Abstract

China has made a major strategic decision to build world-class universities and first-class disciplines (abbreviation: Double First-Class), aimed at enhancing the global competitiveness of Chinese higher education. Industry-specific universities have a special historical evolution and distinctive characteristics. China’s industry-specific universities have always played an important role in the higher education system and made significant contributions to the development of the country. However, the “Double First-Class” initiative presents both opportunities and challenges for industry-specific universities. This paper employs the SWOT analysis method to conduct a qualitative analysis of industry-specific universities and proposes a strategic matrix for decision-making. At the same time, from a niche perspective, this paper explores the sustainable development strategies of these institutions within the initiative through the calculation of niche breadth, niche overlap, and their relationship analysis. The research results indicate that the “Double First-Class” initiative has played a positive role in promoting the expansion of universities’ ecological niches. However, it has also led to excessive niche overlap and intense competition. Industry-specific universities face opportunities and challenges in terms of structure, strategy, and policy for their sustainable development. Key findings highlight the importance of strategic alignment with national demand, industry cooperation, and policy orientation for sustainable growth. This paper proposes recommendations for the construction of a sustainable development framework, implementation of strategic initiatives, and policy guidance for universities with industrial characteristics from three perspectives: government, industry, and universities.

1. Introduction

The concept of “sustainable development” has garnered widespread global attention since its introduction in the 1990s. Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4), one of the 17 global goals established by the United Nations, focuses on “High-Quality Education”. It aims to promote global sustainable development by providing quality education [1]. Sustainable development in higher education adheres to the principles of sustainable development. It strives to build a lifelong learning society for all, promoting equitable and coordinated educational development. The goal is to enhance education’s contribution to societal sustainability and foster holistic human development [2]. In order to enhance the international competitiveness and influence in the field of education, countries around the world are committed to cultivating and building world-class higher education institutions in their own countries. Building “world-class universities and disciplines” is the key to improving the quality of higher education and promoting the sustainable development of higher education. World-class universities play a significant role in modernizing global politics, economics, culture, and history [3]. Numerous studies emphasize the importance of exploring world-class universities and disciplines for higher education sustainability [4].

In China, the purpose of the “world-class universities and first-class disciplines” initiative is to bring some universities and disciplines to a world-class level. These two aspects of excellence are commonly referred to as the “Double First-Class” plan by Chinese government departments and scholars in policy documents and research papers [5,6,7]. This concept was proposed by China after higher education entered the popularization stage to address the imbalances and inadequacies in the development of higher education. In China, “Double First-Class” is considered a key strategy for promoting high-quality learning outcomes in higher education. It aims to enhance the competitiveness and influence of Chinese universities on a global scale [8]. To further enhance higher education and transition from a large education provider to a powerful one, China initiated the strategic project of developing world-class universities and disciplines. This initiative aligns with national development needs and the current state of higher education. The “Double First-Class” initiative follows “Project 985” and “Project 211”, marking another significant development phase in Chinese higher education [9,10]. The report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China emphasized accelerating the development of world-class universities and disciplines with Chinese characteristics [11]. It explicitly called for advancing the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation through Chinese-style modernization. Education, science and technology, and talent development are integrated into strategic planning for the first time, serving the construction of an innovative nation. This integration holds significant practical relevance and far-reaching strategic implications.

Industry-specific universities in China hold a distinct position and significance within the national higher education system. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, these universities have made substantial contributions and provided strong support to both their respective industries and national development. Among the first batch of 137 universities selected for the “Double First-Class” initiative in 2017, around 30 universities, accounting for approximately 20% of the total, are focused on major industries such as mining, petroleum, geology, power, and transportation. If some other industries are included, this proportion can exceed 50% [12]. These universities have played a crucial role in China’s higher education system, both during the nation-building era and since the reform and opening-up period.

Education, science and technology, and talent are fundamental and strategic pillars for building a modern socialist country. China must thoroughly implement the strategies of rejuvenating the nation through science and education, strengthening the nation through talent, and driving development through innovation. This requires the accelerated development of a strong education system, a leading scientific and technological power, and a robust talent pool. Higher education must enhance its support for economic and social development, becoming an open system coupled with and interactive with the economy and industries. The implementation of national development strategies and the advancement of higher education reforms in the new era have set new demands and standards for industry-specific universities. Faced with these new circumstances, these universities must leverage their unique characteristics to seize opportunities for development and contribute significantly to national higher education and economic progress. Sustainable development in higher education requires diverse institutions with varying types, levels, and characteristics, forming a diversified and balanced ecosystem. A key question arises: how can industry-specific universities optimize their niche within the “Double First-Class” initiative to achieve high-quality sustainable development and contribute more effectively to socio-economic sustainability?

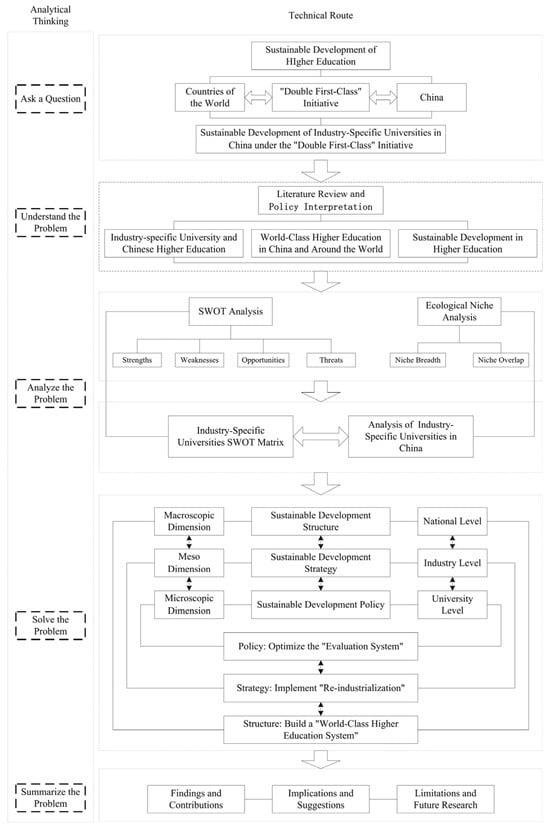

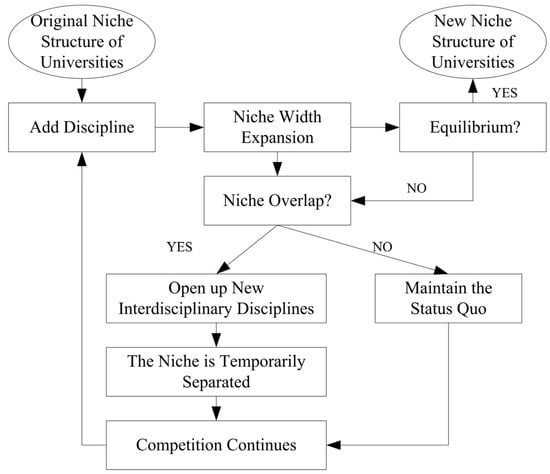

The main research content and technical road of this paper are shown in Figure 1. Part One presents the introduction. Part Two provides an overview of relevant literature and policies concerning industry-specific universities and Chinese higher education, world-class higher education in China and around the world, and sustainable development in higher education. Part Three introduces the SWOT analysis principles and operational procedures. It also establishes a calculation model for the sustainable development of industry-specific universities based on niche theory. Part Four discusses the challenges and opportunities of industry-specific universities under the “Double First-Class” initiative using SWOT analysis. From a niche perspective, it calculates niche breadth and niche overlap. It also conducts comparative analyses of the ecological niches of industry-specific universities at specific time points and carries out trend analyses over time series. The final part summarizes the research findings and proposes measures and recommendations for achieving the sustainable development of industry-specific universities.

Figure 1.

The research technical route.

2. Literature Review and Policy Interpretation

The integration of sustainable development into higher education has garnered significant attention in recent years, reflecting a growing recognition of the role that educational institutions play in fostering sustainability [13]. Various studies have explored the theory and practices regarding sustainable development, revealing both opportunities and challenges.

