Abstract

Green leadership is often praised for promoting sustainability, while hospitals in reactive or resource-constrained contexts lack the infrastructure to support leadership-led environmental change, indicating that leadership without operational capacity offers little impact. Moreover, the inconsistencies between green human resource practices and environmental performance suggest that green leadership might lead to symbolic gestures rather than real improvements without a robust environmental culture or internal accountability systems. Amid intensifying environmental regulations and sustainability mandates in healthcare, this study investigates how green transformational leadership addresses the contradiction between hospitals’ resource-intensive operations and environmental accountability. Drawing on Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT), the research highlights policy-driven imperatives for hospitals to build adaptive leadership models that meet sustainability goals. Using data from 312 junior doctors and nurses in private hospitals, analyzed via Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), the study identifies green attitude, green empowerment, and green self-efficacy as key mediators in enhancing environmental performance. Contributions of this study include (1) applying DCT to healthcare sustainability, (2) integrating psychological drivers into leadership–performance models, and (3) emphasizing nurses’ pivotal roles. The results of the study indicate that leaders who prioritize sustainability inspire staff to adopt eco-friendly practices, aligning with SDG 3, i.e., good health and well-being; SDG 12, i.e., responsible consumption and production; and SDG 7, i.e., affordable and clean energy. The findings provide actionable insights for hospital administrators and policymakers striving for environmentally accountable healthcare delivery.

1. Introduction

Manioudis and Meramveliotakis [1] argued that the recent health and economic crises occurring simultaneously are unlike anything we have seen since World War II. Most economists and decision-makers agree on this. We believe that these challenging times are a strong reminder that we need to rethink and give more importance to sustainable development—not just as an idea but also as a way to understand and address current problems.

Green leaders with inspiring visions to drive their followers can facilitate completion of tasks to protect the environment [2,3]. These leaders can serve as role models ‘by practicing green.’ Green transformational leaders are healthy influencers of environmental sustainability, and this is an under-examined area that needs examination. Al-Ghazali et al. [4] found that transformational leaders positively contribute to green creativity. Further, Arici and Uysal [5] found green transformational leadership that promotes green mindfulness, self-efficacy, and organizational performance. Nisar et al. [6] found a positive and significant impact of green transformational leaders on the green performance of a sample of 200 manufacturing organizations. However, not only manufacturing organizations are responsible for environmental degradation, but service organizations [7,8], like hospitals, are also responsible. Hasan et al. [9] examined how green transformational leadership (GL) influences environmental performance (EP) and suggested that besides having a positive relationship, there is a need to deeply examine this relationship further by incorporating other variables into the original relationship. They suggested considering variables like nurses’ green attitude (GA), green self-efficacy (GS), and green empowerment (GE) as having a direct or indirect impact on the environmental performance of the organization [10]. This calls for an examination that focuses on the perceptions of the internal stakeholders, such as employees who work in the hospitals, about the role of green leaders in impacting environmental performance. Environmental performance is about how much an organization is concerned about protecting the environment [11].

However, strong green transformational leadership alone is not enough to guarantee good environmental performance. Organizations must also have effective systems and processes in place to manage their environmental impacts. Additionally, the support and participation of employees, suppliers, and other stakeholders are crucial to achieving good environmental performance.

Hospitals add significantly to environmental pollution through their extensive energy consumption, waste generation, and use of hazardous materials [11]. The presence of green leadership can mitigate these negative impacts [9]. Resource scarcity for hospitals can also be addressed through green transformational leadership. Further, it is noted that environmental degradation directly affects public health outcomes [12]. As healthcare providers, hospitals are responsible for treating illnesses and protecting the environment from damage [9,11]. Hospitals with green transformational leadership that prioritize green initiatives can reduce pollution-related health risks and protect the environment [11]. Finally, valuable insights can be gained by analyzing the impact of GL on EP in healthcare organizations that promote sustainability and improve environmental outcomes. By identifying the critical factors contributing to the effectiveness of green transformational leadership, researchers and practitioners can develop effective strategies and interventions that are more likely to succeed in promoting sustainable practices and outcomes.

Literature on green transformational leadership in hospitals and the environmental performance of these entities is scarce. Green leaders have the potential to shape employees’ green behaviors to improve environmental performance. However, the lack of empirical evidence indicates a need to uncover the underlying mechanisms of better environmental performance [13]. Green attitude, the mindset and disposition of people working in hospitals towards environmental sustainability, can be developed by green transformational leaders. A positive green attitude can lead to more proactive behavior in adopting and supporting green practices. Moreover, the employees remain incapable without adequate empowerment. Empowering employees to take action toward sustainability is crucial. Green empowerment refers to providing staff with the necessary resources, authority, and motivation, enabling them to contribute effectively to the hospital’s green initiatives. Moreover, green self-efficacy measures the confidence of hospital staff in their ability to perform green tasks successfully. Higher green self-efficacy can lead to more consistent and effective implementation of green practices.

Existing literature has focused on examining the relationship of green transformational leadership in small and medium-sized enterprises [13], manufacturing organizations [14], and other sectors [15]. However, there is space to examine its role in the healthcare sector. Moreover, the evidence for the mechanisms that may enhance the basic relationship is also missing from the literature and needs in-depth investigation. Hospitals cannot adopt green practices unless employees’ attitudes, empowerment, and self-efficacy are considered. Therefore, the role of green leaders is critical. Moreover, it is important to examine the employees’ perceptions of environmental problems and their solutions to implement the environmental strategy effectively. Undoubtedly, an organization’s green initiatives cannot be completed without employees’ actions for environmental sustainability [12]. The behaviors can be shaped by developing their attitudes, empowerment, and self-efficacy toward practicing green, which is not part of formal job descriptions. However, the selected behaviors can ensure the pro-environmental success of any organization.

Exploring the influence of green transformational leadership on environmental performance from the perspective of dynamic capability theory is a significant field of study. This approach facilitates understanding how organizations can effectively adjust and react to evolving environmental and social circumstances. Dynamic capability theory, initially introduced by Teece, Pisano, and Shuen [16], highlights an organization’s capacity to enhance and renew its competencies to respond to changes in the external environment. Further, this theory examines how leaders effectively cultivate organizational competencies for enhanced environmental performance.

