Abstract

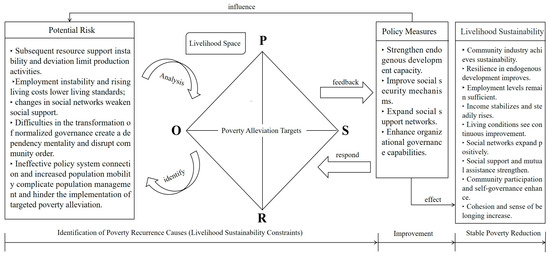

With the nationwide completion of China’s large-scale Poverty Alleviation Relocation (PAR) initiative in 2020, the government’s poverty alleviation efforts have officially entered the “post-poverty era”. However, many regions still lack well-established sustainable development mechanisms and face a potential risk of returning to poverty. To better stabilize the achievements of poverty alleviation, this study examines the potential risk of returning to poverty after the first Five-Year Transition Period (2021–2025) from a livelihood space perspective and proposes optimization directions for PAR policies in future poverty reduction efforts. Research findings indicate that simply altering geographical conditions is insufficient to achieve stable poverty alleviation. The production space of relocated populations is vulnerable to the stability and precision in resource supply, which may lead to recurring poverty due to policy discontinuities and administrative preferences. Meanwhile, improvements in living spaces are constrained by imbalances in household income and expenditure. This study also found that, on the one hand, changes in residential patterns break the original boundaries of administrative villages by incorporating migrants from different villages into concentrated communities, leading to the expansion of weak-tie networks while, on the other hand, the relocation process disrupts some of the migrants’ original strong-tie networks, and the concentration and clustering of impoverished groups in relocation communities further lead to the contraction of these networks. Additionally, the unique characteristics of relocation communities generate exorbitant governance costs and population management difficulties that far exceed the service provision and administrative capacities of community organizations. In the long run, this situation proves detrimental to normalized community governance and dynamic poverty relapse monitoring and interventions. Accordingly, this study proposes relevant policy recommendations from the following four aspects, i.e., strengthening endogenous development capacity, improving social security mechanisms, expanding social support networks, and enhancing organizational governance capabilities, aiming to provide both a theoretical basis and a decision-making reference for future poverty alleviation efforts.

1. Introduction

For long periods, poverty has stood as a critical developmental challenge confronting nations and regions worldwide. The first goal of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development explicitly commits to eradicating poverty in all its forms and manifestations across the globe [1]. From a global perspective, both developed and developing nations have formulated diverse poverty alleviation strategies tailored to their domestic situation. Notable examples include the welfare policies of Nordic and Western European countries, Pakistan’s Ehsaas Program and Benazir Income Support Program (BISP) coupled with microfinance initiatives [2], Brazil’s Continuous Cash Benefit (BPC) and Bolsa Familia Program (BFP) [3], Bangladesh’s Targeting the Ultra-Poor (TUP) policy for rural women in extreme poverty [4], India’s unconditional universal income transfer scheme [5], and Mexico’s Education, Health, and Nutrition Program (Progresa) [6]. The policies implemented by these countries for poverty reduction vary in their focal points, such as emphasizing the rural sector, raising minimum wage standards and developing preferential policies for special groups. In contrast to these conventional strategies, China’s poverty reduction model and achievements in recent decades demonstrate distinctive characteristics. As the largest developing nation, China once harbored the world’s largest impoverished rural population [7]. However, over the past few decades, the Chinese government adopted the geographical determinism of poverty as a guiding theory to implement Poverty Alleviation Resettlement (PAR) at the national level, achieving widely recognized progress. Through PAR, the government relocated populations inhabiting ecologically fragile and disaster-prone areas to centralized resettlement sites with improved infrastructure and accessibility. This intervention fundamentally addressed the regional “poverty accumulation” trap caused by environmental degradation, frequent geological hazards and endemic diseases, thereby disrupting the vicious cycle of intergenerational poverty transmission [8]. By 2020, China had lifted 98.99 million people out of poverty across 832 impoverished counties and 128,000 impoverished villages, accomplishing regional holistic poverty eradication a decade ahead of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) timeline. This achievement provides valuable empirical insights for poverty reduction efforts in other developing regions [9].

In general, PAR in China has evolved from localized pilot projects addressing specific regional issues to a nationally coordinated, large-scale strategy. The program originated from the “Diaozhuang resettlement” in the 1980s in China’s Sanxi region—encompassing Xihaigu (Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region), Hexi and Dingxi (Gansu Province). It successfully addressed China’s severe water scarcity issue for the first time through planned relocation initiatives. From 2001 to 2005, pilot resettlement initiatives expanded nationwide, evolving into localized policy prototypes including Ecological Resettlement, Disaster Avoidance Relocation and so on. During this phase, relocation efforts remained limited in scale, with policy frameworks undergoing iterative refinement. By 2011, with the enactment of the “Outline of Poverty Alleviation and Development in Rural China (2011–2020)” and the “Twelfth Five-Year Plan for Relocation to Poverty Alleviation”, China entered a new era of Targeted Poverty Alleviation (TPA). Contiguous areas of dire poverty became focal areas for large-scale relocation programs. In 2015, the Central Poverty Alleviation Conference formally integrated relocation into the “Five Priority Tasks” for precision poverty reduction, mandating a five-year plan to register populations in “areas where local resources could no longer sustain the population”. The 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020) set an ambitious target to relocate 10 million people, ensuring their integration into a comprehensively well-off society. By 2020, China had established 39,000 centralized resettlement communities, including nearly 50 mega-communities each accommodating over 10,000 residents—equivalent to relocating a population comparable to that of a mid-sized nation [10]. This unprecedented achievement stands as a landmark in global development history.

While the PAR program has demonstrated significant poverty reduction potential, the inherent vulnerability of relocated populations means their livelihood sustainability remains confronted with rigorous tests. Some regions still exhibit persistent high incidence of re-impoverishment among relocated households, coupled with insufficient endogenous development momentum in communities and inadequate long-term safeguard mechanisms. According to the “Guiding Opinions on Establishing the Monitoring and Assistance Mechanism to Prevent Relapse into Poverty (2020)”, the current and future priority lies in effectively transforming state-embedded poverty alleviation resources into stable livelihood systems and sustainable development for relocated populations, thereby addressing latent re-impoverishment risks and avoiding the “poverty–poverty alleviation–return to poverty” vicious cycle.

Within this context, numerous studies have evaluated the influence of PAR on livelihood capital and strategies [11,12,13,14], household well-being and ecosystem service dependence [15,16], livelihood sustainability and poverty alleviation stability [17,18,19,20,21] and livelihood vulnerability and resilience [22,23]. Correspondingly, some scholars have discussed the cause of poverty governance failures in some out-migrating areas from the perspectives of bureaucracy, management mechanism and local government action strategy. For example, the authors of some studies believe that local governments are forced to adopt a series of coping strategies under huge assessment pressure and campaign-style governance, thus distorting the original intention [24]. Another study proposed the concept of relational poverty governance, emphasizing how formal and informal interactions between poverty alleviation cadres and households become pivotal for project implementation; yet, this model’s heavy fiscal and human resource costs raise sustainability concerns once external support withdraws post-target completion [25]. In addition, some studies have applied the theories of the geographical school to analyze the distribution characteristics and causes of poverty-stricken areas, finding that the distribution of the Chinese rural poor exhibits a distinct spatial agglomeration [26,27]. On this basis, PAR, as a typical spatial restructuring process, has drawn researchers’ attention. Some studies have recognized that the type of spatial restructuring based on residential segregation is an important factor in shaping resettlement outcomes [28,29].

