Human Capital to Implement Corporate Sustainability Business Strategies for Common Good

Abstract

1. Introduction

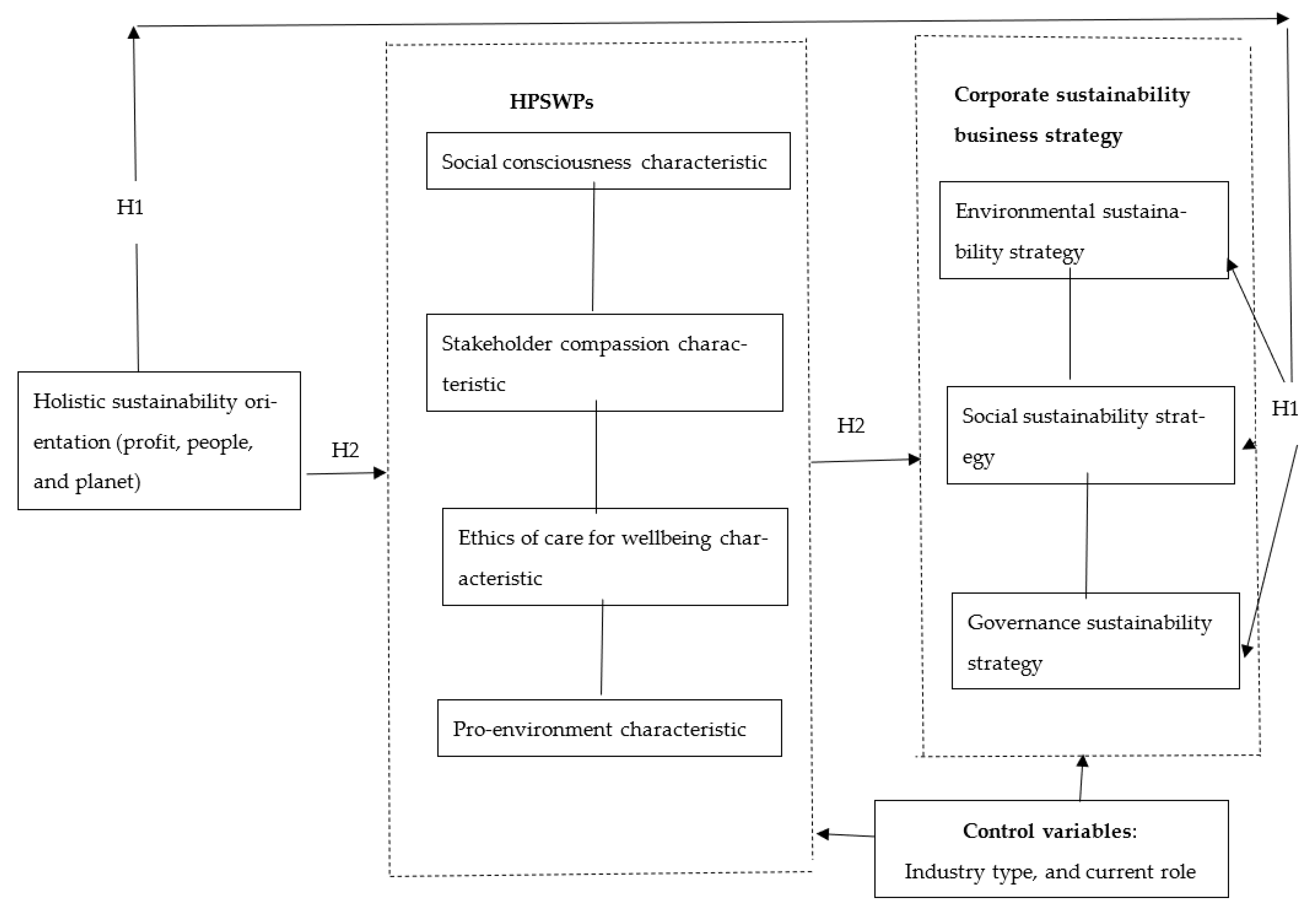

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Corporate Sustainability Business Strategy

2.2. Holistic Sustainability Orientation

2.3. Sustainable HRM System: Human Capital for ESG

2.4. High-Performance Sustainable Work Practices (HPSWPs)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Holistic Sustainability Orientation

3.2.2. Corporate Sustainability Business Strategy

3.2.3. High-Performance Sustainable Work Practices (HPSWPs)

3.2.4. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Models

4.3. Test of Hypotheses

5. Discussion

6. Limitation, Future Research, and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Holistic Sustainability Orientation Scale

| Item | EFA (N = 203)—Factor Loading | Rating Scale | ||

| 0.84 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 0.82 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 0.71 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 0.68 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 0.63 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

Appendix B. Corporate Sustainability Business Strategy Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- Scoring key:

- Environmental CS business strategy—Items 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 11, and 15 (7 items); Social CS business y strategy—Items 5, 9, and 13 (3 items); Governance CS business strategy—Items 3, 7, 10, 12, and 14 (5 items).

