1. Introduction

The global pursuit of efficient, safe, and high-energy-density batteries has led to significant interest in solid-state battery (SSB) technologies. SSBs promise numerous advantages over traditional liquid electrolyte-based lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), including improved safety due to reduced flammability, higher energy densities, and better thermal stability [

1]. SSB technology holds the potential to revolutionize electric vehicles by enabling longer driving ranges, rapid recharging, and safer operation. Additionally, SSBs can enhance portable electronics by providing more compact, lightweight batteries with extended lifespans, and a more sustainable and efficient energy storage solution for integrating renewable energy sources into the grid.

Despite SSB’s promising attributes, substantial challenges remain in areas such as lowering internal resistance [

2], increasing charge mobility [

3], reducing mechanical degradation from charge-discharge cycling [

4], and the use of environmentally sustainable materials [

5]. Additionally, scaling manufacturing poses significant barriers to widespread adoption [

6]. These limitations hinder progress in critical applications like electric vehicles, portable electronics, and renewable energy storage, where high performance and safety are paramount [

7]. There is a clear need for comprehensive research that systematically analyzes innovations addressing these issues across the battery ecosystem, including materials, manufacturing processes, and design architectures.

This study systematically analyzes patents to categorize innovations addressing key challenges in SSB design and manufacturing, focusing on performance, safety, and scalability. The methodology focuses on uncovering patterns and trends in patent filings related to the critical problem areas. By analyzing patent data across multiple dimensions, including time, geographical distribution, inventor engagement, and grant latency metrics, this study seeks to address the following research question: What are the current technological innovations and patterns emerging in SSB patenting activities, and how are they addressing the major challenges of performance, manufacturability, and sustainability?

While previous studies have explored SSB advancements, there is a lack of systematic patent analysis that categorizes innovations based on specific problem areas, such as ionic conductivity and manufacturability, to provide a clear roadmap for future research and commercialization efforts. This study fills that gap through a detailed cross-sectional analysis of patent filings to uncover emerging trends and technological focuses in SSB development. This study developed a systematic method for preprocessing, categorizing, and analyzing patent data. The process included data collection from a patent database, selected to reflect the most important international filings, text cleaning and filtering, duplicate removal, and multiple layers of subject matter expert (SME) reviews to distill problem and solution categories. A combined systematic review with cross-sectional bibliometric and thematic analysis of 244 patents uncovered trends in technological focus areas, inventor engagement, and geographic distribution. The bibliometric methods (histograms, scatterplots, boxplots, heatmaps) and thematic assessments (bigram word clouds, term co-occurrence network) provide visualization of trends and technological focuses in the patent landscape. This comprehensive approach ensures capturing key insights, linking innovations to specific problem categories such as charge conductivity, internal resistance, mechanical degradation, and energy density.

This work contributes to the literature by offering a detailed cross-sectional analysis of SSB patents that identify critical technological innovations. First, it provides a clear understanding of how different countries and companies are focusing their efforts, as illustrated through geographical and assignee-level patent distributions. Second, it highlights the most pressing problems that companies are addressing in SSB development and the types of solutions emerging, offering a valuable roadmap for future research and innovation. Finally, it offers a mixed method methodology incorporating both bibliometric and thematic visualizations to provide insights into the evolving landscape of specific problems addressed and their solutions, including ongoing efforts to enhance the environmental sustainability of energy storage solutions.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews the literature on both SSB reviews and patent analysis to assess related work and to substantiate the research gaps covered by this work.

Section 3 describes the mixed method methodology that analyzes both structured and unstructured data to identify trends and produce insights.

Section 4 presents the results of the mixed method bibliometric and thematic analysis.

Section 5 provides a detailed discussion on the specific solutions proposed within each problem category, acknowledges limitations in the work scope, and suggests future work to expand the scope.

Section 6 concludes the research by recapping the research motivations, methodologies, contributions, and findings.

3. Methodology

Unlike other databases, the USPTO, curated by a U.S. federal agency, is freely accessible and serves as an exceptionally reliable and comprehensive source for analyzing global innovations [

52]. Companies and inventors often prioritize filing patents at the USPTO due to the U.S. status as one of the largest and most competitive markets in the world, particularly for high-tech industries such as energy storage [

53]. Patents filed with the USPTO not only reflect domestic innovations but also represent international filings from companies investing in the protection of their most valuable technologies in the American market. This strategic focus on U.S. patent protection ensures that the database captures innovative global developments, making it an excellent representation of the forefront of SSB research. As such, the USPTO data provide a robust foundation for analyzing the state of SSB innovation worldwide, offering insights that are globally relevant and aligned with the most critical trends in the industry. Nevertheless, for some comparative analysis, the study conducted an identical search in the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) database [

54], which is global in scope and covers multiple jurisdictions.

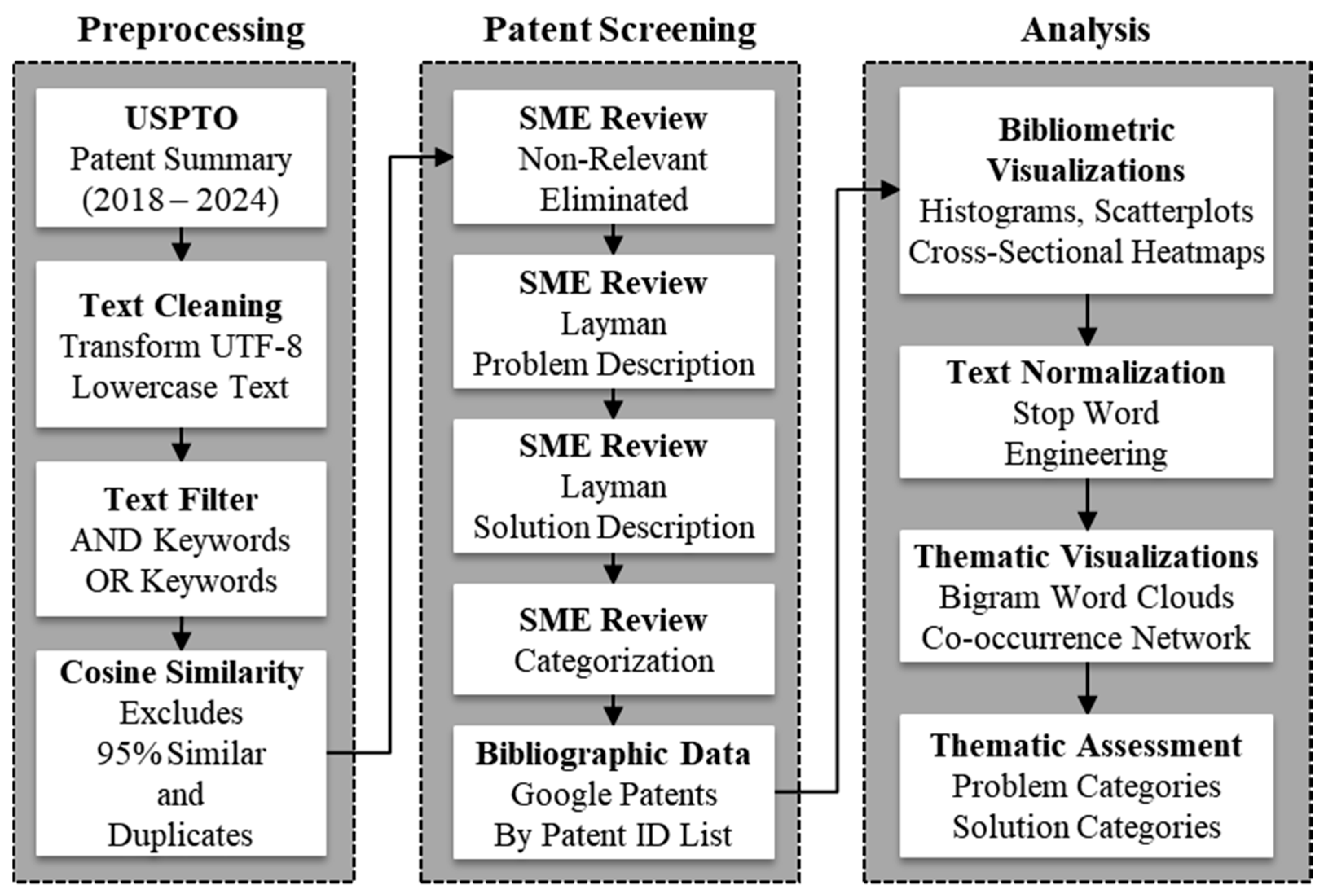

Figure 1 illustrates the methodical workflow that the author developed to conduct the systematic patent review and cross-sectional bibliometric and thematic analysis. The workflow began by preprocessing patent summaries collected from the USPTO, one tab-delimited file for each year from 2018 to 2024. Selecting 2018 as the start year was based on previous findings that the number of SSB patent awards were insignificant, in the low single digits prior to 2018 [

44]. Text cleaning and normalization followed to ensure accuracy of case-independent keyword searches, and the inclusion of wild-card characters to capture keyword variations.

