Telework for a Sustainable Future: Systematic Review of Its Contribution to Global Corporate Sustainability (2020–2024)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Evolutionary Background and Theoretical Foundations

1.2. Dimensional Framework of Sustainability

1.2.1. Environmental Dimension

1.2.2. Social Dimension

1.2.3. Economic Dimension

1.3. Theoretical Integration and Empirical Convergence

2. Materials and Methods

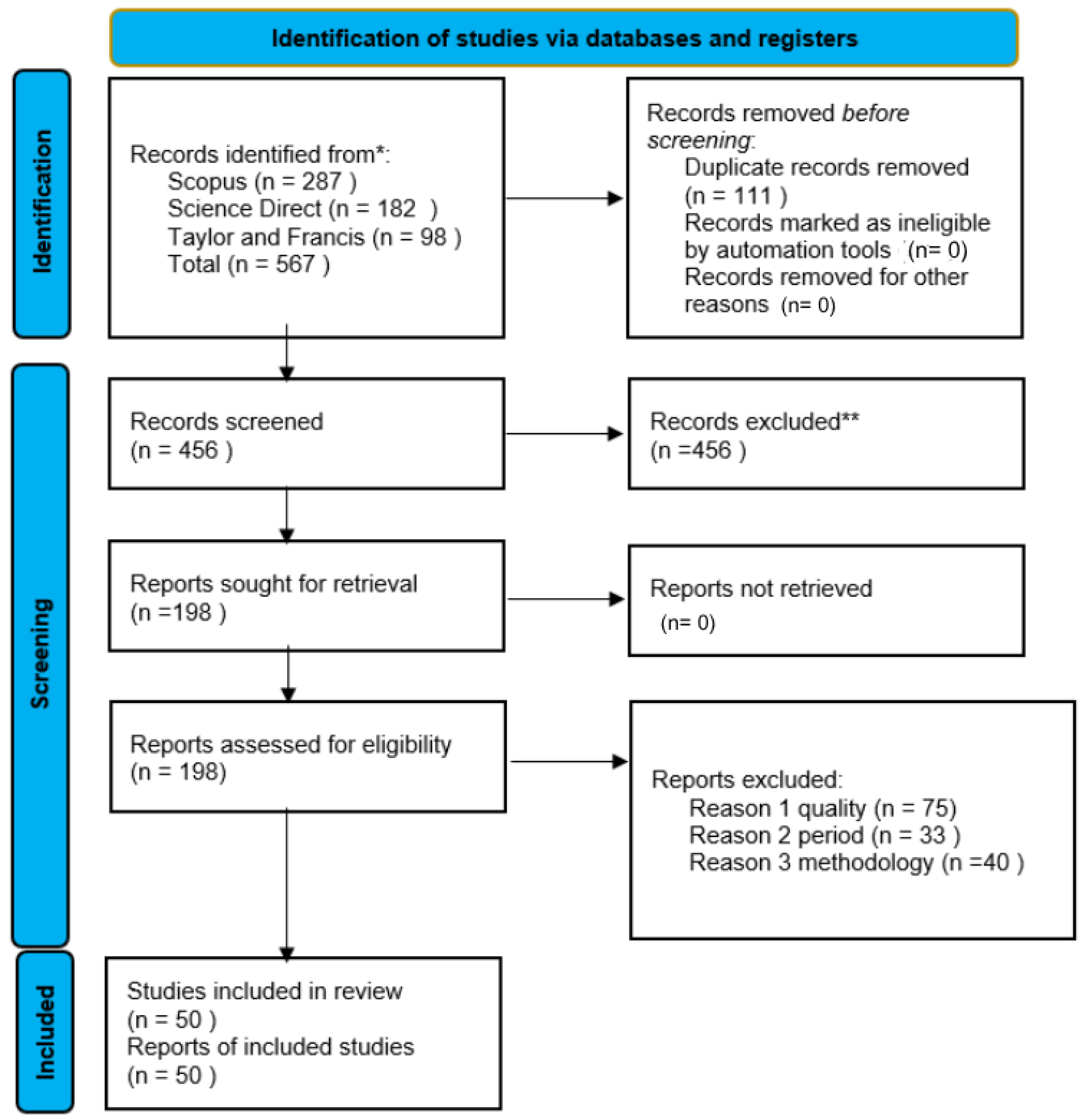

2.1. Systematic Review Design

2.2. Search Strategy and Database Selection

- Scopus: Selected for its broad and multidisciplinary coverage, with access to highly impactful journals in key areas—environmental, business, and social sciences in particular.

- Science Direct: Considered for its specialization in the literature with particular strength in sustainability and business management.

- Taylor and Francis Online: Chosen for its recognized coverage in social sciences and organizational studies, crucial for understanding the dimensions of work-from-home society.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Selection Process

