Embedding Social Sustainability in Education: A Thematic Review of Practices and Trends Across Educational Pathways from a Global Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Scope and Focus

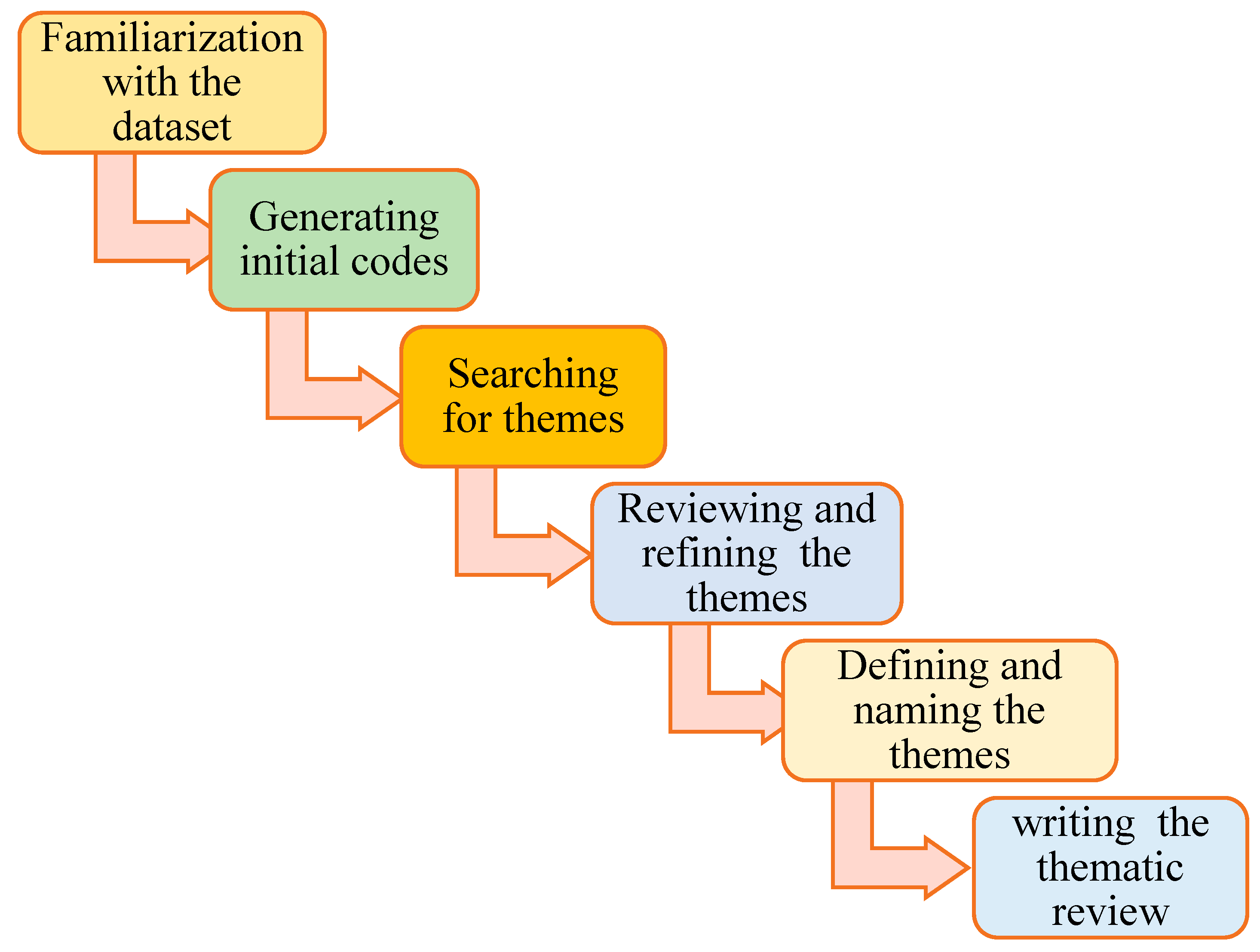

2.3. Thematic Analysis

2.4. Conceptual and Analytical Framework

3. Results

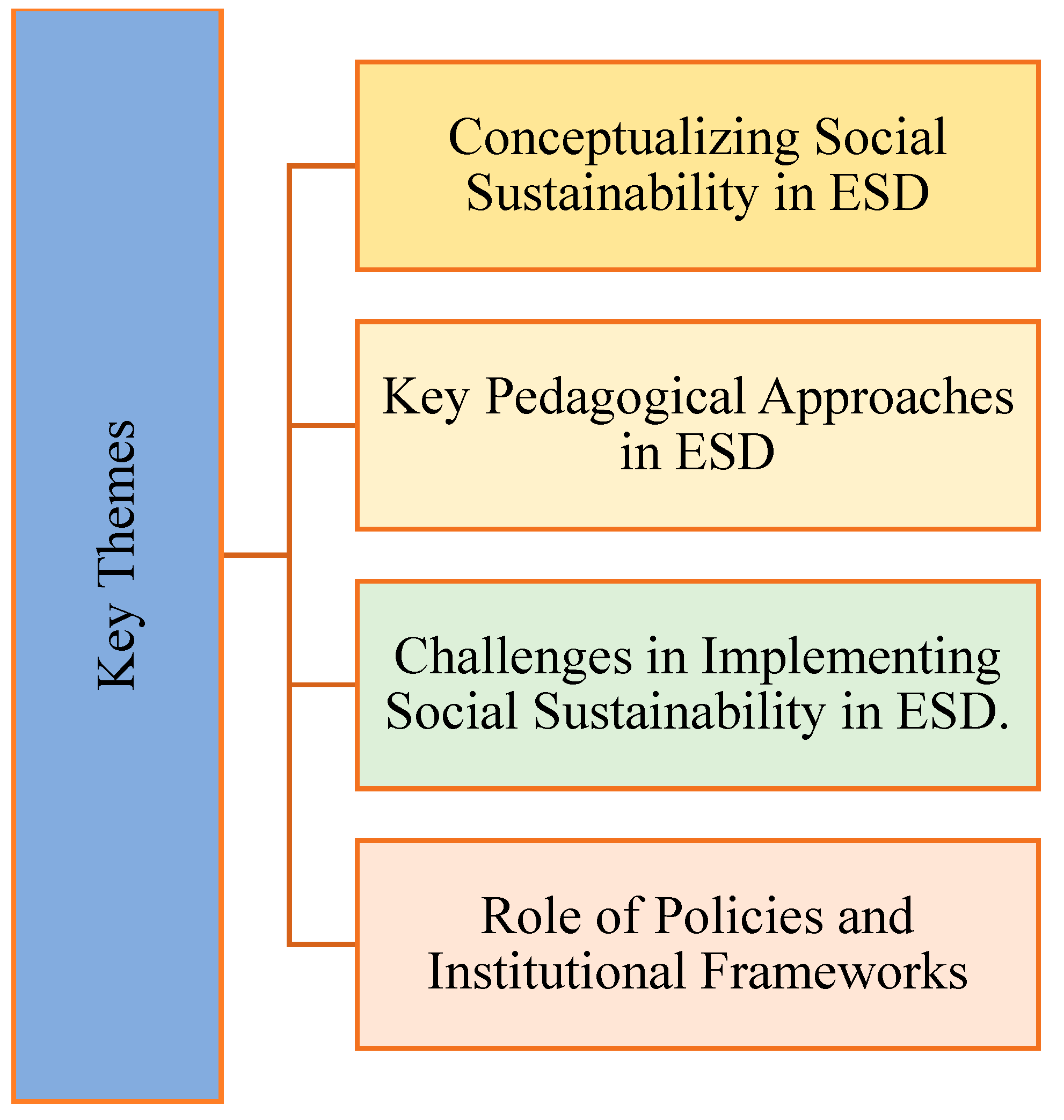

3.1. Qualitative Thematic Analysis

3.1.1. Conceptualizing Social Sustainability in ESD

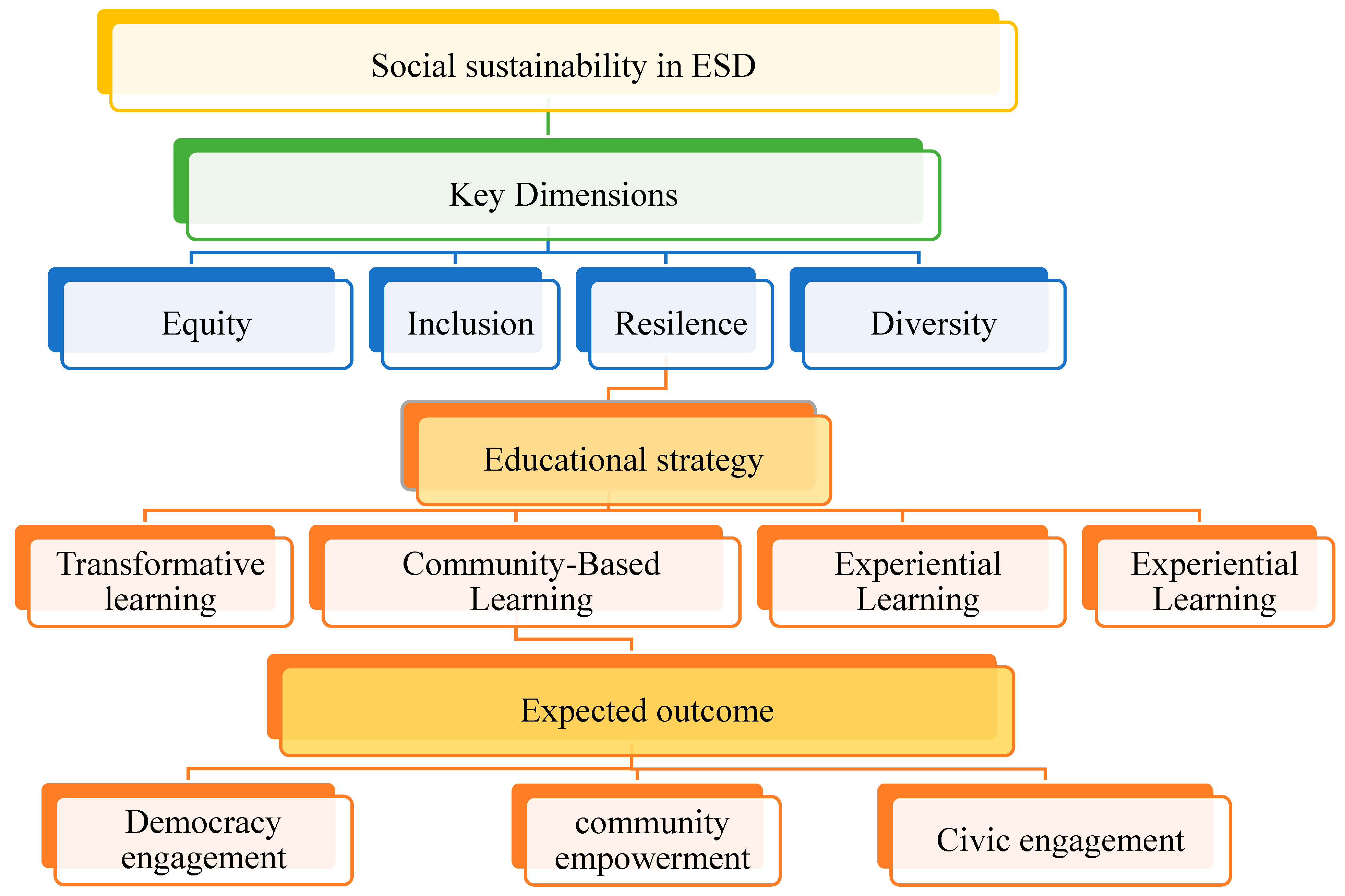

3.1.2. Key Elements of Social Sustainability in ESD

3.1.3. Key Pedagogical Approaches in ESD

3.1.4. Challenges in Implementing Social Sustainability (SS) in ESD

3.1.5. Role of Policies and Institutional Frameworks in Integrating Social Sustainabilityin Education

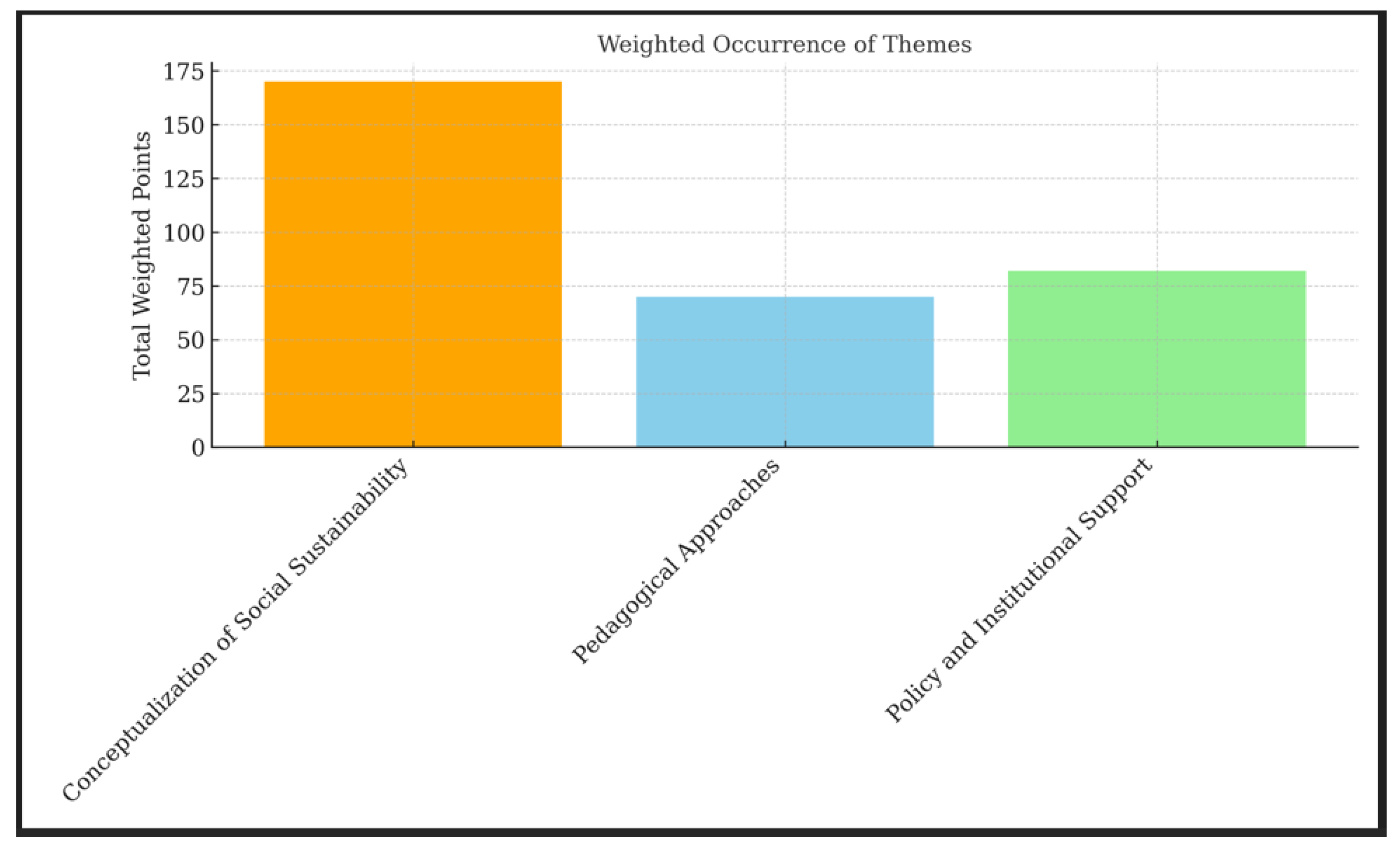

3.2. Quantitative Thematic Analysis

3.2.1. Weighted Occurrence of Themes

