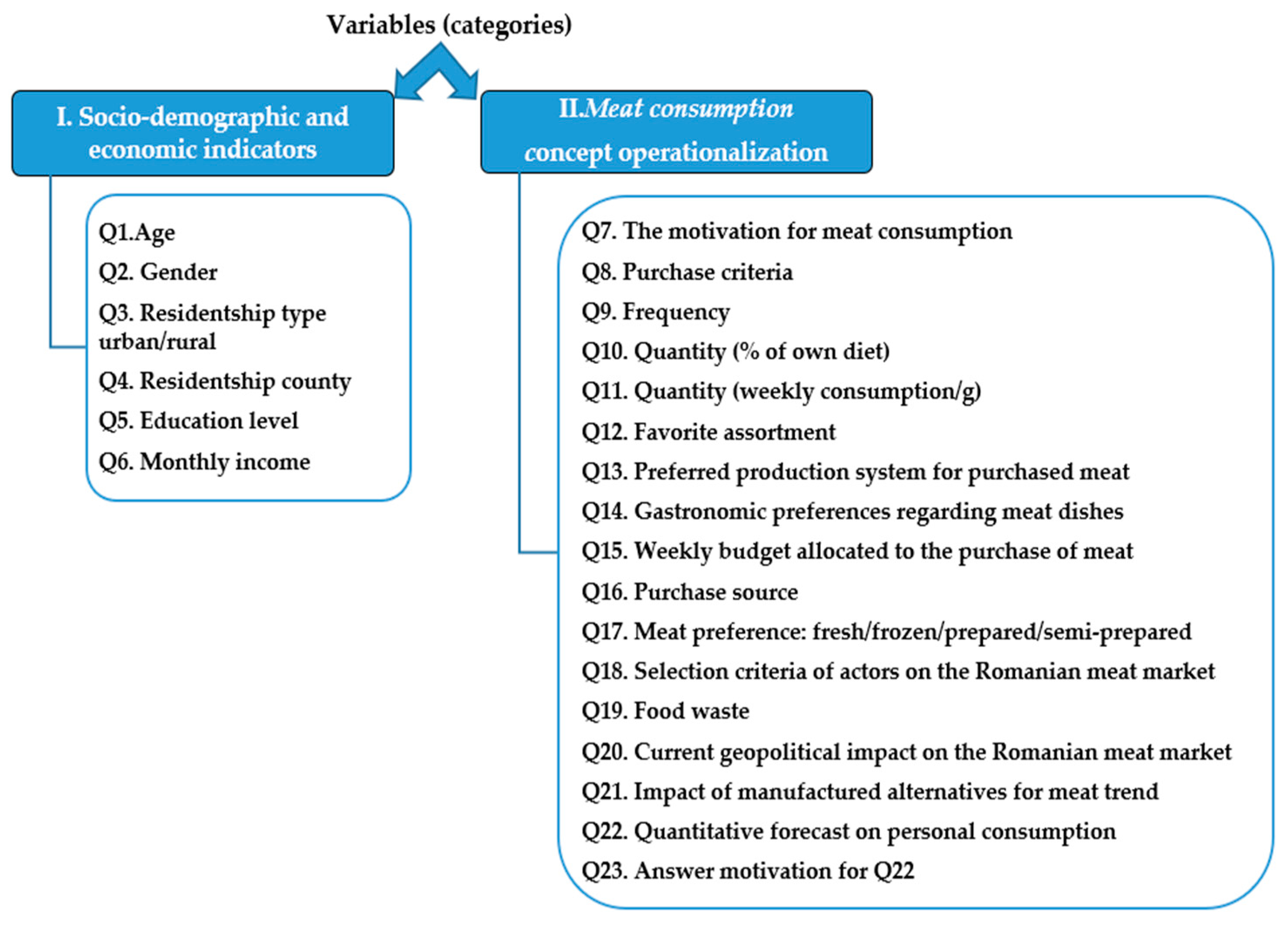

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistics—Interpretations and Suggestions for Correspondence with Results from Abroad

Table 3 provide an overview of respondents’ demographics, education level and income. Thus, 39.3% of respondents fell into the “21–30 years” age range, representing the largest share; another representative sample, 27.2%, belonged to the “31–40 years” range, which indicates a considerable participation of young people; the percentage of respondents aged “over 51 years” is quite low, being only 2.0%.

