1. Introduction

The fashion industry has evolved rapidly in recent decades and is now one of the most influential economic sectors in the world. But this growth comes with both benefits and drawbacks, with the price of economic growth being paid through environmental pollution. Natural resources are being intensively used, carbon emissions are rising year on year, and working conditions in factories are often poor. The fashion industry is ranked third after oil and agriculture as the most polluting industry on earth [

1] (Amatulli et al., 2017). The entire life cycle of a garment in the supply chain (passing through fabric and garment production, distribution, retail, use and disposal) faces several sustainability challenges.

Under these conditions, marketing strategies have become necessary to promote sustainability, aiming to influence consumer behavior and shape the future of the industry, widely discussed in the fashion industry, with significant changes needed in garment production, consumption and recycling.

The concept of sustainability plays a central role in the fashion industry’s transition towards more socially and environmentally responsible practices. The concept of sustainability was defined in 1987 in the Brunt Land report and was subsequently adopted by the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Sustainability means meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. This definition emphasizes the essential balance between economic progress, social responsibility and environmental protection—a triad also relevant for the fashion industry, in the context of growing pressures for transparency, responsible consumption, and eco-innovation.

Implementing sustainability in fashion faces many challenges. One of the potential challenges of sustainable fashion is the higher price compared to fast fashion clothing [

2]. The fashion industry is one of the major industries contributing to environmental degradation due to fast fashion practices and cheaply manufactured clothing [

3]. For example, almost three-quarters of fast fashion clothing ends up in landfills [

4] (Legere and Kang, 2020).

To enhance sustainable consumption patterns, slow fashion and thrift shopping are emerging as alternatives to fast fashion systems [

4]. Fashion is inherently the consumer product category with the highest intensity of change [

5,

6] and the fast fashion trend is spreading rapidly in the fashion industry [

7]. Farrer & Fraser (2011) [

8] argue that the current dominant fashion business necessarily embraces trends, even if they are not desired at first. This phenomenon is prevalent in the fashion industry as a requirement to survive in trend-sensitive fashion markets.

There is an urgent need to protect the environment and ensure a fair future for all participants in the supply chain. Commitment to sustainable practices has the potential to transform the fashion industry into a model of environmental and social responsibility. While the challenges are significant, through innovation, collaboration and education, fashion remains not only a symbol of style, but also of sustainability.

Research gap: Although there is a growing literature on sustainability in the fashion industry, many studies focus predominantly on the technical aspects of sustainable production or on consumer behavior in isolation, without analyzing in depth the integrative role of marketing strategies in promoting sustainability. Moreover, most existing research approaches sustainable marketing from a general perspective, without concretely exploring how fashion brands can use marketing to build credibility, educate the public and generate real competitive advantages. The lack of studies linking the various dimensions of sustainable marketing, such as marketing strategies to educate and sensitize consumers on sustainability issues in the fashion industry, the importance of supply chain transparency, public brand engagement, green innovation or strategic collaborations, creates a relevant research gap. Empirical research using quantitative models (such as PLS-SEM) to test these relationships in the context of sustainable fashion is also limited. Therefore, this paper aims to fill this gap by analyzing, within an integrated framework, how marketing strategies influence the adoption of sustainable practices in the fashion industry and consumers’ perceptions of these practices.

Aim of the research: The paper develops an integrated conceptual framework that analyses the role of sustainable marketing strategies in the fashion industry, addressing eight key dimensions: supply chain transparency, brand reputation, sustainable innovation, building an engaged community, commitment to sustainability, access to new markets, consumer education, and collaboration with external organizations. The study contributes to extending the literature by testing them in a quantitative model using structural equation modeling (SEM-PLS) to validate the relationships between these variables and consumers’ intention to adopt sustainable consumption. Furthermore, the research provides practical recommendations for fashion brands, indicating the most effective marketing strategies to promote sustainability and generate competitive advantage.

Research results: The results obtained by structural equation modeling (SEM) using SmartPLS4 confirm the validity of all the hypotheses formulated. The tested model highlights a number of significant relationships between the dimensions of sustainable marketing and the key variables that contribute to promoting sustainability in the fashion industry. Thus, supply chain transparency was found to have a significant impact on brand reputation and the creation of an engaged community, emphasizing the role of transparency in building trust and stakeholder engagement. Sustainable innovation positively influences both brand reputation and access to new markets, highlighting the potential of innovative marketing to strengthen the strategic positioning of fashion companies.

The brand’s concrete commitment to sustainability also contributes significantly to accessing new markets, and educating and raising consumer awareness positively drives both the creation of an engaged community and collaboration with sustainable organizations and brands. In addition, sustainable collaborations positively influence market expansion, completing an integrated framework in which sustainable marketing strategies generate tangible benefits for fashion brands. In conclusion, the results confirm that sustainable marketing can function as a strategic transformative factor, contributing to both building a solid reputation and expanding growth opportunities in a responsible and future-oriented framework.

The study provides a comprehensive perspective on the interplay between marketing, sustainability, and consumer behavior, identifying the key elements that favor the transition of the fashion industry towards a responsible business model. This paper addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: What is the role of marketing strategies in promoting sustainable consumer behavior in the fashion industry?

RQ2: How can fashion brands utilize sustainability as a competitive advantage through marketing?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of Sustainability in Fashion

Fashion, a global phenomenon, is underpinned by changes in the organization of clothing production around the world as well as the vast economic importance of clothing production in world trade [

9]. The fashion industry is characterized by dynamism and global influence as it is in a period of major transition. The concept of sustainability has gained increased global attention and is now a very important topic under consideration in industries around the world. It is particularly relevant to talk about sustainability when it is implemented in the fashion industry, as it is one of the most polluting industries in the world, with a huge impact on the environment, but also on the social and economic sectors [

4,

10].

Adopting a sustainable model in the fashion industry involves implementing effective strategies that can reduce negative environmental impacts and promote responsible practices at all stages of the supply chain.

Gaps in the literature review: Although the literature highlights a number of sustainable marketing strategies and addresses the negative externalities of fast fashion, there is a lack of integrated empirical models testing how specific marketing variables influence the promotion of sustainability in the fashion industry. The majority of existing studies are either conceptual or focus on isolated aspects such as transparency or consumer education, without examining the interrelated relationships between these factors. In addition, there is limited attention paid to emerging contexts, such as Romania, where sustainable practices are still at an early stage. This study aims to fill these gaps by testing a broad conceptual model that investigates the influence of transparency, innovation, consumer education, brand engagement and stakeholder collaboration on sustainability in the fashion sector. By using structural equation modeling (SEM-PLS), the research provides relevant empirical evidence on the effectiveness of sustainability-oriented marketing strategies, thus contributing to the expansion of knowledge in the field.

2.2. Fast Fashion and Environmental Impact

Marketing starts with the market and the consumer [

11]. In the fashion industry, marketing must not remain merely informative but must become inspirational in order to inspire consumers to make more responsible choices. Another very important aspect to discuss when talking about sustainability in the fashion industry is the concept of fast fashion. Toxic chemicals are often used in the fashion industry, and through the dyeing and treatment of textiles, water is polluted, and hazardous chemicals are often discharged directly into rivers and other water sources, affecting both the environment and the health of local communities. By using cheap synthetics such as polyester, which is highly polluting and very difficult to break down, it indirectly encourages high clothes shopping and much faster disposal.

The fashion industry is currently growing day by day due to the increasing demands of the population, gaining success and popularity, but also generating new social, environmental, and economic problems that need to be solved by global solutions [

12]. This industry is one of the major contributors to social and environmental sustainability issues [

13]. The fashion industry has a major impact on society, especially in developing countries on the labor force. Most of the time, in large factories of fast fashion companies, the working conditions are poor and wages are low, thus labor exploitation becomes a serious problem. The fashion industry generates significant revenues globally, but these are economically unequal.

These effects are exacerbated by the accelerated production model, which encourages overconsumption and rapid replacement of clothing items. For example, Zara launches around 24 collections per year and H&M between 12 and 16, updated weekly [

14]. This high frequency of launches not only fuels overproduction and waste, but also creates an unsustainable cycle of consumption, in which clothes quickly become stylistically perishable. These practices, thus, raise serious questions about the real commitment of these brands to sustainability, even when they promote marginal green initiatives.

2.3. Consumer Awareness and Behavior

Marketing strategies applied in the fashion industry must take into account the promotion of sustainability, starting with informing and educating the public and continuing with clear and objective examples. All the organization’s efforts should eventually translate into marketing strategies that can help organizations to escape the social trap of climate change. Gonzalez-Padron and Nason (2009) [

15] note that by internalizing societal goals, firms can respond effectively to the market through their marketing strategies. Building on this market-oriented notion, Sheth and Parvatiyar (2020) [

16] argue that market-oriented marketing strategies are the key to the environmental and ecological challenges facing societies.

The benefits of sustainable products and the negative impact of fast fashion on the environment must be clearly communicated. Awareness campaigns, educational articles, events and collaborations with influencers can be effective solutions to promote a sustainable lifestyle. Authentic marketing messages that contain the results of sustainability commitments and show real and measurable actions become extremely useful tools in influencing the public.

