We received IRB approval for this experiment and the included materials.

The primary manipulation in this study was whether participants saw an educational video about multi-material plastics or a control video. Public awareness of multi-material plastics is low, at least partially because new research providing new knowledge and best practices in the field can move quickly and the majority of the public is not exposed to these advances [

32]. Because of the lack of understanding of multi-material plastics, an educational video could be effective in filling the knowledge gap. Related research suggests that videos are often an effective way to communicate information, especially compared to alternatives like text or infographics [

33]. So, we created an educational video after exploring the existing educational media on multi-material plastic. In January 2024, we searched for an educational video and could not find any that (1) were not affiliated with a company or cause (e.g., “ban plastic bags”), thereby potentially creating a conflict of interest; (2) differentiated between the types and recycling processes of different plastics; and (3) provided a nuanced (highlighting both costs and benefits) understanding of plastic. Because technology is still advancing in multi-material plastics, we were not surprised not to find a video satisfying 1–3. Hence, we created a new educational video.

We adopted a two-pronged strategy to create the educational video combining top-down and bottom-up approaches. Starting with the bottom-up approach, we first asked ChatGPT (San Francisco, CA, USA) (version 3.5) to provide a 5-min script covering what the average person should know about multi-material plastic recycling. We believed this approach may allow for adequate sampling of the available information and may buffer against a noted pitfall in the educational plastic literature (e.g., information provided by ChatGPT was not necessarily affiliated with a company or cause, or in our case, a grant). We then consulted with experts in chemical engineering to check the script for accuracy (a top-down approach). The experts provided input on the script, which did not significantly alter the content of the script from ChatGPT (see the OSF page for the initial ChatGPT script and the final expert-revised script).

