Abstract

This paper examines the challenges surrounding sustainable human resources management (HRM), particularly in the context of budget constraints that often lead to the reduction of employee development investments. Our research focuses on developing a comprehensive model that integrates financial management tools into HRM strategies, ensuring the prioritization of sustainable practices. Through a systematic analysis of existing knowledge, we propose a solution-oriented approach that supports the financial substantiation of investments in employee development. This study addresses key research questions, emphasizing the adaptation of corporate finance tools to meet HR’s specific requirements. Our research not only identifies challenges but, more importantly, offers solutions by presenting a model that empowers organizations to align financial goals with HR development objectives. The results of our research aim to formulate a pragmatic and inventive model, offering a systematic framework for assessing the financial feasibility of initiatives in human resources development. Our model offers a practical framework for assessing the financial feasibility of HR development initiatives, facilitating informed decision-making and the promotion of sustainable HRM practices.

1. Introduction

This paper explores the complex field of sustainable human resources management (HRM) with a specific focus on integrating financial management tools into HRM strategies. This study proposes a novel and practical framework that systematically prioritizes sustainable practices within HRM. Our analysis of existing knowledge leads to a solution-oriented approach that substantiates the financial justification for robust investments in employee development initiatives. This research addresses essential questions surrounding the adaptation of corporate finance tools to meet the evolving requirements of HR. The scope extends to the systematic examination of the financial feasibility of HR development initiatives, with the proposed model offering practical insights for informed decision-making within organizations. Furthermore, this paper aims to highlight the individuality of its findings due to the lack of comparable publications on the utilization of financial tools in HRM.

The primary objective of this research is to develop a theoretical framework for integrating financial analysis into human resources development (HRD) from a sustainable HRM perspective, with a focus on proposing relevant financial tools. In this paper, we first conducted a review of the existing literature related to sustainable HRM, HRD, financial analysis, and their intersections. We opted for presenting the literature review chronologically to illustrate the evolution of the research in this field of study. This paper organizes the existing literature based on the sequence of when the studies were conducted or when key concepts emerged to provide a clear picture of how the field of sustainable HRM has evolved, starting with earlier works and progressing to more recent research. The second part of the paper elaborates on some financial tools that could be used to substantiate the investments in human resources development (HRD) as an important part of sustainable HRM.

The novelty of our paper proposing financial tools to substantiate investments in human resources development (HRD) lies in its ability to bridge the gap between theoretical concepts and practical application. The paper brings together two critical areas of organizational management: HRD and financial analysis. It provides a conceptual framework for integrating financial analysis into HRD, which is a novel approach and helps organizations align their human capital investments with financial goals. The paper also offers a holistic view of HRM by considering the financial aspect. This perspective allows organizations to see HRD as an investment with potential returns rather than just a cost, which is a paradigm shift from traditional HR practices.

Sustainable HRM focuses on fostering socially and environmentally responsible HR practices within organizations. Sustainable HRM is concerned not only with social and environmental sustainability but also with financial sustainability. When integrated with HRD, it promotes the development of employees’ skills, knowledge, and abilities in ways that align with sustainability goals. This alignment creates a workforce better equipped to drive sustainability initiatives. Financial analysis, on the other hand, provides a quantitative lens through which organizations can evaluate the impact of HRD efforts on their financial performance. By employing financial tools, organizations can assess the economic benefits and costs associated with HRD programs, thereby substantiating the value of sustainable HRM practices. These intersections enable organizations to not only enhance their sustainability efforts but also justify their investments in human development by demonstrating how such investments contribute to long-term financial viability and competitiveness. As such, the convergence of sustainable HRM, HRD, and financial analysis represents a strategic and holistic approach to achieving both sustainability and financial objectives within organizations.

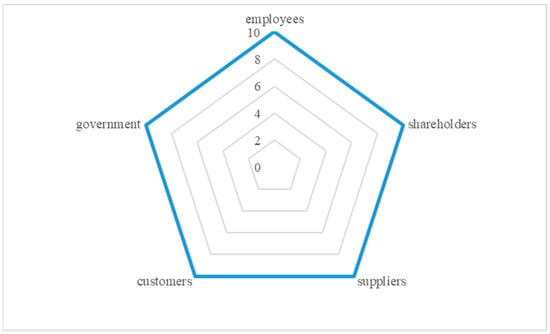

Managers have a key role in maintaining the balance between various aspects of the activity of the company. To maintain the company on a sustainable growing trend, it is necessary to satisfy the needs of major stakeholders. While in this paper we will refer to only five categories (listed here in random order), shareholders, employees, suppliers, government, and customers, there are other important stakeholders which should not be overlooked when developing the overall business strategy: environment, future generations, and so on [1].

A balance must be maintained between all these categories of stakeholders, and because of the divergence in their interests, the endeavor is even more difficult. Figure 1 illustrates what this balance could look like. The level of satisfaction was arbitrarily considered to be the same size for each stakeholder, and this explains the relative perfection of the image. In practice, reality does not correspond to the same pentagon form; however, the wider and more perfect the image, the better the company stands from the point of view of its sustainable growing trend. Of course, the importance of these stakeholders can fluctuate depending on the circumstances, but the idea is for a balance to be pursued and maintained.

Figure 1.

The stakeholders’ balance pentagon. Source: own elaboration.

2. Theoretical Foundation

When considering stakeholders and their levels of satisfaction, it is important to be aware of the diverse nature and perceptions of their satisfaction. Simplistically, shareholders are typically pleased by higher dividends, employees strive for larger paychecks, governments expect companies to pay taxes, suppliers are satisfied when their debts are settled upon maturity, and customers are pleased with a good price–quality ratio.

All these stakeholders’ requirements are considered under normal circumstances, but there are many other aspects that need to be addressed. In recent years, customers have diversified their preferences and now consider factors beyond just the price–quality ratio when measuring their satisfaction. Many customers are seeking products that are produced sustainably, with greater respect for the environment and socially responsible actions. Shareholders may also have other dimensions of their overall interests. They may focus on maximizing the value of the company and analyzing differences in stock prices at various times. Additionally, they may be more inclined towards ESG-based (Environmental, Social, and Governance) investment strategies rather than strictly focusing on maximizing shareholder value (MSV).

Employees are discussed last among all stakeholders in this paper because it specifically elaborates on this particular category of stakeholders. Additionally, employees expect more than just a monthly paycheck from their employers. They value good working conditions, which encompass both the physical space where employees carry out their regular activities and the work environment, including relationships with colleagues, career-related opportunities, and more. When people apply for a job, they typically assess the requirements presented in the job description. In doing so, they may identify certain incentives or statements that can influence their decision-making process. Cultural aspects are not negligible in terms of job perception [2,3]. Kamoche identifies some differences in the way employees could relate to their job depending on the cultural factors: “corporate welfarism in Cadbury Schweppes, the ‘caring company’ reputation of Johnson&Johnson, or the sense of belonging and job security associated with lifetime employment in some Japanese firms” [4].

