Heritage-Based Evaluation Criteria for French Colonial Architecture on Le Loi Street, Hue, Vietnam

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Development of Evaluation Criteria for French Colonial Architecture in Hue

4.2. Le Loi “Western” Street and French Colonial Buildings

4.2.1. Construction History of Le Loi Street During the Colonial Era

4.2.2. Value of the French Colonial Buildings on Le Loi Street

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wright, G. The Politics of Design in French Colonial Urbanism; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.Q. Adaptive Conservation of Architectural and Urban Heritage from the French Colonial Period in Vietnam in the New Context. Tạp chí Kiến trúc (Archit. Mag.) 2023, 9. Available online: https://www.tapchikientruc.com.vn/chuyen-muc/bao-ton-thich-ung-di-san-kien-truc-va-do-thi-thoi-phap-thuoc-o-viet-nam-trong-boi-canh-moi.html (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Anh, K. The Risk of Erasure of Ancient French Villas in Hue. Công An Nhân Dân. 2018. Available online: https://cand.com.vn/doi-song/Nhung-ngoi-biet-thu-Phap-co-xua-o-Hue-truoc-nguy-co-bi-xoa-so-i460858/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Le, S.M. French Colonial Architecture in Hue. Tạp Chí Xây Dựng (J. Constr.) 2019, 3, 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Luong, P.L. French Colonial Architecture in Hue. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Architecture, University of Danang, Danang, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Du, L.T.H. The Integration of French Colonial Architecture with Hue’s Urban Attributes. Ph.D. Thesis, Hanoi University of Architecture, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Le, S.M. The Cross-cultural Identification, French—Vietnam Architecture, Case of French Colonial Constructions in Hue. Tạp chí Xây Dựng (J. Constr.) 2023, 1, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Nguyen, T.V.T.; Tran, H.T.T. Classification and Characteristics of Colonial Architecture in Hue City, Vietnam. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Sustainable Civil and Environment (SCE) 2022—Challenges to Sustainable Constructions and It’s Impact on the Environment, Malang, Indonesia, 3–4 October 2023; pp. 33–49, ISBN 978-623-175-210-9. [Google Scholar]

- Isa, F.; Al-Aggad, H.; Al-Quthami, L.; Wazna, N. The Architecture of Colonialism. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 10, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmund, Z. Sustainability in architectural heritage: Review of policies and practices. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. Int. J. 2016, 8, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.W.; Lai, L.W.; Chua, M.H. Post-colonial conservation of colonial built heritage in Hong Kong: A statistical analysis of historic building grading. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2022, 49, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter 1964). 1964. Available online: https://admin.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Venice_Charter_EN.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. The Charter of Krakow 2000: Principles for Conservation and Restoration of Built Heritage. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Conservation “Krakow 2000”, Krakow, Poland. 2000. Available online: https://icomosubih.ba/pdf/medjunarodni_dokumenti/2000%20Krakovska%20povelja.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Nara Document on Authenticity. In Proceedings of the Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention, Nara, Japan, 1–6 November 1994; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/nara94.htm (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, Including a Glossary of Definitions. Paris, France. 2011. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/160163 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Kalman, H. The Evaluation of Historic Buildings; Minister of the Environment: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1980; ISBN 0-662-10483-8. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. World Heritage Convention: The Criteria for Selection. UNESCO. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/criteria/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Department of Planning and Environment. Assessing Heritage Significance—Guideline for Assessing Places and Objects Against the Heritage Council of NSW Criteria; Environment and Heritage Group and Department of Planning and Environment: Parramatta, Australia, 2023; ISBN 978-1-923018-53-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gouvernement du Quebec. Heritage Value of Buildings and Heritage Sites; Gouvernement du Quebec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2023; ISBN 978-2-55094041-8. [Google Scholar]

