The Role of Open Innovation in Enhancing Organizational Resilience and Sustainability Performance Through Organizational Adaptability

Abstract

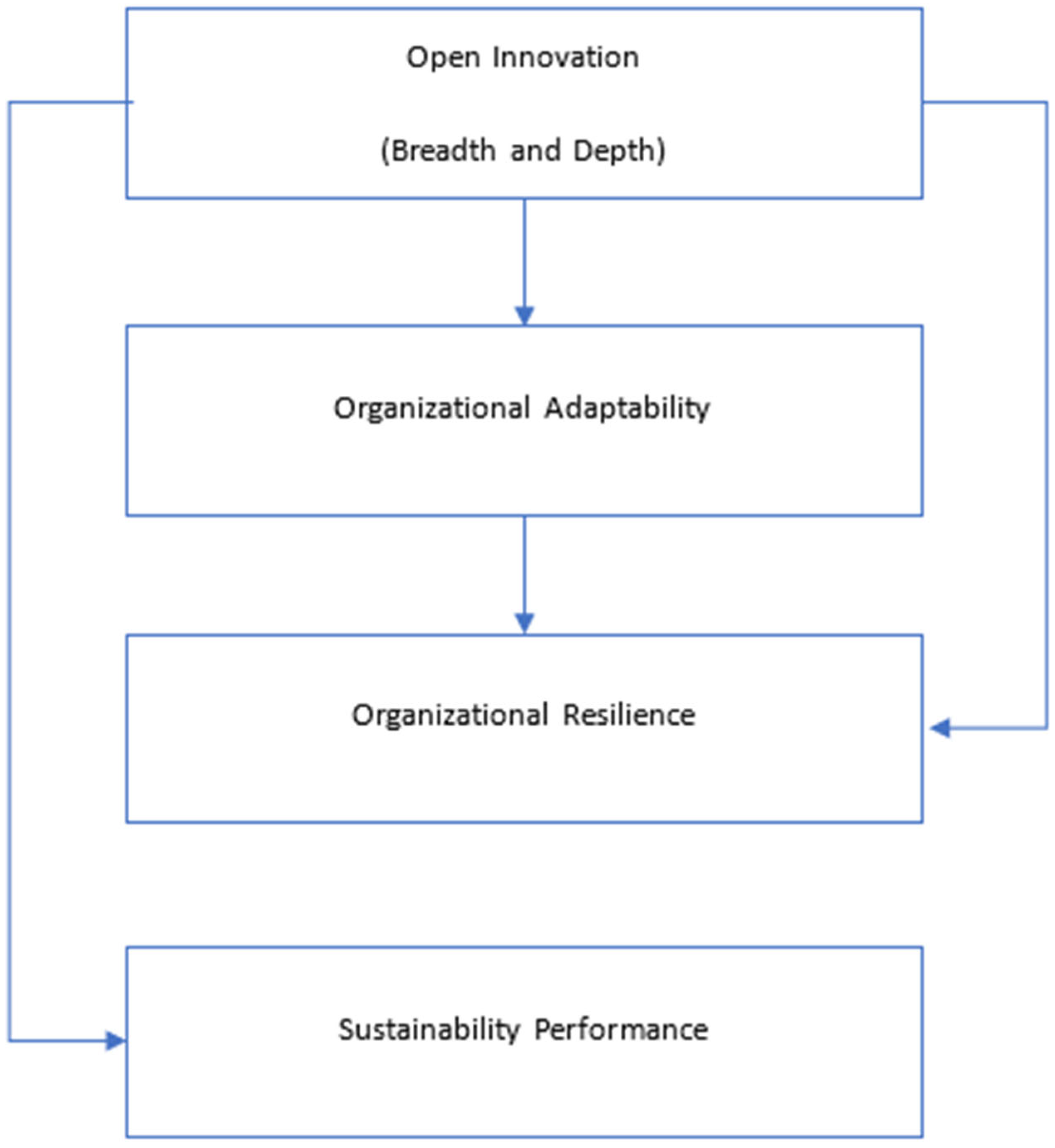

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Review

2.1.1. Open Innovation

2.1.2. Organizational Adaptability

2.1.3. Organizational Resilience

2.1.4. Sustainability Performance

2.2. Theoretical Framework

Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT)

