1. Introduction

Sustainable development is becoming a global priority and a key societal challenge [

1]. The concept plays an increasingly significant role in functioning economies and societies. Contemporary challenges such as the climate crisis, pandemics, and rapid population growth are receiving increasing attention [

2]. The potentially negative impact of the economy on the environment has raised concerns among practitioners and scholars of sustainability, sustainable development, and the environment and has led to a transition towards a sustainable economy in many countries [

3,

4]. It requires transforming the production and consumption models toward a decrease in the scale of environmental use, reducing the quantity of consumed non-renewable resources, and energy consumption [

5,

6,

7].

This raises a common interest in sustainable enterprises and commonly referred to as impact startups, which focus on tackling important social and environmental issues [

8,

9]. The International Labour Organization [ILO] strongly emphasizes the importance of sustainable enterprises, claiming that they are key to ensuring job and wealth creation, a just transition to environmental sustainability, and inclusive economies and societies. Around the world, companies and consumers are increasingly looking for products and services that have a positive impact on the community, the environment, and society [

10].

Achieving global sustainability requires local governments, citizens, local organizations, and private enterprises to work together to implement sustainable development strategies at the local level in the face of increasing pressure on businesses to be socially and environmentally responsible [

11,

12,

13,

14]. In this context, Roome and Cahill [

15], as well as Sharma and Ruud [

16], underline that promoting sustainable development requires that governments incorporate the social principles of justice and inclusiveness embedded in the concept of sustainable development into designing holistic policies that motivate and enable firms to develop more sustainable strategies. Thus, a “green” strategy should be adopted by the business sector to focus on sustainability, with greater attention paid to environmental and social concerns [

17,

18].

The current young generation is also facing environmental challenges and social problems, so their awareness and involvement will be key to solving these problems in the coming years. The European Economic and Social Committee stresses the need for a more inclusive governance model that actively involves young people in decision-making for the green transition. It underlines the need to integrate sustainable development education from an early age and equip them at work with green skills through practical training. It suggests that EU members should invest significant resources to support entrepreneurs, particularly young ones who intend to invest in green businesses, and to give young people career guidance at school, and to support them in work [

19]. In a few years, when humanity is expected to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), it will be the current youth who are entering adolescence who will bear the fruits of current environmental and climate decisions and suffer or enjoy their consequences the most [

20].

Therefore, it is important to understand that the role of youth in tackling social problems and environmental threats is crucial. Young people should be taught and encouraged to work for sustainable development by taking up employment in sustainable enterprises, as well as establishing such entities themselves, or attempting to initiate impact startups—innovative businesses that have a positive impact on the environment and society.

Despite the growing global awareness of sustainable development and the increasing emphasis on green transition policies, the extent to which young people are prepared and motivated to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship remains unclear. There is a lack of integrated understanding of how environmental attitudes or entrepreneurial intentions intersect in youth populations, especially across different socio-economic and educational contexts.

A key research question that informs our study is how students conceptualize and internalize sustainable entrepreneurship, and whether their stated intentions align with their actual willingness and perceived ability to respond to social and environmental challenges through entrepreneurial action. Furthermore, it remains unclear to what extent national contexts, educational frameworks, and personal values shape these orientations and potential behaviors.

The study aims to contribute to a broader understanding of the conditions under which young people can become effective agents of sustainable economic transformation by exploring students’ attitudes, perceived barriers, and their willingness to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship in countries such as Poland and Greece. Filling this knowledge gap is crucial for the design of educational, policy, and institutional interventions that support entrepreneurship and impact young people across Europe and beyond.

We selected young people from these two countries, located in different parts of Europe, to investigate whether their attitudes and perceptions of environmental and social issues and challenges differ. Both countries are members of the European Union, and both Greece and Poland face different but pressing social and environmental challenges shaped by their geographic, economic, and political realities. We wish to explore how, despite these contextual differences, youth in each country perceive and respond to the idea of sustainable entrepreneurship. Comparing these two contexts also allows us to determine whether young people from different European regions are converging in their support for sustainable development. Such a comparison enriches the broader discourse on how to empower youth in different European settings to drive the transition towards sustainable entrepreneurship.

The article is structured as follows. The first theoretical section includes a systematic review of the literature on the subject, a review of the definitions related to the issues of sustainability in business, a review of research on the readiness of young people for sustainable enterprises, a description of the characteristics and motivations of sustainable entrepreneurs, and their attitudes towards solving social and environmental problems. Then, we presented the applied research approach, characterized the respondent group, and formulated the hypotheses. The next section presents the research results, followed by a discussion and conclusions.

Student youth expressed their attitudes towards sustainable entrepreneurship. Their assessment included opinions on the need to establish such enterprises, the willingness of students to take up employment in such enterprises, and the intentions of the respondents to establish them in the future.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability in Business—Definitions

The Sustainable Development Goals were established as part of the United Nations 2030 Agenda to guide sustainability efforts and policies and leverage financial resources to address poverty, environmental protection, social inclusion, and economic growth [

21]. Sustainable development was, thus, defined as development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [

22].

A sustainable enterprise is an entity that introduces the SDG goals. According to McKinsey, it is about integrating sustainability into every aspect of a company’s value chain—from supply chains and operations to product design, marketing, and end-of-life management. It aims to increase profits while reducing environmental impact by discovering growth opportunities, managing risk, and improving returns on capital. The International Labour Conference (ILC) emphasizes the importance of an enabling environment that supports youth-led businesses through appropriate values, legal frameworks, administrative systems, and supportive institutions. This includes promoting investment, entrepreneurship, and respect for workers’ rights, while aligning enterprise development with decent work, human dignity, and environmental sustainability [

18]. In the literature on the subject, researchers focus on many aspects related to sustainable enterprises—one can find research on the concept of sustainable enterprise development, as well as on the sustainable entrepreneurs themselves [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Muñoz and Cohen [

27] define sustainable entrepreneurs as simultaneously creating positive social and environmental outcomes and economic value creation. Some researchers juxtapose sustainable entrepreneurship with other concepts such as “ecopreneurship” [

28,

29], “green entrepreneurship” [

30], or “environmental entrepreneurship” [

31,

32,

33,

34].

