Examining the Formation of Resident Support for Tourism: An Integration of Social Exchange Theory and Tolerance Zone Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ethnic Tourism

2.2. Resident Support for Tourism

2.3. Tolerance

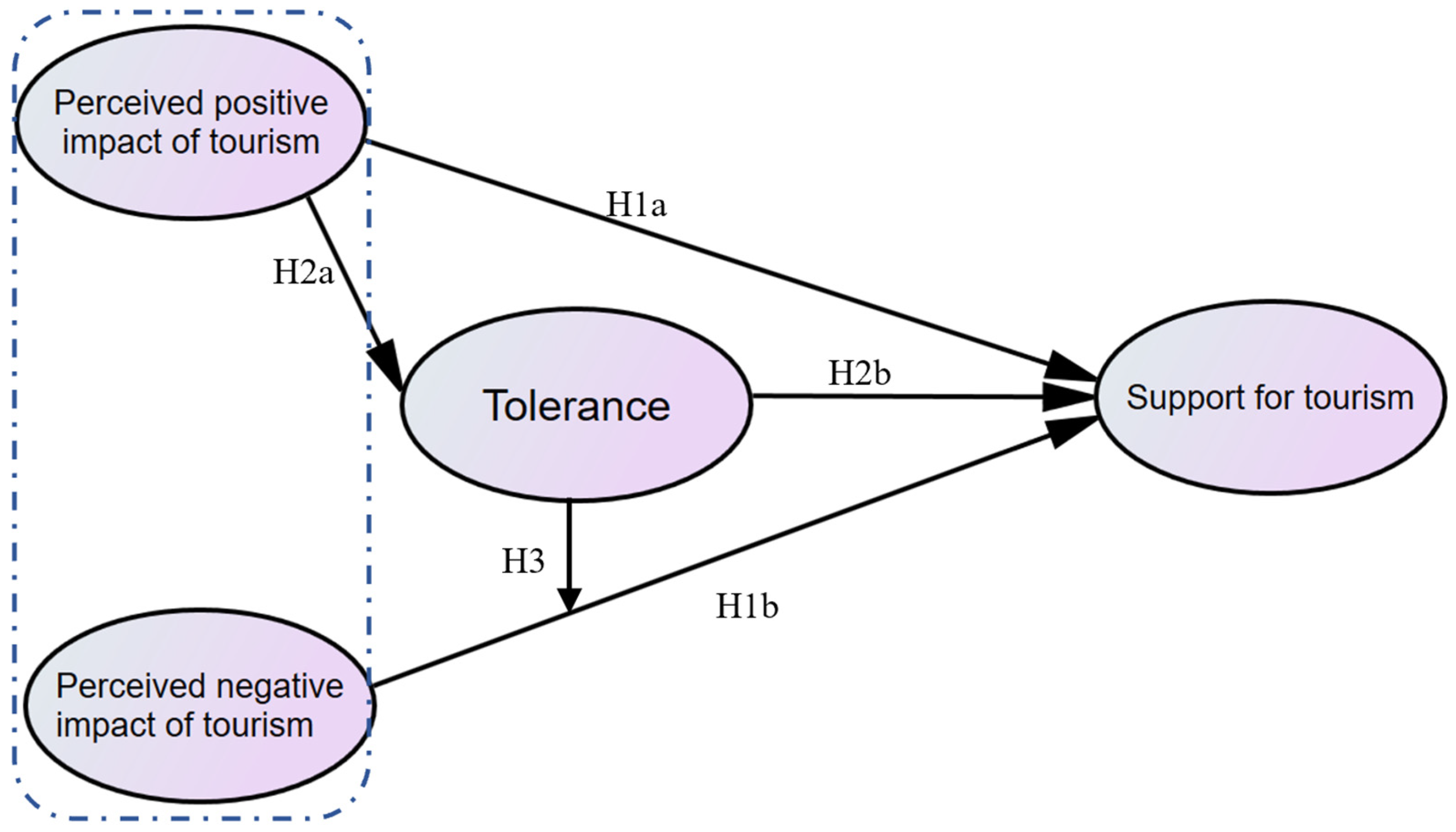

3. Hypothesized Model

3.1. Tourism Impacts and Resident Support: Social Exchange Theory

3.2. The Role of Tolerance: Zone of Tolerance Theory

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Sites: Xijiang Miao Village and Zhaoxing Dong Village

