Integrating Business Ethics into Occupational Health and Safety: An Evaluation Framework for Sustainable Risk Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Principles and Theoretical Foundations of Business Ethics

2.2. Occupational Health and Safety Standards

2.3. Intersection of Business Ethics and Occupational Health and Safety (OHS)

2.4. Risk Management in Occupational Safety and Health

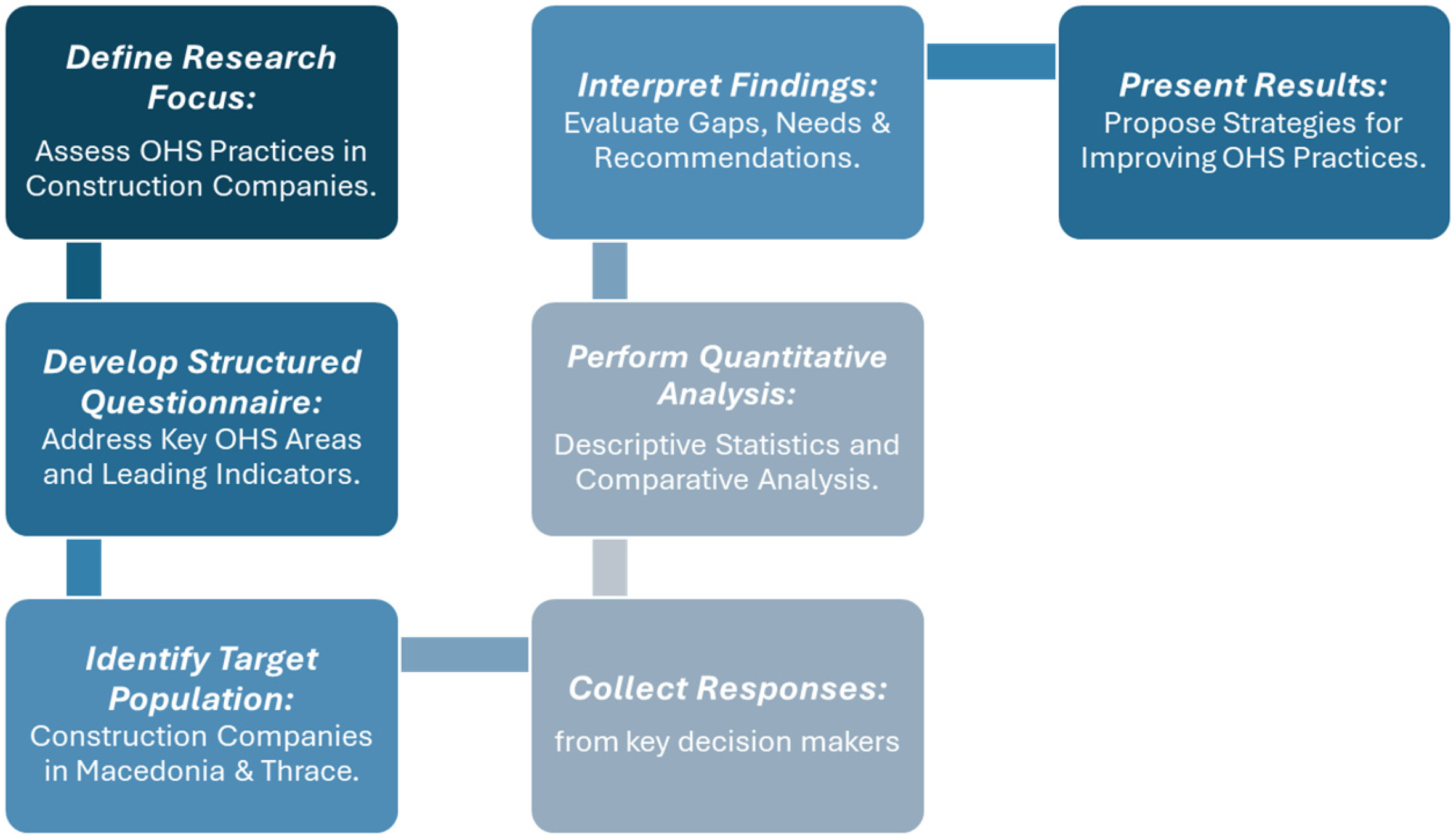

3. Methodological Framework

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crane, A.; Matten, D.; Glozer, S.; Spence, L.J. Business Ethics: Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalization, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriou, D.; Sartzetaki, M.; Karagkouni, A. Managing Airport Corporate Performance: Leveraging Business Intelligence and Sustainable Transition; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; ISBN 978-0-443-29109-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 45001:2018; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/63787.html (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Occupational Safety and Health Standards; U.S. Department of Labor: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.osha.gov (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Aven, T.; Vinnem, J.E. Risk Management: With Applications from the Offshore Petroleum Industry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sartzetaki, M.; Dimitriou, D.; Karagkouni, A. Assortment of the Regional Business Ecosystem Effects Driven by New Motorway Projects. Transp. Res. Procedia 2025, 82, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Rowlinson, S. Occupational Health and Safety in Construction Project Management; Spon Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- De George, R.T. Business Ethics, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, S. The relationship between safety climate and safety performance: A meta-analytic review. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M.D. Towards a model of safety culture. Saf. Sci. 2000, 36, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A. Disastrous Decisions: The Human and Organisational Causes of the Gulf of Mexico Blowout; CCH Australia Limited: Macquarie Park, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zwetsloot, G.I.J.M.; Kines, P.A.; Ruotsala, R.; Drupsteen, L.; Merivirta, M.-L.; Bezemer, R.A. The importance of commitment, communication, culture and learning for the implementation of the Zero Accident Vision in 27 companies in Europe. Saf. Sci. 2017, 96, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohnen, P.; Hasle, P.S. Making work environment auditable—A ‘critical case’ study of certified occupational health and safety management systems in Denmark. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A. A study of the lagged relationships among safety climate, safety motivation, safety behavior, and accidents at the individual and group levels. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowie, N.E. A Kantian Theory of Meaningful Work. J. Bus. Ethics 1998, 17, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunningham, N. Occupational health and safety, worker participation, and the mining industry in a changing world of work. