Heritage on the High Plains: Motive-Based Market Segmentation for a US National Historic Site

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cultural Heritage Tourism

1.2. Tourist Motivation

1.3. Tourist Market Segmentation

2. Materials and Methods

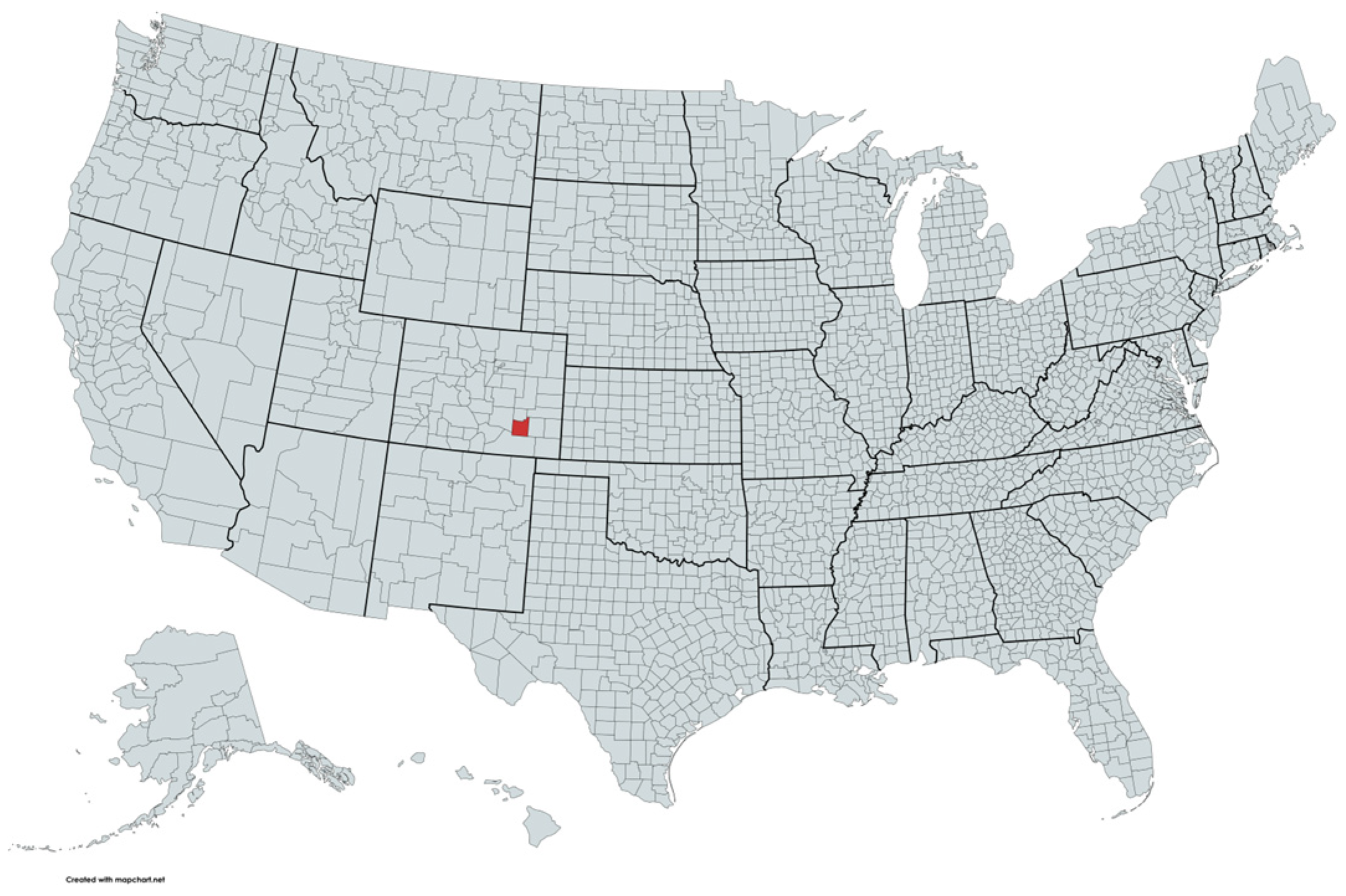

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Measurement and Sampling

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Segment Descriptions

4.2. Implications

4.3. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hargrove, C.M. Cultural Heritage Tourism: Five Steps for Success and Sustainability; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of State. Available online: https://eca.state.gov/cultural-heritage-center (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- National Park System. 2024. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/national-park-system.htm (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Landsel, D. Reservations Anxiety the New Norm at US National Parks as Beaty Spots Battle Crowding. The New York Post. Available online: https://nypost.com/2024/04/24/lifestyle/which-national-parks-are-requiring-reservations-for-summer-2024/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Stephens. Protecting Our National Parks from Overcrowding. CBS News. 2022. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/protecting-our-national-parks-from-overcrowding/ (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Li, Y.; Liang, J.; Huang, J.; Shen, H.; Li, X.; Law, A. Evaluating tourist perceptions of architectural heritage values at a World Heritage Site in South-East China: The case of Gulangyu Island. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 60, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; du Cros, H. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership Between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management; The Hawthorne Hospitality Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg, T. Cultural tourism and business opportunities for museums and heritage sites. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Cultural Heritage and Tourism: An Introduction; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 1Ramires, A.; Brandao, F.; Sousa, A.C. Motivation-based cluster analysis of international tourists visiting a World Heritage City: The case of Porto, Portugal. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimura, T. World Heritage Sites: Tourism, Local Communities and Conservation Activities; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Matteucci, X.; Koens, K.; Licia Calvi, L.; Moretti, S. Envisioning the futures of cultural tourism. Futures 2022, 142, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J.; Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze 3.0; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, N.; Jimura, T. (Eds.) Tourism, Cultural Heritage and Urban Regeneration; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y. Evaluation of urban traditional temples using cultural tourism potential. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Making sense of heritage tourism: Research trends in a maturing field of study. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. The core of heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Rethinking Cultural Tourism; Edward Elgar: Northampton, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Darabos, F.; Kundi, V.; Kőmíves, C. Tourist attitudes toward heritage of a county in Western Hungary. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J. Do tourists destroy the heritage they have come to experience? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2009, 34, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.N.; Johnson, L.W.; O’Mahony, B. Analysis of push and pull factors in food travel motivation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 23, 572–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Kang, S.K.; Ahmad, M.S.; Park, Y.N.; Park, E.; Kang, C.W. Role of cultural worldview in predicting heritage tourists’ behavioural intention. Leis. Stud. 2021, 40, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempiak, J.; Hollywood, L.; Bolan, P.; McMahon-Beattie, U. The heritage tourist: An understanding of the visitor experience at heritage attractions. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, S.; Vada, S.; Yang, E.C.L.; Khoo, C.; Le, T.H. Recreating history: The evolving negotiation of staged authenticity in tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Hatamifar, P. Understanding memorable tourism experiences and behavioural intentions of heritage tourists. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Huang, S. Understanding Chinese cultural tourists: Typology and profile. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.N.; Nguyen, N.A.N.; Nguyen, Q.N.T.; Tran, T.P. The link between travel motivation and satisfaction towards a heritage destination: The role of visitor engagement, visitor experience and heritage destination image. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, N.; Andereck, K.L. Visitors to cultural heritage attractions: An activity-based Integrated typology. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2014, 14, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterstrom, S.M.; Davis, J.A. Historical markers in the western United States: Regional and cultural contrasts. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 15, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, C.A. Tourism Planning, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J.L.; McKay, S.L. Motives of visitors attending festival events. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B. Towards a classification of cultural tourists. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2002, 4, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, R.; Stein, T.V.; Swisher, M.E. Structural relations between motivations and site attribute preferences of Florida National Scenic Trail Visitors. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2020, 38, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Santana, A.; Moreno-Gil, S. Understanding tourism loyalty: Horizontal vs. destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; White, D.D.; Budruk, M. Motive-based tourist market segmentation: An application to Native American cultural heritage sites in Arizona, USA. J. Herit. Tour. 2006, 1, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.M.; Primm, D.; Lafe, W. Tourist motivations for visiting heritage attractions: New insights from a large US study. Int. J. Leis. Tour. Mark. 2017, 5, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L. The Ulysses Factor: Evaluating Visitors in Tourist Settings; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J.L. Motivations for pleasure vacation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.M. Anomie, ego-enhancement and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1977, 4, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamediana-Pedrosa, J.D.; Vila-López, N.; Küster-Boluda, I. Predictors of tourist engagement: Travel motives and tourism destination profiles. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.M. Sustainable heritage management: Exploring dimensions of pull and push factors. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.; Hoogendoorn, G.; Richards, G. Activities as the critical link between motivation and destination choice in cultural tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniya, R.; Thapa, B.; Paudyal, R.; Neupane, S.S. Motive-based segmentation of international tourists at Gaurishankar Conservation Area, Nepal. J. Mt. Sci. 2021, 18, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. Market segmentation analysis in tourism: A perspective paper. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Caldwell, L. Motive-based segmentation of a public zoological park market. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 1994, 12, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S. Market Segmentation in tourism. In Tourism Management: Analysis, Behaviour and Strategy; Woodside, A.G., Martin, D., Eds.; CAB International: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Segarra-Oña, M.; Carrascosa-López, C. Motivation analysis in ecotourism through an empirical application: Segmentation, characteristics and motivations of the consumer. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2019, 24, 60–73. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B.; Tolkach, D.; Eka Mahadewi, N.M.; Byomantara, D.G.N. Choosing the optimal segmentation technique to understand tourist behaviour. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023, 29, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M.A. motivation-based segmentation of holiday tourists participating in white-water rafting. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Choe, Y. Motivation-based segmentation of tourist shoppers to Hainan during COVID-19. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231197497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menor-Campos, A.; Pérez-Gálvez, J.C.; Hidalgo-Fernandez, A.; Lopez-Guzman, T. Foreign tourists in world heritage sites: A motivation-based segmentation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.H.; Cheung, C. The classification of heritage tourists: A case of Hue city, Vietnam. J. Herit. Tour. 2014, 9, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rid, W.; Ezeuduji, I.O.; Pröbstl-Haider, U. Segmentation by motivation for rural tourism activities in The Gambia. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, O. Segmentation of religious tourism by motivations: A Study of the pilgrimage to the City of Mecca. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdy, S.; Alexander, M.; Bryce, D. What pulls ancestral tourists’ ‘home’? An analysis of ancestral tourist motivations. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Castillo Girón, V.M. Profiling tourist segmentation of heritage destinations in emerging markets: The case of Tequila visitors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, C.M.; Gatewood, J.B. Excursions into the un-remembered past: What people want from visits to historical sites. Public Hist. 2000, 22, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Légaré, A.M.; Haider, W. Trend analysis of motivation-based clusters at the Chilkoot Trail National Historic Site of Canada. Leis. Sci. 2008, 30, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Park Service. Bent’s Old Fort. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/beol (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- NPS Stats. Available online: https://irma.nps.gov/Stats/Reports/Park (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Biskin, B. Multivariate analysis in experimental leisure research. J. Leis. Res. 1983, 15, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranskūnienė, R.; Zabulionienė, E. Towards Heritage Transformation Perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n | % | Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Local area residence | ||||