While these studies provide valuable enlightenment, several limitations persist: (1) Although substantial scholarly work has explored the interconnection between poverty alleviation policies and livelihood, scholarly attention remains predominantly focused on the relocation phase, while livelihood issues in the post-poverty era continue to suffer from inadequate analytical depth. (2) Numerous studies focused more on macro-scale poverty at the county level and predominantly employed quantitative methodologies by utilizing objective-level measurable indicators for top-down macro analysis. However, as a “policy testing ground” for poverty reduction, relocation communities serve as more ideal units for examining the stability of China’s poverty alleviation achievements, enabling researchers to better identify specific practical issues affecting the effectiveness of anti-poverty policies from within these communities. (3) Although correlations between space and poverty have been acknowledged, studies related to spatial poverty traps primarily serve as a theoretical framework to demonstrate the rationale for implementing PAR, still lacking explanatory power regarding persistent livelihood challenges in the post-poverty era. (4) Many studies attribute the impact of space on poverty to a single geographical or environmental factor. For example, they evaluate the impact on relocated populations based solely on the spatial classifications of resettlement types, or they focus only on how transportation accessibility after relocation affects poverty reduction. This simplifies the understanding of spatial poverty and neglects the multidimensionality and the phased characteristics of poverty governance.

As mentioned earlier, there is still room for further discussion of PAR program’s achievements. This paper summarizes the poverty reduction strategies adopted by the government within the PAR project from the perspective of livelihood space and focuses on analyzing the effectiveness of these strategies in poverty alleviation stability as well as the potential risks of returning to poverty during the post-poverty phase. The structure of this paper is as follows:

The first section is an introduction that presents a brief review of anti-poverty initiatives in both developed and developing countries within the context of global poverty governance. Subsequently, it systematically traces the evolutionary trajectory of China’s poverty alleviation efforts over four decades, critically analyzing their implementation achievements and persisting challenges. Section 2 introduces the framework of this study. It briefly summarizes the theoretical basis and background of PAR, explains the necessity of spatial perspectives in studying poverty in China and constructs a livelihood space analytical framework based on these foundations. Section 3 offers a detailed description of the study area, the data collection procedures, and the specific process of data analysis. Section 4 presents the research findings, summarizing the risks of returning to poverty faced by relocated populations from four dimensions of livelihood space. Additionally, it provides a detailed analysis of the causes of different risks of poverty recurrence, supported by specific examples gathered from the research. Section 5 presents the discussion, based on the integration of relevant research findings and comparative analysis and it identifies the limitations of the study. Section 6 presents the conclusion and proposes concrete policy recommendations based on survey findings and lessons from failed resettlement cases internationally.

2. Theoretical Framework

UPTOHERE Human geography research examining the correlation between geographical conditions and poverty can offer significant insights into the relationship between space and livelihoods. In the 1950s, Harris, the founder of new economic geography, proposed that economic development in underdeveloped regions was related to geographical location [30]. In the 1990s, the World Bank initiated extensive research on the spatial distribution characteristics and patterns of global poverty; experts found that some areas showed clustered poverty phenomena. Based on this, Jalan proposed the concepts of “geographical capital” and “spatial poverty traps” (SPTs), arguing that the lack of geographical capital is a main reason for slow capital accumulation, which then leads to the formation of SPTs [31]. Over time, an increasing number of scholars have employed “spatial poverty theory” to identify and analyze poverty issues. The spatial turn in poverty research has provided important theoretical support for China’s poverty alleviation practices over the past 40 years, making people realize the significance of geographical location and conditions in poverty reduction work. “The China Rural Poverty Monitoring Report” shows that, in 2005, 76% of China’s long-term impoverished population lived in resource-scarce and ecologically fragile areas, including deep mountain areas, rocky desertification regions, high-altitude cold zones and the Loess Plateau. Most impoverished areas share similarities with international spatial poverty patterns, demonstrating obvious regional clustering characteristics [32].

However, early scholars’ understanding of spatial poverty mostly focused on geographic location and the occupation of natural resources; they generally believed that changing the natural geographical conditions was a necessary way to eliminate poverty. As research deepened, scholars gradually realized that geographic conditions are only one fundamental element of geographic capital. Consideration for poverty alleviation should not be limited to natural geographical factors, but should expand the connotation of geographic capital to include material capital, social capital, human capital, etc. that reflect spatial geographic attributes. This requires the integration of spatial theory with the concept of “livelihood”. In this regard, important insights can be drawn from relevant studies such as Sen’s Capability Approach, Scoones’s Sustainable Livelihoods Approach and DFID’s Sustainable Livelihoods Framework. In Development as Freedom, Sen points out “Poverty is not just lack of income but also the deprivation of basic capabilities [33]”. He emphasizes the “freedom of choice” and the “freedom of achievement” that individuals possess in the process of pursuing a “valuable life”, forming the “empowerment” and “multidimensionality” concepts of livelihood theory. In 1998, based on research in rural Africa, Scoones proposed that “livelihood” is not only economic activity, but also a comprehensive process of resource access, institutional roles and environmental adaptation. That is, livelihood depends not only on resources that people possess (such as land, skills and tools), but also on the institutional environment in which they are situated and the strategies they adopt. Scoones proposed a widely recognized definition of “sustainable livelihood” as a livelihood system that comprises the capabilities, assets and activities required for a means of living. If this livelihood system can not only cope with and recover from external stresses and shocks, but also maintain or even enhance its capabilities and assets now and in the future, while not undermining the natural resource base, then the livelihood can be considered sustainable [34]. From this perspective, the building of sustainable livelihood capacity runs through the entire process of poverty reduction: first, solving absolute poverty and escaping the absolute poverty trap; then, addressing the problem of returning to poverty and consolidating the achievements of poverty alleviation; and, finally, tackling relative poverty and creating opportunities for upward mobility among the formerly poor. Currently, a series of sustainable livelihood frameworks have been developed in research and policy practice. The most widely accepted is the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) proposed by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) [35]. This framework inherits the “multidimensional development” concept of Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach, integrates Scoones’s theory and makes it operational. The SLF mainly includes five core elements: Vulnerability Context, Livelihood Assets, Transforming Structures and Processes, Livelihood Strategies and Livelihood Outcomes. Livelihood capital is one of the core components of the SLF, referring to the five types of capital required to achieve livelihood goals, namely human, natural, physical, financial and social capital. The SLF emphasizes the structural causes of poverty, highlights the interactive effects of social, economic and environmental factors and stresses the constraints exerted by policy and institutional environments on sustainable livelihood building. On the basis of this theoretical development, many studies have incorporated the structural factors of poverty into spatial analysis. A representative example is the three-dimensional spatial poverty indicator system—economic, social and environmental—proposed by Burke and Bird. Other scholars have included income, consumption, education, healthcare, market connectivity and policy in the measurement scope of geographic capital. This indicates that research on spatial poverty has actually evolved from “geographic capital” to “livelihood space”, shifting from the study of a single physical space to the comprehensive analysis of multidimensional spaces.