Three significant contributions are evident in this study. Firstly, it explores the relationship between green transformational leadership and hospital environmental performance, which has rarely been researched extensively. Secondly, it examines the mediating effects of employees’ green environmental attitude, empowerment, and self-efficacy. These factors are important in understanding the relationship between GL and EP in hospitals. Green attitude depicts the individuals’ beliefs, values, and perceptions towards environmental concerns and issues [17], while green self-efficacy is the belief in one’s own capacity to adopt environmental sustainability. Lastly, green empowerment equips employees with the necessary resources and support for effective, sustainable behavior engagement.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Dynamic Capability Theory (DCT) as an Underpinning Theory

Manioudis and Meramveliotakis [1] emphasized the development of a theoretical framework to contextualize, develop, and integrate the multiple, diverse, and middle-range contemporary strands in development studies to enrich sustainable development. Therefore, it is important to examine how organizations can adapt and respond to changing environmental and societal conditions and develop and leverage capabilities to improve their environmental performance over time [18].

The dynamic capabilities of an organization refer to exploiting the organization’s existing resources and competencies to develop new capabilities. Dynamic capability theory (DCT) provides strong foundations for the organization’s internal sustainability drive and performance [19]. Adoption of change for sustainability at the right time helps firms not only maintain but strengthen their environmental performance, and also increases employees’ responsibilities and involvement in solving environmental problems [19].

DCT provides foundations to understand how green leadership can foster the development of capabilities to create a sustainable organization [5]. Wang et al. [20] and Ahuja, Yadav, and Sergio [10] argued that by sensing green opportunities and threats, green leaders could identify the demand for identifying and adopting green practices. This sharpens the employee’s ability to sense environmental risks like energy inefficiencies. In response, green leadership emphasizes the development of dynamic capabilities to enable employees to mitigate such risks. Green leadership guides employees to adopt eco-friendly technologies to overcome risks. For this, providing green training remains effective.

Green leadership can induce dynamic capabilities among employees through environmental awareness [21,22]. Green leadership can lead to employee involvement for a sustainable future [23]. Such leadership involves people in producing innovative methods of doing work to minimize environmental damage, therefore contributing to their dynamic capabilities.

DCT emphasizes adaptability and responsiveness to environmental changes, wherein the role of green leadership cannot be ignored. DCT, as a strategic lens, encourages hospitals to increase sustainable practices that are only possible in the presence of green leadership. The dynamic capabilities of sensing the environment and responding to environmental changes by utilizing employee green attitudes, green self-efficacy, and green empowerment enable employees to avoid environmental risks and count positively towards the environmental performance of the hospitals they work in. Green attitudes of employees encourage them to develop environmental awareness and endeavor to avoid the associated environmental risks, developing a collective sensing capability while working together in the organization. Meanwhile, the employees’ green self-efficacy gives rise to the confidence to perform green actions and helps capture the green opportunities available in the external environment. Moreover, employee green empowerment enhances the sense of ownership. It facilitates employees taking green actions that lead to organizational configuring capability, i.e., identifying and aligning the resources necessary for environmental performance. These constructs explain how green leadership translates into environmental performance and show how individuals become catalysts for building the dynamic capabilities that a hospital needs to stay sustainable.

2.2. Green Transformational Leadership and Environmental Performance (GL–EP)

Ever-increasing environmental challenges have triggered the need to develop durable leadership frameworks for sustainable development. Manioudis and Meramveliotakis [1] developed an integrated theoretical sustainability model and recommended developing more contextualized environmental models. Organizations must respond to external challenges by building internal capabilities for better environmental performance.

The role of green transformational leadership in shaping environmental performance cannot be ignored. Iqbal and Ahmad [9] conducted a study on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Pakistan. They found sustainable leadership to be a significant contributor to organizational learning that improved sustainable performance. Apart from green leadership, they recommended building frameworks for in-depth study of GL and EP relationships in different contexts.

Many studies have developed a consensus that GL strongly influences environmental outcomes rather than generic leadership styles. GL effectively contributes to environmental sustainability by aligning leadership vision. This vision enables them to take green initiatives, develop employee behaviors, and embed sustainable practices in their organizations [9,24,25,26]. Such leaders generally make environmentally responsible decisions [27] and create a culture for ecological resource conservation [28,29].

Green leadership minimizes environmental harm by promoting resource-efficient practices. It prefers reduced energy use, recycling, and the adoption of eco-friendly production systems [18,30]. These strategic moves differentiate GL from traditional leadership styles, particularly in high-impact sectors such as healthcare.

GL develops dynamic organizational capabilities by involving employees. This includes adopting green practices and avoiding practices that create environmental threats. Deng et al. [12] and Yousaf [22] argued that green leaders initiate the organizational routines directed at structural modifications for green innovation. This helps them achieve sustainability goals. Dynamic capabilities make organizations flexible to respond to the external environment and to take advantage of available opportunities [4,31,32]. These strategies enable them to exploit innovative pathways for sustainability [2,33].

Another important component of this leadership–sustainability nexus is the role of green human resource management—GHRM [34]. GHRM practices help translate the vision of leaders into practice at the individual level. Multiple researchers affirm that by adopting GHRM practices like green recruitment, training, and performance management, GL collectively reinforces sustainable behaviors [35,36]. Luo et al. [35] specifically highlighted the need to identify more factors that contribute to sustainability in the healthcare sector of Pakistan.

Similarly, Nguyen et al. [37] examined the interplay of government policies and GHRM in Vietnamese organizations. They found that GL and supportive policies significantly influence GHRM adoption and employee commitment toward sustainability. However, they argued that employee commitment alone cannot be very effective in achieving sustainable performance, reaffirming GL’s strategic importance in sustained environmental outcomes.

Another critical mechanism links leadership to environmental performance, which affects employee pro-environmental behavior (PEB). Employees’ eco-friendly actions show their values and are shaped by leadership influences and organizational culture. Deng et al. [12] and Afridi, Ali, and Zahid [11] suggest that PEB, as an adaptive approach to changing environments, can be significantly driven by green leadership. Furthermore, GL promotes organizational culture by presenting green leaders as role models. They set behavioral parameters and reinforce ecological responsibility to ensure environmental sustainability [20,38,39,40]. These behavioral and cultural transformations can enhance waste management and resource efficiency [41].

