Green HRM’s Effect on Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior and Green Performance: A Study in the Portuguese Tourism Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

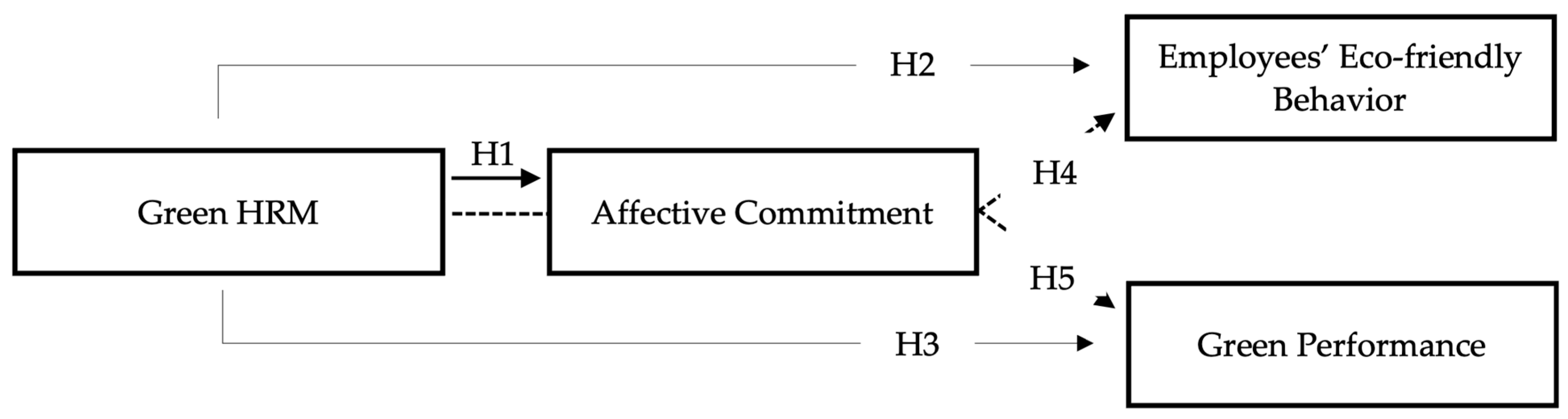

- Objective 1—to understand the impact of GHRM practices on employee’s eco-friendly behavior;

- Objective 2—to understand the impact of GHRM practices on green performance;

- Objective 3—to clarify the existence of the mediation effect of workers’ affective commitment over the relation between GHRM practices on employees’ eco-friendly behavior and green performance.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Green HRM and Affective Commitment

2.2. Green HRM and Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior

2.3. Green HRM and Green Performance

2.4. Mediating Role of Affective Commitment

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Green HRM

3.4. Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior

3.5. Affective Commitment

3.6. Green Performance

3.7. Demographic Variables

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Study Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

