1. Introduction

Geographical indications (GIs) are powerful tools in protecting and promoting agri-food products whose qualities are closely tied to their place of origin. Within the European Union, the GI system is structured around two main labels: Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and Protected Geographical Indication (PGI). These designations not only ensure product authenticity and traceability but also contribute to broader goals such as rural development, cultural heritage preservation, environmental sustainability, and community empowerment [

1,

2]. Origin-linked products benefit from unique attributes shaped by local ecosystems, traditional knowledge, and long-standing production methods, enabling them to occupy differentiated positions in increasingly globalized and competitive food markets [

2].

However, certification alone is not sufficient to guarantee market visibility or consumer engagement. In the digital economy, communication and branding strategies have become crucial for producers to reach broader audiences, convey product value, and compete effectively. The literature points to the growing adoption of websites and social media among some agri-food cooperatives [

3,

4,

5], but it also highlights important gaps in digital capacity, particularly among smaller producer groups, which often lack structured marketing strategies and digital literacy [

6]. Furthermore, while the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the digital transformation across the agri-food sector [

7], many GI producers still face challenges in maintaining consistent and meaningful online engagement.

Among the various digital platforms, social media—especially Facebook—has emerged as an accessible, low-cost tool for small and medium-sized agricultural producers to promote their products and connect with consumers [

8,

9]. Despite the growing relevance of platforms such as Instagram and TikTok [

10], Facebook remains the most widely used social channel among GI agricultural producer groups in Southern Europe, offering a relevant context to analyze how values such as sustainability, quality, and tradition are communicated—or overlooked—in the digital sphere.

This study investigates the intersection between sustainability and digitalization in the promotion of PDO and PGI agricultural products, focusing on five Southern European countries: Italy, Spain, France, Portugal, and Greece. Findings indicate that, while digital presence is increasing, the promotion of sustainability remains largely absent, and structured, long-term marketing strategies are still lacking. Despite the inherent association of GI-certified products with sustainability, cultural heritage, and community identity, these values are rarely reflected in their digital communication. This reveals a critical gap: while GI products have strong narratives rooted in their territory and sustainability, producer groups are failing to translate these attributes into coherent and consistent digital strategies—particularly on social media. As a result, there is a disconnect between the potential of GIs to promote sustainable development and the way that they are currently presented in the digital landscape. Moreover, although fruit and vegetables is the product category with the most PDO and PGI registrations, this category is less studied in the literature [

11].

Based on a dual analysis of the overall digital presence and Facebook content, this research aims to critically assess the current landscape of digital communication practices among GI producer groups of agricultural products in Southern European countries (Italy, Spain, France, Greece, and Portugal). By providing an evidence-based snapshot of how these products are marketed online, this article seeks to contribute to ongoing efforts to strengthen the authenticity, quality, and territorial identity of GI-certified products through more strategic and aligned digital promotion. Moreover, this study seeks to evaluate how GI products are currently being promoted on Facebook by analyzing the content of posts and the language used in their dissemination, with the aim of identifying whether and how attributes such as sustainability, cultural heritage, and community identity—which are fundamental to GI-certified products—are most frequently highlighted in digital communication.

3. Research Methodology

This study examines the digital promotion of GI-certified agricultural products, focusing on the extent to which their sustainability and origin-based values are reflected in online communication. The products that are part of the investigation are registered as PDO or PGI under the EU basis of protection, belonging to the Food category—Class 1.6 (fruits, vegetables, and cereals fresh or processed) (

Figure 1). The countries selected for this evaluation are Italy, Spain, France, Greece, and Portugal. In addition to sharing cultural and agricultural similarities, rooted in the Mediterranean context, these five countries collectively account for approximately 75% of all GI-certified agricultural products in Europe [

1]. Notably, they also represent the top five countries in terms of the number of GI registrations specifically within the agricultural product category, further justifying their selection for this study [

1,

45]. Furthermore, they lead in the overall number of GI registrations across all categories and show the highest growth in recent registration requests within the European GI scheme [

45].

Desk research was used as a preliminary step to explore existing information related to the digital presence of PDO and PGI agricultural products in Southern Europe. This method involves the systematic collection and analysis of secondary data, including publicly accessible online sources, official databases, reports, and previous research. It also includes the reinterpretation of existing data sets—in this case, with the aim of generating new insights into the current digital communication practices of GI-certified producer groups [

46].