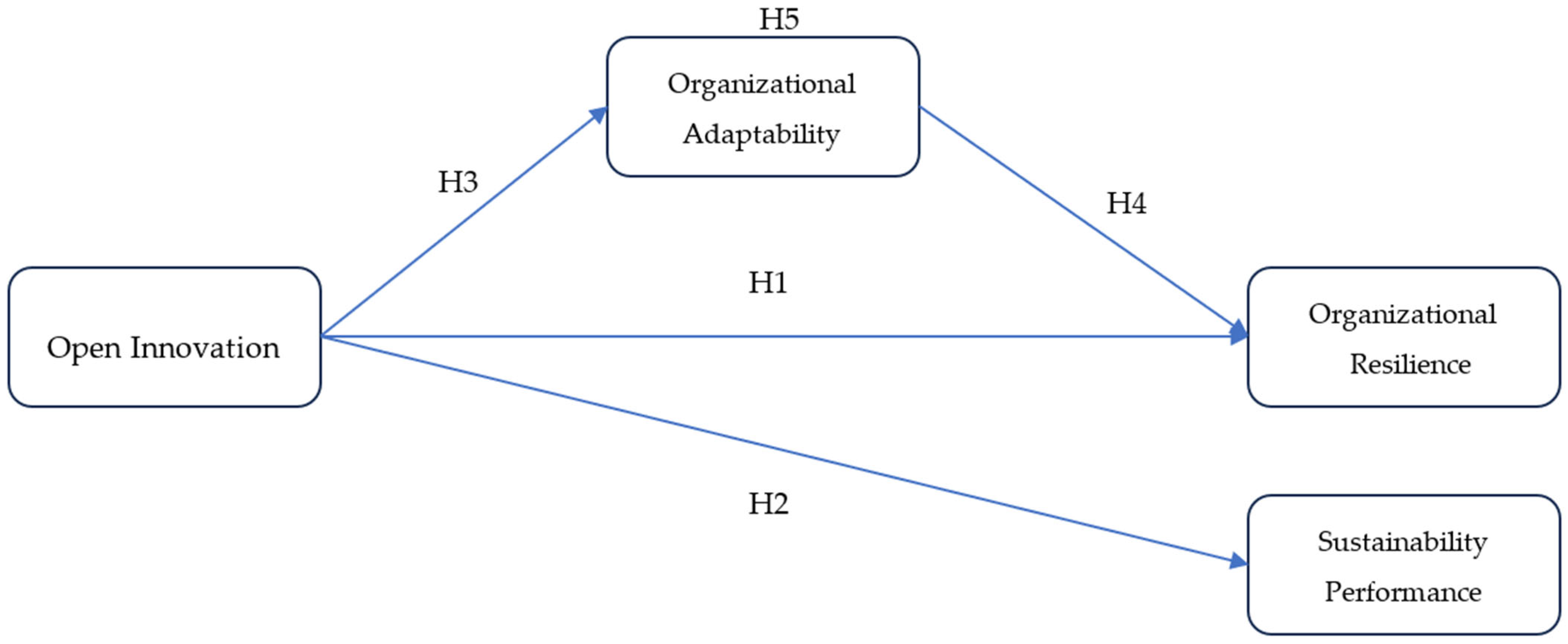

2.3. Hypothesis Development

2.3.1. Open Innovation and Organizational Resilience

2.3.2. Open Innovation and Sustainability Performance

2.3.3. Open Innovation and Organizational Adaptability

2.3.4. Organizational Adaptability and Organizational Resilience

2.3.5. Role of Organizational Adaptability (Mediation Role)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement and Analytical Techniques