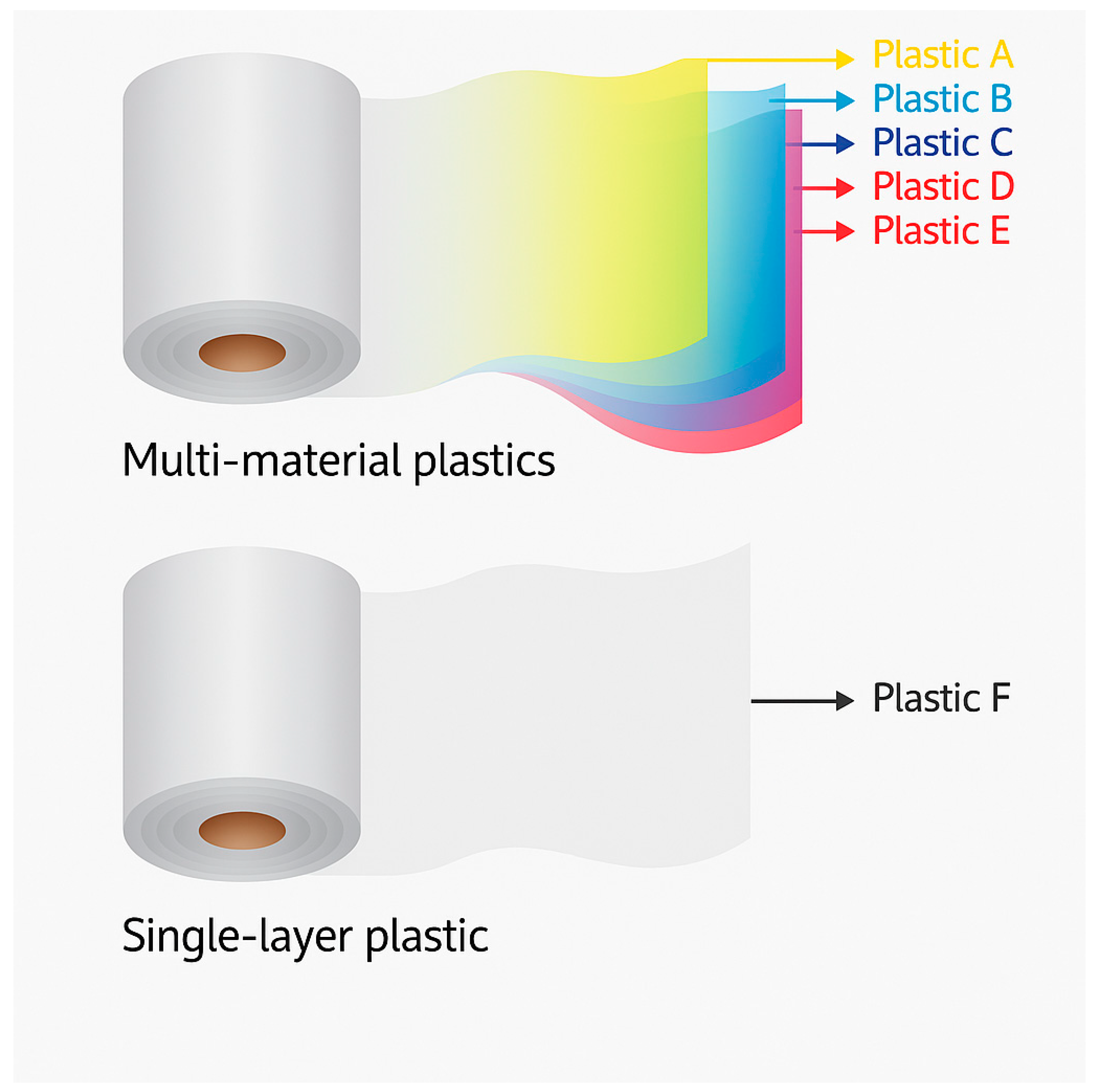

The video started with some basic facts about plastic, detailing how much we rely on plastic, how plastic is classified, and how little plastic is recycled. The video then explained some of the factors impacting the recyclability of plastic, namely (1) the type (i.e., some plastics are easier to recycle because they are composed of one layer made of one material), (2) the ease of separation and purification (i.e., rigid, solid plastic containers are easy to separate and recycle, whereas plastic films can easily become tangled with other products and machinery, making them more difficult to recycle), and (3) the current state of technology (i.e., we currently only have technology to recycle efficiently certain types of plastic, such as PET and HDPE, but not other types of plastic, such as multi-material films). The video then discusses mechanical recycling, which is the process through which most plastic is currently recycled, and how mechanical recycling is unable to recycle multi-material films. Because we wanted to provide a nuanced understanding (i.e., both costs and benefits), we then highlighted some of the beneficial properties of multi-material films (e.g., extends the shelf life of fresh products, greater durability in changing temperature conditions, less quantity needed). Chemical recycling, one (but not the only) proposed method to recycle multi-material films, was then highlighted, briefly explaining the process as one in which chemical reactions convert plastics into their original compounds or into a different type of compound to facilitate recycling. We focused on only one potential novel technology rather than several (i.e., enzymatic or biological recycling) for two main reasons. First, the length of the video needed to be short to ensure that participants watched the video. Second, we knew of no empirical reason to think that the specific kind of novel technology would make a difference in the outcome variables we measured. We assumed one novel technology would be functionally identical to all novel technologies in the video (although future research could test this). The video concludes by informing viewers that researchers are currently working on energy and cost-efficient ways to carry out chemical recycling and separation processes on a larger scale. The length of the educational video was 5 min and 8 s, and can be viewed here:

https://youtu.be/x1zclNe1OD4 (accessed on 1 July 2024).

Procedure

After providing informed consent, participants were randomly assigned to either the education condition, where they watched the video on plastic recycling, or the no-education condition, where they watched a video on the lifecycle of sea turtles (

https://youtu.be/xAbAwgWyinQ (San Bruno, CA, USA), accessed on 1 July 2024). The no-education video was selected because it was approximately equal in length to the plastic education video (5:13) and did not contain any content about plastic or plastic recycling. To ensure participants paid attention to the video, they responded to a multiple-choice attention-check item: “The video was about _____.” For the control video, the response options were sea turtles, starfish, sharks, or jellyfish. For the education video, the response options were plastic recycling, paper recycling, glass recycling, or aluminum recycling. Anyone answering incorrectly was excluded from analyses.

After viewing one of the two videos, we randomly assigned participants to receive one of three hypothetical scenarios involving a plastic recycling company. We included different versions of the scenario to test

framing nudges. We included this additional manipulation to explore the comparative effects of the educational video to more traditional choice architecture interventions commonly used in the environmental domain [

16]. The framing manipulation systematically changed the description of how much plastic was recycled, while remaining arguably logically equivalent [

13,

20,

34]. While framing nudges are typically presented dichotomously in the literature (e.g., positive/gain vs. negative/loss), we included an additional “neutral” frame to act as a control.

The scenario we used for the positive (underlined), negative (italics), and neutral (normal) font framing nudge conditions, respectively (in brackets), was:

“Recycling Company A estimates that they [recycle 20–30%/do not recycle 70–80%/recycle some] of the plastic they receive. Previously Recycling Company A did not accept certain types of plastic waste, but one day they announce that they will invest in new technologies to recycle plastic waste that they previously did not accept.”

Individuals were instructed to read the passage carefully, as they would be asked a series of questions regarding Recycling Company A.

After reading one of the scenarios, participants responded to a set of questions about (1) their knowledge of multi-material plastic (see

Table 1); (2) their satisfaction with the company (see

Table 2); (3) their intention to use the company (see

Table 3); (4) their trust in the company [

35] (see

Table 4); and (5) how just they viewed the company [

36,

37,

38] (see

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8 for distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational justice, respectively).

