The Limited Role of Socio-Ecological Indicators in Temporary Use of Space—Deficits in Revitalization of Degraded Urban Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

Main Research Questions Identifying the Gap Between Declarative and Practical Temporary Use of Space

2. Conceptual–Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Defining Physical and Social Sustainability Dimensions in Temporary Use of Space

2.2. Degraded Areas and Temporary Use of Space

3. Methods and Case Study Analysis

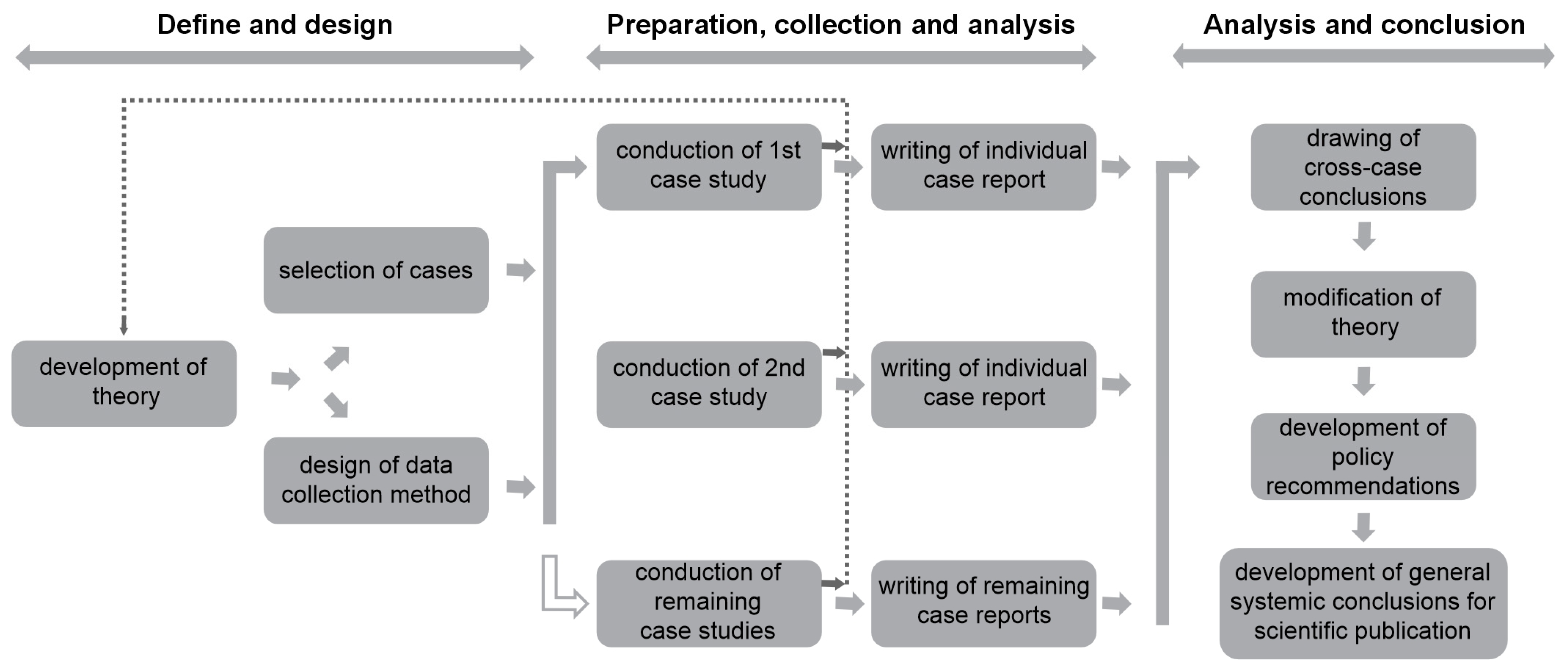

3.1. Methodology

3.2. Analysing the Limited Range of Current Sets of Indicators for Temporary Use of Space in Degraded Areas

- The evaluation of FUNCTIONAL DEGRADATION or abandonment of the space by users (for example, the degree of abandonment in relation to the presence of operational services, maintenance of infrastructure, evaluation of traffic accessibility, fluctuation of consumers; it may include some partial statistical indicators on social degradation like vandalism or presence of crime, ghettoization, etc.)

- The evaluation of PHYSICAL DEGRADATION, including environmental and historic–cultural conservation degradation in relation to protection regimes (includes indicators that evaluate the level of environmental degradation according to specific natural elements, like, for example, the activity, influence on water, soil, air, vegetation, surface or physical degradation of built environment and elements under historical–cultural protection, etc.)

- The evaluation of other influential SPATIAL FRAMING INDICATORS that define, shape and put limits to the use of space in question (such as time of abandonment, size of the area (net floor area of the area or facility), ownership distribution according to particular owners, etc.)

- The evaluation of STRATEGIC SPATIAL PLANS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT of the location in relation to investors and formal authorities (in the analysis are included, for example, documents, formal data related to strategic planning (land planning, purpose use) at the level of state, region, municipality, investors, etc.)