| Female | 258 | 51.0 | Permanent residents | 129 | 25.3 |

| Male | 234 | 46.2 | Seasonal resident | 14 | 2.8 |

| Non-binary | 5 | 1.0 | Non-resident | 366 | 71.9 |

| Transgender | 1 | 0.2 | |||

| Prefer not to answer | 8 | 1.4 | |||

| Education | Travel party | ||||

| Less than high school/Some high school | 1 | 0.2 | Individual traveling alone | 59 | 11.8 |

| You and your spouse/partner | 188 | 37.6 | |||

| High school graduate | 34 | 6.8 | Family | 216 | 43.2 |

| Vocational/trade school certificate | 16 | 3.2 | Friends | 29 | 5.8 |

| Family and Friends | 5 | 1.0 | |||

| Some college | 64 | 12.8 | Tour or other group | 3 | 0.6 |

| Professional degree | 26 | 5.2 | |||

| Associate degree | 40 | 8.0 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 154 | 30.9 | |||

| Master’s degree | 133 | 26.7 | |||

| Doctorate degree | 31 | 6.2 | |||

| n | Mean | n | Mean | ||

| Age | 480 | 53.8 | Travel party composition | ||

| Length of trip (days) | 279 | 2.6 | Adults | 506 | 2.3 |

| Children | 504 | 0.6 |

| Motives | Not at All Important % | Slightly Important % | Moderately Important % | Very Important % | Extremely Important % | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience the historic setting of the Fort | 0.7 | 1.5 | 10.3 | 36.3 | 51.2 | 4.36 |

| Appreciate American history | 0.7 | 2.6 | 11.7 | 38.6 | 46.4 | 4.27 |

| Learn about the history of Bent’s Old Fort | 0.7 | 1.5 | 13.0 | 38.9 | 46.0 | 4.28 |

| Appreciate the historic architecture at Bent’s Old Fort | 1.3 | 5.2 | 14.7 | 32.8 | 46.0 | 4.17 |

| Spend time with family/friends | 9.4 | 5.2 | 11.9 | 31.9 | 41.7 | 3.91 |

| Appreciate the scenic beauty | 4.3 | 6.0 | 21.1 | 31.2 | 37.5 | 3.92 |

| Experience the natural environment | 3.5 | 5.2 | 24.5 | 32.6 | 34.3 | 3.89 |

| Enjoy peace and quiet | 7.6 | 7.6 | 25.5 | 26.1 | 33.3 | 3.70 |

| Experience the sounds of nature | 7.4 | 11.3 | 24.0 | 30.1 | 27.1 | 3.58 |

| Learn from historic demonstrations | 11.4 | 14.3 | 20.3 | 24.5 | 29.5 | 3.46 |

| Experience cultural sounds | 13.3 | 13.1 | 23.7 | 27.8 | 22.1 | 3.32 |

| Means | Univariates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motives | Cluster 1: Heritage Immersers Mean n = 170 | Cluster 2: History Appreciators Mean n = 196 | Cluster 3: Casual Sightseers Mean n = 96 | F | p | Partial η2 |