On the other hand, a sustainable approach to doing business is preferred, and that includes identifying sustainable ways of tackling the needs of stakeholders. Employees are one of the major stakeholders usually considered. Of all the characteristics of sustainable HRM, we will mainly focus on care of employees and employee development.

The main purpose of this paper is to demonstrate that the need for HR development, as a sustainable approach in HRM, can be analyzed and supported using financial management tools. Our intention is to advocate for the identification of sustainable methods to support employees in their skill development. This research was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, a bibliometric review was performed to generate a comprehensive overview of existing knowledge in the field of sustainable HRM, which is presented in the theoretical background section. In the second stage, we present several financial management tools that can be utilized to support HR development initiatives.

To establish the coverage for this topic, an analysis on relevant articles in the field of sustainable HRM was conducted. The Web of Science Core collection was used because it offers a wide collection of scientific resources and the interest in our topic can be dynamically analyzed. When searching WoS for articles on “sustainable human resources management”, more than 8700 articles were found for the 1992–2022 time frame. However, the interest in this topic has grown steadily since 2014. One interesting aspect in many of these articles is the scaling-down of ESG criteria—Environment, Social, Governance—to a size which seems fitting for a company: the environmental, social, and economic vision of the company’s performance. This paper categorizes the available literature by the chronological order of study conduct and the emergence of pivotal concepts. This approach aims to offer a comprehensive overview of the evolution of the sustainable human resource management (HRM) field, commencing with earlier works and advancing to contemporary research.

This image of a company’s performance was best captured by Elkington’s triple bottom line concept [5]. This means that the company’s activity should not only be seen in terms of revenues-minus-costs as a single bottom line, but it should be expanded to a more developed approach with a broad emphasis on the social and environmental dimensions of the full process. First, Elkington revealed a negative triad, inspired by thinkers such as Commoner, Goldsmith, and Ehrlich, whose interest was circumscribed to mostly environmental issues. The negative triad and its poisonous results that Elkington pointed out were “the combined trajectories of population growth, industrial pollution, and ecosystem destruction [which] threatened to undermine the future, whether capitalist or communist” [5]. This assertion was made in the author’s early years (late 1960s), when communist regimes were powerful contenders to capitalism, and, while right-wing thinkers labelled Commoner, Goldsmith, and Ehrlich as “watermelon jibe—green on the outside, red on the inside”, Elkington considers the thinkers were from a “much wider political spectrum”.

One of the first mentions of HRM in terms of sustainability was that of Brotherton, Woolfenden, and Himmetoglu (1994), who were preoccupied with studies in the field of tourism. The authors identified that one of the problems in Turkish tourism was the quality of human resources in the hospitality industry. They were worried about the sustainability of Turkish tourism growth in the following period (after 1994), despite the “spectacular increase in the size of Turkish tourism” [6]. However, the authors focused only on the “shortage of skilled staff”, the workplace conditions not being considered.

Kamoche [4] argues that the interaction between organizational routines, good practices, and human resources (HR) policies is generating HR competencies with certain strategic value going beyond the existing (at that moment) conditions. Barney and Wright (1998) assert that human resources should be regarded as a significant stakeholder and potential source of sustainable competitive advantage within an organization. To analyze the behavior of the HR function across different companies, the authors introduce the VRIO framework, which stands for “value, rareness, imitability, and organization.” According to Barney and Wright, although managers may acknowledge employees as the most important asset in theory, their decisions and actions often do not align with this perspective. They also emphasize the relative ease of imitating many processes within a company. To address this challenge, the authors suggest that managers should focus their efforts on developing and nurturing unique characteristics of the firm’s human resources that are not easily replicable by competitors [7].

The proposed solution involves delving into the distinctive qualities of each company to identify elements that can provide strategic advantages that are difficult for competitors to imitate. By understanding and leveraging these unique attributes, organizations can differentiate themselves and create sustainable competitive advantages in the marketplace. This approach moves beyond simply acknowledging the value of human resources and emphasizes the importance of actively developing and cultivating specific traits that set the organization apart from its rivals. An interesting statement was made by Lee and Miller (1999)—“People matter”. Even if the authors studied mostly Korean companies, the statement and the proposed commitment to employees could be a mantra for every company, adapted, of course, to its cultural background [8]. Lee and Miller brought into the discussion the association between an organization’s commitment to its employees (OCE) and the return on assets (ROA) indicator (otherwise a powerful and meaningful indicator). Usually, human resources as an asset of a company should respond as positively as possible to an analysis of their financial performance, but the authors have found that the previously mentioned association between the two notions is rather weak in some cases. They also found that the interaction of OCE with “the dedicated pursuit of Porter’s (1980) strategies for achieving competitive advantage” is influencing ROA “strongly and positively” [8]. An enhanced level of OCE in a company leads to more effectively executed strategies, with one condition—that these strategies must be “dedicated, […] intensive and thorough, positioning strategies” [8].

Daily and Huang (2001) discuss the relationship between two different major stakeholders—the environment and human resources—as a means to gain a competitive advantage over their competitors. According to the authors, implementing Environmental Management Systems (EMS) can be a lengthy and costly process. Daily and Huang identify numerous HRM-related instruments that could serve as key elements capable of positively influencing the implementation of an EMS. These instruments include “top management support, environmental training, employee empowerment, teamwork, and reward systems” [9]. By arguing that balancing these instruments with the cost and time duration of, for example, ISO 14001 guidelines, the authors demonstrate that developing environmentally oriented human resources could be a beneficial approach.

In another article focused on gaining competitive advantage by shaping human resources, Aragón-Sánchez et al. (2003) underline the importance of training and underline the difficulties in quantifying the outcomes of the training process. Their study found evidence of “significant relationships between training and performance” [10].

Jabbour and Santos identify the link between human resources and environmental management in a company [11] and, further, places HRM in a central role in pursuing the sustainable character of an organization [12]. In short, the two authors consider the environmental and human resources aspects as significantly related to the sustainability of companies.

In another article, Kramar (2013) discusses whether sustainable HRM will be the next HR approach. The article positions sustainable HRM as part of a broader strategic HRM framework, which encompasses the integration of sustainability and HRM. It also identifies various meanings associated with the relationship between the two within the broader strategic approach. The article recognizes organizational outcomes that extend beyond financial measures, presenting a more comprehensive perspective compared to MSV (maximizing shareholder value)-based strategies. Additionally, it introduces the moral aspect inherent in the entire HRM process [13].

Figurska and Sokół, in their research on Polish organizations, highlight the strategic nature of knowledge resources and their management. They propose benchmarking as a method to enhance the effectiveness and optimization of knowledge management processes [14].