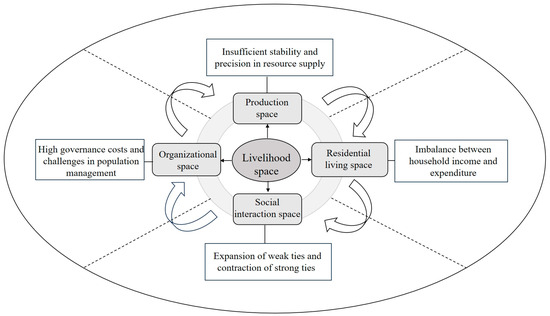

We define “livelihood space” as the livelihood strategies and means of subsistence adopted by residents on the basis of specific natural geographical conditions, relying on a complex system composed of production space, living space, social interaction space and organizational space. Production space refers to the material foundation and resource support system on which individuals or households depend to engage in production activities. Since relocated migrants are still in a transitional period of livelihood transformation, the resources required for industrial development and skills training mainly rely on government-led industrial construction and policy support. Therefore, the dimension of production space focuses on examining the stability and accuracy of government poverty alleviation projects and policy support. The analytical basis lies in assessing the continuous provision of resources such as agricultural and animal husbandry subsidies, skills training and project construction, as well as their match with the actual needs of the poverty-alleviated population. Residential living space refers to the comprehensive space for residence and living activities occupied and utilized by individuals or households within a certain geographical range, which covers basic needs such as clothing, food, housing and transportation. This space includes both infrastructure conditions and public service provision (physical aspect), as well as the changes and adaptation of lifestyles and habits (social aspect). The key analytical indicators for the physical aspect include housing quality, transportation accessibility, infrastructure conditions such as water, electricity and natural gas and the construction conditions of medical and educational facilities. These physical factors directly determine the convenience, safety and comfort of migrants’ lives. The key analytical indicators for the social aspect include adjustments in daily living habits and lifestyles. Social interaction space refers to the places or contexts where members of society establish social connections and engage in interactions, this dimension primarily examines the interactions and connections among people and the resulting social support networks. Drawing on Granovetter’s study on the “strength of ties”, we roughly classify the existing social relationships of migrants into strong ties and weak ties. With predetermined measurement dimensions such as the content of information exchange, the situation of mutual assistance in production and living activities and the total amount of communication time as references, respondents are asked to assess by themselves which people in the community have good relationships with them, which have ordinary relationships and which have no relationships. On this basis, we examine the development trends of strong and weak ties in the social interaction space and their influence on immigrants’ access to social support. Organizational space refers to the governance field constructed by grassroots community management institutions and various organizations in a specific community. This space carries the allocation of organizational resources and coordination of functions, as well as decision-making and execution processes. The good operation of organizational space can promote the normalization of community order and create a stable institutional environment for livelihood activities. The key analytical indicators focus on the actual functional performance of governance entities in service provision and effectiveness in addressing livelihood issues. The selected indicators include the types and quality of public services provided by the organization, personnel allocation, service coverage and residents’ participation.

These four spaces are interrelated and intertwined, and only through coordinated improvement of quality in all dimensions can the overall quality of the livelihood space for relocated groups be improved (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Framework for livelihood space.

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Study Area

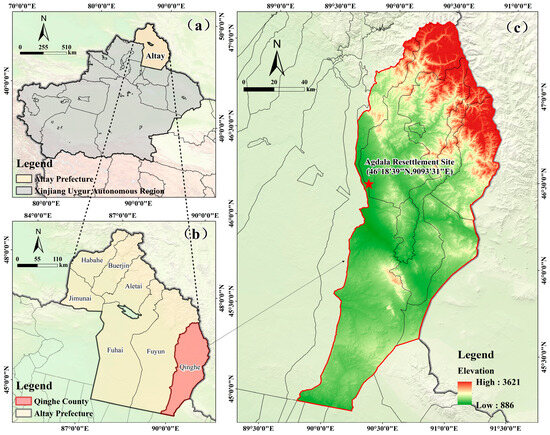

This study selected the Agdala Resettlement Site in Qinghe County, Altay Prefecture, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China, as the case area (Figure 2). The site is situated on the northern edge of the Junggar Basin, within a piedmont alluvial fan geomorphological zone. The terrain is generally flat, surrounded by low hills, gobi, desert and barren land. This region features a typical temperate continental arid climate with low annual precipitation, high evaporation, dry air and long, cold winters, while summer and autumn are short; it is also one of the few high-cold areas in the country. The Agdala Resettlement Site covers a total area of 381 square kilometers and was developed between 2010 and 2016. It includes three residential communities and one administrative village. Since 2017, the site has accommodated 1046 households (4228 people) through cross-township relocation, including 852 registered impoverished households (3458 people). Most of the relocated population came from impoverished villages in surrounding townships, with a population primarily composed of Kazakhs. The area was originally an uninhabited expanse of gobi and desert. As it undertook more than two-thirds of the county’s poverty alleviation relocation tasks, it was planned and developed as a centralized resettlement site for relocated populations, becoming the core area for poverty alleviation efforts in Qinghe County.

Figure 2.

Case study area. (a) Regional map showing the location of Altay Prefecture in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. (b) Regional map showing the location of Qinghe County in Altay Prefecture. (c) Topographic map showing the specific location of the Agdala Resettlement Site.

The local government implements resettlement through a compensation method involving the demolition and replacement of original homesteads, with each person allocated approximately 10 mu (1.6 acres) of land. At the same time, migrant households can choose the appropriate type of housing from a range of 60–80 square meters, depending on family size and economic conditions, bearing themselves a part of the construction costs of the housing. Old people without offspring and orphans enjoy free housing provided by the government and can also choose to be centrally supported in homes for the aged or social welfare institutions. Due to limited grazing pastures, the local government has been actively promoting modern agriculture in irrigated areas, developing agricultural products such as sea buckthorn, potatoes and organic wheat. Through measures including establishing income guarantee policies for land transfer operations in irrigated areas, implementing labor employment transfer support policies, vocational training support policies and setting up financial service stations, the government has assisted immigrants in improving or rebuilding their livelihoods. Currently, six enterprises have settled in the 1200-acre agricultural by-products processing zone, with four additional companies including organic fertilizer plants and industrial drying plants now under establishment and preparation. As the largest concentrated relocation site in Xinjiang, this settlement faces significant sustainability challenges due to tight relocation schedules and strenuous poverty alleviation tasks. Therefore, selecting Agdala as a specific regional case study demonstrates a certain degree of typicality for qualitative research, providing important practical and theoretical value for understanding the risk of poverty recurrence in the post-poverty alleviation era.

3.2. Material Collection

The research data come from field investigations conducted by the research team in the Agdala relocation and resettlement area between May 2024 and March 2025. The opportunity to conduct this investigation was made possible by our involvement in the PAR project evaluation and planning work. As an external planning agency hired by the Project Management Office, our main responsibility was to investigate the development of the community and to formulate a five-year transitional project plan. During the long-term stay, we gradually established a relationship of trust with community residents and administrators, which created favorable conditions for data collection.

