Information Disclosure in the Context of Combating Climate Change: Evidence from the Chinese Natural Gas Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

- (1)

- Completeness, relevance, comprehensiveness, validity, and prospectiveness.

- (2)

- Balance.

- (3)

- Reliability, verifiability, and authenticity.

- (4)

- Comparability and consistency.

- (5)

- Understandability and substantiveness.

2.2. CRITIC Method

2.3. Keyword Extraction Method

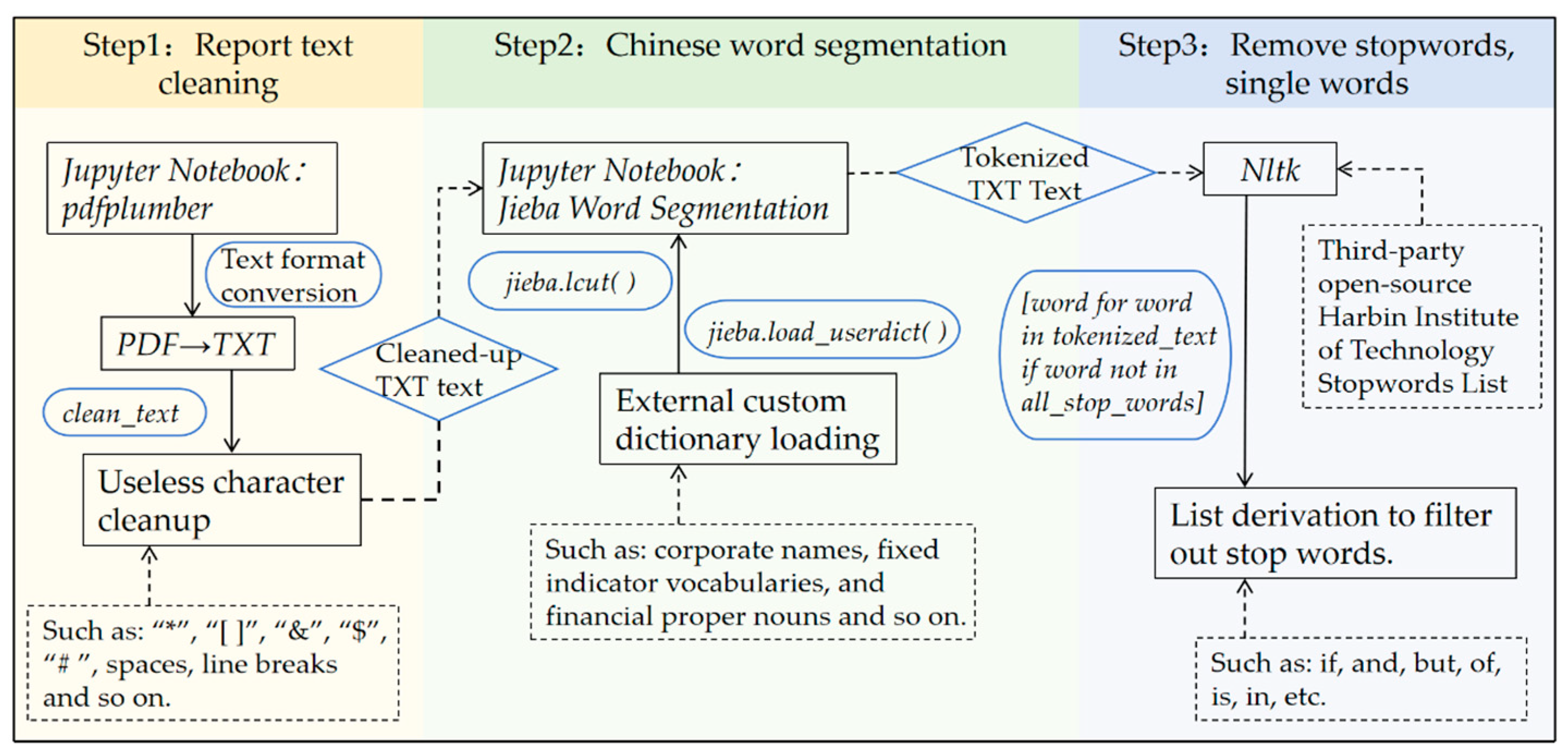

2.3.1. Text Preprocessing

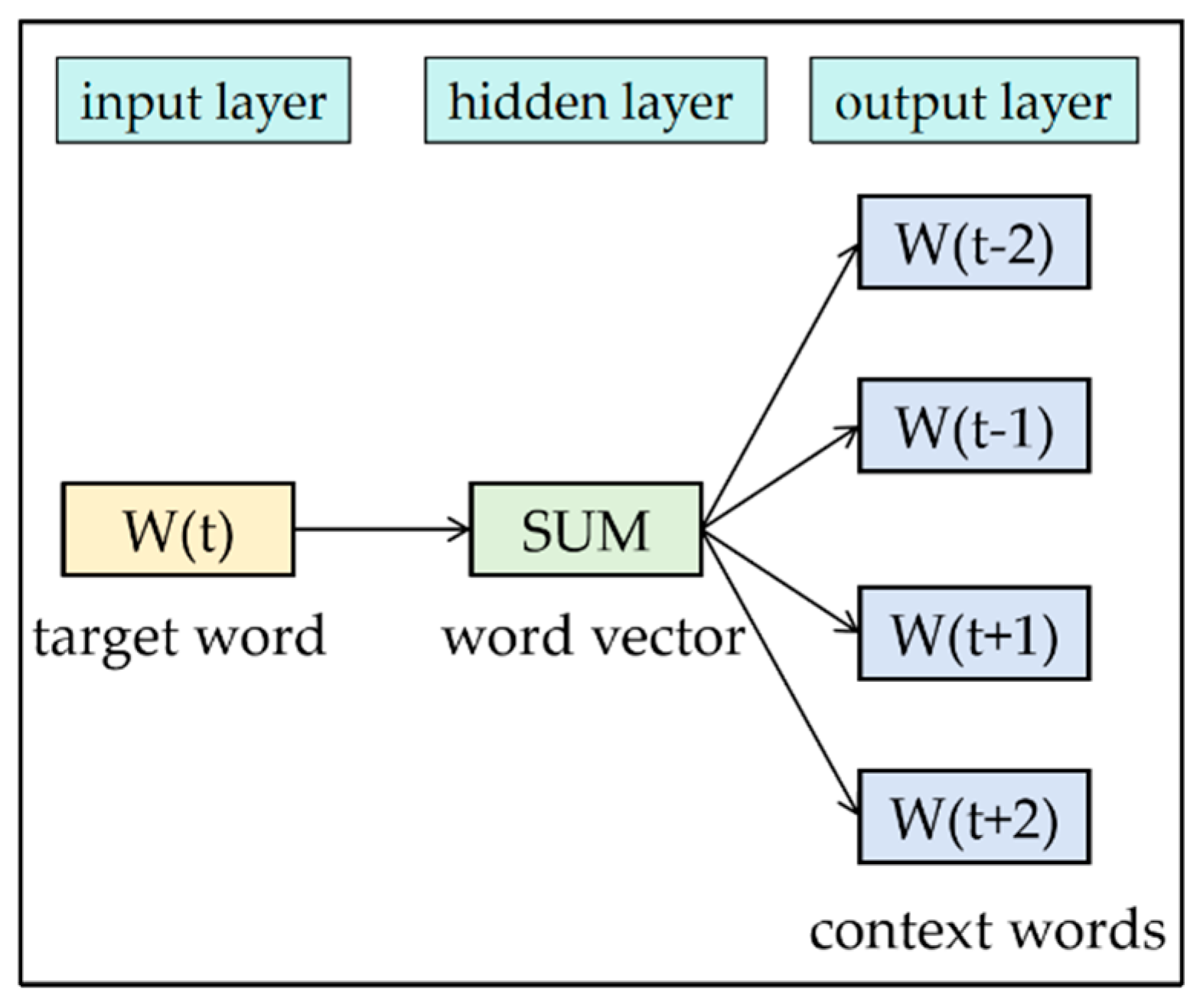

2.3.2. Designated Keyword Thesaurus Construction

2.3.3. Word Frequency Statistics

