Abstract

Flexible work arrangements have the potential to enhance work–life balance and contribute to more sustainable work environments. However, they may also increase fatigue and lead to greater work–life conflict (WLC). This study offers a novel contribution by examining the relationship between flexible work arrangements—focusing in particular on the cognitive demands of flexible work (CDFW), which encompass the task structuring, scheduling of working times, planning of working place, and coordination with others—and WLC. Specifically, the study investigates the mediating role of workload in this relationship. Furthermore, it also explores whether perceived organizational support (POS) moderates the indirect relationships between CDFW and WLC, within the framework of the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model. Data were collected from a sample of 419 employees in the Italian public sector. The study also controls for potential confounding variables, such as age, gender, duration of employment in public administration, and weekly working hours, to account for their influence on work–life balance and workload. The results highlight a significant positive relationship between planning of the working place and WLC. Additionally, workload plays a mediating role between CDFW subdimensions and WLC. However, POS does not moderate the mediated relationship between CDFW and WLC.

1. Introduction

Over the past five years, remote and hybrid work arrangements have expanded significantly, driven primarily by the COVID−19 pandemic and technological advancements [1]. These models provide employees with greater autonomy, enabling them to choose where, when, and how they work [2,3]. In Italy, too, the pandemic accelerated the adoption of flexible working arrangements, aimed at ensure the continuity of administrative and economic activities and the safeguarding of public health [4,5,6].

However, this expansion occurred without adequate support or adaptation to the specific needs of the public sector. Most public administrations lacked formal smart working policies and were not prepared for a widespread transition to flexible work [7]. To address these situations, a series of regulatory measures have been introduced since 2021 (D.L. 30/2021; 51/2021; D.L. 52/2021; D.L. 1/2022; D. 132/2022), aimed at supporting flexible work models as an alternative to traditional face-to-face arrangements.

Flexible work aligns with the European Community’s sustainability goals, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions, traffic congestion, and energy consumption through the optimized use of workspace [8]. By limiting daily commuting, these arrangements lower the environmental impact. Additionally, minimized physical presence in the office decreases the use of utilities such as heating, cooling, and lighting, enhancing energy efficiency. Beyond environmental benefits, flexible work arrangements are associated with improved work–life balance [9], increased job satisfaction [10,11], and higher overall productivity [12].

Work–life balance refers to the ability to manage family and work responsibilities, and personal time through mechanisms like flexi-time [13]. Employees with greater control over their work experience improved motivation, satisfaction, and performance [14] and reduced work–life conflict [15]. However, this flexibility can also introduce new challenges. It can increase employees’ responsibility for self-managing tasks and schedules, which may lead to elevated workload and stress [16].

Other issues include difficulty maintaining boundaries between work and personal life, constant connectivity, and paradoxically, reduced well-being [17,18]. Recent research has highlighted the positive effects of cognitive demands of flexible work (CDFW) on well-being [19], while others point to its dual effect [20,21].

For instance, Scholze and Hecker [22] interpreted this twofold effect through the lens of the Job Demands-Resources [23] model, which is considered a relevant framework for exploring the bright and dark aspects of digitalization in the workplace. This model posits that job characteristics—namely, demands and resources—jointly influence employee outcomes. Within this framework, flexible work arrangements may function either as resources or demands. CDFW, while potentially fatiguing, can act as challenging demands that foster employees’ cognitive flexibility and motivation [21,24]. For instance, cognitive flexibility can enhance competencies such as problem solving [25], thereby helping employees to adapt to work environments and boosting work engagement and work–life balance. Conversely, excessive cognitive demands may diminish distinctions between work and personal life, increase workload and work–life conflict [26,27,28], and deplete personal resources needed for achieving goals [29]. In buffering these negative outcomes, perceived organizational support (POS) is identified as a relevant protective factor. This not only helps reduce WLC [30,31], but also helps researchers gain a deeper understanding of the differential effects of CDFW subdimensions.

To clarify these mixed findings, this study builds on the JD-R model [22] to examine the interplay between CDFW and its subdimensions (structuring of work tasks, planning of working times, planning of working place, and coordinating with others), organizational support, work–life balance, and workload. In particular, the present study aims to investigate how specific subdimensions of CDFW contribute to increased workload, which may, in turn, positively affect work–life conflict, considering workload as a mediator and perceived organizational support as a moderator. Confounding variables such as gender, age, tenure in public administration, and working hours are also considered.

Understanding this complexity and deepening research in this underexplored field can offer practical guidance to organizations in developing family-friendly flexible work policies and providing the necessary support for employees to manage these arrangements effectively [32].

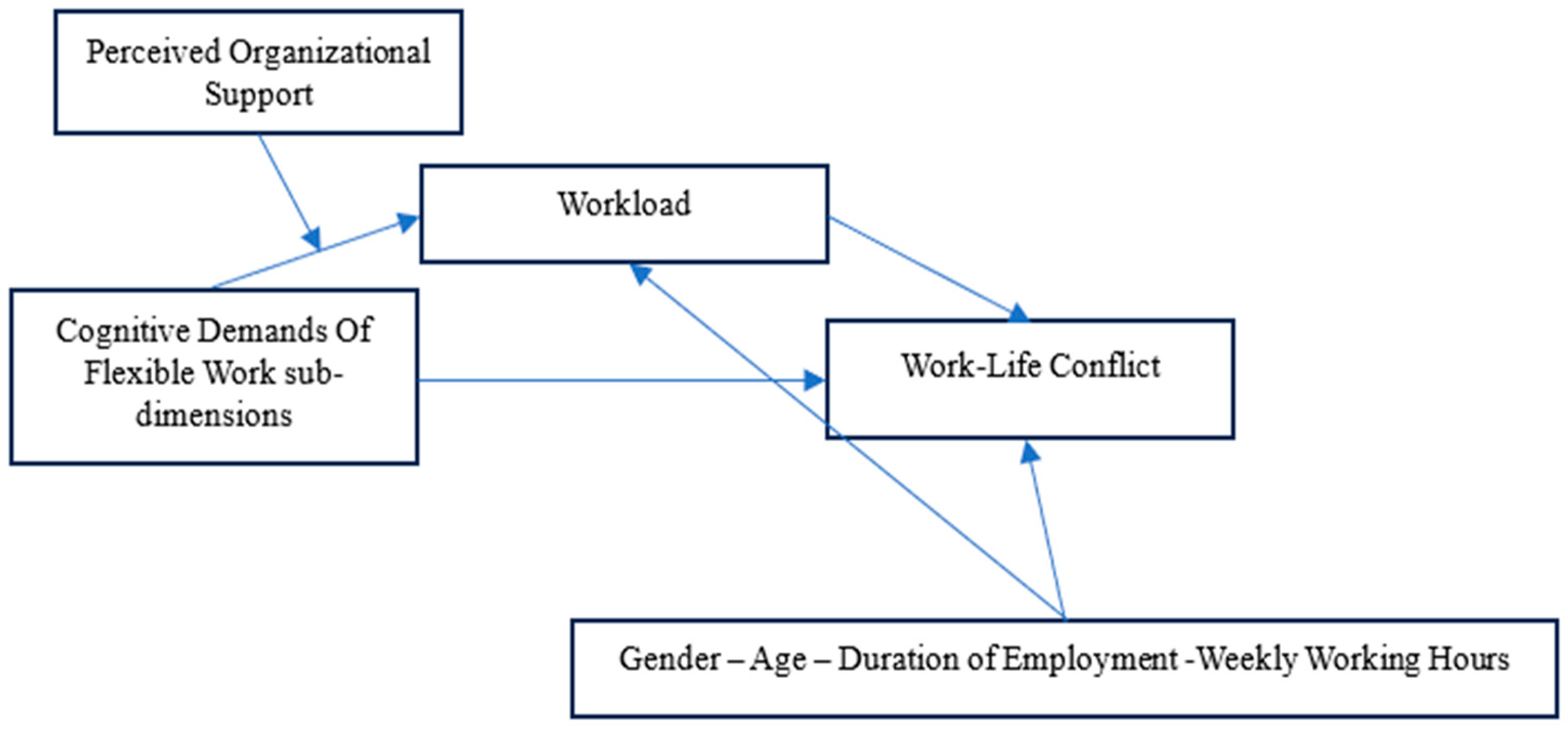

The following sections elaborate on the JD-R model, define the key constructs, outline the methodology, and discuss the findings in detail. The theoretical model, illustrated in Figure 1, is tested using data collected from a sample of 419 Italian public sector employees working under flexible conditions.