- Protection Au Titre Des Monuments Historiques. Available online: https://www.culture.gouv.fr/Aides-demarches/protections-labels-et-appellations/protection-au-titre-des-monuments-historiques (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Li, D.; Wang, J.; Shi, K. Research on the Investigation and Value Evaluation of Historic Building Resources in Xi’an City. Buildings 2023, 13, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime Minister. Decree No. 85/2020/ND-CP Dated 17 July 2020 on Promulgating Detailed Articles of the Architectural Law. 2020. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Xay-dung-Do-thi/Nghi-dinh-85-2020-ND-CP-huong-dan-Luat-Kien-truc-447676.aspx?anchor=dieu_3 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Tran, B.Q. Developing an Evaluation Criteria System for French Colonial Architecture in Hanoi. Tạp chí Kiến trúc (Architecture Magazine) 2018. Available online: https://www.tapchikientruc.com.vn/chuyen-muc/xay-dung-thong-tieu-chi-danh-gia-di-san-kien-truc-phap-thuoc-o-ha-noi.html (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Nguyen, M.Q. French Townhouses in the Old Quarter (P2)—Values and Value Assessment of the Houses. Tạp chí Kiến trúc (Archit. Mag.) 2017, 12. Available online: https://www.tapchikientruc.com.vn/chuyen-muc/nha-pho-trong-khu-pho-co-p2-gia-tri-va-danh-gia-gia-tri-cac-ngoi-nha.html (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Doan, K.M. Evaluation Method for Heritage Villas in Hanoi. Tạp chí Kiến trúc (Archit. Mag.) 2020, 5, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, B.Q.; Thai, H.H.; Nguyen, Q.T. Establishing an Assessment Criteria System for Architectural Heritage of Colonial Educational Buildings in Hanoi. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 12, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People’s Committee of Ho Chi Minh City. Decision No. 33/2018/QD-UBND Dated 05 September 2018 on the Regulations for the Assessment and Classification of Old Villas in Ho Chi Minh City. 2018. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Bat-dong-san/Quyet-dinh-33-2018-QD-UBND-Quy-dinh-tieu-chi-danh-gia-va-phan-loai-biet-thu-cu-Ho-Chi-Minh-393803.aspx (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Nguyen, T.T. Potential for the Promotion, Renovation, and Development of Hue’s Architectural Heritage. In Hội Nghị Chuyên Gia “Đánh Giá Quỹ Kiến Trúc Đô Thị Huế” (Expert Conference on “Assessing Hue’s Urban Architectural Heritage”); Internal Proceedings; People’s Committee of Hue City: Hue, Vietnam, 2003; pp. 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Committee of Thua Thien Hue Province. Decision No. 1152/QD-UBND Dated 30 May 2018 on the Listing of Representative French Colonial Buildings in Hue City. 2018. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Xay-dung-Do-thi/Quyet-dinh-1152-QD-UBND-2018-danh-muc-thong-ke-cong-trinh-kien-truc-Phap-tieu-bieu-Hue-386627.aspx (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Nguyen, T.N.; Vo, P.G.T.; Phan, A.T.N.; Huynh, D.T.N.; Hoang, T.V. Formation Process of “Western” Street Architecture during the French Colonial Period in Hue. Univ. Da Nang—J. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, T.P. Chapter 6: Hue Capital in the Process of Becoming a Modern City. In Qua Sông Nhìn Lại Bến Bờ (Across the River Looking Back); Thuan Hoa Publishing House: Hue, Vietnam, 2005; pp. 226–244. [Google Scholar]

- Le, L.D. A Brief History of Vietnam. In An Introduction to Vietnam and Hue; Hue University and Thế Giới Publishers: Hue, Vietnam, 2002; pp. 123–156. [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw, S. Southeast Asia Emerges—A Concise History of Southeast Asia from its Origin to the Present; Diablo Press: Pleasant Hill, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, A.T.; Nguyen, T.Q. French Architecture Along the Perfume River. In Cố Đô Huế Xưa và Nay (Ancient and Modern Hue); Thuan Hoa Publishing House: Hue, Vietnam, 2005; pp. 580–588. [Google Scholar]

- Sogny, L.M. Rheinart, premier chargé d’affaires a Hué: Journal, notes et correspondence (M. Rheinart, First Chargé d’Affaires in Hue: Journal, Notes, and Correspondence). Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Hue (Bull. Friends Old Hue) 1943, 1–2, 1–248. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H.T. The Formation and Development History of the Western Quarter on the South Bank of the Perfume River (Hue) Before 1945. Bachelor’s Thesis, Faculty of History, University of Science, Hue University, Hue, Vietnam, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Doling, T. Exploring Hue Heritage of the Nguyễn Dynasty Heartland; Thế Giới Publishers: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Minh, T. Trường Tiền—Chuyện Chưa Kể Cây Cầu Lịch Sử (5 kỳ) (Trường Tiền—The Untold Story of the Historical Bridge (5 Parts)), Tuổi trẻ Newspaper. 2021. Available online: https://tuoitre.vn/truong-tien-chuyen-chua-ke-cay-cau-lich-su-ky-1-nhip-cau-noi-duong-thien-ly-2021080321280859.htm (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Phan, A.T. French Colonial Architecture. In Huế Xưa và Nay: Di tích—Thắng cảnh (Ancient and Modern Hue: Monuments and Scenic Sites); Van Hoa Thong Tin Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2008; pp. 249–284. [Google Scholar]