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2008, 29, 336–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Zyglidopoulos, S. Stakeholder Theory: Concepts and Strategies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A. Perceptions of safety at work: A framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, D. Corporate Ethics: An arbitration of philosophical concepts and market practices. CONATUS Int. J. Philos. 2022, 7, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971; ISBN 0-674-00078-1. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, R.E. A Companion to Business Ethics; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Glendon, A.I.; Clarke, S. Human Safety and Risk Management: A Psychological Perspective, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A. Thinking about process safety indicators. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). C155—Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155). 2006. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/c155-occupational-safety-and-health-convention-1981-no-155 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Framework Directive 89/391/EEC on the Introduction of Measures to Encourage Improvements in the Safety and Health of Workers. 2014. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). ICMM 10 Principles. 2020. Available online: https://www.icmm.com (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Dimitriou, D.; Sartzetaki, M.; Karagkouni, A. Airport Landside Area Planning: An Activity-Based Methodology for Seasonal Airports. Transp. Res. Procedia 2025, 82, 1167–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Coze, J. Outlines of a sensitising model for industrial safety assessment. Saf. Sci. 2013, 51, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartzetaki, M.; Karagkouni, A.; Dimitriou, D. A Conceptual Framework for Developing Intelligent Services (a Platform) for Transport Enterprises: The Designation of Key Drivers for Action. Electronics 2023, 12, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beus, J.M.; McCord, M.A.; Zohar, D. Workplace safety: A review and research synthesis. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 6, 352–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, D. OHS Stewardship—Integration of OHS in Corporate Governance. Procedia Eng. 2012, 45, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, D.; Papakostas, K. Review of Management Comprehensiveness on Occupational Health and Safety for PPP Transportation Projects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iavicoli, S.; Valenti, A.; Gagliardi, D.; Rantanen, J. Ethics and Occupational Health in the Contemporary World of Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, D.; Zantanidis, S. Key Aspects of Occupational Health and Safety towards Efficiency and Performance in Air Traffic Management. In Air Traffic Management and Control; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.L.; Clarke, S. Managing the Risk of Workplace Stress: Health and Safety Hazards; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zohar, D. Modifying supervisory practices to improve subunit safety: A leadership-based intervention model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawata, K. Evaluation of physical and mental health conditions related to employees’ absenteeism. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1326334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabarison, K.M.; Lang, J.E.; Bish, C.L.; Bird, M.; Massoudi, M.S. A Simple Method to Estimate the Impact of a Workplace Wellness Program on Absenteeism Cost. Am. J. Health Promot. 