CEO Pay Caps, Political Promotion Incentives, and Green Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Publicly Listed Firms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Institutional Background

2.1. Chinese SOEs’ CEOs’ Monetary and Political Promotion Incentives

2.2. Pay Cap Regulation for Chinese SOEs’ CEOs

2.3. Comparison of the Incentives Used in Policies in the Leading Green Economies

3. Hypotheses

3.1. Pay Cap Regulation and Firms’ Green Innovation

3.2. Moderating Analyses

3.2.1. Moderating Effect of CEOs’ Political Connections

3.2.2. Moderating Effect of CEO Age

3.2.3. Moderating Effect of Industry Munificence

4. Method

4.1. Data Sources and Sample

4.2. Measures

4.3. DID Estimation Model

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

5.2. Main Effects

5.3. Moderating Effects

5.4. Supplementary Analysis and Robustness Check

5.4.1. Excluding Firms with No Green Patent Applications

5.4.2. Addressing Confounding Effects

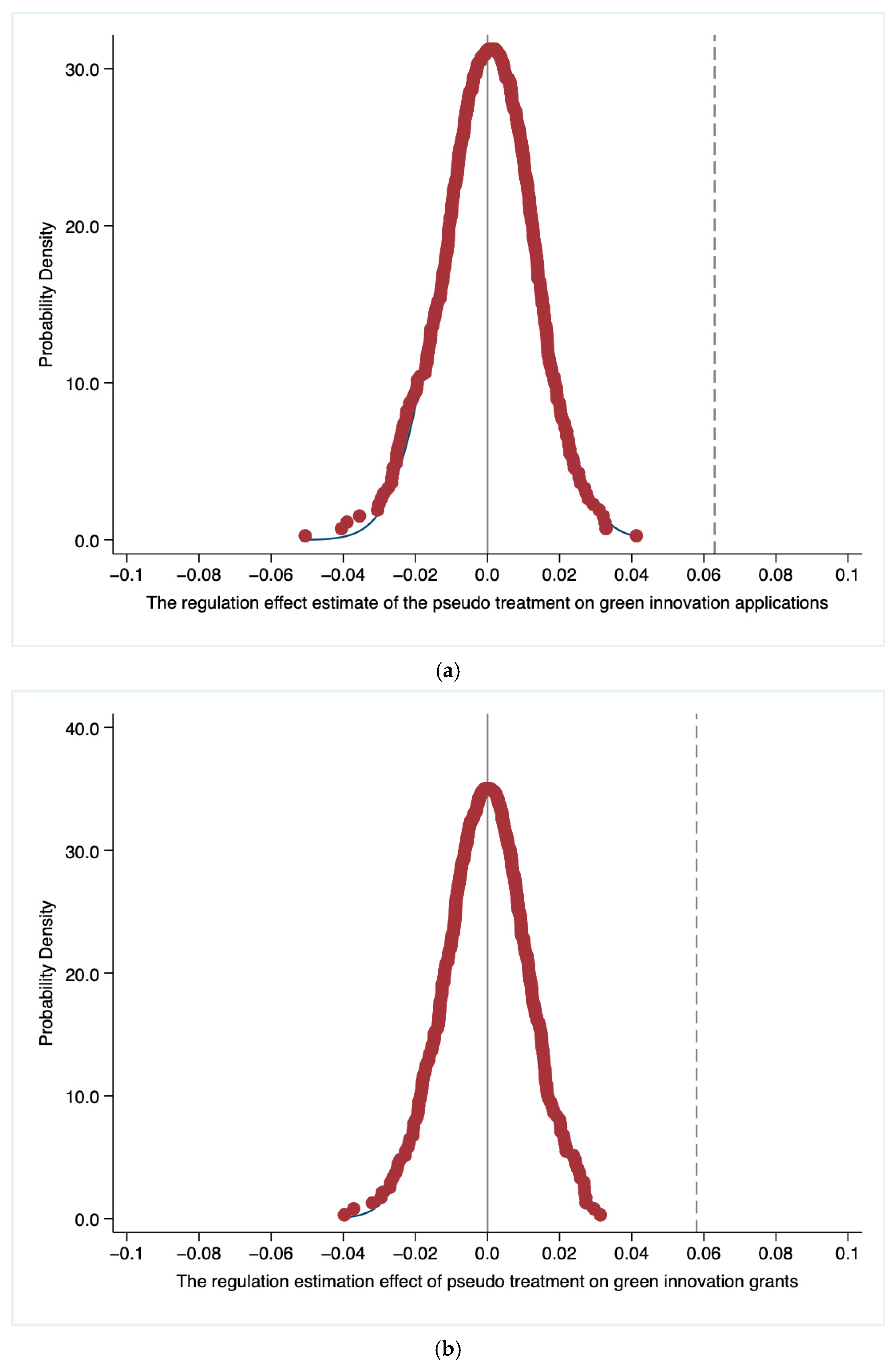

5.4.3. Placebo Test

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- George, G.; Howard-Grenville, J.; Joshi, A.; Tihanyi, L. Understanding and Tackling Societal Grand Challenges through Management Research. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1880–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A. Making Norms to Tackle Global Challenges: The Role of Intergovernmental Organisations. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickert, C.; Muzio, D. What Is the Strategy of Strategy to Tackle Climate Change? J. Manag. Stud. 2025, 62, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavul, S.; Bruton, G.D. Harnessing Innovation for Change: Sustainability and Poverty in Developing Countries. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P.; Stilgoe, J. Responsible Research and Innovation: From Science in Society to Science for Society, with Society. Sci. Public Policy 2012, 39, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilgoe, J.; Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P. Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Scherer, A.G. Responsible Innovation and the Innovation of Responsibility: Governing Sustainable Development in a Globalized World. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Pantzalis, C.; Zhang, Z. Multinationality and the Value of Green Innovation. J. Corp. Finance 2021, 69, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polzin, F.; Sanders, M. How to Finance the Transition to Low-Carbon Energy in Europe? Energy Policy 2020, 147, 111863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, S.; Zhao, J. Demand for Green Finance: Resolving Financing Constraints on Green Innovation in China. Energy Policy 2021, 153, 112255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.W.; Xu, D. Manager or Politician? Effects of CEO Pay on the Performance of State-Controlled Chinese Listed Firms. J. Manag. 2022, 48, 1160–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Lemmon, M.; Pan, X.; Qian, M.; Tian, G. Political Promotion, CEO Incentives, and the Relationship Between Pay and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 2947–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R.; Murphy, K.J. Optimal Incentive Contracts in the Presence of Career Concerns: Theory and Evidence. J. Polit. Econ. 1992, 100, 468–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceweekly. The Pay Cap Regulation for Top Executives of the State-Owned Enterprises Is About to Be Issued. The Salary Design Is Said to Only Consider “Lei Feng”. 4 May 2015. Available online: https://www.ceweekly.cn/mag/2015/0504/110281.html (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Hung, M.; Wong, T.J.; Zhang, T. Political Considerations in the Decision of Chinese SOEs to List in Hong Kong. J. Account. Econ. 2012, 53, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ederhof, M. Incentive Compensation and Promotion-Based Incentives of Mid-Level Managers: Evidence from a Multinational Corporation. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayle, G.-L.; Golan, L.; Miller, R.A. Promotion, Turnover, and Compensation in the Executive Labor Market. Econometrica 2015, 83, 2293–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Li, Z.; Su, X.; Sun, Z. Rent-Seeking Incentives, Corporate Political Connections, and the Control Structure of Private Firms: Chinese Evidence. J. Corp. Finance 2011, 17, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wong, C.W.Y.; Miao, X. Political Connection, Political Promotion and Corporate Environmental Information Disclosure in China. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2021, 16, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, P. Political Connections, Government Subsidies and Firm Financial Performance: Evidence from Renewable Energy Manufacturing in China. Renew. Energy 2014, 63, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickley, J.A. Empirical Research on CEO Turnover and Firm-Performance: A Discussion. J. Account. Econ. 2003, 36, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Outside Options and CEO Turnover: The Network Effect. J. Corp. Finance 2014, 28, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarius, E.E.; Stevens, C.E.; Tenhiälä, A. Tether or Stepping Stone? The Relationship between Perceived External Reputation and Collective Voluntary Turnover Rates. Organ. Stud. 2017, 38, 1665–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, O.C.; Kirby, S.L.; Chadwick, K. The Impact of Racial and Gender Diversity in Management on Financial Performance: How Participative Strategy Making Features Can Unleash a Diversity Advantage. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2571–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as the Mother of ‘Green’ Inventions: Institutional Pressures and Environmental Innovations. Strat. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, K.; Zhou, K.Z. How Political Ties and Green Innovation Co-Evolve in China: Alignment with Institutional Development and Environmental Pollution. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 186, 739–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-de la Hiz, D.I.; Hurtado-Torres, N.; Bermúdez-Edo, M. The Heterogeneity of Levels of Green Innovation by Firms in International Contexts: A Study Based on the Home-Country Institutional Profile. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 508–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, B. Managerial Incentive Problems: A Dynamic Perspective. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1999, 66, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F. Agency Problems and the Theory of the Firm. J. Polit. Econ. 1980, 88, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J. CEO Career Concerns and Investment Efficiency: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2015, 24, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, T.; Hong, Y.; McMillan, J.; Naughton, B. China’s Evolving Managerial Labor Market. J. Polit. Econ. 1995, 103, 873–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, L.-A. Political Turnover and Economic Performance: The Incentive Role of Personnel Control in China. J. Public Econ. 2005, 89, 1743–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Lu, J.W.; Gu, Q. Organizational Forms and Multi-Population Dynamics: Economic Transition in China. Adm. Sci. Q. 2014, 59, 517–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.-H.; Liang, H.; Matos, P. Leviathan Inc. and Corporate Environmental Engagement. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 7719–7758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Daily. What Is a Reasonable Income Gap? The Pay of Top Executives in State-Owned Enterprises Has Exceeded That of Their Employees by 13 Times. 29 August 2014. Available online: https://cn.chinadaily.com.cn/2014-08/29/content_18511475.htm (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Wang, D.; Luo, X.R. Retire in Peace: Officials’ Political Incentives and Corporate Diversification in China. Adm. Sci. Q. 2019, 64, 773–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obobisa, E.S.; Ahakwa, I. Stimulating the Adoption of Green Technology Innovation, Clean Energy Resources, Green Finance, and Environmental Taxes: The Way to Achieve Net Zero CO2 Emissions in Europe? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 205, 123489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemsen, E. The Hidden Perils of Career Concerns in R&D Organizations. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 863–877. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, G.P. Incentive Contracts and Performance Measurement. J. Polit. Econ. 1992, 100, 598–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Scherer, A.G.; Stahl, G.K.; Hawn, O. Grand Societal Challenges and Responsible Innovation. J. Manag. Stud. 2022, 59, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.-Y.; Sun, P. Closing the Revolving Door: What If Board Political Connections Are Permanently Broken? J. Manag. 2024, 50, 2534–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M.; Masulis, R.W.; McConnell, J.J. Political Connections and Corporate Bailouts. J. Finance 2006, 61, 2597–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, E.; Rocholl, J.; So, J. Politically Connected Boards of Directors and the Allocation of Procurement Contracts. Rev. Finance 2013, 17, 1617–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Derashid, C.; Zhang, H. Public Policy, Political Connections, and Effective Tax Rates: Longitudinal Evidence from Malaysia. J. Account. Public Policy 2006, 25, 574–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Simon, H.A. Organizations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Belenzon, S.; Shamshur, A.; Zarutskie, R. CEO’s Age and the Performance of Closely Held Firms. Strat. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 917–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Low, A.; Makhija, A.K. Career Concerns and the Busy Life of the Young CEO. J. Corp. Finance 2017, 47, 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, L. Executive Turnover in China’s State-Owned Enterprises: Government-Oriented or Market-Oriented? China J. Account. Res. 2018, 11, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.K.; Mezias, J.M. Before and after the Technology Sector Crash: The Effect of Environmental Munificence on Stock Market Response to Alliances of E-commerce Firms. Strat. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 987–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starbuck, W.H. Organizations and Their Environments. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, N.; Blum, T.C.; Roman, P.M. Presence of Drug Screening and Employee Assistance Programs: Exclusive and Inclusive Human Resource Management Practices. J. Organ. Behav. 1994, 15, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, G.; Winroth, M. Introducing Environmental Concern in Manufacturing Strategies: Implications for the Decision Criteria. Manag. Res. Rev. 2010, 33, 877–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Environmental Performance and Executive Compensation: An Integrated Agency-Institutional Perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunapatarawong, R.; Martínez-Ros, E. Towards Green Growth: How Does Green Innovation Affect Employment? Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1218–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.U.; Kraus, S.; Shah, S.A.; Khanin, D.; Mahto, R.V. Analyzing the Relationship between Green Innovation and Environmental Performance in Large Manufacturing Firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecere, G.; Corrocher, N.; Gossart, C.; Ozman, M. Technological Pervasiveness and Variety of Innovators in Green ICT: A Patent-Based Analysis. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1827–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.; Ke, Y.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, Y. CEO Foreign Experience and Green Innovation: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 182, 535–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, R.J. Making the Most of Where You Are: Geography, Networks, and Innovation in Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Phelps, C.; Steensma, H.K. Learning from What Others Have Learned from You: The Effects of Knowledge Spillovers on Originating Firms. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Singh, K.; Mitchell, W. Buffering and Enabling: The Impact of Interlocking Political Ties on Firm Survival and Sales Growth. Strat. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1615–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keats, B.W. The Vertical Construct Validity of Business Economic Performance Measures. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1988, 24, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tang, Y. CEO Hubris and Firm Risk Taking in China: The Moderating Role of Managerial Discretion. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Does Product Market Competition Foster Corporate Social Responsibility? Evidence from Trade Liberalization. Strat. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1469–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, A.; Athey, S.; Imbens, G.W.; Wooldridge, J.M. When Should You Adjust Standard Errors for Clustering? Q. J. Econ. 2023, 138, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.B. Simple Formulas for Standard Errors That Cluster by Both Firm and Time. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 99, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T.P. Modern Regression Methods; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-470-08186-0. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, V.V.; Baghai, R.P.; Subramanian, K.V. Wrongful Discharge Laws and Innovation. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2014, 27, 301–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, M.D.; Schneider, C.; Žaldokas, A. Credit Supply and Corporate Innovation. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 109, 835–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-L.; Tong, T.W.; Zhang, Y.; He, W. Constructing a Chinese Patent Database of Listed Firms in China: Descriptions, Lessons, and Insights. J. Econ. Manag. Strat. 2018, 27, 579–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.; Duflo, E.; Mullainathan, S. How Much Should We Trust Differences-In-Differences Estimates? Q. J. Econ. 2004, 119, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Wang, F.; Usman, M.; Ali Gull, A.; Uz Zaman, Q. Female CEOs and Green Innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 157, 113515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yan, J. CEO Hometown Identity and Firm Green Innovation. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 756–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C. Upper Echelons Theory: An Update. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossland, C.; Hambrick, D.C. Differences in Managerial Discretion across Countries: How Nation-Level Institutions Affect the Degree to Which CEOs Matter. Strat. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 797–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W. Towards an Attention-based View of the Firm. Strat. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baginski, S.P.; Campbell, J.L.; Hinson, L.A.; Koo, D.S. Do Career Concerns Affect the Delay of Bad News Disclosure? Account. Rev. 2018, 93, 61–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, N.; Boone, A.; Croci, E.; Signori, A. Reductions in CEO Career Horizons and Corporate Policies. J. Corp. Finance 2021, 66, 101862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wangrow, D.B.; Barker, V.L. Career Concerns of Young and Old CEOs: Their Effect on R&D Spending in the Software Industry. Long Range Plann. 2024, 57, 102438. [Google Scholar]