Sustainable entrepreneurship refers to entrepreneurial activities that generate economic, social, and environmental value simultaneously, aligning with the triple-bottom-line approach that emphasizes a balanced integration of profit, people, and planet [

35,

36]. Although sustainable and social entrepreneurship are closely related, they are conceptually distinct. Both aim to generate positive social or environmental outcomes, but they differ in how they mobilize and leverage resources. Sustainable entrepreneurs typically pursue scalable, long-term ventures that rely on planning, formal partnerships, and external investments to achieve systemic impact [

37,

38]. In contrast, social entrepreneurs leverage limited available resources, including personal networks, community support, and existing assets. These differences reflect two complementary paths to sustainability: one based on strategic growth and capital optimization and the other based on adaptability, ingenuity, and mission-driven innovation in resource-constrained environments [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Di Vaio et al., on the other hand, emphasize the innovative aspects, stating that sustainable entrepreneurship is the pursuit of sustainable innovation, stressing that business models are responsible for achieving the SDGs by integrating sustainability assessment into the life cycle phases of innovative entrepreneurial ventures [

44]. The innovative ventures that play an important role in the sustainability transition are called impact startups. They are perceived as actors for the introduction and diffusion of sustainability innovation. Horne and Fichter define impact startups as innovative new ventures that diffuse solutions at scale that have a sustainability net benefit [

45]. The authors also describe and explain how impact startups contribute to the sustainability transition through growth. Since 2019, Kozminski University (Warsaw, Poland) has published annual reports on startups with a positive impact. They, in turn, define this type of business as an innovative form of entrepreneurship that addresses important societal challenges, such as quality education, gender equality, and clean and affordable energy [

46]. As startups are often based on technological solutions, the concept of an impact tech startup has also emerged. According Gidron et al., an impact tech startup combines characteristics of a regular startup, namely a strong focus on technology and innovation, operation within conditions of extreme uncertainty, attempts to explore new business opportunities, etc., with those of a social enterprise, namely a dual mission to achieve both social/environmental and commercial objectives [

47]. Carle points out the complexity of the problem when it comes to the impact of start-ups on the environment and society and proposes deeper research on the assessment of the impact of start-ups on sustainable development [

48]. In addition to research in this area, aspects of the younger generation’s orientation toward sustainable enterprises should also be more widely explored, whether young people are aware of existing environmental risks and social challenges, whether they are positive about solving these problems by working at sustainable enterprises, and finally, whether they intend to start such businesses themselves.

2.2. Youth Perspectives on the Importance of Sustainable Enterprises

A growing body of the literature highlights the importance of understanding young people’s perceptions of sustainable business and their role in addressing global challenges. Studies suggest that Generation Z increasingly values social and environmental responsibility in business and prefers companies and careers that align with sustainability principles [

49,

50]. Young people are not only aware of the climate crisis and other environmental threats, but they are increasingly motivated to take action. For example, youth participation in global forums such as the UN Climate Change Conferences demonstrates their growing commitment to shaping a sustainable future [

20]. In turn, The Statista Consumer Insights Sustainability Survey reveals that the majority of Generation Z prefer peaceful, constructive approaches to environmental action, such as participating in initiatives and peaceful protests, rather than radical or illegal measures. Nearly half identify themselves as sustainable consumers, and about a third are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products, indicating that sustainability is a growing and important expectation for brands and companies [

51]. Research among Slovenian students reveals a basic awareness of sustainability but highlights significant educational gaps, particularly in understanding effective practices [

52]. The results show that academic level and field of study significantly impact sustainability knowledge, emphasizing the need for curriculum adjustments. In turn, a study conducted among Polish students by Zwolińska et al. assesses the awareness of sustainable development among young people. The research shows a growing awareness among students of the role of sustainable development in education, careers, and society [

53]. The results emphasize the need for improved educational content that integrates economic, social, and environmental issues to better prepare the student youth for a sustainable and innovative economy [

53]. Sustainable enterprises are often seen by youth as vehicles for social and environmental transformation. According to Kim and Song [

54], many young people perceive sustainability not just as a value but as a strategic imperative in entrepreneurship. Several studies focus on the role of universities in supporting youth engagement in sustainability [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. For example, Papp-Váry et al. [

55] and Rajasekaran [

57] emphasize that structured programs can influence sustainable entrepreneurial mindsets. However, these educational efforts often fall short of fully addressing the environmental and social dimensions [

59].

While education continues to play an important role in shaping these perspectives, it is only one of several factors. Peer networks, media, and access to social innovation ecosystems also contribute to shaping young people’s views on the role and need for sustainable enterprises. Ayob et al. point out that, while conventional entrepreneurship remains relevant, sustainability concerns are gaining ground, especially among young people involved in grassroots initiatives and startup communities [

60]. So far, there is a lack of studies that have investigated youth perspectives on the importance of sustainable enterprises and whether young people perceive the need to create sustainable enterprises. Therefore, we are investigating this in our research. While many studies explore the influence of education on entrepreneurial intention, few directly investigate whether young people themselves recognize the value of sustainability in business or intend to pursue it in practice. This is the gap our research aims to address, exploring whether young people consciously view sustainable enterprises as essential tools for addressing societal and environmental problems, and how their values, motivations, and aspirations align with this objective.

2.3. Readiness of the Young Generation for Sustainable Enterprises

There is a lack of comparative studies or even separate studies conducted in Greece or Poland among the younger generation that address the issues raised in our article. However, we have identified some studies related to the selected research issue. They highlight the growing awareness and interest among youth in sustainable entrepreneurship in different countries. In Poland, a survey conducted by Grodek-Szostak et al. examined the understanding of “green entrepreneurship” among students and professionals [

61]. The results showed that, while there is a general awareness of the concept, interpretations vary, with some associating it primarily with environmental aspects and others taking into account the social and governance dimensions [

61].

A study by Papavasileiou et al. examined the impact of sustainability-focused extracurricular activities on Greek university students [

62]. The study found that participation in such activities significantly increased students’ awareness of the Sustainable Development Goals and fostered a stronger commitment to sustainable practices [

62].