3.1. Data Sources

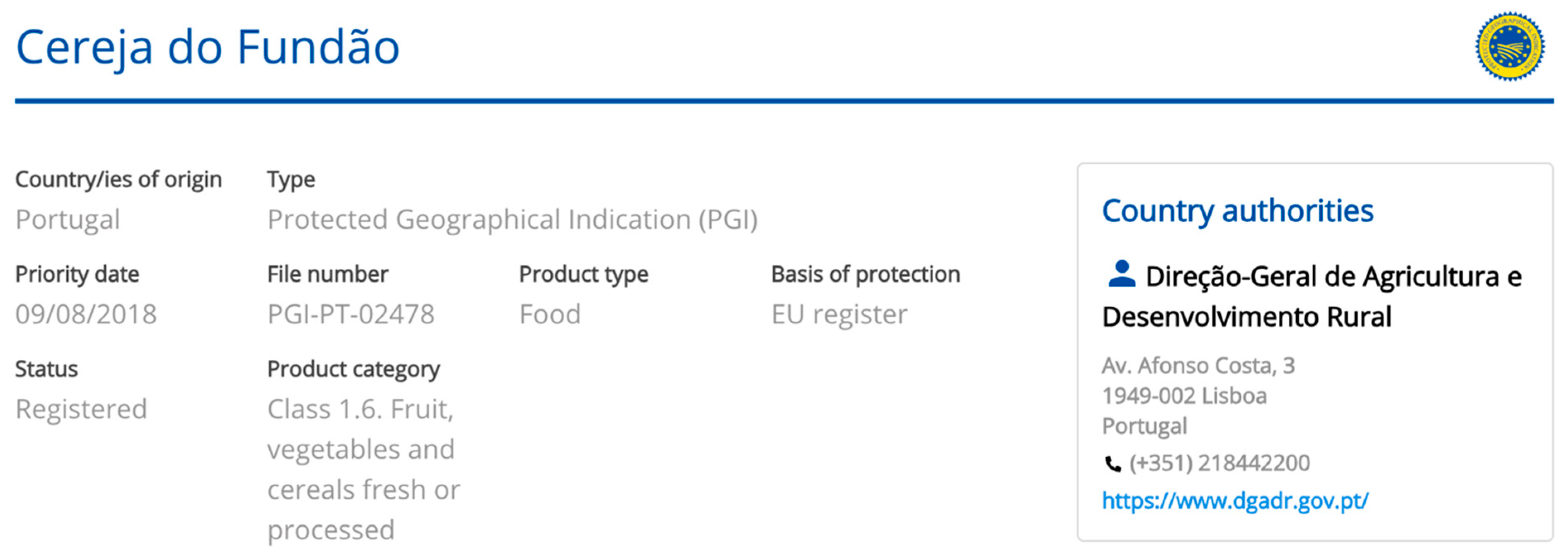

The primary data source used in this study is the GI View portal, the official GI database managed by the European Union Intellectual Property Office. This public EU database presents all detailed information for each product registered under the GI scheme under the EU basis of protection. Among these data are the official name of the product, its country of origin, and the name of the producer group responsible for the GI. Desk research was conducted where every product was assessed according to (1) the existence of the producer group name on the GI View portal, (2) its presence on digital platforms (websites, blogs, social media channels, and e-commerce), and (3) the name used in promoting the platform (product name vs. producer group name). By “product name”, we consider the usage of the name of the product as registered (for example, Cereja do Fundão—Fundão Cherry), while “producer group name” refers to the producer association or cooperative that is responsible for the GI product (

Figure 2).

3.2. GI Agricultural Products—Overall Digital Presence

To evaluate the presence on digital platforms, this study first considered the producer group data available on the GI View portal. When this information was not available on the GI View website page, additional research was conducted through the publications of the Official Journal of the European Union, available in PDF format. Furthermore, the producer group names and the official product names were subjected to additional desk research on Google or other related websites, aimed at gathering more information about the existence of an active association of producers (

Supplementary Table S1).

A quantitative analysis was employed to calculate the proportion of products with a digital presence and to classify this presence according to the platform and naming strategy. The data were grouped by country to allow comparative interpretation. An additional qualitative analysis was conducted on the existing digital platforms to evaluate the names used in promoting the platform (product name vs. producer group name).

To address the research hypotheses and explore patterns in digital engagement and platform usage among GI producer groups, a combination of descriptive and inferential statistical methods was applied. Descriptive statistics, including frequency counts and percentages, were used to characterize the sample and to evaluate the distribution of digital presence across different countries and channels. To test the formulated hypotheses (H1–H4), bivariate correlation analyses (Spearman’s rho) and independent-samples t-tests were employed, along with a one-way ANOVA and a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test to identify significant differences between groups. Additionally, boxplots and heatmaps were generated to support the interpretation of group differences and data distributions.

3.3. GI Agricultural Products—Facebook

At this stage, we considered only the producer group with a Facebook Page with any type of publication from January 2023 and April 2024. The original dataset was created using a web-crawling service called Apfy, which mined publicly available posts from Facebook Pages. As these Facebook Pages were public, it was possible to openly view all Facebook data without restrictions. The scope of the data that were extracted and analyzed consisted of basic Facebook Page data, which indicated how up-to-date and complete the basic data were, and publications data, which indicated the level of engagement with consumers via the Facebook Page. Additionally, they revealed the types of content promoted by the producer group. A mixed-methods approach was applied. In addition to quantitative indicators (post frequency, media type, engagement rate), a qualitative content analysis of Facebook posts was conducted using Voyant Tools, a web-based textual analysis environment.