In the text filtering procedure, the list of logic “AND keywords” constrained all the keywords to appear in the summary text, whereas the logic “OR keywords” meant that one or more of those keywords may additionally appear in the text. The AND keyword search logic was “*solid?state?batter*” and the OR keyword search logic was “vehicle, aircraft”. The wildcard character “?” allowed for variations like a dash separating the words. The wildcard character “*” found word variations like “All-solid” and “batteries” to ensure a sufficiently wide search cast. Empirically, adding more keywords to the AND keyword list resulted in an excessively narrow search, whereas adding more keywords to the OR keyword list resulted in too wide of a search. The final procedure in this phase conducted a cosine similarity vector analysis of the tokenized text to eliminate similar or duplicate patent descriptions.

In the patent screening phase, the author, who is a subject matter expert (SME), meticulously reviewed and eliminated non-relevant patents, followed by a brief non-technical synopsis of the problems and solutions identified. These synopses eliminated technical and patent jargon to describe the problems and solutions in plain English. The author then identified problem and solution categories for the patent summaries. The final procedure in the patent screening phase downloaded bibliographic information for the screened list of patents by presenting the list of patent numbers to the Google Patents search engine [

55].

The analysis stage of the workflow encompassed both bibliometric analysis of structured data and thematic analysis of unstructured data. The structured data included bibliometric metrics such as assignee, year, country, and grant latency. These provide valuable insights into the geographic distribution of innovations, patent ownership trends, and the temporal dynamics of patent approvals. This analysis allows for the identification of prominent assignees and countries driving SSB innovations, as well as patterns in patent filing and granting timelines. In parallel, the methodology utilized unstructured data from patent titles within each problem category, employing bigram word clouds and distribution analyses. This approach captured thematic patterns and linguistic trends within the patents, offering a deeper understanding of the focus areas within each category. Finally, constructing a term co-occurrence network from the combined text of patent summaries and titles revealed the relationships between frequently appearing terms in the SSB patent landscape.

By integrating both structured and unstructured data, this mixed methodological approach not only identified technological advancements but also uncovered nuanced trends in problem-solving approaches across the global SSB innovation landscape. The quantitative visualization of trends employed histograms, heatmaps, box plots, scatter plots, bigram word clouds, and a term co-occurrence network, fostering a comprehensive understanding of innovation patterns in SSB patents. The author developed all the software procedures shown in the workflow with Python (version 3.13.0), integrating the following libraries: pandas (version 2.2.3), matplotlib (version 3.9.2), seaborn (version 0.13.2), wordcloud (version 1.7.0), NumPy (version 2.0), and NLTK (version 3.9.1). Hence, all the figures produced in this study are original.

4. Results

The following subsections discuss the results by patent production, human resource, grant timing, and topic category metrics, followed by a thematic analysis. The discussion section that follows builds on the results to provide a more thorough assessment of the specific problems and solutions within each topic category.

4.1. Production Metrics

The preprocessing and patent screening workflow resulted in 244 patent summaries extracted from 2,160,575 total patents analyzed from 2018 to July 2024. Interestingly, these SSB-related patents accounted for 0.01% of the total USPTO patents awarded during that time.

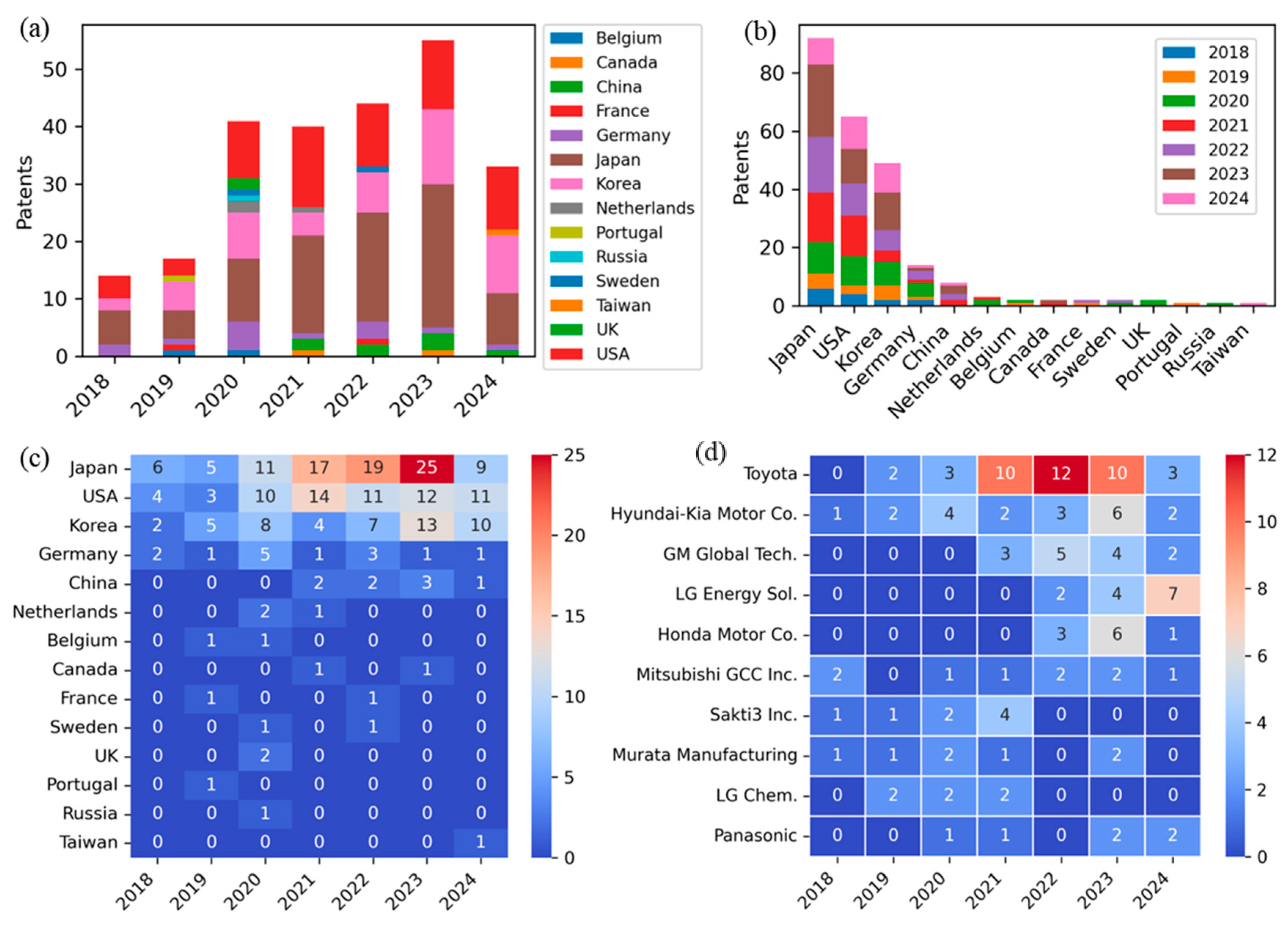

Figure 2 highlights these trends, broken down by year, country, and assignee.

Figure 2a shows there is a clear upward trajectory in the total number of patents awarded from 2018 to 2024, with a notable spike in 2023. The number of SSB-related patents issued in 2023 almost tripled that from 2018, highlighting the tremendous increase in SSB innovations. Japan and the United States emerge as consistent leaders in patent filings, with their contributions growing significantly in recent years.

Figure 2b reinforces the patent holding dominance of these countries, especially Japan, which far surpasses others, followed by the U.S. and Korea. The heatmaps in

Figure 2c,d provide more granular insights into the distribution of patent filings across countries and companies over time. Japan shows a marked increase in filings, particularly in 2023, while Toyota stands out as the most prolific assignee of international patents in the SSB domain, especially in recent years. These data reveal the intensifying global competition in SSB innovation, with a clear focus on industrial giants from Japan, Korea, and the U.S. leading the charge.