When it comes to the youth’s readiness for sustainable enterprises, research conducted by Zhang et al. among Chinese university students showed that environmental values, green self-efficacy, environmental concern, green citizenship behavior, and climate change knowledge have a significantly strong positive effect on students’ sustainable entrepreneurship intentions [

63]. Moreover, the results of the study by El Gohary et al. show that students’ attitudes towards sustainable entrepreneurship mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial education and sustainable entrepreneurship intention [

64]. In addition, the study found a relationship between social media and survey participants’ attitudes toward sustainable entrepreneurship and their intention to act in sustainable entrepreneurship [

64]. According to Ordonez-Ponce et al., students’ readiness for sustainable enterprises is aligned with the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals, which emphasize collaboration among businesses, governments, and communities to address social and environmental challenges [

65]. These partnerships offer students a practical pathway to engage with sustainability goals, demonstrating how enterprises can contribute to solving local issues while addressing global challenges. This creates an opportunity for students to see sustainable entrepreneurship as vital not only to personal success but also as a vehicle for social and environmental impact [

65]. According to research in Hungary conducted by Papp-Vary et al., Generation Z’s fear of starting a business requires targeted communication that uses keywords, highlights high-earning potential, and showcases successful, sustainable startups [

55]. Practical education, diverse information channels, and expanded policy support for university and non-university entrepreneurs are essential to strengthen this entrepreneurial ecosystem [

55]. Furthermore, Hoogendoorn et al. notice that sustainable entrepreneurs face greater institutional barriers when starting a business due to the lack of financial, administrative, and informational support compared to their conventional counterparts [

66]. In addition, sustainable entrepreneurs show a higher propensity to fear personal failure due to their diverse and complicated stakeholder relationships [

66].

When it comes to the youth’s readiness to establish an impact startup, there are also some studies that can be linked with our research. Over the past two decades, increasing attention has been paid to environmental issues affecting entrepreneurial ventures (i.e., start-ups and incubators) and their innovative solutions aimed at attaining cleaner production processes for sustainable development [

67,

68,

69,

70]. Papp-Vary et al.’s research revealed that 9% of the Hungarian university students plan to set up an impact startup [

55]. The need to promote sustainability in start-ups in order to foster a truly sustainable entrepreneurial culture was pointed out as early as 2002 by Schick et al. The authors also identified several significant barriers that make it difficult for start-ups to adopt green practices, including a lack of information for entrepreneurs, insufficient environmental knowledge among advisors, unrecognized market opportunities for green ventures, and insufficient public funding support [

71].

The willingness of young people to start their own sustainable enterprises or impact start-ups, or even their propensity to become involved in other sustainable enterprises’ initiatives, is also not well researched, especially in the countries where we have chosen to conduct our research. In our research, we define readiness for sustainable enterprises as both the readiness to establish sustainable enterprises or impact start-ups and the readiness to be employed in such entities.

2.4. Characteristics and Motivations of Sustainable Entrepreneurs

Young people’s perspectives on sustainability in business include the characteristics of individuals who seek to pursue social and environmental missions in their businesses, their own characteristics in this context, and the feasibility of creating an innovative start-up. Gumulya identifies six key characteristics of sustainable entrepreneurs: altruism, innovativeness, ability to balance values, economic motives and perceived capabilities, honesty, self-compassion, and holistic [

72]. Schlange, on the other hand, argues that a key characteristic of sustainable entrepreneurs is a strong focus on environmental issues in their business vision. She also highlighted the limited research on the factors that drive investors to create sustainable enterprises [

73].

As early as 1998, Anderson and Isaac emphasized that “ecopreneurs” are increasingly seen as critical change agents or champions, driving the collective learning process in which society needs to engage [

74,

75]. Schaltegger, in turn, claims that eco-, environmental, or green entrepreneurs are characterized by a strong environmental orientation and prioritize minimizing environmental impact, while Cohen and Winn and Dean and McMullen add that they specifically address environmental market failures [

3,

76,

77], as well as engage in innovation processes that are socially inclusive towards local communities, addressing the community’s specific needs and resources. Furthermore, the gender, age, educational background, and professional background of entrepreneurs have significant effects on green entrepreneurship orientation. However, what can be in contradiction to the above-cited studies is that the educational background of entrepreneurs has a negative influence on social orientation and environmental orientation, according to the research results of Chen et al. [

78].

Sustainable entrepreneurs are driven by a mix of opportunity recognition, desire for autonomy, and necessity. Their motivations include identifying market gaps, making a living, and upholding green values. Additionally, they seek to enhance social and economic well-being, preserve community and cultural integrity, and combat environmental degradation. Externally, their actions are shaped by regulations and policies, market and customer demands, resource availability, and social and community factors, all of which influence their sustainable practices and innovations [

36]. Entrepreneurs are motivated not only by economic or self-centered aspects, but also by factors like helping others or reducing environmental damage [

27]. However research by Mroczek et al. among students in Poland shows that financial aspects, i.e., the possibility of earning a significant income from one’s own business, as well as independence and the possibility of being a manager, proved to be much more motivating for entrepreneurship than the possibility of changing the world for the better, helping local communities or protecting the environment [

79]. The study also revealed that young people have an intuitive sense of what sustainable enterprise is, but formal knowledge in this area is low [

79].

To describe the different motives or orientations of the green entrepreneur, an exploratory typology of green entrepreneurs was proposed by developing Thompson’s four dimensions of entrepreneurship: “ethical maverick”, “ad hoc environpreneur”, “visionary champion”, and “innovative opportunist” [

30]. The typology of green entrepreneurs assumes that all green business founders, regardless of type, seek to maximize or optimize financial returns. It also recognizes that green and ethical entrepreneurs often have mixed motivations, combining environmental, ethical, and social goals that may be difficult to separate because they are consistent with the broader concept of sustainability. All types of green entrepreneurs, whether motivated by ethical considerations, market opportunities, or other factors, play a role in promoting sustainable development. Therefore, in our study, we analyze young people’s perspectives on solving social and environmental problems, drawing their attention to both types of challenges.

2.5. Social and Environmental Challenges in Poland and Greece—Future Trends

The challenges Greece faces include rapid urbanization, industrial and agricultural intensification, inefficient energy production, and mass tourism, which are degrading air, water, soil, and coastal zones. In addition, climate change is reducing rainfall, especially in summer, posing additional threats to biodiversity, water resources, and ecosystem stability [

80]. Greece has room for improvement in environmental sustainability. Despite a 2022 national climate law and a commitment to phase out coal by 2028, the country is struggling with rising greenhouse gas emissions. Natural disasters have worsened environmental conditions. The National Action Plan for Energy and Climate aims for climate neutrality by 2050, but implementation depends on regional administrations. Despite a circular economy strategy, the country has the largest material footprint in the OECD and low recycling rates. Infrastructure and digital networks are improving, but rail transport remains weak. The country has committed to decarbonizing its energy system by 2050, with the goal of phasing out lignite by 2028. Unemployment has declined but remains high, especially among young people. Greece is making progress but still faces significant challenges in terms of sustainability and labor market adjustment [

81].

