Expanding Geoethics: Interrelations with Geoenvironmental Education and Sense of Place

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Merging Geoethics, Geoenvironmental Education, and Sense of Place in a Common Context

1.2. Objective of This Review Article

- Research question 1. What research topics and themes are covered in the spectrum of geoethics in relation to geoenvironmental education in global databases?

- Research question 2. Is there a research link between geoethics and sense of place?

- Research question 3. What are the research gaps in linking geoethics and sense of place?

- Research question 4. What are the future research directions regarding geoethics, geoenvironmental education, and sense of place?

2. Literature Review

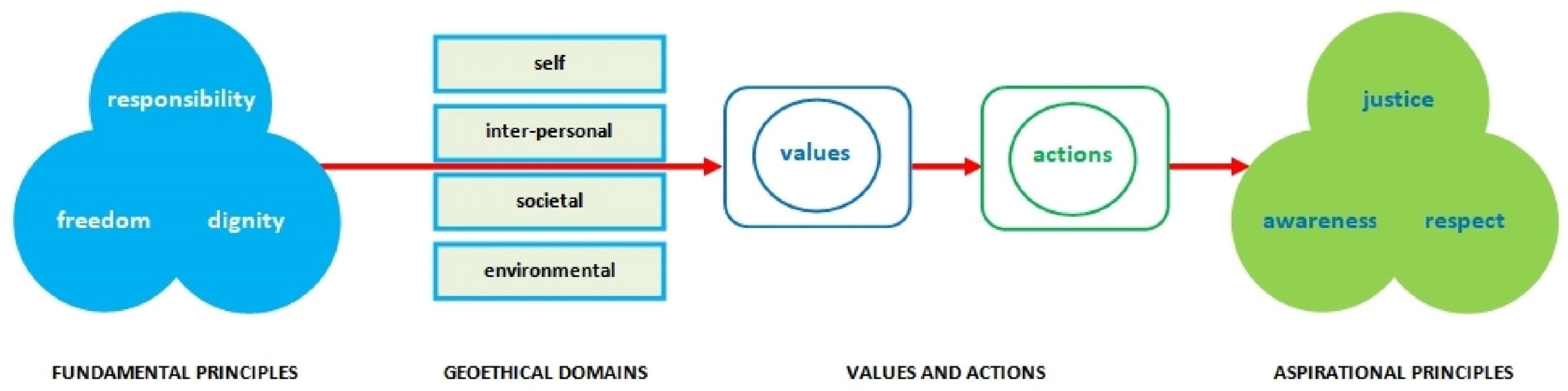

2.1. Geoethics: An Emerging Scientific Field

2.1.1. The Contemporary Role of Geosciences in Geocoservation

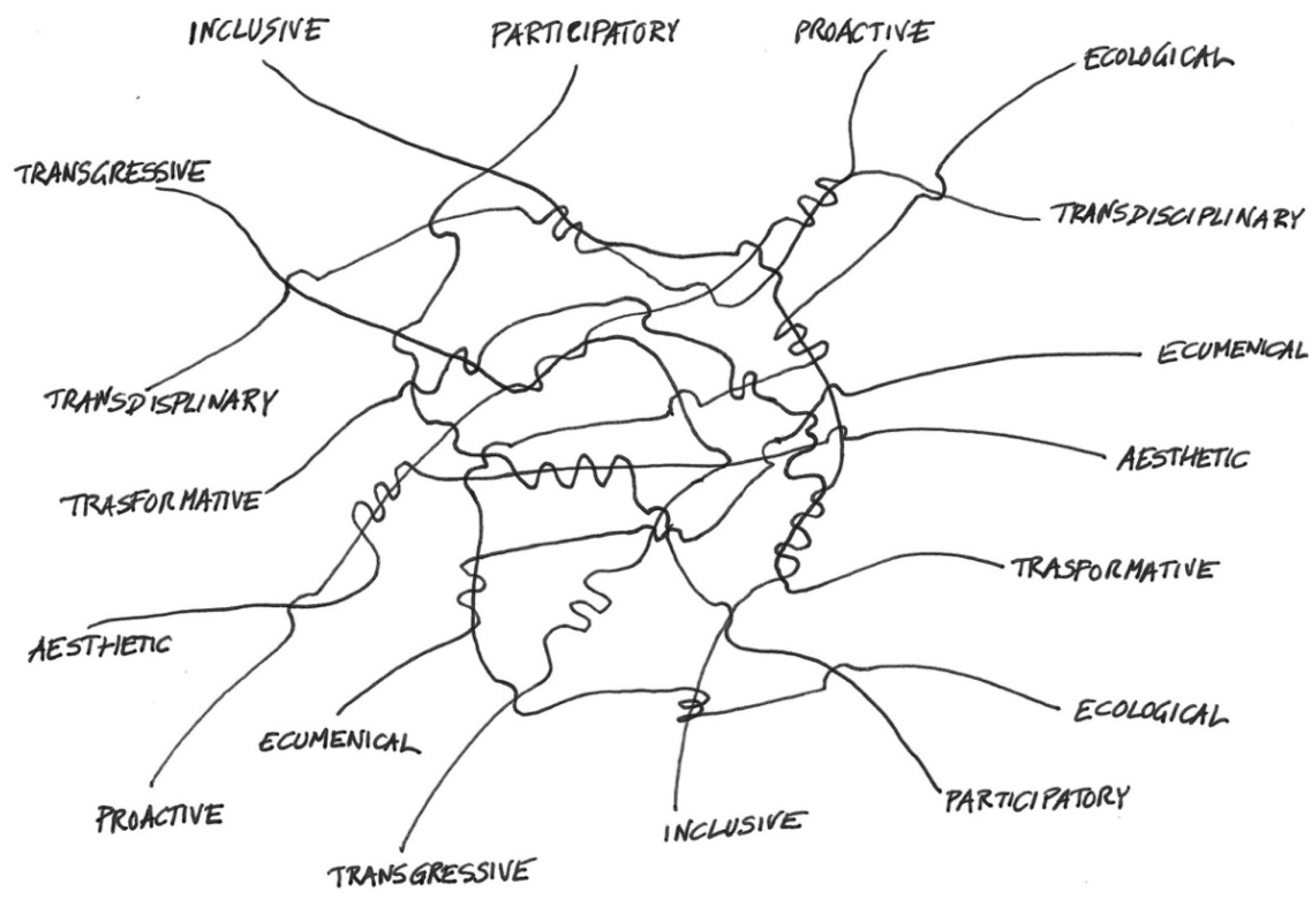

2.2. Current Approaches to Geoenvironmental Education

2.2.1. Geoeducation (Geoenvironmental Education) as an Aspect of Environmental Education

2.3. Linking Place to Geoenvironmental Education and Geoethics

2.3.1. The Significance of Place in Education

2.3.2. The Local Environment as a Teaching Context through Place-Based Education

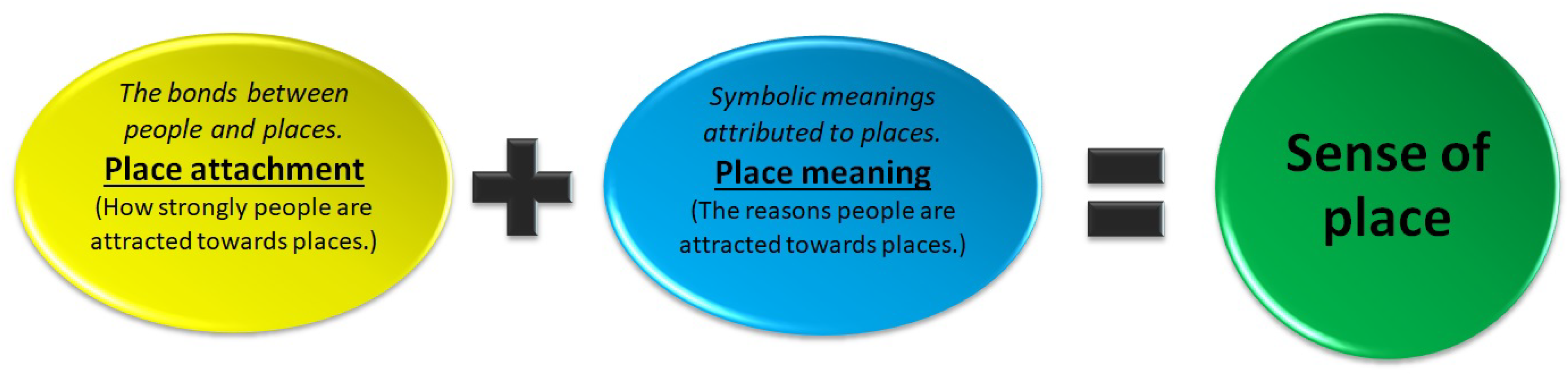

2.3.3. The Novel Outcome of the Sense of Place in Geoenvironmental Education

Research Insights on Sense of Place

3. Methodology

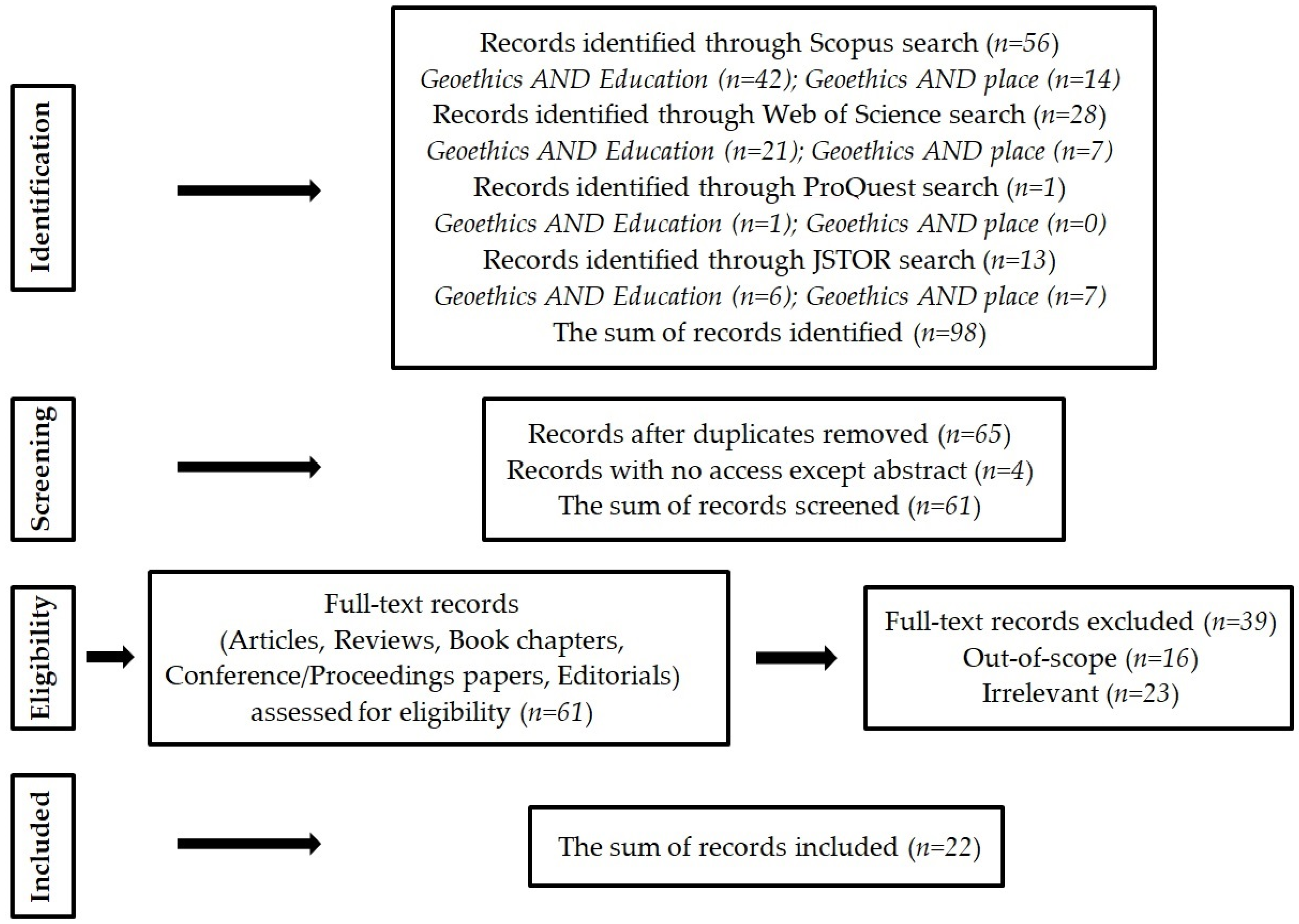

3.1. Overview of the Literature Search Process

3.2. Limitations

4. Results

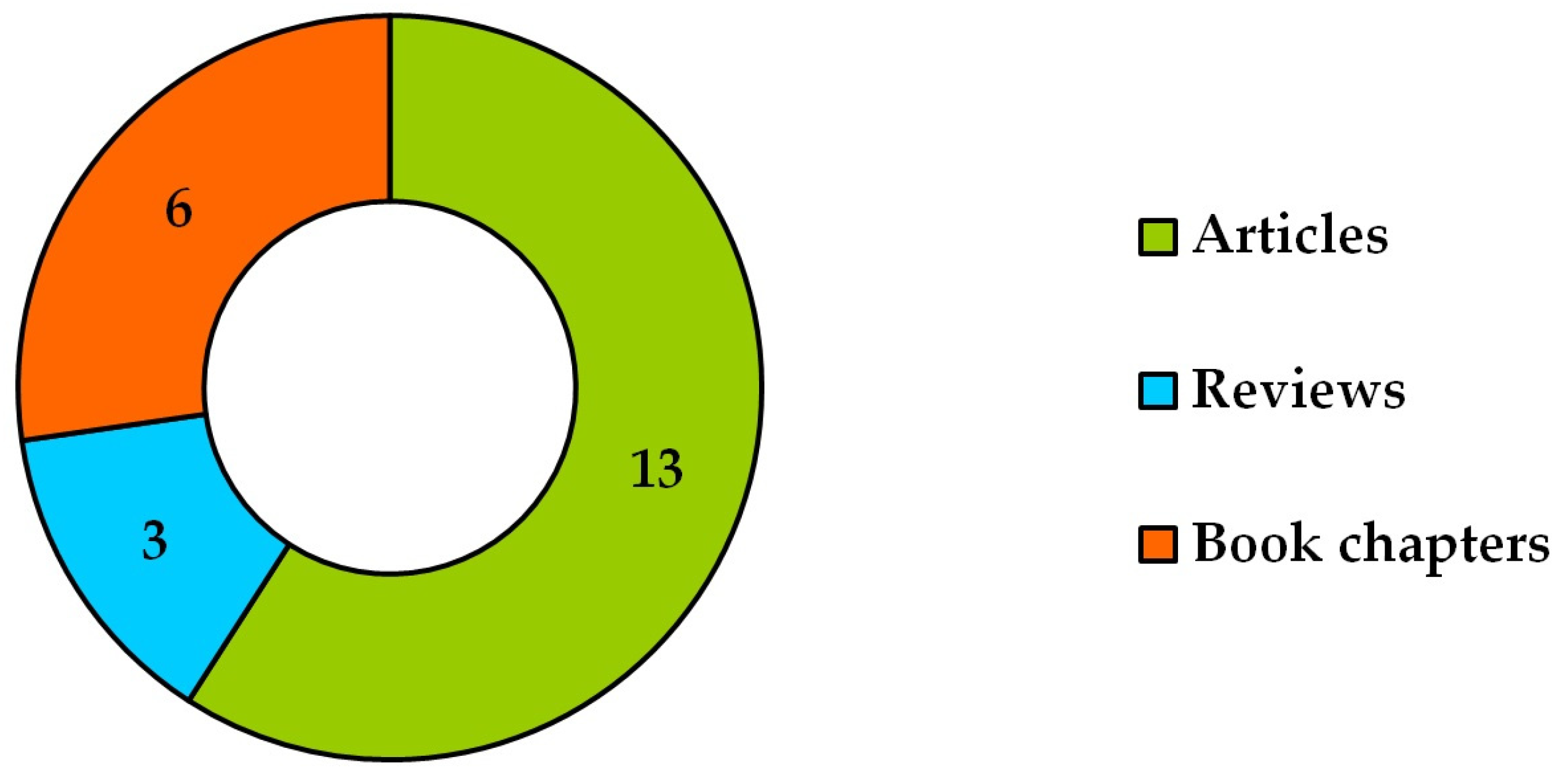

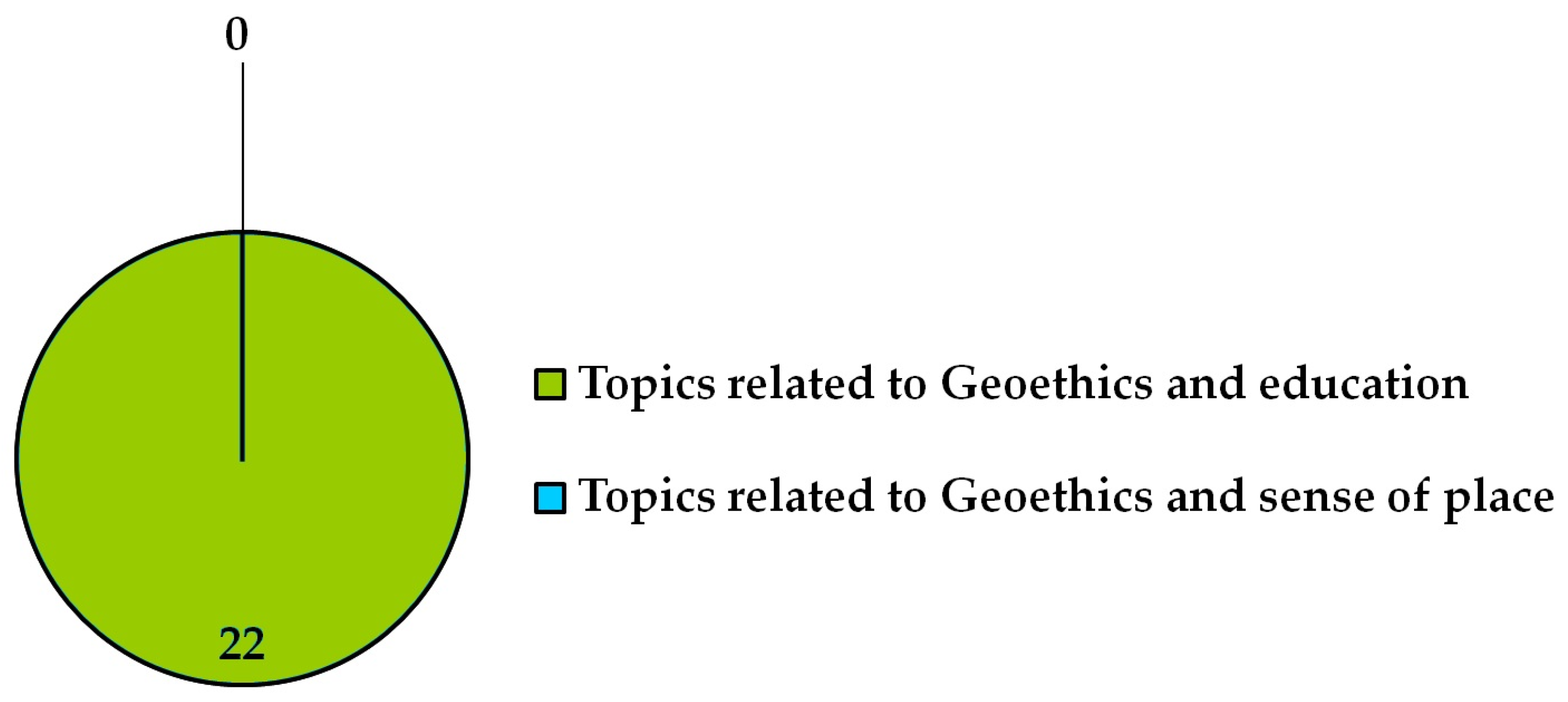

4.1. Overview of Records on “Geoethics AND Education” and “Geoethics AND Place”

4.2. Descriptive Analysis of Existing Records in a Nutshell

5. Discussion

5.1. Integrating Geoethical Considerations into the Geosciences and Geoenvironmental Education

5.2. Summary of Key Findings from This Review

5.3. Identification of Research Gaps

5.4. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gray, M. The Confused Position of the Geosciences within the “Natural Capital” and “Ecosystem Services” Approaches. Ecos. Serv. 2018, 34, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoullos, M.; Alambei, B.; Kouroutos, B.; Malotidi, M.; Mantzara, M.; Psallidas, B. (Eds.) Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development in Protected Areas: Educational Material; MIO-ECSDE: Athens, Greece, 2008; (In Greek). Available online: http://mio-ecsde.org/epeaek09/book/perivallontikiekpaidefsi.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Krasny, M.E. Advancing Environmental Education Practice; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://d119vjm4apzmdm.cloudfront.net/open-access/pdfs/9781501747083.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Peppoloni, S.; Di Capua, G. Geoethics and Geological Culture: Awareness, Responsibility and Challenges. Reflections from the Geoitalia Conference 2011. Ann. Geophys. 2012, 55, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppoloni, S.; Di Capua, G. Geoethics. Manifesto for an Ethics of Responsibility towards the Earth; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.E. Geoconservation Principles and Protected Area Management. Intern. J. Geoh. Parks 2019, 7, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Vasconcelos, C. Geoethics: Master’s Students Knowledge and Perception of Its Importance. Res. Sci. Educ. 2015, 45, 889–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brihla, J.; Gray, M.; Pereira, D.I.; Pereira, P. Geodiversity: An Integrative Review as a Contribution to the Sustainable Management of the Whole Nature. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 86, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.E.; Barron, H.F.; Hansom, J.D.; Thomas, M.F. Engaging with Geodiversity—Why it Matters. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2012, 123, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M. Geodiversity-Linking People, Landscapes and Their Culture. Natural and Cultural Landscapes-the Geological Foundation. pp. 45–52. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285890010_Geodiversity_-_linking_people_landscapes_and_their_culture (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Emerson, R.W. Nature; James Monroe and Company: Boston, MA, USA; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. The Project Gutenberg; (Original work published 1849); Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/29433/29433-h/29433-h.htm (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Bohle, M.; Marone, E. Geoethics, a Branding for Sustainable Practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods. Saving Our Children from Nature Deficit Disorder; Atlantic Books: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox, D.; Nagendra, H.; Elmqvist, T.; Russ, A. Advancing Urbanization. In Urban Environmental Education Review; Russ, A., Krasny, M.E., Eds.; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Decade for Education for Sustainable Development. 2005. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-sustainable-development/what-is-esd/un-decade-of-esd (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. 2017. