Abstract

This article focuses on graffiti and street art analysis in green areas from Romanian cities. Whether it is about the invasion or anticipated integration of urban artworks in green areas, in recent years, the phenomenon of urban art has become undoubtedly visible and finds its place among other components of artistic interventions. This study aims to diagnose various forms and expressions of urban art in the parks of several case study cities from Romania and to evaluate the urban art rapport with the parks’ organization. The methods used combine field research to identify spots with urban art, typologies based on different criteria, documentation for primary or supplementary explanations about the reality identified in the field, and results mapping using GIS tools. This study’s main findings are in relation to the location and preferred surfaces in the investigated parks for graffiti and street art works; hence, the main types of urban art and the messages transmitted. The results obtained highlight the idea that there are differences and gaps in terms of urban art phenomenon evolution reflected in diverse approaches of urban art and different balances that impact the parks’ image.

1. Introduction

Street art is nowadays a common socio-cultural phenomenon in urban landscapes, and it is developing as an answer to economic and spatial transformations. Its framing depends on local societal contexts and development directions that cities experience; therefore, it has a varied perception status as culture, subculture, or counterculture. Street art may be perceived as a fluid art [1], transiting from street culture to mainstream [2]. As urban art practice [3], street art includes graffiti and other forms of public expression [4]. Main stages in graffiti and street art evolution may be identified on a temporal scale [5]: the 1950s—an initial stage of using stickers, inspired by advertising, in which stickers are used to tag a surface without writing; the late 1960s—the first tags in Philadelphia and New York City; the 1970s—spraying of letters, nicknames, and tags come with first anti-graffiti laws; the mid-1970s—development of more complex methods and painting techniques; the 1980s—hip-hop, rap, punk, and rock culture enhance more durable to already existing slogans (political, social, etc.); the mid-1980s—more laws and restrictions in terms of interventions and materials used; the 1990s—development of different styles of graffiti in Europe; after 2000—graffiti evolves together with street art.

The differentiation between graffiti and street art may be imperceptible [6] and often arbitrary [7] because it is challenging to categorize artworks in all cases despite specific differences that separate the two streams and which are given by [5]: the nature of the intervention (legal versus illegal artworks), types of visual representations, capability in decoding the messages, motivation of intervention, and impact in the landscape, etc. What is certain is that graffiti represents the roots of many forms that are perceptible today in diverse styles, shapes, and templates that have emerged over time [8,9]. However, three categories are recognized and accepted in general. Graffiti, muralism, and art installations are often considered street art [1]. Graffiti may conflict with street art at least from the interventions’ nature point of view, respectively, unauthorized interventions and being associated with vandalism versus legal surfaces [10,11,12].

The hosting surfaces of urban art interventions are abundant, including many components of the urban infrastructure: fences, gangways, abandoned buildings, walls, depots, garages, shutters, billboards, fire alarms, benches, posts, cars, trucks, wagons, etc. [6,13,14]. There are studies with different scientific approaches focusing on various geographical areas that analyze the surfaces hosting graffiti and street art works. Some of them are more discussed than others, like the walls [15,16,17], wagons [14], or abandoned industrial buildings [18]. Other studies include narrower research, such as graffiti works on bridges [19] or the impact of graffiti on trees [20].

Green areas are an important component of public spaces and give identity to human settlements [21], being recognized through multifunctionality, a complex system, with social and environmental services and functions, and contributing to improving the quality of life [22,23,24]. They are perceived as well as a “social space” in which natural and cultural elements next to infrastructure development represent the basic factors that determine the recreational potential of an area that allows and favors different ways of spending free time [25], having particular importance on the development and maintenance of human’s psychological and physical balance [26].

Street art is part of public art, an artistic expression created in streets, squares, and other public spaces, including parks [27]. So, green areas have renowned functional aims: biological, recreational, and, not least, aesthetic [28]. Therefore, to the basic function of parks, urban forests, or other green spaces or areas, namely, relaxation and spending free time, the artistic function is added, often associated with the conservation of the place’s identity, local heritage values, or local social and economic past.

In this context, new green areas that integrate street art develop either in natural spaces or following partial or complete transformation of areas that previously had another function. At the international level, there are many examples of projects of this type developed in recent years: e.g., (a) Street Art City—in the central part of France, on the premises of the former Administration of Posts, Telegraphs and Telephones training center, abandoned for around twenty years, a project started in 2017 by transforming all the area surrounded by natural landscape, into a unique place in the world dedicated to street art: on over 10 hectares and 13 buildings with a surface area of 7000 m2, there are nearly 40,000 m2 of exterior and interior frescoes [29]; (b) SPOT project—in Île-de-France region, scheduled for inauguration in 2025 and which will involve renaturing and developing the abandoned areas of the A4 motorway, by creating an urban forest with 33,000 new plants, a new gymnasium and recreational sports areas, a municipal technical center, and an intercommunal museum. The sports and leisure area will be freely accessible under the highway deck. International artists will contribute to transforming this abandoned place into an open-air museum, with frescoes in diverse styles around unifying themes: nature, sport, inclusion, heritage, and the history of the city [30]; (c) in different urban regeneration projects, street art movement is considered in relation to green development and environment protection: for example, in Heerlen city in the Netherlands, murals were the solution to redesigning public spaces by re-using materials and creating artworks with green patches [31].

Graffiti and street art phenomenon in relation to nature may be understood in a multifaceted context, not only in direct relation to green areas as the location of artworks. It is common for different components of the natural or artificial environment to be used as surfaces for art interventions. However, nature may be just a source of inspiration for artistic representations (similar in painting or sculpture), or elements from nature may be used as raw material in creating artworks. Therefore, in the last two decades, a series of terms were introduced to express a new direction in the evolution of street art in relation to nature.

Green street art, born in the 2000s, is based on raising and defending the environmental cause and the ecological transition, with artists bringing urban art and natural elements together. In some cases, natural elements are integrated into different artistic representations, e.g., ephemeral creations drawn with chalk or charcoal on the ground [32], combining work in situ in an urban area with the influence of nature [33]. Grass graffiti and eco-street art are other terms used starting with the 2000s, an art practice which consists of painting a wall with a mixture of plant moss to transmit a message [34] and sometimes doubled by using exclusive eco-materials.

Regardless of the term used—green street art, grass graffiti, eco-street art/eco-graffiti, green art [35], vegetal street art [36], or just green intervention [37]—the cause is the same, and the representations are linked to activism for the environment and through art.

Graffiti and street art trends represent only one component of the artistic interventions in green areas and join older interventions from categories such as sculptures or monuments. Today, both delimitations from other arts and inside graffiti and street phenomenon may seem difficult to appreciate. For example, green street art is a type of art close to land art, a trend in contemporary art using the framework and materials of nature, outdoors and therefore exposed, shortening their lifespan, to create giant frescoes by using biodegradable paint, respecting nature [38] by bringing, at the same time, an artistic and reflexive vision of the landscape [39] or close to trash art concept, based on recycling and waste transformation into diverse artistic objects [33].

Developing street art in urban parks and squares is seen as one of the future trends of graffiti mural art in public spaces [2]. Street art is increasingly included in urban regeneration projects to return public spaces to the population, including through planning and development projects of new urban green and recreational areas.

The purpose of this study is, on the one hand, to appreciate the various forms of urban art existing in the parks of several case study cities from Romania, diverse in size, historical and socio-economic evolution and, hence, registering perhaps differences in the approach to graffiti and street art and, on the other hand, the assessment of urban art contribution to parks’ equipment, organization, and their resulting visibility and “reputation”. The main research question is to evaluate the urban art rapport with the parks’ organization.

The authors consider the findings in this article as the public discourse, reflected in appreciations and complaints about different aspects of life, as it is “voiced” through inscriptions and artworks free of expression. This article seeks to appreciate the reflection of society’s issues on different surfaces in the analyzed parks without constraints, and therefore, does not search their current and more complex population perception or the authors’ motivation; that can be assessed as a second investigation step and only by using qualitative methods, a more common research approach, which may represent the purpose of a future study.

