Abstract

This study tested whether Information and Communication Technology (ICT) proficiency moderates the relationship between climate anxiety and specific expectations of future extreme weather events. Using survey data from 259 university students in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, we applied moderation analysis (Hayes PROCESS Model 1) and find a significant moderation (Int = 0.108, p = 0.030; ΔR2 = 1.8%). A Johnson–Neyman procedure indicated that climate anxiety reliably predicts risk expectations once ICTSkill is ≥3.99 (≈76.8% of the sample). By embedding ICT proficiency as a domain-specific perceived behavioural control construct, our results suggest that targeted digital literacy training can serve as a sustainability education tool, converting climate concern into informed preparedness.

1. Introduction

Climate change is a significant issue in the 21st century, profoundly impacting young adults. These individuals progressively turn to digital technologies to engage with their social and natural worlds and learn about global issues. Therefore, the relationship between ICT proficiency and public engagement with environmental challenges becomes an important topic of scientific research. Extant literature shows that ICT proficiency determines access to climate data and emotional and behavioural responses to environmental challenges [1].

Various relevant personal, social, and structural factors shape climate change perception and may vary widely [2]. While individuals can have increased general anxiety toward climate change, they still might not develop specific expectations of extreme weather events. In relevant research on environmentally responsible behaviour, two aspects are highlighted—internal factors (such as attitudes, emotions, and perceived control) and external ones (such as social norms and infrastructure) [3]. In this study, we integrate these internal and external factors to analyze whether the ICT proficiency of young adults moderates psychological concerns about climate change and the expectations of extreme climate events.

Drawing on Nolan’s organizational stage model of ICT adoption [4], we view ICT proficiency as a developmental continuum—from the basic awareness and acceptance of online resources to routine adoption, full integration into daily routines, and ultimately, strategic optimization—which in turn may influence how effectively climate-related emotions are translated into concrete risk expectations.

Sustainability scholarship addresses environmental threats and seeks effective communication and capacity-building strategies to convert general concerns into concrete sustainable improvements. For example, Burksiene and Dvorak [5] show how targeted e-communication by environmental NGOs can drive behaviour change toward sustainability goals. However, empirical evidence is scarce on whether ICT proficiency enables climate anxiety to be translated into concrete expectations of extreme events [2].

In this study, we analyze data from 259 business and economics university students in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to empirically test whether digital skills strengthen or weaken the link between climate anxiety and anticipating future climate impacts. This aim is accomplished by considering the following research questions:

- Research Question 1: Does ICT proficiency moderate the relationship between young adults’ climate anxiety and their expectations of extreme climate events?

- Research Question 2: If moderation exists, at what ICT skill threshold does the anxiety–expectation link become significant?

We selected Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H) to capture two neighbouring Adriatic-region contexts that differ significantly in their digital infrastructure development and sustainability policy maturity. By comparing an EU member state (Croatia) benefitting from substantial digital transformation funding with an accession candidate (BiH) facing greater resource constraints, we can identify how transitional and established European contexts might tailor digital skill interventions to improve young adults’ climate preparedness.

2. Theoretical Background

Risk expectations remain understudied despite growing work on digital skills and pro-environmental behaviour. We draw on three strands of the literature. First, environmental psychology argues that attitudes and emotions—climate anxiety included—are necessary but insufficient predictors of adaptive action [2,3]. Second, the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) states that the impact of attitudes is conditioned by perceived behavioural control [6]. ICT proficiency can be a control belief—confidence in one’s digital capabilities for finding, verifying, and acting on climate information, which should strengthen the attitude–outcome link. Third, ICT maturity frameworks describe how users progress from basic awareness to optimization, implying that higher-stage users are better equipped to integrate diverse data streams into forward-looking judgements [4].

2.1. Climate Change Perceptions and Psychological Concerns

Although our focal predictor measures digital skills, expectations of extreme climate events are fundamentally a cognitive-affective judgement. Psychology provides the tools to explain how people interpret, internalize, and act on information, even when that information arrives via digital channels. Psychological constructs—like risk perception and attitudes—determine whether and how digital content is attended to, trusted, and integrated into one’s worldview [2]. Many individuals, particularly young people, report higher levels of climate anxiety when faced with climate change and extreme climate-related events. This is also known as climate distress or eco-anxiety [1]. While traditional behavioural models initially assumed a simple cause-effect progression from knowledge to attitudes to pro-environmental activities, it became clear that heightened anxiety does not reliably predict constructive responses or accurate climate risk assessments [3].

