Promoting and Prioritizing the Sustainable Development Goals in Young People

Abstract

1. Introduction

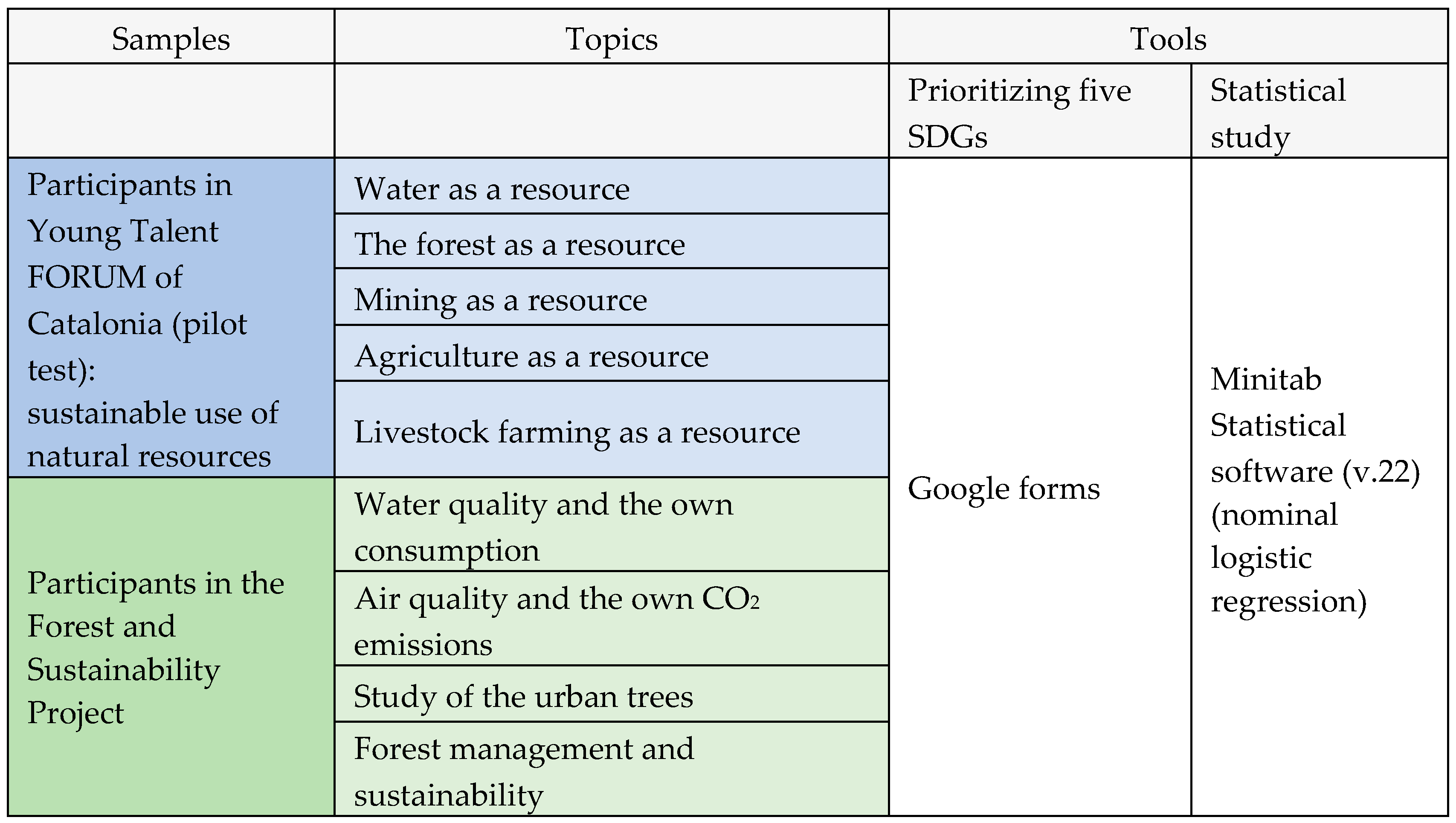

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Samples

2.2. Data Collection Tools

2.3. Tools for Evaluating the Results Obtained

3. Results

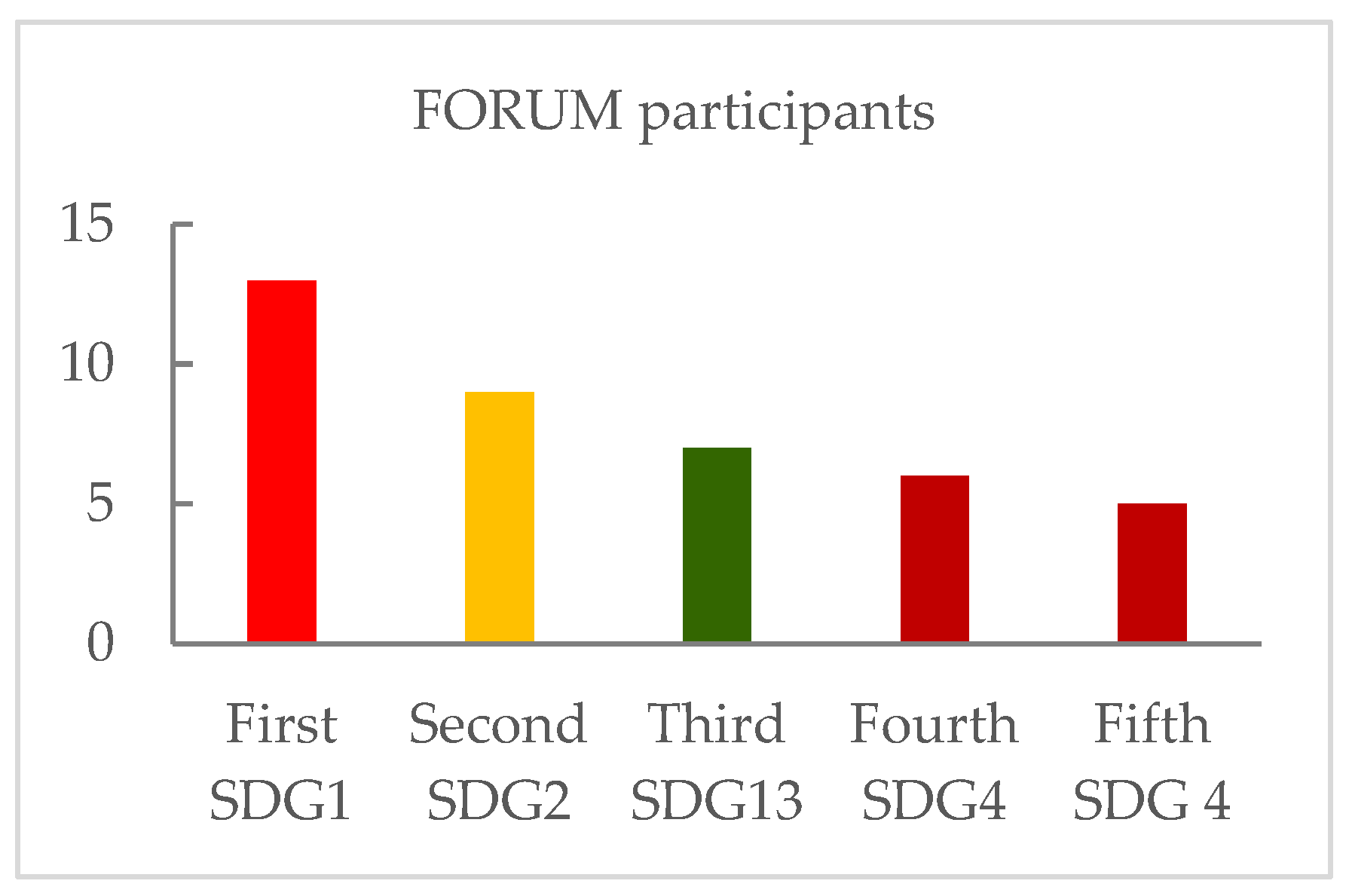

3.1. SDG Prioritization with Young Talent Forum Students

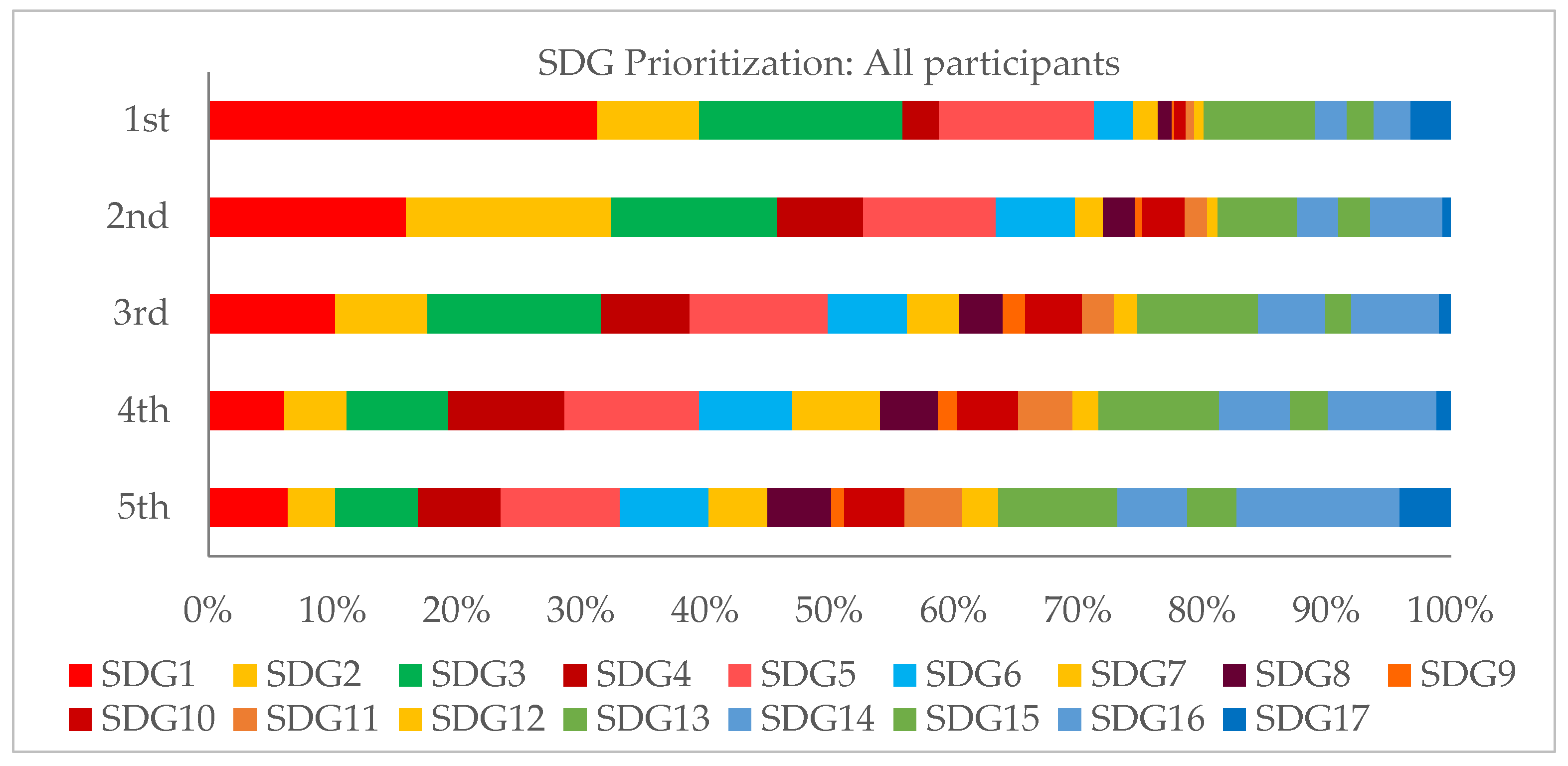

3.2. SDG Prioritization with All Responses

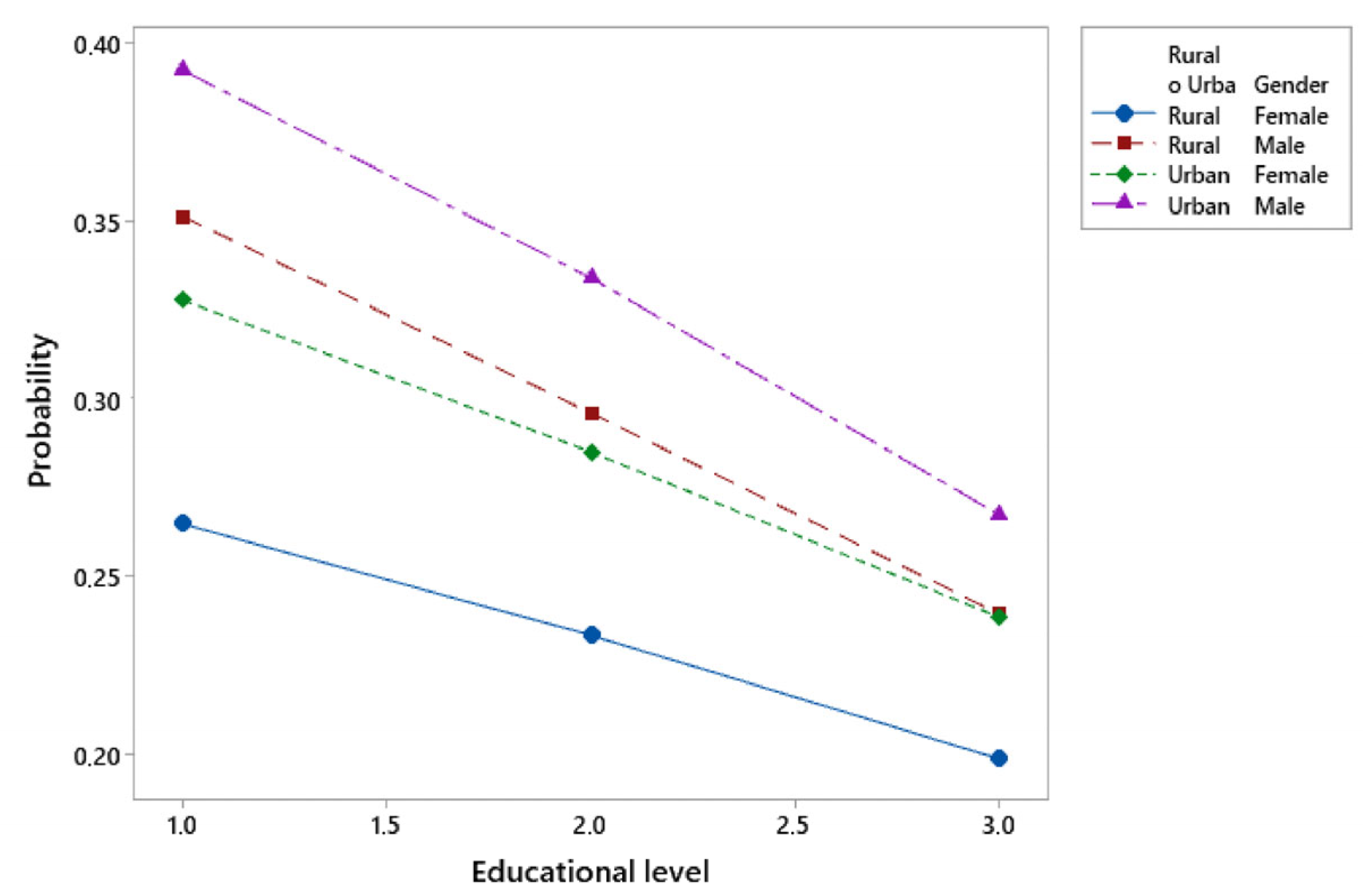

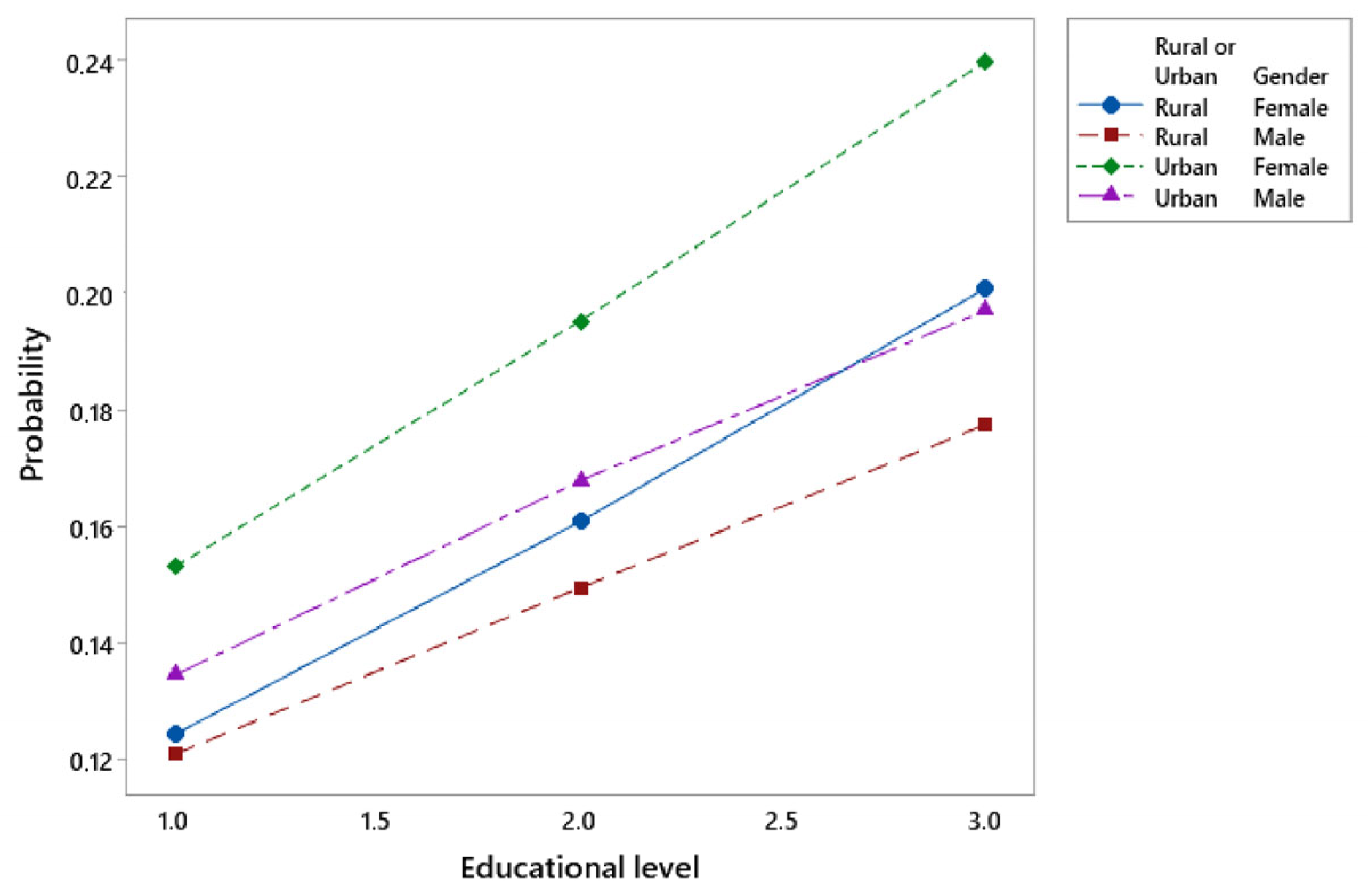

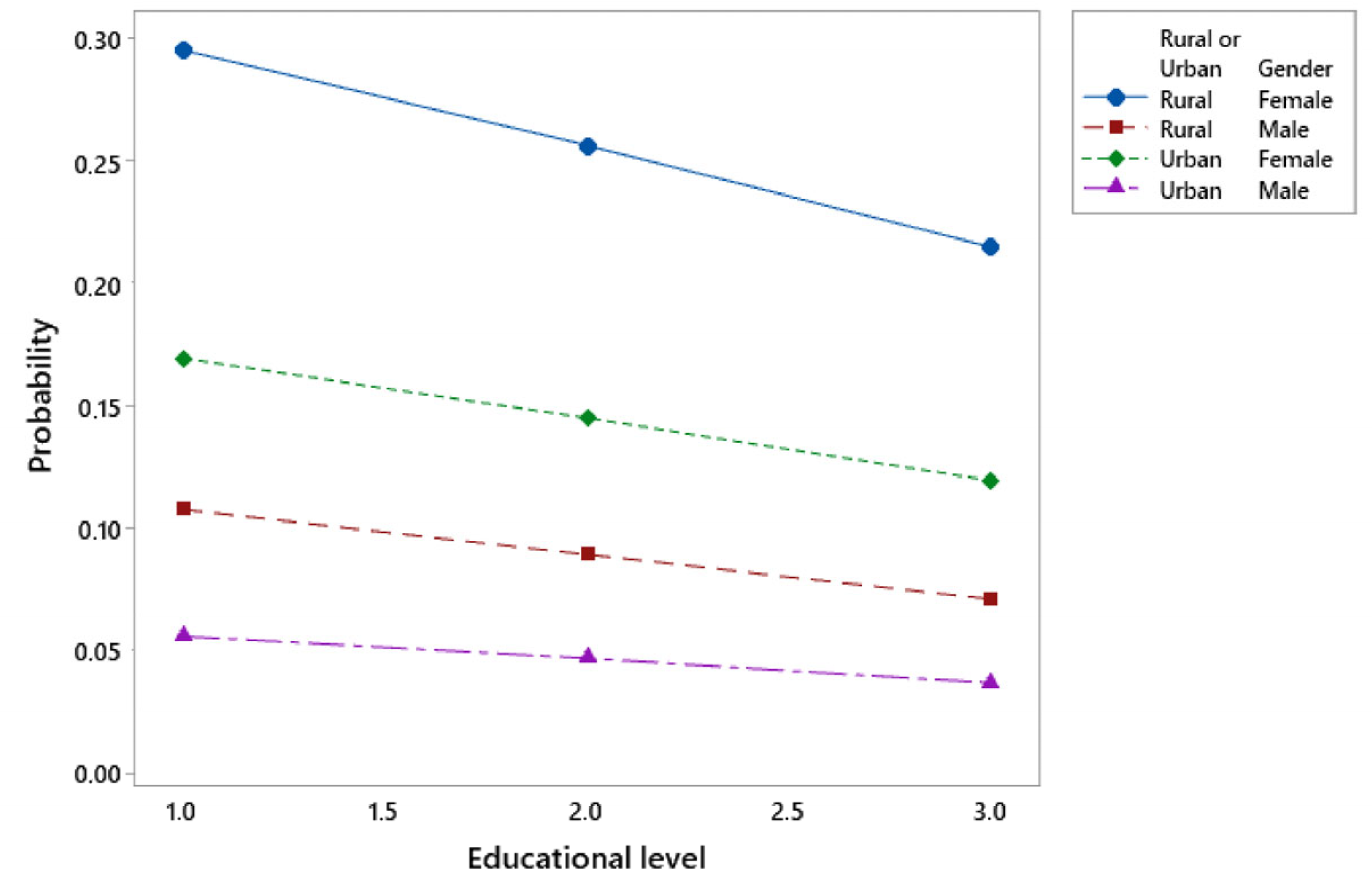

3.2.1. Study Conducted on First-Choice Responses