Lately, urban art has proven to be an essential tool for enhancing sustainability in urban areas. A series of studies highlight the contribution of urban art as a solution in supporting, directly and in the framework of urban regeneration projects, the economic sustainability of areas impacted by various economic processes, especially deindustrialization and production sites’ abandonment [40,41]. The urban art contribution becomes more visible when the street art component intervenes as an antidote to the negative image and non-functionality of different places, being accompanied by cultural meanings, creativity, and new ideas for temporary transformations of these places [42], or even participating to complete the regeneration of neglected spaces, sometimes becoming a response to social exclusion [43]. At the opposite pole, graffiti-type interventions may act as a delay or blockage for a specific period in the evolution of places and even lead some urban environments to project strategies of graffiti zero-tolerance [44]. From a social point of view, urban art may be associated with community expression and engagement [45] and both cultural and socioeconomic aspects from a place attachment perspective [46]. Environmental sustainability is also a target of urban art when it deals with eco-graffiti [35] or contemporary mural conservation [47]. Moreover, regardless of the angle from which urban art is studied in relation to sustainability (projects, artworks’ location, investments, actors involved etc.), the power of the messages transmitted through street art and graffiti interventions may play a meaningful role in communities, impacting directly or indirectly the economic perspectives, social evolution, and environmental protection.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology applied in this study is a complex one and included several stages applied at the level of the three parks: (I) field research for the identification of spots with graffiti and street art and their classification into different categories relying on an international typology in the scientific literature [48] and according to a worksheet used which included the following sections: (A) types of surfaces (supports): benches (1); stairs (2); poles (3); asphalt (4); authorized spaces for garbage collection (5); electricity transformation substations (6); gas substations (7); bicycle racks (8); windows (9); doors (10); shutters (11); fences: residential (12), industrial (13), fences of some restaurants, terraces, bars (14), abandoned fences and other types (15); other types of fences (16); passages (17); bridges (18); walls: residential (19), industrial (20), walls of some restaurants, terraces and bars (21), abandoned walls (22), and other types (23); panels (24); other components (25); (B) location: playgrounds for children; sports places for adults; elderly relaxation places (chess tables, etc.); sports grounds; alleys; other spaces; (C) types of messages: political, economic, social, cultural, communication, advertising, other types; (D) types of urban art: tag; throw up; bombing; graffiti jam; knitting graffiti; paste-up; stencils; stickers; masterpiece; mural; other writing style. (II) Documentation from different informational sources regarding the works identified in the field, an important stage which completes stage A for a correct work’s framing, but also regarding the origin context (on the occasion of an event, economic investments in the area, spontaneous intervention, etc.), year of the work and the author, etc., from publications and mass media, including legislative documents to understand the cities’ policy regarding urban art. (III) Mapping by georeferencing field data and obtaining thematic maps regarding the Kernell density and urban art typologies (by surfaces, messages transmitted, and representations) using ArcGIS Pro 3.1.1. software. (IV) Google Street View to complete information, considering that it is an ephemeral art. Images from the past may be beneficial for comparative analysis that provides information about the phenomenon’s evolution.

This study does not intend to associate the various representations in authorized art or vandalism interventions. It relies on a study of legislation in force and different events in the three cities that address urban art directly or include urban art among the components.

Following the field research to identify graffiti works, street art, and installations in the three analyzed urban parks, the following characteristics were searched: hosting surfaces, location, type/s of message/s transmitted, and styles of urban art (studied individually or in correlation, e.g., between a specific type of surface intervention and type/s of message/s transmitted, etc.).

3. Results

3.1. The Parks’ History and Relationship with the Graffiti and Street Art Phenomenon

The case studies are represented by three parks from three Romanian cities of different demographic size. The first case study comes from Bucharest, the capital of Romania, a city with a population of over 2 million inhabitants, including its metropolitan area, the main administrative, cultural, and economic urban center of the country, which has undergone continuous changes in architecture and economy after 1950. The second selected park is from Iași, the most important city in the historical region of Moldova, the former capital of this region and the capital of the Romanian United Principalities between 1916 and 1918. Nowadays, Iași is the second most populated city in Romania, which, together with its metropolitan area, has over 500,000 inhabitants, the second largest metropolitan area in Romania. Bacău, with the third case study park, is an important city at the regional level, also within the historical region of Moldova, with a population of about 130,000 inhabitants and a significant industrial past.

All three cities experienced growth and development during the communist period through territorial systematization actions that led to the emergence of green areas in the newly built neighborhoods for industry workers. The parks considered in this study are the largest in the analyzed cities and have historical importance: Copou Park from Iași was inaugurated in 1834, Herăstrău Park from Bucharest in 1936, and Cancicov Park from Bacău in 1938. All of them were significantly reconsidered in terms of organization and size in communist times.

Bucharest has more than 70 parks and gardens, including small ones, which offer a comforting atmosphere of recreation and leisure, both for residents and tourists [49], important for everyday life and bringing a benefit to the elderly, children, people with various conditions, primarily through the multitude of recreational facilities, such as the need for socializing, outdoor recreation, reading or rest, as well as to other categories, such as young people, who usually prefer weekend walks or practicing various sports [50].

With time, the destruction caused by World War II and natural disasters left their mark on Bucharest’s urban landscape and implicitly on the green spaces. The only ones that resisted were the large parks and gardens, which had much larger surfaces and were better integrated in the landscape, namely, Herăstrău Park, Cișmigiu Garden, Kiseleff Park, Botanical Garden Park, and Carol I Park.

During the communist period, decisions were made to reconstruct and redevelop existing parks and organize new green areas in Bucharest, which led to an increase in parks [50,51,52,53,54]. However, in recent years, green areas have been substantially reduced, and vast residential neighborhoods have been built in their place. This has led to a drastic reduction in green area per inhabitant and increased pollution in the city [49]. Regarding the structure of green areas in Bucharest (which comprises six administrative districts called sectors), Sector 1 has the most extensive vegetation coverage (1757.7 ha).

- Herăstrău Park (the current name, since 2017, is “Regele Mihai I”/“King Mihai I” Park, but the authors will refer to its name of Herăstrău Park as it is preserved in the collective memory) is located in sector 1 and occupies the largest green surface in Bucharest, with an area of 206.9 ha.

Herăstrău Park, the largest in Bucharest and Romania, was settled in 1936 by reclaiming a marshy area (between 1930 and 1935) [55], on an area of 187 ha, on both banks of the artificial Lake Herăstrău (77 ha). In 1936, the Village Museum was inaugurated in the area of Herăstrău Park (currently occupying an area of 15 ha), one of the largest institutions of its kind in Europe, which highlights, through specific means, all the ethnographic and folkloric wealth of the population from different regions of Romania. In the second half of the 20th century, the park was organized into two main areas with different destinations. One area is dedicated to enjoy the calm and culture with two theatres, one for children and one for adults (The Summer Theater, located next to the Village Museum, opened in 1956 and with a capacity of 2500 seats, with pavilions for exhibitions, libraries, and a shade house dedicated to reading or chess), a Japanese garden inaugurated in 1998 and a central monument dedicated to the European Union on the Island of Roses. The other area is dedicated to those who want to spend their time actively with different sportive activity options (a golf course, clay tennis courts, football fields, nautical and sports clubs, etc.) and has numerous recreational facilities, including restaurants and cafés. Throughout its history, the park changed its name to National Park, Carol II Park, and I. V. Stalin Park. While it had this last name, at the entrance to the park, between 1951 and 1962, a statue of Stalin was placed; since 2006, in the area, the statue of Charles de Gaulle can be observed [56] as a symbol of Romanian–French friendship relations and of Francophonie importance for Romania.

- Copou Park has an area of 10.1 hectares and was settled between 1833 and 1834 as the main promenade favorite of high society. In the 19th century, it was also known as “Podu Verde” (Green Bridge) because of the numerous trees (linden, ash, maple, palm), some of which are centuries old, which still today give the park specificity and uniqueness. Throughout its existence, the park has undergone several stages of organization, reaching its maximum surface area (19 hectares) towards the end of the 19th century.

The park is located in the northern part of the city, along a very important boulevard—Carol I Blvd.—that crosses the city from its central part to the north, being considered as an important tourist area and the central axis of the greenest district of the city [57,58]. The Copou neighborhood has an area of about 700 hectares and a population of nearly 10,000 inhabitants. At 500 m from Copou Park, along the same axis, is the Exhibition Park (5 hectares), opened in 1923 on the occasion of an agricultural exhibition, and in the north-west of the Copou is the Botanical Garden, the oldest institution of its kind in the country. The new real estate developments are expected to lead to a substantial increase in population density and buildings in the Copou neighborhood in the coming years, which may impact the road traffic and the overall quality of life.

