A Methodology for Identifying Critical Success Factors and Performance Measurement for Sustainable Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

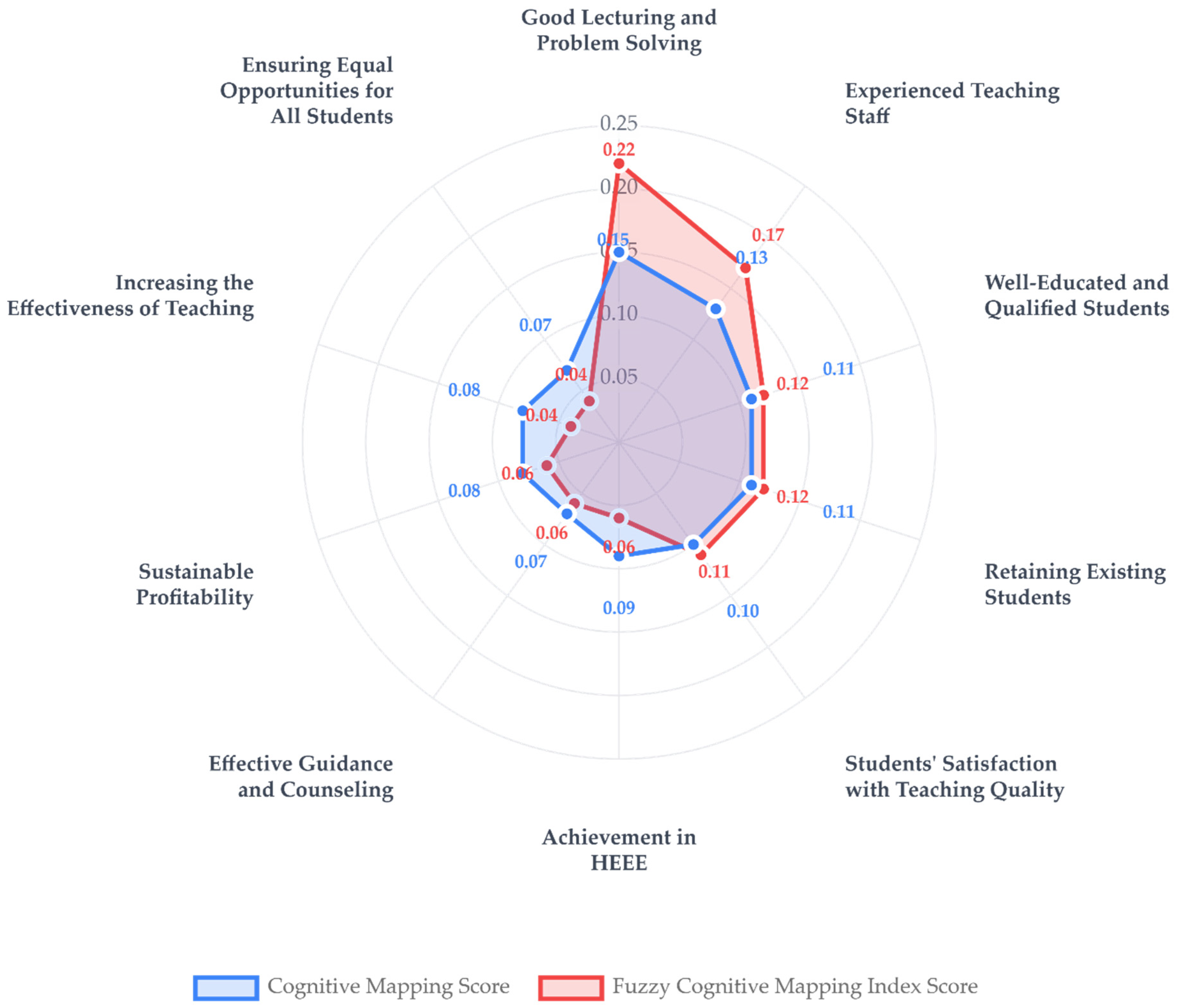

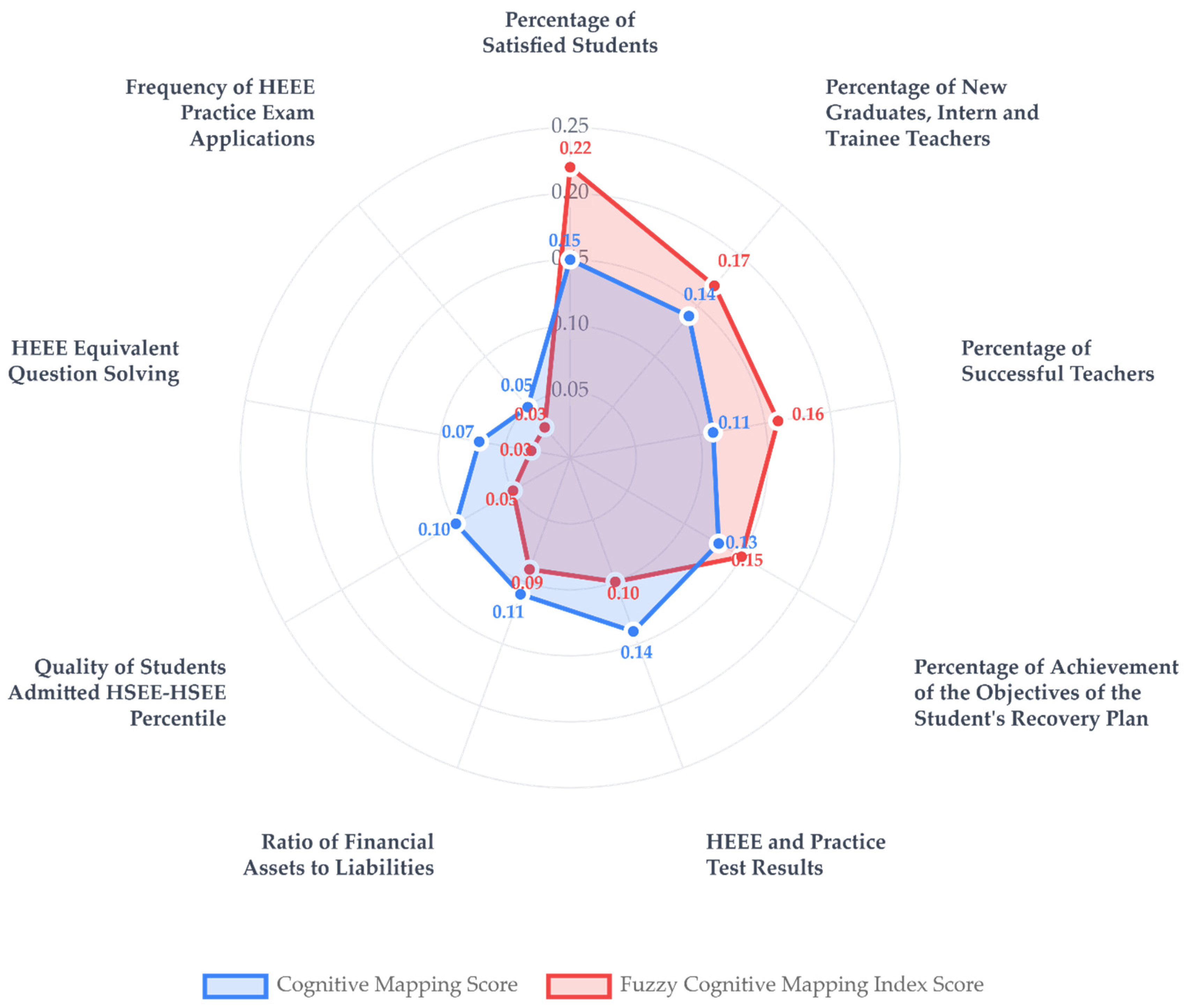

- What are the CSFs and KPIs for schools?

- What are the SWOT factors for schools?

- Can a school-specific BSC be developed and implemented?