- Kawai, N.; Strange, R.; Zucchella, A. Stakeholder Pressures, EMS Implementation, and Green Innovation in MNC Overseas Subsidiaries. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) GI_apply (log) | 0.334 | 0.777 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||

| (2) GI_grant (log) | 0.354 | 0.738 | 0.701 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||

| (3) Regulation | 0.175 | 0.380 | 0.063 | 0.069 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| (4) ROA | 0.041 | 0.058 | 0.049 | 0.006 | −0.083 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| (5) Leverage | 0.419 | 0.200 | 0.120 | 0.151 | 0.147 | −0.351 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| (6) Firm listing age | 2.118 | 0.792 | −0.018 | −0.021 | 0.340 | −0.180 | 0.314 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (7) Board independence | 0.374 | 0.062 | 0.033 | 0.039 | −0.011 | −0.008 | −0.002 | −0.039 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (8) Firm size | 22.041 | 1.220 | 0.259 | 0.300 | 0.273 | 0.019 | 0.441 | 0.310 | 0.047 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (9) Board size | 2.265 | 0.165 | 0.061 | 0.057 | 0.080 | 0.026 | 0.094 | 0.058 | −0.385 | 0.170 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (10) Largest investor | 3.491 | 0.441 | −0.008 | 0.017 | 0.081 | 0.094 | 0.050 | −0.117 | 0.055 | 0.150 | −0.021 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (11) R&D intensity | 2.762 | 3.039 | 0.156 | 0.160 | 0.057 | 0.070 | −0.245 | −0.160 | 0.047 | −0.049 | −0.069 | −0.119 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (12) CEO tenure | 4.529 | 3.193 | 0.047 | 0.052 | −0.032 | 0.034 | −0.035 | 0.119 | 0.040 | 0.047 | 0.002 | −0.100 | 0.105 | 1.000 | |||||