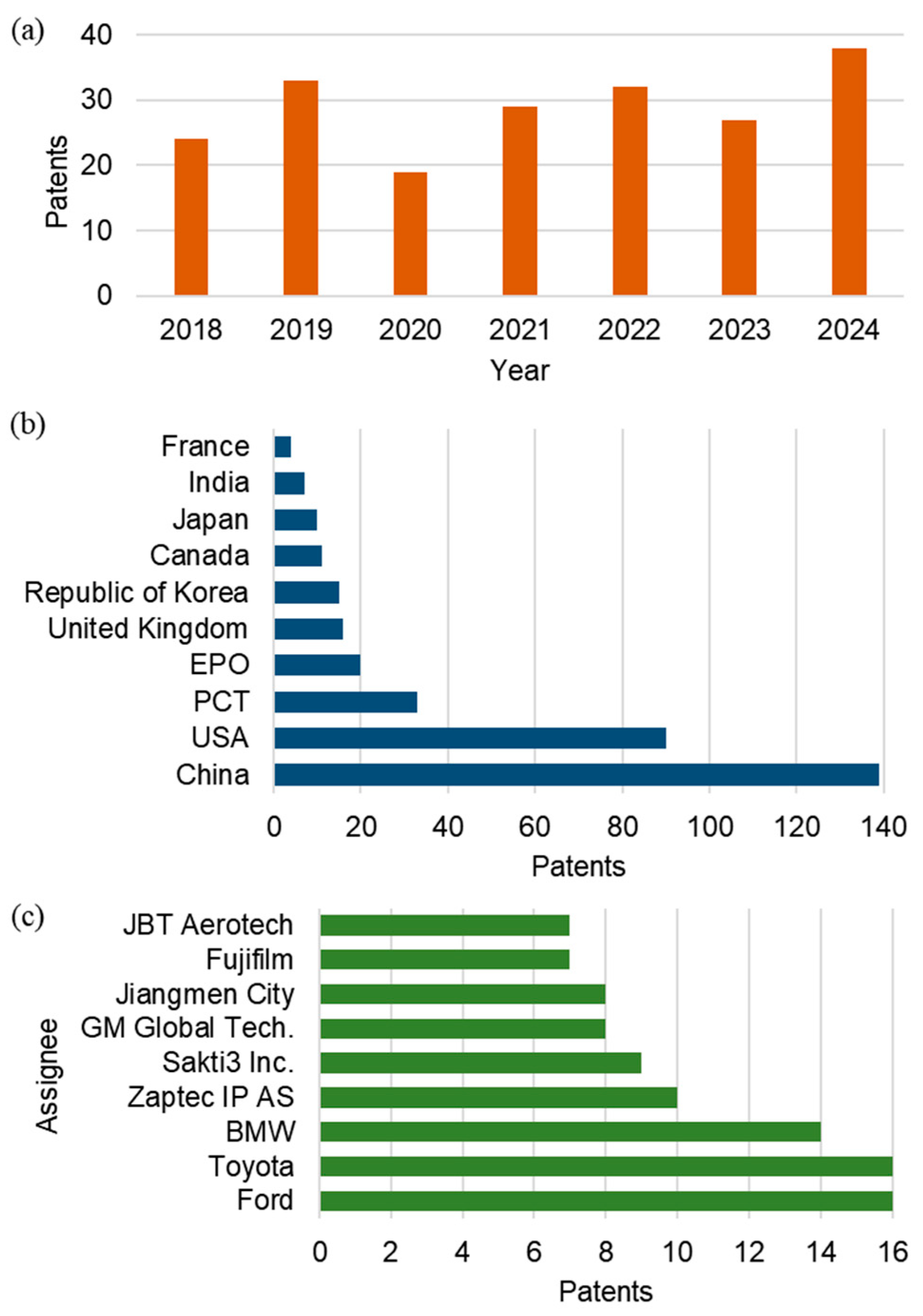

For comparative analysis,

Figure 3 presents results from an identical search in the WIPO database.

Figure 3a shows a steady trend in the number of global SSB-related patents that the database indexed annually from 2018 to 2024. While patent activity dipped slightly in 2020, likely due to global disruptions, the data reflects a resurgence in filings, suggesting renewed research and development efforts in recent years.

Figure 3b shows top filings in the patent offices that cover those jurisdictions indicated. Filings in the China patent office led by far, followed by the USA. The patent offices for other countries, such as the United Kingdom, Republic of Korea, and Japan, show much lower filings. The data also includes entries from the European Patent Office (EPO) and the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), providing a broader international scope.

Figure 3c shows that leading patent assignees include car manufacturers like Toyota, Ford, and BMW. Both the WIPO and USPTO datasets show an increase in patent filings over time. However, the WIPO data reflects a sample of local filings whereas the USPTO dataset includes all U.S. filings plus prioritized international patents. In the WIPO data, Toyota still leads, consistent with the USPTO findings. However, Ford and BMW ranked higher in the WIPO database than in the USPTO database, reflecting a preference for filing in their respective patent offices. These discrepancies suggest that WIPO filings are more influenced by local or regional patenting strategies, whereas USPTO filings reflect a broader intent to secure intellectual property in a globally competitive market like the U.S. Hence, while the WIPO database provides valuable international perspective, particularly regarding the dominance of China in the patent landscape, the USPTO dataset offers more balanced insights, making it a more robust source for studying trajectories in the intent to commercialize SSB technology.

4.2. Human Resource Metrics

Figure 4 provides insights into the human resources invested in SSB innovation, highlighting the distribution of unique inventors across countries and the collaboration intensity within patent filings.

Figure 4a shows that Japan, Korea, and the USA dominate in terms of the number of unique inventors, indicating strong research ecosystems in these countries.

Figure 4b reinforces this trend, where these countries show a particularly high correlation between patent volume and the number of unique inventors. This suggests that these countries are dedicating significant human capital to SSB development. In

Figure 4c, the histogram of inventors per patent reveals that most patents have three to four inventors, with an average of 3.8, demonstrating that collaborative efforts are common but not overly large. Lastly,

Figure 4d presents the results of an ANOVA analysis, which indicates statistically significant differences in the average number of inventors per patent across countries based on a

p-value close to zero. The blue boxes of the plot represent the interquartile range from 25% to 75%, and the whiskers extend from the smallest to the largest values, excluding the outliers shown as circles. The orange line represents the medians. These patterns reflect that inventorship varies significantly by country, potentially reflecting different organizational or industrial approaches to SSB research. Interestingly, the UK, Korea, and China typically have more inventors per patent than those from the U.S.

4.3. Grant Latency Metrics

Figure 5 presents critical timing metrics for the patent process in SSB technologies, offering insights into the timeline from public disclosure to grant.

Figure 5a shows that inventors tend to file patents quickly after public disclosure, with an average of 14.7 months and a high concentration within 20 months. This suggests that patent filers in this domain tend to act swiftly to secure intellectual property after initial disclosure to maintain an advantage after the competition becomes aware.

Figure 5b illustrates the time from patent filing to grant, with an average of 37.8 months, which is just over three years. Patent agencies grant most patents within 20 to 60 months after filing, indicating that the examination and approval process can vary significantly, with some taking up to 106 months.

Figure 5c shows the combined timeline from disclosure to grant averages 52.7 months, further emphasizing the length and variability of the patenting process, with some patents taking over 100 months.

Figure 5c also shows a significant decrease in the average time from filing to grant from 2018 to 2021 to 34 months, after which it increased again, reaching an average of 41 months in 2024. This trend potentially reflects a shift in patent office efficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, the data reveals a patenting process that, while variable, typically requires approximately three years from initial disclosure to final grant.

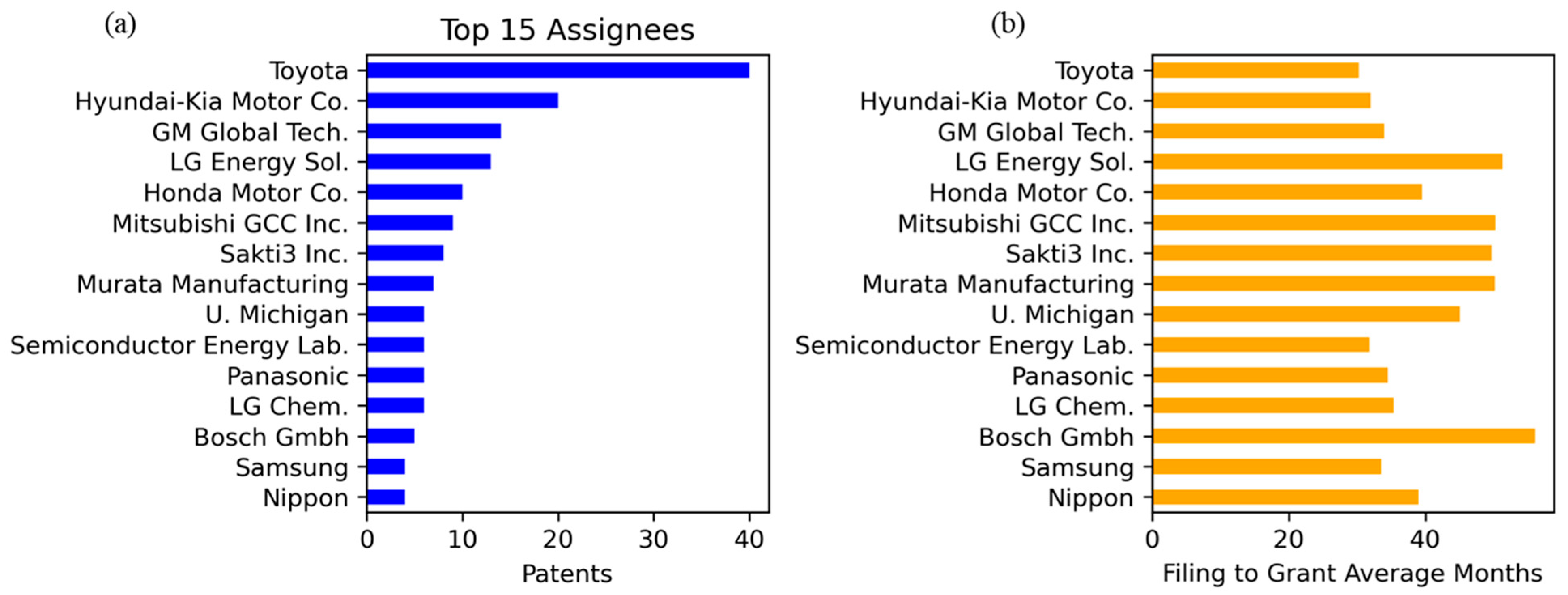

Figure 6 highlights the patenting activities and grant latency of the top 15 assignees in SSB filings. In

Figure 6a, Toyota (Toyota Jidosha Kabushiki Kaisha, Japan) emerges as the clear leader in patent filings, followed by Hyundai-Kia Motor Co. (Hyundai Motor Company and Kia Corporation, Seoul, South Korea), and GM Global Tech (GM Global Technology Operations LLC., Detroit, MI, USA), reflecting their substantial investment and innovation in this domain. Notably, the prominent players are automakers or their suppliers, revealing that they are heavily involved in the development of next-generation batteries for electric vehicles. This dominance highlights their drive to enhance battery technology for both performance and sustainability in electric vehicles.

