that the introduction of the SHSC/SZSC policy leads to a notable improvement in firms’ green information disclosure quality, while also encouraging them to actively assume environmental responsibilities. This finding can be explained from two perspectives: One is market signaling. In an open capital market, firms aiming to attract foreign institutional investors with green investment preferences tend to proactively enhance green information disclosure and environmental responsibility efforts to signal their commitment to sustainable development. The other is investor governance: According to supervisory governance theory, foreign institutional investors actively exercise shareholder rights and use other governance mechanisms to urge firms to improve green transparency and strengthen environmental responsibility awareness.

Columns (3) and (4) explore how capital market openness influences executive green experience (GE) and corporate green governance (GG). The findings indicate that the oversight and influence of foreign institutional investors play a crucial role in strengthening firms’ environmental governance frameworks. This aligns with the theoretical hypothesis that through board meetings and shareholder meetings, foreign institutional investors directly influence corporate management, support executives with green management expertise, and promote the appointment of more green-experienced executives in listed firms. Additionally, they encourage firms to establish more standardized and comprehensive environmental governance frameworks.

In summary, the empirical findings confirm this study’s hypothesis: capital market openness enhances firms’ green “soft strength” by improving green information disclosure, environmental responsibility undertaking, and corporate green governance, ultimately leading to higher GTFP.

6. Cross-Sectional Heterogeneity

Building on the previous theoretical analysis and mechanism tests, capital market openness enhances corporate GTFP through the dual pathways of green “soft strength” and green “hard strength”. To further explore the heterogeneous effects of this relationship, this study conducts subgroup analyses from three perspectives: institutional investor communication, market competition intensity, and ownership structure. The core participants in capital market openness are foreign institutional investors, who directly influence corporate green behavior through supervisory governance. The extent of communication between institutional investors and firms plays a crucial role in determining the depth and effectiveness of investment strategies. Therefore, this study uses the frequency of institutional investor research visits as a measure of communication adequacy and groups firms accordingly to examine whether investor communication intensity moderates the policy effect. Additionally, from the perspective of market competition theory, the entry of new investors driven by capital market openness increases competitive pressure among firms. In highly competitive markets, firms are more motivated to strengthen their green development strategies to gain a competitive advantage and attract investor interest. This study uses the Herfindahl Index to quantify industry competition intensity and explores how firms adjust their responses to the policy under different levels of competitive pressure. Moreover, differences in ownership structure result in firms experiencing distinct governance mechanisms and incentive frameworks. Compared to state-owned enterprises, privately owned enterprises tend to be more responsive to market-oriented reforms and have greater decision-making autonomy in investment strategies. Considering this institutional context, this study categorizes firms based on ownership type to assess whether ownership structure affects the policy impact.

The heterogeneity analysis results, shown in

Table 9, reveal substantial differences in how capital market openness affects corporate GTFP across various subgroups. First, the subgroup variable for institutional investor communication is derived from institutional research visit records available in the CSMAR Investor Relations database. If institutional investors examine a firm in a particular year, it is coded as 1; if not, it is coded as 0. According to the regression analysis, the HSGT coefficient remains significant in both categories, yet firms engaging more frequently with institutional investors show a significantly higher coefficient, supported by a between-group difference test. This evidence supports the notion that capital market openness exerts a greater influence on corporate GTFP among firms that maintain strong engagement with institutional investors. This observation is in accordance with investor governance theory, which posits that foreign institutional investors facilitate corporate GTFP improvements by reinforcing their monitoring role and communication channels through active involvement. Second, to evaluate market competition, this study applies the Herfindahl Index, which quantifies competitive pressure by summing the squared ratios of each firm’s core business revenue to the total industry revenue. Markets with lower Herfindahl Index values exhibit higher levels of competition. This study segments firms into high-competition and low-competition groups according to the median value of competitive pressure. Firms operating in highly competitive markets show a significantly stronger HSGT coefficient in terms of both magnitude and statistical relevance relative to those in less competitive environments. The evidence indicates that firms facing greater market competition are more responsive to capital market openness, especially in advancing their green development initiatives. The observed pattern reflects the incentive effect of market competition: in intensely competitive markets, firms are more motivated to leverage the opportunities brought by capital market openness by enhancing green information transparency, strengthening environmental responsibility, and increasing green technology investment, thereby driving their green transformation and securing a competitive advantage.

Finally, the heterogeneity analysis based on ownership structure reveals that non-SOEs exhibit a stronger green development response to the policy compared to SOEs. Firms are grouped based on whether they are state-owned or privately owned, and the results indicate that the HSGT coefficient is significantly larger in non-SOEs. This finding suggests that private firms, due to their higher degree of operational autonomy and stronger market orientation, are more responsive to capital market openness and more proactive in aligning their strategies with investors’ green investment preferences. In contrast, SOEs, which operate under different governance structures and incentive mechanisms, may face constraints in fully capitalizing on the green development opportunities associated with capital market openness. The results highlight that non-SOEs, with greater flexibility in investment decisions and a stronger incentive to adapt to market signals, can more effectively integrate green development strategies into their business models, ultimately achieving greater improvements in GTFP.