There can be a range of different anxiety experiences, from limited distress to heightened feelings of vulnerability [7]. Moderate anxiety may motivate proactive behaviours like gathering information or taking preparatory action. However, if it becomes too intensive, individuals may feel overwhelmed, and their pro-environmental behaviour becomes unproductive [8]. The relationship of environmental concern and action does not need to evolve by following a direct or straightforward path, as it is influenced by multiple factors, including socioeconomic status (SES), the amount and quality of environmental information, self-efficacy, etc. [9]. The resulting capacity for pro-environmental behaviour will be affected if the enhanced climate anxiety disrupts any linkages.

2.2. Environmental Behaviour Models and Expectations of Extreme Climate Events

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) [6] is a robust framework for linking attitudes to behaviours in many different domains, including environmental contexts [10,11]. Fieldwork on risk perception shows that seeing and believing climate impacts motivate adaptation [7], while personal experience with extreme weather heightens concern [8]; at the same time, value-based models underline that pro-environmental action must cohere with moral beliefs about nature [9].

The TPB assumes that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control can predict behavioural intentions [6], which enables researchers to use the behavioural intentions as a proxy of future pro-environmental decisions [11]. Individuals with strong environmentalist values are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviours or maintain heightened expectations of climate risk [12]. Perceived behavioural control often interacts with external factors such as infrastructure or policy support, sometimes facilitating and sometimes impeding adaptation, as higher education’s mixed influence on sustainability illustrates [13]. Recent work indicates that climate concern motivates protective action only when self-efficacy is high [1]; without such efficacy, anxiety can lead to avoidance [14].

We considered alternative models—notably the Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) framework, which considers personal values and moral norms as the drivers of environmental behaviour [11]. Unfortunately, the VBN framework does not look at the role of skills to account for the issues of the availability of information to individuals concerned about the environment. On the other hand, the perceived behavioural control (PBC) construct of the TPB considers the motivation and capability of individuals as they form their expectations.

2.3. ICT Proficiency as a Moderating Factor

2.3.1. ICT Maturity and Digital Competencies

Articulated initially by Nolan [4] in the 1970s, the ICT maturity model describes a five-stage progression for organizations—from the initial awareness of computing capabilities, through acceptance and routine adoption, to full integration and optimization. The theoretical framework of ICT maturity can be adapted to individual behaviour [15], with different levels of ICT adoption: from awareness (acknowledging the existence of online climate information) to acceptance and adoption (as progressing stages of using online tools and information sources) and integration and optimization (which describe the regular patterns of everyday use, evolving toward the strategic application of ICTs and digital content to reach personal and collective goals).

Each stage reflects the frequency of use and the depth of competence: higher-stage users navigate complex data dashboards, critically evaluate conflicting claims, and employ digital platforms to co-create adaptation solutions [16,17,18]. A well-developed ICT maturity profile signals greater perceived behavioural control within the TPB—users confident in their digital skills feel empowered to seek out, verify, and act on climate forecasts and risk maps.

2.3.2. ICT Proficiency and Climate Anxiety

As previously discussed, ICT tools can provide individuals with timely data on extreme weather, greenhouse gas emissions, pollution, or local adaptation measures, to mention a few. However, digital platforms can also spread sensational or misleading narratives [17]. Individuals who lack robust digital skills may be more susceptible to misinformation, which inflates climate anxiety or undermines legitimate concerns [18]. In contrast, proficient users can find and use more comprehensive and evidence-based contexts. This ability to critically process complex information may help to ground climate anxiety within credible sources, thus fostering more substantial expectations of actual risks [19].

In empirical studies on young adults who rely on social media for climate news, it was found that they may have stronger emotional reactions [20]. Additionally, they only engage actively and constructively when they can filter out disinformation and interpret data in context [16].

High ICT proficiency also predicts richer forms of digital climate engagement—posting, debating, or curating content—rather than passive scrolling [21]. In short, digital competences dictate whether climate anxiety promotes informed understanding or perpetuates confusion through distorted risk judgements [22].

2.3.3. Climate Anxiety, ICT Proficiency, and Expectations of Extreme Climate Events

In the risk perception framework [22], individual beliefs concerning vulnerability influence one’s responses to perceived environmental hazards. When personal risk perceptions are integrated with the applicable environmental knowledge and relevant available resources, individuals are empowered to develop a realistic evaluation of specific future risks and develop appropriate coping strategies [23]. This finding was confirmed by Blennow et al. [7], who found that climate change beliefs can be linked to specific climate-driven issues.