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Vasconcelos, C.; Orion, N. Earth Science Education as a Key Component of Education for Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinia, H.; Voudouris, P.; Antonarakou, A. Editorial of special issue—Geoheritage and Geotourism resources: Education, Recreation, Sustainability. Geosciences 2022, 12, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinia, H.; Voudouris, P.; Antonarakou, A. Geoheritage and Geotourism Resources: Education, Recreation, Sustainability II. Geosciences 2023, 13, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Capua, G.; Peppoloni, S.; Bobrowsky, P.T. The Cape Town Statement on Geoethics. Ann. Geophys. 2017, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUGS (International Union of Geological Sciences). The First 100 IUGS Geological Heritage Sites. October 2022. Available online: https://iugs-geoheritage.org/videos-pdfs/iugs_first_100_book.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Orr, D.W. Ecological Literacy: Education and the Transition to a Postmodern World; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, D.W. Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect; Island Press: Washington DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sanger, M. Sense of Place: Its Meaning and Its Implications for Education. Master’s Thesis, The University of Montana, Missoula, MT, USA, 1994. Available online: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/7906/ (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Williams, D.; Vaske, J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, D.; Sowers, J. Place and Placelessness (1976): Edward Relph. In Key Texts in Human Geography; Hubbard, P., Kitchin, R., Valentine, G., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2008; pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withrow-Clark, R.; Konrad, J.; Siddall, K. Sense of Place and Interpretation. In Urban Environmental Education; Russ, A., Ed.; Cornell University Civil Ecology Lab, NAAEE & EE Capacity: Ithaca, NY, USA; Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Foote, K.E.; Azaryahu, M. Sense of place. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenborn, B. Effects of Sense of Place on Responses to Environmental Impacts: A Study among Residents in Svalbard in the Norwegian High Arctic. Appl. Geogr. 1998, 18, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R. Toward a Social Psychology of Place: Predicting Behavior from Place-Based Cognitions, Attitude, and Identity. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Mean or Green: Which Values Can Promote Stable Pro-Environmental Behavior? Conserv. Lett. 2008, 2, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.J.; Chapman, R. Thinking Like a Park: The Effects of Sense of Place, Perspective-Taking, and Empathy on Pro-Environmental Intentions. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2003, 21, 71–86. Available online: https://js.sagamorepub.com/index.php/jpra/article/view/1492 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Ardoin, N. Toward an Interdisciplinary Understanding of Place: Lessons for Environmental Education. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2006, 11, 112–126. Available online: https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/508 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Kudryavtsev, A.; Stedman, R.; Krasny, M. Sense of Place in Environmental Education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtsev, A.; Krasny, M.; Stedman, R. The Impact of Environmental Education on Sense of Place among Urban Youth. Ecosphere 2012, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemer, W.F.; Larson, L.R.; Decker, D.J.; Stedman, R.C.; Cooper, C.; Doyle-Capitman, C.; Seekamp, E. Measuring Complex Connections between Conservation and Recreation: An Overview of Key Indicators. Hum. Dimens. Res. Unit Publ. Ser. 2017. Available online: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/8496aa28-8fae-4fa2-9dc5-d143463e6be7/content (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Peppoloni, S.; Di Capua, G. The Meaning of Geoethics. In Ethical Challenges and Case Studies in Earth Sciences; Wyss, M., Peppoloni, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promduangsri, P.; Crookall, D. Geoethics Education: From Theory to Practice—A Case Study. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2020, Online, 4–8 May 2020. EGU2020-4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, D. Place-Based Education: Connecting Classrooms and Communities, 2nd ed.; The Orion Society: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- NAAEE (North American Association for Environmental Education). Guidelines for Excellence: K-12 Environmental Education. For Educators, Administrators, Policy-Makers and the Public. Available online: https://eepro.naaee.org/resource/environmental-education-materials-guidelines-excellence (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Li, W.T.; Shein, P.P. Developing Sense of Place through a Place-Based Indigenous Education for Sustainable Development Curriculum. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 29, 692–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, H. The Restoration of a Sense of Place: A Theological Reflection on the Visual Environment. Ekistics 1968, 25, 422–424. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43616752 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Stedman, R. Is It Really Just a Social Construction?: The Construction of the Physical Environment to Sense of Place. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Capua, G.; Peppoloni, S. Defining Geoethics. Website of the International Association for Promoting Geoethics. Available online: https://www.geoethics.org/definition (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Peppoloni, S.; Di Capua, G. Geoethics to Start Up a Pedagogical and Political Path towards Future Sustainable Societies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppoloni, S.; Di Capua, G. Theoretical Aspects of Geoethics. In Teaching Geoethics; Resources for Higher Education; Vasconcelos, C., Schneider-Voß, S., Peppoloni, S., Eds.; U. Porto Edições: Porto, Portugal, 2020; pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbaudo, A.; Tonon, M.D. Words as Stones for Geoethical Glossary. J. Geoethics Soc. Geosc. 2023, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orion, N. The Relevance of Earth Science for Informed Citizenship: Its Potential and Fulfilment. In Contextualizing Teaching to Improving Learning: The Case of Science and Geography; Leite, L., Dourado, A., Afonso, S., Morgado, S., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326110889_The_relevance_of_earth_science_for_informed_citizenship_Its_potential_and_fulfillment (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- The Geological Society of London. Poster “Geosciences for the Future”. Available online: https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/Posters (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Sharples, C. Concepts and Principles of Geoconservation. Australia: Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service Website. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266021113_Concepts_and_principles_of_geoconservation (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Henriques, M.H.; Reis, R.P.; Brihla, J.; Mota, T. Geoconservation as an Emerging Geoscience. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiropoulos, G.; Drinia, H.; Antonarakou, A.; Zouros, N. From Geoheritage to Geoeducation, Geoethics, and Geotourism: A Critical Evaluation of the Greek Region. Geosciences 2021, 11, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocx, M.; Semeniuk, V. Geoheritage and Geoconservation—History, Definition, Scope and Scale. J. R. Soc. West. Aust. 2007, 90, 53–87. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285012358_Geoheritage_and_geoconservation_-_History_definition_scope_and_scale (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Crofts, R. Promoting Geodiversity: Learning Lessons from Biodiversity. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2014, 125, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larwood, J.G.; Badman, T.; McKeever, P.J. The Progress and Future of Geoconservation at a Global Level. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2013, 124, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R.K. Global Geotourism—An Emerging Form of Sustainable Tourism. Czech J. Tour. 2013, 2, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapp, W. The Concept of Environmental Education. J. Environ. Educ. 1969, 1, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO-UNEP. The Belgrade Charter: A Framework for Environmental Education. 1977. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000017772 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- UNESCO-UNEP. Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education. 1978. Tbilisi. USSR, 14–26 October 1977. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000032763 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Huckle, J. Education for Sustainability: Assessing Pathways to the Future. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 1991, 30, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. Environmental Education for Sustainability: Defining the New Focus of Environmental Education in the 1990s. Environ. Educ. Res. 1995, 1, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Gough, A. The Emergence of Environmental Education: A “History” of the Field. In International Handbook of Research on Environmental Education; Stevenson, R., Brody, M., Dillon, J., Wals, A., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.; Hungerford, H.; Tomera, A. Analysis and Synthesis of Research on Responsible Environmental Behavior: A Meta-analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1986, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, H.R.; Volk, T.L. Changing Learner Behavior through Environmental Education. J. Environ. Educ. 1990, 21, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.B.; Schnack, K. The Action Competence Approach in Environmental Education. Environ. Educ. Res. 1997, 3, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, F.; Schnack, K. The Action Competence and the “New” Discourses of Education for Sustainable Development, Competence, and Quality Criteria. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to Pro-environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.B. Knowledge, Action and Pro-environmental Behaviour. Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Cooper, C.B.; Stedman, R.C.; Decker, D.J.; Gagnon, R.J. Place-Based Pathways to Proenvironmental Behavior: Empirical Evidence for a Conservation-Recreation Model. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2018, 31, 871–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiting, S. School Development and Engagement—Is Mental Ownership the Holy Grail of Education for Sustainable Development? In Environmental and School Initiatives: Lessons from the ENSI Network—Past, Present and Future; Affolter, C., Varga, A., Eds.; Environment and School Initiatives, Vienna and Eszterhazy University: Budapest, Hungary, 2018; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/39271313/ENVIRONMENT_AND_SCHOOL_INITIATIVES_Lessons_from_the_ENSI_Network_Past_Present_and_Future (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Wojcik, D.; Biedenweg, K.; McConnell, L.; Iyer, G. Current Trends in Environmental Education. In Environmental and School Initiatives: Lessons from the ENSI Network—Past, Present and Future; Affolter, C., Varga, A., Eds.; Environment and School Initiatives, Vienna and Eszterhazy University: Budapest, Hungary, 2016; Available online: https://ensi.org/global/downloads/Publications/438/Lessons_from_the_ENSI_Network.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Hollweg, K.S.; Taylor, J.R.; Bybee, R.W.; Marcinkowski, T.J.; McBeth, W.C.; Zoido, P. Developing a Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy; North American Association for Environmental Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: https://cdn.naaee.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/devframewkassessenvlitonlineed.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Carter, R.L.; Simmons, B. The History and Philosophy of Environmental Education. In The Inclusion of Environmental Education in Science Teacher Education; Bodzin, A., Shiner Klein, B., Weaver, S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Gaillard, E. Environmental Education Outcomes for Conservation: A Systematic Review. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flogaiti, E.; Liarakou, G.; Gavrilakis, K. Participatory Teaching and Learning Methods. Applications in Environmental and Sustainability Education; Pedio: Athens, Greece, 2021. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Peppoloni, S.; Bilham, N.; Di Capua, G. Contemporary Geoethics within the Geosciences. In Exploring Geoethics. Ethical Implications, Societal Contexts, and Professional Obligations of the Geosciences; Bohle, M., Ed.; Palgrave Pivot: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelson, D.C. Geo-Literacy. National Geographic. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/article/geo-literacy-preparation-far-reaching-decisions (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Alvarez, R.F. Geoparks and Education: UNESCO Global Geopark Villuercas-Ibores-Jara as a Case Study in Spain. Geosciences 2020, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A. Environment and Environmental Education: Conceptual Issues and Curriculum Implications. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 1972. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED068371.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Tormey, D. New Approaches to Communication and Education through Geoheritage. Intern. J. Geoh. Parks 2019, 7, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulou-Katsani, D.; Koskolou, A.; Mitsis, P.; Pavlikakis, G.; Fermeli, G. Application Guide of the Curriculum: “Environment and Education for Sustainable Development”; Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, Institute for Education Policy: Athens, Greece, 2014; (In Greek). Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10795/1855 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Dewey, J. The School and Society. The Child and the Curriculum; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017/1900. (Original work published 1900); Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/53910/53910-h/53910-h.htm (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Gieryn, T. A Space for Place in Sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2000, 26, 463–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenewald, D.A. Foundations of Place: A Multidisciplinary Framework for Place-conscious Education. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 40, 619–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semken, S.; Brandt, E. Implications of Sense of Place and Place-Based Education for Ecological Integrity and Cultural Sustainability in Diverse Places. In Cultural Studies and Environmentalism: The Confluence of Eco-Justice, Place-Based (Science) Education, and Indigenous Knowledge Systems; Tippins, D., Mueller, M., van Eijck, M., Adams, J., Eds.; Cultural Studies of Science Education (3); Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveraki, M.; Pantazis, B.E. An Anthropological-pedagogical View of Place-Based Environmental Education. In Environmental Education and Communication; Manolas, E., Tsantopoulos, G., Eds.; Topics in Forestry & Environmental and Natural Resource Management; Department of Forestry and Environmental and Natural Resources Management, Democritus University of Thrace: Orestiada, Greece, 2016; Volume 8, (In Greek). Available online: https://them-daso.fmenr.duth.gr/index.php/2020/08/24/anthropologiki-paidagogiki-theorisi/ (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Gruenewald, D.A. The Best of Both Worlds: A Critical Pedagogy of Place. Environ. Educ. Res. 2003, 14, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Ark, T.; Liebtag, E.; McClennen, N. The Power of Place. Authentic Learning through Place-Based Education; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, 8th ed.