In the selection of research methods, we mainly adopted qualitative research methods, including semi-structured interviews, participatory observation, focus group discussions and policy document analysis, in order to obtain data through multiple channels. Qualitative research allows for greater attention to the specific context in which research participants are situated and is more suitable for exploring the underlying mechanisms behind complex social phenomena [36]. It is helpful for understanding “why” and “how” new risks of returning to poverty emerge among relocated populations after the implementation of PAR [37]. When selecting research participants, we mainly included four groups: first, two poverty alleviation officers from the Township Government Poverty Alleviation Office; second, three community development committee officers responsible for specific community affairs; third, three village officials familiar with the relocation group; and, fourth, 80 migrants who had relocated to the Agdala resettlement area through PAR. The specific inclusion criteria for selecting research participants were as follows: (i) Migrants participating in interviews had to be at least 18 years old, be explicitly identified as poverty alleviation targets in the PAR project, have relocation experience and have resided in the community for more than half a year. (ii) Interviewed officials had to be engaged in poverty alleviation-related work at the Agdala resettlement site and have some understanding of community development and related policies. (iii) After being informed of the purpose of the research, participants had to be willing to cooperate in interviews, observations and subsequent follow-ups. The demographic characteristics of the semi-structured interview participants are summarized in Table 1. The interview questionnaire was mainly designed based on previous survey experience, literature in the relevant field and the theoretical analytical framework (Table 2). In order to improve the reliability and validity of the interview questionnaire, we first adopted the expert review method and pre-test method; that is, two senior experts in the field of migration sociology were invited to assess and score the questionnaire items from the perspectives of content relevance and expression accuracy and revisions were made based on their suggestions. In addition, we conducted a small-scale pre-test of the preliminary interview to check whether the questions reflected actual experience and to further optimize the wording of the items. Second, we used member checking, where the interview results were returned to the interviewees for confirmation. Finally, through multiple rounds of interviews with different groups of interviewees, we compared the consistency of responses from different participants to the same question and conducted secondary follow-up interviews with some of the respondents to ensure the consistency and reliability of data collection.

Table 1.

Demographics of the interviewees (N = 48).

Table 2.

Outline of the interview guide.

The specific data collection process was as follows: First, we used the snowball sampling method, starting from “seed samples” with different identities (including two government officers, three community officers, three village officers and six migrants) and conducted preliminary semi-structured interviews with these participants in May and June 2024. On this basis, we further refined the interview outline. Subsequently, in July 2024, September 2024 and March 2025, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 34 migrants and organized two focus group discussions involving a total of 40 participants. In each round of interviews, participants were encouraged to recommend other participants with different backgrounds, striving to cover individuals with diverse gender, age, occupation, economic status and family structure as much as possible, in order to ensure the diversity and broadness of the sample. Each interview lasted approximately 60 to 90 min and was audio-recorded in Chinese throughout the process. To protect the privacy of participants, all participants were anonymized. In addition, as members of the external planning agency’s working group, we were able to reside in the community for the long term, living together with the respondents, which provided strong conditions for conducting long-term participatory observation. Participatory observation was conducted in various locations, including residents’ homes, recreation squares, production workshops, streets and meeting rooms. At the same time, we also made use of relevant literature from the CNKI and Science Direct databases, such as newspapers, books, journals and government documents (including national plans, regional city planning schemes and official statistical data). These materials covered poverty alleviation relocation policies and progress at various levels, helping us to comprehensively understand the research topic.

3.3. Data Analysis

In this study, the original data were transcribed into text, and then thematic analysis was used to analyze the text. Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analyzing and interpreting themes within qualitative data [38]. The process mainly consists of six steps: familiarizing oneself with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and producing the report. We analyzed the collected data in detail according to these steps.

The first step is familiarizing oneself with the data. In this process, the research team repeatedly read and proofread the interview transcripts and observation notes. Based on the content of the text materials and considering the respondents’ tone and emotional reactions at the time, both the surface semantics and the deeper meanings of the text were comprehensively judged. In cases where the semantics were ambiguous or there was ambiguity, the research team referred back to the original recordings to ensure an accurate understanding of the respondents’ intentions and the context.

The second step is generating initial codes. At this stage, we adopted an open coding strategy and analyzed the text data paragraph by paragraph. We first familiarized ourselves with the original statements of the respondents, extracted byte-level segments and paragraphs and then summarized initial codes that were richly detailed and close to the context. We maximized the preservation of the respondents’ expressions and the contextual meaning to avoid preconceived conceptual categorizations.

The third step involved searching for themes. At this stage, the initial codes were summarized, categorized and merged, and experiential concepts were extracted to generate potential themes. By examining the relationships among codes and themes, we integrated and refined some conceptually related codes. First, the preliminary codes were summarized into four themes: government resource provision, residential living conditions, social interaction and community organization operation. Second, in terms of government resource provision, we started from policy and project support and extracted two key concepts: “stability of provision” and “accuracy of provision”. In terms of residential living conditions, we considered both the material and social levels and classified the initial codes into two concepts: “upgrading of infrastructure and public services” and “changes in daily lifestyle and habits”. Regarding social interaction, we analyzed, based on the distinction between “strong ties” and “weak ties”, the impact of the relocation process itself and changes in residential patterns on the development of strong and weak ties and on social support among migrants. In terms of community organization operation, two concepts were extracted, namely “scope of functions” and “community participation”, focusing respectively on the organization’s management of migrants and the migrants’ participation in community public affairs.

The fourth step is reviewing, defining and naming themes. The first task was to examine and proofread each coded datum categorized under a theme, including merging, splitting and streamlining themes as necessary, to ensure that each theme and code was sufficiently supported by data and to avoid an overly broad thematic scope. Considering that the research objective was to identify the multidimensional risk of returning to poverty after PAR, we further refined the codes so that the analysis at different dimensions could effectively connect theoretical abstraction to experiential materials. For example, content related to changes in residential patterns appeared both in the theme of “residential living conditions” and in the theme of “social interaction”, leading to a certain degree of overlap. We split the relevant content into themes that better aligned with the focal points of the interview materials.

The fifth step is defining and naming themes. At this stage, to ensure that the content of each theme was aligned with the overall research question, we simplified theme names as much as possible and integrated them into the four dimensions of the “livelihood space” analytical framework used in this study, in order to deepen understanding of the mechanism through which return-to-poverty risk is generated.

The sixth step is producing the report. In the final stage, we selected typical cases and interview excerpts around each theme for in-depth analysis, focusing on the following questions: How does this theme demonstrate potential risk of returning to poverty? What is the hypothesis supported by this theme? Why are these circumstances caused under this theme?

To ensure the reliability and completeness of the data, all interview materials were independently coded by two researchers. Ambiguities were resolved through collective discussion for interpretive integration. In addition, the research team conducted secondary follow-up interviews with some respondents during the data analysis process to ensure that the explanations matched the original context. Finally, in assessing the sufficiency of data collection, the study conducted a second round of focus group interviews based on the “theme saturation” criterion. After finding that no new themes or concepts emerged from the interview materials, it was determined that data collection had covered the core dimensions required for the research.