Another area of interest for researchers is the relationship between managers (i.e., employers) and employees, examined through the lens of “workplace mutuality” [15]. In their article, Dobbins and Dundon promote a theory consisting of three elements—“system, society, and dominance”—and utilize this framework to examine the notion of “management-labor workplace partnerships” as a chimera. Through case study research conducted in organizations in Ireland, the authors discuss the dynamics between management and labor in the context of “neoliberal work regimes”.

In a 2015 article, Doering et al. made a comparison between various types of capitalism according to their sustainable character. They were trying to answer the question of whether there are any sustainable types of capitalism by studying a large steel company, which operates both in Germany and in Brazil: the authors studied a company that was facing relatively new constraints regarding the sustainable development requirements in “Germany—as an example of a coordinated market economy (CME)—as well as in Brazil—this time an example of a hierarchical market economy (HME)” [16]. Their article demonstrates that different institutional contexts could generate different operational strategies regarding the green transition of the steel industry.

In an article discussing the efforts made by authorities, Rodriguez et al. (2017) consider that changes that happened in the work dynamic require more procedures, policies, and other actions from responsible institutions. The authors revealed an interesting facet of regulations and argue that “regulation sits at the center of competing economic and social demands, which are seen as both complementary and irreconcilable, and its complexity needs to be theorized and empirically mapped”, which cannot be disputed [17].

Stankevičiūtė and Stankevičiūtė (2017) discuss smart power, a term borrowed from political science, as a useful tool in pursuing the sustainable character of HRM. In their article, the authors describe smart power as a combined tool (using both soft and hard power) to manage “work-life balance, management of employees’ relations, and stress management”. The premises are an aging society and health issues among employees. The authors also consider sustainable HRM to be an appropriate tool for “enhancing organization’s profit, minimizing “ecological footprint” and reducing the harm on employees” [18].

In their research, Wepfer et al. (2017) examined the increasingly blurred boundaries between work and personal life among approximately 2000 employees. They discovered that many individuals struggle to establish a well-defined balance between these two domains and often find them intertwined [19]. The proliferation of new technologies, which enable constant connectivity and communication, has played a significant role in facilitating this merging of work and personal life. The study highlighted that employees, driven by the ease of access to work-related communication through technology, tend to work longer hours and with greater intensity. They frequently engage with work-related tasks even during their designated time off. This constant engagement and inability to disconnect from work activities can impede the availability of sufficient time for recovery activities, ultimately leading to adverse effects on their overall well-being. The findings shed light on the negative implications of the blurring boundaries between work and personal life. This study emphasizes the need for individuals and organizations to be aware of these challenges and strive to establish strategies and practices that promote a healthier work–life balance. This research underscores the importance of managing technology use and implementing policies that allow employees to have dedicated time for rest and recovery, ultimately supporting their well-being and overall quality of life.

In a research study conducted by Baum in 2018, the author proposes a set of concerted actions to be undertaken by local and national authorities to establish a framework that fosters developments in the quantity and quality of the tourism-involved workforce [20]. The research emphasizes the significance of the tourism industry and the role it plays in local and national economies. To support the growth and sustainability of this sector, Baum suggests that policymakers and authorities need to take proactive measures. Baum argues that local and national authorities can create an enabling environment that supports the development of a skilled and sustainable tourism workforce. This, in turn, contributes to the growth and competitiveness of the tourism industry and ensures its long-term success.

In a study conducted by Blašková et al. in 2018, the researchers explored the sustainable nature of motivation and its impact on key processes related to the development of human potential. The findings of their research revealed a strong correlation between the level of motivation and the quality of key processes such as leadership, appraisal, communication, and the creation of an atmosphere of trust [21]. The study highlights the importance of motivation in fostering an environment that supports the development of human potential within an organization. The researchers suggest that when employees are highly motivated, it positively influences the effectiveness of key processes that are essential for their development and growth.

In a study conducted by Stankevičiūtė and Stankevičiūtė in 2018, the authors address the issue of a lack of clarity in the attributes of sustainable human resource management (HRM). The authors argue that the traditional view of employees as resources to be consumed rather than developed is no longer appropriate. They propose a set of characteristics that define sustainable HRM, emphasizing the need for a shift towards a more holistic and sustainable approach: “long-term orientation, care of employees, care of environment, profitability, employee participation and social dialogue, employee development, external partnership, flexibility, compliance beyond labour regulations, employee cooperation, fairness, and equality” [22]. By delineating these characteristics, Stankevičiūtė and Stankevičiūtė offer a broader understanding of sustainable HRM that goes beyond traditional HR practices. They emphasize the need for organizations to adopt a comprehensive and integrated approach to HRM that aligns with the principles of sustainability, taking into account the well-being of employees, the environment, and the long-term success of the organization.

The research conducted by Zaid, Jaaron, and Talib Bon in 2018 examines the relationship between sustainable human resource management (Sustainable HRM) and sustainable supply chain management. They find a linkage between these two concepts and suggest that they share a connection that has a direct impact on the triple bottom line (TBL), which encompasses the environmental and social performance of companies. The study highlights that sustainable HRM practices, which focus on integrating sustainability principles into human resource management, can contribute to the sustainability of supply chain management. Sustainable supply chain management aims to incorporate environmental and social considerations into the management of supply chains to minimize negative impacts and create sustainable value [23].

The research conducted by Gutiérrez Crocco and Martin in 2019 focuses on the role of the union–management relationship and the process of resolving work conflicts in a sustainable manner. The authors explore how collaboration and effective communication between labor unions and management can contribute to sustainable outcomes within organizations. By fostering a cooperative approach to addressing work conflicts and finding mutually beneficial solutions, organizations can promote sustainability in their operations [24]. In a similar vein, Chams and García-Blandón (2019) highlight the growing awareness among companies regarding the importance of social, ethical, and ecological objectives. They argue that many organizations are now actively pursuing the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set forth by the United Nations. The authors suggest that implementing sustainable HRM practices can enhance the capability of human resources to understand and align their thinking with these SDGs. By incorporating sustainability principles into HRM practices, organizations can facilitate the achievement of SDGs more effectively [25].

Hitka et al. (2019) study the quality of employees and their level of engagement. The authors highlight the importance of improvement in the leaders’ ability to be innovative and to “manage, motivate, and encourage other employees”, leading in this way to comparative advantages for companies. The outcomes of their research showed a strong and direct relationship between career aspirations and the level of education [26].