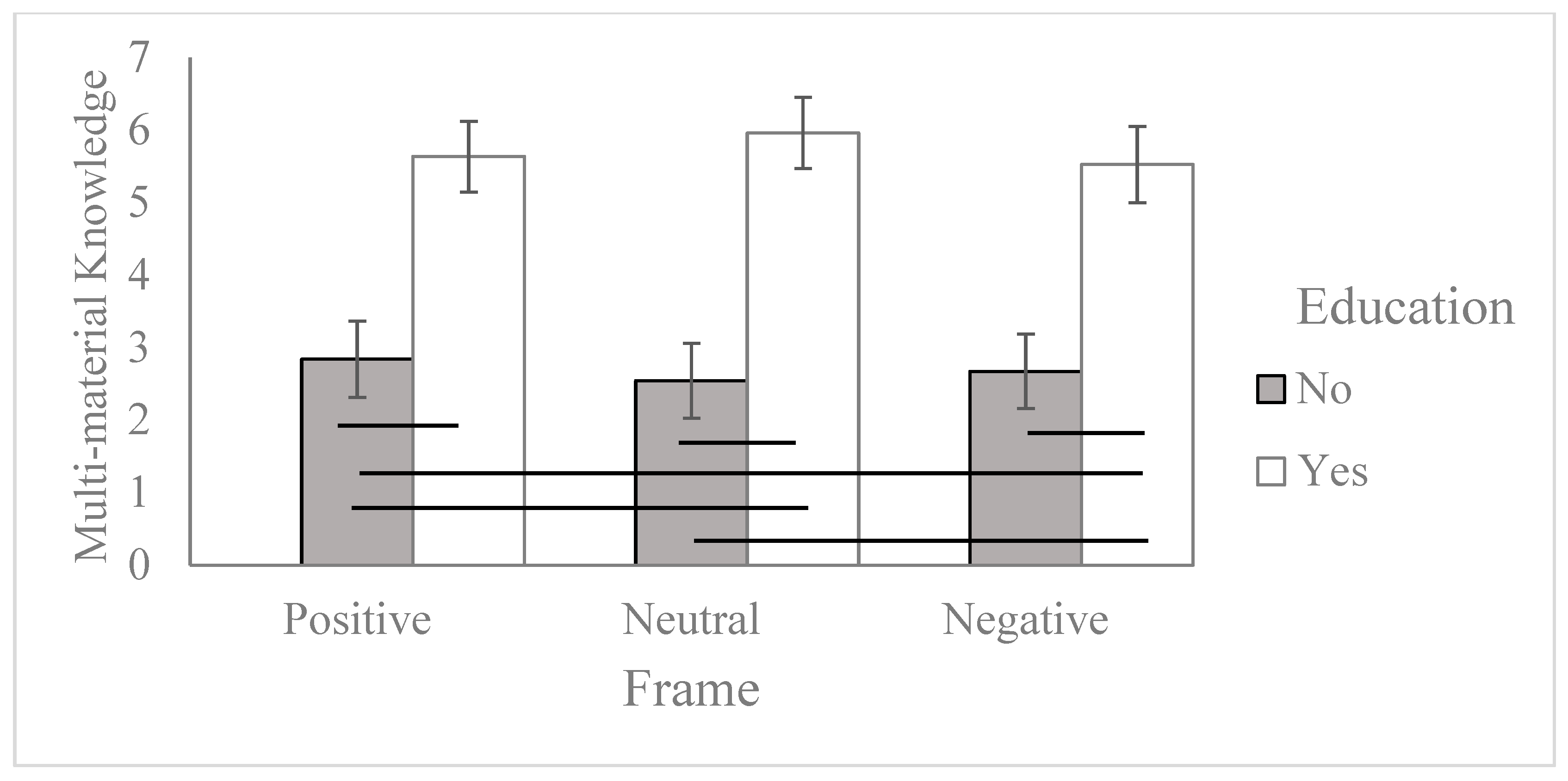

Participants were asked nine T/F items about multi-material plastics that had been previously verified as correct by experts in the field (see

Table 1). Participants could indicate whether they believed the item was true, false, or they could select “I don’t know”. We added the number of correct responses for each participant (from 0 to 9) and used the sum for further analysis. We hypothesized that those who viewed the educational video would be more knowledgeable about multi-material plastic and that knowledge would translate to other important outcomes [

12]. We anticipated that the effect of the educational video on multi-material knowledge would persist in all framing conditions (i.e., participants would be more knowledgeable if they watched the video than if they had not in all framing conditions). We did not anticipate that those who did not watch the educational video would be any more knowledgeable about multi-material plastics regardless of the frame they received.