Transparency in information campaigns should not be lacking, this can be ensured through sustainability reporting, eco-certifications and product traceability. Companies’ transparency and reporting on sustainability work can strengthen consumer trust. Moreover, marketing in the digital age needs to be innovative and adapted to current trends, and the attention of the audience needs to be captured through campaigns tailored to age groups, time spent on different social networks, etc. Currently, interactive content (educational videos, sustainable styling tutorials, or recycling campaigns) successfully attract the attention of a young and engaged audience.

2.4. Marketing Strategies for Sustainability

The fast fashion companies have factories in developing areas, which means that the workforce is very low paid, they are stuck in poverty, and sell their products on international markets at very high prices for huge profits. The lack of clear regulations and the low bargaining power of the workers lead to economic inequality. Moreover, the globalization of fashion is leading to the uniform spread of trends and styles, which can lead to a loss of cultural identity and reduced diversity in fashion. An indirect effect of the globalization of fashion can be an increased demand for cheap and fast production, affecting local artisans and traditional crafts that cannot compete with mass production. The fashion industry can be made more responsible by investing in green technologies, respecting workers’ rights and protecting the environment. The fashion industry’s impact on the environment is complex, and the consequences are felt globally. Implementing sustainability in the fashion industry is possible by involving brands, governments, and consumers alike.

In addition, the influencer marketing trend has gained great popularity, and collaborations with celebrity sustainability advocates can amplify the message and increase brand visibility. Fashion companies need to build a community that sees sustainability as a moral norm. By organizing sustainable events and initiatives, brands strengthen customer loyalty and help to educate and mobilize customers towards a more responsible lifestyle.

2.5. Barriers to Sustainable Fashion

The fashion industry is increasingly influential, playing an important role in both the economy and culture. Although it has direct implications for economic growth, the fashion industry is also controversial because of its negative impact on the environment and society. The fashion industry has experienced a remarkable expansion in the last two decades, especially with the consolidation of the fast fashion approach, which emphasizes an entrepreneurial mode of rapid acquisition and disposal of mass-produced, homogeneous, and standardized fashion items [

17]. Fast fashion is characterized by rapid production and excessive consumption of items, which causes serious sustainability issues. The consequences of fashion such as environmental pollution and massive consumption of natural resources are obvious, and, thus, urgent attention is needed.

The challenges of implementing sustainability strategies and associated marketing are often the high costs of green materials, the complexity of supply chains, and the reluctance of some consumers to pay higher prices.

These obstacles can be overcome by increasing demand for sustainable products and the emergence of new technologies that offer significant opportunities for brands embracing sustainability. Increased consumer awareness of sustainability is driving fashion brands to be more transparent in their business and adopt sustainable practices. Moreover, responsible companies will benefit from increased loyalty and favorable market positioning.

2.6. The Circular Economy and Future Directions

Sustainability in fashion has started its evolutionary journey from a simple marketing-focused ‘corporate social responsibility’ initiative to becoming an integrated part of the strategic planning system. Although sustainability has recently been seen as a competitive advantage in most industries, academic research on sustainability in the fashion industry has been slow to adapt to this paradigm. It is, therefore, not surprising that there is no precise definition of sustainability in this field [

18].

In general terms, sustainability marketing involves building and maintaining sustainable relationships with customers, the social environment, and the natural environment [

19]. In recent years there has been an increased interest in sustainability and ethical practices in the fashion industry [

20], an interest accompanied by demands for advancing the sustainability marketing mix [

21]. Thus, the fashion industry needs to become a model of environmental and social responsibility, which is made possible by using high quality, environmentally friendly materials in the manufacture of products, and optimizing manufacturing processes. Moreover, the fashion industry must be based on a circular economy model. Thus, marketing has an important role to play in consumer education and mobilization activities, having a direct influence on the sustainability implementation process.

Although the adoption of sustainability in the fashion industry may seem cumbersome, companies need to take into account the multitude of long-term benefits for themselves, society, and the environment.

Taking all these challenges into account, the fashion industry needs major changes to become more sustainable and fair. The circular economy can be an effective model where clothes are recycled or reused to reduce waste and protect the environment. Moreover, consumers need to adopt more responsible consumer behavior, choose sustainable products, and support brands that promote ethical and responsible practices. Companies also need to implement sustainability, ensure transparency at all stages of production, and re-evaluate supply chains. The fashion apparel industry has evolved significantly, especially in the last 20 years as the boundaries of the industry have begun to expand [

22]. Sustainability drives faster progress towards a fairer business model that respects both the environment and human rights. A sustainable future in the fashion industry can be ensured through a responsible and conscious approach.

3. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Transparency and Innovation in the Fashion Supply Chain

In recent years, social and environmental sustainability has become a key managerial issue [

23]. Increasing pressure from consumers and environmental organizations on the fashion industry is driving the need for responsible and sustainable practices. With their increasing awareness of the sustainability challenge, companies have started to work on the internal processes and products they provide [

24,

25]. It is important that both supply chain and production processes are transparent. The fashion industry can turn into a sustainable business model if innovation in materials and production processes is promoted. However, as the management of social and environmental issues does not stop at the enterprise boundaries, organizations need to extend their attention to the supply chain network [

26,

27].

Accountability and ethics in the sourcing of raw materials and materials as well as in the production process must become mandatory. Lack of consumer interest in prioritizing sustainability in clothing choices, ineffective communication with consumers regarding the purchase of sustainable clothing, and low consumer confidence in retailers’ claims about their sustainable activities [

28] are the biggest hindrances to the implementation of sustainability in the fashion industry. Some consumers do not believe that “ethical clothes” are authentic [

29] or do not trust companies’ transparency regarding ethical production and eco-friendly product ranges [

30]. Such barriers can be removed through marketing programs that effectively promote company actions.

The successful marketing of innovations which contribute to sustainability is more than a product development challenge [

31]. By choosing sustainable products, consumers indirectly force producers to adopt more ethical and responsible practices. Companies that implement sustainability in their operations and demonstrate a commitment to social and environmental responsibility are more likely to gain the trust of their target audience. In the fashion industry, innovation in sustainable materials and production processes is essential, so companies need to invest in research and development to create products from biodegradable or recycled materials in order to reduce environmental impact.

Innovations must be promoted through effective marketing strategies, highlighting the benefits for both the environment and consumers. Targeted marketing campaigns emphasizing innovative solutions will stimulate the public to buy sustainable products. The fashion industry can be transformed into a sustainable sector by adopting innovative solutions to protect the environment, promoting transparency in sourcing and production, and becoming a direct promoter of social and environmental responsibility. Given these results, the paper proposes the following hypotheses:

H1: Transparency in supply chain and production processes (TSC) has a significant positive influence on improving brand reputation and credibility (IBR).

Similarly, innovation in sustainable materials and production methods, when effectively promoted through marketing, can enhance the perceived value of a brand and strengthen its image as environmentally responsible.

H2: Promoting innovation in sustainable materials and production processes through marketing strategies (PIS) has a significantly positive influence on improving brand reputation and credibility (IBR).

3.2. Sustainability Commitment and Market Expansion

The fashion industry is undergoing a continuous transformation in the context of environmental and social awareness. This includes innovation in more sustainable materials and manufacturing processes, effective promotion through targeted marketing strategies and access to new markets. Fashion companies’ commitment to sustainability is key to redefining the future. The development of responsible materials and production processes in the fashion industry is possible by promoting innovation. Furthermore, Faisal (2010) [

32] shows that a fashion company’s long-term sustainability vision can significantly contribute to the overall improvement of brand image. The literature also emphasizes that sustainability approaches support an improvement in business performance, especially in financial indicators [

33]. Lo, Yeung and Cheng (2012) [

34] discussed the positive influence that environmental sustainability has on business performance. By integrating sustainability into their activities, companies invest in the development of manufacturing processes, the use of advanced technologies, recycled fibers and biodegradable materials or textiles produced through low-water and low-energy manufacturing processes.

By adopting sustainable innovations companies have access to new markets and multiple growth opportunities as consumers have become increasingly interested in sustainable products. Moreover, integrating sustainability practices into the business model more quickly attracts target audiences that value social and environmental responsibility. The target audience needs to identify with the brand’s values and to be committed to the environment. From an environmental perspective, sustainable purchasing leads fashion companies to pay more attention to the choice of environmentally friendly materials (such as recyclable and recycled materials) [

35].

In terms of the social dimension, sustainable procurement involves identifying suppliers that adopt practices that respect workers’ rights and improve social conditions. By investing in innovation and sustainability, brands can expand and increase their popularity and become an example for other organizations. In this way, fashion brands can build relationships with customers, increase brand awareness, boosting sales for sustainable products [

36].

Innovation is vital for businesses to achieve sustainable development [

37]. Traditional market- and finance-oriented innovation is not as complex as innovation motivated by sustainability goals, where much more account must be taken of multiple stakeholders whose interests may align or cause conflicting tensions [

38]. There are benefits for both stakeholders and the business when creative ideas and solutions are generated.

Times have changed a lot, and with them the rules of green marketing. Distrustful of government and authority, they are quick to challenge marketing practices they deem to be unauthentic or untruthful [

39]. A strong commitment to sustainability translates into concrete actions, clear measures, supply chain transparency and fair labor practices. The brand’s commitment to sustainability must not remain just an intention, the company must demonstrate that it is delivering on its commitments through transparent actions and processes. Marketing has an important role to play in promoting these actions as sustainability actions need to be highlighted and consumers need to be informed and aware of the positive impact of their choices. Effective marketing strategies should highlight how the brand contributes to protecting the environment [

40].