Poland, on the other hand, faces serious environmental challenges, including the lack of a national strategy to combat climate change, an unfavorable energy mix, low investment in green energy, and problems resulting from inefficient resource management [

82]. Poland ranks last in environmental sustainability in Sustainable Governance Indicators, with weak climate policies, reliance on coal, and resistance to EU regulations. The country needs to address problems of air quality, waste, and water pollution. In reducing poverty, energy prices were frozen and housing loans offered, but inflation and high living costs hindered progress. The circular economy remains in the early stages. The Polish labor market shifted to being employee-centered, keeping low unemployment rates [

83].

According to the research carried out in Poland by The Polish Agency for Enterprise Development among young companies (including startups) on the main trends that will dominate in the next 5 years, it will mainly be the implementation of AI and transparency and authenticity, both declared by almost one in three entrepreneurs. A significant group of entrepreneurs identifies the trends related to environmental protection:

- -

Energy-oriented economy (19%)—sustainable management of resources and development of energy of the future;

- -

Life after plastic (12%)—the search for alternatives to single-use plastics;

- -

Refill culture (12%)—promoting multiple uses of packaging and resources;

- -

Inclusion and diversity (14%)—supporting diversity and integration of different social groups;

- -

Digital health (14%)—developing digital technologies in healthcare, including VR, AR, AI, and IoT.

There is little difference in trend forecasting between startups and other young companies, but startups show more interest in technology-related trends and less in the green aspects of business. But overall, it can be summarized that entrepreneurs are particularly aware of the growing environmental and social challenges that will shape the future of business [

84]. The indicated trends show that new companies want to get involved in solving social and environmental problems. Our research has yet to verify whether young people have similar visions for planning to meet the challenges and actively solve social and environmental problems.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Methodological Assumptions of Analysis

The transition to sustainable enterprises requires active participation from younger generations. Understanding their awareness, readiness, and opinions on sustainability is essential for shaping policies and strategies. This study investigates youth perspectives in Poland and Greece and has allowed for the adoption of four research hypotheses.

H1: Young people in Poland and Greece see the need to establish sustainable enterprises.

H2: Young people in Poland and Greece are ready for sustainable enterprises.

H3: Young people in Poland and Greece have similar visions of sustainable enterprises.

H4: Young people in Poland and Greece deal with social and environmental problems in a similar way.

The following methods were used to verify them.

Exploratory data analysis (EDA): EDA was conducted to summarize and visualize the key patterns and trends in the data, enabling an intuitive understanding of youth perspectives. Descriptive statistics provided insights into central tendencies and variations across responses. Visualizations, such as bar charts and scatter plots, were employed to highlight the differences and similarities between the respondents from Poland and Greece [

85,

86].

Chi-square test: Chi-square tests for independence were utilized to evaluate the associations between the categorical variables, such as country of origin and responses to survey questions. This method assesses whether the observed differences between groups are statistically significant, providing a robust framework for hypothesis testing. For example, the association between the country and the perception of sustainable enterprises was analyzed to determine if youth perspectives varied significantly. Chi-square tests are widely regarded for their ability to handle qualitative data and are particularly suitable for survey datasets with categorical responses [

87]. The inclusion of chi-square analysis ensured that any detected patterns were not due to random chance, thus bolstering the study’s reliability. To verify the hypotheses, (α = 0.05,

p < α) was adopted, as were the following terms for statistical significance:

p < 0.05-existing (*),

p < 0.01-high (**), and

p < 0.001-very high (***).

Machine learning: To go beyond simple group comparisons and uncover deeper respondent typologies, we applied a clustering analysis to the full dataset. Responses were analyzed jointly rather than separately by country to explore cross-national patterns and overlapping profiles. This approach allowed us to examine whether young people from different national contexts fall into shared attitudinal or motivational clusters, thus offering a richer insight than country-level statistics alone. Input variables for clustering were selected from the survey questions that were related to the particular theme that the analysis was attempting to address.

More specifically, the k-means algorithm was implemented to uncover latent patterns and segment respondents based on their opinions. This unsupervised learning technique is ideal for grouping individuals with similar characteristics or responses, offering insights into the diversity of youth perspectives. The application of k-means clustering is widely recognized for its efficiency and interpretability in analyzing survey datasets [

88]. In the context of the current paper, the k-means algorithm was used in the Python ver. 3.9.16 programming language [

89] using the scikit-learn package. The advantages of using clustering to answer the research questions include:

Grouping responses based on overall patterns, rather than focusing solely on demographic data, reveals unexpected insights and trends;

Clustering enables the identification of overlapping opinions across both countries (Greece and Poland) and highlights areas of consensus or divergence;

By reducing the complexity and dimensionality of the original questionnaire data, clustering facilitates a clearer interpretation and actionable conclusions.

Finally, a principal component analysis (PCA) was used prior to visualization to reduce the high-dimensional survey data into two principal components that preserved the most variance. PCA was not used to perform clustering and was not incorporated into the clustering method. Rather, it was used to facilitate visual interpretation of the resulting clusters.

3.2. Data Collection

The dataset used in this article includes survey responses from 336 participants (Poland: 246; Greece: 90). The survey included questions on awareness, attitudes, and beliefs regarding sustainability and was conducted among the students of 7 universities (4 from Poland and 3 from Greece). A multi-stage sampling of the study with elements of random and purposive sampling was used. In the first instance, it was decided to select universities from both countries that would meet the conditions: not being too far from each other (which was due to the reduced cost of conducting the national survey) and the availability of business and economics courses on offer (purposive sampling). Then, groups of students were drawn for the study (random sampling). Finally, those who agreed to participate in the study were drawn (random sampling).

As students are gaining up-to-date knowledge about sustainable entrepreneurship, and the impact of curricula on shaping entrepreneurial intentions is confirmed by many researchers, students were selected as an important group among the potentially promising founders of sustainable enterprises. Moreover, since a significant proportion of students work, such a selection does not narrow the perspective of the research conducted.

Data was collected using a survey questionnaire available online and distributed by the study authors between May 2023 and June 2024.