Figure 1.

The proposed theoretical model.

2. Literature Background, Conceptual Framework, and Hypotheses

2.1. Cognitive Demands of Flexible Work: Dual Role as Job Resource (Challenge Demand) or a Job Demand?

Flexible work arrangements include hybrid models that alternate between remote and in-person work, as well as activity-based workplaces that allow employees to choose their working environment based on the task at hand [33,34,35]. This deregulation enhances autonomy and discretion [1], offering several advantages, such as improved work–life balance [18], increased performance (facilitated by the ability to organize activities and customize the workplace) [36], innovation [37], and reduced absenteeism [3].

However, flexible work simultaneously imposes additional responsibilities requiring increased adaptability and cognitive flexibility. It may increase mental effort due to heightened surveillance [38], exacerbate work–life conflict [26], and reduce productivity when planning is inadequate or when managerial skills and support are weak [39]. It also impairs communication and coordination with the organization and work teams [40].

Additionally, such practices can lead to employee isolation, diminishing opportunities for social support and, consequently, reducing engagement and organizational commitment [41]. Notably, empirical evidence highlights mixed findings on the relationship between flexible work arrangements and job satisfaction [42] and between flexible work and work–life outcomes [43]. While some studies have highlighted its positive effects on job satisfaction, other studies have reported lower job satisfaction, primarily due to the lack of social interaction [44]. Similarly, while flexible work can facilitate work–life balance and reduce exhaustion [43] by fostering the perception that family and work are compatible, the interference between life and work can lead to psychological conflict [45,46].

To address these challenges, scholars have introduced the construct of cognitive demands of flexible work (CDFW) [47], which encompasses four dimensions: structuring of work tasks, planning of working times, planning of working places, and coordination with others. Although these subdimensions may function as job stressors, existing research indicates that they can also be framed as challenge demands—a form of job demands—which, despite their demanding nature, may contribute to employees’ perceived autonomy, competence development, and learning [20,47,48]. When framed this way, CDFW may positively affect well-being and job satisfaction [49], reduce stress [50], and improve work engagement [51] while reducing job rumination [52].

Interestingly, Prem et al. [47] also found that CDFW did not significantly influence emotional exhaustion, suggesting the need for further insight into their role. Barbieri et al. [20] showed the dual role of CDFW in home-based work. Task and time planning were positively related to job satisfaction and performance, while planning the workplace and coordinating with others were associated with negative outcomes. These effects were moderated by levels of cognitive demands, as constant connectivity can increase workload, fostering rumination beyond working hours and limiting recovery [53].

2.2. Job Demand-Resource (JD-R) Model

The JD-R model [22] offers a robust theoretical framework for examining how flexible work arrangements—and specifically the cognitive demands—can function as either job resources (herein referred to as challenging demands) or job demands. It differentiates job characteristics through two key dimensions: job resources and demands. Job resources refer to the physical, psychological, social, or organizational factors that facilitate motivation and enhance work performance.

Studies have highlighted that job resources are associated with employee engagement, enhancing personal growth and professional development [54,55], and mitigating the effects of job demands [56]. Job demands encompass the physical, psychological, social, and organizational aspects of a job that require effort and may negatively affect well-being and productivity, hindering individual goals.

The model also incorporates personal resources and demands [57]. Personal resources encompass positive self-evaluation and adaptability capacities—such as self-efficacy, resilience, autonomy, and optimism–which enable employees to manage their environment and mitigate the effect of job demands more effectively. They contribute to increasing engagement and well-being, and achieve their goals through a motivational process triggered by the fulfillment of competence, belongingness, and autonomy. In contrast, personal demands refer to the lack of psychological, physical, and social resources that hinder individuals from achieving goals. Within this framework, cognitive flexibility is a key personal resource that activates a motivational mechanism [58], allowing employees to adapt to their work environment, learn new strategies and competencies, and fulfill their psychological needs [59]. It supports sustainable work by helping individuals manage family responsibilities [60] structure work schedules, optimize their workspace, and coordinate effectively with colleagues.

However, under certain conditions, flexible work can still increase mental workload and lead to additional demands of workspace organization [61]. In such a context, CDFW may act as hindrance demands, triggering negative emotions and workload.

2.3. Aim of the Study and Hypothesis Development

The existing literature has yet to clarify the relationship between CDFW and its relationship with work-related outcomes. Particularly, the relationship between CDFW and WLC remains underexplored. Moreover, previous studies have not adequately addressed whether CDFW functions as a job demand (increasing strain) or a job resource (or challenging demands) enhancing flexibility. This study aims to fill these gaps by investigating the relationship between CDFW and its subdimensions in relation to both WLC and workload.

Accordingly, the study seeks to address the following open research question:

- (1)

- Are the cognitive demands of flexible work (i.e., structuring of work tasks, planning of working times, planning of working places, coordinating with others) positively or negatively related to WLC?

- (2)

- Are these same cognitive demands of flexible work positively or negatively related to workload?

Additionally, based on a review of the literature, we identify workload as a potential mediator between CDFW and the work–life conflict relationship. Furthermore, POS has been considered as a relevant protective factor that may enhance our understanding of the dual role of CDFW. The role of these two dimensions is described in detail in the following two sections.

2.4. The Mediating Relationship of Mental Workload Between Cognitive Demands of Flexible Work and Work–Life Conflict (WLC)

Building on prior research, work–life conflict (WLC) and work–life balance (WLB) are influenced by both job demands and job resources, with WLB found to positively affect various workplace outcomes. For instance, WLB has been related to reduced work–life conflict and lower turnover intentions [62], as well as increased job satisfaction and performance [63,64]. In a systematic literature review, Shirmohammadi et al. [65] identified both job resources and demands as antecedents of WLB. Among job demands, they found factors such as high work intensity (e.g., mental workload), limited physical space, technostress, professional isolation, and coordination difficulties with colleagues. In contrast, job resources included factors such as job autonomy (e.g., scheduling flexibility), organizational and family support, and personal adaptability. In particular, workload has been associated with negative outcomes such as increased stress, emotional exhaustion [66], and diminished well-being [53].

According to the JD-R model, job resources play a motivational role, fostering work engagement and positive outcomes—such as WLB—by providing employees with additional resources such as coping strategies. Conversely, excessive job demands—such as workload—can negatively influence individual resources, impact well-being, decrease job satisfaction, and enhance work–life conflict (WLC) [67,68].