The park’s architecture is mixed. A wide alley leads from the main entrance to the central square, where several tourist attractions are located. A series of secondary alleys branch off from the central axis, with paths adapted to the existing topography, water surfaces, vegetation, and points of interest for visitors, all of which reinforce the park’s “English garden” identity.

Copou Park is home to some tourist attractions of great interest, such as Mihai Eminescu’s Linden Tree (one of the oldest and most important monument trees in Romania, over 460 years old), the Organic Regulation Monument (known as the Lions’ Obelisk, 1834), the Mihai Eminescu Museum, and the Mihai Ursachi Cultural House. The building that houses these two cultural institutions was completed in 1989, replacing an older construction, an Austrian-style wooden pavilion from the late 19th century. In 2023, the zonal commission of historical monuments made a favorable decision to request that Iași City Hall classify Copou Park as a historical monument.

- Cancicov Park is located in the central-western part of the city of Bacău, between the city’s main road (Mărășești Avenue) and the Bacău–Bucharest railway. The park has an irregular outline with a large east–west extension in its northern part and a narrowing in its southern area [59]. The central municipal park of Bacău was founded and planned in 1935 under the conditions of the exploitation of land won by the municipality following the agrarian reform of 1921–1924, and then resystematized during the communist period when it changed its name to Freedom Park. The 21.87 ha park is accessible through 10 entrances distributed on all sides of the approximately 3 km perimeter. From a functional point of view, the park benefits from the proximity and complementarity of the central area of Bacău, which has an administrative and service profile, from the vicinity of an extended area with a medical profile and numerous school and high school educational institutions nearby, the County Library and the Museum of Biological Sciences, but also the vicinity of one of the first residential areas of collective housing built in Bacău between 1960 and 1970. These diverse functional areas in proximity explain the important daily flows of visitors, especially on weekends, the park being one of the residents’ favorite recreational areas and a significant local tourist attraction. At the same time, given its dimensions and facilities, Cancicov Park is a green area with complex functions that contribute to improving the quality of life of Bacău residents both through its role as a climate moderator—reducing the urban heat island effect and increasing the climate comfort inside it and in proximity [60]—as well as through numerous functional elements that can support various activities aimed at most age groups—playground areas, restaurants, kiosks, areas within the predominantly decorative or administrative sector, and in the 2000s, even a small zoo later transformed into a place for pet owners [59,61].

After 1990, with the opening to capitalist life and the unrestricted right to expression, as in other public spaces, the parks from Romanian towns and cities became the host for works of urban art. The history of graffiti and street art in Romania is new and has evolved as a slow phenomenon in the first years of transition after the Revolution in 1989. Starting with 2007 and Romania’s accession to the European Union, new forms developed: on the one hand, graffiti became more visible in urban territories, and on the other hand, street art emerged relying on the experience of international artists [6].

Despite the uncontrolled development of graffiti, in Bucharest and other important urban areas (Cluj, Timișoara, Iași, Sibiu, Brașov, and Bacău), authorized forms of urban art invaded territories as well in the last 30 years, being encouraged by a series of projects supported by the local authorities or different programs [6]. However, the first post-communist decade cannot, therefore, be considered as a founding stage of graffiti and street art subculture in Romania because of difficulties in obtaining professional materials that influenced the techniques used; only a few names of artists became known in this small community towards the end of the 1990s through tags and stencils, the messages transmitted being mainly political, social, and humorous [62]. After 2000, new styles and forms from the street art branch developed timidly together with graffiti representations. Various messages on different surfaces became more and more visible in many Romanian cities, including messages that are like an alarm signal or have, as their primary purpose, the need to raise awareness of some problems emerging in post-socialist society, e.g., the need to save certain buildings, which are deteriorating in the absence of maintenance work [63]. Hence, urban landscapes were invaded with new graffiti bombs, paint techniques, digital drawings printed on paper, stickers, and other materials, as well as pasted on walls and other surfaces [62].

In the 1990s, graffiti was insignificant in Herăstrău Park, but with the opening of a skatepark area inside in 1995, the inscriptions increased. Starting with 2000s, their growth was due, among other things, to the organization in 2003 by Mountain Dew of an event dedicated to graffiti writers [64], and in 2005, to the internationally well-known graffiti competitions “Write4Gold”, a professional graffiti art contest consisting of four distinct tests: painting, throw-ups, a sketch using special markers and a tagging one [65], events that, together with others organized in Bucharest, contributed to the consolidation of the Romanian graffers’ community.

After 2000, the urban art phenomenon also evolved in the Copou and Cancicov parks.

With a rich cultural and historical tradition, the city of Iași has been perceived for a long time as a bastion of conservatism and traditionalism. Street art (and graffiti in particular) has long been viewed skeptically, considered an act of vandalism and a threat to urban aesthetics. In recent years, however, there has been a change of perception and an opening of the general public to the contemporary art thanks to associations and non-governmental organizations that have become involved in projects that gradually expose the city to new forms of cultural expression, in the recognition of the role of street art in revitalizing urban space. As a general note, street art in Iași has progressed lately from the industrial areas to the marginalized “dormitory” neighborhoods, which became home to colorful elements, large murals, or small artistic interventions. However, Copou Park is known for its predominantly cultural and touristic character, being a central point of attraction in Iași. Therefore, the street art elements are smaller in comparison to other areas of the city.

Cancicov Park is one of the few areas of convergence that attracts visitors from the entire municipality as an area of relaxation and leisure, with a variety of activities and hosting numerous cultural events or civic gatherings. Inherent to such an urban convergence zone, in Cancicov Park, a diversity of artistic works, from graffiti to urban art, may be noticed.

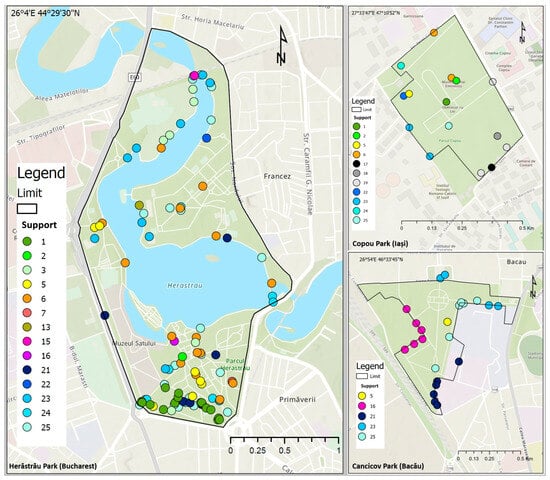

In the studied parks, urban art is dispersed on a large scale (Figure 1), with some density differences discussed in the subsections below.

Figure 1.

The location of the parks selected as case studies in the three cities and the density of urban art (Source: authors).

3.2. Preferred Surfaces for Graffiti and Street Art Works

The preferred surfaces for urban art in the selected parks are generally similar, but some differences are registered within (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Types of surfaces for graffiti and street art works in the three selected cities (1—benches; 2—stairs; 3—poles; 5—waste collection recipients; 6—electricity transformation substations; 7—gas substations; 13—industrial fences; 15—abandoned fences; 16—other fences; 17—passages; 18—bridges; 19—residential walls; 21—restaurants, bars, terraces walls; 22—abandoned walls; 23—other types of walls; 24—panels; 25—others) (Source: authors).