The quantitative analysis was conducted with the Facebook Page’s basic data and publications data. The Facebook Page’s basic data consisted of the page creation date, “About” section, address, phone, email, and external links to the website and other social media platforms. The publications data consisted of the total number of publications per Facebook Page, frequency of publications, media type, number of interactions (likes, shares, and comments), and posts’ text content. Additionally, the qualitative analysis was conducted using the texts of each publication. After extraction, the data were translated to English and analyzed on a web-based text reading and analysis environment called Voyant Tools. Within these tools, the content of each publication was analyzed and the results grouped per country in order to understand how the producer’s association used Facebook. For this study, the Voyant Tools used were cirrus (a word cloud that visualizes the highest-frequency words of a corpus or document), count (the frequency of a term in the corpus), relative (the relative frequency of a term in the corpus, calculated by dividing the raw frequency by the total number of terms in the corpus and multiplying it by 1 million), and correlations (a tool that enables an exploration of the extent to which the term frequencies vary).

This study was carried out on those products for which a producer group was available on the GI View portal (n = 314) and/or those that had a digital presence through a Facebook Page (n = 219). It is important to note that some groups of producers handle more than one product, and they were evaluated as unique Facebook Pages. The final sample of the study—see

Table 1—considered only unique Facebook Pages with any type of publication from January 2023 and May 2024 (n = 168). This limitation was due to the immediate consumption nature of social media and the fact that a lack of information sharing with customers may reduce customers’ trust.

4. Results

The evaluation of agricultural products registered under the EU’s PDO and PGI schemes provides crucial insights into the promotion of these products on digital platforms. The analysis focused on Southern European countries—Italy, Spain, France, Greece, and Portugal—which that collectively account for 75% of all agricultural products under GI schemes in Europe (n = 335). Italy leads, with a total of 125 products, followed by Spain (67), France (62), Greece (48), and Portugal (33).

The desk research showed that the information about producer groups on the on GI View portal is not accurate. Among the five countries evaluated, Portugal stands out due to including 85% (n = 28) of its registered agricultural products with updated information on the portal. Producer group information is not available for any of the products registered by Italy, Spain, or France, requiring the further analysis of PDF files and web searches to find the missing information. In total, the producer groups responsible for 21 products could not be found, with most of these under Greek registration, where 19% (n = 9) of the products were available without the producer group’s name.

4.1. GI Agricultural Products—Overall Digital Presence and Platform Usage

The study of the digital presence of PDO and PGI products was carried out on those products for which a producer group was available (n = 314), and it revealed a varied landscape of online promotion in the selected countries. In total, 16% (n = 49) of the products evaluated do not have any kind of digital presence. Greek products are the ones with the weakest digital presence, representing 64% of their products, and Spain is the country with the best online presence, representing 92% of its products (

Table 2). Digital presence was defined as the use of at least one of the following channels: a website, Facebook, Instagram, e-commerce, LinkedIn, Pinterest, TikTok, Twitter, or YouTube.

The producer groups with some digital presence (n = 265) were also evaluated across various social media and digital platforms, including websites, e-commerce platforms, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Pinterest, TikTok, Twitter, and YouTube (

Table 3). From this sample, 27% had a digital presence on at least one platform, and only 10% had a digital presence on more than five channels. All countries showed a strong presence on websites, with France achieving a 100% rate, indicating that official or dedicated websites are the primary digital tool for the promotion of GI products. Portugal presented the lowest usage of websites; however, it showed the highest rate regarding Facebook usage (87%), along with France and Spain. It is important to mention that 30 GI products are only represented on Facebook. In general, the use of social media platforms varies significantly between countries and platforms. For instance, Spain showed the highest rates for the usage of Twitter (51%) and YouTube (26%), while Tik Tok only represented 1% of the sample’s digital presence, being used only for producers in France and Spain. The use of e-commerce was also relatively low, with France and Greece showing the lowest (2%) and highest percentages (12%), respectively, indicating varying strategies in leveraging online sales channels for GI products. It is important to mention that the use of e-commerce in Greece is closely related to cooperatives that sell wine, as mentioned by Cristobal-Fransi et al. (2023) [

7], and they expand the distribution of agricultural products via an online store. As they satisfy the needs of agricultural producers, the intention to use social media channels for marketing and sales has increased, facilitating their adoption and use [

8]. Many companies are driven to social media marketing, especially via Facebook, as a faster and low-cost path into the digital world [

9,

47].

In general, Facebook is the social platform that is adopted to promote agricultural products, accounting for 81% of the sample’s digital presence, followed by Instagram with 49%. The finding of Facebook’s massive presence is not new, as it is the most used social platform in the world [

10]. Instagram showed higher relevance for the Spanish market, where 67% of products presented an Instagram profile; together with Portugal, Spain is the only country where the use of Instagram is higher than that of Facebook [

10]. Another aspect related to the Spanish market is the strong presence of X (Twitter), presented for 51% of the products searched, reflecting another strong relationship in the general data about Spain, where, among the five countries analyzed, it is the one with the highest usage of X (Twitter). A deeper examination of the LinkedIn data showed that Portugal exhibited the strongest usage of this platform among the countries included in this study; however, it does not show a digital presence on this channel. Greece, in general, has the weakest usage of social media channels for agricultural products; the same pattern is noted in the We Are Social and Meltwater report (2024), where Greece has the lowest percentage of social media users vs. the total population.