Earlier researchers have also performed sector-specific studies. For instance, Bentahar, Benzidia, and Bourlakis [42] conducted a qualitative study in nine French hospitals and highlighted the importance of implementing green supply chain (GSC) practices [40,43]. Implementation of GSC depends on factors like regulatory compliance, cost control, management commitment, and employee training. While their study did not directly measure GL, they recommended further exploration of GL to develop sustainability-driven mechanisms

Ahmad et al. [36] highlighted the importance of GHRM practices in contributing significantly to environmental performance in the hospitality sector. However, GHRM practices cannot become effective unless green leaders play their role in shaping them. They also examined green organizational culture and a sense of environmental responsibility as mediators of this relationship. This highlights the role of GL in sustainable transformation.

Iqbal and Ahmad [44] examined the methods of embedding sustainable leadership into sustainable performance by considering a sample of 369 small and medium-sized enterprises in Pakistan. They found a significant positive effect of sustainable leadership on organizational learning that significantly influences sustainable performance. They argued that other factors can also influence environmental performance besides these factors.

Based on the above arguments, green transformational leadership drives environmental sustainability. GL operates at multiple levels to enhance environmental performance. Its effectiveness lies not only in initiating change but in embedding sustainability into the organization’s behavioral, structural, and cultural fabric. Therefore, this study posits the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H1:

Green transformational leadership positively impacts environmental performance in hospitals.

2.3. Employees’ Green Attitude (GA) as a Mediator

Employees’ green attitude is a positive intention that inclines employees to take environmental sustainability initiatives. It can work as a mediator and can support the GL–EP relationship. Green leadership educates its employees by displaying actions that promote environmental sustainability [40]. However, the relationship between GL and employees’ attitudes has been examined in other contexts, leaving space to examine it in hospitals [17]. Employees’ green attitudes are formed when green leadership places greater value on green practices in their organizations. Green leadership shapes employees’ green attitudes by setting an example, promoting environmental values, involving staff in eco-friendly efforts, offering sustainability training, and recognizing green actions. The effectiveness of green leadership can be realized if their employees have the same tendencies. The attitudes can be formed by being a role model, providing training, and evaluating the employee’s performance using relevant metrics. Employees’ green attitudes are strongly related to environmental performance [45]. Chen et al. [46], argued that employees’ green attitudes could mediate the GL–EP relationship in the manufacturing industry. However, its role in the service sector is unknown. Employees’ green attitudes developed by their green leaders help achieve sustainability goals at individual and organizational levels [19].

Employees with green attitudes use organizational resources efficiently, avoid resource wastage, and prefer using recycled materials. This is how they stay successful in achieving pro-environmental performance. Therefore, we posit that unless the leaders shape the green attitudes of their employees, they cannot individually achieve better environmental performance. Therefore, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis H2:

Employees’ green attitude mediates between GL and EP.

2.4. Green Empowerment (GE) as a Mediator

Green empowerment equips individuals to perform green actions by equipping them with the required skills, knowledge, and resources. Green transformational leadership can ensure employee empowerment by providing them with the necessary resources and training their employees in sustainable routines. Along with training, they must provide the financial resources necessary to attain and use energy-efficient initiatives. Green empowerment as a part of green organizational culture boosts environmental performance, making green transformational leadership more desirable. Green transformational leaders create an environment that promotes open communication and minimizes conflicts regarding using resources for sustainable practices [38].

Empowered employees constitute human and social capital which counts positively towards organizational goals [47]. They believe in developing social networks and try to remain connected to their leaders. They also demand the necessary resources, including the knowledge and skills required to perform green actions. Employees with skills and resources are able to comply with environmental demands [48]. Empowered employees can effectively avoid environmental problems and improve environmental performance. Green empowerment can be critical in promoting environmental performance by providing individuals with the required skills, knowledge, and resources. By using these resources, they show better compliance with environmental standards [49]; therefore, green empowerment is a meaningful contribution to improving environmental performance.

Hypothesis H3:

Green empowerment mediates between green transformational leadership and environmental performance.

2.5. Green Self-Efficacy (GS) as a Mediator

Green self-efficacy is believing in one’s own ability to take effective environmental actions [23]. Evidence from Chinese manufacturing companies found that managers with higher levels of green self-efficacy displayed higher levels of environmental responsibility. Belief in one’s actions is the key to success in terms of environmental goals. Nisar et al. [50] also found green self-efficacy as a significant mediator in the GL–EP relationship in the hospitality industry. Managers with higher levels of green self-efficacy found solutions which used less energy and less water. They also promoted recycling programs. Ahuja, Yadav, and Sergio [10] found green self-efficacy crucial for employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. Green leaders who encourage and appreciate their employees’ practice of green enhance their confidence in performing in the same direction. People with green self-efficacy not only take green initiatives but also guide others to adopt pro-environmental behaviors, enhancing the organization’s efforts towards better environmental performance. GL promotes emotional and psychological safety among their employees [51], which adds to their confidence to perform eco-friendly actions.

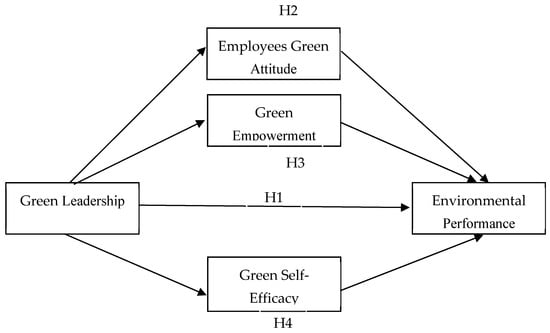

The above studies suggest that employees’ green self-efficacy with strong green leadership in their organizations can promote environmentally responsible actions and performance. Therefore, the hypothesis is as follows (see Figure 1 for proposed hypotheses and the theoretical framework):

Figure 1.

The research framework.

Hypothesis H4:

Green self-efficacy mediates between green transformational leadership and environmental performance.

3. Methodology

3.1. Hospitals in Pakistan as Context

Hospitals generate a significant portion of solid waste, including infectious, hazardous, pharmaceutical, radioactive, and general [2,7]. The improper disposal of hospital waste leads to environmental degradation and air and water pollution [52]. The release of toxic chemicals from hospital waste contaminates soil, groundwater, and surface water, leading to adverse effects on the environment and human health in Pakistan [2] that create public health issues. Pakistan is among the countries facing an acute environmental crisis, with various factors contributing to a dire situation. According to IQAir’s 2021 report, Lahore, Pakistan’s capital city, is among the most polluted places in the world. Mismanagement of medical and technological waste majorly contributes to this alarming state of affairs. As a result, there is an urgent need for environmental activism to bring this issue to the attention of leaders and the general public to protect the environment. Environmental activism has gained widespread popularity with the increasing severity of pollution and global warming, prompting more companies to adopt eco-friendly practices [53]. To safeguard the survival of humans and other living things, controlling the environmental harm-causing factors is important.