In Herăstrău Park, 99 graffiti and street art spots were inventoried and mapped. The surfaces distribution reflects the park’s equipment in its different sectors and their primary function. Most representations can be found on electricity transformation substations (17.17%) and on benches (15.15%). Then follows the category of other types of walls (other walls than those included in the categories of residential or industrial walls, walls of restaurants, bars, terraces, or abandoned walls) in a percentage of 10%, and billboards with 9.09%. Other walls may be understood as walls in relation to different infrastructure equipment and services, mainly, next to some isolated examples of other types: walls located at one of the entrances to the park, guarding some statues (an important identity component for the place history), a long wall that separates the park from the Cadastral Office, a land consolidation wall of Herăstrău Lake shore, a tin fence, a protection wall with green fabric, a wall of the Apa Nova sanitary protection area (which deals with the management of water supply and sewerage services in Bucharest), and the wall of a sports base. The pillars, the authorized spaces for garbage collection, and the walls of some restaurants, terraces, and bars participate as hosts for artwork in equal proportions, around 6% each. The stairs do not represent an important component of the artworks’ surfaces. On the one hand, there are not very many large stairs in the park, and in general, in other green areas or public spaces in Bucharest, the stairs are not a visible support for artistic interventions (only two small interventions in Herăstrău Park were registered). As for other surfaces, only one representation per category, from the graffiti branch mostly, was mapped on: a gas substation, an industrial fence, an abandoned fence, a wall, and a fence that separates the park of Herăstrău Summer Garden. As for artworks on asphalt, windows, doors, shutters, residential fences, fences of some restaurants, terraces and bars, passages, bridges, residential and industrial walls, no graffiti or street art was found. However, other surfaces which were not included in the worksheet were mapped and collected in the other surfaces category: territorial interactive citizen information system; former underground public toilets; former ticket office of a closed playground/adventure park (Aventura Park Herăstrău); tree; playground equipment; sculpture (Grandma’s and Grandpa’s Girl, a sculpture from 2013); skate area and terrace; poster; cabin installed in a mini-golf route; water pumping station; plinths of missing statue and bust; pontoon wall; dogs’ waste bags dispersers.

The reality in the field shows that almost all urban furniture components and infrastructure related to electricity, water, or gas supply are invaded by graffiti representations. At the same time, there are differences in graffiti and street art works imposed by the roles of the different park parts. There are obvious differences in the southern part of the park, the densest urban art area (Figure 1):

- (a)

- In the south-western part, with the entrance from the Arc de Triomphe and in the Michael Jackson Alley area and surroundings, the share of graffiti and, very sporadically, street art is impressive, the explanations being related to different aspects: the majority of the playgrounds are settled in this perimeter and, consequently, an important attendance of these places by the young population is registered, both children and adolescents; the lack of maintenance of many of the playgrounds in recent years encourages their (over) writing.

- (b)

- In the south-eastern half, with the entrance from Aviatorilor Blvd., is the older area of the park defined by a series of statues, listed as historical monuments: “Sleeping Nymph” (from 1906), “Prometheus” (date unknown) and “Caryatids Alley”, a statuary group placed on one side and the other of the entrance alley from Aviatorilor Blvd., from 1939 and representing peasants from the Muscel and Mehedinți regions with jugs united by an architrave. Demolished in the communist times, Caryatids Alley was reconstituted in 2006 and replaced in the area, given its importance for Bucharest’s history and identity. The “Modura” statue at the end of the caryatids represents a woman who, legend says, offered water to King Carol II when he returned to Romanian soil. The king also issued a coin depicting Modura [66]. Playgrounds are also visible in the landscape, but they are larger and more equipped, generally separated from the main alleys, and frequented more by preschool or primary school children from the nearby area. These public free-access playgrounds coexist with complementary activities from private investments, which increase the degree of surveillance of the entire area, reflected, in the end, by less graffiti. Due to the importance that this park has in Bucharest residents’ lives, different events, fairs or festivals are organized in this part of the park [67], defined by small terraces and food and toys boutiques and an important restaurant, “Pescăruș”/ “Gull”, which opened there in 1938.

Although there are differences between the two angles of the southern part of Herăstrău Park, in the middle area, there is a transition area between the one intended for teenagers and children (including a functional skate park but also abandoned infrastructures) and the area intended for the promenade and well-defined by beautiful historical monuments. In this transition area, the visitors may admire a series of busts of famous Romanian and foreign personalities from different sciences, next to several Romanian folklore monuments representing characters from well-known national stories and legends. It is like a “culture lesson” for visitors, but in many cases, overshadowed or hidden by inscriptions and street art works.

- (c)

- In the park’s northern half, relaxation and leisure activities predominate. In this area, there are structures of this type since the interwar period, listed as protected buildings due to their identity value: “Diplomats Club”, an urban refuge with restaurant and various possibilities to practice sports such as golf, tennis, football, and swimming, founded in 1922 as “Băneasa Country Club Sports Union”, elitist and intended for the personalities of those times. Nearby, there was Băneasa Hippodrome, inaugurated in 1909 and demolished once the communists came to power to make space for the future “Casa Scânteii” (“House of the Spark”), erected under the Soviet influence and where state media publications were printed [68]. “Yacht Club”, inaugurated in 1937 and listed as a historical monument, was the first nautical club in a series of other clubs developed in interwar times and during the communist period, but left abandoned after 1990 [69].

Near its northern limit, there is a denser area of graffiti works, near the railway area, with tags and bombing styles, some more elaborated in recent years, on various infrastructures belonging to the sanitary protection area, situated near the lake. Several works may also be noticed in the crossing area under Băneasa Bridge, but these were not taken into account because they are part of the road infrastructure in a transit area with pedestrian crossings.

In Copou Park, 11 types of surfaces were inventoried on which street art elements can be found, most on the perimeter fence, including on the walls of the buildings that border the park. These surfaces have not yet entered the ongoing rehabilitation process, so the inscriptions will likely disappear shortly, once the park renovation is completed. On the eastern side of the park, towards Copou Alley, old artistic manifestations can be found on the walls of the buildings that border the park. The buildings were erected in the 19th century in neoclassical style, bombed in 1944, and rehabilitated after the war. Nowadays, the eastern perimeter area is no longer of interest to street artists; the walls are also very dilapidated, but it remains a symbol of the first street art attempts in the city. On the park’s south and west sides, the surfaces are more varied, from the concrete wall separating Copou Park from the Roman Catholic Theological Institute to the tin garages belonging to neighboring residential buildings, waste collection recipients, electricity transformation substations, and children’s playgrounds. The newest elements can be found in the central part of the park, on the museum’s walls, but also in the wooden gazebo in the area, or on the stone bridge crossing a small lake.

In Cancicov Park, most of the artistic or pseudo-artistic manifestations can be found on the perimeter fence or the walls of the buildings located at the border of the park, and in more blurred forms on kiosks for seasonal commercial activities, gazebos for social gatherings, statues, or even on decorative works of urban art (the set of carved wooden columns “Genesis” from 1974, damaged over time). The artworks are very visible on the concrete fence that delimits, to the west, the park of the County Library and the Bacău Museum of Natural Sciences. Around 26% of works are encountered on the walls of some restaurants and other public catering units. In similar proportions, works on other types of fences and other types of surfaces may be noticed in the park.

3.3. Location Preferences for Graffiti and Street Art Works

Regarding the artworks’ location, in Herăstrău Park, these are principally located in the alley areas (almost 75.76%), on different infrastructure components: benches (20%), electrical posts (18.66%), billboards (12%), and authorized spaces for garbage collection (6.66%). This category is followed by children’s playgrounds (13.33%).

The fact that they are located in children’s playgrounds and not at all in sports spaces intended for adults or places of relaxation for the elderly demonstrates that urban art is linked to the adrenaline of the young generation, eager to express themselves and gain notoriety. In sports fields, for example (tennis, nautical activities, etc.), the fact that it is about private investments and, therefore, more controlled areas, demonstrates the lack of graffiti inscriptions. There are also situations in which works are visible in other spaces, especially other components of the public spaces: e.g., two former public toilets, a former bust plinth, etc.

In Copou Park, the urban art elements are predominantly located on the walls of buildings, stone walls, garages, electrical posts, billboards, and playgrounds for children. The park has no sports fields, the benches have been recently changed, and the rehabilitated public restroom is guarded, so the available spaces are relatively reduced.

As for location preferences in Cancicov Park, 60% of the works are encountered in alleys accessible to visitors, while the rest are situated in other types of areas, such as kiosks, former public toilets, spaces for garbage collection, and especially perimeter walls (also in areas without alleys).