2017, 31, 454–455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johns, G. Absenteeism and Presenteeism: Not at Work or Not Working Well. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Behavior; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kivimäki, M.; Head, J.; Ferrie, J.E.; Shipley, M.J.; Vahtera, J.; Marmot, M.G. Working while ill as a risk factor for serious coronary events: The Whitehall II study. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.F.; Bakker, A.B. Psychological safety climate as a precursor to conducive work environments, psychological health problems, and employee engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D. Thirty years of safety climate research: Reflections and future directions. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 1517–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Van Rhenen, W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Christensen, M. Positive Participatory Organizational Interventions: A Multilevel Approach for Creating Healthy Workplaces. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 696245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Society for Human Capital Management (GSHCM). Wellness Programs Are Key to Reducing Absenteeism in the Workplace. Published on 16 Sep. 2024. LinkedIn. 2024. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/wellness-programs-key-reducing-absenteeism-workplace-gshcm-clu9f (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Muñiz, B.; Montes-Peón, J.M.; Vázquez-Ordás, C.J. Relation between occupational safety management and firm performance. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 980–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S. An integrative model of safety climate: Linking psychological climate and work attitudes to individual safety outcomes using meta-analysis. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 553–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, A.; Boudreau-Trudel, B.; Souissi, A.S. Occupational health and safety in the industry 4.0 era: A cause for major concern? Saf. Sci. 2018, 109, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanko, M.; Dawson, P. Occupational Health and Safety Management in Organizations: A Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, A.R.; Guldenmund, F.W.; van Loenhout, P.L.C.H.; Oh, J.I.H. Evaluating safety management and culture interventions to improve safety: Effective intervention strategies. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). Management of Occupational Safety and Health: An analysis of the Findings of the European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks (ESENER). 2018. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/sites/default/files/OSH_Management_European_workplaces_ESENER_2.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. Human error: Models and management. BMJ 2000, 320, 768–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiman, T.; Pietikäinen, E. Leading indicators of system safety–Monitoring and driving the organizational safety potential. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 1993–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Section | Question | Response Format |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Demographic and Professional Information | Gender | Female, Male, Other |

