Abstract

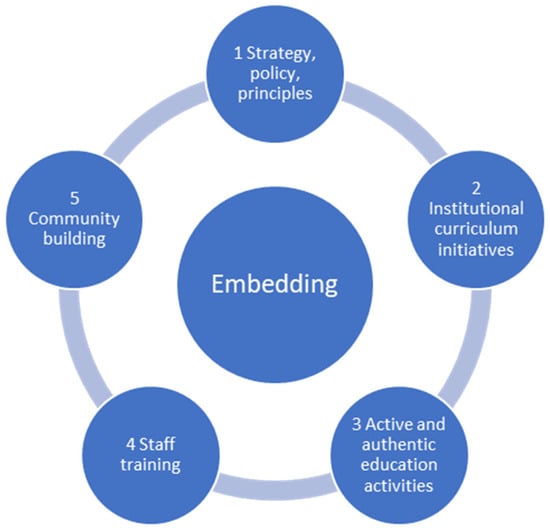

This paper presents a conceptual framework for strategic approaches to embedding sustainability in the curriculum at a large research-intensive university. Due to the evolving nature of universities and technology, this journey is never complete, and this paper presents a case study of our approach to driving the work forward. This ambition is part of the institution’s Environmental Policy to ‘monitor and increase the integration with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) across our operations, research, and education programmes.’ Our conceptual framework to support embedding in the curriculum guides operationalisation across five key domains: 1. strategy, policy, and principles; 2. institution-wide curriculum change; 3. active and authentic education activities; 4. staff development; and 5. community building. For example, an institution-wide curriculum initiative to redesign the Queen Mary graduate attributes framework was developed to include the attribute ‘Promote socially responsible behaviour for a global sustainable future.’ To gain this attribute means that our graduates are exposed to discussions and knowledge concerning sustainability. Across these five areas, we argue that a strategic approach is necessary for successful and impactful embedding of sustainability in the curriculum. Work across each domain needs to be closely linked and interconnected, and to build links with existing policy, strategy, and frameworks. This approach needs to combine high-level leadership together with support for grass-roots initiatives.

1. Introduction

This case study presents a framework and associated initiatives to embed sustainability at one research intensive university in the UK. It describes the positioning and implementation of embedding sustainability in the curricula within the context of the university’s culture. What is presented is conceptual and reflective on implementation; it is not based on data collection. We recognise this limitation; however, the work on positioning the ‘why and how of embedding sustainability’ and supporting educators to achieve embedding provides valuable insights into this journey.

Our university has social justice at its heart and social impact is central to our strategy. Many students and staff join the university as they have a shared desire to understand and improve societal issues. We recognise the link between social justice and environmental impact, acknowledging that environmental issues are rooted in the broader systems of society. Many social justice issues are caused through the exploitation of the environment. This exploitation is visible in the disproportionate impact of climate change in the Global South and marginalised communities as identified by Balaceanu et al. [1] and Ferguson [2]. We address social justice by integrating critical thinking across disciplines. We enable learners to question assumptions, analyse societal issues and power structures, and, where appropriate, pursue solutions. Furthermore, to educate towards social justice, we believe it is crucial to embed sustainability into our education offer.

There is a clear connection between our ambition of embedding sustainability in curriculum and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [3]. In 2017, UNESCO provided guidance for ‘Education for SDGs’ with the aim to, ‘By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development’ [4].

Another consideration is that universities are generally sited in cities; hence, they have a crucial role to play in SDG 11: sustainable cities and communities. Recently, universities have become better engaged with local communities to address sustainability [5,6]. In the UK, a national organisation, AdvanceHE, has published guides and a framework to support universities in embedding sustainable development [7,8]. Our university developed an Environmental Sustainability Policy, which has been updated as of June 2025, and concerns all aspects of the university including its estate, operations, carbon footprint reduction, research, and education [9]. This policy incorporates as its first principle, the aim to ‘monitor and increase the integration with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) across our operations, research and education programmes.’

The embedding of sustainability in education is therefore clearly supported by global UNESCO aims [4], national aims of Advance HE [7,8], and our university aims [9]. This positioning and alignment for a change in curriculum practice is crucial to have engagement across the university. However, we recognise that this embedding still presents a challenge in a large and complex university with a wide range of disciplines and diverse perspectives on the issue of sustainability. Notably, some degree programmes are sustainability-specific and have sustainability or environmental aspects in the degree programme title, such as our Global Business and Sustainability MSc [10]. For other disciplines, the connection is unclear, and educators may not have the know-how for embedding. Hence, a concerted effort is needed to integrate sustainability deeper into these curricula. Saruchera identifies further challenges [11], highlighting siloed discussions and lack of joined-up approaches as barriers. They advocate approaches that span disciplinary divisions. Vogel et al. ([12] p. 29) note that educators’ confidence is crucial to ensure sustainability integration into degree programmes. This observation is supported by Weiss et al. [13], who emphasise that educators’ professional development is a precursor to educational enhancement initiatives.