Given that the transportation and logistics of fashion products intensify the negative impacts of greenhouse gas emissions, and the packaging of disposed products adds an environmental burden [

41,

42] a strong commitment to sustainability by companies is needed. Implementing sustainable supply chain management to integrate and coordinate the triple bottom line: economic, social and environmental, including economic, environmental and social performance [

43], is a key strategy for the fashion industry. In addition, digital technology has enabled both the development of new materials and fabrics that are more durable than traditional materials and faster production times as well as improved quality control processes, resulting in higher quality products at lower costs [

44]. O’Rourke (2014) [

45] highlights that fashion brands are increasingly adopting initiatives across the entire supply chain, from raw materials to end-of-life practices like reuse and remanufacturing.

In this way, the brand can enjoy enhanced reputation and consumer confidence in its commitment to sustainability. Innovation in sustainable materials and production processes is a first step in adopting sustainability. By embracing innovation access to new markets and consumer groups that make responsible choices is much faster.

Also, Li and Calantone (1998) [

46] show that the three processes of customer knowledge, competitive knowledge and marketing interface positively affect innovation, and through innovation a firm’s performance is influenced. Market knowledge encourages the generation of new product ideas and the utilization of these ideas to take advantage of market opportunities, which in turn increases business performance [

47].

Marketing strategies that emphasize the company’s sustainable business lead to improved public reputation and credibility. Sustainable business contributes to a more sustainable future for the industry as a whole. All companies should take sustainability into account, moving towards sustainability is not only an opportunity for growth but also a moral responsibility towards the environment and society. Given these findings, the paper proposes the following hypotheses:

H3: Promoting innovation in sustainable materials and production processes through marketing strategies (PIS) significantly positively influences access to new markets and growth opportunities (ANM).

In the same vein, a brand’s commitment to sustainability through concrete actions, such as ethical labor practices, transparent sourcing, and eco-conscious production, can strengthen its position in the market. These visible efforts build trust and make the brand more attractive to environmentally and socially aware stakeholders, creating access to new markets and growth opportunities.

H4: Brand commitment to sustainability through concrete actions (BCS) significantly positively influences access to new markets and growth opportunities (ANM).

3.3. Marketing Strategies to Educate and Sensitize Consumers on Sustainability Issues in the Fashion Industry

The fashion industry is constantly changing, and sustainability is necessary in this sector. Consumer awareness of sustainability issues is, thus, becoming increasingly important. As slow fashion consumers make purchases based on sustainability and the desire for exclusive and timeless products [

48], consumers see quality over quantity, which can express a thrifty way of consumption.

Berg et al. (2019) [

49] consider fashion’s commitment to environmental sustainability as a top priority. So far, the majority of research on sustainability in the fashion industry has been devoted to sustainable supply chain management issues [

50]. This is not surprising, given the prominence of both supply chain operations in fashion apparel and the increasing pressures for sustainability efforts [

51].

Creating communities committed to sustainability and collaborating with non-governmental organizations and other brands that share the same values contributes to both protecting the environment and creating a positive brand image.

The digital transformation is having a significant effect on the fashion industry. It has revolutionized fashion communication and marketing, enabling more effective customer relationships and business operations. It has also enabled advances in fashion design and production, such as sustainable manufacturing and improved decision-making processes [

52]. By using marketing and creating information campaigns, consumers can be informed about the impact of their purchasing choices.

The modern consumer is not only paying attention to the social ramifications of fashion, but is becoming increasingly aware of the social and environmental impacts of textile and clothing products [

53,

54]. In order to reduce the social and environmental impacts of clothing, fashion organizations are beginning to adopt, develop, and implement social responsibility policies and programs throughout the life cycle of their products [

55].

Companies have been looking for a way to implement sustainability strategies [

56] while maintaining consumer appeal. Open and informed dialog enables brands to raise consumer awareness and encourage consumers to make responsible choices. By organizing workshops or presentations of sustainable products, companies can encourage consumers to choose sustainable products, thereby reducing environmental impacts. As technology advances, so will digital marketing strategies, enabling companies to reach target audiences quickly and effectively [

57].

Active communities help spread the sustainability message while increasing consumer loyalty. Moreover, companies can collaborate with non-governmental organizations or other companies that share sustainability values, amplifying the impact of marketing initiatives. Partnerships with environmental organizations can provide businesses with the necessary information [

58] to run sustainable processes.

Individual barriers include a personal desire for new or perceived new products, services and experiences. It is a challenge for individual consumers to completely eliminate hedonistic needs, such as recreational or impulse buying. At the social level, consumers have been strongly influenced by their peer groups, especially young consumers, who experience feelings of dissatisfaction through constant comparison with peers and reference groups [

59].

Some contributions suggest several sets of practices that companies should implement to promote sustainability, such as reducing packaging and waste [

60], considering environmental performance in the selection of suppliers [

61], developing greener products [

62,

63], reducing carbon emissions during the production and distribution of goods (Walker et al., 2008), training suppliers to improve their green capacity [

63], working with suppliers [

64], and developing reverse logistics systems [

65].

Collaborations with non-governmental organizations and other brands that share the same sustainability values lead to the creation of innovative products and joint campaigns that reach a wider audience. Moreover, these partnerships have the potential to amplify the sustainability message, creating synergies that benefit all parties involved. Communication and marketing are an essential part of any successful fashion brands as they help to ensure customer awareness of the products and services offered by fashion entities [

66]. Gleim et al. (2013) [

67] state that consumers not only need to be informed about green products and relevant benefits, but also about what makes the product green. Sustainability, thus, becomes an integral part of brands’ identities and consumers are encouraged to participate in this transition. Given these results, the paper proposes the following hypotheses:

H5: Marketing strategies to educate and sensitize consumers on sustainability issues in the fashion industry (MSE) significantly positively influence the creation of a sustainable engaged community (CEC).

Likewise, raising consumer awareness about sustainability not only increases engagement but also strengthens the brand’s positioning as a credible sustainability advocate. This reputation facilitates partnerships with non-governmental organizations and other like-minded brands that value ethical practices, transparency, and environmental responsibility.

H6: Marketing strategies to educate and raise consumer awareness of sustainability issues in the fashion industry (MSE) significantly positively influence collaboration with non-governmental organizations and other brands that share their sustainability values (WNO).

3.4. Collaboration with Non-Governmental Organizations and Sustainable Brands

Fashion brands with a sustainable business model often choose to collaborate with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other brands that share the same values. These collaborations facilitate access to new markets and the creation of an engaged community. The collaborative advantages that environmental partnerships can offer to both firms and environmental organizations have shown enormous potential over the past two decades.

Because there are significant pressures on firms to reduce their harmful environmental impacts, partnerships with environmental organizations can be a source of information and knowledge (Rondinelli and London 2003). They can help firms review their operational activities, identify marketing opportunities, develop new products, and respond to stakeholder concerns. Thus, the sustainable business model is not limited to reducing negative environmental impacts, but extends to collaborations with NGOs. Consumers are one of the main promoters of sustainability marketing initiatives [

68,

69]. In terms of sustainable fashion marketing, the public dimension should be extended to include human capital along the fashion supply chain.

Collaborations with other companies can generate joint sustainability initiatives that generate a greater positive impact and appeal to a wider audience, thereby enhancing the reputation of each party involved. Fashion brands are increasingly participating in a multitude of initiatives that collectively encompass the entire supply chain, including raw materials, retail, consumption, and end-of-life initiatives (take-back, reuse, and remanufacturing initiatives) [

18].

Collaborative efforts help to address one of the key characteristics of the sustainable supply chain in the fashion industry often mentioned in the literature—transparency [

18]. While the responsibility for social, environmental, and economic impacts along a supply chain does not lie solely with fashion brands, they are increasingly becoming more accountable for environmental consequences [

18,

70,

71].

Moreover, consumers have become increasingly knowledgeable and have quick access to information, so brands in the fashion industry need to be transparent about their actions. In the fashion industry, the sourcing of sustainable fabrics is a decision of the management or fashion designers [

72]. From a marketing perspective, this decision influences aspects such as the market potential of fashion items [

73] and their adoption by customers [

74]. According to Rath et al. (2014) [

75], the public associates materialistic concerns with environmental impacts, realizing that the desire to consume more and more is not environmentally sustainable. To maintain this balance, fashion marketers’ priorities need to change.

Transparency in the supply chain and production processes is essential to gain consumer trust and avoid scandals that can seriously damage a company’s image. Fashion companies can demonstrate their commitment to sustainability by minimizing environmental and human rights risks. Sustainable sourcing may require companies to closely scrutinize suppliers to assess their environmental and social responsibility efforts [

27], as the company is primarily responsible for aligning sustainable actions throughout its supply chain.

