1. Introduction

Technology and the Internet are two concepts that have been revolutionizing our daily lives for years. The contemporary reality of consumer societies consists of elements of modernity that emerged from the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Internet communication already played an essential role in the Third Industrial Revolution; however, in the Fourth, it gained new impetus thanks to the capabilities of artificial intelligence (AI). Information and communication technologies (ICTs) and the widespread promotion of the Industry 4.0 paradigm within scientific and business spheres have led to notable shifts in consumer behavior.

The proliferation of Internet accessibility, coupled with the increased reliance on online communication and shopping during the COVID-19 pandemic, has reshaped traditional consumer practices. The integration of the Internet into modern shopping processes has enhanced communication, collaboration, and interaction among consumers and businesses.

Technologies such as social networks, e-commerce platforms, mobile applications, and cloud computing have not only expanded access to information about products and services, but have also streamlined purchasing decisions, making them faster and more efficient. Additionally, innovations in payment systems, the development of personalized offers, and advancements in data analytics are driving transformations in traditional consumption patterns, enabling a more informed, tailored, and consumer-centric approach to shopping.

With this trend, consumers must remain mindful of the environmental impact of overconsumption. In the context of climate policies rapidly progressing toward achieving net zero emissions by 2050, the trend of collaborative consumption is contributing to this goal. As people become increasingly aware of global warming, they are adopting new consumption attitudes, one of which is collaborative consumption.

The radical shift in climate policy in EU countries necessitates individuals who are cognizant of various forms of consumption, and, most importantly, those who understand sustainable consumption, including collaborative consumption. Although Ukraine is not yet part of the EU, it is a neighbor to EU countries such as Poland. Moreover, the media is constantly reporting on Ukraine’s aspiration to join the EU. However, the ongoing conflict may hinder or delay its membership, even though discussions remain active.

Collaborative consumption, defined as a system in which individuals and service providers share resources through online platforms, is an attractive alternative to traditional housing and car rental models [

1]. This approach represents a potentially growing economic trend, fueled by the increasing adoption of digital technologies and an escalating emphasis on sustainability. By facilitating access rather than ownership, collaborative consumption not only optimizes resource use, but also aligns with evolving consumer preferences toward flexibility, cost efficiency, and environmental awareness. Supporting the collaborative economy is regarded as essential to achieving a sovereign digital ecosystem in which consumers have access to online goods and services, while businesses reap the benefits of digital potential.

Collaborative consumption is significantly supported by information and communication technologies (ICTs), which facilitate peer-to-peer (P2P) interactions [

2,

3]. Communication via mobile devices is a cornerstone of collaborative consumption. Collaborative consumption involves creating connections between individuals to share products and services [

4,

5], a process that is facilitated by a variety of platforms offering services ranging from pet care and electronics sharing to bicycle and car sharing. These platforms embody a modern approach to collaborative consumption, utilizing the Internet to meet a wide array of needs [

1,

6,

7].

The main goal of this research was to identify the phenomenon of collaborative consumption and its significance for sustainable consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine. The study, which involved 292 respondents, aimed to identify key shared products among young people in Ukraine and to understand the predominant attitudes and motivations driving their participation in the sharing economy. It further sought to identify and categorize the characteristics of consumer behavior in sharing economies. The results are intended not only to enrich the theoretical understanding of Generation Z’s consumer behavior, but also to provide practical insights for businesses and organizations striving to better align with the needs and expectations of this demographic group.

Generation Z comprises individuals born after 1995, who exhibit increased environmental awareness and a keen interest in sustainable practices, thereby contributing significantly to the development of collaborative consumption initiatives [

8]. The advent of the Internet, social media, modern mobile technologies, and online payment systems has made shared consumption more feasible, particularly among young people who spend more time online and tend to hold different values compared to the non-college population—more on this will be discussed later in the paper.

This paper consists of the following two main sections: a theoretical framework and an empirical investigation. The theoretical section, also known as the research background, lays the groundwork for the empirical study derived from field research. The paper begins with an introduction (

Section 1) that establishes the foundation for our exploration of collaborative consumption.

Section 2 outlines the theoretical basis of research on collaborative consumption and its significance for Generation Z consumers.

Section 3 describes the research methodology, including data collection from 292 representatives of Generation Z in Ukraine in 2024 using a survey questionnaire as the research tool.

Section 4 presents the analysis results, identifying the key attitudes and behavior of Generation Z consumers in Ukraine. This section also addresses the research questions (RQs) that guided the study, which are as follows:

RQ 1. What is the size of the segment of Generation Z in Ukraine that is inclined toward collaborative consumption?

RQ 2. What are the characteristics of the segment predisposed to collaborative consumption (PCC) and the segment not predisposed to collaborative consumption (NPCC) among Generation Z in Ukraine?

RQ 3. Do the PCC and NPCC segments exhibit different consumer attitudes and behaviors?

RQ 4. What are the drivers of collaborative consumption in the PCC segment among Generation Z in Ukraine?

RQ 5. Which of these drivers exerts the greatest influence on the propensity for collaborative consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine?

RQ 6. Does the propensity for collaborative consumption affect the propensity for sustainable consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine?

Section 5 delves into a discussion of the types of consumer behavior observed among Generation Z in the contexts of sustainable consumption and collaborative consumption, examining the implications of the findings for both theory and practice. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the main findings, discussing the limitations of the study, and suggesting directions for future research on Generation Z’s consumer behavior and their engagement with collaborative consumption in Ukraine, which is currently experiencing conflict.

The implications of this paper are in the socio-economic sphere, as well as reflecting the geopolitical trends of modern-day Ukraine. The trend towards shared consumption among Generation Z is marked through this research, which offers befitting analysis into how Generation Z envisions and attains sustainability in every direction of risk, including war and scarce resources. The research shows that over half of young Ukrainians exhibit an evident drive toward collaborative consumption, stimulated less by environmental concerns, but rather by pragmatism in terms of convenience, money saving, and social affinity. This informs a significant insight—among Generation Z in Ukraine, collaborative consumption takes a less calculated green position and embodies a more pragmatic accommodation to concrete situations. These findings have important policy and research implications, in one respect for theory development by embedding socio-psychological drivers within a sustainable behavior theory, but in another regarding policymakers and companies alike, as infusing confidence, providing ease of use, and developing digital literacies may be smarter objectives than aiming only for environmental dividends. In effect, this study shows, in living detail, the complex intertwinement of consumer motivation, group affiliation, and structural context to demonstrate how a conflict-defined generation rebuilds consumption so that it is adaptive and, therefore, potentially transformative.

2. Background to Research

2.1. Problem Statement

2.1.1. Generation Z

According to Generation Theory (Sociology of Generations), a generation is a group of people of similar age whose members have experienced a noteworthy historical event during a specific period [

8]. The younger generation is characterized by mobility, an openness to other cultures, and a willingness to experiment. This generation prefers teamwork and diversity, avoiding routine and career stability. They are capable of multitasking but often have difficulty concentrating on a single task. Moreover, this generation expects personalization and values experiences more than material possessions, while demonstrating ecological awareness and social responsibility [

9]

The youngest generation—as consumers—is Generation Z. The definition and range of birth years attributed to Generation Z vary depending on the source. However, the most common assumption in research is that Generation Z generally comprises individuals born from 1995 to 2010, a range chosen because of their distinct consumer experiences shaped by new technological developments and socio-economic trends [

10,

11,

12]. Although the term “Generation Z” has no formal basis, it is widely accepted and used. In addition, other names are employed to highlight this age group’s deep ties to new technologies, especially the Internet and mobile devices. These terms include Digital Natives, the iGeneration, Screeners, and the Selfie Generation [

13,

14]. Studies also sometimes use the term “Generation C”, which derives from the word “connected”, thus indicating the group’s constant connection to networks [

14].