Grounded in this theoretical framework, the present study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Workload mediates the relationship between cognitive demands of flexible work (i.e., structuring of work tasks, planning of working times, planning of working places, coordinating with others) and work–life conflict.

2.5. Perceived Organization Support as a Protective Factor in Flexible Work Settings in the Mediated Relationship Between Cognitive Demands of Flexible Work and Work–Life Conflict

The evolving model of flexible work aims to align employees’ needs with organizational goals; however, this alignment is only effective when flexible arrangements are properly structured, regulated, and supported [69]. To be beneficial, flexibility must be adapted to individuals’ needs and family conditions [70,71]. Therefore, organizational interventions play an essential role in transforming flexibility into sustainable practice. From this point of view, organizations should offer additional resources that enable employees to manage the challenge posed by flexible work arrangements [72,73]. Perceived organizational support (POS) refers to employees’ perception that their organization values their needs and well-being. A recent literature review [74] found that POS positively influences employees’ attitudes, behaviors, and performance [75], and job satisfaction [76]. Furthermore, POS has been considered as a protective factor that buffers the negative impacts of job demands [77,78]. Notably, recent research by Petitta and Ghezzi [38], highlights a curvilinear relationship between flexible work arrangements and social support. Given these findings, the workload in the relationship between CDFW and WLC may be moderated by different levels of POS. The literature consistently shows that employees who perceive high levels of POS report greater well-being, enhanced work–life balance [79], and reduced work-to-family conflict [30]. POS has been positively linked to well-being and job satisfaction [80], has demonstrated a positive influence on WLB [81], and is associated with lower levels of distress [82,83]. As an organizational resource, POS provides employees with the instrumental support and additional resources needed to manage work-family conflict [31]. Within the JD-R model, POS can strengthen the positive effects of challenge demands—such as CDF-by helping employees gain resources and promoting adaptive coping strategies. Conversely, high POS may also reduce the negative effects of workload and weaken the positive relationship between CDFW (when viewed as a personal demand) and WLC.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Perceived organizational support moderates the mediated relationship between cognitive demands of flexible work (and its subdimensions) and employees’ work–life conflict through workload.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Participants

This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (approval number 007669, dated 3 December 2024). A convenience sampling method was employed, involving only employees who worked in a flexible work arrangement. Specifically, in the Italian public sector, employees are permitted to work partially under flexible conditions, in accordance with the Ministerial Decree of 8 October 2021. Participants were invited to complete an anonymous online questionnaire, which included measures of the study constructs, socio-demographic and work-related information. Participation was voluntary; employees were informed about the main aim of the study and provided informed consent before participation. Data were collected in 2023. The sample was composed of 419 Italian public employees of whom 248 were men (59.2%) and 171 were women (40.8%). The participants had a mean age of 47.62 years (SD = 9.70). On average, they reported 17.78 years (SD = 9.40) of experience in public administration and a mean weekly working time of 35.08 h (SD = 8.17).

3.2. Measures

All the measures used in this study have been previously validated in research conducted in Italy. Participants responded to items using a 5-point Likert scale.

CDFW was evaluated using a 16-item scale [47], which encompasses four dimensions: structuring of work tasks; planning of working times; planning of working places; and coordinating with others. Example items for each dimension include: “My job requires me to monitor the progress of my work on my own”, for the structuring of work tasks; “Due to the flexible schedule, I have to make sure to plan time for breaks”, for planning of working times; “At work, I have to plan where to work on certain tasks, because I can execute some tasks better in certain places”, for planning of working places; “My job often requires me to come to an agreement with other people regarding a common approach” for coordinating with others. Participants indicated their agreement with each item on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree).

Work–life conflict was assessed using two items from Di Tecco et al. [84]: “The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life”, and “The demands of my family or partner interfere with my work”. Responses were given on a 5-point scale ranging from Never (=1) to Always (=5).

Workload was assessed using four items from the cognitive subscale of the Job Content Questionnaire [85]. Example items were: “I have too much work to do”, and “My job requires me to work harder than usual to meet a deadline”. Participants rated the frequency of each item from Never (=1) to Very often (=5).

Perceived organizational support was evaluated through the Survey of Perceived Organizational Support [86]. The scale comprised eight items. Respondents rated their agreement with each statement on a five-point scale ranging from not at all (=1) to completely (=5).

3.3. Control Variables

Age, gender, duration of employment in PA, and weekly working hours were included in the model as control variables to account for their potential effect on workload and work–life conflict. Categorical coding was applied as follows: gender (1 = male, 2 = female, 3 = other); age (1 = 18–34 years, 2 = 35–54 years, 3 = 55 years and older); weekly working hours (1 = 3–18 h, 2 = 19–34 h, 3 = more than 35 h); and the duration of employment (1 = 0–14 years; 2 = 15–29 years; 3 = 30 years or more). All the participants had at least one dependent child.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 25 and AMOS 23.0. To test the hypothesized relationships, including mediation (H1) and moderated mediation (H2), we employed the percentile bias-corrected bootstrap method with 5000 resamples and 95% confidence intervals. The mediation analysis tested whether workload mediated the relationship between CDFW and WLC. The moderated mediation analysis examined whether POS moderated the indirect effect of CDFW on WLC via workload.

Preliminarily analyses were conducted to assess data distribution, detect missing values, identify potential imputation errors, and examine the presence of outliers. Subsequently, the measurement model was evaluated through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to assess the validity and reliability of the latent constructs.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Evaluation and Statistical Assumptions

Factor loadings ranged from 0.603 to 0.858, above the recommended threshold of 0.50. Model fit indices indicated an adequate fit to the model: (χ2 = 596.920, df = 231, p = 0.000, χ2/df = 2.467; CFI = 0.940; TLI = 0.929; RMSEA = 0.059; SRMR = 0.066). Internal consistency was supported, with composite reliability (CR) values ranging from 0.691 to 0.910, and Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients ranging from 0.681 to 0.927. Convergent validity was confirmed, as all the average variance extracted (AVE) values were above the acceptable threshold of 0.50. No issues of multicollinearity were detected, with all Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values below the standard cutoff of 2. Detailed results for CR, AVE, and VIF are reported in Table 1. Multivariate outliers were identified using the Mahalanobis distance. One potential multivariate outlier was identified, with a Mahalanobis distance of 30.01, exceeding the critical chi-square value of 24.32 (for six variables at p < 0.001). However, the change in standardized DFFIT remained below the absolute threshold of 0.146 (calculated as 3 divided by the square root of the sample size), indicating that the outlier did not significantly influence the overall results. No concerns regarding multivariate normality were observed, as the average Mahalanobis distance squared was 56.00, which falls below Mardia’s index cutoff of 98. Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which confirmed that the square root of the AVE for each construct was greater than its correlations with other constructs (see Table 2). To assess the common method bias (CMB), Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The exploratory factor analysis showed that no single factor accounted for a dominant proportion of variance, with the first factor explaining only 28.55% of the total variance, suggesting that CMB was not a serious concern. Based on the validated measurement model, observed variables for each corresponding latent factor were aggregated into composite scores. These scores were then used for structural model testing, computing descriptive statistics (means, standard deviation), and correlations.

Table 1.

Average Extracted Variance (AVE), Composite Reliability (CR), and Cronbach’s Alpha for the Study Constructs.

Table 2.

Assessments of Discriminant Validity: Correlations Between Constructs and Square Root of AVE (Bolded on the Diagonal).