The digital landscape is a significant source of climate-related perceptions, making ICT proficiency highly important for risk perception. Namely, individuals can be (self)trained, in the context of overall human competencies, to use digital competencies in preventing and combatting climate change [24].

In this research, moderation models are used. The advantage of these models is that a moderator variable changes the strength or direction of the relationship between two other variables [25]. In this context, ICT proficiency may change how climate anxiety affects the formation of expectations related to extreme climate events [1]. Higher ICT proficiency may help individuals translate emotional concerns into specific, evidence-based expectations. In comparison, lower ICT proficiency may lead to the denial or diffusion of climate anxiety as reliable information becomes less available [26].

This dynamic is especially evident among university students. They use digital technology to access climate data, connect with local or international environmental groups, and interact with international communities. Prior research confirms a clear link: young adults possessing strong digital literacy understand official climate reports better, engage more readily in climate activism, and are more likely to adapt their future career or lifestyle choices to anticipated climate conditions [27].

Since advanced digital literacy enhances information gathering, it paradoxically creates information overload. When information flow starts endangering one’s information processing capacity, anxiety escalates, particularly for individuals lacking self-efficacy or robust coping mechanisms [28,29]. Even if an individual has a high level of digital skills, their behavioural response will depend on a complex interplay of psychological and social factors [30].

ICT proficiency also holds significant positive potential. Strong digital skills can catalyze online engagement, streamline resource sharing, and build self-efficacy through collective action [20], as communities may use digital tools to self-organize and respond to immediate environmental threats. This collaborative dynamic offers a powerful pathway to transform diffuse anxiety into tangible preparedness, directing psychological distress toward more rational expectations regarding climate extremes [31].

In the Theory of Planned Behaviour, perceived behavioural control (PBC) reflects an individual’s belief in being able to execute a course of action [6]. ICT proficiency operationalizes this construct in the digital realm: students who can rapidly locate, verify, and visualize online climate data perceive fewer barriers to understanding risks, thereby raising PBC. From a social cognitive perspective, such mastery also functions as domain-specific self-efficacy—confidence to process and use information effectively [28]. Elevated self-efficacy, in turn, stimulates information-seeking behaviour, because individuals are more willing to invest effort when they believe that effort will pay off [15,21]. Skilled users, therefore, engage in deeper, multi-source searches, cross-checking official forecasts against crowdsourced updates and academic reports. This iterative information-seeking loop tempers sensational content and sharpens mental models of future climate extremes, providing a direct cognitive pathway from anxiety to concrete expectations. In short, ICT proficiency bridges psychological drivers (anxiety, PBC, self-efficacy) and risk cognition by enabling more effective, resilient online information-seeking patterns.

2.3.4. National Context(s) of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina

Significant national and regional differences in digital adoption can be related to varying ICT infrastructure, costs, and literacy programs [32]. Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina are no exceptions, as both countries are in a post-transitional region and face specific socioeconomic issues. Among university students, widespread mobile phone use contrasts sharply with considerable variations in critical digital literacy levels. These differences can be attributed to factors such as education policy, regional differences, and socioeconomic status [33].

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the level of digitalization across higher education institutions (HEIs) is relatively high, with the University of Mostar being one of the national benchmarks for the digital transformation of HEIs. In Croatia, HEIs have a much higher level of digitalization. This is predominantly due to support from the institutions and funds of the European Union. However, in both countries, there is an uneven distribution of ICT skills that could moderate the relationship between climate anxiety and the expected outcomes of climate change. This study aims to empirically evaluate the proposed theoretical relationship and develop targeted educational and policy interventions to enhance digital competencies.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Demographics

We deliberately surveyed students from business and economics programs because these future professionals will likely occupy decision-making roles in private and public sectors, where digital competence and climate risk awareness are significant factors. Using a convenience sample aligns our findings with the population likely to influence organizational changes and sustainability policies soon.

Data were collected via an online questionnaire, distributed to students of business and economics (60.4% of valid responses from Bachelor, 36.5% from Masters, and 3.1% from PhD students) in large, compulsory courses at public business schools across Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (University of Split, Dubrovnik, Osijek, Mostar, Sarajevo, Tuzla, Zenica, Banja Luka). After the listwise deletion of incomplete cases, N = 259 remained (see Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 for demographic information). Participation was anonymous and voluntary; consent was obtained before data collection. No private or personally identifiable data were collected.