Pakistan’s hospitals generate enormous amounts of waste daily, including plastic, textile, food, glass, and others [9,12]. At the same time, Pakistan’s healthcare industry has a large workforce. It is important to avoid adverse environmental effects by building their attitudes, empowering them, and developing their self-efficacy towards environmental protection, where green leaders can play a significant role. Despite the intense focus on environmental protection, the research on the role of leadership along with other mediators is still in its infancy, and the mechanisms of leadership that promote enhanced environmental performance remain poorly understood [11,12].

We focused on 25 hospitals, which allowed us to balance obtaining meaningful data and managing logistical constraints. These hospitals were selected based on their well-reputed services and environmental concerns. The number of respondents in these hospitals provides sufficient statistical power to detect significant relationships and mediating effects. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are explained below.

Inclusion criterion: Hospitals with specific certifications (e.g., ISO 14001 for environmental management) should ensure they have some foundational practices in place regarding environmental management. Exclusion Criterion: Hospitals that do not possess any environmental-related certification were excluded from the examination.

3.2. Data Collection Procedure

A quantitative research design was used to collect data through self-administered questionnaires. A sample of male and female private hospital employees with 1–3 years of experience was used. Purposive sampling was used to acquire a representative sample. The questionnaires were distributed by making in-person visits to the different hospitals. The respondents were given a short overview of the purpose of the study. Over the course of four months, data were acquired from 355 employees from 25 selected hospitals. After removing inappropriate responses, a total of 312 valid responses were analyzed. A sample size of 312 healthcare professionals from private hospitals provides a diverse representation of opinions and attitudes within this population. A recommended sample size for such studies is 30–500 [54], which can achieve sufficient statistical power to detect meaningful relationships. The administrators, including the medical officers and nurses who worked under the leader, were asked to express their perceptions about the leadership style and other variables considered for the study.

Table 1 shows a demographic analysis which indicates that 18.9% of respondents had a Bachelor’s degree, 60.2% had a Master’s degree, and 20.8% had an MS degree. The majority of respondents (about 44%) were between the ages of 36 and 45, with 31.7% between the ages of 46 and 55. While 74.3% of respondents were male, only 25.6% were female.

Table 1.

Demographic information of respondents, n = 312.

3.3. Questionnaire

Previous research studies provided the basis for all the instruments utilized to assess the fundamental concepts. Multi-item measures were utilized for all constructs. A green transformational leadership scale with six items was adopted by Chen, Chang, and Lin [55]. Roscoe et al. [56] adopted an eight-item scale for environmental performance and a six-item scale for green self-efficacy. The study by Wesselink, Blok, and Ringersma [57] was the source for the five-item scale for green attitude and the five-item scale for green empowerment.

We chose to include hospitals in our study due to their significant role in providing healthcare facilities to the public in Pakistan. According to a report published by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) in 2020 [58], there were a total of 13,856 hospitals in Pakistan, comprising both public and private sector hospitals. Private hospitals comprised about 45% of the total hospital facilities, with 6155 registered private hospitals, while the remaining 7701 were public sector hospitals. In Pakistan, Arub et al. [52] found that hospitals produce 265.7 tons of medical waste per day.

3.4. Common Method Bias Assessment

Minimizing common method bias was ensured by using a few strategies, such as the respondents’ anonymity being protected by not collecting names or identification numbers and their responses being kept confidential. This reassured participants and likely reduced social desirability bias. Additionally, participants gave their consent to take part in the survey beforehand. Moreover, the questionnaire was structured to obscure the nature of the dependent and independent variables, preventing any hints that might influence the respondents’ answers. Furthermore, Harman’s single-factor test was performed and showed that only 23.6% of the variance could be attributed to a single factor in the unrotated solution. According to experts, a result below 50% is acceptable and indicates a reduced risk of common method bias [59].

4. Results

The proposed hypotheses were tested through PLS-SEM for its modern assessment features. Smart PLS 3.0 was used as it has gained acceptance in business and hospitality sectors for its user-friendly interface [60]. Moreover, PLS-SEM is well-suited for exploratory research and predictive modeling. This makes it ideal for this study. It can handle multiple latent variables, making it suitable for analyzing the interplay between GL, EP, and other variables. Finally, PLS-SEM remains a robust choice even with smaller sample sizes [61], i.e., 312 respondents for this study. The model’s evaluation examined two models: the outer (measurement) model and the inner (structural) model, as per the rule of thumb [62]. Previous research has proven that PLS-SEM is a useful method for assessing structural modeling [61].

4.1. Measurement Model Assessed

Following the methods of previous researchers [63], it was deemed mandatory to assess the internal consistency and convergent validity using composite reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Composite reliability and AVE.

The partial least squares (PLS) method assisted in examining the measurement and structural models along with the bootstrapping re-sampling procedure. To satisfy the measurement model, Cronbach’s alpha values were examined for reliability, which resulted in values above 0.7 [63]. However, values less than 0.7 are also acceptable for small samples [64,65]. Further, factor loadings were examined for convergent validity and average variance extracted measures. All values satisfied the threshold of 0.7, while AVE values were stronger than the threshold of 0.5 [63]. At the same time, items with values less than 0.7 were dropped. For further analysis, the discriminant validity was assessed through the Fornell and Larcker (1981) [66] criterion, Table 3.

Table 3.

Fornell and Larcker criterion.

Table 3 explains the discriminant validity, i.e., whether the variables of the study are different from one another and overlaps of the constructs can create misleading results. Fornell and Larcker’s criterion [66] is used to examine the discriminant validity. The discriminant validity is established when the square root of the AVE is greater than the construct’s correlation with any other variable. Table 3 clearly shows that the square root of the AVE for environmental performance is 0.907, which is greater than the other values obtained in this study. The same is the case with other constructs.