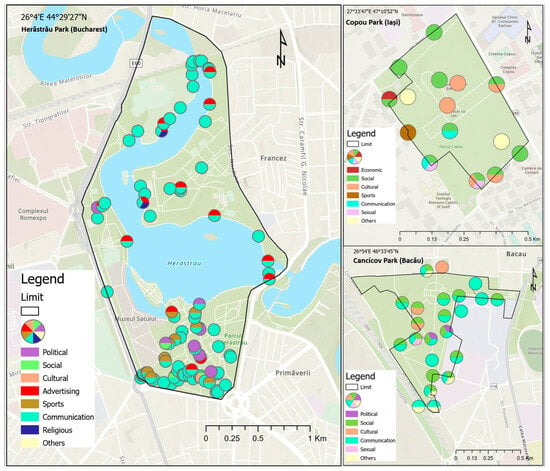

3.4. Messages of Graffiti and Street Art Works

No matter how we call or set them, graffiti or street art, all representations transmit various messages, framed in social, political, and cultural norms, etc., and are situated in different parts of the public spaces. There are similarities and differences in the messages’ typology at the level of the three parks analyzed (Figure 3 and Table 1). In Herăstrău Park, what drives the writers to convey messages is sports meanings occupying the first place, with tags oriented towards supporting sport teams (17.17%). The most frequently encountered message in relation to sports is “Original 1923 Rapid”, referring to an important football team from Bucharest and its year of establishment, with different types of writing as well: “Rapid 1923” or “Original 1923” (eight spots). There are messages which refer to other football teams from Bucharest as tags (“Ultras Giulești” and “Sud Steaua”) or from abroad as stickers (“Nissa e Basta”).

Figure 3.

Types of messages embedded in graffiti and street art works (Source: authors).

Table 1.

The share of message categories of urban artworks in the three selected parks (%).

The messages transmitted are part of the advertising category as well (16.16%), which proves that urban art can be a tool for promoting both important or smaller entrepreneurs (a bank name as sponsor on an artwork in the skate park area; dog training; dog walking; hip-hop singers’ concert promotion; charity activities; Romania Street Art program promotion, etc.). The majority are stickers and use QR codes.

Political messages are less visible (12.12%). There are very few stickers and one tag related to the political movement ANTIFA, and some stickers with “Romania/Bucharest against ANTIFA.” Political graffiti includes as well messages of support for Ukraine, in relation to the COVID lockdown, and a sticker with “Eat the Rich” written on a mask.

Just four messages were identified with a religious reference (e.g., two stickers with the QR Code “Camino de Santiago”) and only one with a cultural meaning.

However, since the abundance of graffiti representation is very high in Herăstrău Park, it is inevitably about overlapped inscriptions from different periods, most categorized as incomprehensible communication, as it is impossible to discern their whole meaning. Incomprehensible communication may sometimes occur for single tag-type inscriptions as well. However, in most cases, it is about messages overlaid with inscriptions, and even if, initially, the meaning of the first tag could be discerned, the passage of time and the messages written over time on the same surface make them partially or entirely unintelligible. Thus, 88 representations were identified in Herăstrău Park, the messages being primarily categorized just as incomprehensible communication (53.53%) or in association with other types of messages: sports (15.15%), religious (9.09%), or religious and advertising (3.03%).

Very present in urban environments, graffiti representations with sexual connotations or offensive messages are also visible in Herăstrău Park. However, only five spots were identified, partially or entirely covered by various other works (mainly from the category of tags) and, therefore, of multiple messages difficult to decipher. This issue ultimately led to their inclusion in the category of incomprehensible communication.

In Copou Park from Iași, social (61.54%) and cultural (30.77%) messages predominate. Occasionally, messages that can be included in the economic category appear. On the park’s southern side, there are elements of old, faded graffiti, blurred by vegetation, where messages with vulgar tendencies can still be deciphered.

The most valuable, however, are those with cultural messages that can be preserved even after the park’s rehabilitation works are completed. Thus, the most important form of urban art is the mural painted in 2020 behind the House of Culture “Mihai Ursachi”, as part of the exhibition “Textures of identity”, on the occasion of the 5th edition of the White Night of Galleries. It is a large-scale work, accessible to the public except for the upper part. Also known as “Ursachi’s Dream”, the composition combines elements from the work of the poet Mihai Ursachi, such as the irony of inconsistency and a plea in favor of nonsense.

In Cancicov Park from Bacău, in most cases, we witness a combination of messages from several categories, added successively sometimes by different authors using tagging (tags of some ad hoc authors) and bombing styles. The majority transmit social messages (in 69.57% of the works, some even of social revolt) or individual incomprehensible communication (82.61%), sometimes with sexual overtones, while approximately 13.04% have a proper cultural or artistic message.

The work from 2020 on the facade of the Summer Theater, entitled “Art is for nothing,” is remarkable. Since 2017, this 120 square meter mural painting has been redesigned at specific intervals in the framework of the Street Delivery project. The themes represented in murals are the artists’ visions regarding the objectives of these events, which often focus on cities’ challenges. The last one is from 2020, within the ReSolutions—Street Delivery Bacău event. The figures of five important Romanian actors are painted using paint that can filter and purify the air. It conveys a pro-culture manifesto message, a field strongly affected by the pandemic, transmitted as an alarm signal that the culture needs support from the authorities and consumers. In this mural, outstanding personalities of the Romanian theatre are painted (Amza Pelea, Leopoldina Bălănuță, Radu Beligan, Stela Popescu, and Toma Caragiu). It should be stated that Bacău became nationally recognized for the use of paint that purifies the air, the first mural of this kind being inaugurated in Bacău in 2019, a work that, every 12 h, can remove the pollutants emitted by approximately 50 Euro 6 gasoline cars. The paint reduces air conditioners’ costs, energy consumption, and greenhouse gas emissions, which cause climate change [70].

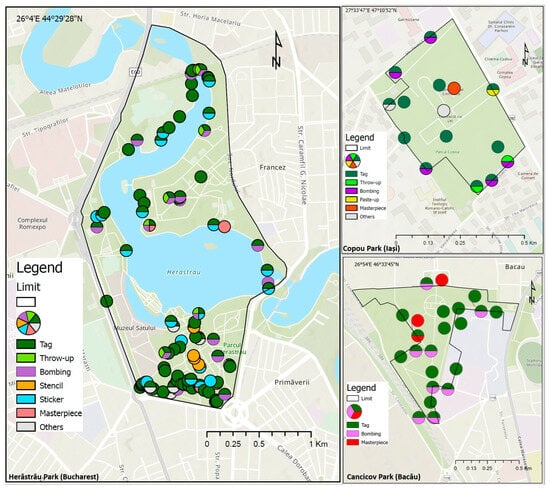

3.5. Styles of Graffiti and Street Art Works

Although in the typology of urban art styles listed in the worksheet ten categories were included, the small history and, hence, the lack of maturity of the urban art phenomenon at the level of the urban environment in Romania contributed, in the end, to the identification of fewer types and sometimes in association (Table 2 and Figure 4). In Herăstrău Park, only six types of urban art were identified: tags, throw-ups, bombing, stencils, stickers, and masterpiece murals. By far, the tags category is the most present style with 85 tags, followed by stickers (24) and bombing works (23) (Figure 5). In the case of stickers, being easy to apply, the authors are Romanians and foreigners in transit in Bucharest.

Table 2.

The share of urban art styles in the three selected parks (%).

Figure 4.

Styles of graffiti and street art works (Source: authors).

Figure 5.

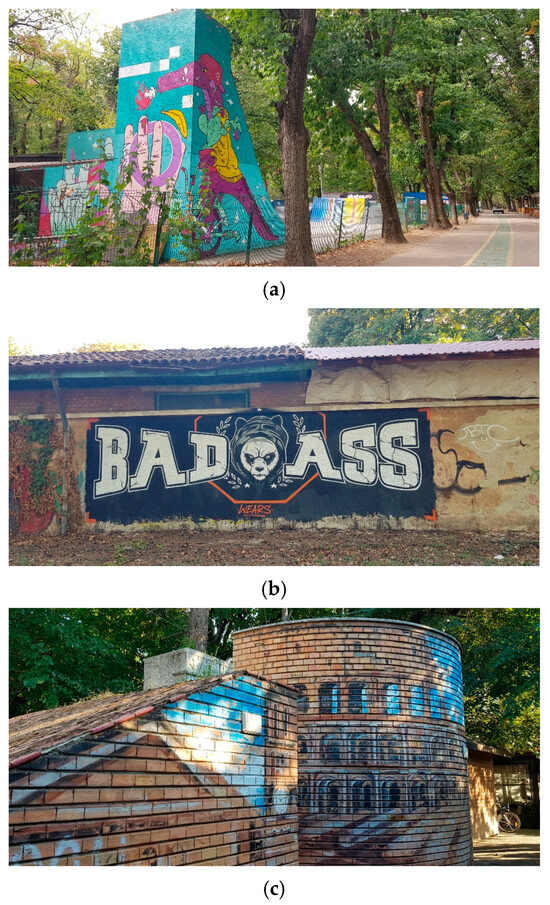

Tags, throw-ups, and bombing styles in Herăstrău Park (Source: authors, 2024).