Table 1.

Research sample.

Table 2.

Gender distribution of participants.

Table 3.

Participants’ socioeconomic status (SES).

3.2. Common Method Bias

We conducted a Harman single-factor test using principal axis factoring on all 20 survey items to evaluate whether common-method variance could inflate our results. The Total Variance Explained table shows that the unrotated first factor accounts for 43.75% of the total variance, well below the 50% benchmark recommended by Podsakoff et al. [34,35]. This indicates that a single latent source does not dominate item covariance. Thus, common-method bias is unlikely to pose a serious threat to the validity of our findings.

3.3. Measures

We used the following verified measures and scales:

- ICT proficiency (measured using a scale based on the general ICT adoption maturity model in organizations and loosely based on Nolan [4]): ICT awareness (level 1)—essential knowledge/understanding; ICT acceptance (level 2)—willingness to use; ICT adoption—actual usage (level 3); ICT integration (level 4)—incorporation into daily life; and ICT optimization—using ICTs to enhance quality of life (level 5).

- Psychological concerns over climate change (assessed using the Short Climate Change Anxiety Scale (CCAS-C), developed by Wu et al. [1]). Participants rated statements (e.g., “Thinking about climate change makes it difficult for me to sleep or concentrate”) on a conventional 5-item Likert scale.

- Expectations of climate change impacts (adapted from Blennow et al. [5] and Akerlof et al. [6]). These expectations refer to the participants’ expectations of extreme weather conditions such as extreme heat, droughts or floods, wildfires, personal losses due to climate change, negative climate impacts on the national economy, etc. Expectations are measured on a conventional 5-item Likert scale. The formulation was further adapted by Thiery et al. [36].

3.4. Conceptual Model

This study uses a simple moderation model where the variables are defined as follows:

- X (Independent Variable): Psychological concerns over climate change (CliCon).

- Y (Dependent Variable): Expectations of extreme climate events (CliExp).

- W (Moderator): Level of ICT proficiency (ICTSkill).

A conceptual model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual research model. Source: Authors.

4. Results

Data were analyzed using Hayes’ PROCESS macro V4.0 (Model 1, with 5000 bootstrap samples) to test whether ICT proficiency moderates the relationship between climate anxiety (X) and the expectations of extreme climate events (Y). A model summary is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Model summary.

The regression model produced an R2 value of 0.0530, while the mean square error (MSE) equals 0.7217. The overall model was statistically significant (F(3, 255) = 4.7519, p = 0.003), confirming that our predictors collectively explain 5.30% of the variance in the expectations of climate change impacts (CliExp). An analysis of the regression coefficients is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Statistical evaluation of predictors.

As presented in Table 5, when both CliCon and ICTSkill are 0, the expected value of the intercept (expected CliExp) is 4.033. The main effects of CliCon and ICTSkill were not statistically significant. However, the interaction term (CliCon × ICTSkill) was statistically significant (B = 0.1076, SE = 0.0493, t = 2.1819, p = 0.030). This moderation effect added 1.77% to the explained variance (F(1, 255) = 4.7608, p = 0.030), strengthening the assumption that ICT proficiency is a meaningful moderator.

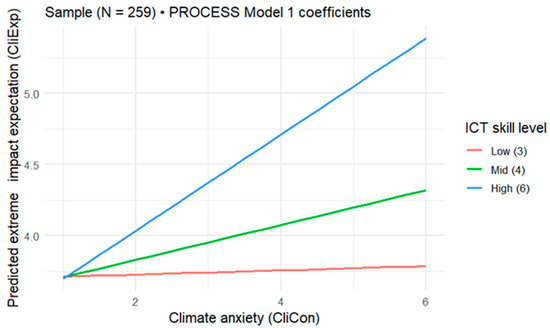

Probing the interaction (see details in Table 6) reveals how the impact of climate concerns (CliCon) on the expectations of extreme climate events (CliExp) varies with ICT skills (ICTSkill). Specifically, at low levels of ICTSkill (value = 3.0), CliCon showed only a small, non-significant effect on CliExp. The effect trended positive at moderate levels (value = 4.0) but remained non-significant. However, for individuals with high ICTSkill levels (value = 6.0), higher climate concerns were significantly associated with greater expectations of extreme climate events.