4.2. Questionnaire and Measurement

4.3. Sample and Data Collection

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Data Analysis

5.2. Common Method Bias

5.3. Reliability and Validity

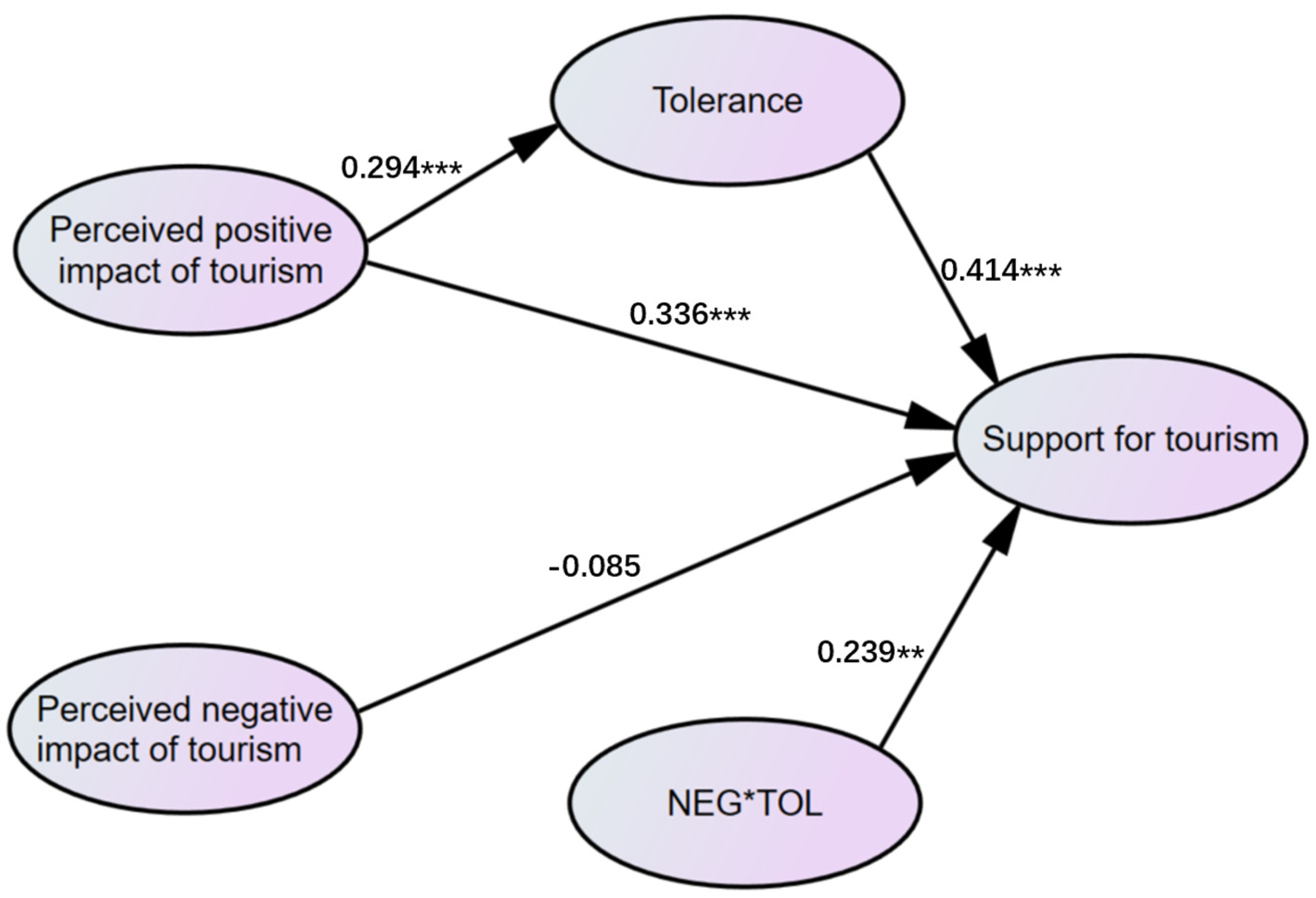

5.4. Hypothesis Test

5.4.1. Main Effect

5.4.2. Mediating and Moderating Effects

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Key Findings

- (1)

- Social exchange theory exhibits strong explanatory power in interpreting the relationship between residents’ perceptions of tourism and their support for the development of tourism. Specifically, residents’ positive perceptions of tourism show a significant positive correlation with support for tourism, while negative perceptions demonstrate a significant negative correlation. Our findings affirm the explanatory power of social exchange theory in the context of ethnic tourism, aligning with the conclusions of Nugroho and Numata [13], as well as Munanura and Kline [29]. This supports the widely held view in existing research that social exchange theory is one of the most important and prevalent frameworks for studying residents’ attitudes and behaviors [86,87].