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/19846369/Yi_Fu_Tuan_Space_and_Place (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Cross, J.E. What Is Sense of Place? Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10217/180311 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Leou, M.; Kalaitsidaki, M. Cities as Classrooms. In Urban Environmental Education Review; Russ, A., Krasny, M., Eds.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, O.M.; McCann, E.P.; Liddicoat, K. Inclusive Education. In Urban Environmental Education Review; Russ, A., Krasny, M., Eds.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resor, C.W. Place-Based Education: What Is Its Place in the Social Studies Classroom? Soc. Stud. 2010, 101, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, M. A Place Pedagogy for “Global Contemporaneity”. Educ. Philos. Theory 2010, 42, 326–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, L. The Place of Place-Based Education in the Australian Primary Geography Curriculum. Geogr. Educ. 2015, 28, 41–49. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1085985 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Stevenson, R. A Critical Pedagogy of Place and the Critical Place(s) of Pedagogy. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.A.; Sobel, D. Place- and Community-Based Education in Schools; Taylor & Francis: Exeter, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.; Duffin, M.; Murphy, M. Quantifying a Relationship between Place-Based Learning and Environmental Quality. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhouse, J.L.; Knapp, C.E. Place-Based Curriculum and Instruction: Outdoor and Environmental Education Approaches; ERIC Digest 2000, ERIC Clearinghouse for Rural Education and Small Schools: Charleston, WV, USA, 2020. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED448012 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Kemp, A.T. Engaging the Environment: A Case for a Place-Based Curriculum. Curric. Teach. Dial. 2006, 8, 125–142. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1629868/Engaging_the_Environment_A_Case_for_a_Place_based_Education (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Morgan, A. Place-Based Education in the Global Age: Local Diversity. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 521–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.A. Place-Based Education: Breaking through the Constraining Regularities of Public School. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, A. If We All Go Global, What Happens to the Local? In Defense of a Pedagogy of Place. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Comparative and International Education Society, Toronto, ON, Canada, 15 April 1999; Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED434796.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Gruenewald, D.A.; Smith, G.A. Place-Based Education in the Global Age: Local Diversity; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.A. Place-Based Education: Learning to be Where We Are. Phi Delta Kappan 2002, 83, 548–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, A. An Evaluation of Four Place-Based Education Programs. J. Environ. Educ. 2004, 35, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posch, P. Curriculum Change and School Development. Environ. Educ. Res. 1996, 2, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, V. Environmental Education and School. A Timeless View, 5th ed.; Tipothito, G. Dardanos: Athens, Greece, 1998. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Ontog, K.; Le Grange, L. The Role of Place-Based Education in Developing Sustainability as a Frame of Mind. S. Afr. J. Environ. Educ. 2014. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/sajee/article/view/121962 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Clayton, S. Environmental Identity: A Conceptual and an Operational Definition. In Identity and the Natural Environment: The Psychological Significance of Nature; Clayton, S., Opotow, S., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 45–65. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289100768_Environmental_identity_A_conceptual_and_operational_defi_nition (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Charlot, J.; Leck, C.; Saxberg, B. Designing for Learning: A Synthesis of Key Insights from the Science of Learning and Development; Transcend, Inc.: Hastings On Hudson, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://transcendeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/DesigningforLearningPrimer_Transcend_WebVersion_Feb_2020.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Gardner, H. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences, 3rd ed.; The Perseus Books Group: New York, NY, USA, 2011. (Original work published 1983). [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons in Theory and Practice, 2nd revised ed.; Ingram Publisher Services: New York, NY, USA, 2006. (Original work published 1993). [Google Scholar]