3.3. Analysing an Alternative Matrix of Socio-Ecological Indicators for Temporary Uses of Space in Degraded Areas

3.3.1. The Case of Tobacco Factory in Ljubljana

3.3.2. General Case Studies on Temporary Use of Space in Degraded Areas

4. Conclusions—Optimising the Model of Socio-Environmental Indicators for Temporary Uses of Space in Degraded Areas

- The scientific value of the performed research study lies in its innovative approach that connects the concept of social sustainability with temporary use of space and consequently addresses potential new approaches in spatial planning that may stem from it. These new, flexible approaches integrate the contextual analysis of social networks into spatial planning as part of necessary socio-ecological indicators that are now markedly deficient (see Table 1).

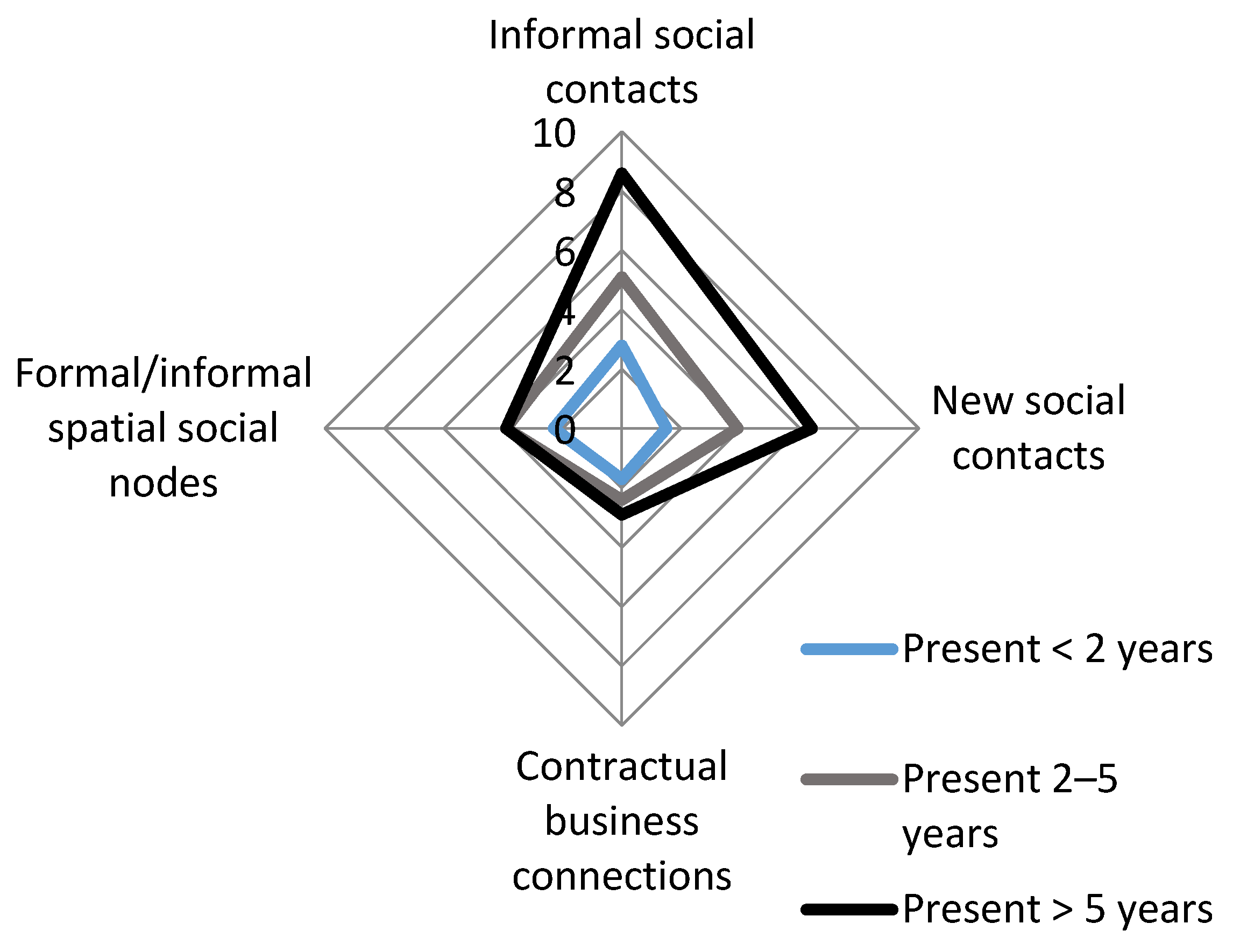

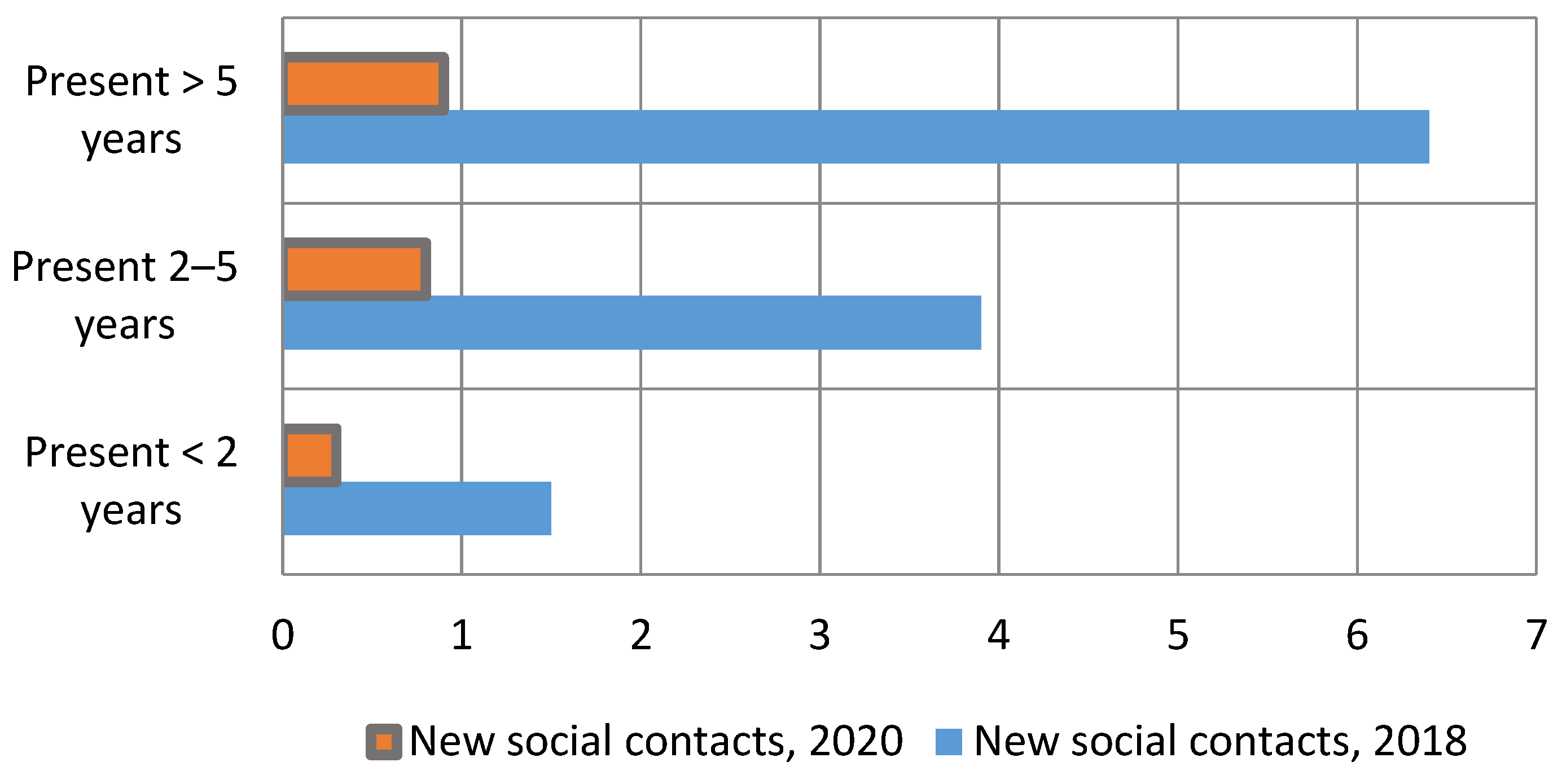

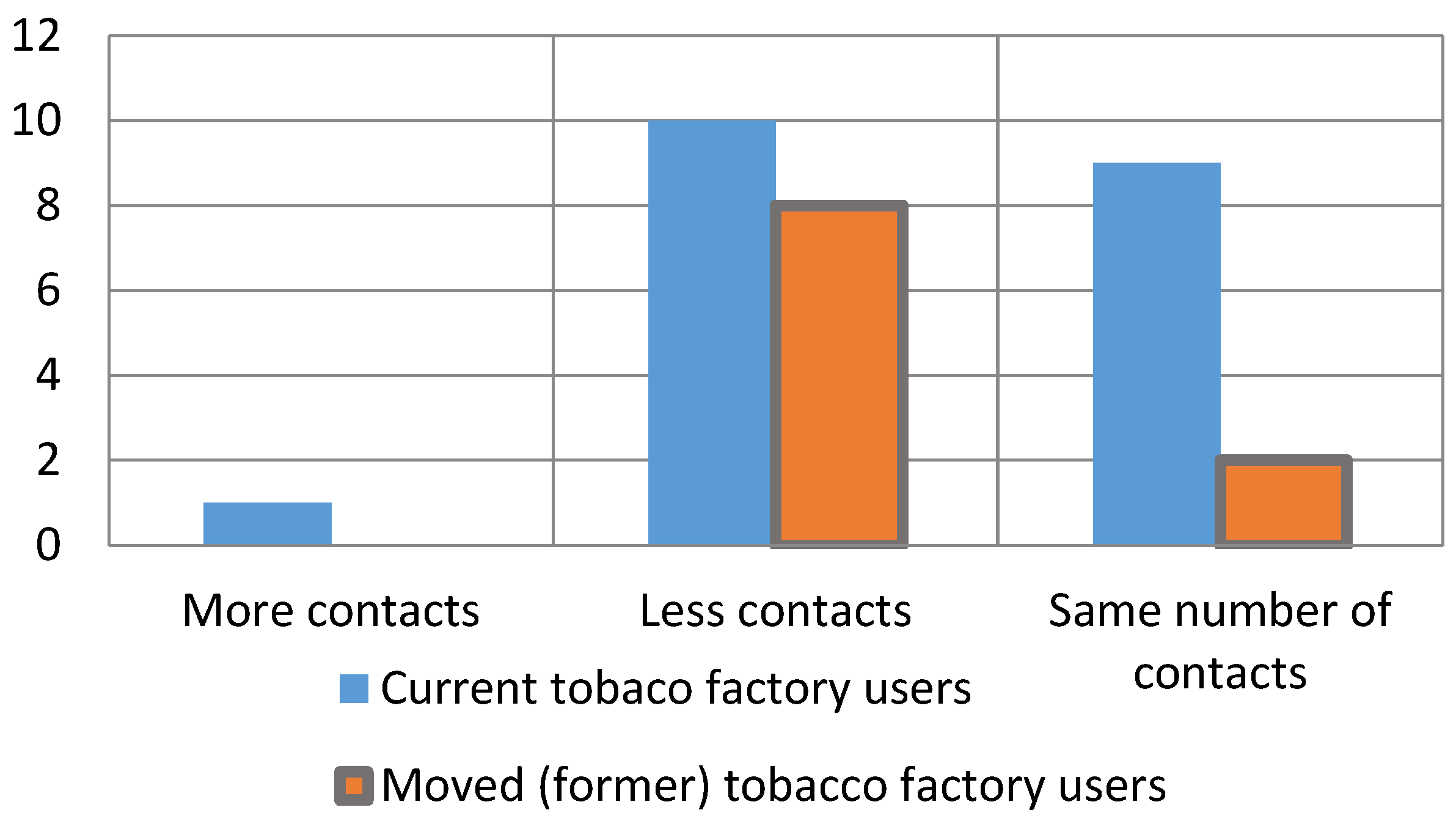

- Scientific value can be found also in the new model of innovative critical reflection that uses social networks in temporary use of space as detectors for analytical deficits in spatial planning (see Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). This model based on the analysed tobacco factory can be applied (replicated) to other spatial procedures found across the whole spectrum of the EU planning system that in the majority of cases, exclude more detailed elaboration of socio-ecological indicators that would use/analyse the type, duration and role of social networks as the standardised principle of spatial planning. The study in this regard elaborates on specific phases at which the classical spatial planning approaches produce deficits in contextual spatial analysis and resort to fast-forward indicators.

- The empirical section allows the replicability of the analytical model in terms of social network analysis in temporary use of space. In particular, the case of the tobacco factory exposed the necessary dimensions of the type, duration and role of social networks that should be taken into analysis. In terms of the replicability and standardisation of analytical process, each location is case specific