6.2. Theoretical Contributions and Implications of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- York, J.G.; Vedula, S.; Lenox, M.J. It’s not easy building green: The impact of public policy, private actors, and regional logics on voluntary standards adoption. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 1492–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch’ng, P.C.; Cheah, J.; Amran, A. Eco-innovation practices and sustainable business performance: The moderating effect of market turbulence in the Malaysian technology industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrutha, V.N.; Geetha, S.N. A systematic review on green human resource management: Implications for social sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Jiang, K.; Tang, G. Leveraging green HRM for firm performance: The joint effects of CEO environmental belief and external pollution severity and the mediating role of employee environmental commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 61, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Z.; Khan, I.U.; Islam, T.; Sheikh, Z.; Naeem, R.M. Do green HRM practices influence employees’ environmental performance? Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1061–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.M.; Phetvaroon, K. The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Jackson, S.E. HRM institutional entrepreneurship for sustainable business organizations. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Gomes, D.R.; Ortega, E.; Gomes, G.P.; Semedo, A.S. The Impact of Green HRM on Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior: The Mediator Role of Organizational Identification. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazlurrahman, H.; Rahman, M.F.W.; Diyah, I.; Arifah, C. Green Human Resource Management in the Hospitality Sector: A Systematic Literature Review. BISTIC Bus. Innov. Sustain. Technol. Int. Conf. 2021, 103, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, I.; Umrani, W.A. The impact of ethical leadership style on job satisfaction: Mediating role of perception of green HRM and psychological safety. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Greening the hospitality industry: How do green human resource management practices influence organizational citizenship behavior in hotels? A mixed-methods study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, N.Y.; Farrukh, M.; Raza, A. Green human resource management and employees pro-environmental behaviours: Examining the underlying mechanism. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.Y.; Tanveer, M.I.; Ramayah, T.; Kumar, S.C.; Saputra, J.; Faezah, J.N. Perceived green human resource management among employees in manufacturing firms. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 23, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Ullah, K.; Khan, A. The impact of green HRM on green creativity: Mediating role of pro-environmental behaviors and moderating role of ethical leadership style. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 33, 3789–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, K.; Kim, W.G.; Garcia, R.F. Top management green commitment and green intellectual capital as enablers of hotel environmental performance: The mediating role of green human resource management. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Jabbour, C.J.; Muller-Camen, M.; Redman, T.; Wilkinson, A. Contemporary developments in Green (environmental) HRM scholarship. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, S.M.; Al Bakri, A.A.; Elbanna, S. Leveraging “green” human resource practices to enable environmental and organizational performance: Evidence from the Qatari oil and gas industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 164, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R.; Armeli, S. Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C.; de Winne, S.; Sels, L. The influence of line managers and HR department on employees’ affective commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 1618–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkhoff, B. Ignoring commitment is costly: New approaches establish the missing link between commitment and performance. Hum. Relat. 1997, 50, 701–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behaviour. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 2nd ed.; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson Hall: Chicago, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Commitment: Exploring Multiple Mediation Mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.G.; Shore, L.M.; Griffeth, R.W. The role of perceived organizational support and supportive human resource practices in the turnover process. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muisyo, P.K.; Qin, S. Enhancing the FIRM’S green performance through green HRM: The moderating role of green innovation culture. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaprasad, B.S.; Lakshminarayanan, S.; Pai, Y.P. The relationship between developmental HRM practices and voluntary intention to leave among IT professionals in India: The mediating role of affective commitment. Ind. Commer. Train. 2018, 50, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Promoting employee green behavior in the Chinese and Vietnamese hospitality contexts: The roles of green human resource management practices and responsible leadership. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 105, 103253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, C.L.Z.; Dubois, D.A. Strategic HRM as social design for environmental sustainability in organization. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 799–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Nájera, M.; Rivera-Martínez, J.G.; Hafkamp, W.A. An explorative socio-psychological model for determining sustainable behaviour: Pilot study in German and Mexican universities. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, K.L.; Dmitrieva, A.; Adriasola, E. Changing behaviour: Increasing the effectiveness of workplace interventions in creating pro-environmental behaviour change. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee green behavior: A theoretical framework, multilevel review, and future research agenda. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Green Human Resource Management and Employee Green Behaviour: An Empirical Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.J. Hotels’ environmental policies and employee personal environmental beliefs: Interactions and outcomes. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A.; Ahmad, B.; Kazmi, S. The effect of green human resource management on environmental performance: The mediating role of employee eco-friendly behavior. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 1725–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Altinay, L. Green HRM, environmental awareness and green behaviors: The moderating role of servant leadership. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Pathak, S.; Werner, S. When do international human capital enhancing practices benefit the bottom line: An ability, motivation, and opportunity perspective. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 784–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Nehles, A.C.; Van Riemsdijk, M.J.; Looise, J.K. Employee perceptions of line management performance: Applying the AMO theory to explain the effectiveness of line managers’ HRM implementation. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 52, 861–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Thanh, T.V.; Tučková, Z.; Thuy, V.T. The role of green human resource management in driving hotel’s environmental performance: Interaction and mediation analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hörisch, J.; Freeman, R.E. Business cases for sustainability: A stakeholder theory perspective. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wu, S.; Yang, K. An ecosystemic framework for business sustainability. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.; Bertassini, A.C.; dos Santos Ferreira, C.; do Amaral, W.A.N.; Ometto, A.R. Circular economy indicators for organizations considering sustainability and business models: Plastic, textile and electro-electronic cases. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragas, S.F.P.; Tantay, F.M.A.; Chua, L.J.C.; Sunio, C.M.C. Green lifestyle moderates GHRM’s impact on job performance. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2017, 66, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latan, H.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Wamba, S.F.; Shahbaz, M. Effects of environmental strategy, environmental uncertainty and top management’s commitment on corporate environmental performance: The role of environmental management accounting. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, S.C.; Ruangkanjanases, A. Understanding the antecedents and consequences of green human capital. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 2158244020988867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Fawehinmi, O.O. Green human resource management: A systematic literature review from 2007 to 2019. Benchmarking An Int. J. 2019, 27, 2005–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, S.; Subramanian, N.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Chong, T. Green human resource management and the enablers of green organisational culture: Enhancing a firm’s environmental performance for sustainable development. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenreich, B.; Ludeke-Freund, F.; Schaltegger, S. A stakeholder theory perspective on business models: Value creation for sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G.; Ferro, C.; Hogevold, N.; Padin, C.; Varela, J.C.S. Developing a theory of focal company business sustainability efforts in connection with supply chain stakeholders. Supply Chain Manag. An Int. J. 2018, 23, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C. How green are HRM practices, organizational culture, learning and teamwork? A Brazilian study. Indust. Commerc. Train. 2011, 43, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Hoang, H.T.; Phan, Q.P.T. Green human resource management: A comprehensive review and future research agenda. Int. J. Manpower 2020, 41, 845–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Huang, L. The impact of green transformational leadership, green HRM, green innovation and organizational support on the sustainable business performance: Evidence from China. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 2022, 35, 6121–6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababneh, O.M.A. How do green HRM practices affect employees’ green behaviors? The role of employee engagement and personality attributes. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 1204–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A.; Sanders, K.; Yustantio, J. High commitment HRM and organizational and occupational turnover intentions: The role of organizational and occupational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 1661–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, M.; Pringle, C.D. The missing opportunity in organizational research: Some implications for a theory of work performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababneh, O.M.A.; Awwad, A.S.; Abu-Haija, A. The association between green human resources practices and employee engagement with environmental initiatives in hotels: The moderation effect of perceived transformational leadership. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 20, 390–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.P.; Ribeiro, N.; Semedo, A.S.; Gomes, D.R. Authentic Leadership and Improved Individual Performance: Affective Commitment and Individual Creativity’s Sequential Mediation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 675749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semedo, S.; Coelho, A.; Ribeiro, N. The relationship between authentic leaders and employees’ creativity. What is the role of affective commitment and job resourcefulness? Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2018, 11, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberghe, C.; Bentein, K.; Panaccio, A. Affective commitment to organizations and supervisors and turnover: A role theory perspective. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 2090–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücel, I.; Ribeiro, N.; Gomes, D. Perceived Organisational Support and Employees’ Performance: The mediating role of Affective Commitment. Int. J. Manag. Enterp. Develop. 2020, 29, 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, D.; Ribeiro, N.; Santos, M. “Searching for gold” with sustainable human resources management and internal communication: Evaluating the mediating role of employer attractiveness for explaining turnover intention and performance. Admin. Sci. 2023, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katou, A.A.; Budhwar, P.S. Causal relationship between HRM policies and organisational performance: Evidence from the Greek manufacturing sector. Europ. Manag. J. 2010, 28, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvaas, B. An exploration of how the employee–organization relationship affects the linkage between perception of developmental human resource practices and employee outcomes. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, J.J.; Rupp, D.E.; Brockner, J. Taking a multifoci approach to the study of justice, social exchange, and citizenship behavior: The target similarity model. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 841–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarence, M.; Devassy, V.P.; Jena, L.K.; George, T.S. The effect of servant leadership on ad hoc schoolteachers’ affective commitment and psychological well-being: The mediating role of psychological capital. Int. Rev. Ed. 2021, 67, 305–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemmel, K.; Jønsson, T.S. Multiple afective commitments: Quitting intentions and job performance. Empl. Relat. 2014, 36, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Justice in social exchange. Sociol. Inq. 1964, 34, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Lepak, D.P.; Hu, J.; Baer, J.C. How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1264–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Wright, P.M. The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. Bootstrap methods: Another look at the jackknife. In Breakthroughs in statistics: Methodology and distribution; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 569–593. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Ribeiro, N.; Cunha, M.P.; Jesuino, J.C. How happiness mediates the organizational virtuousness and affective commitment relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 5, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, D.A.; Judd, C.M. Estimating the nonlinear and interactive effects of latent variables. Psychol. Bulletin 1984, 96, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, K.; Hossain, M.B.; Ahmad, F.; Ejaz, F.; Khan, H.G.A.; Dunay, A. Green human resource management practices to accomplish green competitive advantage: A moderated mediation model. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elziny, M. The Impact of Green Human Resource Management on Hotel Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior. Int. Acad. J. Fac. Tour. Hotel Manag. 2019, 5, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Sobaih, A.E.E.; Aliedan, M.; Azzaz, A.M.S. The effect of green human resource management on environmental performance in small tourism enterprises: Mediating role of pro-environmental behaviors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaei, A.; Nejati, M.; Yusoff, Y.M. Green human resource management. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1041–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, M.; Mihalache, O.R. How workplace support for the COVID-19 pandemic and personality traits affect changes in employees’ affective commitment to the organization and job-related well-being. Hum. Res. Manag. 2021, 61, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Maltin, E.R. Employee commitment and well-being: A critical review, theoretical framework, and research agenda. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.; Neves, J. Do applicant’s prior experiences influence attractiveness prediction? Manag. Res. 2010, 8, 824–840. [Google Scholar]