- Schlottmann, C. Introduction: Place-Based and Environmental Education. Ethics, Place Environ. J. Philos. Geogr. 2005, 8, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perceptions, Attitudes, and Values; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion Limited: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Derr, V. Children’s Sense of Place in Northern New Mexico. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, E.S. Between Geography and Philosophy: What Does It Mean to Be in Place World? Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2001, 91, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semken, S.; Freeman, C.B. Sense of Place in the Practice and Assessment of Place-Based Science Teaching. Sci. Educ. 2008, 92, 1042–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.; Stedman, R. Sense of Place as an Attitude: Lakeshore Owners Attitudes toward Their Properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.D. Theorizing a Sense of Place in a Transnational Community. Child. Youth Environ. 2013, 23, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.; Ahn, J.J.; Corley, E.A. Sense of Place: Trends from the Literature. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2020, 13, 236–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semken, S.; Freeman, C.B.; Watts, N.B.; Neakrase, J.J.; Dial, R.E.; Baker, D.R. Factors That Influence Sense of Place as a Learning Outcome and Assessment Measure of Place-Based Geoscience Teaching. Electron. J. Sci. Educ. 2009, 13, 136–159. Available online: https://ejrsme.icrsme.com/article/view/7803 (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Adams, J.D.; Greenwood, D.A.; Thomashow, M.; Russ, A. Sense of Place. In Urban Environmental Education Review; Russ, A., Krasny, M., Eds.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamai, S. Sense of Place: An Empirical Measurement. Geoforum 1991, 22, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M. The Social Construction of Tourist Places. Aust. Geogr. 1999, 30, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamai, S.; Ilatov, Z. Measuring Sense of Place: Methodological Aspects. Tijdschrift Voor Econom. Soc. Geogr. 2005, 96, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, C.; Gifford, R. The Relations between Natural and Civic Place Attachment and Pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Schuh, J.S.; Gould, R.K. Exploring the Dimensions of Place: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Data from Three Ecoregional Sites. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 583–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanzer, B. Measuring Sense of Place: A Scale for Michigan. Adm. Theory Prax. 2014, 26, 362–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.B.; Gonçalves, G.; Neves de Jesus, S. Measuring Sense of Place: A New Place-People-Time-Self Model. J. Tour. Sustain. Well-Being 2021, 9, 239–258. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/ris/jspord/1039.html (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Cheng, A.S.; Kruger, L.E.; Daniels, S.E. Place as an Integrating Concept in Natural Resources Politics: Propositions for a Social Science Research Agenda. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N. Exploring Sense of Place and Environmental Behavior at an Ecoregional Scale in Three Sites. Hum. Ecol. 2014, 42, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpenny, E. Pro-environmental Behaviours and Park Visitors: The Effect of Place Attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J.; Eisenhauer, B.; Stedman, R. Environmental Concern: Examining the Role of Place Meaning and Place Attachment. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddaway, A.P.; Wood, A.M.; Hedges, L.V. How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature Review as Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamsser, L.; Tetzlaff, J.E.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magagna, A.; Ferrero, E.; Giardino, M.; Lozar, F.; Perotti, L. A Selection of Geological Tours for Promoting the Italian Geological Heritage in Secondary Schools. Geoheritage 2013, 5, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascale, F.; D’ Amico, S. Historical Memory and Natural Hazards in Neogeographic Mapping Technologies. In The Digital Arts and Humanities; Travis, C., von Lünen, A., Eds.; Springer Geography: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.R.; Rocha, A.F.; Ferreira, J.A.; Rola, A. Field Classes for Geosciences Education: Teachers’ Concepts and Practices. In Geoscience Education; Vasconcelos, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, C.; Torres, J.; Vasconcelos, L.; Moutinho, S. Sustainable Development and Its Connection to Teaching Geoethics. Episodes 2016, 39, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, C.; Vasconcelos, M.L.; Torres, J. Education and Geoethics: Three Fictional Life Stories. In Geoscience Education; Vasconcelos, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascale, F.; Bernardo, M.; Muto, F.; Di Matteo, D.; Dattilo, V. Resilience and Seismic Risk Perception at School: A Geoethical Experiment in Aiello Calabro, Southern Italy. Nat. Hazards 2017, 86, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellaubi, F.; Lagunov, A. A Value-Based Approach in Managing the Human-Geosphere Relationship: The Case of Lake Turgoyak (Southern Urals, Russia). Hum. Ecol. 2020, 48, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, J.M. Geoethics in Higher Education of Hydrogeology. In Advances in Geoethics and Groundwater Management: Theory and Practice for a Sustainable Development; Abrunhosa, M., Chambel, A., Peppoloni, S., Chaminé, H.I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.; Orion, N.; Calheiros, C.; Vasconcelos, C. And if the Spring that Provides the Farm with Water Should Run Dry?—A Geoethical Case Applied in Higher Education. In Advances in Geoethics and Groundwater Management: Theory and Practice for a Sustainable Development; Abrunhosa, M., Chambel, A., Peppoloni, S., Chaminé, H.I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, G.P.; Pereira, H. Teaching Groundwater Resources and Geoethics in Portuguese Secondary Schools. In Advances in Geoethics and Groundwater Management: Theory and Practice for a Sustainable Development; Abrunhosa, M., Chambel, A., Peppoloni, S., Chaminé, H.I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgousis, E.; Savelides, S.; Mosios, S.; Holokolos, M.V.; Drinia, H. The Need for Geoethical Awareness: The Importance of Geoenvironmental Education in Geoheritage Understanding in the Case of Meteora Geomorphes, Greece. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgousis, E.; Savelidi, M.; Savelides, S.; Mosios, S.; Holokolos, M.V.; Drinia, H. How Greek Students Perceive Concepts Related to Geoenvironment: A Semiotics Content Analysis. Geosciences 2022, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbaudo, A.; Lozar, F.; Lasagna, M.; Tonon, M.D.; Egidio, E. Are We Ready for a Sustainable Development? A Survey among Young Geoscientists in Italy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handl, S.; Calheiros, C.S.C.; Fiebig, M.; Langergraber, G. Educational Resources for Geoethical Aspects of Water Management. Geosciences 2022, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, M.; Teixeira, I.; Lima, D. Are New Pandemics a Historical Fate of Human Evolution? Education and the Contribution from a Geoethical Perspective. Paedag. Histor. 