| Age | 20–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, >60 | |

| Education background | Technical University, University, MSc/MBA, PhD | |

| Number of employees in the company | 1–20 (Micro), 21–50 (Small), 51–100 (Medium), 101–250 (Medium), 251–500 (Large), >500 (Large) | |

| Role in the company | Owner/Board Member, CEO/Managing Director, General Manager, Director of OHS, Production Manager, Department Supervisor, Health and Safety Officer, Other | |

| Number of years in the company | 0–5, 6–10, 11–20, >20 | |

| Number of employees under responsibility | 1–10, 11–20, 21–50, 51–100, >100 | |

| 2. OHS Compliance | Does the company employ a safety technician? | Yes/No |

| Does the company implement an occupational health and safety management system (OHSAS 18001/ISO 45001)? | Yes/No | |

| 3. Workplace Safety Performance (Past Incidents) | Have employees developed health problems due to work (musculoskeletal, respiratory, hearing impairments, etc.) in the last 5 years? | Yes/No/Not Registered |

| If yes, how many employees have reported work-related health problems in the last 5 years? | 1/2–5/>5 | |

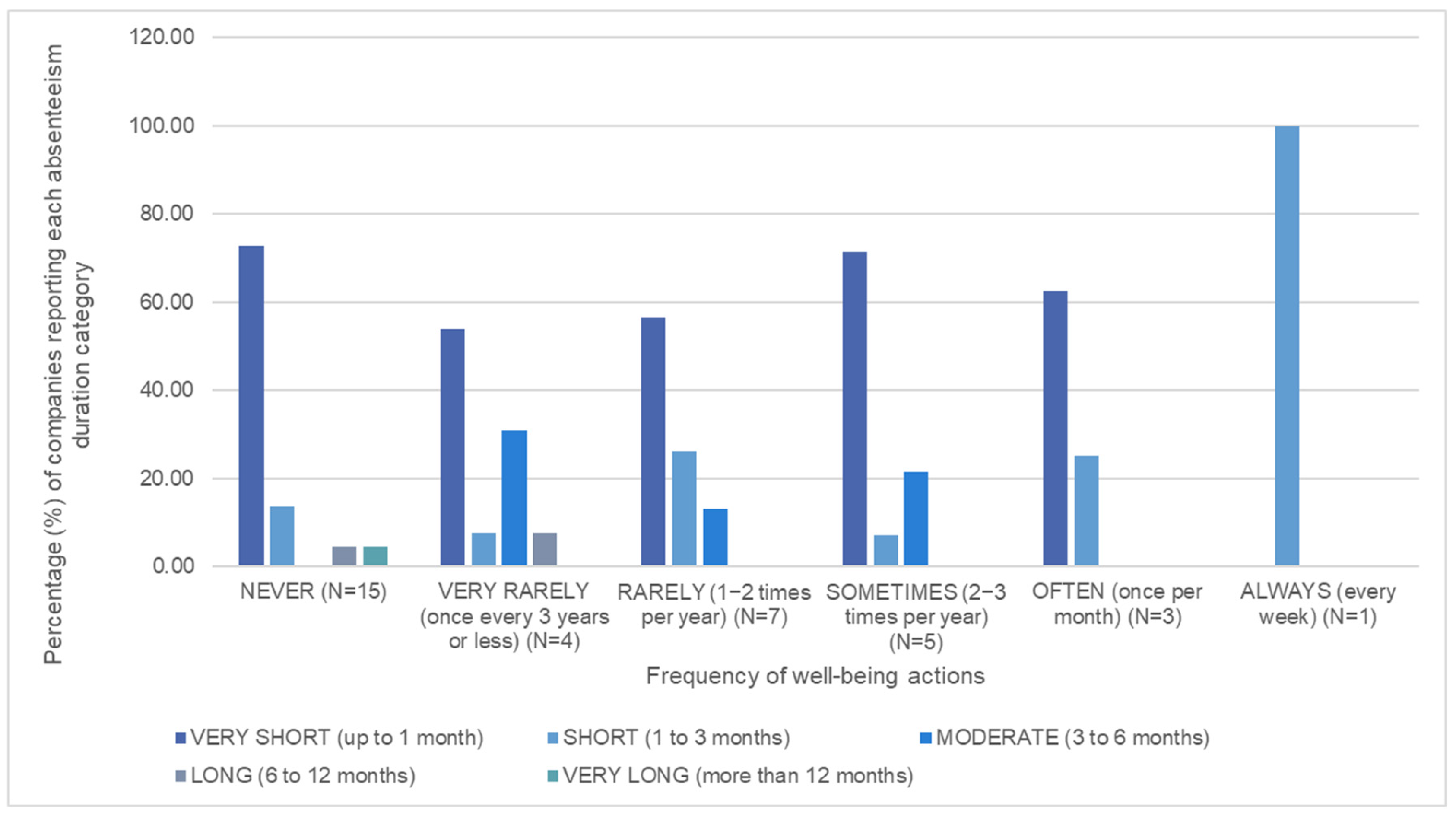

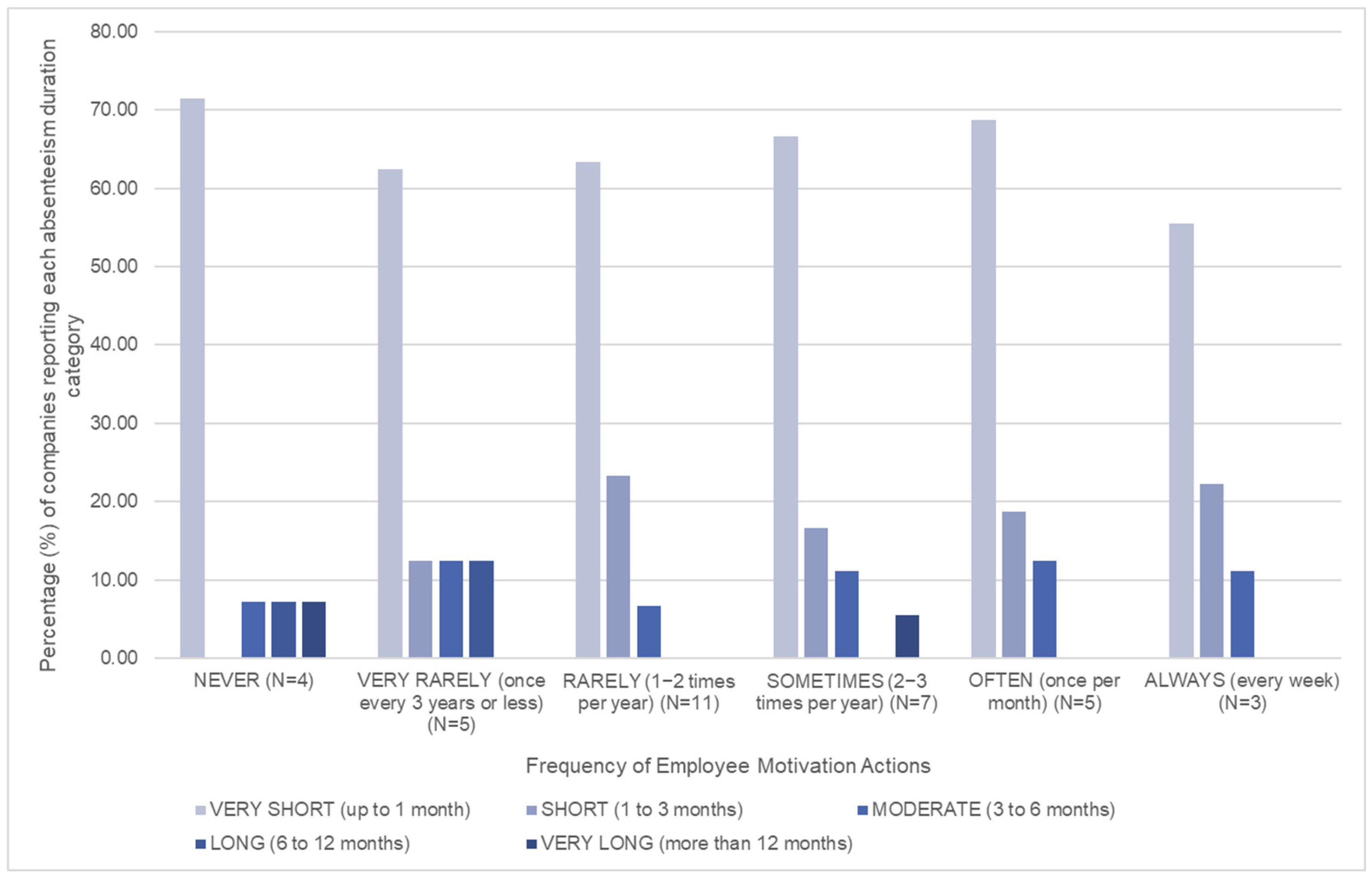

| What has been the total absenteeism due to general health issues (physical and mental) in the past 5 years/ | Very Short (up to 1 month), Short (1–3 months), Moderate (3–6 months), Long (6–12 months), Very Long (more than 12 months) | |

| 4. Proactive Occupational Health & Safety Measures | Is training provided to staff on occupational health and safety (OHS) topics? | Very Rarely (once or less every 3 years), Rarely (1–2 times/year), Occasionally (2–3 times/year), Often (once a month), Always (every week) |

| Is training provided to newly hired staff on occupational health and safety and accident prevention? | Very Rarely (once or less every 3 years), Rarely (1–2 times/year), Occasionally (2–3 times/year), Often (once a month), Always (every week) | |