Appendix C. High-Performance Sustainable Work Practices (HPSWPs) Scale

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

- Scoring Key: Pro-environment (items 1 to 4); Stakeholder compassion (items 5 to 8); Ethics of care for wellbeing (items 9 to 11); Social consciousness (items 12 to 14).

- Mariappanadar, S. (2022) [13]. High Performance Sustainable Work Practices: Scale Development and Validation.

References

- Falegnami, A.; Romano, E.; Tomassi, A. The emergence of the GreenSCENT competence framework: A constructivist approach: The GreenSCENT theory. In The European Green Deal in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 204–216. [Google Scholar]

- Klettner, A.; Clarke, T.; Boersma, M. The governance of corporate sustainability: Empirical insights into the development, leadership and implementation of responsible business strategy. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. Sustainable Human Resource Management Strategies and Practices: Human Capital for Corporate Sustainability; Spinger Nature: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, R.; Shao, C.; Xin, S.; Lu, Z. A sustainable development evaluation framework for Chinese electricity enterprises based on SDG and ESG coupling. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, R.; Ali, H.; Mohamed, E.K. The Sustainable Development Goals and corporate sustainability performance: Mapping, extent and determinants. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khizar, H.M.U.; Iqbal, M.J.; Khalid, J.; Adomako, S. Addressing the conceptualization and measurement challenges of sustainability orientation: A systematic review and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 718–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions—Investigating the role of business experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, B.; Chadee, D. Environmental sustainability orientation and financial resources of small manufacturing firms in the Philippines. Soc. Responsib. J. 2012, 8, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, N.; Sebastianelli, R. Transparency among S&P 500 companies: An analysis of ESG disclosure scores. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1660–1680. [Google Scholar]

- Plastun, A.; Bouri, E.; Gupta, R.; Ji, Q. Price effects after one-day abnormal returns in developed and emerging markets: ESG versus traditional indices. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2022, 59, 101572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Lee, J.H.; Byun, R. Does ESG performance enhance firm value? Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRS–S1. General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-Related Financial Information. 2023. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/ifrs-sustainability-standards-navigator/ifrs-s1-general-requirements/#about (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Mariappanadar, S. High Performance Sustainable Work Practices: Scale Development and Validation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Child, J. Organizational structure, environment and performance: The role of strategic choice. Sociology 1972, 6, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatoglu, E.; Frynas, J.G.; Bayraktar, E.; Demirbag, M.; Sahadev, S.; Doh, J.; Koh, S.L. Why do emerging market firms engage in voluntary environmental management practices? A strategic choice perspective. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 31, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, E.M.; Ellemers, N. ESG indicators as organizational performance goals: Do rating agencies encourage a holistic approach? Sustainability 2020, 12, 10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Levialdi, N.; Menichini, T. Integrating sustainability into strategic decision-making: A fuzzy AHP method for the selection of relevant sustainability issues. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 139, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm: Fifteen Years After. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar]