- –

- If the person is from a rural area, they are 1.01 times more likely to choose SDG 3 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is from an urban area, they are 0.99 times less likely to choose SDG 3 than SDG 1. Multiplying by a number of less than 1 means that the probability decreases; therefore, they are more likely to choose SDG 1 than SDG 3.

- –

- If the person is female, they are 1.36 times more likely to choose SDG 3 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is male, they are 0.73 times less likely to choose SDG 3 than SDG 1.

- –

- In terms of educational level, for each additional educational level, the probability of the person choosing SDG 3 is 1.47 times higher than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is from a rural area, they are 2.16 times more likely to choose SDG 5 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is from an urban area, they are 0.46 times less likely to choose SDG 5 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is female, they are 3.63 times more likely to choose SDG 5 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is male, they are 0.28 times less likely to choose SDG 5 than SDG 1.

- –

- In terms of educational level, for each additional educational level, the probability of the person choosing SDG 5 is 0.98 times lower than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is from a rural area, they are 1.18 times more likely to choose SDG 13 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is from an urban area, they are 0.85 times less likely to choose SDG 13 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is female, they are 1.25 times more likely to choose SDG 13 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is male, they are 0.80 times less likely to choose SDG 13 than SDG 1.

- –

- In terms of educational level, for each additional educational level, they are 1.35 times more likely to choose SDG 13 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is from a rural area, they are 1.97 times more likely to choose SDG 2 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is from an urban area, they are 0.51 times less likely to choose SDG 2 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is female, they are 0.73 times less likely to choose SDG 2 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is male, they are 1.37 times more likely to choose SDG 2 than SDG 1.

- –

- In terms of educational level, for each additional educational level, the probability of the person choosing SDG 2 is 1.49 times higher than SDG 1.