Research on “Double First-Class” universities and industry-specific universities is relatively abundant. Due to variations in historical periods, educational systems, and management structures, specialized institutions manifest differently across countries. Institutions similar to Chinese industry-specific universities exist abroad, often referred to as “Professional Schools”. These institutions, such as business, law, medical, and music schools focus on cultivating specialized talent. They emphasize field-specific knowledge, integrating academic study with practical application, and typically have competitive admissions and high educational value. Regarding Chinese industry-specific universities, research primarily explores their concept and connotation [14], historical development [15], opportunities and challenges [16,17], disciplinary development [18,19], evaluation systems [20], and development strategies [21,22,23]. Research on “Double First-Class” universities mainly concentrates on disciplinary development [24], with substantial findings on policy impact analysis [25,26], evaluation indicators [27,28,29], and resource allocation efficiency [30,31].

2.1. Industry-Specific University and Chinese Higher Education

2.1.1. Industry-Specific University in China

Industry-specific universities in China were established during the early years of the People’s Republic of China to address the urgent need for highly specialized personnel to support national development. These institutions possess distinct industry backgrounds, specialized disciplines, and targeted service orientations, primarily concentrated in sectors such as agriculture, forestry, geology, mining, petroleum, power, telecommunications, and transportation [32,33].

Industry-specific universities were typically affiliated with a specific industry or ministry before being transferred to the Ministry of Education or local authorities through reforms. Since their establishment, these universities have served as crucial bases for industry talent cultivation and scientific and technological innovation. Their long-term industry affiliation has fostered distinctive educational characteristics, leading to advanced development in specialized disciplines and distinct competitive advantages [34]. Within the national higher education system, industry-specific universities possess unique characteristics and play a vital role in supporting national strategies and leading industry development.

2.1.2. The Development of Industry-Specific Universities in Chinese Higher Education

The establishment and development of industry-specific universities are closely intertwined with the growth of various industries in China. Their evolution reflects, to a certain extent, the trajectory of national development strategies and higher education reforms at different stages in China’s history [35]. These universities emerged in the early years of the People’s Republic of China when the country was in urgent need of reconstruction and development. To meet the demands of national development, particularly in industry, there was an urgent need for a large number of highly skilled engineers and technicians. Emulating the Soviet model of education, China separated disciplines such as engineering, agriculture, medicine, normal education, political and legal studies, finance, and economics to establish specialized institutions, either newly built or through mergers. This led to the emergence of numerous single-discipline colleges and universities focused on specific industries and cultivating specialized talent. Through several rounds of departmental adjustments of varying scales and degrees, China gradually established a higher education structure and management system aligned with the planned economy [36].

With the deepening of reform and opening up, and the gradual establishment and improvement of the socialist market economy, societal development placed higher demands on the comprehensive qualities of talent. The planned economy’s administrative characteristics within industry-specific universities began to reveal drawbacks. The fragmented, sector-specific system led to issues such as closed educational systems, limited program offerings, and low economies of scale. Consequently, China initiated adjustments and transfers of these universities through co-construction and mergers, shifting their focus from serving specific departments and industries to serving broader societal needs across different regions and sectors. The reforms largely resolved the systemic issues arising from departmental management, while the integration of sectors expanded the depth and breadth of services provided by these universities, further optimizing the distribution and allocation of higher education resources. Through projects like the “211 Project” and “985 Project”, industry-specific universities continued to evolve and differentiate, with some cultivating distinct advantages in specific disciplines and gradually becoming high-level specialized institutions.

Reviewing recent developments in higher education, China has achieved rapid progress through initiatives like the “211” and “985” projects, effectively promoting the development of high-level universities and key disciplines. However, these achievements still fall short of the goals set by national development strategies and higher education reforms. The “Double First-Class” initiative, succeeding the “211” and “985” projects, aims to integrate Chinese universities into the global higher education system and significantly impact global university development [37]. For industry-specific universities, achieving “Double First-Class” status requires exploring a development path with Chinese characteristics. This necessitates top-level design, a focus on quality improvement, and a guiding principle of connotative development, shifting from an emphasis on quantity and scale to one on optimized structure and enhanced quality. This transformation is crucial for China’s historic leap from a large education provider to a strong education power.

2.2. World-Class Higher Education in China and Around the World

2.2.1. World-Class Higher Education Policy and Practice Around the World

The development of world-class universities has emerged as a significant focus in higher education policy globally, driven by the need for institutions to enhance their competitiveness and contribute to national development [38]. Key findings from various studies on the initiatives aimed at establishing world-class universities stressed the factors influencing their success and the implications for higher education systems. The global development of the “Double First-Class” initiative can be contextualized within broader trends in educational policy and governance.

Yang et. al. [39] emphasized the role of higher education in China’s national strategy, using Tsinghua University as a case study to illustrate how top-tier institutions are striving for excellence amid globalization. The initiative also reflects the strategic alignment between education initiatives and national policies. Salmi et. al. [40] conducted a comprehensive overview of the creation of world-class universities and identified the key elements for success. These elements are essential for universities to make informed decisions and allocate resources efficiently, thereby enhancing their global standing. Jacob et. al. [41] examined faculty development programs at several world-class universities across different countries. Their findings suggest that robust professional development frameworks are crucial for supporting teaching, research, and student learning, which are foundational to maintaining a university’s world-class status. Tilak [42] discussed the challenges and opportunities presented by global rankings and the push for world-class universities in India. The article stressed the need for a more strategic framework to foster excellence in its universities. Salmi [43] elaborated on the impact of excellence initiatives, noting that they not only affect the universities directly involved but also influence the broader tertiary education system. This interconnectedness suggests that the “Double First-Class” initiative may serve as a catalyst for systemic change within national education frameworks, promoting a culture of excellence that transcends individual institutions. Zhao et al. [44] analyzed China’s “Double First-Class” projects. They pointed out that although the initiative aims to diversify top universities, it has also strengthened their reliance on government resources. This kind of dependence may lead to isomorphic behavior, that is, institutions adopt similar structures and practices, potentially stifling innovation and unique institutional identity.

In summary, the global development of the “Double First-Class” initiative is situated within a complex landscape of excellence-driven educational policies, international collaboration, and the need for localized adaptation. The interplay of these factors underscores the initiative’s potential to reshape higher education while also highlighting the challenges posed by external influences on national educational systems. The development of world-class universities is influenced by a combination of strategic national policies, effective management practices, and robust faculty development programs. As higher education continues to evolve, the insights from these studies will be crucial for policymakers and educational leaders aiming to enhance their institutions’ global competitiveness.

In terms of practical exploration, against the backdrop of the continuous deepening of globalization, governments worldwide are striving to cultivate world-class higher education institutions. This effort aims to enhance international competitiveness in education and elevate national influence within the global academic community [45]. For instance, South Korea implemented the “Brain Korea 21 Project” (BK21) in 1999, aiming to develop world-class research universities and outstanding local universities [46]. Japan launched the “21st Century Centers of Excellence Program” in 2002 to establish globally competitive research centers and propel universities toward international prominence [47]. Germany’s “Excellence Initiative” in 2005 focused on fostering world-class research universities and teams, boosting German universities’ global competitiveness [48]. France initiated the “Initiatives d’Excellence” (IDEX) program in 2010 to create internationally competitive leading universities through mergers and restructuring [49]. Russia’s “5-100 Project”, started in 2012, aimed to strengthen world-class universities and integrate Russian higher education into the global market [50].

2.2.2. Double First Class” Initiative in China

The “Double First-Class” initiative is a systematic project for Chinese higher education to move towards world-class standards. China has introduced a series of policy documents to advance the project. This article mainly interprets the policy documents in three aspects: the overall plan, implementation measures, and opinions on promotion.