2. Materials and Methods

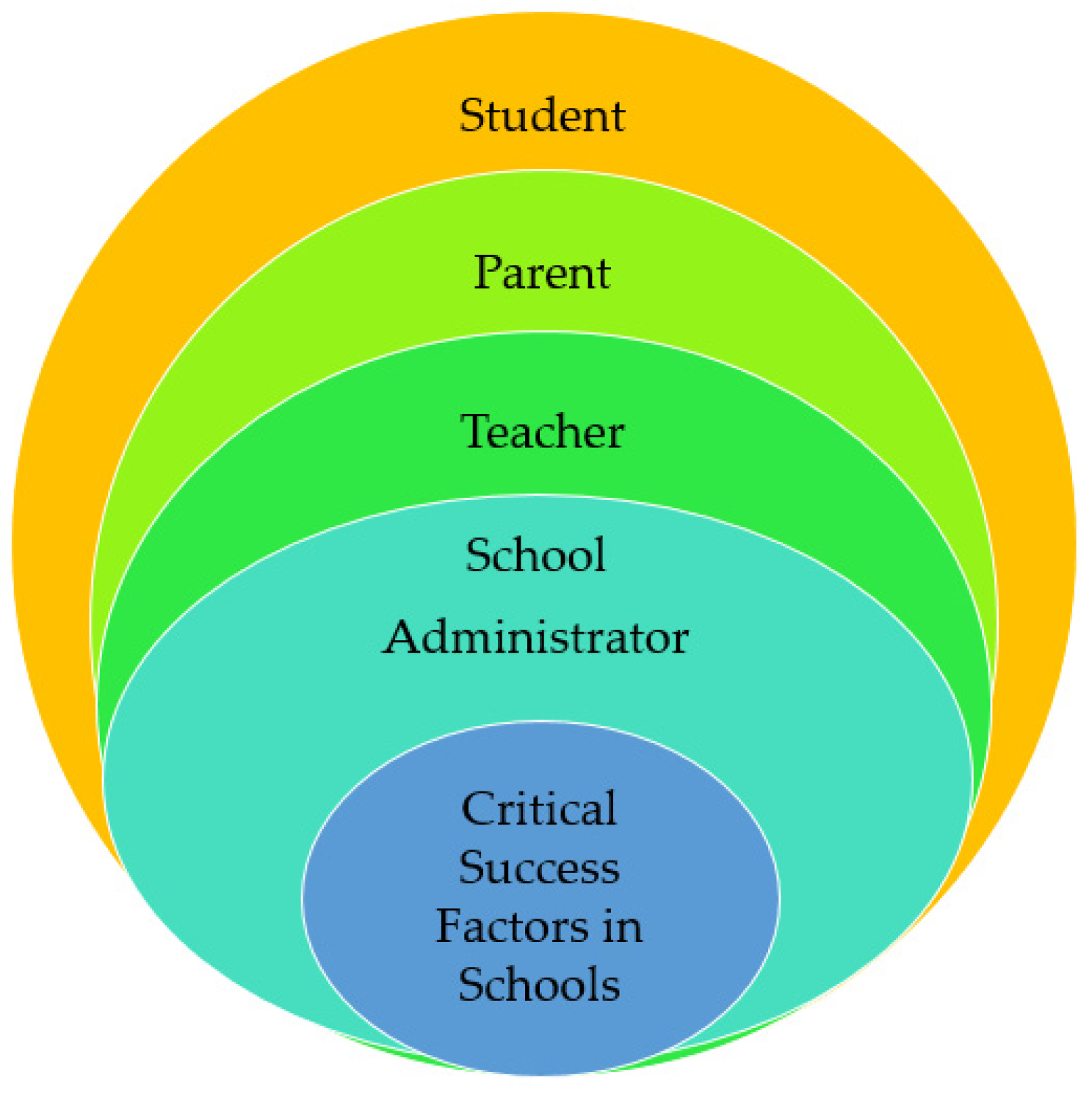

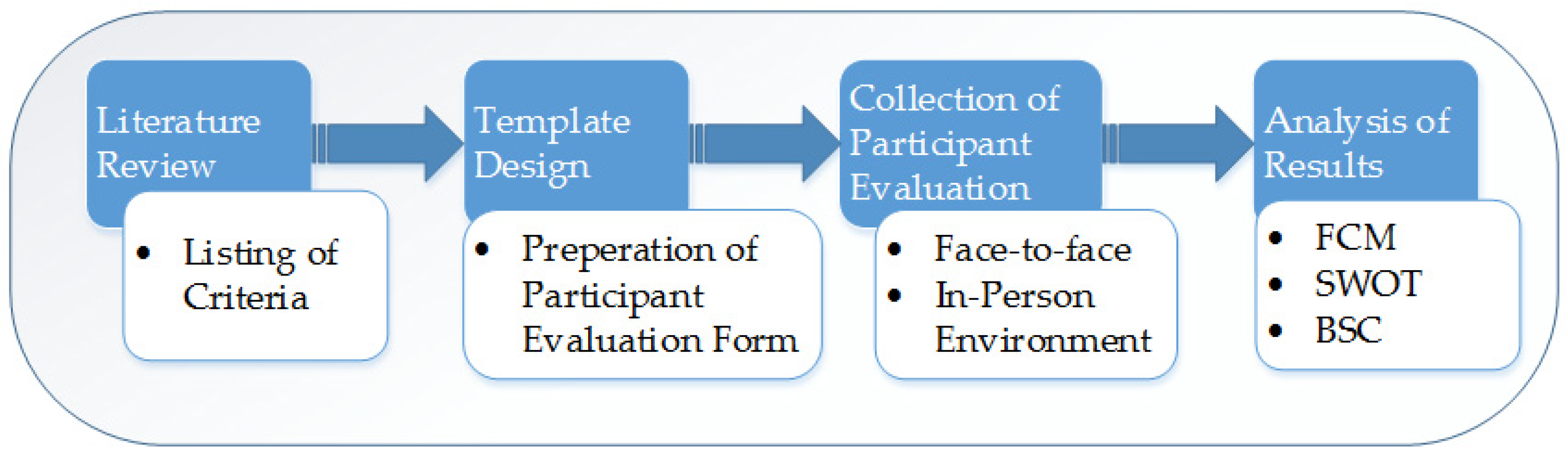

2.1. Conceptual Design

- Identification of CSFs for schools using the FCM method;

- Determination of SWOT factors specific to schools;

- Development of a BSC model for schools, based on the factors identified in the first two phases.

2.2. Methods

- Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping:

- SWOT Analysis:

- Strengths: A resource or capability related to stakeholders’ perspectives on the school.

- Weaknesses: A limitation or deficiency related to stakeholders’ perspectives on the school.

- Opportunities: A favorable condition or unmet need related to stakeholders’ perspectives on the school.

- Threats: A potential obstacle or constraint that may cause problems.

- Balanced Scorecard Approach:

3. An Actual Evaluation

3.1. Steps of Methodology

3.2. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions and Future Studies

- What are CSFs and KPIs for schools? We firstly identified 19 different CSFs and KPIs that influence the success of schools through literature research, participant evaluations, and statistical analyses.

- What are the SWOT factors for schools? We have identified 50 CSFs and KPIs for schools as a result of literature research and identified the 18 most important ones through participant evaluations and statistical analyses.

- Can a school-specific BSC be developed and implemented? We developed a performance measurement system with school-specific objectives and measurement criteria and implemented it in four schools.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSFs | Critical Success Factors |

| KPIs | Key Performance Indicators |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| BSC | Balanced Scorecard |

| FCM | Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping |

| CM | Cognitive Mapping |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats |

| HEEE | Higher Education Entrance Exam |

| HSEE | High School Entrance Exam |

| PISA | Programme for International Student Assessment |

| TIMSS | Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study |

| BAHS | Beşiktaş Anatolian High School |

| CAHS | Cağaloğlu Anatolian High School |

| SETHS | Selçuk Technical High School |

| SUTHS | Sultanahmet Technical High School |

References

- Gunduz, M.; Almuajebh, M. Critical success factors for sustainable construction project management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multan, E.; Wójcik-Augustyniak, M.; Sobotka, B.; Bis, J. Application of performance and efficiency indicators in measuring the level of success of public universities in Poland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, A.; Kamal, Y.; Amin, S.U.; Khan, S. Critical success factors in information technology projects. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2017, 7, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, V.; Jung, J. Revitalizing educational institutions through customer focus. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2024, 52, 1323–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, R.; Khourshed, N.; Wahba, M.; Bary, A.-A.-E. Exploring critical success factors for public private partnership case study: The educational sector in Egypt. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulminskaya, A. “Success Formula”: Factors of educational success/failure in the assessments of Russian schoolchildren. In INTED2021 Proceedings; IATED: Seville, Spain, 2021; pp. 8318–8323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.Y.; Rajkhan, A.A. E-learning critical success factors during the covid-19 pandemic: A comprehensive analysis of e-learning managerial perspectives. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, C.M.; Karrenbauer, C.; Breitner, M.-H. Critical success factors and challenges for individual digital study assistants in higher education: A mixed methods analysis. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 28, 4475–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmeron, J.L. Augmented fuzzy cognitive maps for modelling LMS critical success factors. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2009, 22, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, I.; Robertson, S. Understanding project sociology by modeling stakeholders. IEEE Softw. 2004, 21, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.S.; Mohamed, S. Mediation Effect of Stakeholder Management between Stakeholder Characteristics and Project Performance. J. Eng. Proj. Prod. Manag. 2021, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sayın, A.; Gelbal, S. Scaling the importance levels of factors affecting success using the successive intervals method. Amasya Univ. J. Fac. Educ. 2014, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, K.; Celik, M. The views of teachers and school administrators on effective school. J. Turk. Educ. Sci. 2023, 21, 260–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titrek, O.; Delioglan, M.; Ipekli, N. Effective school research in Turkey: Content analysis of articles (2000–2020). Bartın Univ. J. Fac. Educ. 2021, 10, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockart, J.F. Chief executives define their own data needs. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1979, 57, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-repiso, L.; Sethchi, R.; Salmeron, J.L. Modelling IT projects success with fuzzy cognitive maps. Expert Syst. Appl. 2007, 32, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuMoeilak, L.; AlQuraidi, A.; AlZarooni, A.; Beheiry, S. Critical success factors for building information modeling implementation as a sustainable construction practice in the UAE. Buildings 2023, 13, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasebotsa, A.R.; Agumba, J.N.; Adebowale, O.J.; Edwards, D.J.; Posillico, J. A Critical Success Factors Framework for the Improved Delivery of Social Infrastructure Projects in South Africa. Buildings 2024, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kineber, A.F.; Oke, A.; Aliu, J.; Hamed, M.M.; Oputu, E. Exploring the adoption of cyber (digital) technology for sustainable construction: A structural equation modeling of critical success factors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, M.H.; Ali, M. Assessment of Critical Success Factors for Building Projects through the Literature. Eng. Proc. 2023, 53, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, D.R. Management information crisis. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1961, 39, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, M.T. Critical Success Factors Simplified: Implementing the Powerful Drivers of Dramatic Business Improvement; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sezer, N. Critical Success Factors. Available online: https://neslihansezerblog.com/2018/02/23/kritik-basari-faktorleri/ (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Muhedaner, M.; Maihemuti, S. College students online education evaluation through SWOT analysis during COVİD-19. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 88371–88385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cıkmaz, E.; Kılıç, B. SWOT analysis in educational institutions: The example of universities in Turkey. Int. J. Discip. Econ. Adm. Sci. Stud. 2023, 9, 1239–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peris-Ortiz, M.; García-Hurtado, D.; Devece, C. Influence of the balanced scorecard on the science and innovation performance of Latin American universities. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 17, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hladchenko, M. Balanced Scorecard—A strategic management system of the higher education institution. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2015, 29, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokcam, A.H.; Kubat, C. A model for measuring school performance. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Innovative Technologies in Engineering and Science (ISITES 2015), Valencia, Spain, 3–5 June 2015; pp. 465–471. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M.M.; Filipe Melão, N. The implementation of the balanced scorecard in a school district: Lessons learned from an action research study. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2012, 61, 919–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus Alvares Mendes Junior, I.; Alves, M.-D.-C. The balanced scorecard in the education sector: A literature review. Cogent Educ. 2022, 10, 2160120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, Y.; Kasap, S.S. Organizational Performance: A National Literature Review. Kocaeli Univ. J. Sci. 2021, 4, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meechang, K.; Watanabe, K. Modeling to achieve area business continuity management implementation via a fuzzy cognitive map. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhagar, C. Role of fuzzy cognitive maps in smart education system. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th MEC International Conference on Big Data and Smart City (ICBDSC), Muscat, Oman, 15–16 January 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, A.; Nizaeva, M. Strategic Performance Management Using the Balanced Scorecard in Educational Institutions. Open Educ. Stud. 2023, 5, 20220198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohrabi, A.; Manteghi, N. A proposed model for strategic planning in educational organizations. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 28, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, D. Balanced Scorecard, SWOT Analysis and Application in Strategic Management. Alanya Acad. Rev. J. 2021, 5, 1181–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, Y.K.; Koo, L.C. BSQ strategic formulation framework: A hybrid of balanced scorecard, SWOT analysis and quality function deployment. Manag. Audit. J. 2004, 19, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glykas, M. Fuzzy cognitive strategic maps in business process performance measurement. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.F.; Sai On Ko, A. Building balanced scorecard with SWOT analysis, and implementing “Sun Tzu’s The Art of Business Management Strategies” on QFD methodology. Manag. Audit. J. 2000, 15, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manteghi, N.; Zohrabi, A. A proposed comprehensive framework for formulating strategy: A Hybrid of balanced scorecard, SWOT analysis, porter‘s generic strategies and Fuzzy quality function deployment. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 2068–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keok, C.B.; Thong, L.K. Work in progress-integrating bos, swot analysis, balanced scorecard and outcome-based framework for strategy formulation of engineering school. In Proceedings of the 2007 37th Annual Frontiers In Education Conference-Global Engineering: Knowledge Without Borders, Opportunities Without Passports, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 10–13 October 2007; p. S4F-13-S4F-14. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2022 Results (Volume I and II)—Country Notes: Türkiye. 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/pisa-2022-results-volume-i-and-ii-country-notes_ed6fbcc5-en/turkiye_d67e6c05-en.html (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Sarıer, Y. Turkey’s Performance in PISA Applications and Variables Predictive of Student Success. Turk. J. Soc. Res. 2021, 25, 905–926. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Türkiye Ministry of National Education. 2023–2024 Education Statistics Announced. 2023. Available online: https://www.meb.gov.tr/2023-2024-egitim-ogretim-istatistikleri-aciklandi/haber/34977/tr (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Nunes, C.; Oliveira, T.; Santini, F.-D.-O.; Castelli, M.; Cruz-Jesus, F. A weight and meta-analysis on the academic achievement of high school students. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Guidelines for the Use of the SDG Logo. 2023. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/SDG_Guidelines_AUG_2019_Final.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2024. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/indicators-list/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- United Nations. UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2023. UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/ (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Alenezi, M.; Alanazi, F. Integrating environmental social and governance values into higher education curriculum. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2024, 13, 3493–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, S.; Krishnamoorthy, K.; Kayani, U.; Kayani, F.; Hasan, F. Sustainable investing: ESG effectiveness and market value in OECD regions. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2025, 13, 2445147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Türkiye Ministry of National Education. PISA Results Show That Türkiye Has Consistently İncreased İts Success in the 20-Year Period. 2022. Available online: https://www.meb.gov.tr/pisa-results-show-that-turkiye-has-consistently-increased-its-success-in-the-20-year-period/haber/31839/en (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Kleemola, K.; Hyytinen, H. Exploring the Relationship between Law Students’ Prior Performance and Academic Achievement at University. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.K.; Kiguel, S.; Porter, S.C.; Easton, J.Q. Who benefits from attending effective high schools? J. Labor Econ. 2024, 42, 717–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eranıl, A.K. School Dropout Causes in Turkish Education System (2009–2022): A Pareto Analysis by Grade Level. J. Theor. Educ. Sci. 2024, 17, 451–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozan, M.B.; Polat, H.; Gunduzalp, S.; Yaras, Z. SWOT analysis in educational institutions. Turk. J. Educ. Stud. 2015, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cobbold, I.; Lawrie, G. The development of the balanced scorecard as a strategic management tool. Perform. Meas. Assoc. 2002, 35, 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cavlak, H. The Relationship Between Key Performance Indicators And Critical Success Factors: An Airline Company Application. Marmara Univ. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2021, 43, 78–99. [Google Scholar]