By making processes and actions transparent, the company’s reputation is protected and consumer loyalty is fostered, making consumers feel more connected and confident in their consumer choices. A community committed to sustainability made up of consumers, employees, suppliers, and business partners is the driving force that can promote and support the company’s sustainability initiatives. Both the open dialog between the company and consumers, and the active involvement of the community in decision-making processes, enable the development of innovative solutions and the rapid adaptation of strategies to address community needs and concerns. Specifically, research suggests that, through effective marketing strategies, firms have the potential to (1) entrench product-relevant social good [

76], (2) shape product capability development [

77], (3) collaborate with multiple stakeholder groups for societal welfare through value creation [

78], (4) influence product-market strategy decisions toward business performance [

79], and (5) influence strategic marketing implementation [

80].

Companies in the fashion industry must take into account the demands of a changing market and the need to implement sustainability for a sustainable future and to remain competitive. Given these findings, the paper proposes the following hypotheses:

H7: Collaboration with non-governmental organizations and other brands that share their sustainability values (WNO) positively and significantly influences access to new markets and growth opportunities (ANM).

In a similar manner, transparency in supply chains and production processes increases consumer trust and strengthens perceived brand authenticity. This openness encourages the formation of an engaged community that values ethical practices and seeks active involvement in sustainability initiatives.

H8: Transparency in supply chain and production processes (TSC) significantly positively influences the creation of an engaged community (CEC).

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Conceptual Model and Variables

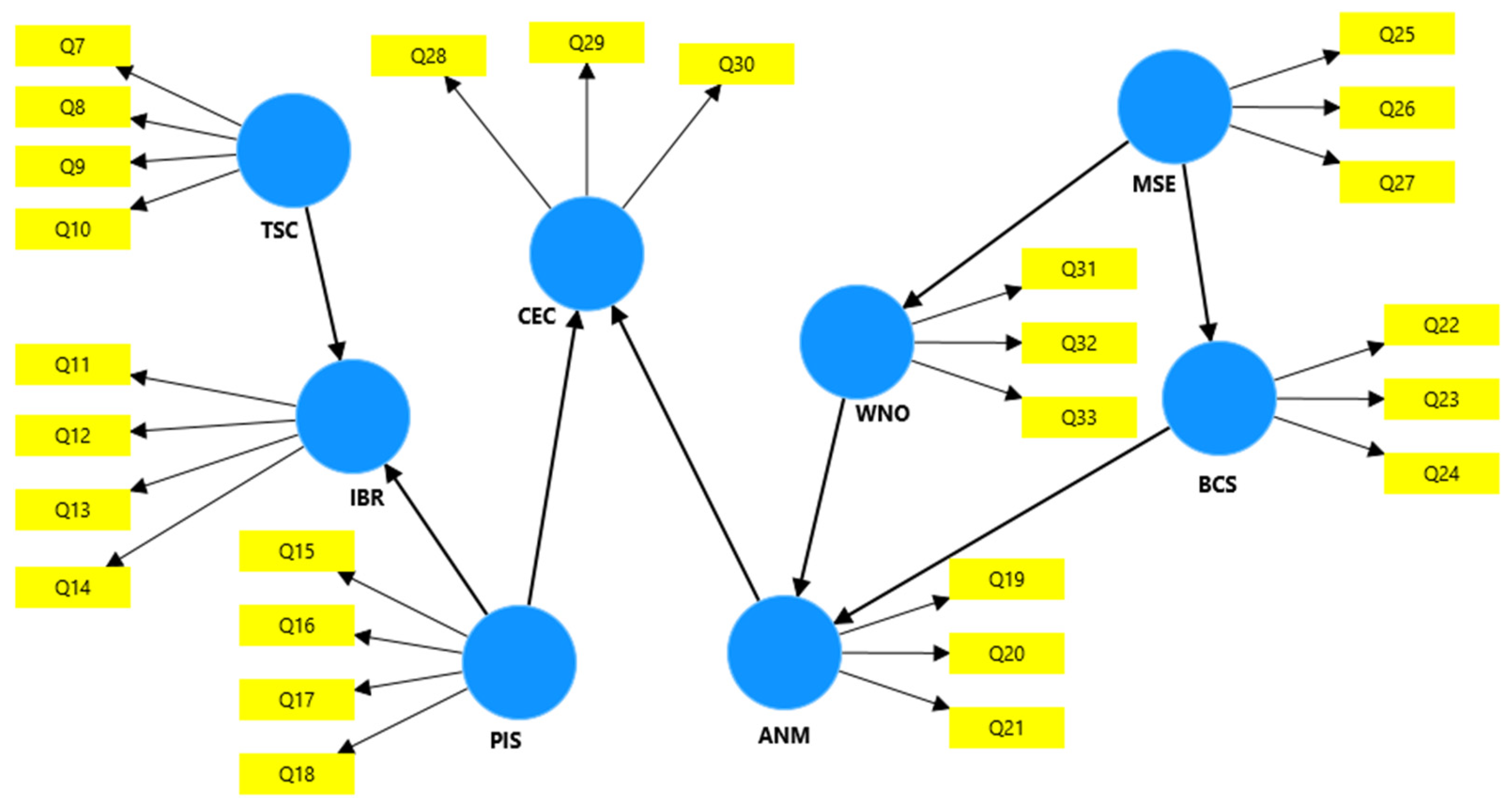

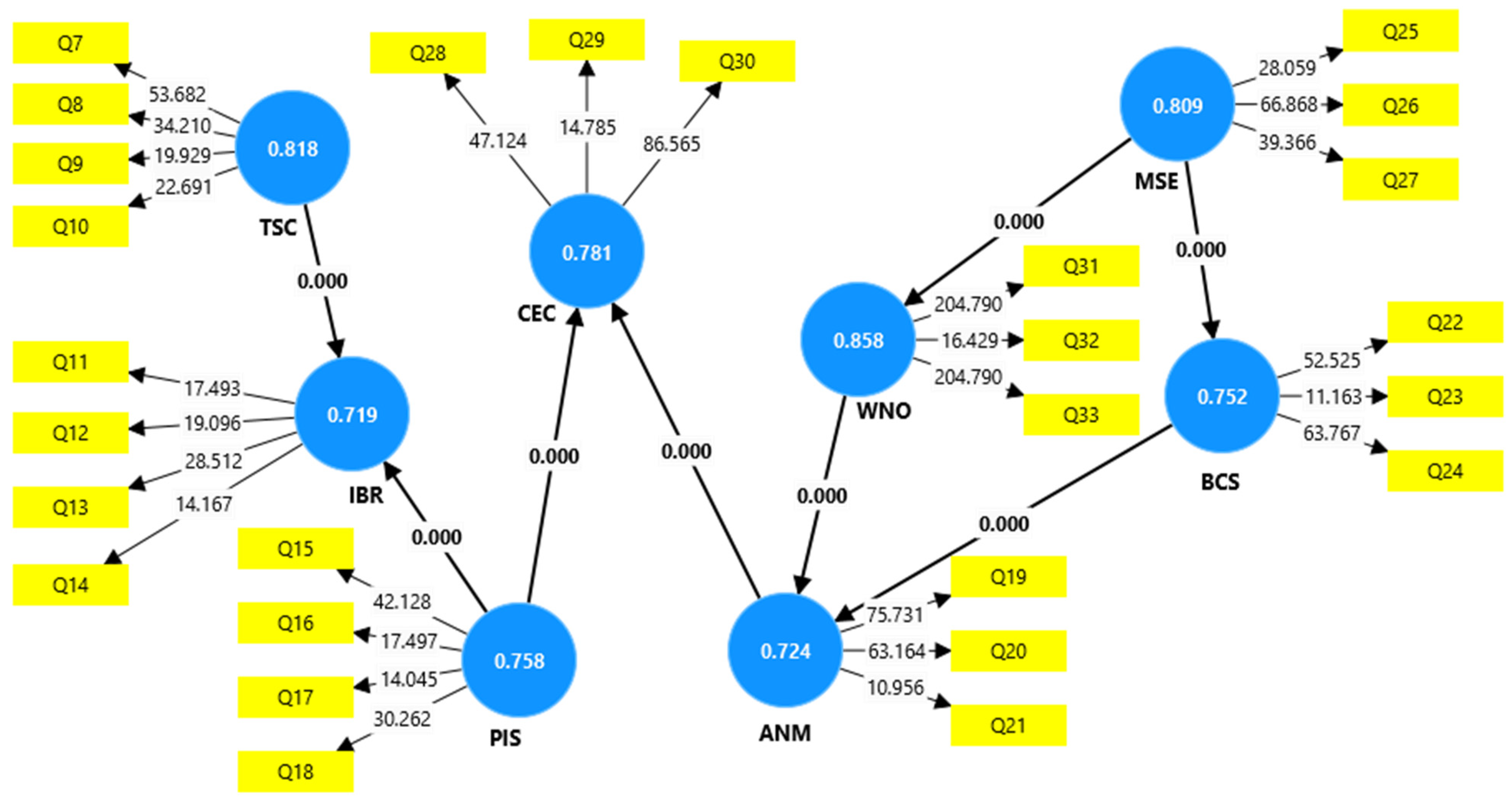

Having defined the theoretical framework and presented the research hypotheses, we developed a conceptual model in order to investigate the factors that could positively influence the promotion of sustainability in the fashion industry. The conceptual model is illustrated in

Figure 1, which shows several variables with an influencing role on the development of sustainable fashion. The list of variables includes the following:

Supply chain and production process transparency (TSC);

Improving brand reputation and credibility (IBR);

Promoting innovation in sustainable materials and production processes through marketing strategies (PIS);

Creating an engaged community (CEC);

Brand commitment to sustainability through concrete actions (BCS);

Access to new markets and growth opportunities (ANM);

Marketing strategies to educate and raise consumer awareness of sustainability issues in the fashion industry (MSE);

Working with non-governmental organizations and other brands that share their sustainability values (WNO).