and should be adapted accordingly. However, the main elements of analysis are exposed and when adequately used or integrated into spatial planning, each of these factors can significantly influence the perception of decision makers regarding the need for inclusion, participation of specific groups that during the period of temporary use helped develop the areas through their physical work, development of local economies, use of services and other beneficial effects on liveability.

- The study also presented particular shortcomings in spatial planning that follows a linear one-dimensional approach and paves the way for collateral damaging processes on locations. The empirical section in this regard used socio-ecological indicators to provide new insights into particular problems of the management of temporary uses of space in degraded areas that extend beyond the selected locations of the LX Factory, Prisão Paraíso and Beyond Construction Site. For example, the problems associated with gentrification, diminishment of the quality of life and reduced resilience of local economies in contemporary cities are deeply connected to deficits in socio-spatial locational analysis within the processes of spatial planning [3,5,15].

- Last but not least, the shift in urban governance should be preceded by the shift in the use of tools and mechanisms that support more sustainable processes of spatial transformation [9,86,87]. An alternative perspective on urban planning that is grounded in promoting social justice, equality and a higher standard of living in addition to material resources should be taken into account. For this reason, current approaches that try to quantify the social and cultural worth of a particular productive ecosystem on site are typically associated with short-term economic models rather than social ones. Techniques for “measuring non-monetary values” [121] (p. 436), or non-material, intangible values in a particular area, should receive more attention because it appears that certain significant aspects of a productive ecosystem may be overlooked when employing a superficial evaluation scheme.