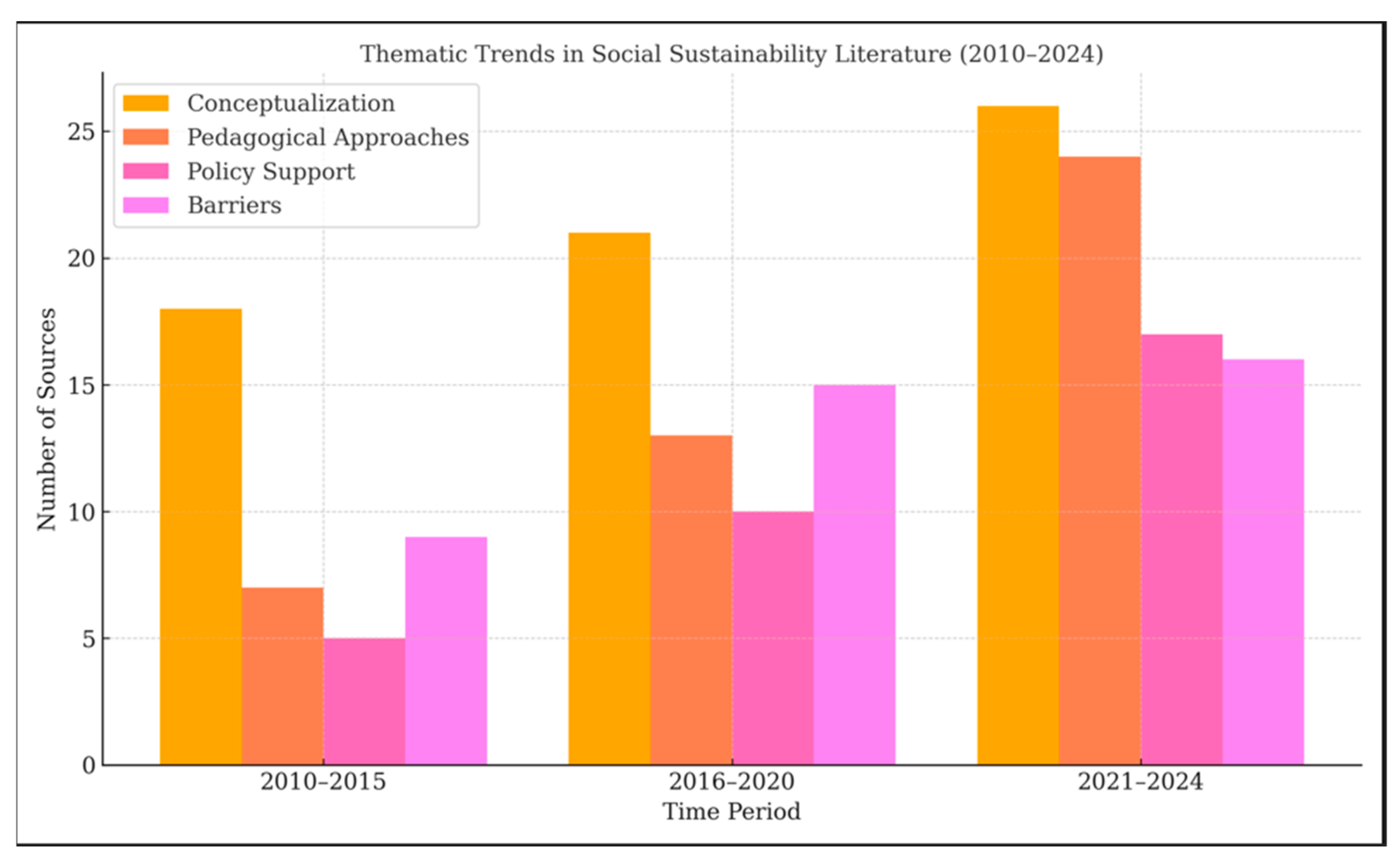

3.2.2. Trends of Themes over Time (2010–2024)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. N. Y. United Nations Dep. Econ. Soc. Aff. 2015, 1, 41. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. A Guide for Ensuring Inclusion and Equity in Education; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Transformative Learning and Sustainability: Sketching the Conceptual Ground. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 2011, 5, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R.; Young, W. Assessing Sustainability in University Curricula: Exploring the Influence of Student Numbers and Course Credits. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 49, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemer, A.; Ndiaye, A.; Khushik, F.; Pellaud, F. Education for Sustainable Development: A Conceptual