Richards (2020) considers that sustainable HRM should put employees at the center of the whole process. The author thinks that this approach goes “far beyond” mainstream HRM [27], while Van Buren III pleads for employees’ inclusion to establish a “pluralist perspective” and to pursue “social sustainability outside of the employment context” [28]. Along with employees, Nilsson and Nilsson (2021) introduce “first-line managers, trade union representatives, and HR practitioners” for an “extended work life and employability” [29]. Many people want to work even when in their older age, and it could be feasible to find a framework to better accommodate them. Vraňaková et al. (2021) studied the objective temporal coexistence of different generational groups at the level of almost every company. The authors consider that sustainable HRM should consider “the importance of age management pillars” [30]. The same age-related problem is revealed by Meidutė-Kavaliauskienė et al., who consider the aging population to be one of the major impediments in the way of the SDGs’ implementation [31]. The relevance of the aging populations is related to certain goals among the 17 SDGs: inequality, poverty, health, and well-being. According to the authors, inequality must be seen both as between countries and within them.

Medina-Garrido et al. (2019) studied the balance between work and personal life in a sample of Spanish banks [32]. Strenitzerová and Achimský (2019), on the other hand, are interested in employee satisfaction and loyalty in the Slovak postal sector [33]. Di Fabio and Saklofske (2019) discuss personality traits and emotional intelligence in relational management towards sustainable development [34]. Chillakuri and Vanka (2020) reveal the positive effect of perceived organizational support on employees’ health status and well-being within high-performance work systems [35]. In the same field, Durand et al. bring to light a sustainable return to work in the case of aging employees who are experiencing a work disability [36], while Radvila and Šilingienė (2020) are preoccupied by the remuneration system in a sustainable HRM context in a study based on a sample of Lithuanian enterprises [37].

In addition, two papers that provide examples of systematic literature reviews for sustainable HRM were identified. Macke and Genari (2018) analyzed “the state-of-the-art” of sustainable HRM using the Scopus database [38]. The authors grouped the 115 scientific papers from the period 2001–2018 into four categories. The first category is dedicated to sustainable leadership, which reveals the existing power at the individual and group level embedded in its principles, processes, practices, and organizational values. The second category demonstrates the relationship that exists among human resource management, environmental sustainability, and organizational performance. The third category includes tensions and paradoxes that exist between sustainability and HRM. These tensions are determined by the dichotomy present in the sustainability versus profitability discourse. The fourth category includes articles on the connection between sustainable HRM and the stakeholders of the company, especially those involved in social aspects. The second paper, by Kainzbauer and Rungruang (2019), studied scientific papers over a larger time period, from 1982 to 2019. In their bibliometric review, the authors mapped all articles, key articles, and journals and identified four Schools of Thought in this field: three focused on sustainability and one focused on general and mainstream HRM [39].

One of the most influential scholars in the field of sustainable HRM is Susan E. Jackson, with numerous citations to her work. As of 2023, according to Google Scholar, she has been cited alone and in co-authorship more than 122,000 times. Jackson’s research covers various aspects of sustainable HRM, including burnout-related issues [40,41,42] and team and organizational diversity [43,44,45]. Jackson has also expressed concern about the “greening of strategic HRM scholarship” [46]. Furthermore, Jackson and her colleagues have addressed international HRM from the perspective of global talent management in their article [47]. In her comprehensive book titled “Managing Human Resources,” Jackson discusses various HRM issues, with a significant emphasis on sustainable HRM [46].

The link between sustainability and HRM has also been a topic of investigation, with research exploring the role of HRM in fostering economically, socially, and ecologically sustainable organizations. Ehnert et al. (2014) delve into this subject, highlighting the importance of HRM in pursuing sustainability objectives [48]. This aligns with the concept of the triple bottom line, which encompasses environmental, social, and economic performance. Furthermore, the relationship between social sustainability and the quality of working life has also been examined. This research delves into how HRM practices can contribute to social sustainability by promoting a positive work environment, employee well-being, and work–life balance. The aim is to create organizations that not only achieve economic success but also prioritize the welfare of employees and society.

3. Research Design

The research design for this paper is centered around the exploration and analysis of theoretical concepts and ideas related to the concept of sustainable HRM. This study aims to develop a comprehensive theoretical framework that elucidates the intricate interplay between financial tools and sustainable HRM. While empirical data collection is not the primary focus, the research design employs a deductive approach, drawing on the existing literature and conceptual analysis to build and test theoretical propositions.

As stated, the aim of this paper is to demonstrate that the need for HR development can be analyzed and supported using financial management tools. Our research objective is to design a model that can be utilized for the financial justification of HR development initiatives. The proposed model consists of two parts: one based on a feed-before approach, and the other relying on traditional feedback analysis. It considers investment in HR development to be a project, similar to other economic projects within the company. The proposed model adapts specific corporate finance tools to the unique characteristics of HR development, which is a key component of sustainable HRM.

Our intention is to advocate for the identification of sustainable methods to support employees in their skills development. The research was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, a bibliometric review was performed to generate a comprehensive overview of existing knowledge in the field of sustainable human resource management (SHRM). In the second stage, we presented several financial management tools that can be utilized to support HR development initiatives. Our paper revolves around two primary research questions:

RQ1: Is Sustainable HRM sufficiently substantiated to be considered a stand-alone/legitimate approach?

RQ2: How can HR development, as a main characteristic of sustainable HRM, be transposed into long-term strategy?

The research follows a deductive approach, where existing theories and empirical findings in the fields of sustainable HRM are synthesized and applied to the context of human resources development. The deductive approach involves the formulation of theoretical propositions derived from established theories and concepts. Our research relies primarily on scholarly articles, books, and reports from disciplines such as finance and management.

To address the research questions, the following steps were undertaken:

- Literature Review and Content Analysis: A comprehensive review of the literature in the field of sustainable HRM was conducted, utilizing the Web of Science Core Collection and selecting relevant articles for analysis. This review aimed to gather existing knowledge and theories related to sustainable HRM.

- Critical Analysis of Existing Approaches: The selected literature was critically analyzed to evaluate the different approaches and theoretical perspectives within sustainable HRM. This analysis aimed to assess the level of substantiation and legitimacy of sustainable HRM as a stand-alone approach.

- Analysis of the Connection between HR Development and Sustainable HRM: The relationship between HR development and sustainable HRM was explored and examined. This analysis sought to understand the integration of HR development as a central element within long-term sustainable HRM strategies.

- Designing a Model for Substantiating HR Development Investments: Based on the findings from the literature review and analysis, a model was developed to assist in substantiating investments in HR development as a sustainable line of action in HRM. This model aimed to provide a framework for evaluating the financial aspects of HR development initiatives.

Assumptions and Limitations

It is assumed that the existing literature adequately represents the diverse approaches on sustainable HRM and human resources development. However, limitations include the potential simplification of complex HRD issues due to the theoretical nature of the study and the absence of direct empirical data collection. It should be noted that the articles selected for the literature review and content analysis were chosen for illustrative purposes. The main scientific database used was the Web of Science Core Collection. The primary focus was not only on analyzing the existing literature but also critically evaluating the various approaches from different theoretical perspectives.