- (1)

- Overall Plan for Promoting the Construction of World-Class Universities and Disciplines

On 24 October 2015, the State Council issued the “Overall Plan for Promoting the Construction of World-Class Universities and Disciplines” [51]. The plan, a significant strategic decision by the Party Central Committee and the State Council, outlines new deployments for key higher education construction in the new era. While acknowledging the achievements of key construction projects such as the “211 Project”, “985 Project”, and “Innovation Platform for Advantageous Disciplines”, it also points out existing issues like solidified statuses, lack of competition, and duplication and overlap.

The plan proposes four fundamental principles: striving for first-class standards, focusing on disciplines, leveraging performance evaluations, and driving progress through reforms. It also outlines three support measures: comprehensive planning and tiered support; performance-based and dynamic support; and diversified investment and collaborative support.

The plan sets a “three-step” overall goal: By 2020, several universities and a number of disciplines should enter the ranks of world-class institutions, with some disciplines among the top in the world. By 2030, more universities and disciplines should achieve world-class status, with several universities ranking among the top globally and a group of disciplines leading the world, significantly enhancing the overall strength of higher education. By the middle of the 21st century, the quantity and quality of world-class universities and disciplines should be among the world’s best, and a strong higher education system will essentially be established.

- (2)

- Implementation Measures for Promoting the Construction of World-Class Universities and Disciplines (Interim)

On January 24, 2017, with the approval of the State Council, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Finance, and the National Development and Reform Commission jointly issued the “Implementation Measures for Promoting the Construction of World-Class Universities and Disciplines (Interim)” [52]. These measures clearly stipulate the selection criteria, procedures, and support methods for universities.

The measures emphasize the foundational role of disciplines, supporting the construction of approximately 100 disciplines to create peaks in specific disciplinary fields. A five-year cycle for construction was initiated in 2016. The construction of universities will be subject to overall quota control, open competition, and dynamic adjustments.

The measures propose to focus on major national strategic needs, the main battlefield of socio-economic development, and the frontiers of global scientific and technological development. The goal is to comprehensively enhance the overall strength of China’s higher education in talent cultivation, scientific research, social service, cultural inheritance and innovation, and international exchange and cooperation. Adhering to the principles of supporting excellence, addressing needs, promoting unique characteristics, and encouraging innovation, universities will be developed based on two categories: “world-class universities” and “first-class disciplines”. This approach aims to guide and support capable universities to position themselves appropriately, develop distinctive features, and pursue differentiated development, thereby forming a world-class university and discipline system that supports the country’s long-term development.

- (3)

- Several Opinions on Further Promoting the Construction of World-Class Universities and Disciplines

In February 2022, “Several Opinions on Further Promoting the Construction of World-Class Universities and Disciplines” [53] was issued by the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Finance, and the National Development and Reform Commission. The document affirmed the significant progress and reform achievements made since the implementation of the “Double First-Class” initiative, which has propelled China’s higher education to a new historical starting point in building a strong education nation. It also identified persistent challenges, such as an insufficient supply of high-level innovative talent, inadequate precision in serving national strategic needs, and the urgent need for optimized resource allocation. The document put forward 25 opinions for further advancing the construction of world-class universities and disciplines.

At the same time, the list of universities and disciplines for the second round of the “Double First-Class” initiative, as well as the list of first-round construction disciplines subject to public warning (including revocation), was announced [54]. The update and release of the lists mark the official start of the second round of the “Double First-Class” initiative, and also signify that the initiative has entered a new phase from “overall promotion” to “in-depth promotion”. Compared to the first round, the new list added eight disciplines from seven universities, all of which are provincially administered local high-level universities.

2.3. Sustainable Development in Higher Education

Various studies have explored the theory and practices regarding sustainable development in higher education, revealing both progress and challenges. Barth [55] emphasizes the transformative potential of sustainability education, advocating for a learning paradigm that adapts to the complexities of contemporary challenges. Filho et al. [56] evaluated the achievements of the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development and identified the key issues influencing future efforts in higher education. Their analysis emphasizes the need for continuous commitment and strategic planning to incorporate sustainability into the educational framework. Verhulst et al. [57] studied the organizational aspects of integrating sustainable development into higher education. Their insights into barriers and critical success factors provide a framework for understanding the complexities involved in institutional change. Ramos et al. [58] emphasized the multifaceted nature of implementing sustainable development, addressing stakeholder engagement, campus operations, and curriculum development as essential components of successful integration. Anand et al. [59] demonstrated the localization efforts of integrating sustainable development into higher education through a specific initiative. The necessity of cooperation among various stakeholders was emphasized. Filho et al. [60] pointed out the research gap regarding the role of planning in promoting the sustainability of higher education. They believe that effective planning is crucial for evaluating institutional performance and achieving integration at the economic, social, and environmental levels of sustainable development.

In summary, these studies reveal a complex landscape of beliefs, practices, and challenges surrounding sustainable development in higher education. While there is a clear commitment to integrating sustainability into educational frameworks, significant barriers remain. Future research and practice must focus on overcoming these obstacles and fostering a more cohesive approach to sustainability in higher education.

Several studies have investigated factors contributing to sustainable development in Chinese higher education. These include research on the post-doctoral system [61] and institutional internationalization [62]. Furthermore, scholars have analyzed how world-class university initiatives affect higher education sustainability by examining student training systems [63], graduate education outcomes [64], and policy implementation effectiveness [65]. However, studies applying ecological theory and practice to the sustainable development of world-class universities in China remain scarce.

3. Methods

3.1. SWOT Analysis

3.1.1. Strategic Analysis Method

Common strategic analysis methods include SWOT, PESTEL, Porter’s Five Forces model, and the Boston Matrix. These methods are very classic strategic analysis tools in management science, with universality and operability. They can be used to analyze the external macro environment, industry competitive environment, and internal resources and capabilities of higher education institutions.

Each method has its unique perspective and applicable scenarios. For example, SWOT is a tool for comprehensively analyzing internal and external factors and is suitable for a comprehensive assessment of a university’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats [66]. PESTEL focuses more on the analysis of political, economic, social, and technological factors in the external macro environment, with less analysis of internal resources. It may not fully cover the internal characteristics of industry-specific universities and cannot directly support the formulation of specific strategic decisions for universities [67]. Porter’s Five Forces model focuses on the dynamics of industry competition and is more inclined towards industry competition analysis. For non-profit, public-interest organizations like universities, its applicability is somewhat limited. Although it can help universities understand the competitive situation within the industry, its analysis of internal university resources may not be in-depth enough, which can lead to one-sided strategic decisions [68]. The Boston Matrix simply categorizes a university’s majors or disciplines into four types: stars, cash cows, question marks, and dogs, which cannot accurately reflect the complex relationships and differences between various majors or disciplines within a university. It only considers two factors, market growth rate and relative market share, without taking into account other internal strengths of the university and external opportunities, and thus cannot comprehensively analyze the sustainable development issues of a university [69].

In summary, SWOT analysis may be a more rational choice, with strong operability and specificity. The sustainable development of industry-specific universities involves both internal resources (such as disciplines, faculty, and research capabilities) and external environments (such as industry policies and market demands). The SWOT method can comprehensively consider internal and external factors, analyzing the university’s internal strengths and weaknesses as well as external opportunities and threats, to provide a holistic review of the university’s sustainable development status. Moreover, it can help universities identify their core competencies (strengths) and areas for improvement (weaknesses), and formulate strategies in combination with external opportunities and threats, which is more conducive to developing comprehensive strategic decisions [70].

3.1.2. SWOT Analysis and Its Steps

SWOT analysis, originating in the 1960s, was initially used for business strategic planning. Since then, it has found widespread application not only in business but also in various fields such as public policy, education, and healthcare. SWOT analysis is a method that systematically identifies and analyzes the key internal strengths (S) and weaknesses (W), as well as external opportunities (O) and threats (T) closely related to the object of study. By matching and analyzing these factors in a structured manner, the method draws conclusions to inform strategic decision-making. Based on the Resource-Based View and Environmental Scanning theories, it posits that an organization’s success depends on its ability to identify and utilize internal resources while simultaneously responding to changes in the external environment [66,70]. This paper utilizes SWOT analysis to examine the environmental conditions qualitatively for the sustainable development of industry-specific universities within the context of the “Double First-Class” initiative.