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colomb, C. Pushing the Urban Frontier: Temporary Uses of Space, City Marketing, and the Creative City Discourse in 2000S Berlin. J. Urban Aff. 2012, 34, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, P. From the Subversive to the Serious: Temporary Urbanism as a Positive Force. Archit. Des. 2015, 85, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, M. The Seductions of Temporary Urbanism “Saving” the City: Collective Low-Budget Organizing and Urban Practice. Ephemera 2015, 15, 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Madanipour, A. Temporary Use of Space: Urban Processes between Flexibility, Opportunity and Precarity. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1093–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Q.; Dovey, K. Temporary and Tactical Urbanism: (Re)Assembling Urban Space; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-032-25653-5. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Catalyst: The Power of Temporary Use; Oswalt, P., Overmeyer, K., Misselwitz, P., Eds.; DOM Publishers: Berlin, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-3-86922-261-5. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, P. Temporary Public Spaces: A Technological Paradigm. J. Public Space 2016, 1, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honeck, T. From Squatters to Creatives. An Innovation Perspective on Temporary Use in Planning. Plan. Theory Pract. 2017, 18, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M. Ephemera, Temporary Urbanism, and Imaging. In Imaging the City; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 361–396. ISBN 978-0-429-33521-1. [Google Scholar]

- Inti, I. Che Cos’ è Il Riuso Temporaneo? Territorio 2011, 2011, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruijt, H. Is the Institutionalization of Urban Movements Inevitable? A Comparison of the Opportunities for Sustained Squatting in New York City and Amsterdam. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia; Roy, A., AlSayyad, N., AlSayyad, N., Eds.; Transnational Perspectives on Space and Place; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-7391-0741-6. [Google Scholar]