Drawing on this work, in this article we present our experience of developing a university-wide shared approach. Our approach seeks to address the embedding of sustainability across a wide range of different disciplines. Building on the assertion that educator confidence is key, our approach emphasises the need for educator training and support. Our approach develops established strategies further, arguing that multiple integrated approaches are required across the domains of 1. strategy, policy, and principles; 2. institution-wide curriculum change; 3. active and authentic education activities; 4. staff development; and 5. community building. This article presents a framework articulating this approach, and considers its impact, benefits, and challenges.

There are clear benefits of sustainability education for students, society, and the economy. For today’s students, employability is key, particularly as they often have student loan debt, and they may not have the social capital that previous generations of students had. A recent World Economic Forum report analysed the future importance of sustainability skills for employability, declaring ‘The future of jobs is green’ [14]. Hence, learning about sustainability is advantageous, with increased demand for professionals who have the knowledge and the skills to action and apply sustainable practices [15,16].

This paper demonstrates that, by embedding sustainability in central frameworks and wider initiatives, the university community can access sustainability education, applying it in teaching and learning in a coordinated and impactful way. This process is an ongoing journey for our university and for higher education institutions.

2. Materials and Methods

Our method for embedding sustainability across our 240 academic degree programmes is represented in Figure 1. On considering existing approaches to embedding concepts into the curricula at our university, we identified that these approaches did not have triangulation between the university, the individual, and the student. There was little alignment between the university, educators, and the students’ ambitions and needs. Furthermore, without a cohesive framework, we identified siloed working. Passionate educators were often working in isolation to embed sustainability into their programme but there was no ‘joined up’ approach. Hence, we developed the conceptual framework represented in Figure 1 to ensure all needs were considered. Our framework brings together many of the key drivers for curriculum change identified by Weiss et al. [13]. In developing this approach, we utilised the university strategy and a clear environmental policy. We developed principles of programme design and an ambitious graduate attribute framework for all students. We adopted an active learning approach. We established staff training and development, and initiated a support network for our academic community of staff and students. These areas of development have been informed by consultation with staff and students, undertaken as part of the ongoing evaluation and enhancement of our work within an accepted zone of professional practice, therefore not requiring institutional research ethics approval.

Figure 1.

Strategic approaches to embedding.

2.1. Strategy 2030, Policy and Principles

Geschwind [17] identifies that institutional change requires a clear rationale with a supporting strategy. In 2017, our university established a 2030 Strategy to convey its shared mission, values, and aims for research and education. Alignment with this overarching strategy was crucial for our university community to be able to navigate embedding sustainability successfully. Alignment ensures that the curricula change initiatives directly support the university’s overall mission, values, and long-term aims. Without this, our change efforts could have become fragmented, leading to confusion, wasted effort, and even possible resistance. To support educational development, the university created an academy (Queen Mary Academy), a unit through which educators, professional staff, and students could all work together to achieve educational enhancement across the university. Furthermore, to achieve alignment, our educational leaders, e.g., deans and directors of education, had to be empowered to clearly communicate the strategic objectives behind the change. These leaders needed to demonstrate how the proposed actions will benefit students and the wider community. To ensure cross-university alignment, we created ‘Principles of Programme Design’ for all university educators to follow.

Our programme design principles were designed to guide educational enhancement. Our programmes are always devised considering the students at the centre. These principles direct that graduate attributes are to be embedded in all our programmes. These attributes ensure our students develop the knowledge, skills, adaptability, and resilience to succeed in an ever-changing global job market and become active global citizens.

2.2. Institutional Curriculum Initiative: Graduate Attributes

The first area in which we sought to explicitly connect sustainability to the curriculum across the institution was through creating a graduate attribute framework. These attributes support students’ development for employability and are core to our strategy:

‘The distinctive Queen Mary Graduate Attributes are embedded in all our programmes, so that our students develop the knowledge, skills, adaptability and resilience to succeed in an ever-changing global job market and become active global citizens.’[18]

The university’s strategy highlights the connection between employability and responsible citizenship, and so graduate attributes became an effective approach for driving the embedding of both. These connections provided an opportunity to position sustainability as a vital component of our social justice and citizenship values as Yang and O’Neil stress [19]. It is crucial to develop sustainability skills for our students in the context of the changing global job market. Using graduate attributes to drive whole-institution curriculum change provides an equitable approach to the journey of embedding sustainability, impacting all students, not just those who may choose to study specific sustainability-related modules or programmes.