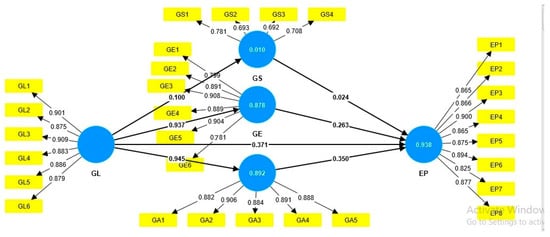

To assess the model’s goodness of fit, we examined the R-square value, which was found to be 0.938, indicating a strong fit. Additionally, we evaluated the effect size using f-square scores, adhering to Cohen’s [67] recommendations of small (0.02), medium (0.15), and large (0.35) effect sizes. Our findings revealed small to medium effect sizes for various variables, including green attitude (f2 = 0.110), green self-efficacy (f2 = 0.282), green empowerment (f2 = 0.142), green leadership (f2 = 0.211), and environmental performance (f2 = 0.351). We also examined the Q square values and found results above zero for all variables, indicating their predictive relevance—see Table 4.

Table 4.

Path coefficients, significant values and model fit indices.

4.2. The Structural Model

Figure 2.

Hypotheses tested.

Table 4 shows that green leadership has a positive and significant relationship with employees’ environmental performance (β = 0.371, p < 0.05). Green leadership also had a positive and significant relationship with the three other variables included for examination, i.e., green attitude (β = 0.945, p < 0.05), green empowerment (β = 0.937, p < 0.05), and green self-efficacy (β = 0.759, p < 0.05). At the same time, these three constructs had a positive relationship with EP. Green attitude (β = 0.350, p < 0.05), green empowerment (β = 0.263, p < 0.05), and green self-efficacy (β = 0.024, p < 0.05) have a positive and significant effect on the environmental performance of employees working in hospitals in Pakistan. Green self-efficacy has a weak positive relationship in determining environmental performance. this shows that it is not the sole driver of environmental performance.

Results of PLS-SEM via examining the mediation model indicate that green attitude (β = 0.291, p < 0.05), green empowerment (β = 0.112, p < 0.05), and green self-efficacy (β = 0.154, p < 0.05) significantly and directly affect environmental performance. Furthermore, these three variables partially mediate the relationship between green leadership and environmental performance, as the direct effect of green leadership on environmental performance becomes smaller (but still significant) when the effects of green attitude, green empowerment, and green self-efficacy are considered. Specifically, green attitude has the most substantial direct effect on environmental performance, followed by green self-efficacy and green empowerment. Additionally, the total effect of green leadership on environmental performance was significant. It indicates that green leadership is an important factor in predicting environmental performance, even when accounting for the mediating effects of green attitude, green empowerment, and green self-efficacy. Therefore, hospitals should promote green leadership that fosters employees’ positive attitudes, green empowerment, and self-efficacy to improve environmental performance.

5. Discussion

Iqbal and Ahmad [44] emphasized the multifaceted factors contributing to sustainable development goals (SDGs). The study highlights that green transformational leadership significantly improves the environmental performance of hospitals. Leaders who prioritize sustainability inspire staff to adopt eco-friendly practices, aligning with SDG 3, i.e., good health and well-being, by promoting healthier hospital environments. The research also reveals that green attitude, empowerment, and self-efficacy play crucial roles in strengthening this leadership–performance link. These mediators encourage proactive behaviors and support a culture of environmental responsibility. This directly supports SDG 12, i.e., responsible consumption and production, by fostering efficient resource use and waste reduction. Moreover, by encouraging energy-conscious practices within hospital operations, the study contributes to SDG 7, i.e., affordable and clean energy, through reduced energy consumption and enhanced awareness. Therefore, the findings emphasize the importance of sustainable leadership in healthcare, showing how internal motivation and empowerment can drive substantial environmental progress while promoting health, energy efficiency, and sustainable consumption.

The study examined the basic relationship of green leadership on environmental performance in hospitals in Pakistan. Moreover, three mediating relationships were also examined. Firstly, this study found a positive relationship between green leadership and environmental performance, aligned with earlier findings [5,24,55], validating Hypothesis 1. This shows that green transformational leadership significantly yields environmental benefits for hospitals [2]. Green leadership encourages employees to reduce ecologically adverse effects. By spreading green awareness among employees, green leadership becomes a healthy source of environmental protection. Green leaders identify the risks and guide their employees to avoid such risks. They are a source of improved patient outcomes and reduced operational costs [2,33]. Reduced wastage and use of eco-friendly materials are the healthy sources the green leadership recommends [2,32]. Green leadership helps hospitals reduce their solid and liquid medical and non-medical waste. Mousa and Othman [2] support the findings that hospital green leadership positively affects medical waste management. Similarly, Lee and Lee [68] found that implementing green practices, such as segregation and recycling, significantly reduced medical waste.

Secondly, this study examined green attitude as a mediator (Hypothesis 2). Green leadership educates people and drives their thinking toward environmental protection [30,55]. Green leadership promotes environmental stewardship through decision-making processes, policies, and practices. When involved in such decisions, employees follow their leaders’ guidance for protecting the environment. Green attitude refers to individuals’ beliefs, values, and attitudes towards environmental sustainability practices [19,46]. Gultom [17] found green leaders who impart knowledge and identify risks in advance. This helps employees shape their behaviors in advance to overcome risks and take green initiatives [69].

Thirdly, green self-efficacy was examined as a mediator (Hypothesis 3). Individuals with a stronger belief in their abilities to effectively engage in environmentally sustainable behaviors adapt more promptly. Moreover, they set clear goals for themselves and try to achieve them as they are set [17,23,45]. Green leadership sets goals like reduced energy and water usage. Employees with high self-efficacy try to achieve these goals in letter and spirit, ensuring enhanced environmental performance. Ahuja, Yadav, and Sergio [10] also affirmed that GL significantly affected EP. Employees’ green self-efficacy effectively translates green leadership initiatives into actions. They take the orders and try to obey, influencing actual environmental performance outcomes. Hospitals with green transformational leaders who actively promote sustainable practices and ensure employees’ confidence can increase environmentally sustainable behaviors [30].

