E-Leadership Within Public Sector Organisations: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Complexity of E-Leadership Concept

3. Research Methodology

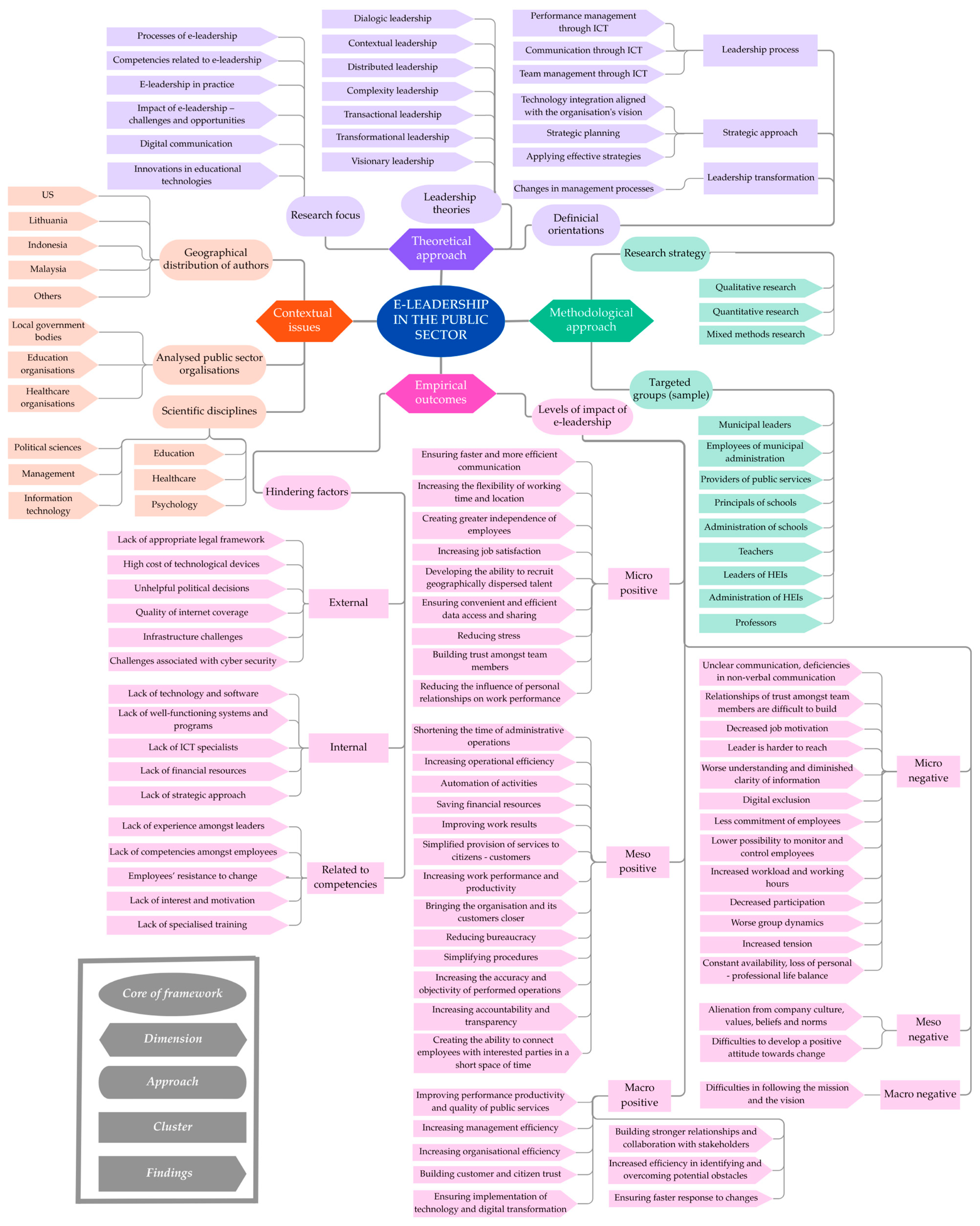

- What are the characteristics of articles within this field, such as the geographical distribution of authors, the diversity of scientific disciplines represented, and the range of public sector organisations studied?

- Which leadership theories are predominantly applied in these studies, and what theoretical variations and the principal research directions can be identified?

- What is the variety of methodological approaches adopted?

- What are the main implications of the results of the specific study? What challenges are highlighted in the articles? How is the impact of e-leadership evaluated across different levels (micro, meso, and macro)?