4. Results and Discussion

The alignment of sustainable HRM with broader sustainability goals reflects a paradigm shift in organizational values. Companies increasingly recognize that sustainable practices in human resource management not only contribute to environmental and social responsibility but also enhance overall organizational performance. The integration of financial tools into HRM strategies, as emphasized in sustainable HRM, solidifies its legitimacy. The acknowledgment that investing in human capital development is not only a socially responsible act but also a financially sound decision demonstrates the approach’s practical viability.

To answer RQ1: Is sustainable HRM sufficiently substantiated to be considered a stand-alone/legitimate approach? a literature review was conducted. Based on the critical analysis of the scientific literature in the field of sustainable HRM, conducted in Section 2 of the paper, several conclusions can be drawn:

- Sustainable HRM lacks a solid theoretical background and a consolidated approach. Similar to stakeholder theory, it lacks a clear normative framework, and often relies on good practices rather than well-defined regulations or instruments to guide decision-making.

- HR managers often do not view employees as developable assets, and instead focus on utilizing them without making significant efforts to support their skill development or tap into their true potential.

- Sustainable HRM encompasses a broader vision than mainstream HRM, considering outcomes beyond just financial results. The adoption of concepts like the triple bottom line (economic, social, and environmental performance) can significantly improve business practices.

- Placing employees at the center of sustainable HRM and recognizing them as major stakeholders can increase awareness and prioritize their well-being and development.

- HR practitioners should strive to create a unique HR system that focuses on attracting and retaining talent, while minimizing the possibility of replication by competitors. Developing a unique system that aligns with sustainability principles can provide a solid competitive advantage.

Overall, these conclusions highlight the need for further development and refinement of sustainable HRM, as well as the importance of integrating sustainability principles into HR practices.

4.1. Financial Support of Sustainable Human Resources Management

When it comes to financially supporting the decision-making process in a company, particularly in the field of HR, an interesting opinion arises from Wright, Dunford, and Snell. They assert that during prosperous times, companies readily justify expenditures on training, staffing, rewards, and employee involvement systems. However, when faced with financial difficulties, these HR systems become vulnerable to early cutbacks [49]. This perspective is influenced by the resource-based view (RBV) of the company, which suggests that the key instruments for achieving a competitive advantage should be sought within the company, rather than externally. This RBV strategy can be applied to various types of resources, including HR. Thus, HR can be considered as part of a use–develop–repeat process, leading to a potential competitive advantage. Furthermore, the authors highlight that HR is involved in both strategy design and implementation, emphasizing the need for the development of HRM. This underscores the importance of HR managers/practitioners taking a broader interest in creating HR strategies characterized by distinctiveness. This perspective emphasizes the significance of providing financial support for the decision-making process, particularly in HR. It suggests that HR should be recognized as an internal resource that contributes to competitive advantage. HR managers/practitioners should actively engage in developing unique HR strategies that align with the organization’s overall strategy.

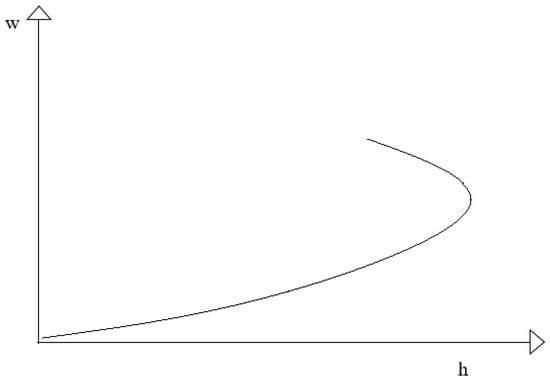

In terms of utilizing the human asset, it is important to consider the atypical nature of labor supply. Specifically, attention should be given to the relationship between wage levels and the number of hours employees are willing to work (see Figure 2). It has been observed that as wages increase, there reaches a point where the labor supply curve starts to bend back, resulting in a decrease in the number of hours employees are willing to work. This phenomenon suggests that there is a threshold beyond which higher wages do not necessarily lead to increased labor supply. As wages continue to rise, individuals may choose to work fewer hours due to factors such as increased leisure time, a desire for work–life balance, or alternative opportunities outside of work. This implies that the relationship between wages and labor supply is not linear, but rather exhibits diminishing returns. Understanding this non-linear relationship is crucial for employers and policymakers when making decisions related to wage levels and workforce planning. By recognizing the atypical nature of labor supply and considering the complexities of employee preferences, organizations can make more informed decisions regarding wage structures and work arrangements that effectively meet the needs and motivations of their workforce.

Figure 2.

Labor supply, where w stands for wage and h for number of working hours. Source: own elaboration.

The substitution effect between money and leisure time is indeed reversing its direction, with leisure time becoming more valuable than monetary compensation. As a result, employees are inclined to reduce the number of hours they are willing to work. This shift in preference indicates that the allure of extrinsic financial motivation is diminishing, prompting HR managers and practitioners to focus more on intrinsic motivation. While extrinsic motivation may be more straightforward to address and implement in HR strategies, it is essential to recognize that easier does not necessarily equate to better. Numerous studies and arguments highlight the effects of extrinsic motivation on performance and creativity, as well as the existing gap between theory and practice in this area. Scientific evidence supports the notion that relying solely on extrinsic motivators may not lead to optimal outcomes. Studies by Zhang and Liu [50], Locke and Schattke [51], and Auger and Woodman [52] provide insights into the complex relationship between extrinsic motivation and employee performance and creativity. These works shed light on the limitations of extrinsic motivators and emphasize the importance of intrinsic factors, such as autonomy, mastery, and purpose, in driving employee engagement and productivity.

When it comes to leveraging intrinsic work motivation, HR specialists have various means at their disposal to harness the benefits associated with this type of motivation. One crucial aspect to consider is the impact of workplace conditions on employees’ intrinsic motivation. Research by Matei and Abrudan (2016) highlights the significance of workplace conditions in influencing employee motivation. The study emphasizes that different employees place importance on various aspects of the work environment. Factors such as physical comfort, safety, supportive relationships, opportunities for growth and development, and meaningful work contribute to creating an environment that nurtures intrinsic motivation [53].

With both extrinsic and intrinsic implications, workplace conditions encompass at least two dimensions: physical conditions and psychologically subjective attributes. In the context of sustainable HRM, these attributes hold significant importance, and HR managers would demonstrate astuteness by taking actions to address them. While physical conditions are relatively straightforward, the psychologically subjective attributes of the workplace raise several issues that need to be considered. However, even if the physical conditions of the workplace seem to be a sine qua non, their meaning is not negligible. As Maslow (1943) pointed out, the situation in which individuals operate must be taken into account, but it alone cannot fully explain behavior [54]. Translated into the context of this paper, this implies that a specific workplace, devoid of people, has no impact on the behavior of individuals who work there. People’s behavior is a motivational response to situational factors and motivation can serve as a nexus between the way in which the workplace presents itself and individual behavior. Humans can experience satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the physical conditions of their workplace, and their subsequent behavior can reflect their level of motivation in carrying out their activities. Situated within the intrinsic dimension of motivation, the workplace and its physical conditions can serve as a valuable tool for managers to enhance employee performance. However, a challenge arises from the fact that motivation is deeply personal and subjective, which can influence the decision-making process.