- (2)

- The study confirms the complex dual role of tolerance—acting as a mediator between positive perceptions and support for tourism, while simultaneously serving as a moderator in the relationship between negative perceptions and support. This finding responds to the research suggestions of Qin et al. and Qi et al. [4,11,61], revealing the intrinsic mechanism of the classic “tourism perception-support” paradigm in existing studies through the introduction of the tolerance construct. Moreover, it verifies that tolerance indeed exerts a significant influence on the relationship between residents’ perceptions of tourism and their support for tourism.

- (3)

- The integration of social exchange theory and zone of tolerance theory provides an effective framework for analyzing the underlying mechanisms linking residents’ perceptions of tourism and their support behavior. This theoretical synthesis enhances our understanding of the factors influencing residents’ support for the development of tourism. This study aligns with the theoretical integration trend advocated by scholars such as Gursoy et al. [28], Gautam [12], and Hateftabar and Rasoolimanesh [35], demonstrating that combining social exchange theory with the zone of tolerance theory indeed enhances the explanatory power regarding residents’ support for tourism.

7.2. Theoretical Implications

7.3. Management Implications

7.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ganji, S.F.G.; Johnson, L.W.; Sadeghian, S. The effect of place image and place attachment on residents perceived value and support for tourism development. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Luo, H.; Bao, J. A longitudinal study of residents’ attitudes toward tourism development. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3309–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munanura, I.E.; Needham, M.D.; Lindberg, K.; Kooistra, C.; Ghahramani, L. Support for tourism: The roles of attitudes, subjective wellbeing, and emotional solidarity. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Shen, H.; Ye, S.; Zhou, L. Revisiting residents’ support for tourism development: The role of tolerance. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Residents’ attitudes towards tourism, cost–benefit attitudes, and support for tourism: A pre-development perspective. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2023, 20, 522–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Boley, B.B.; Yang, F.X. Resident empowerment and support for gaming tourism: Comparisons of resident attitudes pre-and amid-Covid-19 pandemic. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 47, 1503–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.R.M.d.; Pereira, L.N.; Pinto, P.; Boley, B.B. Imperialism, empowerment, and support for sustainable tourism Can residents become empowered through an imperialistic tourism development model. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 53, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Political trust and residents’ support for alternative and mass tourism: An improved structural model. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 19, 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sanchez, A.; Valle, P.O.d.; Mendes, J.d.C.; Silva, J.A. Residents’ attitude and level of destination development: An international comparison. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, H.; Ye, S.; Zhou, L. Being rational and emotional: An integrated model of residents’ support of ethnic tourism development. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, R.; So, K.K.F.; Cárdenas, D.A.; Hudson, S. The missing link in resident support for tourism events: The role of tolerance. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 47, 422–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, V. Why local residents support sustainable tourism development? J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, P.; Numata, S. Resident support of community-based tourism development: Evidence from Gunung Ciremai National Park, Indonesia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 2510–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V. Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, H.-G.; Xing, W. The host–guest interactions in ethnic tourism, Lijiang, China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, X. How and why does place identity affect residents’ spontaneous culture conservation in ethnic tourism community? A value co-creation perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1344–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, N.; Wilson, E. From Invisible to Indigenous-Driven A Critical Typology of Research in Indigenous Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2012, 19, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wall, G. Ethnic tourism: A framework and an application. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Nunkoo, R.; Alders, T. London residents’ support for the 2012 Olympic Games: The mediating effect of overall attitude. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, P.; Gursoy, D.; Sharma, B.; Carter, J. Structural modeling of resident perceptions of tourism and associated development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; An, K.; Jang, S.C.S. Behaviours not set in stone do residents still adopt pro-tourism behaviours when tourists behave in uncivilized ways. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 27, 4503–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Fan, L.; Zhou, L.; Ye, S. Revisiting residents’ support through collective rationality. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, R.R.; Long, P.T.; Allen, L. Resident support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J. Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism Impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurowski, C.; Uysal, M.; Williams, D.R. A Theoretical Analysis of Host Community Resident Reactions to Tourism. J. Travel Res. 1997, 36, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.L.; Feng, X. Residents’ sense of place, involvement, attitude, and support for tourism: A case study of Daming Palace, a Cultural World Heritage Site. Asian Geogr. 2020, 37, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Yolal, M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Panosso Netto, A. Impact of Trust on Local Residents’ Mega-Event Perceptions and Their Support. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Ouyang, Z.; Nunkoo, R.; Wei, W. Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: A meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munanura, I.E.; Kline, J.D. Residents’ Support for Tourism: The Role of Tourism Impact Attitudes, Forest Value Orientations, and Quality of Life in Oregon, United States. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2023, 20, 566–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Residents’ support for tourism: An Identity Perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erul, E.; Woosnam, K.M.; McIntosh, W.A. Considering emotional solidarity and the theory of planned behavior in explaining behavioral intentions to support tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1158–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, A.; Moghavvemi, S.; Hamzah, A. The Impact of Emotional Solidarity on Residents’ Attitude and Tourism Development. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 0157624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Aleshinloye, K.D. Can Tourists Experience Emotional Solidarity with Residents? Testing Durkheim’s Model from a New Perspective. J. Travel Res. 2012, 52, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wan, Y.K.P. Residents’ support for festivals: Integration of emotional solidarity. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hateftabar, F.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Crisis-driven shifts in resident pro-tourism behaviour. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 27, 4479–4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, R.; Borgida, M.; Cuffaro, M. The conditions of tolerance. Politics Philos. Econ. 2011, 11, 322–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLain, D.L. The Mstat-I: A New Measure of an Individual’S Tolerance for Ambiguity. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1993, 53, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLain, D.L. Evidence of the properties of an ambiguity tolerance measure: The Multiple Stimulus Types Ambiguity Tolerance Scale-II (MSTAT-II). Psychol. Rep. 2009, 105, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L.; Zeithaml, V.A. Understanding Customer Expectations of Service. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1991, 32, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G.; Meng, J.; Kou, X.-X. A Comprehensive Review and Extension of ZOT Theory. Manag. Rev. 2004, 16, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadiri, H.; Hussain, K. Diagnosing the zone of tolerance for hotel services. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2005, 15, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Huang, C.-C.; Luoh, H.-F. Do travel product types matter Online review direction and persuasiveness. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Liu, Y.; Luo, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, C. Does a cute artificial intelligence assistant soften the blow The impact of cuteness on customer tolerance of assistant service failure. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, A.; Maritz, A.; Mehta, S. Enhancing Singapore travel agencies’ customer loyalty an empirical investigation of customers’ behavioural intentions and zones of tolerance. Interam. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 9, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.; Gao, Y. A failure of UK travel agencies to strengthen zones of tolerance. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2005, 5, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, S.O. Evaluating Young Customers’ Perception of Service Quality Offered by Travel Agencies in North Cyprus Using Their Zone of Tolerance; Eastern Mediterranean University: Famagusta, Cyprus, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.; An, S.; Suh, J. How do tourists with disabilities respond to service failure an application of affective events theory. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksi, A.K. Mapping Zone of Tolerance from Destination Atmospherics. Asia-Pac. J. Innov. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms; Harcourt, Brace & World: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.-K. On the Theory of Coleman’s Social Capital. J. Beihua Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2005, 6, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, H.-Y.; Chang, S.-T. Resident perceptions and support before and after the 2018 Taichung international Flora exposition. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2110–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Shapovalova, A.; Lan, W.; Knight, D.W. Resident support in China’s new national parks: An extension of the Prism of Sustainability. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 1731–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Hacikara, A.; Baker, C.; Fyall, A.; Pizam, A. Measuring the perceived impacts of tourism a scale development study. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 2516–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, P.S.; Lei, C.K.; Zhai, T. Investigating the bidirectionality of the relationship between residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts and subjective wellbeing on support for tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 852–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjerald, O. Sociocultural Impacts of Tourism: A Case Study from Norway. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2005, 3, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana-Lora, A.; Orgaz-Agüera, F.; Aguilar-Rivero, M.; Moral-Cuadra, S. Does the education level of residents influence the support for sustainable tourism? Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 3165–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The nature and determinants of customer expectations of service. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1993, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J.; Crompton, J.L. Residents’ Strategies for Responding to Tourism Impacts. J. Travel Res. 1993, 32, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, Y.; Ginosar, O. Determinants of Locals’ Perceptions and Attitudes Towards Tourism Development in their Locality. Geoforum 1994, 25, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, E.J.; Kirby, V.G.; Steel, G.D. Perceptions of Antarctic tourism: A question of tolerance. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, R.; So, K.K.F.; Cardenas, D.; Hudsonn, S.; Meng, F. The Mediating Effects of Tolerance on Residents’ Support Toward Tourism Events. In Proceedings of the Travel and Tourism Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally, Dubai, Saudi Arabia, 3–4 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zajac, R.M.; Bruskotter, J.T.; Wilson, R.S.; Prange, S. Learning to Live With Black Bears: A Psychological Model of Acceptance. J. Wildl. Manag. 2012, 76, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lischka, S.A.; Riley, S.J.; Rudolph, B.A. Effects of impact perception on acceptance capacity for white-tailed deer. J. Wildl. Manag. 2008, 72, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu Zhang, H.; Fan, D.X.F.; Tse, T.S.M.; King, B. Creating a scale for assessing socially sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haukeland, J.V.; Veisten, K.; Grue, B.; Vistad, O.I. Visitors’ acceptance of negative ecological impacts in national parks comparing the explanatory power of psychographic scales in a Norwegian mountain setting. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riorini, S.V.; Barusman, A.R.P. Zone-of-Tolerance Moderates Satisfaction, Customer Trust and Inertia—Customer Loyalty. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309060830_Zone-of-tolerance_moderates_satisfaction_customer_trust_and_inertia_-_Customer_loyalty (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Gorla, N. Information Systems Service Quality, Zone of Tolerance, and User Satisfaction. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2012, 24, 50–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The Concept of a Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Resources. Can. Geogr. Géographe Can. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.-W.; Stewart, W.P. A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Plaza-Mejía, M.d.l.Á.; Porras-Bueno, N. Understanding Residents’ Attitudes toward the Development of Industrial Tourism in a Former Mining Community. J. Travel Res. 2009, 47, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Andereck, K.L. Factors Predicting Rural Residents’ Support of Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Látková, P.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ Attitudes toward Existing and Future Tourism Development in Rural Communities. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ma, Y.; Cang, M. Report on Tourism Development of China’s Xijiao Miao Village; Sicial Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning, EMEA: Andover, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Pinto, P.; Silva, J.A.; Woosnam, K.M. Residents’ attitudes and the adoption of pro-tourism behaviours: The case of developing island countries. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. Assessing progress of tourism sustainability: Developing and validating sustainability indicators. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 1998, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 98, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F. Moderation in management research: What, Why, When, and How. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Li, F.S.; Ma, J. Dual identity and ambivalent sentiment of border residents Predicting border community support for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2025, 106, 105000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erul, E.; Uslu, A.; Cinar, K.; Woosnam, K.M. Using a value-attitude-behaviour model to test residents pro-tourism behaviour and involvement in tourism amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 3111–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Village | ||||