Table 6.

Statistical evaluation of moderation effect.

Figure 2 shows psychological concerns over climate change and the expectations of extreme climate events. Climate change (CliCon) is on the x-axis, and the expectations of extreme climate events (CliExp) are on the y-axis. The three lines shown in Figure 2 represent different levels of ICT proficiency: one for low proficiency (ICTSkill = 3.0), another for moderate proficiency (ICTSkill = 4.0), and a third for high proficiency (ICTSkill = 6.0).

Figure 2.

Visualization of moderation effect. Source: Results of empirical research.

Visually representing the interaction, the slope illustrating the relationship between climate concerns and expectations is nearly flat at low levels of ICT proficiency. This slope suggests that climate-related concerns do not significantly influence the expectations (CliExp) of extreme events in the population with lower digital skills. The Johnson–Neyman analysis, as reported by PROCESS Model 1, identified that the effects of climate concerns on the expectations of extreme climate events become significant when ICTSkill exceeds 3.9871. Approximately 76.83% of the sample scored above this threshold, indicating that the moderation is relevant for most of our sample.

5. Discussion

A central finding of our analysis is that the power of climate anxiety to shape expectations of extreme weather depends upon an individual′s ICT skills. While the direct effects of climate anxiety and ICT proficiency on risk expectation were not statistically significant, their interaction shows interesting dynamics. The significant, although modest (ΔR2 = 1.77%) interaction suggests that advanced digital literacy functions as a cognitive resource, enabling individuals to translate ‘fuzzy’ concerns about the climate into more clearly defined expectations of specific risks [16,21].

This finding suggests re-evaluating ‘personal experience’ as a core construct within environmental risk theory. Whereas this construct has traditionally been operationalized as a direct, sensory event [8], our conceptualization argues for expanding its definition to include the influence of an individual′s encounters with risk online. Our findings indicate that in a digital world, ICT proficiency may significantly shape the experience mediated by digital media and information.

This study addresses the psychological background of this process, as we show that ICT proficiency transforms abstract climate anxiety into tangible expectations of risk. We show that a mechanism, starting with the individual digital skills, can lead to the development of risk perception, translate the initial ′fuzzy′ feelings toward higher levels of adaptive capacity, and, ultimately, result in eventual civic action.

Our finding that ICT proficiency moderates the relationship between climate anxiety and risk expectation contributes to a body of extant literature, identifying digital literacy as a critical success factor for public engagement with climate change. For instance, in the United States, studies have empirically linked young adults’ digital engagement with their propensity for climate activism [16]. Focusing on a local context, extant research has shown that rural residents in Nevada with higher Internet skills also perceive higher levels of climate risk [26]. In other countries and regions, the practical value of digital skills has been also demonstrated for community-level climate adaptation in Central Asia [24].

Regarding the R2 in our model, it is evident that other factors, such as social norms, cultural attitudes, economic constraints, and trust in institutions, also play important roles in shaping these perceptions.

To build upon our current results, future research should pursue several approaches to improve the model′s explanatory power and robustness. First, future research should incorporate additional covariates known to influence environmental attitudes. Factors such as political ideology, socioeconomic status, gender, prior exposure to climate education, and direct experience with climate-related disasters could further explain the observed moderation effect.

Future empirical work might also focus on verifying the causality implied by our study. Non-linear relationships could be involved, which might be triggered by specific levels of ICT proficiency or by the nature of different components of online behaviour (e.g., information-seeking vs. information-processing).

We examine ICT skills as a moderating variable within an anxiety-expectation framework, especially in the under-researched context of (post)transitional economies and societies. The data from our South-East European sample identifies a specific inflection point (ICT Skill ≈ 3.99) where climate concern among young adults crystallizes into concrete expectations of future extreme weather. This specificity provides critical, actionable intelligence for designing digital literacy initiatives and sustainability programs across the European Union and its accession candidates [16,24,26].

Other empirical studies from the (post-)transitional countries in different European regions can confirm this fundamental insight. For example, Cvjetković et al. [37] show that Croatian SMEs’ integration of social media, guided by the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework, improved connectivity and sharpened the managerial anticipation of market risks and opportunities. In addition, Preidienė’s [38] research found that the shift from air travel to virtual meetings using platforms like Zoom for academic mobility in Baltic universities reshaped the staff′s perceptions of professional opportunities and logistical risks. These findings illustrate the linkages of ICT proficiency with the individual framing and foreseeing of external uncertainties. These studies demonstrate that, within both business and academic environments, advanced ICT capabilities consistently improve the transformation of psychological concerns into well-defined expectations. Therefore, our moderation findings could be considered relevant at the regional level.