- Doumer, P. L’Indo-Chine Francaise (Souvenirs); Vuibert et Nony Editeurs: Paris, France, 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Le, H.N.M.; Nguyen, C.P.; Tran, H.T.T. French Style Mansion Located at 26 Le Loi: Architectural Situation and Preservation Solutions. Special Issue: Mathematics—Information Technology—Physics—Architecture. J. Sci. Technol. Univ. Sci. Hue Univ. 2024, 24, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, L.P. Hue Station During the Renovation Period 1986–2002. Bachelor’s Thesis, Faculty of History, University of Science, Hue University, Hue, Vietnam, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, T.D. French Architecture in the Ancient Capital of Hue: Status and Solutions for Sustainable Tourism Development. Bachelor’s Thesis, Faculty of History, University of Science, Hue University, Hue, Vietnam, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, B.N. Dictionary of Hue’s Cultural and Tourism Language; Thuan Hoa Publishing House: Hue, Vietnam, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.D. Colonial Architecture in Hue. In Hội Nghị Chuyên Gia “Đánh Giá Quỹ Kiến Trúc Đô Thị Huế” (Expert Conference on “Assessing Hue’s Urban Architectural Heritage”); Internal Proceedings; People’s Committee of Hue City: Hue, Vietnam, 2003; pp. 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Le, S.V.; Nguyen, T.Q.T. Sketch of Hue’s Urban Appearance in the First Half of the 20th Century. J. Sci. Technol. Inf. 1998, 4, 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bris, E.L. The War Memorial in Hue. Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Hue (Bull. Friends Old Hue) 1937, 24, 319–352. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, B.Q.; Nguyen, D.V.; Nguyen, M.T.; Ho, N. Architecture and Urban Planning in Colonial Hanoi; Construction Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.Q.; Ton, D.; Nguyen, M.Q.; Do, V.T. History of Vietnamese Architecture; Vietnam Association of Architects; Thanh Niên Publishers: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2020; pp. 258–317. [Google Scholar]

- Doan, K.M.; Bui, P.N.; Doan, T.M. Towards Developing the Smart Cultural Heritage Management of the French Colonial Villas in Hanoi, Vietnam. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. (IJSCET) 2021, 12, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, E. The Grammar of Architecture; Metro Book: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, A.L. Historical Dictionary of Neoclassical Art and Architecture, 2nd ed.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, M.F. Deco by the Bay—Art Deco Architecture in the San Francisco Bay Area. Viking Studio Books; Penguin Group: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

| General Criteria | Sub-Criteria | Suggested Score | Average Score of the Experts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal criteria | Historic value | 0–10 | 0–11 |

| Chronological value | 0–15 | 0–13 | |

| Cultural value | 0–10 | 0–11 | |

| Social value | 0–10 | 0–10 | |

| Architectural value | 0–15 | 0–15 | |

| Technology and construction condition | 0–10 | 0–10 | |

| External criteria | On-site value | 0–10 | 0–10 |

| Off-site value | 0–20 | 0–17 | |

| Other criteria | Feasibility for preservation; originality, new usage | 0 | 0–3 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average score | 77.1–100 | 54–77 | 26.9–53 | Under 24.3 |