2.2.1. Developing the New Graduate Attributes

To lead the development of a new set of graduate attributes, we collaborated with colleagues across the institution. We convened a cross-disciplinary and cross-functional group of staff, involving representatives of stakeholders from academic schools/institutes, library services, careers and enterprise, the student union, the technology-enhanced learning team, and Queen Mary Academy. We also secured paid learner internships, which meant that student perspectives were fully presented throughout the process. These internships enabled students to participate in the working committee, take part in workshops, and lead consultations with other students.

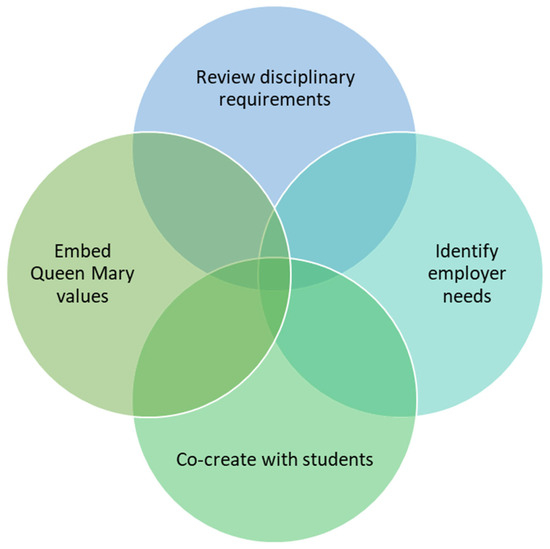

From this diverse group of contributors, a framework for developing new graduate attributes emerged. It was informed by four key perspectives: disciplinary requirements, employer needs, student views, and our values. The recognition of the importance of the disciplines was key to bringing academics on board, as some colleagues were concerned about a lack of clear links between sustainability and their specific subject area. The emphasis on values was vital and enabled us to explicitly position graduate attributes as a value-driven approach that includes employability skills but retains focus on citizenship, social justice, and sustainability.

2.2.2. A Co-Created and Values-Based Approach

In our approach to developing the new graduate attributes (Figure 2), we took inspiration from the concept of ‘co-creation of the curriculum’ developed by Bovill and Woolmer [20]. The authors argue this approach can empower and involve students in a way that runs counter to the kinds of curriculum design models that are ‘done to’ students (p. 419). Graduate attributes are often developed by senior leaders and applied universally within an institution, with our approach offering an innovative alternative. We agreed with the views of Wong et al. ([21], p. 1351), that attributes should incorporate both staff views and the aspirations of students. This was particularly important given consistent findings from the UK student-led organisation, Students Organising for Sustainability (SOS), that approximately 80% of students want their institution to be doing more in terms of sustainability and 60% of students want to learn more about it [22].

Figure 2.

Approach to developing the attributes.

Prioritizing student perspectives in this way also supported buy-in from academic colleagues. Student partners on the project devised ‘student scenarios’ expressing typical challenges students from disciplines face with careers and employability. For example, psychology students can find it a challenge to connect their degree subject to the wide range of careers open to them. This initiative proved an effective way of engaging academic colleagues as students’ individual stories and challenges became the starting point. In addition, highlighting SOS survey findings provided an important way of engaging colleagues with the idea of embedding sustainability.

2.3. Active and Authentic Education Activities

At the heart of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), as defined by the UN, sits the development of transformational learning. This supports students’ development as independent, critical thinkers, able to take responsibility for their actions and decisions [4]. In the guidance developed by Advance HE in the UK, a range of teaching methods are proposed to support ESD. These include project work, problem-based learning, case-based learning, and/or collaborative learning [8]. For example, problem-based learning is based on presenting students with real-world problems to solve, such as ‘waste sort and packaging redesign’; this is one of several examples presented by Advance HE [8]. Learning activities that empower students as active learners will support the development of the UNESCO competencies for sustainability. Hence, learning activities have a vital role to play in embedding sustainability within curricula.

To support embedding strategically, another key approach was to adopt links to our institutional focus on active teaching methodology. In 2022, the university launched a new Active Curriculum for Excellence (ACE) framework. This framework specifies the types of teaching activities that comprise the institutional curriculum: interactive large group sessions, student-paced learning, small active learning groups, and learning by doing. The framework is designed to be applicable to all disciplinary areas and offers a range of activities that might be used as part of each category. For example, the category of ‘learning by doing’ will look very different for different disciplines, and can include lab work, problem-based learning, field work, and seminar debates. Throughout each of these formats, active learning is key. Our education approach prioritises an active student-centred and collaborative approach in large and small group settings. The approach also promotes students’ independence through emphasis on ‘student-paced learning’. The final component introduces vital real-world contexts, problems, and cases through ‘learning by doing’. There is extensive evidence for the efficacy of active learning approaches in higher education [23] but also growing evidence of its important role in education for sustainable development. This research, such as work by Howell [24], emphasises that effective education for sustainable development provides a transformational learning experience that develops student competencies. As such, active learning approaches rather than traditional transmission of information are best suited to embedding sustainability into educational methods.