In order to validate H1 and to assess the extent to which producer groups across different countries use digital tools to promote PDO and PGI products, a series of statistical analyses was performed using data on the presence or absence of each digital channel (websites, Facebook, Instagram, e-commerce, LinkedIn, Pinterest, TikTok, Twitter, and YouTube). For each product, a binary variable (1 = present; 0 = absent) was created, and a total count of the channels used was computed.

First, a heatmap (

Figure 3) was generated to display the average use of each digital channel by country. This descriptive analysis helped to identify which platforms were more prevalent across the five countries analyzed (France, Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Greece). The heatmap clearly showed that, while most countries maintained a strong website presence, there was wide variability in the use of social media and e-commerce platforms. Facebook was the most frequently used channel, whereas TikTok and Pinterest showed negligible adoption.

To test for statistically significant differences between countries in the number of digital channels used, a one-way ANOVA was conducted. The results revealed a significant effect of the country on the number of digital channels (F(4, N) = 18.35, p < 0.001), indicating that not all countries adopt digital platforms to the same extent. Given the potential non-normal distribution of the data, a Kruskal–Wallis test was also conducted as a non-parametric alternative, which confirmed the significance of the differences (H = 62.67, p < 0.001).

A boxplot (

Figure 4) was produced to visualize these differences. It clearly illustrates that countries such as France and Spain tend to use a greater number of digital channels per product, while Portugal and Greece have lower median values and wider variability. These findings reinforce the need for tailored strategies that consider each country’s level of digital maturity and engagement.

4.2. Facebook Utilization and Engagement

Considering that Facebook accounts for the majority of the digital presence among GI producer groups and remains the most widely used social platform globally, this study focuses on Facebook as the primary channel to explore how sustainability and product identity are communicated online in the agri-food sector. From the 265 producer groups with a digital presence, 170 had active Facebook Pages with posts between January 2023 and April 2024.

A preliminary analysis was conducted to determine the accuracy of the description of the Facebook Page’s basic information across the various pages. The Facebook Page’s basic information is a list of non-mandatory fields that includes an “About” section, address, email, phone number, website, and alternative social media channels. The results describe the percentage of pages from each country that have each basic information field correctly populated (

Table 4).

Another important aspect is related to the average frequency of publications for each country per month and the average engagement rate (

Table 5). The average engagement rate per post by followers on Facebook is calculated as the total engagement (reactions, comments, and shares) divided by the number of posts on the page. The result is then divided by the number of followers and multiplied by 100 [

48].

In order to examine Hypotheses 2 and 3, a set of analyses was conducted to explore the correlations between the engagement rate, the posting frequency, and the naming strategy used on Facebook—whether referring to the product itself or the associated producer group.

Hypothesis H2 posited that a higher posting frequency on Facebook would be associated with increased engagement rates among GI producer groups. However, the results of the Spearman correlation analysis refuted this expectation (

Table A1), revealing a statistically significant negative correlation between the posting frequency and engagement rate (ρ = −0.20,

p = 0.011). Contrary to conventional assumptions, these findings suggest that simply increasing the number of posts does not lead to better audience interaction.

Hypothesis H3 considered whether the type of digital presence (naming after GI product vs. naming after producer group, as presented in

Table 4) affects consumer engagement. A t-test was conducted, comparing the average engagement rate between the two groups. Levene’s test confirmed the equality of variances (

p = 0.826), justifying the use of a standard independent-samples t-test. The results revealed no statistically significant difference between the two groups (t = 0.467,

p = 0.641), indicating that the form of presentation—whether as a product or an association—does not have a measurable impact on the Facebook engagement rate. The corresponding boxplot (

Figure 5) illustrates the similarity in the engagement rate distributions across both groups, reinforcing the lack of significant variation between pages named after the product and those named after the producer group.

This study also sought to identify the most prevalent types of media utilized in Facebook publications (

Table 6). The results were classified into five distinct categories of media, as outlined below.

Event: any type of publication that promotes an event created on a group of producers’ Facebook page or on a third-party page.

Link: any website link that is incorporated into the publication as a component of the content.

Photograph: any type of publication that utilizes at least one image as part of the content.

Shared: other Facebook posts published by third-party pages and shared on the group of producers’ Facebook page.

Video: any content in video format used as content on a group of producers’ Facebook Page.

Hypothesis 4 proposed that the use of videos in posts would be positively correlated with the engagement rate. However, the Spearman correlation analysis (

Table A1) revealed no statistically significant relationship between the number of videos posted and the engagement rate (ρ = −0.02,

p = 0.809).