4. Findings

4.1. The Expansion of Production Space Is Restricted by the Stability and Precision of Resource Supply

From the perspective of the migration route, the migration space of poor people in the Agdala resettlement site does not break through the scope of the county. This means that regional water shortage, poor land quality and other practical factors restricting social and economic development still exist. The development of the resettlement area largely depends on the allocation of resources by the higher government. On one hand, continuous investment from higher-level governments is needed to support and maintain the operation of existing production spaces, such as long-term subsidies for immigrants’ livelihood income, construction and maintenance of artificial ecosystems. On the other hand, local governments, acting in self-interest, tend to invest limited resources and energy in projects with high performance returns and easy achievement, resulting in a mismatch between supply preferences and actual demands.

First of all, under the current poverty alleviation system, poverty alleviation efforts are characterized by clear goals and the features of being staged. The Party and the government primarily rely on extraordinary administrative means to allocate poverty alleviation resources to impoverished areas from a top-down approach. For instance, each impoverished village has a designated support unit to carry out targeted assistance; county-level officials are appointed as the leaders of village working teams responsible for poverty alleviation work. After achieving the poverty alleviation goal in 2020, according to the “2021 Central Document No. 1”, regions that have emerged from poverty enjoy a five-year transition period starting from the date of their poverty alleviation. During this period, it can still be ensured that support from higher-level poverty alleviation policies and special funds remains uninterrupted. Therefore, the Agdala resettlement site can still receive poverty alleviation funding support in the form of annual project applications. However, once the transition period ends, it signifies the completion of the poverty alleviation task and the shift in strategic focus, resulting in the withdrawal of the corresponding village working teams from the poverty-stricken villages and the potential weakening of poverty alleviation efforts in terms of finance and preferential policies in the future. For remote and underdeveloped areas, creating long-term stable employment opportunities and nurturing mature local characteristic industries remains challenging in the short term.

Moreover, the issue of resource supply stability is also reflected in the micro-level assistance measures. From the example of local animal husbandry development, migrants are resettled in standardized apartment buildings and sheds are constructed. The use of pasture has changed from complete reliance on natural grasslands to partial dependence on surrounding farmland. The government constructed controlled water storage projects to support artificial grasslands, encouraging herders to adopt a small-scale grazing model of “indoor feeding in cold seasons and rotational grazing in warm seasons”. However, under the settlement model, per capita distributable resources are limited, and most relocated households’ forage production is insufficient to meet livestock feed demands during winter and spring, chronically dependent on government subsidies to compensate for the costs of supplementary feed market purchases. According to the “Qinghe County Financial Special Poverty Alleviation Fund Management Measures”, during the five-year transition period, poor households that develop their own breeding industry can receive government subsidies equivalent to 30–50% of the market price and apply for discount loans; for those who voluntarily join the breeding cooperatives, the government subsidizes 50–70% of the market price. This interim subsidy policy has stabilized the animal husbandry incomes of poor families in the short term, but it still cannot completely solve the problem of high feeding costs under the settlement model. As one interviewee said, “Even with the current government subsidies, our income barely covers the breeding costs. After settling down, we can only keep a small number of animals, so this single income source isn’t enough for basic needs. If these subsidies stop in a few years, we’ll have to find other ways to make a living” (N44, 20250322). In addition, since the resettlement sites are in arid areas, both grazing and the construction of artificial forage land depend on the development and utilization of restrictive water resources. The government had built water conservancy and irrigation facilities to maintain artificial grasslands, farmland, groundwater and other artificial agro-ecosystems. At the watershed scale, these measures still cannot change the reality of water resource scarcity, which is not conducive to the sustainable development of the social–ecological system.

Secondly, grassroots governments obtain resources for poverty alleviation through project funding from higher-level departments, but these projects require grassroots governments to fulfill specified assessment targets and raise part of the matching funds. In practice, this requires grassroots cadres to take every possible measure to highlight their achievements and work results, while at the same time solving the problems of project operating costs and funding gaps through various strategies. These strategies demonstrate certain expediency, which may lead to inaccurate resource allocation. On the one hand, to complete the poverty alleviation tasks assigned by higher authorities, grassroots cadres are more inclined to invest limited resources in assessment indicators that can demonstrate achievements, such as creating a demonstration pilot or a flagship demonstration project. In some cases, village cadres even design superficial community needs to please the higher authorities, resulting in minimal actual support being provided to relocated households through poverty alleviation resources. An immigrant expressed his views on the government to us: “You’ve probably noticed the new viewing platform and walking trails in our community—built for leadership inspections, using lots of poverty relief funds. But what use are these fancy but useless things to us migrants? They should’ve just given us cash directly” (N38, 20250322).

On the other hand, according to the National Poverty Alleviation Fund Management Measures, local supporting funds should account for 30% to 50% of the total amount of national earmarked poverty alleviation funds. Considering the weaker economic development levels and fiscal conditions in some remote areas, the proportion of local supporting funds in Xinjiang is required to reach 30% to 40%. However, based on the annual fiscal revenue, public budget revenue and expenditure situation of Qinghe County over the years (Table 3), the significant funding gap and fiscal shortfall make it very difficult to meet the demand for local matching funds. Especially in the early stage of the construction of Agdala, when Qinghe County’s fiscal self-sufficiency rate was less than 7%, half of its annual fiscal revenue was devoted to water conservancy projects in the resettlement area for three consecutive years. Under such circumstances, it became extremely difficult for the county to allocate additional funds for complementary support to development-oriented assistance projects. Therefore, local governments tend to have their own allocation preferences in project support: (i) they are more inclined to select support recipients who are able to bear a certain amount of project matching funds to implement the projects; (ii) in order to obtain more poverty alleviation resources from higher-level authorities, the projects they apply for are required to have a certain scale. Consequently, impoverished households lacking such funds struggle to obtain support. In well drilling project, the strict project fund management mechanism means that the state’s special poverty alleviation funds only cover the expenses of drilling wells. However, well drilling is a systematic project, which also involves a series of supporting investments such as land occupation for well drilling, the construction of pressure pipelines and the purchase of pumps and water pipes. The initial construction is only the beginning; subsequent operation, management and maintenance also require financial input. In order to ensure the implementation of the project, the local government ultimately reached an agreement with village cadres, whereby village cadres personally invested to provide matching funds. As a result, the wells that are nominally for poverty alleviation are, in fact, appropriated, managed and operated by the investors. A similar situation was observed in agricultural support programs. Currently, the 24,030 mu (approximately 3954 acres) of land in the resettlement sites, in addition to being used as artificial forage land, is coordinated by the government and leased to large agricultural households or enterprises at the low price of CNY 345/mu (≈CNY 2091/acre). These highly mechanized enterprises have limited capacity to create employment opportunities. After becoming the main targets of poverty alleviation projects, they capture most of the benefits and resources from these projects, while the relocated residents can only gain a meager income from land rent.

Table 3.

Summary of fiscal revenue support in Qinghe County from 2018 to 2023.

In summary, during the transition period of relocation, the expansion of production space mainly relies on the input of external resources, while the community itself lacks the ability of endogenous development. Without resource support, the problem of falling back into poverty can easily recur. At the same time, since the decision-making power of project selection is in the hands of more wealthy groups, poor households lack representatives with the right to speak corresponding to their status, so it is difficult for them to effectively supervise the implementation of supportive policies. The inaccuracy of resource allocation actually reflects the unfairness of the distribution process. Poverty alleviation resources are subject to “elite capture” by elites and external enterprises, which conceals the real needs of truly disadvantaged groups and further increases the risk of returning to poverty.