| (13) CEO duality | 0.053 | 0.224 | −0.009 | −0.022 | −0.040 | −0.015 | −0.019 | −0.134 | −0.011 | −0.051 | −0.038 | −0.002 | 0.002 | −0.153 | 1.000 | ||||

| (14) CEO gender | 0.055 | 0.228 | −0.006 | −0.010 | −0.036 | 0.001 | −0.030 | −0.041 | 0.046 | −0.020 | −0.091 | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.021 | −0.001 | 1.000 | |||

| (15) CEO_young | 0.967 | 0.180 | −0.002 | 0.006 | 0.045 | −0.035 | 0.019 | 0.036 | −0.012 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.028 | −0.033 | −0.081 | −0.016 | 0.003 | 1.000 | ||

| (16) Munificence | 0.215 | 0.056 | 0.005 | 0.003 | −0.107 | −0.020 | 0.122 | 0.029 | −0.009 | 0.049 | 0.001 | 0.064 | −0.066 | −0.048 | 0.015 | −0.006 | 0.037 | 1.000 | |

| (17) Political connections | 0.157 | 0.364 | 0.072 | 0.061 | −0.071 | 0.070 | −0.048 | −0.123 | 0.017 | −0.013 | −0.031 | −0.024 | 0.044 | 0.144 | 0.022 | 0.059 | −0.093 | −0.004 | 1.000 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | GI_apply (log) | GI_apply (log) | GI_apply (log) | GI_grant (log) | GI_grant (log) | GI_grant (log) |

| Regulation (H1) | 0.047 * | 0.063 ** | 0.030 * | 0.058 *** | ||

| (0.027) | (0.028) | (0.015) | (0.017) | |||

| Pre_4 | 0.003 | −0.014 | ||||

| (0.036) | (0.035) | |||||

| Pre_3 | 0.023 | −0.032 | ||||

| (0.034) | (0.046) | |||||

| Pre_2 | 0.056 | −0.013 | ||||

| (0.046) | (0.035) | |||||

| Pre_1 | 0.047 | −0.003 | ||||

| (0.030) | (0.046) | |||||

| Current | 0.109 *** | 0.055 | ||||

| (0.036) | (0.037) | |||||

| Post_1 | 0.061 * | 0.021 | ||||

| (0.031) | (0.043) | |||||

| Post_2 | 0.074 * | 0.025 | ||||

| (0.044) | (0.046) | |||||

| Post_3 | 0.163 *** | 0.048 | ||||

| (0.033) | (0.045) | |||||

| Post_4 | 0.035 | 0.085 ** | ||||

| (0.034) | (0.042) | |||||

| ROA | 0.268 ** | 0.274 ** | −0.197 * | −0.208 * | ||

| (0.115) | (0.115) | (0.111) | (0.110) | |||

| Leverage | 0.172 *** | 0.166 *** | 0.053 | 0.055 | ||

| (0.034) | (0.034) | (0.043) | (0.043) | |||

| Firm listing age | −0.014 | −0.013 | 0.038 ** | 0.041 *** | ||

| (0.023) | (0.026) | (0.016) | (0.014) | |||

| Board independence | 0.222 ** | 0.230 *** | 0.148 * | 0.147 * | ||

| (0.085) | (0.084) | (0.074) | (0.076) | |||

| Firm size | 0.039 *** | 0.039 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.038 *** | ||

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.013) | (0.012) | |||

| Board size | 0.108 ** | 0.110 *** | 0.052 | 0.052 | ||

| (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.042) | (0.041) | |||

| Largest investor | −0.094 *** | −0.093 *** | −0.058 *** | −0.058 *** | ||

| (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.019) | (0.019) | |||

| R&D intensity | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.009 *** | 0.009 *** | ||