- Groumpos, P.P. Modelling business and management systems using fuzzy cognitive maps: A critical overview. IFAC-Pap. 2015, 48, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukozkan, G.; Vardaloglu, Z. Analyzing CPFR success factors using fuzzy cognitive maps in the retail industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 10438–10455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, M.; Ciarapica, F.E.; Marcucci, G.; Mazzuto, G. Fuzzy cognitive maps approach for analysing the domino effect of factors affecting supply chain resilience: A fashion industry case study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 6370–6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadeh, A.; Salehi, V.; Arvan, M.; Dolatkhah, M. Assessment of resilience engineering factors in high-risk environments by fuzzy cognitive maps: A petrochemical plant. Saf. Sci. 2014, 68, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nápoles, G.; Papageorgiou, E.; Bello, R.; Vanhoof, K. On the convergence of sigmoid fuzzy cognitive maps. Inf. Sci. 2016, 349, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K.; Chudasama, H. Pathways for climate resilient development: Human well-being within a safe and just space in the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 68, 102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Manufacturing (IFM). SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats). 2016. Available online: https://www.ifm.eng.cam.ac.uk/research/dstools/swot/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Balamuralikrishna, R.; Dugger, J.C. SWOT Analysis--A management tool for initiating new programs in vocational schools. J. Vocat. Tech. Educ. 1995, 12, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. The Strategy-Focused Organization, 1st ed.; Harvard Business Review Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; p. 29. ISBN 13-978-1578512508. [Google Scholar]

- al-Bahi, A.M.; abd-Elwahed, M.S.; Soliman, A.Y. Implementation of sustainability indicators in engineering education using a combined balanced scorecard and quality function deployment approaches. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozesmi, U. The Wants and Desires of the Local Population Based on Cognitive Mapping, Yusufeli Damlake Resettlement Plan), State Hydraulic Works; Sahara Engineering: Ankara, Turkey, 2001; pp. 154–169. [Google Scholar]