65.3% of respondents were female, while 34.7% were male. This may mean a greater preference of women to participate in surveys. 71.6% of respondents came from urban areas, compared to 28.4% who said they live in rural areas.

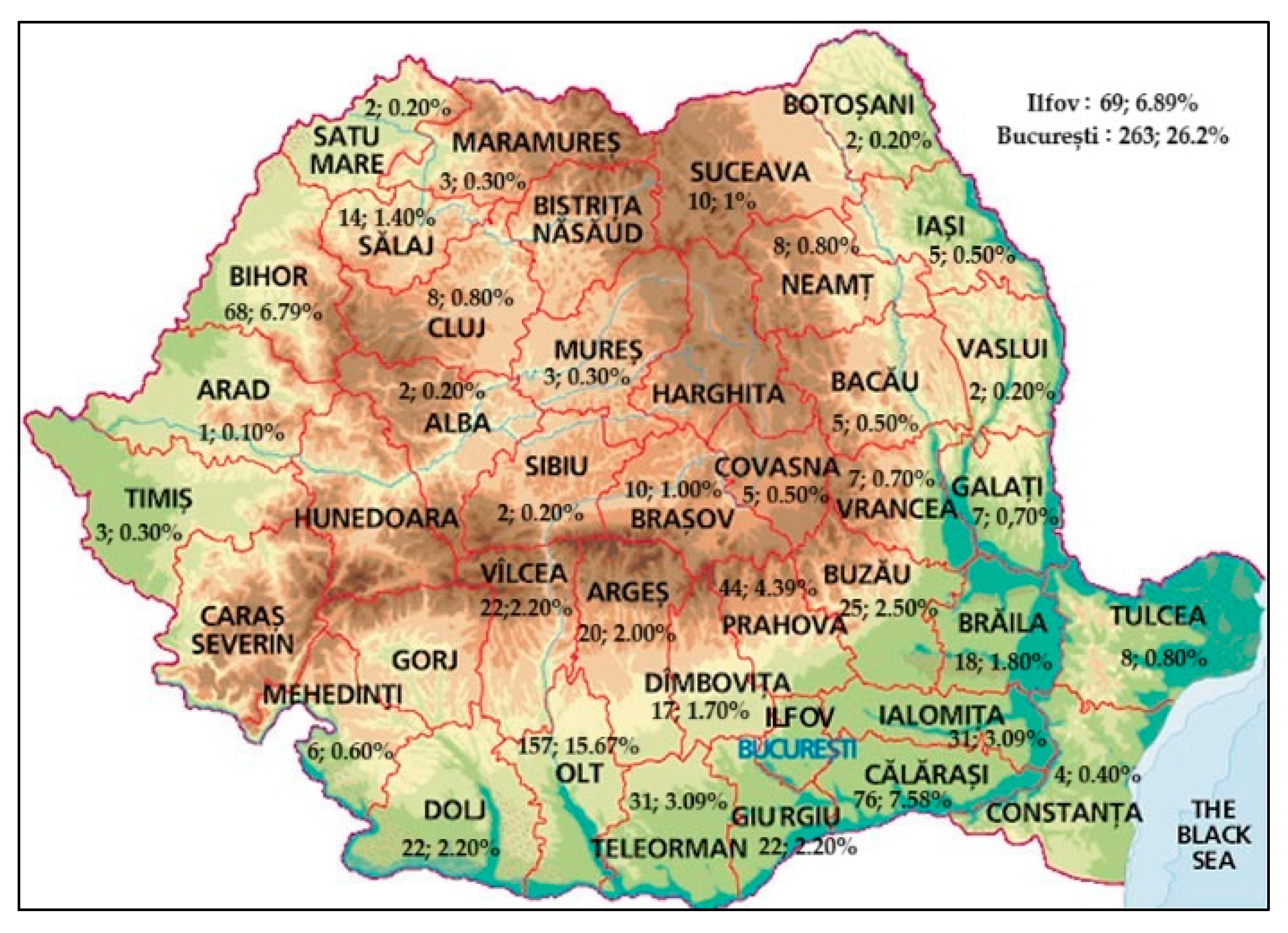

The distribution of respondents by counties shows that of the 41 counties and the capital Bucharest (according to NUTS 3 Romania), only from the counties of Harghita, Caras-Severin, Gorj, Bistrita-Nasaud and Hunedoara there were no respondents. Most questionnaires were completed in Bucharest (263) and Olt County (157)—

Figure 8.