Based on the identified variables, a set of items was developed to operationalize the constructs included in the research model. These items, formulated in the form of questions, constituted the content of the questionnaire, which served as the main data collection instrument. The questionnaire was disseminated to professional groups associated with various companies in the Romanian fashion industry for empirical data collection. Following the establishment of the theoretical framework through a thorough literature review, the identified variables (considered potential influencing factors in the development of innovative business models) were empirically tested. Accordingly, hypotheses were formulated and subsequently examined through primary research using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with SmartPLS4 software.

That this method is suitable for the present research because it provides the possibility to test a theoretical framework from a prediction perspective. In addition, the proposed structural model is complex, comprising constructs, indicators, and relationships between them. SEM-PLS is the most efficient statistical model in social science capable of measuring the relationships between several variables at the same time [

81].

In the present research, the choice of structural equation modeling using the partial least squares technique (PLS-SEM) over other methods of correlational analysis is justified by the ability of this method to simultaneously set up and estimate complex relationships between two or more dependent and independent variables. This approach is particularly appropriate to the research topic and objectives. In the process of evaluating the relationships, the SmartPLS4 software takes into account the measurement error of the observed variables, thus providing a clearer and more accurate assessment of conceptual models in socio-economic analysis.

The structural model developed is presented in

Figure 1, where we highlight the relationships between variables by means of the eight hypotheses detailed in

Section 2. The indicators used in the research are referred to as items (manifest variables) and represent the directly measured variables comprising the results of the questionnaire-based analysis. In the diagram, the indicators are represented as rectangles and the relationships between variables, respectively, between variables and associated indicators, are illustrated by one-way arrows, assessed as predictive relationships or causal relationships. The variables are also represented as blue circles, being reflected by several items in the questionnaire.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model of research based on modeling by structural equations. Source: Smart PLS 4 software processing.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model of research based on modeling by structural equations. Source: Smart PLS 4 software processing.

4.2. Data Collection and Sample Characteristics

Data were collected using the questionnaire between 2 September 2024 and 21 October 2024. The questionnaire was distributed on the profile groups of different companies in the Romanian fashion industry and was completed by fashion enthusiasts. The questionnaire, composed of 33 questions, was structured in two sections. The first section contains questions aimed at identifying the respondent’s profile, including background, age, education, gender, income, and occupation. The second section contains Likert scale questions and five-step semantic differentials targeting the research variables.

For this research, we obtained a total of 227 responses using convenience sampling. The questionnaire was distributed online through profile groups in social networks and professional communities in the Romanian fashion industry. According to the criteria presented by [

82,

83,

84] the sample size exceeds the recommended thresholds for model stability and statistical power in PLS-SEM analysis. Therefore, the sample is adequate for the research objectives and the application of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM).

In total, 153 women and 74 men took part in the survey, with a distribution according to background: 62% of the respondents were from urban areas, and 38% from rural areas. In terms of respondents’ age, 45% of respondents fall into the 21–30 age category, 28% into the 31–40 age category, 15% into the 41–50 age category, and 12% in the over 51 years of age. More than 76% of the respondents have higher education and 24% have secondary education. Although a large proportion of respondents (43%) emphasize quality and indicate the need to maintain high product standards, the majority of respondents consider price as the deciding factor, indicating cost sensitivity. Thus, business strategy needs to incorporate a balance between offering a high standard of products and maintaining competitive prices. Therefore, success may depend on the ability to combine the two requirements and customize the offer for each type of customer.

4.3. Research Instrument and Measures

Table 1 below presents in detail the items in the questionnaire, the scales used and the percentages recorded for each response option.

Table 1 provides an essential summary of the items used in the research, together with descriptions, response options, and data obtained. It is an important resource for understanding the methodology and results of the study. Detailing the items used helps clarify the research objective. In addition, explaining the response options is essential to understanding how the subjects’ perceptions and attitudes were measured. This influences how the data are interpreted and analyzed. The presentation of the data obtained provides a basis for the research conclusions.

Table 1, thus, serves as a reference point for all aspects of the research, from the formulation of hypotheses to the interpretation of results.

5. Data Analysis

5.1. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM-PLS) Approach

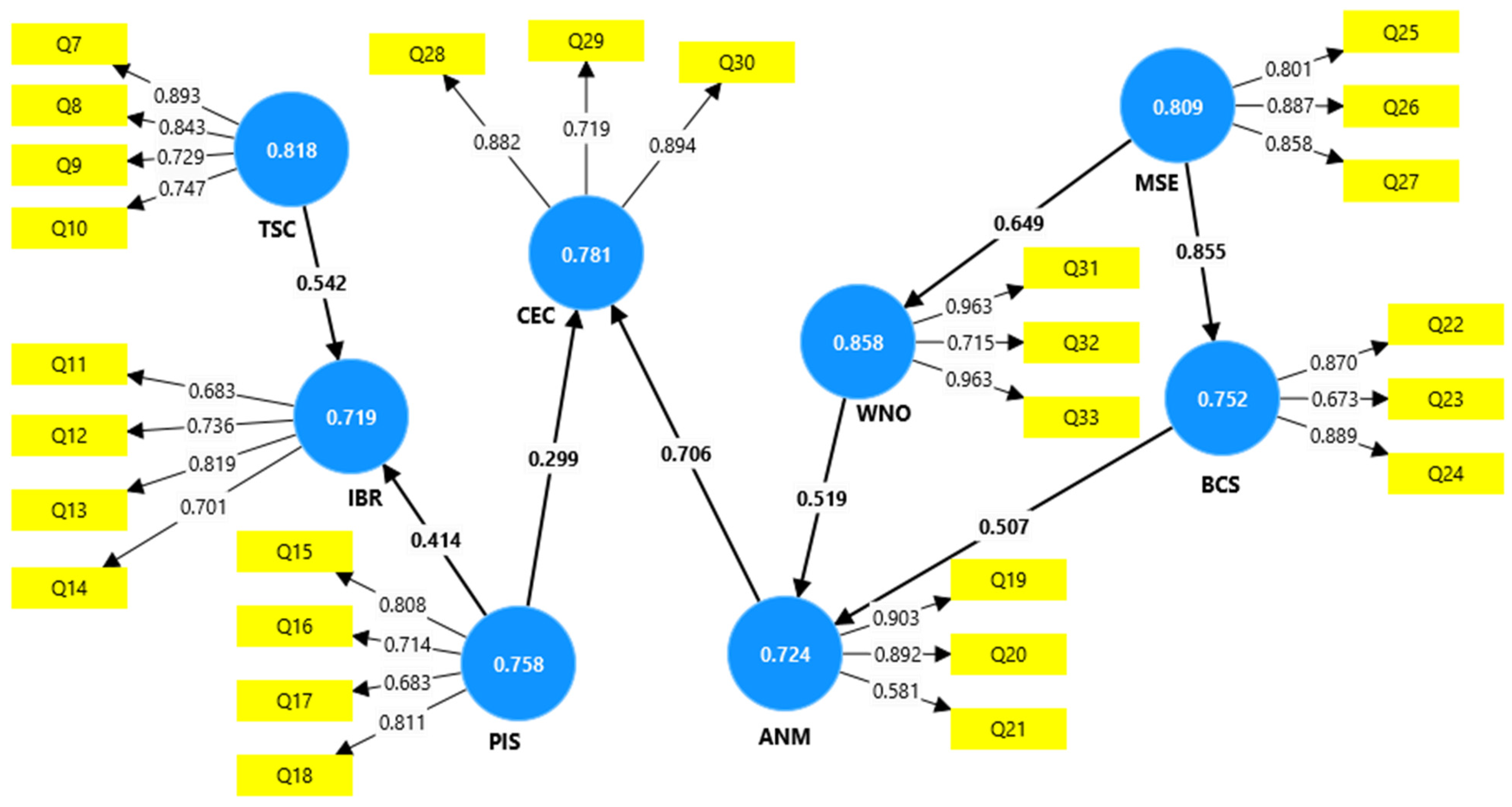

In

Figure 2, we presented the relationships between the latent variables included in the research model. The arrows indicate the direction of the relationship, starting from the exogenous latent variable, considered as a predictor, to the dependent (endogenous) latent variable. This diagram shows the variables that can be measured by a reflective approach, where the arrows are directed from variables to indicators.