Considering the importance of workplace conditions, we paid attention to an article published by Astvik, Welander, and Larsson (2019), which focuses on work conditions in social services in Sweden and other European countries and how these conditions impact employees’ willingness to stay in their organizations. The research was conducted using a quantitative analysis based on the results of two online questionnaires. The findings indicate that certain work conditions have an influence on employees’ willingness to remain in their current organization. These conditions include low levels of conflicting demands and quantitative demands, high levels of openness and human resource orientation within the organization, and a high perception of service quality [55].

Authenticity, which is associated with job satisfaction and work engagement, is another characteristic of the workplace that HR managers should take into consideration [56].

Workplace actors, including colleagues and middle and top management, play a crucial role in shaping the organizational culture. Sustainable HRM actions are necessary in this regard to address issues such as discrimination and workplace bullying. For instance, Thorpe et al. (2014) examined the status and involvement of women in the fisheries sector in Sierra Leone. Despite fishing being predominantly seen as a male occupation, the authors found that women have a significant presence, particularly in postharvest stages. The authors emphasize the importance of gender awareness in this specific workplace [57]. In another article, Charlesworth and Macdonald (2015) discuss policy and regulatory developments in Australia that impact the working conditions of over 5.4 million women. These changes include the establishment of minimum labor standards and anti-discrimination protection for women workers. The authors argue that a national gender equality policy framework is crucial in ensuring fair treatment and opportunities for women [58].

4.2. Developing a Framework to Financially Support HR Development

Developing a framework to financially support human resources (HR) development involves creating a structured approach to allocate resources for the growth and enhancement of HR capabilities within an organization. By developing a comprehensive financial support framework, organizations can ensure that their HR professionals have the resources they need to stay current, contribute effectively to organizational success, and drive continuous improvement in HR practices. The acquisition and processing of data on a large scale is important to enhance organizational efficiency and provide access and understanding to necessary resources [59]. One way HR professionals could identify gaps in employee skills and knowledge is by using data analytics. This information can be used to tailor learning and development programs, ensuring that employees acquire the skills needed for both current and future roles, promoting sustainability in talent development.

To address RQ2: How can HR development, a key component of sustainable HRM, be integrated into long-term strategy? we examined and adapted concepts and tools from corporate finance. HR development is frequently linked with expenses, which raises questions about financial considerations. Training sessions and courses, although they enhance the quality of HR, necessitate a cost–benefit analysis. Engaging employees in their own skill development entails various implications. Decisions regarding whether to temporarily remove employees from their regular tasks to attend courses or to balance their involvement in ongoing processes while participating in after-work training sessions all involve financial costs.

In the first case, when employees are removed from their work, replacements are needed, and these replacements must be remunerated. Keeping employees at work full-time and sending them for additional training after hours can potentially affect their well-being and, subsequently, lead to decreased productivity, which can have negative financial consequences for the firm’s revenues.

To facilitate informed decision-making in HR development, this paper proposes a model that enables managers to identify the most suitable approach. The model consists of two parts: a feed-before approach and a traditional feedback analysis. Both approaches treat HR development investment as a project similar to other economic projects within the company. These approaches incorporate relevant tools from corporate finance, such as net present value (NPV) and future value (FV), adapting them to their specific requirements. While other methods like internal rate of return (IRR) or profitability index (PI) can also be valuable in identifying the optimal option, this paper aligns with Brigham’s (1982) viewpoint that the NPV method is the most reliable and recommended approach [60].

(a) Appling the net present value (NPV) method

It would indeed be valuable to estimate the future value of the impact of HR development on the firm’s revenues. The first adaptation made is that instead of a risk-free rate assimilated to the deposit interest rate in a bank, the average rate of return for the analyzed firm could be considered as an investment alternative. When financial managers and HR managers evaluate the opportunity of investing in HR development, they can utilize the net present value (NPV) method to assess its feasibility. Viewing HR development as a project allows for prioritization in comparison to the company’s regular activities. If the development of human capital can yield a higher return than the typical business operations, managers should give priority to this initiative. The focus is first on the positive nature of NPV and then on the magnitude of NPV. If the NPV is negative, the discussion becomes irrelevant. However, if the NPV is positive, the decision depends on the size of the NPV. Determining an appropriate significance threshold for the NPV value is crucial to give importance to the discussion. Estimating the future value of the impact on the company’s revenues is challenging as it depends on the nature of the company’s activities and the scale and quality of the HR segment being developed. Additionally, there may be various other factors influencing the impact’s size, but the significance of the two factors mentioned earlier should overshadow them.

where:

NPV—net present value.

PV—present value of the future increase in the firm’s revenues.

IC—implementation cost for the HR development method—i.e., the amount that must be paid for the training session or for the course.

Further, the present value of the future impact of the investment must be calculated.

where:

PV—the present value of the future impact of the investment.

FI—the future impact of the investment.

r—the average profit rate at the firm’s level. It can be the arithmetic average, the mean, or the weighted average of the profit rates the company is recording.

n—the number of years in which the impact should happen.

Once the calculations are completed, the NPV for the HR development project can be determined and used to evaluate the feasibility of the chosen method. It is important to acknowledge that the main limitation of this tool lies in the challenge of accurately calculating the future impact of the investment. However, there are companies for which this difficulty may be mitigated. The essence of this approach is its feed-before nature, which assists in identifying the appropriate HR development method. Nevertheless, it is crucial for every company to incorporate references to this type of impact in its future activity projections. By including considerations for HR development impact, companies can enhance their strategic planning and decision-making processes.

(b) Using the future value (FV) tool

Another valuable instrument (feedback-type) for conducting a cost–benefit analysis is calculating the future value of the amount invested in HR development. This instrument allows for analysis over various time intervals, such as one year, two years, and so on. Two main approaches can be employed in this stage.

The first approach involves comparing the calculated future value with the increase in the firm’s revenues. By calculating the difference between these two values, one can obtain a clear understanding of the profitability of the HR development investment.

The second approach entails assessing the future value through the break-even point of the calculated amount. In some cases, this analysis may yield a result in terms of the number of products that need to be sold to recoup the investment. However, a potential issue arises if the analysis is correlated with market share reports, revealing that the projected number of products cannot be sold within the existing framework.

It is important to carefully consider these findings and evaluate the feasibility of the HR development investment based on the projected future value and its alignment with market conditions and potential sales.