In terms of education, the highest percentage is held by respondents with high school education, 38.9%, followed by those with bachelor’s degrees, 31.4%; 20.9% have completed master’s degrees, while only 5.4% have doctoral studies (

Table 3). According to studies conducted in Switzerland, it has been found that the amount of meat consumed in a household correlates with the level of education of the members who are part of it. In general, increased meat consumption is associated with people with higher education with unhealthy habits [

39].

34.6% of respondents said they get over 5001 lei/month (about 1000 Euro), and 19% less than 2500 lei/month; 18.2% earned between “3001 and 4000” lei/month and 17.9% between “4001 and 5000” lei/month; the lowest percentage was held by those with incomes between “2501–3000” lei/month (

Table 3).

More, our respondents stated that they prefer to eat meat especially because of the taste, nutrient content and variety of preparation (Q7). When buying meat, consumers considered as very important criteria the properties of the product, the producer, the place of purchase and the optimal quality-price ratio; important—price and less important product promotion (Q8).

More than half of the respondents consume meat “2–3 times a week” and over 30% “daily” while the lowest percentage was eating meat “once a month” (Q9). The daily or frequent consumption of meat (approximately 88.4% in total) represents an obstacle to sustainability, considering the large resources required for meat production, as well as the high greenhouse gas emissions associated with it. The fact that a significant segment of consumers (9%) consumes meat less frequently suggests that there is emerging awareness or openness to more environmentally friendly eating habits. This group represents a starting point for promoting sustainable diets, as these consumers are already inclined to reduce their reliance on meat in their diet. As a percentage of the diet, meat represented for most consumers “50%” and for about 25%—three quarters of the diet. For another important share, about 20% of respondents, meat accounted for “25%” of the diet (Q10). Most of the Romanians consumed 200–400 g of meat per week and more than 40% of these over 500 g (Q11). Increasing incomes in developing countries is helping to increase meat consumption (especially pork and chicken) by replacing traditional plant-based protein sources. This transition to animal protein is likely irreversible as incomes increase [

40].

