Bridging Human Behavior and Environmental Norms: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach to Sustainable Tourism in Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

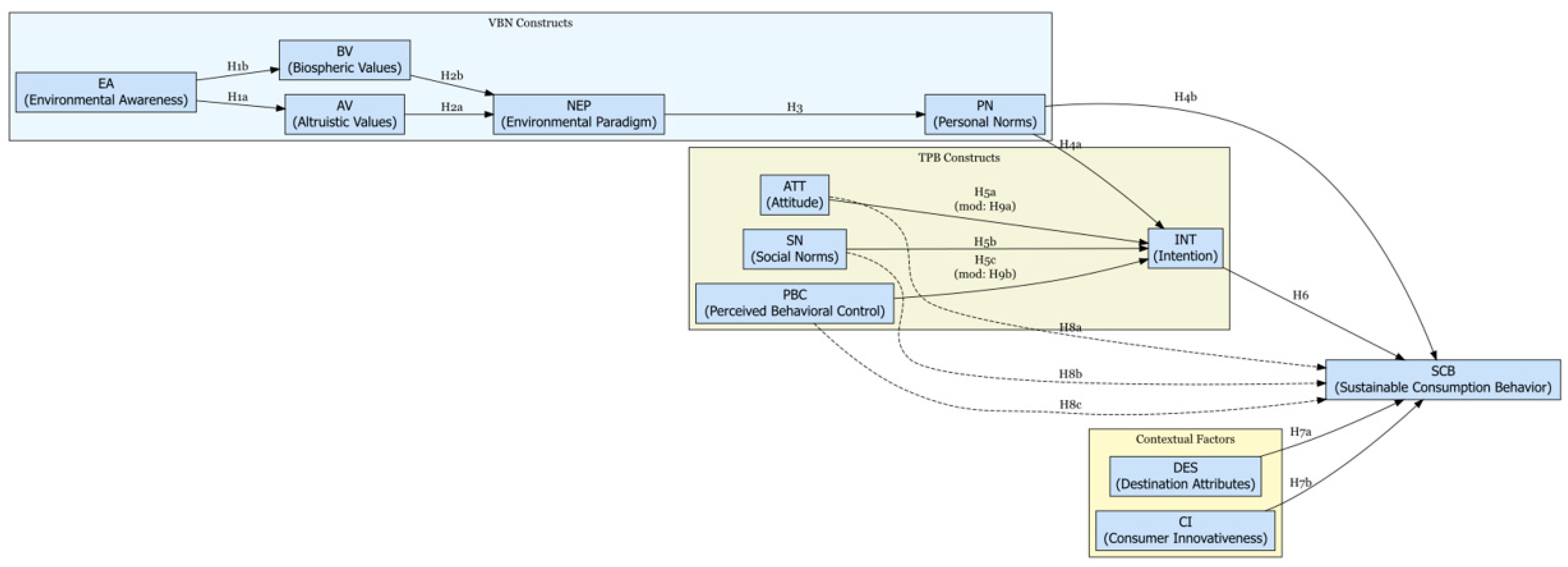

- Integrate core constructs from TPB (Attitude, Subjective Norms, Perceived Behavioral Control) and VBN (Environmental Awareness, Altruistic and Biospheric Values, New Environmental Paradigm) into a unified model capturing both rational and normative influences on SCB.

- Empirically validate this model using structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine direct and indirect pathways influencing Sustainable Consumption Behaviors.

- Investigate moderating effects of demographic and experiential factors (e.g., gender, travel experience) on these relationships.

- What are the key attitudinal and normative drivers influencing sustainable tourism consumption intentions among Vietnamese tourists?

- How do these intentions translate into actual sustainable behaviors, and what role do contextual factors, particularly Destination Attributes, play in this process?

- How do Personal Norms directly shape Sustainable Consumption Behavior in Vietnam’s collectivist culture, bypassing Behavioral Intention, and how does this differ from traditional TPB–VBN models?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Consumption Behavior in Tourism

2.2. Theoretical Foundations

2.3. Integration of TPB and VBN

2.4. Empirical Studies and Proposed Research Model

- H1a: Environmental Awareness positively influences Altruistic Values.

