2. Perceptions of Urban Greening as a Climate–Health Strategy

Urbanization and climate change are intersecting forces that pose urgent challenges to public health, social equity, and environmental sustainability, particularly in densely populated urban centers. Climate-related hazards such as extreme heat, flooding, and deteriorating air quality disproportionately affect vulnerable urban communities, intensifying existing social and health inequalities [

1]. In this context, urban greening has emerged as a critical nature-based solution, offering the potential to enhance climate resilience, improve public health outcomes, and promote sustainable urban development [

2,

3].

Urban green spaces—such as parks, green corridors, and urban forests—not only mitigate environmental risks but also contribute to social well-being and psychological restoration [

4,

5]. Importantly, they have been shown to reduce preventable mortality in urban environments and support a wide range of environmental and economic benefits [

6,

7]. Recognizing their multi-dimensional value, urban greening initiatives are now central to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), notably SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

This study builds upon three theoretical frameworks: resilience thinking, nature-based solutions, and identity theory. Resilience thinking frames the urban environment as a dynamic system where social and ecological components must adapt together to withstand climate impacts. Nature-based solutions are operationalized in this study as practical interventions—such as urban greening—that simultaneously address environmental, social, and economic objectives. Identity theory informs our focus on how personal and collective environmental identities shape students’ engagement with sustainable practices. By integrating these frameworks, this study seeks to understand not only the perceived benefits of urban greening but also the psychological and behavioral mechanisms that drive or hinder proactive climate action among university students.

Despite growing research on urban sustainability and green infrastructure, a critical research gap remains; little is known about how young adults, particularly university students, perceive and engage with urban greening initiatives in relation to climate resilience and health. Existing studies have tended to focus on either environmental perceptions or health outcomes separately, without fully exploring their intersection through the lens of personal identity and action. This study addresses this gap by investigating how students’ climate–health awareness relates to their engagement in sustainable behaviors, and how universities can foster more active participation through identity-based educational strategies.

Accordingly, the primary research question guiding this study is “How do university students perceive the role of urban greening in climate resilience and public health, and what factors influence their engagement with sustainable practices?”

The structure of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a focused literature review on urban greening, climate resilience, and identity-based environmental engagement;

Section 3 outlines the methodology employed, including data collection and analytical techniques;

Section 4 details the results of the empirical analysis;

Section 5 discusses the findings in relation to existing literature, highlighting theoretical and practical implications.

Finally,

Section 6 concludes by summarizing the key contributions, managerial and societal impacts, study limitations, and directions for future research.

By clarifying the connections between theoretical frameworks, identifying a specific research gap, and articulating a clear research question, this study contributes to advancing both academic knowledge and practical strategies for sustainable urban development.

4. Materials and Methods

The methodology for this study centers on the development, administration, and analysis of a questionnaire in

Appendix A targeted at university students. The questionnaire was designed to gather insights into perceptions, experiences, and awareness related to urban greening, climate change, and its implications for public health. A structured questionnaire format was chosen to ensure consistency in responses and facilitate quantitative and qualitative data collection [

13].

The questionnaire consisted of three main sections: (1) demographic information, (2) perceptions of urban greening, and (3) opinions on the relationship between green spaces, climate adaptation, and public health. The questions included a mix of closed-ended items (e.g., Likert-scale and multiple-choice questions) and open-ended questions to capture nuanced perspectives [

1]. Items were informed by the ecosystem services framework, ensuring alignment with key theoretical constructs [

2]. The questionnaire was distributed via email and online survey platforms to reach a diverse population within the university community [

28].

In order to develop a detailed understanding of the attitudes, knowledge, and insights of a specific sub-group of the academic community, we specifically targeted the students enrolled in public health programs at higher education institutions. Thus, the study employed purposive sampling to target students (BSc, MSc, PhD) at the University of West Attica, Department of Public and Community Health. This sample has an educational foundation of ecology, sustainability, and public health. This approach ensured participants represented diverse perspectives and experiences related to urban greening and public health. Eligibility criteria included current enrollment at the university and a willingness to participate.