- Mariappanadar, S. Characteristics of sustainable HRM system and practices for implementing corporate sustainability. In Sustainable Human Resource Management; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Wang, A.X.; Zhou, K.Z.; Jiang, W. Environmental strategy, institutional force, and innovation capability: A managerial cognition perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, Y.; Shao, J.; Lai, K.H.; Kang, M.; Park, Y. The impact of sustainability and operations orientations on sustainable supply management and the triple bottom line. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Lu, L.Y.; Tian, G.; Yu, Y. Business strategy and corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 162, 359–377.25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.B. Bringing strategy back in: Corporate sustainability and firm performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, 136012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Franco, M. Measuring the urban sustainable development in cities through a Composite Index: The case of Portugal. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engert, S.; Rauter, R.; Baumgartner, R.J. Exploring the integration of corporate sustainability into strategic management: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2833–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar S. Sharma, E.; Makhecha, U. Corporate Sustainability Business Scale. In Sustainable Human Resource Management Strategies and Practices: Human Capital for Corporate Sustainability; Mariappanadar, S., Ed.; Spinger Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridoux, F.; Stoelhorst, J.W. Stakeholder theory, strategy, and organization: Past, present, and future. Strateg. Organ. 2022, 20, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, J.; Chi, N. The antecedents and performance consequences of proactive environmental strategy: A meta-analytic review of national contingency. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2015, 11, 521–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Preuss, L.; Pinkse, J.; Figge, F. Cognitive frames in corporate sustainability: Managerial sensemaking with paradoxical and business case frames. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 463487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawinski, N.; Bansal, P. Short on time: Intertemporal tensions in business sustainability. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. Sustainable Human Resource Management: Strategies, Practices and Challenges; Macmillan International Publisher: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kramar, R. Sustainable human resource management: Six defining characteristics. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2022, 60, 146–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. Sustainable Human Resource Management: The Sustainable and unsustainable dilemmas of downsizing. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2003, 30, 906–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmi, P.; Kauhanen, A. Workplace innovations and employee outcomes: Evidence from Finland. Ind. Relat. A J. Econ. Soc. 2008, 47, 430–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littig, B.; Griessler, E. Social sustainability: A catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, C.; Dabu, A. Human resources, human resource management, and the competitive advantage of firms: Toward a more comprehensive model of causal linkages. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L.H.; Lepak, D.P.; Schneider, B. Employee attributions of the “why” of HR practices: Their effects on employee attitudes and behaviors, and customer satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2008, 61, 503–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Schuler, R.S.; Jiang, K. An aspirational framework for strategic human resource management. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.; Liu, Y.; Hall, A.; Ketchen, D. How much do high-performance work practices matter? A meta-analysis of their effects on organizational performance. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 59, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S.; Kramar, R. Sustainable HRM: The Synthesis Effect of High Performance Work Systems on Organisational Performance and Employee Harm. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2014, 6, 206–224. [Google Scholar]

- Makhecha, U.P.; Mariappanadar, S. High-performance sustainable work practices for corporate ESG outcomes: Sustainable HRM perspective. NHRD Netw. J. 2023, 16, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C. Upper echelons theory: An update. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiVito, L.; Bohnsack, R. Entrepreneurial orientation and its effect on sustainability decision tradeoffs: The case of sustainable fashion firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, B.; Coetzer, A. Institutional environment, managerial attitudes and environmental sustainability orientation of small firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakala, H. Strategic orientations in management literature: Three approaches to understanding the interaction between market, technology, entrepreneurial and learning orientations. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.C. Sustainability orientation, green supplier involvement, and green innovation performance: Evidence from diversifying green entrants. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 161, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 3rd ed.; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, B.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, T.; Figge, F.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L. A paradox perspective on corporate sustainability: Descriptive, instrumental, and normative aspects. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byggeth, S.; Hochschorner, E. Handling trade-offs in ecodesign tools for sustainable product development and procurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.; Purcell, J. Strategy and Human Resource Management, 4th ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.K.; Oh, W.Y.; Messersmith, J.G. Translating corporate social performance into financial performance: Exploring the moderating role of high-performance work practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 3738–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, E.; Bailey, T.; Berg, P.; Kalleberg, A.L.; Bailey, T.A. Manufacturing Advantage: Why High Performance Work Systems Pay Off; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfleisch, A.; Malter, A.J.; Ganesan, S.; Moorman, C. Cross-sectional versus longitudinal survey research: Concepts, findings, and guidelines. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS graphics: A road less travelled. Struct. Equ. Model. 2004, 11, 272–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.97 | 0.88 | ||||||||||

| 3.79 | 1.22 | 0.05 | |||||||||

| 2.39 | 0.46 | −0.13 | −0.29 ** | ||||||||

| 2.16 | 0.55 | −0.11 | −0.14 | 0.28 ** | |||||||

| 2.22 | 0.49 | −0.08 | −0.02 | 0.32 ** | 0.59 ** | ||||||

| 2.09 | 0.60 | −0.28 ** | −0.12 | 0.37 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.56 ** | |||||

| 1.65 | 0.82 | −0.24 ** | −0.09 | 0.53 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.42 ** | ||||

| 2.83 | 0.63 | −0.13 * | −0.09 | 0.45 ** | 0.36 *** | 0.39 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.59 ** | |||