- H1b: Environmental Awareness positively influences Biospheric Values.

- H2a: Altruistic Values positively influence the New Environmental Paradigm.

- H2b: Biospheric Values positively influence the New Environmental Paradigm.

- H3: The New Environmental Paradigm positively influences Personal Norms.

- H4a: Personal Norms positively influence Behavioral Intention.

- H4b: Personal Norms directly influence Sustainable Consumption Behavior, bypassing Behavioral Intention.

- H5a: Attitude positively influences Behavioral Intention.

- H5b: Subjective Norms positively influence Behavioral Intention.

- H5c: Perceived Behavioral Control positively influences Behavioral Intention.

- H6: Behavioral Intention positively influences Sustainable Consumption Behavior.

- H7a: Destination Attributes positively influence Sustainable Consumption Behavior.

- H7b: Consumer Innovativeness positively influences Sustainable Consumption Behavior.

- H8a: Behavioral Intention mediates the relationship between Attitude and SCB.

- H8b: Behavioral Intention mediates the relationship between Subjective Norms and SCB.

- H8c: Behavioral Intention mediates the relationship between Perceived Behavioral Control and SCB.

- H9a: Gender moderates the relationship between Attitude and Behavioral Intention, with stronger effects among females.

- H9b: Travel experience moderates the relationship between Perceived Behavioral Control and Behavioral Intention, with weaker effects among experienced travelers.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