4. Results

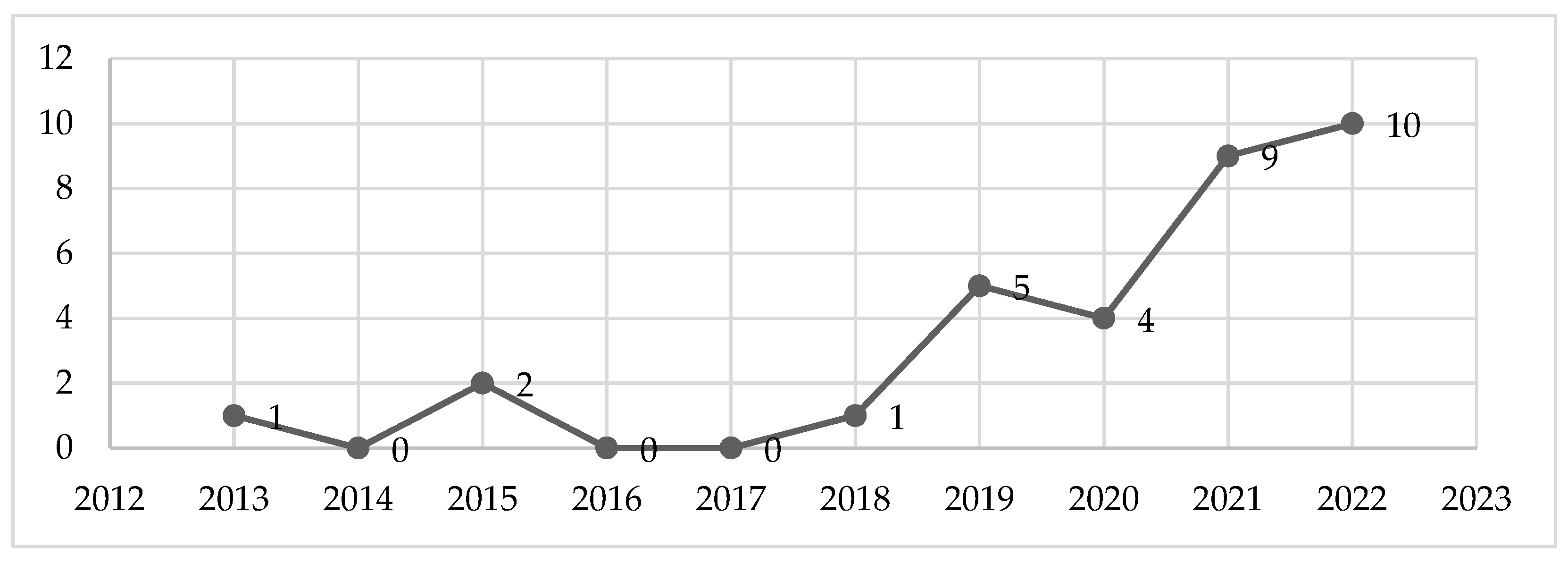

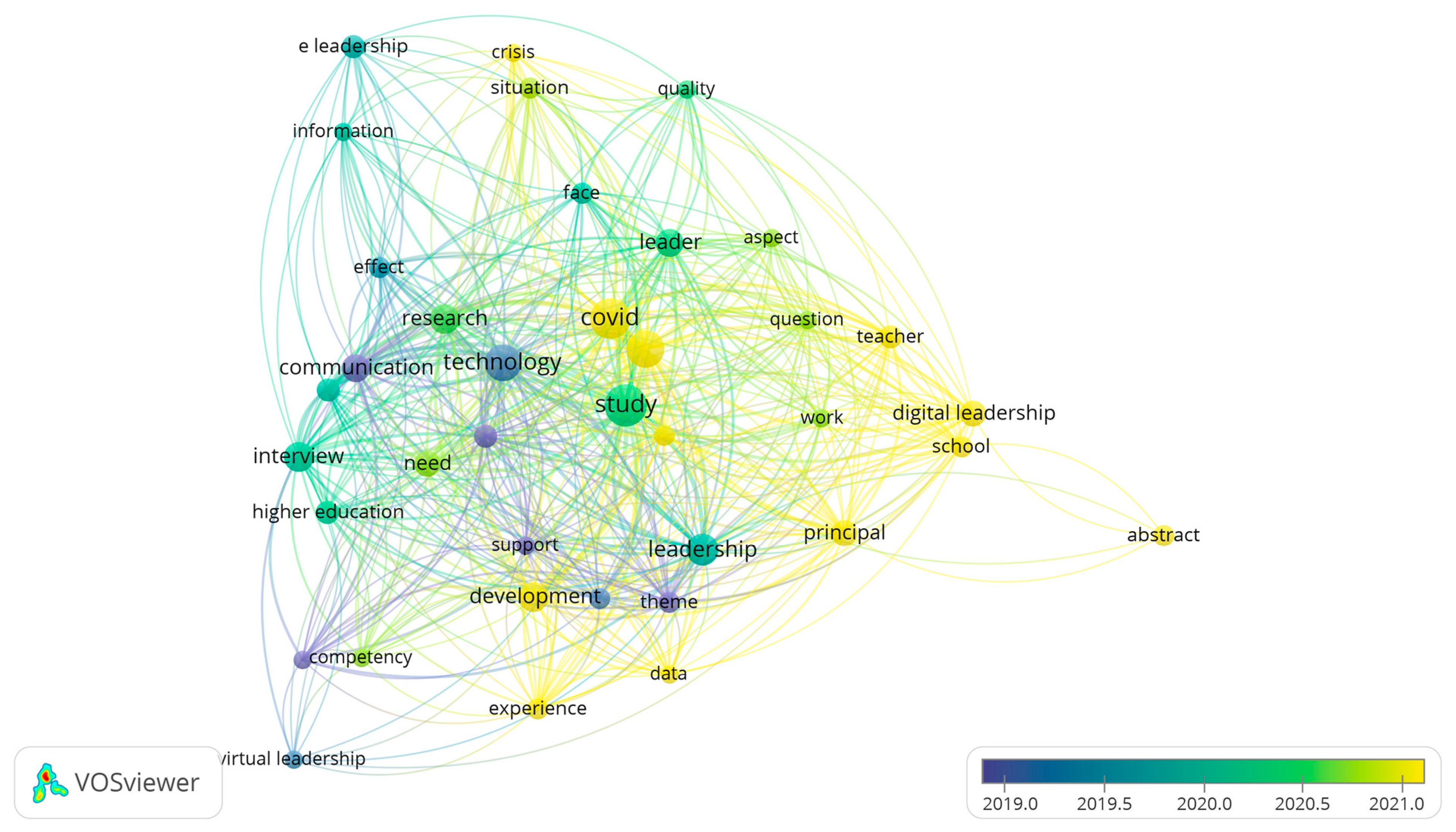

4.1. Characteristics of the Literature

4.2. Theoretical Variations of E-Leadership in Public Sector Organisations

4.3. Challenges of E-Leadership in Public Sector Organisations

4.4. Impact of E-Leadership in Public Sector Organisations

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Searching Phrase | Open Source | From the Period of 2003–2022 | Scientific Publications (Articles) | Based on the Topic and Abstract | Selected to the Final Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. ERIC | ||||||

| 1. | E-leadership | 930 | 456 | 202 | 5 | 4 |

| 2. | E-management | 2095 | 1080 | 735 | 4 | - |

| 3. | Electronic leadership | 368 | 250 | 166 | 7 | 4 |

| 4. | Digital leadership | 209 | 159 | 81 | 11 | 2 |

| 5. | Remote leadership | 81 | 56 | 28 | - | - |

| 6. | Virtual leadership | 164 | 126 | 68 | 7 | 4 |

| II. BUSINESS SOURCE ULTIMATE (EBSCO) | ||||||

| 1. | E-leadership | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 2. | E-management | 26 | 26 | 22 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. | Electronic leadership | 68 | 64 | 64 | 4 | 1 |

| 4. | Digital leadership | 57 | 57 | 57 | 5 | 1 |

| 5. | Remote leadership | 7 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| 6. | Virtual leadership | 29 | 28 | 28 | - | - |

| III. PUBMED CENTRAL | ||||||

| 1. | E-leadership | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | - |

| 2. | E-management | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3. | Electronic leadership | 171 | 170 | 170 | 2 | - |