2022, 58, 748–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procesi, M.; Di Capua, G.; Peppoloni, S.; Corirossi, M.; Valentinelli, A. Science and Citizen Collaboration as Good Example of Geoethics for Recovering a Natural Site in the Urban Area of Rome (Italy). Sustainability 2022, 14, 4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormey, D.; Dongying, W.; Aixia, F. Geoheritage Education as a Gateway to Developing a Conservation Ethic in High School Students from China and the USA. Geoheritage 2022, 14, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosios, S.; Georgousis, E.; Drinia, H. The Status of Geoethical Thinking in the Educational System of Greece: An Overview. Geosciences 2023, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyarko, S.C.; Fore, G.A.; Licht, K. The Role of Ethical Care in the Geosciences: Examining the Perspectives of Geoscience Undergraduates. J. Geosci. Educ. 2023, 71, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greek Legislation 1650/1986. For the Protection of the Environment. (F.E.K. A’ 160/10-16.10.1986). (In Greek). Available online: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/kat-periballon/n-1650-1986.html (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Tilden, F. Interpreting Our Heritage, 4th ed.; Expanded and Updated; The University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Living in the Earth. Towards an Education for our Times. J. Educ. Sust. Develop. 2010, 4, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity, Geoheritage and Geoconservation for Society. Intern. J. Geoh. Parks 2019, 7, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrowsky, P.; Cronin, V.; Di Capua, G.; Kieffer, S.; Peppoloni, S. The Emerging Field of Geoethics. In Scientific Integrity and Ethics: With Applications to the Geosciences; Special Publications 73; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 175–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). Guidelines for Protected Areas and Management Categories. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/efiles/documents/1994-007-En.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- UNESCO Global Geoparks. Website of UNESCO’s International Geoscience and Geoparks Programme. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/iggp/geoparks/about (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Koupatsiaris, A.A.; Drinia, H. Exploring Greek UNESCO Global Geoparks: A Systematic Review of Grey Literature on Greek Universities and Future Research Avenues for Sustainable Development. Geosciences 2023, 13, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Forum on Natural Capital. What is Natural Capital? Available online: https://naturalcapitalforum.com/about/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Taplin, D.H.; Clark, H. Theory of Change Basics. A Primer on the Theory of Change; ActKnowledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.theoryofchange.org/wp-content/uploads/toco_library/pdf/ToCBasics.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Nolet, V. Preparing Sustainability Literate Teachers. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2009, 111, 409–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, F.; Mayer, M. ECO-Schools Trends and Divergences. A Comparative Study on ECO-School Development Processes in 13 Countries; Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture in collaboration with “Environment and School Initiatives”: Vienna, Austria, 2005; Available online: https://www.ensi.org/global/downloads/Publications/173/ComparativeStudy1.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Rokka, A.X. Geology in Primary Education; Potential and Perspectives. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece 2001, 34, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Peppoloni, S.; Di Capua, G. Geoethics: Ethical, Social, and Cultural Values in Geosciences Research, Practice, and Education. In Geoscience for the Public Good and Global Development: Toward a Sustainable Future; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaro, A.; Fernandes, A.M. Geoparks: From Conception to the Teaching of Geosciences. Terrae Didat. 2018, 14, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Belle, T.J. Formal, Non-formal and Informal Education: A Holistic Perspective on Lifelong Learning. Intern. Rev. Educ. 1982, 28, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Majewska, D. Formal, Non-Formal, and Informal Learning: What Are they, and How Can We Research Them? Cambridge University Press & Assessment Research Report. Available online: https://www.cambridgeassessment.org.uk/Images/665425-formal-non-formal-and-informal-learning-what-are-they-and-how-can-we-research-them-.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Bonnett, M. Environmental Education and the Issue of Nature. J. Curric. Stud. 2007, 39, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzidaki, M. Contemporary Approaches to EE: Place-Based Education and Urban EE. Correlation with John Pantis’ Work in EE. Educ. Sci. 2020, 2019, 126–145. (In Greek) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippaki, A.; Kalaitzidaki, M. Sense of Place in Environmental Education. Environ. Educ. Sust. 2022, 3, 49–64. (In Greek) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, J.; Mulligan, M.; Wheatly, V. Building a Place Responsive Society through Inclusive Local Projects and Networks. Loc. Environ. 2007, 9, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, P.; Stoermer, E. The “Anthropocene”. Glob. Chang. Newsl. 2000, 41, 17–18. Available online: http://www.igbp.net/download/18.316f18321323470177580001401/1376383088452/NL41.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Castree, N. The Anthropocene: A Primer for Geographers. Geography 2015, 100, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalasiewicz, J.; Waters, C.; Summerhayes, C.; Williams, M. The Anthropocene. Geol. Today 2018, 34, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthropocene Working Group. Results of Binding Vote by AWG. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20190612191102/http://quaternary.stratigraphy.org/working-groups/anthropocene/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- United Nations. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Stern, P. Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Iss. 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L.; Cushing, D.F. Education for Strategic Environmental Behavior. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Wölfing, S.; Fuhrer, U. Environmental Attitude and Ecological Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimlich, J.E.; Ardoin, N.M. Understanding Behavior to Understand Behavior Change: A Literature Review. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orion, N. The Future Challenge of Earth Science Education Research. Discip. Interdiscip. Sci. Educ. Res. 2019, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Global Issues, Population. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/population (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Bohle, M.; Marone, E. Why Geo-societal Narratives? In Geo-Societal Narratives, Contextualising Geosciences; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brihla, J. Inventory and Quantitative Assessment of Geosites and Geodiversity Sites: A Review. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauve, L. Environmental Education for Sustainable Development: A Further Appraisal. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 1996, 1, 7–34. Available online: https://typeset.io/journals/canadian-journal-of-environmental-education-drm2w9kb/1996 (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Di Capua, G.; Bobrowsky, P.T.; Kieffer, S.W.; Palinkas, C. Introduction: Geoethics Goes Beyond the Geoscience Profession. In Geological Society Special Publications, 1st ed.; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2021; Volume 508, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author Names | Date | Title | Type of Record | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Magagna, A.; Ferrero, E.; Giardino, M.; Lozar, F.; Perotti, L. [141] | 2013 | A Selection of Geological Tours for Promoting the Italian Geological Heritage in the Secondary Schools. | Article |