| Male | 289 | 56.2 | Xijiang | 275 | 53.5 |

| Female | 211 | 41.1 | Zhaoxing | 239 | 46.5 |

| Missing | 14 | 2.7 | Annual income (RMB) | ||

| Age | ≤24,000 | 198 | 38.5 | ||

| <18 | 15 | 2.9 | 24,001–48,000 | 141 | 27.4 |

| 18–30 | 213 | 41.4 | 48,001–72,000 | 105 | 20.4 |

| 31–45 | 145 | 28.2 | 72,001–96,000 | 30 | 5.8 |

| 46–60 | 97 | 18.9 | >96,000 | 15 | 2.9 |

| >60 | 37 | 7.2 | Missing | 25 | 4.9 |

| Missing | 7 | 1.4 | Duration of residence | ||

| Education | <1 year | 14 | 2.7 | ||

| Secondary school | 210 | 40.9 | 1–5 years | 38 | 7.4 |

| High school | 103 | 20 | 6–10 years | 33 | 6.4 |

| Junior college | 83 | 16.1 | 11–20 years | 105 | 20.4 |

| College | 95 | 18.5 | >20 years | 317 | 61.7 |

| Post-graduate | 6 | 1.2 | Missing | 7 | 1.4 |

| Missing | 17 | 3.3 | Engagement in tourism | ||

| Local residents | Yes | 167 | 32.5 | ||

| Yes | 465 | 90.5 | No | 332 | 64.6 |

| No | 43 | 8.4 | Missing | 15 | 2.9 |

| Item | Loading | Variable | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POS1 | 0.764 *** | Perceived positive impact of tourism | 0.813 | 0.82 | 0.536 |