There are also important connections between active learning, education for sustainable development, and critical pedagogy. As an institution focused on inclusivity and social justice, ACE is also aligned with critical pedagogies drawing on the work of, for example, Freire, Giroux, and Hooks [25,26,27]. Hook’s concept of engaged pedagogy argues that transformative education occurs when student views, experiences, and understandings are valued alongside those of the educator and discipline [27]. In positioning the student as an active learner, ACE can enable student-led pedagogies that support inclusivity and social justice. This is something we see as vital for effective embedding of sustainability, not just through the alignment of pedagogical approach but also because reducing inequality and enhancing equity are core underpinning values of the UNSDGs.

The ACE framework also links closely to our institutional Principles of Assessment Design, ensuring that assessment is aligned to learning outcomes and education activities. Our institution promotes authentic and inclusive assessment design that aligns well with active learning approaches. This focus on active learning is also highly relevant given the current higher education context in terms of generative AI. As a member of the UK Russell Group of research-intensive universities, our institution seeks to engage positively with generative AI and support students to develop AI literacy and skills to engage with these tools critically [28]. However, where assessment needs to focus on assessing skills and abilities outside of AI literacy, authors such as Gonsalves [29] have argued that authentic and inclusive assessment approaches can offer a good solution. Balancing institutional strategies and priorities on sustainability and on engagement with AI is critical.

Through implementing ‘learning by doing’ and authentic approaches, our educators are creating opportunities for students to develop the UNESCO competencies for sustainability through education approaches such as project work, problem- and case-based learning, live briefs, consultancy for organisations, and more. These learning activities may or may not be focused on sustainability as a subject area. Communicating with staff on how these teaching approaches are effective methods for embedding sustainability is key to driving engagement and building momentum behind this work.

2.4. Educator Training and Support

As noted above, for colleagues working in some disciplines, finding the links with sustainability proved challenging and some staff were unsure where to start. To support the embedding of sustainability through graduate attributes, we developed specific training and support for staff in this area. The Queen Mary Academy led the design and development, collaborating with the main Sustainability Team, of a new training workshop for educators. The workshop design drew on national guidance on embedding sustainability [7,8], educational research, and knowledge of the local context. The workshop introduced definitions of sustainability, provided an outline of ESD, and offered a range of strategies, which staff could employ to embed sustainability in the curriculum. Following the UNSDGs [3], the workshop adopted a broad understanding of sustainability through environmental, social, political, and economic lenses. Focusing also on the UNESCO competencies for sustainability provided in their ESD guidance [4] meant that staff from all disciplines could begin to find connections to their discipline and their programmes. The efficacy of the workshop was evaluated using an attendee survey. Participants noted that the key strengths of the workshop included the opportunity to learn from other colleagues’ ideas, and the practical ideas provided for embedding sustainability within their own curricula. All attendees are also invited to join a new staff network (discussed below), connecting them into the sustainability community and enhancing the impact of this standalone workshop. The workshop, which continues to run, has evolved over time through further collaboration with colleagues. Connecting workshop participants with the network provides ongoing support for colleagues.

The development of this staff training also drew on visible demand for enhanced education on sustainability from our students. To complement the national data demonstrating student appetite for sustainability education [21], students were recruited to lead local consultations to explore student views and perspectives. As detailed above, institutional research ethics were not necessary for undertaking this work. However, the research team paid careful attention to remove any potential effects of bias or impact of power imbalances on the findings. The institutional Research Ethics Committee provided a statement of non-objection to this work. The research design was developed jointly with the student partners, who created an anonymous survey and ran a photovoice project. A survey was chosen to provide quantitative data and a broad view of student perceptions; however, participation from students was quite limited. Photovoice was chosen as a participatory research methodology to enable student participants to be part of the research and to use this process to effect change [30]. The survey and ‘photovoice’ elements were open to all current students. Twenty-two students responded to the survey and six students participated in the photovoice project.

The research findings re-emphasised that our students are passionate about learning more about sustainability and do want it to be integrated into their curricula. Less than 50% of survey respondents thought sustainability learning was currently well supported. For respondents, sustainability education was fully interlinked with visible sustainability on campus. Students wanted to see more action on campus, as well as workshops, and explicit support for sustainability from their educators.

Students highlighted the importance of green spaces on campus, their commitment to recycling and reducing waste, and were aware of the skills they will need to enter a workforce where sustainability literacy is becoming increasingly vital. For the student participants in the research, the top sustainability skills identified were teamwork, problem solving, ethics, communication skills, and critical thinking. In our experience, educators are always dedicated to supporting their students in the best way that they can. Therefore, the findings from this student research are a useful way of gaining buy-in from staff, as well as highlighting some key sustainability skills, which align well with the graduate attributes that staff can integrate into their curricula.