| MEAN | S.D. | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. GREEN HRM | 2.95 | 1.22 | (0.91) | - | - | - | 0.914 | 0.729 |

| 2. AFFECTIVE COMMITMENT | 4.09 | 0.974 | 0.430 ** | (0.96) | - | - | 0.958 | 0.884 |

| 3. ECO FRIENDLY BEHAVIOR | 4.43 | 0.669 | 0.243 ** | 0.117 * | (0.73) | - | 0.749 | 0.507 |

| 4. GREEN PERFORMANCE | 3.70 | 0.957 | 0.618 ** | 0.437 ** | 0.328 ** | (0.91) | 0.915 | 0.732 |

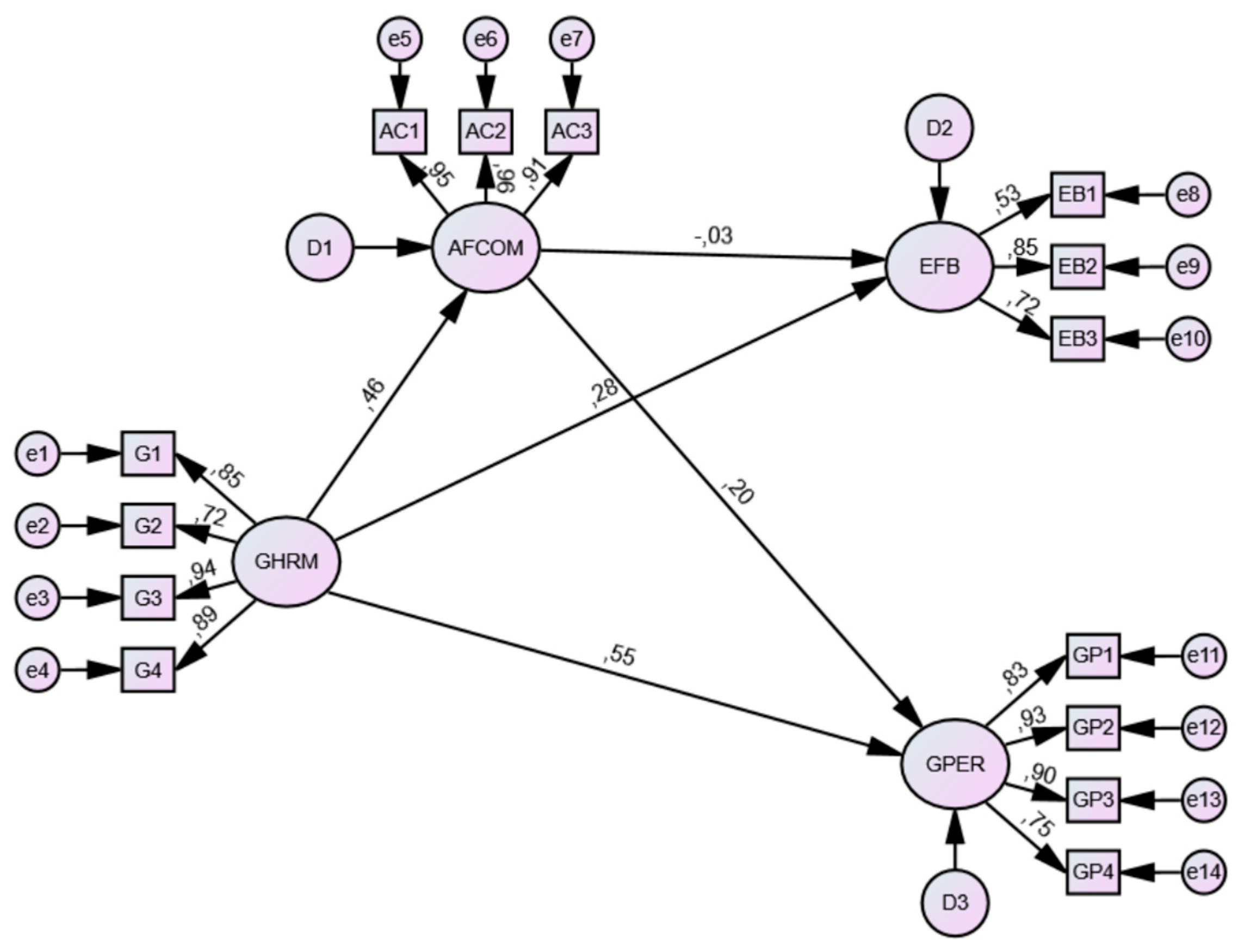

| Path | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| (T.E) | (D.E) | (I.E.) via Mediator | |

| GHRM—Eco-friendly behavior | 0.270; sig < 0.05 | 0.283; sig < 0.05 | −0.013; (n.s.) |

| GHRM—Green Performance | 0.646; sig < 0.05 | 0.554; sig < 0.05 | 0.091; sig < 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomes, D.R.; Ribeiro, N.; Gomes, G.; Ortega, E.; Semedo, A. Green HRM’s Effect on Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior and Green Performance: A Study in the Portuguese Tourism Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10005. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162210005

Gomes DR, Ribeiro N, Gomes G, Ortega E, Semedo A. Green HRM’s Effect on Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior and Green Performance: A Study in the Portuguese Tourism Sector. Sustainability. 2024; 16(22):10005. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162210005

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomes, Daniel R., Neuza Ribeiro, Gabriela Gomes, Eduardo Ortega, and Ana Semedo. 2024. "Green HRM’s Effect on Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior and Green Performance: A Study in the Portuguese Tourism Sector" Sustainability 16, no. 22: 10005. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162210005

APA StyleGomes, D. R., Ribeiro, N., Gomes, G., Ortega, E., & Semedo, A. (2024). Green HRM’s Effect on Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior and Green Performance: A Study in the Portuguese Tourism Sector. Sustainability, 16(22), 10005. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162210005