3. Constructing a Climate Change Disclosure Quality Evaluation System

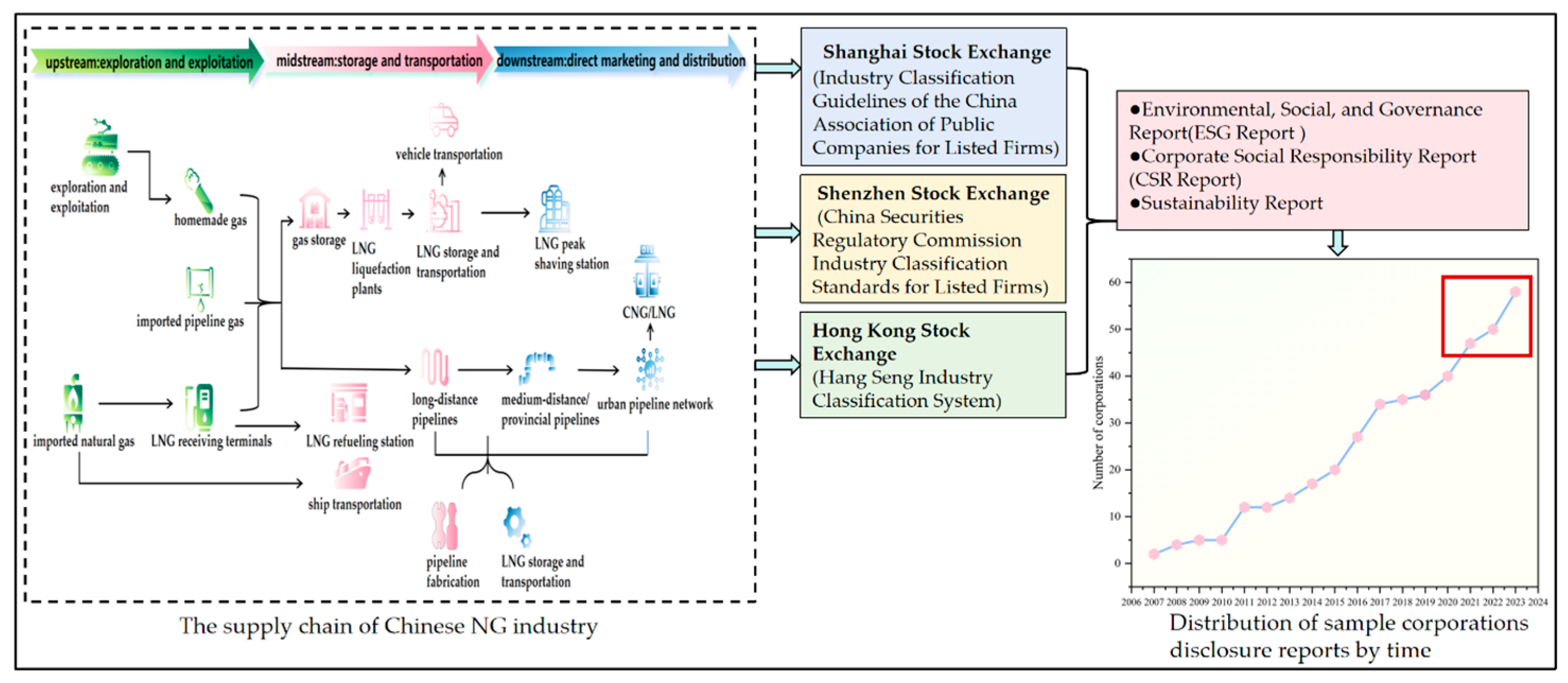

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Climate Change Disclosure Quality Index System

- Establishment of an evaluation index system

- Governance: How organizations manage climate-related risks and opportunities.

- Strategy: The implications of climate-related risks and opportunities for an organization’s business, strategic, and financial planning.

- Risk management: The process by which the organization identifies, assesses, and manages climate-related risks.

- Metrics and targets: The metrics and targets the organization uses to manage climate-related risks and opportunities.