The steps of SWOT analysis [71,72] are as follows:

- Information Gathering: Collect information about the organization’s internal and external environment through literature reviews, policy interpretation, and other methods.

- SWOT Factor Identification: Categorize the collected information into strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

- Analysis and Evaluation: Conduct an in-depth analysis of each SWOT factor, assessing its impact on the organization’s strategy.

- Strategy Formulation: Develop corresponding strategies and action plans based on the results of the SWOT analysis.

3.2. Ecological Niche Analysis

3.2.1. Niche Theory and Its Application

Niche is a core concept in ecology, describing a species’ position, role, and relationship with other species within an ecosystem. It reflects an organism’s utilization and adaptation of resources and environmental variables. Originating from natural ecosystems, niche theory primarily investigates the influence of the environment on the survival and evolution of biological populations within a specific time and space.

In 1910, American scholar R.H. Johnson first introduced the concept of “ecological niche” in ecological discourse, noting that different niches in an environment could be occupied by different species in the same area [73]. In 1917, Grinnell, while studying the spatial reorganization and division of biological habitats, adopted the concept of “niche” and defined it as the ultimate ecological distribution unit precisely occupied by a species or subspecies, where the species survives and develops [74]. Grinnell’s research popularized the concept of niche, later known as spatial niche. In 1927, Charles Elton, from the perspective of community ecology, stated that “An animal’s niche represents its position in the biotic environment and its relationship with food and natural enemies”. He emphasized species’ roles in community nutritional relationships. This concept was later referred to as the trophic niche [75]. In 1957, Hutchinson utilized mathematical set theory to view niche as a total aggregate of living conditions for a biological unit. He provided a mathematical abstraction of the niche concept considering multiple aspects including space and resource utilization, proposing the n-dimensional hypervolume model of niche. This model is known as the hypervolume niche [76].

The concept of niche has found extensive application not only within ecology but also in social sciences, including politics, economics, agriculture, industry, and education. It has become an analytical tool for studying large-scale human social systems. Its introduction into the humanities and social sciences began in 1977 when Harman and Freeman used the concept of niche to measure the multi-dimensional resource space occupied by businesses within the commercial environment [77]. Since then, niche theory has gradually emerged in the field of management research, used to study relationships between entities within ecosystems, network structures, entity diversity, and entity evolution.

With the deepening of research on higher education, the similarities between universities and biological organisms have attracted increasing attention from scholars. Subsequently, educational research based on niche theory has been conducted. Regarding the application of niche theory in higher education, the renowned British educator Ashby noted, “A university is an organism, and like organisms in natural ecology, it is a product of both heredity and environment” [78]. This was the first time in higher education research that a university was compared to a biological organism, laying the foundation for subsequent research on university niches. This established a precedent for applying ecological principles and methodologies to higher education studies.

As a form of social ecosystem organization, universities exhibit biological-like characteristics similar to natural species, and their development follows the niche theory. Analogous to natural ecosystems, universities interact with other universities, industry enterprises, government departments, and the surrounding geographical, political, and economic environments to form a complex ecosystem [79]. Within this system, universities obtain the resources necessary for survival and development through the exchange of materials, energy, and information. Similar to the hierarchical structure of individuals, populations, and communities in ecology, the university ecosystem can be analyzed at three levels: micro, meso, and macro. At the micro level, individual university development is observed; at the meso level, the development of similar types of universities (i.e., populations) is examined; and at the macro level, the coexistence of different types of universities (i.e., communities) is studied. Therefore, niche theory can be employed to analyze the niches and relationships of universities and to guide their sustainable development through strategic adjustments.

The concept of ecological niche is abstract and ambiguous, requiring specific quantitative indicators for measurement. There are many parameters that can characterize niche features, such as niche situation, niche breadth, niche overlap, and niche differentiation. But the two most commonly used indicators are niche breadth and niche overlap [80]. This paper adopts niche breadth and niche overlap as the measurement indicators.

3.2.2. Niche Breadth and Its Measurement Models

Niche breadth quantifies the total extent of system resources utilized and occupied by a population, indicating both the degree of resource utilization diversity and competitive intensity. There are many types of niche breadth measurement models, such as Levins’ model, Schoener model, and Hurlbert model. During the application process, models that are simple and have clear biological significance are widely and long-term used, while those with complicated forms and ambiguous biological significance are gradually eliminated. Currently, research on niche breadth measurement based on a single resource axis still constitutes the majority in China [80]. In this study, niche breadth is calculated using the Shannon–Wiener index formula, adapted from Levins’ model [81]. The Shannon–Wiener index is a common metric in ecology used to measure community diversity. The formula is simple to calculate and has a clear biological significance. It considers both species richness (the number of species) and evenness (the distribution of individuals among species). The formula for the Shannon–Wiener index is as follows:

where

is the Shannon–Wiener index;

is the total number of species in the community;

is the proportion of the i-th species in the community relative to the total number of individuals.

The ecological niche theory posits that greater niche breadth correlates with enhanced ecological functions within the system, superior resource utilization and occupation capabilities, heightened competitive advantage, and increased likelihood of niche overlap.

In the context of this study,

represents the university niche breadth;

represents the number of university resource units;

represents the percentage importance value of the j-th resource unit for the i-th university.

Under conditions of primary resource scarcity, higher education institutions demonstrate a tendency toward resource diversification and generalization, resulting in niche breadth expansion. In contrast, resource abundance may facilitate specialization in resource acquisition, leading to niche narrowing.

3.2.3. Niche Overlap and Its Measurement Models

Niche overlap quantifies the extent of resource sharing or competitive interactions among interrelated populations occupying the same spatial dimension, providing a foundational theoretical and methodological basis for examining mechanisms of species coexistence and competition in natural communities. There are a wide variety of niche overlap measurement models, such as the Curve average model, Likelihood estimation model, and Probability ratio model. However, in practical applications, models that are simple in form and have clear biological significance are more widely accepted. In China, research on niche overlap measurement based on a single resource axis still constitutes the majority [80]. In this study, niche overlap is calculated using the symmetric alpha index, also known as Pianka’s index [81]. Its formula is as follows:

where

is the niche overlap index between species and species ;

is the proportion of utilization of resource state by species ;

is the proportion of utilization of resource state by species ;

is the total number of resource states.

Niche overlap value range: . A larger value indicates a higher degree of niche overlap between the two species.

In the context of this study,

represents the niche overlap value of university i with university j;

represents the proportion of resource k utilized by university i;

represents the proportion of resource k utilized by university j;

is the total number of university resource states;

=1 indicates complete niche overlap between the universities; = 0 indicates complete niche separation between the universities.

3.3. Research Design

3.3.1. Research Object

There are many important industrial sectors in the national economic system. Transportation is a foundational, pioneering, and strategic industry in the national economy. It is an important support for building a modern economic system. Transportation provides the necessary connections and links for economic activities such as production, distribution, and consumption, and is known as the “pioneer of economic development” [82]. Therefore, this paper plans to select industry-specific universities related to transportation as the research objects.

In addition to the important industry status and role of transportation mentioned above, there are some other reasons for selecting it as the research object. Specifically, on the one hand, the first round of the “Double First-Class” university list released in 2017 shows that in fields such as mining, petroleum, geology, power, and transportation, there are relatively more industry-specific universities in the transportation field, with a total of 3. Other industries basically have only 1 or 2. Choosing industry-specific universities in the transportation field is conducive to comparative analysis of the situations among universities. The research on them is expected to find new results. On the other hand, the second round of the “Double First-Class” university list released in 2022 saw an increase of three comprehensive universities in the construction of first-class disciplines in Transportation Engineering. This is conducive to conducting comparative analyses between industry-specific universities in the transportation field and comprehensive universities that share the same first-class discipline.