This study focused on university students, given their special role. Their education is still ongoing, and they are still shaping their knowledge. According to a well-established understanding, adolescence starts at puberty and ends with the uptake of mature social positions, such as child rearing and employment [

32]. The emergence of adulthood is considered to be the new life stage between adolescence and young adulthood [

33]. So, it could be said that their personality has not yet been fully established and can be considered fluid. The results of the study can be used for appropriate targeted future interventions. Discovering which perceptions are well informed according to contemporary science data, and which are not aligned, several interventions, such as awareness campaigns, may help to enlighten them promptly. At the same time, the results can reveal aspects of the curriculum that may need improvement or even bring forth the need for new approaches regarding the communication of science.

Also, given the fact that one day they will become society’s leaders, it is of great interest to measure their attitudes and perceptions. Universities, which are microcosms of society, can assess and improve social norms and identity-based involvement strategies. Students, due to their young age, could also be the first to encounter and adopt sustainability initiatives.

Figure 1 depicts the location of the campus of the Department of Public and Community Health within the Municipality of Athens, highlighting the limited access to greenery within the urban fabric. It should be mentioned that all the students live in different areas and visit the campus for the lectures. The image shows a satellite map of the Municipality of Athens, marked with a pin indicating the location of the Department of Public and Community Health, University of West Attica. The campus is situated in a densely built urban area, with minimal green spaces visible nearby. This visualization emphasizes the scarcity of greenery within the campus surroundings, reflecting the typical characteristics of highly urbanized environments, where natural spaces are significantly limited.

To maximize participation, the questionnaire was distributed through multiple channels and social media platforms. Respondents were informed about the study’s purpose, expected time commitment, and measures to ensure data confidentiality and anonymity [

13]. Consent was obtained through an online form preceding the questionnaire, adhering to ethical research standards [

2].

Data collection occurred over a four-week period between September and October 2024, during which reminders were sent weekly to encourage responses. A total of 620 responses were collected, of which 453 were complete and deemed usable for analysis. The remaining 167 responses were incomplete, and some were duplicates, so they were discarded. The 453 responses ensured sufficient representation of different demographic groups within the university [

1].

The data collection phase also included an optional open-ended section for respondents to provide additional comments or suggestions. This qualitative input offered valuable insights into individual experiences and perceptions, complementing the quantitative findings [

34].

The collected data were analyzed using both quantitative and qualitative methods to provide a comprehensive understanding of the findings. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics. To examine differences in participant responses across educational levels (undergraduate, postgraduate, and doctoral), a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed. This method is appropriate for comparing the means of a continuous dependent variable across three or more independent groups, allowing for the assessment of whether observed differences are statistically significant or attributable to random variation [

35].

For each ANOVA, the F-statistic, associated

p-value, and effect size were reported. The F-statistic represents the ratio of variance between groups to variance within groups, serving as an indicator of whether group means differ significantly. Effect sizes were calculated using eta squared (η

2), which quantifies the proportion of total variance in the dependent variable attributable to the independent variable. Eta squared is particularly informative in educational research contexts, providing insight into the practical significance of findings [

36]. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with a significance level set at α = 0.05. When significant effects were identified, post hoc analyses were conducted to determine specific group differences.

A total of 150 participants responded to the optional open-ended question. These qualitative responses were analyzed thematically using NVivo software. Through this process, key themes—such as barriers to accessing green spaces and suggestions for improving urban greening initiatives—were identified and systematically coded. The thematic analysis enriched the quantitative findings by offering deeper insights into individual experiences and contextual factors, helping to capture the complexity of perceptions related to urban sustainability [

28].

Data triangulation, combining quantitative and qualitative findings, ensured robustness and reliability. This mixed-methods approach facilitated a holistic interpretation of the results, aligning with the study’s objectives and theoretical framework [

3].

The ethical integrity of the study was maintained through adherence to established research guidelines. All participants were provided with detailed information about the study’s purpose, procedures, and confidentiality measures before giving informed consent. The anonymity of respondents was safeguarded by excluding personal identifiers from the dataset and ensuring secure data storage [

2,

13]. Moreover, the nature of the study posed minimal risk to the participants and all procedures regarding the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) were followed accordingly.

Limitations

While the questionnaire was designed to be comprehensive, certain limitations were unavoidable. The reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of social desirability bias, where respondents may provide answers they perceive as favorable rather than reflecting their true opinions [

1]. To mitigate this, the questionnaire included neutral phrasing and emphasized that there were no right or wrong answers.