- Langegger, S. Rights to Public Space Law, Culture, and Gentrification in the American West; Softcover Reprint of the Original 1st Edition 2017; Springer International Publishing Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-82286-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lydon, M.; Garcia, A. Tactical Urbanism: Short-Term Action for Long-Term Change; Island Press/Center for Resource Economics: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-59726-451-8. [Google Scholar]

- Andres, L.; Zhang, A.Y. Transforming Cities Through Temporary Urbanism: A Comparative International Overview; The Urban Book Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-61752-3. [Google Scholar]

- Frediani, A.A.; Cociña, C. “Participation as Planning”: Strategies from the South to Challenge the Limits of Planning. Built Environ. 2019, 45, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdini, R. Temporary Uses in Contemporary Spaces. A European Project in Rome. Cities 2020, 96, 102445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högyeová, M.; Agócsová, Á.; Hajduk, M.; Gažová, D. The Role of Temporary Use of Public Space in Sustainable Development: A Case Study. Period. Polytech. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2023, 31, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Planning in Relational Space and Time: Responding to New Urban Realities. In A Companion to the City; Bridge, G., Watson, S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 517–530. ISBN 978-0-631-21052-8. [Google Scholar]

- Forester, J. The Deliberative Practitioner: Encouraging Participatory Planning Processes; 2. Print.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-262-56122-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kostaki, E.; Frangopoulos, Y.; Makridou, A.; Kapitsinis, N. Participatory Governance for the Temporary Use of Urban Abandoned Areas. A Socio-Spatial Approach to the “Old Hospital” Area in Alexandroupolis, Greece. Cities 2024, 154, 105378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F. City State. In ZONE 1/2: The Contemporary City; Urzone, Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 1–2, 194–199. ISBN 0-942299-22-1. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Thrift, N. Cities: Reimagining the Urban; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-0-7456-2413-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, J. Stretching Beyond the Horizon, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-351-89750-1. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4051-9686-4. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory; Clarendon Lectures in Management Studies; 1. publ. in pbk.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-19-925605-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-7456-2409-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Globalization: The Human Consequences; Reprint; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-231-11429-5. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. Sociology Beyond Societies: Mobilities for the Twenty-First Century; International Library of Sociology; Transferred to Digital Printing; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-415-19089-3. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen, K. Networks, Flows, and Fluids—Reimagining Spatial Analysis? Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2004, 36, 1333–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partnership on Circular Economy and Sustainable Land Use. Handbook—Sustainable and Circular Re-Use of Spaces and Buildings. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/system/files/ged/sustainable_circular_reuse_of_spaces_and_buildings_handbook.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Kasperczyk, Z.; Pazder, D. Komercyjne Tymczasowe Użytkowanie Przestrzeni Jako Narzędzie Kreowania Współczesnego Środowiska Mieszkaniowego—Szanse i Zagrożenia. Śr. Mieszk. 2022, 39, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offe, C. The Utopia of the Zero-Option. Modernity and Modernization as Normative Political Criteria. Prax. Int. 1987, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity; Theory, Culture & Society; Sage Publications: London, UK; Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-8039-8345-8. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Consequences of Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 978-0-7456-0923-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mariano, C.; Gràvalos Lacambra, I.; Di Monte, P. Open Urban Space Regeneration Strategies Based on Urban Welfare: A Project and Experiment in the San Lorenzo District in Rome, Italy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H.; Nicholson-Smith, D.; Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; 33. Print; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-631-18177-4. [Google Scholar]

- Marra, G.; Barosio, M.; Eynard, E.; Marietta, C.; Tabasso, M.; Melis, G. From Urban Renewal to Urban Regeneration: Classification Criteria for Urban Interventions. Turin 1995–2015: Evolution of Planning Tools and Approaches. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2016, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, S.; Steen, T. The Sustainability of Outcomes in Temporary Co-Production. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2019, 33, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydn, F.; Temel, R. Temporary Urban Spaces: Concepts for the Use of City Spaces; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2006; ISBN 978-3-7643-7460-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, P.; Williams, L. The Temporary City; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-415-67055-5. [Google Scholar]

- Andres, L. Differential Spaces, Power Hierarchy and Collaborative Planning: A Critique of the Role of Temporary Uses in Shaping and Making Places. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 759–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardiveau, A.; Mallo, D. Unpacking and Challenging Habitus: An Approach to Temporary Urbanism as a Socially Engaged Practice. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumner, N. Planning for the Unplanned: Tools and Techniques for Interim Use in Germany and the United States; German Institute of Urban Affairs: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Németh, J.; Langhorst, J. Rethinking Urban Transformation: Temporary Uses for Vacant Land. Cities 2014, 40, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mould, O. Tactical Urbanism: The New Vernacular of the Creative City. Geogr. Compass 2014, 8, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D. Tactical Urbanism: Delineating a Critical Praxis. Plan. Theory Pract. 2018, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, S. Tactical Urbanism as a Means of Testing Relational Processes in Space: A Complex Systems Perspective. Plan. Theory 2018, 17, 472–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-520-23699-8. [Google Scholar]