Studies on the younger generation’s sustainable consumption behaviors [

15,

16,

17] are increasingly appearing in scientific publications; however, according to the authors of this publication, there is a lack of research on Generation Z’s activity in collaborative consumption. In scientific studies, Millennials (Generation Y) have been examined more frequently than Generation Z. Millennials, the generation born between 1981 and 1999, have been the focus of research on behavior and activity in collaborative consumption by Činjarević et al. [

17], Hume [

18], Hwang and Griffiths [

19], and Godelnik [

20], among others. Researchers emphasize a strong “addiction” to digital mobile devices among both Millennials and Generation Z [

21,

22]. Regarding the research topic of collaborative consumption, the adept handling of phones, tablets, and other mobile devices by young consumers facilitates their participation in the sharing of goods and services.

The characteristics of Generation Z (Gen Z) significantly influence their approach to collaborative consumption. As digital natives, Gen Z seamlessly integrate technology into their lives, making them adept at navigating online platforms that facilitate collaborative consumption. Their sustainability awareness and environmental consciousness drive a preference for eco-friendly practices, aligning well with the resource optimization inherent in collaborative consumption models [

23,

24,

25]. Gen Z’s prioritization of experiences over ownership is a key factor influencing their engagement in collaborative consumption. This generation values the flexibility and convenience offered by sharing economies, as these attributes cater to their dynamic lifestyles and desire for cost-effective solutions. Economic prudence is evident in their cost-conscious mindset, making collaborative consumption an attractive option due to its affordability and shared financial benefits [

26,

27].

Socially connected by nature, Gen Z sees collaborative consumption as an avenue for building communities and fostering connections. Trust in online platforms is crucial for their active participation, with a reliance on transparent reviews and ratings shaping their decisions. The desire for personalized experiences and customization further enhances the appeal of collaborative consumption, aligning with Gen Z’s penchant for individual expression and unique services [

28].

It can be stated that the characteristics of Generation Z—marked by their tech-savviness, sustainability consciousness, valuation of experiences, and social connectivity—render them not only receptive, but also enthusiastic participants in the collaborative consumption landscape. The interplay of these traits shapes their preferences, contributing to the continued growth and evolution of collaborative consumption models within this demographic [

29,

30].

Table 1 presents a comparison of Generation Z characteristics that are especially important for collaborative consumption.

2.1.2. Generation Z in the Consumption Market in Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, Russia waged a full-scale war against Ukraine. According to data from the European Commission (European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations) [

41], it is estimated that by 2025, 5 million people in Ukraine will be at risk of food insecurity, compared to 11.1 million in 2023 and 7.3 million in 2024. The country’s humanitarian needs span various sectors—including water and hygiene, healthcare, shelter, and psychosocial support.

According to the Ukrainian Humanitarian Aid Team, approximately 40% of the population—about 18 million Ukrainians—require material humanitarian aid [

42]. Furthermore, a report by the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner provides additional context regarding the human rights challenges that have emerged during the conflict [

43].

Despite the numerous challenges caused by wartime activities in both the public and private sectors, some sectors continue to function relatively well. For example, rail transport remains extensive, postal services are resilient and responsive to the dynamics of the front, and the National Bank of Ukraine has effectively maintained currency regulation and economic stability. In addition, the service sector (including hotels, restaurants, and shopping malls) has shown significant profitability and adaptability, the IT sector has experienced notable growth during the war, and there is a high capacity to restore energy exports abroad [

42,

44].

“Normal life in abnormal times” in Ukraine is characterized by the constant sound of sirens alerting citizens to air-raid alarms, the visible presence of officers carrying out assignments on the streets, and frequent security checks. At the same time, the activity of offices, public transport, a good supply of high-quality products from Western Europe, and the operation of cafes are observed [

42,

45].

In regions near the active battlefront, living conditions are markedly different. These areas often suffer from recently destroyed civil and energy infrastructure, ongoing debris removal efforts, and acute shortages of essential supplies such as water filters, potable water, power generators, temporary shelters, and field medical care [

42,

46].

Within this complex socio-political and economic context, Ukrainian Generation Z has developed distinct characteristics. One of the key differences is a strong sense of patriotism and national identity. Unlike the global Generation Z, which often prioritizes individualism, young Ukrainians demonstrate exceptional commitment to their country—engaging in informational campaigns on social media, volunteering, and directly assisting in wartime efforts.

A significant amount of Generation Z Ukrainians are now on the front lines defending their homeland, and some have become volunteers. Due to armed aggression from a neighboring country, the younger generation had no choice regarding the possibility of developing individualism and personal development.

For many of this generation, their homeland and its future are a top priority, influencing their decisions regarding education, careers, and migration.

Young Ukrainians have had to mature quicker and develop a greater sense of responsibility for themselves and others. Many young people participate in charity activities and make conscious decisions to stay in the country in order to contribute to its reconstruction. As a result, values such as altruism, solidarity, and a willingness to make sacrifices are more pronounced among them compared to their Western peers.

As Cheryomukhina and Fedorenko [

47] note, in general, you can see that the value of life is being reassessed among young people. Young people have become more appreciative of every minute of life and have become quicker to decide who they want to become and what they want to do in the future.

The war and economic instability also impact young Ukrainians’ approach to financial stability. While the global Generation Z often rejects traditional careers in favor of freelancing and flexible employment, young Ukrainians tend to value professions that provide economic security. The growing interest in the technology, engineering, and medical fields stems from the need for skills that ensure stable employment both in Ukraine and abroad. The professions in demand today among Ukrainian youth can be found in the military, medical, IT, construction, psychological, rehabilitation, social, and logistics sectors [

48].

Mobility and migration represent another area where Ukrainian Generation Z differs from global trends. Although many young Ukrainians seek safety and stability outside the country, their strong sense of patriotism makes migration a temporary solution for many. A significant number express their desire to return and contribute to the country’s rebuilding after the war, distinguishing them from their Western peers, for whom mobility is often associated with seeking a better quality of life [

49,

50].

Separate attention should be paid to the mood among internally displaced persons who already have experience with migration. They, as a rule, do not plan to leave Ukraine. Most of them prefer to stay in place due to family circumstances (men often cannot go abroad), education, work, and negative experiences of being abroad during the war. For many, especially families with children, it is also important not to start building their lives from scratch. Some young people consider migration abroad as a possible option after the war ends, if their whole family can leave. Others might consider this option in the case of increased hostilities or Ukraine losing the war [

51].

Finally, young Ukrainians are distinguished by a high level of civic engagement. Compared to their peers in stable democracies, where activism is often limited to expressing opinions on social media, Ukrainian Generation Z actively participates in public processes. The sense of responsibility for the fate and future of the nation is particularly strong and is a defining element of their identity. Young people are not so much electorally as civically active, and, therefore, their role is growing not only in elections of people in power, but also in public control over elected politicians and the government bodies they have formed. Following global trends, young people are partially removing themselves from politics, while young Ukrainians trust the armed forces of Ukraine the most and help them as much as possible [

52].