Translated in equations, this last paragraph appears as follows:

in which

FV is the future value of the amount paid as a fee for a training session or course.

The other notations remain as in the previous example, as future impact, used in the following lines, will be written as FI.

The analysis continues by calculating the ratios between the two indicators. Comparing the results with the value 1 could provide valuable feedback for the whole HR development operation.

FI/FV > 1—means that the investment was properly chosen.

FI/FV < 1—means that the investment should have not been made.

At the end of this feedback analysis, the timeframe in which such an investment could be profitable should be found.

4.3. Practical Implications

This paper proposes the integration of financial tools into human resource management (HRM) strategies, with a specific focus on sustainable practices. The findings underscore the significance of adopting a comprehensive model that not only prioritizes sustainable HRM but also substantiates the financial justification for investments in employee development initiatives.

The implications of this research extend beyond theoretical considerations, offering practical insights for organizations navigating the challenges of managing human capital within budget constraints. By introducing a systematic framework for evaluating the financial viability of HR development initiatives, the paper empowers decision-makers to align organizational goals with sustainable HRM practices. The proposed model represents an asset for strategic decision-making, helping HR professionals to bridge the gap between financial considerations and sustainable HRM practices.

By offering a solution-oriented approach, this paper supports organizations in optimizing their investments in employee development. This is crucial for enhancing workforce capabilities, fostering talent retention, and ultimately contributing to improved organizational performance.

The paper serves as a guide for organizations seeking to embed sustainability into their HRM practices. By integrating financial tools into HR strategies, organizations can not only achieve economic efficiency but also contribute to environmental and social sustainability through the development and retention of a skilled workforce.

This paper’s focus on sustainable HRM practices aligns with broader CSR objectives. Organizations can utilize the insights from the research to integrate socially responsible practices into their HRM, showcasing a commitment to employee well-being and development as part of their broader corporate citizenship.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this paper is to analyze the existing knowledge in the field of sustainable human resource management (HRM) and address the main inconsistencies through an interconnected approach. This approach supports the implementation of sustainable HRM strategies while also proposing the use of financial management tools to support and substantiate investments in human resource development.

The paper emphasizes the importance of a use–develop–repeat process, which, if properly designed, can lead to achieving a comparative advantage in pursuing sustainability in the workplace. Two main approaches regarding HR are proposed in this paper. The first approach focuses on the utilization of HR and discusses both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, as well as other methods to enhance the appropriate utilization of HR resources.

The second approach is dedicated to the development process of sustainable HRM and introduces tools that can be used to establish the financial feasibility of this process. These tools provide a means to assess the financial viability of investing in HR development initiatives within the context of sustainability.

Overall, the paper aims to address the gaps and inconsistencies in sustainable HRM by integrating financial management tools into the decision-making process. By considering the utilization and development of HR from a sustainable perspective, organizations can enhance their competitiveness and achieve sustainable outcomes in the long run.

This paper provides a theoretical foundation for organizations to make more informed and data-driven decisions regarding HRD investments. This aligns with sustainable HRM principles by ensuring that resources are allocated efficiently to initiatives that contribute positively to both human development and organizational sustainability.

Our paper proposes the integration of financial analysis into sustainable HRM, addressing a gap in the literature. By doing so, it extends the scope of HRM beyond traditional HR functions, making it more strategically aligned with organizational financial goals. The proposed financial tools offer a means to economically justify HRD investments. This contributes to the sustainability of HRM by demonstrating the financial returns and benefits of human capital development, making a strong case for continued investment in employee growth and well-being. The paper argues the importance of aligning HRD efforts with the organization’s sustainability goals. The proposed tools help HRM practitioners ensure that HRD investments contribute positively to all dimensions of sustainability. The theoretical framework and proposed financial tools create opportunities for further research in the field. Empirical studies that focus on validating the effectiveness of these financial tools in diverse organizational contexts are needed to advance the field of sustainable HRM. Sustainability is an evolving and crucial aspect of modern business and integrating it with HRD and finance creates a forward-looking approach.

Using the proposed tools, HR managers and practitioners can effectively substantiate their decisions regarding HR development. However, implementing such a process may encounter challenges, as some employees may resist change or struggle to meet the required performance levels. This highlights the importance of skillful HR managers who can identify suitable employees, nurture their talents, retain them within the company, and achieve a favorable cost–benefit ratio. Moreover, HR managers must develop a unique approach that cannot be easily replicated by competitors. This is crucial for realizing a comparative advantage and maintaining a competitive edge in the market.

By employing the adapted NPV or FV methods to establish the feasibility of HR development, the quality of sustainable HRM in a company can be enhanced. This, in turn, enables companies to grow in a sustainable manner. The main objective of this research was to design a model for the financial substantiation of HR development, adapting corporate finance tools to the specific needs of HR development within the context of sustainable HRM. The proposed model has significant practical implications.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. Future research should aim to test the proposed model in practice and make adjustments if necessary. Testing the model would not only contribute to further research but also reveal any limitations or challenges that may arise in its implementation. Additionally, it is crucial to consider the long-term effects of implementing such a model, which are beyond the scope of this study. Furthermore, the willingness to use the model for substantiating HR development investments may vary due to various factors such as company size, national and organizational culture, personal beliefs, and more. Data regarding this aspect are limited and warrants further investigation.