The list of second-round “Double First-Class” universities and disciplines released in 2022 represents the latest status of the “Double First-Class” construction in China. In this study, we focus on the second-round “Double First-Class” initiative, especially the discipline of Transportation Engineering. According to the list, there are only six universities related to the discipline of Transportation Engineering. These universities, which are selected for this study, are industry-representative and have distinct advantages in Transportation Engineering.

Among them, U1, U2, U3 are the multi-disciplinary comprehensive universities in the second round of the “Double First-Class” construction universities list, with first-class disciplines including Transportation Engineering. T4, T5, T6 are the single-disciplinary industry-specific universities in both the first and second rounds of the “Double First-Class” construction universities list, with Transportation Engineering as the only first-class discipline.

The analysis of this paper is based on the publication time of the first and second round of “Double First-Class” universities and disciplines lists, with 2017 and 2022 being two important time nodes. The development level of each university at the time nodes and the development trend of universities in the time series are calculated and analyzed, respectively.

3.3.2. Research Hypothesis

From the perspective of resource occupation and utilization, this paper regards the universities in the “Double First-Class” construction list as an ecosystem, with universities having the same “Double First-Class” construction disciplines forming an ecological group, and each university being a species. For the Transportation Engineering ecological group, in 2017, it included 3 species, namely Group 1: T4, T5, T6. In 2022, 3 new species entered, namely Group 2: U1, U2, U3. In total, there were 6 species, namely Group 3: U1, U2, U3 and T4, T5, T6. As for universities outside the “Double First-Class” construction list that have the Transportation Engineering discipline, they do not belong to the “Double First-Class” construction ecosystem, so this study ignores their possible impacts.

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

From 2017 to 2021, the Transportation Engineering ecological group had 3 species (Group 1: T4, T5, T6). The 3 new species (Group 2: U1, U2, U3) that entered in 2022 had no impact on the original ecological group during their potential period before entry.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

From 2017 to 2021, the Transportation Engineering ecological group had 3 species (Group 1: T4, T5, T6). The 3 new species (Group 2: U1, U2, U3) that entered in 2022 had an impact on the original ecological group during their potential period before entry.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

From 2022 to 2024, the Transportation Engineering ecological group had 6 species (Group 3: U1, U2, U3, T4, T5, T6). The 3 new species (Group 2: T4, T5, T6) that entered in 2022 had no impact on the original ecological group (Group 1: U1, U2, U3) during the coexistence period after entry.

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

From 2022 to 2024, the Transportation Engineering ecological group had 6 species (Group 3: U1, U2, U3, T4, T5, T6). The 3 new species (Group 2: T4, T5, T6) that entered in 2022 had an impact on the original ecological group (Group 1: U1, U2, U3) during the coexistence period after entry.

3.4. Data

The functions of universities cover multiple areas, including talent cultivation, scientific research, social services, cultural heritage and innovation, international cooperation and exchange, as well as regional development. According to Xue et al. [83], based on the niche theory, the competition of industry-specific universities under the context of the “Double First-Class” initiative was analyzed. The study selected three types of resources—enrollment numbers, full-time faculty, and student population—to investigate four textile-specific universities. Building on the previous research, this paper expands the measurement indicators to four dimensions by adding research funding, considering the universities’ ability to acquire and manage resources. Ultimately, four dimensions—research funding, enrollment numbers, full-time faculty, and student population—are selected to calculate the niche breadth and niche overlap.

- Niche Breadth: Calculated using the Shannon–Wiener index formula, which measures the diversity and evenness of resource utilization by universities.

- Niche Overlap: Calculated using Pianka’s formula, which assesses the degree of resource sharing or competition between universities.

The data used in this study is sourced from publicly available online resources, including the websites of the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Science and Technology, the National Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences, and various university websites. Particular emphasis was placed on official university admissions and employment reports and undergraduate quality assessment reports. These sources provided comprehensive information on the selected aspects of the chosen universities. The data collection period spans from 2017 to 2024. The units for enrollment numbers, full-time faculty, and student population are in persons, while the unit for research funding is in billions of yuan.

4. Results

4.1. SWOT Analysis of Industry-Specific Universities

The use of the SWOT method for qualitative analysis of industry-specific universities is necessary and useful. It can provide a comprehensive understanding of the internal and external environment and offer strong support for their strategic planning and decision-making.

4.1.1. Strengths

- (1)

- Disciplinary Construction Highly Aligned with Industry NeedsIndustry-specific universities have a highly aligned disciplinary structure with specific industries. Since their inception, these universities have focused on professional layout around the main thread of industrial development and industry service areas. Over time, they have continued to concentrate on a few distinctive and advantageous disciplines closely related to their respective industries [18]. This mode of disciplinary construction, which is tightly connected to industry needs, offers significant advantages in disciplinary systems. It enables universities to quickly respond to industry changes, providing strong technical and intellectual support for industry development and driving technological progress and industrial upgrading.

- (2)

- Talent Cultivation Closely Integrated with Industry NeedsThe talent cultivation in industry-specific universities emphasizes integration and coordination with industry development. By setting up professional courses that precisely match industry job requirements, students’ theoretical knowledge is closely aligned with real-world working scenarios. Moreover, these universities have close working relationships and rich cooperation experience with industry authorities and enterprises. Through practical training, students’ hands-on abilities are enhanced. The faculty, with extensive experience in the industry, can provide the latest industry knowledge and practical experience. Under the customized training system, a large number of technical backbone and leading talents in the industry have been cultivated, creating a positive chemical reaction of integration among industry, academia, and research.

4.1.2. Weaknesses

- (1)

- Relatively Narrow Disciplinary CoverageUnder the long-term development model led by distinctive disciplines, industry-specific universities have gradually formed their unique educational characteristics and built a number of high-level distinctive disciplines. However, this has also led to structural imbalances in the disciplinary system. While the distinctive disciplines are highly advantageous and strong, the development of basic and supporting disciplines lags behind [19]. This limits the sustainability and expandability of the disciplinary system. The structure of the disciplinary system makes it difficult for universities to demonstrate collaborative innovation capabilities when facing interdisciplinary and comprehensive issues. This is not conducive to the cultivation of interdisciplinary and emerging disciplines and fails to meet the new requirements for connotative development.

- (2)

- Relatively Limited Resource AcquisitionInsufficient industry support has led to the decline of internal “productive capacity”. With reduced policy and funding support from industry departments and weakened channels and mechanisms for communication, the internal “productive capacity” of industry-specific universities has significantly declined. The weakening of industry connections has also reduced external “delivery capacity”. Industry practice is the starting point and destination for university professional settings, curriculum systems, and training models. The reduced guidance and support from former industry authorities in talent cultivation and scientific innovation have led to decreased output in terms of talent and technology. The depth and breadth of service to the industry have visibly contracted, and the universities’ social reputation and industry influence have been compromised.

4.1.3. Opportunities

- (1)

- New Requirements from National StrategyIndustry-specific universities are entering an important period of development opportunities. To achieve socialist modernization and the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, China has set a series of strategic goals that provide significant opportunities for university development. The implementation measures for the “Double-First-Class” initiative clearly state that the construction of world-class universities and disciplines should meet major national strategic needs. Industry-specific universities should meet these national strategic needs, such as the “Strategy for National Strength” and the “the Belt and Road Initiative”. National strategies inject new momentum into universities in talent cultivation, social service, scientific innovation, and cultural exchange, opening up new paths for international development. They encourage universities to improve their educational standards and service capabilities and contribute to national modernization.

- (2)

- New Opportunities Brought by Industry DevelopmentCompared with comprehensive universities, industry-specific universities should not only meet major national practical needs in the “Double-First-Class” construction but also satisfy industry demands. The 19th National Congress Report proposed 12 “Strategy for National Strength” goals, including a strong country in science and technology and manufacturing [84] goals, which are the embodiment of a modern socialist power in various fields. The disciplinary construction and talent cultivation of industry-specific universities in related fields are crucial for achieving these goals. China is in a period of strategic opportunity for an innovation-driven development strategy. Traditional industries are upgrading, and emerging industries are rising. There is an urgent need for technological cooperation and industrial integration, which requires universities to provide technological innovation and intellectual support. This brings significant opportunities for industry-specific universities.