The research questionnaire consisted of 19 main questions and 9 metric questions. It was designed to assess young people’s knowledge, attitudes, and readiness to engage in socially responsible investments and entrepreneurship with a social mission. The questions were closed-ended with single or multiple-choice answers and anchored scale ranging from 1 to 5, with the option of selecting “I have no opinion.”

The thematic scope included:

- -

Knowledge of concepts related to sustainable entrepreneurship, as impact investing, social venture capital;

- -

Attitudes toward investing with consideration of social and environmental aspects;

- -

Identification of local problems and those responsible for solving them:

- -

Assessment of the characteristics of individuals carrying out social missions in business;

- -

Declarations regarding future professional plans (e.g., establishing a sustainable enterprise or impact startup, or working for such entities);

- -

Experiences and beliefs related to charitable activities and financing sustainable enterprise.

The metrics part included data on gender, field and level of studies, place of residence, professional situation, and financial status assessment.

The questionnaire was anonymous and was completed online.

The participants of the research were the students of the selected universities. The main information about the sociodemographic data is shown in detail in the table (

Table 1).

The majority of participants in both study groups were women (86% in Poland and 53% in Greece). Most of the respondents were full-time students. For Polish students, these were mainly first-year students (54%), while for Greek students, they were fourth-year students (34%) and first-year students (31%). The respondents from Poland mainly studied Social Sciences (40%) and Psychology (20%), while the respondents from Greece studied mainly Business Administration (29%) and Environmental Engineering (16%). In terms of socio-demographic characteristics, the majority of respondents lived in a city with 51–100 thousand inhabitants (44% from Poland; 57% from Greece). Significantly, the respondents from Poland were mostly employed on a casual basis (44%), while the respondents from Greece were mostly unemployed (47%). This characteristic differentiates the respondents in both countries quite strongly, as the second-most-represented sub-groups by labour market status were, in the case of Poland, the unemployed (42%), while in the case of Greece, those employed in private enterprises (33%). Due to the changes in the education system during the COVID-19 pandemic, many universities offer education in a hybrid system, combining online and on-site systems. In addition, students with a sufficiently high average can study in an individual study organization, which allows them to combine work and study. As a result, many students gain work experience while studying. In both groups, the majority of respondents considered their material status to be good (41% of respondents from Poland and 42% from Greece). Slightly smaller proportions of respondents described their material status as average (40% and 41% respectively).

4. Results

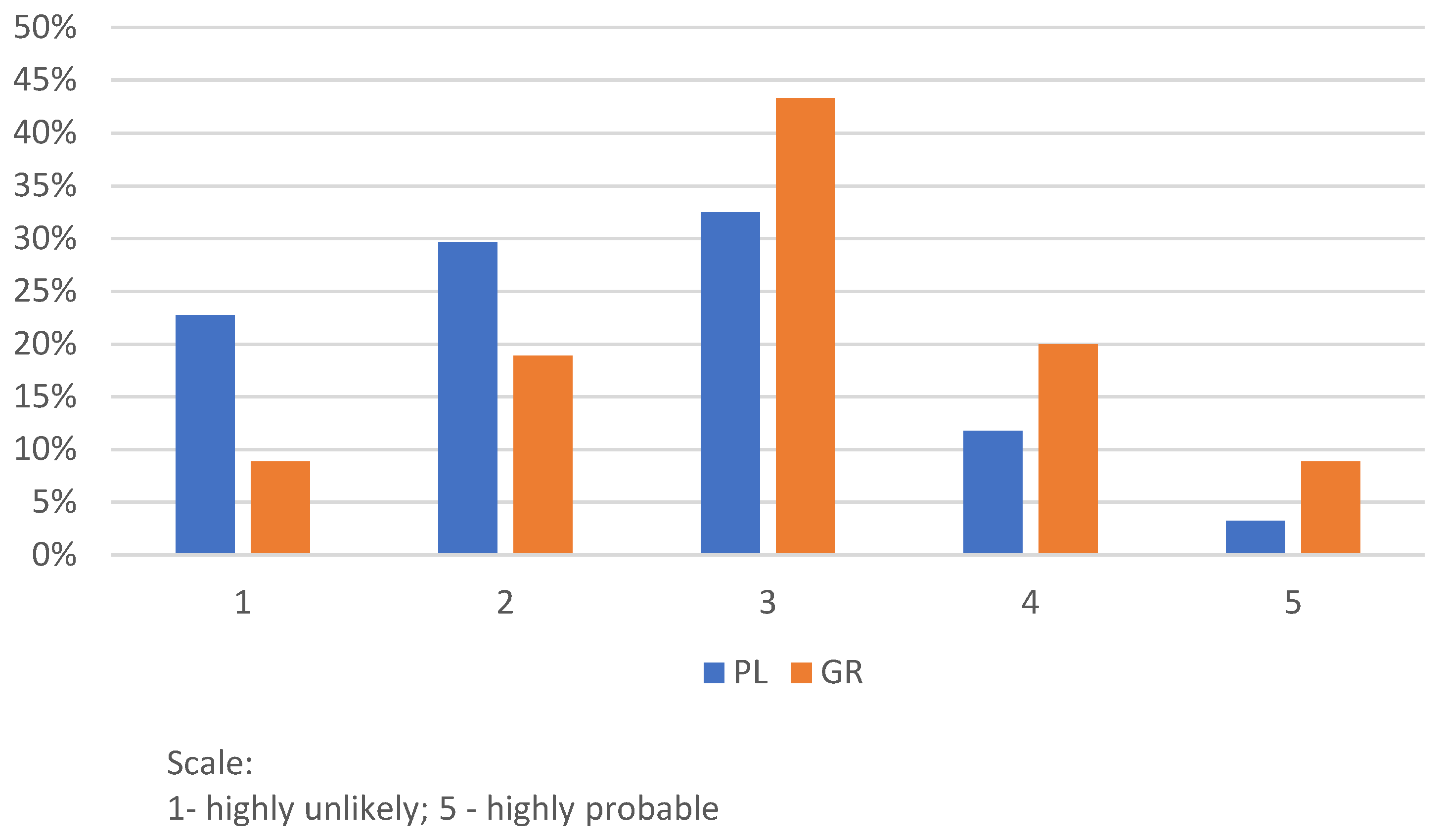

An exploratory analysis indicated that the respondents from both Poland (PL) and Greece (GR) generally recognized the importance of sustainable enterprises (

Figure 1). A chi-square test was conducted to evaluate the importance of sustainable enterprises. The results (χ

2 = 9.10,

p = 0.105) indicated no statistically significant difference in the responses between Polish and Greek participants, suggesting a shared recognition of the importance of sustainable enterprises across both countries.