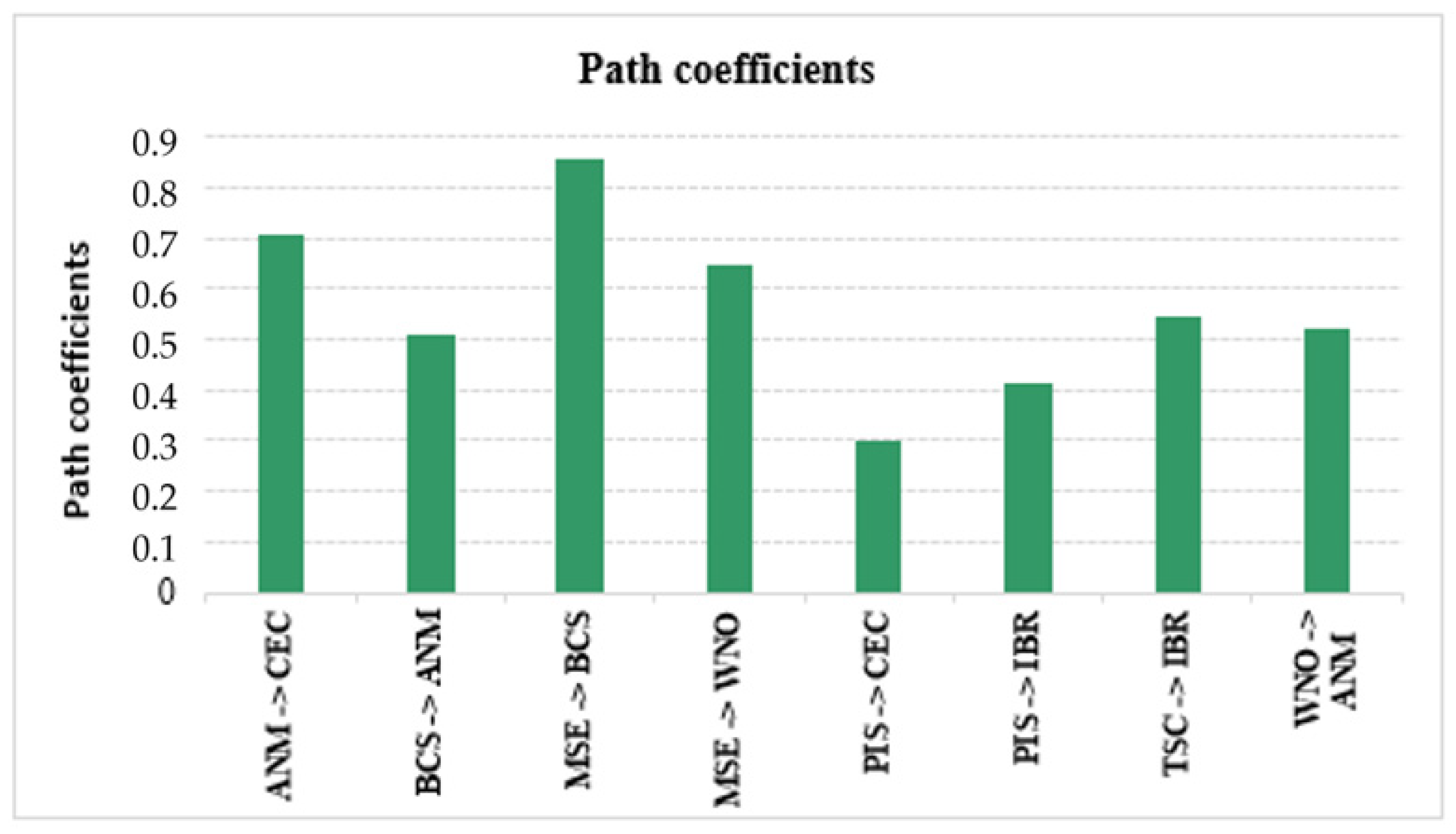

From the structural model we observe that the strongest relationship is between (1) MSE (marketing strategies to educate and sensitize consumers on sustainability issues in the fashion industry) and BCS (brand commitment to sustainability through concrete actions), where the coefficient of relationship is 0.855, followed by the relationship between (2) ANM (access to new markets and growth opportunities) and CEC (creating an engaged community), where the coefficient of relationship is 0.706. Another strong relationship is shown between MSE (marketing strategies to educate and sensitize consumers on sustainability issues in the fashion industry and WNO (working with non-governmental organizations and other brands that share their sustainability values), where the coefficient of relationship is 0.649.

Moderate relationships are shown between (1) TSC (transparency in supply chain and production processes) and IBR (enhancing brand reputation and credibility), relationship coefficient of 0.542, (2) WNO (working with non-governmental organizations and other brands that share their sustainability values) and ANM (access to new markets and growth opportunities), relationship coefficient of 0.519, between (3) BSC (brand’s commitment to sustainability through concrete actions) and ANM (access to new markets and growth opportunities), where the relationship coefficient is 0.507 and between (4) PIS (promoting innovation in sustainable materials and production processes through marketing strategies) and IBR (enhancing brand reputation and credibility), where the relationship coefficient is 0.414. A weaker relationship is shown between PIS (promoting innovation in sustainable materials and production processes through marketing strategies) and CEC (creating a sustainably engaged community), the relationship coefficient is 0.299.

The relationship coefficients are calculated using SmartPLS 4 software, graphically illustrated in

Figure 3 and detailed in

Table 2. The strongest correlation is between the variables MSE and BCS (relationship coefficient 0.855), and the weakest correlation is between the latent variables PIS and CEC (relationship coefficient 0.299).

5.2. Model Evaluation: Validity and Reliability

To assess the internal consistency of the research instrument, we calculated the Cronbach Alpha coefficient. This coefficient measures the degree of correlation between variables within the structural model. According to Hair et al. (2021) [

81], values of 0.60 to 0.70 are acceptable in exploratory research for this coefficient. We observe that following the application of Cronbach Alpha, all the variables in the research obtained values exceeding the threshold of 0.7, these are presented in

Table 3. Thus, we identify that a significant internal consistency of the variables in the structural model was obtained.

Another indicator used to check the internal consistency of the collection instrument is the composite confidence level (CR). It is used to check how well the items of a factor measure the same latent construct and is an alternative to Cronbach’s Alpha. Like Cronbach’s Alpha, the composite confidence level (CR) is an indicator of reliability similar to Cronbach’s Alpha, and its values considered acceptable should exceed the threshold of 0.7. Also, analyzing the relationship between Cronbach’s Alpha and CR [

85] suggest that these two analyses can be used alternatively. Thus, as can be seen, the internal consistency and convergent validity requirements of the model are met.

In this research, we observe that the composite confidence level exceeds the recommended minimum threshold for all eight reflective variables (ANM, BCS, CEC, IBR, MSE, PIS, TSC, WNO). The CR reflects the correlation between the observed variables (items) and the latent construct it measures, providing a more accurate measure of internal reliability in some situations than Cronbach’s Alpha, as the CR takes into account item weights and item errors. Spearman (Rho) is a rank correlation coefficient and is a non-parametric test used to measure the strength of association between two variables, where r = 1 means a perfect positive correlation and r = −1 means a perfect negative correlation. We notice a positive correlation for the eight reflective variables (ANM, BCS, CEC, IBR, MSE, PIS, TSC, WNO).

AVE (Extraction Variance Average) assesses the convergent validity of a latent construct in a measurement model. The acceptable threshold for AVE is 0.50 [

86]. Convergent validity measures how well latent variables represent the variability of their indicators. A higher AVE value indicates better adequacy of the latent variables in explaining the observed variation in the indicators. We observe that all the eight reflective variables (ADB, AFE, CES, IIT, IMT, LMT, LSC, OSC) have AVE above the recommended threshold. Thus, the items are good indicators of the construct represented.

To assess discriminant validity, the Fornell Larcker criterion compares the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) with the correlations between the latent variables. The square root of the AVE of each construct should be greater than the correlation between the constructs (Pearson correlation) to satisfy the discriminant validity requirement [

87]. This indicates that a latent variable explains its own variance better than the variance shared with the other latent variables, thus supporting the discriminant validity of the measured constructs. According to the Fornell Larcker criterion a latent construct should be better correlated with its own indicators than with other indicators measuring other latent constructs.

In other words, each construct should be distinct and not overlap with other constructs in the measurement model. Aspect confirmed in this research because the AVE values for the eight reflective variables ANM (0.851), BCS (0.854), CEC (0.835), IBR (0.837), MSE (0.850), PIS (0.792), TSC (0.826), and WNO (0.808) are higher than the correlations with the other latent variables, illustrated under the main diagonal in

Table 4. Discriminant validity refers to the degree to which a variable is distinct from other latent variables in the model, i.e., the extent to which each construct measures something unique and does not overlap with others.