4.3. Facebook Content Strategy

In order to give answer to the Proposition 1, a preliminary global corpus of words was constructed by analyzing the content (posts from Facebook Pages) of the five countries included in the sample. Prior to the analysis, all data were translated to English. The global corpus comprised 656,383 words, with Spain representing 45% of the types of words in the corpus (the number of unique words found in the documents), followed by France (23%), Italy (19%), Portugal (7%), and Greece (5%). The cirrus and term analyses of the global corpus reveal that “PGI” (n = 2804) and “PDO” (n = 2291) are the most frequently mentioned terms in the Facebook posts, followed by “quality” (n = 1385). “Calabria” is the first region to appear in terms of word counts, while “olive” is the first product (n = 822). It is noteworthy that “recipe” stands out, with 1022 mentions in the corpus. In the collocate analysis, the relationship between “quality” and “products” stands out, with the highest count (context). “PGI” and “Enjoy, it’s from Europe” (the “Enjoy, it’s from Europe” signature has been developed in order to be used by beneficiaries of EU co-financing in promotional material concerning EU agricultural products inside and outside the EU:

https://rea.ec.europa.eu/funding-and-grants/promotion-agricultural-products-0/communicating-your-eu-funded-promotional-campaign-promotion-agricultural-products_en, accessed on 21 April 2025) are also highlighted among the collocate results.

Beyond certification and quality indicators, several terms that express product excellence—such as “taste” (n = 621), “best” (n = 619), “great” (n = 589), “delicious” (n = 579), “unique” (n = 496), and “flavor” (n = 461)—exhibit a moderate presence in the corpus. Moreover, terms that are intrinsically associated with the identity and origin of GI products, such as “season” (n = 662), “place” (n = 649), “region” (n = 568), and “local” (n = 567), appear equally with a moderate frequency, suggesting the poor use of narrative elements tied to territoriality. Most notably, references to sustainability remain marginal in the discourse: the terms “sustainability” (n = 166) and “sustainable” (n = 140) appear only sporadically. In the collocate analysis, although residual, the term “sustainability” appears in association with “PGI”. Among the countries analyzed, Italy, Portugal, and Spain include at least one of these terms in their Facebook communications, with Spain being the only country to mention both terms and presenting the highest number of relevant posts. Contrary to the initial proposition (P1) that GI-certified agricultural producers would emphasise the inherent characteristics of their products—particularly sustainability—in their Facebook communication, the results reveal a different pattern. While certification labels such as PGI and PDO, along with terms related to product quality, appear frequently, sustainability-related terms such as “sustainability” and “sustainable” are used only marginally. Even narrative elements tied to territorial identity (e.g., “place”, “region”, “local”) show moderate and inconsistent presence. Although a residual association between “sustainability” and “PGI” is observed—particularly in Spain, Italy, and Portugal—these references are far from central in the communication strategies.

The analysis of the corpus of Spanish documents revealed that the terms “PDO” (n = 1276), “PGI” (n = 1189), and “quality” (n = 971) were the most frequently mentioned in the Facebook posts. Furthermore, the top 10 word counts reveal the notable prevalence of products, including rice (n = 550), pear (n = 542), and asparagus (n = 527). The region of Málaga emerges as the most prominently positioned in the word counts. The collocate analysis reveals a relationship between products and their regions of production, with a particular emphasis on “PDO” and “Aloreña” (referring to the olive named Aceituna Aloreña de Málaga), Huétor-Tájar asparagus, and rice from Valencia.

The analysis of the corpus of French documents revealed that “PGI” (n = 740) and “PDO” (n = 589) were the most frequently mentioned terms in the Facebook posts, followed by “recipe” (n = 553). Furthermore, the top 10 word counts revealed the notable prevalence of products, including “olive” (n = 448) and “garlic” (n = 413). The regions of Vendée (n = 263) and Lautrec (n = 261) were identified as the most prominent in the word counts. In the collocate analysis, the relationship between products and their regions of production is particularly evident (e.g., Ail Rose de Lautrec—garlic—and IGP Pruneau D’Agen—prune). Furthermore, “PGI” and “Enjoy, it’s from Europe” are also highlighted among the collocate results for the content of French Facebook posts.

The Italian corpus demonstrated a notable prevalence of words related to products from the Calabria region. The region itself is the term with the highest word count, followed by “PGI” (n = 842) and “PDO” (n = 558). Furthermore, “Tropea” (n = 411), a municipality in Calabria, and “Cedro” (n = 364), referring to the Cedar of Calabria PDO, are among the top five words most frequently mentioned in the Facebook posts. The collocate results demonstrate a similar pattern, with prominent relationships observed between Calabria and its products (e.g., Cedro di Calabria PDO—cedar—and Cipolla Rossa di Tropea—onion).

The corpus analysis of Portuguese data revealed the notable prevalence of words associated with the region of production (Loures, n = 378; Odivelas, n = 306; and the Azores, n = 280) and the local market (n = 178) and even the notable presence of a cooperative name (AECSLO, n = 282), which is responsible for Marmelada Branca de Odivelas PGI (Odivelas White Marmalade PGI). The PDO and PGI signatures are barely mentioned in the Portuguese corpus. The collocate results follow a similar pattern, with the strong presence of terms related to the AECSLO, which is a commercial association that does not exclusively represent the certified product.

The Greek corpus exhibited a comparable prevalence of cooperatives, with notable examples including Santowines (n = 148) and ACNAOUSAS (n = 125). Nevertheless, the most frequently mentioned words are “wine” (n = 327) and “wines” (n = 250). These are the products that are most frequently promoted by the SantoWines Cooperative, which is also responsible for the agricultural products “Tomataki Santorinis PDO” (tomato) and “Fava Santorinis DOP”. Agricultural products are not mentioned as frequently in the Greek corpus. The collocate analysis also demonstrated a robust interrelationship between the terms “wine”, “Santorini”, “tourism”, and “experience”.