- Measurement of the response of the reference texts

4. Results and Discussion

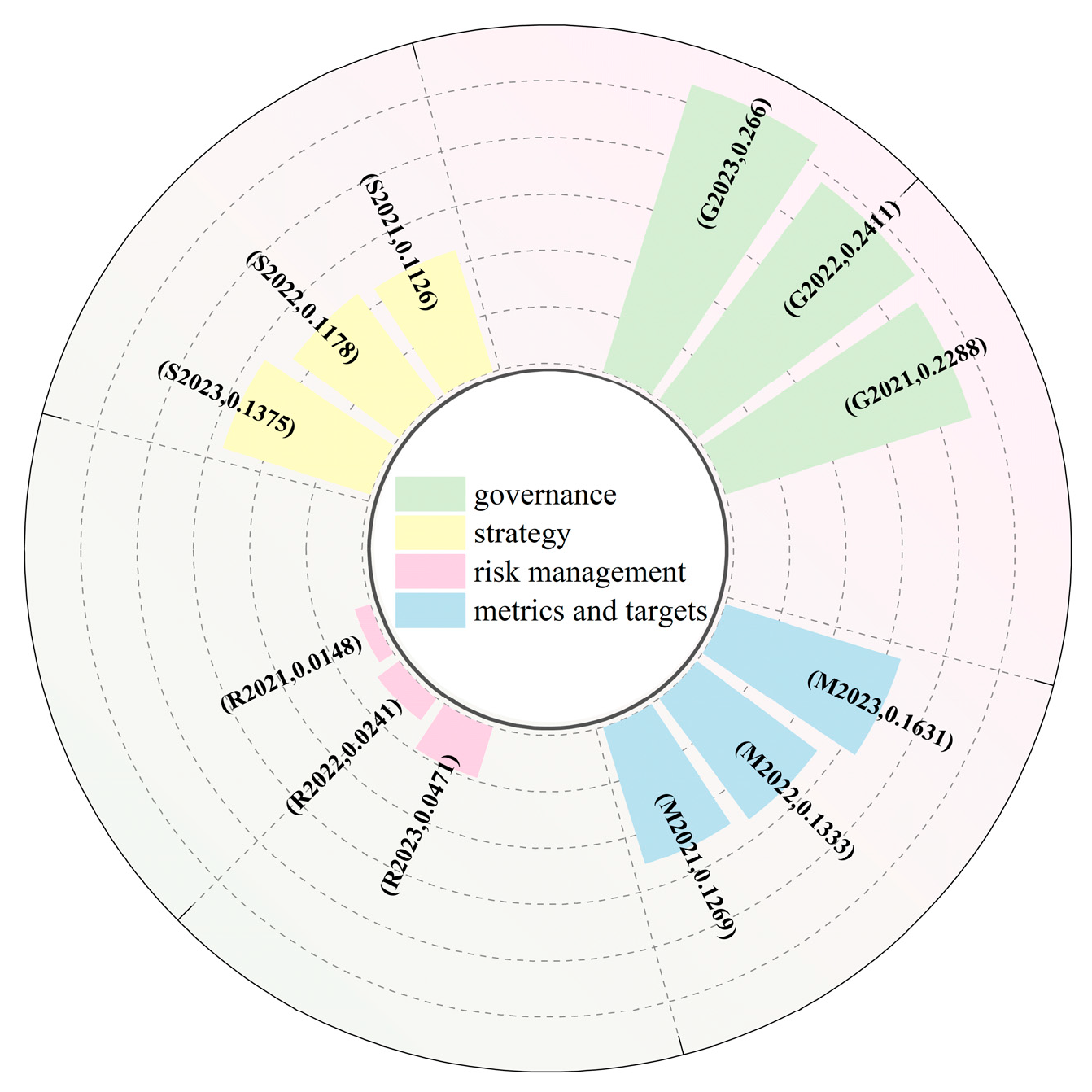

4.1. CCD Analysis

4.1.1. Status of CCD in the NG Industry in China

4.1.2. CCDQI Differences in the Quality Level of Each Corporation

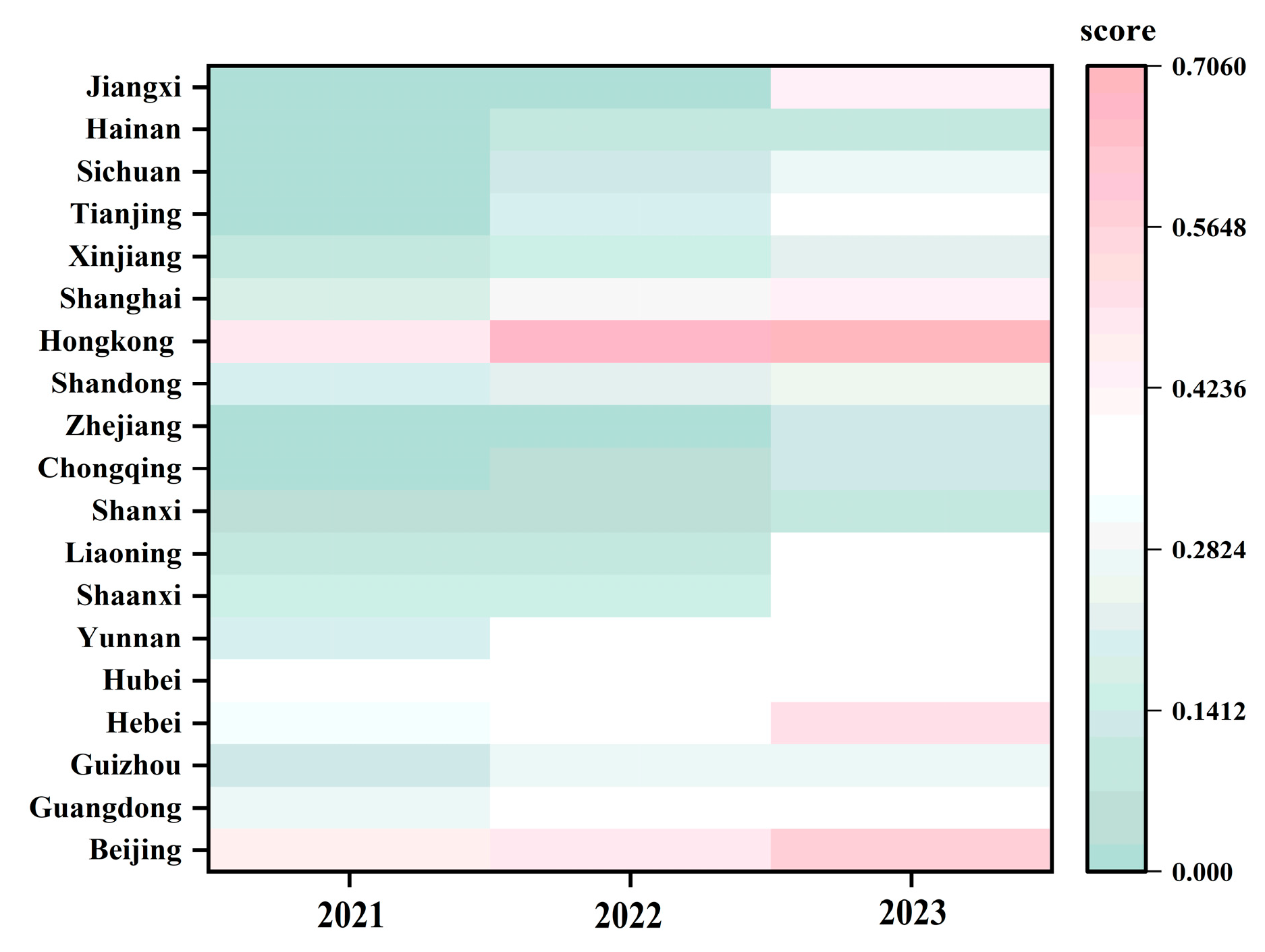

Geographic Area Differences

Industry Chain Differences

Completeness Dimension Differences

4.2. Climate Change Disclosure—Environmental Topics

5. Suggested Improvements

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report; M/OL; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithambo, L.; Tingbani, I.; Agyapong, G.A.; Gyapong, E.; Damoah, I.S. Corporate voluntary greenhouse gas reporting: Stakeholder pressure and the mediating role of the chief executive officer. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1666–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEF. The_Global_Risks_Report_2024; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2024/ (accessed on 10 February 2025)M/OL.