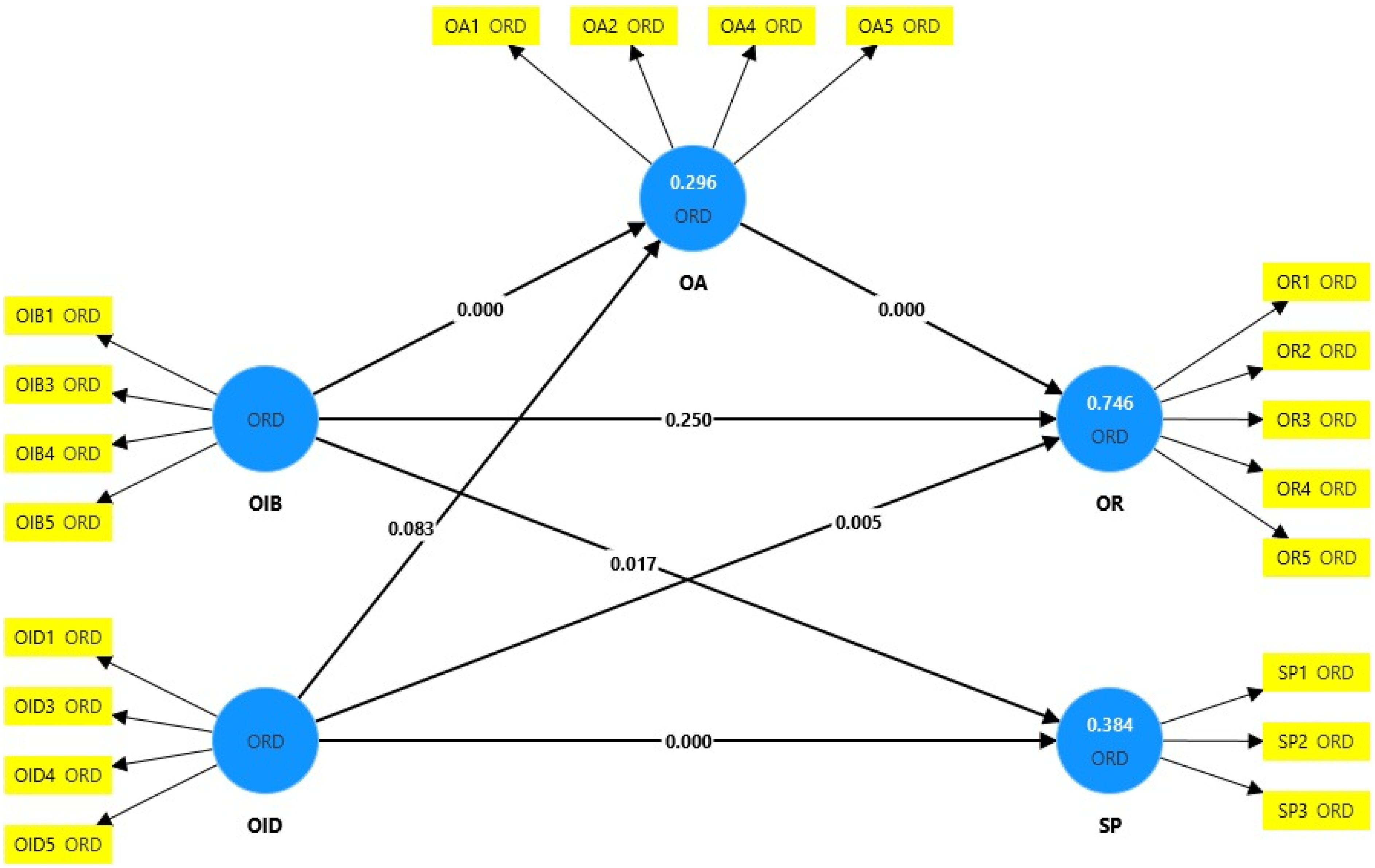

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Results

4.2. Assessing the Measurement Model

4.3. Assessing the Structure Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Open Innovation and Organizational Resilience