Figure 6b provides insight into the time latency of these top patent assignees by illustrating the average months from filing to grant. Notably, Toyota not only leads in patent volume but also has one of the shortest timelines for patent approval, indicating efficient processing and robust technological advancement. For the top four assignees, there is an apparent negative correlation between the number of patents granted and the grant time latency. That is, the more patents obtained, the less time taken on average from filing to award. There is no clear relationship in timing for the remaining assignees that have far fewer patents in the field. This contrast in latency could reflect differences in the complexity of the patents or the administrative strategies adopted by these firms to navigate the patent approval process.

4.4. Categorical Metrics

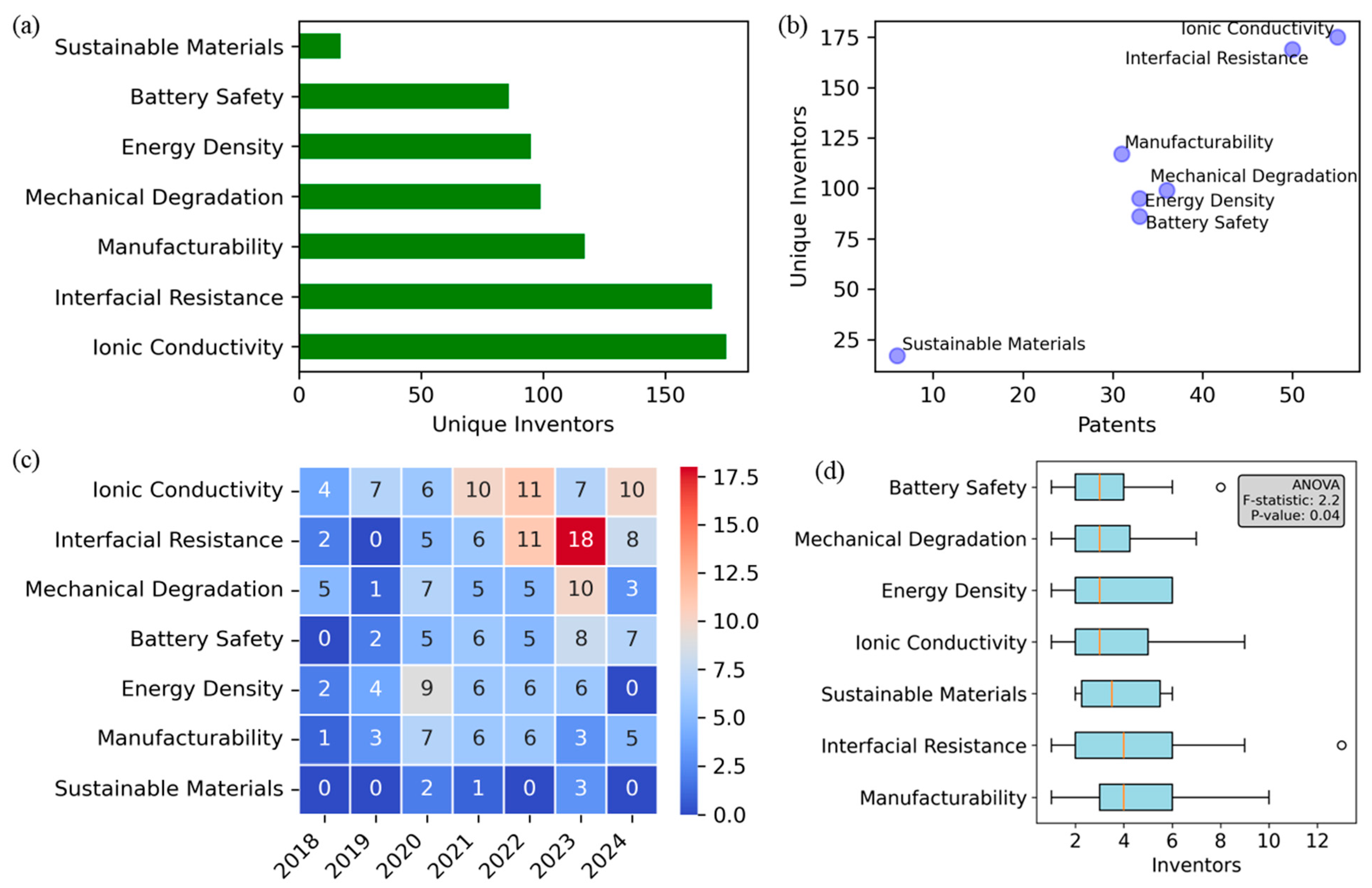

Figure 7 provides a detailed analysis of patenting activity across different problem categories of SSB development, focusing on inventor participation and patent distribution. In

Figure 7a, the categories of “Ionic Conductivity” and “Interfacial Resistance” stand out with the highest number of unique inventors, indicating the extensive research and development efforts in these areas, which are critical for improving battery performance. Conversely, “Sustainable Materials” has the fewest inventors involved, highlighting an underexplored but growing area that is likely to gain more attention as the industry pushes toward greener technologies. Future research in sustainable materials for SSBs could focus on developing eco-friendly solid electrolytes and electrode materials, such as bio-derived polymers and recyclable composites, which can reduce environmental impact while maintaining high performance. Exploring novel materials like carbon-based nanostructures and transition metal-free cathodes will be critical in filling the current gap and advancing the sustainability of SSB technologies.

Figure 7b provides a complementary view of the relationship between patent volume and unique inventors. It further highlights that while categories like “Ionic Conductivity” and “Interfacial Resistance” have high patent counts and inventor participation, “Sustainable Materials” lags significantly, suggesting that the field has yet to fully mobilize resources toward sustainability.

Figure 7c displays a heat map, indicating fluctuations in patent activity across categories and years, with “Interfacial Resistance” peaking in 2023. Finally,

Figure 7d shows the distribution of inventors per patent across categories, with “Ionic Conductivity” and “Manufacturability” having the widest variation in team sizes, suggesting differing levels of complexity or collaboration intensity in these areas. The ANOVA results (

p-value = 0.04) confirm statistically significant differences in the number of inventors per patent across categories, highlighting the distinct collaborative needs of each research focus.

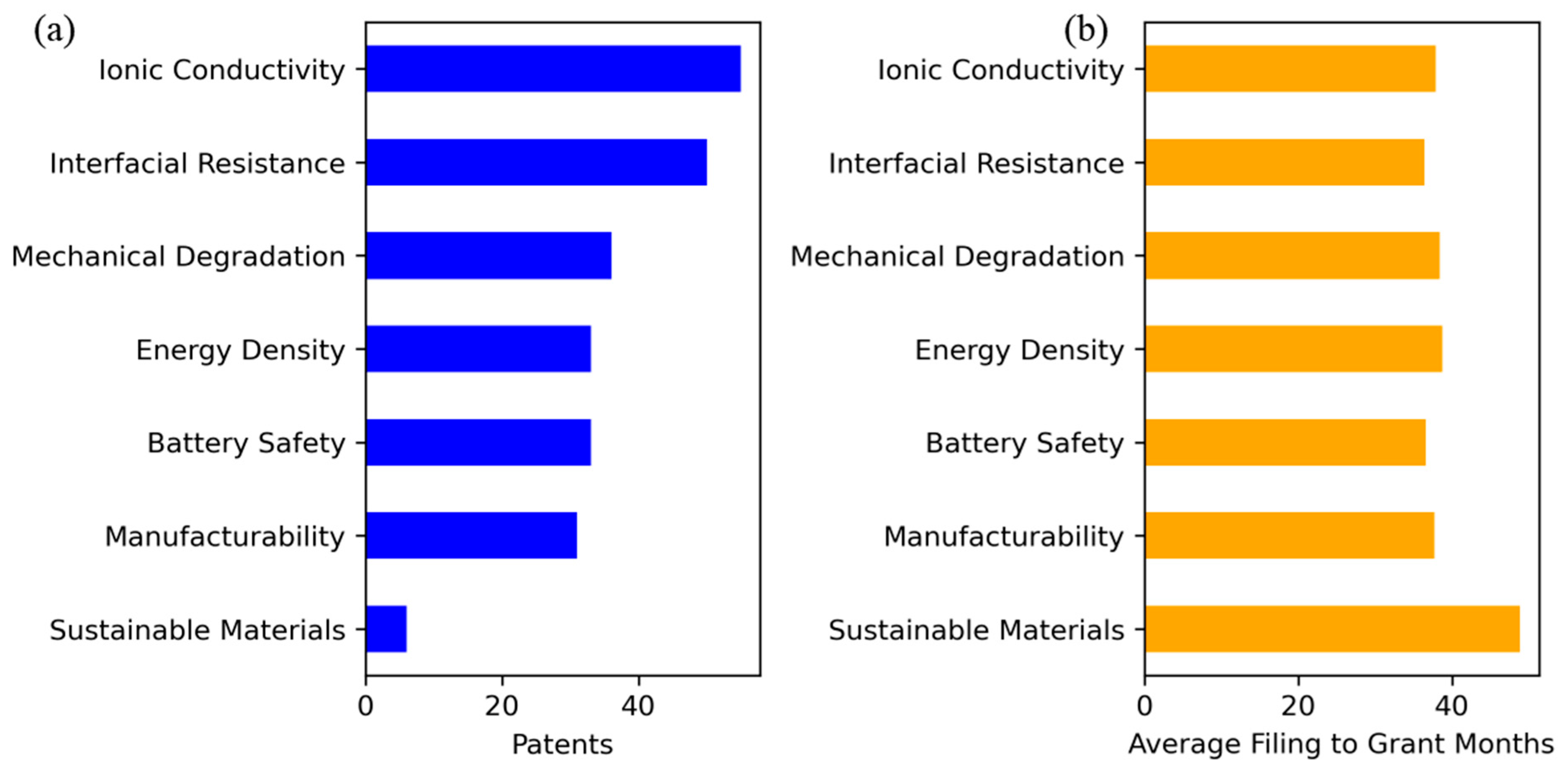

Figure 8 highlights the differences in patent volume and grant latency across key problem categories of SSB research.