Another limitation was the single-institution focus, which may affect the generalizability of the findings to other universities or populations. Hence, the results will be interpreted within the context of the specific population studied. Future studies could address this limitation by expanding the sample to include multiple institutions or regional contexts [

28].

Despite these challenges, the study provides valuable insights into university communities’ perceptions of urban greening, offering a foundation for further research and practical interventions in urban planning and public health [

3].

5. Results

The study sample comprised a total of 453 participants (n = 453). The gender distribution revealed a nearly balanced representation of the students, with 45% identifying as men, 54% as women, and 1% preferring not to disclose their gender identity. In terms of age, the majority of participants fell within the 18–34 age group, indicating a predominantly younger population. Academically, the sample was largely composed of undergraduate students, reflecting a focus on individuals at the early stages of their higher education journey. Detailed demographic characteristics are presented in

Figure 2. The study results reveal significant insights into the perceptions and attitudes of participants regarding climate change, urban greening, and their associated challenges. The findings underscore notable variations based on educational levels, shedding light on how academic exposure influences awareness and priorities.

The majority of participants expressed significant concern regarding the potential impacts of climate change on their personal health. Specifically, 45.7% of respondents reported being very concerned, while 30.5% were somewhat concerned.

A one-way ANOVA was performed to investigate whether academic level influences concern about the personal health impacts of climate change. The analysis showed a statistically significant difference across educational groups, F (2, 450) = 11.93, p < 0.001. The effect size was moderate (η2 = 0.050), indicating that 5% of the variance in health-related concern is explained by participants’ academic status.

To assess the impact of academic level on systemic concern related to climate-driven public health issues, a one-way ANOVA was conducted. The results indicated a statistically significant difference, F (2, 450) = 12.94, p < 0.001. The effect size was moderate (η2 = 0.054), suggesting that approximately 5.4% of the variance in systemic concern was explained by educational level. Postgraduate and doctoral students expressed greater concern for institutional and policy-level climate–health issues compared to undergraduates.

Undergraduate students demonstrated higher levels of concern for personal health impacts, likely due to their earlier exposure to climate-related educational initiatives and awareness campaigns. In contrast, postgraduate and doctoral students showed a stronger focus on systemic impacts, such as the broader implications for public health infrastructure and policies. This finding underscores the importance of targeted educational approaches at the undergraduate level to instill a foundational understanding of climate change’s immediate effects.

A notable 51.0% of respondents strongly agreed that universities should prioritize and encourage research on the health impacts of climate change. Academic level was found to significantly influence students’ agreement with integrating climate change into higher education curricula, as indicated by a one-way ANOVA, F (2, 450) = 24.00, p < 0.001. The effect size was large (η2 = 0.096), indicating that 9.6% of the variance in agreement scores was explained by academic status. Postgraduate (M = 4.66, SD = 0.52) and doctoral students (M = 4.70, SD = 0.73) reported significantly higher levels of agreement compared to undergraduate students (M = 4.12, SD = 0.93). These results suggest that higher education institutions should adapt research priorities to cater to different levels of academic progression, ensuring a robust pipeline for climate-related studies.

Two one-way ANOVAs were conducted to examine the influence of academic level on perceptions regarding the importance of applied research and investment in climate adaptation infrastructure. Results revealed statistically significant differences across educational levels in both domains. For applied research, postgraduate and doctoral students demonstrated significantly higher agreement levels (M = 4.60 and M = 4.55, respectively) compared to undergraduate students (M = 4.20), F (2, 450) = 13.13, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.055. Similarly, in the domain of policy investment, postgraduate and doctoral students again expressed greater support (M = 4.56 and M = 4.70, respectively) compared to undergraduate students (M = 4.23), F (2, 450) = 10.09, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.043.

Advanced students (MSc, PhD) emphasized the need for interdisciplinary and applied research, indicating their deeper understanding of the complexities involved. These results suggest that higher education institutions should adapt research priorities to cater to different levels of academic progression, ensuring a robust pipeline for climate-related studies.

Climate change is increasingly recognized as a driver of psychological distress and eco-anxiety, particularly among students. Approximately 60.9% of respondents strongly agreed that climate change negatively affects mental health, highlighting its perceived importance across all demographic groups (

Figure 3).