Only three murals were mapped, which explains the statement above regarding a stage of transition towards street art in which graffiti is still predominant (Figure 6). An important mural is in the skate area and the Baraka terrace, which has been operating there since 1998, with colorful performances dedicated to children passionate about movement and skateboarding (Figure 6a). Also, on the wall of a former Kayak–Canoe sports base, an advertisement for a clothing style (BADASS Wears) (Figure 6b) may be observed. However, an authentic work is in the area of a restaurant with Italian cuisine, “Il Calcio”, with representations of the architecture of ancient Rome, including the Colosseum (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

Murals in Herăstrău Park: (a) skatepark area; (b) wall of a former Kayak–Canoe sports base; (c) restaurant area. (Source: authors, 2024).

In Copou Park, many works are from tags and bombing styles (Figure 7). Therefore, their aesthetic value is indifferent. Most are mono- or bicolor and most likely belong to the early period of urban art in Iași. The only exception is the mural “Ursachi’s Dream” (Figure 8), an authentic, impressive work, in which the colors yellow, blue, and orange predominate, made with quality materials. In order to emphasize the cultural character of the park, during the rehabilitation works of the urban furniture from 2023, marble book-type benches printed with the most famous poems of the national poet Mihai Eminescu or with fragments from the works of famous prose writers as well as benches covered with reproductions of Romanian painters’ works were installed. These benches have a unique character at the national level and, although they are not included in the urban art category, they are very appreciated by the park’s visitors.

Figure 7.

Tags and bombing styles in Copou Park (Source: authors, 2024).

Figure 8.

Mural “Ursachi’s Dream” in Copou Park (Source: authors, 2024).

In Cancicov Park, most works are tags and belong to the period 2015–2018. While the bombing and mural types of representations are fewer in number, their visual impact is obviously stronger (Figure 9 and Figure 10). The fence that delimits, to the west, the park of the County Library and Bacău Museum of Natural Sciences is one of the urban art surfaces invaded mainly by tag messages for a very long time, but today, more and more with small murals (Figure 10b). Another area with a relative concentration of works, mainly graffiti, is the area at the park’s southern exit on the wall of some buildings adjacent to the analyzed area. It concerns overlapped interventions, mainly tags and fewer from the bombing style (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Tags and bombing styles in Cancicov Park (Source: authors, 2024).

Figure 10.

Murals in Cancicov Park: (a) Summer Theater “Radu Beligan”, (b) the fence of the County Library and the Museum of Biological Sciences (Source: authors, 2024).

Located at the northern limit of the park, the facade of the Summer Theater “Radu Beligan” represents a synthesis and a “peak” of Bacău street art (Figure 10a). It is a different approach to classical mural style because this mural’s contribution is not only aesthetic, but also helps the environment, thanks to the paint used. The air purifying paint filters the air like a forest of trees on 120 square meters (the surface occupied by the mural) [71].

4. Discussion

In recent years, urban art has become a tool used by the population, street artists, and authorities, sometimes in a collaborative process [2], considering that artistic interventions in urban street environments improve well-being to the same extent as other urban projects. In the present article, we tried to estimate the role of urban art in the organization of the three urban parks by analyzing different characteristics of this phenomenon, to see if they bring advantages or disadvantages. Graffiti and street art works were studied in relation to the type of hosting surfaces and interventions, next to the context evolution, conducted to the following statements: on the one hand, the “individual voice” of the population revealed in the local landscapes is reflecting both negative feelings of dissatisfaction “written” as a response to different social, economic or political realities, and positive ones, as publicity of small businesses or just positive reactions linked to green and sport benefits, etc.; on the other hand, the “collective voice” depicts if there is a valuable cooperation between the actors who can or may be involved in the integration of urban art at the level of green areas and its impact on public sentiment and role in public discourse has been actively studied lately [4].

Graffiti allows all segments of society to express their thoughts and feelings [4,72], and the engagement of artists in social problems has become visible over the years in almost all European cities as “a public debate, a broader dialogue not limited to local discourse” [73].

As the main research question was to evaluate the urban art rapport with the parks’ organization, this study revealed the following:

- (1)

- Even if, in the field, an important share of works closer to graffiti styles than to street art may be noticed in all three parks, a transition towards street art may be perceived as isolated.

- (2)

- Being an ephemeral art, it is tough to establish the phenomenon’s evolution thread. This issue is doubled by the capacity of intervention in the organization of parks which in many cases is translated into projects carried out at different times, especially in the case of those occupying extensive areas: being the largest park in Romania, Herăstrău Park requires maintenance and modernization works in different stages, which gives rise to permanent discrepancies in terms of urban art visibility, unlike the other two case studies which after modernization works, automatically lose on entire park surface the previous layers of graffiti and maybe even some street art. The entire area of Cancicov Park is undergoing a radical redevelopment process this year that will reconfigure its whole organization, structurally and functionally modifying many of the defining elements of this essential green area of Bacău. Consequently, many of the urban artworks will be removed. The same situation is occurring in Copou Park, where in the last five years, several plans have been presented for the park rehabilitation to satisfy the need for agreement and recreation of a growing population, the reduction of pollution levels, and a better urban image, with the first works starting in 2023.

- (3)

- Some contrasts may be explained by considering the extent of the parks, next to the visitor locations and the appreciation of different parts. For example, Herăstrău is the largest park in Europe within a city, and the challenges arising from its management are important. It is an easily accessible park, and the areas of origin of the visitors’ flow are directly correlated with the public transport lines [74]. The fact that it is located in the northern area of the city, a more select area and less impacted by the functional and architectural mutilations of the communist times, explains the touristic interest and, thus, a larger attraction for investors from public catering. Occupying an important area, the park has always represented an oasis of tranquility for the elite and the common population, reflected nowadays, among others, in graffiti and street art landscapes. What is certain is that in all three parks, inside the less managed perimeters, not at all supervised and, even more, abandoned, graffiti rises naturally, relying on similar principles as in other public spaces and impacting the parks’ organization and image. On the contrary, the inscriptions are fewer in open and frequented areas and with economic activities, where the possibility of intervening with consequences is greater. Lastly, precedent graffiti encourages future interventions, leading to a large-scale phenomenon in these spaces.

- (4)

- Urban art contribution to the parks’ equipment may be noticed in some of our case study parks. Herăstrău has two skate areas: one in the south part, a skatepark opened in 1995 as a private investment with free entrance, supported by different sponsors which make possible the maintenance of this area, with a terrasse nearby opened in 1999 and a beautiful mural, many festivals or events being organized on different occasions; the other skate area, “At Ramps”, situated in the north part of the park, was opened in 2022 by the City Hall, a winning participatory budgeting project from 2021 and integrating colorful graffiti works on the skate infrastructure.

- (5)

- The murals generally have a commercial purpose, increasing the visibility and notoriety of local businesses, e.g., “Skatepark & Baraka” terrasse and restaurant “Il calcio” in Herăstrău Park, but also a cultural purpose, e.g., the mural from the Summer Theater “Radu Beligan” in the Cancicov Park area and the mural “Ursachi’s Dream” from Copou Park, behind the Mihai Ursachi Cultural Center.

- (6)

- No temporary installations were inventoried in the analyzed parks.

- (7)

- Urban art’s contribution is partial because, despite the positive examples presented in this study, the infusion of graffiti interventions in different parts of the parks remains significant.

- (8)

- Street art projects involve creative processes initiated mainly by the artists and the entities who contract them (local authorities and private companies), and much less coming from residents, which does not lead to evident support for increasing civic engagement.