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||

| CEO tenure | 0.004 ** | 0.004 ** | 0.004 * | 0.004 * | ||

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |||

| CEO duality | 0.042 *** | 0.041 ** | 0.006 | 0.006 | ||

| (0.015) | (0.016) | (0.012) | (0.012) | |||

| CEO gender | −0.008 | −0.010 | 0.039 ** | 0.039 ** | ||

| (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.019) | (0.019) | |||

| Constant | 0.160 *** | −0.734 *** | −0.744 *** | 0.137 *** | −0.713 ** | −0.722 ** |

| (0.004) | (0.197) | (0.200) | (0.003) | (0.300) | (0.298) | |

| R2 | 0.095 | 0.100 | 0.102 | 0.073 | 0.079 | 0.079 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | GI_apply (log) | GI_apply (log) | GI_apply (log) | GI_grant (log) | GI_grant (log) | GI_grant (log) |

| Regulation | 0.050 ** | 0.321 ** | 0.238 *** | 0.048 *** | 0.381 *** | 0.147 *** |

| (0.024) | (0.126) | (0.060) | (0.017) | (0.109) | (0.046) | |

| Political connections | −0.014 | −0.043 ** | ||||

| (0.033) | (0.020) | |||||

| Regulation × political connections (H2) | 0.193 ** | 0.147 *** | ||||

| (0.080) | (0.048) | |||||

| CEO_young | 0.022 | 0.070 ** | ||||

| (0.029) | (0.027) | |||||

| Regulation × CEO_young (H3a) | −0.263 ** | −0.319 *** | ||||

| (0.115) | (0.103) | |||||

| Munificence | −0.442 *** | −0.566 *** | ||||

| (0.117) | (0.100) | |||||

| Regulation × munificence (H3b) | −0.865 *** | −0.445 * | ||||

| (0.216) | (0.227) | |||||

| ROA | 0.272 ** | 0.270 ** | 0.279 ** | −0.192 * | −0.186 | −0.186 * |

| (0.115) | (0.115) | (0.111) | (0.110) | (0.112) | (0.109) | |

| Leverage | 0.175 *** | 0.175 *** | 0.172 *** | 0.056 | 0.044 | 0.053 |

| (0.034) | (0.034) | (0.034) | (0.044) | (0.043) | (0.042) | |

| Firm listing age | −0.015 | −0.013 | −0.013 | 0.036 ** | 0.038 ** | 0.039 ** |

| (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.015) | (0.016) | (0.015) | |

| Board independence | 0.222 ** | 0.221 ** | 0.225 ** | 0.146 * | 0.155 ** | 0.149 * |

| (0.084) | (0.085) | (0.085) | (0.074) | (0.076) | (0.074) | |

| Firm size | 0.037 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.044 *** | 0.037 *** | 0.041 *** | 0.043 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.013) | |

| Board size | 0.108 ** | 0.110 *** | 0.103 ** | 0.051 | 0.053 | 0.048 |

| (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.042) | (0.042) | |

| Largest investor | −0.095 *** | −0.094 *** | −0.086 *** | −0.058 *** | −0.052 ** | −0.050 ** |

| (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.019) | (0.021) | (0.019) | |

| R&D intensity | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.009 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.010 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| CEO tenure | 0.003 ** | 0.004 ** | 0.004 *** | 0.004 * | 0.005 ** | 0.004 ** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| CEO duality | 0.042 *** | 0.043 *** | 0.043 *** | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.006 |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.012) | (0.013) | (0.012) | |

| CEO gender | −0.012 | −0.010 | −0.008 | 0.034 * | 0.034 * | 0.042 ** |

| (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.019) | (0.020) | (0.019) | |

| Constant | −0.680 *** | −0.743 *** | −0.765 *** | −0.684 ** | −0.875 *** | −0.731 ** |

| (0.197) | (0.199) | (0.197) | (0.296) | (0.290) | (0.297) | |

| R2 | 0.101 | 0.101 | 0.102 | 0.080 | 0.082 | 0.081 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | GI_apply (log) | GI_apply (log) | GI_apply (log) | GI_apply (log) | GI_grant (log) | GI_grant (log) | GI_grant (log) | GI_grant (log) |

| Regulation | 0.113 ** | 0.089 ** | 0.554 ** | 0.311 ** | 0.094 *** | 0.080 *** | 0.323 *** | 0.182 |

| (0.046) | (0.040) | (0.230) | (0.150) | (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.119) | (0.118) | |