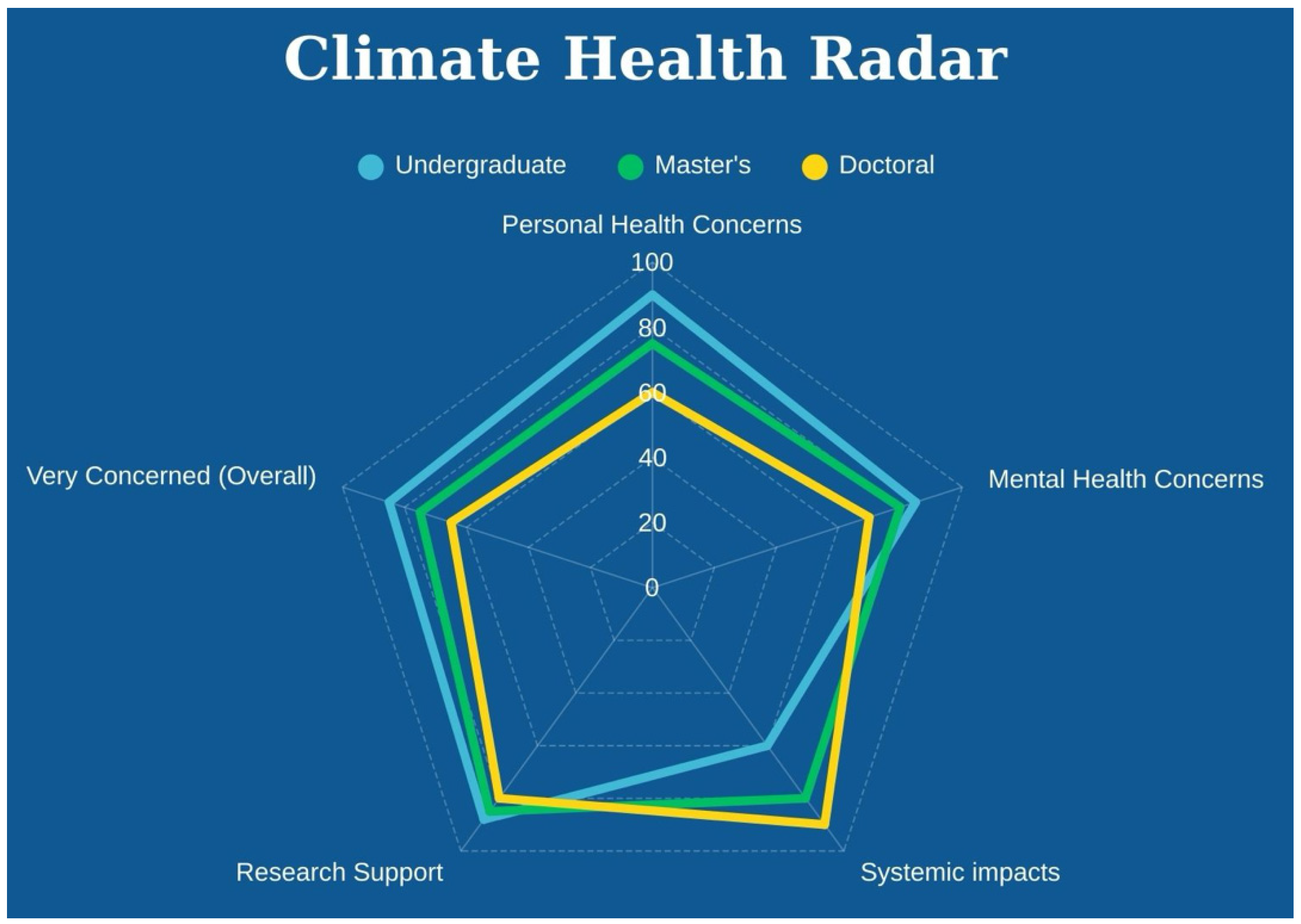

These trends are further visualized in the Climate Health Radar, which illustrates the variation in concern levels across educational stages regarding personal health, mental health, systemic impacts, and research support (

Figure 4). A series of one-way ANOVA tests revealed statistically significant differences in perceptions of climate-related mental health impacts across educational levels. Undergraduate students reported greater personal health-related concern (M = 4.02, SD = 0.92), whereas postgraduate (M = 4.44, SD = 0.73) and doctoral students (M = 4.45, SD = 1.09) demonstrated significantly higher levels of systemic concern, particularly regarding institutional disruption (M = 3.64 and M = 3.85 vs. M = 3.17), F (2, 450) = 10.24,

p < 0.001. Additionally, overall perceptions of mental health being affected by climate change also varied significantly by academic level, F (2, 450) = 5.69,

p = 0.004. The consistent recognition of this issue suggests the need for mental health initiatives that address both individual and systemic dimensions of climate stress.