and Methodological Approach. Soc. Sci. Learn. Educ. J. 2019, 4, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cicerchia, A. Culture Indicators for Sustainable Development. In Cultural Initiatives for Sustainable Development: Management, Participation and Entrepreneurship in the Cultural and Creative Sector; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 345–372. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Waldt, G. Towards a Conceptual Framework for the Social Dimensions of Sustainable Development. Afr. J. Gov. Dev. 2024, 13, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafese, M.B.; Kopp, E. Education for Sustainable Development: Analyzing Research Trends in Higher Education for Sustainable Development Goals through Bibliometric Analysis. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Skouloudis, A.; Brandli, L.L.; Salvia, A.L.; Avila, L.V.; Rayman-Bacchus, L. Sustainability and Procurement Practices in Higher Education Institutions: Barriers and Drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1267–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. Higher Education for Sustainability: A Global Overview of Commitment and Progress. High. Educ. World 2011, 4, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, L.-A.; Ehrström, P. Social Sustainability and Transformation in Higher Educational Settings: A Utopia or Possibility? Sustainability 2020, 12, 4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research in Systematic Reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Flemming, K.; McInnes, E.; Oliver, S.; Craig, J. Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research: ENTREQ. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 101–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemler, S. An Overview of Content Analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2000, 7, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boell, S.K.; Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. On Being ‘Systematic’in Literature. In Formulating Research Methods for Information Systems; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, E. Greening TVET Colleges Initiative in South Africa: A Guide for Practitioners; Deutsche Gesellschaft für International Zusammenarbeit (GIZ): Pretoria, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Finnish National Agency for Education. National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014; Next Print: Helsinki, Finland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyan Ministry of Education. Education for Sustainable Development Policyfor the Education Sector; Kenyan Ministry of Education: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W. Public Understanding of Sustainable Development: Some Implications for Education. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2015, 10, 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan Incorporation of ESD into National Curriculum Guidelines and Promotion Through the UNESCO Associated Schools Network; Ministry of Education: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th ed.; Anniversary, Ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.A. The Kolb Learning Style Inventory; Hay Resources Direct: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martusewicz, R.A.; Edmundson, J.; Lupinacci, J. Ecojustice Education: Toward Diverse, Democratic, and Sustainable Communities; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; ISBN 1-315-77949-8. [Google Scholar]