Quality Assessment and Consensus Process

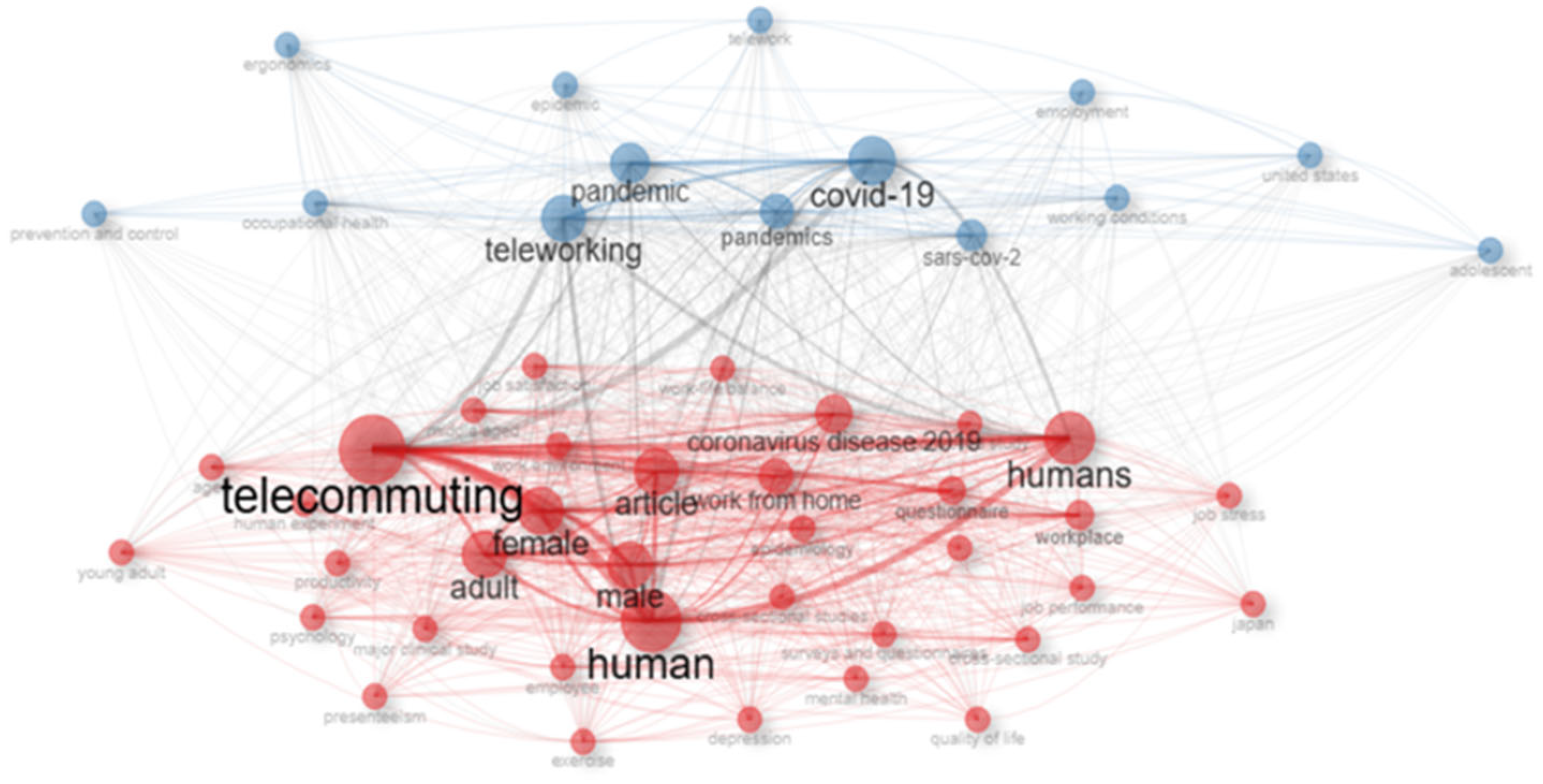

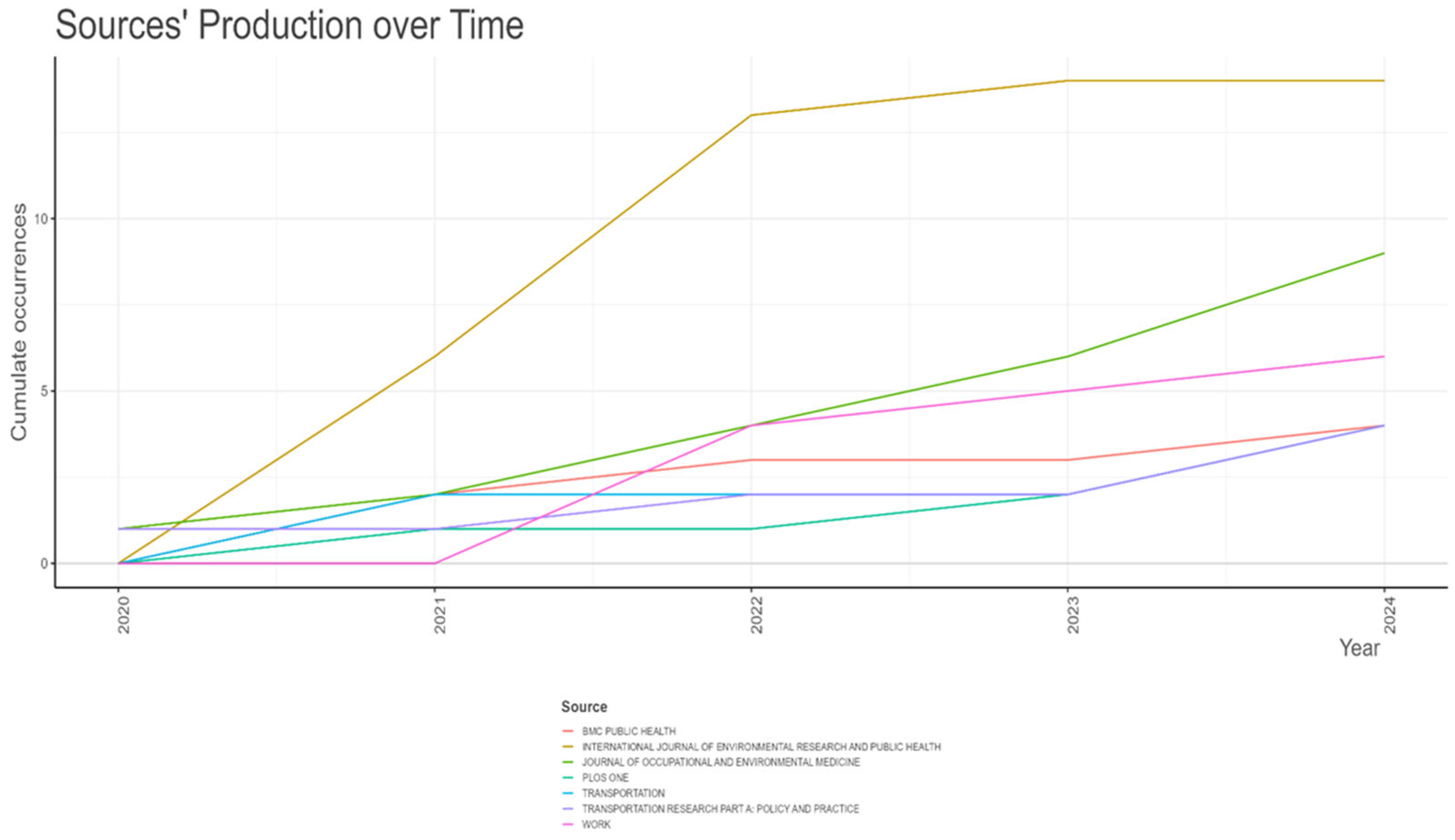

2.5. Bibliometric Analysis

2.5.1. Software and Tools

2.5.2. Analytical Framework

- Performance analysis: Quantitative assessment of scientific production by country, institution, journal, and temporal trends to identify research productivity patterns and influential sources.

- Science mapping: Network analysis of co-authorship patterns, institutional collaborations, and country-level research partnerships to reveal knowledge production structures and international cooperation dynamics.

- Thematic analysis: Co-occurrence analysis of author keywords and index terms to identify core themes, emerging topics, and conceptual evolution within the research domain.

- Impact assessment: Citation analysis and h-index calculations to evaluate research influence and identify highly cited contributions that have shaped the field.

2.5.3. Quality Assurance

2.6. Synthesis of Results

- Environmental dimension (23 studies): Focused on carbon emissions, energy consumption, mobility, and space use.

- Social dimension (17 studies): Focused on work well-being, work–life balance, inclusion, and equity.

- Economic dimension (10 studies): Oriented towards productivity, operational costs, innovation, and organizational resilience.

| Region | Environmental Dimension | Social Dimension | Economic Dimension | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | 9 | 6 | 4 | 19 |

| North America | 7 | 5 | 3 | 15 |

| Asia-Pacific | 4 | 3 | 2 | 9 |

| Latin America | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Africa | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 23 | 17 | 10 | 50 |

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Included Studies

3.1.1. Temporal Distribution

3.1.2. Geographic Concentration

| # | Obj | Rob | Authors | Year | Cultural Context | Study Type | Variables Studied | Objectives | Main Findings | Measurement Tools | Limitations | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | A | Caulfield, B.; Charly, A. [1] | 2022 | Ireland/Europe | Quantitative | Environmental benefits and travel time saved by telework | Examine potential benefits of remote working hubs | Remote hubs can reduce travel time | Transport policy analysis | Not specified | Remote working hubs offer time and environmental benefits |