- Deslandes, A. Exemplary Amateurism: Thoughts on DIY Urbanism. Cult. Stud. Rev. 2013, 19, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, D. DIY Urbanism: Implications for Cities. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2014, 7, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iveson, K. Cities within the City: Do-It-Yourself Urbanism and the Right to the City. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, N.; De Klerk, C.; Malhotra, S. Civic Engagement through DIY Urbanism and Collective Networked Action. Plan. Pract. Res. 2015, 30, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, L.; Samson, K. Claiming Participation—A Comparative Analysis of DIY Urbanism in Denmark. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2016, 9, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spataro, D. Against a De-Politicized DIY Urbanism: Food Not Bombs and the Struggle over Public Space. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2016, 9, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J. Insurgent Public Space: Guerrilla Urbanism and the Remaking of Contemporary Cities; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-415-77966-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, J. Guerrilla Urbanism: Urban Design and the Practices of Resistance. URBAN Des. Int. 2020, 25, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, M.; Weiland, U.; Alvarez, A.; Sennett, R. Handmade Urbanism; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-3-86859-225-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mady, C. Diversity in Conviviality: Beirut’s Temporary Public Spaces. Open House Int. 2012, 37, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.J.; Lai, L.W. Property Rights, Planning and Markets: Managing Spontaneous Cities; Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-1-84064-904-8. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. ‘Borrowing’ Public Space to Stage Major Events: The Greenwich Park Controversy. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziehl, M.; Osswald, S.; Schnier, D.; Hasemann, O. Second Hand Spaces: Über das Recyceln von Orten im städtischen Wandel; Recycling Sites Undergoing Urban Transformation; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-3-86859-155-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sandercock, L. Towards Cosmopolis: Planning for Multicultural Cities; J. Wiley: Chichester, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-471-97197-9. [Google Scholar]

- Groth, J.; Corijn, E. Reclaiming Urbanity: Indeterminate Spaces, Informal Actors and Urban Agenda Setting. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 503–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krmpotić Romić, I.; Bojanić Obad Šćitaroci, B. Temporary Urban Interventions in Public Space. Prostor 2022, 30, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, M.T.A.; Sharma, N. LotRec: A Recommender for Urban Vacant Lot Conversion. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.02481. [Google Scholar]

- Grávalos Lacambra, I.; Di Monte, P. Temporary Use Toolkit. Herramientas Para La Reactivación de Edificios En Desuso. ZARCH 2024, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agheyisi, J.E. Temporary Use of Urban Vacant Spaces: A pro-Poor Land Use Strategy in the Global South. J. Urban Aff. 2025, 47, 978–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Deas, I.; Hincks, S. The Role of Temporary Use in Urban Regeneration: Ordinary and Extraordinary Approaches in Bristol and Liverpool. Plan. Pract. Res. 2019, 34, 537–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanipour, A. Cities in Time: Temporary Urbanism and the Future of the City; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4742-2071-2. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.; Hincks, S.; Deas, I. Temporary Use in England’s Core Cities: Looking beyond the Exceptional. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3381–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karachalis, N. Temporary Use as a Participatory Placemaking Tool to Support Cultural Initiatives and Its Connection to City Marketing Strategies—The Case of Athens. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smet, A. The Role of Temporary Use in Urban (Re)Development: Examples from Brussels. J. Res. Bruss. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardigno, R.; Mininni, G.; Cicirelli, P.G.; D’Errico, F. The ‘Glocal’ Community of Matera 2019: Participative Processes and Re-Signification of Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G. Circular Economy Strategies for Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage Buildings to Reduce Environmental Impacts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. ISBN 978-0-313-23529-0. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Tuning In, Tuning Out: The Strange Disappearance of Social Capital in America. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 1995, 28, 664–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, S. The social logic of subcultural capital. In The Subcultures Reader; Gelder, K., Thornton, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 200–209. ISBN 0-415-12727-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ursic, M. Managing Cultural Diversity in the City: Exclusion/Inclusion of (Sub)Cultures as a Factor for Urban Regeneration. In Culture and the City; Eckardt, F., Ed.; Berliner Wissenschafts: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 85–102. ISBN 3-8305-1640-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ursic, M.; Imai, H. Creativity in Tokyo: Revitalizing a Mature City; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981-15-6686-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development: Defining Urban Social Sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; Redmond, D. Location Factors of Creative Knowledge Companies in the Dublin Region; The Managers’ View; AMIDSt, University of Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; ISBN 978-90-75246-93-3. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Brelot, H.; Grossetti, M.; Eckert, D.; Gritsai, O.; Kovács, Z. The Spatial Mobility of the ‘Creative Class’: A European Perspective. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 854–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musterd, S.; Gritsai, O. The Creative Knowledge City in Europe: Structural Conditions and Urban Policy Strategies for Competitive Cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2013, 20, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, E.; Laprise, M.; Lufkin, S. Urban Brownfields: Origin, Definition, and Diversity. In Neighbourhoods in Transition; The Urban Book Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 7–45. ISBN 978-3-030-82207-1. [Google Scholar]