- Erkan, E.F.; Uygun, O.; Demir, H.I. An Evaluation Model for Green Supply Chain Management Using Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. Acad. Platf.-J. Eng. Sci. 2017, 5, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Erkan, E.F.; Uygun, O.; Kiraz, A. A novel approach for institutionalization analysis based on fuzzy cognitive maps. Sak. Univ. J. Sci. 2018, 22, 557–571. [Google Scholar]

- Tuncer, A.I.; Tuncer, M.U. Evaluation of Factors Affecting Public Relations Decision Making Processes by Cognitive Mapping Method. Galatasaray Univ. J. Commun. 2017, 27, 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Arvan, M.; Omidvar, A.; Ghodsi, R. Intellectual capital evaluation using fuzzy cognitive maps: A scenario-based development planning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 55, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altun, F. A Comparative Regional Mapping Study on The Obstacles Perceived by Tourism Students in Front of Their Entrepreneurial Activities. Master’s Thesis, Kocaeli University, Kocaeli, Turkey, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, M. Thinking about growth: A cognitive mapping approach to understanding small business development. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 1994, 1, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, V.; Bowman, C. Reducing Causal Ambiguity To Facilitate Strategic Learning. Manag. Learn. 2005, 36, 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavas, A. Using Cognitive Map Method in Strategy Development: An Application. Ph.D. Thesis, Kocaeli University, Kocaeli, Turkey, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Saruhan, S.C.; Ozdemirci, A. Science, Philosophy and Methodology: Method Problem in Research-SPSS Applied, 2nd ed.; Beta Press: Istanbul, Turkiye, 2011; p. 180. ISBN 978-605-377-499-0. [Google Scholar]

- Desicion Explorer. Desicion Explorer Users Guide. 2017. Available online: https://banxia.com/pdf/de/DEGuide.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Cıgır, T. Performance Appraising Systems Application in Education Sector. Master’s Thesis, Marmara University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineno, C.J. The Business School Strategy: Continuous Improvement by Implementing the Balanced Scorecard. Res. High. Educ. J. 2007, 1, 77. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil, H.F., Jr.; Bensimon, E.M.; Diamond, M.A.; Moore, M.R. Designing and implementing an academic scorecard. Change Mag. High. Learn. 1999, 31, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schobel, K.; Scholey, C. Balanced Scorecards in education: Focusing on financial strategies. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2012, 16, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozmantar, Z.K. Using Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Performance Management Tool in Schools. Ph.D. Thesis, Gaziantep University, Gaziantep, Türkiye, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Karathanos, D.; Karathanos, P. Applying the balanced scorecard to education. J. Educ. Bus. 2005, 80, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, E.C. Developing a Model for Evaluation of Customer Relationship Management Technology Investment Decision and an Application. Master’s Thesis, Yıldız Technical University, Istanbul, Turkiye, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.S.; Wohlstetter, P.; Liu, S. Developing an indicator system for schools of choice: A balanced scorecard approach. J. Sch. Choice 2009, 2, 392–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanoba, T. Developing Balanced Scorecard in Official Secondary Schools and a Model Proposal. Master’s Thesis, Marmara University-Istanbul Sabahattin Zaim University, Istanbul, Turkiye, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, A.R.; Chow, C.W.; Haddad, K.M. Continuous Improvement in Business Education: Insights from the For-Profit Sector and Business School Deans. J. Educ. Bus. 1999, 74, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaoglu, E.; Simsek, Y.; Altınkurt, Y. Application of SWOT analysis in vocational high schools before strategic planning. Educ. Sci. 2006, 140, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yelken, T.Y.; Kılıc, F.; Ozdemir, C. The strategic planning (SWOT) analysis outcomes and suggestions according to the students and the lecturers within the distance education system. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2012, 13, 267–276. [Google Scholar]

- Karaman, A. SWOT Analysis in Strategic Plans of Universities. Master’s Thesis, Inonu University, Malatya, Turkiye, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pucciarelli, F.; Kaplan, A. Competition and strategy in higher education: Managing complexity and uncertainty. Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.; Mourshed, M.; Whelan, F. Improving education in the Gulf. McKinsey Q. 2007, 3947, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Galyon, C.E.; Blondin, C.A.; Yaw, J.S.; Nalls, M.L.; Williams, R.L. The relationship of academic self-efficacy to class participation and exam performance. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2012, 15, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkul, R.; Demirtas, H.; Ustuner, M. Perceptions of school principals regarding their schools (A study of a SWOT analysis). E-Int. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 14, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, R. Class size, class composition, and the distribution of student achievement. Educ. Econ. 2014, 22, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jesus, F.; Castelli, M.; Oliveira, T.; Mendes, R.; Nunes, C.; Sa-Velho, M.; Rosa-Louro, A. Using artificial intelligence methods to assess academic achievement in public high schools of a European Union country. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.; Pardos, Z.A.; Baker, R.S.; Williams, J.J.; Smyth, P.; Yu, R.; Slater, S.; Baker, R.; Warschauer, M. Mining big data in education: Affordances and challenges. Rev. Res. Educ. 2020, 44, 130–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, A.; Varıcı, I. Use of Sustainability Balanced Scorecard Method in Performance Measurement: An Application In The Faculty of Dentistry. J. Account. Tax. Stud. 2022, 15, 183–211. [Google Scholar]