| 2 | 1 | A | Victoriano-Habit, R.; El-Geneidy, A. [2] | 2024 | Canada/North America | Longitudinal/panel | Public transport usage patterns (2019–2022) | Analyze changes in public transport use post-COVID-19 | Sustained decrease in public transport use | Longitudinal panel study | Not specified | COVID-19 caused lasting changes in mobility patterns |

| 3 | 3 | M | Athanasiadou, C.; Theriou, G. [3] | 2021 | Greece/Europe | Systematic review | Telework literature | Systematically review telework literature | Identification of gaps and future research agenda | Systematic literature review | Disciplinary fragmentation | Need for integrated theoretical frameworks |

| 4 | 2 | Ac | Gibson, C.B.; Gilson, L.L.; Griffith, T.L.; O’Neill, T.A. [4] | 2023 | USA/North America | Conceptual | Return-to-office policies | Evaluate whether employees should return to office | Hybrid model as optimal solution | Organizational conceptual framework | Not specified | Flexibility is key for future of work |

| 5 | 1 | A | Sweet, M.; Scott, D.M. [5] | 2022 | Canada/North America | Predictive modeling | Future trajectory of telework | Model telework evolution post-pandemic | Telework will remain at elevated levels | Statistical trajectory models | Long-term prediction uncertainty | Telework will be permanent feature |

| 6 | 2 | M | Barbour, N.; Menon, N.; Mannering, F. [6] | 2021 | USA/North America | Quantitative/statistical | Work-from-home participation during COVID-19 | Evaluate WFH participation in different pandemic stages | Significant variation by pandemic stages | Multivariate statistical analysis | Cross-sectional data limitations | WFH varies by demographic and temporal characteristics |

| 7 | 3 | M | Benita, F. [7] | 2021 | International/Global | Bibliometric review | Human mobility behavior during COVID-19 | Systematically analyze literature on COVID-19 mobility | Dramatic reduction in urban mobility | Bibliometric analysis | Geographic concentration of studies | COVID-19 transformed mobility patterns globally |

| 8 | 1 | A | Li, W.; Zhang, E.; Long, Y. [8] | 2024 | China/Asia-Pacific | Big Data/quantitative | Urban third places for remote work | Identify urban places for remote work using big data | Identification of emerging workspaces | Mobile phone big data | Data privacy and representativeness | Urban spaces adapt to remote work |