- Rözer, V.; Mehryar, S.; Alsahli, M.M.M. Climate change risk trap: Low-carbon spatial restructuring and disaster risk in petroleum-based economies. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 024052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ararat, M.; Sayedy, B. Gender and Climate Change Disclosure: An Interdimensional Policy Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCC. UN Climate Change Conference Baku; United Nations Climate Change: Bonn, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://unfccc.int/cop29 (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Dahlmann, F.; Roehrich, J.K. Sustainable supply chain management and partner engagement to manage climate change information. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1632–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarakis, G.; Zafeiriou, E.; Sariannidis, N. The Impact of Carbon Performance on Climate Change Disclosure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1078–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelia, R.W.; Suhardjanto, D.; Probohudono, A.N.; Honggowati, S. Environmental disclosures in mining companies: Are there any stakeholder demands? IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1248, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.T.T.; Kimura, A. Disclosure characteristics of annual reports and information asymmetry: Evidence from foreign firms listed on the US stock exchange. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 54, 103776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel-Zadeh, A.; Tang, Q.L. Managing the shift from voluntary to mandatory climate disclosure: The role of carbon accounting. Br. Account. Rev. 2025, 101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, L.S.; Thorne, L.; Cecil, L.; LaGore, W. A research note on standalone corporate social responsibility reports: Signaling or greenwashing? Crit. Perspect. Account. 2013, 24, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braasch, A.; Velte, P. Climate reporting quality following the recommendations of the task force on climate-related financial disclosures: A Focus on the German capital market. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 926–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.; Luu, B.V.; Chen, C.H. Greenwashing in environmental, social and governance disclosures. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2020, 52, 101192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosooghi, S.; Caparrós, A. Information disclosure and dynamic climate agreements: Shall the IPCC reveal it all? Eur. Econ. Rev. 2022, 143, 104042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, X.L.; Zhang, M.H.; Smart, P. Climate change disclosure and the promise of response-ability and transparency: A synthesizing framework and future research agenda. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2023, 20, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iozzelli, L. Fostering transparency? Analysing information disclosure in transnational regulatory climate initiatives. Earth Syst. Gov. 2023, 18, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.D.; Nishitani, K.; Kokubu, K.; Freedman, M.; Weng, Y. Revisiting sustainability disclosure theories: Evidence from corporate climate change disclosure in the United States and Japan. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. 2022 State of Climate Services: Energy; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://wmo.int/publication-series/2022-state-of-climate-services-energy (accessed on 10 February 2025)M/OL.