| Selected score after rounding | 75–100 | 55–74 | 25–54 | Under 25 |

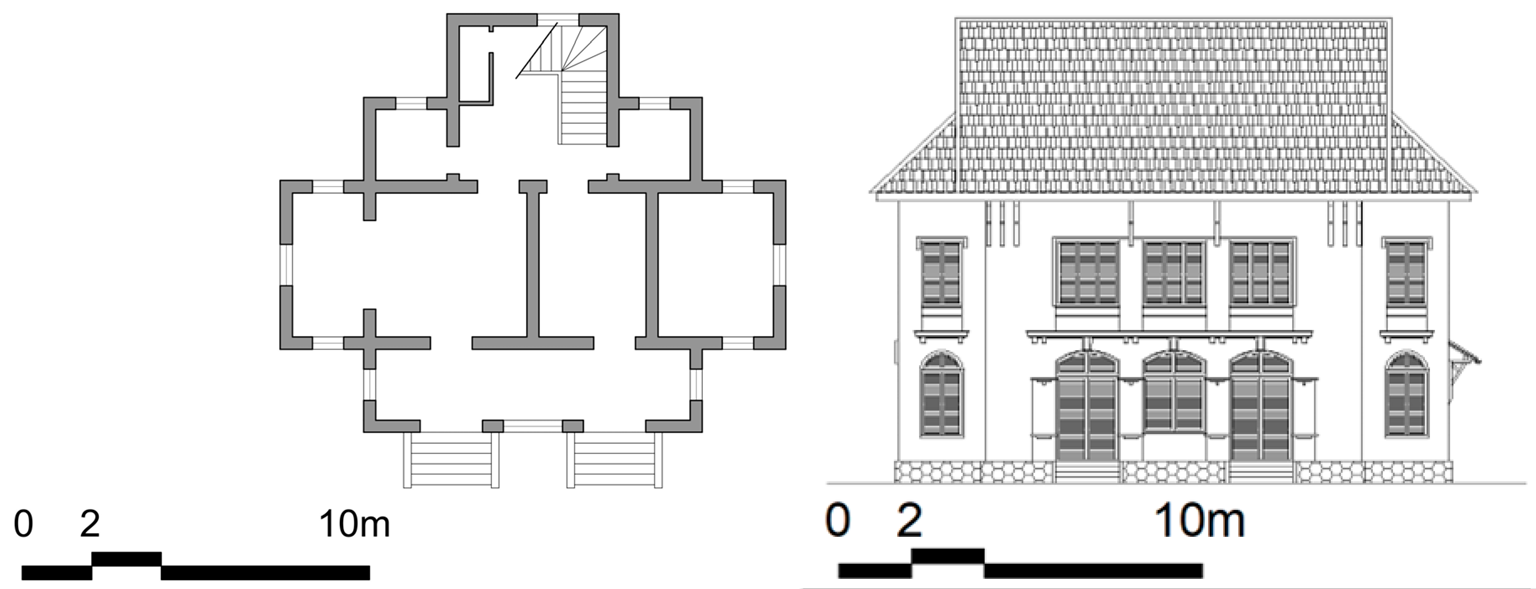

| ID | Name/Address/Google Coordinates | Building Date/Area (sq.m) and Number of Floors/Designer/Conditions | Drawing/Photos |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|  |

| 2 |

|

|  |

| 3 |

|

|  |

| 4 |

|

|  |

| 5 |

|

|  |

| 6.1 |

|

|  |

| 6.2 |

|

|  |

| 6.3 |

|

|  |

| 6.4 |

|

|  |

| 7.1 |

|

|  |

| 7.2 |

|

|  |

| 7.3 |

|

|  |

| 8.1 |

|

|  |

| 8.2 |

|

|  |

| 8.3 |

|

|  |

| 8.4 |

|

|  |

| 9 |

|

|  |

| 10 |

|

|  |

| 11.1 |

|

|  |

| 11.2 |

|

|  |

| 12 |

|

|  |

| 13 |

|

|  |

| 14 |

|

|  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, N.T.; Le, M.S.; Truong, H.P.; Nguyen, P.C. Heritage-Based Evaluation Criteria for French Colonial Architecture on Le Loi Street, Hue, Vietnam. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114753

Nguyen NT, Le MS, Truong HP, Nguyen PC. Heritage-Based Evaluation Criteria for French Colonial Architecture on Le Loi Street, Hue, Vietnam. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114753

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Ngoc Tung, Minh Son Le, Hoang Phuong Truong, and Phong Canh Nguyen. 2025. "Heritage-Based Evaluation Criteria for French Colonial Architecture on Le Loi Street, Hue, Vietnam" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114753

APA StyleNguyen, N. T., Le, M. S., Truong, H. P., & Nguyen, P. C. (2025). Heritage-Based Evaluation Criteria for French Colonial Architecture on Le Loi Street, Hue, Vietnam. Sustainability, 17(11), 4753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114753