2.2. Collaborative Consumption in Literature Review

Collaborative consumption is becoming increasingly appealing to diverse consumer groups within digital societies and economies. This concept lies at the heart of sustainable development initiatives, with a strong emphasis on promoting conscious and resource-efficient consumption that minimizes environmental impact. In contemporary sustainability strategies, policymakers prioritize fostering responsible consumption patterns that align with ecological preservation. In recent years, the sharing economy has emerged as a rapidly expanding and globally pervasive phenomenon, reflecting its growing significance in addressing modern economic and environmental challenges [

53,

54]. According to Benkler [

55], sharing is defined as a nonreciprocal pro-social behavior, and the sharing economy is defined as “an economic system based on sharing underused assets or services, for free or for a fee, directly from individuals” [

56]. The sharing economy is aimed at reusing existing resources and creating more flexible lifestyles. It is an alternative to traditional business and consumerism [

4,

5,

57,

58,

59]. A characteristic of this form of economy is the pursuit of sustainable consumption, which prevents environmental damage, helps people living in poverty, fosters economic unity, promotes flexible lifestyles, and encourages the wise use of resources in communities [

1]. Sharing economies help to create sustainable consumer attitudes. In this context, sustainable consumption entails purchasing more environmentally friendly goods and empowering consumers with data to make choices that reflect their values [

60]. The concept of sharing goods and services fits within sustainable consumption, which takes into account ecological, social, and economic aspects [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65].

Collaborative consumption is becoming increasingly attractive to various groups of consumers in digital societies and economies. It took a long time for people to understand the global slogan enshrined in the concept of sustainable development, “the environment for us and for future generations” [

66]. The recurring economic principle that needs exceed available resources—and that these resources must be managed rationally—is manifested, among other things, in the trend of collaborative consumption. The consumption of shared goods and services creates new consumption models based on sustainable principles, which consider ecological, social, and economic aspects [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65]. Socially conscious consumers may need to forgo products they previously purchased in favor of shared use [

67,

68]. The practice of sharing products (such as hardware, devices, etc.) and services among consumers has become a defining characteristic of modern digital societies [

69,

70,

71]. This trend facilitates easier connections between strangers and enhances social engagement, which positively contributes to societal development. For households to effectively adopt collaborative consumption models, proactive government policies tailored to national, regional, and local contexts are necessary to raise consumer awareness and promote sustainable, socially responsible consumption habits [

67,

68]. Collaborative consumption helps to reduce the negative ecological and social effects of unconscious consumption.

According to a study by Gerlich [

1], collaborative consumption is primarily used for physical goods, secondarily for accommodation, and tertiarily for transportation services. For example, Uber’s online platform enables ride-sharing services at lower fares than traditional taxis, thereby stimulating sustainable transportation solutions [

2,

72]. Another example is the platform Airbnb, which allows tourists to rent private accommodation at lower prices than hotels, aligning with the P2P (peer-to-peer) accommodation sector [

73]. Definitions of collaborative consumption have been cited in recent publications referring to online platforms. The most prominent examples of the collaborative economy include car sharing, renting private accommodation, coordinating the delivery of on-demand services, and fashion sharing [

57,

74].

According to Gerlich [

1], “Collaborative consumption, understood as a system of sharing resources between individuals and service providers via online platforms as an alternative to residential or car rental, is a potentially growing economic trend”. It has recently been confirmed [

75] that consumers worldwide are transitioning to a digital lifestyle. This trend is particularly relevant when searching for and researching products or services. The emphasis on consumer sharing in digital communication structures grew with the popularization of the concept of Industry 4.0 and its refinement in Industry 5.0 [

76]. Today, the importance of ICT for the development of economies and societies is increasing [

70,

75,

76] in line with the goals of sustainable development [

77,

78]. Sustainability, in combination with ICT, is creating conditions for collaborative consumption.

In the context of collaborative consumption, researchers emphasize that ICT and the Internet have improved exchanges and enabled peer-to-peer transactions [

1]. Collaborative consumption is becoming a common form of exchange. It operates within a triangle of actors, as follows: platform providers, reciprocal service providers, and customers. It also functions according to the following three parameters: motive, action, and resource [

1,

79,

80]. Among these motives are both internal and external factors. In their study, García-Rodríguez et al. [

59] found that reciprocal motivation in this economy is mediated by social norms and responsible behavior. The importance of social norms was also emphasized by Huang et al. [

81]. In collaborative consumption, individuals’ behavior results from both self-interest and a sense of interdependence [

82]. In addition to social norms, economic factors and the utilitarian aspects of social exchange also motivate collaborative consumption [

54].

Consumers’ increasing access to the Internet, social networks, modern mobile devices, and online payment systems enables them to take initiative in collaborative consumption. Mobile computing solutions are being increasingly integrated with networks. Consumers’ mobile devices are in constant communication with the Internet, so a consumer who is looking for a particular piece of equipment but is not interested in purchasing it may search online for someone willing to lend this equipment or provide a service. Information posted on the profiles of individuals participating in exchanges or platforms facilitates searchers’ access to products that people are willing to share. Many countries have exchange platforms, for example, platforms for providing pet care, for swapping expensive electronic equipment, Spinlister (for renting bicycles, surfboards, or snowboards), for exchanging prepared food, a WiFi connection sharing network, platforms for exchanging work, car sharing, etc. Convenience is a key driving force, as collaborative consumption platforms offer easy and efficient access to a wide range of goods and services. Users value streamlined processes and the elimination of logistical challenges and maintenance responsibilities associated with ownership [

83]. The allure of variety and novelty attracts users to collaborative consumption. The diverse range of experiences and products available on these platforms keeps users engaged and excited, contributing to the overall appeal of shared consumption models [

84]. Thus, collaborative consumption is deeply rooted in the Internet age [

66,

85,

86,

87]. However, doubts remain regarding the impact of product personalization on sustainable consumption [

88]. It is difficult to weigh up the pros and cons of consumer access to ICT and digital networks.

There are various motivators for engaging in collaborative consumption [

89]. Daglis [

90] defined collaborative consumption as a new form of economic activity characterized primarily by the exchange of residual resources among equals. In this definition, in addition to environmental motivations, economic factors are also important. One significant motivator is cost savings, as users are attracted to the financial benefits of collaborative consumption, opting to share, rent, or access goods and services at a lower cost compared to traditional ownership [

91]. Environmental consciousness is another compelling motivator, as individuals express a commitment to sustainability. Participating in collaborative consumption allows users to contribute to environmental conservation by reducing resource consumption and minimizing waste, in line with the growing global awareness of ecological responsibility [

92,

93].

Access over ownership is a transformative motivator, reflecting a shift in consumer preferences. Users appreciate the convenience of on-demand access without the long-term commitments and responsibilities associated with ownership [

93]. This motivator resonates with those seeking flexibility and a reduced environmental impact. Social connection also plays a pivotal role in collaborative consumption [

94]. Beyond the transactional aspect, users are motivated by the opportunity to connect with others in their community. Shared consumption fosters a sense of community, trust, and cooperation, enriching the overall user experience [

95].

Trust and reputation are critical motivators. Users place a premium on the reliability of platforms and the reputation of fellow participants. Transparent systems, positive reviews, and ratings contribute to building trust within the collaborative consumption community [

96].

Sustainable practices continue to serve as a guiding motivator. Users are drawn to platforms that prioritize ethical and sustainable approaches to consumption. The opportunity to be part of a more responsible and environmentally conscious way of living drives participation in collaborative consumption. Technological innovation is another significant motivator, enhancing the user experience within collaborative consumption platforms. The seamless integration of technology facilitates transactions, communication, and overall accessibility, thereby contributing to the efficiency and appeal of shared consumption models [

97]. Flexibility and mobility round out the list of motivators, allowing users to adapt to changing needs. Collaborative consumption provides the freedom to access goods and services as needed, promoting a dynamic and user-centric approach to consumption in an ever-evolving societal landscape [

98].