- Westheimer, J. Can Education Transform Our World? Global Citizenship Education and the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In Grading Goal Four; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 280–296. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.; Dhingra, S.; Andrews, K.; Gospodinov, J.; Liu, C.; Alix Hayden, K. Grand Challenges as Educational Innovations in Higher Education: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Educ. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 6653575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, T.; Gericke, N. Diversity in Views as a Resource for Learning? Student Perspectives on the Interconnectedness of Sustainable Development Dimensions. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 354–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, F.; Gericke, N. Local and Global Aspects: Teaching Social Sustainability in Swedish Preschools. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education: All Means All; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020; ISBN 978-92-3-100388-2. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap (ESD for 2030); UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Guide on Human Rights Education Curriculum Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott, E.; Lomeli-Rodriguez, M.; Rahman, A.; Direzkia, Y.; Bernardino, A.; Burgess, R.; Joffe, H. Fostering Resilient Recovery: An Intervention for Disaster-Affected Teachers in Indonesia. SSM-Ment. Health 2024, 6, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leicht, A.; Heiss, J.; Byun, W.J. Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; Volume 5, ISBN 92-3-100244-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R.; Barreiro-Gen, M. Analysing the Factors Affecting the Incorporation of Sustainable Development into European Higher Education Institutions’ Curricula. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcagni, A.; Fattore, M.; Maggino, F.; Vittadini, G. Some Critical Reflections on the Measurement of Social Sustainability and Well-Being in Complex Societies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riolo, I. A Journey Towards Value-Laden Education: Understanding Teachers’ Perceptions of the Social Domain Within the Maltese Physical Education Context. Ph.D. Thesis, Loughborough University, Loughborough, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mireé, I.; Toryalay, A. Operationalization of Social Sustainability in the Construction Industry from a Client Perspective, How the Concept of Social Sustainability in the Construction Industry Is Defined and Communicated by Skanska’s Proposed Clients? Master’s Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Piwowarczyk, J. Mapping Barriers to Sustainable Development with Interactive Management: Coastal Areas of the Pomeranian Province (Poland) and Marine Areas off the Coast. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gdansk, Gdansk, Polish, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bickmore, K. 10 Social Justice and the Social Studies. In Handbook of Research in Social Studies Education; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2008; p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- Lingard, B.; Mills, M. Pedagogies Making a Difference: Issues of Social Justice and Inclusion. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2007, 11, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. Key Issues in Education and Social Justice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, L.A. Theoretical Foundations for Social Justice Education. In Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai, A.K.; Lypson, M.L. Beyond Cultural Competence: Critical Consciousness, Social Justice, and Multicultural Education. Acad. Med. 2009, 84, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, A. Critical Pedagogy for a Sustainable Future: Investigating Paulo Freire’s Influence on Education for Sustainable Development; DiVA: Uppsala University, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kioupi, V.; Voulvoulis, N. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Assessing the Contribution of Higher Education Programmes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharis, G. The School Leaders Our Children Deserve: Seven Keys to Equity, Social Justice, and School Reform; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024; ISBN 0-8077-8235-1. [Google Scholar]

- Boud, D.; Keogh, R.; Walker, D. Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; ISBN 1-315-05905-3. [Google Scholar]