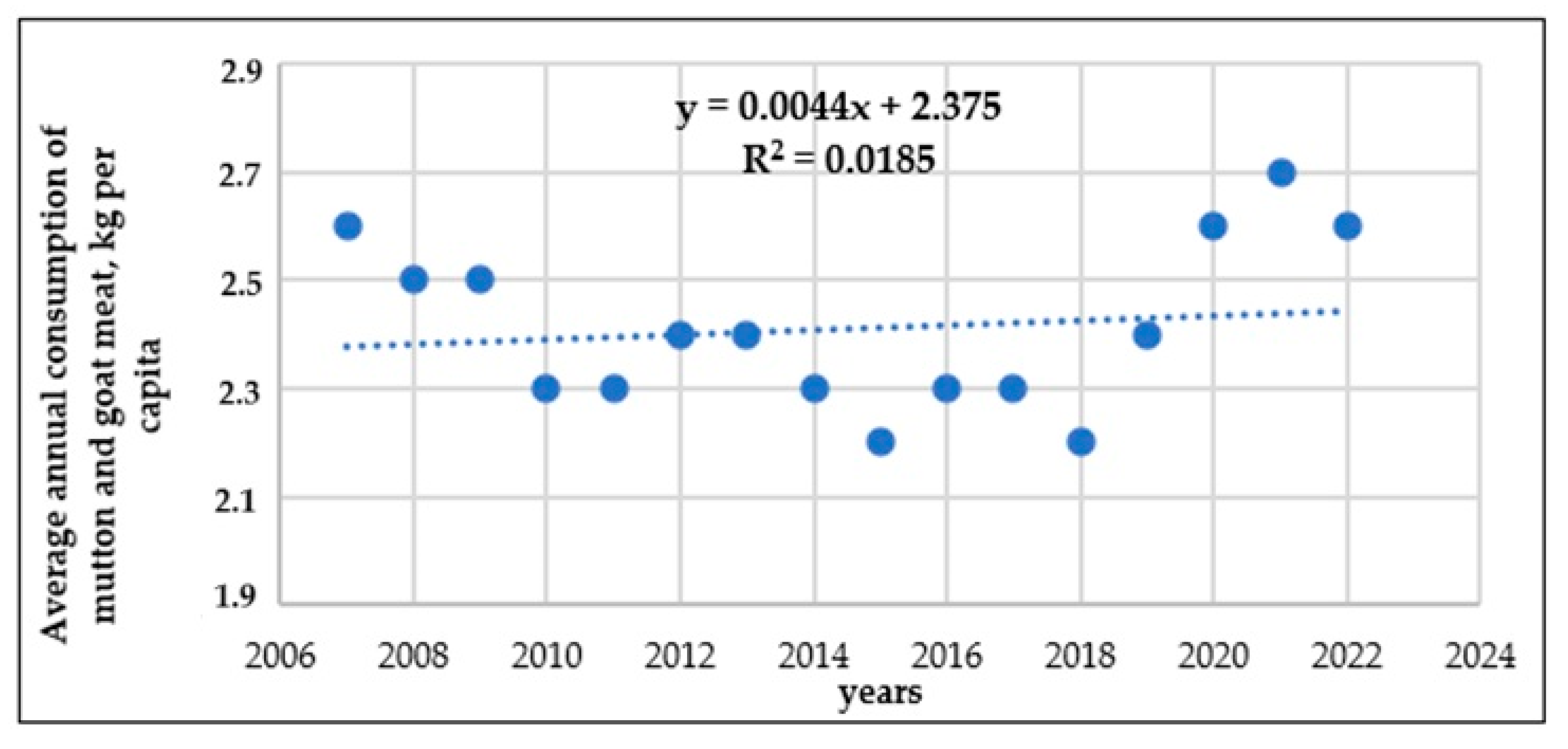

Poultry meat was preferred by 80% of those asked, followed by pork (over 60%) and beef (over 25%). Those who prefer mutton, accounted for less than 10% of respondents (Q12), according to other studies that showed that Romanian consumers’ preferences regarding types of meat are towards poultry and pork [

37]. As exemple, we found research conducted in Germany, showing that meat consumption is high and exceeds the recommended levels for a healthy and sustainable diet, requiring interventions to facilitate changes in the eating behavior [

41].

Meat produced in the “conventional” system was chosen by about 50%, and those who opted for meat produced in the “organic” system accounted for around 40% (Q13). These results support the idea of sustainable consumption by highlighting a significant proportion of consumers—approximately 40%—who prefer meat produced through “organic” methods. Organic products are typically associated with more sustainable farming practices, which do not use pesticides and chemical fertilizers, prioritize animal welfare, and, in many cases, production methods that reduce the impact on soil and water and support biodiversity.

Most of the respondents (70%) preferred “traditional Romanian specialties” and 40% “common dishes”. “Specialties from international cuisine” were liked by 22% of those questioned (Q14).

Around 80% of people spent more than 50 lei (about 10 euros) per week (on average/person) for the purchase of meat, but there is also the percentage of 20% who gave less than 50 lei (Q15). These aspects highlight that the environmental effects of higher meat consumption are more evident in higher-income households, according to the study in Chile [

16]. It is obvious that meat consumption is closely linked to the income of the population, but also to fluctuations in global meat prices, which can influence food security [

42].

According to the answers in the questionnaire, meat is most often bought from the supermarket (62.7%), specialized sellers (54%) and local producers (35.1%) (Q16). The literature has also shown that consumers’ preferences to buy meat are related to supermarkets and restaurants, compared to canteens [

43]. Over 90% of those surveyed said that they predominantly buy fresh meat; a considerably small category, of 20% of respondents, stated that they mainly buy frozen meat (Q17).