| 9 | 2 | Ac | Gaspar, T.; Jesus, S.; Farias, A.R.; Matos, M.G. [9] | 2024 | Portugal/Europe | Conceptual | Healthy work environment ecosystems for telework | Define frameworks for healthy work environments | Need for ecosystemic approaches | Multidimensional conceptual framework | Not specified | Occupational health requires integral approaches |

| 10 | 1 | A | Rüger, H.; Laß, I.; Stawarz, N.; Mergener, A. [10] | 2024 | Australia/Oceania | Longitudinal panel | Commuting time savings from WFH | Quantify time savings from working from home | Significant commuting time savings | HILDA Survey panel | Individual variability | WFH generates substantial time savings |

| 11 | 1 | A | Wang, K.; Ozbilen, B. [11] | 2020 | USA/North America | Quantitative | Synergistic effects of telework and residential location | Analyze telework–location interactions in time allocation | Threshold effects in travel time allocation | Structural equation analysis | Causality and omitted variables | Telework and location have complex effects |

| 12 | 1 | M | Ceccato, R.; Baldassa, A.; Rossi, R.; Gastaldi, M. [12] | 2022 | Italy/Europe | Case study | Long-term effects of COVID-19 on telecommuting | Evaluate potential long-term effects in Italy | Potential reduction in transport emissions | Scenario analysis | Generalization to other contexts | Telecommuting may have lasting environmental benefits |

| 13 | 1 | M | Cerqueira, E.D.V.; Motte-Baumvol, B.; Chevallier, L.B.; Bonin, O. [13] | 2020 | France/Europe | Quantitative | CO2 emissions and travel patterns from WFH | Analyze whether WFH reduces CO2 emissions | Emission reduction depends on specific travel patterns | Travel pattern analysis | Rebound effects not considered | WFH can reduce CO2 under certain conditions |

| 14 | 1 | M | Motte-Baumvol, B.; Schwanen, T.; Bonin, O. [14] | 2024 | France/Europe | Quantitative | Daily variability of travel behavior | Examine Friday specificities in telework | Fridays show unique mobility patterns | Travel behavior analysis | Generalization to other days | Telework patterns vary by day of week |

| 15 | 2 | A | Asmussen, K.E.; Mondal, A.; Batur, I.; Dirks, A.; Pendyala, R.M.; Bhat, C.R. [16] | 2024 | USA/North America | Quantitative | Individual telework arrangements in COVID-19 era | Investigate individual-level telework arrangements | Heterogeneity in telework adoption | Discrete choice models | Causality and selection | Telework varies by individual and employment characteristics |

| 16 | 1 | M | Fabiani, C.; Longo, S.; Pisello, A.L.; Cellura, M. [17] | 2021 | Italy/Europe | Mixed methods | Sustainable production and consumption in remote work | Investigate environmental aspects and user acceptance | Potential for more sustainable consumption but with trade-offs | Life cycle analysis and surveys | Sample representativeness | Remote work has sustainable potential with conditions |

| 17 | 1 | M | Chuang, Y.-T.; Chiang, H.-L.; Lin, A.-P. [18] | 2024 | Taiwan/Asia-Pacific | Quantitative | Information quality, work–family conflict, loneliness | Examine well-being factors in remote work | Information quality significantly affects well-being | Validated psychometric scales | Self-report bias | Information quality is critical for remote well-being |

| 18 | 1 | M | Bouzaghrane, M.A.; Obeid, H.; Villas-Boas, S.B.; Walker, J. [19] | 2024 | USA/North America | Quantitative | Telecommuting influence on out-of-home time use | Analyze telecommuting effects on location diversity | Telecommuting affects spatial activity patterns | Time and space use analysis | Causality and unobserved variables | Telecommuting reduces diversity of visited locations |

| 19 | 2 | M | Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Navas-Martín, M.Á.; March, S.; Oteiza, I. [20] | 2021 | Spain/Europe | Quantitative | Adequacy of telework spaces in homes | Evaluate adequacy of domestic spaces for telework | Significant inequalities by socioeconomic factors | Surveys and spatial analysis | Limited geographic representativeness | Inadequate telework spaces aggravate inequalities |

| 20 | 1 | M | Norouziasas, A.; Attia, S.; Hamdy, M. [21] | 2024 | Belgium/Europe | Simulation | Impact of space utilization on energy performance | Analyze work time flexibility on energy efficiency | Temporal flexibility can optimize energy use | Building simulations | Generalization to other building types | Temporal flexibility improves energy efficiency |

| 21 | 2 | M | Anik, M.A.H.; Khan, N.A.; Habib, M.A. [23] | 2024 | Bangladesh/Asia-Pacific | Integrated modeling | Interaction between work arrangements, location, and activities | Map interactions in integrated model | Complex interactions between variables | Integrated multivariate models | Model complexity | Work arrangements have systemic effects |

| 22 | 2 | Ac | Kraus, S.; Ferraris, A.; Bertello, A. [24] | 2023 | International/Europe | Conceptual | Future of work and digital innovation | Analyze how innovation reshapes workplaces | Digitalization fundamentally transforms work | Conceptual framework | Not specified | Digital transformation is irreversible |

| 23 | 3 | Ac | Guerin, T.F. [25] | 2021 | Australia/Oceania | Policy analysis | Policies to minimize environmental effects of telework | Develop policies to optimize environmental benefits | Need for specific anti-rebound policies | Public policy analysis | Uncertain practical implementation | Public policies essential for maximizing benefits |

| 24 | 3 | M | O’Brien, W.; Yazdani Aliabadi, F. [26] | 2020 | Canada/North America | Critical review | Energy savings from telecommuting | Critically review studies on energy savings | Mixed results and inconsistent methodologies | Critical methods review | Methodological heterogeneity | Need for better energy evaluation methods |