The extant literature on technologically advanced societies, such as the Nordic region, indicates that educational interventions to improve ICT skills can influence public risk perceptions. The empirical evidence from a nationally representative survey in Norway shows that targeted communication of climate tipping points can influence public concern and the perceived seriousness of future risks [39]. However, the authors show that the limited influence of this effect is likely caused by the limited public understanding of climate science, which calls for consideration of potential learning barriers.

Based on a serious gaming intervention with policy-affiliated scientists and NGO representatives in Sweden, additional research produced mixed quantitative results concerning risk perception [40]. However, participants′ qualitative feedback showed deeper engagement and more vivid mental models of tipping scenarios.

In contrast, as digital literacy training in developing regions often concentrates on basic ICT skills, they tend to deliver only limited effects. Choudhary and Bansal’s [41] systematic review shows that courses in lower-income settings often prioritize basic skills, affecting critical evaluation or strategic data use. This further translates into minor improvements in participants’ ability to locate and assess climate information effectively.

The regional digital divides observed in this discussion are further supported by a recent bibliometric analysis of digitalization in Europe, which identified significant differences between Western and South-East European countries [32].

6. Conclusions

Among business and economics students in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, ICT proficiency modestly but significantly shapes how climate anxiety translates into expectations of extreme climate events. We found that students with stronger digital literacy better converted a general climate concern into concrete predictions of future weather extremes. This suggests that ICT proficiency plays a dual role: it can enhance climate risk awareness while also serving as a tool for closing the digital skills gap. This study, thus, offers the following theoretical contributions:

- We position ICT skills within the Theory of Planned Behaviour, treating them as a specific form of personal confidence. This helps explain how feelings of climate anxiety translate into specific future expectations.

- By connecting models of digital skill levels with theories of risk perception, we help clarify how ICT skills influence the ′mental processing′ of climate risks.

This study is not without its limitations, which the following future research tasks should address:

- Longitudinal designs could test causal sequencing: does building ICT proficiency over time strengthen the anxiety–expectation link?

- Additional moderators and mediators (e.g., political ideology, prior disaster experience, self-efficacy) should be examined to explain more of the variance in climate risk expectations.

- Cross-cultural comparisons in other regions would determine the generalizability of our moderation findings, and guide localized digital skill interventions.

- Our sample comprised solely business and economics students—future decision-makers with specific digital literacy training—so it remains unclear whether the observed ICT anxiety–expectation moderation holds among STEM majors, vocational-track students, or non-student young adults, who differ in digital skill profiles and climate anxiety.

- Future studies should compare the cohorts with different educational and socioeconomic characteristics—e.g., STEM vs. vocational students or non-student young adults—to determine how baseline digital literacy and climate anxiety profiles influence the observed moderation effect.

Finally, we identify a specific recommendation based on our findings. Given our results′ relatively small statistical effect, the following recommendation is intended as initial guidance rather than a definitive recommendation for implementing ICT policies and interventions. It should also be added that its efficiency needs to be further tested in different populations.