Lastly, green empowerment was examined as a mediator (Hypothesis 4). Empowering employees to display environmentally friendly behaviors contributes to sustainability initiatives [70]. To create an environmentally responsible culture, green leadership provides resources and decision-making autonomy to its employees. This has a significant impact on environmental performance. The employees use materials and equipment that reduce energy consumption and waste generation [38]. The effectiveness of green leadership may remain limited without employees’ empowerment towards environmental protection and sustainability. Green empowerment is about providing nurses with knowledge, skills, and resources to adopt sustainable practices during everyday work. These leadership actions generate an engaged and committed workforce, improving environmental performance [70].

Dynamic capabilities theory also supports the findings of the present study. The theory emphasizes the importance of an organization’s ability to adapt to changing circumstances and develop sustainable practices. Green transformational leadership may positively affect employees’ environmental performance in hospitals [70]. Green transformational leadership enhances nurses’ ability to deal with environmental challenges by reducing environmental footprints. Green leadership develops green attitudes among employees, ensures green empowerment, and boosts nurses’ green self-efficacy. Green transformational leadership acts as a transformative force for organizations and employees to develop dynamic capabilities. Leaders who focus on innovation and adaptability can develop organizational structures and cultures. It is not possible without employees. GL enhances dynamic capabilities among individuals by fostering organization-wide learning. This helps staff become more environmentally aware, confident, and skilled. This encourages individuals to take initiative, solve problems creatively, and work toward sustainability goals. As a result, the hospital becomes more adaptable and capable of managing change. Leaders guide this by setting clear green values, supporting learning, and rewarding eco-friendly efforts. When combined, these factors lead to improved environmental performance [70,71]. Therefore, by promoting green leadership and the related factors among nurses, hospitals can create a sustainable healthcare system.

6. Conclusions

Adverse ecological effects can be minimized by adopting eco-friendly practices. This underscores the importance of GL in achieving sustainability goals, as dynamic capabilities theory suggests that organizations adapt to changing circumstances to stay competitive. For hospitals, this means being able to respond to changes in environmental regulations, stakeholder expectations, and resource availability. GL plays a crucial role in this process by shaping employees’ attitudes, empowering them, and enhancing their self-efficacy to create a culture of sustainability that benefits the environment. Hospitals can enhance their environmental performance by promoting green leadership and the associated factors, especially green attitude and empowerment of employees.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) explains how hospitals can adapt, innovate, and transform in response to environmental shifts, such as the growing demand for sustainability. In the healthcare sector, green leadership is vital in guiding hospitals to understand environmental challenges, spot opportunities such as eco-friendly innovations, and change their practices, like reducing waste to enhance environmental performance.

Employees’ green attitude shows their motivation to recognize and respond to environmental concerns. DCT considers the hospital’s ability to identify change. Green leadership fosters an eco-conscious mindset, which in turn leads to behaviors that support better environmental outcomes. Moreover, empowering employees is key to helping them act on green ideas. This freedom to contribute aligns with DCT’s notion of capturing opportunities. When leaders support and empower their teams to take the lead on sustainability efforts, it boosts environmental performance.

Further, self-efficacy, a belief in one’s ability to make a difference, encourages employees to reshape their tasks and habits in environmentally sustainable ways. This reflects DCT’s focus on adjusting its capabilities. Green leadership enhances employees’ confidence, and that confidence often translates into meaningful environmental improvements. DCT puts the responsibility on green leaders to shape sustainability outcomes by developing green attitudes among healthcare providers, empowering them to use pro-environmental practices, and building their self-efficacy towards environmental protection. This implies that interventions aimed at enhancing green attitude, empowerment, and self-efficacy can amplify the impact of GL on EP.

6.2. Managerial Implications

The managerial implications are framed into two sub-categories, i.e., the hospitals and the community. Green transformational leadership promotes environmental sustainability by reducing the negative impact of hospitals on the natural environment. Three major implications of adopting green leadership in hospitals include encouraging environmental stewardship by adopting green leadership, implementing sustainable practices by developing employee attitudes, and promoting sustainable healthcare services by empowering employees.

Encouraging environmental stewardship through green leaders means working to create a green hospital culture where employees understand environmental requirements and take steps to reduce negative environmental impacts. Secondly, it encompasses implementing sustainable practices through green leadership that actively derive and implement them in hospitals. This can be successfully done by empowering hospital employees. Further, they promote the use of sustainable products, i.e., green leaders focus on acquiring and using medicines and equipment that can be recycled or sustainably disposed of and have biodegradable characteristics that promote sustainability.

Hospitals with effective green leadership take proactive steps to address environmental concerns. Deng et al. [12] recommended strong green leadership for better “environmental management” practices, such as adopting sustainable strategies in advance of legal requirements. This proactive approach enables hospitals to anticipate and manage environmental challenges before they escalate. It is important for hospital leaders to adopt sustainable practices and empower their employees to contribute successfully towards sustainability. Green empowerment can be a valuable tool in achieving this goal and improving the environmental performance of hospitals.

The weak relationship between green self-efficacy and environmental performance is of vital concern. It is possible that leaders have not yet set clear environmental goals to achieve, which is creating confusion among their employees. To overcome this, leaders have to clearly define eco-goals and provide support to their employees to enhance their confidence, which would lead to the achievement of environmental goals.

Further, the community can benefit from hospitals. Hospitals that perform well environmentally contribute to the overall health of the community by reducing pollution and minimizing their environmental footprint. Moreover, hospitals showing better environmental performance serve as role models for other organizations and individuals in the community to promote sustainable practices.

6.3. Limitations and Future Directions

The use of cross-sectional and primary data gathered from hospitals presents some limitations. Cross-sectional data may not account for changes over time, and using primary data may lead to biases in the data collection process. Additionally, using only hospitals as the sample may limit the generalizability of the findings to other healthcare settings. The application of DCT in studying green leadership and environmental performance is a promising direction. However, future research could benefit from exploring the influence of other theoretical perspectives, such as institutional theory or stakeholder theory, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship.