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlation

As reported in Table 3, the results showed significant positive correlations between each subdimension of cognitive demands of flexible work, work–life conflict, and workload. Among the socio-demographic and work-related variables, weekly working hours were positively correlated with the structuring of work tasks and negatively correlated with the planning of working times. Additionally, age was negatively correlated with both the planning of workplace and work–life conflict.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables (N = 484).

4.3. Open Research Questions and Hypothesis Testing

To address the open research questions and test the proposed hypotheses, the study assessed three path models using bootstrapping with 5000 resamples. The first model examined the direct relationship between CDFW and WLC, the second model tested whether workload mediated the relationship between the subdimensions of CDFW and WLC. The third model tested whether POS moderated the indirect relationship between CDFW and WLC. All models included control variables.

4.3.1. Direct Effects

The results revealed that the planning of working place dimension of CDFW had a significant positive relationship with WLC (β = 0.358; CI = 0.245 to 0.471). In contrast, structuring of work tasks (β = 0.064; CI = −0.044 to 0.162), planning of working time (β = 0.025; CI = −0.086 to 0.135), and coordinating with others (β = 0.040; CI = −0.060 to 0.136) did not show significant effects on work–life conflict. These findings indicate that higher levels of cognitive demands related to planning of working place are related with greater interference between work and personal life. Regarding workload, planning of working time was negatively related (β = −0.114; CI = 0.168 to 0.420), while planning of working place was positively related (β = 0.302; CI = 0.176 to 0.420) as well as structuring of work tasks (β = 0.130; CI = 0.026 to 0.235). This indicates that greater effort in planning the working place is related with higher workload, whereas increased planning of working time is related with lower workload. Neither the structuring of work tasks planning of working time (β = −0.114; CI = −0.228 to 0.003) nor coordinating with others (β = 0.114; CI = −0.006 to 0.225) showed significant relationship with workload. Similarly, age, gender, and duration of employment in PA were not significantly related to WLC (p > 0.05). However, weekly working hours had a significant positive influence on WLC (β = 0.095; CI = 0.004 to 0.184), indicating that increased working hours are linked to greater interference between work and personal life. Furthermore, gender (β = 0.095; CI = 0.008 to 0.186) and weekly working hours (β = 0.127; CI = 0.031 to 0.227) were significantly and positively related to workload. Specifically, female employees and those working longer hours reported higher levels of workload. Conversely, age and duration of employment in public administration were not significantly related to workload (p > 0.05). The model explained the 22.6% of the variance in work–life conflict (R-square = 0.226) and 18.2% of the variance in workload.

To summarize, these results answer our two main open research questions concerning the direct effects of CDFW on WLC and workload. The analyses show that planning the working place uniquely increases both work–life conflict and workload, while the structuring of work tasks increases workload without affecting work–life conflict. Other cognitive demands and demographic factors were largely unrelated, with the exception for weekly working hours, which were related to higher levels of workload and conflict, and gender, which was related to workload. The details of the results are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Direct Effects of Socio-Demographic Variables and Work Variables and the Cognitive Demands of Flexible Work subdimensions (Structuring of WTs, Planning of WTs, Planning of WPs, Coordinating with Others) on work–life conflict (WLC) and Workload (N = 419).

4.3.2. Mediating Effects

The results revealed that the indirect effects of CDFW on WLC via workload were significant; specifically, structuring of work tasks (β = 0.030; CI = 0.077 to 0.061), planning of working time (β = −0.0026; CI = −0.064 to −0.001), planning of working place (β = 0.069; CI = 0.033 to 0.117), and coordinating with others (β = 0.0026; CI = 0.000 to 0.059). Notably, the indirect effect of planning of working time on WLC through workload was negative, and it was significantly negatively related to workload (β = −0.123; p = 0.027). The R2 value for workload was 0.182, and for WLC, 0.268. The total effect was significant only for the planning of the working place (β = 0.358; CI = 0.242 to 0.470). These results indicated that the relationship between the planning of the working place and WLC is partially mediated by workload. In contrast, the relationships of the other subdimension of CDFW on WLC were fully mediated by workload. Detailed results are presented in Table 5. Regarding socio-demographic and work-related variables, none were significantly related to WLC (p > 0.05); however, female employees reported higher levels of workload (β = 0.109; CI = 0.022 to 0.199). The mediating effect was further examined using a multigroup analysis based on age and job grade. Specifically, we compared individuals below and above the average age and managers versus employees. The comparison between the unconstrained model and the model with constrained structural weights did not reveal significant differences for ages (df = 17; χ2 = 10.570; p = 0.878) or for job grade (df = 17; χ2 = 21.251; p = 0.215).

Table 5.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables Direct, Indirect, and Total Effect Effects of Cognitive Demands of Flexible Work (structuring of work (SW), planning of working time (PT), planning of working place (PP), and coordinating with others (CO) on work–life conflict (WLC) via Workload (WO), and total effects (N = 419). Note: BC = Bias Corrected; CI = Confidence Interval; LLCI = Lower Limit CI; ULCI = Upper Limit CI.

These findings highlight the central mediating role of workload in translating specific cognitive demands—especially those involving the structuring of working tasks, the planning of working time, the planning of working place, and the coordination with others—into work–life conflict. The impact of planning one’s work location on WLC appears to have both indirect and direct effects. These relationships did not vary across age or grade. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

4.3.3. Moderated Mediation Effects

The index of moderated mediation was non-significant for all conditional indirect effects between CDFW and WLC through POS. This indicates that the magnitude of the mediating effects of workload between CDFW and WLC did not significantly vary across different levels of POS. Specifically, the beta coefficients for the conditional indirect effects of each CDFW subdimension on WLC through POS were as follows: structuring of working tasks (β = −0.014; p = 0.222), planning of working time (β = −0.023; p = 0.052), planning of working place (β = 0.02; p = 0.867), and coordinating with others (β = −0.014; p = 0.200).