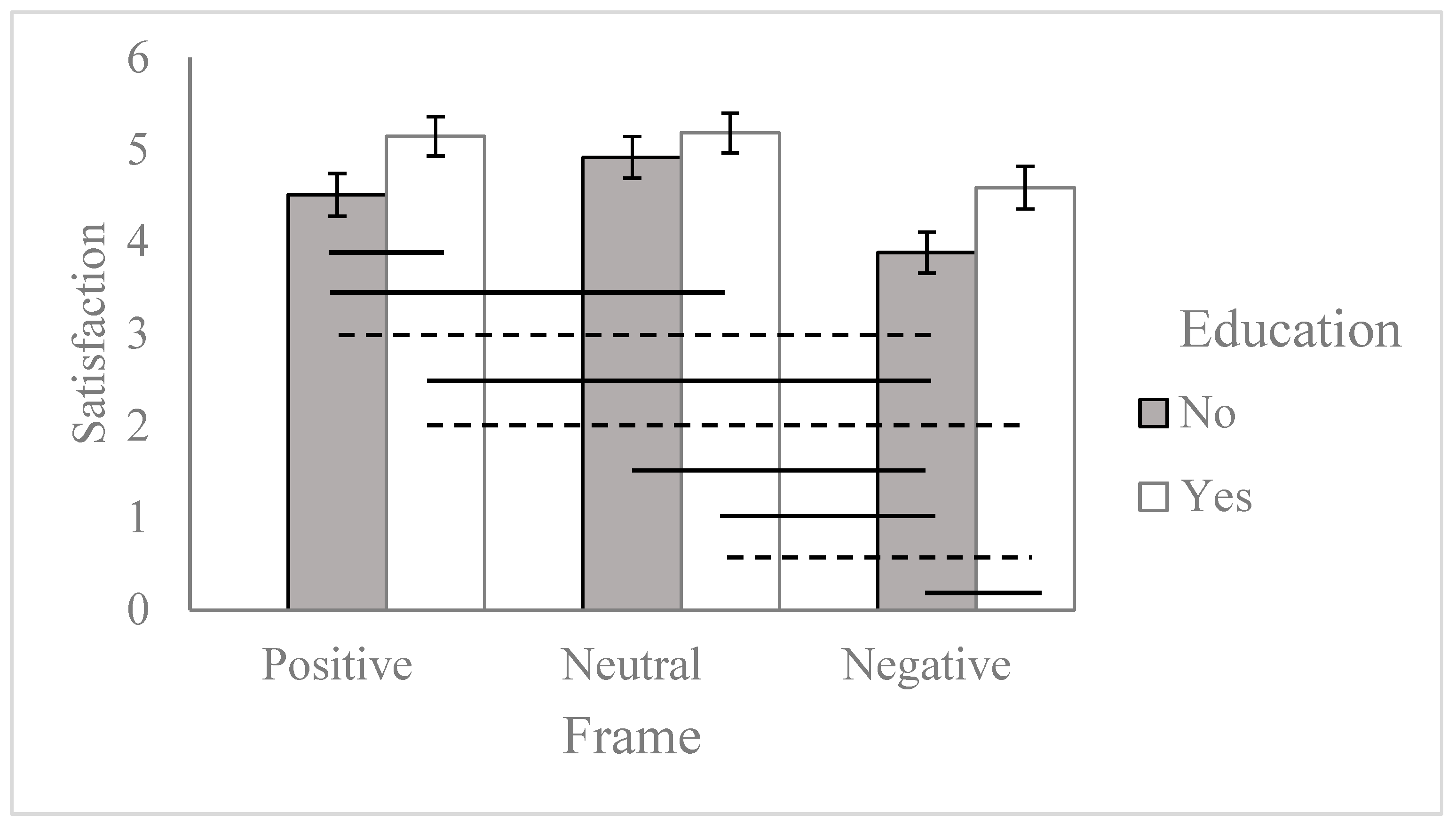

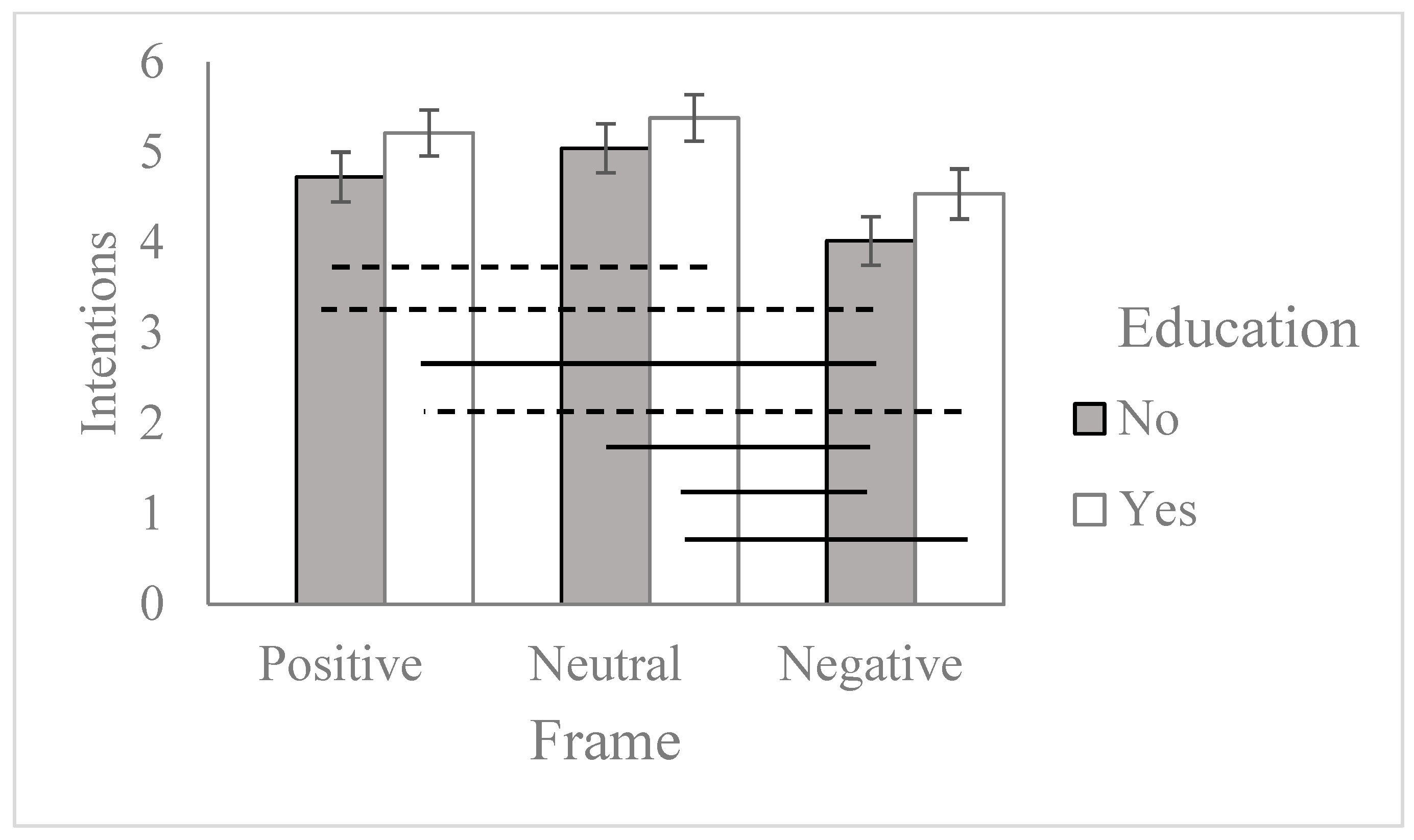

The rest of the measures participants responded to pertained to Recycling Company A, the hypothetical recycling company introduced in the framing nudge. Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with statements assessing each measure on a 7-point Likert scale. We constructed items assessing participants’ satisfaction with and intentions to use Recycling Company A (see

Table 2 and

Table 3 for items and descriptives; see

Table 4 and

Table 5 for exploratory factor analyses).