| 4. | Digital leadership | 86 | 85 | 85 | - | 2 |

| 5. | Remote leadership | 22 | 22 | 22 | - | - |

| 6. | Virtual leadership | 45 | 44 | 44 | 4 | - |

| IV. CEEAS (EBSCO) | ||||||

| 1. | E-leadership | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| 2. | E-management | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3. | Electronic leadership | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4. | Digital leadership | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5. | Remote leadership | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6. | Virtual leadership | - | - | - | - | - |

| V. ACADEMIC SEARCH ULTIMATE (EBSCO) | ||||||

| 1. | E-leadership | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 2. | E-management | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3. | Electronic leadership | 141 | 139 | 136 | 4 | - |

| 4. | Digital leadership | 94 | 93 | 93 | 2 | - |

| 5. | Remote leadership | 21 | 21 | 21 | 2 | 1 |

| 6. | Virtual leadership | 44 | 43 | 43 | 1 | - |

| VI. SPRINGER ONLINE JOURNALS COMPLETE | ||||||

| 1. | E-leadership | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - |

| 2. | E-management | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3. | Electronic leadership | 86 | 84 | 84 | 4 | - |

| 4. | Digital leadership | 89 | 88 | 88 | 3 | 1 |

| 5. | Remote leadership | 9 | 9 | 9 | - | - |

| 6. | Virtual leadership | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| VII. ELABA | ||||||

| 1. | E-leadership | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| 2. | E-management | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| 3. | Electronic leadership | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| 4. | Digital leadership | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5. | Remote leadership | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - |

| 6. | Virtual leadership | 4 | 4 | 2 | - | - |

| VIII. EDUCATION SOURCE (EBSCO) | ||||||

| 1. | E-leadership | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 2. | E-management | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3. | Electronic leadership | 100 | 96 | 96 | 1 | - |

| 4. | Digital leadership | 49 | 48 | 46 | 2 | 1 |

| 5. | Remote leadership | 5 | 5 | 5 | - | - |

| 6. | Virtual leadership | 31 | 29 | 29 | 1 | 2 |

| IX. SCIENCEDIRECT | ||||||

| 1. | E-leadership | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 2. | E-management | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3. | Electronic leadership | 44 | 44 | 44 | 1 | 1 |

| 4. | Digital leadership | 28 | 28 | 28 | 1 | 1 |

| 5. | Remote leadership | 6 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 6. | Virtual leadership | 17 | 17 | 17 | 2 | 1 |

| IN TOTAL: | ||||||

| 1. | E-leadership | 962 | 486 | 232 | 24 | 17 |

| 2. | E-management | 2122 | 1107 | 757 | 5 | 1 |

| 3. | Electronic leadership | 979 | 853 | 760 | 23 | 6 |

| 4. | Digital leadership | 616 | 552 | 479 | 25 | 9 |

| 5. | Remote leadership | 153 | 128 | 100 | 6 | 3 |

| 6. | Virtual leadership | 335 | 330 | 270 | 16 | 8 |

| Code | Title | Author(s) | Year | Journal | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Impactful Leadership Traits of Virtual Leaders in Higher Education | Alward, E., Phelps, Y. | 2019 | Online Learning, 23(3), 72–93. | [59] |

| A2 | Analysis of E-leadership Practices in Ameliorating Learning Environment of Higher Education Institutions | Aurangzeb, W. | 2020 | Pakistan Journal of Distance and Online Learning, 5(2), 1–16. | [71] |

| A3 | Leading Remotely: Competencies Required for Virtual Leadership | Azukas, M. E. | 2022 | TechTrends, 66(2), 327–337. | [72] |

| A4 | Emails from the Boss—Curse or Blessing? Relations between Communication Channels, Leader Evaluation, and Employees’ Attitudes | Braun, S., Hernandez Bark, A., Kirchner, A., Stegmann, S., Van Dick, R. | 2019 | International Journal of Business Communication, 56(1), 50–81. | [67] |

| A5 | E-Leadership Analysis during Pandemic Outbreak to Enhanced Learning in Higher Education | Chang, C. L., Arisanti, I., Octoyuda, E., Insan, I. | 2022 | TEM Journal, 11(2), 932–938. | [50] |

| A6 | How to Evaluate Digital Leadership: A Cross-Sectional Study | Claassen, K., Dos Anjos, D. R., Kettschau, J., Broding, H. C. | 2021 | Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 16(1), 1–8. | [57] |

| A7 | An Exploration of the Moderating Effect of Motivation on the Relationship between Work Satisfaction and Utilization of Virtual Team Effectiveness Attributes: A Mixed Methods Study | Day, F. C., Burbach, M. E. | 2015 | Creighton Journal of Interdisciplinary Leadership, 1(2), 86–106. | [22] |

| A8 | Interpersonal Connectivity Work: Being there with and for Geographically Distant Others | Hafermalz, E., Riemer, K. | 2020 | Organization Studies, 41(12), 1627–1648. | [73] |

| A9 | The Effects of Principals’ Digital Leadership on Teachers’ Digital Teaching during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Malaysia | Hamzah, N. H., Nasir, M. K. M., Wahab, J. A. | 2021 | Journal of Education and E-Learning Research, 8(2), 216–221. | [10] |

| A10 | E-Management as a Game Changer in Local Public Administration | Vilkaite-Vaitone, N., Povilaitiene, K. | 2022 | Economies, 10(8), 180, 1–16. | [63] |

| A11 | Digitalisation and E-leadership in Local Government before COVID-19: Results of an Exploratory Study | Rybnikova, I., Juknevičienė, V., Toleikienė, R., Leach, N., Āboliņa, I., Reinholde, I., Sillamäe, J. | 2022 | Forum Scientiae Oeconomia, 10(2), 173–191. | [30] |

| A12 | Contemporary Communication Conduit among Exemplar School Principals in Malaysian Schools | Saraih, E. F., Wong, S. L., Asimiran, S., Khambari, M. N. M. | 2022 | Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 17(1), 1–23. | [8] |

| A13 | Remote and Technology-Based Dialogic Development during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Positive and Negative Experiences, Challenges, and Learnings | Syvänen, S., Loppela, K. | 2022 | Challenges, 13(1), 2, 1–24. | [66] |