2.5. Building a Community

Through delivery of the workshop and discussion with colleagues, it was clear that many examples of excellent practice in embedding sustainability existed across the institution. Educators who were personally passionate about sustainability were incorporating this into their teaching in innovative ways. However, there was no central guidance or advice for educators outside of the workshop that we had developed. To build towards more strategic integration of sustainability into the institutional curriculum, we began to develop a new staff network for sustainability in the curriculum: Sustainability in the Curriculum Action Network (SCAN). The aims of the network are to identify and share good practice, and to connect colleagues from across disciplines. The network exists as an online MS Teams community, facilitating open sharing of information, events, and opportunities.

Complementing this, the network runs specific events, both online and in person, where members are asked to join and share brief presentations outlining their own practice in embedding sustainability. For example, a recent event saw presentations from colleagues working in engineering, mathematics, medicine, and politics share brief case studies illustrating how they embed sustainability in their teaching. Establishing clear aims for this network has been crucial in enabling us to evaluate its effectiveness. Evaluation of network activities considers the impact of specific events, and network participation more generally, on individuals. For the future we also seek to explore methods for evaluating the impact of the network and the community-led approach on institutional priorities for sustainability. This includes identifying examples of best practice and creating tangible, written case studies to be shared.

3. Results/Outcome

The strategic approaches described above have been implemented, and the outcomes of the work in these five areas are described below.

3.1. Principles of Programme Design

The following seven programme principles have been developed to support educators in delivery of our education strategy [31].

- Clear programme leadership: to have clear accountability of success and development of programmes and the modules within the programmes.

- Coherent programmes: to have clear pathways for students; to be able to understand the student journey and to improve it. All programmes have core/compulsory modules and clear pathways for students to select electives.

- Clear programmes aims and programme level outcomes: to understand and communicate the students’ learning of knowledge, skills, and behaviours for the discipline of study.

- Programme Assessment Mapping: to understand the assessment load for students, to ensure assessment maps to the outcomes and to avoid overassessment.

- Programme teaching and learning approaches: to ensure active learning and that students see and experience the expected learning approach and are engaged.

- Planning staff contact: to clearly articulate to students the expected contact with staff.

- Employability: to ensure all programmes address employability and embed the graduate attributes and hence sustainability.

Educational leaders across the faculties have been reviewing programmes to ensure alignment and integration of these principles. The principles have provided a shared understanding of the requirements for a degree programme at our university.

3.2. Institutional Curriculum Initiative: Graduate Attributes

Through the collaborative efforts of the graduate attributes working group and extensive consultation and collaboration with staff, students and employers, 13 graduate attributes were developed as shown in Table 1. These attributes are aligned to our values, inclusive, proud, ambitious, collegial, and ethical, and include a specific attribute related to sustainability: ‘Promote socially responsible behaviour for a global sustainable future’.

Table 1.

13 Graduate attributes aligned to Queen Mary (QM) values.

As part of the guidance for the implementation of the framework, we included the requirement that all programmes embed at least one attribute related to each value including an attribute related to sustainability. Implementation of the embedding of the graduate attributes is monitored through the Programme Design Principles, which are reviewed via a central quality assurance process (continuous programme review).

3.3. Educator Training and Support

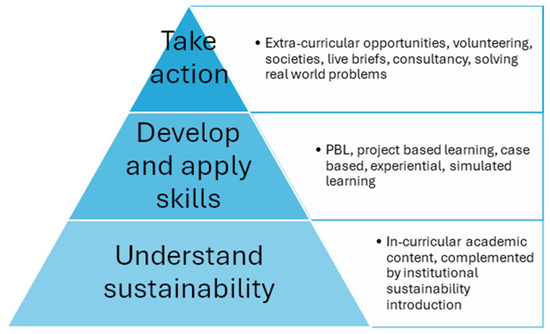

Through feedback and discussions in the staff training workshop, as well as reflection on the research with students, a clearer framework for embedding sustainability and supporting students’ sustainability literacy (Figure 3) was developed.

Figure 3.

Towards an institutional sustainability literacy framework.

We wanted to articulate a progressive developmental approach to supporting student sustainability literacy in a framework that was easily applicable to the practice of all educators, regardless of their disciplinary area. The workshop presents the framework to enable staff to better understand how their role integrates with this university-wide approach. At the initial level, we want to enable students to understand sustainability. This might come through in-curricular academic content, particularly where there are clear links to specific disciplines (e.g., geography, biology, earth sciences), or through other introductory training on subject knowledge related to sustainability.