5. Discussion

This exploratory analysis on the digital promotion of GI products uncovers distinct approaches across Italy, Spain, France, Greece, and Portugal, reflecting broader trends and strategic preferences in leveraging digital platforms.

A digital presence has become essential for small and medium enterprises in the agri-food sector, enabling them to adopt new marketing strategies driven by technological innovation [

3,

5]. Companies are leveraging social media and digital platforms not only to promote products but also to educate and engage consumers on sustainability-related issues [

39], an approach that can be particularly relevant for GI products given their inherent connection to sustainability. Despite the differences between countries, in general, only 16% of the GI products analyzed have no digital presence at all, either on their own websites or on social media platforms. Greece has the lowest score for digital presence, while Spain has the highest percentage of digital presence.

Hypothesis H1 proposed that there would be statistically significant differences among Southern European countries in the number of digital channels used to promote PDO and PGI agricultural products. This hypothesis was supported by the results, indicating that the digital engagement levels vary meaningfully across the five countries. These findings demonstrate that, despite being part of a harmonized EU GI system, there are substantial disparities in how GI-certified producers from different countries adopt and utilize digital platforms for product promotion. e-commerce remains underutilized for GI agricultural products, as shown in previous studies [

6,

7], even though it provides a scalable means of connecting rural producers with broader consumer markets. The variance in e-commerce presence, with France and Greece having the lowest and highest percentages, respectively, indicates different strategies in the use of online sales channels. This divergence suggests an opportunity to develop specific strategies that take into account the local digital infrastructure, consumer behavior, and market access. This gap is especially relevant considering the post-pandemic acceleration of online consumption habits, as described previously [

7].

Overall, a digital presence using a product-centric strategy (the GI product’s name) is strongly preferred among GI producer groups, aiming to capitalize on brand recognition and resonate with consumers’ association of products with their geographical origins and quality [

49,

50]. Italy, France, and Spain demonstrate the robust use of direct product naming in digital marketing. Conversely, Portugal and Greece show a stronger inclination towards using producers’ group names, underscoring a community-oriented branding strategy and suggesting a focus on strengthening the collective reputation and market positioning through a sense of origin and authenticity.

Spain distinguishes itself with the highest utilization rate of Twitter and a significant presence on Instagram, aligned with the cultural engagement with these platforms in Spanish market [

10]. Portugal, in particular, shows notable reliance on Facebook for digital promotion, but Portuguese producers are not exploring Instagram, which is the social media channel with the highest growth rate in the Portuguese market [

10]. Greece exhibits the least engagement across social media channels in promoting its GI products, which might reflect broader social media usage trends within the country.

Given its dominant role among the social media platforms used by GI producer groups, Facebook was selected for a deeper analysis in this study as a representative channel for digital communication practices in the agri-food sector. The analysis of the Facebook presence of agricultural products under the GI scheme provides significant insights into how these products are promoted and engaged with on social media.

One of the critical findings from this study is the variability in the accuracy and completeness of basic information on Facebook Pages across different countries. For example, the presence of an “About” section varied from 40% in France to 63% in Greece. This inconsistency suggests that, while some producer groups recognize the importance of detailed information in building trust and transparency, others may not fully utilize this potential. The provision of accurate basic and comprehensive information on a Facebook Page serves as a quality cue and further signals brand trustworthiness. Furthermore, the sharing of organizational information with customers may signal that the brand cares about its customers [

31].

This study found notable differences in engagement rates and posting frequencies among the countries. France had the highest engagement rate at 2.4%, while Greece and Portugal had the lowest at 1.1%. The overall average engagement rate across all accounts on Facebook is 0.06% [

51]. An analysis of the social media benchmarks per industry indicates that the latest average Facebook engagement rate for the food and beverage industry is 1.93% [

52]. France is the only country that is above average in its engagement rate (2.4%), even having the second-best post frequency (4.7). In addition, Spain has the highest frequency of posts per month at 7.7, with the second-best engagement rate (1.6%). A Spearman correlation analysis focusing on H2 revealed a significant negative correlation between the posting frequency and engagement rate (ρ = −0.20,

p = 0.011). This result refutes the hypothesis and challenges common assumptions about digital marketing. Meta Business [

35], the company that owns Facebook, states that a Facebook Page’s post frequency is an important factor in maintaining engagement with followers and suggests that businesses post one to two times each week. However, the results show that frequent posting by itself does not guarantee better performance, and GI producers should prioritize content quality over quantity. Similar results were found by other authors [

53], where the data indicate that more frequent posting does not necessarily correlate with higher engagement. Instead, the type and quality of content may play a more crucial role in engaging consumers. Spain is the only country that approaches the two times/week frequency, while all other countries exhibits rates close to once per week. Ultimately, Facebook is a communication channel based on interaction and collaboration [

21], so it is crucial to be present and relevant, maintaining frequent posts balanced with quality content [

53].