| A14 | Supporting Professional Development through Digital Principal Leadership | Sterrett, W., Richardson, J. W. | 2020 | Journal of Organizational and Educational Leadership, 5(2), 4, 1–19. | [68] |

| A15 | Towards Remote Leadership in Health Care: Lessons Learned from an Integrative Review | Terkamo-Moisio, A., Karki, S., Kangasniemi, M., Lammintakanen, J., Häggman-Laitila, A. | 2022 | Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(3), 595–608. | [3] |

| A16 | Whether and How does the Crisis-induced Situation Change E-leadership in the Public Sector? Evidence from Lithuanian Public Administration | Toleikienė, R., Rybnikova, I., Juknevičienė, V. | 2020 | Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 16(SI), 149–166. | [46] |

| A17 | The Responsiveness of Teacher Education Managers at an ODeL College to Resilience and the Well-Being of Staff Working from Home during COVID-19 | van Wyk, M. M., Kotze, C. J., Tshabalala, S. L., Mukhati, F. | 2021 | International Journal of Educational Methodology, 7(4), 623–635. | [74] |

| A18 | The Role of Universities’ Electronic Management in Achieving Organizational Excellence: Example of Al Hussein Bin Talal University | Waswas, D., Jwaifell, M. | 2019 | World Journal of Education, 9(3), 53–66. | [75] |

| A19 | Principals’ Perceptions of the Importance of Technology in Schools | Waxman, H. C., Boriack, A. W., Lee, Y. H., and MacNeil, A. | 2013 | Contemporary Educational Technology, 4(3), 187–196. | [76] |

| A20 | The Needs of the Virtual Principal amid the Pandemic | Westberry, L., Hornor, T., Murray, K. | 2021 | International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 17(10), n10. | [77] |

| A21 | The Implementation of E-Management Overview in Higher Education | Somantri, M. | 2021 | Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT), 12(6), 1581–1594. | [61] |

| A22 | Transforming the Digital Leadership to Improve Public Service Performance in the COVID-19 Outbreak | Susilawati, D. M. | 2021 | Economic Annals-XXI, 188(3–4), 31–38. | [58] |

| A23 | Presumptions for E-leadership in Local Self-government in Lithuania | Toleikienė, R., Juknevičienė, V. | 2019 | Izzivi Prihodnosti, 4(3), 122–139. | [78] |

| A24 | Elektroninis vadovavimas darbuotojams vietos savivaldoje: koncepcinė analizė ir literatūros apžvalga | Toleikienė, R., Juknevičienė, V., Rybnikova, I. | 2022 | Public Policy and Administration, 21(1), 111–128. | [13] |

| A25 | The Impact of Digital Leadership on Teachers’ Technology Integration during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Kuwait | AlAjmi, M. K. | 2022 | International Journal of Educational Research, 112, 101928, 1–10. | [79] |

| A26 | Dawn or Dusk of the 5th age of Research in Educational Technology? A Literature Review on (E-) leadership for Technology-Enhanced Learning in Higher Education (2013–2017) | Arnold, D., Sangrà, A. | 2018 | International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 1–29. | [80] |

| A27 | Instructional Supervision and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Perspectives from Principals | Brock, J. D., Beach, D. M., Musselwhite, M., Holder, I. | 2021 | Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 11(1), 168–180. | [81] |

| A28 | Model of Virtual Leadership, Intra-team Communication and Job Performance among School Leaders in Malaysia | Ibrahim, M. Y. | 2015 | Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 186, 674–680. | [65] |

| A29 | Examining Teachers’ Perspectives on School Principals’ Digital Leadership Roles and Technology Capabilities during the COVID-19 Pandemic | Karakose, T., Polat, H., Papadakis, S. | 2021 | Sustainability, 13(23), 13448, 1–20. | [62] |

| A30 | Social Media e-Leadership Practices During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Higher Education | Kotula, N., Kaczmarek-Ciesielska, D., and Mazurek, G. | 2021 | Procedia Computer Science, 192, 4741–4750. | [60] |

| A31 | Defining E-leadership as Competence in ICT-mediated Communications: An Exploratory Assessment | Roman, A. V., Van Wart, M., Wang, X., Liu, C., Kim, S., McCarthy, A. | 2019 | Public Administration Review, 79(6), 853–866. | [12] |

| A32 | Lessons from a Crisis: Identity as a Means of Leading Remote Workforces Effectively | Leonardelli, G. J. | 2022 | Organizational Dynamics, 51, 1–15. | [82] |