| 25 | 3 | M | Santana, M.; Cobo, M.J. [27] | 2020 | Spain/Europe | Science mapping | Future of work—bibliometric analysis | Scientifically map the future of work | Identification of emerging trends | Bibliometric analysis | Publication bias | Field is rapidly evolving |

| 26 | 2 | Ac | Asatiani, A.; Norström, L. [28] | 2023 | Finland/Europe | Conceptual | Information systems for sustainable remote workplaces | Develop IS frameworks for sustainable remote work | IS are critical for remote work sustainability | IS conceptual framework | Not specified | Technology is sustainability enabler |

| 27 | 1 | M | Salon, D.; Mirtich, L.; et al [29] | 2022 | USA/North America | Mixed methods | COVID-19 pandemic and future of telecommuting | Analyze pandemic effects on future telecommuting | Lasting changes in work patterns | Surveys and statistical analysis | Predictive uncertainty | Telecommuting will persist post-pandemic |

| 28 | 1 | A | Behrens, K.; Kichko, S.; Thisse, J.-F. [30] | 2024 | Europe/Theoretical | Theoretical modeling | Spatial economic effects of working from home | Model spatial economic impacts | Non-linear effects and critical thresholds | Spatial economic models | Simplifying assumptions | WFH can have “too much of a good thing” |

| 29 | 2 | Ac | Mora, L.; Kummitha, R.K.R.; Esposito, G. [31] | 2021 | International/Global | Conceptual | Digital technology affordances in pandemic control | Examine socio-material mediation in technology | Socio-material arrangements mediate technological effects | Affordances framework | Not specified | Technology is not deterministic but mediated |

| 30 | 2 | Ac | Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A. [32] | 2020 | Spain/Europe | Conceptual | Telework in COVID-19 crisis context | Analyze telework during COVID-19 crisis | Telework became a necessity, not an option | Conceptual analysis | Not specified | COVID-19 transformed telework perception |

| 31 | 2 | Ac | Green, N.; Tappin, D.; Bentley, T. [33] | 2020 | New Zealand/Oceania | Conceptual | Working from home before, during, and after COVID-19 | Analyze implications for workers and organizations | Need for more strategic approaches | Temporal conceptual framework | Not specified | Transition requires strategic planning |

| 32 | 1 | A | Abrardi, L.; Grinza, E.; Manello, A.; Porta, F. [34] | 2024 | Italy/Europe | Quantitative | WFH arrangements and organizational performance in SMEs | Examine effects on organizational performance | Positive effects on productivity under certain conditions | Econometric analysis | Causality and selection | WFH can improve SME performance |

| 33 | 2 | M | Waizenegger, L.; McKenna, B.; Cai, W.; Bendz, T. [41] | 2020 | International/Europe | Qualitative | Team collaboration and enforced working from home | Analyze collaboration from affordances perspective | Technological affordances facilitate but also limit | Qualitative affordances analysis | Limited generalization | Technology enables but does not guarantee collaboration |

| 34 | 3 | Ac | Hodder, A. [35] | 2020 | UK/Europe | Reflective conceptual | New technology, work, and employment in COVID-19 era | Reflect on research legacies | Need for new theoretical frameworks | Conceptual reflection | Not specified | Field needs theoretical renewal |

| 35 | 2 | M | López-Igual, P.; Rodríguez-Modroño, P. [36] | 2020 | Europe/Regional | Quantitative | Main determinants of telework in Europe | Explore telework determining factors | Significant inequalities by countries and sectors | Multivariate statistical analysis | Omitted variables | Telework reproduces structural inequalities |

| 36 | 2 | M | Boons, F.; Doherty, B.; et al. [40] | 2021 | UK/Europe | Qualitative modeling | Disruptive impact of COVID-19 on mobility transitions | Qualitatively model COVID-19 disruptions | COVID-19 accelerated transitions toward sustainability | Qualitative modeling | Causal complexity | Crises can accelerate sustainable transitions |

| 37 | 3 | Ac | Vasseur, V.; Backhaus, J.; et al. [42] | 2024 | Netherlands/Europe | Conceptual | Capabilities and social practices in domestic energy use | Develop combined conceptual framework | Integration of capabilities and practices better explains behavior | Integrated conceptual framework | Not specified | Energy behavior requires multi-theoretical approaches |

| 38 | 3 | M | Wright, C.; Nyberg, D. [54] | 2024 | International/Global | Review | Corporations and climate change | Provide overview of corporations–climate relationship | Critical but ambivalent role of corporations | Literature review | Not specified | Corporations are part of problem and solution |

| 39 | 3 | Ac | Fankhauser, S.; Smith, S.M.; et al. [55] | 2022 | International/Global | Conceptual | Meaning of net zero | Clarify net-zero concept | Need for clear and consistent definitions | Conceptual analysis | Not specified | Net zero requires conceptual clarity |

| 40 | 3 | A | Hook, A.; Court, V.; Sovacool, B.K.; Sorrell, S. [43] | 2020 | International/Global | Systematic review | Energy and climate impacts of teleworking | Systematically review energy impacts | Variable effects and context-dependent | Systematic review | Study heterogeneity | Energy impacts are complex and contextual |

| 41 | 1 | M | Raj, R.; Kumar, V.; et al. [38] | 2023 | India/Asia-Pacific | Quantitative | Remote work outcomes on business performance | Study influence on firm performance | Remote work can improve performance under conditions | Statistical analysis | Causality and omitted variables | Remote work has positive potential in emerging economies |