Figure 8a shows that “Ionic Conductivity” and “Interfacial Resistance” lead in patent volume, but with no significant difference in time latency relative to the other categories. The exception is “Sustainable Materials,” with the fewest patents that also take a significantly longer time to process than patents in the other categories. This trend potentially reflects the novelty and complexity involved in developing sustainable alternatives that meet performance and scalability requirements.

Figure 9 provides an in-depth look at how countries are tackling different problems and their categorical approach to solutions within the SSB domain. In

Figure 9a, “Ionic Conductivity” emerges as the dominant problem addressed by most countries, particularly in Japan, USA, and Korea, reflecting a global focus on improving ion transport as a critical challenge for battery performance. Additionally, “Interfacial Resistance” and “Mechanical Degradation” also show notable attention, particularly from the same three countries, highlighting their key roles in advancing SSB research. Interestingly, only the USA and Canada have patents addressing “Sustainable Materials”, emphasizing the need for more international efforts in this area. Japan and South Korea lead in high-performance material development, while the USA emphasizes manufacturability and scalability. Europe focused increasingly on manufacturing innovation. Understanding these regional strengths can foster targeted international collaborations that leverage the complementary expertise of various regions to accelerate the commercialization of SSB technology.

Figure 9b focuses on the solution categories addressed by each country, with “Electrode Design” leading the field, particularly in Japan and the USA, indicating that advancements in this area are central to improving SSB technologies. Electrolyte design and manufacturing innovation also see significant contributions from Japan, USA, and Korea, highlighting the importance of enhancing battery architecture and developing scalable production techniques. The lower contributions to architectural innovation suggest that while systems and structural designs are crucial, they remain a secondary focus compared with material and manufacturing improvements. These patterns suggest that while the global focus is on improving material properties, advancements in sustainable solutions and architectural design are critical to long-term innovation.

Figure 10 highlights the intricate connections between problem and solution categories and between assignees and problem categories within SSB innovation. In

Figure 10a, the most prominent pattern is the strong focus on manufacturability challenges, which companies primarily address through manufacturing innovation solutions as expected, with less emphasis on other solution categories.

Additionally, companies often tackle interfacial resistance and ionic conductivity problems through advancements in electrode design and electrolyte design, respectively, which is consistent with expectations. Interestingly, companies tackled energy density problems primarily through architectural innovation and electrode design but not electrolyte design. This is consistent with expectations that electrodes store the charge, whereas electrolytes serve as the media for charge transport. Surprisingly, innovations in electrode design within the analyzed patent filings have not yet contributed toward solving the manufacturability problem, suggesting that this is potentially a research gap.

Figure 10b shifts the focus to the patent assignees and their contributions across problem categories. Toyota stands out as the leader in addressing interfacial resistance and ionic conductivity, demonstrating its commitment to overcoming key performance barriers in SSBs. Hyundai-Kia and LG Energy Solutions (Holland, MI, USA) also put a strong emphasis on improving interfacial resistance and mechanical degradation. In contrast, smaller companies like Sakti3 Inc. (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) concentrate more on manufacturability, potentially reflecting their specialized research directions. These patterns highlight the varied strategies of companies in tackling the multifaceted challenges of SSB development.

4.5. Thematic Analysis

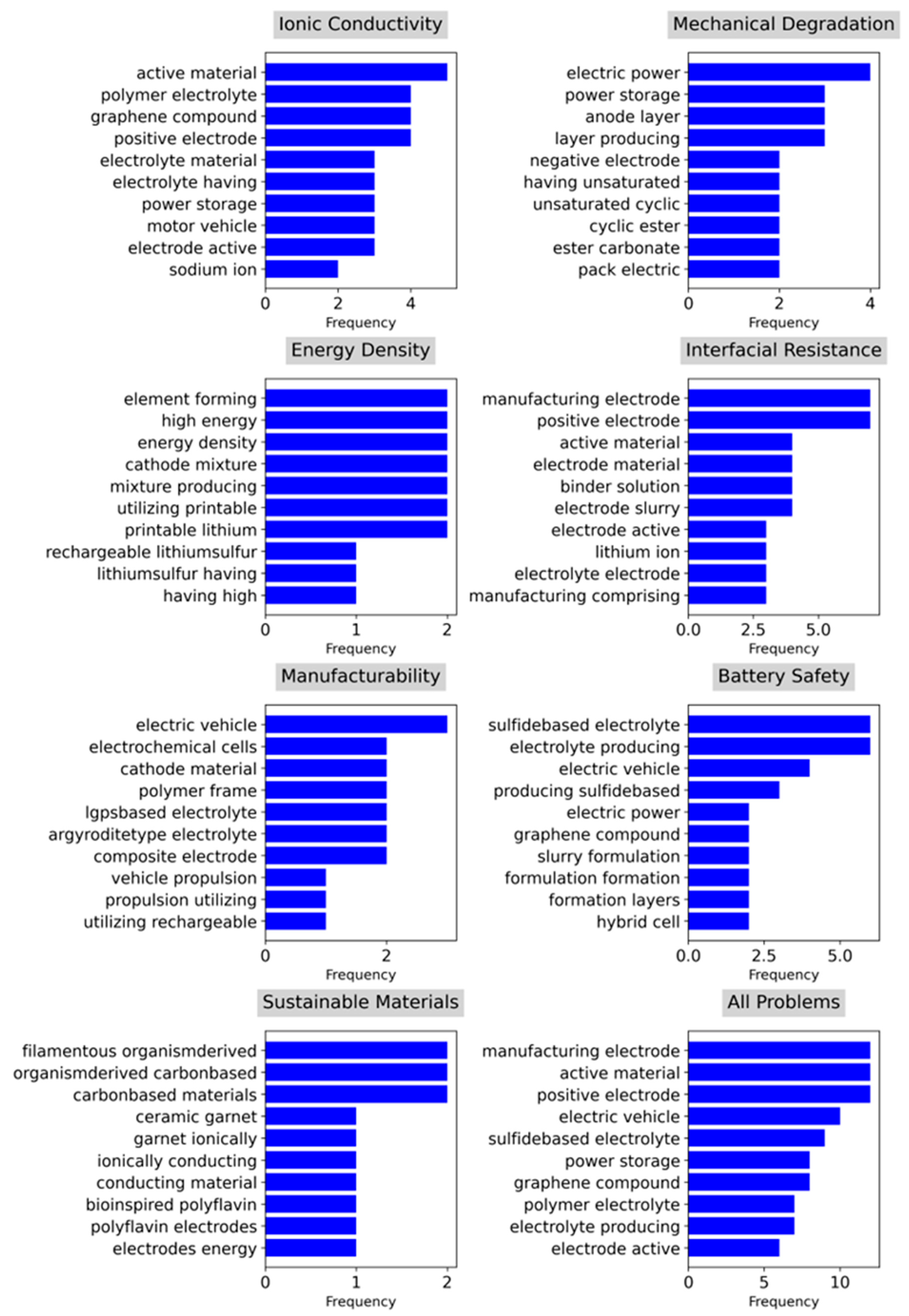

Figure 11 presents word clouds generated from patent titles, categorized by the various problem areas in SSB technology.

These word clouds collectively offer a snapshot of the key technological directions pursued within each problem domain. The size of the words reflects the frequency of their occurrence, providing insight into the core focus areas within each category. For instance, in “Ionic Conductivity”, terms such as “polymer electrolyte” and “graphene compound” dominate, highlighting the leading role of electrolyte materials in improving ion transport efficiency. Similarly, “Mechanical Degradation” is heavily associated with “electric power” and “anode layer”, indicating the emphasis on stabilizing electrode structures to mitigate mechanical failures, particularly in high power applications like EVs.

In “Energy Density”, keywords like “high energy” and “element forming” stand out, signaling the ongoing innovations to maximize energy storage capacity by careful element formation. For “Interfacial Resistance” and “Battery Safety”, the prominence of terms like “manufacturing electrode” and “sulfide-based electrolyte” suggests a focus on both optimizing electrode interfaces and improving electrolyte stability to enhance safety. Interestingly, “Sustainable Materials” features eco-friendly terms such as “carbon-based materials” and “filamentous organisms,” reflecting a novel approach toward greener alternatives in battery production.