References

- Palmucci, D.N.; Giovando, G.; Vincurova, Z. The post-Covid Era: Digital leadership, organizational performance and employee motivation. Manag. Decis. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gledson, B.; Zulu, S.L.; Saad, A.M.; Ponton, H. Digital leadership framework to support firm-level digital transformations for construction 4.0. Constr. Innov. 2024, 24, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkamo-Moisio, A.; Karki, S.; Kangasniemi, M.; Lammintakanen, J.; Häggman-Laitila, A. Towards remote leadership in health care: Lessons learned from an integrative review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauwens, R.; Cortellazzo, L. Five decades of leadership and ‘disruptive’ technology: From e-leadership and virtual team leadership to current conversations on digital leadership. In Research Handbook on Human Resource Management and Disruptive Technologies; Bondarouk, T., Meijerink, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- López-Figueroa, J.C.; Ochoa-Jiménez, S.; Palafox-Soto, M.O.; Sujey Hernandez Munoz, D. Digital leadership: A systematic literature review. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulat, G. Virtual Leadership: Learning to Lead Differently; Libri Publishing Limited: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Elmatsani, H.M.; Widianingsih, I.; Nurasa, H.; Munajat, M.D.E.; Suwanda, S. Exploring the evolution of leadership in government: A bibliometric study from e-government era into the digital age. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2414877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraih, E.F.; Wong, S.L.; Asimiran, S.; Khambari, M.N.M. Contemporary communication conduit among exemplar school principals in Malaysian schools. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2022, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuryadin, R.; Sobandi, A.; Santoso, B. Digital leadership in the public sector-systematic literature review: Systematic literature review. J. Ilmu Adm. Media Pengemb. Ilmu Dan Prakt. Adm. 2023, 20, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, N.H.; Nasir, M.K.M.; Wahab, J.A. The effects of principals’ digital leadership on teachers’ digital teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. J. Educ. E-Learn. Res. 2021, 8, 216–221. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1300492 (accessed on 5 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Van Wart, M.; Roman, A.; Wang, X.; Liu, C. Operationalizing the definition of e-leadership: Identifying the elements of e-leadership. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2019, 85, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, A.V.; Van Wart, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Kim, S.; McCarthy, A. Defining e-leadership as competence in ICT-mediated communications: An exploratory assessment. Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toleikienė, R.; Juknevičienė, V.; Rybnikova, I. Elektroninis vadovavimas darbuotojams vietos savivaldoje: Koncepcinė analizė ir literatūros apžvalga. Viešoji Polit. Ir Adm. 2022, 21, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schork, S.; Özdemir-Kaluk, D.; Zerey, C. Understanding innovation and sustainability in digital organizations: A mixed-method approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djatmiko, G.H.; Sinaga, O.; Pawirosumarto, S. Digital transformation and social inclusion in public services: A qualitative analysis of e-government adoption for marginalized communities in sustainable governance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.Y.; Akhtar, M.; Khan, A.Y. Digitalization for a sustainable performance: Dual-study analysis of digital leadership, circular economy, and technological innovation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.N.; Wang, Y.; Khan, N.A.; Ahmad, A. Digital leadership enhances employee empowerment, techno-work engagement, and sustainability: SEM analysis in public healthcare. Inq. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2025, 62, 00469580251317653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broccardo, L.; Truant, E.; Dana, L.P. The interlink between digitalization, sustainability, and performance: An Italian context. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Kahai, S.; Dodge, G.E. E-leadership: Implications for theory, research, and practice. Leadersh. Q. 2000, 11, 615–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Kahai, S.S. Adding the “e” to e-leadership: How it may impact your leadership. Organ. Dyn. 2003, 31, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Sosik, J.J.; Kahai, S.S.; Baker, B. E-leadership: Re-examining transformations in leadership source and transmission. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, F.C.; Burbach, M.E. An exploration of the moderating effect of motivation on the relationship between work satisfaction and utilization of virtual team effectiveness attributes: A Mixed methods study. Creighton J. Interdiscip. Leadersh. 2015, 1, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kahai, S.; Avolio, B.J.; Sosik, J.J. E-leadership. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of the Internet at Work; Hertel, G., Stone, D.L., Johnson, R.D., Passmore, J., Eds.; WILEY Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 285–314. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Ready, D.; Wang, X.; McCarthy, A.; Kim, A. E-leadership: An empirical study of organizational leaders’ virtual communication adoption. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 826–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stana, R.; Fischer, L.; Nicolajsen, H. Review for future research in digital leadership. In Proceedings of the Information Systems Research Conference in Scandinavia (IRIS41), Aarhus, Denmark, 5–8 August 2018; Available online: https://pure.itu.dk/ws/files/84744390/Review_for_future_research_in_digital_leadership.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Torres, F.C.; Baykal, E.; Abid, G. E-leadership and teleworking in times of COVID-19 and beyond: What we know and where do we go. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 590271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakose, T.; Kocabas, I.; Yirci, R.; Papadakis, S.; Ozdemir, T.Y.; Demirkol, M. The development and evolution of digital leadership: A bibliometric mapping approach-based study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobis, R.P.; Sularso, R.A.; Suroso, I.; Utami, E.S. The effect of e-leadership on employee performance: The mediating role of elasticity workplace. Int. J. Procure. Manag. 2024, 19, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwianto, R.A.; Mutiarin, D.; Nurmandi, A. Assessing e-leadership in the public sector during the COVID-19 Pandemic in ASEAN. J. Kebijak. Dan Adm. Publik 2021, 26, 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybnikova, I.; Juknevičienė, V.; Toleikienė, R.; Leach, N.; Āboliņa, I.; Reinholde, I.; Sillamäe, J. Digitalisation and e-leadership in local government before COVID-19: Results of an exploratory study. Forum Sci. Oeconomia 2022, 10, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumah, S.; Agusven, T. Implementation of e-leadership in government: Literature review. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 13164–13170. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/030a89debecec48125633bdbb7f1fe4a/1?cbl=2031963&pq-origsite=gscholar (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Paschoiotto, W.P.; Sehnem, S.; Cohen, E.D. E-leadership in the Brazilian public sector: The influence of communication quality on team commitment and performance. Adm. Pública E Gestão Soc. 2023, 15, 1–19. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/3515/351575641007/351575641007.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Karamalis, P.; Vasilopoulos, A. The digital transformation in public sector as a response to COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Greece. In Proceedings of the XIV Balkan Conference on Operational Research, Thessaloniki, Greece, 30 September—3 October 2020; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Athanasios-Vasilopoulos/publication/346657230_The_digital_transformation_in_public_sector_as_a_response_to_COVID-19_pandemic_The_case_of_Greece/links/5fccd749a6fdcc697be4f83d/The-digital-transformation-in-public-sector-as-a-response-to-COVID-19-pandemic-The-case-of-Greece.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Alqudah, M.A.; Muradkhanl, L. E-government in Jordan and studying the extent of the e-government development index according to the United Nations report. Int. J. Multidiscip. Appl. Bus. Educ. Res. 2021, 2, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaulė, E.; Žilinskas, G. E-governance in Lithuanian municipalities: External factors analysis of the websites development. Viešoji Polit. Ir. Adm. 2013, 12, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyad, D. Electronic governance: An overview of opportunities and challenges. Munich Pers. RePEc Arch. 2019, 92545, 1–14. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/92545 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Roxas, B. E-governance and sustainable human development in Asia: A dynamic institutional path perspective. J. Asian Bus. Econ. Stud. 2025, 32, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlambang, Y.; Susanto, T. E-Leadership: The effect of e-government success in Indonesia. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1201, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, R. What leaders should know about e-government. Socioecon. Chall. 2017, 1, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hamouche, S. COVID-19 and employees’ mental health: Stressors, moderators and agenda for organizational actions. Emerald Open Res. 2020, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Cordoba, P.; Benito, B.; Garcia-Sanchez, I. Efficiency in the governance of the COVID-19 pandemic: Political and territorial factors. Glob. Health 2021, 113, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Reyes, J.; Idrovo-Carlier, S.; Duque-Oliva, E. Remote work, work stress, and work-life during pandemic times: A Latin America situation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jämsen, R.; Sivunen, A.; Blomqvist, K. Employees’ perceptions of relational communication in full-time remote work in the public sector. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 132, 107240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim-Goh, M. The impacts of telework options on worker outcomes in local government: Social exchange and social exclusion perspectives. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2023, 43, 754–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavola, S.; Lakkala, M.; Folger, L.; Preegel, K.; Kokkonen, J.; Bardone, E.; Bauters, M. Transformed knowledge work infrastructures in times of forced remote work. Inf. Organ. 2025, 35, 100563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toleikienė, R.; Rybnikova, I.; Juknevičienė, V. Whether and how does the crisis-induced situation change e-leadership in the public sector? Evidence from Lithuanian public administration. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2020, 2020, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toleikienė, R.; Juknevičienė, V.; Rybnikova, I.; Menzel, V.; Abolina, I.; Reinholde, I. Main challenges of e-leadership in municipal administrations in the post-pandemic context. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çuhadar, S. Challenges and opportunities of e-leadership in organizations during COVID-19 crisis. SEA–Pract. Appl. Sci. 2022, 10, 83–89. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/cmj/seapas/y2022i29p83-89.html (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Gilli, K.; Lettner, N.; Guettel, W. The future of leadership: New digital skills or old analog virtues? J. Bus. Strategy 2024, 45, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Arisanti, I.; Octoyuda, E.; Insan, I. E-leadership analysis during pandemic outbreak to enhanced learning in higher education. TEM J. 2022, 11, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Pearson, A. The systematic review: An overview. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templier, M.; Paré, G. A framework for guiding and evaluating literature reviews. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 37, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paré, G.; Kitsiou, S. Methods for literature reviews. In Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-Based Approach; Lau, F., Kuziemsky, G., Eds.; University of Victoria: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2016; pp. 157–180. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höddinghaus, M.; Nohe, C.; Hertel, G. Leadership in virtual work settings: What we know, what we do not know, and what we need to do. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2023, 33, 188–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, K.; Dos Anjos, D.R.; Kettschau, J.; Broding, H.C. How to evaluate digital leadership: A cross-sectional study. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2021, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilawati, D.M. Transforming the digital leadership to improve public service performance in the COVID-19 outbreak. Econ. Ann.-XXI 2021, 188, 31–38. Available online: http://repository.unair.ac.id/id/eprint/114842 (accessed on 7 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Alward, E.; Phelps, Y. Impactful leadership traits of virtual leaders in higher education. Online Learn. 2019, 23, 72–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotula, N.; Kaczmarek-Ciesielska, D.; Mazurek, G. Social media e-leadership practices during the COVID-19 pandemic in higher education. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 192, 4741–4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somantri, M. The implementation of e-management overview in higher education. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. (TURCOMAT) 2021, 12, 1581–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakose, T.; Polat, H.; Papadakis, S. Examining teachers’ perspectives on school principals’ digital leadership roles and technology capabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaitė-Vaitonė, N.; Povilaitienė, K. E-management as a game changer in local public administration. Economies 2022, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, V.S.; Shukla, A. The association between virtual communication and leadership in the post-pandemic era: The role of emotional intelligence. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.Y. Model of virtual leadership, intra-team communication and job performance among school leaders in Malaysia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 186, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvänen, S.; Loppela, K. Remote and technology-based dialogic development during the COVID-19 pandemic: Positive and negative experiences, challenges, and learnings. Challenges 2022, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.; Hernandez Bark, A.; Kirchner, A.; Stegmann, S.; Van Dick, R. Emails from the boss—Curse or blessing? Relations between communication channels, leader evaluation, and employees’ attitudes. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2019, 56, 50–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterrett, W.; Richardson, J.W. Supporting professional development through digital principal leadership. J. Organ. Educ. Leadersh. 2020, 5, 4. Available online: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/joel/vol5/iss2/4 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Tigre, F.B.; Henriques, P.L.; Curado, C. The digital leadership emerging construct: A multi-method approach. Manag. Rev. Q. 2025, 75, 789–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintiya, E.S.; Susanto, T.D.; Ningrum, A.C.P. Electronics-leadership (e-leadership) dalam sektor e-government: Literature review. J. Nas. Teknol. Dan Sist. Inf. 2020, 6, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurangzeb, W. Analysis of e-leadership practices in ameliorating learning environment of higher education institutions. Pak. J. Distance Online Learn. 2020, 5, 1–16. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1266659 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Azukas, M.E. Leading remotely: Competencies required for virtual leadership. TechTrends 2022, 66, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafermalz, E.; Riemer, K. Interpersonal connectivity work: Being there with and for geographically distant others. Organ. Stud. 2020, 41, 1627–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, M.M.; Kotze, C.J.; Tshabalala, S.L.; Mukhati, F. The responsiveness of teacher education managers at an ODeL college to resilience and the well-being of staff working from home during COVID-19. Int. J. Educ. Methodol. 2021, 7, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waswas, D.; Jwaifell, M. The role of universities’ electronic management in achieving organizational excellence: Example of Al Hussein Bin Talal University. World J. Educ. 2019, 9, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxman, H.C.; Boriack, A.W.; Lee, Y.H.; MacNeil, A. Principals’ perceptions of the importance of technology in schools. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2013, 4, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westberry, L.; Hornor, T.; Murray, K. The needs of the virtual principal amid the pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Policy Leadersh. 2021, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toleikienė, R.; Juknevičienė, V. Presumptions for e-leadership in local self-government in Lithuania. Izzivi Prihodnosti 2019, 3, 122–139. Available online: https://ojs.fos-unm.si/index.php/ip/article/view/36 (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- AlAjmi, M.K. The impact of digital leadership on teachers’ technology integration during the COVID-19 pandemic in Kuwait. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 112, 101928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, D.; Sangrà, A. Dawn or dusk of the 5th age of research in educational technology? A literature review on (e-) leadership for technology-enhanced learning in higher education (2013–2017). Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2018, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, J.D.; Beach, D.M.; Musselwhite, M.; Holder, I. Instructional supervision and the COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives from principals. J. Educ. Res. Pract. 2021, 11, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardelli, G.J. Lessons from a crisis: Identity as a means of leading remote workforces effectively. Organ. Dyn. 2022, 51, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion of Articles | Exclusion of Articles |