| To what extent are the safety measures recommended by the safety technician implemented? | 30%/50%/80%/100% (all recommendations are implemented) | |

| Are employees actively motivated to support OHS initiatives (incentives, campaigns, safety talks, etc.)? | Never, Very Rarely (once or less every 3 years), Rarely (1–2 times per year), Sometimes (2–3 times per year), Often (once per month), Always (every week) | |

| Are there initiatives implemented to promote employees’ overall wellbeing? | Never, Very Rarely (once or less every 3 years), Rarely (1–2 times per year), Sometimes (2–3 times per year), Often (once per month), Always (every week) |

| Variables | Descriptive Statistics n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 20–30 | 2 (5.71) |

| 31–40 | 9 (25.71 |

| 41–50 | 12 (34.29) |

| 51–60 | 11 (31.43) |

| >60 | 1 (2.86) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 22 (62.85) |

| Male | 13 (37.15) |

| Education Background | |

| Technical University | 7 (20.00) |

| University | 11 (31.43) |

| MSc/MBA | 15 (42.86) |

| PhD | 2 (5.71) |

| Role in the company | |

| Owner/Board Member | 8 (22.86) |

| CEO/Managing Director | 3 (8.57) |

| General Manager | 4 (11.43) |

| Director of Occupational Health and Safety Department | 3 (8.57) |

| Production Manager | 4 (11.43) |

| Department Supervisor | 4 (11.43) |

| Health and Safety Officer | 5 (14.28) |

| Other | 4 (11.43) |

| Number of years in the company | |

| 0–5 | 11 (31.43) |

| 6–10 | 8 (22.86) |

| 11–20 | 9 (25.71) |

| >20 | 7 (20.00) |

| Number of employees under responsibility | |

| 1–10 | 14 (40.00) |

| 11–20 | 3 (8.57) |

| 21–50 | 7 (20.00) |

| 51–100 | 6 (17.14) |

| >100 | 5 (14.29) |

| Number of employees in the company | |

| 1–20 | 6 (17.14) |

| 21–50 | 5 (14.29) |

| 51–250 | 19 (54.29) |

| >250 | 5 (14.28) |

| Very Rarely (Once or Less Every 3 Years) | Rarely (1–2 Times/Year) | Occasionally (2–3 Times/Year) | Often (Once a Month) | Always (Every Week) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workforce Training on Occupational Health and Safety | |||||

| 1–20 | 5.56 | 38.87 | 55.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 21–50 | 14.29 | 21.43 | 35.71 | 21.43 | 7.14 |

| 51–250 | 10.71 | 25.00 | 44.64 | 17.86 | 1.79 |

| >250 | 0.00 | 46.66 | 40.00 | 6.67 | 6.67 |

| Newly hired personnel receive training on Occupational Health and Safety and accident prevention. | |||||

| 1–20 | 0.00 | 27.78 | 33.33 | 16.67 | 22.22 |

| 21–50 | 28.57 | 0.00 | 28.57 | 21.43 | 21.43 |

| 51–250 | 10.71 | 14.29 | 21.43 | 19.64 | 33.93 |

| >250 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 26.66 | 53.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mixafenti, S.; Karagkouni, A.; Dimitriou, D. Integrating Business Ethics into Occupational Health and Safety: An Evaluation Framework for Sustainable Risk Management. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4370. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104370

Mixafenti S, Karagkouni A, Dimitriou D. Integrating Business Ethics into Occupational Health and Safety: An Evaluation Framework for Sustainable Risk Management. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4370. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104370

Chicago/Turabian StyleMixafenti, Stavroula (Vivi), Aristi Karagkouni, and Dimitrios Dimitriou. 2025. "Integrating Business Ethics into Occupational Health and Safety: An Evaluation Framework for Sustainable Risk Management" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4370. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104370

APA StyleMixafenti, S., Karagkouni, A., & Dimitriou, D. (2025). Integrating Business Ethics into Occupational Health and Safety: An Evaluation Framework for Sustainable Risk Management. Sustainability, 17(10), 4370. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104370