- Jacek, G.; Rozan, A.; Desrousseaux, M.; Combroux, I. Brownfields over the Years: From Definition to Sustainable Reuse. Environ. Rev. 2022, 30, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.J.; Newman, G. A Classification Scheme for Vacant Urban Lands: Integrating Duration, Land Characteristics, and Survival Rates. J. Land Use Sci. 2019, 14, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, L.; Ferber, U.; Grimski, D.; Millar, K.; Nathanail, P. The Scale and Nature of European Brownfields; LQM Ltd.: Nottingham UK; Belfast, UK, 2005; pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bergatt Jackson, J.; Ferber, U.; Górski, M.; Nathanail, P. Brownfields Handbook; Leonardo da Vinci Project; VŠB-TU Ostrava: Poruba, Czech Republic, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Evert, K.-J.; Ballard, E.B.; Elsworth, D.J.; Oquiñena, I.; Schmerber, J.-M.; Stipe, R.E. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Landscape and Urban Planning: = Diccionario Enciclopédico—Paisaje y Urbanismo = Dictionnaire Encyclopédique Du Paysage et de l’urbanisme = Enzyklopädisches Lexikon—Landschafts-Und Stadtplanung; SpringerLink Bücher; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3-540-76455-7. [Google Scholar]

- Špes, M.; Krevs, M.; Lampič, B.; Mrak, I.; Ogrin, M.; Plut, D.; Vintar Mally, K.; Vovk, A.; Bec, D. Sonaravna Sanacija Okoljskih Bremen Kot Trajnostno Razvojna Priložnost Slovenije. Degradirana Območja: [Ciljni Raziskovalni Program (CRP) “Konkurenčnost Slovenije 2006-2013”]: Zaključno Poročilo; Oddelek za Geografijo Filozofske Fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lampič, B.; Cigale, D.; Kušar, S.; Potočnik Slavič, I. Celovita Metodologija za Popis in Analizo Degradiranih Območij, Izvedba Pilotnega Popisa in Vzpostavitev Ažurnega Registra: Končno Poročilo; Filozofska fakulteta Univerze v Ljubljani, Fakulteta za Gradbeništvo in Geodezijo Univerze v Ljubljani, Geodetski Inštitut Slovenije: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grimski, D.; Ferber, U. Brownfields and Redevelopment of Urban Areas; Federal Environment Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, J.W. Brownfields and Greenfields: The Intersection of Sustainable Development and Environmental Stewardship. Environ. Pract. 2003, 5, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieto, L. Studi di Caso in Pianificazione Territoriale: Una Introduzione Allo Studio di Caso Come Metodo di Ricerca; Gianni Fovana Editore: Omegna, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Applied Social Research Methods Series; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7619-2552-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cotič, T. Temporary Use of Space as a Factor in the Revitalisation of Degraded Urban Areas in the City of Koper (Začasna Raba Prostora Kot Dejavnik Revitalizacije Degradiranih Urbanih Območij Mesta Koper. Ph.D. Thesis, Univeristy of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Education Live. UEL—Skupnost Tobačna (Tobacco Factory Community): Final Research Report—Phase 3; Faculty of Social Sciences, Centre for Spatial Sociology: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Jensen, A.; Fullerton, B.; Holt-Jensen, A. Geography, History and Concepts: A Student’s Guide, 2nd ed.; Chapman: London, UK, 1988; ISBN 978-1-85396-011-6. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and Discussions, First printing; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-1-884156-11-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. SAGE Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4129-7266-6. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. In Proceedings of the 2000 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2–6 December 2000; p. 357. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Hope; California Studies in Critical Human Geography; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-520-22577-0. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-415-13255-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S. Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places, Softcover ed.; Oxford Univ. Pr.: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-19-979446-1. [Google Scholar]

- Koželj, J.; Filipič, P.; Hočevar, P.; Strle, K.; Kušar, K. Merila in Kriteriji Za Določitev Degradiranih Urbanih Območij—DUO 2; Univeristy of Ljubljana: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, R.C.; Rodrigues, G.S. A System of Integrated Indicators for Socio-Environmental Assessment and Eco-Certification in Agriculture—Ambitec-Agro. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2006, 1, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Vargas, M.; Bermúdez-Roja, T.; Duque-Gutiérrez, M. Evaluación Cualitativa de Indicadores de Sostenibilidad Socioambiental Para Su Selección y Aplicación En Ciudades Costarricenses. Rev. Geográfica América Cent. 2019, 1, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, P.R. Environmental Governance of the São Paulo Macrometropolis: Perspectives on Climate Variability, 1st ed.; The Urban Book Series; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-59610-0. [Google Scholar]

- Murie, A.; Musterd, S. Making Competitive Cities; Real Estate Issues; Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4051-9415-0. [Google Scholar]

- Grabher, G. Learning in Projects, Remembering in Networks?: Communality, Sociality, and Connectivity in Project Ecologies. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2004, 11, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunsberger, F.; Hlavaty, M.; Schlamberger, N.; Stevanovič, S. Standardna Klasifikacija Dejavnosti 2008; Statistični urad Republike Slovenije: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2010; ISBN 978-961-239-156-0. [Google Scholar]

- Žaucer, T.; Peterlin, M.; Uršič, M.; Očkerl, P.; Marn, T.; Murovec, N. Kreativna Urbana Regeneracija: Priložnosti v Ljubljanski Urbani Regiji = Creative Urban Regeneration: Potentials in the Ljubljana Urban Region; IPoP, Inštitut za politike prostora: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2012; ISBN 978-961-92936-6-9. [Google Scholar]