Differences emerged when it came to the need for actors to fulfil social missions (

Figure 2). A chi-square test (χ

2 = 26.27,

p < 0.001) revealed a statistically significant difference between Polish and Greek responses. Polish respondents were more likely to disagree with the statement that organizations with social missions are unnecessary, while Greek respondents expressed more divergent opinions.

It allows us to verify the first hypothesis (H1: Young people in Poland and Greece see the need to establish sustainable enterprises). The findings indicate that there is a difference in the perception of the need to set up such entities. While the respondents agreed that such enterprises are very important for the economy and society, some also declared that entities implementing social missions are not needed by the economy at all. The differences indicated may be due to familiarity with the operation of such enterprises, which may be related to the study of social economics. This line of thinking would be confirmed by the sample selection, in which a significant majority of Polish respondents studied this particular field of study.

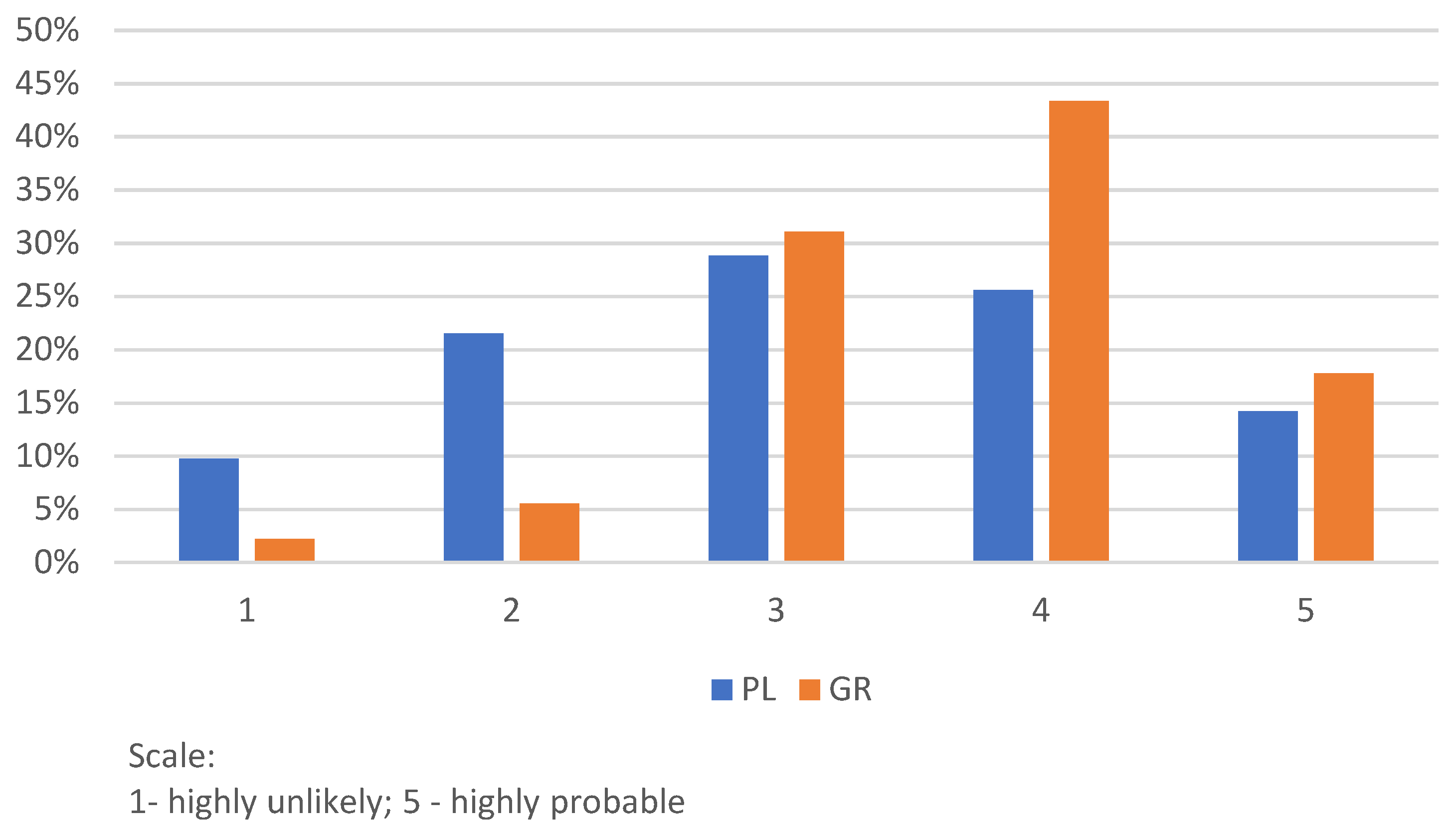

To verify the second hypothesis (H2: Young people in Poland and Greece are ready for sustainable enterprises), three survey questions were analyzed. These concerned respondents’ plans for the future and covered three possible scenarios:

Starting their own company that will solve social or environmental problems;

Starting their own innovative business that will solve social or environmental problems—the so-called impact startup;

Being employed in a company that solves social problems.

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 below illustrate the distribution of responses for these questions across Polish and Greek participants. The analysis indicated that Greek respondents showed a higher tendency to start their own company or innovative start-up, as well as that they were more likely to indicate interest in being employed by companies addressing social problems. When it came to setting up sustainable enterprises or impact start-ups, Polish respondents were more reluctant to do so, whereas when it came to employment in sustainable enterprises, they were more hesitant about their career plans in this regard (tendency to average—the distribution of responses was more even).

To gain deeper insights into the diversity of youth perspectives and readiness for sustainable enterprises (thus attempting to gain further insights on H2: “Young people in Poland and Greece are ready for sustainable enterprises”), the k-means algorithm was applied, selecting question 15.1 (“Will start their own company that will solve social or environmental problems”), question 15.2 (“Will start their own innovative business that will solve social or environmental problems—the so-called impact startup”), and question 15.3 (“Will be employed in a company that solves social problems”), which best captured the overall theme of the degree of readiness of young people for sustainable businesses. For the algorithm, 70% of the data (responses from those questions) were used for training, while the remaining was used for validation.