The second level of the framework promotes deeper integration, which is primarily through linking the skills and graduate attributes development of students to the UNESCO competencies for sustainability. This requires developing the skills that students will need to successfully contribute to solving the challenges of sustainability. This might be achieved through the integration of a range of specific teaching methods (e.g., problem-based learning, project-based learning, experiential or simulated learning). The topics, problems, or cases chosen may relate to sustainability, contributing to students’ deeper understanding of the area, but the experience of learning through these methods supports the development of sustainability skills and competencies.

Finally, the third level of the framework aims to inspire students to act for sustainability. This might be through extracurricular activities, personal actions, or volunteering. This level of the framework should be accessible to all students through integration into programmes of study. Doing so would provide opportunities to work on real-life problems, through consultancy for organisations or other authentic sustainability-related activities. This Living Lab approach presents an opportunity to connect students with current working sustainability problems, comparable to the approach taken by Manchester University [32]. Here, linking with the university careers service would be key to providing relevant connections.

This framework is closely linked to the ACE education approach. Both approaches are aligned and work in parallel. This enables staff to fulfil both alignment to the ACE approach as well as embedding sustainability at once, with the coordination of strategies strengthening the integration and impact of the literacy framework and ACE.

3.4. Building a Community

The Sustainability in the Curriculum Action Network’s first sharing practice event took place in late 2023 and brought together presentations from both internal and external educators working in medicine, engineering, biological sciences, and computer science as well as contributions from our Students’ Union. The network has brought together passionate individuals often working in isolation across the university. Aligning these efforts has enabled us to harness passion and drive in a coordinated way. The staff network now has over 70 members. Connecting with other institutions’ education networks provides scope for further development and sharing of practice. This is something we hope to take further through collaborative events and engagement. The network events and discussions have led to a growing collection of examples of practice, now shared across the institution via the QMA and QMUL Sustainability websites, tagged with relevant UN Sustainable Development Goals, to inspire other educators. Examples of embedding include the following:

- -

- Introduction of new sustainability focused programmes across the disciplines such as MSc Sustainable Energy Systems, LLB Law and Climate Justice, and MSc Global Business and Sustainability.

- -

- Co-creation of climate change analysis in the mathematics curriculum (Dr. Chris Sutton) [33].

- -

- Students as case protagonists: students reflect on personal experiences to inform solutions to real challenges in sustainable marketing (Dr. Sayed Elhoushy) [34].

- -

- Empowering students for sustainable development: embedding sustainability alongside academic study skills in geography (Dr. Stephen Taylor) [35].

- -

- Design of group consultancy projects to solve a real sustainability challenge for industry in business and management (Dr. Georgy Petrov) [36].

Drawing on these diverse examples of practice together through the sustainability literacy framework has enabled us to empower and encourage academics across the university in a more impactful way.

4. Discussion

Universities are well placed to develop a tertiary level understanding of sustainability and to educate students to become future leaders of sustainability agendas. However, the university must first show leadership in sustainability matters to share and develop the knowledge, skills, and behaviours required in its community. Universities are large, complex organisations, with degrees of autonomy adopted within faculties, schools, and departments. To navigate this, specific strategic tools need to be co-implemented, bringing alignment across the range of disciplines to embed sustainability effectively. Such tools should range from clear overarching strategy—supported by policies enshrined in the governance structure—to specific principles, frameworks, and staff training that gives guidance on implementation. Aligning and integrating sustainability approaches with existing university strategy, priorities, and training programmes is also key to ensuring a connected approach.

4.1. A Community-Led Approach

Across each of these initiatives, engaging, and working collaboratively with our community has been vital. For example, the successful implementation of the new graduate attributes has, we believe, been in large part due to the wide, consultative, and collaborative process that led to their development. Indeed, the inclusion of the sustainability attribute was debated and its position in the final attributes’ framework is due to the passionate advocacy from diverse voices within the group. Being supported by the university community, this attribute is more authentic and more powerful in its roll out across the institution.

Community-led approaches are often limited by time, with pressure to ‘go faster’. From our experience, time is needed to authentically engage with and bring the community with you. Time is needed not only during engagement, but also to establish the community, particularly in instances where cohesion is low. Having top-down fast-delivered concepts can seem to be the most efficient, but this often leads to a lack of buy-in, ownership, and poor delivery. We learned that giving time to debate and reflection was crucial. By taking such approaches, fosters the mindset of something that is happening ‘with’ rather than ‘to’ the institution’s education community.

The staff network grew out of a collection of unconnected individuals who were doing great work to embed sustainability in their teaching independently. Working as partners with these colleagues to establish the network and build its aims and approaches has meant harnessing this drive and passion and creating a more powerful voice together. Engaging colleagues in a diverse range of roles, including sustainability professionals, educational developers, academics across disciplines, and the Queen Mary Students’ Union, to support embedding has been crucial.