- (9)

- There are also some differences between the three parks: the density of graffiti interventions, but also of street art, is much higher in Herăstrău Park, the works being distributed in all the park’s perimeters, compared to other two parks analyzed; differences are visible as well in terms of urban art manifestation: for example, stickers are absent from Cancicov and Copou parks, which shows that the three cities are in different stages of urban art phenomenon evolution; in general, there is no evident variety of graffiti representations in Cancicov and Copou parks compared to Herăstrău park; the types of messages transmitted by the murals from Copou and Cancicov parks come from culture and are related to local or national identity, in comparison to Herăstrău Park from Bucharest and its murals meant to transmit advertising messages, acting more like a tool for coloring places and attracting people of different generations for activities in restoration and sports, mainly; a difference can also be noticed in the case of the murals’ financial support: the murals are the result of public initiatives and financed by public institutions in Cancicov and Copou parks, unlike those in Herăstrău Park, which are the result of both public and private investments.

To understand the evolution of the urban art phenomenon in the parks studied, it is essential to relate the results obtained to heritage management, urban art legislation, culture, identity, and placemaking in the given local contexts. In all three parks, graffiti inscriptions mostly remain long after they are written on heritage-listed monuments or those of heritage value, which shows deficiencies in local heritage management. For example, Herăstrău Park is entirely listed on the list of Bucharest’s historical monuments, but the number of graffiti works is very high.

In some parts of the studied parks, graffiti develops to the detriment of street art and interferes with the local built heritage values. The results obtained in this study capture some administrative challenges in relation to urban art in green areas and, in the end, offer information about how the city acts in response to the amplification of this phenomenon in public spaces. The graffiti phenomenon’s extension is sometimes doubled by incomprehensible overlaps of representations, which affect the image of some parks’ perimeters.

This study does not directly analyze the impact of urban art on heritage management, identity, or placemaking, which could be correctly assessed only by applying qualitative methods, but rather highlights the situations in which urban art, namely, graffiti-type representations, sometimes interfere with historical monuments in the studied parks. These interventions in the public space do not use messages that transmit local or national identity elements, and in the majority, they are indecipherable tags. Additional qualitative investigations are needed to make correct assessments of their way of perception, but they are not the subject of the present article. However, some general preliminary ideas may be a starting point in future research: the interventions are more encountered in perimeters with greater frequency (e.g., at the entrance to the parks, etc.); they bring challenges in the green areas’ perception; the parks are often associated with less supervised and preserved areas.

Until a few years ago, one could speak at national level of the lack of clear regulations in relation to urban art, sometimes creating confusion at the level of institutions in terms of urban art authorization: e.g., in 2017, Bacău city hall was fined for a mural made during Street Delivery festival on the facade of the Summer Theatre, Cancicov Park, due to the lack of some institutional approvals [75].

In 2022, the Graffiti Law came into effect, with author fines ten times higher than those applied until then [76]. This dedicated law to the urban art phenomenon clarifies by modifying and supplementing the 1991 law on the sanctioning of acts of violation of social norms, order, and public peace [77] and abrogating the law from 2003 regarding measures to ensure the aesthetic appearance of the Capital and other localities [78].

The setting up of areas and surfaces where the authors of urban art could intervene freely, without legal constraints, or even the approval of some perimeters dedicated to these actions inside the parks could create a bridge between the authors and this phenomenon by entering these works into legality and, thus, contributing to an easier acceptance by the general public. Apart from the legislation in force related to the institutionalization of the phenomenon, both at national and local levels, it also depends on cities’ perspectives regarding integrating urban art in the local landscape. There are visible differences between bigger and smaller cities, except for cases in which the phenomenon is acknowledged thanks to some projects or events. Moreover, a very eloquent example is Bacău city, where Cancicov Park is located. From a legal point of view, the local authorities in Bacău, on the one hand, apply fines and monitor compliance with the law regarding unauthorized street art works, but on the other hand, they promote a favorable attitude towards authorized urban art projects, many of the collective residential buildings and some facades of educational, administrative or cultural institutions supporting large projects such as ZidArt, but also smaller initiatives such as those promoted by the students of Art High School in Bacău.

The works identified in some spots inside the three parks convey cultural messages, knowing that “street art works can convey cultural narratives and historical events that shape the collective memory of a society” [4,79] responding in a certain degree to the sustainable cities’ principles. The artworks may draw public attention to an issue: e.g., “Art is for nothing.” The mural from Cancicov Park transmits messages of support for the culture, highlighting the challenges faced by the theater in pandemic times.

Graffiti murals have become part of residents’ and visitors’ perception of their city [2], meaning that they participate from an aesthetic point of view and shape its identity. It was demonstrated that street art can function as a placemaking tool [80], so citizens may join the new areas defined by urban art as both users and actors involved in those creative processes. In the studied parks, the relationship between urban art and local identity is less perceptible, except in a few areas, being about spatial meanings, in general concerning urban sports (skate and roller areas in Herăstrău Park) or cultural interventions (The Summer Theater in Cancicov Park).

Whether it is about simple forms of graffiti or more elaborate art, their contextual arrival is critical. Apart from individual or small group initiatives, the crew works have become more and more palpable in public spaces of Romanian cities as a result of collaborations within different occasions and events, among which are Street Delivery Festival in the case of Herăstrău and Cancicov parks, ZidArt in Cancicov Park, and Write4Gold and George Urban Movement in Herăstrău Park, to which are added other events that have become more numerous during the pandemic times and which are already becoming traditional and integrating, among others, the urban art component.

Urban art in Romanian cities has a young status, and green areas are not the “most wanted canvas” as compared to other public spaces in the cities, more frequented and, thus, more visible. Therefore, it was impossible to follow an exhaustive analysis on different categories of urban art in relation to the dynamics of urban development or the general stakeholders’ narratives, except for the murals that convey a cultural message in the parks of Bacău and Iași: on the one hand, the mural from Cancicov Park is a tribute to Romanian theater artists born in the area, collaborating with Bacău Theater or recognized as great artists at the national level and, on the other hand, in Copou park, it is about a tribute mural to a Romanian poet and translator born in Iași County.

The results obtained in this research also offer a perspective on urban art as a tool for Romanian cities’ sustainability. Therefore, they validate that the authorized urban art in green areas can support the fight against pollution through sustainable practices such as the use of paint that purifies the air, and by addressing cultural messages in different artworks, it may contribute to the conservation and passing on of the local identity and, in the end, to stronger ties in communities.

The scientific results may be considered as applicable for future spatial and functional organization parks’ visions, especially management directions that either will include just different projects related to graffiti interventions (e.g., permanent legal graffiti walls, approved temporary interventions, etc.) or, moreover, will consider to develop more authorized street art (e.g., murals or different mixed styles) as a tool to increase the parks’ visibility at municipal level.

Regardless of the stage that graffiti and street art culture reach in cities, it ultimately depends on the local authorities’ degree of integration of urban art, either as a powerful tool for urban development or simply as a way of expression and, therefore, acceptance.

5. Conclusions

The current study demonstrates that graffiti and street art are visible in the analyzed urban parks in Romanian cities and impact their organization and functionality. These urban parks are characterized by different temporalities reflected in the number of artwork layers and their integration in the local landscapes. The more artistic meanings of works in recent years bring a step forward to street art development and its contribution to the parks’ aesthetic and functionality. Therefore, by putting the spatial evolution of the phenomenon in relation to social, economic, legislative, and events’ context, the present study may be considered original for Romanian cities’ urban art analysis as it reveals it not to be not just an inventory of different works, but offers to the large public in a broader context the urban art image as it is “voiced” by some “territorial traces”, in this case, graffiti and street art works.