Table 2 provides a description of the main motivators of collaborative consumption.

Motivators can be different for different people. People vary, so among the many collective motivators are individual motivators [

111]. The individual characteristics of consumers, if reproducible, form consumer group or social profiles. This creates individual group motivator categories. Group motivator categories can be related to particular age groups in society. Young people, it can be assumed, are more inclined to participate in collaborative consumption because they are more strongly connected to digital networks.

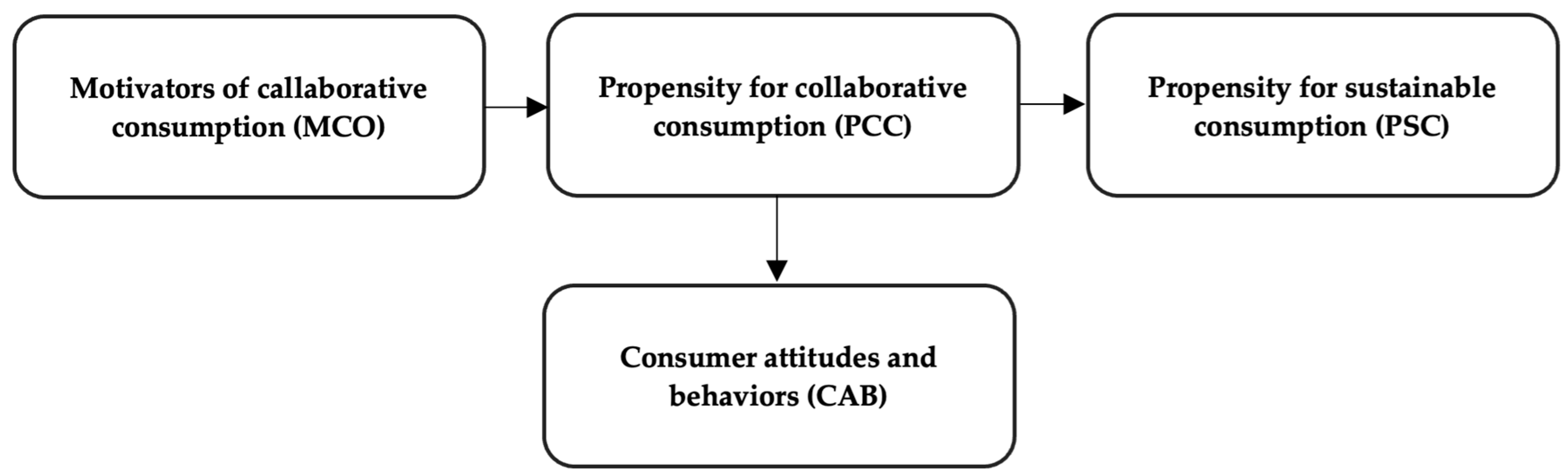

The literature review conducted on collaborative and sustainable consumption theory enabled the development of a conceptual model for research aimed at identifying the phenomenon of collaborative consumption and its significance for sustainable consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine. The research process was divided into the following nine stages: (1) conducting a secondary source analysis, (2) identifying the research gap, (3) formulating the research questions, (4) developing a conceptual research framework, (5) formulating research hypotheses, (6) preparing survey questions, (7) conducting pilot and field studies, (8) preparing the data for analysis, and (9) analyzing the data.

Based on the literature review, a research model was proposed, as shown in

Figure 1.

The Consumer Attitudes and Behaviors (CAB) construct was based on the following theories: (1) Simon’s Theory of Rational Consumer Decision-Making. Adaptations were made of the scales published in [

112], (2) Theory of Planned Behavior [

113,

114], and (3) Stern’s Theory of Environmental Behaviors. An adaptation was made of the pro-environmental Behavior (PEB) scale [

115]. The construct contains the following variables:

CAB_1 I complete my tasks ahead of time vs. I do everything at the last minute.

CAB_2 I easily establish contacts with other people vs. I have difficulty establishing contacts with other people.

CAB_3 I am willing to use items borrowed from others vs. I do not like to use items borrowed from others.

CAB_4 I take care of my physical fitness and regularly exercise vs. I do not take care of my physical fitness.

CAB_5 I make decisions based on rational criteria vs. I make decisions depending on the situation.

CAB_6 I worry about what other people think of me vs. I do not worry about what other people think of me.

CAB_7 I adapt to changes easily vs. I am reluctant to accept any changes.

CAB_8 I prefer to use new items vs. I prefer to use items already used by others.

CAB_9 I care about the natural environment (e.g., saving energy, water, and recycling) vs. I do not care about the natural environment.

CAB_10 I am willing to lend my belongings to others vs. I never lend my belongings to others.

CAB_11 I like to keep up with current trends and fashion vs. I am not interested in new trends on the market.

CAB_12 Having access to a product is enough for me vs. I prefer to own products.

The PCC construct was based on Collaborative Consumption Theory by Botsman and Rogers [

116]. An adaptation was made of the Attitude Toward Sharing scale published in [

102]. The construct contains the following variables:

PCC_1 I like to use things borrowed from other people.

PCC_2 I like to use things that have already been used by others.

PCC_3 I gladly lend my things to other people.

PCC_4 Access to the product is enough for me.

The PSC construct was grounded in the theories of Sustainable Consumption and Environmental Consumption, with measurement scales adapted from [

87,

117]. The construct contains the following variables:

PSC_1 It is important for me to reduce my own consumption.

PSC_2 It is important for me to reduce CO2 emissions.

PSC_3 It is important for me to participate in a broader movement opposing excessive consumption.

PSC_4 It is important for me to produce less electronic waste as possible.

Consumer attitudes and behaviors, as well as people’s propensity toward collaborative and sustainable consumption, are influenced by their personality traits. The study utilized a personality traits scale derived from Costa and McCrae’s Big Five theory [

118]. The measurement results enabled the characterization of a segment of young Generation Z consumers from Ukraine who exhibit a tendency toward collaborative consumption (results in

Section 4.1). Additionally, consumer personality traits determine their motivation for engaging in collaborative consumption activities. The operationalization of the MCC construct is presented in

Table 3. Scales for measuring the motives behind engaging in collaborative consumption (MCC) were adapted from [

87,

102,

117,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123].

Based on in-depth research studies in the field of collaborative and sustainable consumption measurement theory, the following research hypotheses (H) were formulated:

H1. The greatest impact on the propensity for collaborative consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine is exerted by motivators related to environmental awareness (M2) and sustainable practices (M8).

H2. The propensity for collaborative consumption differentiates the attitudes and behaviors of Generation Z in Ukraine.

H3. The higher the propensity for collaborative consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine, the greater their propensity for sustainable consumption.

3. Materials and Methods

For the purposes of this study, a questionnaire was developed. The research questionnaire contained items addressing consumer characteristics, attitudes, behaviors, and propensity for collaborative consumption, as well as items pertaining to personality traits and aspects related to collaborative consumption, including its drivers, which are presented in

Section 2.2. The questionnaire utilized various measurement scales, including nominal, ordinal, interval, and unipolar scales. To assess consumers’ personality traits, a scoring system ranging from 1 to 7 was used, with a score closer to 1 indicating a negative intensity of the personality trait. When analyzing the propensity for collaborative consumption, a closed dichotomous scale was employed, requiring respondents to choose between two opposing consumer attitudes and behaviors. In contrast, aspects related to collaborative consumption were measured on a seven-point Likert scale (ranging from “strongly unimportant” to “strongly important”).