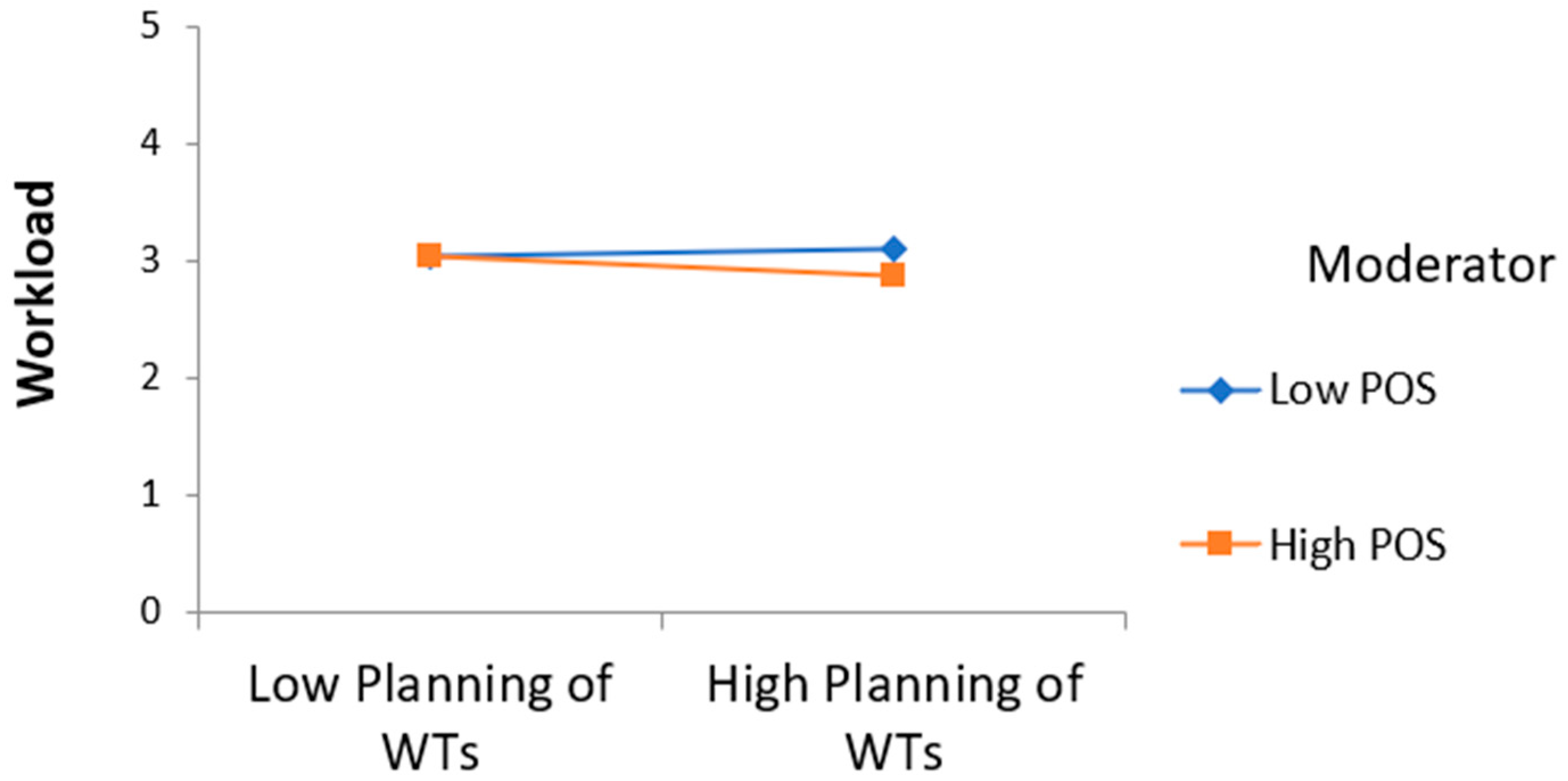

Given the non-significant conditional indirect effects, a simple moderation analysis was conducted to further explore the relationship between CDFW subdimensions, POS, and workload. The results revealed that POS significantly moderated only the relationship between planning of working time and workload (β = −0.102; p = 0.024). Specifically, at higher levels of POS, the negative relationship between planning of working time and workload was significant (β = −0.191; p = 0.004), and at lower levels of POS, this negative relationship was not significant (β = −0.019; p = 0.778). Figure 2 illustrates the results.

Figure 2.

Interaction Between Planning of Working Times (WTs) and Perceived Organizational Support (POS) as it Relates to Workload Explanation.

In summary, this analysis suggests that POS functions as a protective factor only when employees face cognitive demands related to working time planning. Under conditions of low organizational support, these demands increase perceived workload, while when support is high, the same demands appear less burdensome. Therefore, Hypothesis H2 was not supported.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution and Conclusions

The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between the cognitive demands of flexible work (CDFW) and its subdimensions (structuring of work tasks, planning of working time, planning of working place, coordinating with others) and work–life conflict (WLC), with a focus on the mediating role of workload. While the overall model revealed significant relationships, these findings must be interpreted with caution due to the cross-sectional design, which limits any claims about directionality or causality. Despite this limitation, the analysis offers several important insights. More specifically, in line with this aim and the exploratory research questions, the findings showed a significant positive relationship between planning of the working place and WLC, a pattern not observed with the other subdimensions of cognitive demands of flexible work (i.e., structuring of work tasks, coordinating with others). This result partially aligns with previous studies that have shown the detrimental effects of cognitive demands on fatigue [21], work–life conflict [26,27], reduced well-being [17,18], and increased stress and workload [16]. However, these findings do not fully support the conceptualization of CDFW as potentially challenging demands, despite having been associated with positive outcomes [20,21,47]. Interestingly, three of the four subdimensions of CDFW are not statistically related to WLC. Several factors might explain why CDFW did not function as a set of challenging demands in this study. The literature highlights that flexible work arrangements increase employees’ responsibility for managing their time and tasks. This includes challenges in maintaining boundaries between work and personal life, a sense of constant connectivity, and in some cases, paradoxical well-being [17,18]. The cognitive demands associated with flexible work may blur the distinction between professional and personal life, which can worsen work–life conflict [26,27,28] and deplete personal resources required for goal achievement [29]. High cognitive demands, particularly those related to coordinating with others, planning the working place, and longer working hours [20], can also negatively influence job satisfaction, which may further influence WLC [53]. Flexible work arrangements inherently involve a paradox between differentiation and integration [87]. Differentiation refers to the specialization of subunits and teams (e.g., different aims and roles), enabling for greater environmental adaptation, autonomy, and flexibility. Conversely, integration involves aligning the differentiated subunit and teams (e.g., aims and roles) through shared standards, communication protocols, and collaborative norms, which help maintain coordination. CDFW supports individuals by enabling the integration of work and family roles and goals. This can support employees’ work–life balance, allowing them to tailor their work schedules and environment. However, it may also limit role differentiation. This limited differentiation can result in blurred role boundaries, Additionally, at the team level, CDFW can maintain structural differentiation based on where work is performed, which may hinder integration across roles. This can lead to increased coordination and communication challenges, placing a greater burden on individuals to self-manage the boundaries between their work and personal life. When employees work at different locations, it becomes more difficult to synchronize efforts and share responsibilities effectively [88]. Another factor may involve the discrepancy between perceived and actual working hours in flexible arrangements. In this study, the declared number of working hours was correlated with WLC, suggesting that the extended hours may play a role in driving conflict. Importantly, the findings reinforce the value of considering mediating mechanisms, specifically workload, in understanding the relationship between CDFW and WLC. Structuring of working tasks and coordinating with others were both indirectly and positively related to WLC via workload, whereas planning of working time showed a negative relationship, indicating a full mediation effect. In contrast, planning of working place showed both a direct positive association with WLC and an indirect negative relationship via workload, suggesting a partial mediation. These findings offer partial support for Hypothesis 1 (H1) and are consistent with the Job Demand-Resources model [23], which posits that job demands negatively affect work-related outcomes and can reinforce one another. Within the context of flexible work, cognitive demands such as managing one’s schedule, organizing tasks, selecting an appropriate workplace, and coordinating with colleagues often require additional effort and time. This may result in an increased workload, higher level of work–life interference [26], and psychological conflict [46]. Notably, among all CDFW subdimensions, planning the working place did not contribute to increased workload. Instead, it directly interfered with personal life, possibly due to the mental and contextual demands of constantly changing work environments or negotiating workspace suitability and time. This continual negotiation of where and how to work can, thus, blur role boundaries and increase role conflict, directly undermining work–life balance even in the absence of increased workload. However, the analysis did not support Hypothesis 2 (H2). The proposed moderated mediation role of POS in the relationship between the cognitive demands of flexible work and workload was not confirmed. This unexpected result diverges from prior research suggesting that POS can buffer the negative effect of job demands [74] and from studies reporting a curvilinear relationship between flexible work arrangements and social support [38], or between POS and reduced WLC [15,30,31]. An explanation for this discrepancy lies in the limited variability of POS values within the sample (M = 3.08; SD = 0.92), which may have reduced the statistical power to detect moderated mediation effects. However, beyond statistical considerations, it is also plausible that the buffering role of POS is not uniformly applicable across all types of cognitive demands related to flexible work, because these demands may be influenced by contextual and personal factors. Indeed, the study did identify a moderating effect of POS on the relationship between planning of working time and workload, suggesting that POS may still play a targeted buffering role under specific work conditions and flexible work configurations. As a pilot and exploratory investigation, this study contributes to the growing literature by providing a more differentiated view of the interplay between CDFW, workload, and WLC. It extends current knowledge by highlighting workload as a mediating mechanism and POS as a moderator under specific conditions, while underscoring the relative importance of organizational support compared to workspace configuration and time management flexibility in shaping employees’ experience in flexible work environments.