| 42 | 1 | M | Maipas, S.; Panayiotides, I.G.; Kavantzas, N. [44] | 2021 | Greece/Europe | Quantitative | Remote working carbon-saving footprint | Evaluate if COVID-19 established environmentally positive work model | Significant carbon reduction potential | Carbon footprint analysis | Rebound effects not considered | Remote work may have lasting environmental benefits |

| 43 | 3 | A | Charalampous, M.; Grant, C.; et al. [45] | 2021 | International/Europe | Systematic review | Well-being of remote e-workers | Systematically review well-being in remote work | Multidimensional approach necessary for evaluating well-being | Multidimensional systematic review | Heterogeneity of measures | Remote well-being is multifaceted |

| 44 | 3 | M | Oakman, J.; Kinsman, N.; et al. [46] | 2020 | Australia/Oceania | Rapid review | Mental and physical health effects of working from home | Rapidly review health effects | Mixed effects require optimization of conditions | Rapid literature review | Temporal limitations of review | Working from home requires optimal conditions for health |

| 45 | 1 | M | Kazekami, S. [47] | 2020 | Japan/Asia-Pacific | Quantitative | Mechanisms to improve labor productivity by telework | Identify productivity improvement mechanisms | Telework can improve productivity under certain conditions | Productivity analysis | Omitted variables | Productivity depends on specific conditions |

| 46 | 1 | A | Barrero, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. [48] | 2021 | USA/North America | Economic/quantitative | Why working from home will stick | Analyze WFH persistence | WFH will generate lasting economic value | Economic analysis | Predictive uncertainty | WFH is a permanent structural change |

| 47 | 1 | A | Delventhal, M.; Parkhomenko, A. [56] | 2024 | USA/North America | Spatial modeling | Spatial implications of telecommuting | Model urban spatial effects | Significant spatial redistribution of economic activity | Spatial economic models | Simplifying assumptions | Telecommuting reshapes economic geography |

| 48 | 1 | M | Aldieri, L.; Brahmi, M.; et al. [57] | 2021 | Italy/Europe | Quantitative | Circular economy business models | Examine complementarities with sharing economy | Synergy between circular economy and remote work | Statistical analysis | Causality | Circular economy benefits from remote work |

| 49 | 1 | M | Blak Bernat, G.; Qualharini, E.L.; et al. [53] | 2023 | Brazil/Latin America | Quantitative | Sustainability in project management with virtual teams | Analyze sustainability in virtual projects | Virtual teams can be more sustainable | Quantitative analysis | Limited generalization | Virtualization improves project sustainability |

| 50 | 2 | M | van der Lippe, T.; Lippényi, Z. [39] | 2020 | Europe/Regional | Quantitative | Formal access, organizational context, and work–family conflict | Examine WFH and work–family conflict in Europe | Organizational context moderates WFH effects | Multilevel analysis | Omitted variables | Organizational context is critical |

3.2. Critical Interpretation of Bibliometric Analysis

3.3. Methodological Integration and Triangulation of Findings

3.3.1. Quantitative Studies: Statistical Validation and Measurable Impacts

3.3.2. Qualitative Studies: Contextual Understanding and Mechanism Elucidation

3.3.3. Mixed-Methods Studies: Bridging Quantitative Measures with Qualitative Insights

3.3.4. Systematic Reviews: Meta-Analytical Context and Knowledge Synthesis

3.3.5. Methodological Triangulation and Convergent Validity

3.3.6. Critical Synthesis of Emerging Patterns

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Causal Mechanisms and Rebound Effects

