A Pathway to Sustainable Agritourism: An Integration of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Resource Dependence Theories

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Agritourism: Critical Success Factors

2.2. Agritourism and COVID-19

2.3. Policy Role in Agritourism

2.4. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Resource Dependence Theories

2.4.1. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

2.4.2. Resource Dependence Theory (RDT)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Context

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

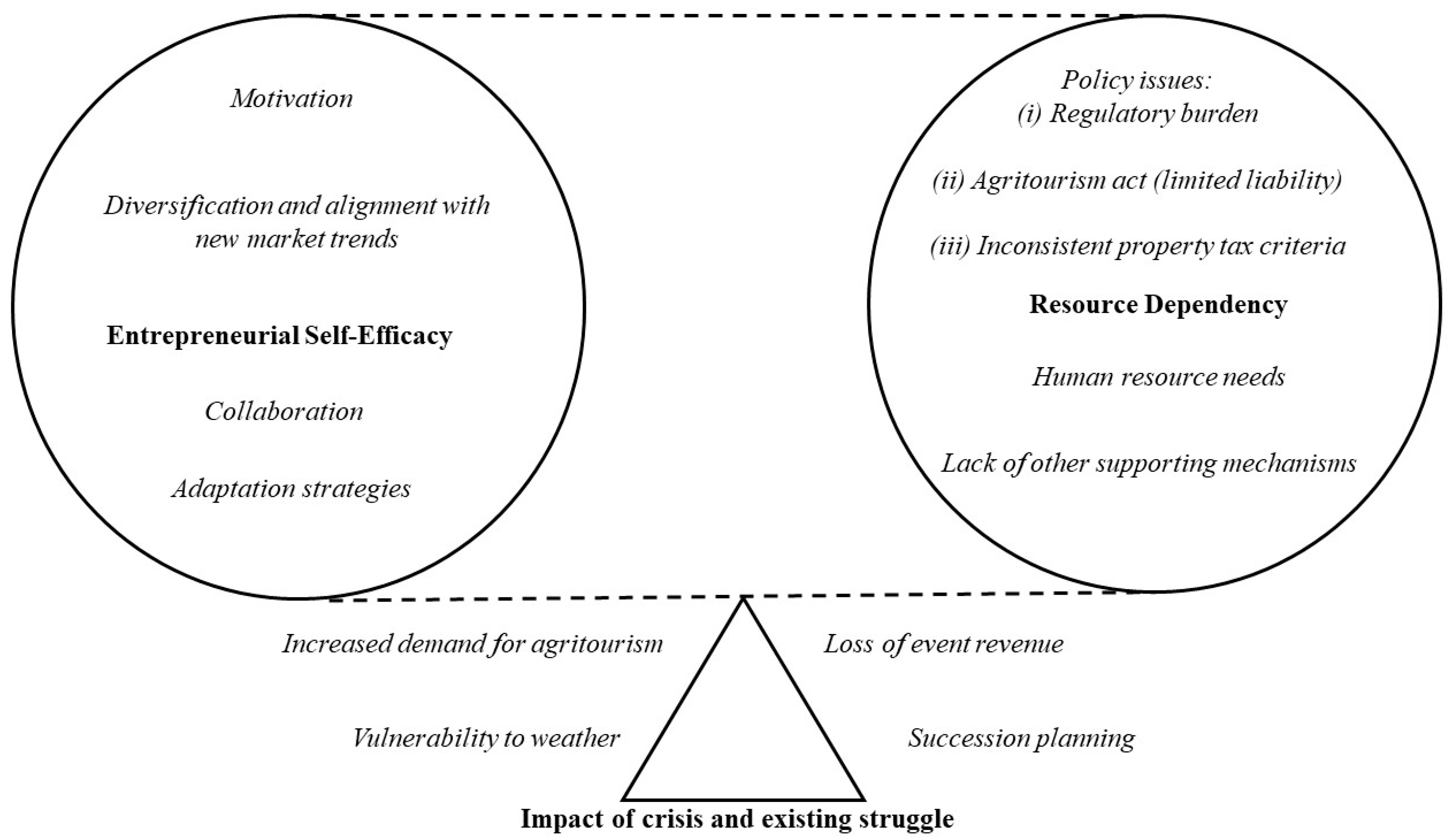

4. Results

4.1. Impact of Crisis and Existing Struggle

4.1.1. Increased Demand for Nature-Based Tourism

It was the best thing that ever happened to our business. We had so many more customers coming. We lost all our chefs, who had previously been 40% of our business. But we gained way more and new people […] A lot of that has been maintained, though some of them, you know, they just came during the scariest times. We probably still have more regular customers than we did previously, and now the chefs are back, too. We had a great year financially in 2020.(AB07, U-pick farm)