4.1.4. Threats

- (1)

- Competition from Other UniversitiesUnder the constraints of policies and funding from industry authorities and the orientation of the higher education development evaluation system, industry-specific universities face a development trend of “de-industrialization” and “tending towards comprehensiveness”. On the one hand, the weakening of industry connections and support has led to a trend of “increasing disciplines and diluting characteristics”, making them gradually similar to comprehensive universities and losing their distinctive advantages. On the other hand, current university rankings are based on the size of total volume and scale for comprehensive ranking. Universities reform and adjust around this “bigger and more comprehensive” guiding principle, which encourages them to blindly pursue quantity and scale and follow a “tending towards comprehensiveness” path [20]. The homogenized development of industry-specific universities makes it difficult to form competitive advantages over other universities.

- (2)

- Pressure from Development PoliciesThe continuous advancement of the “Double First-Class” initiative has solved problems such as rigid identities and lack of competition in the “985 Project” and “211 Project”. The overall plan and implementation measures for the “Double First-Class” initiative propose “three orientations” and “three types of support”, emphasizing the dilution of identities and encouraging fair competition. This provides industry-specific universities with unprecedented development policies and a fair and just development environment. China’s higher education has entered a new period of connotative development. The evaluation mechanism of “up and down, dynamic adjustment” has replaced the “lifetime” identity mark of universities, creating development pressure for the original “985” and “211” universities and also bringing pressure to some rapidly developing industry-specific universities.

Based on the analysis of the internal strengths and weaknesses, as well as the external opportunities and threats faced by industry-specific universities under the “Double First-Class” initiative, four strategic paths can be identified (Table 1): the SO (Strengths–Opportunities) development strategy that leverages strengths to seize opportunities, the WO (Weaknesses–Opportunities) turnaround strategy that capitalizes on opportunities to address weaknesses, the ST (Strengths–Threats) diversification strategy that uses strengths to avoid threats, and the WT (Weaknesses–Threats) defensive strategy that overcomes weaknesses to confront threats.

Table 1.

Industry-specific universities SWOT matrix.

These strategies provide a comprehensive framework for industry-specific universities to navigate the complex landscape of the “Double First-Class” initiative, ensuring sustainable development and enhanced competitiveness in the context of national and industry needs.

4.2. Ecological Niche Analysis of Industry-Specific Universities

4.2.1. Niche Breadth Analysis

Niche breadth primarily reflects the extent to which a subject utilizes its surrounding environment. Generally, a larger niche breadth indicates a wider range of fields involved and a higher degree of environmental utilization, which is often associated with stronger competitiveness. However, a wider niche is not always better. If it exceeds a certain threshold, it may lead to niche overlap with other entities, which is not conducive to enhancing competitiveness.

This paper, in accordance with the research hypotheses, employed the niche breadth measurement model to separately calculate the niche breadth of universities within the ecological group of Transportation Engineering from 2017 to 2024. To analyze the niche breadth of universities, we focused on two key time points: 2017 and 2022, based on the publication dates of the first and second rounds of the “Double First-Class” initiative. According to the research hypothesis, the paper calculates the niche breadth under two extreme conditions, that is, assuming that Group 2 (U1, U2, U3) has an impact on the original ecosystem species both before and after entering the ecosystem, Group 3 (U1, U2, U3, T4, T5, T6) is the ecological group under complete impact, and Group 1 (T4, T5, T6) is the ecological group under no impact at all. Moreover, it is assumed that there are no other influences from 2017 to 2024. The results are shown in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Niche breadth of Group 3 (2017–2024).

Table 3.

Niche breadth of Group 1 (2017–2024).

- (1)

- Niche Breadth (2017)

Group 3:

As shown in Table 2, university U3 had the largest niche breadth in 2017. This can be attributed to several factors:

- Resource Endowment: U3 had a relatively high level of research funding and the highest enrollment numbers, full-time faculty, and student population compared to the other five universities. This comprehensive resource base contributed to its broader niche.

- Uniformity of Resource Distribution: The analysis of niche breadth not only considers the level of values across dimensions but also the uniformity of these values. Compared to the other universities, U3 had the most evenly distributed values across the four dimensions of research funding, enrollment numbers, full-time faculty, and student population.

- Disciplinary Completeness and Service Scope: U3 had a more complete range of disciplines and a broader scope of social services, which naturally led to a larger niche breadth.

In contrast, T4 had the lowest niche breadth due to significantly lower levels of the four resources compared to other universities. University T6 had lower research funding, U2 had lower full-time faculty numbers, and U1 had lower student populations, respectively, which also narrowed their niche breadths.

Group 1:

As shown in Table 3, the niche breadth values of the universities T4, T5, T6 of Group 1 in 2017 are all larger than those in Group 3. The same situation applied from 2018 to 2021. In 2022, the three new species (U1, U2, U3) that entered had an impact on the original ecological group during their potential period before entry. Meanwhile, the niche breadth relationships in Group 1 are T4 < T5 < T6, and in Group 3 are T4 < T6 < T5, which shows that the influencing effects are not the same. This indicates that Hypothesis 1 does not hold in 2017, while Hypothesis 2 is valid.

- (2)

- Niche Breadth (2022)

Group 3:

As shown in Table 2, the analysis reveals that university U3 still had the largest niche breadth in 2022. The reasons are as follows: U3 maintained a mid-to-high level of research funding and had the highest enrollment numbers, full-time faculty, and student population compared to the other five universities. Meanwhile, U3 also had the most evenly distributed values across the four dimensions.

In contrast, T4 continued to have the lowest niche breadth due to significantly lower levels of the four resources compared to other universities. T6’s research funding and full-time faculty numbers, T5’s research funding and full-time faculty numbers, and U2’s student population were also significantly lower than those of other universities, which narrowed their niche breadths. U1 had a larger niche breadth due to its higher research funding and full-time faculty numbers, and a more even distribution across dimensions.

Group 1:

As shown in Table 3, the niche breadth values of the universities T4, T5, T6 of Group 1 in 2022 are still larger than those in Group 3. The same situation applied from 2023 to 2024. The three new species (U1, U2, U3) that entered in 2022 had an impact on the original ecological group during their coexistence period after entry. Meanwhile, the niche breadth relationships in Group 1 are T4 < T5 < T6, and in Group 3 are T4 < T6 < T5, which shows that the influencing effects are not the same. This indicates that Hypothesis 3 does not hold in 2022, while Hypothesis 4 is valid.

- (3)

- Niche Breadth Trends (2017–2024)

To analyze the niche breadth of universities within the Transportation Engineering ecological group, we focused on two key time points: 2017 (the first round of the “Double First-Class” initiative) and 2022 (the second round of the “Double First-Class” initiative). This study also examined the period from 2017 to 2024 to identify overall and phased development trends in niche breadth for these universities.

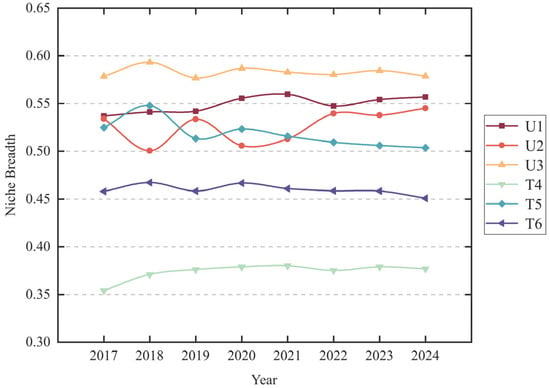

Group 3:

- Overall Trends

As shown in Figure 2, the niche breadth of Group 3 is generally stable and orderly between 2017 and 2024. From 2017 to 2021, there were relatively large fluctuations. After the implementation of the “Double First Class” construction, it had a certain impact on the development of existing universities. From 2022 to 2024, the situation became relatively stable, and the pattern of “Double First Class” universities began to take shape.

Figure 2.