The questionnaire was developed iteratively on the Webankieta.pl platform (

www.webankieta.pl, accessed on 6 May 2025) in the Ukrainian language. At the beginning of the questionnaire, the subject and purpose of the study were clearly stated. Additionally, in accordance with the principles of direct research ethics, participants were provided with a statement regarding the anonymity and confidentiality of the study. By completing the questionnaire, participants consented to take part in the research.

The study was conducted using the CAWI method (Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing), a computer-assisted online survey technique that allows respondents to complete a questionnaire independently using a computer or mobile device. The CAWI method has been utilized in numerous studies on consumer behavior and collaborative consumption [

124,

125,

126,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131]. Data collection took place from February to April 2024. Prior to the main study, a pilot test of the research instrument was conducted among a group of 20 Ukrainian students studying in Poland. The pilot aimed to verify the accuracy of the Ukrainian language, the clarity of the questions, and the logical consistency of the questionnaire.

The main study was subsequently carried out in Ukraine (Ivano-Frankivsk). The survey link was distributed via email to a purposively selected group of young Generation Z consumers who are Ukrainian citizens. Respondents were selected using non-random sampling. Over 400 respondents participated in the study; after analyzing the completed questionnaires, 292 fully completed questionnaires qualified for further analysis. The filled questionnaires were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistical Package 29.0.2.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

In the research sample, 51.4% were women and 48.6% were men. The respondents were aged between 18 and 24 years, with 19-year-olds constituting the largest group, accounting for 26.7% of the sample. The mean age of the respondents was 20 years. In terms of employment, over half of the respondents reported being employed. Among the non-working group, which comprised 46.6% of the sample, the primary sources of income were scholarships (26.7%) and pocket money from parents (18.5%). The household structures from which the respondents originated were diverse. The largest proportion (29.5%) came from households with five or more members, while 7.5% lived alone. Nearly 22% of the respondents resided in three- or four-person households, with slightly fewer (18.5%) residing in two-person households. Almost half of the respondents lived with their parents in an apartment or house, one in every five resided in a dormitory, and one in every six rented an apartment or room (with apartments being rented significantly more often). Only 12.3% of respondents owned their own apartment. An assessment of the respondents’ material situations revealed that nearly 46.0% of the study participants evaluated their situation as “very good” or “good”, 36% considered it “satisfactory”, while 18.2% rated their situation as “bad” or “very bad” (

Table 4).

Based on the research conducted, the respondents were classified according to their propensity for collaborative consumption. The segmentation process utilized a set of binary behavioral variables that measured the respondents’ attitudes toward key aspects of shared consumption, such as their willingness to use borrowed items, preferences for new versus used products, willingness to lend personal belongings to others, and preferences for ownership versus access to products. This approach enabled the precise identification of a group of consumers who prefer resource sharing over individual ownership, which is of significant importance for further analyses in the article.

The given mathematical formulation represents a model for measuring an individual’s propensity for collaborative consumption (

PCC) based on four key behavioral indicators. The equation is defined as follows:

where

PCC is the propensity for collaborative consumption and

xn represents four behavioral variables related to attitudes toward shared consumption practices. Each variable is binary (

), capturing either a preference for personal ownership and exclusivity or an openness to shared use and access-based consumption. Each of the four components of the summation corresponds to a distinct aspect of collaborative consumption behavior, as follows:

The range of PCC is from 0 to 4, where the following applies:

PCC = 0 indicates a strong preference for ownership and avoiding sharing,

PCC = 4 indicates a high openness to collaborative consumption,

Respondents from Generation Z with an index of were classified into the segment of individuals inclined toward collaborative consumption (PCC), while those with an index of were classified into the segment of individuals not inclined toward collaborative consumption (NPCC).

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Consumer Segments Inclined and Not Inclined Toward Collaborative Consumption

Data analysis enabled the identification and characterization of a segment of consumers demonstrating a propensity for collaborative consumption (PCC). Consumers inclined toward collaborative consumption constituted 54.8% of the total sample. This group comprised more men than women, and the predominant age category was 18–21 years (72.6%). An important aspect of the analysis was the household structure of the respondents. As many as 78.8% of respondents inclined toward collaborative consumption lived in households of three or more members, which may indicate a natural tendency to share resources such as living space or consumer goods. Furthermore, the vast majority of respondents in this segment did not own their own apartment—55.0% lived with their parents, 18.8% resided in dormitories, and 15.0% rented an apartment. This implies that approximately 33.8% of the respondents were in a situation that required sharing living space with others (e.g., in a dormitory or a shared apartment). In terms of employment, 53.7% of the respondents reported being employed, while 46.7% remained unemployed. Among those who were not professionally active, the most common sources of income were scholarships (28.7%) and financial support from family (9.0%). The limited financial resources of this group may foster a greater propensity for collaborative consumption, as such practices help to minimize the costs associated with using goods and services. Self-assessment of their financial situation indicated that 43.8% of the respondents inclined toward collaborative consumption evaluated their situation as “good” or “very good”, whereas 40.0% considered it to be sufficient.

The study also identified the personality traits of Generation Z consumers who exhibit a propensity for collaborative consumption. Individuals in this segment are characterized by specific traits that facilitate participation in collaborative consumption. Among the Generation Z respondents inclined toward collaborative consumption, 85.1% described themselves as loyal and 73.8% as open. These high levels of loyalty and openness suggest that these respondents are predisposed to more frequent use of the same platforms and to building long-term relationships in the context of sharing goods and services. At the same time, their openness may encourage the exploration of new models of collaborative consumption. Generation Z respondents also exhibited moderate levels of trust in others (62.5%) and a propensity to engage in altruistic actions for the benefit of others (60.0%). This fosters the establishment and maintenance of collaborative relationships in the sharing of goods and services. Moreover, more than half of the respondents inclined toward collaborative consumption demonstrated high levels of innovativeness (56.3%), assertiveness (55.1%), and frugality (55.1%). Representatives of this segment are more likely to adopt modern solutions for collaborative consumption, to express their needs and opinions regarding the conditions of sharing, and to seek ways to manage goods and services rationally (

Table 5).

Generation Z respondents identified as inclined toward collaborative consumption exhibit specific attitudes and behaviors. Their dominant characteristic is concern for the natural environment (87.5%). The majority of these individuals easily establish connections with others (73.8%). A substantial portion of this group also demonstrate a high level of adaptability to change (68.8%) and regularly take care of their physical fitness by engaging in sports (67.5%). Nearly two-thirds of the respondents make decisions based on situational context (66.3%) and complete their tasks ahead of deadlines (63.7%). Over half of them are interested in current trends and fashion (57.5%) and do not worry about others’ opinions (53.8%). While they value individualism, they remain aware of prevailing social trends. These findings indicate a cohesive profile of Generation Z consumers identified as PCC, combining openness, self-discipline, and environmental awareness.