Developing the staff network has proved to be an ongoing challenge. Particularly in the early stages, it was difficult to secure engagement from colleagues because this was a voluntary, additional area of work at a time when they were already very stretched. We were relying on the goodwill and dedication of passionate individuals. Drawing on a communities of practice approach [37], we sought to try and empower community members to take ownership of the network through leadership positions which recognised their contributions. However, securing resources and recognition of the work colleagues contribute to such networks is a persistent issue.

4.2. Integration of Existing Strategy and Making Connections

We have found it vital to ensure that work to embed sustainability is fully integrated and aligned with existing educational strategies at the university. Both the Strategy 2030 and the Active Curriculum for Excellence emphasise the vital importance of inclusive and active educational approaches. Through making connections to education for sustainable development goals explicit, we have aligned institutional priorities with embedded sustainability at the level of the teaching methods and education experience for our students. Sustainability has also become a core thematic area of a new employability framework bringing together the integration of experiential or work-based learning in the curriculum with sustainable challenges, topics, and organisations. Embedding sustainability in the curriculum is also a core topic within our Postgraduate Certificate in Academic Practice, the central training programme for all new academic members of staff. These new educators leave the course equipped with knowledge and skills to embed sustainability within their own teaching, and to advocate for this more widely with colleagues in their departments.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents the approaches that our university has taken so far to embed sustainability into the curriculum, in line with our institutional aims to promote social justice and social mobility. By no means is this a complete journey. Looking forward, the institution has developed an ‘Action Statement’, covering the next three academic years, acknowledging the need for continued efforts in this area. It sets out key objectives and targets ensuring the coordinated and targeted integration of sustainability across all university programmes. Ultimately, it is a cohesive combination of both top-down and grassroots approaches that is needed. Staff and students should be encouraged and empowered to champion sustainability within their own roles. This approach ensures that embedding sustainability is done together with our university community and not to our community. We have a responsibility to continue this work, and to continually revisit our approach so that our students are equipped as well as possible with the knowledge and skills to act.

This paper has presented a conceptual framework for supporting embedding in the curriculum which is operationalised across five strategic areas: 1. strategy, policy, and principles; 2. institution-wide curriculum change; 3. active and authentic educational activities; 4. staff development; and 5. community building. Across these five areas, we argue that a strategic approach is necessary for successful and impactful embedding of sustainability in the curriculum. Work across each domain needs to be closely aligned and interconnected, and to build links with existing policy, strategy, and frameworks. Our approach is anchored in key themes: co-creation, authentic learning, community building, programme design fundamentals, and graduate attributes. The power in our approach lies in its focus on participatory practice, meaningful student engagement, and a multidisciplinary perspective.

Embedding sustainability into the higher education curriculum requires the integration of well communicated strategic approaches and support to bring together the work of individual educators, harnessing their passion but coordinating their contributions into a focus for university-wide action. Sustainability must not be seen as a separate endeavour but fully connected and intertwined with overarching guiding education strategy, policy, and principles.

This case study has explored the approach adopted by one large research-intensive university. Our framework holds together elements that have been previously identified as crucial for curriculum change, such as university strategy and professional development for staff. However, it expands these to have beneficial elements for students such as clear graduate attributes for employability. Other universities seeking to embed sustainability can use our conceptual framework to reflect and adjust their approach.

Author Contributions

J.D.W. has led the development of strategic approaches to implementation of educational initiatives. S.F. has led the working groups developing graduate attribute and sustainability networks. Z.S. leads on strategic engagement and collaboration for sustainability at Queen Mary, including embedding sustainability into the curriculum and sustainability networks. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the study being undertaken as part of the ongoing evaluation and enhancement of our work within an accepted zone of professional practice.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members of the Queen Mary Academy and the Sustainability Network for their support in embedding sustainability in the curriculum. We would like to acknowledge the contributions of our students to the co-creation of graduate attributes, and to the 2025 sustainability learner interns who conducted research into student views of sustainability education: Najia Ahmad, Dawud Hussain, and Shruti Sabnis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACE | Active Curriculum for Excellence |