- IPoP, Institute for Spatial Policies. Potentials of Creative Urban Regeneration; IPoP, Inštitut za Politike Prostora: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Filipovič Hrast, M. Prostorska Determiniranost Omrežij Starejših in Vloga Sosedov v Časovni Perspektivi. Teor. Praksa 2017, 44, 298–316. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, J.; Nara, A.; Appleyard, B. Exploring the Imprint of Social Media Networks on Neighborhood Community Through the Lens of Gentrification. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2018, 45, 470–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Liu, X. Integrating Social Networks and Spatial Analyses of the Built Environment. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2018, 45, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; The MIT Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1996; ISBN 978-0-262-12004-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Reprinted; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-0-631-14048-1. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, K. Cultural Built Heritage as a Strategy. In City and Culture: Cultural Processes and Urban Sustainability; Nyström, L., Fudge, C., Eds.; Swedish Urban Environment Council [Stadsmiljörådet]: Kalmar, Sweden, 1999; pp. 430–444. ISBN 91-7147-529-X. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Sub-Indicators |

|---|---|

| FUNCTIONAL DEGRADATION |

|

| PHYSICAL DEGRADATION |

|

| SPATIAL FRAMING INDICATORS |

|

| STRATEGIC SPATIAL PLANS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT |

|

| Category | Sub-Indicators | Examples of Further (Refined) Elaboration of Sub-Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| FUNCTIONAL DEGRADATION | maintenance of infrastructure on location | The level of maintenance is assessed according to the level of preservation of existent infrastructure; for example:

|

| evaluation of traffic accessibility | The location of the area is assessed according to the distance (air distance) of the nearest point of the degraded area from the road of the corresponding category; for example:

| |

| level of abandonment |

| |

| PHYSICAL DEGRADATION | activity, influence on natural elements (water, soil, air, vegetation) | Assessment of the potential negative impact of the implementation of activities on water, soil, air, vegetation, surface; an expert assesses suspected environmental degradation:

|

| SPATIAL FRAMING INDICATORS | time (duration) of abandonment | Estimation of the duration of abandonment—the longer the site is abandoned, the more likely the level of its physical degradation will be high:

|

| STRATEGIC SPATIAL PLANS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT | general strategic documents, at the level of state, region, municipality | Estimation of planning definition: dominance of particular dedicated use (75% and more of the area is dedicated) according to envisioned spatial plans:

|

| Dimension/Location | LX Factory (Lisbon, Portugal) (see Figure 6) | Prisão Paraíso (Trafaria, Portugal) (see Figure 7) | Beyond a Construction Site (Ljubljana, Slovenia) (see Figure 8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous use (history) of the degraded area | Industrial area (textile, food, printing) until the 1990s. Located in the neighbourhood of Alcântara. | Military prison until 1981, later abandoned. Located in Setubal (municipality of Almada). | Abandoned construction site after investor insolvency. Located in Ljubljana central area. |

| Temporary use of the area | Site repurposed by a private investor for creative industries, cultural production and leisure spaces. Industrial heritage was used as economic and aesthetic leverage, with limited community involvement. | Cultural and social activation initiated by the municipality in collaboration with the EDA collective, focusing on art, education and community events. Temporary use helped shape the vision for future institutional functions. | Initiated by a local NGO as a bottom-up community project involving residents in co-creating green spaces, urban gardens and a public program of temporary use. Strong local engagement was present on the site. |

| Description of redevelopment process in the degraded area | Top-down approach is noticeable. Private owners are focused on monetization and market-driven uses. Temporary use served as a transitional phase with minimal social integration and deprivation of or participatory elements for marginal stakeholders in the process. | Predominantly bottom-up approach with minor presence of top-down components. The temporary activities that were set up before redevelopment represented the basic structure of activities in the post-redevelopment period and helped set the future plans for the area through collaboration with institutional stakeholders and civil society. | Predominantly top-down approach with minor bottom-up components. Temporary use ended with the redevelopment of the area into social housing. Despite strong local engagement during the temporary use phase, this participatory potential was not preserved after the end of the project. |

| Inclusion of socio-ecological indicators in the process of redevelopment of the area | Mainly physical indicators (e.g., safety, accessibility) were applied in the redevelopment process. Socio-environmental aspects were secondary. Social networks were not preserved during or supported after the redevelopment, and the community had/has limited influence on redevelopment and new activities on site. | Both socio-environmental and physical–environmental indicators were used in the redevelopment process. This balanced approach allowed synergies between the owners (municipality), temporary users and local community. Cooperation between stakeholders helped select permanent sustainable uses and contents for the area. | Socio-environmental indicators were used in the pre-redevelopment period to spark local community engagement and uses. This potential was abolished during the redevelopment where prevalently physical–environmental indicators were used in the process by the owners (municipality). After redevelopment, residual elements of social knowledge and networks were partially transferred to other local initiatives in the city (e.g., Creative Laboratory, Krater). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uršič, M.; Cotič, T. The Limited Role of Socio-Ecological Indicators in Temporary Use of Space—Deficits in Revitalization of Degraded Urban Areas. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115224

Uršič M, Cotič T. The Limited Role of Socio-Ecological Indicators in Temporary Use of Space—Deficits in Revitalization of Degraded Urban Areas. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115224

Chicago/Turabian StyleUršič, Matjaž, and Tina Cotič. 2025. "The Limited Role of Socio-Ecological Indicators in Temporary Use of Space—Deficits in Revitalization of Degraded Urban Areas" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115224

APA StyleUršič, M., & Cotič, T. (2025). The Limited Role of Socio-Ecological Indicators in Temporary Use of Space—Deficits in Revitalization of Degraded Urban Areas. Sustainability, 17(11), 5224. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115224