Even though this paper is mainly theoretical, it has the potential to guide practical applications in real-world organizations. By proposing financial tools, our paper lays the foundation for future practical implementations and empirical research, which can validate the effectiveness of the proposed tools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.-C.A. and M.-C.M.; methodology, M.-C.M.; formal analysis, L.-C.A. and M.-M.A.; data curation, L.-C.A.; writing—original draft preparation, L.-C.A. and M.-C.M.; writing—review and editing, M.-C.M. and M.-M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abrudan, L.; Matei, M.; Abrudan, M. Towards Sustainable Finance: Conceptualizing Future Generations as Stakeholders. Sustainability 2023, 13, 13717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, M.; Abrudan, M. Cultural dimensions and work motivation in the European Union. Ann. Univ. Oradea Econ. Sci. Ser. 2013, 22, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, N.; Prince, J.; Kabst, R. National culture and incentives: Are incentive practices always good? J. World Bus. 2020, 55, 101075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoche, K. Strategic Human Resource Management within a Resource-Capability View of the Firm. J. Manag. Stud. 1996, 33, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing Limited: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brotherton, B.; Woolfenden, G.; Himmetoglu, B. Developing Human-Resources for Turkeys Tourism Industry in the 1990s. Tour. Manag. 1994, 15, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Wright, P.M. On becoming a strategic partner: The role of human resources in gaining competitive advantage. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1998, 37, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Miller, D. People matter: Commitment to employees, strategy and performance in Korean firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, B.F.; Huang, S. Achieving sustainability through attention to human resource factors in environmental management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 1539–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Sánchez, A.; Barba-Aragón, I.; Sanz-Valle, R. Effects of training on business results. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2003, 14, 956–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A. Relationships between human resource dimensions and environmental management in companies: Proposal of a model. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A. The central role of human resource management in the search for sustainable organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 2133–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figurska, I.; Sokół, A. Optimization of Knowledge Management Processes through Benchmarking in Organizations. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbins, T.; Dundon, T. The Chimera of Sustainable Labour-Management Partnership. Br. J. Manag. 2015, 28, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doering, H.; Evans, C.; Stroud, D. Sustainable Varieties of Capitalism? The Greening of Steel Work in Brazil and Germany. Relat. Ind. 2015, 70, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.K.; Johnstone, S.; Procter, S. Regulation of work and employment: Advances, tensions and future directions in research in international and comparative HRM. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 2957–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savanevičienė, A.; Stankevičiūtė, Z. Smart Power as A Pathway for Employing Sustainable Human Resource Management. Inz. Ekon. Eng. Econ. 2017, 28, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wepfer, A.G.; Allen, T.D.; Brauchli, R.; Jenny, G.J.; Bauer, G.F. Work-Life Boundaries and Well-Being: Does Work-to-Life Integration Impair Well-Being through Lack of Recovery? J. Bus. Psychol. 2017, 33, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T. Sustainable human resource management as a driver in tourism policy and planning: A serious sin of omission? J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 873–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blašková, M.; Figurska, I.; Adamoniene, R.; Poláčková, K.; Blaško, R. Responsible Decision making for Sustainable Motivation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevičiūtė, Ž.; Savanevičienė, A. Designing Sustainable HRM: The Core Characteristics of Emerging Field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.A.; Jaaron, A.A.M.; Talib Bon, A. The impact of green human resource management and green supply chain management practices on sustainable performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Crocco, F.; Martin, A. Towards a sustainable HRM in Latin America? Union-management relationship in Chile. Empl. Relat. 2019; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chams, N.; García-Blandón, J. On the importance of sustainable human resource management for the adoption of sustainable development goals. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, M.; Kucharčíková, A.; Štarchoň, P.; Balážová, Ž.; Lukáč, M.; Stacho, Z. Knowledge and Human Capital as Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J. Putting employees at the centre of sustainable HRM: A review, map and research agenda. Empl. Relat. 2020; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buren, H.J., III. The value of including employees: A pluralist perspective on sustainable HRM. Empl. Relat. 2020; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, K.; Nilsson, E. Organisational Measures and Strategies for a Healthy and Sustainable Extended Working Life and Employability—A Deductive Content Analysis with Data Including Employees, First Line Managers, Trade Union Representatives and HR-Practitioners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vraňaková, N.; Gyurák Babeľová, Z.; Chlpeková, A. Sustainable Human Resource Management and Generational Diversity: The Importance of the Age Management Pillars. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meidutė-Kavaliauskienė, I.; Dudzevičiūtė, G.; Maknickienė, N.; Vasilis Vasiliauskas, A. The relation between aging of population and sustainable development of EU countries. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 2026–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Garrido, J.A.; Biedma-Ferrer, J.M.; Ramos-Rodríguez, A.R. Moderating effects of gender and family responsibilities on the relations between work–family policies and job performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 32, 1006–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strenitzerová, M.; Achimský, K. Employee Satisfaction and Loyalty as a Part of Sustainable Human Resource Management in Postal Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Saklofske, D. Positive Relational Management for Sustainable Development: Beyond Personality Traits—The Contribution of Emotional Intelligence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chillakuri, B.; Vanka, S. Understanding the effects of perceived organizational support and high-performance work systems on health harm through sustainable HRM lens: A moderated mediated examination. Empl. Relat. 2020; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, M.J.; Coutu, M.F.; Tremblay, D.; Sylvain, C.; Gouin, M.M.; Bilodeau, K.; Kirouac, L.; Coté, D. Insights into the Sustainable Return to Work of Aging Workers with a Work Disability: An Interpretative Description Study. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2020, 31, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radvila, G.; Šilingienė, V. Designing Remuneration Systems of Organizations for Sustainable HRM: The Core Characteristics of an Emerging Field. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 2020, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macke, J.; Genari, D. Systematic Literature Review on Sustainable Human Resource Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 208, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainzbauer, A.; Rungruang, P. Science Mapping the Knowledge Base on Sustainable Human Resource Management, 1982–2019. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The role of sex and family variables in burnout. Sex Roles 1985, 12, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Turner, J.A.; Brief, A.P. Correlates of burnout among public service lawyers. J. Organ. Behav. 1987, 8, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E. Research on Work Team Diversity: Progress and Promise. Perform. Improv. Q. 2008, 12, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Seo, J. The greening of strategic HRM scholarship. Organ. Manag. J. 2010, 7, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Jackson, S.E. Co-worker trust and knowledge creation: A multilevel analysis. J. Trust Res. 2011, 1, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Schuller, R.S.; Werner, S. Managing Human Resources; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, R.S.; Jackson, S.E.; Tarique, I. Global talent management and global talent challenges: Strategic opportunities for IHRM. J. World Bus. 2011, 46, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I.; Harry, W.; Zink, K.J. (Eds.) Sustainability and Human; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; Dunford, B.B.; Snell, S.A. Human resources and the resource based view of the firm. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S. Balancing employees’ extrinsic requirements and intrinsic motivation: A paradoxical leader behaviour perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2022, 40, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.; Schattke, K. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: Time for Expansion and Clarification. Motiv. Sci. 2019, 5, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; Woodman, R. Creativity and Intrinsic Motivation: Exploring a Complex Relationship. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2016, 52, 342–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, M.; Abrudan, M. Adapting Herzberg’s Two Factor Theory to the Cultural Context of Romania. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 221, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astvik, W.; Welander, J.; Larsson, R. Reasons for Staying: A Longitudinal Study of Work Conditions Predicting Social Workers’ Willingness to Stay in Their Organisation. Br. J. Soc. Work 2019, 50, 1382–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, R.; Taris, T.W. Authenticity at Work: Development and Validation of an Individual Authenticity Measure at Work. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, A.; Pouw, N.; Baio, A.; Sandi, R.; Ndomahina, E.T.; Lebbie, T. Fishing Na Everybody Business”: Women’s Work and Gender Relations in Sierra Leone’s Fisheries. Fem. Econ. 2014, 20, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, S.; Macdonald, F. Women, work and industrial relations in Australia in 2014. J. Ind. Relat. 2015, 57, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolu, R.; Stanca, L.; Bodog, S. Automated Recognition Systems: Theoretical and Practical Implementation of Active Learning for Extracting Knowledge in Image-based Transfer Learning of Living Organisms. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Control 2023, 18, 5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigham, E.F. Financial Management Theory and Practice; The Dryden Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).