Trends in niche breadth of Group 3 (2017–2024).

- Specific Observations

University U3: Maintained a broad niche breadth throughout the period, with a relatively even distribution of resources across research funding, enrollment, faculty, and student population.

University T4: Continued to have the narrowest niche breadth due to its significantly lower resource levels in all four dimensions.

University U1 vs. T5: Between 2018 and 2019, U1’s niche breadth gradually surpassed that of T5. This was due to a significant decline in enrollment and student population at T5 during this period, leading to a more uneven distribution of resources.

University U2 vs. T5: Between 2021 and 2022, U2’s niche breadth increased significantly due to substantial increases in research funding and student population, allowing it to surpass T5.

These findings highlight the dynamic changes in resource allocation and utilization among the selected universities, reflecting their strategic responses to the “Double First-Class” initiative.

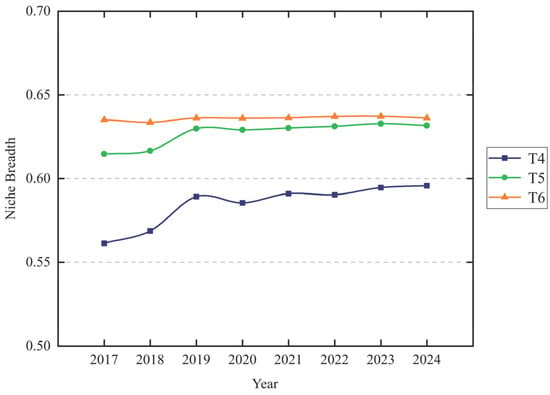

Group 1:

As shown in Figure 3, the niche breadth of Group 1 increased steadily from 2017 to 2024. Similar to Group 3, it also experienced fluctuations from 2017 to 2021 and remained relatively stable from 2022 to 2024. However, the difference is that in Group 3, the niche breadth of T4, T5, and T6 showed a significant upward trend overall, especially from 2017 to 2021, while in Group 1, the niche breadth of T4, T5, and T6 showed a downward trend. This indicates that the entry of Group 2 brought competition to the original ecological group, making the competition for resources more intense.

Figure 3.

Trends in niche breadth of Group 1 (2017–2024).

- (4)

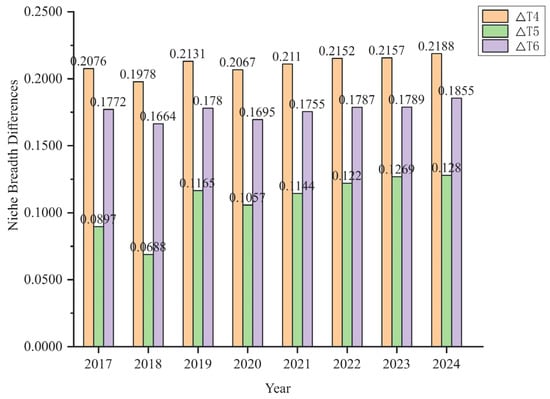

- Niche Breadth Change (2017–2024)

To analyze the niche breadth changes, this paper defines the niche breadth differences in T4, T5, and T6 between Group 1 and Group 3 under the paper’s assumptions as △T4, △T5, and △T6, respectively. The calculation results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The niche breadth differences in T4, T5, and T6 between Group 1 and Group 3 (2017–2024).

It can be seen that the change in niche breadth (Δ) is the greatest for T4, the smallest for T5, and T6 falls in between. The factors influencing the changes in niche breadth are closely related to the disciplines and directions of the “Double First-Class” construction. Within the same discipline and direction, the competition for the same resources tends to be more intense. The differences in niche breadth are also the reasons for the changes in the niche size relationships of T4, T5, and T6 between Group 1 and Group 3.

Overall, the variation rate of the ecological niche breadth is closely related to the history of university mergers and development, disciplinary positioning, geographical location, and the status of regional economy and industry development. Mergers can bring about the expansion of resources and disciplines for universities. However, if the integration is not effectively carried out or the positioning is not accurately determined after the merger, it may lead to a decrease in the ecological niche breadth. Geographical location and regional economy provide the development environment for universities. A clear and advantageous disciplinary positioning can enhance the competitiveness and attractiveness of universities, thereby promoting the growth of the ecological niche breadth.

Illustratively, U1, U2, U3 have merged multiple institutions to form comprehensive universities, creating multiple disciplines for the “Double First-Class” construction and establishing extensive and in-depth channels for resource acquisition. In comparison, U1’s Transportation Engineering program has a longer history, and its disciplinary advantages are more pronounced than those of U3. U2, located in the national center for politics, economy, culture, and science and technology, enjoys a superior geographical location and abundant resources. It has developed multiple disciplines for the “Double First-Class” construction. T4, T5, and T6 are situated in regions with relatively underdeveloped economies, resulting in a more limited range of disciplines for the “Double First-Class” construction and weaker resource competition capabilities compared to other universities.

Group 1 is the control group, Group 2 is the variable group, and Group 3 is the observation group. In terms of the numerical value of niche breadth, its development trend, and the changes observed, it confirmed that Hypothesis 1 does not hold, while Hypothesis 2 is valid. Hypothesis 3 was not supported, but Hypothesis 4 was. This means that at the beginning of the “Double First-Class” initiative, some universities that were not included in the list for the “Double First-Class” program in Transportation Engineering had already begun to occupy and utilize the same resources. Moreover, as the number of universities in the “Double First-Class” list for Transportation Engineering increased, it had a certain competitive inhibitory effect on the resource occupation and utilization of the original universities. Overall, in the ecological group of Transportation Engineering, the entry of new species from Group 2 has led to a competitive effect on resources for the original species in the ecological group, whether in the latent period or the symbiotic period.

4.2.2. Niche Overlap Analysis

Niche overlap primarily reflects the common utilization of resources by different entities, characterized by the shared use of a portion of resources while others are used separately. According to niche overlap theory, the more extensive the overlap between two entities’ niches, the more intense their competition. Conversely, the more distinct their niches, the higher the likelihood of coexistence.

This paper, in accordance with the research hypothesis, employed the niche overlap measurement model to calculate the niche overlap of universities in the Transportation Engineering ecology group from 2017 to 2024. To analyze the niche overlap, we focused on two key time points, 2017 and 2022, based on the release dates of the first and second rounds of the “Double First-Class” initiative. According to the research hypothesis, the paper calculates the niche overlap under two extreme conditions, that is, assuming that Group 2 (U1, U2, U3) has an impact on the original ecosystem species both before and after entering the ecosystem, Group 3 (U1, U2, U3, T4, T5, T6) is the ecological group under complete impact, and Group 1 (T4, T5, T6) is the ecological group under no impact at all. Moreover, it is assumed that there are no other influences from 2017 to 2024. The results are shown in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 4.

Niche overlap of Group 3 in 2017.

Table 5.

Niche overlap of Group 3 in 2022.

Table 6.

Niche overlap of Group 1 in 2017.

Table 7.

Niche overlap of Group 1 in 2022.

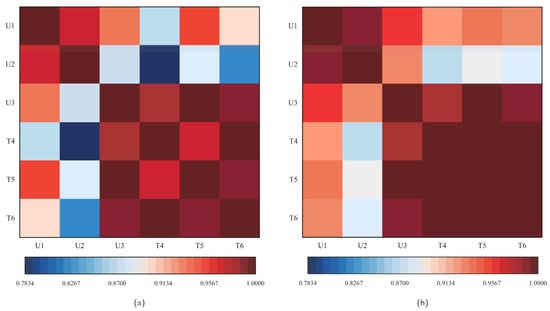

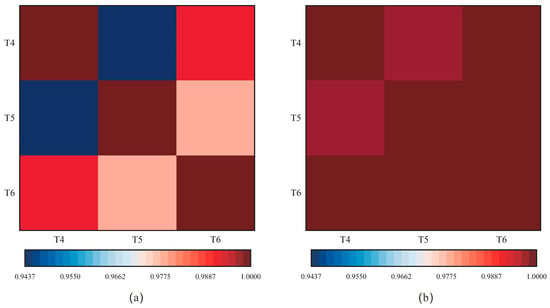

To visually represent the data, heatmaps can be used to intuitively display the similarity or correlation between different universities. The color scale, ranging from blue to gray, yellow, orange, and red, defines different levels of overlap, with darker colors indicating higher similarity. The heatmaps for the years 2017 and 2022 are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively.