- Ameli, N.; Kothari, S.; Grubb, M. Misplaced expectations from climate disclosure initiatives. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.H.; Wang, J.; Liang, Y. Development of China’s natural gas industry during the 14 Five-Year Plan in the background of carbon neutrality. Nat. Gas Ind. 2021, 41, 171.e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.X. Carbon neutralization activates natural gas demand potential in multiple fields. Energy 2020, 11, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- GOSC. Action Plan for Carbon Dioxide Peaking Before 2030. In General Office of the State Council, PRC; 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2021-10/26/content_5644984.htm (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Du, P.P.; Wang, J.C.; Wei, Y.Y.; Qin, J.Y.; Yu, L.M. The effect of public environmental participation on pollution governance in China: The mediating role of local governments’ environmental attention. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 104, 107345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cai, K.H.; Song, Q.B.; Zeng, X.L.; Yuan, W.Y.; Li, J.H. How effective are WEEE policies in China? A strategy evaluation through a PMC-index model with content analysis. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhua Net. 2023 Smart Energy Conference a Success. Beijing, China. 2023. Available online: https://english.news.cn/china/index.htm (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Liu, Z.B.; Zhang, C.Y. Quality evaluation of carbon information disclosure of public companies in China’s electric power sector based on ANP-Cloud model. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 96, 106818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dosari, M.; Marques, A.; Fairbrass, J. The effect of the EU’s directive on non-financial disclosures of the oil and gas industry. Account. Forum. 2023, 47, 166–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljanadi, Y.; Alazzani, A. Sustainability reporting indicators used by oil and gas companies in GCC countries: IPIECA guidance approach. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1069152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Hörisch, J.; Schaltegger, S. Environmental management accounting and its effects on carbon management and disclosure quality. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1608–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Zheng, S.; Adams, J.; Jaggi, B. The effect stakeholders have on voluntary carbon disclosure within Chinese business organizations. Carbon Manag. 2020, 11, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Ali, R.; Rehman, R.u. Is there a complementary or a substitutive relationship between climate governance and analyst coverage? Its effect on climate disclosure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 3445–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Even-Tov, O.; She, G.; Wang, L.L.; Yang, D.T. How government procurement shapes corporate climate disclosures, commitments, and actions. Rev. Account. Stud. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, C.; Benlemlih, M.; Ouadghiri, I.E.; Peillex, J. Does policy uncertainty affect non-financial disclosure? Evidence from climate change-related information. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 29, 4613–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares-Rodríguez, M.C.; Gambetta, N.; García-Benau, M.A. Climate action information disclosure in Colombian companies: A regional and sectorial analysis. Urban Climate 2023, 51, 101626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Shen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, J. External pressure, corporate governance, and voluntary carbon disclosure: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, S.; Gong, Y.; Görg, H. What determines innovation activity in Chinese state-owned enterprises? The role of foreign direct investment. World Dev. 2009, 37, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Kim, J.D.; Bae, S.M. Determinants of global banks’ climate information disclosure with the moderating effect of shareholder litigation risk. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, R.Q.; Ma, T. A Study on the Quality and Determinants of Climate Information Disclosure of A-Share-Listed Banks. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouloukoui, D.; Gomes, S.M.d.S.; Marinho, M.M.d.O.; Torres, E.A.; Kiperstok, A.; Jong, P.d. Disclosure of climate risk information by the world’s largest companies. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2018, 23, 1251–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, B.; Houqe, M.N.; Zaman, M. Climate governance effects on carbon disclosure and performance. Br. Account. Rev. 2020, 52, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, P.F.A.; Harris, P.; Caykoylu, S. The impact of corporate characteristics on climate governance disclosure. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; Deegan, C.; Inglis, R. Demand for, and impediments to, the disclosure of information about climate change-related corporate governance practices. Account. Bus. Res. 2016, 46, 620–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Michelon, G.; Patten, D.M. Impression Management in Sustainability Reports: An Empirical Investigation of the Use of Graphs. Account. Public Interest 2012, 12, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S. What comes next: Responding to recommendations from the task force on climate-related financial disclosures (TCFD). APPEA. J. 2018, 58, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.X. Status Quo and Improvement Path of Social Responsibility Information Disclosure in Corporate Development Management. Adv. Econ. Manag. Politics Sci. 2023, 3, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyono, S.; Harymawan, I.; Djajadikerta, H.G.; Noman, A.H.M. Corporate business strategy, CEO’s managerial ability, and environmental disclosure: The perspective of stakeholder theory. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 8149–8189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, A.; Karaman, A.S.; Kilic, M. Is corporate social responsibility reporting a tool of signaling or greenwashing? Evidence from the worldwide logistics sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosbois, D.; Fennell, D.A. Determinants of climate change disclosure practices of global hotel companies: Application of institutional and stakeholder theories. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Shang, C.; Li, D. Who benefits from corporate social responsibility in the presence of environmental externalities? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J. Toward sustainable port development: An empirical analysis of China’s port industry using an ESG framework. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, J.; Strzałka, D. On the Monte Carlo weights in multiple criteria decision analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.X.; Liu, Q.M.; Zhu, J.Z. Risk Assessment and Zonation of Roof Water Inrush Based on the Analytic Hierarchy Process, Principle Component Analysis, and Improved Game Theory (AHP–PCA–IGT) Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoni, A.; Kiseleva, E.; Terzani, S. Evaluating the Intra-Industry Comparability of Sustainability Reports: The Case of the Oil and Gas Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Wei, Z.W.; Wang, B.H.; Han, X.P. Measuring mixing patterns in complex networks by Spearman rank correlation coefficient. Phys. A 2016, 451, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MF (Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China). 2024 Letter on Seeking Opinions on the “Sustainable Disclosure Standards for Corporations-Basic Standards (Draft for Public Consultation)”. Available online: https://kjs.mof.gov.cn/gongzuotongzhi/202405/t20240527_3935674.htm (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Wu, H.; Deng, H.; Gao, X.C. Corporate coupling coordination between ESG and financial performance: Evidence from China’s listed companies. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 107, 107546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEPA (State Environmental Protection Administration). Announcement on Enterprise Environmental Information Disclosure. 2003. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/zj/wj/200910/t20091022_172224.htm (accessed on 2 September 2003).

- MEE (Ministry of Ecology and Environment the People’s Republic of China). Cooperation Agreement on Jointly Carrying Out Environmental Information Disclosure for Listed Companies. 2017. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/sthjbgw/qt/201706/t20170612_415876.htm (accessed on 12 June 2017).

- CSRC (China Securities Regulatory Commission). China Securities Regulatory Commission Announcement [2017] No. 17. 2017. Available online: http://www.csrc.gov.cn/csrc/c101802/c1004861/content.shtml (accessed on 26 December 2017).