The analyzed segment of Generation Z consumers not inclined toward collaborative consumption (NPCC), accounting for 45.2% of the total sample, exhibits somewhat different demographic, economic, and personality traits. In this segment, more than half are men (55.3%). The largest age category comprises those aged 18–19 (48.5%), including 19-year-olds, who make up 31.8% of the entire group. The respondents generally come from smaller households—12.1% are from single-person households, 13.6% from two-person households, and 25.8% from three-person households. Regarding place of residence, a substantial percentage of this group still live with their parents (40.9%), although 27.3% live in dormitories and 15.2% own their own homes. An analysis of their employment status shows that 47.0% are unemployed, with 22.7% relying on pocket money from parents and 24.2% depending on scholarships. Almost half of the respondents (47.0%) rate their material situation as “good”, while 20.4% consider it “bad” or “very bad”.

Generation Z consumers who are not inclined toward collaborative consumption demonstrate traits typical of their generation, such as openness (66.7%), resourcefulness (57.6%), assertiveness (36.4%), innovativeness (42.5%), and moderate loyalty (59.1%). However, they show lower tendencies to help others and a limited level of trust. As many as 19.7% of respondents report a lack of altruism, and nearly 30% cannot definitively describe their stance on this issue. With regard to social trust, 25.8% of respondents state that they do not trust others, and an additional 19.7% display a rather low level of trust. Furthermore, 18.2% are unable to clarify their position on the matter, suggesting uncertainty or detachment from social relationships.

To verify Hypothesis H2—which posits that the propensity for collaborative consumption differentiates the attitudes and behaviors of Generation Z in Ukraine—a Mann–Whitney U test for independent samples was performed, using the propensity for collaborative consumption as the grouping variable (

Table 6). The analysis revealed that both the PCC group and the NPCC group exhibit similar consumer attitudes and behaviors. They tend to complete tasks ahead of deadlines rather than at the last moment, easily establish contacts with others, prioritize physical fitness, and make decisions depending on situational context. They also tend not to be concerned about others’ opinions and adapt readily to change. In both groups, the majority of individuals declare that they care about the natural environment and strive to keep up with current trends and fashion.

Statistically significant differences in the attitudes and behaviors of Ukrainian Generation Z across the two groups emerge in areas particularly relevant to collaborative consumption. These include using borrowed items, lending items to others, using second-hand goods, and utilizing items without owning them outright.

In order to verify Hypothesis H3—stating that the higher the propensity for collaborative consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine, the greater their propensity for sustainable consumption—a Mann–Whitney U test for independent samples was performed, using the propensity for collaborative consumption as the grouping variable (

Table 7). The analysis indicated that the propensity for sustainable consumption does not differ significantly between the PCC and NPCC groups. Therefore, it should be assumed that manifestations of sustainable consumption, such as reducing one’s own consumption, lowering CO

2 emissions, decreasing the amount of electronic waste generated, and broadly opposing excessive global consumption, are important to young people from Generation Z regardless of whether they are inclined toward collaborative consumption or not.

4.2. Collaborative Consumption Motivators Among Generation Z in Ukraine

In search of answers to questions about what motivates collaborative consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine and which factors have the greatest impact on collaborative consumption, the intensity or importance of each motivator (from M1 to M9) was analyzed. A seven-point Likert scale—ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”—was used for the variables measuring the respondents’ attitudes; a seven-point intensity scale was applied to variables measuring personality traits conducive to sharing products; and a nominal, dichotomous (binary) scale was employed for variables measuring behaviors that identify Generation Z’s propensity toward collaborative consumption. In order to analyze the importance of collaborative consumption motivators among Generation Z in Ukraine, the presence of each motivator was identified for every respondent. It was assumed that selected ratings of five, six, or seven on a seven-point scale represented a positive high intensity of the trait or attitude related to the propensity for collaborative consumption; in other words, these ratings indicate that the given factor serves as a motivator for engaging in the sharing of products and services. The frequency of occurrence for each motivator was tallied within the studied Generation Z group identified as PCC. The values were then ranked from highest to lowest, revealing the relative importance of the individual motivators to the respondents. The results are presented in

Figure 2.

Based on the ranking of collaborative consumption motivators among Generation Z in Ukraine shown in

Figure 2, convenience (M5) emerges as the most important factor. Ninety percent of the young Ukrainian Generation Z respondents value easy and quick access to goods and services above all else, unencumbered by the logistical and maintenance challenges associated with owning these products.

The second major motivator for engaging in collaborative consumption is the development of social bonds (M4). The collective ownership and use of goods and services address the younger generation’s pronounced need for building relationships and experiencing a sense of community in collaboration-based models. More than 70% of the Ukrainian Generation Z respondents also highlight a desire for social interactions and community-building through participation in collaborative consumption, which fosters a sense of sharing and trust within their communities.

Environmental awareness (M2) ranks third among the collaborative consumption motivators. Caring for the natural environment and reducing resource waste are highly important to 68% of the respondents. These individuals are driven by a commitment to sustainable development, aiming to lower their resource consumption, minimize waste production, and reduce their environmental footprint by participating in collaboration-based consumption models. A similar level of importance is attributed to motivator M6, which reflects the need for varied experiences and the desire among young people to try new products and services.

For nearly 60% of the respondents, trust and reputation (M7) serve as a motivator for collaborative consumption. Their personal traits (e.g., trustfulness) and attitudes toward others’ opinions (“I don’t worry about what other people think”) underscore the importance of trust that develops among those who collectively use products and services.

For over 56% of the respondents, saving money (M1), flexibility and mobility (M10), and technological innovation (M9) act as motivations for collaborative consumption. Although the financial benefits gained through collaborative consumption remain significant, they are not the primary motivation among Generation Z in Ukraine. Similarly, technological advancements that streamline the sharing process are not decisive factors in this group’s willingness to use sharing economy platforms. Moreover, the desire for immediate access to certain products is not a key motivator in this context.

Among the examined motivators, M8 (sustainable practices) and M3 (access through ownership) hold the least importance. While this relatively low inclination toward responsible consumption and the adoption of responsible or sustainable consumption practices may seem surprising in light of the high placement of environmental awareness, it indicates that a “pro-environmental mindset” is more important to the respondents than the specific implementation of sustainable development practices. Nonetheless, half of the Ukrainian Generation Z respondents regard sustainable practices and access through ownership as motivators for collaborative consumption. This result suggests that matters of “ownership or rental” are less critical for Ukrainian Generation Z than, for instance, convenience or opportunities for social interaction.

Overall, convenience, community spirit, and environmental concern emerge as top priorities, while strictly financial and formal aspects (ownership status and specific sustainable practices) rank lower in the motivation hierarchy for product-sharing. Therefore, Hypothesis H1, which posits that the most significant influence on the propensity for collaborative consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine stems from environmental awareness (M2) and sustainable practices (M8), was not confirmed. While environmental awareness ranks relatively high (third place), sustainable practices have decidedly less importance among the complete set of motivators.

5. Discussion

The results of this study present meaningful insights into the collaborative consumption behavior of Generation Z in Ukraine, emphasizing the main trends of consumer behavior, motives, and segmentations within this age group. The findings of the study show that collaborative consumption is becoming increasingly popular among young consumers, people who tend to be concerned about the environment, social networking, and prices. This research contributes to the broader discussion on sustainable consumption through an empirical assessment of how collaborative consumption fits with the values and lifestyle preferences of Generation Z. The key finding is that the majority of the respondents demonstrate a disposition toward collaborative consumption. This predisposition is strong among those without personal property, typically living in shared accommodation such as student dormitories or rented apartments. These living conditions naturally foster a resource-sharing ethos and, hence, a considerable degree of congruence with the principles of collaborative consumption. Also, the disposable financial resources that most young people have, together with their goal of optimal spending, further encourage the preference for mere access to goods and services over ownership.