5.2. Open Innovation and Sustainability Performance

5.3. Organizational Adaptability and Organizational Resilience

5.4. Open Innovation and Organizational Adaptability

5.5. The Mediating Role of Organizational Adaptability

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

6.2. Practical Contribution

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Indicators | Open innovation Breadth (Bahemia, Squire, & Cousins, 2017 [64]) |

| OIB1 | Our organization aims to gain access to new technologies, expertise, and know-how. |

| OIB2 | Our organization seeks to complement our in-house research and development capability. |

| OIB3 | Our organization works to develop the concept of the new product and/or any related process. |

| OIB4 | Our organization designs and engineers new products and/or any related processes. |

| OIB5 | Our organization develops and tests the prototypes of the new product and/or any related process. |

| Key: 1—Strongly disagree, 2—disagree, 3—undecided, 4—Agree, 5—Strongly agree | |

| Indicators | Open innovation depth (Bahemia, Squire, & Cousins, 2017 [64]) |

| OID1 | Our organization and the external parties helped each other to accomplish their tasks in the most effective way. |

| OID2 | Our organization and the external parties tried to achieve goals jointly. |

| OID3 | Our organization and the external parties shared ideas, information, and/or resources. |

| OID4 | Our organization and the external parties took the project’s technical and operational decisions together. |

| OID5 | There was open communication between our firm and the external parties. |

| Key: 1—Strongly disagree, 2—disagree, 3—undecided, 4—Agree, 5—Strongly agree | |

| Indicators | Organizational adaptability (Tuominen, Rajala, Möller, & Anttila, 2003 [24]) |

| OA1 | Our organization is proactive in adopting new technologies to stay competitive. |

| OA2 | Our organization actively monitors market trends, and customers need to stay ahead. |

| OA3 | Our organization continuously improves our operations based on feedback and external trends. |

| OA4 | Our management encourages flexibility and supports innovation. |

| OA5 | Teams across different departments work together effectively during change. |

| Key: 1—Strongly disagree, 2—disagree, 3—undecided, 4—Agree, 5—Strongly agree | |

| Indicators | Organizational resilience (Olaleye, 2024 [65]) |

| OR1 | Our organization has strong social connections. |

| OR2 | Our organization finds it easy to adapt to changing situations. |

| OR3 | Our management team is optimistic, even when things are difficult. |

| OR4 | Our management team is usually calm in high-stress situations. |

| OR5 | Our leader/manager feels confident in the abilities of employees to tackle problems. |

| Key: 1—Strongly disagree, 2—disagree, 3—undecided, 4—Agree, 5—Strongly agree | |

| Indicators | Sustainability performance (Gelhard & Delft, 2016 [66]) |

| SP1 | We are the first to offer environmentally friendly products/services in the marketplace. |

| SP2 | Our competitors consider us a leading company in the field of sustainability. |

| SP3 | We develop new products/services or improve existing products/services that are regarded as sustainable for society and the environment. |

| SP4 | Our reputation in terms of sustainability is better than the sustainability reputation of our competitors. |

| SP5 | Compared to our competitors, we more thoroughly respond to societal, and ethical demands. |