Our recommendation starts from an assumption of ICT proficiency intervention as central to translating general environmental concerns into specific action(s), as confirmed by this study and other empirical work in the extant literature. Therefore, improving digital literacy might be the key to unlocking higher levels of sustainability-aware education and social resilience to climate change.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17114840/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A. and M.M.K.; methodology, N.A.; software, N.A.; validation, Z.K.; formal analysis, N.A. and M.M.K.; investigation, N.A., M.M.K., and Z.K.; resources, N.A.; data curation, N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A., M.M.K., and Z.K.; writing—review and editing, M.M.K. and Z.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Council of the University of Mostar, Reg. No. 01-2041/255, 1 April 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are freely available in the Supplementary Materials of this man-uscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wu, J.; Long, D.; Hafez, N.; Maloney, J.; Lim, Y.; Samji, H. Development and validation of a youth climate anxiety scale for the Youth Development Instrument survey. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, R.L. Managing the computer resource: A stage hypothesis. Commun. ACM 1973, 16, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burksiene, V.; Dvorak, J. E-Communication of ENGO′s for Measurable Improvements for Sustainability. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blennow, K.; Persson, J.; Tome, M.; Hanewinkel, M. Climate change: Believing and seeing implies adapting. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, K.; Maibach, E.W.; Fitzgerald, D.; Cedeno, A.Y.; Neuman, A. Do people “personally experience” global warming, and if so how, and does it matter? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S. How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Inclusion with nature: The psychology of human-nature relations. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Schmuck, P., Schultz, W.P., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Incorporation and institutionalization of sustainable development into universities: Breaking through barriers to change. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, A.J.A.M.; van Dijk, J.A.G.M. The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media Soc. 2014, 16, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballew, M.T.; Marlon, J.R.; Kotcher, J.E.; Maibach, E.W.; Berquist, P.; Rosenthal, S.A.; Gustafson, A.; Goldber, M.H.; Mulcahy, K.; Swim, J.K.; et al. Young Adults, Across Party Lines, Are More Willing to Take Climate Action. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. 2019. Available online: https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/young-adults-climate-activism/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Wardle, C.; Derakhshan, H. Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy-making. Council of Europe report. Counc. Eur. 2017, 27, 1–109. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/information-disorder-toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework-for-researc/168076277c (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Scheufele, D.A.; Krause, N.M. Science audiences, misinformation, and fake news. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 7662–7669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.U. What shapes perceptions of climate change? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2010, 1, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O′Neill, S.; Nicholson-Cole, S. “Fear Won′t Do It”: Promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Sci. Commun. 2009, 30, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotti, F.; Donato, S.; Bussoletti, A.; Comunello, F. Youth activism for climate on and beyond social media: Insights from FridaysForFuture-Rome. Int. J. Press/Politics 2022, 27, 718–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. In Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brodskiy, V.A.; Grabova, O.N.; Ivanova, O.E.; Boboshko, V.I.; Boboshko, N.M. Competency-Based Approach to Primary Training of Young Digital Workforce in the Digital Economy as a Foundation for Combating Climate Change. In ESG Management of the Development of the Green Economy in Central Asia. Environmental Footprints and Eco-design of Products and Processes; Popkova, E.G., Sergi, B.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Safi, A.S.; Smith, W.J.; Liu, Z. Rural Nevada and climate change: Vulnerability, beliefs, and risk perception. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 1041–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eppler, M.J.; Mengis, J. The concept of information overload: A review of literature from organization science, accounting, marketing, MIS, and related disciplines. Inf. Soc. 2004, 20, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S. Psychology and climate change. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R992–R995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Iyer, S.; New, M.G.; Few, R.; Kuchimanchi, B.; Segnon, A.C. Interrogating’ effectiveness′ in climate change adaptation: 11 guiding principles for adaptation research and practice. Clim. Dev. 2022, 14, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deursen, A.; Helsper, E.J. A nuanced understanding of Internet use and non-use among the elderly. Eur. J. Commun. 2015, 30, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, N.; Żmija, K.; Roy, J.K.; Kusa, R.; Duda, J. Digital divide and digitalization in Europe: A bibliometric analysis. Equilibrium. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2024, 19, 463–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabić, M.; Praničević, D.G.; Gašpar, D. Toward Regional Development: Digital Transformation of Higher Education Institutions. Croat. Reg. Dev. J. 2022, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, W.; Lange, S.; Rogelj, J.; Schleussner, C.-F.; Gudmundsson, L.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Andrijevic, M.; Frieler, K.; Emanuel, K.; Geiger, T.; et al. Intergenerational inequities in exposure to climate extremes. Science 2021, 374, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvjetković, M. Organizational use and adoption of social media through TOE framework: Empirical research on Croatian small and medium-sized enterprises. Management 2022, 28, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preidienė, J. Flight ticket or Zoom meeting? Academic staff mobility in “old” and “new normality”. Management 2023, 28, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, C.; Milkoreit, M.; Hylland Eriksen, T.; Hessen, D.O. Missing the (tipping) point: The effect of information about climate tipping points on public risk perceptions in Norway. Earth Syst. Dynam. 2024, 15, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beek, L.; Milkoreit, M.; Prokopy, L.S.; Hylland Eriksen, T.; Hessen, D.O. The effects of serious gaming on risk perceptions of climate tipping points. Clim. Change 2022, 170, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, H.; Bansal, N. Addressing Digital Divide through Digital Literacy Training Programs: A Systematic Literature Review. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2022, 41, 224–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).