| Political connections | 0.029 | 0.026 | ||||||

| (0.066) | (0.047) | |||||||

| Regulation × political connections (H2) | 0.380 ** | 0.170 ** | ||||||

| (0.145) | (0.070) | |||||||

| CEO_young | 0.030 | 0.139 *** | ||||||

| (0.056) | (0.051) | |||||||

| Regulation × CEO_young (H3a) | −0.448 ** | −0.233 * | ||||||

| (0.210) | (0.119) | |||||||

| Munificence | −1.186 ** | −1.625 *** | ||||||

| (0.492) | (0.368) | |||||||

| Regulation × munificence (H3b) | −0.999 | −0.466 | ||||||

| (0.624) | (0.562) | |||||||

| ROA | 0.794 *** | 0.787 *** | 0.798 *** | 0.781 *** | −0.144 | −0.141 | −0.126 | −0.163 |

| (0.236) | (0.232) | (0.236) | (0.236) | (0.244) | (0.245) | (0.243) | (0.241) | |

| Leverage | 0.393 *** | 0.396 *** | 0.398 *** | 0.374 *** | 0.092 | 0.094 | 0.093 | 0.070 |

| (0.077) | (0.078) | (0.076) | (0.079) | (0.080) | (0.079) | (0.081) | (0.080) | |

| Firm listing age | −0.075 ** | −0.073 ** | −0.071 * | −0.073 ** | −0.014 | −0.013 | −0.012 | −0.011 |

| (0.036) | (0.035) | (0.035) | (0.036) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | |

| Board independence | 0.301 * | 0.312 * | 0.299 * | 0.306 * | 0.251 * | 0.261 * | 0.257 * | 0.259 * |

| (0.175) | (0.168) | (0.174) | (0.175) | (0.138) | (0.135) | (0.138) | (0.136) | |

| Firm size | 0.116 *** | 0.109 *** | 0.114 *** | 0.127 *** | 0.145 *** | 0.142 *** | 0.146 *** | 0.158 *** |

| (0.022) | (0.021) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.028) | (0.029) | (0.028) | (0.028) | |

| Board size | 0.138 * | 0.148 ** | 0.142 * | 0.139 * | 0.010 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.017 |

| (0.073) | (0.072) | (0.072) | (0.076) | (0.074) | (0.072) | (0.074) | (0.074) | |

| Largest investor | −0.208 *** | −0.215 *** | −0.207 *** | −0.203 *** | −0.077 * | −0.080 * | −0.075 * | −0.070 |

| (0.037) | (0.036) | (0.037) | (0.038) | (0.044) | (0.043) | (0.044) | (0.045) | |

| R&D intensity | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.013 *** | 0.013 *** | 0.013 *** | 0.013 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| CEO tenure | 0.007 ** | 0.005 * | 0.006 ** | 0.008 *** | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| CEO duality | 0.055 | 0.058 | 0.057 | 0.058 * | −0.021 | −0.023 | −0.018 | −0.017 |

| (0.035) | (0.035) | (0.035) | (0.034) | (0.024) | (0.023) | (0.025) | (0.025) | |

| CEO gender | −0.054 | −0.051 | −0.055 | −0.044 | 0.132 ** | 0.133 ** | 0.129 ** | 0.144 *** |

| (0.065) | (0.064) | (0.065) | (0.065) | (0.050) | (0.051) | (0.050) | (0.048) | |

| Constant | −1.978 *** | −1.832 *** | −1.988 *** | −1.969 *** | −2.741 *** | −2.679 *** | −2.919 *** | −2.700 *** |

| (0.590) | (0.568) | (0.578) | (0.610) | (0.645) | (0.640) | (0.629) | (0.632) | |

| R2 | 0.174 | 0.176 | 0.175 | 0.176 | 0.137 | 0.138 | 0.138 | 0.141 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | GI_apply (log) | GI_apply (log) | GI_apply (log) | GI_apply (log) | GI_grant (log) | GI_grant (log) | GI_grant (log) | GI_grant (log) |

| Regulation | 0.063 ** | 0.050 ** | 0.321 ** | 0.238 *** | 0.058 *** | 0.048 *** | 0.150 | 0.147 *** |

| (0.029) | (0.024) | (0.126) | (0.059) | (0.017) | (0.016) | (0.104) | (0.046) | |

| Low carbon | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.046 | 0.039 | −0.015 | −0.016 | −0.017 | −0.025 |