5.2. Practical and Social Implications

An improved understanding of the advantages and drawbacks of flexible work arrangements can also offer both practical and social implications. Organizations should be aware that granting flexibility alone does not necessarily reduce work–life conflict; rather, if not properly supported, it may increase employees’ mental workload and strain. Indeed, granting employees greater autonomy in flexible work arrangements may come with increased responsibility and specific cognitive challenges. In the absence of direct supervision, employees are expected to independently plan, prioritize, and manage their tasks. This requires proficiency in goal setting, progress monitoring, and strategic adaptation—competencies that may also elevate workload and psychological strain. To address these challenges, organizations should implement targeted programs, such as time management training and digital planning tools, to help employees manage the demands of flexible work effectively. Additionally, the cognitive demands of flexible working can blur boundaries between professional and private life, increase the risk of overwork, cause a continuous sense of being “on call”, and increase the psychological toll of autonomous work management. Moreover, since POS was found to buffer the impact of planning of working time on workload, investing in supportive practices can serve a protective role. Indeed, to promote a healthier life balance, organizations can support employees in managing the CDFW effectively. This includes helping them establish clear boundaries between work and personal life—such as defined start and end times—and encouraging the creation of dedicated physical workspaces. Organizations should also provide training in time management, focus and attention techniques, and multitasking reduction strategies. Furthermore, policies that ensure the right to disconnect, along with light but consistent supervisory strategies, should be adopted. For flexible work to be truly effective, it is not enough to provide autonomy alone: employees’ needs must be acknowledged, listened to, and actively supported. Practical support also involves equipping employees with the appropriate tools tailored to their specific needs and work environments, such as communication and collaboration tools for real-time interaction, task and project management tools, to support workload organization and deadlines management, and well-being tools, to facilitate participation in wellness programs. It is essential to differentiate these tools based on employees’ roles and preferences, ensuring that their voices are heard through regular feedback mechanisms. To address these challenges, organizations need to implement effective integration mechanisms, such as shared digital tools, clear communication practices, and cultural norms that foster collaboration. These strategies help maintain an appropriate balance between integration and differentiation at both individual and team levels [88]. Moreover, these strategies should be clearly communicated to both employees and managers, and, when appropriate, to family members who may be affected by remote work arrangements. Finally, organizations should be prepared to adapt their strategies to specific work locations, recognizing that remote work can look very different in a home office, a shared workspace, or a hybrid setup. Flexibility must be accompanied by structure, the right tools, and an organizational culture rooted in trust and well-being. Only then can flexibility translate into true work–life balance and sustainable productivity. Understanding the ambivalence of outcomes associated with flexible work demands is, therefore, essential. Doing so provides valuable practical insights for organizations aiming to develop family-friendly, supportive policies and equips them to help employees manage these arrangements in a healthy way [32]. Society stands to benefit from the findings of this study, as they offer insights into promoting a healthier balance between work and personal life. By identifying the cognitive demands and potential stressors associated with flexible work arrangements, this research can inform evidence-based policies aimed at reducing excessive workload and mitigating WLC. More specifically, the results guide the development of working time reduction strategies, such as shorter workweeks or task-based work models. Additionally, the findings highlight the importance of providing adequate policies for the structuring of working tasks and places.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Despite offering valuable insights, this study has several limitations that suggest consideration for future research studies. First, the study has a cross-sectional design that limits the possibility of inferring causal relationships among variables under study. Longitudinal studies are recommended to understand how CDFW can change after the work context is changed, and after having changed contextual variables in experimental studies. Second, while the sample size was statistically adequate, the generalizability of the findings is constrained. Future studies should aim to replicate and extend these findings using larger and more diverse samples, particularly across different public sector organizations, countries, cultural contexts, and high-demand work environments. In the present study, the average number of working hours in our sample is relatively low (M = 35) compared to other countries. This lower average workload may buffer the effect of CDFW on both workload and WLC. However, there is a substantial variability in working hours, as indicated by a high standard deviation (SD = 8.17), suggesting that the sample is diverse in terms of working time. This diversity partially supports the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, these results should be interpreted with caution and considered context-dependent. They offer valuable insights for work contexts where shorter workweeks are the norm or where there is growing policy interest in reducing working hours. To enhance generalizability, further studies should include samples from high-demand work environments or contexts with extended workweeks (e.g., 40 h or more) to further examine the applicability of these results. Notably, the conclusions drawn in our study are primarily based on findings from public administration settings and are, therefore, more directly relevant to government employees. However, the insights may also be extended to other organizations that share similar characteristics, such as hierarchical structures, a strong emphasis on accountability, or a service-oriented mission. That said, in order for the conclusions to be fully transferable across different types of enterprises, additional contextual factors should be taken into account. In particular, organizational culture plays a critical role in shaping how flexible work policies are designed and implemented. Future research should incorporate organizational culture into the statistical model to explore how variations in values, norms, and behaviors influence the outcomes of flexible work arrangements. Additionally, it would be valuable to consider individual differences (e.g., personality, different competencies, coping strategies) that may be included in a complex model as moderators. Another promising direction involves examining the specific characteristics of the work context to understand for whom and under what conditions CDFW can be resources or demands. Finally, further investigation is needed to understand the role of other forms of support, such as supervisor, family, and friend support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B., B.B., M.M. and S.D.S.; methodology, D.B.; validation, D.B., B.B., M.M., S.D.S. and S.M.; formal analysis, D.B.; resources, B.B.; data curation, D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B.; writing—review and editing, D.B., B.B., M.M., S.D.S. and S.M.; visualization, D.B.; supervision, D.B. and B.B.; project administration, B.B.; funding acquisition, B.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author received financial support for this paper from the Fondazione di Sardegna—Research Funding 2021—University of Cagliari. Title of the funded project “SEWED—Smart Engaging Work Environment Design”—CUP F73C22001370007.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kaunas University of Technology (M62022-18). This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (approval number 007669, dated 3 December 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CDFW | Cognitive Demands of Flexible Work |