This study focused on three mediators: green attitude, green self-efficacy, and green empowerment. Future studies could expand on this by examining other potential mediators, such as employees’ environmental consciousness, green knowledge, green procurement practices adopted by hospitals, etc. Moreover, assessment of leaders’ personality traits that can enforce environmental performance would be an interesting contribution to the literature. Similarly, the employee traits necessary to adopt environmentally friendly behaviors would be another strong contribution. These contributions are still missing from the literature. The present study highlights the importance of green leadership in promoting hospital environmental performance. Future research could build on these findings by examining different leadership styles that shape environmental sustainability across cultures. Moreover, the influence of external policy interventions on hospital environmental performance was not independently verified. It is suggested that future researchers should consider the influence of external policy interventions on hospital environmental performance when studying the connection between green leadership and environmental performance (GL–EP) in hospitals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S., S.S. and M.I.M.; Methodology, M.I.M.; Validation, F.S., S.S. and M.I.M.; Formal analysis, M.I.M.; Investigation, F.S. and M.I.M.; Resources, F.S.; Writing—original draft, F.S. and M.I.M.; Writing—review & editing, S.S.; Supervision, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. However, APC is funded by Prince Sultan University, Riyadh.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approval was taken from the Ethics Committee of COMSAT University, Attock campus.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prince Sultan University for their support and for providing APC for this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad Strokes towards a Grand Theory in the Analysis of Sustainable Development: A Return to the Classical Political Economy. New Polit. Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, S.K.; Othman, M. The Impact of Green Human Resource Management Practices on Sustainable Performance in Healthcare Organisations: A Conceptual Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. The Future of Leadership in Learning Organizations. J. Leade. Stud. 2000, 7, 18–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Gelaidan, H.M.; Shah, S.H.A.; Amjad, R. Green Transformational Leadership and Green Creativity? The Mediating Role of Green Thinking and Green Organizational Identity in SMEs. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 977998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arici, H.E.; Uysal, M. Leadership, Green Innovation, and Green Creativity: A Systematic Review. Serv. Ind. J. 2022, 42, 280–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, Q.A.; Zafar, A.; Shoukat, M.; Ikram, M. Green Transformational Leadership and Green Performance: The Mediating Role of Green Mindfulness and Green Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Manag. Excell. 2017, 9, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaposi, A.; Nagy, A.; Gomori, G.; Kocsis, D. Analysis of healthcare waste and factors affecting the amount of hazardous healthcare waste in a university hospital. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Nurunnabi, M.; Subhan, Q.A.; Shah, S.I.A.; Fallatah, S. The impact of transformational leadership on job performance and CSR as mediator in SMEs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Zhang, X.; Mao, D.; Kashif, M.; Mirza, F.; Shabbir, R. Unraveling the Impact of Eco-Centric Leadership and Pro-Environment Behaviors in Healthcare Organizations: Role of Green Consciousness. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, J.; Yadav, M.; Sergio, R.P. Green Leadership and Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model with Rewards, Self-Efficacy and Training. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2023, 39, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, S.A.; Ali, S.Z.; Zahid, R.A. Nurturing environmental champions: Exploring the influence of environmental-specific servant leadership on environmental performance in the hospitality industry. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Cherian, J.; Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Samad, S. Conceptualizing the role of target-specific environmental transformational leadership between corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behaviors of hospital employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.H.A.; Fahlevi, M.; Rahman, E.Z.; Akram, M.; Jamshed, K.; Aljuaid, M.; Abbas, J. Impact of green servant leadership in Pakistani small and medium enterprises: Bridging pro-environmental behaviour through environmental passion and climate for green creativity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, J.; Abid, N.; Sarwar, H.; Veneziani, M. Environmental ethics, green innovation, and sustainable performance: Exploring the role of environmental leadership and environmental strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378, 134639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.U.; Saqib, A.; Abbasi, M.A.; Mikhaylov, A.; Pinter, G. Green leadership, environmental knowledge sharing, and sustainable performance in manufacturing industry: Application from upper echelon theory. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultom, M. Green Leadership as a Model of Effective Leadership in Hospital Management in the New Normal Era. Budap. Int. Res. Critics Inst. J. 2022, 5, 19900–19910. [Google Scholar]