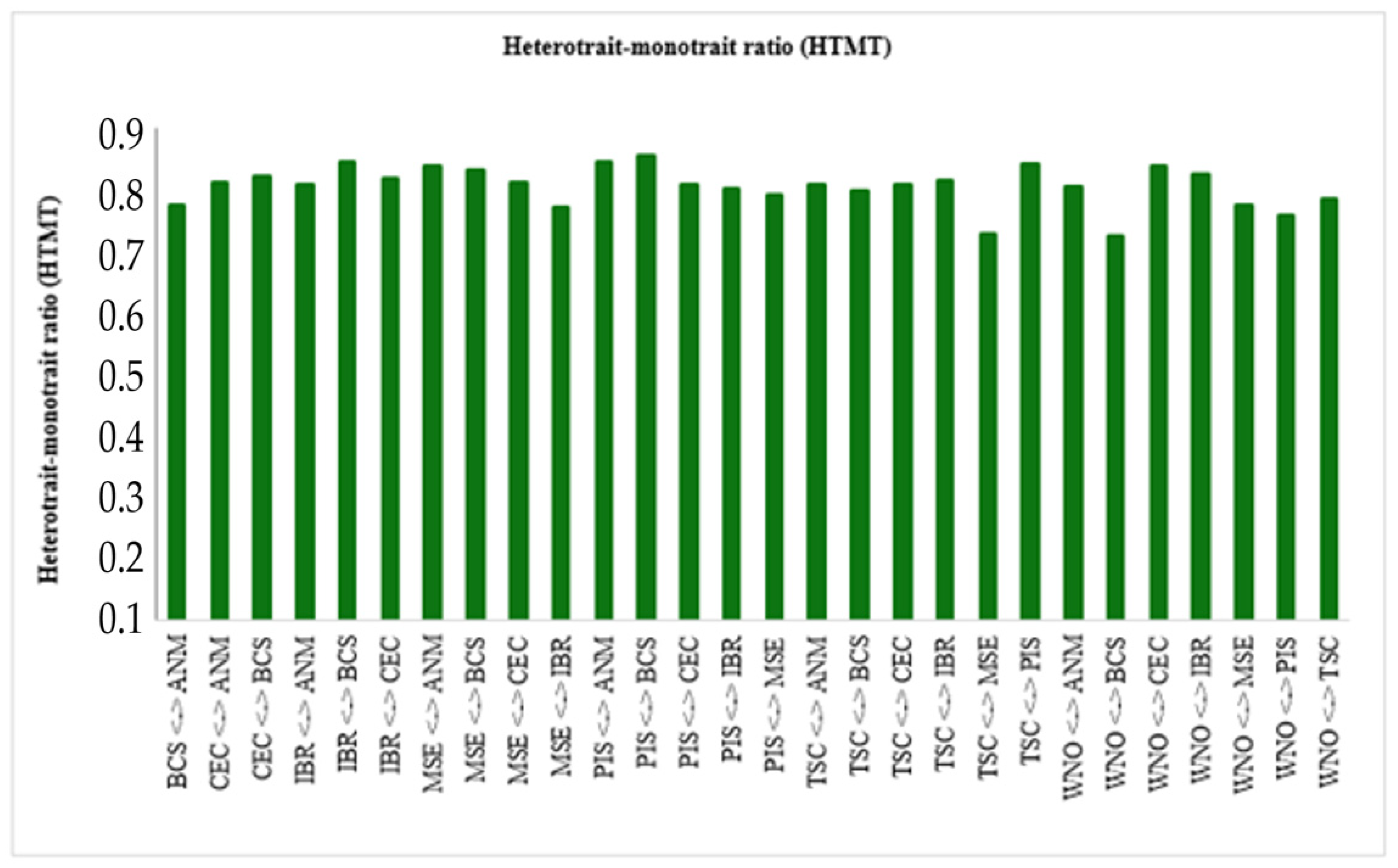

Another measure for discriminant validity is the Heterotrait Monotrait (HTMT) correlation ratio, this indicator compares the correlations between indicators of the same construct (monotrait) with the correlations between indicators of different constructs (heterotrait). HTMT values close to 1 indicate a lack of discriminant validity. If the HTMT value is higher than the minimum threshold of 0.85, it can be concluded that there is a lack of discriminant validity. The HTMT ratio values are considered acceptable when they are below the conservative threshold of 0.85. We observe that the Heterotrait Monotrait (HTMT) correlation ratio is below the 0.85 threshold for all structural relationships between variables (

Figure 4), these values ensure that the measurements are clear and distinct between the different constructs analyzed. The values are detailed in

Table 5.

Multicollinearity among a set of variables in a multiple regression is measured by the variance inflation factor (VIF). High multicollinearity is indicated by values greater than 5, multicollinearity occurs when two or more independent variables are highly correlated with each other, which can distort the results of a regression analysis, making the estimation of regression coefficients unstable and less accurate.

We observe that all the VIF values for the analyzed indicators are below the threshold of 5.00 (

Table 6) and we can conclude that the multicollinearity analysis does not reach critical levels for any of the reflective variables;, thus, it does not create problems in the estimation of the analyzed structural model.

5.3. Hypotheses Testing Results

A very important procedure is bootstrapping, which tests the significance of the relationship coefficients estimated in the research. Bootstrapping contributes to the construction of confidence intervals, estimation of standard errors, significance testing and obtaining

p-values in various types of analyses. In

Table 7,

t-test values and asymptotic significances (

p-values) are calculated to assess the significance of each estimate and to validate or reject research hypotheses. Bootstrapping provides more precise

p-values fitted to the distribution of observed data, not to a theoretical distribution.

Figure 5 reflects the structural model generated after bootstrapping, in which the asymptotic significance (

p-value) values are highlighted on the relationships between the latent variables.

All eight hypotheses were supported based on statistically significant path coefficients (p < 0.05). The t-test provides information about the magnitude of correlation between the latent variables in the structural model. By assessing the significance of t-test, it can be determined whether there is a significant correlation between the latent variables, which indicates the importance and consistency of the relationships between them in the structural model. Thus, the t-test provides a measure of the impact and relevance of the associations between the latent variables, contributing to the understanding of the relationships in the system under study.

The hypotheses are supported and there is statistically significant evidence to suggest that the proposed relationship/effect is statistically valid. The T-statistic allows the significance of coefficients in statistical models to be assessed, indicating whether the observed relationships between variables are real or could be just the result of chance variability. Thus, all eight hypotheses (H1–H2) were validated.

The results of the present research have confirmed all the hypotheses initially formulated. The validation of the hypotheses not only emphasizes the robustness of the proposed model, but also the importance of the relationships identified between the variables studied. The results obtained are in line with recent trends in the fashion industry as an increasing number of consumers prefer to support brands that prioritize sustainability. Firms in the fashion industry should integrate sustainability strategies into their business model not only out of an ethical obligation, but also to meet the growing consumer expectations.

Even if the hypotheses have been validated, there are still significant opportunities for further knowledge on the impact of sustainability on the fashion industry. For future research, we propose to analyze the effectiveness of marketing campaigns promoting sustainability, including the analysis of messages, communication channels, and the impact on sustainability and consumer attitudes towards sustainability in purchasing decisions applied in the fashion industry.

6. Discussions

The results of this research can be used by brands in the fashion industry to enhance their reputation and gain public trust. Investments in technology demonstrate that consumers to track the provenance of materials and production processes, demonstrating a genuine commitment to sustainability. However, it is important to acknowledge that transparency alone may not always translate into consumer trust. Some consumers remain skeptical of greenwashing practices, and without third-party verification or consistent brand behavior, transparency initiatives might be perceived as superficial. Results suggest that educating and raising consumer awareness of sustainability is an effective strategy for fashion brands. Through educational initiatives and transparent communication, brands can create a community of loyal consumers willing to actively support brands that share the same values. Nevertheless, consumer education has its limits. Not all market segments respond equally to educational campaigns; some prioritize price, convenience, or fashion trends over sustainability. In such cases, ethical messaging may be ignored or perceived as elitist.

Collaborations with NGOs and other sustainable brands demonstrate the potential to expand into new markets. Fashion brands could benefit from alliances with like-minded environmental organizations or other industry players to gain recognition and legitimacy with sustainability-conscious consumers. Yet such collaborations can also backfire if seen as opportunistic or if the NGO’s values conflict with certain business practices of the brand. Active involvement of brands in concrete sustainability actions can become a competitive differentiator. By investing in sustainable practices, such as using recycled materials or reducing waste, brands demonstrate their ability to attract consumers who prefer sustainable products, giving them a competitive advantage over traditional brands. Still, implementing these practices often involves high costs, and not all companies can afford to maintain both profitability and strong sustainability commitments—especially in low-cost or fast-fashion segments.

Sustainable marketing campaigns suggest that inform consumers about issues such as water pollution, textile waste and carbon emissions, inspiring them to make more responsible choices. Through marketing strategies that educate and sensitize consumers, fashion brands help raise social awareness of fashion’s impact on the environment and natural resources. Through access to transparent information about the supply chain and sustainable practices, consumers can be motivated to make more ethical choices. As people become more educated about sustainability, they are more likely to reduce over-purchasing and opt for sustainable products, which supports a culture of responsible consumption. By promoting material innovation and recycling practices, brands can support the transition to a circular economy.

This reduces waste and extends the life cycle of products, contributing to a more environmentally aware and responsible society. Brands that integrate sustainability into their communication and products indirectly promote a more balanced and environmentally responsible lifestyle. This encourages the public to adopt behavioral changes in other areas such as reducing waste, using renewable energy or choosing sustainable transport. Brands that invest in consumer education can help build a more engaged and united community around sustainability values. This stimulates positive social activities such as recycling clothes, supporting repair workshops or organizing second-hand fashion fairs. In this way, people become more connected around common causes and act collectively to reduce the negative impact of the fashion industry.

7. Summary of Key Findings

The fashion industry is one of the most dynamic and fluctuating industries in the world [

88]. In the fashion industry, there is excessive consumption of natural resources and enormous use of chemicals during production and dyeing of fibers which harms the environment [

89]. Green marketing involves more than just promoting a product’s or organization’s green attributes or activities. It requires that organizations carefully evaluate the very nature of organization–consumer exchange [

90]. Greenhouse gas emissions from the garment industry constitute a significant part of global carbon emissions due to the energy consumed in the production and transportation of the millions of garments purchased globally annually, all contributing to a complex supply chain [

91]. The fashion industry is carefully analyzed with sustainability in mind as its environmental impact is significant. There is a need for effective and well-targeted strategies that promote sustainability so that consumers are influenced to choose products from companies that are sustainable. Well-run marketing strategies contribute to the transparency of activities and processes, improve the image of companies on the market;, thus, fashion companies gain a positive reputation and gain access to new markets through various collaborations.