|---|---|

| Articles published between 2003 and 2022 | Articles published before 2003 |

| Articles written in English and Lithuanian * | Articles written neither in English or Lithuanian |

| Articles evaluating e-leadership in public sector organisations | Articles where research was conducted in educational institutions treating e-leadership as a distance learning tool |

| Articles where research was carried out in non-public sector organisations | |

| Articles with open full-text access | Duplicates |

| Scientific Field | Codes of Articles |

|---|---|

| Information technology | A6; A8; A19 |

| Political science | A11 |

| Psychology | A4; A13; A22; A32 |

| Healthcare | A6; A15 |

| Education | A1; A2; A3; A9; A12; A14; A17; A18; A19; A20; A21; A25; A26; A27; A29; A31 |

| Management | A5; A7; A8; A10; A11; A13; A15; A16; A20; A21; A22; A23; A24; A26; A28; A30; A31 |

| Type of Organisations | Codes of Articles |

|---|---|

| Local government bodies | A6; A10; A11; A16; A22; A24; A31 |

| Education organisations | A1; A2; A3; A5; A7; A9; A12; A13; A14; A17; A18; A19; A20; A21; A25; A27; A28; A29; A30; A32 |

| Healthcare organisations | A8; A13; A15 |

| Groups of Public Sector Organisations | Research Focus | Codes of Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Local government bodies | Competencies related to e-leadership | A6; A31 |

| E-leadership in practice | A10; A11 | |

| Impact of e-leadership—challenges and opportunities | A16; A22 | |

| Processes of e-leadership | A23 | |

| Education organisations | Competencies related to e-leadership | A1; A3; A9; A17; A18; A19; A28; A29; A32 |

| Processes of e-leadership | A2; A5; A21; A27 | |

| Impact of e-leadership—challenges and opportunities | A7; A14; A20; A25 | |

| Digital communication | A12; A17; A30 | |

| Innovations in educational technologies | A19 | |

| Healthcare organisations | Impact of e-leadership—challenges and opportunities | A13 |

| E-leadership in practice | A15 | |

| Digital communication | A8 |

| Code of Article | Research Type | Sample | Targeted Group(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Qualitative research | 10 | Administrative leaders (managers), leading virtual teams in higher education |

| A2 | Qualitative research | 50 | Deans, directors and heads of departments of public universities |

| A3 | Qualitative research | 28 | Leaders of virtual schools |

| A4 | Quantitative research | 265 | Representatives of various fields: public services, data processing, health care, administration, consulting, training and civil service |

| A5 | Qualitative research | 24 | Rectors, deans, high school directors |

| A6 | Quantitative research | 546 | Employees utilising virtual workplaces in municipal administrations |

| A7 | Mix method research | 100, 31 | Members of virtual teams |

| A8 | Qualitative research | 13 | Nurses and their leaders (managers) |

| A9 | Quantitative research | 402 | Teachers in national secondary schools |

| A10 | Qualitative research | 7 | Leaders—various levels |

| A11 | Qualitative research | 8 | Representatives of municipal administrations in both leading and subordinate positions |

| A12 | Qualitative research | 16 | Principals, assistant principals, teachers and staff of schools |

| A13 | Mixed methods research | 39 working groups | Child protection and family care providers, elderly care providers, management groups, professional staff groups, political organisations |

| A14 | Qualitative research | 12 | Directors awarded the Digital Director Award |

| A15 | Mixed methods research | 21 | Articles with empirical research included, related to roles of remote managers and their responsibilities, remote manager–employee relations |

| A16 | Qualitative research | 2 | Representatives of municipal administrations in both leading and subordinate positions |

| A17 | Qualitative research | 6 | Direct managers—deans, heads of departments |

| A18 | Quantitative research | 249 | Members of the administration—academic leaders, managers |

| A19 | Mixed methods research | 310 | Principals of schools |

| A20 | Mixed methods research | 270, 10 | Principals and district officers |

| A21 | Mixed methods research | 177 | Heads of higher education institutions, administrative staff |

| A25 | Quantitative research | 517 | School principals and teachers from public primary schools |

| A26 | Qualitative research | 49 | Articles addressing the specific concept of e-leadership and studies, related to leadership and organisational changes in the field of higher education |

| A27 | Qualitative research | 2 | Heads of educational institutions |

| A28 | Quantitative research | 1082 | Heads of schools—principals, senior assistants and heads of departments |

| A29 | Qualitative research | 89 | Teachers with a master’s degree |

| A30 | Quantitative research | 216 | Heads of business schools |

| A31 | Mixed methods research | 243 | Employees in municipalities |

| A32 | Mixed methods research | 412 | Webinar participants |

| Theory of Leadership | Essence | Positive Impact on e-Leadership | Codes of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dialogic leadership | The leadership is a process that creates, develops, and consolidates leadership practices for all members of a community. |

| A13 |

| Contextual leadership | The leadership brings out the unique situational reality of the environment in which the leader exists. Behaviours, traditionally considered effective for leadership, may be constrained by the contextual environment. |

| A3 |

| Distributed leadership | The leadership emphasises the contribution of all members of the organisation to the practice of leadership and includes their various actions. It is a shared form of leadership amongst organisational members. |

| A11; A26 |

| Complexity leadership | The leadership should be seen not only as a position and power, but also as an emergent interactive dynamic that changes under the influence of multiple relationships in a complex institutional environment. |

| A12 |

| Transactional leadership | The main feature of transactional leadership is the exchange between the leader and the members of the organisation, when a monetary or other form of reward is received for the work performed. |

| A15; A31 |

| Transformational leadership | A of leadership, requiring managers and staff (leaders and employees) to work together to achieve strategic and operational goals, focusing on the development of the leader and organisational members, initiating changes. The theory is based on motivation, influence and mutual consideration, which can instil a sense of trust in employees. |

| A1; A4; A9; A15; A17; A22; A26; A30; A31 |

| Visionary leadership | The focus is on integrating the vision of the digital leader in the future development of the organisation. |

| A25; A29 |

| Orientations | Codes of Articles | Branches | Codes of Articles | Themes | Codes of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership process | A2; A10; A11; A12; A15; A16; A20; A22; A23; A24; A28 | Performance management through ICT | A2; A10; A11; A12; A16; A20; A23; A24 | Marketing through ICT | A10 |