- Patwary, A.K.; Sharif, A.; Aziz, R.C.; Hassan, M.G.B.; Najmi, A.; Rahman, M.K. Reducing Environmental Pollution by Organisational Citizenship Behaviour in Hospitality Industry: The Role of Green Employee Involvement, Performance Management and Dynamic Capability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 37105–37117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Chai, H.; Shao, J.; Feng, T. Green Entrepreneurial Orientation for Enhancing Firm Performance: A Dynamic Capability Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 1311–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Feng, T.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, Y. Enabling Green Supply Chain Integration via Green Entrepreneurial Orientation: Does Environmental Leadership Matter? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, H.; Aftab, J.; Ishaq, M.I.; Atif, M. Achieving Business Competitiveness through Corporate Social Responsibility and Dynamic Capabilities: An Empirical Evidence from Emerging Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, Z. Go for Green: Green Innovation through Green Dynamic Capabilities: Accessing the Mediating Role of Green Practices and Green Value Co-Creation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 54863–54875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, A.; Yang, K. Examining the Influence of Transformational Leadership and Green Culture on Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Empirical Evidence from Florida City Governments. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2022, 42, 738–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; El-Askary, A.; Meo, M.S.; Hussain, B. Green Transformational Leadership and Environmental Performance in Small and Medium Enterprises. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2022, 35, 5273–5291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, U.I.; Nisar, Q.A.; Nasir, N.; Naz, S.; Haider, S.; Khan, W. Green HRM, Green Innovation and Environmental Performance: The Role of Green Transformational Leadership and Green Corporate Social Responsibility. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 45353–45368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.R.; Uddin, M.A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Dey, M.; Rana, T. Ecocentric Leadership and Voluntary Environmental Behavior for Promoting Sustainability Strategy: The Role of Psychological Green Climate. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1705–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green Innovation and Environmental Performance: The Role of Green Transformational Leadership and Green Human Resource Management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre-Mills, J.J.; Makaulule, M.; Lethole, P.; Pitsoane, E.; Arko-Achemfuor, A.; Wirawan, R.; Widianingsih, I. Ecocentric living: A way forward towards zero carbon: A conversation about indigenous law and leadership based on custodianship and praxis. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2023, 36, 275–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H. Green Innovation Strategy and Green Innovation: The Roles of Green Creativity and Green Organizational Identity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ali, S.S. Exploring the Relationship between Leadership, Operational Practices, Institutional Pressures and Environmental Performance: A Framework for Green Supply Chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 160, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Aguilera, R.V. Increasing Corporate Social Responsibility through Stakeholder Value Internalization (and the Catalyzing Effect of New Governance): An Application of Organizational Justice, Self-Determination, and Social Influence Theories. In Managerial Ethics: Managing the Psychology of Morality; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011; pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Swidi, A.K.; Gelaidan, H.M.; Saleh, R.M. The Joint Impact of Green Human Resource Management, Leadership and Organizational Culture on Employees’ Green Behaviour and Organisational Environmental Performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Schmidt, J.; Teece, D.J. Ecosystem Leadership as a Dynamic Capability. Long Range Plan. 2023, 56, 102270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.A.; Alyahya, M.; Juhari, A.S.; Alshiha, A.A. Green HRM practices and employee satisfaction in the hotel industry of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Oper. Quant. Manag. 2022, 28, 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Zaman, S.I.; Jamil, S.; Khan, S.A. The Future of Healthcare: Green Transformational Leadership and GHRM’s Role in Sustainable Performance. Benchmarking 2025, 32, 805–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Islam, T.; Sadiq, M.; Kaleem, A. Promoting Green Behavior through Ethical Leadership: A Model of Green Human Resource Management and Environmental Knowledge. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.Q.; Nguyen, T.N. Exploring the Relationship of Green HRM Practices with Sustainable Performance: The Mediating Effect of Green Innovation. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2025, 8, 1665–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Sibley, C.G. The Big Five Personality Traits and Environmental Engagement: Associations at the Individual and Societal Level. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Nathan, M. Knowledge Workers, Cultural Diversity and Innovation: Evidence from London. Int. J. Knowl.-Based Dev. 2010, 1, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, M.; Fang, W.; Feng, T. Green Intellectual Capital and Green Supply Chain Integration: The Mediating Role of Supply Chain Transformational Leadership. J. Intellect. Cap. 2023, 24, 877–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-de Castro, G.; Amores-Salvadó, J.; Díez-Vial, I. Framing the Evolution of the “Environmental Strategy” Concept: Exploring a Key Construct for the Environmental Policy Agenda. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 1308–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentahar, O.; Benzidia, S.; Bourlakis, M. A Green Supply Chain Taxonomy in Healthcare: Critical Factors for a Proactive Approach. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2023, 34, 60–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L. Investigating the relationship between green supply chain purchasing practices and firms’ performance. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2023, 16, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H. Sustainable Development: The Colors of Sustainable Leadership in Learning Organization. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.M.; Mashi, M.S.; Azizan, N.A.; Alotaibi, M.; Hashim, F. When and How Green Human Resource Management Practices Turn to Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behavior of Hotel Employees in Nigeria: The Role of Employee Green Commitment and Green Self-Efficacy. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2023, 26, 383–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Yeh, S.L.; Cheng, H.I. Green Shared Vision and Green Creativity: The Mediation Roles of Green Mindfulness and Green Self-Efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S Back in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Multilevel Theory of Social Change in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Gao, C.; Chen, F.; Zhang, L.; Li, M. Can Empowering Leadership Promote Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behavior? Empirical Analysis Based on Psychological Distance. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 774561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu Sarfo, P.; Zhang, J.; Nyantakyi, G.; Lassey, F.A.; Bruce, E.; Amankwah, O. Influence of Green Human Resource Management on Firm’s Environmental Performance: Green Employee Empowerment as a Mediating Factor. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0293957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar, Q.A.; Haider, S.; Ali, F.; Gill, S.S.; Waqas, A. The Role of Green HRM on Environmental Performance of Hotels: Mediating Effect of Green Self-Efficacy and Employee Green Behaviors. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 25, 85–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senem, Ç.M.; Öztırak, M. The Mediating Role of Green Organizational Climate in the Effect of Sustainable Leadership on Psychological Security Perception. J. Manag. Theory Pract. Res. 2024, 5, 141–172. [Google Scholar]

- Arub, S.; Ahmad, S.R.; Ashraf, S.; Majid, Z.; Rahat, S.; Paracha, R.I. Assessment of Waste Generation Rate in Teaching Hospitals of Metropolitan City of Pakistan. Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 6, 1809–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Soopramanien, D. Types of Place Attachment and Pro-Environmental Behaviors of Urban Residents in Beijing. Cities 2019, 84, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizan, N.H.; Mahmud, Z.; Rambli, A. Rasch rating scale item estimates using maximum likelihood approach: Effects of sample size on the accuracy and bias of the estimates. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 2526–2531. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.H. Green Transformational Leadership and Green Performance: The Mediation Effects of Green Mindfulness and Green Self-Efficacy. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6604–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, S.; Subramanian, N.; Jabbour, C.J.; Chong, T. Green Human Resource Management and the Enablers of Green Organisational Culture: Enhancing a Firm’s Environmental Performance for Sustainable Development. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselink, R.; Blok, V.; Ringersma, J. Pro-Environmental Behaviour in the Workplace and the Role of Managers and Organization. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Health Facilities in Pakistan (2019–2020). 2020. Available online: https://www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files/national_accounts/national_health_accounts/NHA-Pakistan_2019-20.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassani, A.A.; Javed, A.; Radulescu, M.; Yousaf, Z.; Secara, C.G.; Tolea, C. Achieving Green Innovation in Energy Industry through Social Networks, Green Dynamic Capabilities, and Green Organizational Culture. Energies 2022, 15, 5925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.M.; Sun, W.Q.; Tsai, S.B.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Q. An Empirical Study on Entrepreneurial Orientation, Absorptive Capacity, and SMEs’ Innovation Performance: A Sustainable Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ramayah, T. Urban vs. Rural Destinations: Residents’ Perceptions, Community Participation and Support for Tourism Development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory—25 Years Ago and Now. Educ. Res. 1975, 4, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D.L. Starting at the Beginning: An Introduction to Coefficient Alpha and Internal Consistency. J. Pers. Assess. 2003, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Lee, D. Effective Medical Waste Management for Sustainable Green Healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebekozien, A.; Ayo-Odifiri, S.O.; Nwaole, A.N.C.; Ibeabuchi, A.L.; Uwadia, F.E. Barriers in Nigeria’s Public Hospital Green Buildings Implementation Initiatives. J. Facil. Manag. 2022, 20, 586–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraful, A.M.; Niu, X.; Rounok, N. Effect of Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) Overall on Organization’s Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Green Employee Empowerment. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, M.; Aliedan, M.; Agag, G.; Abdelmoety, Z.H. The Antecedents of Hotels’ Green Creativity: The Role of Green HRM, Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership, and Psychological Green Climate. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).