4.2. Improvement in Residential Living Space Is Constrained by Household Income–Expenditure Imbalance

The improvement in residential living spaces contains two dimensions: material and social. The material dimension mainly refers to the enhancement of living environments in resettlement areas, including the construction of basic supporting facilities and public service facilities; the social dimension mainly refers to the transition from traditional self-sufficient lifestyles to modern ways of living and behavioral habits. From a material standpoint, the government has invested a total of CNY 622 million in building the main resettlement zone and its infrastructure. This includes 37 residential buildings with 1040 housing units, 38 km of township roads and 12 km of greenbelts. Various supporting facilities such as kindergartens, medical centers, police stations, gas stations, bus terminals, agricultural markets, sewage treatment plants and landfill sites have been provided. Families in the resettlement area now enjoy regular supplies of electricity, natural gas and heating. Their access to transportation, education and healthcare has greatly improved. At the same time, the arrival of property management companies and the creation of public cleaning roles have greatly improved the cleanliness of the community. New types of businesses, such as delivery points, mobile phone stores, driving schools, cooperatives and renovation shops, have not only diversified local commerce but also made daily necessities more accessible. From the perspective of social factors, the shift from a traditional self-sufficient lifestyle to a modern way of living and behavioral habits is mainly reflected in the modernization of transportation and communication, housing, production and consumption patterns, as well as daily life habits. For example, travel has shifted from walking and animal-powered transport to modern vehicles such as motorcycles, cars, and buses, while communication is marked by the widespread use of the Internet. Housing has evolved from a nomadic, unsettled lifestyle to permanent residence in standardized homes. Production and consumption have moved from self-sufficiency to market-based purchasing, and daily life habits are characterized by the widespread adoption of modern facilities such as flush toilets, natural gas provision and tap water. The interviewee stated “Compared to the past, the current housing conditions are much better. Young people now find it easier to seek marriage partners and are also more willing to stay and develop in the local area” (N30, 20250323).

However, the improvement in residential living space at both material and social levels is still constrained by the income–expenditure situation of relocated households. Based on the data of 134 relocated families provided by village cadres (Table 4), we set a reference value for the income and expenditure situation: Reference Value = (Total Income − (Crop Production Expenditure + Livestock Expenditure + Living Expenditure + Medical Education Expenditure))/Number of Resident Household Members. The results show that, after excluding each family’s major expenditures, the minimum per capita net income is CNY 983, the average is CNY 4281.93 and the maximum is CNY 30,970. This indicates that there are significant differences in income and expenditure among relocated herders. Moreover, considering other miscellaneous expenses in daily life such as loans, weddings and childbirths, many immigrants may experience situations where expenditures exceed income. During our interviews, we found that immigrant households with smaller family sizes, aside from their basic living expenses, experience varying degrees of loan pressure. Although the PAR policy requires housing allocation and construction based on 25 square meters per person, in practice, due to the need for unified construction scale, immigrant households with smaller family numbers have to choose housing exceeding the per capita allocation standard, bearing higher housing costs through loans. Meanwhile, from the survey of the main sources of income for immigrant families (Table 4), property income accounts for 34.5% of total income, mainly derived from the income generated by the subcontract of government-allocated land. According to the policy of allocating 10 mu of land per person, the fewer the family members, the lower the property income and the poorer the income stability.

Table 4.

Family income source situation.

In resettlement areas, newly established industries are still in the trial-and-error phase of early production. Because of this, their ability to absorb labor remains weak, leading to limited stable employment opportunities for migrants and few income channels, with a strong reliance on land lease income. At the same time, large-scale relocations driven by the government have caused sudden population increases, creating a large pool of idle labor that disrupts the local labor market balance. Although the government has implemented employment support programs, there are few job seekers who meet the required age, education and skill standards. Only a small number manage to find local jobs, leaving many middle-aged and elderly residents unemployed for long periods. As interviewee N07 stated, “Most youngsters are out hired herding or doing migrant work, only coming back in winter. What’s left in the resettlement area are basically the elderly, the sick and school-age kids. Compared to our old self-sufficient life, elders here now totally depend on their children’s support. No income, no job opportunities. Some old folks cut corners everywhere—sitting in darkness to save electricity, skipping toilet flushes to save water, skimping on food and clothes. Truth be told, their living standards haven’t improved much” (N07, 20240506).

Meanwhile, immigrants have experienced varying degrees of capital depreciation and increased living costs due to relocation. Initially, the governments compensate relocated families based on the value of their original properties. However, this compensation often falls short of covering all relocation expenses. Families must cover additional costs such as building new homes, decorating interiors and purchasing essential goods, leading to significantly higher living expenses early on. Moreover, the transition to urban living renders some rural tools and practices obsolete, increasing household depreciation. One interviewee noted “We sold livestock during relocation when prices were low, incurring losses due to urgent financial needs” (Interviewee N11, 20240717). Currently, these families have abandoned self-sufficiency, relying fully on the market for basic needs. From utilities like water, electricity and internet to property maintenance, everything requires money, causing sharp increases in daily costs. Another interviewee remarked: “On the grasslands, we produced our own food and used dung for fuel. Now, mutton costs CNY 80 per kg, and utilities like water, electricity, and heating require payment” (Interviewee N12, 20240718). With incomes not keeping pace with rising expenses, households face growing financial strain, especially those burdened with higher housing costs.

4.3. Social Spaces Exhibit Expansion of Weak Ties and Contraction of Strong Ties

There are usually relationships of varying strengths in a social interaction space; these different types of relationships also play different roles in helping migrants obtain labor support, material support, emotional support and economic support. Examining the development trends of different types of relationships could help us understand migrants’ ability to access social support and resist social risks in the community. Drawing on Granovetter’s study on “the strength of ties”, we typologically divided the existing social relationships of migrants into strong ties and weak ties. Granovetter’s proposed third kind of relationship, “absent tie” (referring to those who are complete strangers or people one merely knows but lacks substantive contact with), is not the focus of our analysis and is therefore not discussed. According to the predetermined measurement dimensions, with reference to aspects such as the content of information exchange, mutual aid activities in production and daily life and total interaction duration, we asked the respondents to determine which people in the community have good, average or no relationship with them. Through discussions with migrants, we found that they have clear distinctions regarding the characteristics of strong ties and weak ties (Table 5). These characteristics are specifically reflected in the following: weak ties have a broad scope of coverage and may involve migrants from different villages. Migrants generally greet each other politely when they meet, and the frequency of contact varies depending on the opportunities for encounter, but such encounters all lack regular and in-depth communication. The dissemination of information and mutual aid activities mainly occur in certain domains, such as through workplace interactions. This type of relationship may provide extra social mobility opportunities and transmission of job information, but there is less dissemination of information and mutual aid activities in the field of daily life. In contrast, strong ties mainly originate from kinship ties and geographical ties established before relocation and retained after relocation. They are significantly different from weak ties in terms of interaction frequency, interaction duration and the exclusivity of certain information dissemination and resource sharing. For example, according to the survey responses, within 15 days, the highest frequency of in-depth communication (one-to-one interaction time exceeding 30 min) with strong ties can reach up to five times, with a minimum of at least one or two times. It is worth noting that certain shared information has exclusive characteristics, such as private life details, plans for production, valuable work information or technical sharing, as well as disparaging gossip about others. In addition, there are more frequent material exchanges and mutual aid activities among migrants with strong ties, involving ceremonies such as weddings, births, funerals and communal affairs of the original village; these interactions have deeper emotional connections.