| WLC | Work–Life Conflict |

| WLB | Work–Life Balance |

| POS | Perceived Organizational Support |

| WO | Workload |

References

- Chafi, M.B.; Hultberg, A.; Bozic Yams, N. Post-pandemic office work: Perceived challenges and opportunities for a sustainable work environment. Sustainability 2021, 14, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baadel, S.; Kabene, S.; Majeed, A. Work-life conflict costs: A Canadian perspective. Int. IJHRDM 2020, 20, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifrin, N.V.; Michel, J.S. Flexible work arrangements and employee health: A meta-analytic review. Work. Stress 2021, 36, 60–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langè, V.; Gastaldi, L. Coping Italian emergency COVID-19 through smart working: From necessity to opportunity. J. Mediterr. Knowl. 2020, 5, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niersbach, S. How flexible is paid work organized in the public sector before and during the COVID 19 pandemic? A qualitative study. Int. J. Home Econ. 2021, 14, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Tasrin, K.; Wahyuadianto, A.; Pratiwi, P.; Masrully, M. Evaluation study of the implementation of flexible working arrangement in public sector organization during Covid-19 pandemic. JBB 2021, 28, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda, S.; Ghersetti, E.; Girardi, D.; De Carlo, N.A.; Dal Corso, L. Smart working and online psychological support during the covid-19 pandemic: Work-family balance, well-being, and performance. InPACT 2021, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perevoznic, F.M.; Dragomir, V.D. Achieving the 2030 Agenda: Mapping the Landscape of Corporate Sustainability Goals and Policies in the European Union. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Z.; Wang, S. Do work-family initiatives improve employee mental health? Longitudinal evidence from a nationally representative cohort. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Rondon-Eusebio, R.F.; Geraldo-Campos, L.A.; Acevedo-Duque, Á. Job Satisfaction in Remote Work: The Role of Positive Spillover from Work to Family and Work–Life Balance. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, D. Employee satisfaction and use of flexible working arrangements. Work Employ. Soc. 2017, 31, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tleuken, A.; Turkyilmaz, A.; Sovetbek, M.; Durdyev, S.; Guney, M.; Tokazhanov, G.; Wiechetek, L.; Pastuszak, Z.; Draghici, A.; Boatca, M.E.; et al. Effects of the Residential Built Environment on Remote Work Productivity and Satisfaction during COVID-19 Lockdowns: An Analysis of Workers’ Perceptions. Build. Environ. 2022, 219, 109234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappegård, T.; Goldscheider, F.; Bernhardt, E. Introduction to the Special Collection on Finding Work-Life Balance: History, Determinants, and Consequences of New Bread-Winning Models in the Industrialized World. Demogr. Res. 2017, 37, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loredana, M.; Irimias, T.; Brendea, G. Teleworking During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Determining Factors of Perceived Work Productivity, Job Performance, and Satisfaction. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 23, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, M.; Abendroth, A.K. Flexible working and its relations with work-life conflict and well-being among crowdworkers in Germany. Work 2023, 74, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, B.; Prem, R.; Baumgartner, V.; Uhlig, L.; Korunka, C. Cognitive demands of flexible work. In Flexible Working Practices and Approaches: Psychological and Social Implications; Korunka, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccoli, G.; Tims, M.; Gastaldi, L.; Corso, M. The psychological experience of flexibility in the workplace: How psychological job control and boundary control profiles relate to the wellbeing of flexible workers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2024, 155, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; van der Lippe, T. Flexible working, work–life balance, and gender equality: Introduction. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 151, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uglanova, E.; Dettmers, J. Sustained effects of flexible working time arrangements on subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 19, 1727–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, B.; Bellini, D.; Batzella, F.; Mondo, M.; Pinna, R.; Galletta, M.; De Simone, S. Flexible Work in the Public Sector: A Dual Perspective on Cognitive Benefits and Costs in Remote Work Environments. Public. Pers. Manag. 2025, 54, 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlig, L.; Korunka, C.; Prem, R.; Kubicek, B. A two-wave study on the effects of cognitive demands of flexible work on cognitive flexibility, work engagement and fatigue. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 72, 625–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholze, A.; Hecker, A. The job demands-resources model as a theoretical lens for the bright and dark side of digitization. Comput. Human Behav. 2024, 155, 108177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; LePine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ruysseveldt, J.; Verboon, P.; Smulders, P. Job resources and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of learning opportunities. Work. Stress 2011, 25, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buruck, G.; Pfarr, A.L.; Penz, M.; Wekenborg, M.; Rothe, N.; Walther, A. The Influence of workload and work flexibility on work-life conflict and the role of emotional exhaustion. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofäcker, D.; König, S. Flexibility and work-life conflict in times of crisis: A gender perspective. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2013, 33, 613–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, H.; O’Connell, P.J.; McGinnity, F. The impact of flexible working arrangements on work–life conflict and work pressure in Ireland. GWO 2009, 16, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra, V.; Singh, S.; Dutta, T. Embracing Flexibility Post-COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Flexible Working Arrangements Using the SCM-TBFO Framework. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2023, 25, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayfur Ekmekci, O.; Xhako, D.; Metin Camgoz, S. The Buffering Effect of Perceived Organizational Support on the Relationships Among Workload, Work-Family Interference, and Affective Commitment: A Study on Nurses. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 29, e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wattoo, M.A.; Zhao, S.; Xi, M. Perceived organizational support and employee well-being: Testing the mediatory role of work–family facilitation and work–family conflict. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2018, 12, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, R.; Nag, D.; Rani, R.; Prasad, K. Association Among Remote Working and Work-Life Balance with Mediating Effect of Social Support: An Empirical Study Concerning Migrated Employees in Hyderabad, During COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Law Sustain. Dev. 2023, 11, e425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çivilidağ, A.; Durmaz, Ş. Examining the relationship between flexible working arrangements and employee performance: A mini review. Front Psychol. 2024, 4, 1398309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, B.A.C.; van Triest, S.P.; Coers, M.; Wtenweerde, N. Managing Flexible Work Arrangements: Teleworking and Output Controls. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwudi, C.G.; Ukegbu, O.P.; Anthony, N.O. Flexible Work Arrangement and Employees’ Performance during COVID-19 Era in Selected Micro Finance Banks in Enugu State. Asian J. Econ. Financ. Manag. 2022, 4, 355–360. Available online: https://www.journaleconomics.org/index.php/AJEFM/article/view/137 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D. Does Remote Work Flexibility Enhance Organization Performance? Moderating Role of Organization Policy and Top Management Support. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xie, T. Double-Edged Sword Effect of Flexible Work Arrangements on Employee Innovation Performance: From the Demands–Resources–Individual Effects Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitta, L.; Ghezzi, V. Disentangling the Pros and Cons of Flexible Work Arrangements: Curvilinear Effects on Individual and Organizational Outcomes. Economies 2025, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, N.F.A.; Udeh, N.C.A. Combating Burnout in the IT Industry: A Review of Employee Well-Being Initiatives. Int. J. Appl. Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 6, 567–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Pan, Z.; Luo, Y.; Guo, Z.; Kou, D. More Flexible and More Innovative: The Impact of Flexible Work Arrangements on the Innovation Behavior of Knowledge Employees. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1053242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, S.; Hirsh, C.E. “Family-Friendly” Jobs and Motherhood Pay Penalties: The Impact of Flexible Work Arrangements Across the Educational Spectrum. Work Occup. 2019, 46, 3–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.C.; Hünefeld, L. Challenging Cognitive Demands at Work, Related Working Conditions, and Employee Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Boyar, S.L.; Maertz, C.P. Spoiled for Choice? When Work Flexibility Improves or Impairs Work–Life Outcomes. J. Manag. 2023, 51, 1730–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Dey, S.; Nguyen, H.; Groth, M.; Joyce, S.; Tan, L.; Glozier, N.; Harvey, S.B. A Review and Agenda for Examining How Technology-Driven Changes at Work Will Impact Workplace Mental Health and Employee Well-Being. Aust. J. Manag. 