4.2. Geographic Limitations and Interpretation Strategies

4.3. Implications for Professional Practice: Evidence-Based Implementation Strategies

4.4. Critical Analysis of Multidimensional Sustainability Impacts

4.5. Social Equity and Contextual Dependencies

4.6. Methodological Evolution and Persistent Limitations

4.7. Theoretical Implications and Future Directions

4.8. Study Limitations and Implications

4.9. Implications for Theory and Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caulfield, B.; Charly, A. Examining the Potential Environmental and Travel Time Saved Benefits of Remote Working Hubs. Transp. Policy 2022, 127, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victoriano-Habit, R.; El-Geneidy, A. Why Are People Leaving Public Transport? A Panel Study of Changes in Transit-Use Patterns between 2019, 2021, and 2022 in Montréal, Canada. J. Public Transp. 2024, 26, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiadou, C.; Theriou, G. Telework: Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, C.B.; Gilson, L.L.; Griffith, T.L.; O’Neill, T.A. Should Employees Be Required to Return to the Office? Organ. Dyn. 2023, 52, 100981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, M.; Scott, D.M. Insights into the Future of Telework in Canada: Modeling the Trajectory of Telework across a Pandemic. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87, 104175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, N.; Menon, N.; Mannering, F. A Statistical Assessment of Work-from-Home Participation during Different Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 11, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benita, F. Human Mobility Behavior in COVID-19: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70, 102916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhang, E.; Long, Y. Unveiling Fine-Scale Urban Third Places for Remote Work Using Mobile Phone Big Data. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 103, 105258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, T.; Jesus, S.; Farias, A.R.; Matos, M.G. Healthy Work Environment Ecosystems for Teleworking and Hybrid Working. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 239, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüger, H.; Laß, I.; Stawarz, N.; Mergener, A. To What Extent Does Working from Home Lead to Savings in Commuting Time? A Panel Analysis Using the Australian HILDA Survey. Travel Behav. Soc. 2024, 37, 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ozbilen, B. Synergistic and Threshold Effects of Telework and Residential Location Choice on Travel Time Allocation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 63, 102468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, R.; Baldassa, A.; Rossi, R.; Gastaldi, M. Potential Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 on Telecommuting and Environment: An Italian Case-Study. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 109, 103401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, E.D.V.; Motte-Baumvol, B.; Chevallier, L.B.; Bonin, O. Does Working from Home Reduce CO2 Emissions? An Analysis of Travel Patterns as Dictated by Workplaces. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 83, 102338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motte-Baumvol, B.; Schwanen, T.; Bonin, O. Telework and the Day-to-Day Variability of Travel Behaviour: The Specificities of Fridays. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 132, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sang, X.; Yang, W.; Luo, X. Empowering Household Energy Transition: The Impact of Digital Economy on Clean Energy Use in Rural China. Energy 2025, 324, 136016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmussen, K.E.; Mondal, A.; Batur, I.; Dirks, A.; Pendyala, R.M.; Bhat, C.R. An Investigation of Individual-Level Telework Arrangements in the COVID-Era. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 179, 103888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, C.; Longo, S.; Pisello, A.L.; Cellura, M. Sustainable Production and Consumption in Remote Working Conditions Due to COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy: An Environmental and User Acceptance Investigation. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 1757–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.-T.; Chiang, H.-L.; Lin, A.-P. Information Quality, Work-Family Conflict, Loneliness, and Well-Being in Remote Work Settings. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 154, 108149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzaghrane, M.A.; Obeid, H.; Villas-Boas, S.B.; Walker, J. Influence of Telecommuting on Out-of-Home Time Use and Diversity of Locations Visited: Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 190, 104276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Navas-Martín, M.Á.; March, S.; Oteiza, I. Adequacy of Telework Spaces in Homes during the Lockdown in Madrid, According to Socioeconomic Factors and Home Features. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouziasas, A.; Attia, S.; Hamdy, M. Impact of Space Utilization and Work Time Flexibility on Energy Performance of Office Buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurizio, R. Desafíos y Oportunidades del Teletrabajo en América Latina y el Caribe; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/es/publications/desafios-y-oportunidades-del-teletrabajo-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Anik, M.A.H.; Khan, N.A.; Habib, M.A. Mapping the Interplay of Work-Arrangement, Residential Location, and Activity Engagement within an Integrated Model. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 190, 104294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Ferraris, A.; Bertello, A. The Future of Work: How Innovation and Digitalization Re-Shape the Workplace. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin, T.F. Policies to Minimise Environmental and Rebound Effects from Telework: A Study for Australia. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 39, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, W.; Yazdani Aliabadi, F. Does Telecommuting Save Energy? A Critical Review of Quantitative Studies and Their Research Methods. Energy Build. 2020, 225, 110298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, M.; Cobo, M.J. What Is the Future of Work? A Science Mapping Analysis. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 846–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatiani, A.; Norström, L. Information Systems for Sustainable Remote Workplaces. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2023, 32, 101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salon, D.; Mirtich, L.; Bhagat-Conway, M.W.; Costello, A.; Rahimi, E.; Mohammadian, A.K.; Chauhan, R.S.; Derrible, S.; da Silva Baker, D.; Pendyala, R.M. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Future of Telecommuting in the United States. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 112, 103473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, K.; Kichko, S.; Thisse, J.-F. Working from Home: Too Much of a Good Thing? Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2024, 105, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, L.; Kummitha, R.K.R.; Esposito, G. Not Everything Is as It Seems: Digital Technology Affordance, Pandemic Control, and the Mediating Role of Sociomaterial Arrangements. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A. Teleworking in the Context of the COVID-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, N.; Tappin, D.; Bentley, T. Working From Home Before, During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for Workers and Organisations. N. Z. J. Employ. Relat. 2020, 45, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrardi, L.; Grinza, E.; Manello, A.; Porta, F. Work from Home Arrangements and Organizational Performance in Italian SMEs: Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Empir. Econ. 2024, 67, 2821–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, A. New Technology, Work and Employment in the Era of COVID-19: Reflecting on Legacies of Research. New Technol. Work Employ. 2020, 35, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Igual, P.; Rodríguez-Modroño, P. Who Is Teleworking and Where from? Exploring the Main Determinants of Telework in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Muff, K. Clarifying the Meaning of Sustainable Business: Introducing a Typology From Business-as-Usual to True Business Sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, R.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, N.K.; Singh, S.; Mahlawat, S.; Verma, P. The Study of Remote Working Outcome and Its Influence on Firm Performance. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 8, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Lippe, T.; Lippényi, Z. Beyond Formal Access: Organizational Context, Working From Home, and Work-Family Conflict of Men and Women in European Workplaces. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 151, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Doherty, B.; Köhler, J.; Papachristos, G.; Wells, P. Disrupting Transitions: Qualitatively Modelling the Impact of COVID-19 on UK Food and Mobility Provision. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 40, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waizenegger, L.; McKenna, B.; Cai, W.; Bendz, T. An Affordance Perspective of Team Collaboration and Enforced Working from Home during COVID-19. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasseur, V.; Backhaus, J.; Fehres, S.; Goldschmeding, F. Capabilities and Social Practices: A Combined Conceptual Framework for Domestic Energy Use. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 455, 142268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, A.; Court, V.; Sovacool, B.K.; Sorrell, S. A Systematic Review of the Energy and Climate Impacts of Teleworking. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 093003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maipas, S.; Panayiotides, I.G.; Kavantzas, N. Remote-Working Carbon-Saving Footprint: Could COVID-19 Pandemic Establish a New Working Model with Positive Environmental Health Implications? Environ. Health Insights 2021, 15, 11786302211013546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charalampous, M.; Grant, C.; Tramontano, C.; Michailidis, E. Systematically Reviewing Remote E-Workers’ Well-Being at Work: A Multidimensional Approach. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2021, 28, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakman, J.; Kinsman, N.; Stuckey, R.; Graham, M.; Weale, V. A Rapid Review of Mental and Physical Health Effects of Working at Home: How Do We Optimise Health? BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazekami, S. Mechanisms to Improve Labor Productivity by Performing Telework. Telecommun. Policy 2020, 44, 101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. Why Working from Home Will Stick; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J.; López-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. Science Mapping Software Tools: Review, Analysis, and Cooperative Study among Tools. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 1382–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blak Bernat, G.; Qualharini, E.L.; Castro, M.S.; Barcaui, A.B.; Soares, R.R. Sustainability in Project Management and Project Success with Virtual Teams: A Quantitative Analysis Considering Stakeholder Engagement and Knowledge Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Nyberg, D. Corporations and Climate Change: An Overview. WIREs Clim. Change 2024, 15, e919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fankhauser, S.; Smith, S.M.; Allen, M.; Axelsson, K.; Hale, T.; Hepburn, C.; Kendall, J.M.; Khosla, R.; Lezaun, J.; Mitchell-Larson, E.; et al. The Meaning of Net Zero and How to Get It Right. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delventhal, M.; Parkhomenko, A. Spatial Implications of Telecommuting. SSRN Electron. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldieri, L.; Brahmi, M.; Bruno, B.; Vinci, C.P. Circular Economy Business Models: The Complementarities with Sharing Economy and Eco-Innovations Investments. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitnis, M.; Fouquet, R.; Sorrell, S. Rebound Effects for Household Energy Services in the UK. Energy J. 2020, 41, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbosc, A.; Kent, J. Employee Intentions and Employer Expectations: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review of “Post-COVID” Intentions to Work from Home. Transp. Rev. 2024, 44, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, S.; Qin, P.; Wang, B. Spatial and Temporal Effects of Digital Technology Development on Carbon Emissions: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, J. Telework in the 21st Century; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; ISBN 978 1 78990 374 4. [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniec, A.; Brazil, W.; Whitney, W.; Zhang, W.; Colleary, B.; Caulfield, B. Examining the Long-Term Reduction in Commuting Emissions from Working from Home. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 127, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Papagiannakis, A. COVID-19, Internet, and Mobility: The Rise of Telework, Telehealth, e-Learning, and e-Shopping. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept Block | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Telework | “telework” OR “remote work” OR “work from home” OR “telecommut” OR “virtual work” OR “distributed work” OR “flexible work” OR “home office” |