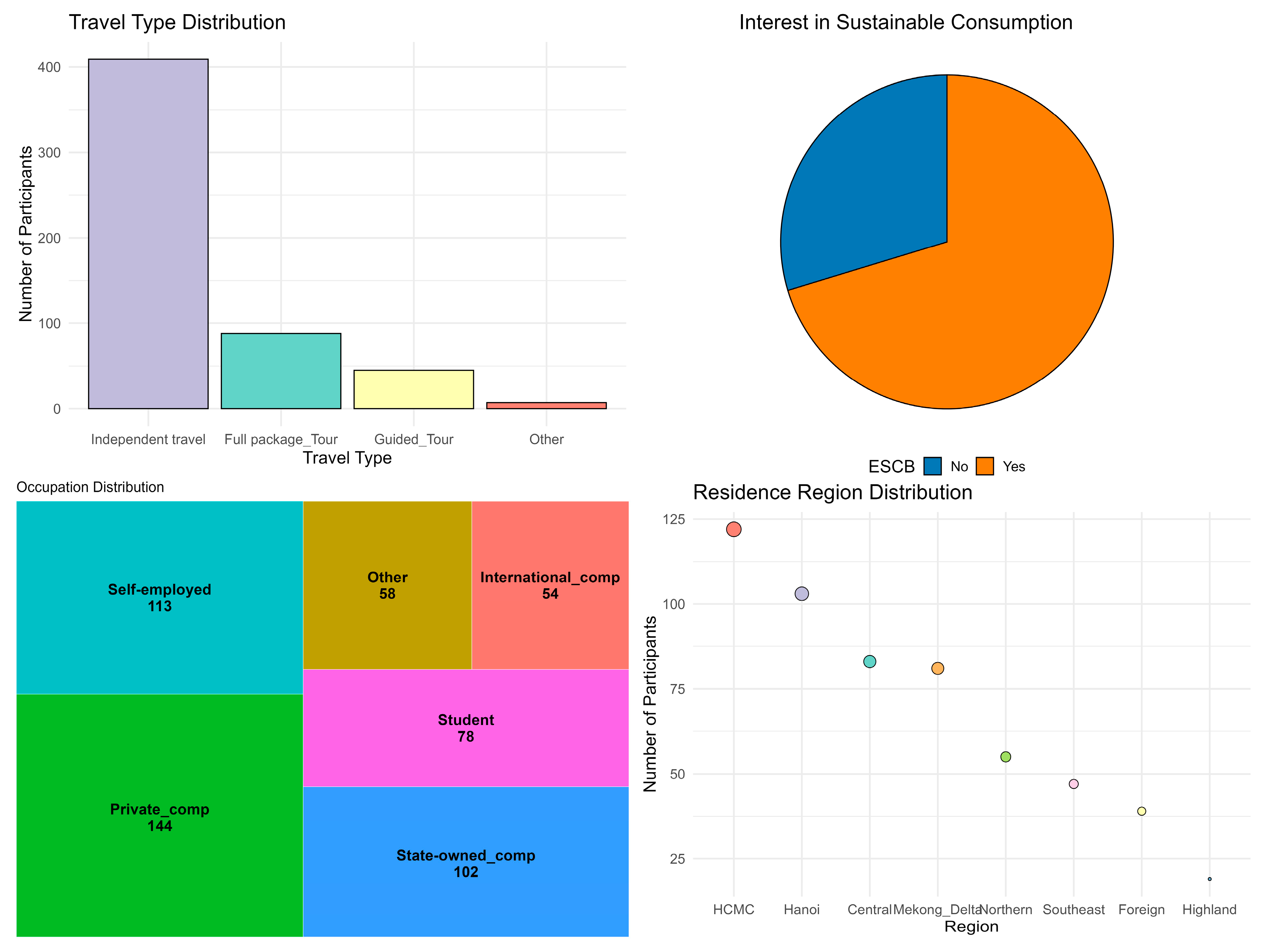

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

3.3. Measurement Instruments

- VBN constructs: Environmental Awareness (EA, 3 items), Altruistic Values (AV, 3 items), Biospheric Values (BV, 3 items), the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP, 4 items), and Personal Norms (PN, 3 items) were adapted from Stern et al. [22] and Kiatkawsin and Han [26]. Sample item: “I feel a moral duty to adopt sustainable practices during travel” (PN).

- Sustainable Consumption Behavior (SCB): This was measured with 5 items adapted from Vilkaite-Vaitone and Tamuliene [12], e.g., “I prioritize low-impact transportation options when traveling”.

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.4. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

4.5. Mediation and Moderation Analyses

4.6. Regression Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Factor | Main Constructs Identified | Representative Items (Highest Loadings) | Loading Range | Variance Explained (%) | Reliability Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR1 | Destination Attributes (DES), SCB | DES1 (0.66), DES2 (0.68), SCB1 (0.46) | 0.37–0.68 | 6% | Correlation = 0.88; R2 = 0.77 |

| MR2 | Environmental Awareness (EA), Biospheric Values (BV) | EA4 (0.54), BV3 (0.65), BV1 (0.63) | 0.43–0.65 | 6% | Correlation = 0.88; R2 = 0.78 |

| MR3 | Consumer Innovativeness (CI) | CI1 (0.71), CI2 (0.66), CI3 (0.65) | 0.63–0.71 | 4% | Correlation = 0.88; R2 = 0.77 |

| MR4 | Attitude (ATT), Intention (INT) | ATT1 (0.67), ATT3 (0.64), ATT4 (0.62) | 0.25–0.67 | 5% | Correlation = 0.86; R2 = 0.74 |

| MR5 | Altruistic Values (AV) | AV1 (0.65), AV3 (0.64), AV4 (0.64) | 0.61–0.65 | 3% | Correlation = 0.86; R2 = 0.74 |

| MR6 | New Environmental Paradigm (NEP), Personal Norms (PN) | NEP1 (0.63), PN2 (0.44), PN3 (0.43) | 0.37–0.63 | 4% | Correlation = 0.84; R2 = 0.71 |

| MR7 | Subjective Norms (SN) | SNO2 (0.77), SNO1 (0.68), SNO3 (0.68) | 0.44–0.77 | 5% | Correlation = 0.88; R2 = 0.77 |

| MR8 | Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), Intention (INT) | PBC4 (0.59), PBC3 (0.57), INT4 (0.36) | 0.24–0.59 | 5% | Correlation = 0.83; R2 = 0.69 |

| Factor | Main Constructs Identified | Representative Items (Highest Loadings) | Loading Range | Variance Explained (%) | Reliability Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR1 | Destination Attributes (DES), SCB | DES1 (0.70), DES2 (0.68), SCB1 (0.51) | 0.33–0.70 | 6% | Correlation = 0.88; R2 = 0.77 |

