The Impact of University Challenges on Students’ Attitudes and Career Paths in Industrial Engineering: A Comparative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: To what extent are university challenges and serious games effective in promoting attitudinal development, engagement, and motivation among students?

- RQ2: What specific attitudes are stimulated by these experiential teaching methods, and could participation in such activities serve as a useful tool during the hiring process?

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- Problem Presentation: Organizers introduced one or more company-specific problems to the students. Subsequently, the challenge rules and submission deadlines were defined.

- (2)

- Solution Development: Participating student teams collaborated to develop solutions for the challenges presented by the companies. During this phase, they could seek additional information from company representatives or professors to enhance their proposals.

- (3)

- Evaluation Phase: Following the submission deadline for solutions, finalists were determined based on criteria including solution effectiveness, cost-efficiency, and innovation.

- (4)

- Deeper Problem Understanding: Finalists were often offered the opportunity to visit the company’s facilities related to the problem of interest, gathering additional insights to refine and enhance their solutions. In some cases, Human Resources (HR) conducted interviews to assess students’ suitability for potential employment within the company.

- (5)

- Winner Announcement: The winning student team was announced, and they were rewarded with opportunities such as internships at the company or visits to other facilities.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afzal, F.; Crawford, L. Student’s perception of engagement in online project management education and its impact on performance: The mediating role of self-motivation. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2022, 3, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wong, J.L.N.; Wang, X. How do the leadership strategies of middle leaders affect teachers’ learning in schools? A case study from China. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2022, 48, 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulvik, M.; Eide, H.M.K.; Eide, L.; Helleve, I.; Jensen, V.S.; Ludvigsen, K.; Roness, D.; Torjussen, L.P.S. Teacher educators reflecting on case-based teaching–a collective self-study. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2022, 48, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.K.W. Teaching supply chain management using a modified beer game: An action learning approach. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2015, 18, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Teaching excellence in the context of business and management education: Perspectives from Australian, British and Canadian universities. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiksaitis, C.; Dayton, J.R.; Kabeer, R.; Bunney, G.; Boukhman, M. Teaching Principles of Medical Innovation and Entrepreneurship through Hackathons: Case Study and Qualitative Analysis. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e43916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jääskä, E.; Aaltonen, K. Teachers’ experiences of using game-based learning methods in project management higher education. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2022, 3, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameerbakhsh, O.; Maharaj, S.; Hussain, A.; McAdam, B. A comparison of two methods of using a serious game for teaching marine ecology in a university setting. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2019, 127, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, T.M.; Boyle, E.A.; MacArthur, E.; Hainey, T.; Boyle, J.M. A systematic literature review of empirical evidence on computer games and serious games. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 661–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, D.; Bonnier, K.E.; Hellström, M. How might serious games trigger a transformation in project management education ? Lessons learned from 10 Years of experimentations. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2022, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskä, E.; Lehtinen, J.; Kujala, J.; Kauppila, O. Game-based learning and students’ motivation in project management education. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2022, 3, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iten, N.; Petko, D. Learning with serious games: Is fun playing the game a predictor of learning success? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 47, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berta, R.; Bellotti, F.; van der Spek, E.; Winkler, T. A Tangible Serious Game Approach to Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Education. In Handbook of Digital Games and Entertainment Technologies; Springer: Singapore, 2015; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombelli, A.; Loccisano, S.; Panelli, A.; Pennisi, O.A.M.; Serraino, F. Entrepreneurship Education: The Effects of Challenge-Based Learning on the Entrepreneurial Mindset of University Students. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçayır, G.; Akçayır, M. The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Comput. Educ. 2018, 126, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Membrillo-Hernández, J.; Ramírez-Cadena, M.J.; Martínez-Acosta, M.; Cruz-Gómez, E.; Muñoz-Díaz, E. Challenge based learning: The importance of world-leading companies as training partners. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2019, 13, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A. Measuring thirty facets of the Five Factor Model with a 120-item public domain inventory: Development of the IPIP-NEO-120. J. Res. Personal. 2014, 51, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Mendoza, J.A.; Viscarra Campos, S.; Cotera Rivera, T.; PachecoVelazquez, E.; Andrés Arana Solares, I. Development of Competences in Industrial Engineering Students Inmersed in SME’s through Challenge Based Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Education, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 10–13 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bischof, G.; Bratschitsch, E.; Casey, A.; Lechner, T.; Lengauer, M.; Millward-Sadler, A.; Rubeša, D.; Steinmann, C. The impact of the formula student competition on undergraduate research projects. In Proceedings—Frontiers in Education Conference, Proceedings of the 2009 39th IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, San Antonio, TX, USA, 18–21 October 2009; FIE: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, Z.U.; Gibson, G.E. Serious games for learning prevention through design concepts: An experimental study. Saf. Sci. 2019, 115, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Galli, M.; Mezzogori, D.; Reverberi, D.; Romagnoli, G. On the use of Serious Games in Operations Management: An investigation on connections between students’ game performance and final evaluation. In Proceedings of the XXVII Summer School “Francesco Turco”—“Unconventional Plants”, Sanremo, Italy, 7–9 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Battistoni, E.; Fronzetti Colladon, A. Personality correlates of key roles in informal advice networks. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2014, 34, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Perrigino, M.B. Resilience: A Review Using a Grounded Integrated Occupational Approach. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 729–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantozzi, I.C.; Di Luozzo, S.; Schiraldi, M.M. Soft Skills, Attitudes and Personality Traits in Operations and Supply Chain Management: Systematic review and taxonomy proposal through ProKnow-C methodology. In Proceedings of the XXVII Summer School “Francesco Turco”—Industrial Systems Engineering, Sanremo, Italy, 7–9 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