Figure 12 complements the insights from

Figure 11. The figure provides a more detailed breakdown of the top 10 bigrams within each problem category, while also offering a closer look at the distribution of terms across research problem areas. In “Ionic Conductivity,” the even distribution of bigrams like “positive electrode” and “polymer electrolyte” suggests a balanced emphasis on both material innovation and functionality.

The “Mechanical Degradation” category displays a steep drop-off after the leading term “electric power,” indicating a concentrated focus on addressing specific challenges in high power applications like EVs. In contrast, the distribution in “Energy Density” shows a flat curve for the top seven terms, with a wider variety like “element forming” and “cathode mixture” appearing frequently. This reflects a broader approach to optimizing energy storage, resonating with the diverse terms shown in the corresponding word cloud. “Interfacial Resistance” reveals a less uniform term distribution, with frequent mentions of “manufacturing electrode” and “positive electrode”, emphasizing a holistic focus on improving interface performance across multiple dimensions. For “Battery Safety”, there is a marked dominance of terms such as “sulfide-based electrolyte”, but the distribution also highlights secondary areas of focus, such as “graphene compound,” supporting the diverse concerns about safety and performance illustrated in the corresponding word cloud. Lastly, the distribution in “Sustainable Materials” is sparse, indicating a narrower yet emerging focus on terms like “filamentous organism-derived” and “carbon-based materials”. This reflects the still niche interest in sustainable alternatives, as depicted in the corresponding word cloud. Overall, the bigram distributions offer a quantitative complement to the qualitative patterns visualized in the word clouds, revealing both concentrated research efforts and broader innovation trends across SSB development.

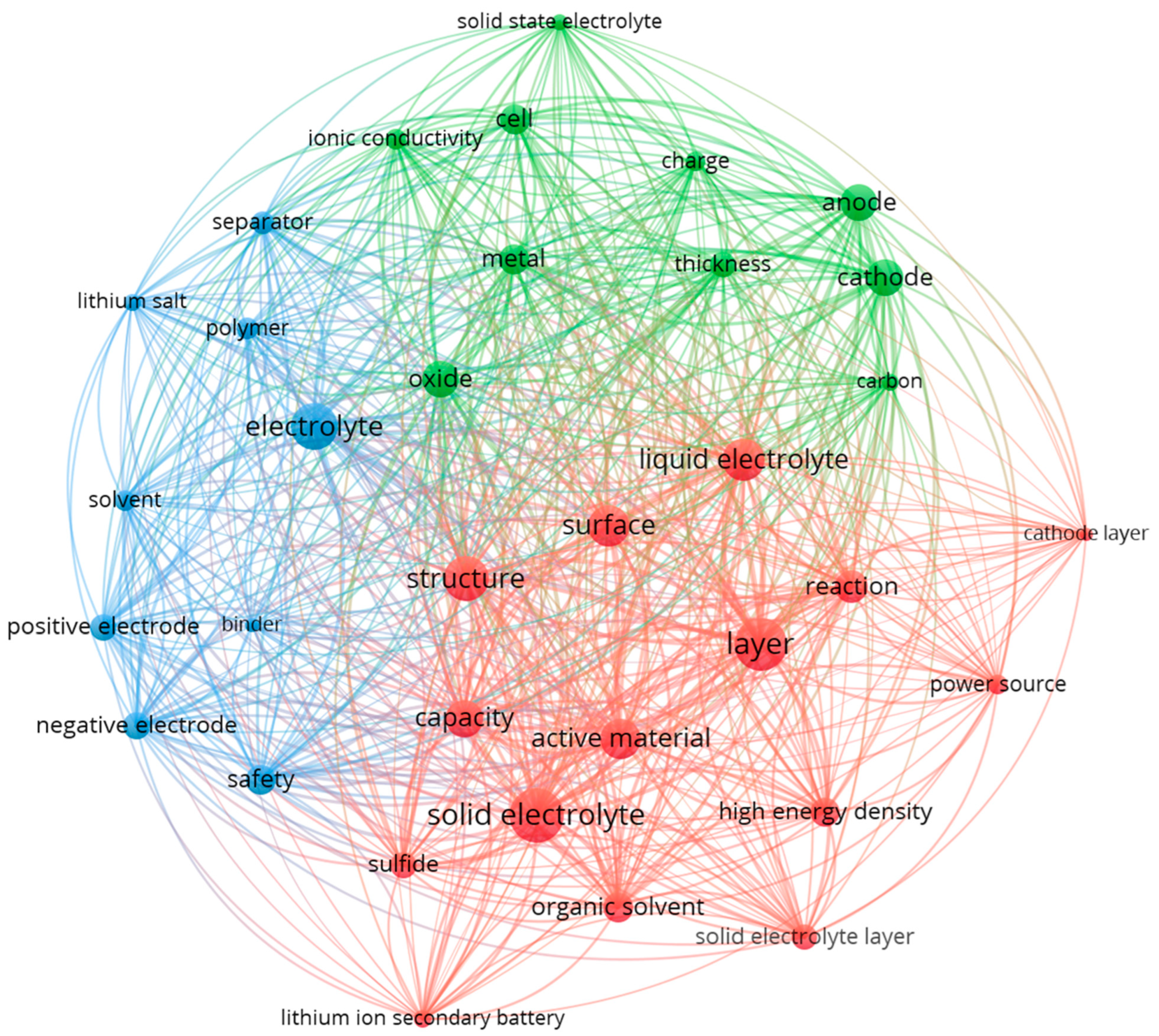

Figure 13 is a term co-occurrence network generated from the combined patent summary and title, after removing stop words that convey fewer insights. The network highlights the relationships between frequently appearing terms in the SSB patent landscape. The network also provides insights into the interconnectedness and interdependencies of material and structural considerations in balancing efficiency, safety, and performance. The VOSviewer software (version 1.6.20) produced the network for terms that appeared at least 40 times in the combined corpus [

56]. The size of the bubbles reflects the relative frequency of individual occurrence, whereas the thickness of a line connecting two terms reflects the frequency of their co-occurrence across the corpus. The distinct colors represent patent clusters where those words tend to appear frequently together.

It is apparent that the green cluster focuses on structural components such as “anode”, “cathode”, and “cell”, from the corpus subset, highlighting efforts to improve battery architecture and performance. The red cluster emphasizes materials and chemical interactions, with terms like “layer”, “solid electrolyte”, and “reaction”, pointing to innovations in electrolyte design and material interactions to enhance capacity and energy density. Meanwhile, the blue cluster centers on safety and electrolyte development, with terms like “electrolyte”, “polymer”, and “separator”, reflecting ongoing advancements aimed at improving battery safety and stability.

5. Discussions

The subsections that follow discuss the observed patent trends, provide an overview of the specific problems addressed by the patents reviewed, and the specific solutions provided within each of the problem categories.

5.1. Patent Trends

The author selected the USPTO as the primary data source because it captures both domestic innovations and international patent filings, reflecting global trends in high-value technological advancements. Additionally, a comparative search in the WIPO database ensured broader coverage of global patent activities. The pre-processing phase of the workflow involved text normalization, which included removing duplicates, standardizing terminology, and applying wildcard logic to ensure comprehensive keyword matching. Tokenization and cosine similarity analysis identified and eliminated redundant patent summaries, improving the accuracy of thematic classifications. Topic classification grouped patents into categories based on their relevance to identified problem and solution areas, such as ionic conductivity and manufacturability.

The patent analysis revealed a consistent increase in patent filings for SSBs since 2018, with a notable surge in 2023, suggesting accelerated research and development efforts. This trend reflects a shift toward addressing critical performance bottlenecks, particularly in ionic conductivity and interfacial resistance, which align with the priorities for commercialization. Toyota emerges as the leading patent assignee, reflecting its dominant role in advancing SSB technology, particularly in interfacial resistance and ionic conductivity solutions. Other significant contributors include Hyundai-Kia and LG Energy Solutions, which focus on innovations in interfacial resistance and mechanical stability, showcasing their strategic emphasis on scalability for electric vehicles.

Japan and the United States dominate the SSB patent landscape. South Korea also shows a strong presence, particularly in manufacturing-related advancements, while emerging contributions from Canada suggest an increasing focus on sustainable materials. Japan’s dominance in patent filings, particularly in ionic conductivity and interfacial resistance, reflects its strong governmental and industrial support for SSB research, driven by the nation’s commitment to sustainable energy technologies and electric vehicle adoption. In contrast, the United States demonstrates significant focus on manufacturing scalability and architectural innovations, aligning with its strengths in high-tech manufacturing and its priority to maintain leadership in energy storage technologies for both commercial and defense applications. Meanwhile, South Korea exhibits a balanced approach, contributing to advancements in manufacturability and material innovations, which likely stems from its robust battery manufacturing industry and its competitive position in consumer electronics and automotive sectors. These regional variations highlight distinct commercialization barriers, with Japan and South Korea focusing on performance optimization, and the U.S. addressing production efficiency.

Recent advances in hybrid electrolyte designs, combining the high ionic conductivity of sulfide-based electrolytes with the flexibility of polymer systems, address the limitations of each problem category. These hybrid materials provide a balance of conductivity, mechanical strength, and stability, paving the way for enhanced performance in SSBs. Innovations in electrode architecture, such as the integration of nanostructured materials and protective interfacial layers, have significantly reduced interfacial resistance while improving ion transport. These advancements enable higher capacity retention and cycle stability, critical for applications requiring long-lasting energy storage. Emerging roll-to-roll production methods and scalable deposition techniques, such as impact spraying and ion beam-assisted processes, have streamlined the production of solid electrolytes and thin-film electrodes. These processes not only enhance manufacturing efficiency but also improve the uniformity and quality of the battery components, addressing key scalability challenges.