| Learn about the history of Bent’s Old Fort | 4.74 a | 4.03 b | 3.97 b | 56.0 | 0.00 | 0.20 |

| Appreciate American history | 4.73 a | 4.02 b | 3.91 b | 54.3 | 0.00 | 0.19 |

| Experience the historic setting of the Fort | 4.85 a | 4.18 b | 3.91 c | 70.4 | 0.00 | 0.24 |

| Appreciate the historic architecture at Bent’s Old Fort | 4.82 a | 3.92 b | 3.49 c | 94.6 | 0.00 | 0.29 |

| Learn from historic demonstrations | 4.33 a | 3.30 b | 2.03 c | 148.1 | 0.00 | 0.39 |

| Appreciate the scenic beauty | 4.81 a | 3.80 b | 2.64 c | 269.2 | 0.00 | 0.54 |

| Spend time with family/friends | 4.62 a | 3.68 b | 3.15 c | 61.2 | 0.00 | 0.21 |

| Experience the sounds of nature | 4.64 a | 3.44 b | 2.04 c | 405.8 | 0.00 | 0.64 |

| Experience cultural sounds | 4.53 a | 3.10 b | 1.65 c | 449.2 | 0.00 | 0.66 |

| Experience the natural environment | 4.76 a | 3.79 b | 2.59 c | 319.2 | 0.00 | 0.58 |

| Enjoy peace and quiet | 4.72 a | 3.58 b | 2.19 c | 318.9 | 0.00 | 0.58 |

| Variables | Total % | Heritage Immersers % | History Appreciators % | Casual Sightseers % | Chi-Square | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local area resident | ||||||

| Permanent residents | 26.2 | 34.2 | 24.3 | 16.1 | 12.11 | 0.02 |

| Seasonal resident | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 1.1 | ||

| Non-resident | 70.7 | 62.6 | 71.8 | 82.8 | ||

| Employment | ||||||

| Employed | 61.9 | 57.8 | 68.5 | 55.6 | 11.88 | 0.02 |

| Retired | 30.6 | 29.9 | 27.5 | 37.8 | ||

| Other | 7.5 | 12.2 | 3.9 | 6.7 | ||

| First time visitor to site | ||||||

| Yes | 71.0 | 62.9 | 71.9 | 83.3 | 12.5 | 0.00 |

| No | 29.0 | 37.1 | 28.1 | 16.7 | ||

| Special interest in historic sites | ||||||

| Yes | 81.7 | 92.4 | 76.9 | 72.6 | 21.14 | 0.00 |

| No | 18.3 | 7.6 | 23.1 | 27.4 | ||

| Destination relative to others | ||||||

| The sole destination of the trip | 17.0 | 20.1 | 18.9 | 7.4 | 18.57 | 0.02 |

| The most important destination of the trip | 7.0 | 10.1 | 6.6 | 2.1 | ||

| Only one of several equally important destinations on the trip | 45.4 | 44.4 | 44.9 | 48.4 | ||

| Just an incidental stop on the way to some other destination | 17.2 | 13.0 | 17.3 | 24.2 | ||

| A spur of the moment stop on a trip taken to other destinations | 13.5 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 17.9 | ||

| Overall experience | ||||||

| Very poor | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 38.96 | 0.00 |

| Poor | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | ||

| Fair | 3.7 | 1.2 | 5.6 | 4.2 | ||

| Good | 31.7 | 17.9 | 35.7 | 47.9 | ||

| Excellent | 64.1 | 80.4 | 58.2 | 47.9 | ||

| Visit again | ||||||

| Yes, likely | 67.5 | 84.8 | 64.7 | 42.4 | 36.19 | 0.00 |

| No, unlikely | 14.2 | 6.1 | 13.9 | 29.3 | ||

| Not sure | 18.3 | 9.1 | 21.4 | 28.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andereck, K.L.; Wise, N.; Budruk, M.; Bricker, K.S. Heritage on the High Plains: Motive-Based Market Segmentation for a US National Historic Site. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10854. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410854

Andereck KL, Wise N, Budruk M, Bricker KS. Heritage on the High Plains: Motive-Based Market Segmentation for a US National Historic Site. Sustainability. 2024; 16(24):10854. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410854

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndereck, Kathleen L., Nicholas Wise, Megha Budruk, and Kelly S. Bricker. 2024. "Heritage on the High Plains: Motive-Based Market Segmentation for a US National Historic Site" Sustainability 16, no. 24: 10854. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410854

APA StyleAndereck, K. L., Wise, N., Budruk, M., & Bricker, K. S. (2024). Heritage on the High Plains: Motive-Based Market Segmentation for a US National Historic Site. Sustainability, 16(24), 10854. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410854