The cluster analysis revealed two clearly distinguishable respondent profiles:

While the country of origin was not part of the clustering process and the algorithm was applied to all the responses to the relevant questions, an additional layer was added to investigate how dominant the representation of each country was to each cluster.

Table 2 below shows that Polish respondents were more evenly split between the two clusters, while Greek respondents showed a significantly stronger tendency to fall into the highly motivated group. Specifically, 71% of Greek respondents belonged to Cluster 0, in contrast to 49% of Polish respondents. This supports the view that Greek youth may demonstrate higher enthusiasm for social entrepreneurship and employment in sustainability-oriented companies.

To verify the third research hypothesis (H3: Young people in Poland and Greece have similar visions of sustainable enterprises), nine questions were analyzed, which covered three main areas:

Characteristics of a person (not the respondent) intending to pursue social and/or environmental missions as part of their own business (in the table: Person) [Question: What should be the characteristics of a person who intends to undertake social and/or environmental missions as part of their own business?];

Characteristics of the respondent from the same angle (in the table: Respondent); [Question: Do you have the following characteristics/education/preparation to run an enterprise implementing social/environmental missions?];

Possibility to set up their own innovative impact start-up. [Q: I will start my own innovative business that will solve social or environmental problems—the so-called impact startup].

While these variables might not capture the multi-dimensional nature of a sustainable enterprise, or the whole set of traits that a person managing such an enterprise should have, nonetheless, these questions/variables are meant to capture how the respondents view the ideal person, especially in terms of experience, creativity, and education. It might not be a holistic approach, but it provides a cultural framing of who is seen by higher education students in Greece and Poland as capable of achieving sustainability goals through entrepreneurship.

Table 3 presents the results of the analysis of the differences between the respondents, with regard to the issues under consideration.

Chi-square tests for independence were performed to determine if there were statistically significant differences between Polish and Greek responses for each question. Significant differences were found in five of the nine comparisons (

Table 3). Polish and Greek respondents differed significantly in how they assessed external characteristics, particularly regarding whether a person was dynamic, creative, and resourceful (with a

p-value = 0.0006), educated (with a

p-value ≈ 0.0000003), or uneducated but inexperienced (with a

p-value = 0.0104). The results indicate that Greek respondents assessed more favorably the potential businesspersons who might not adhere to the typical, well-educated profile, while Polish respondents emphasized formal education.

In contrast, when the respondents assessed themselves, the differences were generally not statistically significant, with the exception of being uneducated but experienced (with a p-value = 0.0001).

A significant variation was also found in the willingness to start an impact startup (with a p-value = 0.0451), where Greek respondents were more likely to express interest. These results suggest that, while both groups assess themselves with the same characteristics, they hold different values when assessing other businesspersons.

In addition to the chi-square tests, the k-means algorithm was performed to uncover hidden patterns in the perspectives of young people in Greece and Poland regarding sustainability, social responsibility, and entrepreneurship. This exploratory step was conducted to act complementarily to the chi-square analysis by revealing potential insights on distinct types of responses when multiple variables are used as input.

This analysis grouped the respondents based on their responses to the survey questions used across several of the research questions discussed earlier, and more specifically, it used the responses from the following questions:

13.2: “A dynamic, creative, and resourceful person to be able to run a business well”;

13.3: “An educated person with preparation to run this type of business”;

13.4: “An uneducated person but with experience in business”;

13.5: “An uneducated person with no experience in business”;

14.2: “A dynamic, creative, and resourceful person to be able to run a business well”;

14.3: “An educated person with preparation to run this type of business”;

14.4: “An uneducated person but with experience in business”;

14.5: “An uneducated person with no experience in business”;

15.2: “Will start their own innovative business that will solve social or environmental problems—the so-called impact startup.”;

17.1: “Belief that entities focusing on social missions are crucial for society”;

17.2: “Belief that individuals must take personal responsibility for solving environmental issues”.

Regarding the choice of question, the responses that form the input space for the application of the clustering algorithm, questions 13 and 14, assess the characteristics of a person to start a sustainable enterprise. While these sets of questions appear similar in wording, they nonetheless entail a significant distinction, namely, how the respondents assess the traits of a businessperson in a sustainable enterprise against how they assess themselves. The inclusion of both can allow for the clustering analysis to reveal potential gaps between the assessment of others against self-perception. Question 15 represents the intent to form such a business, while finally, question 17 indicates where the respondents place more value in achieving sustainability, whether on businesses or individuals. Together, these questions form an overall view of what a sustainable enterprise and its inherent value are and aim to reveal further insights into question H3. The k-means clustering algorithm was trained on 70% of the data from the above questions using Euclidean distance and k = 3 clusters, selected for interpretability. In addition, a principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to reduce the dimensionality of the input space for visualization only. The clustering analysis revealed three distinct groups of respondents, and

Table 4 below summarizes the mean value for each question for each cluster.

While the clustering did not explicitly use country labels, an overlay of the clusters (

Table 5) indicates that the Polish respondents were predominantly represented in Cluster 1, while the Greek respondents were more evenly distributed among the clusters.

The two axes of

Figure 6 represent the first and second principal components that were produced with the PCA analysis, accounting for 26.95% and 18.97% of the variance, respectively.

The horizontal axis (PC1) primarily captures the orientation toward formal approaches, such as valuing education, creativity, and belief in social investment, while the vertical axis (PC2) represents a positive assessment of non-traditional paths, such as accepting uneducated but experienced individuals and self-identifying with non-traditional profiles.

The three clusters are represented with different colors:

Cluster 1, in green: it is mostly placed near the center, showing moderate self-assessment and strong beliefs in dimensions such as social investment. These respondents (mostly Polish) value formal qualifications and social responsibility but respond with lower intention to initiate a business;

Cluster 2, in yellow, is mostly placed in the upper-left space, representing respondents with high belief in both formal and informal traits, high confidence in their own capabilities, and a strong intention to start an enterprise. This group includes both Polish and Greek respondents;

Cluster 0, in purple, is mostly placed on the right, indicating low scores on nearly all variables. These respondents show limited belief in formal qualifications, informal experience, social finance, or their own readiness.

To verify the fourth research hypothesis (

H4: Young people in Poland and Greece deal with social and environmental problems in a similar way), three questions, capturing various dimensions of social and environmental engagement, including awareness, perceived importance, and individual versus collective responsibility, were analysed. By analyzing these perspectives, it was possible to assess how young people in Poland and Greece prioritize and respond to social and environmental problems (

Table 6).