- Siambi, J.K. The Impact of Saudi Arabia’s Education Policies Under Vision 2030 on Student Performance: Saudi’s Progress Benchmarked with Malaysia’s Education Blueprint 2025. Adv. Soc. Sci. Manag. 2023, 1, 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Brummet, Q. The effect of school closings on student achievement. J. Public Econ. 2014, 119, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatay, Z.; Kurtulus, F.T.E. Public Policy Analysis: Primary Education Policies. Manag. Political Sci. Rev. 2022, 4, 108–128. [Google Scholar]

- Khamisu, M.S.; Paluri, R.A.; Sonwaney, V. Stakeholders’ perspectives on critical success factors for environmental social and governance (ESG) implementation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, S.A.; Ali, S.Z.; Zahid, R.M.A. Nurturing environmental champions: Exploring the influence of environmental-specific servant leadership on environmental performance in the hospitality industry. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 46281–46292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameswar, N.; Hasan, Z.; Shri, C.; Saini, N. Exploring the barriers to ESG adoption using modified TISM approach. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 5775–5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.H.; Hu, J.; Tseng, M.L.; Chiu, A.S.; Lin, C. Sustainable development in technological and vocational higher education: Balanced scorecard measures with uncertainty. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 120, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dang, W.; Li, Y. Can ESG Performance Promote Corporate Green Transformation? Evidence from Green OFDI in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.G.; Schaltegger, S. Sustainability balanced scorecards and their architectures: Irrelevant or misundertood? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcelik, F. Sustainability Performance Report Card. Yaşar University E-Journal. 2013, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.B. How to report a company’s sustainability activities. Manag. Account. Q. 2005, 7, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Lim, W.M.; Sureka, R.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Bamel, U. Balanced scorecard: Trends, developments, and future directions. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 2397–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Key Performance Indicator | KPI Score Calculation Basis | KPI Score Range | BSC Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | Quality of Students Admitted HSEE-HSEE Percentile | (Current—Achieved Percentile Rank)/ (Current—Targeted Percentile Rank) | 0.81 ≤ KPI ≤ 1.00 0.61 ≤ KPI ≤ 0.80 0.41 ≤ KPI ≤ 0.60 0.21 ≤ KPI ≤ 0.40 0.00 ≤ KPI ≤ 0.20 | 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 |

| 30 | HEEE and Practice Test Results | Number of Students Placed in University/Number of Students Taking the Exam | Same ranges as KPI 25 | Same scores as KPI 25 |

| 32 | Percentage of Satisfied Students | Satisfied Students/Total Students | Same ranges as KPI 25 | Same scores as KPI 25 |

| 34 | Sample Question Applications Similar to HEEE | Weekly HEEE Preparation Course Hours/Total Weekly Course Hours | Same ranges as KPI 25 | Same Scores as KPI 25 |

| 35 | Frequency of HEEE Practice Exam Applications | Weekly: 1.00 Every 15 Days: 0.80 Every 3 Weeks: 0.60 Monthly: 0.40 Over 1 Month: 0.20 | Direct Score Assignments | 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 |

| 37 | Percentage of Achievement of the Objectives of the Student Recovery Plan | Ratio of Students Accepted to their Targeted Programs | Same ranges as KPI 25 | Same scores as KPI 25 |

| 41 | Ratio of Financial Assets to Liabilities | Financial Payments and Liabilities/ Financial Assets and Revenues | ≥1.00 0.81–0.99 0.61–0.80 0.41–0.60 0.00–0.40 | 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 |

| 43 | Percentage of New Graduates, Intern | Number of New Graduates, Intern and | 0.00 ≤ KPI ≤ 0.20 | 1.0 |

| and Trainee Teachers | Trainee Teachers/ | 0.21 ≤ KPI ≤ 0.40 | 0.8 | |

| Total Number of Teachers | 0.41 ≤ KPI ≤ 0.60 | 0.6 | ||

| 0.61 ≤ KPI ≤ 0.80 | 0.4 | |||

| 0.81 ≤ KPI ≤ 1.00 | 0.2 | |||

| 46 | Percentage of Successful Teachers | Number of Successful Teachers/ Total Number of Teachers | Same ranges as KPI 25 | Same scores as KPI 25 |

| Strengths [55,89,90,91] | Frequency Count of Responses | Weaknesses [89,92] | Frequency Count of Responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Experienced Teaching Staff (51) | 208 | 1. Social and Sportive Activities (61) | 103 |

| 2. Good Communication with Teachers (58) | 143 | 2. Being a Free Public Service Provided by the State (62) | 80 |

| 3. Well-Educated and Qualified Students (52) | 138 | ||

| 4. Having High Achievement of the School (53) | 131 | ||

| Opportunities [55,91,92] | Frequency Count of Responses | Threats [65,89] | Frequency Count of Responses |

| 1. Having Ideal Class Size in Classrooms (68) | 152 | 1. Improper Use of Internet (76) | 95 |

| 2. School Being in the City-District Center (71) | 146 | 2. Students’ Preference for Academic High Schools (74) | 74 |

| 3. Rise in Demand for Higher Education (64) | 112 | ||

| 4. Increasing and Changing Student Population (65) | 105 |

| Main Dimensions | Critical Success Factors (CSFs) | Stat. Sig. (CSFs) | Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) | Stat. Sig. (KPIs) | KPIs Weights (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students and Parents | 1. Well-Educated and Qualified Students (2) | p < 0.01 * | 1.1. Quality of Students Admitted HSEE-HSEE Percentile (25) | p > 0.05 | 4.54 |