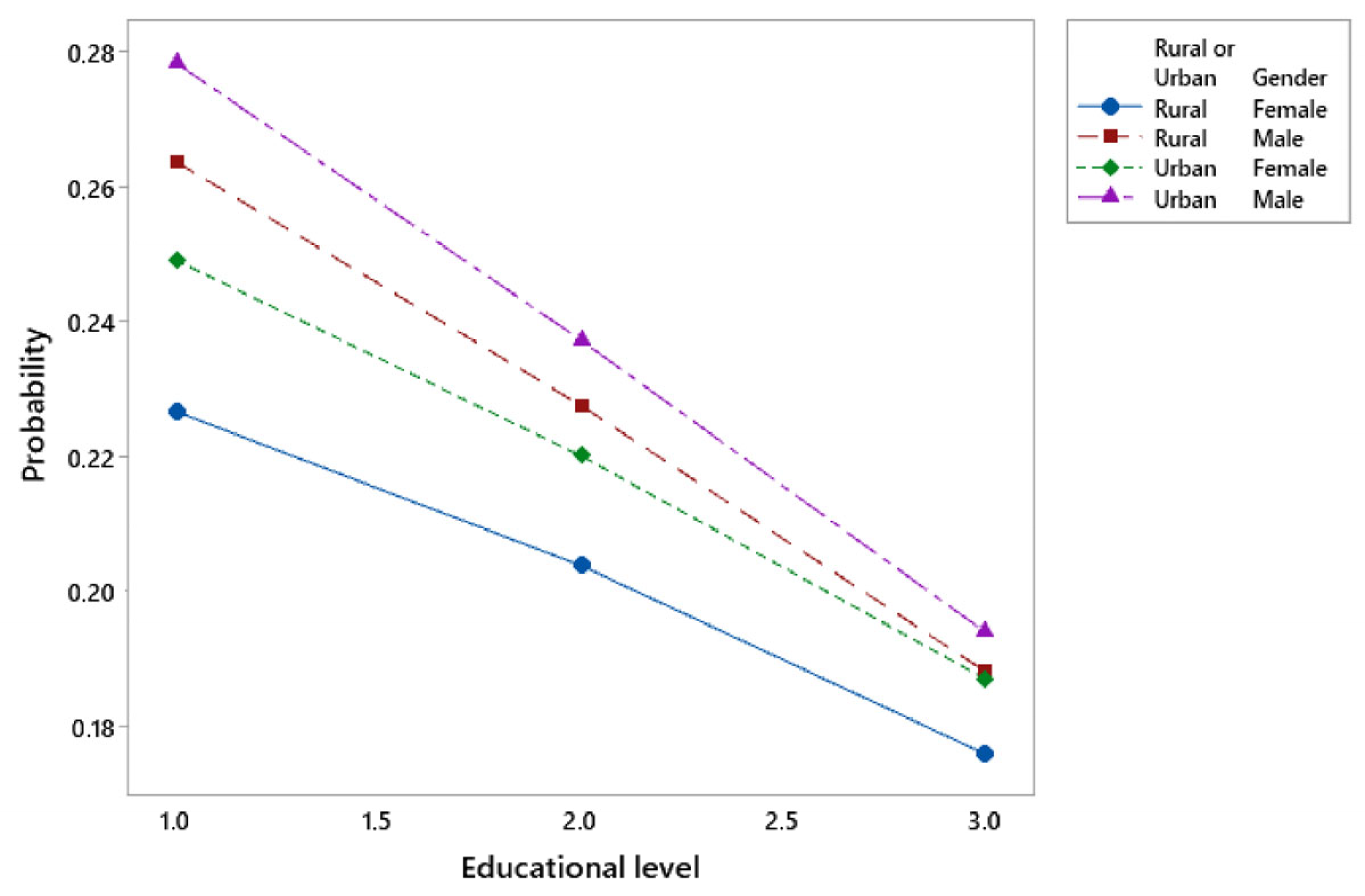

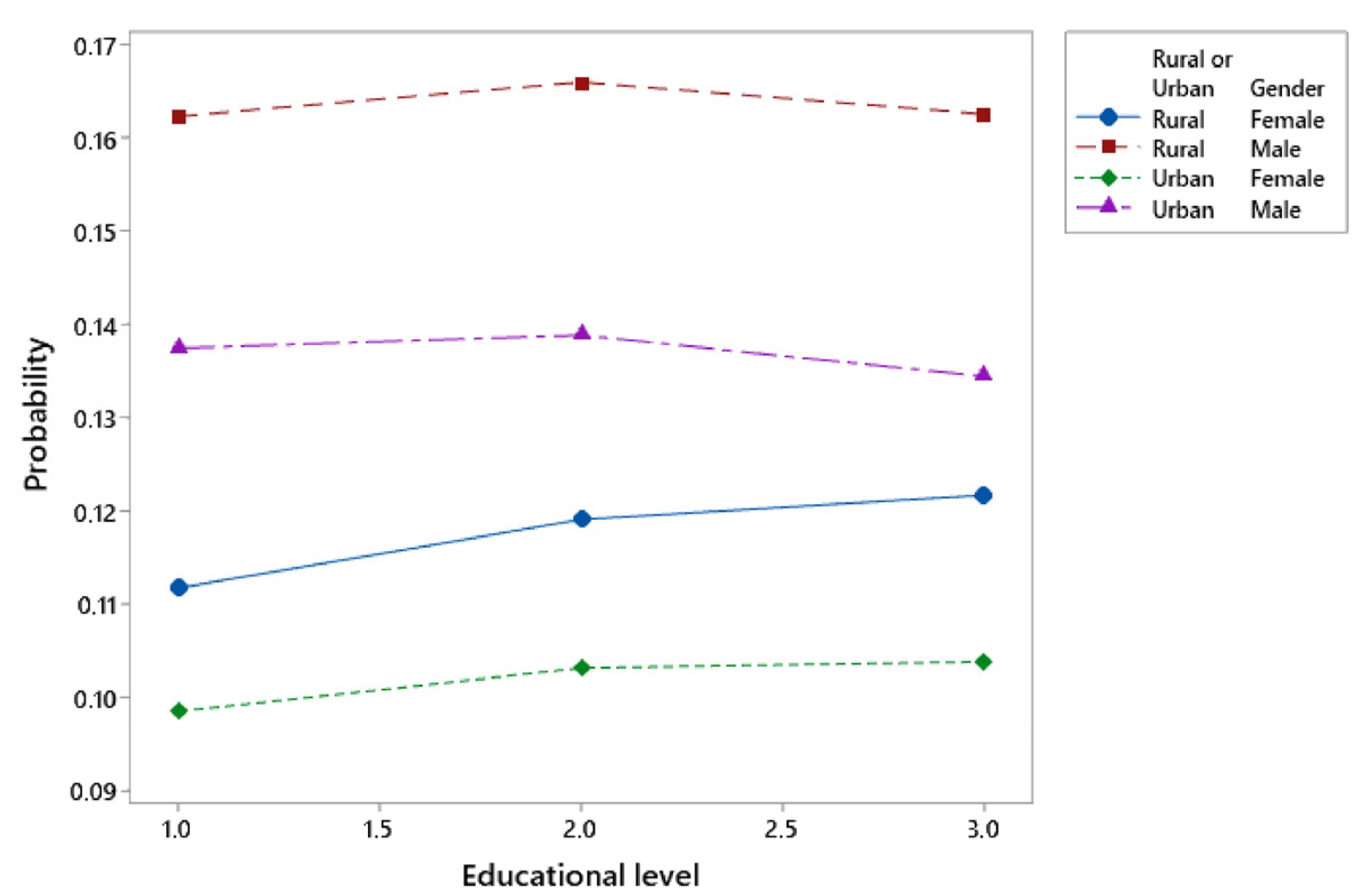

3.2.2. Study Conducted with First- and Second-Choice Responses Together

- –

- If the person is from a rural area, they are 0.96 times less likely to choose SDG 3 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is from an urban area, they are 1.04 times more likely to choose SDG 3 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is female, they are 1.43 times more likely to choose SDG 3 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is male, they are 0.70 times less likely to choose SDG 3 than SDG 1.

- –

- In terms of educational level, for each additional educational level, the probability of the person choosing SDG 3 over SDG 1 is 1.30 higher.

- –

- If the person is from a rural area, they are 1.25 times more likely to choose SDG 2 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is from an urban area, they are 0.80 times less likely to choose SDG 2 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is female, they are 0.80 times less likely to choose SDG 2 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is male, they are 1.25 times more likely to choose SDG 2 than SDG 1.

- –

- In terms of educational level, for each additional educational level, the probability of the person choosing SDG 2 over SDG 1 is 1.19 times higher.

- –

- If the person is from a rural area, they are 1.43 times more likely to choose SDG 5 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is from an urban area, they are 0.70 times less likely to choose SDG 5 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is female, they are 2.80 times more likely to choose SDG 5 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is male, they are 0.36 times less likely to choose SDG 5 than SDG.

- –

- In terms of educational level, for each additional educational level, the probability of the person choosing SDG 5 over SDG 1 is 0.87 times lower.

- –

- If the person is from a rural area, they are 1.19 times more likely to choose SDG 13 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is from an urban area, they are 0.84 times less likely to choose SDG 13 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is female, they are 1.06 times more likely to choose SDG 13 than SDG 1.

- –

- If the person is male, they are 0.94 times less likely to choose SDG 13 than SDG 1.

- –

- In terms of educational level, for each additional educational level, the probability of the person choosing SDG 13 over SDG 1 is 1.18 times higher.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Visser, W.; Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future (‘The Brundtland Report’): World Commission on Environment and Development. In The Top 50 Sustainability Books; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; pp. 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Sustainable Development in the European Union—Monitoring report on Progress Towards the SDGs in an EU Context; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, W.M.; Eckerberg, K. From the Earth Summit to Local Agenda 21: Working Towards Sustainable Development; Routledge: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leggett, J.A.; Carter, N.T. Rio+ 20: The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development; Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. General Assembly 70 Session; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- United Nations. Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations Economic and Social Council: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Global Sustainable Development Report 2019: The Future Is Now—Science for Achieving Sustainable Development; Independent Group of Scientists Appointed by the Secretary-General: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann, M.; Mindt, L.; Gardiner, S. Education for Sustainable Development Goals Learning Objectives; UNESCO: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Global Citizenship Education: Topics and Learning Objectives. 2015. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002329/232993e.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Shulla, K.; Filho, W.L.; Lardjane, S.; Sommer, J.H.; Borgemeister, C. Sustainable development education in the context of the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socientize Consortium. Green Paper on Citizen Science for Europe: Towards a Society of Empowered Citizens and Enhanced Research. Socientize. 2013, pp. 1–54. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/green-paper-citizen-science-europe-towards-society-empowered-citizens-and-enhanced-research (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Cooper, L.; Gorman, D. A holistic approach to embedding social responsibility and sustainability in a university—Fostering collaboration between researchers, students and operations. In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; Alperovitz, G.; Daly, H.; Farley, J.; Franco, C.; Jackson, T.; Kubiszewski, I.; Schor, J.; Victor, P. Building a Sustainable and Desirable Economy in Society in Nature; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, C.; Burton, M.H. Putting the ‘social’ into sustainability science. In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R. A theory of socio-ecological system change. J. Bioecon. 2014, 16, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Fioramonti, L.; Kubiszewski, I. The UN sustainable development goals and the dynamics of well-being. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, D. Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.E. The nexus between international law and the sustainable development goals. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2016, 25, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Griggs, D.; Visbeck, M. Policy: Map the interactions between sustainable development goals. Nature 2016, 534, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, P.; Costa, L.; Rybski, D.; Lucht, W.; Kropp, J.P. A systematic study of sustainable development goal (SDG) interactions. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hull, V.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Tilman, D.; Gleick, P.; Hoff, H.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Xu, Z.; Chung, M.G.; Sun, J.; et al. Nexus approaches to global sustainable development. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, A.N.; Madsen, M.B. Early prioritization of the United Nation’s goals for sustainable development in construction projects. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 588, 052054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, W.; Liu, Y.; Cherubini, F.; Fu, B.; Pereira, P. Prioritizing sustainable development goals and linking them to ecosystem services: A global expert’s knowledge evaluation. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, W.; Vacik, H.; Pülz, H.; Carlsen, H. Deepening our understanding of which policy advice to expect from prioritizing SDG targets: Introducing the Analytic Network Process in a multi-method setting. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 17, 1473–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, D.; Gowsy, S.; Riffon, O.; Boucher, J.-F.; Dubé, S.; Villeneuve, C. A systemic approach for sustainability implementation planning at the local level by sdg target prioritization: The case of Quebec City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. Questions and Answers: Youth Action Plan in EU External Action for 2022–2027. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_22_5882 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Stockholm Resilience Centre. The SDGs Wedding Cake. 2016. Available online: https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-news/2016-06-14-the-sdgs-wedding-cake.html (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Aleixo, A.M.; Leal, S.; Azeiteiro, U.M. Higher education students’ perceptions of sustainable development in Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 327, 129429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, D.; Lysenko-Ryba, K.; Zatwarnicka-Madura, B. Polish students’ attitude to the importance and assessment of implementation of 17 SDGs—Pilot study. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2023, 17, 1291–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva-Brondo, M.; Lajara-Camilleri, N.; Vidal-Meló, A.; Atarés, A.; Lull, C. Spanish University Students’ Awareness and Perception of Sustainable Development Goals and Sustainability Literacy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulero, L.; Cunill-Solà, J.; Grau, M.D. Implementació a L’aula del Projecte BOSC i Sostenibilitat: Curs de Formació del Professorat; Congreso Internacional de Docencia Universitaria e Innovación (XII CIDUI): Lleida, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaprakash, D.; Kanimozhiselvi, C.S. Multinomial logistic regression method for early detection of autism spectrum disorders. Meas. Sens. 2024, 33, 101125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaçorri, D.; Totoni, R.; Prifti, L. Multinomial logistic regression to estimate the public perception of air pollution and its impact on health: A case study in Tirana. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Recent Academic Studies ICRAS 2023, Konya, Turkey, 22 October 2023; All Sciences Academy: Konya, Turkey, 2023; pp. 312–317. [Google Scholar]