| N. | Attitudinal Trait | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Achievement/Effort | Establishing ambitious objectives and dedicating substantial effort towards mastering tasks. |

| 2 | Adaptability/Flexibility | Demonstrating a receptive attitude towards change, both positive and negative, and displaying adaptability. |

| 3 | Analytical thinking | Conducting thorough analyses of information and employing logical reasoning to address work-related issues. |

| 4 | Attention to Detail | Exercising diligence and meticulousness in task completion, ensuring comprehensive execution. |

| 5 | Concern for Others | Exhibiting empathy, understanding, and helpfulness towards the needs and emotions of colleagues in the workplace. |

| 6 | Cooperation | Cultivating a friendly and collaborative demeanor with coworkers, fostering a cooperative atmosphere. |

| 7 | Dependability | Assuming responsibility, dependability, and trustworthiness, consistently fulfilling job obligations. |

| 8 | Independence | Cultivating an autonomous approach to tasks, demonstrating initiative even with minimal supervision. |

| 9 | Initiative | Displaying proactive eagerness to embrace challenges and assume additional responsibilities. |

| 10 | Innovation | Utilizing creative and innovative thinking to conceive ideas and develop problem-solving solutions. |

| 11 | Integrity | Upholding honesty and ethical conduct in all job-related activities. |

| 12 | Leadership | Willingness to take the lead, assume charge, express opinions, and provide guidance. |

| 13 | Neuroticism | Displaying a tendency towards worry, self-doubt, and feelings of insecurity, coupled with increased sensitivity to criticism. |

| 14 | Persistence | Exhibiting perseverance and persistence in the face of obstacles. |

| 15 | Self-Control | Exercising emotional control and avoiding aggressive behavior during challenging situations. |

| 16 | Social Orientation | Preferring collaborative work over solitude and forging robust interpersonal connections. |

| 17 | Stress Tolerance | Gracefully accepting criticism and effectively managing high-stress situations. |

| N. | Occupational Trait | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Path satisfaction | Assessment of how much the chosen academic path has positively contributed to the professional journey. |

| 2 | Added value of the challenge | Evaluation of the extent to which participating in university challenges can provide added value during interviews/recruiting processes. |

| 3 | Development soft skills | Assessment of how much the pursued study program has facilitated the development of essential soft skills for future professional endeavors. |

| 4 | Hard skills development | Evaluation of how much the participation in the academic journey has enabled the acquisition of significant hard skills for future professional development. |