| 3.49 | 0.52 | 0.18 * | 0.10 | −0.16 * | 0.05 | 0.19 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.11 | ||

| 2.89 | 0.62 | −0.16 * | −0.03 | 0.50 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.08 |

| Models | χ2 (df) | GFI | CFI | TLI | IFI | RMSEA | χ2 diff | dfdiff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full measurement model, eight factors | 760 (428) | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.05 | ||

| Model A, seven factors (HSO and SC combined into a single factor) | 907 (436) | 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.07 | 132 | 11 *** |

| Model B, seven factors (HSO and StCom combined into a single factor) | 897 (436) | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.06 | 141 | 11 *** |

| Model C, seven factors (HSO and ECW combined into a single factor) | 901 (436) | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.08 | 129 | 11 *** |

| Model D, seven factors (HSO and PE combined into a single factor) | 1002 (436) | 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 122 | 11 *** |

| Model E, six factors (three CSBS dimensions combined into a single factor) | 843 (443) | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.05 | 73 | 14 *** |

| Model F, five factors (four dimensions of HPSWPs combined into a single factor) | 981 (448) | 0.82 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.06 | 210 | 19 *** |

| Model G, five factors (CSBS dimensions and SC combined into a single factor) | 829 (452) | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.05 | 58 | 21 *** |

| Model H, five factors (CSBS dimensions and StCom combined into a single factor) | 1003 (452) | 0.82 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.06 | 232 | 21 *** |

| Model I, five factors (CSBS dimensions and ECW combined into a single factor) | 993 (452) | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.06 | 222 | 21 *** |

| Model J, five factors (CSBS dimensions and PE combined into a single factor) | 1348 (452) | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 577 | 21 *** |

| Model K, four factors (HSO and four dimensions of HPSWPs are combined into a single factor) | 1427 (456) | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.08 | 346 | 22 *** |

| Model L, one factor (all variables combined into a single factor) | 2626 (462) | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.14 | 1246 | 28 *** |

| CS Business Strategy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Sustainability Strategy | Social Sustainability Strategy | Governance Sustainability Strategy | ||||

| Predictor 1 | Direct Effect Est. (SE) 2 | Mediation Effect Est. (SE) 3 | Direct Effect Est. (SE) 4 | Mediation Effect Est. (SE) 5 | Direct Effect Est. (SE) 6 | Mediation Effect Est. (SE) 7 |

| Holistic sustainability orientation of firms (profit, people, and planet) | 0.61 *** (0.09) | 0.67 * (0.32) | −0.13 ** (0.09) | −0.17 * (0.09) | 0.70 *** (0.09) | 0.58 *** (0.09) |

| Social consciousness characteristics of HPSWP | 0.41 (0.26) | 0.10 (0.07) | 0.34 *** (0.07) | |||

| F | 17.28 | 14.11 | 3.67 | 3.32 | 24.33 | 27.04 |

| R2 | 0.21 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.05 ** | 0.06 * | 0.27 *** | 0.35 *** |

| Stakeholder compassion characteristics of HPSWP | 0.0.36 *** (0.08) | 0.29 *** (0.08) | 0.37 *** (0.08) | |||

| F | 18.90 | 6.54 | 25.36 | |||

| R2 | 0.28 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.34 *** | |||

| Ethics of care for wellbeing characteristics of HPSWP | 0.32 *** (0.07) | 0.34 *** (0.06) | 0.29 *** (0.07) | |||

| F | 19.63 | 10.76 | 24.52 | |||

| R2 | 0.28 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.33 *** | |||

| Pro-environment characteristics of HPSWP | 0.39 *** (0.05) | −0.09 (05) | 0.37 *** (0.05) | |||

| F | 29.97 | 3.55 | 36.67 | |||

| R2 | 0.38 *** | 0.07 ** | 0.43 *** | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mariappanadar, S. Human Capital to Implement Corporate Sustainability Business Strategies for Common Good. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4559. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104559

Mariappanadar S. Human Capital to Implement Corporate Sustainability Business Strategies for Common Good. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4559. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104559

Chicago/Turabian StyleMariappanadar, Sugumar. 2025. "Human Capital to Implement Corporate Sustainability Business Strategies for Common Good" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4559. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104559

APA StyleMariappanadar, S. (2025). Human Capital to Implement Corporate Sustainability Business Strategies for Common Good. Sustainability, 17(10), 4559. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104559