| MR2 | Environmental Awareness (EA), Biospheric Values (BV) | EA4 (0.53), BV3 (0.65), BV1 (0.63) | 0.43–0.65 | 6% | Correlation = 0.88; R2 = 0.78 |

| MR3 | Consumer Innovativeness (CI) | CI1 (0.70), CI2 (0.66), CI3 (0.65) | 0.63–0.70 | 4% | Correlation = 0.88; R2 = 0.77 |

| MR4 | Attitude (ATT), Intention (INT) | ATT1 (0.66), ATT3 (0.65), ATT4 (0.62) | 0.27–0.66 | 5% | Correlation = 0.86; R2 = 0.74 |

| MR5 | Altruistic Values (AV) | AV1 (0.65), AV3 (0.64), AV4 (0.64) | 0.61–0.65 | 4% | Correlation = 0.86; R2 = 0.74 |

| MR6 | New Environmental Paradigm (NEP), Personal Norms (PN) | NEP1 (0.62), PN2 (0.45), PN3 (0.44) | 0.37–0.62 | 5% | Correlation = 0.84; R2 = 0.71 |

| MR7 | Subjective Norms (SN) | SNO2 (0.77), SNO1 (0.66), SNO3 (0.68) | 0.43–0.77 | 4% | Correlation = 0.88; R2 = 0.77 |

| MR8 | Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), Intention (INT) | PBC4 (0.57), PBC3 (0.57), INT4 (0.33) | 0.24–0.57 | 4% | Correlation = 0.82; R2 = 0.67 |

References

- Anh, L.H.; Hien, T.T.; Sang, N.Q. Sustainable Tourism Development in Vietnam in the Current Period. Arch. Bus. Res. 2024, 12, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Sustainable Tourism Framework; United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, A.D.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Nguyen, T.T.M.; Bui, H.L.; Pham, T.N. Tourism social sustainability in remote communities in Vietnam: Tourists’ behaviors and their drivers. Heliyon 2023, 10, e23619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, H.; Pham, L.H.; Pham, N.; Dang, P.A.; Bui, Q.; Nguyen, D.; Duong, T.T.; Nguyen, C.; Saito, H. Vietnam tourism at the crossroads of socialism and market economy. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 1301–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Thanh, N.; Le, D.T.; Ha, N.T.T. Sustainable development tourism: Research in Vietnam after COVID-19. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2022, 13, 2397–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, L.T. Does exchange rate affect the foreign tourist arrivals? Evidence in an emerging tourist market. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T.T.; Ryan, C. Heritage and cultural tourism: The role of the aesthetic when visiting Mỹ Sơn and Cham Museum, Vietnam. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 19, 564–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, L.T. Tourism development in Vietnam: New strategy for a sustainable pathway. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2020, 31, 1174–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, N.T.T.; Thu, T.N.M.; San, N.D.; Ngoc, P.T.B. Understanding sustainable tourist behaviours of Vietnamese visitors in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1403, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuc, H.N.; Nguyen, H.M. The importance of collaboration and emotional solidarity in residents’ support for sustainable urban tourism: Case study Ho Chi Minh City. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, T.D.; Nguyen, Q.X.T.; Van Nguyen, H.; Dang, V.Q.; Tang, N.T. Toward sustainable community-based tourism development: Perspectives from local people in Nhon Ly coastal community, Binh Dinh province, Vietnam. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaite-Vaitone, N.; Tamuliene, V. Unveiling the untapped potential of green consumption in tourism. Sustainability 2024, 16, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Nguyen, T.H.H.; Morrison, A.M. Sustainable tourist behavior: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 32, 3356–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonincontri, P.; Marasco, A.; Ramkissoon, H. Visitors’ experience, place attachment and sustainable behaviour at cultural heritage sites: A conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; López-Sánchez, Y. Are tourists really willing to pay more for sustainable destinations? Sustainability 2016, 8, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A.; Blöbaum, A. A comprehensive action determination model: Toward a broader understanding of ecological behaviour using the example of travel mode choice. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Nguyen, V.T.; Pham, Q.V. The factors affecting sustainable tourism intention in Vietnam: Empirical study with extended theory of planned behavior. Foresight 2023, 25, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, V.D. Tourism policy development in Vietnam: A pro-poor perspective. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2013, 5, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. Available online: https://www.humanecologyreview.org/pastissues/her62/62sternetal.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Mathur, A.; Swarup, K.; Chaturvedi, P.; Kumar, R. Investigating Green Entrepreneurial Intention for Sustainability Through an Integrated VBN-TPB framework. In Implementing ESG Frameworks Through Capacity Building and Skill Development; Advances in Human Resources Management and Organizational Development Book Series; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denley, T.J.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Boley, B.B.; Hehir, C.; Abrams, J. Individuals’ intentions to engage in last chance tourism: Applying the value-belief-norm model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1860–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. Young travelers’ intention to behave pro-environmentally: Merging the value-belief-norm theory and the expectancy theory. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Zaman, M. Determinants of generation Z pro-environmental travel behaviour: The moderating role of green consumption values. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1846–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Liu, S.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Liang, S.; Deng, N. Love of nature as a mediator between connectedness to nature and sustainable consumption behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landon, A.C.; Woosnam, K.M.; Boley, B.B. Modeling the psychological antecedents to tourists’ pro-sustainable behaviors: An application of the value-belief-norm model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Font, X.; Liu, J. Tourists’ Pro-environmental behaviors: Moral obligation or disengagement? J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; Dayour, F.; Otoo, F.E.; Goh, B. Understanding backpacker sustainable behavior using the tri-component attitude model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1193–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M.; Wu, H.C. How do environmental knowledge, environmental sensitivity, and place attachment affect environmentally responsible behavior? An integrated approach for sustainable island tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, L.; Font, X.; Corrons, A. Sustainability-oriented innovation in tourism: An analysis based on the decomposed theory of planned behavior. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Phuong, T.H.T. The assessment of sustainable tourism: Application to Kien Giang destination in Vietnam. Econ. Bus. Adm. 2024, 14, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 5th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Khanh, N.X. Sustainable Tourism Development in Vietnam: Current Challenges, Government Initiatives and Pathways for Long-Term Sustainability. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2024, 11, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Variable | Indicator | Std. Loading | p-Value | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | ATT1–ATT4 | 0.637–0.706 | <0.001 | Acceptable |