Satisfaction with and intentions to use Recycling Company A were our main targeted outcome variables (i.e., outcomes often targeted with nudges). While satisfaction and intentions are not actual behaviors, they are often positively related to behaviors (e.g., the more satisfied one is with a provider and the more they intend to take part in a behavior, the more likely one is to participate in the behavior with that provider). While behavioral intentions are not the sole predictor of behaviors, they are often related to actual behavioral change [

39]. We hypothesized that those who watched the educational video would be more satisfied with and have higher intentions to use Recycling Company A. While we anticipated some effect of the framing nudge, we did not have explicit directional hypotheses (e.g., positive frame more effective than negative frame or vice versa) due to the mixed results in the literature on framing nudges both across and within domains.

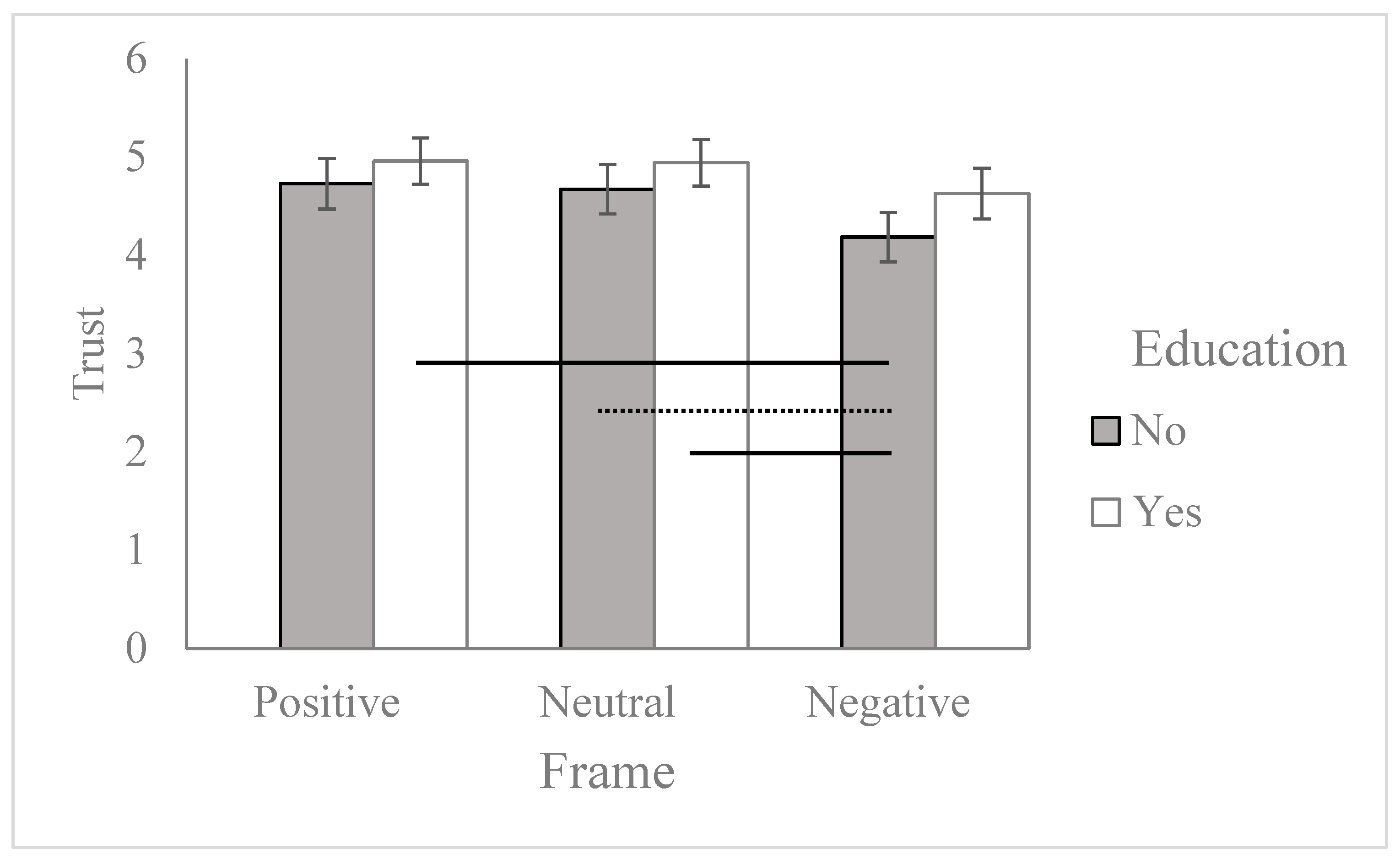

The trust measure was adapted from a validated existing measure [

35,

40]. Trust is not a typical target of nudges since it is not a specific behavioral outcome, but it is nonetheless often taken to be an important element of effective interventions. Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with nine items assessing their level of trust in Recycling Company A (see

Table 6). We hypothesized that individuals who watched the educational video would be more trusting of Recycling Company A due to their increased understanding of why this company had previously rejected certain types of plastic. We did not have any explicit hypotheses for how trust would vary as a function of the framing nudge.