Figure 5.

Heatmap of niche overlap of Group 3 in 2017 (a); heatmap of niche overlap of Group 3 in 2022 (b).

Figure 6.

Heatmap of niche overlap of Group 1 in 2017 (a); heatmap of niche overlap of Group 1 in 2022 (b).

- (1)

- Niche Overlap (2017)

Group 3:

As shown in Table 4 and Figure 5, the niche overlap among the universities (Group 3) was generally high, indicating strong competition for the four resources. In 2017, T4, T5, and T6 had relatively high niche overlap. This was because all three universities were classified as “Project 211” institutions, which are at the same tier and thus faced intense competition. In 2017, all three were designated as first-class discipline construction universities, with Transportation Engineering as their sole first-class discipline. As industry-specific universities in the transportation sector, they shared many common majors and disciplines, resulting in high niche overlap. U1, U2, and U3, which were also included in the first batch of “Double First-Class” universities (Category A), had relatively lower niche overlap. At that time, none of the three universities included Transportation Engineering in their first-class discipline construction, and their “Double First-Class” disciplines were diverse in types and directions.

In Group 3, the niche overlap values between U1, U2, U3 and T4, T5, T6 are lower than the niche overlap values among T4, T5, and T6 themselves. It was explained that in the early stage of the “Double First-Class” initiative, comprehensive universities had a certain impact on industry-specific universities, but the competition among industry-specific universities remained the main issue in this stage.

Group 1:

As shown in Table 6 and Figure 5, in 2017, the niche overlap values among T4, T5, and T6 in Group 3 were higher than those in Group 1. This indicates that the three universities in Group 2 (U1, U2, U3) had already exerted an influence on the universities in Group 1 during the potential period before the discipline of Transportation Engineering was identified as a “Double First-Class” construction discipline. Specifically, this situation intensified their competitive nature for resources.

- (2)

- Niche Overlap (2022)

Group 3:

As shown in Table 5 and Figure 6, the niche overlap among the universities (Group 3) remained high and even showed an increasing trend compared to 2017. In the second batch of the “Double First-Class” university list announced in 2022, T4, T5, and T6 still only had Transportation Engineering as a first-class discipline. Meanwhile, after the fourth-round discipline assessment (2016–2020), the Transportation Engineering disciplines of T4 and T6 had the same ranking. These factors led to high overlap and fierce competition among these three industry-specific universities. In the second round of “Double First-Class” construction, U1, U2 and U3 added Transportation Engineering as a first-class discipline. However, their niche overlap remained relatively low because their fourth-round disciplinary ratings were different, and their Transportation Engineering programs focused on different directions, such as aviation transport, rail transport, and urban rail transit.

In Group 3, the niche overlap values between U1, U2, U3 and T4, T5, T6 are still lower than those among T4, T5, and T6 themselves. However, compared with 2017, the gap is narrowing. This indicates that in the process of the “Double First-Class” initiative, the influence of comprehensive universities on industry-specific universities is increasing. This influence is closely related to the similarity of disciplines and their directions in universities.

Group 1:

As shown in Table 7 and Figure 6, overall, the niche overlap of universities (T4, T5, T6) in 2022 remains very high and shows an upward trend compared to 2017. In 2022, the niche overlap between T4, T5, and T6 was greater in Group 3 than in Group 1. This indicates that after Group 2 (U1, U2, U3) universities identified Transportation Engineering as a first-class construction discipline, their coexistence period with Group 1 universities has already had an impact on the universities in Group 1. Specifically, this situation has also intensified their competition for resources.

4.2.3. Case Study

T6 is a university directly administered by the Ministry of Education of China. It is one of the first batch of universities to be key construction institutions under the national “211 Project”, a university with a “985 Advantages Discipline Innovation Platform”, and a university under the national “Double First-Class” construction initiative. The discipline of Transportation Engineering at T6 University was selected as a construction discipline under the “Double First-Class” initiative in 2017 and was again selected in the second round of the “Double First-Class” construction in 2022. After the first round of construction, the comprehensive strength of the discipline has stably ranked among the top in China. This study takes T6 as a case and conducts a case study based on the niche perspective, involving both self-analysis and comparative analysis.

The niche breadth of T6 and its changes are shown in the above table and figure. From 2017 to 2024, the niche breadth of T6 showed a fluctuating downward trend, although the magnitude was small. T6 occupied a certain niche, but there was a gap compared with other universities, and its resource competitiveness was relatively weak. In terms of resources, the number of students was at a medium-high level, while the other three indicators were relatively low. In the process of the “Double First-Class” initiative, the niche breadth was maintained at a certain level, but the resource occupation and competitiveness were limited, and the future development sustainability was insufficient.

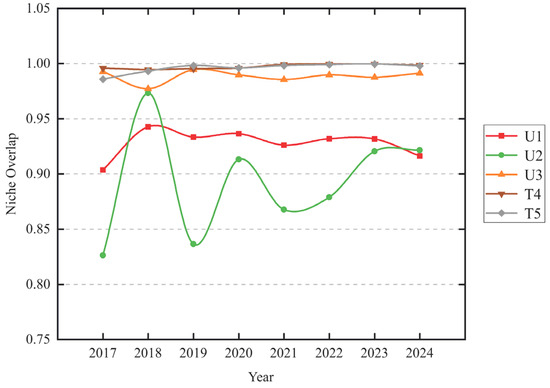

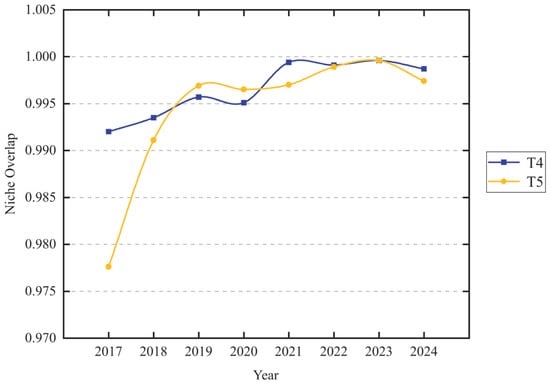

The niche overlap relationships of University T6 with other universities in different groups from 2017 to 2024 are shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8. Overall, the niche overlap of T6 is generally at a high level in different groups. Specifically, in Group 1, T6 had extremely high and increasing niche overlap with T4 and T5, both of which are also industry-specific universities in the transportation sector. In contrast, the comprehensive nature of U1 and U2, with a larger number and variety of first-class disciplines, resulted in relatively lower niche overlap with T6. U3 added Transportation Engineering as a first-class discipline in the second round of the “Double First-Class” construction. However, its number of discipline clusters is relatively small, and its niche overlap with T6 has been increasing year by year.

Figure 7.

Trends in niche overlap of T6 and other universities of Group 3 (2017–2024).

Figure 8.

Trends in niche overlap of T6 and other universities of Group 1 (2017–2024).

After the fourth-round discipline assessment in 2020, industry-specific universities clarified their basic positioning and development direction. However, the sustainable development structure of universities has not yet been fully established. The competition for resources largely depends on the planning and matching by the government through administrative means, lacking market-based adjustments based on the characteristics, strengths, and resource advantages of universities. In the process of the “Double First-Class” initiative, industry-specific universities have gradually moved towards comprehensive development in the competition with comprehensive universities, but they do not have an advantage in the competition.

Established during a period of national rejuvenation and industrial development in China, T6 was subsequently restructured through mergers. It is now jointly built by the Ministry of Education, multiple industry management departments, and the local government. It has evolved into a distinctive industry-specific university, focusing on transportation, land resources, and urban–rural development.