Table 5.

Differences in resources carried by strong ties and weak ties.

From the perspective of the impact of PAR on changes in migrants’ social relationships, on the one hand, under the construction model of multi-village merging, relocated groups from different administrative villages are reorganized into concentrated residential communities. The scale of heterogeneous population settlement has significantly increased, the residential radius has expanded outward and the space for social interaction has extended beyond the boundaries of the original administrative villages. The increased opportunities for interaction between different groups have led to the continuous expansion of weak ties within social interaction spaces. On the other hand, the government deliberately arranged for villagers from the same administrative village to resettle in the same building or in adjacent areas as much as possible. This form of collective or joint resettlement allows them to maintain their original social relationships, interaction patterns and relational structures. The relationship networks preserved during the relocation process are mainly composed of strong ties. However, as some social relationships in the original resettlement areas were damaged during the RAP process, this has resulted in a partial loss of social capital among migrants. Former friends and relatives from the original villages may become estranged due to increased social distance and the higher social costs caused by spatial separation. Compared with the pre-relocation period, strong ties in social interaction spaces exhibit a contracting trend.

Changes in different types of relationships within the social interaction space have a significant impact on individuals’ or families’ access to social support. However, in reality, the expansion of social networks does not necessarily improve the quality of interactions. In these newly constructed weak ties, the social connections between residents are superficial. The role of these relationships in providing social support is largely confined to specific domains; they offer relatively little information and mutual assistance in the sphere of daily life. In addition, the survey found that an unintended consequence of the PAR initiative was the spatial concentration and clustering of the poor social class. A village official stated, “Poverty alleviation relocation is implemented through whole-village advancement. Households with relatively better conditions in the original village chose self-resettlement instead of relocating here. Most of them turned to join relatives who were in better economic situations in other cities to seek better development opportunities” (N08, 20240515). This unintended consequence directly led to a further weakening of the social support that could be provided by the already narrowed strong-tie networks of the migrants. Among the poor households, those with a relatively better economic foundation and richer social capital tended to choose independent relocation, while those identified as poor who voluntarily settled in the Agdala resettlement area were mostly highly homogeneous and economically disadvantaged. As described by the migrants themselves, they are struggling just to get by. Therefore, the social support that can be mutually provided by these preserved strong ties is negligible due to the lack of social capital. These migrants have a low sense of self-identity, limited resources to invest in new social relationships and are at disadvantage in social exchanges with other groups. When the social environment changes, as social distance and the costs of social interaction increase, they find it difficult to maintain strong ties outside the PAR community and also have little additional time or energy to build and sustain new social relationships. To a certain extent, the lowering of social interaction expectations is not conducive to the transformation of weak ties into strong ties within the social interaction space, thus limiting their access to social support and their capacity for risk mitigation. As respondent N15 said, “We don’t have much contact with community officials. When we face problems, we still turn first to the former village chief and our relatives. Most of those we exchange monetary gifts with are still our old friends. Of course, we sometimes have a chat with new neighbors, but we never get too close” (N45, 20250323).

4.4. Organizational Space Operation Faces Pressure from Heavy Governance Costs and Population Management Challenges

A poverty relocation community differs from a traditional rural or urban settlement. It emerges through the administrative consolidation of multiple natural villages and exhibits the transitional characteristics of “administrative dominance” alongside “semi-urban and semi-rural” attributes. Consequently, such a community is confronted with administrative affairs and governance challenges whose scale and complexity far surpass those encountered in a traditional community. On the one hand, there is a strong demand among relocated populations to restore livelihoods. Therefore, community governance affairs rely heavily on a government safety-net model, which leads to heavy governance costs. On the other hand, factors such as the vagueness, inconsistencies and delays in the adjustment of property rights attribution, the contradiction between hukou system and territorial governance, the enhanced mobility constitute structural forces that undermine the effectiveness of community governance, posing challenges for grassroots organizations in population management.

Firstly, the governance tasks for grassroots organizations in relocation communities are not limited to handling resettlement issues such as land swap compensations, workforce relocation arrangements and migrant welfare program transitions. They are also required to handle various new public duties assigned by the subdistrict office to which they belong, including repairing communal building areas, maintaining environmental sanitation and landscaping, managing special maintenance funds and collecting municipal service fees. Community official N05 disclosed operational challenges during our interview: “Our community’s property fees are set at rock-bottom rates to begin with. Keeping basic services running is already a stretch, but we’ve still got tons of residents giving us the payment cold shoulder. Honestly, it’s like pushing a boulder uphill every single day“ (N05, 20240512). From a practical perspective, their past rural housing habits have not yet transitioned, making it difficult for them to accept market-oriented property management services in the short term. At the same time, low-income households themselves have weak payment capacities, and the original village collective economies have limited subsidization capabilities. In this context, government emerges as the de facto guarantor of community governance stability. For detailed information, please refer to Table 6.

Table 6.

Basic information on government subsidies and welfare policies.

At present, the government’s safety net measures demonstrate notable short-term effectiveness, fully leveraging the strengths of socialism with Chinese characteristics. However, this creates hidden risks for the regularized governance of community management institutions, resulting in prohibitively high costs to maintain normal organizational operations. As interviewee N05 stated, “While the original intention of mobilizing administrative resources to address issues was good, over time it has cultivated a ‘wait, rely, demand’ mentality among relocated residents. The relocation work’s done, but we’re still stuck dealing with tons of small yet tricky jobs every day. See, folks now automatically come to us for everything—like we’re the fixers for all life’s problems (N05, 20240512). There is a widespread belief that they were relocated here for the government, thus the government bears comprehensive responsibility for their future livelihoods. It is true that during the initial relocation mobilization phase, some officials over-promised and embellished post-relocation living conditions to expedite the signing process. Field observations reveal that community spatial layouts are saturated with poverty-alleviation informational elements, with every promotional display area featuring slogans expressing gratitude to the nation and comparative photographs of old and new living conditions. For residents, their disadvantaged identity labels as “impoverished households” and “relocated migrants” are continuously reconstructed and reinforced. Under such perceptions, the residual “dependency mentality” among impoverished groups remains difficult to eliminate, while civic consciousness and self-governance capabilities prove challenging to cultivate, substantially increasing the operational burdens on grassroots governance organizations.

Secondly, the challenges in population management primarily stem from confusion in property rights attribution in the origin areas, the contradiction between the territorial management system and the household registration system and the increasing mobility of the population. Through the interviews, we found that the institutional arrangements that determine the property rights ownership of migrants’ original homesteads, pasturelands and agricultural lands in the origin areas are not consistent across different townships. The delays, inconsistencies and vagueness in property rights attribution inevitably fuel grievances among migrants, obstructing their complete disengagement from the origin areas and full integration into the destination communities. Some migrants moved to new communities, but their former land was not reclaimed by the government, and they even maintain dual residences. Furthermore, the contradiction between the territorial management system and the household registration system has led to the widespread phenomenon of “two-headed management”. Although migrants have moved to the resettlement area, specific matters such as insurance payments and processing educational certification documents for children still require returning to their registered households’ location. Typically, a multi-village merged resettlement community continues to have its residents’ affairs managed by their respective village committees after relocation. However, the phenomenon of secondary migration is widespread after PAR. With the increasing mobility of the population, the traditional grassroots governance approach of village cadres conducting door-to-door visits and informal communication has become unsustainable. A significant portion of the population in resettlement communities is highly mobile herders and migrant workers. They may retain household registrations in their original domiciles or establish household registrations in resettlement communities, while actually residing year round in other regions. Therefore, the management of a relocation population frequently exhibits spatial disjuncture between household registration locations, policy implementation areas and actual dwellings.