- MEE (Ministry of Ecology and Environment the People’s Republic of China). Reform Plan for the System of the Law-based Disclosure of Environmental Information. 2021. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk03/202105/t20210525_834444.html (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- MEE (Ministry of Ecology and Environment the People’s Republic of China). Measures for the Administration of the Law-Based Disclosure of Environmental Information by Enterprises. 2021. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gzk/gz/202112/t20211210_963770.shtml (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- MEE (Ministry of Ecology and Environment the People’s Republic of China). Format Standards for the Law-Based Disclosure of Environmental Information by Enterprises. 2021. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk05/202201/t20220110_966488.html (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- CSRC (China Securities Regulatory Commission). Work Guidelines for the Investor Relations Management of Listed Companies. 2022. Available online: http://www.csrc.gov.cn/csrc/c100028/c2334692/content.shtml (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- SASA (State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council). Work Program for Improving the Quality of Listed Companies Held by Central Enterprises. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-05/27/content_5692621.htm (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- CPCC; SC (the Communist Party of China Central Committee, the State Council). A Guideline on Boosting the Growth of the Private Economy. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/ (accessed on 14 July 2023).

| Themes | Specific Keywords | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Governance | Environmental Policy/Environmental Management Policy | EP |

| Board Oversight, Supervision, Governance, Management/Management Oversight, Supervision, Governance, Management | BS | |

| Governance Structure | GS | |

| Management Responsibility | MR | |

| Employee Rewards/Employee Incentives/Employee Benefits/Employee Development | EMR | |

| Strategy | Climate Risks/Climate Opportunities | CR |

| Strategy and Decision Making/Transition Plans/Development Plans/Business Models | SD | |

| Value Chain Management/Supply Chain Management | SCM | |

| Climate Scenarios/Climate Adaptation/Climate Change Recovery/Climate Change Transformation | CS | |

| Risk Management | Climate Risk Identification | CRI |

| Climate Risk Assessment | CRA | |

| Climate Risk Monitoring | CRM | |

| Climate Risk Control | CRC | |

| Climate Risk Management | CRN | |

| Climate Risk Impacts | CRP | |

| Metrics and Targets | Emission Reduction Actions/Measures | ERA |

| Energy Consumption/Water Use/Land Use/Waste Management | RC | |

| Scope 1 (i) | S1 | |

| Scope 2 (ii) | S2 | |

| Scope 3 (iii) | S3 | |

| Low Carbon Products | LCP | |

| Low Carbon Investments | LCI | |

| Carbon Trading/Carbon Pricing/Carbon Credits | CT | |

| Biodiversity/Ecological Impacts | EI | |

| GHG Emission Targets/GHG Reduction Targets/Carbon Emission Targets/Carbon Reduction Targets | GHG | |

| Emissions Performance/Environmental Performance | ER |

| Item | Indicator Variability | Indicator Conflict | Amount of Information | Weighting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completeness | 0.194 | 3.307 | 0.641 | 20.64% |

| Balance | 0.278 | 2.557 | 0.710 | 22.87% |

| Reliability | 0.366 | 2.547 | 0.931 | 29.97% |

| Understandability | 0.343 | 2.399 | 0.824 | 26.52% |

| CCDQI | Completeness | Balance | Reliability | Understandability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCDQI | 1 | ||||

| Completeness | 0.737 ** | 1 | |||

| Balance | 0.724 ** | 0.522 ** | 1 | ||

| Reliability | 0.627 ** | 0.282 ** | 0.226 ** | 1 | |

| Understandability | 0.810 ** | 0.621 ** | 0.439 ** | 0.301 ** | 1 |

| Year | Policy | Practice |

|---|---|---|

| 2003 [59] | “Announcement on Enterprise Environmental Information Disclosure” | Initial explorations in environmental information disclosure by corporations. |

| 2017 [60] | “Cooperation Agreement on Jointly Carrying Out Environmental Information Disclosure for Listed Companies” | Promoting the establishment of a mandatory environmental information left system for listed companies. |

| 2017 [61] | “CSRC Announcement [2017] No. 17” | Encourage corporations to take the initiative to disclose their efforts to actively fulfill their social responsibilities, taking into account the characteristics of their industries. |

| 2021 [62] | “Reform Plan for the System of the Law-based Disclosure of Environmental Information” | Promote the mandatory disclosure of environmental information by corporations and improve the working norms for the participation of third-party organizations. |

| 2021 [63] | “Measures for the Administration of the Law-based Disclosure of Environmental Information by Enterprises” | Clear disclosure of information relating to the climate change response of projects for which financing is provided. |

| 2021 [64] | “Format Standards for the Law-based Disclosure of Environmental Information by Enterprises” | Refinement of the content and format of the legal disclosure of corporate environmental information. |

| 2022 [65] | “Work Guidelines for the Investor Relations Management of Listed Companies” | Encouraging listed companies to disclose ESG information. |

| Year | Policy |

|---|---|

| 2013 | Voluntary disclosure recommendations for listed corporations, “Environmental, Social and Governance Reporting Guidelines” |

| 2018 | “Green Finance Strategy Framework” to strengthen the disclosure of climate-related information by listed corporations |