| Key: 1—Strongly disagree, 2—disagree, 3—undecided, 4—Agree, 5—Strongly agree |

References

- UAE National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence. Available online: https://ai.gov.ae/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/UAE-National-Strategy-for-Artificial-Intelligence-2031.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- The UAE’s Future Roadmap|The Official Portal of the UAE Government. Available online: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/uae-in-the-future/uae-future (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Chesbrough, H. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-1-57851-837-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaverbeke, W.; Cloodt, M. Theories of the Firm and Open Innovation. In New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 256–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchek, S. Organizational Resilience: A Capability-Based Conceptualization. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st-century Business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Jia, J. Investigating the Impact Factors of the Logistics Service Supply Chain for Sustainable Performance: Focused on Integrators. Sustainability 2019, 11, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushman, M.L.; O’Reilly, C.A. Ambidextrous Organizations: Managing Evolutionary and Revolutionary Change. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.M.L.; Teoh, S.Y.; Yeow, A.; Pan, G. Agility in Responding to Disruptive Digital Innovation: Case Study of an SME. Inf. Syst. J. 2019, 29, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N.; Singh, A.K. Artificial Intelligence Capabilities, Open Innovation, and Business Performance—Empirical Insights from Multinational B2B Companies. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2024, 117, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Prado, G.F.; de Souza, J.T.; Piekarski, C.M. Sustainable and Innovative: How Can Open Innovation Enhance Sustainability Practices? Sustainability 2025, 17, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciasullo, M.V.; Chiarini, A.; Palumbo, R. Mastering the Interplay of Organizational Resilience and Sustainability: Insights from a Hybrid Literature Review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 1418–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Moreno, A.; Martín-Rojas, R.; García-Morales, V.J. The Key Role of Innovation and Organizational Resilience in Improving Business Performance: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 77, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nuaimi, F.M.S.; Singh, S.K.; Ahmad, S.Z. Open Innovation in SMEs: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 484–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikandar, H.; Kohar, U.H.A.; Corzo-Palomo, E.E.; Gamero-Huarcaya, V.K.; Ramos-Meza, C.S.; Shabbir, M.S.; Jain, V. Mapping the Development of Open Innovation Research in Business and Management Field: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 15, 9868–9890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for Innovation: The Role of Openness in Explaining Innovation Performance among U.K. Manufacturing Firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Bogers, M. Leveraging External Sources of Innovation: A Review of Research on Open Innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 814–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vrande, V.; De Jong, J.P.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; De Rochemont, M. Open Innovation in SMEs: Trends, Motives and Management Challenges. Technovation 2009, 29, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. The Foundations of Enterprise Performance: Dynamic and Ordinary Capabilities in an (Economic) Theory of Firms. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Hand in Glove: Open Innovation and the Dynamic Capabilities Framework. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2020, 1, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, M.; Rajala, A.; Moller, K.; Anttila, M. Assessing Innovativeness through Organisational Adaptability: A Contingency Approach. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2003, 25, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisdiono, P.; Said, J.; Yusoff, H.; Hermawan, A.A. Examining Leadership Capabilities, Risk Management Practices, and Organizational Resilience: The Case of State-Owned Enterprises in Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muadzah, S.; Suryanto, S. Organizational Culture and Resilience: Systematic Literature Review. J. Ilm. Manaj. Ekon. Akunt. MEA 2024, 8, 1426–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Weber, T.J. Leadership: Current Theories, Research, and Future Directions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-7879-9649-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen, M. The Environmental–Social Interface of Sustainable Development: Capabilities, Social Capital, Institutions. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value: How to Reinvent Capitalism—And Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth. In Managing Sustainable Business; Lenssen, G.G., Smith, N.C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 323–346. ISBN 978-94-024-1142-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, J.J.; Smith, J.S.; Gleim, M.R.; Ramirez, E.; Martinez, J.D. Green Marketing Strategies: An Examination of Stakeholders and the Opportunities They Present. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M. Market-Focused Sustainability: Market Orientation Plus! J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. Invited Editorial: A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm: Fifteen Years After. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Wieseke, J.; Hoyer, W.D. Social Identity and the Service-Profit Chain. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sethia, N.K.; Srinivas, S. Mindful Consumption: A Customer-Centric Approach to Sustainability. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berns, M.; Townend, A.; Khayat, Z.; Balagopal, B.; Reeves, M.; Hopkins, M.S.; Kruschwitz, N. The Business of Sustainability: What It Means to Managers Now. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2009, 5, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, E. Customer Participation and the Trade-off between New Product Innovativeness and Speed to Market. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufteros, X.; Vonderembse, M.; Jayaram, J. Internal and External Integration for Product Development: The Contingency Effects of Uncertainty, Equivocality, and Platform Strategy. Decis. Sci. 2005, 36, 97–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A Natural Resource-Based View of the Firm: Tilburg University. Work Organ. Res. Cent. 1994, 94, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidumolu, R.; Prahalad, C.K.; Rangaswami, M.R. Why Sustainability Is Now the Key Driver of Innovation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, L.; Rumelt, R.P.; Schendel, D.E.; Teece, D.J. Fundamental Issues in Strategy: A Research Agenda. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, G.; Xu, H.; Cui, Q.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Hickey, P.J. Influence Mechanism of Organizational Flexibility on Enterprise Competitiveness: The Mediating Role of Organizational Innovation. Sustainability 2020, 13, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltantawy, R.A. The Role of Supply Management Resilience in Attaining Ambidexterity: A Dynamic Capabilities Approach. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W.; Appleyard, M.M. Open Innovation and Strategy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2007, 50, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Hurtado-Torres, N.; Sharma, S.; García-Morales, V.J. Environmental Strategy and Performance in Small Firms: A Resource-Based Perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 86, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, M.; Grimaldi, M.; Locatelli, G.; Serafini, M. How Does Open Innovation Enhance Productivity? An Exploration in the Construction Ecosystem. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 168, 120740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, M.F.; Tiwari, S.; Petraite, M.; Mubarik, M.; Raja Mohd Rasi, R.Z. How Industry 4.0 Technologies and Open Innovation Can Improve Green Innovation Performance? Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 32, 1007–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.C.J.; Huizingh, E.K.R.E. When Is Open Innovation Beneficial? The Role of Strategic Orientation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 1235–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, B.D.; Belitski, M. The Limits to Open Innovation and Its Impact on Innovation Performance. Technovation 2023, 119, 102519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endres, H. Adaptability Through Dynamic Capabilities; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-658-20156-2. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, R.; Luo, J.; Liu, M.J.; Yu, J. Understanding Organizational Resilience in a Platform-Based Sharing Business: The Role of Absorptive Capacity. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghfous, A. Absorptive Capacity and the Implementation of Knowledge-Intensive Best Practices. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 2004, 69, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Barasa, E.; Mbau, R.; Gilson, L. What Is Resilience and How Can It Be Nurtured? A Systematic Review of Empirical Literature on Organizational Resilience. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2018, 7, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.F. Adaptability to Change for Sustainability: In Advances in Business Strategy and Competitive Advantage; Bakhit, W., El Nemar, S., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 61–80. ISBN 979-8-3693-5360-8. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, S.; Seville, E.; Vargo, J.; Brunsdon, D. Facilitated Process for Improving Organizational Resilience. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2008, 9, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S.; Schoemaker, P.J.H. Adapting to Fast-Changing Markets and Technologies. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Zhao, X.; Jung, K.; Yigitcanlar, T. The Culture for Open Innovation Dynamics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qrunfleh, S.; Tarafdar, M. Lean and Agile Supply Chain Strategies and Supply Chain Responsiveness: The Role of Strategic Supplier Partnership and Postponement. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2013, 18, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, E.E.; Johnny, E.; Sylva, W. Dynamic Capabilities and Organizational Resilience of Manufacturing Firms in Nigeria. Vis. J. Bus. Perspect. 2022, 26, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Company Registrars Within the UAE. Available online: https://www.moec.gov.ae (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Kotrlik, J.; Higgins, C. Organizational Research: Determining Appropriate Sample Size in Survey Research Appropriate Sample Size in Survey Research. Inf. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2001, 19, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. A Culture General Assimilator: Preparation for Various Types of Sojourns. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1986, 10, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahemia, H.; Squire, B.; Cousins, P. A Multi-Dimensional Approach for Managing Open Innovation in NPD. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 1366–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, B.R.; Lekunze, J.N.; Sekhampu, T.J.; Khumalo, N.; Ayeni, A.A.W. Leveraging Innovation Capability and Organizational Resilience for Business Sustainability Among Small and Medium Enterprises: A PLS-SEM Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelhard, C.; Von Delft, S. The Role of Organizational Capabilities in Achieving Superior Sustainability Performance. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4632–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Response to Leslie Hayduk’s Review of Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed. Can. Stud. Popul. 2018, 45, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blome, C.; Hollos, D.; Paulraj, A. Green Procurement and Green Supplier Development: Antecedents and Effects on Supplier Performance. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, McGraw-Hill Series in Psychology; 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978; ISBN 978-0-07-047465-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–47. ISBN 978-3-319-05542-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Wei, L.; Wei, L. Open Innovation, Organizational Resilience, and the Growth of SMEs in Crisis Situations. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 11009–11023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guennoun, A.; El Jamoussi, Y.; Bourkane, S.; Habbani, S. The Organizational Resilience in Startups through the Lens of Innovation. Corp. Gov. Organ. Behav. Rev. 2024, 8, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirghaderi, S.A.; Sheikh Aboumasoudi, A.; Amindoust, A. Developing an Open Innovation Model in the Startup Ecosystem Industries Based on the Attitude of Organizational Resilience and Blue Ocean Strategy. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 181, 109301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kor, Y.Y.; Mahoney, J.T.; Michael, S.C. Resources, Capabilities and Entrepreneurial Perceptions. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 1187–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, R.; Globocnik, D.; Perl-Vorbach, E.; Baumgartner, R.J. Open Innovation and Its Effects on Economic and Sustainability Innovation Performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, B.; Filippelli, S. Sustainability and Open Innovation: Main Themes and Research Trajectories. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K. Resilience in Business and Management Research: A Review of Influential Publications and a Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizingh, E.K.R.E. Open Innovation: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Technovation 2011, 31, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Ye, H.; Teo, H.H.; Li, J. Information Technology and Open Innovation: A Strategic Alignment Perspective. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naruetharadhol, P.; Srisathan, W.A.; Ketkaew, C. The Effect of Open Innovation Implementation on Small Firms’ Propensity for Inbound and Outbound Open Innovation Practices. In Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications; Tallón-Ballesteros, A.J., Ed.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; ISBN 978-1-64368-120-7. [Google Scholar]