4.1.2. Loss of Event Revenue

Our event center conducts weddings, private events, showers, and retirement parties. We got constant postponements. Because people are postponing our dates, we are filling up, and we had to refund people’s money because they had to cancel their events. We still had to fulfill our contracts and still make wine.(AB12, winery)

4.1.3. Succession Planning

[I’m] pushing 60, and I have three kids with no interest in it at all. Everything I’ve built is just going to go down. Kids just don’t want to keep going. It’s just Father’s deal; they all have their own lives and good jobs.(AB09, family activity farm)

4.1.4. Vulnerability to Weather

I can’t make it rain when we’re dry, and I can’t make it not rain when we are already wet and muddy. Some people get a rainstorm, and they’re out of business for the weekend. So, the weather is probably our greatest disadvantage. We can’t overcome the weather, and we can’t predict it.(AB20, family activity farm)

4.2. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

4.2.1. Motivation

Success has changed its definition through the years. Now older and wiser, I would say happy guests and, more importantly, changed guests, changed opinions about our environment and our power to change our environment […] I feel like it’s a success when someone says they are going to change their behavior to be more environmentally friendly.(AB02, nature reserve cabins)

People are increasingly isolated and don’t know where they come from. I think giving them a vision of what’s out there besides the grocery store and just going to the office and coming home. I think we’re providing a valuable thing to society.(AB13, flower farm)

4.2.2. Diversification and Alignment with New Market Trends

Day of the Dead is a huge floral holiday here in Texas […] We reduced bucket prices that week to help promote that tradition because it’s just so fundamentally enriching for families […] Since COVID, so many people have died […] And there were people the year before and then the first year of COVID who had never done an altar.(AB01, flower farm)

The mental health of the world and that whole niche of tourism has really exploded. My goal is to add maybe a yoga class or build a greenhouse where we could have it. I’m going to call it the guest garden, and they can come to my garden really, but I’ll share it with anybody who wants […] We asked all of our guests to compost. We have a small compost container in each cabin, and I want them to see the compost that they use over the weekend—I want them to see the full cycle.(AB02, nature reserve cabins)

4.2.3. Collaboration

Most of my information comes from my competition, and in a good way. And I’ll share it with them in a heartbeat. I’m part of Texas. I’m part of the Texas Beekeepers’ Association. I spoke about agritourism at the last convention. I have no secrets. I welcome anyone who wants to do it. I actually think the more people that do it, the better off we are. We’ve got more customers than we can handle.(AB03, apiary)

4.2.4. Adaptation Strategies

Because we were limited by the number of visitors we could have during COVID-19, where we could only have about 100 visitors at a time, we chose not to have children take those seats from the adults who were going to buy some wine. So, we stopped having children. Once COVID-19 stopped, we put out a survey to our wine club members. 78% of our members said we don’t want children. Let’s keep things the way they are. And we have a huge percentage of teachers, and they’re like, I have enough to deal with at school. Can you please leave it without the kids? It’s been a great change.(AB08, vineyard)

4.3. Resource Dependency

4.3.1. Policy Issues

Regulatory Burden

We just try to stay away from the government because they don’t do anything helpful, sparsely, from our experience. They always just want season times and all that. So, we don’t make enough money from agriculture. The Texas Department of Agriculture has come out to check in, and we make sure that we make little enough in this so that we don’t have to do all the extensive record-keeping that larger farming businesses have to do. You know, like keeping track of when you put a seed in the ground […] and record every single step you do—if you’re a bigger operation. So, since we’re so small, we never have to do that.(AB07, U-pick farm)

Agritourism Act (Limited Liability)

We have posted the Texas law […] that you’re coming on a working farm. We have posted that at every entrance to our farm, as well as at a few other locations. But other than that, we’re insured, obviously, where we have the customer sign a waiver. So, we use a program […] for our bookings, and when they sign up for anything at our farm, they have to sign a waiver. It’s all electronic and recorded. I can’t imagine following the paper on that.(AB03, apiary)