Urban green spaces were widely recognized for their multifaceted benefits, with 56.5% of respondents strongly agreeing that green spaces enhance mental well-being and 48.3% strongly agreeing that such spaces promote physical activity. However, the perceived effectiveness of urban green spaces in mitigating urban heat island effects was mixed, with only 36.4% strongly agreeing on their impact. Undergraduate students exhibited stronger associations with direct personal benefits, including mental well-being (F (2, 450) = 11.70, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.049) and physical activity (F (2, 450) = 24.77, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.099). In contrast, postgraduate and doctoral students reported greater recognition of systemic benefits such as community cohesion (F (2, 450) = 5.09, p = 0.007, η2 = 0.022), environmental knowledge (F (2, 450) = 4.33, p = 0.014, η2 = 0.019), and the broader societal impact of personal climate actions (F (2, 450) = 7.77, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.033). These differences suggest the need for education programs that address both immediate and long-term benefits of urban greening initiatives.

A closer look at participants’ perceptions of urban green spaces, as illustrated in

Figure 5, provides further insights into the multifaceted value students attribute to greenery in urban environments. The most highly rated benefit was the enhancement of mental well-being, with an average agreement score of 4.4, reflecting the strong emotional and psychological association students make between access to green areas and personal relief from stress and anxiety. This aligns with broader literature on eco-therapy and the restorative functions of natural environments. The perceived improvement in air quality followed closely, with an average of 4.3, suggesting a clear understanding among students of the environmental health benefits tied to vegetation in urban settings. Physical activity promotion also ranked high (4.2), highlighting the role of green spaces in encouraging healthier lifestyle habits through accessible outdoor spaces. Interestingly, the benefit that received the lowest score was the reduction in the urban heat island effect, with a mean of 3.6. This may indicate a gap in awareness regarding the climate-mitigating functions of green infrastructure, suggesting that students recognize the immediate and personal benefits of urban greenery more than its broader ecological significance. The variation in scores across these categories emphasizes the need for more comprehensive education and communication strategies that frame urban greening not only as a public health asset but also as a critical component of climate resilience and urban sustainability.

Participants identified several key challenges in urban greening efforts. Funding issues were highlighted as the most significant barrier, with 49.7% rating them as strongly important, followed by urban development priorities (30.5%) and maintenance difficulties (27.2%). A one-way ANOVA revealed statistically significant differences in perceptions of both accessibility issues and infrastructure investment needs based on academic level.

Undergraduate students showed significantly greater concern with accessibility challenges (F (2, 450) = 3.67, p = 0.026, η2 = 0.016), whereas postgraduate and doctoral students emphasized the importance of systemic interventions, such as institutional investment in adaptation infrastructure (F (2, 450) = 10.09, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.043).

Despite these challenges, 51.0% of respondents strongly supported initiatives to create more urban green spaces, indicating a public inclination toward addressing these barriers.

To assess university students’ overall awareness and understanding of the health-related implications of climate change, we included four key Likert-scale questions in our survey:

“Are you concerned about the potential impacts of climate change on your personal health?”;

“Do you believe universities should encourage research on the impacts of climate change on health within higher education?”;

“I believe climate change can adversely affect the quality of education.”;

“Do you believe mental health is affected by the impacts of climate change?”.

Each question was rated on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely). While we did not construct a formal index in this study, the consistently high scores—most frequently above 4—highlight a strong awareness among students regarding the personal, educational, and psychological consequences of climate change (

Figure 6).

These findings illuminate a critical gap in current research: the absence of a dedicated Climate Health Assessment Index that could offer a numerical indication of how individuals perceive and relate climate change to health. The results of this study frame the basis for such a tool and underline the need for its development in future research. The high response rates and the alignment of participants’ views suggest that these variables could serve as predisposing factors, forming the conceptual foundation of a robust evaluative framework.