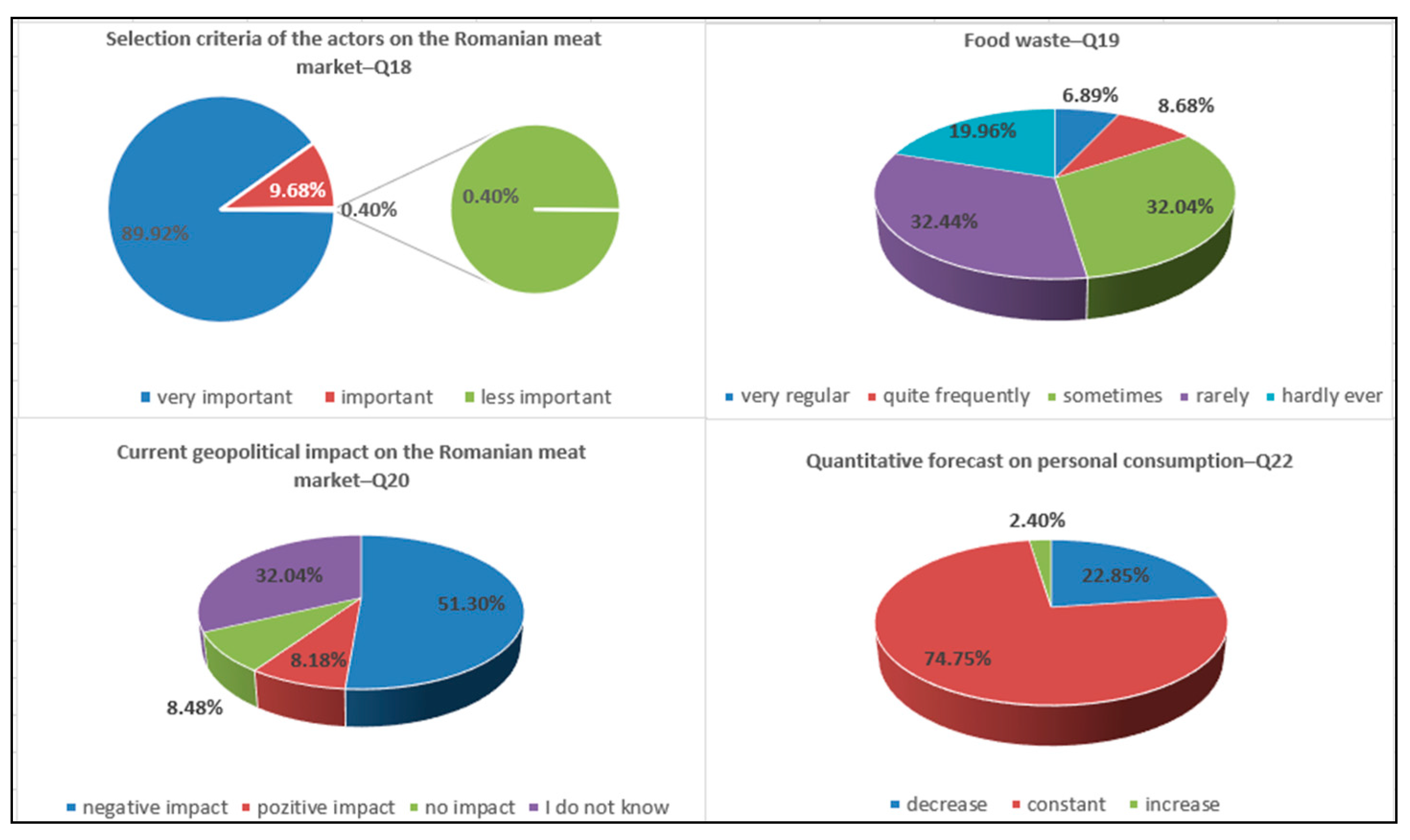

In order for the players on the Romanian meat market to satisfy the interests of consumers, it is necessary to monitor the quality of the products, to ensure places and conditions of purchase that respect hygiene and food safety, to offer a fair quality-price ratio and to select and certify bidders very carefully (Q18). Meat purchases are influenced by a number of economic and socio-demographic factors: affordability, quality, and perceptions and behaviours related to meat consumption, which differ according to the social, economic and cultural context specific to each region [

44].

On the other hand, it rarely happened in the households that expired products are “groceries and preserves” as well as “meat and meat products”, and sometimes bakery products, dairy products, vegetables, fruits and cooked food (Q19). For a group of 166 people, cooked food was declared as frequently expired, and for 134 people “bakery products”. The data presented support sustainable consumption by highlighting habits that contribute to reducing food waste, an essential aspect of sustainability. The analysis shows that in the studied households, expired products rarely include meat and meat products, as well as canned goods and staple foods, which reflects more efficient management of these food categories. Since meat production has a high ecological footprint, avoiding waste in this category is particularly important for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and the use of natural resources. More, a previous study conducted by the authors on food waste revealed similar results regarding expired food categories [

45]. The latest estimates of food loss and waste in the meat sector in the European Union are closely linked to greenhouse gas emissions [

46].

Romanian meat consumers appreciated that the geopolitical instability of the last period had a negative impact on the meat market (51%), and 32% answered with “I don’t know”. For 8% the impact was positive (Q20).