Inconsistent Property Tax Exemption Criteria

We have had this fantastic situation in Texas where people can get an ag exemption with honeybees since 2011. So, if you own five acres to 20 acres, or if you have an improvement on your property, if you own six to 21 acres […] you could get honeybees instead and get a reduction on your property taxes.(AB03, apiary)

I would love for lavender to be considered a crop so that we could get an ag (agriculture) exemption. Because right now, we pay full taxes. Our land is not considered for an exemption, even though we are farming on it.(AB06, lavender farm)

4.3.2. Human Resource Needs (e.g., Labor Shortage and Guest Worker Policy)

Long hours. Hard, physical work. Do you want to work in the tasting room for me? The first thing I ask is, can you pick up 45 pounds because a case of wine is 40 pounds. You’re on your feet a lot, and if you work at the winery, it’s physical. Wines never sleep, so long hours are part of the business.(AB15, vineyard)

The ability to hire non-US workers more easily would be helpful. Right now, the estimate is that it would cost us because you must provide housing and stuff like that […] about $75,000 a year for two workers. You are paying for average fees and all that kind of stuff. However, you cannot even qualify for them because all the slots—not just all the needs, but all the available slots for workers—are occupied. So, it would be extremely helpful if there were a bit more flexibility in those slots to hire our guest workers. And bring them in to help, particularly in agriculture.(AB10, Christmas tree farm)

4.3.3. Lack of Other Supporting Mechanisms (e.g., Signage/Marketing Needs and Extension Service Expertise and Training Needs)

It would help smaller farms not to have someone showing up at their door all the time because they’re not open. I have seen reviews complaining that “I drove all the way back in there, and the gate was closed.” I think there might be a way for Texas to tackle that.(AB03, apiary)

So, when we first started, I worked with our original owners and our ag extension agent […] He came out and helped a lot with the original owners, getting everything lined out and how to move forward. But that was years ago, and since then, we’ve kind of just done it on our own […] It would be beneficial if they were more engaged or had more resources […] That would be fabulous. The problem is that most of them are more crop, plant, or tree-based […] [our product] is such a different critter. That is not normally their specialty. [He] helped us do a ton of research and find out more, but even universities do not really study what we are growing.(AB06, lavender farm)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Agricultural Law Center. Agritourism Overview. 2021. Available online: https://nationalaglawcenter.org/overview/agritourism/ (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Ammirato, S.; Felicetti, A.M.; Raso, C.; Pansera, B.A.; Violi, A. Agritourism and sustainability: What we can learn from a systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, K.; Barbieri, C.; KC, B.; Roman, M. Agritourism and sustainability: Advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Tour. Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTO; UNDP. Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. Agritourism. 2021. Available online: https://www.agmrc.org/foodsystems/agritourism (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Adom, D.; Alimov, A.; Gouthami, V. Agritourism as a preferred travelling trend in boosting rural economies in the post-COVID-19 period: Nexus between agriculture, tourism, art and culture. J. Migr. Cult. Soc. 2021, 1, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- KC, B. From pre-pandemic to post-pandemic struggles to meet sustainable development goals. Indones. J. Tour. Leis. 2023, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Grudzień, P. The essence of agritourism and its profitability during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Agriculture 2021, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Federation of Independent Businesses. Small Business FAQs on COVID-19. NFIB. 2020. Available online: https://assets.nfib.com/nfibcom/Small-Business-FAQs-on-COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Baipai, R.; Chikuta, O.; Gandiwa, E.; Mutanga, C. A critical review of success factors for sustainable agritourism development. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2021, 10, 1778–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baipai, R.; Chikuta, O.; Gandiwa, E.; Mutanga, C.N. A framework for sustainable agritourism development in Zimbabwe. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2201025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; He, G. Agritourism development in the USA: The strategy of the state of Michigan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, K.; Ohe, Y.; Ciani, A. Which human resources are important for turning agritourism potential into reality? swot analysis in rural Nepal. Agriculture 2020, 10, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăgoi, M.C.; Iamandi, I.E.; Munteanu, S.M.; Ciobanu, R.; Țarțavulea, R.I.; Lădaru, R.G. Incentives for developing resilient agritourism entrepreneurship in rural communities in Romania in a European context. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, C.; Barbieri, C. The perceived benefits of agritourism: The provider’s perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.; Chang, C.; Wu, K.; Lin, C.R.; Kalnaovkul, B.; Tan, R.R. Sustainable agritourism in Thailand: Modeling business performance and environmental sustainability under uncertainty. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, J. Factors affecting the income of agritourism operations: Evidence from an eastern Chinese county. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quella, L.; Chase, L.; Conner, D.; Reynolds, T.W.; Schmidt, C. Perceived success in agritourism: Results from a study of US agritourism operators. J. Rural Community Dev. 2023, 18, 140–158. [Google Scholar]