This study’s limitations were the lack of a Google Street View images dataset covering the entire surface of the parks, especially at the level of narrow alleys, and the small number of images at different time intervals, which together would have provided significant information for an accurate temporal comparative analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-L.C.; methodology, A.-L.C. and A.B.; software, A.-L.C. and A.B.; validation, A.-L.C., A.B., E.B. and M.I.; formal analysis, A.-L.C. and A.B.; investigation, A.-L.C., A.B., E.B. and M.I.; resources, A.-L.C., A.B., E.B. and M.I.; data curation, A.-L.C., A.B., E.B. and M.I.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-L.C.; writing—review and editing, A.-L.C. (supervision), A.B., E.B. and M.I.; visualization, A.-L.C., A.B., E.B. and M.I.; supervision, A.-L.C.; project administration, A.-L.C., A.B., E.B. and M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

A.B.’s work has been conducted with the support received through the project “City Focus: Future Organisation of Changes in Urbanisation and Sustainability” (CF 23/27.07.2023), financed by the Romanian Ministry of Investment through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR-III-C9-2023—I8_round2). A.-L.C. and E.B.’s work has been conducted as part of the Graffiti and Street Art Interdisciplinary Research Working Group (GRAFSTART).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vitiello, M. Street Art and Its Conservation Problems. In Contemporary Heritage Lexicon; Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering; Bartolomei, C., Ippolito, A., Vizioli, S.H.T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 175–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yibin, H. Conflict and Fusion Between Graffiti Mural and Public Space. HSSR—Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2024, 7, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.; Jürgens, A.-S.; BOHIE; Rod, L. Street art as a vehicle for environmental science communication. JCOM 2023, 22, A01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalashnyk, M. From the street to the gallery: Evolution and influence of street art on contemporary art culture. Interdiscip. Cult. Humanit. Rev. 2024, 3, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercleux, A.-L. Graffiti and Street Art between Ephemerality and Making Visible the Culture and Heritage in Cities: Insight at International Level and in Bucharest. Societies 2022, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercleux, A.-L. Street Art Participation in Increasing Investments in the City Center of Bucharest, a Paradox or Not? Sustainability 2021, 13, 13697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, C. Graffiti or Street Art? Negotiating the Moral Geographies of the Creative City. J. Urban Aff. 2012, 34, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Brita, T. Resilience and adaptability through institutionalization in graffiti art: A formal aesthetic shift. Graffiti Str. Art. Urban Creat. Sci. J. Chang. Times Resil. 2018, 4, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralińska-Toborek, A. Street Art and Space. In Aesthetic Energy of the City. Experiencing Urban Art and Space; Gralińska-Toborek, A., Kazimierska-Jerzyk, W., Eds.; Łódź University Press: Łódź, Poland, 2016; pp. 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M. The Writing on Our Walls: Finding Solutions through Distinguishing Graffiti Art from Graffiti Vandalism. J. Law Reform 1993, 26, 633–707. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, S. Keeping it real? Subcultural graffiti, street art, heritage, and authenticity. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, C.; Colombini, M.P.; Lluveras-Tenorio, A.; La Nasa, J.; Striova, J.; Salvadori, B. Graphic vandalism: Multi-analytical evaluation of laser and chemical methods for the removal of spray paints. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 44, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felisbret, E. Graffiti New York, 1st ed.; Harry, N., Ed.; Abrams: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0810951464. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, J.F. Trains, railroad workers and illegal riders: The subcultural world of hobo graffiti. In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art; Ross, J.I., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 27–35. ISBN 978-1-315-76166-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.C. Writing on the Wall: Street Art in Graffiti-free Singapore: Writing on the Wall: Street Art in Graffiti-free Singapore. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2018, 43, 1046–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, B. Sari, Femininity, and Wall Art: A Semiotic Study of GuessWho’s Street Art in Bengaluru. Tripodos 2021, 50, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abram, S.; Ušić, E. Understanding Walls on the Periphery: Street Art and Graffiti between Commodification, Dissent and Oblivion. Editorial note. SAUC—Str. Art Urban Creat. 2024, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitridge, P.; Williamson, J. Communities of Discourse: Contemporary Graffiti at an Abandoned Cold War Radar Station in Newfoundland; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Karas, S. Graffiti on Bridges-Aesthetical Assessment. MOJ Civ. Eng. 2017, 3, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roviello, V.; Gilhen-Baker, M.; Roviello, G. Graffiti Paint on Urban Trees: A Review of Removal Procedures and Ecological and Human Health Considerations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondo, T.; Zibabgwe, S. GIS solutions and land management in urban Ethiopia. Perspectives on capacity, utilization and transformative possibilities. Manag. Res. Pract. 2010, 2, 200–216. [Google Scholar]

- Quintas, A.V.; Curado, M.J. The contribution of urban green areas to the quality of life. In Proceedings of the City Futures in a Globalising World, An International Conference on Globalism and Urban Change, Madrid, Spain, 4–6 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Colesca, S.E.; Alpopi, C. The Quality of Bucharest’s Green Spaces. Theor. Empir. Res. Urban Manag. 2011, 6, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.K.; Chang, S.; Michalkó, G. Smart Living and Quality of Life: Domains and Indicators. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2024, 16, 181–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokras-Grabowska, J. Recreational Space—Forms, Transformations and Innovative Trends in Development. Geogr. Tour. 2019, 7, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogan, E.; Simon, T.; Cândea, M. Așezările Umane și Organizarea Spațiului Geografic; Universitară București: Bucharest, Romania, 2023; ISBN 978-606-28-1595-0. [Google Scholar]

- Flanders Cushing, D.; Pennings, M. Potential affordances of public art in public parks: Central Park and the High Line. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.—Urban Des. Plan. 2017, 170, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandeva, V.; Despot, K. Art principles in park art as a factor for street landscaping in cites. In Proceedings of the IXth International Scientific Conference on Architecture and Civil Engineering ArCivE 2019, Varna, Bulgaria, 31 May–2 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Street Art City. Fief de L’art Urbain. Available online: https://www.allier-auvergne-tourisme.com/culture-patrimoine/musees-spectacles/street-art-city-8828-1.html (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- LE SPOT: Nature, Art et Sport//Un Site Unique en Ile-de-France. 2024. Available online: https://www.joinville-le-pont.fr/actualite/foret-urbaine-street-art-et-terrains-de-sport-les-nouveaux-delaisses-de-lautoroute-a4/ (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Street Art Murals for Urban Renewal. Building Community Engagement, Fostering Urban Regeneration Through Mural Street Art. 2017. Available online: https://urbact.eu/good-practices/street-art-murals-urban-renewal (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Green Street Art: Art, Nature et Ville. AURA. 2018. Available online: https://www.aura-urbaine.com/green-street-art-art-nature-et-ville/ (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Land Art, Trash Art, Écovention, Artivisme: Qu’est-Ce Que L’art Écologique? 2024. Available online: https://www.hellocarbo.com/blog/media/land-art-trash-art-ecovention-artivisme-art-ecologique/ (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Tutoriel: Le Street Art Écologique, Graffiti en Mousse. 2017. Available online: https://www.slave2point0.com/2017/05/08/tutoriel-le-street-art-ecologique-graffiti-en-mousse/ (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Mestaoui, L. Green Art. La Nature, Milieu et Matière de Création; Collection Hors-Série Alternatives; Alternatives Gallimard: Paris, France, 2018; ISBN 978-2072757815. [Google Scholar]

- Pouyet, M. Street Art Vegetal. Carnet de Poesie Naturelle en Milieu Urbain; Plume de Carotte: Toulouse, France, 2018; ISBN 978-2-36672-163-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mikuni, J.; Dehove, M.; Dörrzapf, L.; Moser, M.; Resch, B.; Böhm, P.; Prager, K.; Podolin, N.; Oberzaucher, E.; Leder, H. Art in the City Reduces the Feeling of Anxiety, Stress, and Negative Mood: A field study examining the impact of artistic intervention in urban public space on well-being. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2024, 7, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, F.; Merza, A. A Study of the Semiotic Understanding of Land Art. Asian Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudo-Martínez, M.J. Land Art, Ruralismo Y Paisajismo Noruego. In Exigencias de Gobernabilidad, Sostenibilidad Y Perspectiva de Género en la Atención Al Mundo Rural; Dykinson, S.L., Ed.; Colección Conocimiento Contemporáneo: Seville, Spain, 2024; Volume 172, pp. 1097–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Remesar, A. De l’escultura Al Post-Muralisme. Polítiques d’Art Públic En Processos De Regeneració Urbana. W@terfront. Public Art. Urban Design. Civ. Particip. Urban Regen. 2019, 61, 3–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, R. The “Expo” and the Post-“Expo”: The Role of Public Art in Urban Regeneration Processes in the Late 20th Century. Sustainability 2022, 14, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]