| 5 | Evaluation of regret in not participating in the challenge | Perception of the potential regret associated with not having participated in the proposed challenges. |

| 6 | Added value in the assessment phase | Evaluation of how important it was to have participated in a Human Resources interview challenge |

| 7 | Value added in the recruitment | Evaluation of the importance of participating in a challenge in order to be hired by a company. |

| 8 | Career path satisfaction | Degree of satisfaction and fulfillment in individual experiences in chosen career path. |

| 9 | Work–life balance | Ability to balance work responsibilities with personal and family commitments. |

| 10 | Competence evaluation | Process of evaluating an individual’s own competences in relation to job responsibilities. |

| 11 | Role evaluation | Degree of alignment between an individual’s job responsibilities and personal values and goals. |

| Hypotheses | |

|---|---|

| H1. | Adaptability/Flexibility is positively related to the participation in the university challenge. |

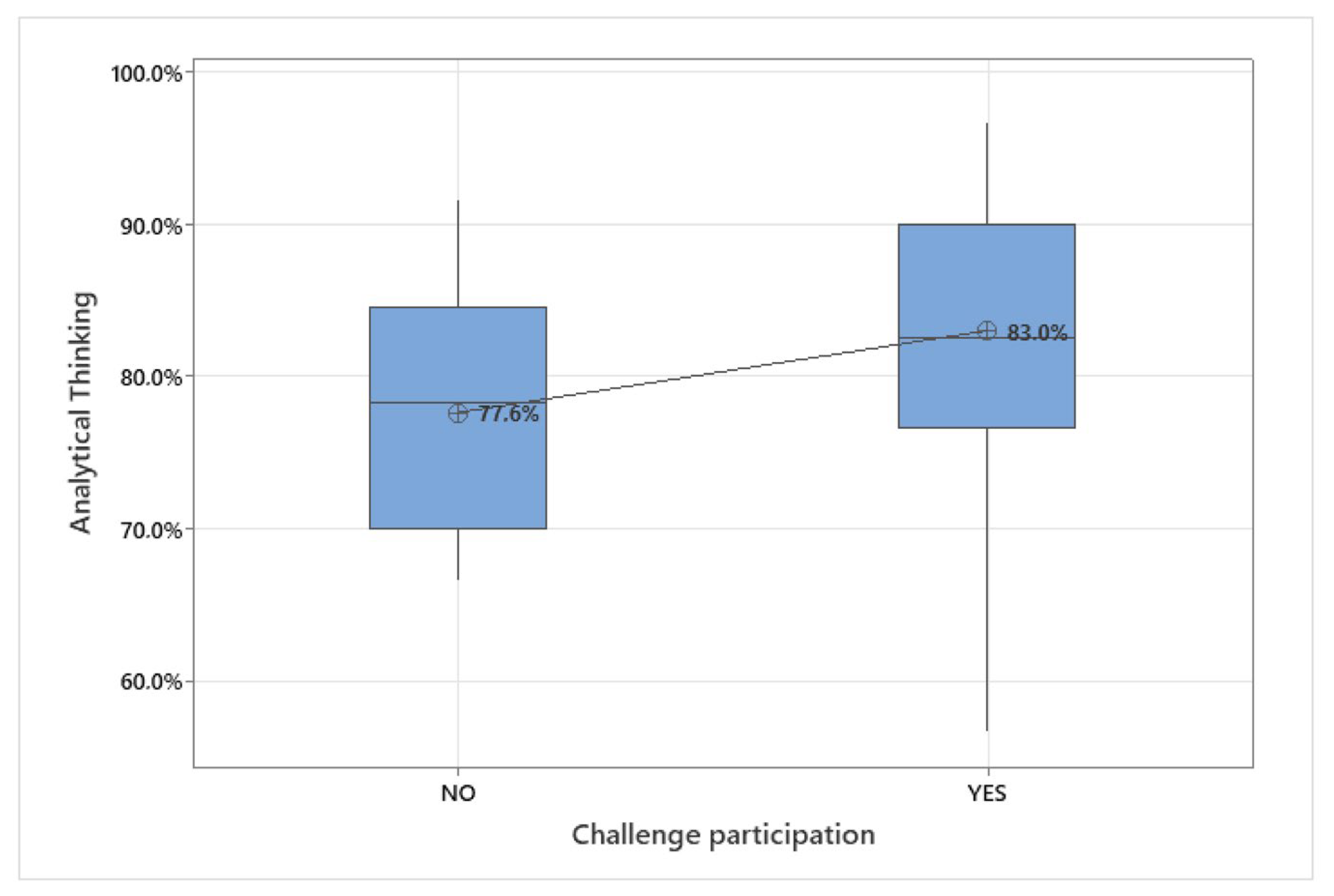

| H2. | Analytical thinking is positively related to the participation in the university challenge. |

| H3. | Cooperation is positively related to the participation in the university challenge. |

| H4. | Innovation is positively related to the participation in the university challenge. |

| H5. | Neuroticism is negatively related to the participation in the university challenge. |

| H6. | Career path satisfaction is positively related to the participation in the university challenge. |

| H7. | Participating in challenges represents added value in recruitment. |

| H8. | Those who do not participate in challenges find them not particularly useful. |

| H9. | Participation in challenges enables the development of soft skills. |

| Path Satisfaction | Value Added Challenge | Soft Skills Development | Hard Skills Development | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value added | −0.318 | |||

| Soft skills development | 0.219 | 0.405 * | ||

| Hard skills development | 0.614 ** | −0.089 | 0.068 | |

| Regret evaluation | −0.349 | 0.769 ** | 0.271 * | −0.015 |

| Path Satisfaction | Added Value in Assessment Phase | Value Added in Recruitment | Soft Skills Development | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Added value in the assessment phase | 0.565 ** | |||