- Widiyanto, W.; Nurkhin, A.; Yulianto, A.; Daud, N.M. Multinomial logistic regression for the analysis of career decision style in teacher education. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 12, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Schools | Low Level | Medium Level | High Level | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 (34%) | Rural | |||||

| Female | 98 (19%) | 23 (6%) | 12 (7%) | 133 (13%) | ||

| Male | 95 (18%) | 27 (8%) | 12 (7%) | 134 (13%) | ||

| 37 (66%) | Urban | |||||

| Female | 157 (30%) | 170 (48%) | 85 (51%) | 412 (39%) | ||

| Male | 177 (33%) | 136 (38%) | 59 (35%) | 372 (35%) | ||

| 56 | 527 (50%) | 356 (34%) | 168 (16%) | 1051 |

| Odds Ratio | IC of 95% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Coef. | p-Value | Inferior | Superior | |

| Logit 5: (13/1) | |||||

| Constant | −1.734 | 0.000 | |||

| Rural or Urban | |||||

| Urban | −0.168 | 0.549 | 0.85 | 0.49 | 1.47 |

| Educational level | 0.301 | 0.064 | 1.35 | 0.98 | 1.86 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 0.222 | 0.345 | 1.25 | 0.79 | 1.98 |

| Logit 13: (5/1) | |||||

| Constant | −1.164 | 0.000 | |||

| Rural or Urban | |||||

| Urban | −0.7681 | 0.001 | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.73 |

| Educational level | −0.016 | 0.919 | 0.98 | 0.73 | 1.34 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 1.289 | 0.000 | 3.63 | 2.30 | 5.74 |

| Logit 15: (3/1) | |||||

| Constant | −1.448 | 0.000 | |||

| Rural or Urban | |||||

| Urban | −0.005 | 0.982 | 0.99 | 0.63 | 1.58 |

| Educational level | 0.383 | 0.003 | 1.47 | 1.14 | 1.90 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 0.309 | 0.105 | 1.36 | 0.94 | 1.98 |

| Logit 16: (2/1) | |||||

| Constant | −1.387 | 0.000 | |||

| Rural or Urban | |||||

| Urban | −0.679 | 0.012 | 0.51 | 0.30 | 0.86 |

| Educational level | 0.402 | 0.017 | 1.49 | 1.08 | 2.08 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | −0.318 | 0.202 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 1.19 |

| GL | p-Value |

|---|---|

| 48 | 0.0001 |

| Method | Chi-Square | GL | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson | 115.853 | 128 | 0.771 |

| Deviation | 123.687 | 128 | 0.591 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mulero, L.; Grau, D.; Cunill, J.; Fàbregas, A.; Rossell, J.M. Promoting and Prioritizing the Sustainable Development Goals in Young People. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410813

Mulero L, Grau D, Cunill J, Fàbregas A, Rossell JM. Promoting and Prioritizing the Sustainable Development Goals in Young People. Sustainability. 2024; 16(24):10813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410813

Chicago/Turabian StyleMulero, Lorena, Dolors Grau, Jordi Cunill, Anna Fàbregas, and Josep M. Rossell. 2024. "Promoting and Prioritizing the Sustainable Development Goals in Young People" Sustainability 16, no. 24: 10813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410813

APA StyleMulero, L., Grau, D., Cunill, J., Fàbregas, A., & Rossell, J. M. (2024). Promoting and Prioritizing the Sustainable Development Goals in Young People. Sustainability, 16(24), 10813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410813