| SN | SNO1–SNO4 | 0.640–0.765 | <0.001 | Good |

| PBC | PBC1–PBC4 | 0.577–0.685 | <0.001 | Acceptable |

| INT | INT1–INT4 | 0.592–0.679 | <0.001 | Acceptable |

| DES | DES1–DES4 | 0.583–0.737 | <0.001 | Good |

| EA | EA1–EA4 | 0.506–0.619 | <0.001 | Acceptable |

| AV | AV1–AV4 | 0.617–0.678 | <0.001 | Good |

| BV | BV1–BV4 | 0.665–0.736 | <0.001 | Good |

| NEP | NEP1–NEP4 | 0.578–0.644 | <0.001 | Acceptable |

| PN | PN1–PN4 | 0.484–0.649 | <0.001 | Moderate |

| CI | CI1–CI4 | 0.639–0.695 | <0.001 | Good |

| SCB | SCB1, SCB2, SCB4, SCB5 | 0.623–0.689 | <0.001 | Good |

| Hypothesis | Estimate | Std. Error | z-Value | p-Value | Std. Beta | 95% CI | R2 (%) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a EA → AV | 0.212 | 0.069 | 3.089 | 0.002 | 0.190 | [0.077, 0.347] | 3.6% | Supported |

| H1b EA → BV | 0.823 | 0.092 | 8.909 | <0.001 | 0.746 | [0.643, 1.003] | 55.6% | Supported |

| H2a AV → NEP | 0.142 | 0.054 | 2.612 | 0.009 | 0.137 | [0.036, 0.248] | 36.6% | Supported |

| H2b BV → NEP | 0.598 | 0.068 | 8.846 | <0.001 | 0.570 | [0.465, 0.731] | 36.6% | Supported |

| H3 NEP → PN | 0.352 | 0.054 | 6.479 | <0.001 | 0.510 | [0.246, 0.458] | 26.0% | Supported |

| H4a PN → INT | 0.103 | 0.056 | 1.845 | 0.065 | 0.098 | [−0.007, 0.213] | 53.3% | Not supported |