| Value added in recruitment | 0.584 ** | 0.567 ** | ||

| Soft skills development | 0.604 ** | 0.578 ** | 0.442 ** | |

| Hard skills development | 0.417 ** | 0.382 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.377 ** |

| Attitudinal Trait | Correlation |

|---|---|

| Achievement/Effort | 0.016 |

| Adaptability/Flexibility | 0.141 |

| Analytical thinking | 0.264 * |

| Attention to Detail | 0.088 |

| Concern for Others | 0.135 |

| Cooperation | 0.173 |

| Dependability | 0.244 |

| Independence | −0.079 |

| Initiative | 0.169 |

| Innovation | 0.326 ** |

| Integrity | 0.069 |

| Leadership | 0.197 |

| Neuroticism | −0.064 |

| Persistence | 0.023 |

| Self-Control | 0.106 |

| Social Orientation | 0.097 |

| Stress Tolerance | 0.216 |

| Challenge Particip. | Career Path Satis. | Work–Life Balance | Competence Evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career path satisfaction | −0.072 | |||

| Work–life balance | 0.077 | 0.261 * | ||

| Competence evaluation | −0.001 | 0.379 ** | 0.171 | |

| Role evaluation | −0.030 | 0.500 ** | 0.267 * | 0.638 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fantozzi, I.C.; Di Luozzo, S.; Schiraldi, M.M. The Impact of University Challenges on Students’ Attitudes and Career Paths in Industrial Engineering: A Comparative Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041600

Fantozzi IC, Di Luozzo S, Schiraldi MM. The Impact of University Challenges on Students’ Attitudes and Career Paths in Industrial Engineering: A Comparative Study. Sustainability. 2024; 16(4):1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041600

Chicago/Turabian StyleFantozzi, Italo Cesidio, Sebastiano Di Luozzo, and Massimiliano Maria Schiraldi. 2024. "The Impact of University Challenges on Students’ Attitudes and Career Paths in Industrial Engineering: A Comparative Study" Sustainability 16, no. 4: 1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041600

APA StyleFantozzi, I. C., Di Luozzo, S., & Schiraldi, M. M. (2024). The Impact of University Challenges on Students’ Attitudes and Career Paths in Industrial Engineering: A Comparative Study. Sustainability, 16(4), 1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041600