- Hollas, C.R.; Chase, L.; Conner, D.; Dickes, L.; Lamie, R.D.; Schmidt, C.; Singh-Knights, D.; Quella, L. Factors related to profitability of agritourism in the United States: Results from a national survey of operators. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, C.C.; van der Merwe, P. Critical success factors for developing and managing agri-tourism: A South African approach. Int. Conf. Tour. Res. 2022, 15, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazami, N.; Lakner, Z. Influence of social capital, social motivation and functional competencies of entrepreneurs on agritourism business: Rural lodges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccio, V.; Giannelli, A.; Mastronardi, L. Explaining determinants of agri-tourism income: Evidence from Italy. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, M.; Roman, M.; Prus, P. Features and challenges of agritourism: Evidence from Iran and Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, M.F.; Barbieri, C.; Morais, D.B.; Jakes, S.; Seekamp, E. Beyond economic earnings: The holistic meaning of success for women in agritourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, D.K.; Kumbhare, N.V.; Sharma, D.K.; Kumar, P.; Bhowmik, A. Facilitating factors for a successful agritourism venture: A principal component analysis. Indian J. Ext. Educ. 2020, 56, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, H.; Park, D.-B. The role of agritourism farms’ characteristics on the performance: A case study of agritourism farm in South Korea. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2020, 23, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, A.; Tchetchik, A.; Bar-Nahum, Z.; Talev, E. Is agriculture important to agritourism? The agritourism attraction market in Israel. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2018, 45, 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosmann, M.; Hospers, G.-J.; Reiser, D. Searching for success factors of agritourism: The case of Kleve County (Germany). Eur. Countrys 2021, 13, 644–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionysopoulou, P. Agritourism entrepreneurship in Greece: Policy framework, inhibitory factors and a roadmap for further development. J. Sustain. Tour. Entrep. 2021, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, W.-T.; Ding, H.-Y.; Lin, S.-T. Determinants of performance for agritourism farms: An alternative approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandano, M.G.; Osti, L.; Pulina, M. An integrated demand and supply conceptual framework: Investigating agritourism services. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Luo, Q.; Ritchie, B.W. Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nguyen, T.H.H.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Coronavirus impacts on post-pandemic planned travel behaviours. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 102964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qiu, R.T.R.; Wen, L.; Song, H.; Liu, C. Has COVID-19 changed tourist destination choice? Ann. Tour. Res. 2023, 103, 103680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawęcki, N. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on agritourism. Ann. UMCS Geogr. Geol. Mineral. Petrogr. 2022, 77, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.L.; Musa, S.F.P.D. Agritourism resilience against COVID-19: Impacts and management strategies. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2021, 7, 1950290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poczta, J.M. The Covid-19 pandemic and the attitudes of consumers of agritourism farms towards health and physical activity. J. Educ. Health Sport 2023, 13, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M.M.; Jęczmyk, A.; Zawadka, J.; Uglis, J. Agritourism in the era of the coronavirus (COVID-19): A rapid assessment from Poland. Agriculture 2020, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, S.; Knollenberg, W.; Vilá, O. Agritourism resilience during the COVID-19 crisis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2023, 99, 103538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastronardi, L.; Cavallo, A.; Romagnoli, L. How did Italian diversified farms tackle Covid-19 pandemic first wave challenges? Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 82, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, B.; Verrascina, M.; Licciardo, F.; Gargano, G. Agritourism and farms diversification in Italy: What have we learnt from COVID-19? Land 2022, 11, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magno, F.; Cassia, F. Effects of agritourism businesses’ strategies to cope with the COVID-19 crisis: The key role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) behaviours. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 325, 129292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; AboAlkhair, A.M.; Fayyad, S.; Azazz, A.M.S. Post-COVID-19 family micro-business resources and agritourism performance: A two-mediated moderated quantitative-based model with a PLS-SEM data analysis method. Mathematics 2023, 11, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KC, B.; Morais, D.B.; Seekamp, E.; Smith, J.W.; Peterson, M.N. Bonding and bridging forms of social capital in wildlife tourism microentrepreneurship: An application of social network analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KC, B.; Morais, D.B.; Peterson, M.N.; Seekamp, E.; Smith, J.W. Social network analysis of wildlife tourism microentrepreneurial network. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, M.; Bernal, P.; Clarke, I.; Hernandez, I. The role of social networks in the inclusion of small-scale producers in agri-food developing clusters. Food Policy 2018, 77, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisomyong, N.; Meyer, D. Political economy of agritourism initiatives in Thailand. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 41, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akwii, E.; Kruszewski, S. Defining and Regulating Agritourism: Trends in State Agritourism Legislation 2019–2020. Center for Agriculture and Food Systems at Vermont Law School. 2021. Available online: https://www.vermontlaw.edu/sites/default/files/2021-04/Defining-and-Regulating-Agritourism.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Galluzzo, N. A quantitative analysis on Romanian rural areas, agritourism and the impacts of European Union’s financial subsidies. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streifeneder, T. Agriculture first: Assessing European policies and scientific typologies to define authentic agritourism and differentiate it from countryside tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsat, J.-B.; Menegazzi, P.; Monin, C.; Bonniot, A.; Bouchaud, M. Designing a regional policy of agrotourism—The case of Auvergne region (France). Eur. Countrys 2013, 5, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyukhina, N.A.; Parushina, N.V.; Chekulina, T.A.; Gubina, O.V.; Suchkova, N.A.; Maslova, O.L. Global trends and regional policy in agricultural tourism. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 839, 022054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, A.R.; Mishra, A.K.; Omobitan, O. Examining organic, agritourism, and agri-environmental diversification decisions of American farms: Are these decisions interlinked? Rev. Agric. Food Environ. Stud. 2019, 100, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-P.; Lee, K.-Y.; Kabre, P.M.; Hsieh, C.-M. Impacts of educational agritourism on students’ future career intentions: Evidence from agricultural exchange programs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dax, T.