5.2. Ionic Conductivity

Solid-state batteries, particularly those using lithium-ion and sodium-ion chemistries, face a myriad of interrelated challenges stemming from low ionic conductivity. Conventional solid electrolytes, including sulfide-based materials often exhibit poor ion mobility, limiting battery capacity, power output, and electrochemical stability. Sulfide-based electrolytes offer high ionic conductivity and ease of processing but exhibit poor moisture stability and the formation of toxic by-products like hydrogen sulfide under ambient conditions. Oxide-based electrolytes, including garnet-type structures like LLZO, provide superior stability and compatibility with lithium metal anodes but face challenges in achieving sufficient ionic conductivity and minimizing interfacial resistance due to their rigid crystalline nature. Halide-based electrolytes strike a balance between ionic conductivity and electrochemical stability, offering promising performance for high-voltage applications. However, their scalability remains a challenge due to the high cost and limited availability of precursor materials. Polymer-based electrolytes are flexible and safer than inorganic alternatives but exhibit lower ionic conductivity, especially at room temperature, limiting their applicability for high-power systems. Manufacturing inefficiencies, such as void formation, interfacial resistance, and material degradation during sintering or oxidation, further reduce ion transport and increase resistance. These challenges illustrate the complex interplay between material choice, electrolyte design, and battery architecture, necessitating innovations across multiple fronts to improve the performance and viability of next-generation SSBs.

Patents within this category have developed a variety of material and structural innovations to address the pervasive issue of low ionic conductivity in SSBs. Many solutions focus on enhancing ion transport pathways through the design of new solid electrolytes, such as materials based on Li2GeO3 and modified with specific elements to improve both conductivity and safety. Composite designs, including the combination of sulfide and hydride electrolytes or multi-layer polymer electrolytes, significantly reduce interfacial resistance and improve performance. Sulfide-based electrolytes offer high ionic conductivity and are easily processable, though they present challenges with stability and sensitivity to moisture. In contrast, polymer-based electrolytes, such as polyethylene oxide (PEO), provide better mechanical flexibility and safety but tend to suffer from lower ionic conductivities at room temperature. Recent advances in hybrid electrolytes, which combine the benefits of sulfide and polymer systems, present an opportunity to address the limitations of each individual class. These materials offer a balance between conductivity, mechanical strength, and stability, suggesting that the future of energy storage solutions will utilize materials that can enhance both performance and scalability.

Novel electrode materials, such as sodium-ion conductive composites and nanostructured electrodes, increase power output and cycling stability. Sulfide-based electrolytes, including those incorporating lithium sulfide and diphosphorus pentasulfide, achieve high ionic conductivities by stabilizing crystal structures, and glassy electrolyte compositions overcome flammability and stability issues. Additionally, chemical modifications to PEO-based electrolytes and crosslinked siloxane polymers enhance room-temperature conductivity and moisture resistance, further improving battery performance. Other advances, such as the use of separator layers with vertical nanostructures and SSBs with spatially distinct conductivity regions, optimize both safety and ion flow, ensuring better charge-discharge efficiency. These developments, ranging from improved electrode-active materials and protective layers to the use of advanced catholyte solutions, represent a comprehensive effort to tackle the limitations of low ionic conductivity, paving the way for safer, high-performance SSBs suitable for demanding applications like EVs and portable electronics.

5.3. Interfacial Resistance

SSBs, particularly lithium-ion variants, face significant challenges at the electrolyte-electrode interface that compromise both performance and scalability. One key issue is the instability caused by reactions between solid electrolytes and negative electrodes, exacerbated by unsafe or inefficient lithium-doping methods. High interfacial resistance, resulting from poor surface contact between active materials and solid electrolytes, hampers ion transport and reduces electrochemical reactivity, leading to diminished battery capacity and energy density. Manufacturing difficulties, such as low processability and instability during high-temperature sintering, further limit the scalability of these batteries for large-scale production. Other critical challenges include sulfur dissolution in lithium-sulfur batteries, the formation of high-impedance solid electrolyte interphases (SEIs), and mechanical degradation due to non-uniform current densities. Additionally, poor adhesion between the electrolyte and active materials, high internal resistance, and chemical instability at the interface all contribute to reduced performance, safety concerns, and limited commercial viability. High-voltage systems are particularly prone to these issues. During high-rate charge-discharge cycles, interfacial degradation and chemical reactions lead to efficiency losses and durability challenges.

Patents within this category have proposed various solutions to address interfacial resistance challenges, focusing on material and process advancements. Companies have developed new solid electrolyte compositions, such as lithium-containing complex hydrides and borate-based network polymers, to improve ion conductivity and interface stability. Coating methods, such as applying stabilization layers to electrolyte materials and active particles, mitigate chemical reactions during sintering and enhance surface contact between electrolytes and electrodes. Techniques like laser ablation and atomic layer deposition (ALD) improve manufacturing scalability, while the use of interfacial layers made of inorganic or organic materials reduces impedance and enhances mechanical stability. Other solutions involve optimizing electrode composition, such as incorporating capacitor-assisted interlayers and creating dual-layer electrode structures, which reduce resistance and improve charge-discharge performance. Novel binder systems and solvent mixing processes enhance adhesion between solid electrolyte particles and active materials, minimizing void formation and improving ion transport. Additionally, innovations in manufacturing methods, including roll-to-roll coating and solvent annealing, streamline the production of high-quality solid electrolytes, improve mechanical stability, and ensure better electrode-electrolyte integration. Together, these solutions aim to reduce interfacial resistance, enhance energy density, and make SSBs more efficient and scalable for commercial applications.

5.4. Mechanical Degradation

Mechanical degradation is a persistent challenge in SSBs, especially in high-energy systems like lithium-sulfur and lithium-metal batteries. One major issue is the significant volume expansion and contraction of electrode materials, particularly in Si-based anodes, which cause structural instability, cracking, and gaps in the solid electrolyte. This results in poor contact and high interfacial resistance, leading to reduced battery performance and lifespan. Lithium-sulfur batteries also suffer from low sulfur utilization and structural collapse during charge-discharge cycles, exacerbated by dendrite formation as ions cyclically shuttle between the electrodes. Similarly, lithium-metal batteries face volume changes during cycling, leading to dendrite formation and mechanical failure. Traditional solid electrolytes, especially sulfide-based ones, are highly reactive, which causes them to degrade during charge-discharge cycles, further compounding mechanical stresses. In laminate-type SSBs, compressive stress and material expansion lead to cracking and short circuits, particularly at the ends of the electrode layers. Furthermore, manufacturing issues such as poor flexibility and brittleness in ceramic electrolytes, as well as challenges in maintaining structural integrity during stacking or assembly, increase the likelihood of mechanical failure. These problems, coupled with poor adhesion between battery components and uneven pressurization during operation, severely limit the scalability, safety, and long-term performance of SSBs.

Patents within this category aimed to mitigate volume changes and enhance structural integrity. One approach involves the use of porous conductive materials and dual-layer anode designs, which accommodate expansion and contraction during cycling, thereby preventing electrode breakage and enhancing battery life. Coating strategies, such as applying nano-sized transition metal layers and multi-layer carbon coatings, improve electrode stability by minimizing structural cracking and preventing cation diffusion. In addition, advanced solid electrolytes, such as those with core-shell morphologies or composite layers reinforced with resin films, provide better flexibility and strength, enabling batteries to withstand mechanical stress. The use of self-healing resins, buffer layers, and spring-loaded mechanisms in battery modules also improves contact between components, reduces stress on cells, and prevents structural collapse. Modern designs such as hollow inorganic filler particles and porous electroactive materials help absorb expansion stress, preventing micro-cracks in high-energy batteries. Manufacturing processes, including electrophoretic deposition and alcohol-based coating methods, ensure the production of dense, defect-free solid electrolytes and thin films, further improving battery durability. These combined innovations create a more robust battery structure capable of withstanding the mechanical stresses of high-energy applications.

5.5. Energy Density

Achieving higher energy density remains a central challenge in SSB technology, particularly for applications requiring lightweight, compact, and high-performance batteries, such as EVs, wearable electronics, and aircraft. Traditional battery designs struggle with optimizing energy storage within size and weight constraints, leading to inefficiencies. Lithium-sulfur (Li-S) batteries, despite their potential for higher energy densities, face issues such as dendrite formation and low conductivity, which degrade capacity and limit their commercialization. Additional hurdles faced include difficulties in achieving high voltage with sodium-ion systems. For electric aircraft, low energy density and the resulting poor power-to-weight ratio are critical limitations. Furthermore, the manufacturing of high-energy-density batteries is complicated by scalability issues, inefficiencies in 3D battery structures, and concerns over lithium dendrite formation and internal short circuits. Battery modules, particularly those used in vehicles, suffer from bulkiness and heavy designs due to the need for multiple components like tabs, spacers, and complex bus bar systems, which reduce energy density and increase assembly complexity.