| 1.2. Successful Results in HEEE (5) | p < 0.05 | 1.2. HEEE and Practice Test Results (30) | p > 0.05 | 10.10 | |

| 1.3. Proper Use of the Internet (76) | – | – | – | – | |

| 1.4. Retaining Existing Students (8) | p < 0.01 | – | – | – | |

| 1.5. Students’ Satisfaction with Teaching Quality (4) | – | – | – | – | |

| 1.6. Effective Guidance and Counseling (7) | – | 1.3. Percentage of Satisfied Students (32) | p < 0.05 | 22.22 | |

| 1.7. Having Ideal Class Size in Classrooms (68) | – | – | – | – | |

| 1.8. Good Communication with Teachers (58) | p < 0.01 | – | – | – | |

| 1.9. Social and Sportive Activities (61) | – | – | – | – | |

| Teaching | 2.1. Good Lecturing and Problem Solving (10) | p < 0.001 | 2.1. HEEE Equivalent Question Solving (34) | p > 0.05 | 3.03 |

| 2.2. Increasing the Effectiveness of Teaching (23) | – | 2.2. Frequency of HEEE Practice Exam Applications (35) | p > 0.05 | 3.03 | |

| 2.3. Ensuring Equal Opportunities for All Students (14) | – | 2.3. Percentage of Achievement of the Objectives of the Student Recovery Plan (37) | p > 0.05 | 14.64 | |

| 2.4. Having High Achievement of the School (53) | p < 0.01 | – | – | – | |

| School Administration | 3.1. Sustainable Profitability (17) | p < 0.05 | 3.1. Ratio of Financial Assets to Liabilities (41) | – | – |

| 3.2. School Being in the City-District Center (71) | – | – | – | – | |

| Human Resources | 4.1. Experienced Teaching Staff (22, 51) | p < 0.001 | 4.1. Percentage of New Graduates, Intern and Trainee Teachers (43) | p > 0.05 | 16.68 |

| 4.2. Percentage of Successful Teachers (46) | p > 0.05 | 15.64 | |||

| Total | 100.00 |

| Critical Success Factors and Dimensions | Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) | Weighted BSC Score (BAHS) | Weighted BSC Score (CAHS) | Weighted BSC Score (SETHS) | Weighted BSC Score (SUTHS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students and Parents | |||||

| 1.1. Well-Educated and Qualified Students (2.52) | 1.1. Quality of Students Admitted HSEE-HSEE Percentile (25) | 4.54 | 4.54 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| 1.2. Successful Results in HEEE (5) | 1.2. HEEE and Practice Test Results (30) | 10.10 | 10.10 | 6.06 | 4.04 |

| 1.3. Proper Use of the Internet (76) | |||||

| 1.4. Retaining Existing Students (8) | |||||

| 1.5. Students’ Satisfaction with Teaching Quality (4) | |||||

| 1.6. Effective Guidance and Counseling (7) | 1.3. Percentage of Satisfied Students (32) | 17.78 | 22.22 | 22.22 | 22.22 |

| 1.7. Having Ideal Class Size in Classrooms (68) | |||||

| 1.8. Good Communication with Teachers (58) | |||||

| 1.9. Social and Sportive Activities (61) | |||||

| Teaching | |||||

| 2.1. Good Lecturing and Problem Solving (10) | 2.1. HEEE Equivalent Question Solving (34) | 1.82 | 1.82 | 1.21 | 3.03 |

| 2.2. Increasing the Effectiveness of Teaching (23) | 2.2. Frequency of HEEE Practice Exam Applications (35) | 3.03 | 3.03 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| 2.3. Ensuring Equal Opportunities for All Students (14) | 2.3. Percentage of Achievement of the Objectives of the Student Recovery Plan (37) | 11.72 | 14.64 | 5.86 | 8.79 |

| 2.4. Having High Achievement of the School (53) | |||||

| School Administration | |||||

| 3.1. Sustainable Profitability (17) | 3.1. Ratio of Financial Assets to Liabilities (41) | 6.06 | 10.10 | 10.10 | 10.10 |

| 3.2. School Being in the City-District Center (71) | |||||

| Human Resources | |||||

| 4.1. Experienced Teaching Staff (22, 51) | 4.1. Percentage of New Graduates, Intern and Trainee Teachers (43) | 16.68 | 16.68 | 16.68 | 13.34 |

| 4.2. Percentage of Successful Teachers (46) | 9.39 | 9.39 | 6.26 | 12.51 | |

| 81.12 | 92.52 | 67.89 | 77.58 |

| Scale | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha | Reliability Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| FCM Critical Success Factors Scale | 309 | 0.87 | High Reliability |

| SWOT Analysis Factors Scale | 27 | 0.83 | High Reliability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hekimoğlu, İ.; Özgen, D.; Şen, C. A Methodology for Identifying Critical Success Factors and Performance Measurement for Sustainable Schools. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104497

Hekimoğlu İ, Özgen D, Şen C. A Methodology for Identifying Critical Success Factors and Performance Measurement for Sustainable Schools. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104497

Chicago/Turabian StyleHekimoğlu, İhsan, Doğan Özgen, and Ceyda Şen. 2025. "A Methodology for Identifying Critical Success Factors and Performance Measurement for Sustainable Schools" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104497

APA StyleHekimoğlu, İ., Özgen, D., & Şen, C. (2025). A Methodology for Identifying Critical Success Factors and Performance Measurement for Sustainable Schools. Sustainability, 17(10), 4497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104497