Such an index would allow for the systematic assessment of climate–health literacy and help identify patterns in awareness, concern, and behavioral intent. By assigning indicative values to these attitudes and perceptions, researchers could better explore the strength and clarity of the relationship between climate change and health concerns, particularly in academic environments. The data presented here point towards a promising direction for future empirical exploration, where this proposed index could support universities and policymakers in designing targeted, evidence-based educational interventions.

Overall, the findings demonstrate a clear need for targeted interventions that bridge the gap between awareness and action, particularly among undergraduate students. Addressing systemic barriers identified by advanced students, including funding and governance issues, is equally critical. A sustainable university is defined as a higher education institution (HEI) that actively addresses, involves, and promotes the minimization of negative environmental, economic, societal, and health impacts associated with the use of its resources. These efforts are aimed at supporting its functions—such as teaching, research, outreach, partnership, and stewardship—while aiding society in transitioning towards sustainable lifestyles [

37].

There are different aspects which must be taken into account when estimating the sustainability of higher education institutions, including climate change, biodiversity loss, and more. Accordingly, measures have been taken to transform them into tangible strategies and assessment tools for assessing HEI sustainability. This has been approached through international and national declarations the implementation of theoretical frameworks and assessment systems [

38]. As a result, measurable progress has been made towards sustainability development [

39].

For instance, some HEIs have incorporated relevant areas in the curriculums focused on green development and environmental sustainability [

40]. Additionally, many universities have implemented environmental management systems on their campuses, such as the ISO certificates and Eco Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) regulations [

41,

42].

Other examples include public announcements and policies towards sustainable goals [

43] and the implementation of dedicated conferences that discuss progress in HEI sustainability, such as those held by the Environment Management for Sustainability in Universities and the International Sustainable Campus Network (ISCN).

Promoting equitable access to green spaces and ensuring the distribution of benefits across diverse communities will be essential for fostering climate resilience and public health. By aligning educational initiatives with these insights, universities and policymakers can empower individuals to contribute actively to sustainable urban planning efforts.

Out of the 453 total participants, 150 provided responses to the optional open-ended question regarding urban greening. Thematic analysis conducted using NVivo software revealed several key themes, including perceived barriers to accessing green spaces, emotional and psychological benefits of greenery, and suggestions for improving urban greening initiatives.

Many participants highlighted the lack of accessible green spaces in their neighborhoods, citing issues such as poor maintenance, safety concerns, and overdevelopment. As one undergraduate student noted, “Even the few parks near my area are either locked or neglected. We need more green areas that feel safe and clean. Others emphasized the emotional relief that greenery provides, with comments such as “Being near trees or even small gardens helps me decompress after university stress.

In terms of recommendations, students commonly proposed the integration of small-scale greenery in urban infrastructure, such as green rooftops, vertical gardens, and tree-lined pedestrian zones. A postgraduate respondent suggested, “Universities should lead by example—why not install green roofs or student-maintained gardens on campus?

These qualitative insights enrich the quantitative findings by illustrating the lived experiences, challenges, and expectations of students about urban greening and mental well-being.

6. Discussion

This study highlights the complex and multifaceted relationship between climate change, urban greening, and health perceptions among university students, revealing critical nuances in how academic level influences environmental awareness, emotional responses, and engagement in sustainability practices. Over 75% of participants expressed concern about the direct and indirect health impacts of climate change, underscoring its recognition not only as a pressing environmental threat but also as a significant public health concern within academic communities.

Notably, the findings suggest that students’ level of academic engagement is associated with differing perspectives and degrees of concern. Undergraduate students reported higher levels of concern about climate–health impacts, which may reflect heightened emotional reactivity, perceived vulnerability, or more limited exposure to critical environmental discourses. This aligns with research indicating that younger individuals may experience stronger affective responses to climate risk, often manifesting as eco-anxiety or fear about the future. Conversely, postgraduate and doctoral students exhibited greater concern for the systemic dimensions of the climate crisis, including its implications for institutional functioning and the need for policy-level interventions. This trend suggests that academic maturity, research engagement, and critical thinking skills contribute to a more holistic understanding of environmental issues.