| POS2 | 0.846 *** | ||||

| POS3 | 0.719 *** | ||||

| POS4 | 0.571 *** | ||||

| NEG1 | 0.705 *** | Perceived negative impact of tourism | 0.711 | 0.700 | 0.535 |

| NEG2 | 0.757 *** | ||||

| SUP1 | 0.802 *** | Support for tourism | 0.927 | 0.925 | 0.711 |

| SUP2 | 0.899 *** | ||||

| SUP3 | 0.919 *** | ||||

| SUP4 | 0.806 *** | ||||

| SUP5 | 0.781 *** | ||||

| TOL1 | 0.723 *** | Tolerance for tourism | 0.791 | 0.796 | 0.495 |

| TOL2 | 0.628 *** | ||||

| TOL3 | 0.667 *** | ||||

| TOL4 | 0.787 *** |

| POS | NEG | SUP | TOL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POS | 0.732 | |||

| NEG | −0.343 | 0.731 | ||

| SUP | 0.242 | −0.212 | 0.843 | |

| TOL | 0.176 | −0.184 | 0.176 | 0.704 |

| Variables | Support for Tourism | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Collinearity Statistics | ||||||

| β | T | Sig | β | T | Sig | Tolerance | VIF | |

| (Constant) | 19.586 | 0.000 | 8.102 | 0.000 | ||||

| Gender | −0.029 | −0.614 | 0.540 | −0.040 | −0.916 | 0.360 | 0.968 | 1.033 |

| Age | 0.048 | 0.869 | 0.385 | −0.007 | −0.138 | 0.890 | 0.724 | 1.381 |

| Education | 0.004 | 0.081 | 0.936 | 0.001 | 0.029 | 0.977 | 0.714 | 1.400 |

| Annual income | −0.083 | −1.714 | 0.087 | −0.086 | −1.960 | 0.051 | 0.951 | 1.052 |

| POS | 0.336 *** | 6.185 | 0.000 | 0.614 | 1.630 | |||

| NEG | −0.129 ** | −2.368 | 0.018 | 0.610 | 1.641 | |||

| R2 | 0.009 | 0.190 | ||||||

| △R2 | 0.009 | 0.181 | ||||||

| F | 1.068 | 17.454 *** | ||||||

| Path | Effect | Boot | Bias-Corrected 95% CI | Percentile 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S.E | Lower | Upper | P | Lower | Upper | P | ||

| POS → TOL → SUP | ||||||||

| Indirect effect | 0.122 | 0.032 | 0.067 | 0.189 | 0.000 | 0.067 | 0.190 | 0.000 |

| Direct effect | 0.336 | 0.107 | 0.134 | 0.552 | 0.003 | 0.137 | 0.556 | 0.003 |

| Total effect | 0.458 | 0.110 | 0.251 | 0.684 | 0.002 | 0.260 | 0.692 | 0.001 |

| TOL | Effect | SE | T-Value | p-Value | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low TOL (M − 1SD) | −0.340 | 0.050 | −6.794 | 0.000 | −0.439 | −0.242 |

| TOL(M) | −0.241 | 0.037 | −6.450 | 0.000 | −0.314 | −0.167 |

| High TOL (M + 1SD) | −0.141 | 0.052 | −2.728 | 0.007 | −0.242 | −0.039 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, X.; Ye, S.; Xiang, F.; Wang, C. Examining the Formation of Resident Support for Tourism: An Integration of Social Exchange Theory and Tolerance Zone Theory. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4921. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114921

Qin X, Ye S, Xiang F, Wang C. Examining the Formation of Resident Support for Tourism: An Integration of Social Exchange Theory and Tolerance Zone Theory. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4921. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114921

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Xue, Shun Ye, Fuhua Xiang, and Chunyan Wang. 2025. "Examining the Formation of Resident Support for Tourism: An Integration of Social Exchange Theory and Tolerance Zone Theory" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4921. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114921

APA StyleQin, X., Ye, S., Xiang, F., & Wang, C. (2025). Examining the Formation of Resident Support for Tourism: An Integration of Social Exchange Theory and Tolerance Zone Theory. Sustainability, 17(11), 4921. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114921

_Li.png)