On the whole, the interviewees said that they do not like or do not consume meat alternatives, but there are also people who choose soy, mushroom, chickpea, pea dishes (Q21). So, we have identified a segment of the population that opts for dishes based on soy, mushrooms, chickpeas, and peas—reflecting their shift towards more sustainable foods, as these plant-based protein sources have a much lower ecological footprint than meat. Moreover, meat-based products combined with plant-based products as an intermediate solution for consumers who are not willing to completely give up meat represent a more sustainable food formula (“a plate”) by reducing the amount of meat used and, consequently, the negative environmental impact. Consumer preferences have been well received by meat companies, which have also introduced plant-based substitutes into production, with the consumption of these types of products expected to increase by 2028 [

47]. Estimates of plant-based alternatives (in particular legumes and oilseeds) will play an increasingly important role in the diet of the EU population [

48]. On the other hand, consumers who do not want to give up meat completely have the option of meat mixed with vegetable proteins, which is a more sustainable product [

49]. Another consumption option is cultured meat, which can contribute to global food security, especially in the context of population growth and climate change. Through the technology used, greenhouse gas emissions will be reduced and the use of resources (land, water and energy) will be reduced [

50,

51]. All these aspects are in the context of ensuring global food security through protein alternatives, such as: plant-based meat substitutes (with a lower ethical risk) and cultured meat [

52].

Over 70% of the survey participants estimated that meat consumption “will remain constant”, while in the opinion of 23% of respondents it will “decrease”. Only 2.5% believe that it will “increase” (Q22). However, it should be taken into account that there are a number of studies that refer to the negative effects on the health of the population generated by meat consumption. In this context, a series of social marketing actions have emerged, especially online, the objective being to reduce meat consumption [

53]. Decisions about meat consumption are also considered to have numerous effects on the environment. The high consumption, but especially of red meat, represents a direct threat to the health of the population [