| H4b PN → SCB | 0.254 | 0.069 | 3.658 | <0.001 | 0.202 | [0.119, 0.389] | 60.8% | Supported |

| H5a ATT → INT | 0.244 | 0.060 | 4.047 | <0.001 | 0.277 | [0.126, 0.362] | 53.3% | Supported |

| H5b SN → INT | 0.162 | 0.046 | 3.540 | <0.001 | 0.230 | [0.072, 0.252] | 53.3% | Supported |

| H5c PBC → INT | 0.368 | 0.062 | 5.884 | <0.001 | 0.407 | [0.246, 0.490] | 53.3% | Supported |

| H6 INT → SCB | 0.471 | 0.078 | 6.026 | <0.001 | 0.393 | [0.318, 0.624] | 60.8% | Supported |

| H7a DES → SCB | 0.420 | 0.055 | 7.669 | <0.001 | 0.488 | [0.312, 0.528] | 60.8% | Supported |

| H7b CI → SCB | 0.105 | 0.040 | 2.621 | 0.009 | 0.122 | [0.027, 0.183] | 60.8% | Supported |

| Mediation Hypothesis | Indirect Effect | Std. Error | z-Value | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H8a: ATT → INT → SCB | 0.115 | 0.036 | 3.194 | 0.001 | [0.044, 0.186] | Significant partial mediation |

| H8b: SN → INT → SCB | 0.076 | 0.031 | 2.452 | 0.014 | [0.016, 0.137] | Significant mediation effect |

| H8c: PBC → INT → SCB | 0.173 | 0.041 | 4.219 | <0.001 | [0.093, 0.253] | Significant mediation effect |

| Moderation Hypothesis | Moderator Variable | Interaction Effect | Std. Error | z-Value | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H9a: Effect of ATT on INT moderated by gender | Gender | 0.118 | 0.051 | 2.314 | 0.021 | Stronger effect of ATT on INT for females |

| H9b: Effect of PBC on INT moderated by travel experience | Travel experience | −0.082 | 0.039 | −2.103 | 0.035 | PBC’s effect on INT decreases as travel experience shifts toward more structured travel experiences |

| Predictor | Estimate | Std. Error | t-Value | p-Value | Significance | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.083 | 0.266 | 0.313 | 0.755 | ns | Not significant |

| Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) | 0.234 | 0.041 | 5.726 | <0.001 | *** | Positive significant effect on SCB |

| Destination Attributes (DES) | 0.369 | 0.038 | 9.834 | <0.001 | *** | Strong positive significant effect on SCB |

| Personal Norms (PN) | 0.180 | 0.039 | 4.639 | <0.001 | *** | Positive significant effect on SCB |

| Consumer Innovativeness (CI) | 0.071 | 0.034 | 2.091 | 0.037 | * | Positive significant effect on SCB |

| Environmental Awareness (EA) | −0.037 | 0.036 | −1.023 | 0.307 | ns | No significant effect on SCB |

| Attitude (ATT) | 0.130 | 0.038 | 3.435 | <0.001 | *** | Positive significant effect on SCB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thuy, T.T.T.; Thao, N.T.T.; Thuy, V.T.T.; Hoa, S.T.O.; Nga, T.T.D. Bridging Human Behavior and Environmental Norms: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach to Sustainable Tourism in Vietnam. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104496

Thuy TTT, Thao NTT, Thuy VTT, Hoa STO, Nga TTD. Bridging Human Behavior and Environmental Norms: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach to Sustainable Tourism in Vietnam. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104496

Chicago/Turabian StyleThuy, Tran Thi Thu, Nguyen Thi Thanh Thao, Vo Thi Thu Thuy, Su Thi Oanh Hoa, and Tran Thi Diem Nga. 2025. "Bridging Human Behavior and Environmental Norms: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach to Sustainable Tourism in Vietnam" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104496

APA StyleThuy, T. T. T., Thao, N. T. T., Thuy, V. T. T., Hoa, S. T. O., & Nga, T. T. D. (2025). Bridging Human Behavior and Environmental Norms: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach to Sustainable Tourism in Vietnam. Sustainability, 17(10), 4496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104496