| QMUL | Queen Mary University of London |

| QMA | Queen Mary Academy |

| QM | Queen Mary |

| PPDs | Principles of Programme Design |

References

- Balaceanu, C.; Apostol, D.; Penu, D. Sustainability and social justice. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 62, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, T. Advancing Sustainability and Social Justice: A Role for Higher Education Institutions; Pursuing Social Justice Agendas in Caribbean Higher Education: Routledge, UK, 2025; pp. 226–242. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. 2017. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/education-sustainable-development-goals-learning-objectives (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Morini, C.; Inacio Junior, E.; Azevedo, A.T.d.; Sanches, F.E.F.; Avancci Dionisio, E. Vertically integrated project: Uniting teaching, research, and community in favor of sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2025, 26, 672–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankseliani, M.; Qoraboyev, I.; Gimranova, D. Higher education contributing to local, national, and global development: New empirical and conceptual insights. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advance HE. A Five-Step Framework for a Whole-Institution Approach to Embedding ESD. 2021. Available online: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/five-step-framework-whole-institution-approach-embedding-esd (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Advance HE. Guide to ESD in Practice. 2024. Available online: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/guides-esd-practice (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Queen Mary University of London. Sustainability Action Plan and Environmental Policy. 2024. Available online: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/about/sustainability/policy-and-strategy/action-plan-and-policy/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Queen Mary University of London. Global Business and Sustainability MSc. Available online: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/postgraduate/taught/coursefinder/courses/global-business-and-sustainability-msc/ (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Saruchera, F. Sustainability: A Concept in Flux? The Role of Multidisciplinary Insights in Shaping Sustainable Futures. Sustainability 2025, 17, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, M.; Parker, L.; Porter, J.; O’Hara, M.; Tebbs, E.; Gard, R.; He, X.; Gallimore, J.B. Education for Sustainable Development: A Review of the Literature 2015–2022. Advance HE. Available online: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/education-sustainable-development-review-literature-2015-2022 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Weiss, M.; Barth, M.; Wiek, A.; von Wehrden, H. Drivers and barriers of implementing sustainability curricula in higher education—Assumptions and evidence. High. Educ. Stud. 2021, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs Report 2025. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2025/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Albertz, A.; Pilz, M. Green Alignment, Green Vocational Education and Training, Green Skills and Related Subjects: A Literature Review on Actors, Contents and Regional Contexts. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2025, 29, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organisation (ILO). Navigating the Future: Skills and Jobs in the Green and Digital Transitions: Scenario-Based Insights. 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.54394/VGNR3350 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Geschwind, L. Legitimizing Change in Higher Education: Exploring the Rationales Behind Major Organizational Restructuring. High. Educ. Policy 2019, 32, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queen Mary University London. Strategy 2030. Available online: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/strategy-2030/ (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Yang, X.; O’Neil, J.K. Social Justice in Sustainable Development. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovill, C.; Woolmer, C. How conceptualisations of curriculum in higher education influence student-staff co-creation in and of the curriculum. High. Educ. 2019, 78, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, B.; Chiu, Y.L.T.; Copsey-Blake, M.; Nikolopoulou, M. A mapping of graduate attributes: What can we expect from UK university students? High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2002, 41, 1340–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Students Organising for Sustainability. Sustainability Skills Survey. 2023. Available online: https://www.sos-uk.org/research/sustainability-skills-survey (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Freeman, S.; Eddy, S.M.; McDonough, M.; Smith, M.K.; Okoroafor, N.; Jordt, H.; Wenderoth, M.P. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, R.A. Engaging students in education for sustainable development: The benefits of active learning, reflective practices and flipped classroom pedagogies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 325, 129318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H.A. On Critical Pedagogy; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. Teaching to Transgress; Routledge Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Russell Group. Russell Group Principles on the Use of Generative AI Tools in Education. 2023. Available online: https://www.russellgroup.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2025-01/Russell%20Group%20principles%20on%20generative%20AI%20in%20education.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Gonsalves, C. Contextual assessment design in the age of generative AI. J. Learn. Dev. High. Educ. 2025, 34, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queen Mary University of London. Principles of Academic Degree Programme Design. 2024. Available online: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/governance-and-legal-services/media/dgls-media/policy/2024-25/Principles-of-Programme-Design-(October-2024).pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- University Living Lab. Available online: https://www.universitylivinglab.org/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Sutton, C. Working with Students to Embed Climate Change Analysis in the Maths Curriculum. Available online: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/queenmaryacademy/educators/resources/sustainability-in-the-curriculum/case-studies/working-with-students-to-embed-climate-change-analysis-in-the-maths-curriculum/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Elhoushy, S. Students as Case Protagonists: Empowering Students Through Connecting Personal Experiences with Sustainability Challenges. Available online: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/queenmaryacademy/educators/resources/sustainability-in-the-curriculum/case-studies/students-as-case-protagonists-empowering-students-through-connecting-personal-experiences-with-sustainability-challenges/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Taylor, S. Empowering Students for Sustainable Development: Embedding Sustainability Alongside Key Academic Study Skills in a First-Year Undergraduate Module. Available online: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/queenmaryacademy/educators/resources/sustainability-in-the-curriculum/case-studies/embedding-sustainability-in-the-geography-and-environmental-science-curriculum/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Petrov, G. Working Together in Groups to Develop Solutions to Real Business Challenges. Available online: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/queenmaryacademy/educators/resources/sustainability-in-the-curriculum/case-studies/authentic-assessment-design-for-large-first-year-module/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).