Overall, a product-centric naming strategy—where the Facebook page is titled after the GI-certified product—is strongly preferred by most GI producer groups. However, the results support H3, indicating that the type of naming strategy, whether focused on the product or on the producer group, does not have a measurable impact on the Facebook engagement rate. This suggests that engagement is not influenced by how the page is named and that producers may prioritize clarity and consistency in their digital presence, rather than the naming format itself. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that each strategy may reflect distinct communication objectives. Naming a Facebook page after the GI product can reinforce brand recognition, leveraging consumers’ associations between geographic origin and product quality [

49,

50]. This approach is particularly evident in Italy, France, and Spain, where product-centric branding is more prominent. In contrast, Portugal and Greece tend to favor naming their Facebook Pages after the producer group, which reflects a more community-oriented strategy. This suggests a focus on collective identity, cooperative branding, and the reinforcement of authenticity and origin-based value in digital communication.

The type of medium used in Facebook publications also showed significant variation. Photos were the most commonly used media across all countries, comprising 63.3% of the total formats used. This preference for photos aligns with the visual nature of social media platforms, where images are more likely to capture user attention and elicit engagement [

53]. However, the use of other media, such as videos and links, was relatively low. Similar results were found in the literature, where the most frequent type used by most fruit and vegetable producers was photos, followed by shared content [

53]. The results of this study indicate that H4 is not supported. Although video content is often regarded as a more engaging format, in this context, it had no statistically significant effect on engagement. This may suggest that videos were not effectively utilized or that other variables—such as content relevance, the posting strategy, or audience characteristics—played a more decisive role in influencing user engagement. It is also important to mention that the high usage of third-party content in Portugal and France is evident, with shared content from other pages accounting for 16.5% and 14%, respectively. This indicates that the Facebook Page relies on third-party content rather than creating its own personalized content. Producer groups should consider diversifying their media strategies. This could involve developing personalized content in accordance with the audience’s needs and interests. Once marketing principles such as product differentiation and segmentation are in place, they will enhance product value and align with evolving consumer preferences [

13,

14,

15].

The analysis of Facebook posts related to Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) agricultural products from five countries—Spain, France, Italy, Portugal, and Greece—reveals several important trends and insights into how these products are promoted and perceived on social media. The global corpus provides a comprehensive overview of the discourse surrounding PDO and PGI products on Facebook. Spain contributes the largest proportion of unique words, reflecting the varying levels of social media activity and engagement across these countries.

The prevalence of terms such as “PGI” and “PDO” across the global corpus serves to illustrate the significance of these designations in the context of marketing and the promotion of agricultural products. It can be reasonably stated that the “PGI” term has a greater presence than the “PDO” term in the sample, given that they represent 60% of GI products. The frequent mention of “quality” serves to highlight a key selling point for these products, suggesting that producers place a strong emphasis on the superior quality associated with PDO and PGI certifications. The term “recipe” also stands out, suggesting that the sharing of culinary uses of these products is a common promotional strategy. Although environmentally responsible consumption patterns are increasingly gaining visibility and encouraging consumers to make more sustainable food choices [

38], the term “sustainability” is rarely used in the promotion or description of GI products on Facebook. Despite the inherent association of GI products with values such as authenticity, cultural heritage preservation, and environmental sustainability [

2], promotional content remains primarily focused on product quality. This represents a missed opportunity, as several studies have demonstrated that digital marketing can play a significant role in advancing sustainability goals by enhancing communication with consumers, promoting sustainable consumption habits, and improving market access [

22,

38,

39].

The analysis of the Facebook posts from Spain and France reveals several similarities in their approaches to promoting PDO and PGI agricultural products. Both Spain and France frequently mention PDO and PGI in their Facebook posts, indicating that both countries place a strong emphasis on these certifications as key selling points for their agricultural products. Regional identity plays a crucial role in the marketing strategies of both Spain and France. The term “quality” is more frequently mentioned in Spanish publications as a crucial attribute that differentiates these products from non-certified ones and justifies their often higher prices. In contrast, France uses culinary applications as a significant promotional strategy, as “recipe” is a frequently mentioned term, indicating a focus on how products can be used in cooking. The use of recipe-type content was also found in a previous study [

53], being the second most promoted type of content on Facebook Pages. Facebook data indicate [

54] that 213 million people globally generated 1.1 billion interactions (posts, comments, likes, and shares) about cooking and baking over a 30-day period.

In Italy, despite the strong presence of PDO and PGI, the strength of words related to Calabria and its products indicates the strong dedication of cooperatives to the promotion of their products and the use of digital tools, such as social media. A similar pattern was observed in the Portuguese and Greek corpuses, which revealed a focus on regions of production and cooperatives. However, in contrast to the other countries, the terms “PDO” and “PGI” were less frequently mentioned in Greece and Portugal. For Portugal, the presence of local market references and cooperative names, such as AECSLO, suggests a different promotional approach, focusing on local community and market engagement rather than formal certifications. On the other hand, for Greece, the strong presence of words related to wine indicates a promotional strategy centered around the wine industry and associated tourism experiences. The collocate analysis reveals a correlation between the terms “wine”, “Santorini”, “tourism”, and “experience”. This suggests that Greek producers capitalize on the appeal of agritourism and local experiences to promote their products.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This article has explored the intersection between sustainability and digitalization in the promotion of PDO and PGI agricultural products in Southern Europe, drawing exclusively on empirical data collected from Italy, Spain, France, Portugal, and Greece. The results show that, while digital tools—especially websites and social media—are increasingly present in the communication strategies of GI producer groups, their potential remains largely underused. The analysis revealed inconsistencies in digital engagement, a lack of strategic content planning, and the limited use of tools such as e-commerce, despite their capacity to improve market access and consumer proximity.