- Einfeld, A.; Collins, D. The Relationships between Service-Learning, Social Justice, Multicultural Competence, and Civic Engagement. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2008, 49, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, R.B.; Lasen, M.; Ferreira, J.-A.; Davis, J. Approaches to Embedding Sustainability in Teacher Education: A Synthesis of the Literature. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 405–417. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Learning Theory. In Contemporary Theories of Learning; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 114–128. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. In The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series; ERIC: Hershey, PA, USA, 2000; ISBN 0-7879-4845-4. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H.A. Rethinking Education as the Practice of Freedom: Paulo Freire and the Promise of Critical Pedagogy. Policy Futures Educ. 2010, 8, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringle, R.G.; Hatcher, J.A. A Service-Learning Curriculum for Faculty; ScholarWorks: Morrow, GA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Grindheim, L.T.; Bakken, Y.; Hauge, K.H.; Heggen, M.P. Early Childhood Education for Sustainability through Contradicting and Overlapping Dimensions. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2019, 2, 374–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, A.; Österlind, E.; Viirret, T.L. Drama in Education for Sustainability: Becoming Connected through Embodiment. Int. J. Educ. Arts 2020, 21, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Palmberg, I.; Hofman-Bergholm, M.; Jeronen, E.; Yli-Panula, E. Systems Thinking for Understanding Sustainability? Nordic Student Teachers’ Views on the Relationship between Species Identification, Biodiversity and Sustainable Development. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molderez, I.; Ceulemans, K. The Power of Art to Foster Systems Thinking, One of the Key Competencies of Education for Sustainable Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Barreiro-Gen, M.; Lozano, F.J.; Sammalisto, K. Teaching Sustainability in European Higher Education Institutions: Assessing the Connections between Competences and Pedagogical Approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Morales, S.; Ferriz-Valero, A. What about Physical Education and Sustainable Development Goals? A Scoping Review. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2023, 30, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. Sustainability Indicators: Measuring the Immeasurable? Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012; ISBN 1-84977-272-X. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jickling, B.; Wals, A.E.J. Globalization and Environmental Education: Looking beyond Sustainable Development. J. Curric. Stud. 2008, 40, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, C.; McKeown, R. Education for Sustainable Development: An International Perspective. Educ. Sustain. 2002, 13, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Huckle, J.; Wals, A.E.J. The UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development: Business as Usual in the End. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J.; Rodela, R. Social Learning towards Sustainability: Problematic, Perspectives and Promise. NJAS-Wagening. J. LIFE Sci. 2014, 69, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giangrande, N.; White, R.M.; East, M.; Jackson, R.; Clarke, T.; Coste, M.S.; Penha-Lopes, G. A Competency Framework to Assess and Activate Education for Sustainable Development: Addressing the UN Sustainable Development Goals 4.7 Challenge. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulla, K.; Filho, W.L.; Lardjane, S.; Sommer, J.H.; Borgemeister, C. Sustainable Development Education in the Context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGI (Sustainable Governance Indicators). Finland: Social Policies; SGI (Sustainable Governance Indicators): Atrium Amot Building, Israel, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, P.; Christie, B. Learning for Sustainability. In Scottish Education; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2018; pp. 554–564. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). The UNECE Strategy for Education for Sustainable Development; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Teachers Have Their Say: Motivation, Skills and Opportunities to Teach Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS). Education for Sustainable Development: RCEs and ProSPER.Net; UNU-IAS: Shibuya, Japan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Separate Tracks or Real Synergy? Achieving a Closer Relationship between Education and SD, Post-2015. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 8, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikly, L. Education for Sustainable Development in Africa: A Critique of Regional Agendas. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2019, 20, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.A.; Sobel, D. Place-and Community-Based Education in Schools; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; ISBN 0-203-85853-0. [Google Scholar]

- Krstić, M.; Filipe, J.A.; Chavaglia, J. Higher Education as a Determinant of the Competitiveness and Sustainable Development of an Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tafese, M.B.; Kopp, E. Embedding Social Sustainability in Education: A Thematic Review of Practices and Trends Across Educational Pathways from a Global Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104342

Tafese MB, Kopp E. Embedding Social Sustainability in Education: A Thematic Review of Practices and Trends Across Educational Pathways from a Global Perspective. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104342

Chicago/Turabian StyleTafese, Mestawot Beyene, and Erika Kopp. 2025. "Embedding Social Sustainability in Education: A Thematic Review of Practices and Trends Across Educational Pathways from a Global Perspective" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104342

APA StyleTafese, M. B., & Kopp, E. (2025). Embedding Social Sustainability in Education: A Thematic Review of Practices and Trends Across Educational Pathways from a Global Perspective. Sustainability, 17(10), 4342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104342