The chi-square test results indicate varying levels of statistical significance across the three examined variables. The association between country and taking action to address social or environmental problems was statistically significant (p = 0.0285). The association between country and the belief in the importance of socially responsible investing was not statistically significant (p = 0.0568), though it was close to the threshold (p < 0.05), suggesting a potential issue that could be explored in future studies. However, it was when it came to questions relating to social venture capital funds that a statistically significant difference was observed, indicating that Polish and Greek respondents differed in their perception of the effectiveness of social capital. Polish participants expressed greater optimism about the transformative role of the investors in solving global challenges, while Greek respondents were more skeptical.

5. Discussion

The results of this study offer a comparative perspective on how youth in different European countries—specifically Greece and Poland—perceive and engage with sustainable entrepreneurship, highlighting both shared values and striking differences in attitudes, willingness, and socio-cultural impacts.

Young populations in both countries share the common vision of promoting sustainable development and creating an enabling business environment towards this goal. Sustainable entrepreneurship, which fosters environmental and social action, is recognized as important by young people in both countries.

At the same time, the results demonstrate some distinct approaches between Greek and Polish youth regarding socio-environmental concerns and sustainable entrepreneurship. The differences between Greek and Polish youth are particularly noteworthy regarding social missions and their perception of the necessity or not of enterprises that fulfill such missions.

Although both Polish and Greek respondents agree on the significance of sustainable entrepreneurship, there is no common approach or vision of what constitutes a sustainable enterprise. On the other hand, Greek and Polish youth may not share such a common vision, but they strongly believe in the importance of education and training for running a sustainable enterprise.

Regarding their readiness to initiate their own sustainable enterprise, Polish youth appear reluctant to start their own company or innovative business, and Greek youth seem more interested in being employed by sustainable companies.

The differences spotted may be attributed to differences in the economic, social, and cultural environments in the two countries, as well as to the familiarity with sustainable entrepreneurship in general. While both countries are members of the European Union and may share common values, their populations are influenced by each country’s special characteristics and circumstances. Future research could explore the enabling factors, characteristics, and approaches that shape and impact the opinions and willingness of young populations to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship.

Similar research in other countries aligns with our findings, as it seems that young generations are keen on sustainable entrepreneurship and share similarly conscious values on environmental and social issues [

90]. A survey regarding youth entrepreneurship in Italy, Belgium, Cyprus, Ireland, Austria, and Greece has identified the lack of information and guidance on behalf of the state and the lack of an appropriate regulatory framework and incentives as critical barriers towards engaging in sustainable business [

91]. According to this study, more mentorship programs are needed to support sustainable entrepreneurship.

There is also a common perception among young people that environmental and social problems need to be addressed at all levels, especially with the cooperation of governments, citizens, the private sector, and civil society [

92]. Cooperation between all stakeholders [

93] and funding mobilization are necessary steps for creating an adequate business environment for successful, sustainable enterprises [

94].

Recommended actions towards youth sustainable entrepreneurship could be, first of all, youth empowerment. Previous research in the respective literature has demonstrated that, in general, youth empowerment needs, inter alia, an enabling and welcoming environment, a sense of meaningful engagement and participation in sociopolitical processes [

95]. Youth empowerment requires alignment in national strategies and policies for strengthening youth entrepreneurship and sustainable entrepreneurship specifically.

As this article has highlighted, knowledge and awareness among the youth population could vary, thus demonstrating a need for future research in this direction. Sustainable entrepreneurship could be further promoted if policy makers focus on building skills and raising awareness among younger generations. This process could include training activities starting from school years and using the communication and dissemination channels that the youth prefer.

In addition, a supportive policy framework could assist in leveraging the knowledge and willingness of the young generations to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship. Action-oriented approaches are necessary for promoting youth entrepreneurship and could take the form of three-step planning, including participatory engagement, managing the factors that promote/impede entrepreneurship, and providing access to support and funding [

96].

6. Conclusions

This article explores how social and environmental problems are perceived by the younger generation in two European countries, Greece and Poland, and it examines their views and visions about creating sustainable enterprises. Young people in both countries recognize the importance of ‘green’ and sustainable enterprises, and they endorse the integration of environmental and social concerns in business.

Understanding of the concept of sustainability is highly valued by the younger generation in both countries, as is the idea that enterprises should be more sustainability-oriented. Young people understand the specific skills and experience needed to establish sustainable enterprises, though they acknowledge some gaps in their preparedness. There is a strong willingness among them to address social and environmental concerns by working for sustainable enterprises rather than by creating them.

At the same time, sustainable enterprise does not mean the same thing for the young populations in Poland and in Greece, nor is their level of readiness to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship. Differences are also spotted with regard to socio-environmental concerns, as well as to their perceptions of the usefulness and necessity of social missions.

Overall, the young generation in both countries recognizes that such enterprises are critical in creating a more sustainable environment and equitable society, but the level of knowledge and awareness between them varies.

Sustainable entrepreneurship in Greece and Poland has a lot of potential despite the challenges that both countries may face due to their socio-economic and cultural environments. Sustainable tourism, renewable energy, circular economy, and sustainable food production could be very promising areas of investment in both countries. Greece strongly promotes sustainable entrepreneurship in tourism and agriculture, and Poland invests in efforts to support e-mobility and the circular economy. Furthermore, both countries have developed national strategies on sustainable agriculture [

97], and both countries are EU members. Thus, they are committed to promoting the EU’s Green Deal. EU membership facilitates both countries’ path towards sustainable entrepreneurship, as it provides access to funding programs and sustainable business opportunities. Thus, the future of sustainable entrepreneurship in Greece and Poland appears promising, despite current socio-economic challenges.

In conclusion, despite sharing a common vision for sustainability, Greek and Polish youth take different approaches towards entrepreneurship, as cultural, economic, and social factors may shape their approaches and willingness to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship. This duality—shared vision but divergent approaches—may serve as the starting point for future research on youth perceptions across other countries. Nevertheless, promoting sustainable entrepreneurship among the youth in both countries requires a holistic approach that addresses the youth’s perceptions towards sustainable development and sustainable entrepreneurship. Building knowledge, empowerment, and economic incentives are critical aspects of this process. Future research could focus on and provide more insights on how to support the young generation towards sustainable entrepreneurship.