While some countries, such as Spain and France, present more robust strategies, especially on websites, others struggle to link their digital presence to their unique territorial value propositions. In addition, Facebook, the most widely used platform across the five countries, is often underused or poorly maintained. The completion of the Facebook Page’s basic information is often neglected, and posts tend to rely heavily on photos and shared third-party content. However, the findings showed that H2 and H4 were not supported, revealing that neither posting more frequently nor using videos necessarily results in higher engagement, highlighting the importance of content relevance and strategic alignment over format or frequency.

GI products are, by their very nature, ready-made for storytelling and marketing. They combine elements that are highly valued by modern consumers, such as tradition, authenticity, cultural identity, and sustainable production practices. However, these intrinsic attributes are not often articulated in a structured and consistent manner across digital platforms. The content analysis based on Facebook posts revealed that terms such as “quality” and “recipe” dominate the discourse, while keywords such as “sustainability” or “tradition” are virtually absent, despite being fundamental to the GI concept. The persistent focus on quality as the central promotional theme—while important—seems insufficient to generate meaningful interactions with consumers. Attributes that are inherently tied to GI products, such as sustainability, origin, cultural heritage, or seasonality, appear underrepresented in communication efforts, despite being highly valued in academic and policy discussions on territorial branding. This points to a missed opportunity: at a time when consumers are looking for transparency and purpose in what they consume, GI products have the credentials but lack the communication.

Moreover, H3 was confirmed, i.e., the naming strategy (product name vs. producer group) does not affect engagement, raising questions about brand identity versus collective identity in digital marketing. The cases of Portugal and Greece, where pages are more frequently named after producer groups and engagement remains notably low, suggest a possible disconnect between strategic intent and digital execution—or even the absence of clear digital objectives.

From a management and policy perspective, these findings highlight the need for capacity building, particularly in digital communication and marketing skills, among producer organizations. Investment in training and support, particularly small-scale and rural cooperatives, could help to transform fragmented efforts into strategic communication plans that reinforce not only product visibility but also the broader territorial development objectives of the GI system. In addition, tailored national or regional strategies could be developed to address the specific challenges and potential of each country, building on existing strengths while addressing gaps in consistency and sustainability messaging. Finally, policy efforts should aim to stimulate the broader adoption of digital tools, moving beyond a basic digital presence and fostering more meaningful engagement with consumers through training, funding, and knowledge-sharing platforms. In short, GI products already have a strong narrative—what they often lack is the digital strategy to tell it well.

While this study offers relevant insights, it is not without limitations. Firstly, the identification of producer groups depended on the information available on the GI View portal, which was incomplete for several products—especially in Italy, Spain, and France. This required additional searches through PDF documents and online content, whose accuracy and relevance could not always be verified. Secondly, the analysis focused primarily on Facebook, excluding other social media platforms, which may be increasingly relevant for specific markets or audiences. This study adopted a quantitative and observational approach, without incorporating the voices of producers themselves, which limited the interpretation of the digital strategy’s effectiveness and its practical constraints. Translating Facebook content into English may have resulted in the partial loss of contextual nuance and cultural meaning, which could have affected the depth of the content analysis. As a final limitation, it is important to note that, due to the dynamic nature of social media, the replicability of this study may be partially constrained. Since Facebook Pages and digital activity are continuously evolving, the sample may change over time—producers who were inactive during the data collection period may resume posting, while others may remove or alter their content. Therefore, future studies conducted in other countries or at different times may not be able to fully replicate our data or results.

Future research could deepen the understanding of digital promotion strategies for GI-certified products by moving beyond presence analysis to explore qualitative dimensions of communication. This includes analyzing how agricultural products with GIs are positioned and communicated across various digital platforms—such as Instagram, YouTube, or TikTok—with attention to visual identity, storytelling, and audience interaction. Importantly, future studies should also address the potential selection bias introduced by focusing solely on Facebook, as this platform may not represent the full diversity of digital behaviors among producer groups. Including a broader range of social media channels would offer a more comprehensive and balanced view of digital engagement. Additionally, expanding the geographical scope to include more EU and non-EU countries would allow for comparative insights into how cultural, economic, and institutional factors shape digital strategies and consumer perceptions. To improve the depth and validity of the findings, future research should also integrate qualitative methods, such as interviews or participatory approaches, to directly capture producer perspectives, strategic decisions, and capacity-building needs. This would contribute to the development of more effective and context-sensitive digital communication frameworks for GI promotion.