| Sustainability | “sustainab” OR “environment” OR “carbon footprint” OR “emission” OR “energy” OR “ESG” OR “triple bottom line” OR “social” OR “wellbeing” OR “economic” OR “resilien” OR “SDG” |

| Corporate scope | “corporat” OR “organization” OR “business” OR “enterprise” OR “company” OR “companies” OR “firm” OR “workplace” OR “institution” |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Studies published between January 2020 and February 2024 | Studies published outside the established period |

| Peer-reviewed scientific articles and working papers from recognized institutions | Opinion pieces, editorials, or communications without explicit methodology |

| Studies that explicitly analyze the relationship between teleworking and corporate sustainability | Studies focused exclusively on the technical aspects of teleworking |

| Publications in English or Spanish | Publications in other languages |

| Studies with verifiable and transparent methodology | Studies focused solely on the immediate impact of COVID-19 without prospective analysis |

| Methodological Approach | Number of Studies | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | 27 | 54% |

| Qualitative | 13 | 26% |

| Mixed methods | 7 | 14% |

| Systematic review | 3 | 6% |

| Total | 50 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ríos Villacorta, M.A.; Ramos Farroñán, E.V.; Alarcón García, R.E.; Castro Ijiri, G.L.; Bravo-Jaico, J.L.; Minchola Vásquez, A.M.; Ganoza-Ubillús, L.M.; Escobedo Gálvez, J.F.; Ríos Yovera, V.R.; Durand Gonzales, E.J. Telework for a Sustainable Future: Systematic Review of Its Contribution to Global Corporate Sustainability (2020–2024). Sustainability 2025, 17, 5737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135737

Ríos Villacorta MA, Ramos Farroñán EV, Alarcón García RE, Castro Ijiri GL, Bravo-Jaico JL, Minchola Vásquez AM, Ganoza-Ubillús LM, Escobedo Gálvez JF, Ríos Yovera VR, Durand Gonzales EJ. Telework for a Sustainable Future: Systematic Review of Its Contribution to Global Corporate Sustainability (2020–2024). Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135737

Chicago/Turabian StyleRíos Villacorta, Mauro Adriel, Emma Verónica Ramos Farroñán, Roger Ernesto Alarcón García, Gabriela Lizeth Castro Ijiri, Jessie Leila Bravo-Jaico, Angélica María Minchola Vásquez, Lucila María Ganoza-Ubillús, José Fernando Escobedo Gálvez, Verónica Raquel Ríos Yovera, and Esteban Joaquín Durand Gonzales. 2025. "Telework for a Sustainable Future: Systematic Review of Its Contribution to Global Corporate Sustainability (2020–2024)" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135737

APA StyleRíos Villacorta, M. A., Ramos Farroñán, E. V., Alarcón García, R. E., Castro Ijiri, G. L., Bravo-Jaico, J. L., Minchola Vásquez, A. M., Ganoza-Ubillús, L. M., Escobedo Gálvez, J. F., Ríos Yovera, V. R., & Durand Gonzales, E. J. (2025). Telework for a Sustainable Future: Systematic Review of Its Contribution to Global Corporate Sustainability (2020–2024). Sustainability, 17(13), 5737. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135737