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y. Agritourism initiatives in the context of continuous out-migration: Comparative perspectives for the alps and Chinese mountain regions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montefrio, M.J.F.; Sin, H.L. Elite governance of agritourism in the Philippines. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1338–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubickova, M.; Campbell, J.M. The role of government in agro-tourism development: A top-down bottom-up approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 23, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peira, G.; Longo, D.; Pucciarelli, F.; Bonadonna, A. Rural tourism destination: The Ligurian farmers’ perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Greene, P.G.; Crick, A. Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 13, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 4, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, G.M. Social Psychology of Identity and the Self Concept; Surrey University Press: Surrey, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaderi, E.; Babaei, Y.; Akbari Arbatan, G.; Ferdowsi, S. Explaining the effect of entrepreneurship self-efficacy and innovation capability on the performance of tourism businesses (Tabriz as a case study). J. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 9, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R.; Assaker, G.; Lee, C. Tourism entrepreneurship performance: The effects of place identity, self-efficacy, and gender. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, M.S.; Ramli, A.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Muhammad, I.G. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy dimensions and higher education institution performance. Int. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 24, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Williams, K. Self-efficacy and performance in mathematics: Reciprocal determinism in 33 nations. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R.; Brown, G.; Lindsay, N.J. The Place Identity–Performance relationship among tourism entrepreneurs: A structural equation modelling analysis. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Noble, A.; Jung, D.; Ehrlich, S. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The development of a measure and its relationship to entrepreneurial action. In Frontiers for Entrepreneurship Research 1999; Reynolds, P.D., Bygrave, W.D., Manigart, S., Mason, C.M., Meyer, G.D., Sapienze, H.J., Shaver, K.G., Eds.; Babson College: Wellesley, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hallak, R.; Assaker, G.; O’Connor, P. Are family and nonfamily tourism businesses different? an examination of the entrepreneurial self-efficacy–entrepreneurial performance relationship. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 388–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Obschonka, M.; Schwarz, S.; Cohen, M.; Nielsen, I. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G. An agritourism systems model: A Weberian perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, N.F.; Belchior, R.; Costa, E.B. Exploring individual differences in the relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions: Evidence from Angola. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2020, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madawala, K.; Foroudi, P.; Palazzo, M. Exploring the role played by entrepreneurial self-efficacy among women entrepreneurs in tourism sector. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshmaram, M.; Shiri, N.; Shinnar, R.S.; Savari, M. Environmental support and entrepreneurial behavior among Iranian farmers: The mediating roles of social and human capital. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 58, 1064–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.; Kickul, J.; Marlino, D. Gender, entrepreneurial self–efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R.; Lindsay, N.J.; Brown, G. Examining the role of entrepreneurial experience and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on SMTE performance. Tour. Anal. 2011, 16, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florin, J.; Karri, R.; Rossiter, N. Fostering entrepreneurial drive in business education: An attitudinal approach. J. Manag. Educ. 2007, 31, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, A.J.; Withers, M.C.; Collins, B.J. Resource dependence theory: A review. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhüser, W. Resource dependence theory-how well does it explain behavior of organizations? Manag. Revenue 2008, 19, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drees, J.M.; Heugens, P.P. Synthesizing and extending resource dependence theory: A meta-analysis. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1666–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duignan, M.; Carlini, J.; McGillivray, D. Parasitic events and host destination resource dependence: Evidence from the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 30, 100796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Andersson, T. Festival stakeholders: Exploring relationships and dependency through a four-country comparison. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 34, 531–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Joo, D. Intermediary organizations as supporters of residents’ innovativeness and empowerment in community-based tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Zou, S.; Soulard, J. Transforming rural communities through tourism development: An examination of empowerment and disempowerment processes. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, A.; Minichilli, A.; Zattoni, A. Integrating agency and resource dependence theory: Firm profitability, industry regulation, and board task performance. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauniyar, S.; Awasthi, M.K.; Kapoor, S.; Mishra, A.K. Agritourism: Structured literature review and bibliometric analysis. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, S.R.; Komar, S.; Schilling, B.; Tomas, S.R.; Carleo, J.; Colucci, S.J. Meeting extension programming needs with technology: A case study of agritourism webinars. J. Ext. 2011, 49, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanina, A.; Konyshev, E.; Tsahaeva, K. Agritourism development model in digital economy. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Scientific Conference on Innovations in Digital Economy, St. Petersburg, Russia, 22–23 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mpiti, K.; De la Harpe, A. ICT factors affecting agritourism growth in rural communities of Lesotho. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2015, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Van Sandt, A.; Low, S.A.; Thilmany, D. Exploring regional patterns of agritourism in the U.S.: What’s driving clusters of enterprises? Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2018, 47, 592–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. Census of Agriculture. 2022. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/AgCensus/ (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- USDA Economic Research Service. Farm Structure and Contracting. 2024. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-structure-and-organization/farm-structure-and-contracting/ (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Schilling, B.J.; Attavanich, W.; Jin, Y. Does agritourism enhance farm profitability? J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2014, 39, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.W. The Texas agritourism act: Why the Texas legislature put farmer liability out to pasture. Oil Gas Nat. Resour. Energy J. 2017, 6, 685–724. [Google Scholar]

- Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code. Title 4. Liability in Tort Chapter 75A. Limited Liability for Agritourism Activities. 2015. Available online: https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/CP/pdf/CP.75A.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Lashmet, T.D. Texas Agritourism Act: Frequently Asked Questions. Texas A&M AgriLife Extension—Texas Agriculture Law Blog. 2016. Available online: https://agrilife.org/texasaglaw/files/2016/08/Agritourism-Act-FAQ.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Texas A & M Agrilife Extension Service. Agritourism Businesses. Available online: https://naturetourism.tamu.edu/agritourismbusinesses/ (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Dir. Program Eval. 1986, 30, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KC, B.; Dhungana, A.; Dangi, T.B. Tourism and the sustainable development goals: Stakeholders’ perspectives from Nepal. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KC, B.; Thapa, S. The power of homestay tourism in fighting social stigmas and inequities. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y. Exploring new opportunities for agritourism in the post-COVID-19 era. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Barbieri, C.; Seekamp, E. Social capital along wine trails: Spilling the wine to residents? Sustainability 2020, 12, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centner, T.J. Liability Concerns: Agritourism operators seek a defense against damages resulting from inherent risks. Kans. J. Law Public Policy 2009, 19, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, P.; Zhou, L. Place identity, social capital, and rural homestay entrepreneurship performance: The mediating effect of self-efficacy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Wall, G.; Liu, X. Government roles in stimulating tourism development: A case from Guangxi, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 16, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Xu, S.; Gil-Arroyo, C.; Rich, S.R. Agritourism, farm visit, or …? A branding assessment for recreation on farms. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 1094–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Arroyo, C.; Barbieri, C.; Rozier Rich, S. Defining agritourism: A comparative study of stakeholders’ perceptions in Missouri and North Carolina. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarpour, M.H.; Mohammadinejad, A.; Moghaddasi, R. Economics of agritourism development: An Iranian experience. Econ. J. Emerg. Mark. 2020, 12, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Identifier | Business Type | Gender | Age Category | Ethnicity | Income Level | Family Run | Area in Acres |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB01 | Flower Farm | Female | 50+ | White | USD 50,001–100,000 | Yes | 51–100 |