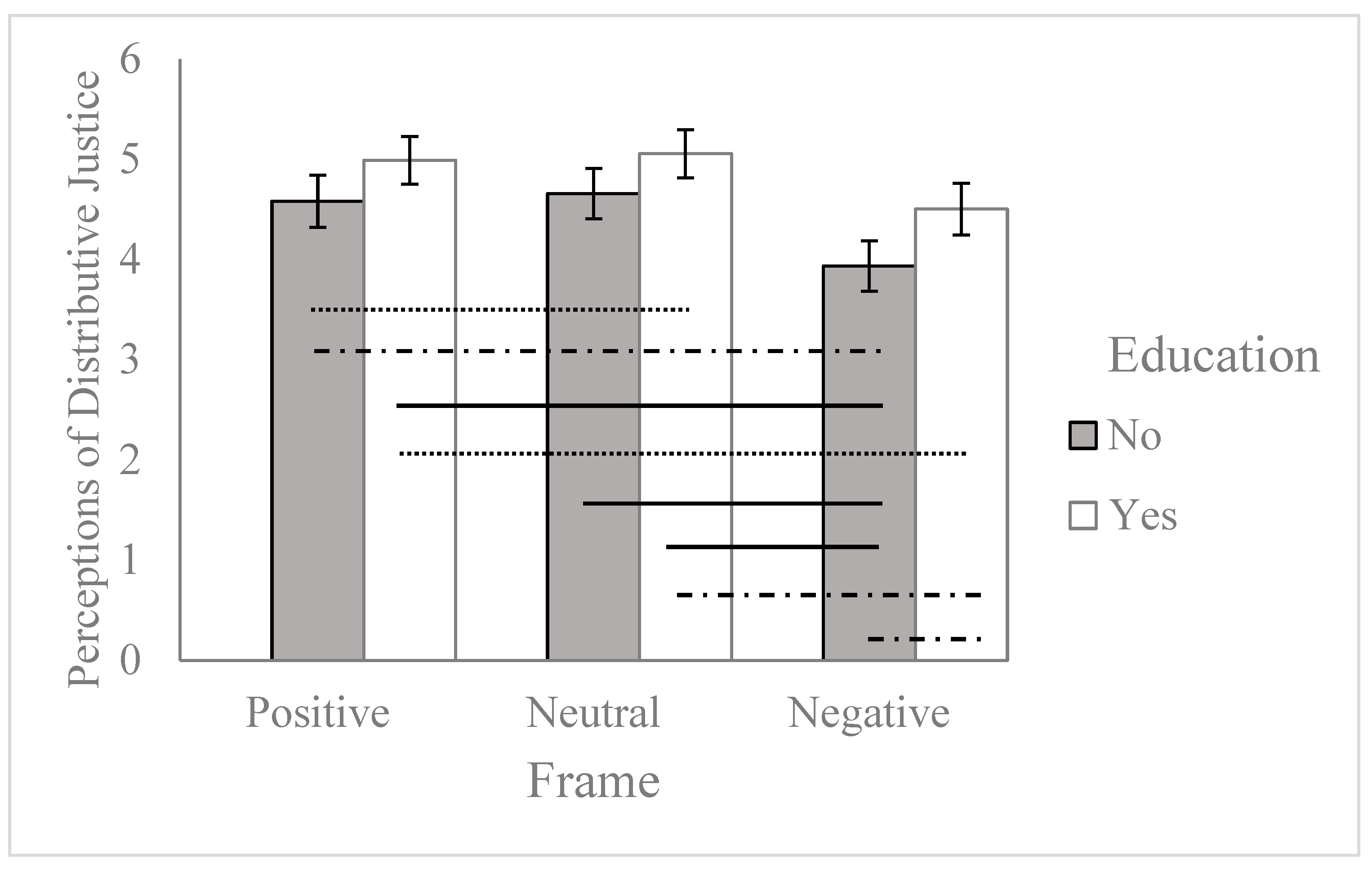

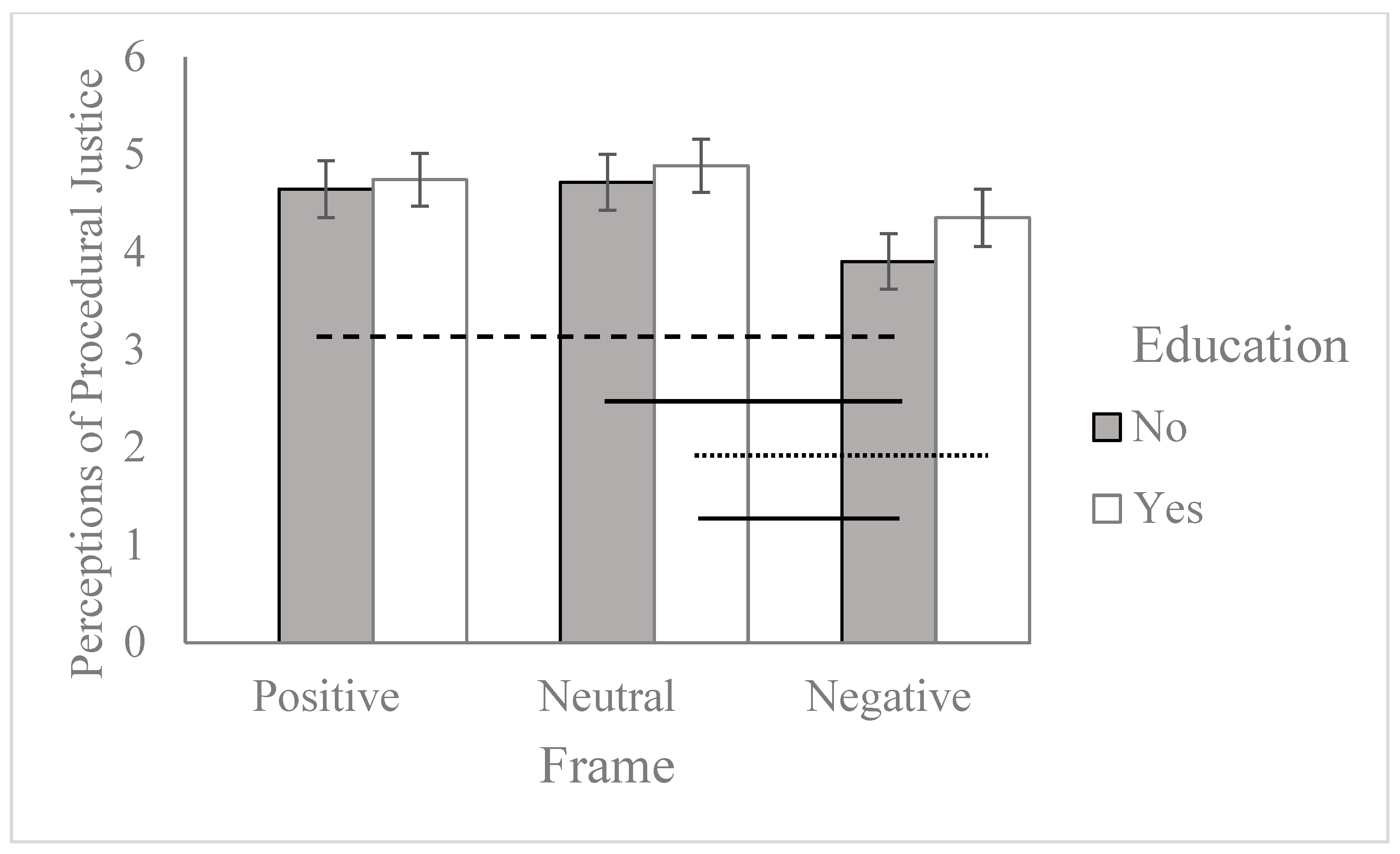

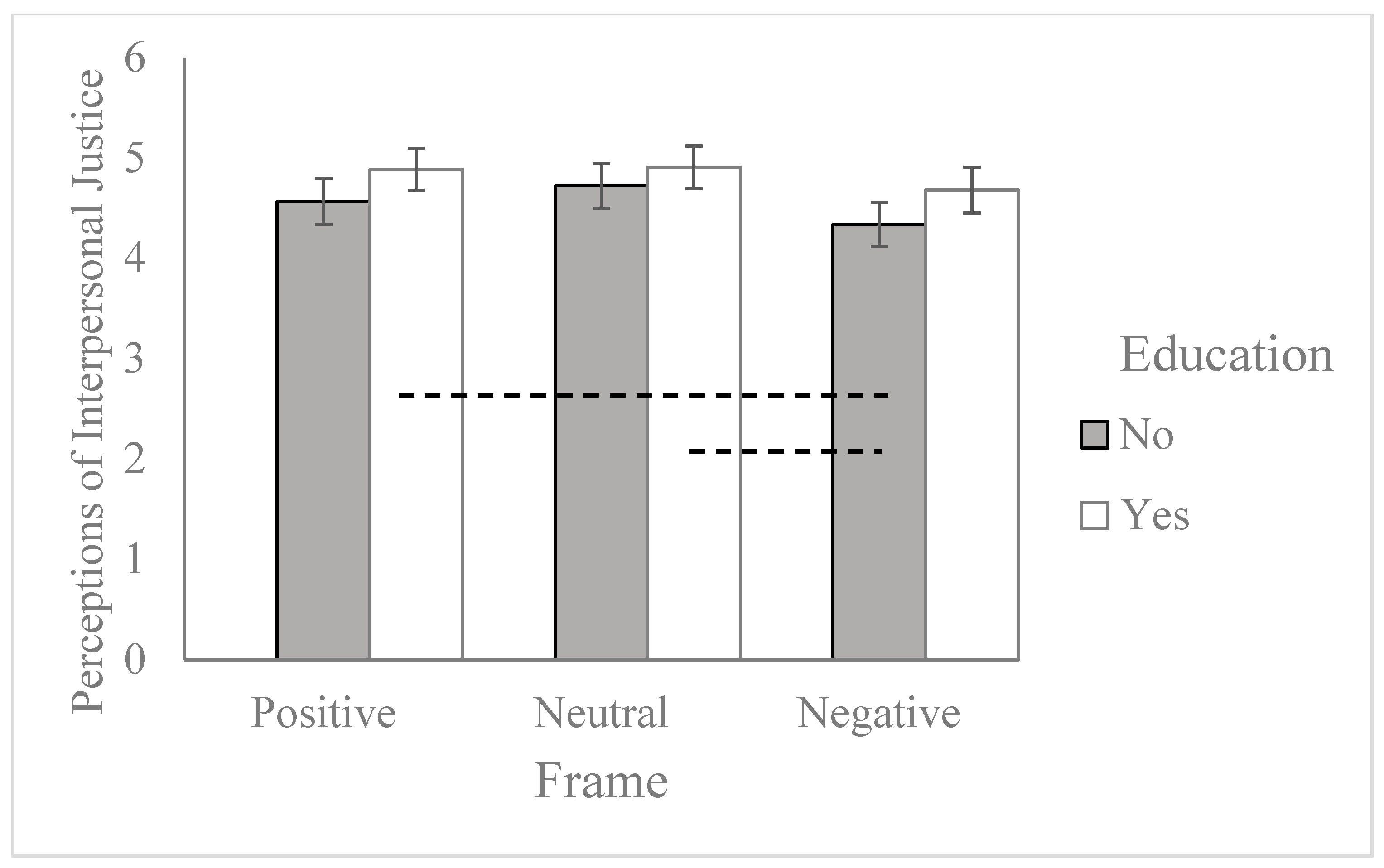

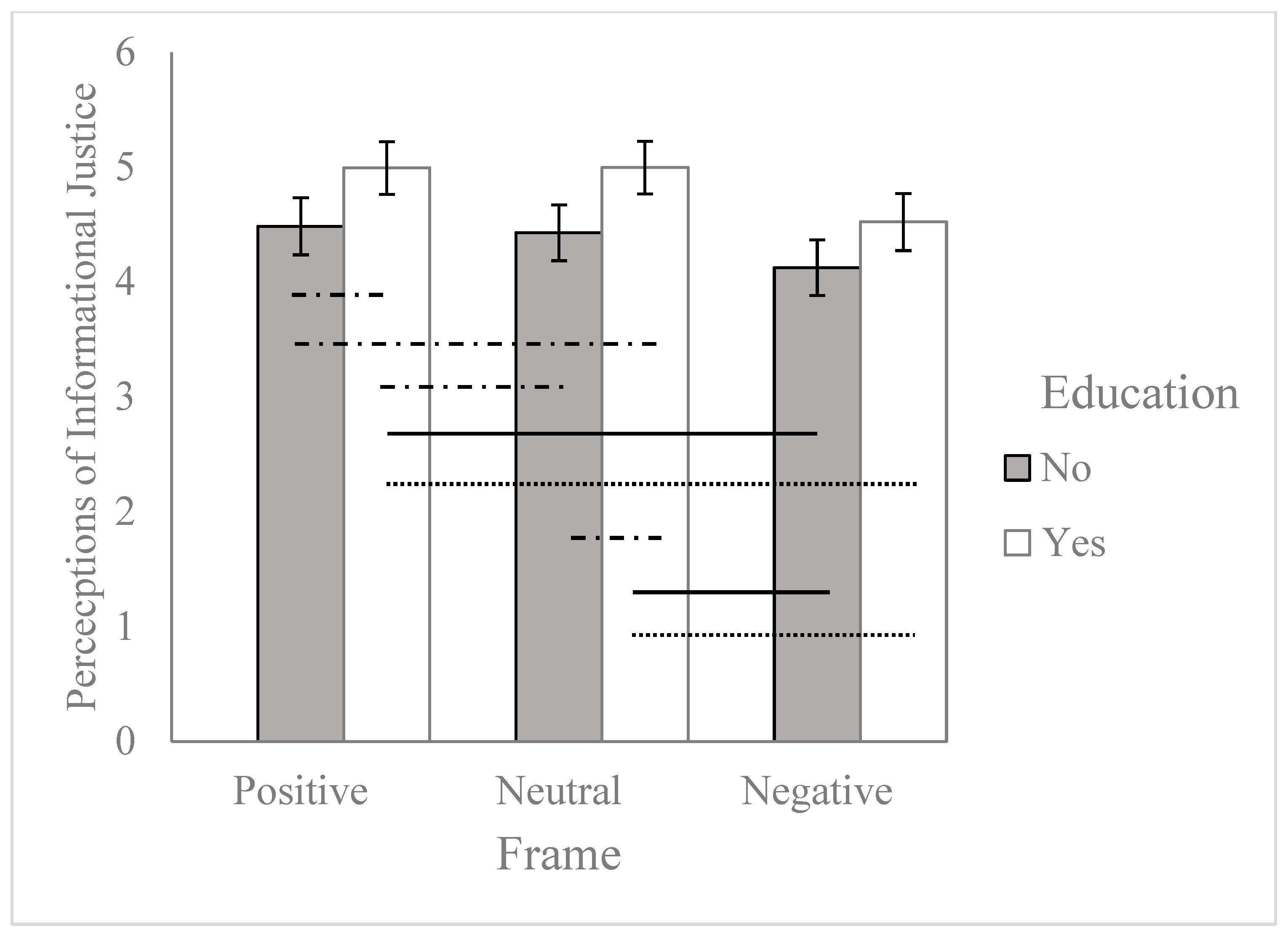

Participants then responded to sixteen items assessing their perceptions of distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational justice of Recycling Company A (see

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10). We measured perceptions of justice using a scale that was adapted and validated from the existing literature (see [

36,

37,

38,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]). We had explicit hypotheses only regarding informational justice, anticipating that individuals who had viewed the educational video would perceive recycling information as more open, accessible, and tailored to their needs. While we did not have explicit hypotheses pertaining to distributive, procedural, and interpersonal perceptions of justice, we still included these measures, as justice is commonly measured as a multi-factor construct [

36,

38].

Finally, participants filled out demographic information and were thanked for participating in the study.