The findings also point toward an interesting relationship between a propensity for collaborative consumption and certain personality traits. Open, loyal, and innovative people are more willing to share goods and services. People with high levels of social trust and high altruism tend to be more engaged in sharing economy activities. The above discussion demonstrates personal disposition as playing an important influential factor in consumer behavior within collaborative consumption. Conversely, individuals who are more self-reliant and skeptical about sharing their possessions with others are less likely to engage in collaborative consumption, underscoring the importance of trust-building mechanisms within sharing platforms.

Statistical analyses confirm that attitudes toward shared consumption diverge significantly between those who actively participate in collaborative consumption (PCC) and those who prefer traditional ownership (NPCC). More precisely, PCC people are very likely to use secondhand products, lend their belongings to others, and access goods without having to own them. Thus, this evidence supports the emerging consumption preference of Generation Z for access over ownership in consumption, enabled by digital platforms and mobile technologies.

Among all factors, economic and environmental motivations turn out to be the strongest drivers of collaborative consumption. Saving money is one of the major factors, since consumers view shared consumption as a good way of decreasing expenses related to the acquisition and maintenance of products. In addition, environmental awareness is an important factor that influences attitudes toward shared consumption. Ecologically sensitive respondents seek to avoid waste and minimize their carbon emissions, behaviors which are in line with sustainable consumption.

The findings also reveal that even though Generation Z in Ukraine is very much engaged with collaborative consumption, this does not automatically translate into greater intentions toward sustainable consumption in other spheres. The PCC and NPCC groups do not differ much in their reported levels of sustainable behaviors, as confirmed by statistical tests. This implies that collaborative consumption is viewed mainly as a pragmatic and effective alternative, rather than one that is consciously directed toward environmental sustainability. In the future, how collaborative consumption platforms can best meaningfully embed messages about sustainability to induce long-term changes in behavior could be an area of research.

Practically, businesses and policymakers should consider these insights while addressing Generation Z consumers. Companies in the sharing economy should focus on measures that will help gain consumer confidence, such as transparent user reviews and secure methods of payment. Marketing campaigns also need to reinforce the dual-value proposition of cost savings and environmental sustainability to resonate with the core values of this demographic segment. Policymakers can support collaborative consumption by implementing regulations that allow for innovation in the sharing economy while protecting consumers.

The results of this study can be effectively analyzed from the point of view of Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which posits that human motivation is driven by the following three fundamental psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness [

126,

127]. These needs influence individuals’ behavior and engagement in various activities, including consumption choices [

132]. In the context of collaborative consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine, these psychological needs take center stage to explain collaborative consumption propensity.

The core needs suggested by SDT include autonomy, which can manifest as a preference among members of Generation Z for access-based consumption instead of traditional ownership. There is also evidence that 54.8% of the respondents are characterized by a high PCC and, hence, prefer to enjoy flexibility and freedom in making their consumption choices. This SDT perspective shows that people strive to experience volition regarding their decisions [

133,

134]. Without committing to long-term ownership, members of the PCC group are willing to borrow and share products, especially those from product categories that one does not need to permanently keep. The fact that 66.3% of the PCC respondents report preferring to use second-hand items corroborates the shift away from consumerism toward access-based solutions for reasons of autonomy. With this in mind, enabling young Ukrainian consumers to make certain choices about the consumption patterns that best fit their lifestyle, rather than limiting them to ownership, is what matters.

Competence in SDT means the extent of capability or efficacy one experiences in interacting with the environment; this is can be seen in how digital platforms are being increasingly embraced to enable collaborative consumption among members of Generation Z. Most of the participants in this research use active digital sharing platforms by embracing technological advancement to complement the best usage of resources. Those in the PCC group show a greater facility with technology, as 73.8% identify themselves as being open and innovative, embracing their ability to navigate digital ecosystems. From this, one can assess the competence of individuals through their efficiency in interacting or dealing with peer-to-peer sharing platforms. This is consistent with SDT’s contention that people are more likely to engage in an activity if they feel capable and effective in performing it—again, here, realizing one’s personal goals of convenience, affordability, and resource efficiency [

135,

136].

Thirdly, relatedness, the third psychological need in SDT [

137], provides an important reason for why collaborative consumption appeals so much to young consumers. This research shows that 78.8% of the PCC respondents live in households with three or more members, which could naturally influence the development of resource-sharing habits. Furthermore, 85.1% of the PCC respondents describe themselves as being loyal and 73.8% as being open to others, which indicates that social bonding is an important aspect in their consumption decisions. Sharing products, services, or accommodation gives one the feeling of fitting in, nurturing SDT’s idea of human beings as having an inherent desire for meaningful interaction with others. The results, however, mean that social connections and trust cannot be overlooked as factors in collaborative consumption. Surprisingly, 62.5% of respondents show moderate to high levels of distrust in others—the necessary ingredient claimed by sharing models of economic exchanges.

Economic considerations also magnify the role of SDT’s motivational framework [

138,

139,

140]. While autonomy motivates people to seek affordable options for access over ownership and competence allows them to manage digital consumption environments, relatedness increases their motivation to share access to resources within their communities. Employment is reported as the main source of income by 53.4% of the PCC respondents, scholarships by 28.7%, and financial support from their families by 9.0%. Since a large number of the respondents are economically limited, collaborative consumption is an option that satisfies their economic needs as well as psychological needs for autonomy and relatedness.

The first evidence supporting SDT is the coherence between environmental awareness and collaborative consumption. In the PCC group, 87.5% of the respondents are actively concerned with the environment and 40.0% want to reduce their ecological footprint. While environmental concerns might not be the main motivator for all participants, the overlap between the values of sustainability and shared consumption shows that relatedness extends beyond social contact—it also comprises connectedness with general societal and environmental goals. This is in line with the basic tenet of SDT, stating that behaviors supporting intrinsic values are likely to be internalized as part of the self [

141,

142].

The NPCC group represents 45.2% of the sample and shows lower levels of relatedness and openness to shared economic models. This group has lower levels of trust, with 25.8% claiming not to trust others and a fair number describing themselves as more self-sufficient and traditional in their consumption habits. They show a greater desire to focus on ownership and personal control over resources, which suggests that their psychological needs for autonomy and competence are better satisfied through personal possession than through shared access.

The contribution of this research is placing collaborative consumption in the context of a war-torn society and widespread socio-economic dislocation. While earlier research established that Generation Z tends towards collaborative consumption due to digital literacy, ecologism, and a preference for access over ownership [

23,

67], in this article, other distinguishing features among the young people of Ukraine, such as a greater sense of patriotism, social responsibility, and an aspiration for economic resilience, are discussed. In contrast to their Western peers, who tend to see sharing as a form of sustainability and lifestyle flexibility [

17,

54], young people in Ukraine appear to perceive collaborative consumption not only as an environmentally friendly practice, but also as a utilitarian solution to resource shortages and a reflection of social values grounded in national solidarity.

One aspect of the findings is the attainment of sustainability through collaborative consumption. As much as earlier research—such as that by García-Rodríguez [

59] and Camilleri [

6]—indicated that environmental reasons and sustainable behaviors were the pivots of the sharing economy, this research establishes a partial disconnect. Environmental awareness is a mandatory driver for Generation Z in Ukraine, but some sustainable behaviors (e.g., reducing consumption or e-waste) are lesser priorities. This finding is contrary to the prediction that environmental motivations are equally as strong in promoting cooperative consumption and suggests that, in this population, ecological concerns are more value-related than behaviorally integrated. Thus, our research contributes to the literature by distinguishing between environmental consciousness as a value and its expression through tangible sustainable behavior.