54]. According to data provided by the Statista platform [

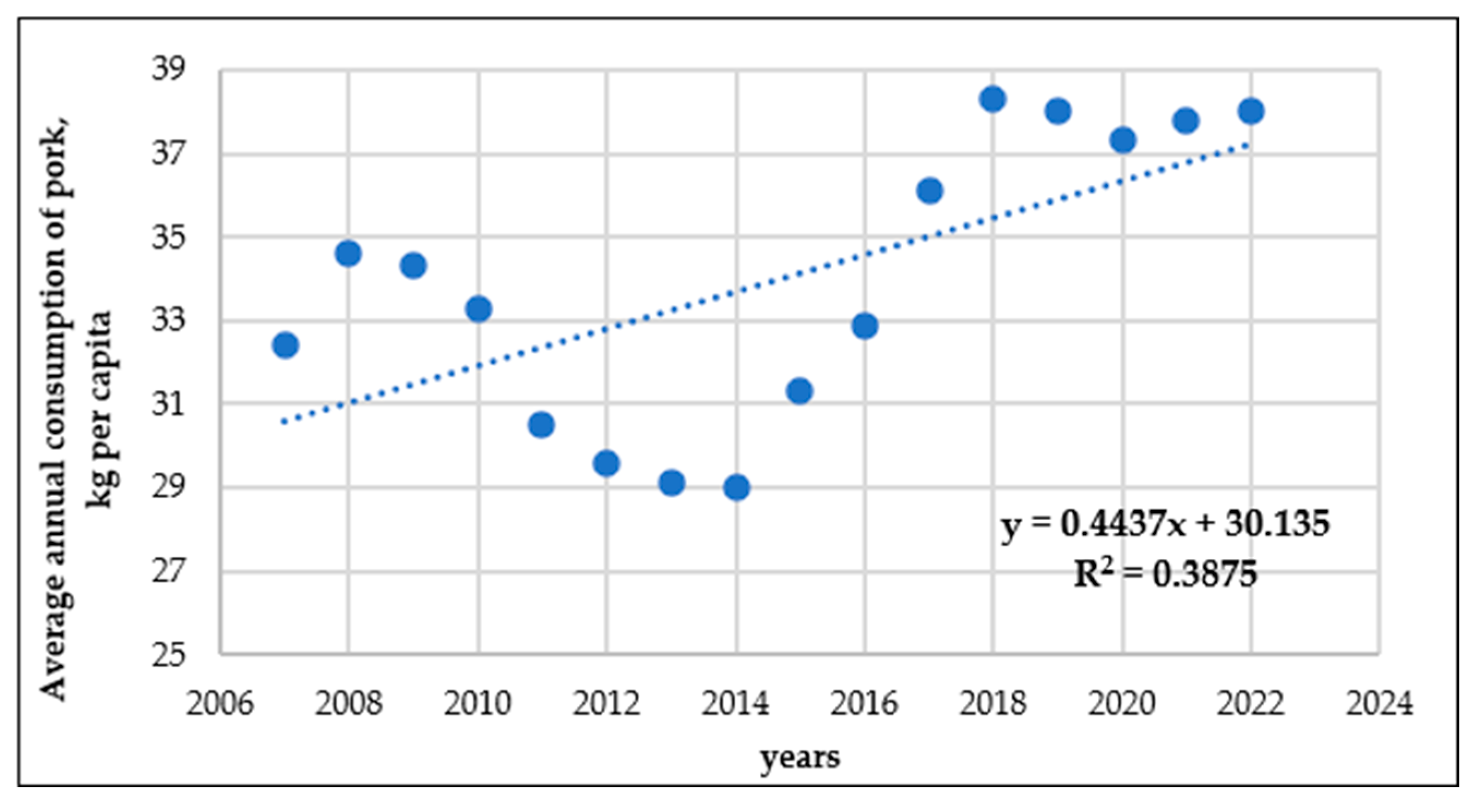

55], an increase in meat consumption is predicted by 2032, both worldwide (28.8 kg/capita) and continental. Globally, there are intense concerns regarding meat production, and changes in consumer behavior are also desired. In Europe, concerns about environmental impacts, animal welfare and food security are projected to lead to a decrease in pork consumption by 2031 to 31 kg per capita [

56]. The fact that more than 20% of our respondents believe they will reduce their meat consumption demonstrates a shift towards increasing sustainability among Romanians as well.

The motivation for answering question 22 (Q22) is due to the preference for meat or the change in the future of the meat-to-vegetable ratio in favour of the latter (Q23). For optimal nutritional status, policymakers need to be involved in the development of programmes that support healthy behaviours that drive the reduction of meat consumption in favour of fruits and vegetables [

57]. There are studies that promote the intensive consumption of insects, to the detriment of meat, which are based on their ecological advantages [

22]. In the future, the food industry will move towards products that will also have additional health-promoting functions, helping to prevent disease, through diet [

58]. Carbon footprint labels can be a viable and low-cost policy tool in the future to encourage more sustainable food choices, to the detriment of meat consumption [

59].

3.2.2. ANOVA Results and Discussions

For the ANOVA analysis in our study, we chose to report only analyses where we obtained significant results, meaning the p-value was below the significance threshold of 0.05, indicating that there are significant differences between group means, thereby leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis. We also indicated the level of the effect size measure (eta-square, η2). The results are presented in the tables below.

Thus,

Table 4 shows that there are significant differences in meat consumption among different age categories (Q1), as well as in terms of satisfying consumer interests. In these conditions, it is necessary for actors in the Romanian meat market to provide a fair quality-price ratio and carefully select and certify suppliers, as unconsumed or expired food products are usually bakery products, dairy, and prepared foods. At the same time, the estimation that recent geopolitical instability has a negative impact and the expectation that future meat consumption will remain constant is also influenced by age.