2020, 45, 402–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, V.C.; Prem, R.; Uhlig, L.; Korunka, C.; Kubicek, B. Employer-Oriented Flexible Work in Health Care: A Diary Study on the Resulting Cognitive Demands and Their Relationship with Work–Home Outcomes. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2023, 97, 579–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhéaume, A. Job Characteristics, Emotional Exhaustion, and Work–Family Conflict in Nurses. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 44, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prem, R.; Kubicek, B.; Uhlig, L.; Baumgartner, V.; Korunka, C. Development and Initial Validation of a Scale to Measure Cognitive Demands of Flexible Work. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 679471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brian, K.E.; Beehr, T.A. So Far, So Good: Up to Now, the Challenge Hindrance Framework Describes a Practical and Accurate Distinction. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 962–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, M.; Grant, C.A.; Tramontano, C.; Michailidis, E. Systematically Reviewing Remote Eworkers’ Well-Being at Work: A Multi-Dimensional Approach. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, A.; Yung, M.; Somasundram, K.G.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B.; Oakman, J.; Yazdani, A. Working in the Digital Economy: A Systematic Review of the Impact of Work from Home Arrangements on Personal and Organizational Performance and Productivity. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunaryo, S.; Sawitri, H.S.R.; Suyono, J.; Wahyudi, L. Flexible Work Arrangement and Work-Related Outcomes during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Local Governments in Indonesia. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2022, 20, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.W.; Barber, L.K. Psychologically Detaching Despite High Workloads: The Role of Attentional Processes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettmers, J.; Bredehöft, F. The Ambivalence of Job Autonomy and the Role of Job Design Demands. Scand. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2020, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, J.A.; LePine, M.A. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poethke, U.; Klasmeier, K.N.; Radaca, E.; Diestel, S. How modern working environments shape attendance behaviour: A longitudinal study on weekly flexibilization, boundaryless work and presenteeism. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2023, 96, 524–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.R.; Adams, G.A. The differential role of job demands in relation to nonwork domain outcomes based on the challenge-hindrance framework. Work. Stress 2020, 34, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhang, P. The influence of challenge-hindrance stressor on high-tech R&D staffs’ subjective career success: Result of career self-efficacy and organizational career management. Manage. Rev. 2018, 30, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, B.; Baumgartner, V.; Prem, R.; Sonnentag, S.; Korunka, C. Less detachment but more cognitive flexibility? A diary study on outcomes of cognitive demands of flexible work. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2022, 29, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, A.; Saufi, R.; Devadhasan, B.; Meyer, N.; Vetrivel, S.; Magda, R. The Mediating Role of Person-Job Fit between Work-Life Balance (WLB) Practices and Academic Turnover Intentions in India’s Higher Educational Institutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, A.O.; Olive, E.U.; Babatunde, A.H.; Nanle, M. Work-life balance and employee performance: A study of selected deposit money banks in Lagos State, Nigeria. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 5, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, P.; Hoque, M.E.; Jannat, T.; Emely, B.; Zona, M.A.; Islam, M.A. Work-Life Balance, Job Satisfaction, and Job Performance of SMEs Employees: The Moderating Role of Family-Supportive Supervisor Behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 906876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirmohammadi, M.; Chan Au, W.; Beigi, M. Antecedents and Outcomes of Work-Life Balance While Working from Home: A Review of the Research Conducted During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2022, 21, 473–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervasti, J.; Seppälä, P.; Olin, N.; Kalavainen, S.; Heikkilä, H.; Aalto, V.; Kivimäki, M. Effectiveness of a workplace intervention to reduce workplace bullying and violence at work: Study protocol for a two-wave quasi-experimental intervention study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e053664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, D.S.; Syahrizal. The Effect of Work-Family Conflict and Workload on Work-Life Balance: The Moderating Role of Family Supportive Supervisor Behavior and Coworker Support. IJEBSS 2025, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natanael, K.; Iman Kalis, M.C.; Daud, I.; Rosnani, T.; Fahruna, Y. Workload and working hours effect on employees’ work-life balance mediated by work stress. Enrich. J. Manag. 2023, 13, 3110–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, C.; Patwardhan, M. Flexible working arrangement and job performance: The mediating role of supervisor support. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2021, 72, 1221–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, D.; Fan, W. Workplace flexibility, work–family interface, and psychological distress: Differences by family caregiving obligations and gender. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2023, 18, 1825–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, A. Flexible work arrangements and its impact on Work-Life Balance. Manag. Insight 2022, 18, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Taie, M.; Khattak, M.N. The impact of perceived organizational support and human resources practices on innovative work behavior: Does gender matter? Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1401916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.Y.; Elahi, N.S.; Abid, G.; Ashfaq, F.; Ilyas, S. Impact of Perceived Organizational Support on Work Engagement: Mediating Mechanism of Thriving and Flourishing. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. Perceived Organizational Support: A Literature Review. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 2019, 9, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, R.A.; Pusparini, E.S. The Effect of Flexible Work Arrangement and Perceived Organizational Support on Employee Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Employee Engagement. In Proceedings of the 6th Global Conference on Business, Management, and Entrepreneurship, Nice, France, 17–19 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, C.; Galvão, A.R.; Marques, C.S. How Perceived Organizational Support, Identification with Organization and Work Engagement Influence Job Satisfaction: A Gender-Based Perspective. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, B.; Mondo, M.; De Simone, S.; Pinna, R.; Galletta, M.; Pileri, J.; Bellini, D. Enhancing Productivity at Home: The Role of Smart Work and Organizational Support in the Public Sector. Societies 2024, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lartey, J.K.S.; Amponsah-Tawiah, K.; Osafo, J. The moderating effect of perceived organizational support in the relationship between emotional labour and job attitudes: A study among health professionals. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, N.; Yan, Z.; Othman, R. The moderating effect of perceived organizational support: The impact of psychological capital and bidirectional work-family nexuses on psychological wellbeing in tourism. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1064632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maan, A.T.; Abid, G.; Butt, T.H.; Ashfaq, F.; Ahmed, S. Perceived organizational support and job satisfaction: A moderated mediation model of proactive personality and psychological empowerment. Futur. Bus. J. 2020, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtuluş, E.; Yıldırım Kurtuluş, H.; Birel, S.; Batmaz, H. The Effect of Social Support on Work-Life Balance: The Role of Psychological Well-Being. IJCER 2023, 10, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Kachi, Y.; Eguchi, H.; Watanabe, K.; Arai, Y.; Iwata, N.; Tsutsumi, A. Workplace Social Support and Reduced Psychological Distress: A 1-Year Occupational Cohort Study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 64, e700–e704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sconfienza, C.; Lindfors, P.; Lantz Friedrich, A.; Sverke, M. Social support at work and mental distress: A three-wave study of normal, reversed, and reciprocal relationships. J. Occup. Health. 2019, 61, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Tecco, C.; Ronchetti, M.; Russo, S.; Ghelli, M.; Rondinone, B.M.; Persechino, B.; Iavicoli, S. Implementing Smart Working in Public Administration: A follow up study. Med. Lav. 2021, 112, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Taris, T.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Schreurs, P.J. A multigroup analysis of the job demands-resources model in four home care organizations. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2003, 10, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistelli, A.; Mariani, M.G. Supporto organizzativo: Validazione della versione Italiana della Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (versione a 8 item). G. Ital. Di Psicol. 2011, 38, 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, P.R.; Lorsch, J.W. Differentiation and integration in complex organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1967, 12, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manole, E.C.; Curseu, P.L.; Trif, S.R. The Differentiation–Integration Paradox of Hybrid Work: A Focus Group Exploration of Team and Individual Mechanisms. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).