To explore these dynamics in greater depth, student responses to four key items were analyzed: personal health impacts, mental health, the role of universities, and educational quality. High average scores (often exceeding 4.0 on a 5-point scale) across these items indicate robust awareness and concern regarding how climate change affects both individual and collective well-being. However, despite strong awareness, a persistent action gap was evident. Students recognized the significance of the effect of climate change on health but reported limited engagement in sustainability-oriented behaviors. This discrepancy mirrors established findings in the literature on the knowledge-action gap [

44], emphasizing the need for more than cognitive awareness to drive behavioral change.

These findings reinforce the potential value of developing a dedicated Climate Health Assessment Indicator to quantitatively assess climate–health literacy and behavioral readiness. While existing tools such as the CDC’s BRACE framework and California’s Climate Change and Health Vulnerability Indicators focus on systemic vulnerabilities, the proposed index would capture subjective perceptions and emotional responses, providing a complementary approach to understanding climate resilience on an individual level. Such a tool could serve as an important instrument for universities and policymakers aiming to design interventions based on psychological and behavioral insights.

Urban green spaces were widely recognized for their positive effects on mental health, physical activity, and air quality. Participants identified mental well-being, physical activity promotion, and improved air quality as the top three benefits. However, their perceived efficacy in mitigating urban heat island effects was more limited, with only 36.4% strongly agreeing with their impact. Students also expressed concerns about accessibility and maintenance, often rating urban green infrastructure as only fair or good. More than half of the respondents reported minimal engagement in urban greening activities such as tree planting or park clean-ups, highlighting a tangible disconnect between awareness and action in environmental stewardship.

In terms of barriers, the challenges associated with urban greening were perceived as multifaceted and systemic. Funding was cited as the most significant barrier (with nearly 50% strongly endorsing this view), followed by competing urban development priorities, maintenance difficulties, and public resistance. Despite these obstacles, over 51% of participants expressed strong support for expanding green spaces, indicating an opportunity for universities and municipalities to harness public interest and implement inclusive, sustainable greening policies.

From a psychosocial lens, identity theory offers a valuable interpretive framework. Approximately 60.9% of respondents strongly agreed that climate change adversely affects mental health, suggesting a deep internalization of climate concern within students’ identities. Undergraduate students were more likely to frame climate change as a personal threat to mental well-being, often resulting in coping behaviors such as seeking refuge in campus green spaces or engaging in individual recycling efforts. These responses, while meaningful for self-regulation, may not translate into systemic change.

In contrast, postgraduate and doctoral students more frequently interpreted climate change through a collective lens. They conceptualized themselves as environmental advocates and active agents in broader societal change. This identity was reflected in their engagement with group-level actions, such as organizing awareness campaigns, community clean-ups, or participating in research addressing climate–health links. Their understanding of mental health encompassed both personal and collective dimensions, showing an appreciation for how environmental degradation, public health infrastructure, and social justice intersect.

These divergences in identity and behavioral orientation suggest the need for differentiated educational strategies. For undergraduate students, interventions should aim to shift the narrative from individual burden to collective agency. Universities could implement peer-led initiatives, interdisciplinary learning modules, or experiential education projects (e.g., ecological restoration, climate action simulations) to encourage shared responsibility and foster a sense of group efficacy. For postgraduate and doctoral students, institutions might support leadership development through grants, community engagement platforms, and research opportunities tied to climate advocacy and policy innovation.

This study also reveals that undergraduate students are more focused on immediate, tangible barriers to sustainability—such as the accessibility of green spaces—while more advanced students adopt a systems thinking approach. They emphasize the need for structural change, long-term planning, and policy integration. This shift likely reflects increased academic exposure to interdisciplinary frameworks, strategic analysis, and holistic sustainability thinking.

Importantly, the findings speak to broader societal imperatives, particularly in relation to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Student engagement with climate–health issues directly aligns with SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being) by addressing the mental and physical consequences of climate change. The expressed desire for expanded urban green spaces supports SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), while the focus on systemic behavior change and responsible action contributes to SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). By fostering climate–health literacy and enabling meaningful engagement, universities can become powerful catalysts for progress toward these global objectives.

Nonetheless, limitations should be acknowledged. The study was conducted within a single academic institution, which may limit generalizability across different educational or cultural contexts. Reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases, such as social desirability effects. Future research should employ longitudinal methods, behavioral metrics, and multi-site samples to more rigorously explore the evolving relationship between climate awareness, identity, and action.