| (0.036) | (0.036) | (0.037) | (0.035) | (0.061) | (0.061) | (0.061) | (0.061) | |

| Trading | −0.006 | −0.009 | −0.009 | −0.008 | −0.013 | −0.015 | −0.015 | −0.015 |

| (0.030) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.030) | (0.035) | (0.035) | (0.034) | (0.034) | |

| Political connections | −0.014 | −0.043 ** | ||||||

| (0.033) | (0.020) | |||||||

| Regulation × political connections (H2) | 0.193 ** | 0.148 *** | ||||||

| (0.080) | (0.049) | |||||||

| CEO_young | 0.022 | 0.077 *** | ||||||

| (0.029) | (0.027) | |||||||

| Regulation × CEO_young (H3a) | −0.263 ** | −0.095 | ||||||

| (0.115) | (0.103) | |||||||

| Munificence | −0.437 *** | −0.570 *** | ||||||

| (0.117) | (0.102) | |||||||

| Regulation × munificence (H3b) | −0.864 *** | −0.445 * | ||||||

| (0.215) | (0.228) | |||||||

| ROA | 0.270 ** | 0.273 ** | 0.272 ** | 0.280 ** | −0.198 * | −0.192 * | −0.190 * | −0.187 * |

| (0.115) | (0.115) | (0.115) | (0.111) | (0.111) | (0.111) | (0.112) | (0.109) | |

| Leverage | 0.173 *** | 0.177 *** | 0.176 *** | 0.173 *** | 0.053 | 0.055 | 0.054 | 0.053 |

| (0.034) | (0.034) | (0.034) | (0.034) | (0.043) | (0.043) | (0.043) | (0.042) | |

| Firm listing age | −0.013 | −0.015 | −0.012 | −0.013 | 0.038 ** | 0.036 ** | 0.038 ** | 0.040 *** |

| (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | |

| Board independence | 0.219 ** | 0.219 ** | 0.217 ** | 0.222 ** | 0.148 * | 0.147 * | 0.152 ** | 0.151 ** |

| (0.085) | (0.084) | (0.085) | (0.085) | (0.075) | (0.074) | (0.073) | (0.074) | |

| Firm size | 0.039 *** | 0.037 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.044 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.037 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.043 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.013) | |

| Board size | 0.109 *** | 0.109 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.104 ** | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.055 | 0.049 |

| (0.040) | (0.040) | (0.040) | (0.040) | (0.042) | (0.041) | (0.042) | (0.042) | |

| Largest investor | −0.094 *** | −0.095 *** | −0.094 *** | −0.087 *** | −0.058 *** | −0.058 *** | −0.059 *** | −0.050 ** |

| (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.019) | |

| R&D intensity | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.009 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.010 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| CEO tenure | 0.004 ** | 0.003 ** | 0.004 ** | 0.004 *** | 0.004 * | 0.004 * | 0.004 ** | 0.004 ** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| CEO duality | 0.042 *** | 0.042 *** | 0.043 *** | 0.043 *** | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | |

| CEO gender | −0.009 | −0.013 | −0.011 | −0.008 | 0.039 ** | 0.034 * | 0.036 * | 0.042 ** |

| (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.018) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.019) | |

| Constant | −0.764 *** | −0.713 *** | −0.771 *** | −0.791 *** | −0.709 ** | −0.683 ** | −0.797 *** | −0.721 ** |

| (0.190) | (0.190) | (0.193) | (0.191) | (0.295) | (0.292) | (0.287) | (0.293) | |

| R2 | 0.100 | 0.101 | 0.101 | 0.102 | 0.079 | 0.080 | 0.079 | 0.081 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shao, Q.; Zhao, X.; Chen, S.; Zhao, J. CEO Pay Caps, Political Promotion Incentives, and Green Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Publicly Listed Firms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125504

Shao Q, Zhao X, Chen S, Zhao J. CEO Pay Caps, Political Promotion Incentives, and Green Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Publicly Listed Firms. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125504

Chicago/Turabian StyleShao, Qiuyue, Xiaoping Zhao, Shouming Chen, and Jing Zhao. 2025. "CEO Pay Caps, Political Promotion Incentives, and Green Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Publicly Listed Firms" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125504

APA StyleShao, Q., Zhao, X., Chen, S., & Zhao, J. (2025). CEO Pay Caps, Political Promotion Incentives, and Green Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Publicly Listed Firms. Sustainability, 17(12), 5504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125504