| AB02 | Nature Cabins | Female | 50+ | White | USD 200,001+ | Yes | >100 |

| AB03 | Apiary | Female | 50+ | White | USD 50,001–100,000 | Yes | 0–25 |

| AB04 | Winery | Male | 50+ | White | USD 200,001 | Yes | 0–25 |

| AB05 | Peach Farm | Male | 18–35 | White | N/A | Yes | >100 |

| AB06 | Lavender Farm | Female | 36–50 | White | USD 200,001+ | Yes | 0–25 |

| AB07 | U-pick Farm | Female | 50+ | White | USD 0–50,000 | Yes | 0–25 |

| AB08 | Vineyard | Female | 36–50, 50+ | Hispanic | USD 200,001+ | Yes | 51–100 |

| AB09 | Family Activity Farm | Male | 50+ | White | USD 200,001+ | Yes | 51–100 |

| AB10 | Christmas Tree Farm | Male | 50+ | White | USD 200,001+ | No | 26–50 |

| AB11 | U-pick Farm | Male | 50+ | White | N/A | Yes | 0–25 |

| AB12 | Winery | Female | 36–50 | White | USD 50,001–100,000 | Yes | 26–50 |

| AB13 | Flower Farm | Female | 36–50 | White | N/A | Yes | 51–100 |

| AB14 | Family Activity Farm | Male | 50+ | White | N/A | Yes | N/A |

| AB15 | Winery | Male | 50+ | White | USD 200,001+ | Yes | 26–50 |

| AB16 | Pecan Orchard | Male | 50+ | White | USD 0–50,000 | Yes | 0–25 |

| AB17 | Vineyard | Male | 50+ | White | USD 100,001–200,000 | Yes | >100 |

| AB18 | Hands-on Education Farm | Male | 50+ | White | N/A | Yes | 26–50 |

| AB19 | U-pick Farm | Male | 50+ | White | USD 50,001–100,000 | Yes | 0–25 |

| AB20 | Family Activity Farm | Female | 50+ | White | N/A | Yes | 51–100 |

| AB21 | Cattle Ranch | Male | 36–50 | White | USD 100,001–200,000 | Yes | 51–100 |

| AB22 | Wine Collective | Male | 36–50 | White | USD 200,001+ | Yes | 0–25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

KC, B.; Robbins, R.; Xu, S. A Pathway to Sustainable Agritourism: An Integration of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Resource Dependence Theories. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4911. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114911

KC B, Robbins R, Xu S. A Pathway to Sustainable Agritourism: An Integration of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Resource Dependence Theories. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4911. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114911

Chicago/Turabian StyleKC, Birendra, Robert Robbins, and Shuangyu Xu. 2025. "A Pathway to Sustainable Agritourism: An Integration of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Resource Dependence Theories" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4911. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114911

APA StyleKC, B., Robbins, R., & Xu, S. (2025). A Pathway to Sustainable Agritourism: An Integration of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Resource Dependence Theories. Sustainability, 17(11), 4911. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114911