Sustainable development has been the focus of business operations for decades, involving social and environmental concerns integrated into business and organizational models [

92]. Sustainability issues have become critical in the fashion industry, particularly with the development of fast fashion and e-commerce, but also through the shift in business model from offline to online [

64,

93,

94,

95]. Public perception can be easily influenced if marketing campaigns are well targeted and the message is relevant. Promoting sustainable activity influences public perception of brands. Consumers can more easily choose brands that operate sustainably and contribute to a responsible economy. Transparency must be emphasized throughout the marketing strategy. Transparency of supply chain stages, activities, and production processes becomes a powerful tool to attract and retain customers.

Fashion products, including textiles, apparel, footwear, and accessories, are manufactured through the intensive use of raw materials, water, and labor, leading to significant environmental challenges arising from the huge waste of materials and energy, deterioration of natural resources, heavy pollution, carbon emissions, and deteriorating working conditions [

96]. By knowing the source of materials, labor conditions, and the environmental impact of production, brands can build a trust relationship with consumers. By conducting transparent marketing, brands not only respond to the public’s growing ethical, demands but also help to differentiate themselves in a saturated market. Fashion brands need to implement marketing strategies that focus on sustainability as it can have a direct impact on brand reputation and credibility.

8. Implications for Practice and Policy

Fashion, defined as an expression widely accepted by a group of people over time has been characterized by several marketing factors such as low predictability, high impulse purchase, shorter life cycle, and high volatility of market demand [

97]. These dynamics underline the need for concrete action not only from brands, but also from NGOs and policymakers. The following implications are structured around these three groups of stakeholders: fashion retailers, NGOs, and decision-makers.

Modern consumers have become increasingly attracted to brands that promote responsible practices as they are aware of the environmental impact. Effectively communicating a commitment to sustainability helps to reinforce the brand’s image as a responsible brand committed to social causes. Commitment to long-term sustainability leads to consumer loyalty and increased brand value.

Companies that embrace innovation in their processes can respond quickly to changing public demands. Fashion companies should prioritize transparency and traceability, implementing tools like blockchain to allow consumers to verify sustainable practices. They should also invest in material innovation and adopt circular economy principles to reduce waste. Moreover, partnerships with NGOs or other ethical brands can enhance credibility and open access to sustainability-conscious markets.

Companies in the fashion industry are highly motivated to explore environmentally friendly materials and sustainable production technologies to meet the demands of the increasingly sustainability-oriented market. Therefore, fashion brands and manufacturers tend to integrate sourcing and distribution channels into the framework of sustainable supply chain management, making joint efforts to improve sustainable fashion practices, not only to achieve commercial benefits, but also to address social welfare and environmental protection [

96].

The public has become increasingly receptive to green and ethical products, and companies that promote their commitment to sustainability can tap into consumer segments that would not normally be interested in their offerings. Sustainability-oriented marketing strategies can, therefore, open access to new markets and growth opportunities. By partnering with other like-minded companies, brands in the fashion industry can gain opportunities for expansion and increased market share.

This led to a decline in mass production in the fashion industry and a change in the structures of fashion supply chains [

98]. Until the 1980s, fashion supply chains were strongly protected by large retail stores against competition from outside markets [

99]. However, these then began to be replaced by buyer-oriented, strategically linked, highly responsive, low-cost, strategically linked, low-cost, strategically responsive supply chains with shorter lead times [

100].

Using marketing can effectively communicate a brand’s commitment to sustainability through concrete actions. Marketing communication must be accompanied by concrete actions to convince the public of the companies’ commitment. Sustainability needs to be demonstrated through hard evidence, not just promises. Brands in the fashion industry need to demonstrate their commitment to sustainability through concrete actions such as initiatives to reduce carbon emissions, use recycled materials or support local communities. NGOs can play a key role in monitoring greenwashing and advocating for transparency. They should also build educational campaigns, collaborate with ethical brands to support certifications, and create platforms for responsible consumption.

So companies that show they are committed to protecting the environment are not just in it for the bottom line. Moreover, companies need to get involved to educate and sensitize consumers in the context of sustainability. Information campaigns and marketing strategies to educate and sensitize consumers by companies in the fashion industry aim to raise awareness of environmental and social issues in the fashion industry and to change consumer behavior. Through sustainability actions fashion companies improve their public image and create a culture of sustainability among consumers. Public authorities should incentivize sustainable practices through tax reductions or subsidies for green innovation. Legislation on supply chain transparency and sustainability labeling could create a framework that rewards genuinely responsible brands. Supporting educational programs in schools about sustainable consumption is also key to shaping long-term behavioral change.

9. Research Contributions and Originality

Consequently, consumers gain moral satisfaction by adapting their purchasing behaviors, reducing waste and extending the life cycle of clothing [

101]. Thus, companies with the ability to adapt to the demands of consumers who choose sustainable products are more likely to succeed in the long run [

102]. Fashion brands aim in their sustainability promotion process to create and strengthen a community of consumers oriented towards a sustainable future. Creating an engaged community is necessary for fashion brands that have embedded sustainability in their process. Communities committed to sustainability are loyal to the companies and help to extend the sustainability message to a wider audience, becoming brand ambassadors. Moreover, fashion companies can collaborate with non-governmental organizations and other brands to promote sustainability values. Collaborations with NGOs give fashion companies credibility with the public and extend their influence. Through collaborations with other brands, more effective solutions to sustainability issues in the fashion industry can be developed, facilitating the sharing of resources and knowledge.

The fashion industry has been accused of taking limited responsibility for its behavior in addressing sustainability issues, such as in the context of the climate change debate [

103] and excessive consumption of natural resources, due to its production and marketing strategies [

103]. The implications of marketing and the strategies employed by brands in the fashion industry are complex. By running an effective marketing program, both public perception and the way brands do business are influenced. Businesses can gain from partnerships with environmental organizations is stakeholder support [

104]. Through collaborations with NGOs, fashion companies connect with relevant causes and can participate in projects with a strong positive social and environmental impact.

Effective marketing strategies applied by fashion brands contribute to building credibility, favorable reputation, access to new markets, and the integration of innovation, thus shaping more responsible and forward-looking industries. Brands need to deliver on their commitments and continue to innovate to attract as many consumers as possible who share the same values, creating an engaged and loyal community.

Originality of research:

This research makes an original contribution by analyzing in an integrated way the relationship between sustainability and marketing strategies in the fashion industry, with a focus on their influence on consumer perceptions. Using structural equation modeling (SEM-PLS), the study provides a robust framework for assessing the impact of sustainability strategies on brand image. The interdisciplinary dimension, which combines mar-keting, sustainability, consumer education and inter-organizational collaboration, differentiates this approach from other research focused on isolated aspects. The study also proposes an innovative strategic perspective, highlighting the link between sustainability and access to new market segments, an area insufficiently explored in the literature.

This research makes an original contribution by analyzing in an integrated way the relationship between sustainability and marketing strategies in the fashion industry, with a focus on their influence on consumer perceptions. By using structural equation modeling (SEM-PLS), the study provides a robust framework for assessing the impact of sustainable strategies on brand image. The interdisciplinary dimension that combines marketing, sustainability, consumer education, and inter-organizational collaboration differentiates this approach from other research focused on isolated issues. The study also proposes an innovative strategic perspective, highlighting the link between sustainability and access to new market segments, an area insufficiently explored in the literature.

10. Limitations and Future Research

While the results obtained provide valuable insights into how sustainable marketing strategies influence consumer perceptions and can support the expansion of fashion brands into new markets, there are some limitations that need to be mentioned.

First of all, the research is based on a quantitative design using structural equation modeling, which, although it allows the analysis of complex relationships between variables, depends on the quality of the data and the validity of the constructs used. The applied sample was geographically and numerically limited, which may restrict the degree of generalizability of the findings across different cultural or economic contexts.

Second, the study is cross-sectional, providing a snapshot of consumer behavior and perceptions without capturing their dynamics over time. Furthermore, the variables used capture only part of the dimensions of sustainability and ethical marketing, not including possible moderating effects or contextual factors such as price, environmental literacy or social influences.

These limitations provide useful directions for future research, which could adopt a longitudinal approach, a diversification of the sample or the integration of mixed methods for a broader and deeper understanding of the phenomenon under study. There are, therefore, important opportunities for future research. Longitudinal studies could explore how consumer perceptions of sustainability evolve over time with the consistency of brand actions. Extending research internationally would also help to identify cultural differences in receptivity to sustainability.

The integration of additional variables, such as the level of environmental education or social influences, could bring more depth to the analysis of consumer behavior. Also, qualitative methods, such as interviews or focus groups, could provide a detailed understanding of the motivations behind sustainable choices.

Last but not least, future research could investigate the concrete impact of collaborations between brands and NGOs or other sustainable entities, thus contributing to more effective and credible marketing strategies.

_Li.png)