The heterogeneity analysis highlights significant variations in how corporate GTFP is affected by capital market openness, contingent upon firm characteristics. Firms that engage more frequently with institutional investors experience greater benefits from the policy, as deeper interactions enhance investor oversight and improve governance efficiency. Moreover, intense market competition strengthens the policy’s impact, pushing firms facing greater competitive pressure to implement proactive green strategies for differentiation and investor appeal. Furthermore, non-SOEs exhibit greater sensitivity to the policy than SOEs, highlighting differences in incentive structures across ownership types. These findings underscore the importance of firm-specific attributes in shaping the influence of capital market openness on corporate GTFP.

7. Conclusions

This study explores the impact of capital market openness on corporate green total factor productivity (GTFP) by analyzing Chinese listed firms and utilizing the Shanghai-Hong Kong and Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect (SHSC/SZSC) as a quasi-natural experiment. Applying a multi-period difference-in-differences (DID) approach, the results demonstrate that corporate green development benefits significantly from capital market openness by sustainably and robustly enhancing GTFP. Mechanism analysis further demonstrates that this influence manifests through two key pathways: green “hard strength” and green “soft strength”. Regarding green “hard strength”, capital market openness facilitates firms’ access to green financial resources and strengthens their green technological innovation capabilities. Simultaneously, with respect to green “soft strength”, the policy significantly improves corporate green information disclosure, environmental responsibility commitments, executives’ green experience, and environmental governance practices. The interaction between green “hard strength” and green “soft strength” creates a positive feedback loop, further driving sustainable corporate green development.

The heterogeneity analysis reveals notable variations in the policy’s effectiveness across different firm characteristics. Specifically, firms with more frequent communication with institutional investors are better positioned to leverage the governance and supervisory benefits brought by foreign investors. Moreover, firms facing higher competitive pressure tend to adopt green transformation as an approach to securing a market advantage. Additionally, non-state-owned enterprises, characterized by stronger market orientation, exhibit a more proactive response to capital market openness compared to state-owned enterprises.

Building on these findings, this study suggests the following policy initiatives. First, further deepen capital market openness and refine the market integration mechanisms. Building upon the SHSC/SZSC framework, policymakers should expand cross-border investment channels, optimize capital flow mechanisms, and create a more favorable institutional environment for foreign institutional investors. Additionally, it is essential to attract foreign investors with a strong green investment focus, leveraging their influence to facilitate corporate green transformation. Second, establish a multi-tiered support system for green development. On one hand, strengthening corporate green information disclosure regulations can enhance transparency, enabling investors to better identify and support environmentally responsible firms. On the other hand, promoting innovation in green financial products and expanding corporate green financing channels will provide more stable financial support for green technological advancements.

This study profoundly reveals the pivotal role of capital market openness in deepening China’s financial market reforms and advancing corporate green development. Its conclusions offer significant implications for other countries, particularly for emerging economies striving to strike a balance between financial liberalization and sustainable development. However, when extending these findings to other nations, it is imperative to fully recognize that their applicability is significantly shaped by the unique institutional characteristics of each country. Countries vary in key dimensions, including the maturity of their financial markets, the comprehensiveness of their legal and regulatory frameworks, the stringency of environmental oversight, corporate governance structures, and the level of investor protection. Compared to emerging markets like China, developed economies typically possess more mature capital markets and more stringent Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) standards. Consequently, the marginal effect of capital market openness on their corporate green transformation may differ. Emerging economies, when drawing upon these experiences, must prudently evaluate how their domestic institutional environments may constrain and shape the efficiency of capital inflows, investor behavior patterns, and corporate responsiveness to green incentives. This underscores the necessity for broader international comparative and institutional analysis in future research.

While this research offers valuable insights, its limitations and avenues for future research must be acknowledged. First, this study’s conclusions are rooted in the specific context of China and focus on companies listed under the Shanghai-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect program. Their direct generalizability to economies at different developmental stages, firms with diverse ownership structures and sizes, and other forms of financial interconnectivity mechanisms requires further in-depth validation through more extensive and nuanced cross-country and cross-mechanism comparative research. Second, as the assessment frameworks for green performance and sustainability outcomes are constantly evolving, future research should actively explore and employ more cutting-edge, multidimensional metrics to enhance the depth and precision of analysis. Furthermore, the future research agenda should also concentrate on the multifaceted impact pathways of other forms of financial openness (such as foreign bank entry) on corporate green transformation. It should also examine the different roles played by international investors with diverse backgrounds, investment preferences, and horizons in the global corporate greening process. A thorough investigation of these issues will provide critical theoretical insights and empirical support for constructing a more resilient, inclusive, and effective financial system that serves global sustainable development goals.