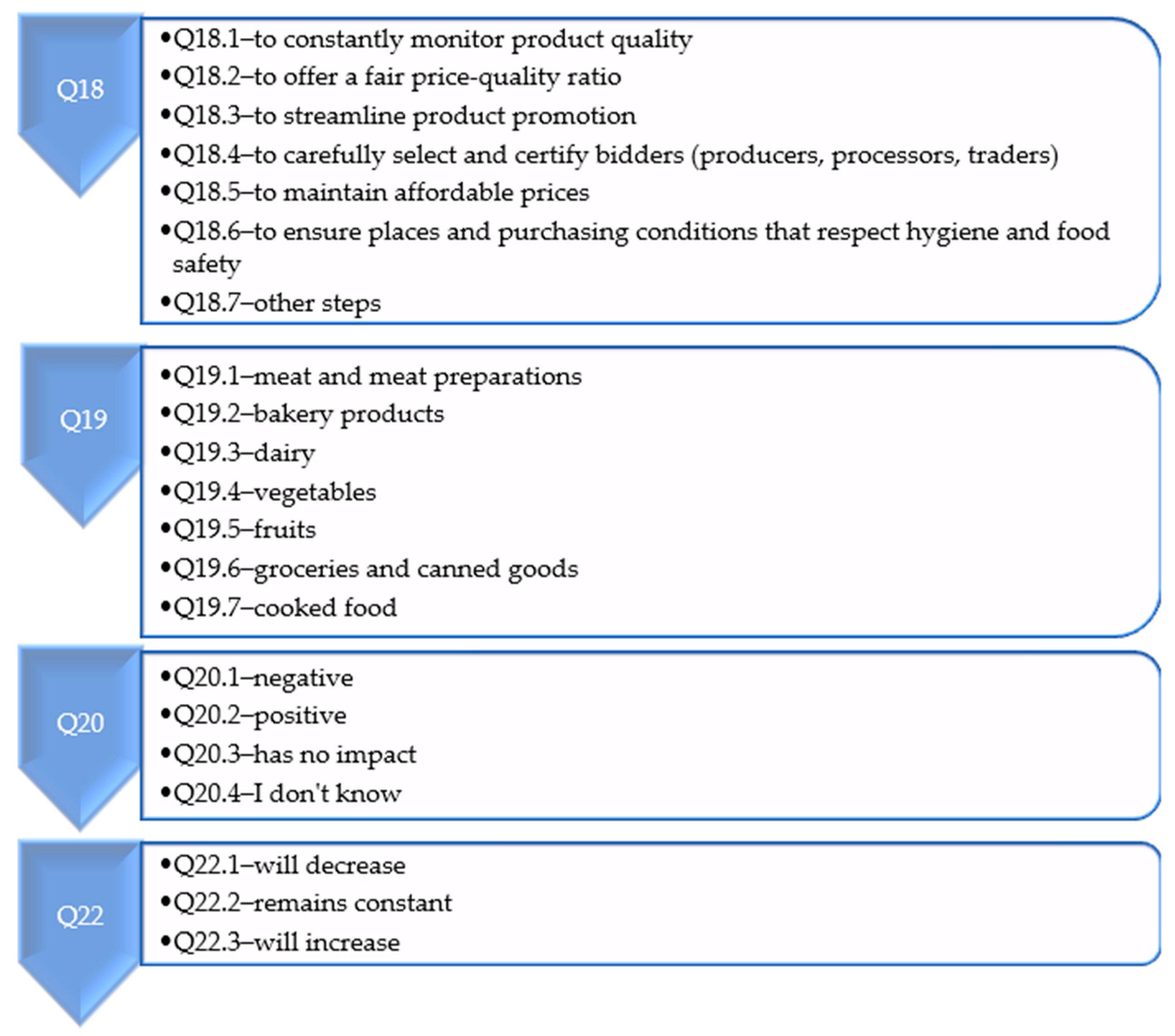

To facilitate the understanding and interpretation of the data in

Table 4, we introduce additional clarifications about variables Q18–Q20, Q22 in the form of

Figure 9.

In

Table 5, we highlighted that meat consumption differs based on gender (Q2). In this context, to meet the interests of Romanian consumers, it is necessary for actors in the meat market to consistently focus on product quality and ensure purchasing locations and conditions that adhere to hygiene and food safety standards.

In

Table 6, it was found that there are notable differences in meat consumption based on place of residence (rural versus urban, Q3), which necessitates that actors in the Romanian meat market provide a fair quality-price ratio. At the same time, it was indicated that unconsumed or expired food products are usually groceries and canned goods, and it is estimated that current meat consumption will remain constant.

The

Table 7 indicates that there are significant differences in meat consumption based on different levels of education (Q5). In this regard, it is necessary for actors in the Romanian meat market to maintain affordable prices and take similar measures. It was also noted that bakery products are the main unconsumed food items, while recent geopolitical instability has a negative impact on the Romanian meat market. However, it is estimated that future meat consumption will remain constant compared to current levels.

Table 8 showed that there are significant differences in meat consumption based on monthly income level (Q6). In terms of consumer interests, these are reflected in the need for operators in the Romanian meat market to optimize product promotion along with other measures. Additionally, monthly income differentiates the types of unconsumed products, namely meat and meat preparations. Recent geopolitical instability has a negative impact on the Romanian meat market, and it is expected that future meat consumption will remain constant compared to current levels.

Summarizing the results, at a social level, it should be borne in mind that consumers’ reluctance to behavioural changes may be related to food neophobia [

60,

61], social norms, traditions, as well as stressors in times of crisis (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) [

62], which may be contradictory to healthy eating habits, and thus, generating resistance to change.