Recommendations for improving collaborative consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine include the following:

AI-driven user-friendly mobile apps with recommendations and safe online payments will definitely enhance the user experience. Develop trust through transparency in reviews, identity verification, and clear dispute resolution mechanisms that encourage greater engagement in collaborative consumption.

Introduce flexible pricing models, pay-per-use options, and subscription-based services to attract cost-conscious young consumers. Give discounts and special packages to students and young professionals.

Marketing campaigns should focus on the benefits of sustainability that come with collaborative consumption by emphasizing reduced levels of waste and efficiency in resource use. Engage educational institutions and government agencies to support awareness campaigns about responsible consumption.

Improve logistics by multiplying pick-up/drop-off points, integrated with contactless delivery options. AI-enabled inventory management ensures product availability while optimizing supply and demand in the sharing economy.

Loyalty programs, user events, and referral systems developed on the basis of community will encourage participation. Nurture a sense of membership that fosters user interactions, shared experiences, and peer-to-peer engagement in digital sharing platforms.

6. Conclusions

The sharing consumption segment of Ukrainian members of Generation Z is represented by 54.8% of the total respondents under consideration. This figure is based on the CAWI structured questionnaire survey of 292 young Ukrainians aged between 18 and 24 years conducted in 2024. Respondents in this cluster are more likely to share and consume jointly owned goods and services because they have a more open behavioral attitude towards access-based consumption over ownership. This research stresses that this development is necessitated more by practical motives than by ecological consciousness—above all, convenience, social closeness, and economic considerations. The information reveals that shared consumption is perceived more as a naturalized, sustainable way of life than an adaptive option to deal with the social, economic, and infrastructural realities within the specific geopolitical situation of post-Soviet Ukraine (RQ1).

Hence, this surveyed segment tends to be more tolerant, loyal, and creative, with a pressing desire to socialize and adopt low-cost, multi-purpose solutions. Its members reside primarily in multi-person households—frequently living with parents or in flat-sharing accommodation—the very nature of which encourages the sharing of resources. They are environmentally friendly, physically active, and socially active, following an access-not-own pattern of consumption. On the other hand, the less collaborative-consumption-prone segment (NPCC), representing 45.2% of the sample, is defined by comparatively lower trust and altruism and greater preferences for ownership and autonomy. This segment, while still socially connected and digitally active, is less engaged in communal or sharing-based economic structures and more engaged in conventional modes of consumption, reflecting a lower openness to emerging, collaborative approaches to consumption (RQ2).

The study depicts the fact that although there are some shared generic consumer inclinations among both segments, namely the PCC and NPCC groups, of Ukrainian Generation Z—such as green concerns, adaptability, and fashion consciousness—statistically significant differences exist only pertaining to behavior concerning sharing practices. Individuals in the PCC group are likely to consume second-hand or borrowed goods, share products of their own, and provide access instead of ownership, echoing a more open and integrated social model of consumption. NPCC consumers are far more possessive about ownership and less willing and open to sharing usage. Thus, though the two groups are proximate in certain overall lifestyle values, they vary in terms of specific behavior and decisions that shape their attitude towards collaborative consumption (RQ3).

To Ukrainian Generation Z focused on collaborative consumption (PCC), the primary driving forces are pragmatic and social, rather than environmental. Convenience is the strongest driver—valuable to 90% of respondents—since collaborative consumption offers the easy and immediate availability of products and services without possession. The second-most important motivator is the need for social connection, with more than 70% of the respondents saying that shared consumption meets their desire to form relationships and be a part of community-like experiences. Environmental concern is also a strong, albeit secondary, factor for 68% of this segment, implying a sustainability concern that informs but does not dictate their choice. Other inspiring drivers are the search for experiences, dependency on electronic media, and frugality. This would imply that PCC consumers are inspired by a mix of lifestyle convenience, relational belonging, and low ecological concern rather than an ideological devotion to sustainability (RQ4).

This research proves irrefutably that convenience is the most powerful stimulus of the propensity towards collaborative consumption among Ukrainian Generation Z. For 90% of the respondents from the PCC segment, convenience and the simple availability of products and services—without the burden that ownership carries with it—are the most attractive factors that drive participation in the sharing economy. This is a realistic solution to present-day, time-constrained lifestyles, as well as the limited monetary means common among young people. Though environmentalism and a need for sociability are also significant drivers, the functional and logistical convenience offered by collaborative consumption platforms predetermines usage most strongly. This underlines the essentially pragmatic outlook of young Ukrainian people towards collaborative consumption activities (RQ5).

The findings of this research show that the inclination for collaborative consumption does not have a significant effect on the inclination for sustainable consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine. Although more than half of the participants were willing to share products and services collaboratively, statistical analysis revealed no PCC vs. NPCC group differences among fundamental sustainable behaviors—be it reducing individual consumption, CO2 footprint, or electronic waste. This implies that, although collaborative consumption is practiced by many young Ukrainians, it is driven more by convenience, economic sensibility, and social issues than by a consciously pro-environmental agenda. In other words, collaborative consumption here is a pragmatic lifestyle choice and not always a direct extension of ecological commitment (RQ6).

The main scientific objective of this paper is to understand the nature and extent of collaborative consumption among Generation Z in Ukraine, especially with regard to their attitudes, behaviors, and motivations. Young consumers, being digital natives and deeply integrated into online platforms and social networks, are increasingly engaging in product-sharing practices rather than traditional ownership. To date, however, determining the precise drivers and deterrents influencing the consumption of this demographic in the sharing economy, along with exactly how their consumptive lifestyles align with the principles of sustainability, economic pragmatism, and social engagement, remains the main challenge.

The paper tries to fill this literature gap by providing empirical evidence on how Generation Z in Ukraine perceives and practices collaborative consumption, what factors drive or hinder the propensity of Generation Z to share products, and how these behaviors fit within the broader framework of sustainable consumption. It also evaluates the impacts of economic conditions, social trust, and technological development on product-sharing trends in Ukraine, hence providing useful insights for businesses, policymakers, and researchers interested in the optimization of the sharing economy. The paper contributes to the theoretical understanding of collaborative consumption and its implications for consumer behavior in the context of an emerging digital and sustainability-driven market.

One of the study’s limitations emanates from the narrow scale of the demography explored, Generation Z in Ukraine, allowing for only limited generalization to older age groups or those living in different cultural contexts. The study gives valuable insights into the behavior of young consumers regarding collaborative consumption, but does not take into consideration generational differences or the influence of other consumer segments who might be older and engage in product-sharing practices in their own way. Another limitation is methodological—the research relies on self-reported data from questionnaires, which can be subject to social desirability bias or inaccuracy in self-assessment by the respondents. The study is also conducted within a certain period and under particular socio-economic conditions, including the ongoing war in Ukraine, which may impact consumer behavior in ways that are not fully accounted for in the research model.

Acknowledging the limitations of the current study, future research should, first of all, account for the ongoing armed conflict when designing measurement scales for identifying collaborative-consumption-related attitudes and behaviors—if the research is conducted during the conflict. The study should be repeated after the conflict concludes, which would allow for comparative analysis and an assessment of the armed conflict’s impact on Generation Z’s consumption behaviors. In future research, if conditions allow, it would be advisable to consider increasing the sample size in quantitative studies. Additionally, the application of in-depth interviews could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the motivations underlying Generation Z’s participation in collaborative consumption.