Patents within this category addressed energy density challenges by focusing on improving battery architecture, material selection, and manufacturing techniques. Advanced designs, such as electrode structures with etched trenches in substrates or stacked wafer configurations, optimize available space and increase surface area, resulting in higher energy density and compact designs. For Li-S batteries, using sulfur cathodes supported by porous conductive networks, such as exfoliated graphite, reduces degradation from recharge cycling and enhances conductivity, improving specific capacity and energy density. Hybrid designs, including batteries that incorporate both sodium and lithium materials or combine capacitor and battery elements, achieve higher voltage and power density while maintaining the safety benefits of solid-state configurations. Prelithiated components and nanowire silicon anodes enhance charge capacity and reduce volume expansion, boosting performance in compact applications like portable electronics. To enhance scalability and reduce inefficiencies, companies use roll-to-roll processes and computational design tools to manufacture high-energy-density SSBs with optimized layer thicknesses and material properties, improving energy storage capabilities and minimizing issues like lithium dendrite formation. Lightweight, fiber-based battery systems integrated into aircraft structures, as well as structural batteries with carbon fiber electrodes [

57], demonstrate new avenues for increasing energy density while simultaneously reducing the weight and size of battery modules. These innovations collectively enable higher energy densities across a range of applications while addressing the mechanical and manufacturing challenges inherent in SSB technology.

5.6. Battery Safety

Safety is a critical concern because lithium-based batteries face issues like overheating, dendrite formation, and reactivity with electrolytes, which can lead to short circuits, thermal runaway, or even explosions. Lithium metal anodes, known for their high energy density, exacerbate these risks due to dendritic growth and poor morphology changes, increasing impedance and decreasing performance over time. PEO-based electrolytes suffer from poor low-temperature performance and present fire risks at higher temperatures, while ceramic electrolytes lack flexibility, limiting their application in deformable devices. Traditional liquid electrolytes pose significant fire hazards and thermal instability, especially under high voltage charging conditions. Additionally, SSBs generate heat during electrode reactions and are vulnerable to moisture ingress, which can degrade performance and compromise safety. In hybrid battery modules, the spread of fire from liquid electrolyte cells to solid-state cells further complicates safety management. Furthermore, the formation of hydrogen sulfide in sulfide-based solid electrolytes poses toxicity and safety concerns. Combined, these factors create complex safety challenges that hinder the widespread adoption of high-energy, high-performance batteries.

Patents within this category have aimed to improve battery safety by focusing on material enhancements, structural design improvements, and advanced manufacturing techniques. Key developments include the introduction of heat-resistant layers between the cathode and anode to prevent overheating, as well as novel non-flammable electrolytes, such as specific organic solvent and lithium salt mixtures, which reduce fire risks while maintaining performance. Coating lithium metal anodes with materials like metal sulfides or oxides stabilizes the anode and reduces reactivity with the electrolyte, mitigating dendritic growth and improving safety. Composite electrolytes with high polarizability, combined with magnetic field generation within the separator, help suppress dendrite formation while enhancing ion flow. Furthermore, solutions such as openable inlets for releasing gases and moisture within battery enclosures, along with advanced materials like graphene-based flexible solid electrolytes, address safety risks related to thermal instability, moisture ingress, and mechanical stress. These designs not only prevent short circuits and overheating but also enhance overall battery performance, particularly in high-demand applications. Additionally, methods like using meta-solid-state and 3D porous anode structures improve ion conductivity and durability while preventing dendritic growth, allowing for safer high-energy-density batteries. By integrating these advanced materials and designs, the proposed solutions significantly improved safety without sacrificing energy density or efficiency.

5.7. Manufacturability

Manufacturability is a key barrier to scaling SSB technologies. Current solid-state batteries are costly, complex, and difficult to produce at scale. Existing production methods for critical materials such as lithium sulfide (Li2S) and sodium sulfide (Na2S) are inefficient, generating impurities and facing challenges with large-scale nanoparticle production. Other issues that hamper SSB manufacturing include unstable bonding between electrolyte and electrode layers, inefficient deposition processes, and sintering reactions that degrade battery performance. The need for separate electrolyte layers between the anode and cathode adds complexity, time, and cost to production. High sensitivity to moisture in sulfide-based electrolytes, inefficient ionic conductor production methods, and the difficulty of stacking fragile battery components further complicate large-scale manufacturing. Current methods also struggle with environmental control, substrate flexibility, and preventing unwanted reactions that reduce battery performance and reliability. Moreover, processes such as ALD and vapor-phase deposition are too slow and costly for mass production, limiting the scalability of SSBs.

Patents within this category aimed to overcome these manufacturability challenges by focusing on improving scalability, simplifying processes, and enhancing material efficiency. Roll-to-roll production methods using ceramic electrolytes enable high-throughput, scalable SSB manufacturing, achieving high energy densities without dendrite formation. Efficient, scalable methods for producing anhydrous alkali sulfide nanocrystals from hazardous industrial waste (H2S) provide cost-effective solutions for battery material production. To address interface stability, new methods introduce multiple electrolyte layers with different binders to enhance bonding between layers and prevent delamination. Advanced deposition techniques, including physical vapor deposition and ion beam-assisted methods, improve material control and deposition rates, reducing defects and cross-contamination while making large-scale production more feasible. In addition, incorporating protective layers and non-inert gas environments during manufacturing minimizes moisture sensitivity and reduces costs associated with sulfide-based electrolytes. Methods such as impact-based spraying and electrophoretic deposition allow for denser, defect-free films, improving interfacial conductivity and overall battery performance. Streamlining production with solution synthesis processes, impact spraying, and rotating press rollers further enhances manufacturing efficiency, making large-scale production of SSBs more cost-effective and reliable for mass-market applications. These innovations collectively address the scalability and complexity issues inherent in SSB manufacturing, facilitating broader adoption.

5.8. Sustainable Materials

The sustainability of materials used in conventional lithium-ion batteries presents significant challenges. Carbon-based materials, widely used in battery electrodes, are resource-intensive to produce, contributing to environmental degradation and limiting sustainable manufacturing practices. Solid-state electrolytes, which are critical for lithium-ion batteries, often rely on rare earth materials, increasing production costs and geopolitical risks due to the scarcity of these materials. Additionally, transition metal-based cathodes, such as those containing cobalt, are not only costly and environmentally harmful, but their extraction and processing are energy-intensive, exacerbating the environmental footprint of battery production. The reliance on these materials raises concerns about supply chain stability and long-term sustainability. Furthermore, current anode materials, including lithium metal, pose safety risks such as dendrite formation, while the processes for producing high-performance carbon-based materials, like carbon nanotubes, are expensive and resource-heavy, adding to the environmental and economic burden of modern LIB and SSB technologies.

Patents within this category have aimed to address these sustainability concerns by developing a variety of innovative materials and methods to reduce the environmental impact and improve battery performance. One interesting approach involves producing carbon-based electrode materials from filamentous organisms like Neurospora crassa, which processes can carbonize into a porous, graphitic matrix, offering an eco-friendly and sustainable alternative for energy storage applications. To address the reliance on rare earth elements in solid-state electrolytes, garnet-based ceramic materials with enhanced ion conductivity and reduced rare earth content provide a cost-effective and geopolitically stable solution. Biomolecules like flavin, when attached to polymerizable units, create electroactive polymers that serve as sustainable and recyclable electrode materials. Organic insertion materials and triptycene-based molecules offer high energy density, stability, and recyclability without relying on heavy metals or toxic substances, significantly enhancing the sustainability of battery systems. These innovative materials and processes not only reduce the environmental footprint of battery production but also provide safer, more efficient alternatives for future energy storage technologies.

5.9. Limitations and Future Work

While this study provides a comprehensive analysis of the SSB patent landscape, it has certain limitations that suggest areas for future work. While word clouds and bigram distributions offer valuable insights, they may overlook nuanced technological advancements that patent titles or abstracts may not capture. A deeper content analysis of patent claims could enrich future analyses and provide a more granular understanding of the technical challenges and solutions in SSB research. However, starting with patent abstracts that summarize the most important aspects of an invention offers a clear view of the core technological contributions. Future research could incorporate unsupervised machine learning techniques such as topic modeling to uncover hidden themes or trends in patent claims that manual categorization might not capture. Finally, the study does not address the potential impact of emerging regulatory or environmental factors on SSB innovation, which could be another fruitful area for future investigation. Despite these limitations, this study provides a valuable contribution to the understanding of current trends and technological advances in SSB research.

The roadmap from this study highlights the integration of sustainable materials and scalable manufacturing methods as critical enablers for advancing SSB commercialization. Research into eco-friendly solid electrolytes and recyclable electrode materials addresses environmental concerns while enhancing performance. Additionally, hybrid electrolyte systems and novel electrode architectures are essential for balancing energy density, safety, and cycle life, enabling the scalability of SSB technology across applications such as electric vehicles and grid storage.

Scaling manufacturing processes presents challenges such as achieving uniform material deposition, managing high-temperature sintering, and minimizing production defects, all of which are vital for producing high-quality, scalable SSBs. Integrating SSBs into existing infrastructure, including adapting battery management systems to the properties of solid electrolytes and ensuring compatibility with current charging networks, remains a key hurdle [

58]. To facilitate mass-market adoption, the roadmap emphasizes the development of cost-effective techniques like roll-to-roll processing and impact spraying, which can lower production costs while maintaining performance and quality standards.