An interviewee described this situation as follows: “Many of these resettlement houses are mostly empty. Grandparents stay behind to look after children while herders move between pastures. During summer breaks, the whole family goes back to the grasslands and lives in tents. They only come back when it snows or school starts. The constant moving around makes it hard for officials to keep track of everyone” (N19, 20240908).

5. Discussion

Based on qualitative research conducted at the Agdala Relocation Resettlement Site, this study draws on the livelihood space framework to systematically examine the impact of PAR on livelihood sustainability and the risks of returning to poverty in the post-poverty era from four dimensions: production, residential, social interaction and organization.

The results of the study show that although relocation has improved the geographical conditions for policy-targeted groups, it neglects the governance of multidimensional relative poverty, and multidimensional livelihood spaces—encompassing production, residential, social interaction and organization—remain vulnerable to poverty relapse risks. PAR, while reconstructing productive spaces, has intensified relocated households’ heightened dependence on external poverty-alleviation resources. As policy priorities evolve, sustainability challenges in external resource supply will gradually emerge. Similar to our findings, a classification study on the sustainability levels of rural households’ livelihoods indicated that rural households with low livelihood sustainability tend to rely more heavily on government grants and subsidies. When government support ends, these households face increased risks [39]. To address this issue, another study on the link policy regarding relocation points out that some areas can obtain funds and resources by selling construction land indicators to developed regions. This helps solve the lack of funds for the later development of resettlement areas. However, most remote areas like Agdala find it hard to obtain such opportunities. This is because their land reclamation is low and the reclamation cost is high [40]. Differing from our study, another study analyzed the sustainability of poverty alleviation villages in obtaining support funds and project resources by examining the tenure and retention willingness of resident secretaries, thereby illustrating from another perspective the impact of the external political environment and policies on the sustainability of poverty alleviation outcomes [41]. Our study also found that, due to the requirements of performance appraisals and the shortage of local matching funds, local governments often adopt various strategies in the allocation of poverty alleviation resources, leading to a misalignment between administrative preferences and the actual needs of migrants. Differently from this study, another study attributes the main cause of this phenomenon to political connections. The research argues that relationships among acquaintances still play an important role in the resource allocation of poverty alleviation in a relation-based society [42]. The closeness of relationships between villagers and village cadres affects their access to information about poverty alleviation policies and the distribution of resources. This provides another perspective for explaining our research findings. Another study attributes the crux of this issue to corporate actors; it posits that some enterprises participate in poverty governance based on the logic of profit maximization. As a result of this utilitarian mentality, it is difficult for enterprises to effectively fulfill the pro-poor governance role of allocated resources after obtaining government poverty alleviation funds [43].

The prevailing view holds that community construction can effectively improve the living standards of migrants. However, relevant research and field investigations have found that this perspective does not apply to all poverty alleviation households and communities. The improvement of the community’s material foundation and the shift towards a modern lifestyle signify a constant rise in the cost of living. For impoverished groups lacking basic living security, improvements in quality of life must first be built on a foundation of affordable economic burdens. The rising cost of living imposes a substantial burden on specific vulnerable groups, particularly the elderly. Due to age-related limitations and health challenges, the elderly encounter difficulties in partaking in non-agricultural employment. Consequently, they are unable to cover expenses such as water bills, electricity charges, property taxes and other costs that surpass their limited financial capacity [44]. Another study’s survey results show that 16.33% of farmers are indebted over CNY 10,000 due to resettlement. Although PAR bears the majority of the relocation burden for the resettled individuals, most of them still face significant debt repayment pressure, which in turn affects the improvement of their quality of life after relocation [45].

This study also found that the structure of social relationships within a resettlement community presents the characteristics of a “Society of Semi-Acquaintance” under multi-village centralized resettlement [46]. On the one hand, opportunities for social interactions among migrants from different administrative villages have increased, resulting in the expansion of weak-tie networks; on the other hand, PAR has damaged some strong-tie networks due to increased social distance and rising interaction costs. From the perspective of the impact of different social relationships, the expansion of weak ties does not necessarily lead to an improvement in social quality, as the social support they can provide is limited. In addition, an unintended consequence of PAR has been the spatial concentration and clustering of impoverished groups. Impoverished households relocated to Agdala settlement through village mergers mostly have weak economic foundations, further undermining the social support offered by strong-tie networks. Whether this trend will change in the future remains uncertain. Unlike our study, a study specifically addressing changes in family social relationships among migrants found that relocation results in a decrease in multigenerational households [47], suggesting that the supportive role of intergenerational relationships in livelihood sustainability may be affected. Another study indicated that different relocation patterns affect the supporting role of social relationships. It analyzed four relocation patterns: centralized, adjacent, enclave and infill, and noted that the enclave type should be considered a last resort, as this type consistently has negative impacts on both maintaining existing social relationships and building new ones [29].

Finally, our research shows that the completion of resettlement initiatives means that community living systems transition toward urbanization. This transition poses severe challenges to grassroots organizations in resettlement communities. The high governance costs generated by heavy community governance tasks exceed the resource capacities of this grassroots organization. In addition, the delays, inconsistencies and vagueness in property rights attribution, as well as the contradiction between hukou system and territorial governance, have increased the difficulty in population management for grassroots agencies. At the same time, such challenges are further compounded by intensified mobility. These problems may undermine state-established mechanisms for preventing poverty recurrence, such as dynamically monitoring the lifted-out-of-poverty population, implementing follow-up policies and establishing sustainable livelihoods.

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, it is a study based on a typical case from a specific region, which provides a valuable entry point for understanding the risks of returning to poverty in the post-poverty alleviation era. However, due to differences in natural geography, ethnic composition and levels of social development across regions, it may not reflect the overall impact of Poverty Alleviation Relocation (PAR) in China or other countries. For instance, in resettlement areas with higher levels of urbanization or richer natural resources, the causes behind similar issues may differ. Therefore, it is necessary to consider local conditions and avoid one-size-fits-all approaches when addressing specific problems. Nevertheless, the livelihood–space framework remains highly applicable and holds strong value for broader adoption as both an analytical approach and practical tool for informing poverty reduction strategies across different regions. Second, as this study relied on the perspectives of interviewees, some government officials may have shown bias or withheld certain facts—particularly by overstating the successes of relocation programs and underestimating the challenges currently faced by relocated households. To address this, we used cross-verification and triangulated data from multiple stakeholders. We also excluded some materials to reduce potential bias and sought to strengthen the evidence base with objective data wherever possible. Finally, the relationship between livelihoods and space is diverse and complex. Future research should further expand to include multiple case studies or adopt quantitative methods to support broader comparative analysis. It is also necessary to refine the conceptual framework and develop more detailed measurement indicators, in order to build a more comprehensive system for evaluating livelihood space.

6. Conclusions