| Information dissemination through ICT | A10; A20; A22 | ||||

| Service delivery through ICT | A10 | ||||

| Decision-making using ICT | A10; A28 | ||||

| Information management using ICT | A10 | ||||

| Communication through ICT | A11; A16; A20; A22 | ||||

| Team management through ICT | A15; A23 | Organising work using ICT | A28 | ||

| Task allocation through ICT | A28 | ||||

| Social impact through ICT | A24 | ||||

| Motivation through ICT | A23 | ||||

| Team problem solving using ICT | A28 | ||||

| Choosing the right electronic tools | A15; A26 | ||||

| Choosing the right policies | A15 | ||||

| Strategic approach | A9; A21; A29 | Technology integration aligned with the organisation’s vision | A9 | Mobilising digital tools | A9 |

| Adoption of digital tools | A9 | ||||

| Strategic planning | A9; A12 | Orientation towards future dynamics through ICT | A12 | ||

| Adoption of digital tools | A9 | ||||

| Applying effective strategies | A29 | Using ICT to achieve organisational objectives | A29 | ||

| Leadership transformation | A2; A9; A10; A12; A18; A22; A24; A25; A31 | Changes in management processes | A9; A25 | Change management | A31 |

| Transition to ICT applications | A18; A25 | ||||

| Transition to computer networks | A18 | ||||

| Digitising human resources management | A24 | ||||

| Transition to remote interaction | A22 | ||||

| Developing trust in virtual environments | A31 | ||||

| More efficient operations | A18 | ||||

| Category of Factors | Factors | Codes of Articles |

|---|---|---|

| External | Challenges associated with cyber security | A3; A16 |

| Lack of appropriate legal framework | A10; A16; A23; A24; A25 | |

| High cost of technological devices | A5 | |

| Unhelpful political decisions | A24 | |

| Quality of internet coverage | A16; A17; A27 | |

| Infrastructure challenges | A3; A5; A9; A10; A17 | |

| Internal | Lack of financial resources | A5; A10; A21; A23 |

| Lack of strategic approach | A11 | |

| Lack of technology and software | A1; A3; A5; A10; A16; A17; A24; A25; A27 | |

| Lack of well-functioning systems and programs | A13; A16; A24 | |

| Lack of ICT specialists | A10; A11 | |

| Related to competencies | Lack of specialised training | A1; A3; A7; A10; A11; A13; A16; A24 |

| Lack of experience amongst leaders | A5; A7; A10; A19 | |

| Lack of competencies amongst employees | A7; A10; A11; A13; A19; A24; A25; A27 | |

| Employees’ resistance to change | A5; A10; A11; A25 | |

| Lack of interest and motivation | A10 |

| Level | Impact | Aspects of Impact | Codes of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro | Positive | Ensuring faster and more efficient communication | A4; A9; A11; A12; A24; A28; A31 |

| Increasing the flexibility of working time and location | A5; A6; A8; A9; A13; A18; A24; A28; A32 | ||

| Creating greater independence of employees | A5; A13; A22; A24 | ||

| Increasing job satisfaction | A5 | ||

| Developing the ability to recruit geographically dispersed talent | A9; A13 | ||

| Ensuring convenient and efficient data access and sharing | A6; A11; A18; A22; A24; A28 | ||

| Reducing stress | A5; A24 | ||

| Building trust amongst team members | A31 | ||

| Reducing the influence of personal relationships on work performance | A18 | ||

| Negative | Unclear communication, deficiencies in non-verbal communication | A1; A4; A7; A11; A13; A24 | |

| Relationships of trust amongst team members are difficult to build | A1; A11; A32 | ||

| Decreased job motivation | A4; A7; A11; A13; A23 | ||

| Leader is harder to reach | A4 | ||

| Worse understanding and diminished clarity of information | A4; A16; A23 | ||

| Digital exclusion | A5; A11; A13; A20; A24 | ||

| Less commitment of employees | A11; A17 | ||

| Lower possibility to monitor and control employees | A11; A23 | ||

| Increased workload and working hours | A11; A13; A16 | ||

| Decreased participation | A13 | ||

| Worse group dynamics | A13 | ||

| Increased tension | A24 | ||

| Constant availability, loss of personal–professional life balance | A24 | ||

| Meso | Positive | Shortening the time of administrative operations | A9; A13; A18; A21 |

| Increasing operational efficiency | A9; A13; A24 | ||

| Automation of activities | A6 | ||

| Saving financial resources | A4; A9; A13; A18; A21; A24 | ||

| Improving work results | A12; A19; A28; A31 | ||

| Simplified provision of services to citizens–customers | A9 | ||

| Increasing work performance and productivity | A12; A18; A24 | ||

| Bringing the organisation and its customers closer | A24 | ||

| Reducing bureaucracy | A11; A18 | ||

| Simplifying procedures | A18 | ||

| Increasing the accuracy and objectivity of performed operations | A18 | ||

| Increasing accountability and transparency | A9; A12; A21 | ||

| Improving performance productivity and quality of public services | A22 | ||

| Creating the ability to connect employees with interested parties in a short space of time | A24 | ||

| Negative | Alienation from company culture, values, beliefs and norms | A17 | |

| Difficulties in developing a positive attitude towards change | A11 | ||

| Macro | Positive | Increasing management efficiency | A9 |

| Increasing organisational efficiency | A9; A24 | ||

| Building customer and citizen trust | A9 | ||

| Ensuring implementation of technology and digital transformation | A12; A25; A29 | ||

| Building stronger relationships and collaboration with stakeholders | A12; A14; A31 | ||

| Increased efficiency in identifying and overcoming potential obstacles | A25 | ||

| Ensuring faster response to changes | A15 | ||

| Negative | Difficulties in following the mission and the vision | A3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juknevičienė, V.; Leach, N.; Toleikienė, R.; Balčiūnas, S.; Razumė, G.; Rybnikova, I.; Āboliņa, I. E-Leadership Within Public Sector Organisations: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104474

Juknevičienė V, Leach N, Toleikienė R, Balčiūnas S, Razumė G, Rybnikova I, Āboliņa I. E-Leadership Within Public Sector Organisations: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104474

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuknevičienė, Vita, Nora Leach, Rita Toleikienė, Sigitas Balčiūnas, Gotautė Razumė, Irma Rybnikova, and Inese Āboliņa. 2025. "E-Leadership Within Public Sector Organisations: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104474

APA StyleJuknevičienė, V., Leach, N., Toleikienė, R., Balčiūnas, S., Razumė, G., Rybnikova, I., & Āboliņa, I. (2025). E-Leadership Within Public Sector Organisations: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 17(10), 4474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104474