| 2019 | Implement the principle of “no disclosure without justification” |

| 2021 | Release the “Guidance on Climate-related Disclosures”, benchmarking against the international standard TCFD, and emphasizing the need for corporations to raise their focus on climate change-related risks |

| 2023 | Propose to amend the “Environmental, Social and Governance Reporting Guidelines” to enhance the mandatory nature of CCD and transparency |

| Upstream | Midstream | Downstream | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 0.3092 | 0.3069 | 0.2864 |

| 2022 | 0.3575 | 0.3476 | 0.3333 |

| 2023 | 0.4023 | 0.4245 | 0.4143 |

| Framework | Indicators | Disclosure |

|---|---|---|

| Governance | EP | (1) Description of environment-related policies formulated by the corporation in accordance with the state * (2) Description of environment-related policies formulated by the corporation on its own * |

| BS | (1) Description of the work of the board of directors/governance in terms of responsibility checking, periodic review, and progress follow-up of work related to environmental management, climate governance, ESG, etc. * (2) The Board of Directors/Governance takes a position on significant resolutions related to environmental management, climate governance, and ESG | |

| GS | (1) Description of roles and responsibilities of each management level in environmental management, climate governance, ESG management * (2) Description of governance framework: ESG Committee, Environmental Work Leadership Group, etc. * | |

| MR | (1) Responding to Stakeholders’ Demands on Environmental Protection, Climate Governance, etc. * (2) Identify significant issues in the environmental field (3) Participation in local infrastructure environmental governance (4) Participate in developing industry standards related to the environment | |

| EMR | (1) Employee compensation linked to environmental indicators (2) Employee training and promotion of green thinking, climate change, ESG, etc. | |

| Strategy | CR | (1) Identification of the organization’s short-, medium-, and long-term climate risks (physical and transformation risks) and response measures (2) Opportunities arising from climate risks faced by the organization (3) Impacts of climate risk on the organization—financial impacts |

| SD | (1) Organizational low-carbon transition business development layout/path planning (2) Climate strategy/ESG strategy description (3) Environmental protection strategy cooperation—universities, corporations, and governments * | |

| SCM | (1) Assessment of suppliers’ environmental performance and environmental management qualification system (2) Preparation of environmental standards for each link in the supply chain of corporations | |

| CS | (1) Strategic resilience of the organization under different climate scenarios | |

| Risk Management | CRI | (1) Carbon footprint study (2) ESG climate risk |

| CRA | (1) Climate risk modeling | |

| CRM | - | |

| CRC | - | |

| CRN | (1) Climate change risk management team (2) Description of environmental/climate risk management system—ISO | |

| CRP | (1) Improvement and evaluation of environmental/climate risk management systems | |

| Metrics and Targets | ERA | (1) Specific description of actions/measures taken to reduce emissions * (2) Collaboration with universities, corporations, government, etc. |

| RC | (1) Indicators related to energy consumption, water, land use, and waste management * (2) Description of specific practice cases * (3) Zero-carbon parks | |

| S1 | (1) Quantification of Scope 1 GHG emissions * (2) Accounting standards used | |

| S2 | (1) Quantification of Scope 2 GHG emissions * (2) Accounting standards used | |

| S3 | (1) Quantitative Scope 3 GHG emissions (2) Accounting standards used | |

| GHG | (1) Quantification of the target value of each GHG emission/reduction set by corporations | |

| LCI | (1) Amount of the organization’s investment in environmental protection and governance (2) Description of the invested environmental protection projects and their effectiveness | |

| CT | (1) Descriptive representation of the organization’s participation in the indicator (2) Quantifying the amount of transactions (3) Green power consumption trading, carbon sinks, carbon inclusion, and blue bonds | |

| EI | (1) Actions and measures taken * (2) Description of relevant cases * (3) Impact assessment—environmental impact assessment of projects, assessment of potential impacts on biodiversity (4) Publication of Biodiversity Conservation Report | |

| LCP | (1) Patents and technologies (2) Cooperation with universities and other organizations | |

| ER | (1) Expression of importance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pang, X.; Zhang, P.; Guo, Z.; Jia, X.; Tan, R.R.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, X. Information Disclosure in the Context of Combating Climate Change: Evidence from the Chinese Natural Gas Industry. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104315

Pang X, Zhang P, Guo Z, Jia X, Tan RR, Zhang Y, Qu X. Information Disclosure in the Context of Combating Climate Change: Evidence from the Chinese Natural Gas Industry. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104315

Chicago/Turabian StylePang, Xufei, Peidong Zhang, Zhen Guo, Xiaoping Jia, Raymond R. Tan, Yanmei Zhang, and Xiaohan Qu. 2025. "Information Disclosure in the Context of Combating Climate Change: Evidence from the Chinese Natural Gas Industry" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104315

APA StylePang, X., Zhang, P., Guo, Z., Jia, X., Tan, R. R., Zhang, Y., & Qu, X. (2025). Information Disclosure in the Context of Combating Climate Change: Evidence from the Chinese Natural Gas Industry. Sustainability, 17(10), 4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104315