| 2. | Almeida, A.; Vasconcelos, C. [7] | 2015 | Geoethics: Master’s Students Knowledge and Perception of its Importance. | Article |

| 3. | De Pascale, F.; D’Amico, S. [142] | 2016 | Historical Memory and Natural Hazards in Neogeographic Mapping Technologies. | Book chapter |

| 4. | Gomes, C.R.; Rocha, A.F.; Ferreira, J.A.; Rola, A. [143] | 2016 | Field Classes for Geosciences Education: Teachers’ Concepts and Practices. | Book chapter |

| 5. | Vasconcelos, C.; Torres, J.; Vasconcelos, L.; Moutinho, S. [144] | 2016 | Sustainable Development and its Connection to Teaching Geoethics. | Article |

| 6. | Vasconcelos, C.; Vasconcelos, M.L.; Torres, J. [145] | 2016 | Education and Geoethics: Three Fictional Life Stories. | Book chapter |

| 7. | De Pascale, F.; Bernardo, M.; Muto, F.; Di Matteo, D.; Dattilo, V. [146] | 2017 | Resilience and Seismic Risk Perception at School: A Geoethical Experiment in Aiello Calabro, Southern Italy. | Article |

| 8. | Bellaubi, F.; Lagunov, A. [147] | 2020 | A Value-Based Approach in Managing the Human-Geosphere Relationship: The Case of Lake Turgoyak (Southern Urals, Russia). | Article |

| 9. | Azevedo, J.M. [148] | 2021 | Geoethics in Higher Education of Hydrogeology. | Book chapter |

| 10. | Cardoso, A.; Orion, N.; Calheiros, C.; Vasconcelos, C. [149] | 2021 | And if the Spring that Provides the Farm with Water Should Run Dry?—A Geoethical Case Applied in Higher Education. | Book chapter |

| 11. | Correia, G.P.; Pereira, H. [150] | 2021 | Teaching Groundwater Resources and Geoethics in Portuguese Secondary Schools. | Book chapter |

| 12. | Georgousis, E.; Savelides, S.; Mosios, S.; Holokolos, M.V.; Drinia, H. [151] | 2021 | The Need for Geoethical Awareness: The Importance of Geoenvironmental Education in Geoheritage Understanding in the Case of Meteora Geomorphes, Greece. | Article |

| 13. | Vasconcelos, C.; Orion, N. [17] | 2021 | Earth Science Education as a Key Component of Education for Sustainability. | Review |

| 14. | Zafeiropoulos, G.; Drinia, H.; Antonarakou, A.; Zouros, N. [52] | 2021 | From Geoheritage to Geoeducation, Geoethics and Geotourism: A Critical Evaluation of the Greek Region. | Review |

| 15. | Georgousis, E.; Savelidi, M.; Savelides, S.; Mosios, S.; Holokolos, M.V.; Drinia, H. [152] | 2022 | How Greek Students Perceive Concepts Related to Geoenvironment: A Semiotics Content Analysis. | Article |

| 16. | Gerbaudo, A.; Lozar, F.; Lasagna, M.; Tonon, M.D.; Egidio, E. [153] | 2022 | Are We Ready for a Sustainable Development? A Survey among Young Geoscientists in Italy. | Article |

| 17. | Handl, S.; Calheiros, C.S.C.; Fiebig, M.; Langergraber, G. [154] | 2022 | Educational Resources for Geoethical Aspects of Water Management. | Article |

| 18. | Paz, M.; Teixeira, I.; Lima, D. [155] | 2022 | Are New Pandemics a Historical Fate of Human Evolution? Education and the Contribution from a Geoethical Perspective. | Article |

| 19. | Procesi, M.; Di Capua, G.; Peppoloni, S.; Corirossi, M.; Valentinelli, A. [156] | 2022 | Science and Citizen Collaboration as Good Example of Geoethics for Recovering a Natural Site in the Urban Area of Rome (Italy). | Article |

| 20. | Tormey, D.; Dongying, W.; Aixia, F. [157] | 2022 | Geoheritage Education as a Gateway to Developing a Conservation Ethic in High School Students from China and the USA. | Article |

| 21. | Mosios, S.; Georgousis, E.; Drinia, H. [158] | 2023 | The Status of Geoethical Thinking in the Educational System of Greece: An Overview. | Review |

| 22. | Nyarko, S.C.; Fore, G.A.; Licht, K. [159] | 2023 | The Role of Ethical Care in the Geosciences: Examining the Perspectives of Geoscience Undergraduates. | Article |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koupatsiaris, A.A.; Drinia, H. Expanding Geoethics: Interrelations with Geoenvironmental Education and Sense of Place. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051819

Koupatsiaris AA, Drinia H. Expanding Geoethics: Interrelations with Geoenvironmental Education and Sense of Place. Sustainability. 2024; 16(5):1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051819

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoupatsiaris, Alexandros Aristotelis, and Hara Drinia. 2024. "Expanding Geoethics: Interrelations with Geoenvironmental Education and Sense of Place" Sustainability 16, no. 5: 1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051819

APA StyleKoupatsiaris, A. A., & Drinia, H. (2024). Expanding Geoethics: Interrelations with Geoenvironmental Education and Sense of Place. Sustainability, 16(5), 1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051819