- Olaleye, B.R.; Anifowose, O.N.; Efuntade, A.O.; Arije, B.S. The Role of Innovation and Strategic Agility on Firms’ Resilience: A Case Study of Tertiary Institutions in Nigeria. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlander, L.; Gann, D.M. How Open Is Innovation? Res. Policy 2010, 39, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.B.; Birkinshaw, J. The Antecedents, Consequences, and Mediating Role of Organizational Ambidexterity. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 224 | 53% |

| Male | 196 | 47% |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 90 | 21% |

| 25–34 | 200 | 48% |

| 34–44 | 98 | 23% |

| 45–54 | 22 | 5% |

| 55+ | 10 | 2% |

| Educational level | ||

| High School | ||

| Associate Degree | 67 | 16% |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 79 | 19% |

| Master’s Degree | 150 | 36% |

| Doctorate/PhD | 50 | 12% |

| Other | 10 | 2% |

| Model Construct | Loadings (λ) | CA (α) | Rho-A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Innovation Depth | 0.889 | 0.904 | 0.923 | 0.752 | |

| OID1 | 0.782 | ||||

| OID2 * | |||||

| OID3 | 0.896 | ||||

| OID4 | 0.843 | ||||

| OID5 | 0.938 | ||||

| Open Innovation Breadth | 0.884 | 0.901 | 0.920 | 0.743 | |

| OIB1 | 0.892 | ||||

| OIB2 * | |||||

| OIB3 | 0.782 | ||||

| OIB4 | 0.871 | ||||

| OIB5 | 0.899 | ||||

| Organizational Resilience | 0.867 | 0.878 | 0.905 | 0.657 | |

| OR1 | 0.722 | ||||

| OR2 | 0.749 | ||||

| OR3 | 0.894 | ||||

| OR4 | 0.863 | ||||

| OR5 | 0.813 | ||||

| Sustainability Performance | 0.912 | 0.943 | 0.944 | 0.849 | |

| SP1 | 0.929 | ||||

| SP2 | 0.916 | ||||

| SP3 | 0.919 | ||||

| SP4 ** | |||||

| SP5 * | |||||

| Organizational Adaptability | 0.903 | 0.903 | 0.932 | 0.775 | |

| OA1 | 0.891 | ||||

| OA2 | 0.891 | ||||

| OA3 * | |||||

| OA4 | 0.837 | ||||

| OA5 | 0.901 |

| Variables | OA | OIB | OID | OR | SP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Adaptability (OA) | 0.880 | ||||

| Open Innovation Breadth (OIB) | 0.541 | 0.862 | |||

| Open Innovation Depth (OID) | 0.441 | 0.737 | 0.867 | ||

| Organizational Resilience (OR) | 0.860 | 0.508 | 0.460 | 0.811 | |

| Sustainability Performance (SP) | 0.425 | 0.497 | 0.616 | 0.507 | 0.921 |

| Indicators | VIF |

|---|---|

| OA1 | 2.755 |

| OA2 | 3.074 |

| OA4 | 2.059 |

| OA5 | 3.197 |

| OIB1 | 4.108 |

| OIB3 | 1.975 |

| OIB4 | 2.600 |

| OIB5 | 3.691 |

| OID1 | 2.071 |

| OID3 | 3.540 |

| OID4 | 2.290 |

| OID5 | 4.499 |

| OR1 | 1.668 |

| OR2 | 1.754 |

| OR3 | 2.946 |

| OR4 | 3.757 |

| OR5 | 2.979 |

| SP1 | 4.159 |

| SP2 | 3.717 |

| SP3 | 2.500 |

| Hypotheses | β | STDEV | T-Value | p-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | |||||

| H1a: OIB → OR | −0.022 | 0.033 | 0.675 | 0.250 | Not supported |

| H1b: OID → OR | 0.106 | 0.040 | 2.609 | 0.005 | Supported |

| H2a: OIB → SP | 0.091 | 0.043 | 2.130 | 0.017 | Supported |

| H2b: OID → SP | 0.550 | 0.050 | 11.105 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3a: OIB → OA | 0.472 | 0.063 | 7.446 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3b: OID → OA | 0.093 | 0.067 | 1.383 | 0.083 | Not supported |

| H4: OA → OR | 0.825 | 0.015 | 53.355 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Indirect effect (Mediation) | |||||

| H5a: OIB → OA → OR | 0.389 | 0.055 | 7.079 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5b: OID → OA → OR | 0.077 | 0.055 | 1.396 | 0.081 | Not supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saemaldaher, K.; Emeagwali, O.L. The Role of Open Innovation in Enhancing Organizational Resilience and Sustainability Performance Through Organizational Adaptability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135846

Saemaldaher K, Emeagwali OL. The Role of Open Innovation in Enhancing Organizational Resilience and Sustainability Performance Through Organizational Adaptability. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135846

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaemaldaher, Kinda, and Okechukwu Lawrence Emeagwali. 2025. "The Role of Open Innovation in Enhancing Organizational Resilience and Sustainability Performance Through Organizational Adaptability" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135846

APA StyleSaemaldaher, K., & Emeagwali, O. L. (2025). The Role of Open Innovation in Enhancing Organizational Resilience and Sustainability Performance Through Organizational Adaptability. Sustainability, 17(13), 5846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135846